Introduction

New technologies and social networks satisfy our need to be in contact with people. However, due to the addictive potential of the brain towards pleasure, power and information, the negative part is the appearance of addiction problems due to the abusive use of these tools [

1].

According to him Spanish Observatory of Drugs and Addictions, addiction to video games and games are the only two addictions without substances [

2]. However, when talking about social media addiction, the only reference is made to “problematic internet use” without including it in diagnostic manuals [

3,

4].

The abuse of information and communication technologies (ICT) is the external involvement of human beings with technology related to the Internet, computer, mobile phone, video games, etc., [

5] characterized by the high frequency of their use, the loss of control by the person and the dependency relationship that is established with this technology [

6]. It is a pattern of behavior characterized by the loss of control over the use of the Internet, whose behavior leads to isolation and neglect of social relationships, academic activities, recreational activities, health and personal hygiene [

7].

Access to these tools is increasing and their use is not without problems; The mobile phone (Smartphone) has become the most used technology, and its use is being a cause for concern in the field of research and institutions [

8]. The use of this tool is not a problem in itself, but the problematic relationship established with it is [

9,

10], what leads to conditioning social relationships when the number of hours per day used is high or is done in an uncontrolled manner [

11,

12].

Research in this field has focused on teenagers and young people, detecting the presence of emotional and social behavioral problems related to mobile phone use [

13]. Specifically, it has been observed that both university students and adolescents are the population groups at greatest risk in this regard [

14]. However, we cannot ignore the importance and need to use the mobile phone and the Internet as tools in the classroom for university students [

15,

16].

Regarding the problems associated with the use of ICT, some studies pointed out differences taking into account gender or differences related to cultural factors [

17]. It was found that boys access the internet at earlier stages, while girls access the mobile phone earlier, using it to make calls and communicate via WhatsApp, being in a situation of greater vulnerability. Gender, therefore, becomes a predictor of excessive use of these tools, especially when it comes to intense or problematic use of the mobile phone or the Internet, as the difference between genders increases [

18,

19,

20]. While some studies suggest that being a woman increases the likelihood of developing problematic Internet dependence [

21], others maintain that it acts as a protective factor against the use of new technologies [

22]. Furthermore, other works suggest qualitative gender differences in the use of these technologies, with men having a greater tendency to get involved in games, compared to greater use of social networks by women [

23]. Therefore, the impact of gender on ICT use requires further research [

17].

According to the National Statistics Institute [

24] in Spain, 94.5% of the population aged 16 to 74 has used the internet in the last three months, 0.6 points more than in 2021. The gender gap, which in 2017 was 1.8 points, since 2019 has been disappearing. The use of the Internet is a majority practice among young people, observing that as age increases its use decreases. The activity most carried out on the Internet is instant messaging, such as via WhatsApp.

Given the end of the covid-19 pandemic and the fact that the world population had to confine themselves to their homes, as in the case of Spain for almost three months, or limit contacts, as in the case of Japan, which did not carry out total confinement but did have important restrictions on access to the country, the need for communication, work and academic activity continued through the use of the mobile phone and the Internet, which were the most used means of communication.

The objective of this research is to analyze the use of mobile phones and the internet in Spanish and Japanese university students after the period of the covid-19 pandemic.

Material and methods

Design

A descriptive, exploratory, cross-sectional and observational study has been carried out where qualitative and quantitative variables associated with the abusive use of ICT and academic performance in university students from Spain and Japan have been analyzed after the covid-19 pandemic. .

The sample collection for this study has been carried out at the University of Salamanca (Spain) and the Kyoto University of Foreign Studies (Japan), contacting the deans of each of them and the researchers themselves who teach there. To do this, a questionnaire was provided online through the Google Forms platform, in the language corresponding to each group of students: Spanish or Japanese, without making any type of distinction between the participants.

Evaluation method

In order to collect data, a.semi-structured questionnaire has been used, with 20 questions prepared for the research, consisting of questions that would allow obtaining sociodemographic information, academic performance, general use of ICT and scales designed to measure excessive use of the Internet and mobile phones, such as: Internet Over-use Scale: Internet Over-use Scale (IOS) [

19] and the Mobile Phone Overuse Scale: Cell-Phone Over (COS) [

19], each of these questionnaires consists of 23 questions.

The participants were asked to rate their degree of affectation in relation to the use of the Internet and mobile phone, based on the frequency with which they feel, think or experience what the statements indicate, on a Likert-type scale of never (1) to always (6), some examples being the following: “Do you feel worried about whether you have received a call or message and think about it when your phone is off?”, “How often do you make new friends with people connected to Internet?".

In reference to the psychometric properties of the IOS and COS scales, internal consistency was evaluated using the well-known Cronbach's alpha. And to calculate the total score for each subject, the responses were recoded as 0 if they were equal to or less than “almost never” or as 1 if they were equal to or greater than “sometimes”, the values obtained ranged from 0 to 23. To classify to students with high or low utilization of ICT, the 75th and 25th percentiles were used respectively [

19].

Excessive use of the Internet or mobile phone could be considered pathological, so the DSM-V was used for its evaluation [

25]. In addition to substance-related disorders, the DSM-V also includes pathological gambling, which reflects evidence that gambling behaviors activate reward systems similar to those activated by drugs, producing some behavioral symptoms similar to substance-related disorders. substance consumption and that may be applicable on this occasion.

Statistic analysis

A descriptive analysis was carried out of the main characteristics of the sample used in the study, of the items to determine the perception of academic performance after the covid-19 pandemic, of the general use of ICT, and of the abusive use of both the internet and the mobile phone, in university students. For this, frequency tables and measures of central tendency and dispersion were used. A bar graph was also created to represent information about the media most used by university students.

Differences between quantitative variables were analyzed with the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test for independent samples (students of Spanish and Japanese culture or by sex). Contingency tables were made to record and analyze the relationships between the qualitative variables using the Chi-square test. Significance was determined at the 0.05 level for all statistical tests. For data analysis, the IBM SPSS Statistics package, Version 26.0, was used [

26].

Results

The answers obtained corresponded to 146 subjects from the questionnaire in Spanish and 60 in Japanese, with an average age of 21 years (standard error = 0.43) and a greater participation of women (75.7%). 62.1% of the participants in the study are of Spanish nationality, 26.2% Japanese and the rest of other nationalities such as Mexican (5.3%), Chinese (1.9%) or Korean (1.0%), among others. Taking into account the type of cohabitation, more than 42% of those surveyed live with parents or relatives, 27.2% live with roommates, 15% live alone, almost 8% live with roommates or dorm roommates and the 7.3% live as a couple.

The sample is mainly made up of undergraduate students from the degrees of Fine Arts, Political Science and Public Management, Criminology, Medicine, Psychology, Labor Relations and Human Resources, and 10% are pursuing Master's degrees. The majority of participants enrolled in the first year (20%) and third year of the degree (30%).

General use of information and communication technologies

In relation to the daily use of ICT, less than 15% of students use them for less than 3 hours, 26.2% indicate that the time spent is 3 to 5 hours, more than 46% use them for 5 to 10 hours, 5.3% do it from 10 to 15 hours, and almost 3% say they use them for many hours, too many or even from the moment they get up until they go to bed.

As soon as to the areas where they use ICT the most, being a sample of students, 45.1% of them use ICT for their studies and 2.9% do so in the workplace. 21.8% use ICT to communicate through calls or chats. 23.3% use them to watch series, movies, read, listen to music, etc., and 2.9% to play online games. Almost 80% of students say that they communicate with their family and/or friends every day, and only 2% indicate that they barely do so, or do so once a week.

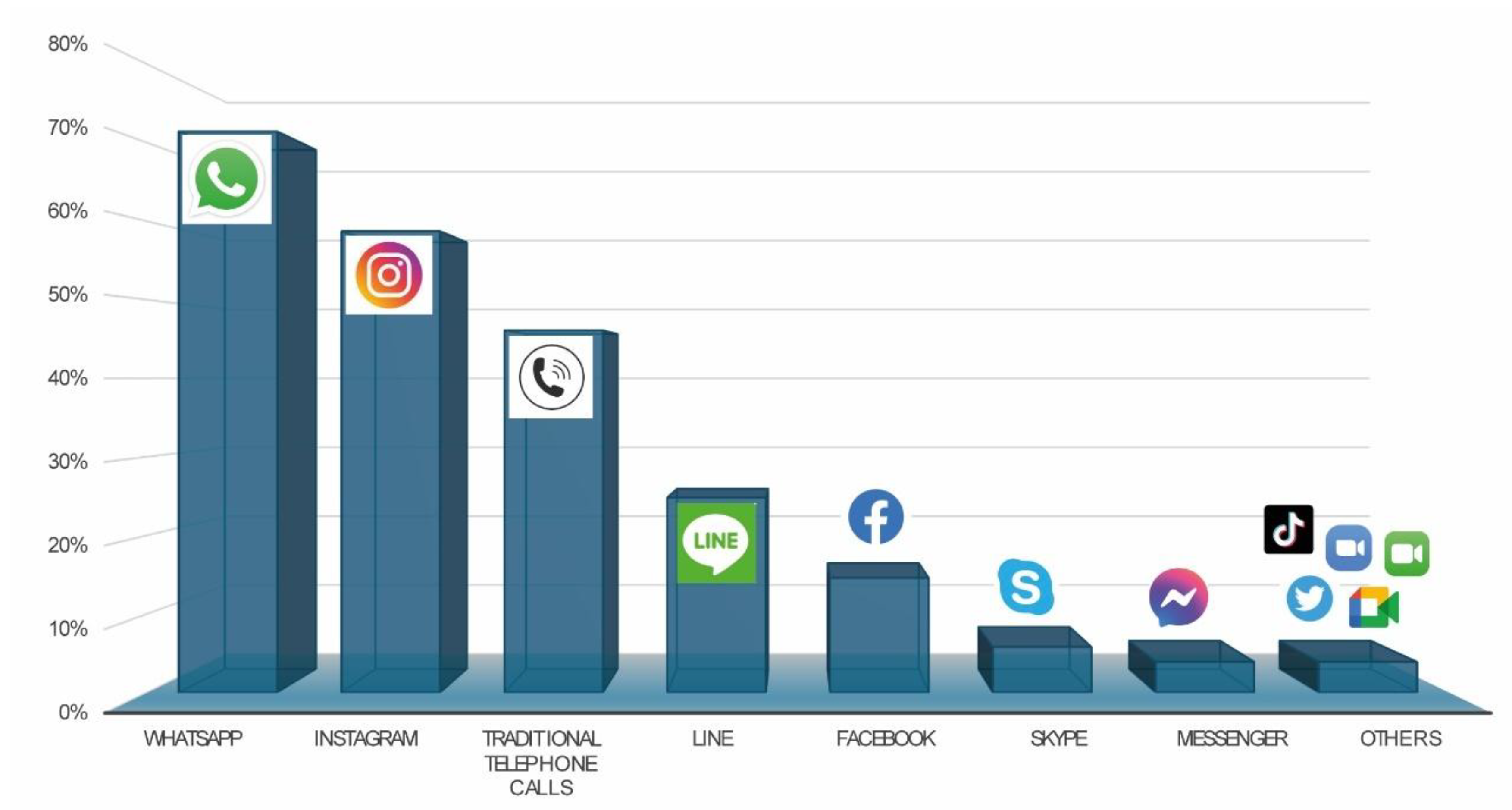

Students use different means to communicate, with the most used means of communication being Whatsapp (71.4%), Instagram (58.7%) and traditional telephone calls (46.1%), followed by Line (24.8%) and Facebook (14.6%). The least used means of communication are Messenger (3.9%), Skype (5.8%) in a certain way, because its use has fallen when other forms of communication and Telegram appear (3.9%), other means of communication they use are Discord, Zoom , Meet, Facetime, Twitter or Tik Tok. (See

Figure 1).

64.6% of the research participants indicate that their free time has not increased as a result of the use of ICT. In relation to consumption, 60.2% indicate that since the beginning of the pandemic their online purchases have increased, consumption being related to food, clothing, books, games, electronic devices, accessories, etc. More than half saw their average monthly online spending increase since the start of the pandemic between 20 and 50 euros, 15% increased it between 51 and 100 euros and almost 4% by more than 100 euros (

Table 1) . Regarding online gambling, only 1% of those surveyed made online bets during the pandemic, almost every day or once every two weeks, with the amount invested in bets being about 20 euros per month.

Table 1 shows that 32% indicated that the use of ICT had changed their eating habits; 13.1% indicate that they eat healthier, 12.1% that they eat more fast food or take-away, and 6.8% snacks, sweets, soft drinks, etc. Furthermore, since the beginning of the pandemic, only 59.7% sleep between 7 and 8 hours a day, 23.3% sleep between 5 and 6, 14.1% more than 8 and almost 3% sleep less than 5 hours. Among the reasons why they believe their sleeping hours have changed, participants refer to aspects related to the pandemic situation itself, such as having to spend more time at home due to the curfew, demotivation and even anhedonia and hopelessness. By not having expectations for the future, feeling listless and due to the need to occupy their time, they sleep more.

Abusive use of the internet in Spanish and Japanese universities

Table 2 reflects the percentages of responses found regarding normal or abusive (pathological) use of the Internet through the application of the IOS scale, taking into account the frequency with which respondents feel, experience or think what the statements the items of said scale indicate, with good internal consistency (α = 0.893).

Themostof university students say they sometimes feel worried about what happens on the Internet, they think about it when they are not connected and abandon activities or tasks they are doing to spend more time connected to the Internet (items 1 and 3). Many of them, 33%, point out that they sometimes connect to the Internet to escape their problems (item 8). Most also indicate that sometimes they stay connected for longer than they initially thought, lose track of time when they are online, or have felt guilty for investing too much time in their connections (items 19, 21, and 22).

The 29.6% of the sample makes excessive use of the Internet, who could be considered pathological users. Comparing the students who responded to the questionnaire in Spanish and in Japanese, statistically significant differences were only observed in the DSM-5 criterion 8 score [

25] which refers to the fact that the subject has endangered or has lost an important relationship, a job, an academic or professional career due to the abusive use of the Internet (Mann-Whitney U = 5231.5; p-value = 0.023). In the rest there is no evidence to say that students from both cultures were different. We have also observed statistically significant differences by sex in the score associated with tolerance according to criterion 1 of the DSM-5 [

25], which refers to the need to invest increasing amounts of time to achieve the desired arousal on the Internet (Mann-Whitney U = 3133; p-value = 0.024).

Table 3 shows that of the students who responded to the questionnaire in Japanese, 56.8% use the Internet excessively, while less than half of those who responded in Spanish (42.9%). Among university women, half use the Internet excessively, but among men the percentage is lower (40%).

Abusive use of mobile phones in Spanish and Japanese universities

Table 4 shows the percentages of responses found regarding normal or abusive (pathological) use of the mobile phone through the application of the COS scale. The Cronbach's alpha obtained in the study sample for this scale is α = 0.907, which indicates excellent internal consistency.

Most students sometimes feel worried about whether they have received a call or message and think about it when their phone is off (item 1); they also point out that they use their cell phone to escape from their problems (item 8).Most of them use their mobile phone for longer than they initially thought, they lose track of time when they are using their mobile phone and they have felt guilty for spending too much time using their mobile phone (items 19,21 and 22).

25.2% of the sample makes excessive use of the mobile phone, they could be considered pathological mobile phone users. Statistically significant differences are only observed taking into account sex in the score of theDSM-5 criterion 1 [

25], which refers to the need to invest increasing amounts of time to achieve the desired arousal on the Internet (Mann-Whitney U = 3047.5; p-value = 0.013). In the rest there is no evidence to say that they are different.

In

Table 5, of the students who responded to the questionnaire in Japanese, 51.4% use the mobile phone excessively, and of those who responded in Spanish, 45.5% use the mobile phone excessively. Among university men, 34.6% use the mobile phone excessively, however in women the percentage is higher, more than half of them (54.4%).

Finally,

Table 6 presents the results of crossing the students classified with light or severe use for both the internet (IOS) and the mobile phone (COS). A significant association is observed between both abusive use classification variables (p-value < 0.001). A 48.2% of the sample makes excessive use of the Internet and mobile phones. There are no university students who use the Internet lightly and use the mobile phone excessively. Of those who use the Internet excessively, 87.2% abusein the use of their mobile phones. And of those who use mobile phones excessively, all of them use the Internet excessively.

Discussion

Addiction to the Internet and, by extension, to all technologies related to information and communication, is described as an abusive use that can cause interference or changes in life. In relation to the way of managing the period of the covid-19 pandemic in the Spanish and Japanese population, it was not carried out in the same way, in Spain there was a total confinement of almost three months and Japan maintained restricted activity during the years later, without reaching total confinement.

The Covid-19 pandemic has acted as a catalyst for students' relationship with ICT, as the increase in virtuality and dependence on technology has been exacerbated during this period. This phenomenon raises questions about how the health crisis impacted the addiction to new technologies and the emotional well-being of university students.

An investigation carried out on internet addiction in a sample of young Malaysians detected a high risk of internet addiction, among young people between 18 and 25 years old and especially university students [

27]. In our research, it can be observed, in the same way as in the Malaysian population, that the use of the Internet causes changes, with mild dependence observed in 43.2% of university students, moderate dependence in 51.0%, severe dependence in 4.9% and only 1% made adequate use of the Internet.

If we take into account the time that university students dedicate to new technologies, the results of our research are in line with other research, despite the temporal differences of said studies. The use of new technologies is very high [

28], they point out that the average daily use of new technology was 6.5 hours, and [

3] that the time dedicated to the new technologies was 4.83 hours. As possible explanations for these differences, they point out the age of the samples, the average age being higher, as well as the way of relating to and using the new technologies (they were used more outside of home, a different form of social interaction, or a later arrival to the digital world). On the other hand, in our research, it is important to highlight the use given to these tools by university students, the highest percentage is used for studying, followed by use to watch series, movies, read, listen to music and as a means of communication or chats. In contrast, a very small number use them for online games or as tools for work. In research carried out [

29] as for the frequency of use of the Internet, video games, mobile phones and television, they highlight that almost all students connect to the Internet every day (97.8% of the students at the University of Granada and 99.7% of those at the University of Almería), the use of mobile phones for leisure, 92.59% of Granada university students use their device every day compared to 69.44% of Almeria university students and with respect to daily television use, students from the universities of Granada and Almería have percentages very similar, 56.61% and 60.29% respectively, these results are in line with our research.

It is observed that the abusive use of ICT`s can have a significant impact on the academic performance of university students, as has been pointed out in previous research. Addiction to new technologies can lead to problems such as absenteeism, exam failure and even expulsions, suggesting the need to address this issue comprehensively in educational settings.

In relation to the level of dependency and concern on the part of the students about what is happening on the Internet, according to our results, almost 30% of the sample use the Internet excessively, which could be considered pathological Internet users. The results are in contrast to those obtained in other investigations in which the risk of Internet addiction was low [

30,

31,

32].

With respect to the use of technologies and sex, in our research the results that have been obtained in the IOS questionnaire, mild and severe levels of Internet use occur more in women, these results go in a direction opposite to others research regarding internet addiction.Orozco-Calderon [

33] found that, in the majority of the subjects evaluated, the groups of men with medium and severe addiction had higher scores than women, in the same line as other research that relates gender with internet addiction symptomatology, there is a higher prevalence in men, children and adolescents when compared to women [

34,

35,

36,

37]. Lam and Peng [

32] point out that young men spend more time on the Internet in individual and team activities, games and on adult sites, and that young women use social networks more.

We highlight the importance of considering gender differences in Internet use, as previous studies have shown that there are disparities in the way men and women use ICTs. These findings underscore the need to design specific strategies that address the different ways in which genders interact with technology.

Our study highlights the need to continue researching the use and abuse of ICTs in educational contexts, considering factors such as academic performance, gender differences and the context of the pandemic. These findings can be fundamental for the design of interventions and policies that promote a healthy and balanced use of information and communication technologies in the student population.

Conclusions

1. The Covid-19 pandemic has increased the dependence on ICTs in the lives of university students, raising the need to proactively address the potential negative effects of this increased exposure to technology. A negative impact has been observed on the academic performance of university students and their habits, suggesting the need to implement prevention and awareness strategies to encourage healthy use of technology.

2. Significant increase in ICT addiction among young adults, with almost 30% being pathological Internet users and 25.2% considered pathological mobile phone users.

3. There is a clear association between excessive use of the Internet and abusive use of the mobile phone, with women being the most abusive users. Significant differences are evident in the use of ICT between men and women, which highlights the importance of considering gender approaches when designing interventions related to the use of ICTs in educational environments.

4. Despite the adaptations in teaching during the pandemic, the majority of participants (68.9%) did not perceive improvements in their academic performance, which suggests the need to review and adjust educational strategies in virtual environments.

5. There are significant differences in the use of the Internet and mobile phone between Spanish and Japanese students, which highlights the influence of cultural factors on technological dependence. These disparities can have an impact on the academic performance and mental health of young people.

6. Increased use of ICTs during the pandemic has led to increased problematic use of the internet and mobile phones. These findings suggest the need to address ICTs addiction and its potential consequences on mental health and academic performance.

In summary, Internet addiction and the abusive use of technologies are relevant phenomena that affect university students, with gender and cultural differences in their manifestation. It is essential to address these issues to promote healthy use of technology and prevent potential negative impacts on young people's academic and personal lives.

We believe it is necessary to continue researching the use and abuse of ICTs, considering cultural differences, to better understand how these technologies impact the academic and personal lives of university students and thus better understand the implications of the use of ICTs on emotional well-being. , social and academic of university students, as well as to develop effective strategies for the prevention and treatment of possible technological addictions.

Study biases and limitations

Among the limitations that we can point out of this study is the size of the sample and the difference between the Spanish and Japanese populations, it would be advisable to continue with research in relation to the use and abuse of information and communication technologies.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the informants who participated in the study and the participating universities for their collaboration.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research has been approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Salamanca, through research protocol number: CBE-EP2 1 P-696 28032022.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors of this article have no conflicts of interest to declare. This research did not receive any specific agency grant or funding from the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Martín Herrero, JA (2021). Bio-psycho-social intervention in addictions. McGraw Hill. Aula Magna Spain.

- Spanish Observatory of Drugs and Addictions. Report on Behavioral Disorders (2022). Gambling with money, use of video games and compulsive use of the Internet in surveys of drugs and other addictions in Spain AGES and STUDIES. Madrid: Ministry of Health. Government Delegation for the National Drug Plan.

- Labrador, F.J.; Villadangos, S.M.; Crespo, M.; Becoña, E. Design and validation of the new technologies problematic use questionnaire. An. De Psicol. 2013, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, O.; Honrubia-Serrano, M.L.; Freixa-Blanxart, M. [Spanish adaptation of the "Mobile Phone Problem Use Scale" for adolescent population]. . 2012, 24, 123–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Carbonell, X. , Fargues, MB, Rosell, MC, Lusar, AC & Oberst, U. (2008). Internet and mobile addiction: fad or disorder? Addictions, 20(2), 149-159.

- Fernández-Montalvo, J. , & López-Goñi, JJ (2010). Addictions without drugs: characteristics and methods of intervention. FOCAD. Continuing Distance Learning. General Council of Official Colleges of Psychologists, 8(2).

- Arab, LE, & Díaz, GA, (2015). Impact of social networks and the internet on adolescence, positive and negative aspects.Las Condes Clinic Medical Magazine Volume 26, Issue 1,January–February.

- Salgado, P.G.; Boubeta, A.R.; Tobío, T.B.; Mallou, J.V.; Couto, C.B. Evaluation and early detection of problematic Internet use in adolescents. Psicothema 2014, 1, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chóliz, M. Mobile Phone Addiction: A Point Of Issuse. Addiction 2010, 105, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echeburúa, E. , Labrador, FJ, & Becoña, E. (2009). Addiction to new technologies in young people and adolescents. Madrid: Pyramid.

- Bianchi, A.; Phillips, J.G. Psychological Predictors of Problem Mobile Phone Use. CyberPsychology Behav. 2005, 8, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamibeppu, K.; Sugiura, H. Impact of the Mobile Phone on Junior High-School Students' Friendships in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. CyberPsychology Behav. 2005, 8, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrero, E. , Rodríguez, MT & Ruíz, JM (2012). Mobile phone addiction or abuse. Literature review. Addictions, 24, 139-152. doi.org/10.20882/addictions.107.

- Weare, K. What impact is information technology having on our young people's health and well-being? Heal. Educ. 2004, 104, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A.; Barkley, J.E.; Karpinski, A.C. The Relationship Between Cell Phone Use and Academic Performance in a Sample of U.S. College Students. SAGE Open 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindell, D.R.; Bohlander, R.W. The Use and Abuse of Cell Phones and Text Messaging in the Classroom: A Survey of College Students. Coll. Teach. 2012, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimadevilla, R.; Jenaro, C.; Flores, N. IMPACT ON PSYCHOLOGICAL HEALTH OF INTERNET AND MOBILE PHONE ABUSE IN A SPANISH SAMPLE OF SECONDARY STUDENTS. Rev. Argent. DE Clin. Psicol. 2019, 28, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, X. , Fúster, H., Chamarro, A., & Oberst, U. (2012). Internet and mobile addiction: a review of Spanish empirical studies. Psychologist Papers, 33(2), 82-89.

- Jenaro, C.; Flores, N.; Gómez-Vela, M.; González-Gil, F.; Caballo, C. Problematic internet and cell-phone use: Psychological, behavioral, and health correlates. Addict. Res. Theory 2007, 15, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martínez, M.; Otero, A. Factors Associated with Cell Phone Use in Adolescents in the Community of Madrid (Spain). CyberPsychology Behav. 2009, 12, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boubeta, A.R.; Ferreiro, S.G.; Salgado, P.G.; Couto, C.B. Variables asociadas al uso problemático de Internet entre adolescentes. Heal. Addict. y Drog. 2015, 15, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Olivares, R. , Lucena, V., Pino, MJ & Herruzo, J. (2010). Analysis of behaviors related to the use/abuse of the Internet, mobile phone, shopping and gaming in university students. Addictions, 22(4), 301-310.

- Fernández-Villa, T. , Alguacil, J., Almaraz, A., Cancela, JM, Delgado, M. & García, M. (2015). Problematic Internet use in university students: associated factors and gender differences. Addictions, 27(4), 265-275.

- National Institute of Statistics (2022). Survey on Equipment and Use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in Homes Year 2022. Press releases, 1-15. https://www.ine.es/prensa/tich_2022.

- Psychiatric Association, A. (2014). DSM-5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Madrid: Pan-American Medical.

- IBM Corp. (2019). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 26.0; IBM Corp [Computer Software]: Armonk, NY, USA.

- Kapahi, A.; Ling, C.S.; Ramadass, S.; Abdullah, N. Internet Addiction in Malaysia Causes and Effects. iBusiness 2013, 5, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrador, FJ & Villadangos, SM (2009). Addiction to new technologies in adolescents and young people. In E. Echeburúa, FJ Labrador and E. Becoña (Dir.), Addiction to new technologies in young people and adolescents (pp. 45-71). Madrid: Pyramid.

- Sánchez, Á. M. Ú. , Ferrandiz, DA, Valdecasas, BFG, & De la Cruz Campos, JC (2022). Comparative study on the use of new technologies between two Andalusian faculties of Education. Interuniversity magazine of teacher training. Continuation of the old Normal Schools Magazine, 98(36.2).

- Cao, F.; Su, L. Internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: prevalence and psychological features. Child: Care, Heal. Dev. 2006, 33, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilt, JA, de Korniejczuk, RB, & Collins, E. (2015). Internet addiction in Mexican university students. University Research Journal, 4(2).

- Lam, L.T. , & Peng, Z.W. (2010). Effect of pathological use of the internet on adolescent mental health: a prospective study. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 164(10), 901-906.

- Orozco-Calderón, G. (2021). Gender and internet addiction in Mexican university students. Science & Future, 11(1), 116-134.

- Dufour, M.; Brunelle, N.; Tremblay, J.; Leclerc, D.; Cousineau, M.-M.; Khazaal, Y.; Légaré, A.-A.; Rousseau, M.; Berbiche, D. Gender Difference in Internet Use and Internet Problems among Quebec High School Students. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, Y.-M.; Hwang, W.J. Gender Differences in Internet Addiction Associated with Psychological Health Indicators Among Adolescents Using a National Web-based Survey. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Addict. 2014, 12, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, B.; Karthik, S.; Pal, G.K.; Menon, V. Gender Variation in the Prevalence of Internet Addiction and Impact of Internet Addiction on Reaction Time and Heart Rate Variability in Medical College Students. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2019, 13, CC1–CC4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, A.M.; Idemudia, E.S. Gender difference, class level and the role of internet addiction and loneliness on sexual compulsivity among secondary school students. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2017, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).