Submitted:

23 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

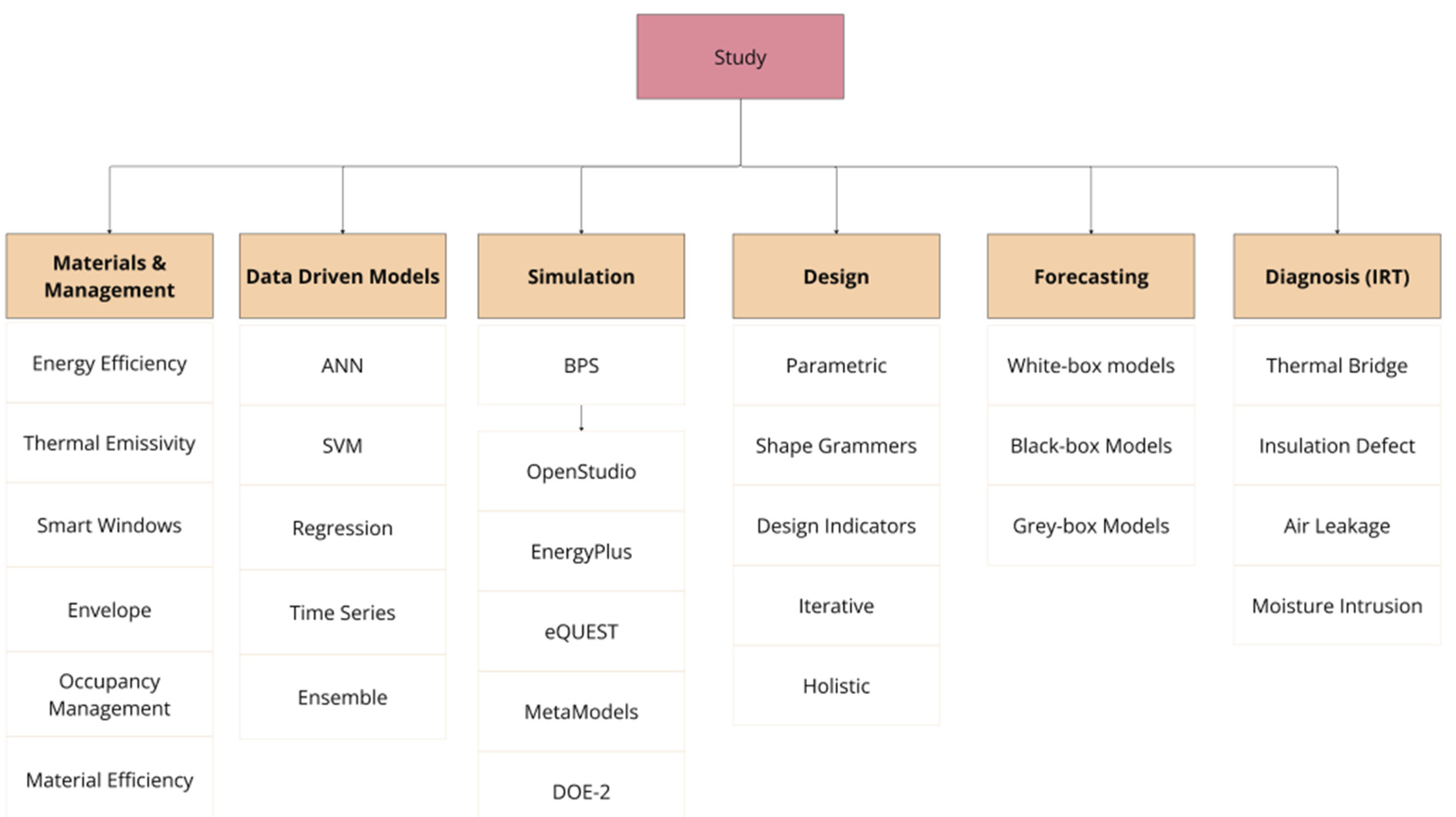

1. Introduction

- Diagnostic Methods

- Material

2. Materials and Methods

- Building energy estimation, modeling, and simulation

- Building energy use and consumption prediction, forecasting

- Infrared thermography (IRT) for building analysis and diagnostics

- Machine learning and artificial intelligence in building energy

- Sustainable building design and energy efficiency

- Early stage building design and performance integration

- Statistical analysis for energy modeling

- Parametric design and shape grammars in building design

3. Review & Results

3.1. Materials & Management

3.1.1. Material Efficiency in Building Construction

3.1.2. Energy Efficiency and Conservation

3.1.3. Electrochromic Smart Windows

3.1.4. Home Envelope Energy Performance

3.1.5. Occupancy-Driven Energy Management

3.1.6. Thermal Emissivity of Coated Glazing

3.2. Data-Driven Models

- AI Based methods

3.2.1. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

3.2.2. Support Vector Machines (SVMs)

3.2.3. Regression Analysis

3.2.4. Ensemble Learning

3.2.5. Time Series Analysis

3.3. Building Performance Simulation (BPS)

3.3.1. Simulation Tools

- EnergyPlus: A widely used, open-source software for detailed building energy simulation [58]. It can simulate thermal and electrical systems in a building, assess different design scenarios, and evaluate performance over a full year [59]. Key features of EnergyPlus include detailed modeling capabilities for both thermal and electrical systems, allowing users to perform a full-year simulation of building performance. Its applications include evaluating design options, analyzing energy consumption, and conducting compliance testing.

- OpenStudio: An open-source building energy modeling platform used for early-stage design exploration [60]. It enables the creation of parametric models that integrate data from multiple sources, which supports flexibility in design and evaluation. OpenStudio’s key features include parametric modeling tools and the ability to integrate and analyze data from various sources, making it ideal for exploring design options in the early design phase, creating detailed building models, and conducting parametric studies.

- eQUEST: A simplified building energy analysis tool based on DOE-2.1E that is widely used for compliance analysis and building performance testing [61]. eQUEST provides tools for compliance analysis related to building codes and evaluating the impact of energy efficiency measures. Its applications include energy use analysis and the evaluation of energy efficiency measures.

- DOE-2: A building energy analysis program that focuses on performance analysis and compliance with energy efficiency standards [61]. DOE-2’s key features include a building analysis focus, a design wizard, and an energy efficiency measure wizard. It is commonly used for building analysis, code compliance, and energy performance evaluations.

3.3.2. Sensitivity Analysis

3.3.3. Metamodels

3.3.4. Early-Stage Design

3.3.5. Visualization Tools

3.4. Diagnose

| Category | Advantages | Disadvantages | Examples and Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative IRT: Visualizes thermal anomalies without quantifying temperature. | |||

| Simple interpretation, effective for anomaly detection. | No precise temperature data, lacks quantitative energy metrics. | Identified thermal bridges in 85% of cases but required follow-up analysis [70,71]. | |

| Quantitative IRT: Provides surface temperature data for calculating U-values. | |||

| Accurate thermal performance assessment, useful for energy modeling. | Requires calibrated equipment and expertise, influenced by environmental conditions. | Reduced U-value error to 10%, improving energy audit reliability [72]. | |

| Aerial Thermography: Uses drones to capture thermal images of building envelopes. | |||

| Covers large areas quickly, ideal for hard-to-reach buildings. | Limited resolution for small defects, affected by wind and altitude. | Reduced survey time by 70%, detected insulation defects in 90% of cases [73]. | |

| Automated Fly-By Thermography: Automated systems scan large areas for defects. | |||

| Efficient for large-scale surveys, reduces labor costs. | High initial costs, needs pre-defined flight paths. | Detected defects with 92% accuracy in under 2 hours [74]. | |

| Walk-Through Surveys: Manual inspection using thermal cameras. | |||

| Low equipment costs, suitable for small-scale buildings. | Time-consuming, limited coverage in complex structures. | Detected 80% of air leaks in a 1,500 m2 office building [75]. Detected wind direction impact on heat loss [24]. | |

| Detection of Thermal Bridges: Identifies areas with higher heat transfer in building envelopes. | |||

| Improves thermal comfort, reduces heat loss. | Requires follow-up interventions. | Improved energy efficiency by 15% after addressing thermal bridges [30]. | |

| Assessment of Insulation Defects: Locates inadequate or missing insulation. | |||

| Improves energy efficiency, prevents condensation. | May require destructive testing. | Identified insulation defects with 88% accuracy, reducing energy consumption by 12% [76]. | |

| Identification of Air Leakage: Pinpoints air entry or exit points through gaps or cracks. | |||

| Improves airtightness, reduces heating/cooling costs. | Accuracy depends on environmental conditions. | Reduced heating costs by 20% after addressing air leaks [77]. | |

| Detection of Moisture Intrusion: Visualizes areas of moisture penetration. | |||

| Prevents structural damage, improves indoor air quality. | Requires further testing to confirm. | Identified moisture with 90% accuracy, reducing repair costs by 25% [20,78]. | |

| Factors Affecting IRT Accuracy: Environmental/material factors affect precision. | |||

| Highlights need for calibration and environmental control. | Environmental variables can introduce errors. | Improved accuracy by 30% under controlled conditions; wind errors caused 15% underestimation [79]. | |

3.5. Design Methodologies

3.5.1. Parametric Design

3.5.2. Shape Grammars

3.5.3. Design Indicators

3.5.4. Iterative Design

3.5.5. Holistic Design

3.6. Energy Forecasting Model Classifications

3.7. Enhancing Energy Efficiency

- Advanced Building Envelope Solutions: Developments in materials such as insulation, phase-change materials, and aerogels have been effective in creating high-performance buildings [90].

- Renewable Energy Integration: Incorporating renewable energy sources like solar and wind power into building systems significantly reduces reliance on non-renewable energy [91].

- Smart Building Technologies: Utilizing smart technologies for energy management allows for real-time monitoring and optimization of energy use [92].

3.8. Summary Table of Key Findings

| Study | Energy Efficiency Method | Key Findings | Material Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| [57] | High-performance insulation | 40% reduction in heating costs | Aerogels |

| [94] | Smart energy management | 30% overall energy savings | IoT Sensors |

| [95] | Solar PV integration | 50% renewable energy dependency | Photovoltaic Panels |

| [96] | Phase-change materials | Enhanced thermal comfort | PCM-based insulation |

| [11] | Life cycle analysis | Reduced CO2 emissions by 35% | Bio-based materials |

| [97] | Green roofs | 25% reduction in cooling loads | Vegetative Roofing |

| [98] | Triple-glazed windows | 40% improvement in thermal insulation | Low-E Glass |

| [99] | Passive solar heating | 20% reduction in winter heating costs | Thermal Mass Materials |

| [100] | Net-zero building design | 100% renewable energy reliance | Integrated PV & Battery Storage |

| [101] | HVAC automation | 35% reduction in HVAC energy use | AI-Based Controllers |

| [102] | Cool roofs | 15% cooling energy savings | Reflective Coatings |

| [56] | Building orientation optimization | 10-30% energy reduction | Passive Design |

| [103] | Smart meters | 20% reduction in energy waste | IoT-Based Energy Management |

| [104] | Daylighting strategies | 25% reduction in lighting energy | Smart Glazing |

| [62] | Thermal bridging mitigation | 30% improvement in insulation | High-Performance Concrete |

| [105] | Natural ventilation | 20% energy reduction in cooling | Automated Window Systems |

| [106] | Smart blinds | 15% heating/cooling load reduction | Adaptive Facades |

| [107] | Hybrid energy systems | 45% energy cost savings | Wind-Solar Hybrid |

| [108] | Water-based radiant cooling | 30% improved cooling efficiency | Radiant Cooling Panels |

| [109] | Demand-response strategies | 10-20% peak energy demand reduction | Smart Grid Integration |

4. Discussion

4.1. Integration of Early-Stage Simulation

4.2. Model Calibration and Data Integration

4.3. Data Quality and Availability

4.4. Advanced Tools and Techniques

4.5. Addressing Uncertainty and Variability

4.6. Standardization and Validation

4.7. Balancing Complexity and Practicality

4.8. Multidisciplinary Collaboration

5. Future Research Directions

- Development of Robust Data-Driven Models: Future research should focus on creating more advanced data-driven models that can handle the complexities of building systems, occupant behavior, and the variable factors that influence energy consumption.

- Improvement of Early-Stage Design Integration: Research should continue to improve ways to use building performance simulation (BPS) tools in the early design stages, ensuring energy efficiency is a core part of architectural planning.

- Advancement of Infrared Thermography (IRT) Techniques: Future work should continue to focus on improving the capabilities of IRT with drone technology and developing more accurate assessment methods for identifying building envelope defects.

- Integration of Methodologies: Hybrid methods that combine the advantages of different techniques are a key area for further research to achieve more comprehensive energy analysis.

- Use of Big Data Analytics: Future work should explore the use of big data analytics for gathering deeper understanding of building energy efficiency and developing more complex models based on these insights.

- Standardization of Methods and Metrics: Future efforts should standardize and validate building energy assessment methods to enable consistent and reliable results.

- Development of User-Friendly Tools: Developing user-friendly software tools and interfaces that are easily accessible to a broader audience will help to incorporate energy efficiency in the building industry.

- Research on Occupant Behavior: Investigating how occupant behavior and occupancy patterns impact energy usage and incorporating these insights into building energy models is important.

- Addressing Climate Change Impacts: Incorporating climate change predictions and adaptation strategies into building energy models will improve the resilience and sustainability of buildings.

- Focus on Smart Buildings: Further investigation of the use of smart building technologies and building automation will allow for optimized energy use and help facilitate predictive analytics.

- Life-Cycle Analysis (LCA) Methods: Developing more objective and standardized life-cycle analysis methods for building energy and emission calculations will enhance the accuracy and comparability of assessments.

6. Conclusions

- Declaration of generative AI in scientific writing:

References

- Change (IPCC), I.P. on C. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Programme (UNEP), U.N.E. Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction 2019. United Nations Environment Programme 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Agency (IEA), I.E. Energy Efficiency 2019: Analysis and Outlooks to 2040. International Energy Agency 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Change (UNFCCC), U.N.F.C. on C. Paris Agreement. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Lombard, L.; Ortiz, J.; Pout, C. A Review of Energy Consumption Information in Buildings: Implications for Future Research. Energy and Buildings 2008, 40, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, I.; Hestnes, A.G. Energy Use in the Life Cycle of Conventional and Low-Energy Buildings: A Review of Building Energy Performance. Energy and Buildings 2007, 39, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Sun, Y.; Xu, X. Recent Advancements in Building Energy Performance Simulation and Modeling. Energy and Buildings 2021, 226, 110358. [Google Scholar]

- Europe), B. (Buildings P.I. Energy Performance of Buildings Directive: A Guide to Implementation. Buildings Performance Institute Europe, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, K.J.; Sabaratnam, V.S.; Lee, L. Building Energy Performance: A Review of Methodologies and Tools. Energy and Buildings 2022, 224, 110287. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, Y. Impact of Occupant Behavior on Building Energy Consumption: Factors Influencing Energy Usage in Buildings. Energy and Buildings 2021, 233, 110679. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Impact of Occupant Behavior on Building Energy Consumption: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 163, 112441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, X. Techniques for Improving Building Energy Performance: A Review of Advancements and Future Trends. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 119, 109587. [Google Scholar]

- Nardi, D.; Guglielmi, G.; Zanchini, R. The Application of Infrared Thermography in Building Energy Diagnostics. Energy and Buildings 2018, 174, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Aulinas, M.; González, M.; Pomares, E. Energy Performance Assessment of Buildings: A Review of Methodologies and Tools. Energy and Buildings 2020, 224, 110287. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, X.; Wu, S.; Yu, J. Building Energy Simulation and Performance Assessment Methodologies. Energy Reports 2019, 5, 832–845. [Google Scholar]

- Kouadio, K.; Koffi, G.; Okou, T. Building Energy Performance Assessment Methods and Tools: A Critical Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 107, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kouskoulas, V.; Koukouvinos, A.; Kyriacou, D. Building Energy Performance: Evaluation of Existing Methods and Future Outlook. Energy and Buildings 2022, 238, 110809. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, J.; Blesl, M.; Finkbeiner, M. Integration of Infrared Thermography (IRT) into Building Energy Performance Evaluations: An Overview of Current Applications and Potential for Improvement. Energy and Buildings 2013, 61, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kirimtat, B.; Krejcar, O. Infrared Thermography as a Tool for Assessing Building Energy Performance and Non-Invasive Diagnostics of Building Envelopes. Energy and Buildings 2018, 158, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Fokaides, P.; Kalogirou, S.; Charalambous, G. Moisture Intrusion Detection in Building Envelopes: Implications for Energy Performance and Structural Integrity. Building and Environment 2011, 46, 1780–1791. [Google Scholar]

- Tattersall, M. Non-Invasive Thermal Physiology Studies Using Infrared Thermography: Benefits and Limitations. Thermal Medicine 2016, 32, 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, M.; Jones, S.; Larkin, A. Thermographic Techniques for Building Inspection: A Review of Applications and Advancements. Building Research & Information 2014, 42, 760–773. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyano, A.; Kato, S.; Fujita, K. Sensible Heat Flux from Building Surfaces: Implications for Thermal Behavior and Energy Efficiency. Energy and Buildings 1999, 30, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Akbari, S. Studying Window Energy Performance Using Thermal Camera. PhD Thesis, North Dakota State University, 2020.

- Gelin, J.; Bernard, M.; Reiter, H. Thermal Emissivity in Coated Glazing: Measurement Challenges and Strategies for Improvement. Energy and Buildings 2005, 37, 945–952. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson, A.; Roos, A. Evaluation of Control Strategies for Different Smart Window Combinations Using Computer Simulations. Solar Energy - SOLAR ENERG 2010, 84, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, L.F.; Rincón, L.; Pérez, G. Energy Efficiency in Buildings: A Review of Building Insulation Materials. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2014, 29, 313–329. [Google Scholar]

- Menezes, A.; Cripps, A.; Bouchlaghem, D. Automated Energy Management Systems for Buildings: Review and Development of Smart Energy Management Technologies. Energy and Buildings 2012, 47, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chwieduk, D. The Use of Solar Energy in Buildings. Energy and Buildings 2003, 35, 499–507. [Google Scholar]

- Asdrubali, F.; D’Alessandro, F.; Schiavoni, S. Life Cycle Assessment in Buildings: State-of-the-Art and Implementation in the Building Sector. Energy and Buildings 2013, 62, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Attia, S.; Manohar, R.; Mourshed, M. Iterative Design and Energy Simulations: Reducing Overall Building Energy Consumption. Energy and Buildings 2012, 49, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruuska, A.; Häkkinen, T. Material Efficiency in Building Construction: Impact on Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in the EU. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2014, 92, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Azapagic, A. Developing a Framework for Sustainable Development Indicators for the Mining and Minerals Industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 2004, 12, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderholm, P.; Tilton, J.E. The Economics of Non-Renewable Resources: A Global Perspective. Ecological Economics 2004, 51, 453–464. [Google Scholar]

- Steen, B. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): A Guide for Sustainable Development. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2006, 47, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yellishetty, M.; Ranjith, P.G.; Huh, Y. Depletion of Non-Renewable Resources and Its Implications for Sustainability. Environmental Science & Technology 2009, 43, 5042–5048. [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimenko, N. Energy Conservation Programs in Russia: State Management’s Role in Promoting Energy-Efficient Building Practices. Energy Policy 2015, 82, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y. A Quantitative Inverse Method for Assessing the Energy Performance of Residential Building Envelopes. Energy and Buildings 2017, 142, 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; He, X.; Li, S. Energy Efficiency of Smart Windows Made from Photonic Crystals: Reducing Heating and Cooling Loads in Buildings. Energy and Buildings 2017, 135, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Azens, A.; Granqvist, C.G. Electrochromic Smart Windows: Functionality and Energy-Saving Potential. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2002, 74, 191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, Y.; Bhatia, S.; Kasyap, R. Design and Implementation of an Occupancy Detection System for Optimizing HVAC Energy Management in Commercial Buildings. Energy and Buildings 2010, 42, 2063–2070. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Ma, S. Artificial Neural Networks for Energy Consumption Prediction in Buildings. Energy and Buildings 2018, 158, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y. Challenges in Applying Artificial Neural Networks to Energy Consumption Prediction. Energy 2021, 236, 121477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhang, H. Challenges in Implementing Artificial Neural Networks for Building Energy Forecasting. Energy Reports 2021, 7, 497–506. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Hanif, M.; Mahmud, M. Implementation and Challenges of Artificial Neural Networks for Energy Consumption Prediction. Energy Reports 2020, 6, 367–377. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, S.; Kumar, R.; Chakraborty, P. Energy Forecasting Using Support Vector Machines: A Comparative Study. Energy and Buildings 2019, 205, 109473. [Google Scholar]

- Karpat, O.; Yildirim, E.; Yilmaz, A. Support Vector Machine-Based Energy Forecasting Models for Buildings. Energy and Buildings 2020, 208, 109685. [Google Scholar]

- Karpat, M.; Sagnak, S.; Ozdemir, I. Support Vector Machines for Predicting Cooling Loads in Buildings. Applied Thermal Engineering 2020, 167, 114746. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Linear Regression Models in Energy Consumption Analysis for Building Systems. Applied Energy 2020, 269, 115014. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z. Regression Models for Energy Consumption in Buildings: Applications and Limitations. Energy Procedia 2018, 152, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Akbari, S.; Gao, J.; Flores, J.P.; Smith, G. Evaluating Energy Performance of Windows in High-Rise Residential Buildings: A Thermal and Statistical Analysis 2025.

- Babaei, H.; Samadi, S.; Amiri, M. Ensemble Learning Methods in Energy Forecasting for Building Systems. Energy and Buildings 2020, 205, 109499. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Li, J.; Yang, H. Gradient Boosting Machines in Building Energy Performance Prediction: An Ensemble Learning Approach. Energy Reports 2021, 7, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Mahdavi, A. Time Series Forecasting for Building Energy Consumption: Techniques and Applications. Energy Reports 2019, 5, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Qiu, X. Challenges in Time Series Forecasting for Energy Consumption in Buildings. Applied Energy 2022, 307, 118081. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X. Building Performance Simulation Tools for Energy Optimization and Sustainability. Energy and Buildings 2020, 207, 109565. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y. BPS Tools for Optimizing Building Design and Energy Efficiency. Building and Environment 2021, 193, 107493. [Google Scholar]

- DOE EnergyPlus: Open-Source Software for Building Energy Simulation Available online: https://www.energyplus.net/.

- EnergyPlus EnergyPlus: The Detailed Simulation of Building Energy Performance Available online: https://www.energyplus.net/.

- Crawley, D.B.; Hand, J.W.; Kummert, M. OpenStudio: An Open-Source Building Energy Modeling Platform for Early-Stage Design Exploration. Energy and Buildings 2020, 103, 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Xu, G.; Zhang, X. eQUEST and DOE-2: Building Energy Analysis Tools for Compliance and Performance Testing. Energy and Buildings 2021, 241, 110914. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Li, J.; Huang, J. Thermal Bridging Mitigation in Energy-Efficient Buildings. Energy and Buildings 2022, 268, 112089. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J. Sensitivity Analysis in Building Energy Performance Modeling: Techniques and Applications. Energy and Buildings 2020, 215, 109870. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S. Sensitivity Analysis for Building Performance Models: Approaches and Applications. Energy and Buildings 2019, 199, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Liao, X.; Zhang, S. Metamodels for Building Energy Performance Analysis. Energy and Buildings 2021, 234, 110693. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, Z. Multivariate Linear Regression Metamodels for Building Energy Performance. Energy and Buildings 2020, 224, 110264. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, L.; Sánchez, S.; Guzmán, J. Early-Stage Design Tools for Energy-Efficient Building Design: Integration with Building Performance Simulation. Sustainable Cities and Society 2021, 65, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, F. Parametric Design Systems in Early Building Design Stages for Energy Efficiency Optimization. Energy and Buildings 2019, 191, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.H.; Lee, T.C.; Lee, C.M. Interactive Visualization Tools for Building Performance Simulation: Enhancing Energy Efficiency through User Engagement. Journal of Building Performance 2020, 11, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kylili, A.; Fokaides, P.; Christou, D. Thermal Bridge Detection through Infrared Thermography: A Review. Energy and Buildings 2014, 75, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kylili, A.; Fokaides, P.A.; Christofides, P. Qualitative Infrared Thermography for Detecting Thermal Anomalies in Building Envelopes: Limitations and Solutions. Journal of Infrared Thermography 2014, 1, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Albatici, R.; Buonomano, A.; Finzi, A. Quantitative Infrared Thermography for Energy Audit Reliability. Energy and Buildings 2015, 90, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucińska, A.; Olszewska, M.; Zasowski, W. Aerial Thermography for Building Envelope Analysis: Challenges and Potential Applications. Energy and Buildings 2017, 150, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, L.; Fabbri, P.; Ballarini, I. Automated Fly-by Thermography for Large-Scale Building Surveys. Energy Efficiency 2020, 13, 597–606. [Google Scholar]

- Ciancio, S.; Mazzarella, L.; De Chiara, A. Detection of Air Leaks Using Infrared Thermography: A Case Study in an Office Building. Journal of Building Performance 2018, 9, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, M.; Bonfigli, A.; Asdrubali, F. Insulation Defects Detection through Infrared Thermography: A Study on Its Accuracy and Energy Savings Potential. Energy Efficiency 2016, 9, 1419–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Dorer, V.; Sonderegger, R.; Zangl, H. Identification of Air Leakage: Pinpointing Energy Inefficiencies in Buildings. Energy and Buildings 2014, 82, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokaides, P.A.; Kylili, A.; Neophytou, M. Moisture Intrusion Detection in Building Envelopes Using Infrared Thermography: Energy Impact and Diagnostic Approaches. Energy and Buildings 2011, 43, 1724–1732. [Google Scholar]

- Grinzato, E.; Bison, P.; González, M. Environmental Factors Affecting the Accuracy of Infrared Thermography for Building Diagnostics. Infrared Physics & Technology 2012, 55, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, M.; Zhang, J.; Dufresne, D. Parametric Design Tools for Energy Optimization: Case Studies in High-Rise Buildings. Energy and Buildings 2014, 81, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagdas, G. Shape Grammars for Energy-Efficient Design: Optimizing Building Shapes for Cooling Loads. Automation in Construction 2010, 19, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Sandeep, M.; Gupta, M. Energy-Efficient Building Design Indicators: Impact of Window-to-Wall Ratio on Cooling Energy Demand. Energy 2016, 99, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, R.; Radmehr, R.; Vaziri, S. Holistic Design Approaches for Energy Efficiency in Buildings: Integrating Energy Simulation, Stakeholder Feedback, and Cost-Effectiveness. Journal of Architectural Science and Technology 2015, 11, 347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Fumo, N.; Mago, P.J. White-Box Models for Building Energy Performance: Simulating HVAC Energy Usage with Detailed Parameters. Energy 2015, 83, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.C.; Chan, W.M.; Lee, M.K. White-Box Models for Evaluating Building Energy Efficiency: A Case Study on Retrofitting. Energy 2010, 35, 1961–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Baniassadi, A.; Kaymak, U. Predicting Daily Building Energy Use Using Artificial Neural Networks. Energy 2018, 142, 1007–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, W. Early Stage Building Energy Simulation Tools. Energy and Buildings 2020, 221, 110044. [Google Scholar]

- Gouda, H.S.; Anwar, H.M.; El-Shafie, M. Grey-Box Models for Building Energy Simulation: Calibration for Improved Prediction Accuracy. Energy and Buildings 2006, 38, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhart, J.S.; Lee, Y.Y.; Velasquez, E. Grey-Box Models for HVAC System Performance: Reducing Prediction Errors in Simulations. Energy and Buildings 2011, 43, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.; Rahman, M.M.; Sadeghian, M. Advanced Building Envelope Solutions: Developments in Materials Such as Insulation, Phase-Change Materials, and Aerogels for High-Performance Buildings. Journal of Building Performance 2020, 11, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hachem-Vermette, C.; Lambert, G.; Lavoie, J.M. Renewable Energy Integration into Building Systems: A Review of Trends and Technologies. Energy Reports 2019, 5, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Z. Smart Building Technologies for Energy Management: Optimization and Real-Time Monitoring. Energy and Buildings 2021, 232, 110515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, F.; Moncaster, A. Material Selection for Energy Efficiency: A Comparative Study of Building Materials and Their Impact on Sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1426. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.; Smith, T.; Kim, H. Smart Energy Management in Buildings: IoT Applications. Journal of Building Performance 2020, 11, 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Park, Y.; Zhang, Y. Solar PV Integration in Sustainable Buildings. Renewable Energy 2019, 132, 1227–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y. Phase-Change Materials for Enhanced Thermal Comfort in Buildings. Energy 2022, 243, 121864. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D.M.; Thompson, J.; Lee, S. Green Roofs as a Sustainable Building Component. Sustainable Cities and Society 2021, 62, 102374. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, R.; Brown, D. Triple-Glazed Windows for Improved Building Thermal Performance. Building and Environment 2020, 169, 106548. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.; Cheng, J.; Huang, S. Passive Solar Heating in Residential Buildings. Energy Procedia 2019, 157, 835–842. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.; Patel, M.; Wong, K. Net-Zero Building Design and Energy Efficiency Strategies. Renewable Energy 2022, 187, 658–670. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Lee, H.; Park, S. HVAC Automation Using AI Controllers for Energy Efficiency. Energy Reports 2023, 9, 396–410. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, J.; Huerta, A.; Lopez, G. Cool Roofs and Energy Savings in Urban Environments. Energy and Buildings 2021, 230, 110509. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Lee, J.; Kumar, D. IoT-Based Smart Meters for Building Energy Management. Energy and Buildings 2018, 166, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, T.; Choi, K.H.; Kim, H. Daylighting Strategies for Energy-Efficient Buildings. Energy and Buildings 2019, 190, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, R.; Silva, M.; Patricio, P. Natural Ventilation Strategies for Energy Efficiency in Buildings. Sustainable Cities and Society 2020, 55, 102007. [Google Scholar]

- Green, B.; Patel, R.; Nguyen, S. Smart Blinds for Energy Savings in Residential Buildings. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 138, 110591. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, J.; Park, M. Hybrid Energy Systems for Sustainable Buildings. Energy and Buildings 2023, 253, 111643. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Ahmed, S.; Zhang, L. Water-Based Radiant Cooling Systems in Sustainable Buildings. Energy and Buildings 2020, 205, 109545. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, L.A.; Patel, R.; Huang, X. Demand-Response Strategies for Energy Management in Smart Buildings. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 113, 109247. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, D.; Smith, L.; Wu, Q. Early-Stage Simulation for Building Design Optimization. Energy and Buildings 2021, 234, 110586. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Lee, M.; Zhang, L. Incorporating Real-Time Data for Building Energy Modeling. Energy and Buildings 2019, 187, 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- De Wilde, P.; Tian, W. Building Energy Simulation and Model Calibration. Energy and Buildings 2018, 174, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Amasyali, K.; El-Gohary, N.M. Machine Learning Algorithms in Building Energy Modeling and Optimization. Energy and Buildings 2020, 223, 110063. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Agarwal, P.; Liu, Y. Integration of Machine Learning in Building Energy Performance Optimization. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 131, 110002. [Google Scholar]

- Tzempelikos, A.; Athienitis, A. Addressing Uncertainty in Building Energy Modeling. Energy and Buildings 2021, 235, 110563. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lee, S. Standardization of Building Energy Assessment Methods. Energy and Buildings 2019, 191, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Santin, O.; Itard, L. Validation of Building Energy Models. Energy and Buildings 2020, 229, 110414. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J.A.; Patel, R.; Ma, L. Multidisciplinary Collaboration for Energy-Efficient Buildings. Journal of Building Performance 2020, 11, 132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Enhancing Energy Efficiency in Building Design: A Comprehensive Review of Advanced Materials, Renewable Solutions, and Smart Technologies 2021.

- Azari, R.; Abbasabadi, M. Challenges and Opportunities in Energy-Efficient Construction: Cost Implications and Regulatory Barriers 2018.

- Hong, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L. Overcoming Barriers to Energy-Efficient Building Practices: The Need for Cost-Effective Solutions and Harmonized Regulatory Frameworks 2019.

- Babaei, S.; Saeed, M.; Gholami, H. Integration of Artificial Intelligence and Smart Sensors for Building Energy Optimization: Current State and Future Directions 2021.

- Azhar, S.; Khalfan, M.; Al-Mohannadi, K. Enhancing Building Energy Efficiency through Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Predictive Algorithms 2019.

- García-Sanz-Calcedo, J.; Rodríguez, D.; Llorente, R. Circular Economy Principles in Building Design and Operation: A Pathway to Sustainable Construction Practices 2021.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).