A comparative analysis was made to measure the interoperability frameworks' adoption, performance, and regulatory hurdles among the healthcare systems and regional locations. Areas of major priority include standardization deficiencies, security concerns, infrastructure variability, and the roles of blockchain and AI in deploying interoperability. This structured methodology enables a thorough synthesis of existing interoperability innovations to determine key areas of shortfall and make practical policy and technological recommendations.

Key Findings:

Technological Progress: FHIR and ISO 23903:2021 present supplementary methodologies for data structuring and semantic compatibility, while blockchain and AI are being established to drive the secured, automated, and real-time exchange of healthcare information.

Regulatory Landscape: The 2020–2025 WHO Strategy on Digital Health and the 2024 WHO Report on the Transformation of Digital Health underscore the need for harmonized interoperability frameworks, AI governance, and cybersecurity to deliver equitable access to digital healthcare innovations.

Challenges and Barriers: Regulatory fragmentation, security risks, and infrastructure disparities in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) remain key obstacles to achieving full interoperability.

Future Directions: Expanding public-private partnerships, strengthening FHIR-TEFCA alignment, and implementing ISO 23903:2021-based integration models will be critical for ensuring scalable, cross-border health information exchange.

Conclusion: Achieving full-scale interoperability will require a multi-dimensional solution that integrates state-of-the-art technological frameworks with harmonization of the regulatory environment and sustained investments in digital healthcare infrastructure. Convergence of the intersection of FHIR, ISO 23903:2021, AI, and blockchain with international policymaker efforts is a potential opportunity to build a patient-driven, data-driven, and secure digital healthcare ecosystem. Future research should aim at AI-driven models of semantic interoperability, blockchain-enabled governance of the data, and international policymaker coordination to accelerate digital healthcare transformation.

1. Introduction

In an era of digital change, healthcare information interoperability is a catalyst of care that is patient-driven, operationally effective, and evidence-driven decision-making [

1]. Seamless healthcare information exchanges among healthcare providers, insurers, and individuals allow care coordination to occur in real-time, avoid redundancies, and improve patient outcomes [

2]. Achieving full interoperability remains challenging despite its promise due to fragmented data systems, inconsistent standards, privacy concerns, and infrastructure disparities [

3].

Healthcare systems globally are increasingly turning to value-based care models facilitated by complete access to patient health information to reduce medical errors, avoid duplicate testing, and support preventive care approaches [

4]. Research has revealed that a significant number of healthcare providers (more than 70%) indicate that they have insufficient access to complete patient information, which results in inefficiency and medical errors [

5]. It reflects the imperative need for scalable, secure, and standard frameworks of Interoperability.

To address the issue of nationwide Interoperability, the US Office of the National Coordinator of Health IT (ONC) introduced the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA), a governance structure that enables nationwide, secure exchange of healthcare information [

6]. At the international level, the European Union’s Digital Health Action Plan and the World Health Organization (WHO) frameworks are directed toward standardizing healthcare information exchange across borders [

7].

However, the path to full interoperability is obstructed by multiple barriers:

Technological Challenges – Electronic health record (EHR) architecture variability and the lack of standard protocols for data-sharing [

8].

Policy & Governance Failings – Different models of regulation of the transfer of health information between jurisdictions [

6,

9].

Security & Privacy Issues – There is a need to balance the accessibility of information with robust patient information protection measures [

10].

Infrastructure Disparities – Inequal access to technologies that support Interoperability, particularly within resource-constrained environments [

11].

Scope of this Paper

This paper reviews the effect of interoperability on healthcare quality and patient empowerment, examines the challenges to this issue, and looks at emerging technologies such as blockchain, AI, and machine learning to bridge the challenges. Examples such as the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) provide lessons learned about the economic and operational value of efforts at Interoperability [

12].

The discussion is structured as follows:

Technological Foundations – Investigating semantic vs. syntactic Interoperability, HL7 FHIR, and AI-driven data harmonization [

8,

13].

Policy & Governance – Evaluating TEFCA, cross-border frameworks of regulation, and cross-border efforts at data-sharing [

6,

7,

9,

14].

Emerging Technologies – Assessing the potential of AI, blockchain, and machine learning to improve Interoperability [

10,

15,

16].

Case Studies – Review the VHA’s successful experience integrating the EHR with other real applications [

12].

Challenges & Recommendations – Overcoming the challenges of data security, confidentiality, and scalability while giving implementable solutions to policymakers and healthcare institutions [

6,

11,

17].

Table 2.

Global Adoption Rates of FHIR in Healthcare Systems. This table provides a comparative analysis of FHIR adoption across various healthcare settings and countries.

Table 2.

Global Adoption Rates of FHIR in Healthcare Systems. This table provides a comparative analysis of FHIR adoption across various healthcare settings and countries.

| Region/Country |

FHIR Adoption Rate |

Key Implementations |

Challenges |

Source |

| United States |

65% |

TEFCA integration, ONC mandates |

Legacy EHRs, high implementation costs |

[6,7] |

| European Union |

55% |

EU Digital Health Action Plan, cross-border EHR exchange |

Data privacy (GDPR), interoperability fragmentation |

[9,13] |

| Canada |

48% |

Pan-Canadian Health Data Strategy, FHIR-based national EHR |

Uneven provincial adoption |

[7,9] |

| Low/Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) |

22% |

WHO interoperability frameworks, donor-funded projects |

Infrastructure gaps, lack of regulatory enforcement |

[9,16] |

2. Literature Review

The literature on health information interoperability highlights its transformative impact on patient-centered care, operational efficiency, and healthcare coordination. However, significant gaps persist in standardization, policy alignment, security, and infrastructure [

21]. This section explores the technological foundations, policy and governance frameworks, and real-world applications of Interoperability, identifying key challenges and future research directions.

3.1. Technological Foundations of Interoperability

Syntactic vs. Semantic Interoperability

Interoperability consists of syntactic and semantic components that are both necessary to provide smooth information exchange:

Syntactic Interoperability: Assures that exchanging information is standard to allow systems to read and decode structured information. Tools like Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) and Health Level Seven (HL7) allow standard structuring of information between healthcare systems [

6].

Semantic Interoperability: Assures that information is meaningful between systems. Shared vocabularies like Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) and Logical Observation Identifiers, Names, and Codes (LOINC) provide shared terms that permit proper meaning to be understood between systems [

6].

Figure 1.

The relationship between syntactic and semantic interoperability, their applications, and their impact on consumer health.

Figure 1.

The relationship between syntactic and semantic interoperability, their applications, and their impact on consumer health.

Despite progress, complete semantic interoperability is still problematic. Numerous healthcare institutions are still supported by vendor-neutral data formats and existing systems that do not have the capabilities of structured data mapping [

5]. Amar et al. [

5] note that the problems are not solved by FHIR alone—semantic Interoperability needs a complete approach that incorporates standard terms, AI-enabled data harmonization, and machine learning algorithms to standardize the data.

While FHIR provides a technical standard to structure healthcare information exchange, this does not cover cross-domain semantic compatibility. ISO 23903:2021 accomplishes this by providing a reference architecture that enables harmonization of the various healthcare informatics standards (SNOMED CT, HL7, TEFCA) without repeatedly updating the interoperability specs [

22]. Similarly, the WHO Global Strategy on Digital Health (2020–2025) also emphasizes harmonization of international healthcare IT standards while enabling AI inclusion, digital surveillance of the real-time sort, and cybersecurity measures to provide smooth interoperability of healthcare networks at the international and national levels [

23].

3.2. FHIR Activities of Standardization

The Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) standard is key for organizing and sharing healthcare information. Developed by Health Level Seven International (HL7), the standard aims to increase Interoperability, facilitate real-time information exchange, and streamline clinical workflows. However, while FHIR offers significant advantages, its adoption remains inconsistent due to technical, financial, and implementation barriers.

Despite its strengths, adoption is inconsistent due to:

Technical Complexity: Legacy systems are still built upon HL7 v2 and CDA, and there is a need for further integration [

21].

Variable Adoption Levels: Large tech firms like Google and Microsoft are investing in FHIR, but smaller providers struggle due to costs and infrastructure constraints [

21].

To strengthen FHIR adoption, it must be complemented by AI-driven data harmonization and blockchain for secure, real-time data exchange.

3.2.1. Advantages of Using FHIR in Healthcare Interoperability

FHIR is designed to provide quick, secure, and scalable transfer of healthcare information. Its benefits include:

Modular API Structure – FHIR employs a RESTful API structure to allow healthcare applications to securely access and update patient information between systems.

Interoperability with Mobile Apps & Electronic Health Records – FHIR enables seamless interaction between mobile apps for healthcare, patient portals, and electronic health records (EHRs), enabling real-time information exchange [

7].

Standardized Data Formats – FHIR enables greater clinical workflow integration, usability, and healthcare provider decision-making by standardizing defined and coded data elements.

Improved Scalability and Adaptability – It is compatible with structured and unstructured information to support bespoke applications per the requirements of healthcare providers.

3.2.2. Barriers to FHIR Adoption

Despite its strengths, the adoption of FHIR is inconsistent with various financial and technical hurdles that constrain its broad deployment:

3.2.3. Complementary Strategies to Support FHIR Implementation

Ayaz et al. [

21] emphasizes that FHIR alone is not a universal solution. To maximize its effectiveness, FHIR should be complemented by additional governance and technological frameworks, including:

Regulatory Enforcement through TEFCA – Conforming FHIR to the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) would standardize the information exchange protocols between healthcare systems [

8].

Machine Learning to Standardise Data – Machine learning-enabled data harmonization software can enhance semantic Interoperability by automating non-standardized data into standard formats [

5].

Blockchain for Secure Data Sharing – Blockchain solutions can enhance the security of the data, auditability, and trust of the FHIR-enabled health data exchanges [

14].

3.3. Policy and Governance Within Interoperability

In addition to technological advancements, policy frameworks also play a key role in shaping interoperability strategies. Policy enforcement, international coordination, and regulatory compliance are needed for standard and secured healthcare information exchange among healthcare systems.

3.3.1. TEFCA and the Rulemaking Structure

The Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) is a U.S. government-led initiative to facilitate standardized, nationwide interoperability among healthcare organizations. TEFCA aims to:

Establish a Unified Platform of Data-Sharing – TEFCA establishes the infrastructure to provide smooth healthcare data exchange between clinics, insurers, government agencies, and hospitals.

Ensure Compliance with HIPAA and Other Laws – Following HIPAA, the 21st Century Cures Act, and other healthcare information privacy legislation, the TEFCA ensures that the transfer of electronic health information (EHI) is both secure and ethical [

4,

8].

Encourage Private-Public Collaboration – With the backing of the TEFCA, both public and private healthcare organizations can access a shared healthcare data exchange network to aid increased adoption of Interoperability.

Strengthening Practical Implementation Insights

The United States TEFCA and the EU Digital Health Action Plan are central to enabling cross-border Interoperability. However, international policy lacunae are present, as evidenced by regional regulatory fragmentation between the US, the EU, and the LMICs. These disparities are hindrances to the scalability of Interoperability.

Real-world comparison: VHA succeeded with its complete EHR system, while the LMICs lack digital infrastructure and regulation enforcement [

9].

Global Interoperability Initiative

Global initiatives, such as the EU Digital Health Action Plan and the WHO's Interoperability strategy, aim to standardize the transmission of health information [

9]. However, challenges are the fragmentation of the regulatory environment and infrastructure inequities between low-resource settings [

9,

13].

Policy alignment: HIPAA, GDPR, and the WHO must harmonize for smooth information exchange [

9,

13].

Comparison of Global Policies

A detailed comparison of the US, EU, and Canadian regulatory frameworks underscores standardization deficiencies, data protection legislation, and cross-border exchange regimes with specific challenges within the LMICs [

5,

6,

9]. The comparison offers insightful information regarding harmonizing the frameworks to support international Interoperability.

Challenges in TEFCA Adoption

Despite its potential, the uptake of the TEFCA has lagged due to

Addressing these challenges will require more significant enforcement efforts, financial incentives, mandates by regulation, and government-backed financing schemes to accelerate the adoption of TEFCA into healthcare settings.

Table 3.

Comparison of Interoperability Policies (U.S., EU, Canada, LMICs). This table compares

regulatory frameworks across different regions, highlighting gaps and alignment efforts.

Table 3.

Comparison of Interoperability Policies (U.S., EU, Canada, LMICs). This table compares

regulatory frameworks across different regions, highlighting gaps and alignment efforts.

| Policy Framework |

United States (TEFCA, HIPAA) |

European Union (GDPR, EHDS) |

Canada (Pan-Canadian Strategy) |

LMICs (WHO-led initiatives) |

| Standardization Approach |

TEFCA mandates national EHR integration |

GDPR-compliant cross-border data exchange |

Province-led, limited national mandate |

WHO global standards, inconsistent adoption |

| Data Privacy Regulation |

HIPAA ensures PHI security |

GDPR enforces strong patient consent |

Provincial privacy laws |

Varies widely, often weak security |

| Challenges |

Limited enforcement, voluntary compliance |

Fragmentation among member states |

Uneven adoption across provinces |

Infrastructure constraints, lack of funding |

3.3.2. Global Interoperability Efforts

Interoperability challenges extend beyond national borders, requiring global policy coordination to facilitate cross-border health data exchange. Several international initiatives aim to standardize EHR frameworks and enhance Interoperability on a global scale:

European Union’s Digital Health Action Plan – It aims to harmonize the models of the EHR at the EU member state levels to allow cross-border healthcare service delivery and the exchange of patient information [

7].

World Health Organization (WHO) Interoperability Framework – The WHO established international guidelines to standardize the requirements of Interoperability to provide equal access to low-resource countries to the technologies of shared healthcare information [

9].

ISO/TC 215 Health Informatics Standards – The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) established technical requirements to promote greater Interoperability, protection of personal information, and the security of healthcare information within multi-national healthcare environments [

7,

9].

Challenges in Global Interoperability Implementation

Despite progress made toward international standardization, significant challenges remain:

Regulatory Fragmentation – Countries have unique data protection legislation and compliance models, with international compatibility a problem.

Infrastructure Disparities – Low-income regions often lack the technological infrastructure to implement FHIR-compatible systems, creating a digital divide in health data exchange.

Data Privacy and Cybersecurity Risks – Cross-border data transfer creates complex cybersecurity threats that necessitate strong governance frameworks to protect the information.

Strategies to improve international Interoperability

To address all of them, the following strategies need to be pursued

Regulatory Harmonization – Governments must harmonize the data privacy legislation (e.g., HIPAA, GDPR, and country-wide healthcare policies) to allow secure international data exchange.

Investment in digital infrastructure – Scaling up international opportunities to fund low-resource healthcare systems can bridge the digital divide while boosting the Interoperability of international health information.

Privacy-Preserving Technologies – With AI-driven anonymization techniques and zero-knowledge proofs, confidential patient information can be maintained while enabling cross-border compatibility.

The widespread implementation of FHIR and TEFCA, together with international frameworks of Interoperability, is imperative to the smooth, secure, and harmonized exchange of healthcare information. However, technical challenges, cost impediments, and regulatory hurdles remain to impede full-scale implementation.

AI-driven data harmonization tools, blockchain security models, and stronger regulatory mandates must complement FHIR adoption.

TEFCA implementation requires enhanced policy enforcement, including mandatory compliance, financial incentives, and public-private collaboration.

Global interoperability efforts must prioritize harmonizing the regulatory environment, investments in digital infrastructure, and adopting privacy-preserving technologies.

By addressing them, the healthcare sector can move towards a fully connected, patient-centric interoperability environment that maximizes clinical decision-making, operational effectiveness, and healthcare outcomes worldwide [

7,

9].

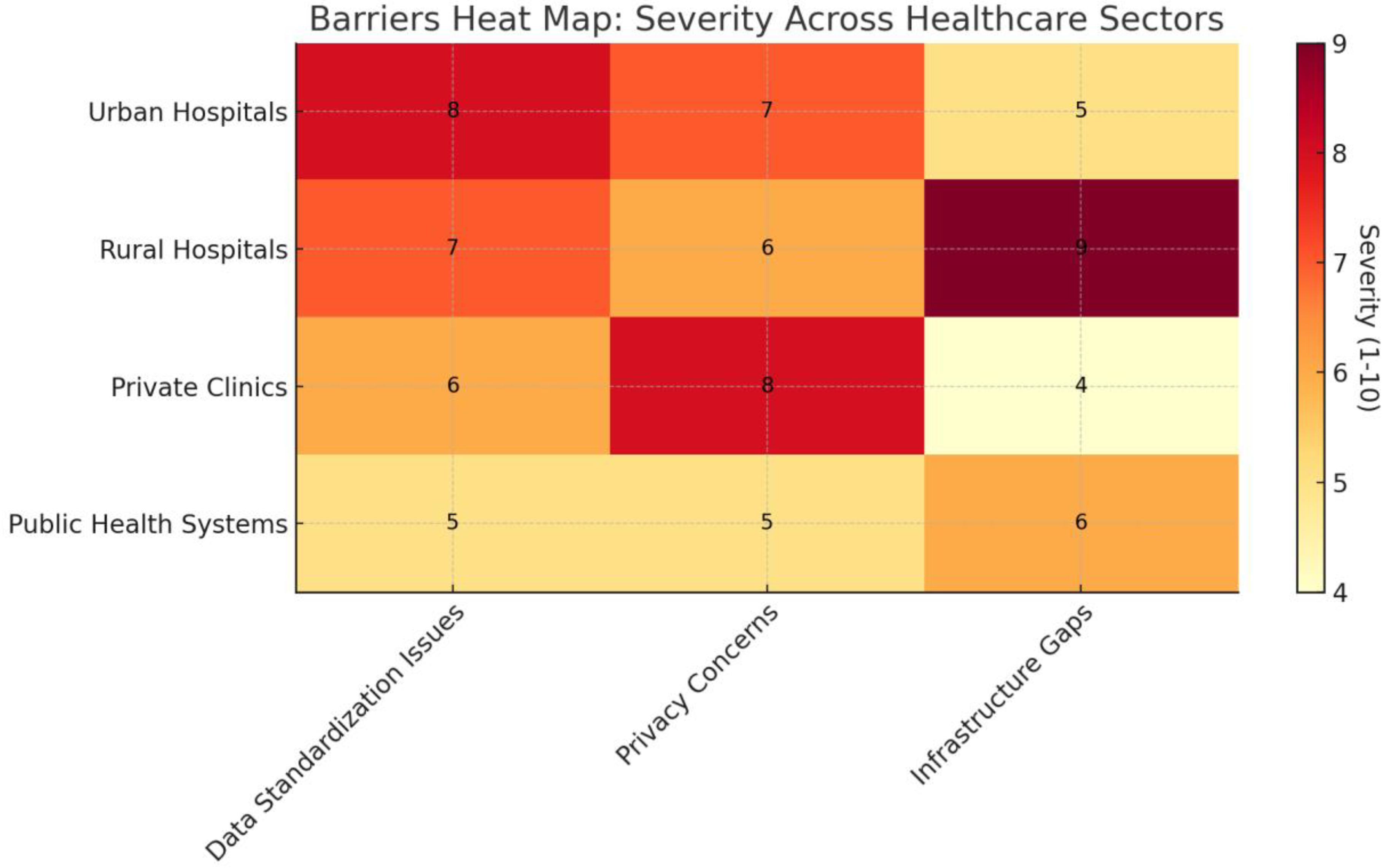

Figure 2.

A heatmap illustrating the severity of interoperability barriers, including data standardization issues, privacy concerns, and infrastructure gaps across different healthcare sectors.

Figure 2.

A heatmap illustrating the severity of interoperability barriers, including data standardization issues, privacy concerns, and infrastructure gaps across different healthcare sectors.

Despite significant strides made toward standardization of healthcare information, several challenges persist that are impeding the full implementation of Interoperability at a nationwide and international scale:

Harmonizing National Laws – Different countries and jurisdictions have unique sets of legislation, such as HIPAA of the US and GDPR of the European Union, that have divergent healthcare information exchange policy frameworks.

Ensuring Data Privacy – The secure transfer of confidential patient information between healthcare networks is a persistent issue, particularly with cross-border interoperability efforts. It is imperative to find a balance between the accessibility of the information and the protection of the information.

Overcoming Infrastructure Inequalities – In low-resource settings, the digital infrastructure to accommodate FHIR-enabled interoperability solutions is not usually present. It creates inequitable access to technologies that allow the exchange of health information, particularly among low-income communities [

21].

Addressing these challenges will require a collaborative effort by policymakers, healthcare institutions, and technology providers to harmonize the regulations, invest in digital infrastructure, and strengthen data protection frameworks.

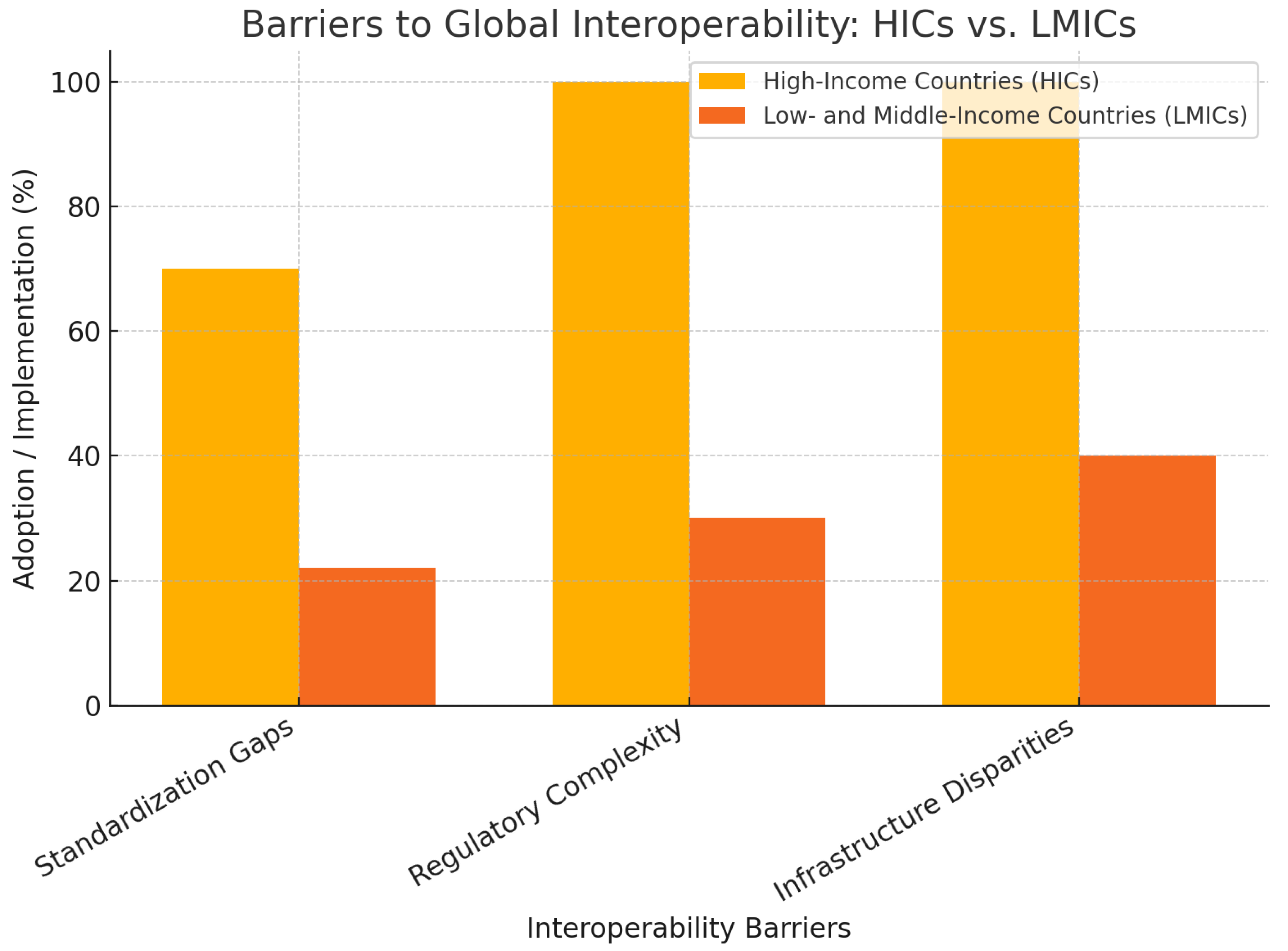

Figure 3.

The bar chart compares major interoperability barriers between high-income countries (HICs) and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Figure 3.

The bar chart compares major interoperability barriers between high-income countries (HICs) and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

3.4. Real-World Case Study: Veterans Health Administration (VHA)

3.4.1. VHA’s Success with Integrated EHR

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is a classic example of the successful deployment of Interoperability. With the rank of being among the US’s largest healthcare systems that are fully integrated, the VHA’s electronic health record (EHR) system facilitates smooth information transfer between more than 1,200 healthcare centers. The key benefits of this system include:

Improved Care Coordination – Multiple care providers at various sites of the VHA can access, update, and share patient health information in real time to improve care coordination.

Reduction in Redundant Tests and Medication Errors – Interoperability within the environment of the VHA avoids unnecessary tests, reduces error rates, and ultimately saves healthcare spending [

10].

Enhanced Provider Decision-Making – With the central health information exchange, clinicians can access complete patient histories to support more accurate treatment decisions and personalized treatment plans.

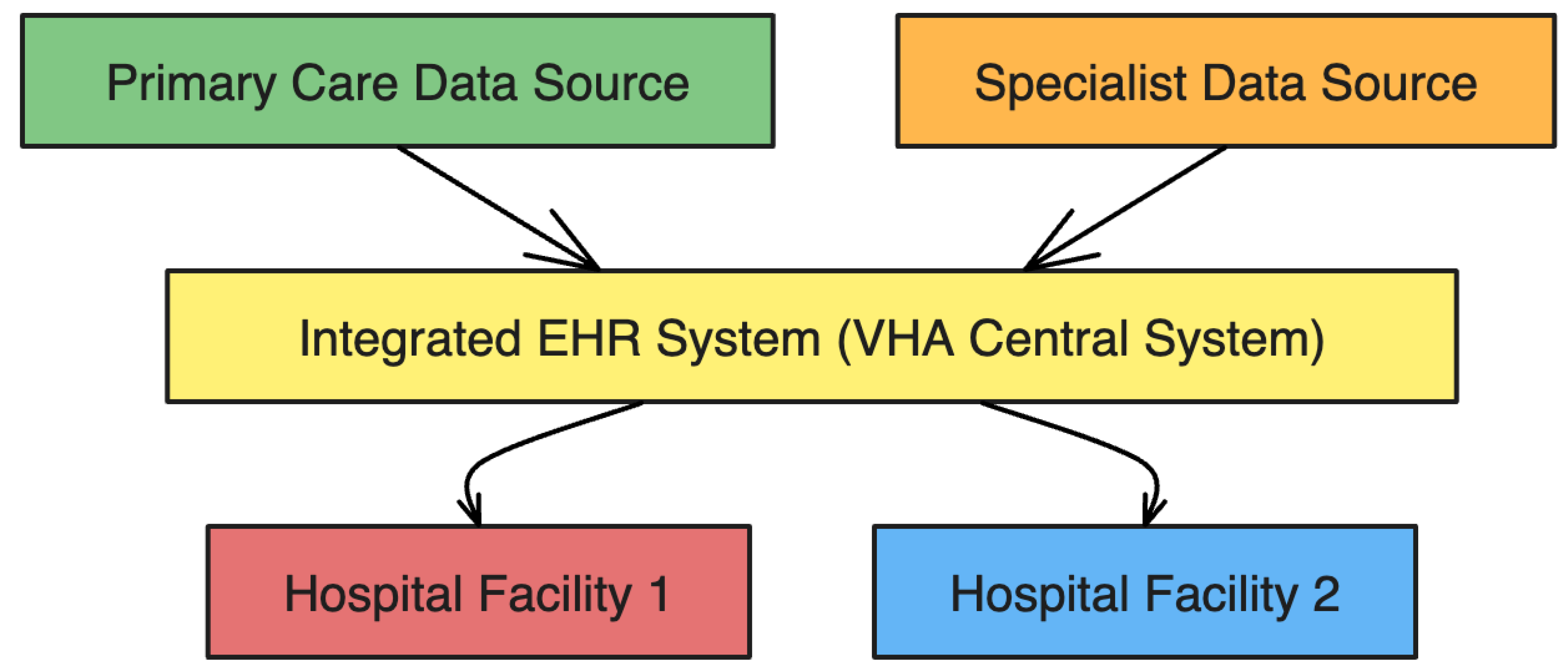

Figure 4.

illustrates the VHA’s integrated EHR system, demonstrating how data flows from primary care and specialist sources to different hospital facilities, ensuring efficient and secure patient information exchange.

Figure 4.

illustrates the VHA’s integrated EHR system, demonstrating how data flows from primary care and specialist sources to different hospital facilities, ensuring efficient and secure patient information exchange.

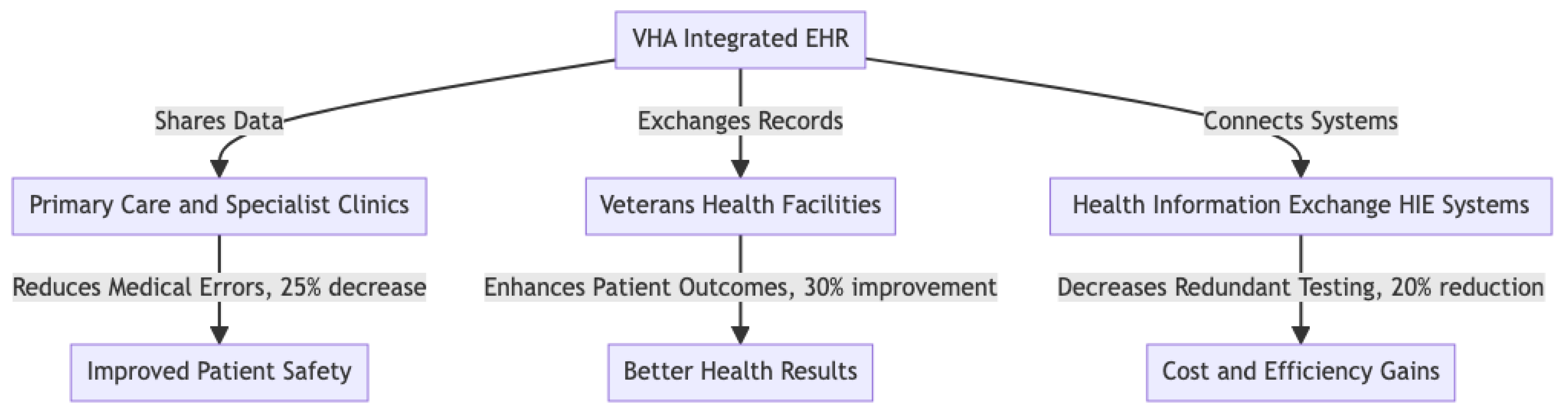

Figure 5.

VHA Integrated EHR Success Story and Key Metrics.

Figure 5.

VHA Integrated EHR Success Story and Key Metrics.

Despite the overall success of the VHA’s shared EHR solution, challenges remain to integrate existing systems and standardize information formats across care sites. Many older health IT infrastructures within VHA facilities require significant modifications to achieve full FHIR compatibility and to optimize health information exchange (HIE) interfaces [

10].

To address the challenges of this kind, current efforts at the VHA target:

Accelerating FHIR adoption to enhance data interoperability across VHA facilities.

Improving HIE Tools to support information exchange with external healthcare providers

Optimizing system usability to reduce workflow inefficiencies caused by data integration limitations.

3.4.2. Medication Reconciliation and Health Information Exchange (HIE) at the VHA

Medication reconciliation is critical in interoperability, ensuring that medication histories are consistently updated and accessible across healthcare providers. A qualitative analysis of HIE adoption at the VHA identified both successes and ongoing challenges:

Improved Clinician Access to External Medication Records – HIE adoption has led to fewer discrepancies in prescription histories, reducing medication errors and enhancing patient safety [

11].

Challenges in Interface Usability – Data glut, navigation intricacy, and impediments to integrating systems are among the challenges that impede clinicians' optimal usage of HIE solutions.

Opportunities for Maximizing HIE Tools – Improved workflow architecture and real-time support of decisions can potentially simplify access to the data and enhance the results of Interoperability.

These findings support the need to continuously improve the HIE systems' design to enable healthcare providers to access, interpret, and implement patient information appropriately [

11].

3.5. Identified Gaps and Future Directions

While substantial progress has been made in healthcare interoperability, several critical gaps remain that require further research and policy intervention:

Standardization Challenges – FHIR and HL7 have standard frameworks of structure that provide a way of being compatible with others while still being compatible with existing systems [

6,

7,

21].

Security and Privacy Concerns – Regulatory efforts such as TEFCA aim to enhance health data security, yet privacy concerns persist, particularly in cross-border data exchange scenarios [

4,

8,

9].

Infrastructure Inequities – Many of the resource-limited areas lack the digital infrastructure to support the efforts of Interoperability, requiring certain investments and scalable solutions [

7,

9,

21].

Integration of New Technologies – While blockchain and AI can potentially deliver solutions to the problem of secured information exchange and automation, their practical implementation is held back by cost, complexity, and scalability [

10,

11].

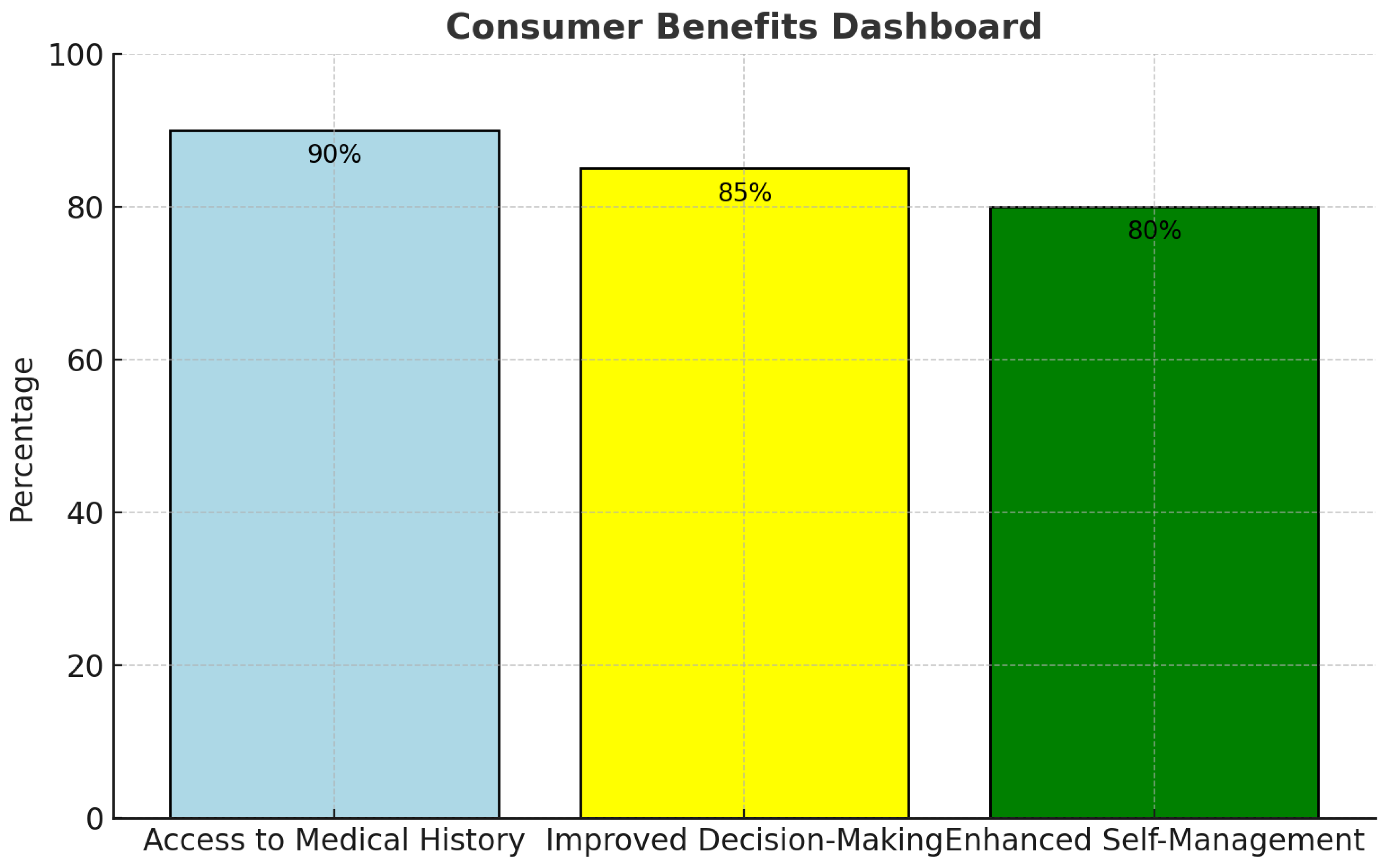

Figure 6.

illustrates the consumer benefits of interoperability, highlighting medical history access, decision-making, and self-management improvements. These insights reinforce the need for sustained efforts in policy, technology, and infrastructure investment to enhance the effectiveness and accessibility of healthcare interoperability.

Figure 6.

illustrates the consumer benefits of interoperability, highlighting medical history access, decision-making, and self-management improvements. These insights reinforce the need for sustained efforts in policy, technology, and infrastructure investment to enhance the effectiveness and accessibility of healthcare interoperability.

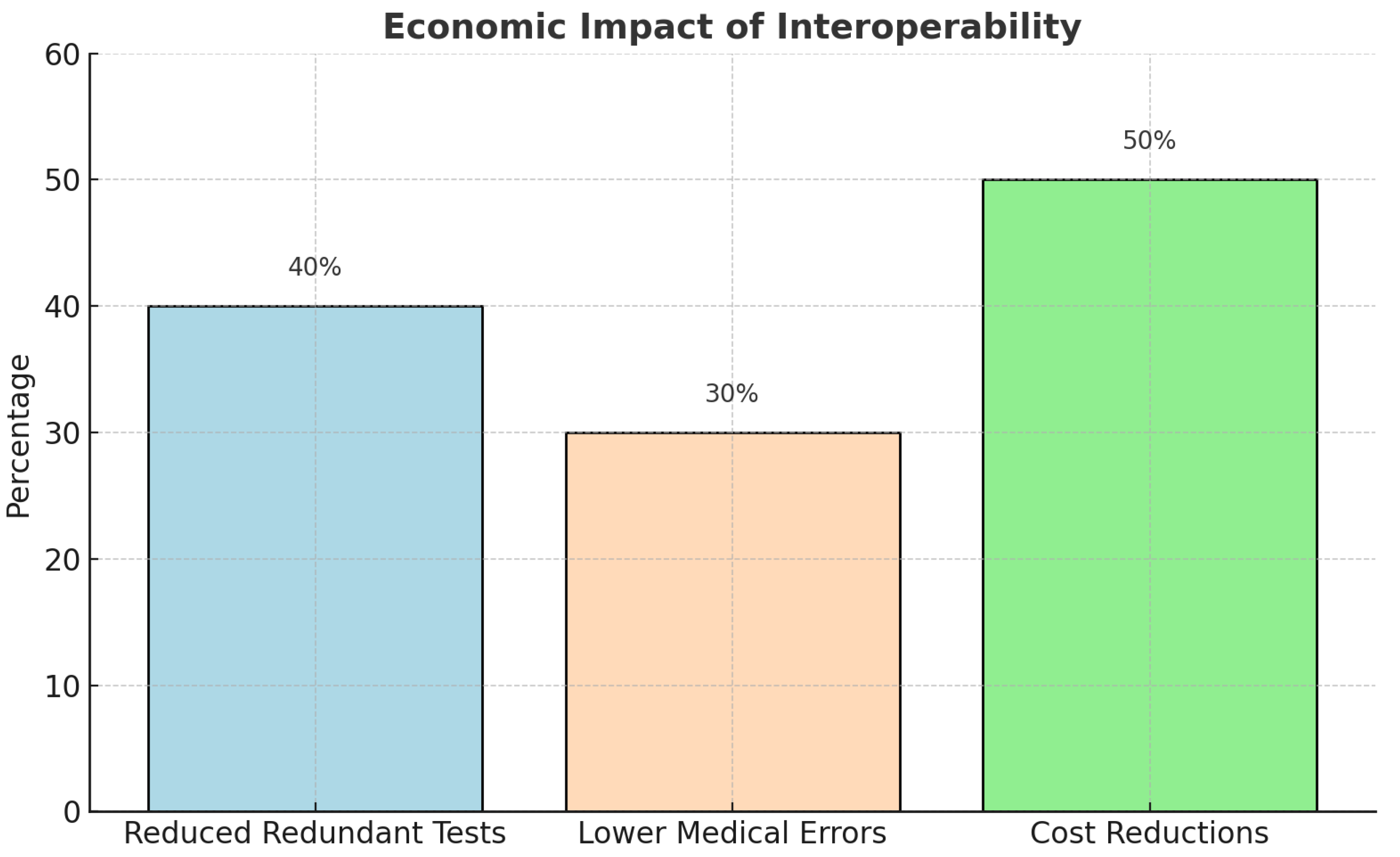

Figure 7.

The economic benefits of interoperability, including reduced redundant tests, lower medical errors, and cost reductions.

Figure 7.

The economic benefits of interoperability, including reduced redundant tests, lower medical errors, and cost reductions.

Future research must consider evaluating AI and blockchain integration into interoperability frameworks and the creation of scalable governance models that harmonize the accessibility of the data with security needs and ethics.

4. Challenges & Future Directions: Strengthening Policy and Technological Frameworks

Despite advancements made to this point toward increased Interoperability, significant areas of standardization, security, privacy, and infrastructure equity are still to be addressed. Overcoming them will require a purposeful approach that integrates policy enforcement with emerging technologies and targeted investments. Below are the key impediments to Interoperability, which are addressed with specific recommendations to improve adoption and effectiveness within healthcare systems.

4.1. Overcoming Standardization Gaps

Challenges:

One of the significant challenges to healthcare information interoperability is the fragmented adoption of global data standards. Many healthcare organizations continue to rely on legacy systems that are not compatible with the Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR), the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine – Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT), the Logical Observation Identifiers, Names, and Codes (LOINC), and the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA). Furthermore, while syntactic Interoperability— ensuring data follows a standardized format—has been widely implemented, semantic interoperability remains insufficiently addressed. Data representation variability and the holding on to the proprietorial formats of the data inhibit the meaningful exchange of the data between institutions. Inconsistent enforcement of the interoperability regulation also causes variability in the levels of compliance among healthcare institutions.

Recommendations:

A global standard approach is imperative to provide end-to-end Interoperability between healthcare systems. Governments and regulatory agencies should impose FHIR, SNOMED CT, and TEFCA international health data standard requirements through policy mandates, financial incentives, and phased implementation roadmaps [

12,

13]. Incorporating artificial intelligence (AI) into data standardization can enhance semantic interoperability by streamlining the data mapping process between healthcare information systems [

5]. Additionally, adopting real-time terminology services that convert non-standardized data into universally recognized vocabularies would reduce inconsistencies and enhance interoperability across electronic health records (EHRs). International coordination between international standard-setting institutions like the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), and the European Union’s Digital Health Action Plan must aim at harmonizing the interoperability requirements to allow the cross-border exchange of information to be both secured and harmonious [

9].

4.2. Enhancing Security and Privacy Within Interoperability Networks

Challenges:

Cybersecurity risks become more pronounced as health data exchange increases across multiple platforms. Interoperability increases the attack vector of data breaches, ransomware threats, and access to patient information without proper clearance. Trust is a significant impediment to adopting Interoperability due to the apprehension of healthcare providers and patients about protecting shared information. Furthermore, existing health information exchanges (HIEs) lack advanced fraud detection mechanisms, making them vulnerable to identity theft, fraudulent billing practices, and data manipulation.

Recommendations:

Integrating blockchain technology into healthcare data exchange systems can significantly enhance the systems' security by providing the systems with tamper-proof, immutable records that deliver the integrity of the data and transparency [

14]. Access can also be regulated by smart contracts to permit access to the information to occur on pre-approved terms. AI-driven fraud detection systems can also improve the systems' security by identifying abnormalities within the healthcare data exchange to deliver real-time protection against potential breaches [

5]. Zero-trust security models with multi-factor authentication (MFA) and role-based access control (RBAC) must also be introduced to block unwanted access to healthcare-sensitive information. Compliance with the GDPR and HIPAA requirements will also improve the protection of the information to protect the cross-border and national data exchange [

8].

4.3. Bridging Infrastructure Disparities and Expanding Interoperability in Underserved Regions

Challenges:

Healthcare facilities in rural and underserved areas often lack the necessary technological infrastructure and financial resources to implement interoperable systems. The costs associated with EHR integration, software upgrades, and data migration create additional barriers for smaller healthcare providers. Furthermore, disparities in health IT capabilities between large urban hospitals and resource-constrained healthcare facilities contribute to unequal access to interoperability solutions.

Recommendations:

Increasing government and private investments in the interoperability infrastructure is necessary to bridge the digital divide within healthcare [

15,

16]. International health funds and government grants need to prioritize increasing the capabilities of Interoperability within low-resource environments. Developing cloud-based health data exchange models through public-private partnerships (PPPs) can also reduce infrastructure costs, making interoperability solutions more accessible to small and mid-sized healthcare providers [

17,

18]. Open-source interoperability platforms should also be developed to ensure low-cost, scalable solutions for institutions with limited financial resources. Aside from this, increased mobile access to the Electronic Health Record (EHR) can enhance the capabilities of telemedicine service delivery and remote healthcare delivery, where the presence of the internet and on-site infrastructure is still limited.

4.4. Future Priorities of Research and Development

Future research must aim to enhance AI and blockchain technologies to enhance interoperable healthcare systems' scalability, security, and effectiveness. Analyzing AI-powered models of harmonization can unveil novel insights into automated standardization approaches that avoid human error in processing the data manually. Future research into blockchain governance models is also needed to build trust frameworks to support the secure exchange of healthcare data. Cross-border interoperability research must also examine the regulatory and technical hurdles of international healthcare data exchange to harmonize the regulation of personal information and adhere to international security protocols. The uptake of federated learning techniques—that permit the training of machine learning models on distributed healthcare information without the need to exchange the information directly—must also be researched to improve the applications of AI that preserve confidentiality within healthcare.

A significant challenge in the exchange of health information is the fragmentation of the interoperability standard. Many national health systems operate under different governance models, regulatory requirements, and technical infrastructures, leading to inconsistent data-sharing frameworks [

6,

7]. ISO 23903:2021 offers a well-formulated solution by providing a reference architecture of interoperability that harmonizes the semantic, technical, and operational levels of interoperability [

22]. It is also aligned with the WHO’s Global Strategy on Digital Health (2020–2025), which promotes a harmonized regulative approach that incorporates the usage of FHIR, GDPR, TEFCA, and the standard of the country’s healthcare IT [

23]. The WHO’s Report on the European Digital Transformation also stresses the need to strengthen international partnerships to fill the regulative and technological divide of cross-border interoperability [

24].

The challenges to healthcare interoperability necessitate a combination of policy enforcement, technological innovation, and infrastructure investments. Standardization is a major hurdle that will necessitate international harmonization of the policy and AI-driven semantic mapping technologies. Blockchain technologies and AI-driven anti-fraud systems can address safety threats, while infrastructure inequities must be addressed by targeted investments of finances and scalable, cost-effective models of Interoperability. Future research must also seek the newest technologies to improve the efficiency, security, and accessibility of interoperable healthcare information systems. Overcoming the challenges will be key to achieving a fully connected, patient-driven healthcare ecosystem that enables smooth information exchange, improved clinical decision-making, and global healthcare outcomes.

5. Emerging Technologies to Ensure Interoperability

The evolution of artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and standardized interoperability frameworks such as FHIR and TEFCA is transforming the healthcare industry by tackling data security, semantic interoperability, and predictive analytics challenges. These technologies enhance patient-centered care by enabling real-time, secure, and standardized health data exchange, paving the way for more efficient and scalable digital healthcare ecosystems [

5,

7,

15]. This section examines blockchain, AI, and the future trajectory of FHIR and TEFCA in global interoperability efforts.

5.1. Blockchain for Secure and Transparent Health Data Exchange

Blockchain technology offers a decentralized, immutable, and secure platform for health data exchange. This ensures tamper-proof audit trails, improved patient data ownership, and cross-border interoperability [

5,

14]. Unlike centralized databases, blockchain reduces data silos and cybersecurity risks, making it a promising solution for secure and efficient health information exchange [

14,

19].

Key Applications of Healthcare Interoperability

-

Patient-Controlled Data Ownership & Consent

- o

Smart contracts allow the patient to grant access to their medical record with transparent and consent-driven Interoperability [

14,

19].

-

Cross-System Data Consistency & Avoidance of Fraud

- o

Blockchain prevents illegal amendments to information and ensures information consistency between independent healthcare networks to improve the trustworthiness and reliability of multi-stakeholder systems [

5,

14].

-

Cybersecurity & Ransomware Protection

- o

Blockchain-based solutions improve cybersecurity protection by providing a secure, immutable ledger that minimizes the threats of data breaches and ransomware [

14,

19].

Challenges & Future Considerations

Despite its advantages, blockchain adoption in healthcare faces key barriers, including:

Scalability Constraints: The computational cost of blockchain can limit real-time processing speed, especially with large healthcare systems [

5,

14].

Regulatory & Compliance Issues: HIPAA, GDPR, and national security frameworks necessitate transparent governance models to deliver a compliant state [

14,

19].

Integration with Older Systems: Traditional EHR systems of the existing hospitals could pose a problem to blockchain integration without standard frameworks of Interoperability [

5,

14].

5.2. AI for Data Standardization and Predictive Analytics

AI-driven solutions are central to automating data standardization, increased interoperability, and clinical decision-making support [

5,

20]. AI bridges healthcare data gaps with the aid of machine learning (ML) and natural language processing (NLP), enabling the support of predictive analytics to aid proactive care of the patient [

5,

6,

20]. AI facilitates increased semantic Interoperability by standardizing data with process automation, filling healthcare data gaps. The main applications are NLP support for adopting FHIR and predictive analytics support for population health management [

5,

20].

Stakeholder engagement: All the major participants involved—including the healthcare providers, the patients, the policymakers, and the technologies' developers—will need to collaborate to craft AI solutions that address the ethics of the issue at hand, such as the issue of the algorithms being prejudiced and the issue of confidentiality of the information [

5].

Key Applications of AI-Driven Interoperability

-

Natural Language Processing (NLP) to Enable Semantic Interoperability

- o

AI-powered NLP models translate unstructured clinical narratives into standard FHIR-compliant formats to provide smooth cross-system interpretation of the data [

5,

20].

-

Predictive Analytics to Manage Populations

- o

AI enhances personalized treatment planning, earlier disease detection, and risk stratification to enhance individual and population health [

5,

20].

-

Automated Data Mapping & FHIR Integration

- o

AI-driven automated data transformation models improve FHIR adoption, facilitating Interoperability between legacy and modern health IT systems [

5,

6].

Challenges & Ethical Issues

While AI accelerates semantic Interoperability and predictive analytics, several challenges require attention:

Bias & Ethics Issues: AI systems can learn biases embedded within training sets to reinforce inequities in healthcare delivery [

5,

20].

Regulatory Oversight & Compliance: Clinical decision support systems driven by AI must align with international healthcare information protection legislation to support the proper usage of AI [

5,

6].

Data Security & Privacy Risks: Reliance on large patient datasets generates confidentiality issues that necessitate robust encryption and governance of the data [

5,

6,

20].

Table 4.

Emerging Technologies and Their Contributions to Interoperability. This table outlines the role of AI, blockchain, and FHIR in healthcare interoperability.

Table 4.

Emerging Technologies and Their Contributions to Interoperability. This table outlines the role of AI, blockchain, and FHIR in healthcare interoperability.

| Technology |

Key Benefits |

Challenges & Barriers |

| AI & NLP |

Improves semantic interoperability, automates data mapping |

Bias in AI models, regulatory concerns |

| Blockchain |

Enhances security, ensures patient-controlled consent |

Scalability, lack of widespread implementation |

| FHIR & TEFCA |

Enables real-time, standardized data exchange |

Adoption barriers, costs of EHR integration |

5.3. FHIR and TEFCA: Future Directions in Data Sharing

The Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) standard and the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) both provide structured nationwide and international models of healthcare information exchange [

6,

15]. Both models are directed toward real-time Interoperability, alignment with regulation, and secured federated models of exchange [

4,

13].

Key Developments of FHIR and TEFCA

-

1.

-

FHIR Advancements in Standardized Data Sharing

- o

Expanding FHIR-based APIs enables seamless real-time information exchange between wearables, personal health apps, and EHRs to improve patient-oriented Interoperability [

6,

15].

-

2.

-

TEFCA’s Role within the Governance & Compliance

- o

TEFCA provides a federated governance model for health data exchange, ensuring compliance with HIPAA, GDPR, and national security policies [

4,

13].

-

3.

-

Global Harmonization of Interoperability Standards

- o

Integrating FHIR-based models of the TEFCA into international frameworks like the WHO Interoperability Framework and the EU Plan on Digital Health enables cross-border standardization of the information [

7,

23,

24].

Future Research & Implementation Priorities:

To fully leverage FHIR and TEFCA, future research should focus on:

-

Aligning AI & Blockchain with FHIR-Based TEFCA Models

- o

Integrating AI-driven harmonization of information with blockchain-enabled protection to improve real-time compliance with privacy information exchange [

5,

14].

-

Developing Scalable Interoperability Solutions for the Resource-Limited

- o

Investing in public-private partnerships to support the adoption of FHIR and TEFCA by low-resource healthcare systems [

4,

6].

-

Enhancing Cybersecurity & Data Privacy Governance

- o

Strengthening data encryption, identity authentication, and distributed patient data management within the frameworks of FHIR [

4,

13].

Key Contributions of Emerging Technologies to Interoperability

The successful integration of AI, blockchain, and FHIR-based interoperability frameworks will transform healthcare data exchange, ensuring scalable, privacy-compliant, and real-time interoperability. However, technical, ethical, and regulatory barriers must be addressed to maximize the potential of these emerging technologies in the healthcare sector. Future interoperability frameworks should rely on FHIR-based data structuring and incorporate ISO 23903:2021 to address cross-domain integration challenges. As FHIR and TEFCA evolve, the ISO 23903:2021 model can serve as a harmonization layer, ensuring semantic alignment across regional and global interoperability initiatives [

22]. The WHO Global Strategy on Digital Health (2020–2025) also emphasizes the need for AI-driven governance models, blockchain-enabled patient consent management, and predictive analytics to enhance real-time health data exchange and decision-making [

23]. The WHO European Digital Health Report further advocates for capacity-building programs, focusing on telemedicine, digital literacy, and AI regulatory frameworks to drive future cross-border interoperability efforts [

24].

6. Policy and Governance Approaches

Achieving seamless healthcare data interoperability requires strong policymaking, international coordination, and regulatory frameworks. Governments, healthcare institutions, and regulatory agencies have a key responsibility to implement standard protocols of data-sharing, to impose compliance with international requirements, and to provide equal access to the means of Interoperability. In this section, the current policymaker environment is assessed, international efforts toward Interoperability are addressed, and the major policymaker and healthcare institution recommendations are made.

6.1. Regulatory Frameworks Supporting Interoperability

Governments and healthcare regulatory agencies globally have established policy and compliance frameworks to provide secured, scalable, and standard Interoperability [

4,

16,

17]. The frameworks provide data privacy frameworks, incentives to promote Interoperability, and ethics models to inform health data exchange.

Key Regulatory Frameworks and Their Impact:

-

1.

-

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

- o

HIPAA (United States): Ensures data privacy, security, and controlled exchange of protected health information (PHI) [

4].

- o

GDPR (European Union): Creates patient consent requirements and data portability provisions compatible with international interoperability efforts [

16].

-

2.

-

HITECH Act & TEFCA (United States)

- o

HITECH Act: Encourages the adoption of electronic health records (EHR) and enables the adoption of FHIR-based interoperability standards [

17].

- o

-

Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA):

-

3.

-

Medicare & Value-Based Care Policies

- o

Medicare reimbursement models are increasingly connected to Interoperability performance [

16].

- o

Value-based care models support information-sharing between healthcare providers to improve the quality of care and prevent unnecessary procedures [

17].

Challenges in Regulatory Adoption:

Inconsistent enforcement of the TEFCA policies among healthcare institutions [

4,

18].

Fragmentation between international, US, and EU legislation necessitates policy harmonization [

9,

13].

Data-sharing incentives are minimal, creating challenges for small-and medium-sized providers [

16].

6.2. Global Interoperability Initiatives

Interoperability is a global priority, with governments and international organizations working to create cross-border health data-sharing frameworks. These initiatives focus on standardization, regulatory alignment, and data privacy compliance.

The ISO 23903:2021 standard also prescribes a normative reference model of interoperability that transcends the exchange of mere data to knowledge-sharing systems. Compared to strictly technical requirements like the FHIR standard, the ISO 23903:2021 standard enables cross-domain coordination with semantic harmonization without constantly updating existing health IT systems [

22]. The 2020–2025 WHO’s Global Strategy on Digital Health also reinforces this imperative by encouraging strong governance models, interoperability frameworks, and AI-driven decision-making to deliver universal, equitable access to digital solutions to healthcare [

23]. Similarly, the WHO European Region Report on the Digital Transformation of Health also reinforces practical implementation innovations of digital health strategies with a perspective of the roles of regulatory frameworks, AI ethics, and cybersecurity within cross-border interoperability [

24].

Major International Interoperability Initiatives:

-

1.

-

European Union Digital Health Plan of Action

- o

Supports FHIR-based cross-border transfer of EHR among the EU nations [

7].

- o

It aims to build a pan-European interoperability infrastructure to improve access to healthcare and patient mobility [

7].

- o

Promotes compliance with GDPR and AI governance frameworks [

7].

-

2.

-

World Health Organization (WHO) Global Interoperability Strategy

- o

Develop universal standards to exchange health information to improve international compatibility [

24].

- o

It focuses on standardization of electronic health records [

23,

24].

-

3.

-

ISO/TC 215 Health Informatics Standards

- o

Advance semantic and syntactical interoperability standards to support international health data exchange [

22].

- o

Aligns with SNOMED CT, FHIR, and HL7 to promote cross-system consistency of the data [

6,

15].

Challenges in Global Interoperability

- o

Regulatory fragmentation within the national policies postpones cross-border implementation [

7,

13,

23].

- o

Infrastructure disparities between low-resource settings generate interoperability gaps [

15,

16].

- o

Variability in blockchain governance must be harmonized with AI [

5,

14,

19].

Table 5.

Comparison of Key Interoperability Standards and Governance Models.

Table 5.

Comparison of Key Interoperability Standards and Governance Models.

| Standard/Framework |

Focus Area |

Key Contribution to Interoperability |

Challenges |

| FHIR (HL7) |

Technical data exchange |

Defines API-based modular health data sharing |

Limited semantic interoperability |

| TEFCA (ONC, USA) |

Policy & Governance |

Creates a federated framework for EHR data exchange |

Voluntary adoption slows implementation |

| ISO 23903:2021 |

Semantic interoperability |

Provides an ontology-driven model for integrating multiple standards (FHIR, SNOMED CT, HL7) |

Limited awareness and adoption |

| WHO Global Strategy on Digital Health (2020–2025) |

International interoperability |

Establishes governance models for cross-border health data exchange, AI adoption, and cybersecurity frameworks |

Bridging the digital divide in LMICs |

| WHO European Digital Health Action Plan |

Regional policy and implementation |

Drives telemedicine expansion, AI ethics, and regulatory harmonization in the European Region |

Requires further scalability beyond Europe |

Table 6.

Key Stakeholders and Their Roles in Interoperability Adoption. This table summarizes the stakeholders involved in health interoperability and their key roles.

Table 6.

Key Stakeholders and Their Roles in Interoperability Adoption. This table summarizes the stakeholders involved in health interoperability and their key roles.

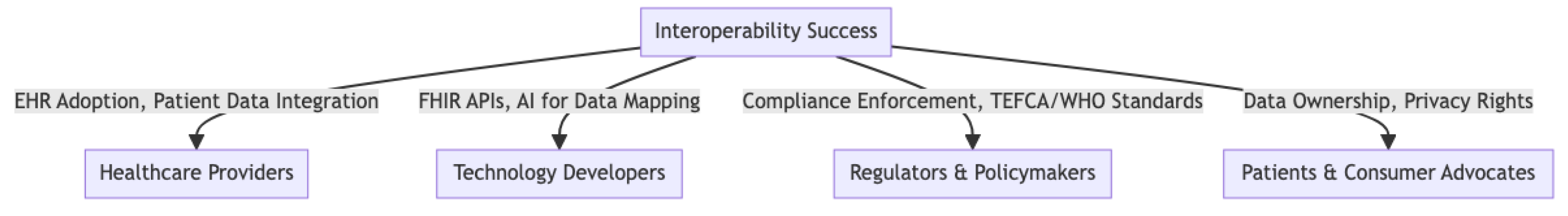

| Stakeholder Group |

Key Role in Interoperability |

Challenges |

| Healthcare Providers |

Ensure seamless data exchange between institutions |

EHR system fragmentation, lack of training |

| Technology Developers |

Develop FHIR-compliant APIs, AI-driven data harmonization tools |

Integration with legacy systems, security risks |

| Regulators & Policymakers |

Enforce compliance (HIPAA, GDPR, TEFCA) |

Cross-border policy misalignment |

| Patients & Consumer Groups |

Advocate for patient data ownership and privacy |

Lack of awareness, concerns about security |

6.3. Recommendations for Policymakers and Healthcare Institutions

To address the challenges of interoperability governance, healthcare institutions must harmonize their efforts at the regulative scale, invest in blockchain and AI surveillance, and ensure equal access to healthcare IT solutions.

Policy & Governance Recommendations:

-

1.

-

Align with the International Health Data Framework

- o

Establish interoperability governance models integrating FHIR, ISO, WHO, and GDPR standards [

4,

9,

13].

- o

Encourage data-sharing mandates of compliance among healthcare providers embracing TEFCA and international frameworks of Interoperability [

4,

9].

- o

Develop cross-border regulatory agreements to streamline EHR exchange and patient data accessibility [

9,

13].

-

2.

-

Implement AI and blockchain Regulations to Ensure Interoperability

- o

Establish ethics-driven governance models to oversee AI-powered clinical decision support systems [

5,

14].

- o

Develop compliance frameworks to promote blockchain-enabled health data exchange for regulation, security, and privacy [

14,

19].

- o

Promote standardized AI algorithms to automate information mapping, anti-fraud strategies, and forecast analysis [

5,

14].

-

3.

-

Expand the Funding of Health IT Adoption to the Underprivileged

- o

Increase government-backed investments into the healthcare information infrastructure of healthcare sites with scarce resources [

15,

16,

18].

- o

Support public-private partnerships to promote cloud-based models of Interoperability to deliver scalable, cost-effective health data exchange [

15,

18].

- o

Prioritize investment into AI-powered semantic interoperability solutions to enhance the accessibility of EHR in the developing world [

5,

16].

Table 7.

Key Policy and Governance Takeaways.

Table 7.

Key Policy and Governance Takeaways.

| Policy Framework |

Key Contributions |

Challenges |

| TEFCA (US) |

Nationwide EHR data-sharing compliance |

Voluntary adoption slows the impact |

| HIPAA & GDPR |

Patient data privacy and security mandates |

Regulatory fragmentation limits cross-border exchange |

| EU Digital Health Action Plan |

FHIR-based cross-border EHR integration |

Varying national policies hinder the full implementation |

| WHO Interoperability Strategy |

Global standardization of health data-sharing |

Infrastructure gaps in low-resource settings |

| ISO/TC 215 Health Informatics |

Advances in global semantic interoperability |

Limited enforcement across national health systems |

A cohesive governance strategy with AI governance frameworks and equitable funding models is called upon to provide global health data interoperability. Future efforts will have to harmonize policy within jurisdictions, invest in next-generation technologies, and grant access to frameworks of Interoperability to all healthcare providers regardless of their levels of resources.

Figure 8.

Stakeholder Engagement Models for Successful Interoperability Adoption.

Figure 8.

Stakeholder Engagement Models for Successful Interoperability Adoption.

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Interoperability remains a cornerstone of modern healthcare that enables smooth information exchange, increased care coordination, and well-informed clinical decisions. In this review, the revolutionizing effect of emerging technologies, models of regulation, and collaborative industry efforts are highlighted to provide scalable, secure, and patient-centric health data interoperability.

7.1. Summary of Main Conclusions

Integrating blockchain with AI is revolutionizing interoperability, increasing the data's security, standardizing the data's meaning, and enabling predictive analysis [

5,

14,

19]. Standardization deficiencies, security threats, and alignment with the regulator remain to be solved to allow complete adoption [

4,

13,

16].

Several key lessons have resulted from this review, summarising both the successes and the continuing challenges of implementing Interoperability:

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Blockchain are reshaping Interoperability by improving data security, semantic standardization, and predictive analytics [

5,

14,

19].

FHIR, TEFCA, and international governance models are key to achieving secured and organized data-sharing among healthcare systems [

4,

7].

Standardization, Security, and Regulatory Conformity are significant challenges that call for policy harmonization, robust cybersecurity measures, and investments in infrastructure [

4,

13,

16].

While interoperability standards have advanced significantly, widespread adoption remains uneven due to technical complexity, regulatory fragmentation, and resource disparities. Addressing these issues requires sustained policy innovation, technology investment, and collaborative efforts among key stakeholders.

7.2. Call for Industry Collaboration and Investment

Cross-sector collaboration is essential to accelerate the adoption of interoperability. Governments, healthcare institutions, and technology companies must work together to:

Invest in Scalable AI and Blockchain Solutions for real-time, secure health data exchange, ensuring compliance with global privacy regulations [

5,

14,

18].

Standardizing FHIR and TEFCA Frameworks will enable nationwide and cross-border interoperability, aligning with WHO and ISO health informatics standards [

7,

9,

15].

Expand Health IT Funding in Resource-Limited Settings to bridge digital disparities and support EHR accessibility and telehealth expansion [

16,

18].

Without strong public-private partnerships, interoperability initiatives risk fragmentation and limited scalability. Policymakers and industry leaders must align funding priorities and establish regulatory certainty to foster a sustainable and globally connected digital health ecosystem.

7.3. Next Steps for Research and Implementation

Despite advancements, more research is needed to improve the frameworks of Interoperability, add AI-driven automation, and align policy frameworks. The following need to be addressed with priority:

-

AI-Driven Semantic Interoperability Framework

- o

Development of FHIR-enabled natural language processing (NLP) mapping software [

5,

20].

- o

AI-based automated data transformation models for EHR standardization.

-

Blockchain-Enabled Patient Data Governance

- o

Implementation of smart contracts to grant access to patient-controlled healthcare information [

14,

19].

- o

Regulatory evaluation of blockchain-enabled systems of consent management

-

Cross-Border Regulatory Convergence

- o

TEFCA, GDPR, and WHO interoperability strategies are aligned to ensure secure, global health data exchange [

4,

7,

9,

13].

- o

Creating international data governance models for privacy, security, and ethical AI implementation.

Achieving full-scale Interoperability will require sustained innovation, regulatory sophistication, and astute investments. With the introduction of emerging technologies, strengthening governance frameworks, and international coordination, healthcare systems can proceed toward a fully connected, information-driven digital healthcare environment.

Table 8.

Future Research Priorities in Healthcare Interoperability. This table summarizes key areas for future research and innovation.

Table 8.

Future Research Priorities in Healthcare Interoperability. This table summarizes key areas for future research and innovation.

| Research Focus |

Implementation Need |

Potential Impact |

| AI for Semantic Interoperability

|

NLP for structured health data |

Reduces data inconsistencies |

| Blockchain for Patient Data Ownership

|

Smart contracts for consent management |

Enhances security, privacy compliance |

| Cross-Border Regulatory Harmonization |

Aligning TEFCA, GDPR, and WHO standards |

Facilitates seamless international data exchange |

Final Thoughts:

The future of healthcare interoperability is at the intersection of technology, policy, and industry alignment. AI, blockchain, and the FHIR frameworks will increasingly shape real-time patient-driven healthcare solutions. However, the potential for interoperability can go untapped without aligned governance models, coherent regulation, and equitable funding models. Moving forward, sustained investments, harmonization of the regulator environment, and multi-stakeholder coordination will continue to be the drivers of a connected, secured, and scalable digital healthcare ecosystem.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Table 1.

List of Abbreviations.

Table 1.

List of Abbreviations.

| Abbreviation |

Full Meaning |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| API |

Application Programming Interface |

| CDA |

Clinical Document Architecture |

| EHR |

Electronic Health Record |

| EU |

European Union |

| FHIR |

Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| HIE |

Health Information Exchange |

| HIPAA |

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| HL7 |

Health Level Seven International |

| HIT |

Health Information Technology |

| ISO |

International Organization for Standardization |

| LMICs |

Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| ONC |

Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology |

| PHI |

Protected Health Information |

| PPPs |

Public-Private Partnerships |

| RBAC |

Role-Based Access Control |

| SNOMED CT |

Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine – Clinical Terms |

| TEFCA |

Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement |

| The US. |

United States |

| VHA |

Veterans Health Administration |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

-

Lee AR, Kim IK, Lee E. Developing a transnational health record framework with level-specific interoperability guidelines based on a related literature review. Healthcare. 2021;9(1):67. [CrossRef]

-

Palojoki S, Lehtonen L, Vuokko R. Semantic interoperability of electronic health records: Systematic review of alternative approaches for enhancing patient information availability. JMIR Med Inform. 2024;12:e53535. [CrossRef]

-

Amatayakul M. Health IT and EHRs: Principles and practice. 6th ed. Chicago: American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA); 2016. Available online: https://bookshelf.vitalsource.com/books/9781584265610.

-

Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA). 2024. Available online: https://www.healthit.gov/topic/interoperability/policy/trusted-exchange-framework-and-common-agreement-tefca.

-

Amar F, April A, Abran A. Electronic health record and semantic issues using fast healthcare interoperability resources: Systematic mapping review. J Med Internet Res. 2024;26:e45209. [CrossRef]

-

Health Level Seven International (HL7). Unpacking FHIR’s vital role in healthcare interoperability & TEFCA. 2024. https://blog.hl7.org/npacking-fhirs-vital-role-in-healthcare-interoperability-tefca-insights-from-fast-on-himsstv.

-

European Commission. eHealth Network Guidelines on electronic exchange of health data. 2024. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/d8f7955c-4a2c-4ba2-9aea-25f3044896e8_en?filename=ehealth_health-data_electronic-exchange_general-guidelines_en.pdf.

-

Blanda Helena de Mello BH, Rigo SJ, da Costa CA, da Rosa Righi R, Donida B, Bez MR, et al. Semantic interoperability in health records standards: A systematic literature review. Health Technol. 2022;12(2):255–272. [CrossRef]

-

Donahue M, Bouhaddou O, Hsing N, Turner T, Crandall G, Nelson J, et al. Veterans Health Information Exchange: Successes and Challenges of Nationwide Interoperability. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018:385–394. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30815078.

-

Snyder ME, Nguyen KA, Patel H, Sanchez SL, Traylor M, Robinson MJ, et al. Clinicians' use of Health Information Exchange technologies for medication reconciliation in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: a qualitative analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24(1):1194. [CrossRef]

-

Maldonado JA, Marcos M, Fernández-Breis JT, Giménez-Solano VM, Legaz-García MDC, Martínez-Salvador B. CLIN-IK-LINKS: A platform for the design and execution of clinical data transformation and reasoning workflows. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;197:105616. [CrossRef]

-

HealthIT.gov. Interoperability in action: CMS rule builds on ONC initiatives. 2024. Available online: https://www.healthit.gov/buzz-blog/blog-series-cms-ipps-rule/interoperability-in-action-onc-informs-cms-ruling-on-hospital-measures-for-public-health-and-health-equity-reporting.

-

Federal Register. Health data, technology, and interoperability: Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA). 2024. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/12/16/2024-29163/health-data-technology-and-interoperability-trusted-exchange-framework-and-common-agreement-tefca.

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Implementing public health interoperability. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/data-interoperability/php/public-health-strategy/index.html.

-

HealthIT.gov. FHIR roadmap for TEFCA exchange V.2: FHIR APIs are on their way into TEFCA exchange. 2024. Available online: https://www.healthit.gov/buzz-blog/tefca/fhir-roadmap-for-tefca-exchange-v-2.

-

Blumenthal D, Tavenner M. The "meaningful use" regulation for electronic health records. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(6):501–504. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20647183.

-

Holmgren AJ, Patel V, Adler-Milstein J. Progress in interoperability: Measuring US hospitals' engagement in sharing patient data. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(10):1820–1827. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28971929.

-

Mandel JC, Pollak JP, Mandl KD. The patient role in a federal national-scale health information exchange. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(11):e41750. [CrossRef]

-

Glandon GL, Slovensky DJ, Smaltz DH. Information technology for healthcare managers. 9th ed. Chicago: Health Administration Press; 2020.

-

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America.To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Edited by Linda T. Kohn et al. National Academies Press (US); 2000. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25077248.

-

Ayaz M, Pasha MF, Alzahrani MY, Budiarto R, Stiawan D. The Fast Health Interoperability Resources (FHIR) Standard: Systematic Literature Review of Implementations, Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. JMIR Med Inform. 2021;9(7):e21929. [CrossRef]

-

International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Health informatics—Interoperability and integration reference architecture—Model and framework (ISO 23903:2021). ISO; 2021. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/77386.html.

-

World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe. Accelerating digital health transformation in Europe: a two-year progress report. WHO Europe. 2024 Oct 28. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/28-10-2024-accelerating-digital-health-transformation-in-europe--a-two-year-progress-report.

-

World Health Organization (WHO). Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025. WHO; 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240020924.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).