1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in over 704 million infections and 7.0 million deaths globally [

1,

2]. Since its initial emergence in December 2019, SARS-CoV-2 has undergone numerous mutations, giving rise to several variants of concern (VOCs) [

3,

4]. The Omicron variant, classified as the fifth VOC in November 2021, quickly became the dominant strain worldwide due to its enhanced transmissibility and ability to evade both natural and vaccine-induced immunity [

5,

6]. The high number of mutations in the Omicron variant, especially in the spike protein, facilitated its rapid global spread and raised concerns regarding therapeutic resistance [

7,

8]. Although Omicron is associated with generally milder clinical outcomes compared to previous variants, its indirect impact on healthcare systems, economies, and social structures remains substantial [

9,

10].

The emergence of the Omicron variant marked a shift in the pandemic landscape, characterized by a notable increase in infectivity but a significant reduction in mortality [

11]. Data suggest that the infection fatality rate of Omicron decreased by approximately 78.7%, reflecting a change in the epidemiological behavior of SARS-CoV-2 [

12]. While the number of infections surged during the Omicron wave, both the overall mortality rate and the case fatality rate significantly declined compared to previous waves [

13]. Among the populations most severely impacted by COVID-19 are the elderly, particularly those residing in care homes. Life expectancy for care-home residents in Scotland notably decreased during the pandemic, reaching its lowest point in 2019/20 [

14]. In the Midwest of the United States, the fatality rate for individuals aged 65 and older was 1.03%, leading to a loss of 34 days in life expectancy [

15]. A hypothetical scenario of 1 million COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. would lead to a 2.94-year decrease in life expectancy for 2020, with those dying losing an average of 11.7 years of expected remaining life [

16].

Recent studies have underscored the critical importance of timely diagnosis and treatment in determining COVID-19 outcomes [

17,

18]. Delays between symptom onset and diagnosis, as well as between diagnosis and treatment, are significant predictors of disease progression to pneumonia and hospitalization, particularly in high-risk patients [

19]. Early diagnosis is associated with improved prognosis, with patients diagnosed within five days of symptom onset experiencing better outcomes [

20]. Timely intervention is also correlated with faster disease resolution and lower CT scores, reflecting less severe lung involvement [

21]. These findings emphasize the urgent need for easy access to medical care and prompt antiviral treatment to prevent disease progression and hospitalization in high-risk patients [

19].

In this observational study, we report on a COVID-19 cluster that occurred in a geriatric care facility. Our investigation focused on the impact of rapid diagnosis and immediate initiation of treatment on the short-term outcomes of COVID-19 infection. Additionally, we compared survival rates between infected and non-infected individuals during the same period. Furthermore, we analyzed survival rates across three distinct periods: prior to the COVID-19 pandemic during 2018-2019(Period 1), during the pandemic when no COVID-19 cases were reported in the facility during 2020-2021(Period 2), and during the occurrence of the COVID-19 cluster during 2022-2023(Period 3).

2. Materials and Methods

Facility

The Toshiwakai Long-Term Care Facility (LTCF) operates three distinct buildings in Nagoya City, accommodating 100, 120 and 130 residents, respectively. Each facility adheres to a standardized protocol established by Toshiwakai, ensuring consistency in care delivery. Staffing at each facility includes a designated primary physician, as well as nursing and care staff appropriate to meet the specific nursing care levels required by residents.

Residents

Resident admission criteria were based on care levels defined by the nationally standardized certification [

22]. All residents from the three facilities were included in the study, covering the period from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2023. This timeframe was further divided into three distinct periods:

Period 1: Pre-COVID-19 pandemic, from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2019

Period 2: During the pandemic in Japan, when no COVID-19 cases were reported in the Toshiwakai LTCF, from January 1, 2020, to December 31, 2021

Period 3: During the COVID-19 cluster outbreak at Toshiwakai LTCF, from January 1, 2022, to December 31, 2023

Residents who stayed across consecutive periods were counted in each period and included in the analysis for comparative purposes.

Prevention and Diagnostic Protocols

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan in 2020 [

23], strict preventive measures were implemented in Toshiwakai LTCF. Direct visits by family members were restricted, and all residents and nursing were obligated to wear masks and underwent monthly SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing via nasal swabs. Nursing staff were deemed non-infected only after four consecutive antigen tests confirmed negative results for all close-contact colleagues and residents under their care. From the onset of the COVID-19 cluster in 2022, measures to separate symptomatic individuals from asymptomatic individuals were further reinforced. Residents exhibiting symptoms such as fever, upper respiratory tract issues, respiratory symptoms, neurological symptoms, or gastrointestinal symptoms were immediately isolated in private rooms or comparable facilities. Up to four diagnostic tests, including PCR or NEAR, were conducted at approximately 12-hour intervals as clinically indicated. Close-contact residents of suspected cases were subjected to the same diagnostic testing protocols. To minimize transmission risk, infected residents were provided with meals and daily cleaning support separately from non-infected residents, and their movement in the facility was restricted.

Treatment Protocols

Treatment was promptly initiated upon detection of infection, following the protocols outlined below: Remdesivir (200mg once intravenously on day 1, 100mg on day2 and 3), Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir (600 mg pe per r day orally for 5 days), and Molnupiravir (1600 mg per day orally for 5 days). In two cases, Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir (600 mg per day orally) was supplemented with either Sotrovimab (500 mg once intravenously) or Casirivimab (600 mg once intravenously).

Comparison of Demographic Parameters

The age for each period was defined as the individual’s age at the start of that period. The Degree of Care was reclassified into three categories—Low, Moderate, and High—according to the Japanese governmental insurance classification system [

22]. Specifically, the "low" category includes support levels and level 1; "Moderate" includes levels 2 and 3; and "High" includes levels 4 and 5. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was calculated according to the original rating system [

24]. Additionally, the number of vaccinations received prior to the start of Period 3 was compared across groups. The index date for calculating the survival rate was the start date of each period for the inter-period comparison and the admission date of each resident for the comparison between infected and uninfected residents in Period 3.

Voluntary vaccination against COVID-19 began in Japan in April 2021. The initial and second doses were administered approximately 3 to 4 weeks apart, followed by a booster dose (third shot) approximately six months later. Subsequent booster doses were administered at intervals of approximately six months thereafter. Since the number of vaccinations varied among infected residents based on the timing of infection during Period 3, direct comparison with uninfected residents was challenging. Therefore, the number of vaccinations received before the start of Period 3 was compared between the infected and uninfected groups.

Comparison of Symptoms

Symptoms during COVID-19 infection were obtained from daily logs and categorized into six distinct groups: fever, upper respiratory tract symptoms, respiratory symptoms, neurological symptoms, fatigue, and gastrointestinal symptoms. The day treatment commenced (i.e., the day infection was detected) was designated as Day 0. Symptom presence was subsequently assessed on Days 3, 7, and 10, based on admission logs. Fever was defined as an increase in body temperature of 0.8°C or more compared to the baseline temperature recorded approximately two weeks prior, in the absence of symptoms. For patients with elevated body temperature, the progression of temperature change from Day 0 to Day 10 was analyzed. Upper respiratory symptoms were defined as the new onset of sore throat, nasal congestion, or hoarseness. Respiratory symptoms included the new onset of cough, sputum production, or wheezing. Neurological symptoms included the new onset of headache or taste disturbances. Fatigue was recorded if newly developed, and gastrointestinal symptoms included the new onset of diarrhea, vomiting, or loss of appetite.

Survival Time Comparison

Survival times were compared between infected and non-infected residents within Period 3. Additionally, survival times across Periods 1 to 3 were compared.

Statistical Analysis

Age was reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), with differences between groups assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The male-to-female ratio across groups was compared using the Chi-square test. Symptom development was presented as a percentage, and comparisons between days 0 and 10 were conducted using McNemar's test with Holm’s correction. Survival rate, vaccination count, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) were expressed as mean ± SD, with intergroup comparisons also evaluated via one-way ANOVA. The level of care required was presented as a percentage and analyzed with the Chi-square test. Survival time between infected and uninfected groups was illustrated using the Simon and Makuch’s modified Kaplan-Meier curves [

25], with group comparisons conducted by selecting only the first infection episode and applying the Mantel Byar test. Multifactorial analysis of survival time was performed using time-dependent Cox regression [

26,

27]. Survival times for periods 1 through 3 were visualized with Kaplan-Meier plots and compared using the log-rank test, followed by Cox regression analysis. Holm's method was used to adjust for multiple comparisons between periods.

3. Results

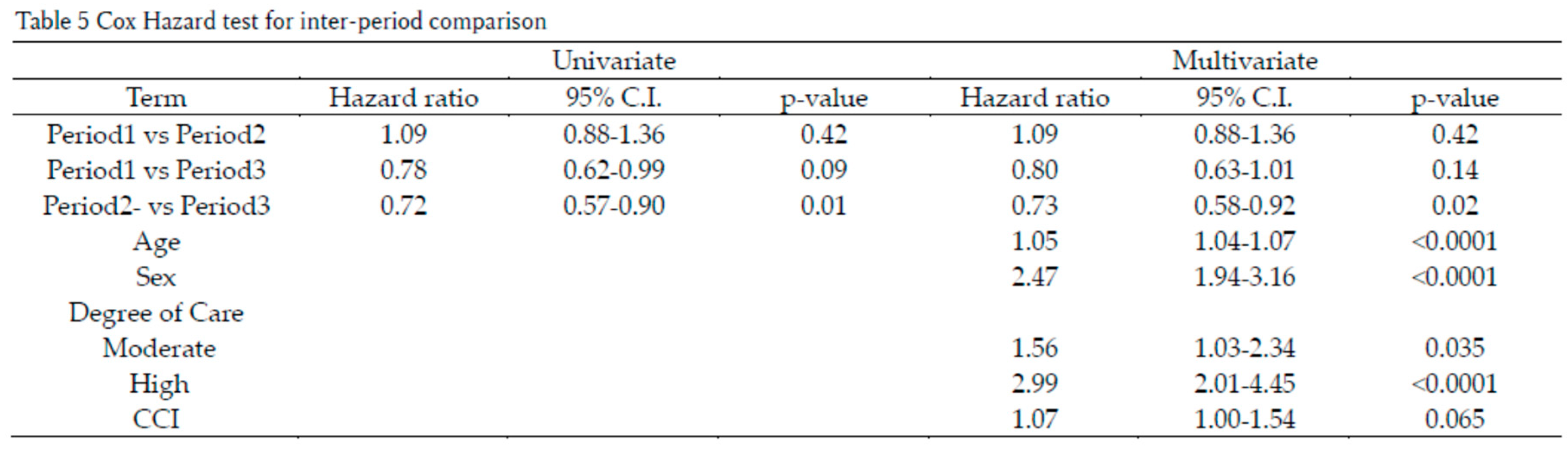

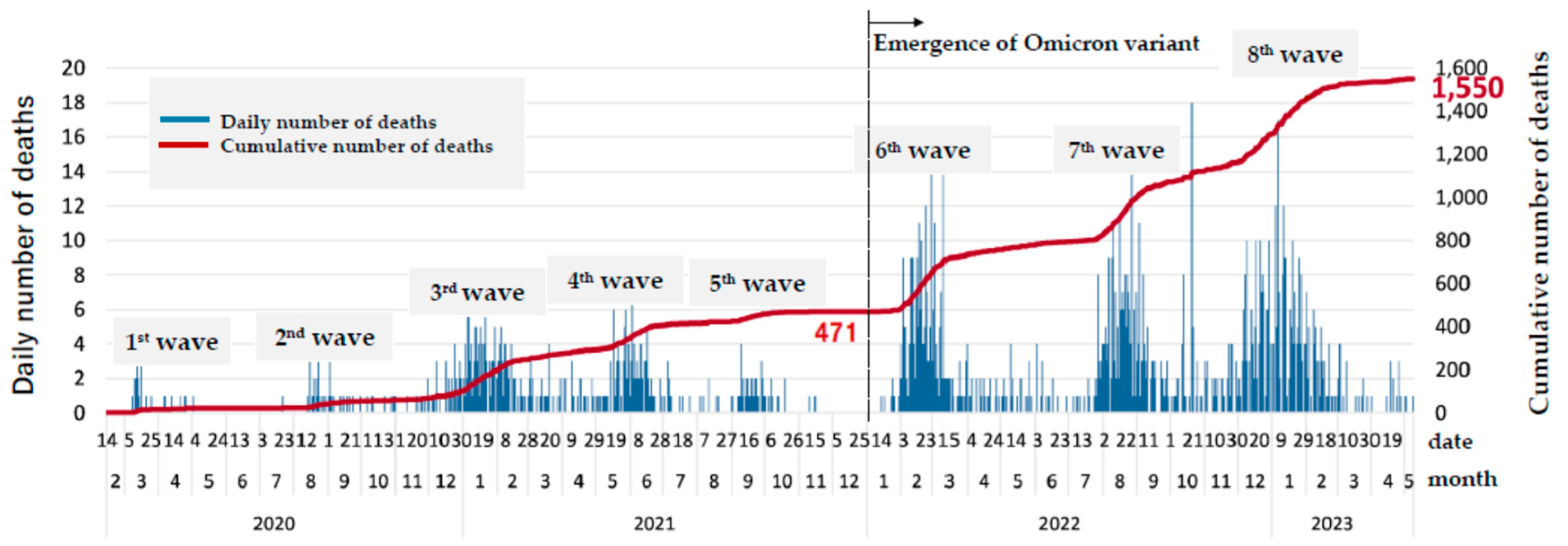

The Japanese government designated COVID-19 as an infectious disease, requiring mandatory daily reporting of new cases and deaths by law starting on February 7, 2020. Up until May 8, 2023, when the reporting system was revised, Japan experienced eight waves of COVID-19. From that date onward, weekly reports of new cases from 70 sentinel clinics in the City of Nagoya were used for surveillance. During Period 3, spanning from January 1, 2022, to December 31, 2023, the City of Nagoya experienced significant surges in COVID-19 cases across the 6th to 9th infection waves.

Figure 1 illustrates the daily and cumulative number of deaths up to the 8th wave. By the end of the 5th wave on December 31, 2021, a total of 471 fatalities had been reported among 43,905 confirmed cases. Following this period, an additional 1,079 fatalities occurred among 638,113 reported cases during the 6th to 8th waves, up until May 8, 2023.

Correspondingly, the Toshiwakai Long-Term Care Facility (LTCF) experienced outbreaks that were initially triggered by care workers (represented by open triangles) and subsequently spread to residents (represented by closed circles) (

Figure 2).

A total of 255 care workers and 231 residents were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection through antigen testing, PCR, or NEAR testing. Among the infected residents, 210 experienced a single infection episode, 20 had two episodes, and one resident had three episodes, resulting in a cumulative total of 253 confirmed infection episodes.

Of these episodes, 145 (57.3%) involved symptomatic residents, while 108 (42.7%) remained asymptomatic. For the 145 symptomatic episodes, the median interval from symptom onset to diagnosis was 0 minutes (IQR: 0–55), although six patients required 24–46 hours for infection confirmation. Treatment was initiated promptly following diagnosis, even during night shifts. Antiviral monotherapy was administered as follows: remdesivir in 145 episodes, nirmatrelvir/ritonavir in 78 episodes, and molnupiravir in 30 episodes. Combination therapy was employed in three episodes: nirmatrelvir/ritonavir with sotrovimab or casirivimab/imdevimab in two episodes, and remdesivir with casirivimab/imdevimab in one episode.

Among the infected residents, four patients aged 88–93 years died within 10 days, two of whom were in terminal stages prior to infection onset and one was diagnosed 46 hours from the onset of the fever. Additionally, five patients required hospital admission within 10 days of infection: two for fall-related fractures and three for dehydration. Excluding these nine patients, a total of 244 infection episodes were analyzed over a 10-day period.

Comparison of Symptoms

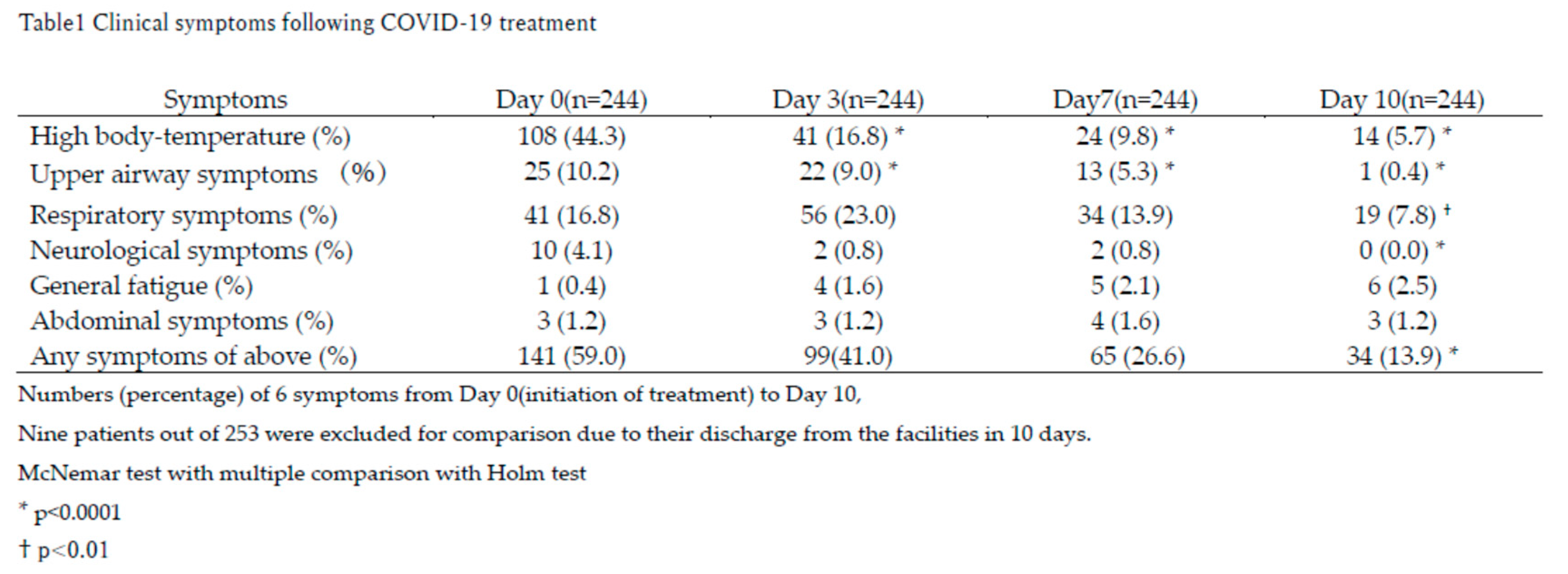

The primary symptoms observed on Day 0 (the initiation of treatment) included fever, upper airway symptoms, and respiratory symptoms (Table 1).

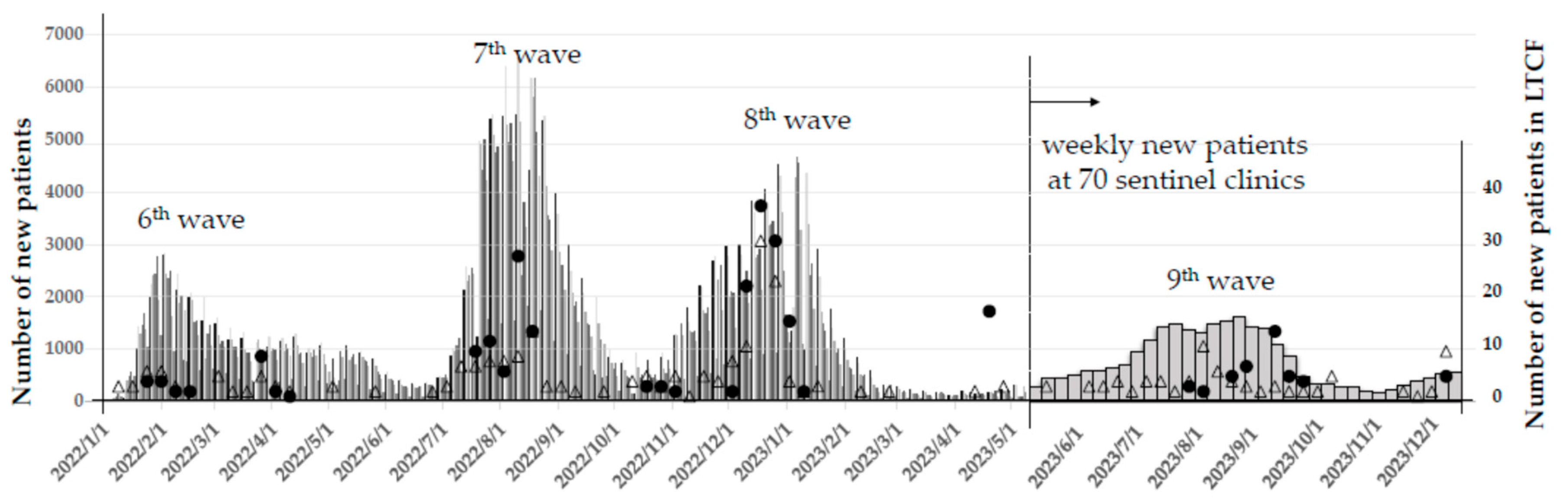

Fever significantly and rapidly decreased by Day 3 compared to Day 0 (*p<0.0001) and further normalized by Day 10 compared to Day 3 (†p<0.05), as shown in

Figure 3.

Upper airway and respiratory symptoms persisted longer but showed gradual improvement over time. By Day 10, neurological symptoms had completely resolved, while fever and upper airway symptoms were nearly absent in most patients (Table 1).

Despite these improvements, a small subset of patients reported persistent symptoms beyond Day 10. General fatigue and abdominal symptoms, though uncommon, were reported by 2.5% and 1.2% of patients, respectively. By Day 10, approximately 13.9% of patients still experienced any symptoms, predominantly respiratory symptoms, fever, and general fatigue (Table 1).

Notably, respiratory symptoms initially worsened by Day 3 (23.0%) before gradually resolving by Day 10 (7.8%; † p<0.01), indicating a slower recovery trajectory compared to fever. This suggests that antiviral treatment was most effective in resolving fever, while other symptoms required additional time for full resolution.

Comparison Between Infected and Uninfected Groups

During Period 3, when the Toshiwakai LTCF experienced a surge in COVID-19 cases (

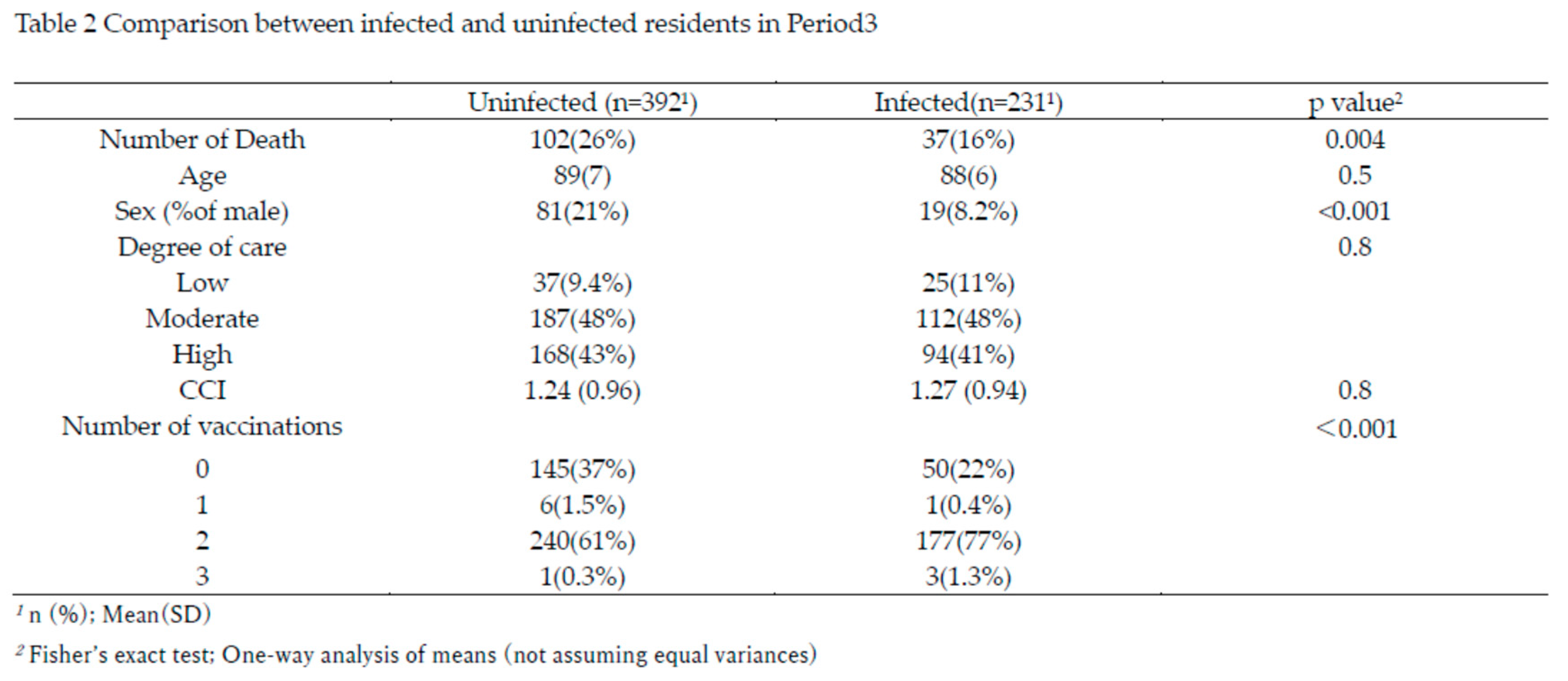

Figure 2), residents were divided into infected (n=231) and uninfected (n=392) groups for comparison. The characteristics of these two groups are summarized in Table 2.

The total number of deaths was significantly lower in the infected group (16%) compared to the uninfected group (26%, p=0.004). Although age, care burden, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) were comparable between groups, the proportion of males was significantly lower in the infected group (p<0.001). The number of vaccinations differed significantly between groups; 77% of infected residents received two vaccinations, compared to 61% in the uninfected group (p<0.001), resulting in a 16% higher rate of immunity induction among the infected group.

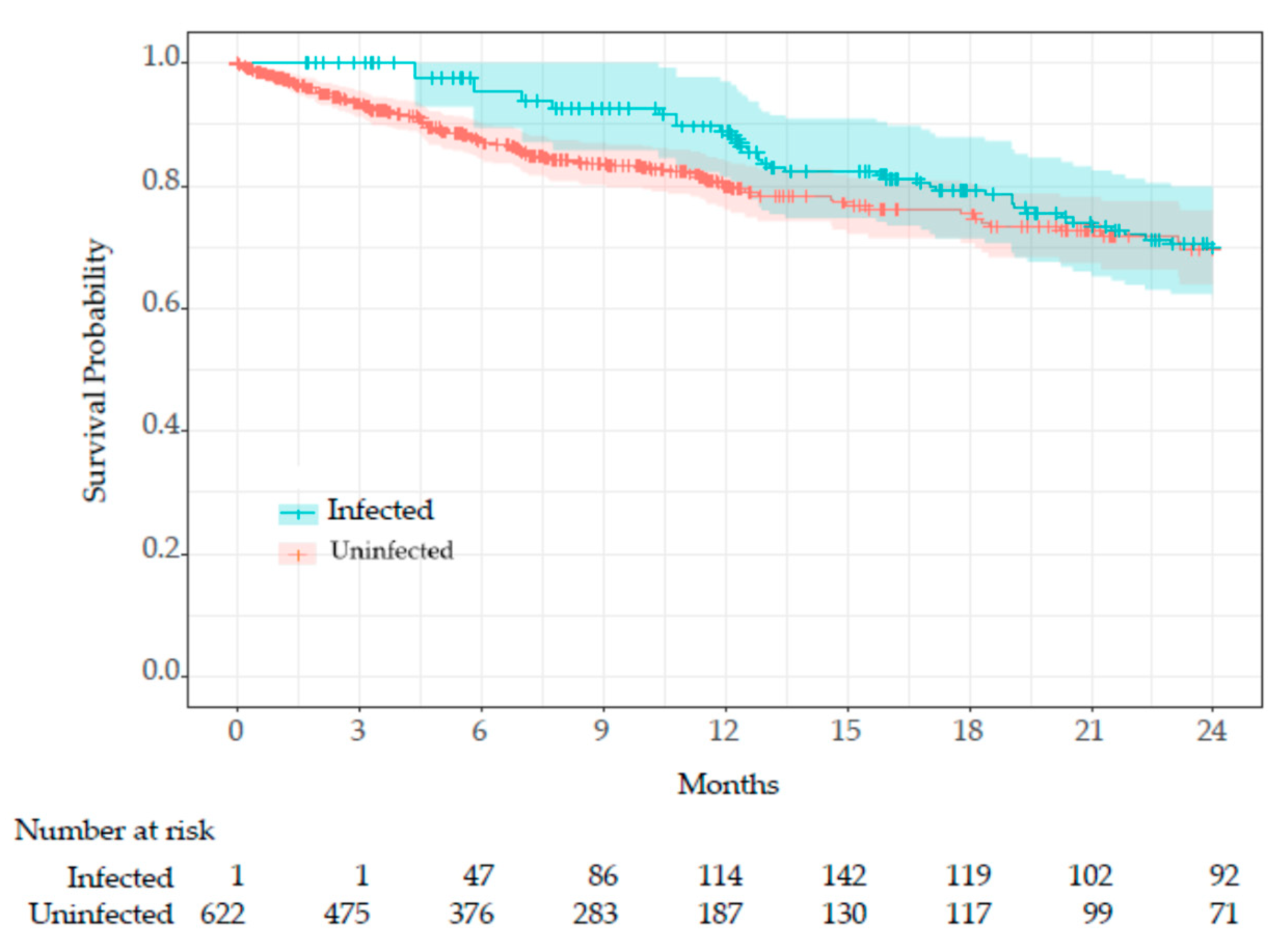

COVID-19 infection was treated as a time-dependent variable, and survival time was compared using the Simon and Makuch’s modified Kaplan-Meier curves (

Figure 4).

Since all residents (n=622) were uninfected at the beginning of Period 3 (January 1, 2022) or at the time of admission, the entire cohort was initially at risk. As uninfected residents transitioned to the infected group, the number of at-risk infected residents increased. The Mantel-Byar test indicated no significant difference in survival between groups (p=0.42).

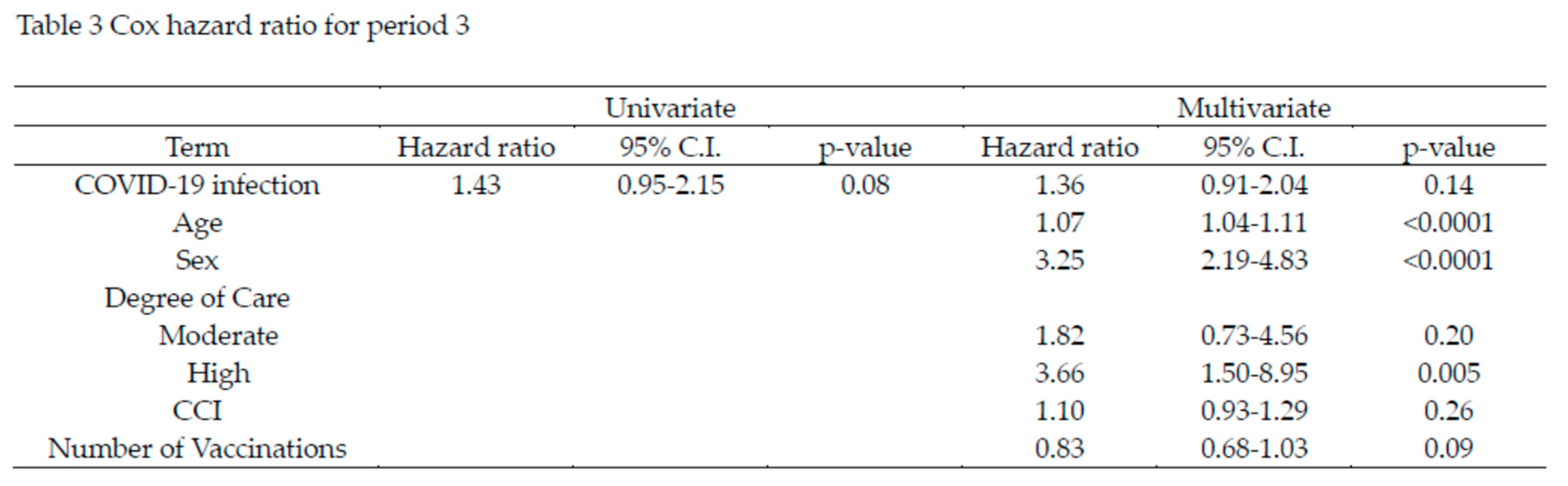

The time-dependent Cox proportional hazards analysis for Period 3 is shown in Table 3. In the univariate analysis, COVID-19 infection was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.43, but this was not statistically significant (p=0.08). In the multivariate analysis, which accounted for age, sex, care level, CCI, and number of vaccinations, COVID-19 infection had an HR of 1.36, though it remained non-significant (p=0.14). Age and sex were significant risk factors, with age showing an HR of 1.07 (p<0.0001), and male sex showing an HR of 3.25 (p<0.0001). Care level High was also a significant risk factor, with an HR of 3.66 (p=0.005). While the number of vaccinations reduced the HR by 17%, this effect was not statistically significant (p=0.09).

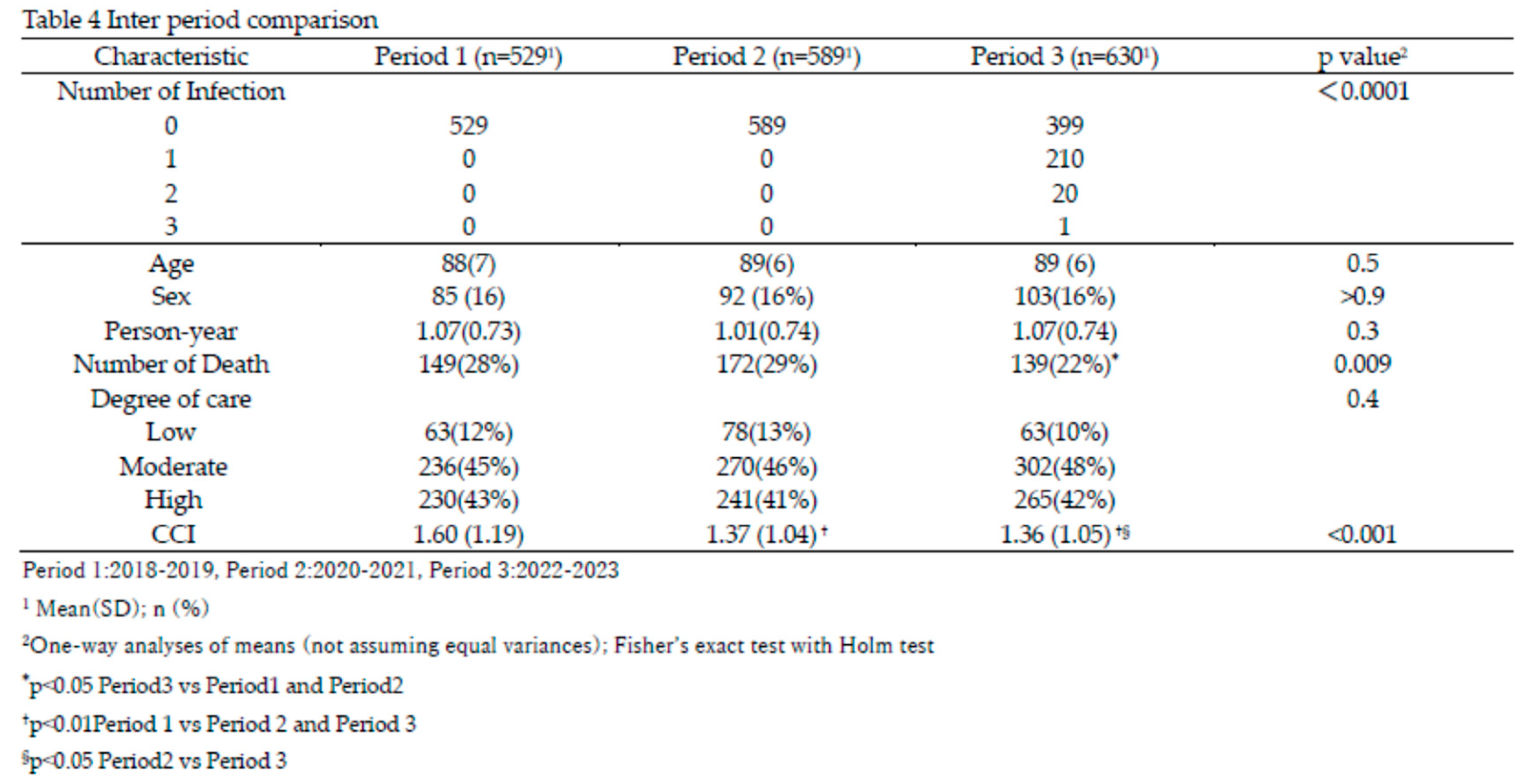

Comparison Between Periods

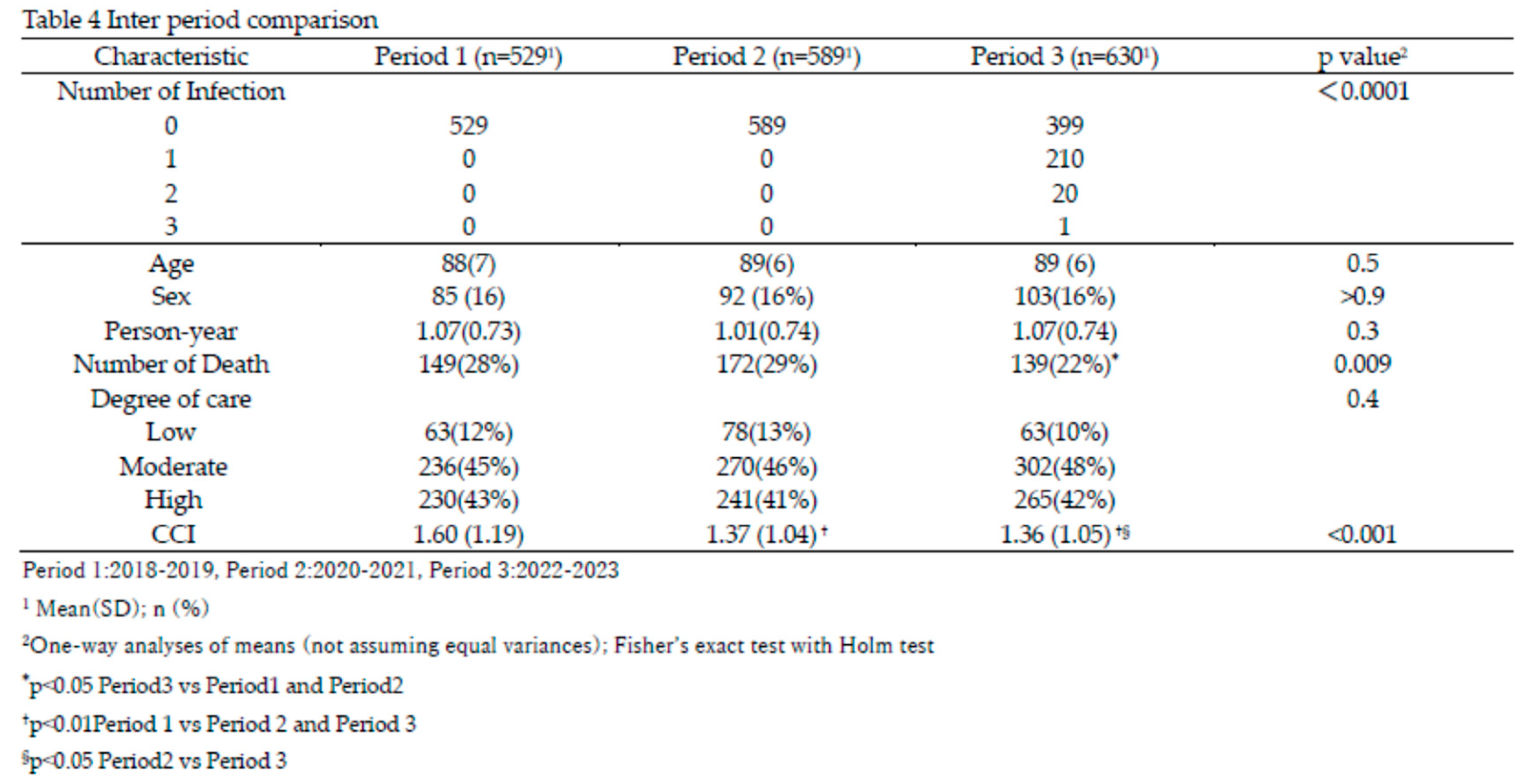

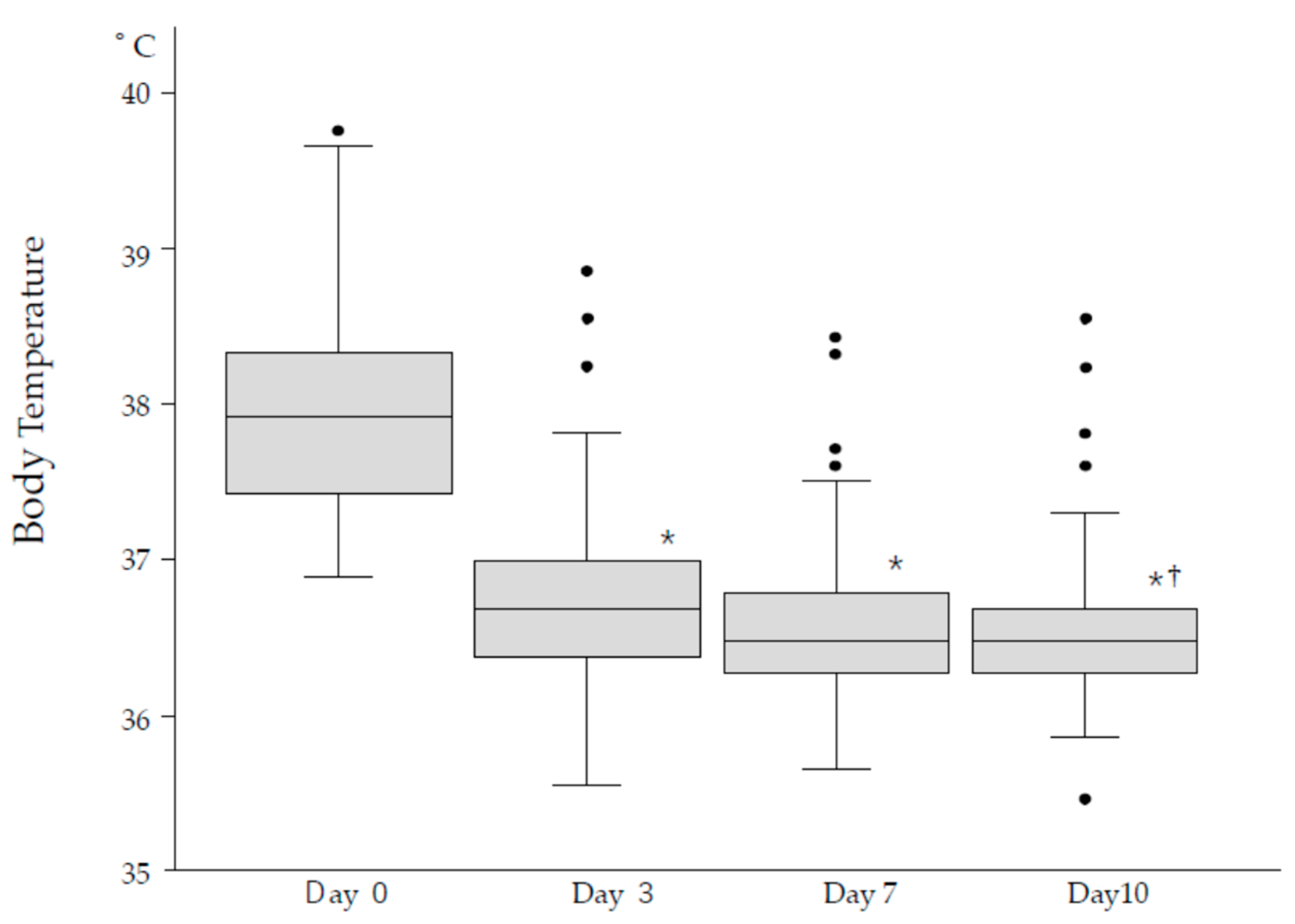

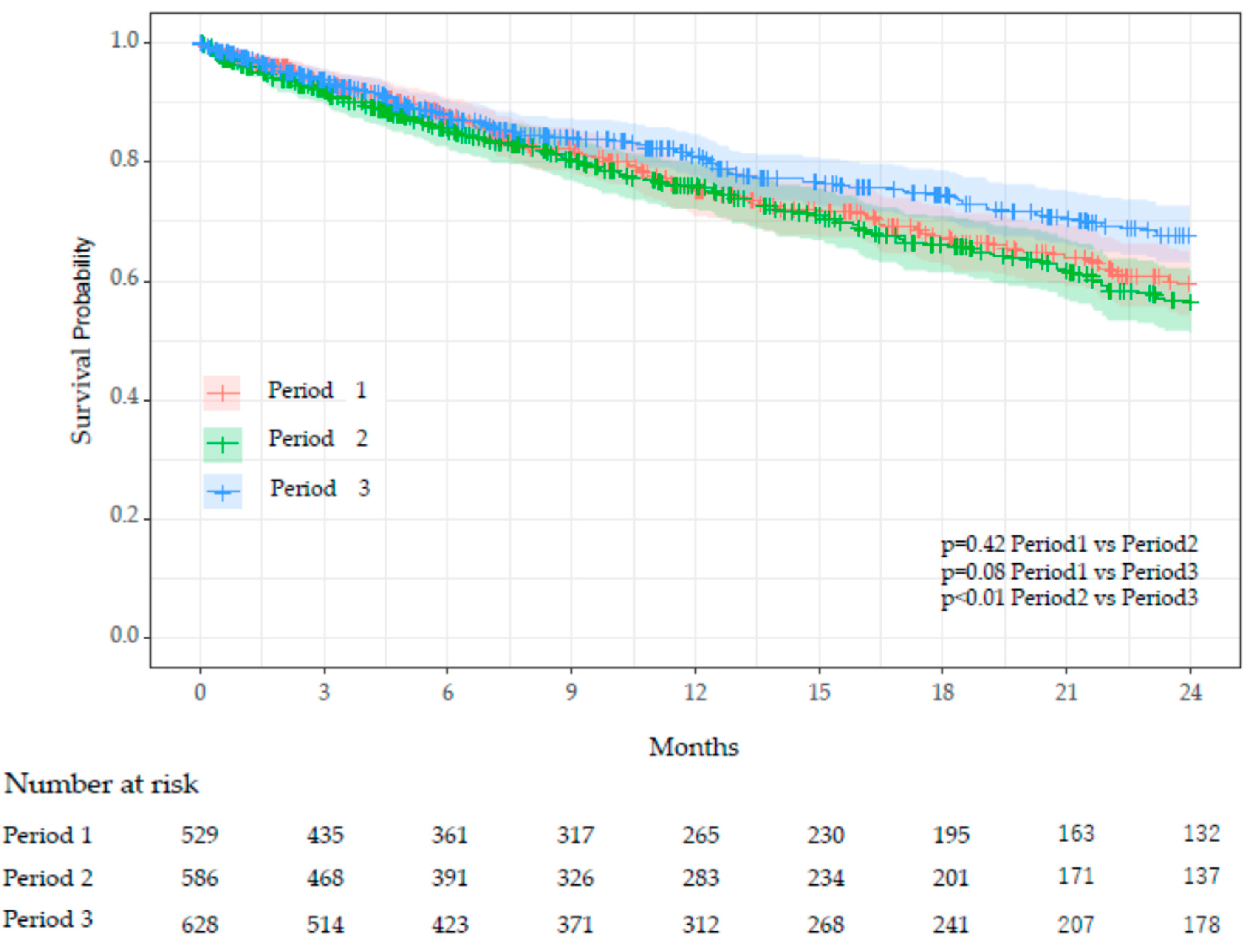

Table 4 presents an inter-period comparison of key characteristics. COVID-19 infections among residents occurred exclusively in Period 3, during which 210 residents experienced a single episode, 20 had two episodes, and one had three episodes. There were no significant differences in age, sex, or person-years between periods. However, the number of deaths was significantly lower in Period 3 (22%) compared to Period 1 (28%) and Period 2 (29%), with adjusted p-values of 0.012 (Period 1 vs Period 3) and 0.045 (Period 2 vs Period 3). The CCI was significantly higher in Period 1 (mean 1.60) compared to Period 2 (1.37) and Period 3 (1.36), with adjusted p-values of 0.005 (Period 1 vs Period 2) and 0.004 (Period 1 vs Period 3). Survival curves using Kaplan-Meier plots revealed significant differences in survival probabilities between Period 2 and Period 3 (adjusted

p<0.01), while no significant differences were observed between Period 1 and Period 2 or Period 1 and Period 3 (

Figure 5).

Cox proportional hazards analysis showed that, compared to Period 2, the hazard in Period 3 was significantly reduced by 27% (p=0.02) (Table 5). An increase in care level significantly elevated the hazard; care level Moderate increased the hazard by 50% (p=0.035), and care level High increased it by 199% (p<0.0001). Although CCI tended to increase the hazard, this trend was not statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Long-term care facilities (LTCFs) are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 cluster outbreaks. Before the Omicron surge in 2021, a meta-analysis reported that the incidence rate among LTCF residents was 45% per facility, with a mortality rate of 23% [

28]. The emergence of the Omicron variant and its sublineages dramatically altered the infection landscape. While infectivity significantly increased, the severity and mortality rates declined [

29,

30] causing explosive transmission especially in the closed facility such as in LTCF. Even though mortality was decreased the number of deaths in elderlies increased. Press release from Nagoya city government reported that the total number of deaths was 471 and mortality was 1.04% before Omicron emergence at the end of December 2021. Although mortality decreased to 0.17%, total number of deaths counted 1079 in the next 1.5 year (figure1) and more than 90% was elderlies over age of 60. The first case of COVID-19 at the Toshiwakai LTCF was a care worker, identified on December 24, 2020. Four additional care workers were tested positive in 2021 before the Omicron variant emerged, but no cases were detected among residents. However, after a care worker was diagnosed with COVID-19 on January 15, 2022—likely due to Omicron—the number of resident cases surged dramatically starting February 4, 2022 (

Figure 2). Since face-to-face meetings between residents and their relatives or friends had been restricted since 2020, it is highly likely that infections were introduced by symptomatic care workers. Once the first resident case appeared on February 4, the number of infected individuals escalated rapidly (

Figure 2). During the 7th and 8th waves, the weekly number of new cases of residents and care workers reached 100, severely disrupting facility operations. Serial antigen testing, previously reported as effective for detecting new cases [

31], was implemented up to four times during complete contact surveys, revealing 108 asymptomatic cases out of 253 infection episodes (42.7%). This sense of urgency heightened care workers’ vigilance, leading to more proactive monitoring of residents' conditions and stricter isolation measures for symptomatic patients. Since early outpatient treatment has been shown to mitigate disease progression [

19], antiviral therapy was initiated immediately upon confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection, even during night shifts. Given the shorter incubation and serial intervals of the Omicron variant compared to ancestral strains [

32,

33], early detection and prompt treatment were crucial in suppressing transmission and preventing severe illness.

In our study, 59% of patients exhibited symptoms, with fever being the most prominent, followed by respiratory and upper airway symptoms (Table 1). While most symptoms resolved within 10 days, 13.9% of patients continued to experience symptoms, predominantly fever, respiratory distress, and general fatigue. Figure3 illustrates representative fever patterns in 108 episodes, showing that although variations existed, fever generally subsided within three days and further normalized toward Day 10. During the acute phase of infection (the first 10 days), four residents died, and three required hospitalization due to COVID-19. These observations initially led us to anticipate that COVID-19 infection might result in higher mortality among elderly residents in isolated facilities, such as our LTCF. Contrary to this expectation, the crude mortality rate in the infected group (16%) was significantly lower than that of the uninfected group (26%) (Table 2).

During the infection cluster in period 3, stringent infection control measures were implemented, and antiviral treatments were administered promptly. The infected group also had a significantly higher proportion of female residents compared to males (Table 2). Although the underlying reason for this gender disparity is unclear, it is possible that closer social interactions among women in LTCFs may have facilitated greater transmission compared to men. It is well-documented that women generally have lower mortality risks than men in the general population [

34,

35,

36], and recent findings from the Delta and Omicron eras suggest that women experienced less severe illness compared to men [

37,

38].This study also revealed a significant difference in vaccination rates between the infected and uninfected groups, with the infected group appearing to have received more vaccinations prior to the onset of the infection cluster in period 3 (Table 2). However, as vaccination efforts continued throughout the two-year period of period 3, assessing the protective effect of vaccination in preventing infection based solely on this dataset is challenging. While the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 has been reported to evade neutralizing antibodies generated by current mRNA vaccine [

39], vaccination may still have played a role in mitigating disease severity, as suggested by previous findings in LTCF populations [

40,

41].

To assess the association of COVID-19 infection on survival in long-term care facility (LTCF) residents, a survival analysis was conducted. Given the observational nature of the study and the heterogeneity in infection timing during residents’ stays, the pre-infection period was considered an immortal time. To address this bias, survival analysis incorporated infection as a time-dependent covariate [

26,

27]. Among the factors examined, age, sex, care level, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) emerged as significant contributors to mortality, while vaccination demonstrated a protective effect, albeit without statistical significance (Table 3).

After adjusting for confounding variables, COVID-19 infection was associated with a hazard ratio of 1.36 (95% CI: 0.91–2.04, p=0.14, Table 3), indicating a potential, though statistically non-significant, increase in mortality risk. The survival curve analysis (

Figure 4) revealed no significant survival difference between infected and uninfected groups (p=0.42). While sex differences between the groups (with a higher proportion of males in the uninfected group) might have influenced these results, the implementation of stringent infection control measures, such as comprehensive contact tracing, wearing masks, isolation of COVID-19 cases and prompt antiviral treatment, likely played a crucial role in mitigating the adverse outcomes of COVID-19 infection. These findings suggest that robust infection control and timely therapeutic strategies may effectively offset the survival impact of COVID-19 infection in LTCFs, warranting further investigation to confirm these observations.

Vaccination comparisons between groups in Period 3 were complicated by disparities in vaccination opportunities. Although booster doses (third shots) were administered to only a limited number of residents due to the mid-2021 rollout, the rate of two or more vaccinations was significantly higher in the infected group (Table 2), this finding may reflect differences in vaccine accessibility rather than vaccine ineffectiveness. Indeed, Cox proportional hazard analysis indicated a 17% reduction in mortality risk with vaccination, although this result did not reach statistical significance (Table 3). These data suggest that while current vaccines may offer limited protection against Omicron variant infections, they retain statistically significant efficacy in reducing disease severity and mortality [

42]. This highlights the critical role of vaccination in mitigating COVID-19 outcomes, even in high-risk populations such as LTCF residents.

A deeper analysis of survival rates across the three periods—Period 1 (pre-COVID-19 in Japan), Period 2 (COVID-19 surge in Japan without outbreaks in Toshiwakai LTCF), and Period 3 (COVID-19 clusters in Toshiwakai LTCF)—yielded surprising results. The survival rate in Period 3 was significantly higher than in Period 2 and slightly higher than in Period 1, though the latter was not statistically significant (Table 4,

Figure 5). Importantly, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) of residents in Period 3 was significantly lower than in Periods 1 and 2, which could partially explain the lower mortality observed in Period 3 [

43](Table 4). However, this difference alone is unlikely to account for the substantial reduction in mortality. Multivariate Cox hazard analysis showed that HR significantly decreased by 27% in Period 3 compared with Period 2 (p = 0.02) and tended to decrease by 20% compared with Period 1, though this did not reach statistical significance (Table 5). In contrast, HR increased by 9% from Period 1 to Period 2, possibly indicating undetected cases during Period 2 due to limited routine testing and standard infection control measures. Furthermore, the implementation of reinforced infection control measures in Period 3 likely reduced the transmission of not only SARS-CoV-2 but also other respiratory viruses, such as influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), metapneumovirus and others [

44]. Studies have demonstrated a dramatic decline in these infections during the COVID-19 pandemic, attributed to widespread use of personal protective equipment, reduced social interactions, and enhanced hygiene practices [

45,

46]. Conversely, the resurgence of RSV and influenza following the relaxation of these measures underscores the efficacy of strict infection control in mitigating respiratory viral outbreaks [

47,

48,

49]. These findings highlight the critical role of rigorous infection control and timely interventions in improving survival outcomes during pandemics and preventing the spread of respiratory infections.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the critical role of comprehensive infection control measures and prompt antiviral therapy in managing COVID-19 outbreaks in long-term care facilities (LTCFs). Despite the highly transmissible Omicron variant, our findings reveal no significant increase in mortality among infected residents compared to uninfected residents. The survival rates during the Omicron cluster (Period 3) were unexpectedly higher than in previous periods, underscoring the efficacy of interventions such as rigorous infection control protocols. Additionally, our results suggest that enhanced infection control measures not only mitigate COVID-19 outcomes but may also reduce the transmission of other respiratory pathogens. These outcomes reinforce the importance of maintaining robust preventive and therapeutic strategies in high-risk populations like LTCF residents.

6. Limitation

Retrospective Design: This study utilized a retrospective observational approach, which may introduce inherent selection bias and limit the ability to establish causal relationships between interventions and outcomes.

Single-Facility Data: The analysis was conducted in a single long-term care facility, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings to other facilities with different demographic characteristics, healthcare systems, or infection control protocols.

Unmeasured Confounding Factors: While efforts were made to adjust for age, sex, care levels, comorbidity index (CCI), and vaccination status, other potential confounders—such as undiagnosed asymptomatic infections or the presence of other comorbid conditions—were not comprehensively analyzed.

Vaccination Effectiveness: The study observed significant differences in vaccination rates between infected and uninfected groups. However, the inability to directly compare vaccination timing and its potential confounding effect on outcomes limits the interpretation of its role in mitigating infection severity.

Limited Scope on Respiratory Infections: The findings focus on SARS-CoV-2 outcomes. While preventive measures may mitigate the spread of other respiratory pathogens, this hypothesis was not directly examined.

Author Contributions

All authors meet the ICMJE authorship criteria and have made substantial contributions to the following: (1) the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (3) final approval of the version to be submitted. H.S.; J.K.; Y.H.; and H.M extracted the data. H.S.; M.H.; K.I.; Y.I.; M.M. and M.O. analyzed the data. M.M. M.O.and H.S. were the chief investigators and were responsible for the analysis. All authors drafted, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a JSPS-in Aid for Scientific. Research (C), Japan [grant number 21K08216] and Research funding by the National Center for Global Health and Medicine [funding number 2020-207].

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Daiyukai Health System (approval no 2022e006) and was conducted in accordance with the principles evinced in the 1964 Declarationof Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement

The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Bioethical Committee due to the retrospective nature of this study.

Data Availability Statement

All data for statistical analysis was collected from the daily records of Toshiwakai LTCF. The dataset generated and analyzed during this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the care workers at Toshiwakai LTCF for their unwavering dedication to resident management during the COVID-19 surge.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have no conflict of interest to conduct this study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LTCF |

Long term care facility |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus disease-2019 |

| VOC |

Variant of concern |

| C.I, |

Confidence Interval |

References

-

Worldometer. available at https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

-

World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. available at https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/data.

- Harvey, W.T.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, K.; et al. The biological and clinical significance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat Rev Genet 2021, 22, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, S.S.A. and Q.A. Karim, Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: a new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 2126–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaway, E.; Ledford, H. How bad is Omicron? What scientists know so far. Nature 2021, 600, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejnirattisai, W.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron-B.1.1.529 leads to widespread escape from neutralizing antibody responses. Cell 2022, 185, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; et al. Omicron escapes the majority of existing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. Nature 2022, 602, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, T.; et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet 2022, 399, 1303–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, T. ; The Emergence of Omicron: Challenging Times Are Here Again! Indian J Pediatr 2022, 89, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielle-Iuliano, A.; Brunkard, J.M.; Boehmer,T.K. Peterson, E.; Adjei, A.; et al. Trends in Disease Severity and Health Care Utilization During the Early Omicron Variant Period Compared with Previous SARS-CoV-2 High Transmission Periods — United States, December 2020–January 2022, in Morbidity and Mortality Report. 2022, CDC. available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7104e4.htm.

- Liu, Y.; et al. Reduction in the infection fatality rate of Omicron variant compared with previous variants in South Africa. Int J Infect Dis, 2022. 120: p. 146-149. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.J.; et al. Fatality Rates After Infection With the Omicron Variant (B.1.1.529): How Deadly has it been? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Acute Med 2024, 14, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, J.K.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on care-home mortality and life expectancy in Scotland. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, P.N.B.; et al. The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Elderly: Population Fatality Rates, COVID Mortality Percentage, and Life Expectancy Loss. Elder Law J 2022, 30, 33–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, J.R. and R.D. Lee, Demographic perspectives on the mortality of COVID-19 and other epidemics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 22035–22041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.H.; et al. Clinical Outcomes Following Treatment for COVID-19 With Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir and Molnupiravir Among Patients Living in Nursing Homes. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2310887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

COVID-19 Treatment Clinical Care for Outpatients. CDC. available at https://www.cdc.gov/covid/hcp/clinical-care/outpatient-treatment.html.

- Shimizu, H.; et al. COVID-19 symptom-onset to diagnosis and diagnosis to treatment intervals are significant predictors of disease progression and hospitalization in high-risk patients: A real world analysis. Respir Investig 2023, 61, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; et al. Earlier diagnosis improves COVID-19 prognosis: a nationwide retrospective cohort analysis. Ann Transl Med 2021, 9, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; et al. Timely Diagnosis and Treatment Shortens the Time to Resolution of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pneumonia and Lowers the Highest and Last CT Scores From Sequential Chest CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2020, 215, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, T.; H. Inokuchi, and H. Yasunaga, Services in public long-term care insurance in Japan. Ann Clin Epidemiol 2024, 6, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, E.; H. Ino, and A. Akabayashi Chronology of COVID-19 Cases on the Diamond Princess Cruise Ship and Ethical Considerations: A Report From Japan. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2020, 14, 506–513. [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.; et al. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994, 47, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, L.R.; E.L. Peterson, and N. Breslau, Graphing survival curve estimates for time-dependent covariates. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2002, 11, 68–74. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; et al. The influence of immortal time bias in observational studies examining associations of antifibrotic therapy with survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A simulation study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1157706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suissa, S. and S. Dell'Aniello, Time-related biases in pharmacoepidemiology. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2020, 29, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashan, M.R.; et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of COVID-19 outbreaks in aged care facilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 33, 100771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, B.V.; et al. Is the SARS CoV-2 Omicron Variant Deadlier and More Transmissible Than Delta Variant? Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022. 19(8). available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35457468.

-

Severity of disease associated with Omicron variant as compared with Delta variant in hospitalized patients with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. 2022. available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240051829?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Guillermo V. Sanchez, G.V.; Biedron, C.; Fink, L.R.; Hatfield,K.M. , Polistico, J.M.F.; Meyer,M.P.;Noe,R.S. et al, Initial and Repeated Point Prevalence Surveys to Inform SARS-CoV-2 Infection Prevention in 26 Skilled Nursing Facilities — Detroit, Michigan, March–May 2020, in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). 2020, Center for Disease Control and Prevention. p. 882-886. available at ttps://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6927e1.htm?s_cid=mm6927e1_w.

- Madewell, Z.J.; et al. Rapid review and meta-analysis of serial intervals for SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron variants. BMC Infect Dis 2023, 23, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; et al. Assessing changes in incubation period, serial interval, and generation time of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 2023, 21, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksuzyan, A.; et al. Men: good health and high mortality. Sex differences in health and aging. Aging Clin Exp Res 2008, 20, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimmins, E.M.; et al. Differences between Men and Women in Mortality and the Health Dimensions of the Morbidity Process. Clin Chem 2019, 65, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luy, M. and K. Gast, Do women live longer or do men die earlier? Reflections on the causes of sex differences in life expectancy. Gerontology 2014, 60, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijls, B.G.; et al. Demographic risk factors for COVID-19 infection, severity, ICU admission and death: a meta-analysis of 59 studies. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, D.; et al. Potential Risk Factors to COVID-19 Severity: Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 Delta- and Omicron-Dominant Periods. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: recent progress and future perspectives. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chidambaram, P.R.; R and Neuman,T.; Key Questions About Nursing Home Cases, Deaths, and Vaccinations as Omicron Spreads in the United States, in Coronavirus (COVID-19). 2022. available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/73/wr/mm7312a5.htm.

- Link-Gelles, R.; Rowley,E.A.K.. DeSilva,M.B.; Dascomb,K.; Irving,S.A.; Klein,N.P. et al. Interim Effectiveness of Updated 2023–2024 (Monovalent XBB.1.5) COVID-19 Vaccines Against COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Among Adults Aged ≥18 Years with Immunocompromising Conditions — VISION Network, September 2023–February 2024, M.a.M.W.R. (MMWR), Editor. 2024. p. 271–276. available at https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/29/6/23-0130_article.

- Bloomfield, L.E. ; Ngeh,S.;Cadby,G.; Hutcheon,K. and Effle.P.V.; SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Effectiveness against Omicron Variant in Infection-Naive Population, Australia, 2022. 2023, Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Chen, L.K.; et al. Predicting mortality of older residents in long-term care facilities: comorbidity or care problems? J Am Med Dir Assoc 2010, 11, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checovich, M.M.; et al. Evaluation of Viruses Associated With Acute Respiratory Infections in Long-Term Care Facilities Using a Novel Method: Wisconsin, 2016‒2019. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020, 21, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Influenza 2019/20 season, Japan, in Infectious Agents Surveillance Report. 2020, National Institute of Infectious Diseases. p. p191-193: November 2020.

- Otsuka, M.; et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection notification trends and interpretation of the reported case data, 2018-2021, Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis, 2024.

- Sakamoto, H.; M. Ishikane, and P. Ueda, Seasonal Influenza Activity During the SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak in Japan. JAMA 2020, 323, 1969–1971. [CrossRef]

- Ujiie, M.; et al. Resurgence of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infections during COVID-19 Pandemic, Tokyo, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis 2021, 27, 2969–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, Y.; et al. Resurgence of human metapneumovirus infection and influenza after three seasons of inactivity in the post-COVID-19 era in Hokkaido, Japan, 2022-2023. J Med Virol 2023, 95, e29299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).