1. Introduction

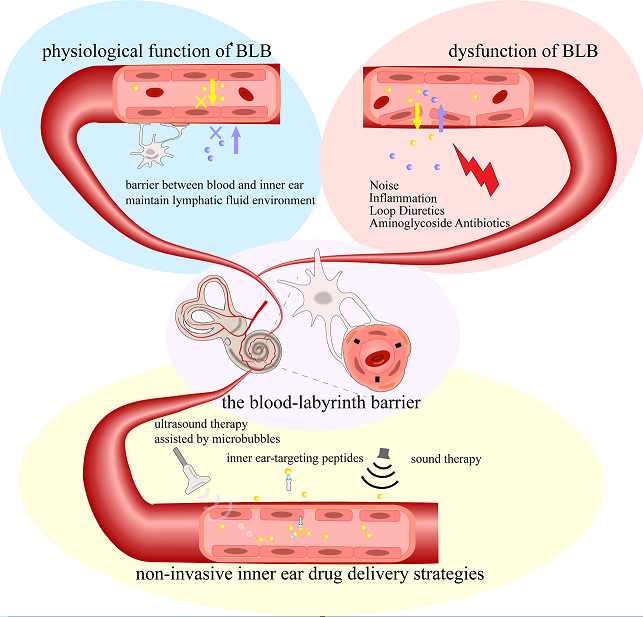

The blood-labyrinth barrier (BLB) is a selective permeability system that separates the blood circulation from the fluids of the inner ear, maintaining a distinct environment within the inner ear labyrinth.

The inner ear is located deeply within the temporal bone. Due to the fine anatomical structure, the BLB was discovered nearly a century later than the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The discovery of the BLB thanks to the in-depth studies on inner ear physiology, especially the studies of vascular distribution within the inner ear. In the 1970s, while investigating the origin of perilymph in the cochlea, scientists observed that the chemical composition of inner ear lymphatic fluid differed significantly from both blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)[

1]. The composition of perilymph resembled blood ultrafiltrate rather than CSF, suggesting the existence of a special barrier, just like the BBB, that protects the microenvironment of the inner ear. In 1974, Klaus Jahnke, by observing the permeability of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) from the cochlear vascular endothelium to inner ear fluid, proposed the existence of a blood-perilymph barrier [

2]. In 1980, this concept was further morphologically defined through freeze-fracture electron microscopy [

3]. Further studies revealed a more complex blood-endolymph barrier, formed by the epithelial marginal cells of the stria vascularis and endothelial cells, sometimes referred to as the blood-strial barrier [

4,

5]. In 1988, S. K. Juhn coined the term blood-labyrinth barrier to encompass these barrier systems between inner ear fluids and blood, identifying the stria vascularis as the main structure executing the barrier functions [

6].

BLB is crucial for maintaining the relative stability of the ion concentration and the endocochlear potential (EP) within the inner ear lymphatic fluid. The ion concentration gradient between the endolymph and perilymph and the EP provides the physiological basis for the mechano-electrical transduction process in cochlear hair cells, which is a fundamental process to hearing [

7]. Therefore, BLB dysfunction may be closely related to hearing loss caused by various factors such as noise [

8], aging [

9], genetic mutations [

10], and inner ear inflammation [

11]. The BLB also presents a challenge to drug delivery and the artificial intervention of inner ear homeostasis by blocking most drugs and molecules from entering the inner ear [

12]. The primary objective of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the blood-labyrinth barrier (BLB) and its critical role in the pathological mechanisms underlying hearing loss. We specifically emphasize several recently developed innovative approaches that demonstrate potential for non-invasive BLB penetration through strategic utilization of its intrinsic biological properties.

2. Stria Vascularis and Blood-Labyrinth Barrier

The inner ear barrier systems, or the blood-labyrinth barriers, can be divided into five separate barriers. Two semipermeable boundaries within the cochlear duct, the Reissner’s membrane and the basilar membrane, divide the cochlear duct into three distinct fluid-filled chambers, separating the inner ear lymphatic fluid into endolymph and perilymph, each with markedly different compositions. The inner ear barrier system can be thus subdivided into the blood-perilymph barrier, blood-endolymph barrier, and the endo-perilymph barrier based on the pathways substances take from the blood into the inner ear lymphatic fluid [

6].

Broadly speaking, the so-called blood-labyrinth barrier refers to the entire barrier system that separates the cochlear fluids from other fluids like blood and cerebrospinal fluid(CSF) [

12,

13,

14,

15], especially for those early studies in the field [

3,

4,

5,

16,

17]. Other terms such as intra-ear fluid barrier, labyrinth membranous barriers and membranous labyrinth barriers are also used to refer to the barrier systems in the inner ear.

It is important to understand that this term(blood-labyrinth barrier) broadly includes all anatomical barrier structures that separate cochlear (and vestibular) fluids from the blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and tissue fluid. It does not specifically refer to any particular location or barrier, nor does it distinguish between different capillaries, tissues (such as the stria vascularis, neurons, and organ of Corti), and inner ear fluids (endolymph, perilymph, strial fluid) within the cochlea.

In some recent references, however, this term is specifically used to describe the intrastrial fluid-blood barrier (or blood-endolymph barrier) within the stria vascularis [

18,

19,

20], which highlights the unique role of the stria vascularis in separating endolymph fluid from blood and generating EP.

In this review, the term “blood-labyrinth barrier” is used in a broader sense, as it encompasses a more comprehensive concept of separating the inner ear fluids from blood and CSF. We also emphasize the function of the SV, as it covers the intrastrial fluid-blood barrier and plays an important role in generating EP and maintaining cochlear ion homeostasis.

2.1. Cell Components of BLB

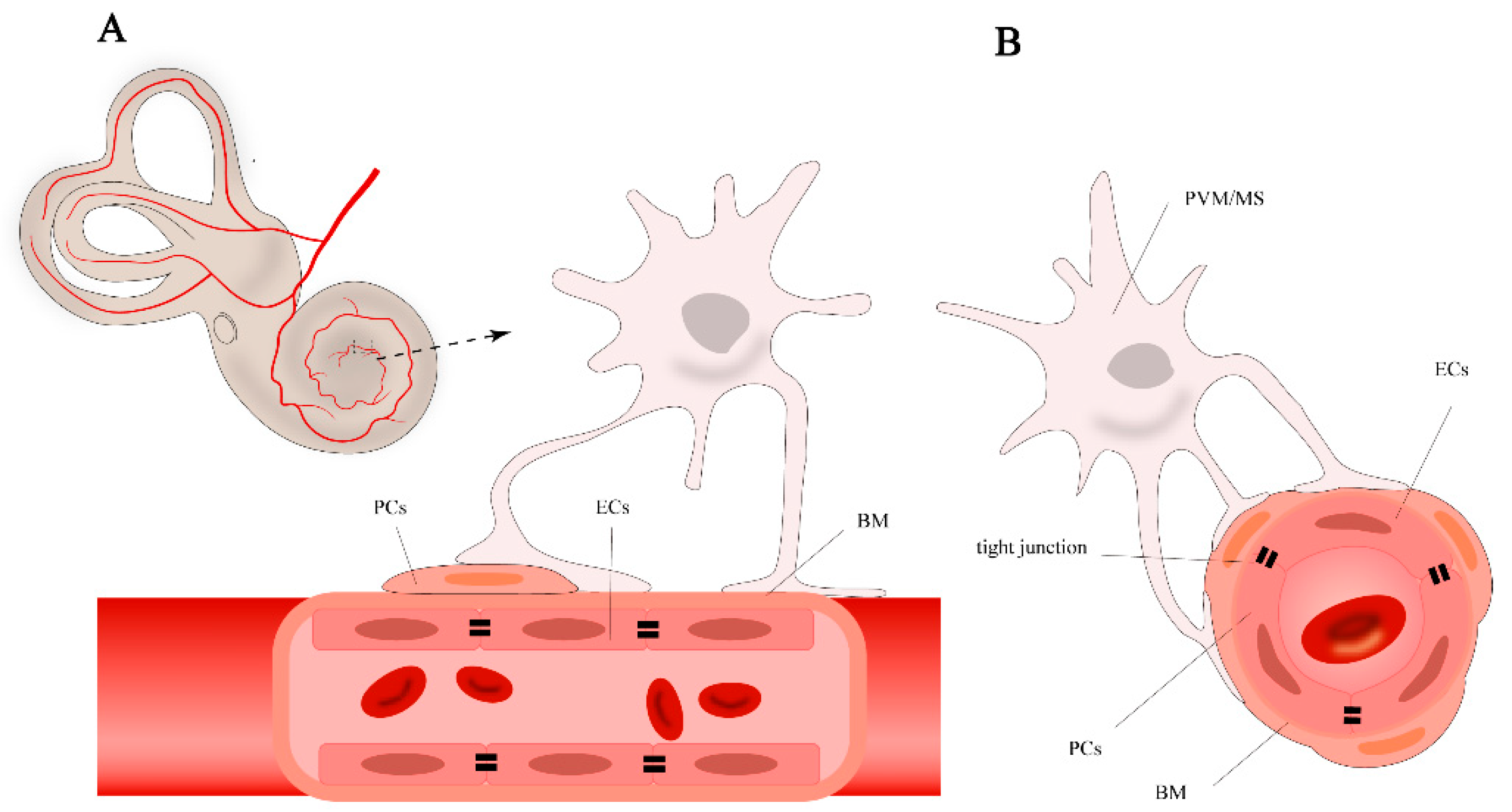

The normal function of BLB relies on the integrity of the stria vascularis and the spiral ligament. The stria vascularis consists of marginal cells, intermediate cells, and basal cells (

Figure 1). The capillary network traversing the intermediate cell layer includes endothelial cells(ECs), pericytes(PCs), and perivascular resident macrophage-like melanocytes (PVM/Ms). Each of these cells has unique functions, working together to form the barrier function of the stria vascularis. Understanding these cells’ roles is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the BLB’s function.

The basic structure of BLB is composed of the continuous ECs and their basement membrane (BM) of the capillaries in the stria vascularis and spiral ligament of the cochlear lateral wall, PCs, PVM/Ms, along with specific junctional structures between these cells [

21]. This structure pattern is rather similar to the the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and inner blood-retinal barrier (BRB)[

22,

23]. Endothelial cells connect through tight junctions, surrounded by the capillary basement membrane. PCs, around the capillaries, adhere to the surface of endothelial cells with their cell bodies and extend numerous processes wrapping around the capillaries, embedding into the basement membrane [

24]. PVM/Ms are located in the intermediate cell layer, with dendritic cell bodies extending processes that attach to marginal cells on one side and to PCs and endothelial cells’ basement membrane on the other, regulating barrier integrity and permeability [

25].

2.2. Cells in Stria Vascularis

The stria vascularis is primarily composed of marginal cells (MC), intermediate cells (IC), and basal cells (BC) [

26]. These cells are organized in layers, with the marginal cells closest to the endolymph, followed by the intermediate and basal cell layers. Tight junctions between marginal cells and basal cells create a relatively closed fluid environment within the stria vascularis [

11,

27,

28], known as the intrastrial space, containing intrastrial fluid. Intermediate cells, located between marginal and basal cells, extend numerous cell processes with complex folding structures interweaving, with capillaries traversing the intermediate cell layer [

29].

Marginal cells directly face the cochlear scala media, with one side in contact with the endolymph and the other extending into the intrastrial space, where they send projections toward the intermediate cells [

30]. Marginal cells are closely related to the unique high K

+ environment of the endolymph. The projections extending toward the intermediate cells are rich in mitochondria, providing the necessary energy for the active uptake of K

+ from the intrastrial space via Na

+-K

+-ATPase and Na

+-K

+-2Cl

- cotransporters [

31]. The marginal cells are connected by tight junctions on the side in contact with the endolymph, thereby separating the intrastrial space from the endolymph. Additionally, the active transcellular transport processes of marginal cells form the basis for selective substance entry into the endolymph.

The intermediate cell layer is located in the perivascular space between the marginal cell layer and the basal cell layer. This layer contains many components between the marginal cell layer and the basal cell layer, including capillary ECs, PCs, and PVM/Ms. The origin of ICs is rather complex, as both melanoblast- and Schwann cell precursor-derived ICs can be found during the embryonic stage [

32]. The function of intermediate cells was believed to be the production of melanin granules [

33] and participation in potassium ion transport [

34]. Further studies reveal that these ICs exhibit characteristics of both macrophages and melanocytes. Therefor the intermediate cells are also referred to as perivascular-resident macrophage-like melanocytes (PVM/Ms).

Basal cells are epithelial-like, elongated in shape, and connected to each other by tight junctions, forming a cohesive unit at the base of the stria vascularis, which separates the stria vascularis from the spiral ligament [

28,

35].

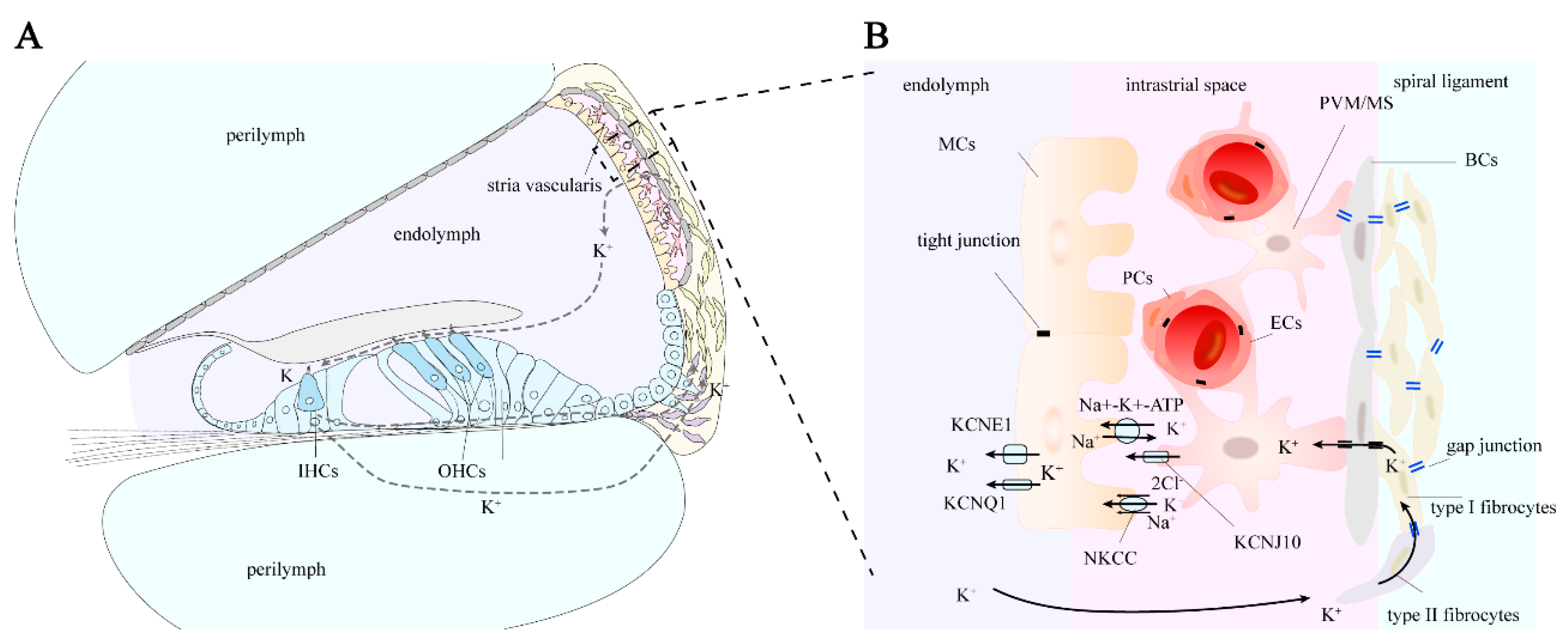

3. Stria Vascularis in K+ Circulation and EP Generation

As a selectively permeable physiological barrier, the BLB’s primary physiological significance lies in maintaining the relatively independent fluid environment within the membranous labyrinth, conducting ion transport to maintain normal cochlear EP (

Figure 2), protecting cochlear cells such as hair cells from external damage, and ensuring normal physiological function.

The endolymph in the cochlear scala media exhibits a distinct ionic composition, with high potassium and low sodium levels, comparable to intracellular fluid. The high potassium environment in the endolymph and the high endocochlear potential (EP) between the endolymph and perilymph are essential for the mechanotransduction process in hair cells. The potassium concentration in endolymph is approximately 140 mM, and the EP is about +80 to +100 mV, varying with experiment results and species [

36,

37].

When sound waves cause the basilar membrane to vibrate, stereocilia of hair cells bend, opening mechanically-gated ion channels at the tips of the stereocilia, allowing potassium and calcium ions from the endolymph to enter the hair cells [

38]. This potassium influx generates an electrical signal, initiating the conversion of mechanical sound waves into electrical nerve impulses transmitted to the brain. Subsequently, potassium ions exit the hair cells and enter the perilymph or are absorbed by supporting cells, which transport them to the stria vascularis in the lateral wall of the cochlea. Then, the potassium ions are reabsorbed and secreted back into the endolymph, forming the potassium ion cycle within the cochlea [

39].

The coordinated activity of these ion channels and cell gap junction ensures the efficient transport of potassium ions into the endolymph , maintaining the high potassium concentration and EP. Additionally, the stria vascularis forms a barrier to prevent the entry of large molecules and potentially harmful substances from the blood into the endolymph, protecting the cochlear environment and ensuring normal hearing function.

3.1. Pathway of Potassium Ion Circulation

After potassium ions (K

+) are expelled from the basal-lateral part of hair cells via the KCNQ4 potassium ion channel, they are taken up by surrounding supporting cells [

39]. Through the epithelial cell gap junction system, K

+ is transported to the root cells at the stria vascularis via gap junction proteins in Deiters cells, Hensen cells, and Claudius cells [

31]. The root cells then secrete K

+ into the extracellular matrix [

40]. Potassium ions can also diffuse through the perilymph of the scala vestibuli and scala tympani to reach the spiral ligament. In the spiral ligament, some types of fibrocytes reabsorb K

+ from the extracellular matrix and transfer it to type I fibrocytes [

41]. Through gap junction proteins in the connective tissue cell gap junction system, K

+ is transported across basal cells to intermediate cells, and then secreted into the endolymph by marginal cells [

31].

3.2. Generation of Endolymphatic Potential

The stria vascularis in the lateral wall of the cochlea plays a role in generating and regulating the endocochlear potential (EP) by secreting potassium ions from the perilymph into the endolymph [

42]. The marginal cells of the stria vascularis are closely connected to the endolymph on one side and face the intermediate cells on the other. Tight junctions between marginal cells separate the stria vascularis lumen from the endolymph of the scala media. The apical membrane of the marginal cells, which faces the endolymph, contains K

+ channels (KCNQ1 and KCNE1 channels). On the side facing the intermediate cells, the marginal cells extend numerous enlarged cellular protrusions into the layer of intermediate cells, which are rich in Na

+-K

+-ATPase and Na

+-K

+-2Cl

- cotransporters (NKCC) to absorb K

+ ions from the intrastrial space [

43]. The intermediate cells transfer K

+ into the intrastrial space via the Kir4.1 channel (an inward-rectifying potassium ion channel encoded by the KCNJ10 gene, also known as the KCNJ10 channel)[

7].

The entire process of endolymphatic potential generation is as follows [

31,

44]: A significant influx of potassium ions through the Kir4.1 channel on the membrane of intermediate cells flows into the intrastrial space. Marginal cells actively uptake K

+ from the intrastrial space through Na

+-K

+-ATPase and NKCC, then release the cytoplasmic potassium into the scala media via the apical KCNQ1 and KCNE1 channels. The Kir4.1 channel in intermediate cells plays a key role in EP formation, while marginal cells contribute indirectly.

4. Selective Permeability of the Blood-Labyrinth Barrier

Cochlear fluid can be divided into endolymph and perilymph, the permeability of a certain substance differs between these two fluids. In fact, the research of permeability of specific substance are very limited in BLB. In addition, many studies focusing on the permeability of the BLB only test the concentration of substances in perilymph [

2,

4,

5]. Using the tracer ion trimethylphenylammonium (TMPA)(181 g/mol) as an indicator in perilymph, the BLB shows lower permeability compared to the BBB [

45]. The selective permeability of the blood barrier in stria vascularis is determined by the specific structure and function of capillary ECs, PCs, PVM/MS and base membrane [

21].

Osmotic agents such as glycerol(92Da) and urea(60 Da) can pass through the barrier and enter into perilymph, while mannitol(182 Da) can not [

4]. Even after extensive noise exposure, the mannitol concentration shows no difference compared to the control group [

46].

Fluorescent tracers with relatively large molecular mass, such as cadaverine Alexa Fluor-555(950 Da), BSA-Alexa Fluor-555(66 kDa) and and IgG Alexa 568(200 kDa) can hardly penetrate through BLB, but after disruption of PVM/Ms, they can accumulate in the lateral wall of cochlear [

25].

Ototoxic substances such as kanamycin enter the cochlear lymph fluid very slowly, with peak concentrations much lower than those in serum, yet they accumulate in specific cochlear cells and exert ototoxic effects [

5,

47]. Furosemide(330 Da) can also enter perilymph, with a relatively constant concentration before full recovery [

4]. Similarly, after intravenous injection of ³H-marked taurine (125 Da), it can be detected in perilymph 1 and 2 hours later [

48].

Additionally, anionic sites have been reported on the BLB that act as an electrical charge barrier [

49], which is associated with the selective transport of macromolecules. Hence, the cationic tracer polyethyleneimine (PEI) has been used to test the integrity of this charge barrier [

49,

50,

51]. Ototoxic substances such as cisplatin and aminoglycosides are positively charged, which could combine with anionic sites and cause adverse effects.

As a result of BLB, systemic drug administration often fails to penetrate the inner ear or exhibits significant delays due to the selective permeability of the BLB, leading to low drug concentrations in the inner ear while causing significant off-target effects elsewhere.

The permeability of the BLB varies under various conditions, including inflammation, noise exposure, and the disruption of BLB components. However, existing research on permeability is quite limited. Understanding the nature of BLB permeability under different circumstances may contribute to the discovery of suitable drugs that can pass through the BLB.

5. Inner Ear as a Former Assumed Immunoprivileged Organ

The inner ear was once considered as one of immunoprivileged organs since the presence of BLB is similar to the BBB and BRB, which could restrict the entry of blood-borne immune effector cells and molecules [

52], thereby theoretically reducing immune-mediated damage. The rather low immunoglobulin titer (1/1000 in serum) in perilymph seemed to support this assumption [

53,

54]. However, researchers have found that various stimulus, such as inflammation, noise exposure and aminoglycoside drugs, can lead to widespread infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages into the inner ear [

55].

Compared to brain tissue, the inner ear is more sensitive in its response to antigens. When the antigen is placed into the inner ear of animals that have been pre-sensitized via systemic routes, the resulting immune response leads to an increased perilymphatic antibody titer, local antibody production, as well as lymphocyte infiltration and cochlear inflammatory damage [

53,

56]. Further studies reveal that macrophages in cochlear and PVM/Ms cells in the stria vascularis function as antigen-presenting cells and are associated with cochlear inflammatory responses [

57]. The distribution of cochlear macrophages is reported to be approximately 62% in neural tissues and 36% in the spiral limbus and spiral ligament [

58]. Following noise exposure, there is a marked increase in CD45+ cells, which are derived from the monocyte/macrophage lineage [

59]. These cells accumulate in the spiral ligament and spiral limbus and perform a phagocytic function in cochlea. PVM/Ms cells in the stria vascularis, on the other hand, regulate barrier permeability when exposed to noise [

19]. Besides, immune cells (primarily monocytes) in circulation can enter the cochlea and infiltrate when exposed to acute damage.[

60]. Therefore, the significant immune response of the cochlea to external stimuli has led to the reconsideration of the inner ear as an immune-privileged organ.

However, immune cells are rarely reported in the organ of Corti, even after acoustic trauma and inflammation stimulation [

58,

59,

61]. Even phagocytic cells found in the Corti region appeared only later after noise exposure (on the fifth day) and were located in the tunnel of Corti and the region of the outer hair cells, without causing damage to the cell structure of inner hair cells and supporting cells [

62]. It is reasonable to assume that the organ of Corti, the most delicately organized part of the inner ear, is endowed with immune privilege. The main function of the organ of Corti is to convert mechanical stimuli into detectable action potentials through mechanotransduction channels, which is a core process in sound perception [

63]. Immune cell infiltration, if it occurs, could disrupt the delicate microenvironment and compromise the functional integrity of sensory cells. The lack of a vascular system and the presence of a connective tissue cell gap junction system may also serve as protective factors against potential disruption of the endolymph microenvironment.

6. Pathological Mechanisms of Blood-Labyrinth Barrier Dysfunction

Many pathogenic factors can disrupt the function of BLB, leading to sensorineural hearing loss. The resulting types of hearing impairment include, but are not limited to, drug-induced hearing loss [

64], noise-induced hearing loss [

65], genetic hearing loss [

66], and inner ear immune inflammation [

57]. It is important to note that these pathological factors do not solely cause damage to the BLB, in fact, damage to the BLB may account for only a small portion of the causes of hearing loss. Drug-induced hearing loss ototoxic drugs, like other drugs, are limited in lymphatic fluid because of BLB, their peak concentration and time to peak in the inner ear labyrinth are typically lower than those in serum [

5]. However, ototoxic drugs can enter the labyrinth and damage inner ear cells, particularly hair cells, through various pathways, causing ototoxic effects. Long-term, high-dose administration can also lead to drug accumulation, which surpass the toxic levels. Some drugs like loop diuretics can further exacerbate the ototoxicity of other drugs when combined using.

6.1. Loop Diuretics

Loop diuretics, such as furosemide and ethacrynic acid, are typically used to target the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle in the kidney [

67]. By blocking the Na

+-K

+-2Cl

- cotransporter, they inhibit the reabsorption of Na

+, K

+, and Cl

-, rapidly increasing urine output. The marginal cells of the mammalian stria vascularis also express the Na

+-K

+-2Cl

- cotransporter, which is considered the target for loop diuretics causing ototoxicity [

68]. Injection of ethacrynic acid can induce significant microcirculatory disturbances in the cochlear lateral wall, including stria vascularis edema, thickening, and cystic changes, potentially leading to the loss of the Na

+ and K

+ concentration gradient between the endolymph and perilymph, resulting in the disappearance of EP and temporary hearing loss [

68]. These drugs temporarily block blood flow to the lateral wall, leading to hypoxia in capillary ECs, resulting in pathological changes such as stria vascularis edema, enlargement of intercellular spaces, and significant reductions in endolymphatic potential. Potent loop diuretics can lead to temporary hearing loss, which usually recovers over time without causing permanent hearing damage.

6.2. Cisplatin

Cisplatin-induced cochlear damage primarily affects hair cells but also directly impairs the function of stria vascularis cells, leading to dysfunction and a decrease in endolymphatic potential [

69]. The ototoxic mechanism of cisplatin involves the production of reactive oxygen species, activation of intrinsic apoptotic pathways, mitochondrial dysfunction and involvement of inflammatory cytokines [

70]. In rats treated with cisplatin, strong expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) is observed in the cochlear spiral ligament and stria vascularis [

71]. Cisplatin activates potassium channels in marginal cells of the stria vascularis, leading to the efflux of intracellular potassium ions, altering ion concentration and osmotic pressure within cells, which in turn activates apoptotic enzymes, inducing cell death. Hydration of cisplatin can neutralize the negative charge barrier formed by certain proteins on the basement membrane of capillaries, allowing negatively charged substances to cross the ECs more easily [

69]. Cisplatin also reduces ZO-1, cx26 and cx43 expression on stria vascularis cells and leading to damage to the BLB’s charge barrier, resulting in the reduction of EP [

72]. Cisplatin can also damage BLB’s PCs by reducing viability and increasing toxic effects, which can be mitigated by dexamethasone and enhanced proliferation with PDGF-BB treatment [

73].

6.3. Aminoglycoside Antibiotics

Aminoglycoside antibiotics are a series of classic ototoxic drugs, these antibiotics primarily cause damage to the cochlea and/or vestibular system [

74]. Research on the direct effects of aminoglycoside antibiotics on the BLB is still insufficient. In mice subjected to prolonged injections of gentamicin, thinning of the stria vascularis, the presence of lipid structures within marginal cells, nuclear deformation, and swelling of the endoplasmic reticulum in intermediate cells have been observed, along with the formation of lysosome-like bodies [

75]. Aminoglycosides may reach the cochlea by passing through capillaries to the marginal cells of the stria vascularis, then into the lymphatic fluid, and finally being absorbed by hair cells [

76]. Fluorescently tagged gentamicin have shown that the concentration of gentamicin is higher in marginal cells than in basal and intermediate cells. It is generally believed that the primary target cells for aminoglycoside-induced ototoxic damage are the outer hair cells of the cochlea, with damage progressing from the base to the apex of the cochlea [

74]. The mechanical transduction channels at the apex of hair cells, such as transient receptor potential channels (TRPA1), are considered pathways through which gentamicin enters the hair cells [

77].

Due to the presence of the BLB, aminoglycoside antibiotics reach peak concentrations in inner ear fluids much more slowly than those in the blood, leading to two completely different outcomes regarding the combined use of aminoglycoside antibiotics and loop diuretics. When gentamicin concentration in the blood is higher than in the lymphatic fluid, using ethacrynic acid to disrupt the BLB can accelerate the entry of ototoxic drugs into the cochlea, rapidly reaching concentrations that damage hair cells [

78]. Conversely, when the gentamicin concentration in the blood is lower than in the lymphatic fluid, using ethacrynic acid to disrupt the BLB helps promote the excretion of ototoxic drugs from the inner ear fluid, thereby reducing their continuous damage to hair cells [

78].

In addition to the drugs mentioned above, animal experiments have shown that chronic salicylate poisoning can lead to a decrease of blood flow in the stria vascularis [

79]; large doses of quinine can cause atrophy and degeneration of the stria vascularis [

80]. These findings suggest that various drugs can accumulate in the inner ear and damage the stria vascularis, thereby affecting hearing health. Understanding the underlying mechanisms may help develop protective strategies, making the use of these ototoxic drugs safer.

6.4. Genetic Mutations

Genetic mutations affecting proteins involved in the BLB can lead to inherited forms of hearing loss. For example, mutations in genes encoding tight junction proteins [

81,

82], ion channels [

7,

83], or other structural components of the BLB can result in a compromised barrier function, including Norrie Disease [

84], Alport syndrome [

85] and mutant of Light (Blt) [

86], white spotting (Ws) locus [

87], and estrogen-related receptor β (NR3B2)[

88]. The disruption of BLB may allow the passage of potentially harmful substances from blood into the inner ear fluids, leading to progressive hearing loss. Mutations in genes encoding gap junction and ion transport proteins associated with the stria vascularis in the cochlea can weaken or impair BLB function. The gap junction proteins present in the cochlea include connexin 26 (encoded by the GJB2 gene)[

82], connexin 30 (encoded by the GJB6 gene)[

81] and connexin 43 (encoded by the GJA1 gene)[

89]. These proteins are prominently expressed in the basal and intermediate cells of the stria vascularis, therefore, stria vascularis dysfunction is one of the mechanisms leading to genetic hearing loss caused [

90]. Mutations of the ion channel proteins KCNQ1 and KCNE1 in marginal cells can cause Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome (JLNS) related deafness, accompanied by severe arrhythmias [

91]. Mice with Kcnq1 or Kcne1 deletions or spontaneous Kcel1 mutations exhibit significant hearing loss [

92].

6.5. Acoustic Trauma

The mechanisms by which acoustic trauma alters BLB permeability are rather complex. Studies have shown that noise exposure can induce microcirculatory changes in the inner ear, including vasoconstriction, reduced blood flow velocity, increased blood viscosity, reduced local blood perfusion, capillary endothelial cell swelling, and increased permeability [

16,

93,

94]. Additionally, noise exposure leads to structural and quantitative changes instria vascularis cells, accompanied by upregulation or downregulation of various cytokines, decreased expression of junction proteins, and reduced energy metabolism capacity [

19,

82,

95,

96]. After noise exposure, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) are upregulated, inducing pericyte proliferation in the stria vascularis [

97]. The downregulation of PEDF secretion by PVM/Ms decreases the synthesis of tight junction-related proteins (ZO-1, VE-cadherin) between ECs [

19,

25]. Furthermore, the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)-2 and -9 plays a role in regulating tight junction proteins, thereby influencing the integrity and permeability of the BLB [

98]. Prolonged noise exposure can also lead to the shrinking of the stria vascularis, degeneration of spiral ligament fibrocytes, and a reduction in EP [

99]. Noise exposure damages both the structure and cells of the cochlea, particularly affecting inner and outer hair cells. Compared to noise-induced decreases in endolymphatic potential, the direct damage to hair cells caused by noise exposure has a more immediate and significant impact on hearing loss.

6.6. Inflammatory Responses

Inflammatory responses can significantly impact BLB function. Inflammation reaction in the inner ear can be triggered by infections, autoimmune reactions, or acustic trauma [

57,

61,

100]. This leads to the release of inflammatory cytokines and other mediators that can compromise the integrity of the BLB. Increased permeability allows immune cells and other potentially harmful substances to infiltrate the inner ear fluids, leading to damage of cochlear cells and subsequent hearing loss [

101].

The specific mechanisms by which inflammation increases BLB permeability are not yet fully understood. Generally, inflammatory factors can directly damage the vascular endothelium, leading to increased permeability and acting as inflammatory mediators to further promote the inflammatory response. Animal experiments have shown that directly injecting inflammatory factors and LPS into the inner ear through the round window membrane increases BLB permeability and disrupts the balance of the endolymph [

100]. After injecting LPS into the middle ear, the permeability of blood vessels significantly increased, along with the activation of PVMs [

102]. LPS-induced otitis media can lead to downregulation of connexin26 expression in the spiral ligament, thereby affecting the permeability of the inner ear BLB [

103]. However, in inflammation induced by intraperitoneal injection of LPS in mice, despite the accumulation of macrophages in the spiral ligament, no decrease in endocochlear potential (EP) or hearing loss was observed [

104]. Additionally, during viral or bacterial infections, the increase in serum antiphospholipid antibodies may also lead to BLB dysfunction [

105].

7. In Vivo and In Vitro Models for Studying the Blood-Labyrinth Barrier

7.1. In vivo Models

Animal models are indispensable for studying the BLB and its role in inner ear function. Rodents, particularly mice and rats, are commonly employed due to their accessibility and relative physiological similarities to the human inner ear. Furthermore, they provide a valuable platform for testing potential therapeutic interventions, facilitating a deeper understanding of the physiological and pathological mechanisms underlying the BLB. A novel “thin” or “open” otic capsule vessel-window technique has been established in a mouse model, enabling the study of alterations in cochlear blood flow [

106]. In inflammation process, PVM/Ms help maintain barrier integrity and trigger local inflammation after injecting bacterial LPS into the middle ear [

107]. Further in vivo studies revealed that LPS disrupts the BLB by reducing the levels of occludin, ZO-1, and VE-cadherin between ECs, while simultaneously elevating the expression of MMP9[

100,

102]. In the aging process, the structure and cell component of BLB changes, with decreased capillary density, reduced numbers of PCs and PVM/Ms [

108]. Acoustic trauma decreases capillary density and increases matrix protein deposition around PCs, with a phenotypic change in some PCs from negative to positive for α-smooth muscle actin [

109]. This may explain the phenomenon of PCs migration following noise exposure, which is associated with the upregulation of platelet-derived growth factor beta (PDGF-BB)[

110].

7.2. In Vitro Models

In vitro models often use specific cell types, typically ECs, to mimic the functions of barrier systems [

111]. Various cells including ECs, PCs and PVM/Ms that make up the BLB can be isolated and cultured in vitro to create culture-based two-dimensional(2D) and investigate interaction between different cells [

112]. In the LPS-induced in vitro infection model, the morphology and function of PCs and PVM/Ms change, thereby affecting barrier integrity [

100]. In a transwell co-culture system with ECs, PCs and/or PVM/Ms, Nhe6-knockout BLB-derived cell monolayers exhibited reduced electrical resistance and increased permeability [

113].

The new culture platforms, such as organoids, microfluidic systems, and organ-on-a-chip technologies, have been developed to better mimic the three-dimensional environment of the body. This is particularly important in the study of the neurovascular unit due to the complex interaction between neurons, glial and vascular cells [

114]. The research in BLB also benefits from such development. PCs and PVM/Ms are shown to be vital for supporting the integrity and organization of cochlear blood vessels by using three-dimensional(3D) culture models [

115]. Human BLB on a chip model are developed based on PCs and ECs isolated from post-mortem human tissue to mimic the integrity and permeability of BLB [

116]. Using this model, inflammatory factors such as TNF-α, IL-6, and LPS are tested to demonstrate their disruptive effects on the barrier. By reducing the expression levels of ZO-1 and OCL, TNF-α is confirmed to have the most significant disruptive effect on the endothelial monolayer [

117].

8. Current Inner Ear Drug Delivery Strategies

The presence of the BLB posts a challenge for the treatment of inner ear diseases with drugs. Due to the barrier function of the BLB, systemic administration of drugs often results in limited effectiveness for inner ear conditions [

118]. Even when drug concentrations in the bloodstream are high following systemic administration, the concentration within the target organs of the inner ear remains low. To achieve effective therapeutic concentrations in inner ear tissues, clinicians have to increase the systemic drug dosage, which can lead to off-target effects and adverse reactions. Finding efficient, safe, and non-invasive (or minimally invasive) drug delivery methods is a key focus in otological research [

12].

To overcome the barrier function of the BLB that limits the effectiveness of systemic treatments, traditional approaches often rely on local drug delivery methods, such as intratympanic or intracochlear administration [

118]. Intratympanic injection delivers drugs through the eardrum into the tympanic cavity, allowing them to diffuse through the round window membrane into the inner ear’s lymphatic fluid. This method has been used for over half a century in the treatment of Meniere’s syndrome [

119]. Although this method bypasses the BLB, it requires good contact between the drug and the round window membrane, and controlling the dosage is challenging [

120]. Intracochlear administration aims to inject drugs directly into the lymphatic fluid, providing a more direct approach compared to intratympanic delivery, with easier dosage control [

121]. However, this technique is surgically demanding, carries a high risk of trauma, and is primarily used in animal experiments, with limited clinical applications, particularly in gene therapy [

122]. While local delivery methods can bypass the BLB, they are not truly non-invasive. Intratympanic administration is relatively mature but still requires eardrum penetration, and dosage precision remains an issue. Intracochlear injection is rarely used clinically due to the high surgical requirements. Therefore, researchers are also exploring the intrinsic properties of the BLB itself, seeking to develop drugs and drug carriers that can penetrate the BLB following systemic administration.

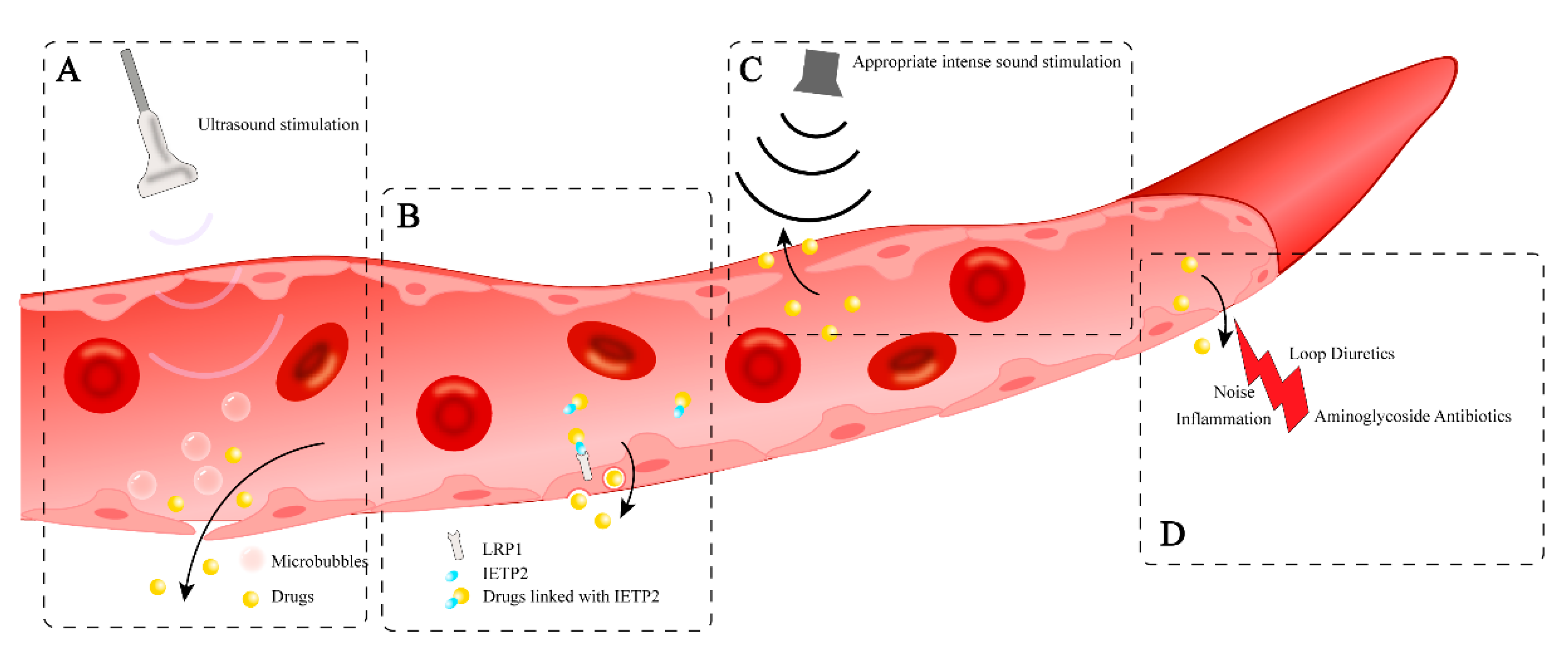

9. Innovative Approaches to Penetrate the BLB

Under certain circumstances, the permeability of BLB changes, creating an opportunity to transport drugs through systemic injection that would initially be unable to pass through (

Figure 3). Proteins expressed on the surface of BLB cells may also serve as potential targets for therapeutic drug delivery routes. For instance, ototoxic aminoglycosides can cross BLB through marginal cells, suggesting that finding other drug carriers with similar properties might be applicable in drug development [

76].

9.1. Drug-Induced Permeability Change of BLB

The most classic circumstance is the aminoglycoside antibotics. Aminoglycoside antibiotics reach peak concentrations in inner ear fluids much more slowly than those in the blood, leading to two completely different outcomes regarding the combined use of aminoglycoside antibiotics and loop diuretics. When gentamicin concentration in the blood is higher than in the lymphatic fluid, using ethacrynic acid to disrupt the BLB can accelerate the entry of ototoxic drugs into the cochlea, rapidly reaching concentrations that damage hair cells [

78]. Conversely, when the gentamicin concentration in the blood is lower than in the lymphatic fluid, using ethacrynic acid to disrupt the BLB helps promote the excretion of ototoxic drugs from the inner ear fluid, thereby reducing their continuous damage to hair cells [

78]. Similar strategy can be used in other drugs that initially could not penetrate the blood-labyrinth barrier.

9.2. Ultrasound Therapy Assisted by Microbubbles

An innovative therapeutic approach using sound, specifically low-pressure pulsed ultrasound assisted by microbubbles (USMB), aims to open the BLB [[

127]. When microbubbles are combined with ultrasound, the expression of tight junction proteins like ZO-1 and occludin is reduced, allowing for the effective delivery of intravenous drugs such as hydrophilic dexamethasone sodium phosphate (DSP) into the cochlea [

127] (

Figure 3a). This method has been used and clinically assessed in research related to the BBB [

128,

129], but its application to the BLB is still in the initial stage(

Figure 3a).

9.3. Inner Ear-Targeting Peptides

In the BBB, LRP1 targeting has been achieved by encapsulating IgG antibodies in polymers modified with the peptide Angiopep-2 and delivering them to the central nervous system of mice [

123]. Although it is unclear whether BLB can transport drugs via vesicular transport, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1), which is highly expressed at the apex of the stria vascularis and is similar in structure to BBB’s LRP1, indicates the potential for macromolecules to cross the BLB through vesicular transport. This approach has been applied to drug development targeting the BLB. Researchers have synthesized LRP1-specific binding ligands—inner ear targeting peptide 2 (IETP2)—and linked small moldecuale compounds to these peptides to achieve targeted drug delivery to the inner ear [

14]. These compounds conjugated with IETP2 were successfully transported into the cochlea, demonstrating the potential of this drug delivery strategy(

Figure 3b).

9.4. Sound Therapy

In specific circumstances, mild stimulation of the cochlea does not cause permanent damage; instead, it may enhance the cochlea’s resistance to stronger stimuli that could lead to permanent damage [

124]. Exposing the cochlea to a sound that is non-damaging, which activates the ear’s protective mechanisms and increases its resilience to potential future permanent injuries [

125]. Sound conditioning therapy is proposed to increase BLB permeability under certain noise exposure condition, which make it easier for drugs to enter the cochlear through paracellular pathway [

126]. Specifically, high-intensity noise exposure can disrupt the structural integrity of the BLB, but under conditions of sustained sound stimulation at higher intensities without causing permanent damage (90 dB SPL, 8-16 kHz, 2 hours), it can controllably and temporarily (within 6 hours) increase the permeability of the BLB, promoting the paracellular entry of blood-borne drugs into the cochlea [

126](

Figure 3c). This provides a viable non-invasive adjunctive approach for inner ear treatment.

9.5. Route of Cerebrospinal Fluid Conduit

Given the connection between the cerebrospinal and inner ear fluids via the cochlear aqueduct, administration of drugs through the cerebrospinal fluid is feasible. The intracisternal injection of the Slc17A8 gene via an adeno-associated virus (AAV) has successfully restored hearing in deaf Slc17A8 knockout mice [

130]. However, this mode of delivery require high demands on the drug carrier, necessitating the development of carriers specifically designed for inner ear tissues, such as AAV2.8 and AAV-i.e.[

131].

During local inner ear inflammation, the permeability of the BLB increases, and some transporters are generally upregulated, which can enhance drug delivery to the inner ear [

100]. In such cases, systemic drug administration may become more effective for targeting inner ear organs. Exploring the mechanisms of BLB opening during inflammation could provide new insights for drug development(

Figure 3d).

However, even if drugs can be non-invasively delivered to the inner ear, achieving an effective distribution of their concentration within the inner ear remains highly challenging. After local drug administration, a gradient of drug concentration from the cochlear base to the apex can be detected, limiting the potential therapeutic effect on the cochlear apex [

118]. This phenomenon is also likely to occur when drugs are systemically delivered to the inner ear. In addition, the strength of the BLB may not be consistent across individuals. For those with existing inner ear diseases, their BLB may be more easily opened. Therefore, controlling the intensity of the method used to open the BLB (such as sound or ultrasound) is also a major challenge in research.

10. Strategies to Protect and Regulate Blood-Labyrinth Barrier Function

Up till now, effective drugs specifically targeting the dysfunction of BLB have not been developed yet. However, the normal functiuon of BLB need sufficient blood flow to support the high metabolism of stria vascularis

10.1. Gene Therapy

Due to the components of BLB is rather complex, gene therapy targeting the entire BLB is quite challenging. However, there are gene therapy strategies available for specific cells of BLB. Vascular endothelial growth factor-A165(VEGFA165) gene therapy shows promise in restoring stria vascularis PCs, improving blood supply, and reducing hearing loss in noise-exposed animals [

132]. After transfecting VEGFA165 into PCs using AAV and subsequently transplanting these PCs into the cochlea following acoustic trauma, both blood flow and PCs proliferation can be enhanced [

109]. In the JCR syndrome mouse model, Kcnq1 gene therapy effectively restores Kcnq1 expression in marginal cells and rescues the function of the stria vascularis [

92].

10.2. Rescue the Injured Cell of BLB

Cochlear fibrocytes in the lateral wall are essential for potassium ion recycling to the stria vascularis; hence, the degeneration or injury of these fibrocytes may result in hearing loss. [

133]. Since fibrocytes are believed to originate from mesenchymal cells, transplanting mesenchymal stem cells into the cochlea has the potential to differentiate into fibrocytes. Indeed, the transplantation of isolated bone-marrow-derived stem cells or hematopoietic stem cells into the cochlea has resulted in the expression of marker proteins characteristic of ion-transporting fibrocytes [

134]. The trial of transplanting mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) isolated from bone marrow into the cochlea has demonstrated therapeutic effects in rats with fibrocyte dysfunction.[

135]. After transplantation, the transplanted MSCs are detected in the spiral ligament area and express marker proteins specific to fibrocytes. PCs are also one target of cell transplantation therapy since they play poles in regulating blood flow and vascular permeability. After acoustic trauma, transplanting cochlear PCs from postnatal day 10 can relieve the loss of vascular density in stria vascularis [

109].

11. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The BLB serves as a critical structure in the maintenance of inner ear homeostasis and presents both challenges and opportunities for drug delivery strategies targeting auditory systems. This review elucidates the complex architecture and function of the BLB while shedding light on its clinical implications.

Recent progress in imaging and modeling techniques has significantly deepened our understanding of BLB structure and function. Studies have uncovered critical aspects of ion homeostasis, barrier permeability, and the role of various cell types within the BLB, yet its full anatomical structure and the interactions among its various cell types remain unclear. Future research, using advanced microscopy and imaging techniques, could provide a more detailed view of the BLB’s structure, offering a deeper understanding of its com-plexity and variability and establishing a foundation for further studies.

In-depth study of the molecular mechanisms of the BLB is also one of the key directions for the future. The function of the BLB depends on the coordinated action of various ion channels and transport proteins. Understanding these molecular mechanisms will not only help reveal the specific role of the BLB in maintaining inner ear homeostasis but will also provide a theoretical basis for developing therapeutic strategies for inner ear diseases.

The BLB poses significant challenges for targeted drug delivery to the inner ear. Emerging evidence reveals the BLB's dynamic responsiveness to external stimuli - including acoustic trauma, inflammatory mediators, and ototoxic substances - highlighting both its remarkable adaptability and inherent vulnerability. Despite these insights, developing non-invasive or minimally invasive techniques capable of achieving efficient and selective inner ear targeting continues to present formidable scientific and technical hurdles.

Notably, some newly developed non-invasive inner ear drug delivery strategies have present promising therapeutic potential. These include sound therapy, ultrasound therapy assisted by microbubbles, inner ear-targeting peptides, and the administration route via the cerebrospinal fluid conduit. Other strategies, such as lipid-soluble nanoparticles, receptor-based approaches, and the use of transporters or vesicles as natural delivery pathways, have also shown promise for more efficient and less invasive drug delivery. These emerging strategies collectively aim to enhance delivery efficiency while reducing invasiveness, thereby optimizing therapeutic efficacy and minimizing systemic adverse effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y.Y. and Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, Z.Y.Y, X.Y.W, G.Y. and Y.S.; visualization, Z.Y.Y; supervision, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82430035), the Foundation for Innovative Research Groups of Hubei Province (No. 2023AFA038), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Nos. 2021YFF0702303, 2024YFC2511101, 2023YFE0203200), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No.2024BRA019).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BLB |

Blood-labyrinth barrier |

| BM |

Basement membrane |

| CSF |

Cerebrospinal fluid |

| HRP |

Horseradish peroxidase |

| EP |

Endocochlear potential |

| SV |

Stria vascularis |

| PCs |

Pericytes |

| PVM/Ms |

Perivascular macrophage-like melanocytes |

| ECs |

Endothelial cells |

| MCs |

Marginal cells |

| ICs |

Intermediate cells |

| BCs |

Basal cells |

| TMPA |

Trimethylphenylammonium |

| BBB |

Blood-brain barrier |

| BRB |

Blood-retinal barrier |

| LRP1 |

Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 |

| MSCs |

Mesenchymal stem cells |

| AAV |

Adeno-associated virus |

| IETP2 |

Inner ear targeting peptide 2 |

| VEGF |

Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| TNF-α |

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| HIF-1α |

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α |

References

- Schnieder, E.-A. A Contribution to the Physiology of the Perilymph Part I: The Origins of Perilymph. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1974, 83, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahnke, K.; Gorgas, K. The Permeability of Blood Vessels in the Guinea Pig Cochlea. I. Vessels of the Modiolus and Spiral Vessel. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1974, 146, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnke, K. The Blood-Perilymph Barrier. Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1980, 228, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juhn, S.K.; Rybak, L.P. Labyrinthine Barriers and Cochlear Homeostasis. Acta Otolaryngol 1981, 91, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhn, S.K.; Rybak, L.P.; Prado, S. Nature of Blood-Labyrinth Barrier in Experimental Conditions. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1981, 90, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhn, S.K. Barrier Systems in the Inner Ear. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 1988, 105, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, H.-B. The Role of an Inwardly Rectifying K+ Channel (Kir4.1) in the Inner Ear and Hearing Loss. Neuroscience 2014, 265, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Nuttall, A.L. Upregulated iNOS and Oxidative Damage to the Cochlear Stria Vascularis Due to Noise Stress. Brain Res 2003, 967, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlemiller, K.K.; Rice, M.E.R.; Lett, J.M.; Gagnon, P.M. Absence of Strial Melanin Coincides with Age-Associated Marginal Cell Loss and Endocochlear Potential Decline. Hear Res 2009, 249, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.-X.; Chen, S.; Xie, L.; Ji, Y.-Z.; Wu, X.; Wang, W.-W.; Yang, Q.; Yu, J.-T.; Sun, Y.; Lin, X.; et al. Reduced Connexin26 in the Mature Cochlea Increases Susceptibility to Noise-Induced Hearing Loss in Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabba, S.V.; Oelke, A.; Singh, R.; Maganti, R.J.; Fleming, S.; Wall, S.M.; Everett, L.A.; Green, E.D.; Wangemann, P. Macrophage Invasion Contributes to Degeneration of Stria Vascularis in Pendred Syndrome Mouse Model. BMC Med 2006, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyberg, S.; Abbott, N.J.; Shi, X.; Steyger, P.S.; Dabdoub, A. Delivery of Therapeutics to the Inner Ear: The Challenge of the Blood-Labyrinth Barrier. Science Translational Medicine 2019, 11, eaao0935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiyama, G.; Lopez, I.A.; Ishiyama, P.; Vinters, H.V.; Ishiyama, A. The Blood Labyrinthine Barrier in the Human Normal and Meniere’s Disease Macula Utricle. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Wang, Z.; Ren, W.; Chen, L.; Xu, C.; Li, M.; Fan, S.; Xu, Y.; Chen, M.; Zheng, F.; et al. LDL Receptor-Related Protein 1 (LRP1), a Novel Target for Opening the Blood-Labyrinth Barrier (BLB). Sig Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Wang, W. Advances in Research on Labyrinth Membranous Barriers. Journal of Otology 2015, 10, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Yamasoba, T.; Ishibashi, T.; Miller, J.M.; Kaga, K. Effect of Noise Exposure on Blood-Labyrinth Barrier in Guinea Pigs. Hear Res 2002, 164, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Yamasoba, T.; Kaga, K. Development of the Blood-Labyrinth Barrier in the Rat. Hearing Research 1998, 116, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X. Pathophysiology of the Cochlear Intrastrial Fluid-Blood Barrier (Review). Hearing Research 2016, 338, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Dai, M.; Neng, L.; Zhang, J.H.; Zhi, Z.; Fridberger, A.; Shi, X. Perivascular Macrophage-like Melanocyte Responsiveness to Acoustic Trauma—a Salient Feature of Strial Barrier Associated Hearing Loss. FASEB J 2013, 27, 3730–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, A.; Agafonova, A.; Modafferi, S.; Salinaro, A.T.; Scuto, M.; Maiolino, L.; Fritsch, T.; Calabrese, E.J.; Lupo, G.; Anfuso, C.D.; et al. Blood–Labyrinth Barrier in Health and Diseases: Effect of Hormetic Nutrients. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neng, L.; Zhang, F.; Kachelmeier, A.; Shi, X. Endothelial Cell, Pericyte, and Perivascular Resident Macrophage-Type Melanocyte Interactions Regulate Cochlear Intrastrial Fluid-Blood Barrier Permeability. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 2013, 14, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardridge, W.M. The Blood-Brain Barrier: Bottleneck in Brain Drug Development. NeuroRx 2005, 2, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.-Z.; Le, Y.-Z. Significance of Outer Blood–Retina Barrier Breakdown in Diabetes and Ischemia. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2011, 52, 2160–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Han, W.; Yamamoto, H.; Tang, W.; Lin, X.; Xiu, R.; Trune, D.R.; Nuttall, A.L. The Cochlear Pericytes. Microcirculation 2008, 15, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Dai, M.; Fridberger, A.; Hassan, A.; Degagne, J.; Neng, L.; Zhang, F.; He, W.; Ren, T.; Trune, D.; et al. Perivascular-Resident Macrophage-like Melanocytes in the Inner Ear Are Essential for the Integrity of the Intrastrial Fluid-Blood Barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 10388–10393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakagami, M.; Sano, M.; Tamaki, H.; Matsunaga, T. Ultrastructural Study of the Effect of Acute Hyper- and Hypotension on the Stria Vascularis and Spiral Ligament. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 1983, 96, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, A.; Davies, C.; Southwood, C.M.; Frolenkov, G.; Chrustowski, M.; Ng, L.; Yamauchi, D.; Marcus, D.C.; Kachar, B. Deafness in Claudin 11-Null Mice Reveals the Critical Contribution of Basal Cell Tight Junctions to Stria Vascularis Function. J Neurosci 2004, 24, 7051–7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowe, M.-O.; Maier, H.; Petry, M.; Schweizer, M.; Schuster-Gossler, K.; Kispert, A. Impaired Stria Vascularis Integrity upon Loss of E-Cadherin in Basal Cells. Developmental Biology 2011, 359, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, K.P.; Barkway, C. Another Role for Melanocytes: Their Importance for Normal Stria Vascularis Development in the Mammalian Inner Ear. Development 1989, 107, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangemann, P. Comparison of Ion Transport Mechanisms between Vestibular Dark Cells and Strial Marginal Cells. Hearing Research 1995, 90, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patuzzi, R. Ion Flow in Stria Vascularis and the Production and Regulation of Cochlear Endolymph and the Endolymphatic Potential. Hearing Research 2011, 277, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renauld, J.M.; Khan, V.; Basch, M.L. Intermediate Cells of Dual Embryonic Origin Follow a Basal to Apical Gradient of Ingression Into the Lateral Wall of the Cochlea. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 867153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrenäs, M.-L.; Axelsson, A. The Development of Melanin in the Stria Vascularis of the Gerbil. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, M.; Takeuchi, S. Immunological Identification of an Inward Rectifier K+ Channel (Kir4.1) in the Intermediate Cell (Melanocyte) of the Cochlear Stria Vascularis of Gerbils and Rats. Cell Tissue Res 1999, 298, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, T.; Kimura, R.S.; Paul, D.L.; Takasaka, T.; Adams, J.C. Gap Junction Systems in the Mammalian Cochlea. Brain Research Reviews 2000, 32, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijpers, W.; Bonting, S.L. The Cochlear Potentials: II. The Nature of the Cochlear Endolymphatic Resting Potential. Pflugers Arch. 1970, 320, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nin, F.; Hibino, H.; Doi, K.; Suzuki, T.; Hisa, Y.; Kurachi, Y. The Endocochlear Potential Depends on Two K+ Diffusion Potentials and an Electrical Barrier in the Stria Vascularis of the Inner Ear. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 1751–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patuzzi, R. Ion Flow in Cochlear Hair Cells and the Regulation of Hearing Sensitivity. Hearing Research 2011, 280, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangemann, P. K+ Cycling and the Endocochlear Potential. Hearing Research 2002, 165, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagger, D.J.; Nevill, G.; Forge, A. The Membrane Properties of Cochlear Root Cells Are Consistent with Roles in Potassium Recirculation and Spatial Buffering. JARO 2010, 11, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Sawamura, S.; Ota, T.; Higuchi, T.; Ogata, G.; Hori, K.; Nakagawa, T.; Doi, K.; Sato, M.; Nonomura, Y.; et al. Fibrocytes in the Cochlea of the Mammalian Inner Ear: Their Molecular Architecture, Physiological Properties, and Pathological Relevance. MRAJ 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovee, S.; Klump, G.M.; Köppl, C.; Pyott, S.J. The Stria Vascularis: Renewed Attention on a Key Player in Age-Related Hearing Loss. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nin, F.; Hibino, H.; Doi, K.; Suzuki, T.; Hisa, Y.; Kurachi, Y. The Endocochlear Potential Depends on Two K+ Diffusion Potentials and an Electrical Barrier in the Stria Vascularis of the Inner Ear. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 1751–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilms, V.; Köppl, C.; Söffgen, C.; Hartmann, A.-M.; Nothwang, H.G. Molecular Bases of K+ Secretory Cells in the Inner Ear: Shared and Distinct Features between Birds and Mammals. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamura, N.; Salt, A.N. Permeability Changes of the Blood-Labyrinth Barrier Measured in Vivo during Experimental Treatments. Hearing Research 1992, 61, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurell, G.F.E.; Teixeira, M.; Duan, M.; Sterkers, O.; Ferrary, E. Intact Blood–Perilymph Barrier in the Rat after Impulse Noise Trauma. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 2008, 128, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, H.M.; Johnson, S.B.; Santi, P.A. Kanamycin-Furosemide Ototoxicity in the Mouse Cochlea: A 3-Dimensional Analysis. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 2014, 150, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, E.; Teixeira, M.; Aran, J.-M.; Ferrary, E. Taurine Entry into Perilymph of the Guinea Pig. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 1998, 255, 331–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Kitamura, K.; Nomura, Y. Anionic Sites of the Basement Membrane of the Labyrinth. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 1991, 111, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Kitamura, K.; Nomura, Y. Influence of Changed Blood pH on Anionic Sites in the Labyrinth. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 1995, 115, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Kaga, K. Effect of Cisplatin on the Negative Charge Barrier in Strial Vessels of the Guinea Pig A Transmission Electron Microscopic Study Using Polyethyleneimine Molecules. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1996, 253, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadoni, I.; Fornasa, G.; Rescigno, M. Organ-Specific Protection Mediated by Cooperation between Vascular and Epithelial Barriers. Nat Rev Immunol 2017, 17, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.P. Immunology of the Inner Ear: Evidence of Local Antibody Production. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1984, 93, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.P. Immunology of the Inner Ear: Response of the Inner Ear to Antigen Challenge. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1983, 91, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.; Ryan, A. Fundamental Immune Mechanisms of the Brain and Inner Ear. Head and Neck Surgery 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, N.K.; Harris, J.P. Cochlear Pathophysiology Associated with Inner Ear Immune Responses. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, M.; Okano, H.; Ogawa, K. Inflammatory and Immune Responses in the Cochlea: Potential Therapeutic Targets for Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 128290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, T.; Nakagawa, T.; Kita, T.; Kada, S.; Yoshimoto, M.; Nakahata, T.; Ito, J. Bone Marrow-Derived Cells Expressing Iba1 Are Constitutively Present as Resident Tissue Macrophages in the Mouse Cochlea. Journal of Neuroscience Research 2008, 86, 1758–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, K.; Discolo, C.M.; Keasler, J.R.; Ransohoff, R. Mononuclear Phagocytes Migrate into the Murine Cochlea after Acoustic Trauma. Journal of Comparative Neurology 2005, 489, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.H.; Zhang, C.; Frye, M.D. Immune Cells and Non-Immune Cells with Immune Function in Mammalian Cochleae. Hearing Research 2018, 362, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Choi, C.-H.; Chen, K.; Cheng, W.; Floyd, R.A.; Kopke, R.D. Reduced Formation of Oxidative Stress Biomarkers and Migration of Mononuclear Phagocytes in the Cochleae of Chinchilla after Antioxidant Treatment in Acute Acoustic Trauma. International Journal of Otolaryngology 2011, 2011, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredelius, L.; Rask-Andersen, H. The Role of Macrophages in the Disposal of Degeneration Products within the Organ of Corti after Acoustic Overstimulation. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 1990, 109, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corey, D.P.; Akyuz, N.; Holt, J.R. Function and Dysfunction of TMC Channels in Inner Ear Hair Cells. Csh Perspect Med 2019, 9, a033506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynard, P.; Thai-Van, H. Drug-Induced Hearing Loss: Listening to the Latest Advances. Therapies 2024, 79, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tn, L.; Lv, S.; J, L.; B, W. Current Insights in Noise-Induced Hearing Loss: A Literature Review of the Underlying Mechanism, Pathophysiology, Asymmetry, and Management Options. Journal of otolaryngology - head & neck surgery = Le Journal d’oto-rhino-laryngologie et de chirurgie cervico-faciale 2017, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Chen, S.; Xie, L.; Qiu, Y.; Bai, X.; Liu, X.-Z.; Zhang, H.-M.; Wang, X.-H.; Jin, Y.; Sun, Y.; et al. Local Macrophage-Related Immune Response Is Involved in Cochlear Epithelial Damage in Distinct Gjb2-Related Hereditary Deafness Models. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, P.J.; Kilcoyne, M.M. Ethacrynic Acid and Furosemide: Renal Pharmacology and Clinical Use. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 1969, 12, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Liu, H.; Qi, W.; Jiang, H.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Sun, H.; Gross, K.; Salvi, R. Ototoxic Effects and Mechanisms of Loop Diuretics. Journal of Otology 2016, 11, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Wang, X.; Jin, H.; Mi, Y.; Liu, L.; Dong, M.; Chen, Y.; Zou, Z. Cisplatin-Induced Ototoxicity: Updates on Molecular Mechanisms and Otoprotective Strategies. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2021, 163, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.J.T.; Vlajkovic, S.M. Molecular Characteristics of Cisplatin-Induced Ototoxicity and Therapeutic Interventions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 16545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, H.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.-H.; Park, C.; Kim, Y.; Kim, E.; Kim, J.-K.; Yun, K.-J.; Lee, K.-M.; Lee, H.-Y.; et al. Cisplatin Cytotoxicity of Auditory Cells Requires Secretions of Proinflammatory Cytokines via Activation of ERK and NF-kappaB. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 2007, 8, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Cai, J.; Xu, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, W. Cisplatin-Induced Stria Vascularis Damage Is Associated with Inflammation and Fibrosis. Neural Plasticity 2020, 2020, 8851525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anfuso, C.D.; Cosentino, A.; Agafonova, A.; Zappalà, A.; Giurdanella, G.; Trovato Salinaro, A.; Calabrese, V.; Lupo, G. Pericytes of Stria Vascularis Are Targets of Cisplatin-Induced Ototoxicity: New Insights into the Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Blood-Labyrinth Barrier Breakdown. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 15790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthrie, O.W. Aminoglycoside Induced Ototoxicity. Toxicology 2008, 249, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forge, A.; Fradis, M. Structural Abnormalities in the Stria Vascularis Following Chronic Gentamicin Treatment. Hearing Research 1985, 20, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Steyger, P.S. Trafficking of Systemic Fluorescent Gentamicin into the Cochlea and Hair Cells. JARO: Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology 2009, 10, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanyan, R.S.; Indzhykulian, A.A.; Vélez-Ortega, A.C.; Boger, E.T.; Steyger, P.S.; Friedman, T.B.; Frolenkov, G.I. TRPA1-Mediated Accumulation of Aminoglycosides in Mouse Cochlear Outer Hair Cells. JARO 2011, 12, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; McFadden, S.L.; Browne, R.W.; Salvi, R.J. Late Dosing with Ethacrynic Acid Can Reduce Gentamicin Concentration in Perilymph and Protect Cochlear Hair Cells. Hearing Res 2003, 185, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didier, A.; Miller, J.M.; Nuttall, A.L. The Vascular Component of Sodium Salicylate Ototoxicity in the Guinea Pig. Hearing Research 1993, 69, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.I.; lawrence, M.; Hawkins, J.E. Effects of Noise and Quinine on the Vessels of the Stria Vascularis: An Image Analysis Study. American Journal of Otolaryngology 1985, 6, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Salmon, M.; Regnault, B.; Cayet, N.; Caille, D.; Demuth, K.; Hardelin, J.-P.; Janel, N.; Meda, P.; Petit, C. Connexin30 Deficiency Causes Instrastrial Fluid-Blood Barrier Disruption within the Cochlear Stria Vascularis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 6229–6234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.-X.; Chen, S.; Xie, L.; Ji, Y.-Z.; Wu, X.; Wang, W.-W.; Yang, Q.; Yu, J.-T.; Sun, Y.; Lin, X.; et al. Reduced Connexin26 in the Mature Cochlea Increases Susceptibility to Noise-Induced Hearing Loss in Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2016, 17, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangemann, P.; Itza, E.M.; Albrecht, B.; Wu, T.; Jabba, S.V.; Maganti, R.J.; Lee, J.H.; Everett, L.A.; Wall, S.M.; Royaux, I.E.; et al. Loss of KCNJ10 Protein Expression Abolishes Endocochlear Potential and Causes Deafness in Pendred Syndrome Mouse Model. BMC Med 2004, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehm, H.L.; Zhang, D.-S.; Brown, M.C.; Burgess, B.; Halpin, C.; Berger, W.; Morton, C.C.; Corey, D.P.; Chen, Z.-Y. Vascular Defects and Sensorineural Deafness in a Mouse Model of Norrie Disease. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 4286–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruegel, J.; Rubel, D.; Gross, O. Alport Syndrome—Insights from Basic and Clinical Research. Nat Rev Nephrol 2013, 9, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, J.; Jackson, I.J.; Steel, K.P. Light (B), a Mutation That Causes Melanocyte Death, Affects Stria Vascularis Function in the Mouse Inner Ear. Pigment Cell Research 1993, 6, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, K.; Sakagami, M.; Umemoto, M.; Takeda, N.; Doi, K.; Kasugai, T.; Kitamura, Y. Strial Dysfunction in a Melanocyte Deficient Mutant Rat (Ws/Ws Rat). Acta Oto-Laryngologica 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Nathans, J. Estrogen-Related Receptor β/NR3B2 Controls Epithelial Cell Fate and Endolymph Production by the Stria Vascularis. Developmental Cell 2007, 13, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.-J.; Liu, X.-Z.; Tu, L.; Sun, Y. Cytomembrane Trafficking Pathways of Connexin 26, 30, and 43. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 10349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.-B.; Kikuchi, T.; Ngezahayo, A.; White, T.W. Gap Junctions and Cochlear Homeostasis. J Membr Biol 2006, 209, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Bitner-Glindzicz, M.; Tranebjærg, L.; Tinker, A. A Spectrum of Functional Effects for Disease Causing Mutations in the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen Syndrome. Cardiovascular Research 2001, 51, 670–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Kim, Y.; Zhou, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Lin, X. Virally Mediated Kcnq1 Gene Replacement Therapy in the Immature Scala Media Restores Hearing in a Mouse Model of Human Jervell and Lange-Nielsen Deafness Syndrome. EMBO Molecular Medicine 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidman, M.D.; Quirk, W.S.; Shirwany, N.A. Mechanisms of Alterations in the Microcirculation of the Cochlea. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1999, 884, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X. Physiopathology of the Cochlear Microcirculation. Hearing Research 2011, 282, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.-A.; Lyu, A.-R.; Jeong, S.-H.; Kim, T.H.; Park, M.J.; Park, Y.-H. Acoustic Trauma Modulates Cochlear Blood Flow and Vasoactive Factors in a Rodent Model of Noise-Induced Hearing Loss. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Dai, M.; Wilson, T.M.; Omelchenko, I.; Klimek, J.E.; Wilmarth, P.A.; David, L.L.; Nuttall, A.L.; Gillespie, P.G.; Shi, X. Na+/K+-ATPase A1 Identified as an Abundant Protein in the Blood-Labyrinth Barrier That Plays an Essential Role in the Barrier Integrity. PLoS One 2011, 6, e16547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X. Cochlear Pericyte Responses to Acoustic Trauma and the Involvement of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. The American Journal of Pathology 2009, 174, 1692–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Han, W.; Chen, X.; Guo, W.; Liu, K.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Sai, N. Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 and -9 Contribute to Functional Integrity and Noise-induced Damage to the Blood-Labyrinth-Barrier. Molecular Medicine Reports 2017, 16, 1731–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, K.; Liberman, M.C. Lateral Wall Histopathology and Endocochlear Potential in the Noise-Damaged Mouse Cochlea. JARO 2003, 4, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Hou, Z.; Cai, J.; Dong, M.; Shi, X. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Middle Ear Inflammation Disrupts the Cochlear Intra-Strial Fluid–Blood Barrier through Down-Regulation of Tight Junction Proteins. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0122572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, N.J. Inflammatory Mediators and Modulation of Blood–Brain Barrier Permeability. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2000, 20, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Rao, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, K.; Tang, Y. Lipopolysaccharide Disrupts the Cochlear Blood-Labyrinth Barrier by Activating Perivascular Resident Macrophages and up-Regulating MMP-9. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 2019, 127, 109656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimiya, I.; Yoshida, K.; Hirano, T.; Suzuki, M.; Mogi, G. Significance of Spiral Ligament Fibrocytes with Cochlear Inflammation. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 2000, 56, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, K.; Hartsock, J.J.; Johnson, S.; Santi, P.; Salt, A.N. Systemic Lipopolysaccharide Compromises the Blood-Labyrinth Barrier and Increases Entry of Serum Fluorescein into the Perilymph. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 2014, 15, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltesz, P.; Der, H.; Veres, K.; Laczik, R.; Sipka, S.; Szegedi, G.; Szodoray, P. Immunological Features of Primary Anti-Phospholipid Syndrome in Connection with Endothelial Dysfunction. Rheumatology 2008, 47, 1628–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thin and Open Vessel Windows for Intra-Vital Fluorescence Imaging of Murine Cochlear Blood Flow. Hearing Research 2014, 313, 38–46. [CrossRef]

- F, Z.; J, Z.; L, N.; X, S. Characterization and Inflammatory Response of Perivascular-Resident Macrophage-like Melanocytes in the Vestibular System. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology : JARO 2013, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neng, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, F.; Lopez, I.A.; Dong, M.; Shi, X. Structural Changes in Thestrial Blood–Labyrinth Barrier of Aged C57BL/6 Mice. Cell Tissue Res 2015, 361, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z, H.; L, N.; J, Z.; J, C.; X, W.; Y, Z.; Ia, L.; X, S. Acoustic Trauma Causes Cochlear Pericyte-to-Myofibroblast-Like Cell Transformation and Vascular Degeneration, and Transplantation of New Pericytes Prevents Vascular Atrophy. The American journal of pathology 2020, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Wang, X.; Cai, J.; Zhang, J.; Hassan, A.; Auer, M.; Shi, X. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Subunit B Signaling Promotes Pericyte Migration in Response to Loud Sound in the Cochlear Stria Vascularis. JARO 2018, 19, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S, D.; F, R.; D, M.; G, G.; L, P.; L, S. An in Vitro Blood-Brain Barrier Model: Cocultures between Endothelial Cells and Organotypic Brain Slice Cultures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1998, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neng, L.; Zhang, W.; Hassan, A.; Zemla, M.; Kachelmeier, A.; Fridberger, A.; Auer, M.; Shi, X. Isolation and Culture of Endothelial Cells, Pericytes and Perivascular Resident Macrophage-like Melanocytes from the Young Mouse Ear. Nat Protoc 2013, 8, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekulic-Jablanovic, M.; Paproth, J.; Sgambato, C.; Albano, G.; Fuster, D.G.; Bodmer, D.; Petkovic, V. Lack of NHE6 and Inhibition of NKCC1 Associated With Increased Permeability in Blood Labyrinth Barrier-Derived Endothelial Cell Layer. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 862119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tm, C.; Eb, B.; J, R. Toward Three-Dimensional in Vitro Models to Study Neurovascular Unit Functions in Health and Disease. Neural regeneration research 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neng, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, F.; Lopez, I.A.; Dong, M.; Shi, X. Structural Changes in Thestrial Blood–Labyrinth Barrier of Aged C57BL/6 Mice. Cell Tissue Res 2015, 361, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulic, M.; Abdollahi, N.; Graf, L.; Deigendesch, N.; Puche, R.; Bodmer, D.; Petkovic, V. Human Blood-Labyrinth Barrier on a Chip: A Unique in Vitro Tool for Investigation of BLB Properties. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 25508–25517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulic, M.; Puche, R.; Bodmer, D.; Petkovic, V. Human Blood-Labyrinth Barrier Model to Study the Effects of Cytokines and Inflammation. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hao, J.; Li, K.S. Current Strategies for Drug Delivery to the Inner Ear. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2013, 3, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ERSNER, M.S.; SPIEGEL, E.A.; ALEXANDER, M.H. TRANSTYMPANIC INJECTION OF ANESTHETICS FOR THE TREATMENT OF MÉNIÈRE’S SYNDROME. A.M.A. Archives of Otolaryngology 1951, 54, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowe, S.N.; Jacob, A. Round Window Perfusion Dynamics: Implications for Intracochlear Therapy. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery 2010, 18, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, W.F.; Borenstein, J.T.; Chen, Z.; Fiering, J.; Handzel, O.; Holmboe, M.; Kim, E.S.; Kujawa, S.G.; McKenna, M.J.; Mescher, M.M.; et al. Development of a Microfluidics-Based Intracochlear Drug Delivery Device. Audiology and Neurotology 2009, 14, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Wang, H.; Cheng, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Cao, Q.; Tang, H.; Hu, S.; Gao, K.; et al. AAV1-hOTOF Gene Therapy for Autosomal Recessive Deafness 9: A Single-Arm Trial. The Lancet 2024, 403, 2317–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, Y.; Currie, J.-C.; Demeule, M.; Régina, A.; Ché, C.; Abulrob, A.; Fatehi, D.; Sartelet, H.; Gabathuler, R.; Castaigne, J.-P.; et al. Transport Characteristics of a Novel Peptide Platform for CNS Therapeutics. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2010, 14, 2827–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jh, P.; Y, K.; J, Y.; Jw, C. Antioxidant Therapy against Oxidative Damage of the Inner Ear: Protection and Preconditioning. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sound Conditioning Reduces Noise-Induced Permanent Threshold Shift in Mice. Hearing Research 2000, 148, 213–219. [CrossRef]