1. Introduction

Radiation exposure from environmental, medical, and occupational sources led to disastrous health consequences. It could also result in cell damage, genomic instability, and apoptosis. Radiation-induced ionization; hence, it caused DNA damage and dysfunction of cells. Applications of its hazardous consequences pertained to cancer therapies, space expeditions, and workplace safety concerns. Such risks brought into perspective the urgent need for practical approaches to mitigate the deleterious actions of radiation. Over the years, some types of protection have been suggested by experts. They ranged from simple natural compounds to highly sophisticated biotechnological interventions. For instance, the seed extract of

Pycnanthus angolensis Warb protected against X-ray damage [

1]. The study demonstrated its capability of diminishing cell death in radiosensitive cells. Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated that adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) significantly alleviate radiation-induced lung injury by suppressing the TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway, thereby reducing fibrotic marker expression and restoring pulmonary redox homeostasis [

2,

3]. Other studies have highlighted exosomes and mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants as promising strategies for radiation protection, underlining the importance of diverse approaches that include natural antioxidants, exosomes, and autophagy inducers [

4,

5]. These could protect the cells from radiation.

The thioredoxin (Trx) system is indispensable to maintaining the redox balance of cells. It protects cells against oxidative stress. The Trx system has two constituents, Trx and TrxR. Trx is an important and potent antioxidant. TrxR reduces Trx to a functional form, Thereby, enabling Trx to participate in processes such as apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis [

6,

7,

8]. Many diseases have been associated with the dysregulation of the Trx system. Cancers and neurodegenerative diseases included [

9]. Post-translational modifications such as S-nitrosation are also taken part in by both Trx and TrxR [

10]. Thus, showing the potential importance of cellular homeostasis and function. The Trx-TrxR system protects the cells against oxidative stress. Therefore, it became a probable target for therapies aimed at lowering the radiation damage produced by ROS and oxidative stress.

HKL is a biphenolic Magnolia plant alkaloid and, more recently, gained prominence due to its multi-targeted pharmacological activity under the pretence of anti-cancerous, anti-inflammatory, and anti-oxidative activity [

11]. Honokiol has been recently reported to rescue neurodegeneration in hippocampal neurons in Alzheimer's disease by demonstrating SIRT3-induced mitochondrial autophagy, reduction in ROS quantity, and enhancement of the mitochondrial function [

12]. Besides this, Honokiol also suppressed neurodegeneration by suppressing oxidative stress and mitochondrial activation of function in mutant SOD1 cell and mouse models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [

13]. Honokiol is also resistant to some environmental damages; antioxidant mechanisms including SIRT3/SOD2 suppression of cigarette smoke-induced damage [

14]. It was also discovered to reverse radiation-induced premature ovarian failure by activating Nrf2 signaling [

15]. It also promotes ROS production and results in mitochondrial DNA damage and apoptosis in C2C12 myoblasts by changing oxidative stress levels [

16]. Reversal of drug resistance to chemotherapy is the second function. HKL was supposed to reverse doxorubicin resistance through the miR-188-5p/FBXW7/c-Myc pathway [

17]. The experiment confirmed that HKL possessed a multicomponent effect. Therefore, it would cause cancer cell death and formation of a protection against radiational damage.

In this study, we evaluated the radioprotective effects of HKL in particular its possible modulation of the redox balance of the TrxR/Trx system. Theoretically, HKL could be seen as reducing the damage brought about by ionizing radiation by increasing the antioxidant capacity of the Trx system and providing a novel therapeutic strategy in radiation protection. Such mechanisms would be based on the modulation of TrxR/Trx systems by HKL. Once the molecular mechanisms behind these modulations are better understood, interventions against radiation-related diseases in cancer therapy and space explorations, where ionizing radiation poses significant challenges, may be more effective. This study strengthens our perception concerning the protection mechanism of the Trx system against radiation as well as provides an opportunity to open wider viewpoints connected to the utilization of natural compounds for disease control, specifically oxidative-stress-related ones. Thus, we attempt the first insights of the application of HKLs as radioprotectors and show some visions of the newest therapeutic strategy.

2. Results

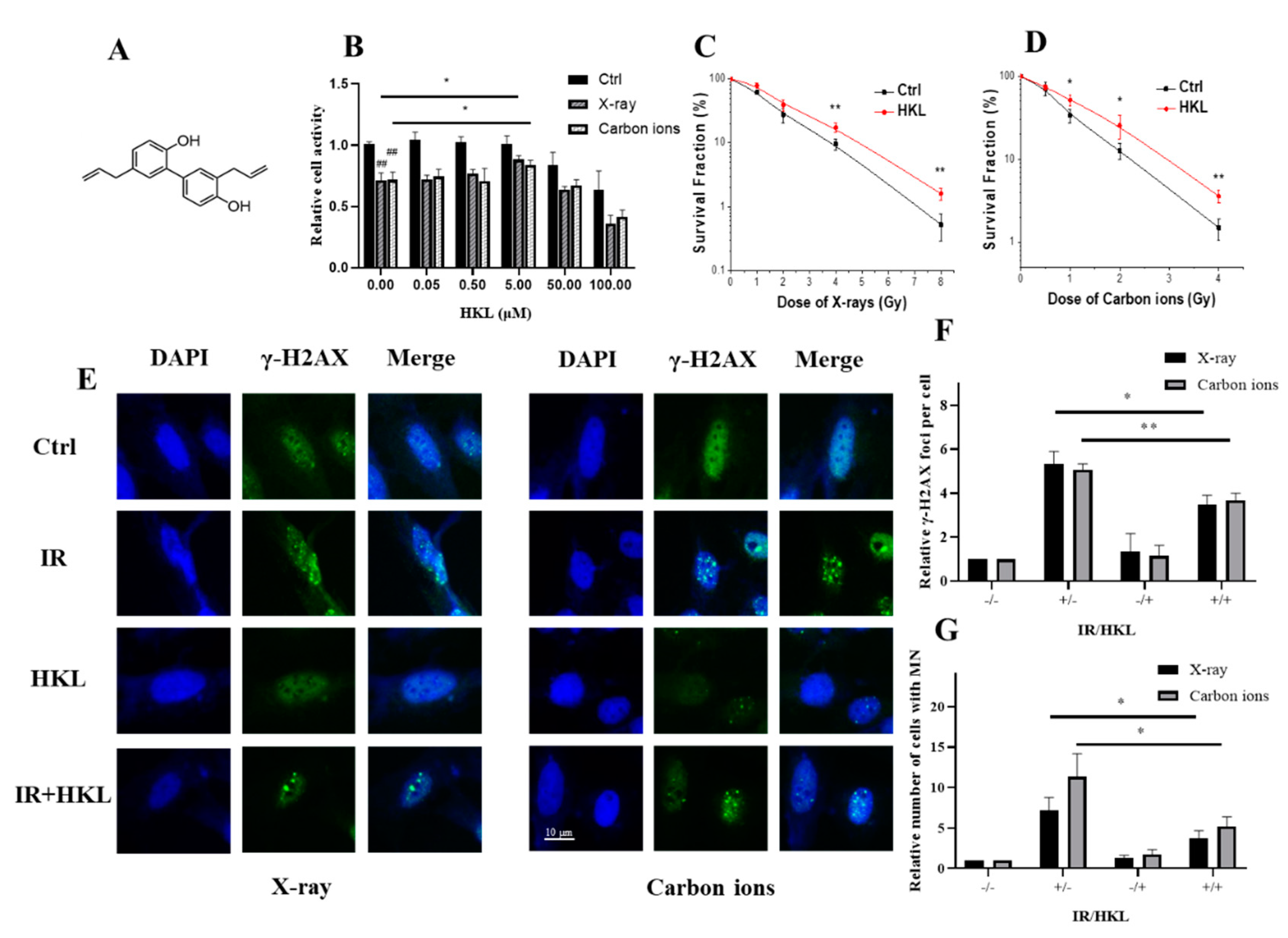

1. Protective Effect of HKL Pretreatment on Ionizing Radiation-Induced Cellular Damage

To investigate the protective role of HKL against ionizing radiation-induced cellular damage, several assays were conducted, including MTT assay, colony formation, micronucleus, and γ-H2AX immunofluorescence analysis. The results of the MTT assay demonstrated that cell viability was significantly enhanced in Beas-2B cells pretreated with HKL under different conditions. The relative cell viability significantly increased upon pretreatment with HKL after exposure to X-ray or carbon ions, especially at a concentration of 5 µM (HKL,

P < 0.05) compared with the control group (

Figure 1B). Colony formation assay further confirmed the enhancement of HKL on irradiated cell survival fraction for different doses of radiation with higher colony numbers in HKL-pretreated groups compared to that of irradiated controls (

Figure 1C,D).

Micronucleus formation analysis (

Figure 1G) showed that HKL+ IR treatment resulted in a significant decrease in the frequency of radiation-induced micronuclei, reflecting reduced chromosomal damage in HKL pretreated cells as compared with the non-treated irradiated cells (

P < 0.05). Similarly, γ-H2AX foci analysis (

Figure 1E,F) showed significantly fewer γ-H2AX-positive cells in the HKL-treated groups than in untreated irradiated cells, indicating fewer DNA double-strand breaks (

P < 0.01).

Collectively, these findings demonstrated the cytoprotective effects of HKL, reflected in enhanced cell survival, and reduced chromosomal damage under radiation stress.

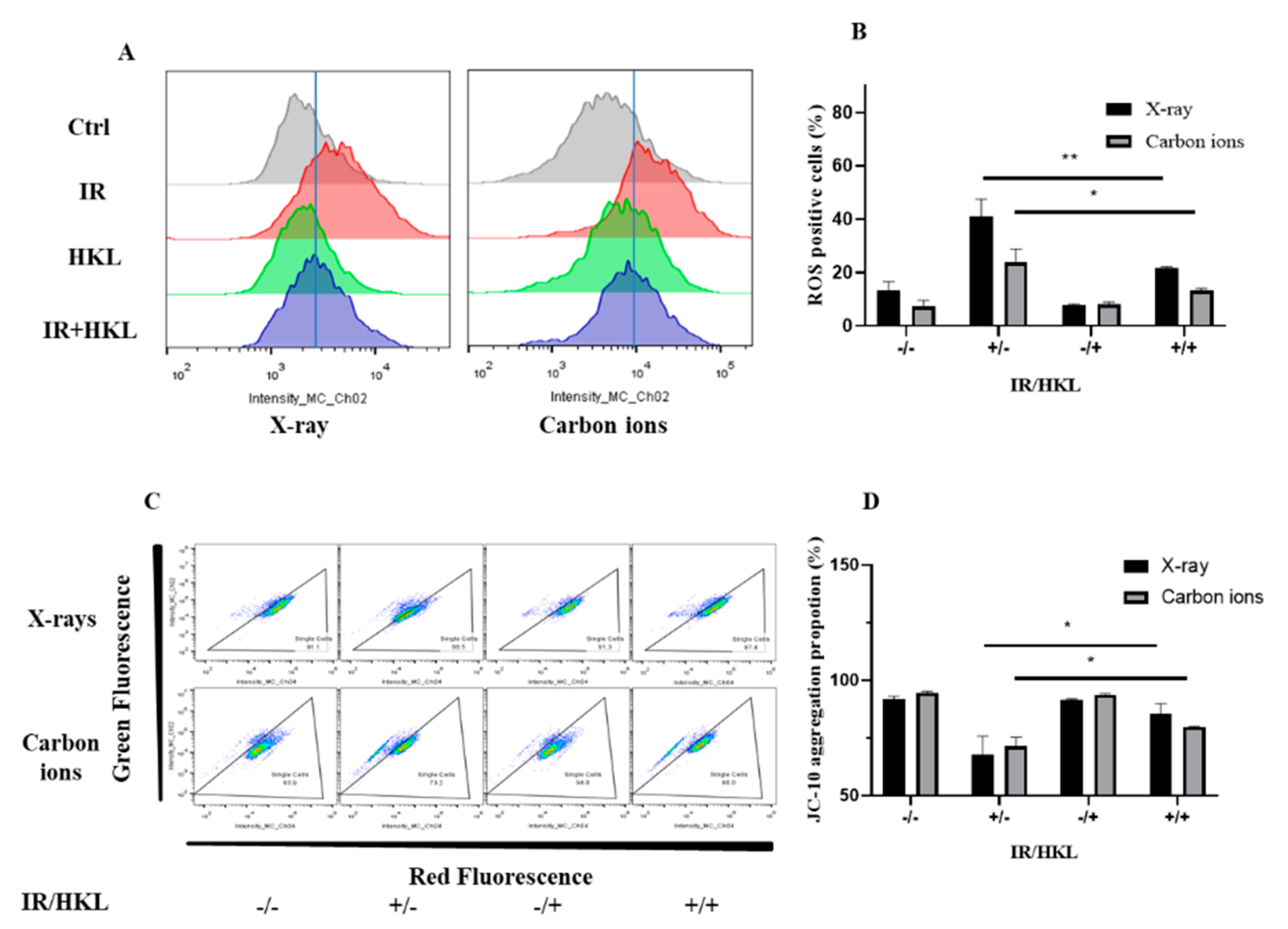

2. Effect of HKL Pretreatment on Cellular Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

The influence of HKL pretreatment on the generation of ionizing radiation-induced ROS in BEAS-2b cells was investigated using the DCFH-DA fluorescence probe method. To further study the protective effect of HKL on ionizing radiation-induced oxidative stress and mitochondrial injury, intracellular ROS was measured by the DCFH-DA fluorescence probe method and mitochondrial membrane potential was detected by JC-10 flow cytometry in this study. The intracellular ROS was significantly elevated after ionizing radiation as shown in the results of the DCFH-DA fluorescence probe method. Compared to the IR group, there was a significant decrease in the ROS levels of the HKL+IR treated group, with a statistical difference of

P < 0.05 (

Figure 2A,B). Therefore, HKL effectively protects against ionizing radiation-induced oxidative stress by reducing cellular ROS generation.

In addition, ionizing radiation significantly decreased mitochondrial membrane potential from the JC-10 flow cytometry analysis, while a significantly higher mitochondrial membrane potential was shown in the cells of the HKL+IR treatment group, as compared with the IR group (P < 0.01) (C,D). This proved that HKL protected the mitochondria and thus alleviated mitochondrial damage caused by ionizing radiation.

In conclusion, the pre-treatment of HKL lowered the intracellular level of ROS. In addition, HKL prevented the dissipating effect of ionizing radiation against mitochondrial membrane potential. This demonstrated that HKL protects ionizing radiation by maintaining cellular redox balance, thereby preventing radiation damage in living cells. Overall, the experimental evidence supports the potential of HKL as a radioprotective agent.

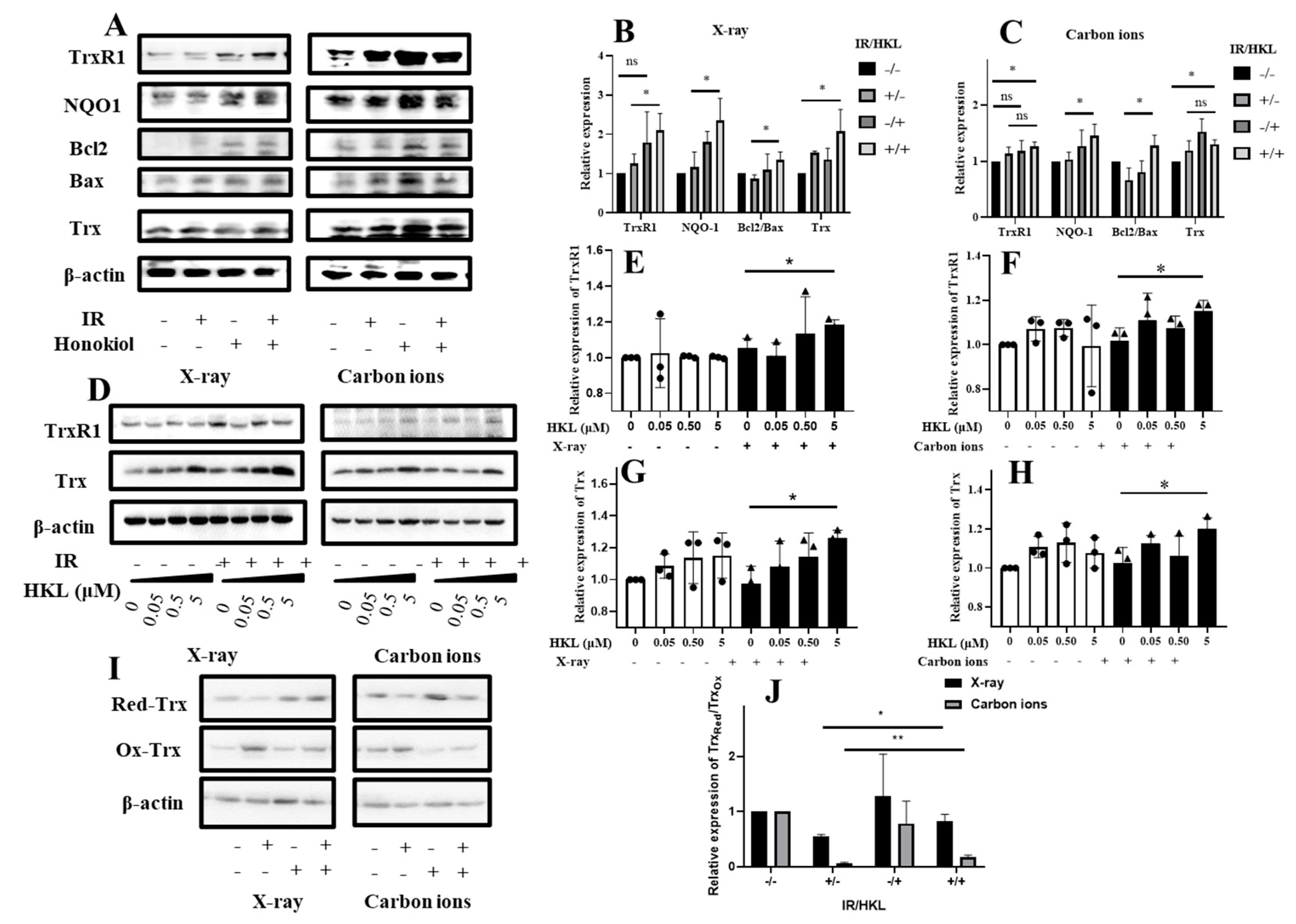

3. HKL Pretreatment Modulates the Redox State of Trx in Cells Exposed to Ionizing Radiation

To determine how HKL pretreatment would affect the Trx redox state in cells exposed to ionizing radiation, we performed a Western blot analysis of the Trx redox state in these cells. The effect of HKL pretreatment on the redox state of Trx after exposure to ionizing radiation was determined using Western blot analysis (

Figure 3). The results indicated that IR treatment altered the expression of TrxR1, NOQ1, Bcl2, and Bax proteins. HKL pretreatment significantly modulated these proteins, which were more prominent in the IR+HKL group. Further quantitative analysis (

Figure 3A–C) confirmed the HKL pretreatment regulatory effect on the expression of TrxR1, NOQ1, Bcl2/Bax, and Trx proteins. Compared with the IR-only treatment, expression levels of these proteins in the IR+HKL group were much closer to the control group, indicating that HKL pretreatment helps maintain the reduced state of Trx proteins. Furthermore, the expression of TrxR1 and Trx proteins following increased doses of HKL pre-exposure were estimated in carbon ions and X-ray exposure (

Figure 3D). Indeed, these experiments showed that HKL pre-exposure significantly increased the expressions of TrxR1 and Trx proteins in general, in particular at doses ranging between 0.05 and 5 µM HKL(

Figure 3E–H). Further confirmation was obtained with Western blot analysis of the regulatory effect of HKL pretreatment on the redox state of Trx (

Figure 3I,J). Compared to the IR-alone treatment group, the content of reduced Trx (Ox-Trx) was obviously higher, and that of oxidized Trx (Red-Trx) was lower in the IR+HKL group. The results indicate the protective effects of the HKL preconditioning on the Trx proteins against oxidative stress injury. In summary, HKL pretreatment altered the redox state of Trx in cells exposed to ionizing radiation. This might contribute to the decrease in oxidative stress and the protection of cells against radiation injury. These results provided new insights into using HKL as a radioprotective agent.

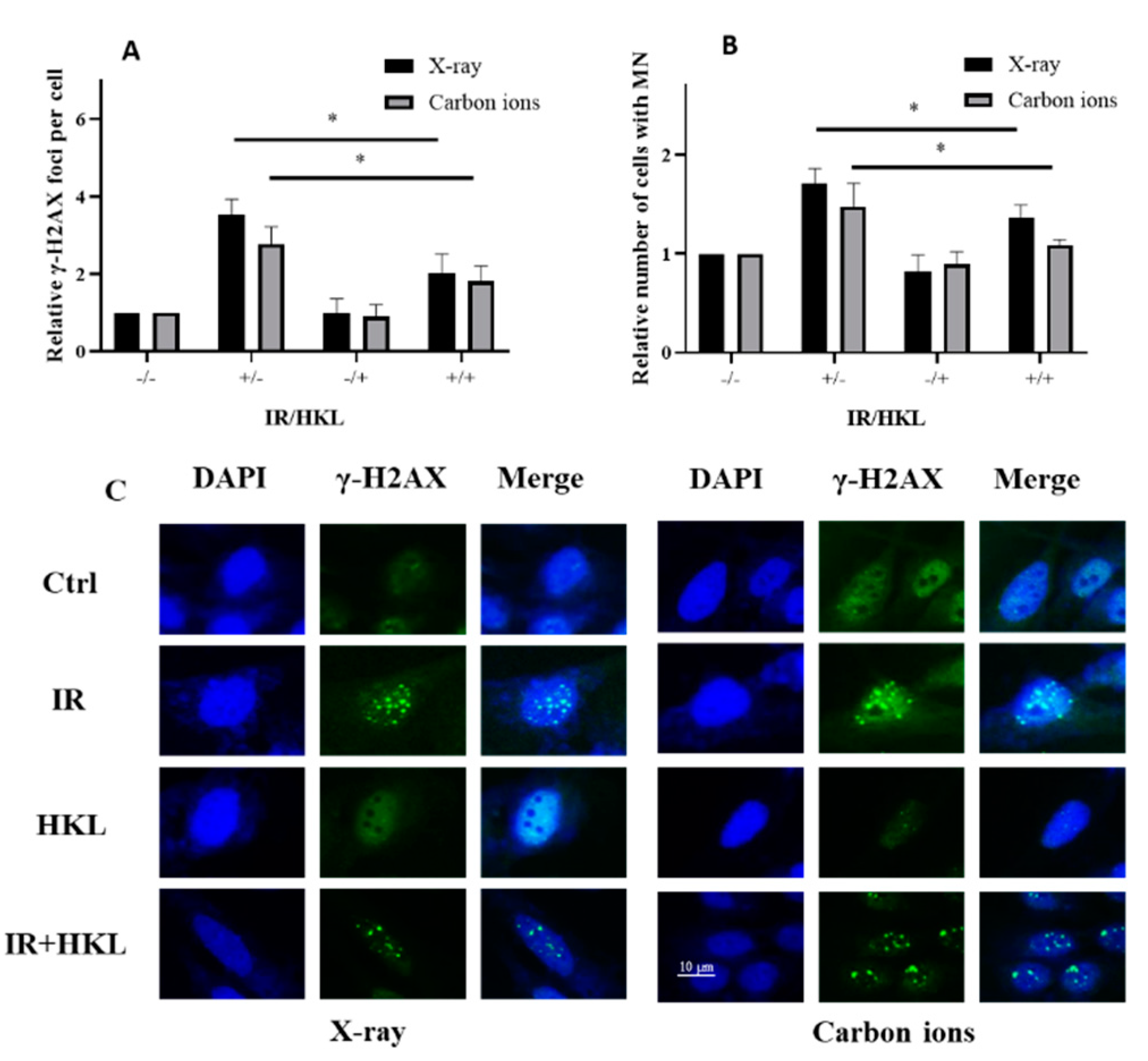

4. HKL Pretreatment Alleviates the Bystander Effect Induced by Ionizing Radiation

To investigate the HKL pretreatment role in the mitigation of the ionizing radiation-induced bystander effect; a coculture system in which the effects induced from the radiation-exposed cells on the unirradiated cells nearby was established. The induction in their neighbors that were not exposed, through the secretion of some reactive molecules including cytokines and ROS by the ionizing radiation-exposed cells, was one of the well-recognized bystander effects. Using γ-H2AX immunofluorescence staining, we assessed the impact of HKL pretreatment on ionizing radiation-induced bystander effects (

Figure 4A,C). The results showed that, compared to the control group, ionizing radiation treatment increased the number of γ-H2AX foci, indicating increased DNA damage. However, HKL pretreatment significantly reduced the number of γ-H2AX foci induced by ionizing radiation, especially in the IR+HKL group, suggesting that HKL pretreatment helped alleviate DNA damage. We further investigated cytotoxic states through enumeration of micronucleus-forming cells (

Figure 4B). Ionizing radiation increased MN-forming cell numbers, and this was significantly decreased by the pretreatment with HKL. In the group irradiated with IR after pre-treatment with HKL, the number of MN-forming cells was comparable to those in the control groups. These findings indicated that the pretreatment with HKL protected against radiation-induced cytotoxicity. These results confirmed that HKL pre-exposure significantly diminished the ionizing radiation-induced bystander effect and further pointed toward its role as a radioprotector.

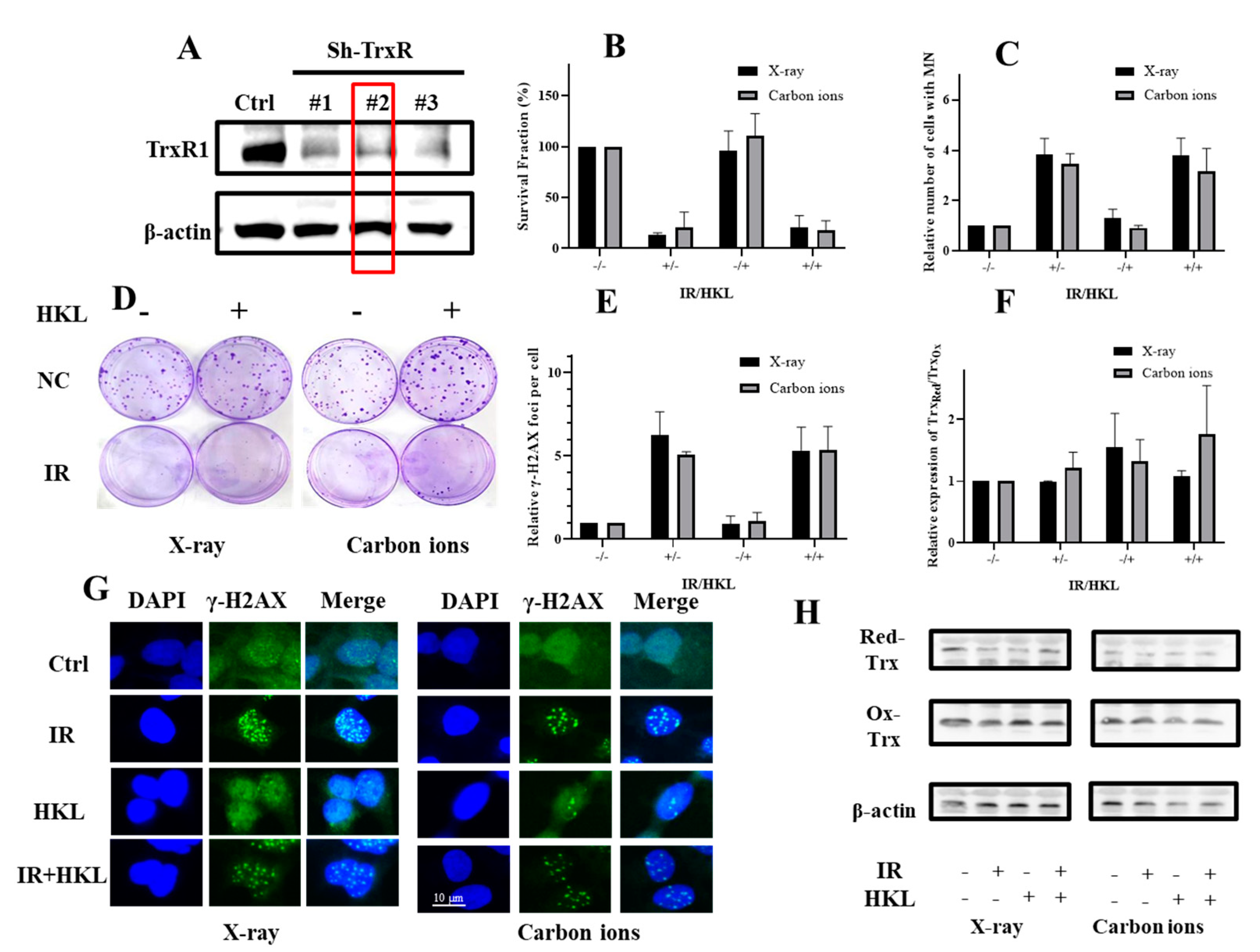

5. HKL Pretreatment Does Not Significantly Reduce Radiation-Induced Damage in TrxR Knockdown Cells

To investigate whether HKL exerted a radioprotective effect against ionizing radiation in sh-TrxR cells, we measured the survival fractions and DNA damage in sh-TrxR cells with or without HKL pretreatment post-irradiation (

Figure 5). As anticipated, compared with its expression in scrambled control cells, the protein expression of TrxR1 was remarkably down-regulated in the TrxR-knockdown cells as measured by western blotting (

Figure 5A). Stable cell line #2 from the TrxR-knockdown cells was further used for validations in subsequent studies. In addition, there were no significant differences in clonal survival, γ-H2AX focal formation and micronucleus quantification between HKL-treated sh-TrxR cells and untreated sh-TrxR cells after irradiation exposure, indicating that HKL did not reduce the DNA damage of Trxr-deficient cells (

Figure 5B–E,G). Further Western blot analysis revealed that HKL treatment did not restore the redox balance in Sh-TrxR cells exposed to ionizing radiation, further supporting the conclusion that TrxR is essential for HKL’s radioprotective effects (

Figure 5F,H). These results suggested that HKL pretreatment did not significantly increase the survival percentage of the sh-TrxR cells after X-ray or carbon ions irradiation. These data suggested that HKL did not protect against radiation-induced damage in the absence of TrxR.

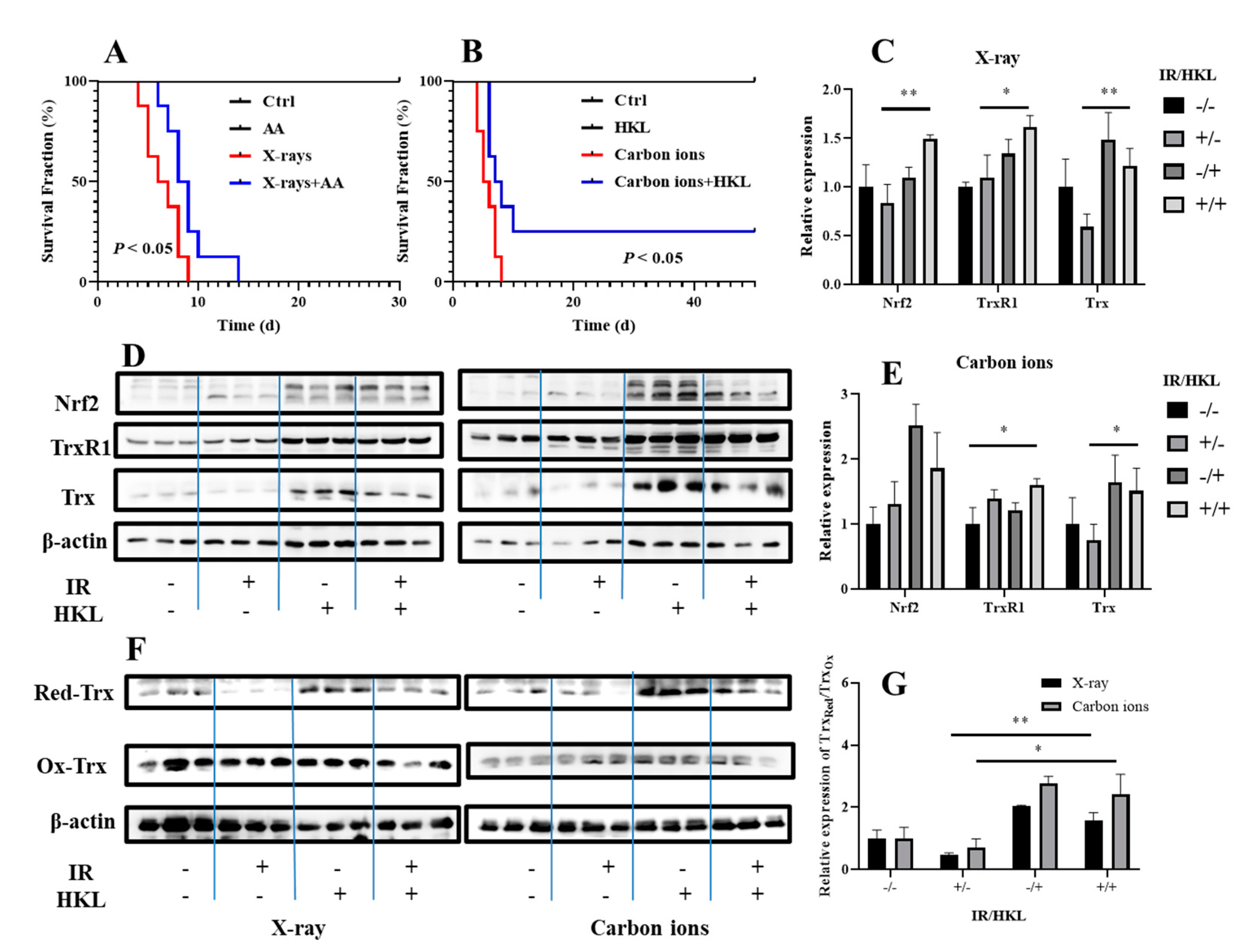

6. HKL Pretreatment Modulates the Redox State of Trx in Mouse Lung Tissue Cells Exposed to Ionizing Radiation and Reduces Radiation-Induced Damage

To verify the radioprotective effects of HKL at the animal level, we investigated the impact of HKL pretreatment on ionizing radiation-induced damage in mouse lung tissue cells and its potential as a radioprotective agent

in vivo. Using C57BL/6 mice as a model, we established an animal model exposed to ionizing radiation and assessed the survival duration of irradiated mice. Survival analysis showed that pre-treatment with HKL significantly improved survival time in mice irradiated with X-ray and also dramatically prolonged the survival time of the mouse exposed to carbon ions (

Figure 6A,B). All of these results thus suggested that HKL is of striking radio-protection potency at the animal model level.

We further prepared lung tissue proteins from irradiated mice and performed Western blotting. These results suggested that compared to the single X-ray-treated group, the combination of HKL and ionizing radiation significantly increased the protein expressions of both Nrf2 and Trx, especially much higher increases of the latter(

Figure 6C–E). Moreover, the combined treatment significantly enhanced the ratio of reduced Trx to oxidized Trx, which may indicate that the HKL pretreatment affects the redox balance of Trx, further reducing oxidative stress and cellular damage induced by ionizing radiation.

In addition, compared to the carbon ions-only treatment group, the combined HKL and ionizing radiation treatment group significantly increased the expression of TrxR and Trx, and significantly increased the ratio of reduced Trx to oxidized Trx (

Figure 6F,G). These results obtained thereby gave evidence that the pretreatment with HKL, through modulation of the TrxR-Trx system, significantly increased the ionizing radiation tolerance of mouse lung tissue cells and protected them from radiation-induced injury by way of regulating the redox state of Trx.

These results supported the fact that HKL pretreatment efficiently protected against ionizing radiation-induced damage through the modulation of the Trx redox state in vivo and is thus a potential candidate for a radioprotective agent.

3. Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the radioprotective action of HKL against ionizing radiation-induced cellular damage, with an emphasis on its regulation of the redox balance of the TrxR/Trx system. Ionizing radiation, including X-ray and carbon ions, has been reported to cause severe oxidative stress, leading to DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and bystander effects, which contribute to an increase in radiation-induced damage [

18,

19,

20]. Our data demonstrated that HKL pretreatment significantly abrogated these toxicities via its effect on the TrxR/Trx system, which is essential for maintaining cellular redox homeostasis.

Our investigations using different in

vitro and in

vivo models of ionizing radiation-induced tissue damage revealed that HKL pretreatment efficiently protects against ionizing radiation. More specifically, HKL protected Beas-2B cells against X-ray- and carbon ion-induced cell death, DNA damage, and markers of oxidative stress. These observations are in agreement with several reports suggesting that antioxidant agents, such as HKL, are capable of modulating their radioprotection capacity by scavenging radiation-induced ROS [

21,

22,

23]. This scavenging enhances the cellular protective mechanisms. Pretreatment with HKL showed a significant increase in cell viability and a decrease in γ-H2AX foci and micronuclei formation, which proves its effectiveness as a radioprotector.

We also emphasized that HKL would stabilize mitochondrial integrity during ionizing radiation-induced oxidative stress. Stabilization of the mitochondrial membrane potential preserved HKL from mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to reduced apoptotic pathways, which are triggered by ROS [

12,

24]. The result was in agreement with previous studies showing the ability of HKL and other antioxidants to neutralize damage to mitochondria, supporting the survival of cells. In relation to these points, both radiation models using X-ray and carbon ions support broad application as a radioprotector.

The TrxR/Trx system plays a vital role in maintaining cellular redox balance and alleviating oxidative stress [

25,

26,

27,

28]. In our study, HKL pretreatment maintained the cellular Trx redox status, which is conducive to DNA repair and decreases oxidative damage after irradiation. These findings confirmed that regulation of the TrxR/Trx system is a requirement for the radioprotective action of HKL. More importantly, the protective action of HKL was significantly compromised in cells with TrxR knockdown, hence indicating that the TrxR/Trx pathway is a prerequisite for its effectiveness. These data are in agreement with previous studies showing the important role of the Trx system in radiation protection.

Ionizing radiation, besides directly damaging irradiated cells, causes a bystander effect, which is manifested as a response of non-irradiated neighboring cells to the stress of signaling emanating from irradiated cells [

29,

30]. Our data have shown that HCL pretreatment reduced the bystander effect through the attenuation of oxidative stress and the elevation of the repair mechanisms in bystander cells. This extended protective effect is of extreme importance for the minimization of overall tissue damage and points out the potential of HKL in the clinic under conditions where radiation exposures take place in heterogeneous cell populations.

The results of in vivo experiments also show that preconditioning with HKL regulated the redox status of Trx in cells of mouse lung tissues exposed to ionizing radiation, which corroborates the results obtained in the in vitro experiments. HKL treatment was also found to prolong the survival time of irradiated mice to a clinically usable extent. Our present results show that natural compounds like HKL might modulate the radioprotection by affecting the TrxR/Trx redox pathway.

4. Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

HKL (purity>98%) was purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd (China) and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma Aldrich, USA) to prepare stock solutions. The final concentration of DMSO in cell culture media was kept below 0.1% to avoid any cytotoxic effects. Other chemicals not specifically mentioned were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Cell Culture

Human bronchial epithelium cell line Beas-2B was purchased from the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology (China). Cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco, USA). All the mediums were supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, USA), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100mg/mL streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

Experiments on Mice Models

Six-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Gansu University of Chinese Medicine (Lanzhou, China) and were housed under a 12-hour light/dark cycle with a standard NIH31 diet (Beijing Keao Xieli Feed Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) and water ad libitum for one week before exposure. All experiments with mice were conducted in accordance with the National Research Council's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Radiation Exposure

Cells were pretreated with varying concentrations of HKL for 24 hours prior to exposure to ionizing radiation. Mice underwent a two-hour pre-treatment with HKL before systemic radiation exposure. Carbon ion (12C6+) beam irradiation (energy: 80 MeV/u, LET: 30 keV/μm) was performed at the biomedical terminal of the Heavy Ion Research Facility in Lanzhou, with a dose rate ranging from 1.0 to 3.0 Gy/min at the Institute of Modern Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences. X-ray irradiation (energy: 225 kV/13.3 mA) was generated by an X-Rad 225 generator (Precision) at a dose rate of approximately 1.0 Gy/min. Unless otherwise specified, in subsequent experiments, cells and mice were exposed to 4Gy (X-ray) or 2Gy (Carbon ions).

Cell Viability Assays

Cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay. Briefly, cells were seeded into 96-well plates and pretreated with HKL for 24 hours. Following radiation exposure, MTT (Beyotime, China) solution was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 4 hours. The extraction buffer (100 μL, containing 0.1% HCl, 10% SDS, and 5% isobutanol) was then used to dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using the Infinite M200 Pro microplate reader (Tecan, Switzerland). Cell survival was calculated by normalizing the absorbance values to those of the control group.

Micronucleus Assay

Micronucleus formation was assessed to evaluate radiation-induced chromosomal damage. Cells were exposed to radiation after HKL pretreatment and were cultured for 24 hours. Cells were then fixed and stained with acridine orange (Beyotime, China). Micronuclei were counted in at least 1000 cells per sample.

Assessment of ROS Levels by DCFH-DA

Intracellular ROS levels were measured using the 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) fluorescence probe (Biosharp, China). Following treatment and ionizing radiation exposure, BEAS-2b cells were incubated with 10 μM DCFH-DA for 30 minutes at 37°C. After the incubation, the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove any unincorporated probe and then resuspended in PBS. ROS generation was quantified using a Merck Millipore FlowSight flow cytometer (Merck Millipore Amis, NJ) at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and emission at 530 nm. The data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, USA) to assess the fluorescence intensity and quantify the ROS levels.

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Measurement by JC-10 Staining

Mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) was assessed using the JC-10 mitochondrial membrane potential detection kit (Beyotime, China). BEAS-2b cells were incubated with 1 μM JC-10 for 30 minutes at 37°C. After incubation, the cells were washed with PBS, and mitochondrial membrane potential was analyzed by Merck Millipore FlowSight flow cytometer (Merck Millipore Amis, NJ). JC-10 accumulates in mitochondria and exhibits a red fluorescence emission when the membrane potential is high and a green fluorescence emission when the membrane potential is low. The results were measured at an excitation wavelength of 515 nm with emission detected at 529 nm (green) and 590 nm (red).

γ-H2AX Immunofluorescence Assay

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) were detected using the γ-H2AX immunofluorescence assay. After radiation exposure, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100. The cells were then incubated with an anti-γ-H2AX primary antibody (Proteintech Group, China) (diluted 1:500), followed by incubation with a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (Proteintech Group, China). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Images were captured using a fluorescence microscope, and the number of γ-H2AX foci per nucleus was quantified.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blotting was performed to evaluate the expression of TrxR, Trx, and other proteins of interest. All antibodies were purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc (China). Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer, and protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protein assay. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were probed with primary antibodies against TrxR, Trx, and β-actin (as a loading control), followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Protein bands were detected with luminal reagent (WBKLS0500; Millipore).

Cellular protein samples were collected, and protein extraction was performed using RIPA buffer, followed by protein quantification using Bradford's method. The quantified cell lysates were then loaded onto PAO-agarose and incubated on a rotary shaker at room temperature for 30 minutes. After incubation, the supernatant containing oxidized Trx was separated and collected. The agarose gel containing reduced Trx was washed with TE buffer, and then reduced Trx was eluted using TE buffer supplemented with 20 mM DMPS. The eluted reduced Trx was subsequently collected. Finally, the prepared samples were analyzed by Western blotting. This involved separating the proteins by 10% SDS-PAGE, followed by electroblotting onto PVDF membranes.

ShRNA Knockdown of TrxR

To investigate the role of TrxR in the protective effects of HKL, cells were transfected with shRNA targeting TrxR using Lipofectamine 3000, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The short hairpin RNA (shRNA) plasmids targeting TrxR1 (shTrxR1) and the nontargeting control (shNT) were kindly provided by Professor Constantinos Koumenis from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania [

32,

33,

35]. Following transfection, single clones were selected, and Western blot analysis was performed to verify the TrxR1 knockdown in the cell lines, which were then used for subsequent experiments. The cells were treated with HKL for 24 hours before being exposed to radiation. The protein expression levels of TrxR and Trx were assessed by Western blot.

Survival Curve of Mice

To evaluate the radioprotective effects of HKL, C57BL/6 mice were divided into four groups: control, HKL treatment, irradiation, and HKL + irradiation. HKL (15 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally 2 hours prior to exposure to 8 Gy X-ray or 5 Gy carbon ions irradiation. Survival was monitored over 50 days, with daily assessments for clinical signs of radiation-induced damage. A Kaplan-Meier survival curve was generated to compare the survival rates among the groups.

Statistical Analysis

All groups were independently repeated at least three times and all data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test for comparison between the two groups. For comparisons among three or more groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used to determine significant differences. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, our data suggested that HKL might be used as a potential radiation protection agent to reduce radiation damage possibly through the maintenance of the TrxR/Trx redox system. HKL attenuates ionizing radiation-induced oxidative stress and preserves mitochondrial function with the upregulation of associated proteins. The findings have indicated that HKL may restrain the oxidative damage induced by ionizing radiation via keeping the redox system TrxR/Trx intact in vitro and in vivo, which involves the origin of X-ray and heavy ion radiation. In a word, the factor that plays a pivotal role in the protective effects of HKL pretreatment against radiation injury is maintaining cellular redox equilibrium. Co-culture experiments showed that HKL could enhance the bystander effect of ionizing radiation remarkably, indicating its possible application as an adjuvant of radiotherapy. Such broad-spectrum radiation protective potential is especially precious for use in space radiation exposure and radiotherapy. Further studies, such as more in vivo studies and clinical trials, surely are needed to fully realize the ionizing radiation protective potential of HKL. These studies will contribute to the optimization of areas where effective radiation protection is urgently needed, such as cancer radiation therapy or space missions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Junmin Zhang and Jianguo Fang; Methodology and investigation: Yaxiong Chen and Ruipeng Shen; Resources and validation: Dan Xu and Qingfeng Wu; Writing—original draft: Yaxiong Chen; Writing—review and editing: Ruipeng Shen and Jianguo Fang; Funding acquisition: Jianguo Fang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12175289).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Achel, D. G.; Alcaraz-Saura, M.; Castillo, J.; Olivares, A.; Alcaraz, M. Radioprotective and Antimutagenic Effects of Pycnanthus Angolensis Warb Seed Extract against Damage Induced by X Rays. J Clin Med 2019, 9(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Sun, W.; Nie, B.; Li, J. J.; Jing, F.; Zhou, X. L.; Ni, X. Y.; Ni, X. C. Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Repair Radiation-Induced Chronic Lung Injury via Inhibiting TGF-β1/Smad 3 Signaling Pathway. Open Med (Wars) 2023, 18(1), 20230850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, S.; Qiang, R.; Lu, J.; Tuo, X.; Yang, X.; Li, X. TGF-beta1-based CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Therapy Attenuates Radiation-induced Lung Injury. Curr Gene Ther 2022, 22(1), 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, X. T.; Liu, X. X.; Wu, Q. F.; Ye, F.; Shi, Z.; Xu, D.; Zhang, J. H.; Dou, Z. H.; Huang, G. M.; Zhang, H.; Sun, C. Mitochondrial-Targeted Antioxidant MitoQ-Mediated Autophagy: A Novel Strategy for Precise Radiation Protection. Antioxidants-Basel 2023, 12 (2), 1-18.

- Xue, J. Q.; Du, R. K.; Ling, S. K.; Song, J. P.; Yuan, X. X.; Liu, C. Z.; Sun, W. J.; Li, Y. H.; Zhong, G. H.; Wang, Y. B.; Yuan, G. D.; Jin, X. Y.; Liu, Z. Z.; Zhao, D. S.; Li, Y. Y.; Xing, W. J.; Fan, Y. Y.; Liu, Z. F.; Pan, J. J.; Zhen, Z.; Zhao, Y. Z.; Yang, Q. N.; Li, J. W.; Chang, Y. Z.; Li, Y. X. Osteoblast Derived Exosomes Alleviate Radiation- Induced Hematopoietic Injury. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorklund, G.; Zou, L. L.; Wang, J.; Chasapis, C. T.; Peana, M. Thioredoxin Reductase as a Pharmacological Target. Pharmacol Res 2021, 174, 105854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunstein, I.; Engelman, R.; Yitzhaki, O.; Ziv, T.; Galardon, E.; Benhar, M. Opposing Effects of Polysulfides and Thioredoxin on Apoptosis through Caspase Persulfidation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2020, 295(11), 3590–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J. Q.; Zhang, Y. J.; Tian, Z. K. Anti-Oxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Anti-Fibrosis Effects of Ganoderic Acid A on Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Nephrotoxicity by Regulating the Trx/TrxR and JAK/ROCK Pathway. Chem Biol Interact 2021, 344, 109529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, A. Q.; Storr, S. J.; Al-hadyan, K.; Rahman, R.; Smith, S.; Grundy, R.; Paine, S.; Martin, S. G. Thioredoxin System Protein Expression Is Associated with Poor Clinical Outcome in Adult and Paediatric Gliomas and Medulloblastomas. Mol Neurobiol 2020, 57(7), 2889–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Qiu, H. Post-Translational S-Nitrosylation of Proteins in Regulating Cardiac Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9(11), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C. P.; Lee, W. L.; Tang, Y. Q.; Yap, W. H. Honokiol: A Review of Its Anticancer Potential and Mechanisms. Cancers 2020, 12(1), 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. T.; Sun, J. M.; Wu, Y. L.; Yang, Y. S.; Zhang, W.; Tian, Y. R. H. Honokiol Relieves Hippocampal Neuronal Damage in Alzheimer's Disease by Activating the SIRT3-Mediated Mitochondrial Autophagy. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30(8), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y. J.; Tang, J. S.; Lan, J. Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. Y.; Chen, Q. Y.; Kang, Y. Y.; Sun, Y.; Feng, X. H.; Wu, L.; Jin, H. T.; Chen, S. Z.; Peng, Y. Honokiol Alleviated Neurodegeneration by Reducing Oxidative Stress and Improving Mitochondrial Function in Mutant SOD1 Cellular and Mouse Models of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Acta Pharm Sin B 2023, 13(2), 577–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Ye, C. Y.; Wang, X. L.; Li, X. T.; Wang, X. X. Honokiol Ameliorates Cigarette Smoke-Induced Damage of Airway Epithelial Cells via the SIRT3/SOD2 Signalling Pathway. J Cell Mol Med 2023, 27(24), 4009–4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, L. L.; Li, F. S.; Yu, H. J.; Xiong, Q.; Hou, Q. X.; Meng, Y. G. Honokiol Alleviates Radiation-Induced Premature Ovarian Failure via Enhancing Nrf2. Am J Reprod Immunol 2023, 90(4), 13769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Choi, S. H.; Jeong, J. W.; Han, M. H.; Lee, H.; Hong, S. H.; Kim, G. Y.; Moon, S. K.; Kim, W. J.; Choi, Y. H. Honokiol Ameliorates Oxidative Stress-Induced DNA Damage and Apoptosis of C2C12 Myoblasts by ROS Generation and Mitochondrial Pathway. Anim Cells Syst 2020, 24(1), 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X. L.; Lou, L. P.; Wang, J.; Xiong, J.; Zhou, S. Honokiol Antagonizes Doxorubicin Resistance in Human Breast Cancer via miR-188-5p/FBXW7/c-Myc Pathway. Cancer Chemoth Pharm 2021, 87(5), 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrador, E.; Montoro, A. Ionizing Radiation, Antioxidant Response and Oxidative Damage: Radiomodulators. Antioxidants-Basel 2023, 12 (6), 1-6.

- Einor, D.; Bonisoli-Alquati, A.; Costantini, D.; Mousseau, T. A.; Moller, A. P. Ionizing Radiation, Antioxidant Response and Oxidative Damage: A Meta-Analysis. Sci Total Environ 2016, 548, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimovitz-Friedman, A.; Mizrachi, A.; Jaimes, E. A. Manipulating Oxidative Stress Following Ionizing Radiation. J Cell Signal 2020, 1(1), 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, H.; Meng, Y. Honokiol Regulates Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress by Promoting the Activation of the Sirtuin 1-Mediated Protein Kinase B Pathway and Ameliorates High Glucose/High Fat-Induced Dysfunction in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. Endocr J 2021, 68(8), 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahm, E. R.; Sakao, K.; Singh, S. V. Honokiol Activates Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated Cytoprotective Autophagy in Human Prostate Cancer Cells. Prostate 2014, 74(12), 1209–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L. L.; Xie, L. P.; Li, L. H.; Zhang, X. W.; Zhang, R. Q.; Wang, H. Z. Reactive Oxygen Species Production and Bax/Bcl-2 Regulation in Honokiol-Induced Apoptosis in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma SMMC-7721 Cells. Environ Toxicol Phar 2009, 28(1), 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Chen, Z. D.; Lin, C. H.; Lin, X. J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J. J. Honokiol Mitigates Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease Nrf2 by Regulating Nrf2 and RIPK3 Signaling Pathways. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 35(7), 551–559. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Folda, A.; Scalcon, V.; Tonolo, F.; Rigobello, M. P.; Bindoli, A. Thiamine Disulfide Derivatives in Thiol Redox Regulation: Role of Thioredoxin and Glutathione Systems. Biofactors 2025, 51(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, M. S.; Ling, H. H.; Setiawan, S. A.; Hardianti, M. S.; Fong, I. H.; Yeh, C. T.; Chen, J. H. Therapeutic Targeting of Thioredoxin Reductase 1 Causes Ferroptosis While Potentiating Anti-PD-1 Efficacy in Head and Neck Cancer. Chem-Biol Interact 2024, 395, 111004.

- Purohit, M. P.; Verma, N. K.; Kar, A. K.; Singh, A.; Ghosh, D.; Patnaik, S. Inhibition of Thioredoxin Reductase by Targeted Selenopolymeric Nanocarriers Synergizes the Therapeutic Efficacy of Doxorubicin in MCF7 Human Breast Cancer Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9(42), 36493–36512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanes-Cuesta, M. A.; Hoi, V.; Ha, R.; Tan, H.; Islam, M. I.; Eftekharpour, E.; Wang, J. F. Redox Protein Thioredoxin Mediates Neurite Outgrowth in Primary Cultured Mouse Cerebral Cortical Neurons. Neuroscience 2024, 537, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinathan, L.; Gopinathan, C. Ionizing Radiation-Induced Cancer: Perplexities of the Bystander Effect. Ecancermedicalscience 2023, 17, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averbeck, D. Low-Dose Non-Targeted Effects and Mitochondrial Control. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(14), 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. M.; Li, X. M.; Han, X.; Liu, R. J.; Fang, J. G. Targeting the Thioredoxin System for Cancer Therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2017, 38(9), 794–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D. Z.; Zhang, B. X.; Yao, J.; Liu, Y. P.; Sun, J. Y.; Ge, C. P.; Peng, S. J.; Fang, J. G. Gambogic Acid Induces Apoptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma SMMC-7721 Cells by Targeting Cytosolic Thioredoxin Reductase. Free Radical Bio Med 2014, 69, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D. Z.; Zhang, J. M.; Yao, J.; Liu, Y. P.; Fang, J. G. Targeting Thioredoxin Reductase by Parthenolide Contributes to Inducing Apoptosis of HeLa Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2016, 291(19), 10021–10031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. M.; Peng, S. J.; Li, X. M.; Liu, R. J.; Han, X.; Fang, J. G. Targeting Thioredoxin Reductase by Plumbagin Contributes to Inducing Apoptosis of HL-60 Cells. Arch Biochem Biophys 2017, 619, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javvadi, P.; Hertan, L.; Kosoff, R.; Datta, T.; Kolev, J.; Mick, R.; Tuttle, S. W.; Koumenis, C. Thioredoxin Reductase-1 Mediates Curcumin-Induced Radiosensitization of Squamous Carcinoma Cells. Cancer Res 2010, 70(5), 1941–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).