1. Introduction

Mini screws are used for a variety of purposes in modern dentistry and are often preferred in the treatment of malocclusions, particularly in orthodontic treatment. Anchorage, defined as resistance to unwanted tooth movement, is a prerequisite for the treatment of dental and skeletal malocclusions. Controlling anchorage helps to prevent unwanted tooth movement. However, even a small reactive force can cause unwanted movement; to avoid this, absolute anchorage is important [

1]. Skeletal anchorage systems such as dental implants, mini plates, micro or mini screws are systems that aim to provide absolute anchorage by preventing loss of anchorage. Among these systems, miniscrews are often preferred by dental professionals due to their advantages such as ease of clinical application, long-term stabilisation with immediate loading, relative patient comfort and cost-effectiveness [

2]. Miniscrews are generally mechanically attached to the bone, are not osseointegrated and are commonly used by orthodontists and oral and maxillofacial surgeons [

3,

4]. Mini screws have a wide range of applications, particularly in orthodontic treatment. They are used for correction of deep malocclusions, closure of extraction gaps, correction of inclined occlusal planes, alignment of the midline of teeth, extrusion of impacted teeth, intrusion, distalisation, mesialisation of teeth, alignment of third molars, correction of sagittal and transversal malocclusions [

5].

Miniscrews are generally available in 2 types: self-drilling and self-tapping. The advantage of self-drilling miniscrews is that they do not require pilot drilling during the insertion procedure. The miniscrews used in orthodontics differ from those used in oral and maxillofacial surgery, particularly in their head design. In this way, orthodontic miniscrews allow the appropriate mechanics to be connected to the screw to ensure absolute anchorage. Orthodontic miniscrews are generally available in 2 types: mushroom head and bracket head [

6]. In cases where the cortical bone is thicker than 2 mm, pilot drilling may also be required for self-drilling screws as the applied force will bend the tip of the screw. It has been recommended that if pilot drilling is required, it should be performed by an oral and maxillofacial surgeon. However, the information on the depth and width of the guide socket to be created according to the mini-hole to be used is limited and advisory, and it is generally recommended that the width and depth of the guide socket should be minimal [

3,

7,

8].

Polyurethane (PU) is a polymeric material that can have a very wide range of chemical and physical properties, thanks to the possibility of modifying its structure or production methods. It can therefore be adapted to different requirements in many fields (coatings, adhesives, thermoplastics) [

9]. Due to its mechanical properties, PU is recommended for use in in vitro bone modelling [

10,

11]. Due to its homogeneous and stable physical properties, it is preferred for modelling alveolar bone in in vitro studies to test different implant materials and to standardise procedures by eliminating anatomical and structural differences in bone [

12,

13,

14].

In general, human bone is not homogeneous. Its physical properties vary greatly by species, age, sex, type (e.g. femoral, mandibular, cortical and trabecular) and even by site of sample collection. For these reasons, the complex and heterogeneous nature of human bone and ethical issues complicate the conduct of clinical trials [

15]. Given the difficulties of working with human cadaveric and animal bone, synthetic polyurethane foams have been widely used as alternative materials to bone in various biomechanical tests due to their similar void structure, density and consistent mechanical properties [

16]. The literature shows that PU with different densities and properties is preferred as a bone model material in various mini-screw and implant studies where tensile tests, resonance frequency analysis, insertion and removal torque values are investigated [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. In these studies, where polyurethane blocks simulate bone, it is noted that the effect of screw shape, length and design, which are among the factors influencing the primary stability of miniscrews, have been investigated [

22]. There are only a few studies in the literature that have evaluated the effect of pilot drilling to create a guide socket on the primary stability of miniscrews [

23,

24]. Due to the difficulty of working in cortical bone, we believe that the creation of a guide socket will not only structurally damage a self-drilling miniscrew, but also facilitate the initial entry of the miniscrew into the bone, prevent the expansion of the socket, especially the entry portion, and subsequently allow the miniscrew to be properly placed without changing the angle. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of creating a guide socket during miniscrew insertion on the primary stability of the miniscrew by measuring insertion and extraction torques in an in vitro PU cortical bone model. The null hypothesis of this study was that the guide socket would have no effect on the stability of the miniscrew..

2. Materials and Methods

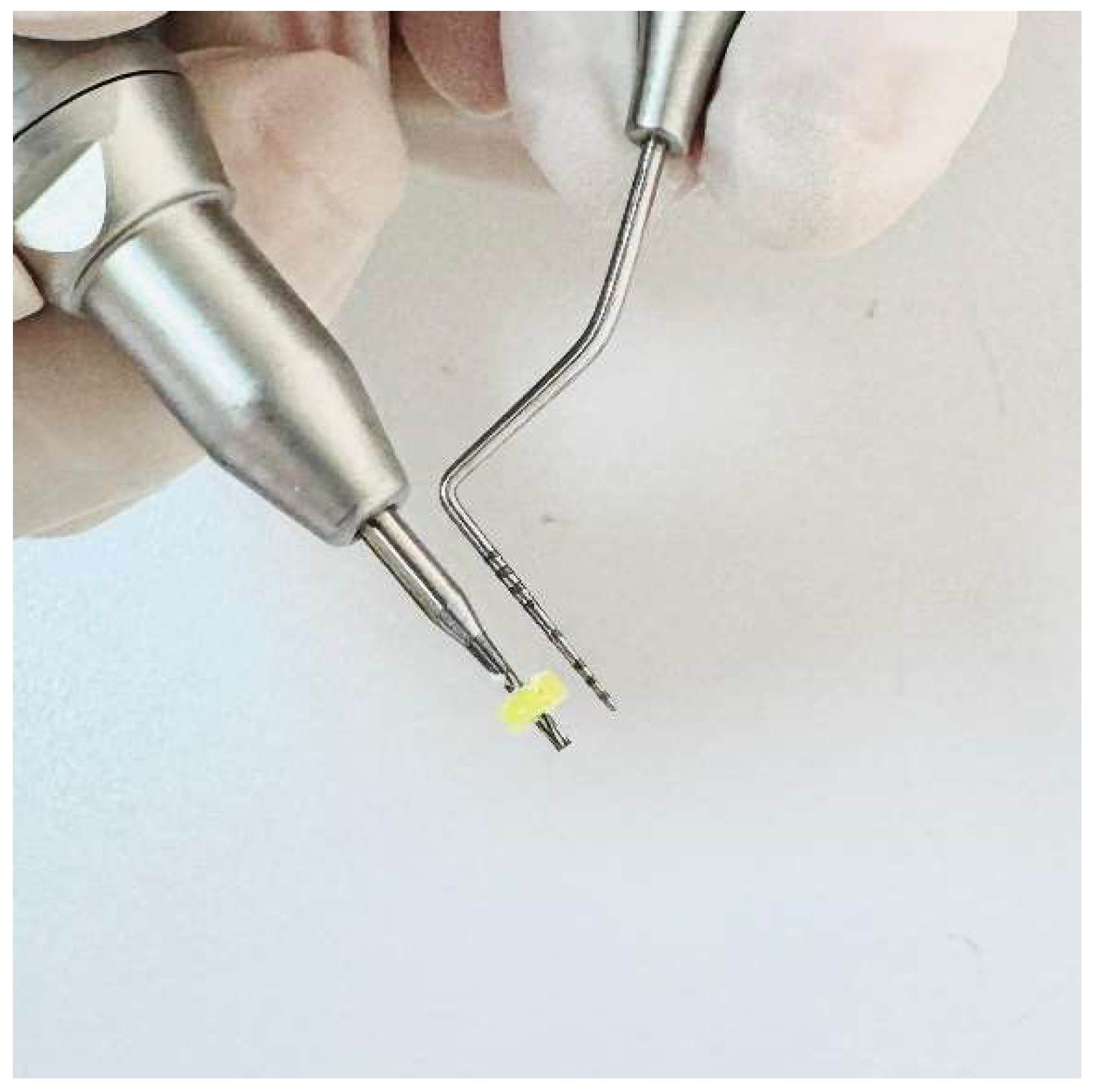

This in vitro study was conducted at Van Yüzüncü Yıl University Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery in December 2024. Polyurethane blocks 260x82x20 mm (Puryap, Construction Chemicals and Machinery Industry Trade Company Limited, Istanbul, Turkey) with a density of 60 pcf were used for in vitro cortical bone modelling. Self-drilling mushroom-head titanium miniscrews (Ancor Orthodontics, Ankara, Turkey) measuring 1.8 x 0.8 mm were used as miniscrews (

Figure 1). A 1 mm diameter surgical fissure drill was used to create the guide sockets in the study groups (

Figure 2). G*power version 3.1.9.4 was used to calculate the sample size of the study. The effect size was determined from the reference article to be 0.76, and it was calculated that a minimum of 14 subjects per group should be included in the study for an alpha error of 0.01 and 95% power [

22]. Accordingly, the study was conducted on a total of 45 miniscrews in 3 groups, with 15 miniscrews in each group. The guide sockets in the study groups were created using a physiodispenser (Straumann Surgical Motor Pro, NSK Nakanishi Inc., Kanuma, Tochigi, Japan) and a 1:1 reduction contra-angle handpiece (NSK Ti-Max X-SG65, Tochigi, Japan) with standard parameters of 1000 revolutions per minute (rpm) and 50 torque under sterile saline . Mini screws were placed in all groups using a motorised screwdriver with a physiodispenser (Straumann Surgical Motor Pro, NSK Nakanishi Inc., Kanuma, Tochigi, Japan) and a 20:1 implant handpiece (NSK S-Max SG20, Tochigi, Japan) at 30 rpm according to a standardised protocol (

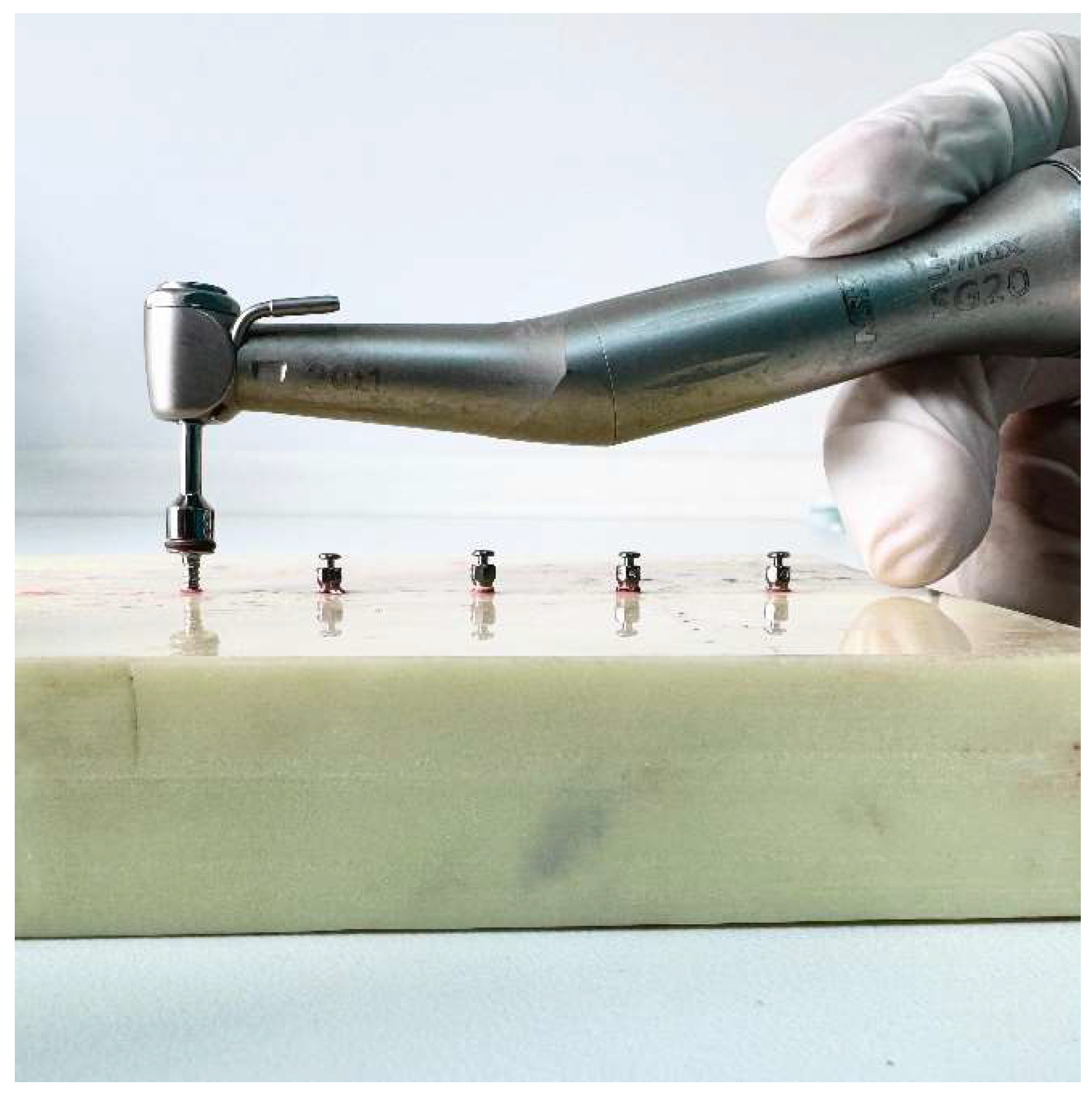

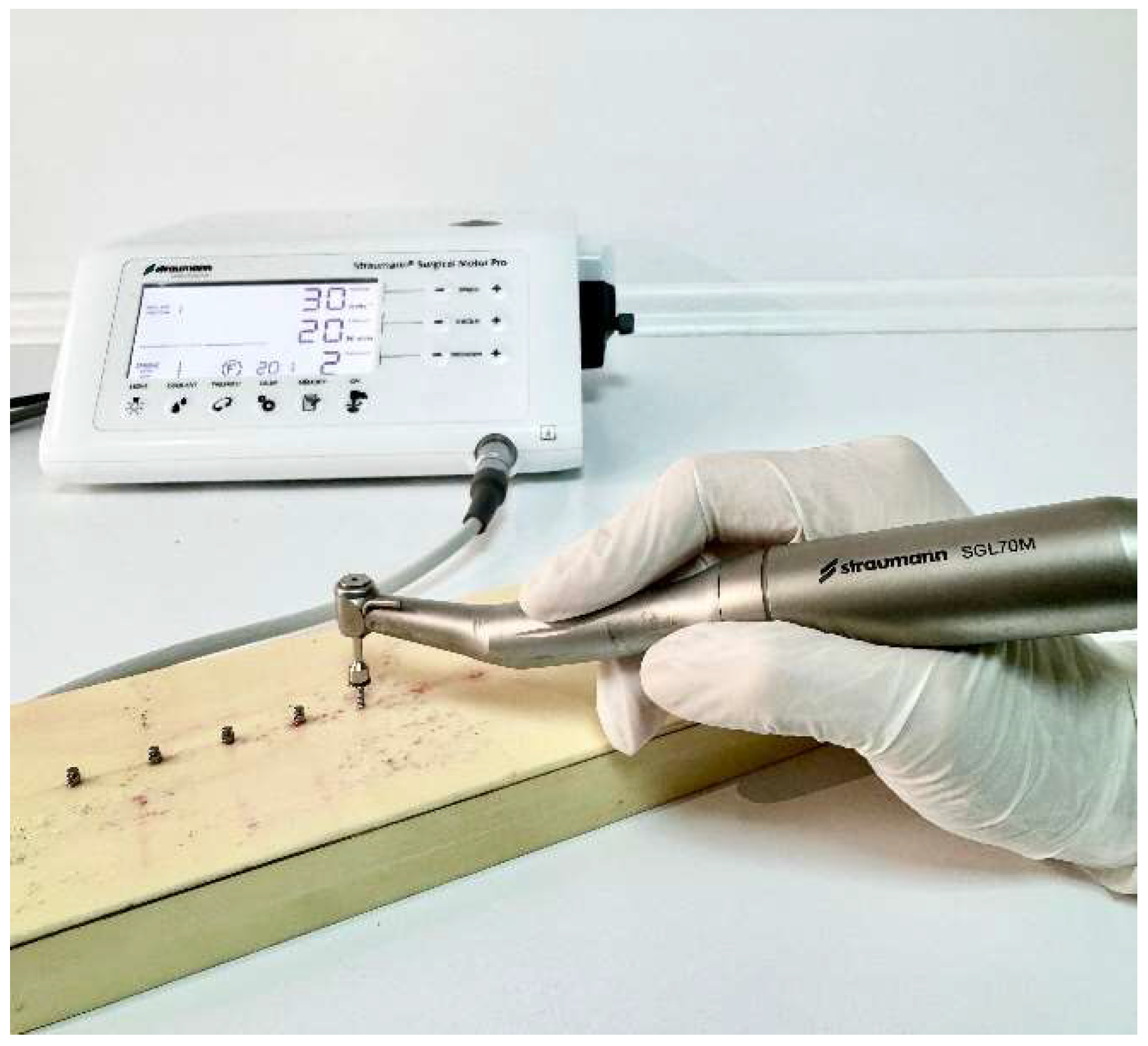

Figure 3).

Randomisation was applied to both the creation of the guide sockets in groups 2 and 3 and the placement of the miniscrews in all groups using an online software program [

25]. In other words, instead of completing one group and moving on to the next, the group and procedure order information was randomised for each application from the 1st to the 15th application for opening the sockets and placing the miniscrews in each group.

2.1. Socket Preparation

The preparation of the guide sockets in group 2 and group 3, including the 2 and 4 mm deep guide sockets, was performed using a 1:1 reduction contra-angle handpiece (NSK Ti-Max X-SG65, Tochigi, Japan) with standard parameters of 1000 revolutions per minute (rpm) and 50 torque with a 1 mm surgical fissure burr. When preparing the sockets, care was taken to ensure that the wall thickness of the sockets and the distance between them were the same to ensure standardisation. The 2mm and 4mm guide sockets were prepared by a specialist surgeon not involved in the study to ensure blinding of the author surgeons. The surgeon who prepared the sockets checked that they were 1 mm wide and 2 and 4 mm deep according to the group. Inappropriate sockets were excluded from the study and new sockets were created to complete the 15 in each group.

2.2. Study Groups

The miniscrews included in the study were divided into 3 groups. Group 1 (control group) did not include a guide socket. Self-drilling miniscrews were inserted into the polyurethane block according to the protocol. In group 2, a 1 mm wide guide socket was inserted. In these sockets, mini-screws were inserted into the polyurethane block according to the established protocol. In group 3, a 1 mm wide and 4 mm deep guide socket was created. In these sockets, miniscrews were inserted into the polyurethane block according to the established protocol.

The polyurethane blocks used in all 3 groups had a density of 60 pcf. The blocks were manufactured at the same time under the same humidity and temperature conditions. In all 3 groups, the miniscrews were inserted by the same author surgeon (NHK). Insertion torques (ITs) and removal torques (RTs) were measured to assess the primary stability of the miniscrews. When inserting the miniscrews, the unit was initially set to a torque value of 5. If the miniscrews did not rotate before being fully inserted, the value was increased by 5 torques (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The last torque value at which the miniscrew was fully inserted in the neck region was recorded as the insertion torque value. The device was then operated in reverse mode without removing the miniscrews from the implant handpiece and the same protocol as for insertion was followed and the lowest torque value that rotated the implant and removed it from the socket was taken as the removal torque. During insertion and removal, the miniscrews were placed perpendicular to the blocks and no lateral force was applied.

Socket preparation and miniscrew insertion were performed by surgeons to mimic the clinical environment. The surgeons performed the procedures with the wrists resting on the model to ensure standardisation in the preparation of the guide sockets and insertion of the mini-screws.

4. Discussion

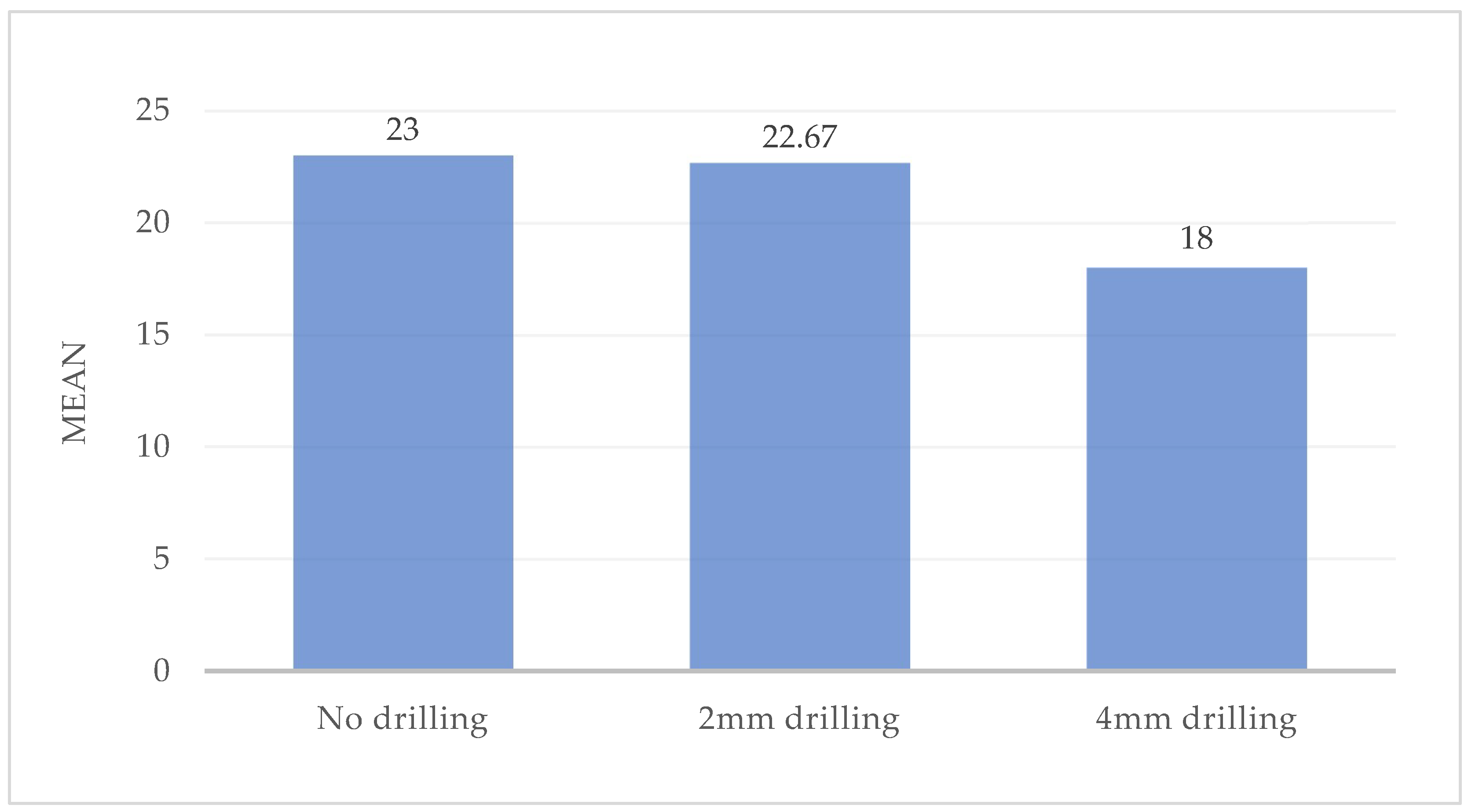

This study evaluated the effect of guide sockets created on a polyurethane cortical bone model on the primary stability of the mushroom head orthodontic miniscrew. According to our results, the creation of guide sockets did affect the primary stability of the miniscrew and therefore the null hypothesis was rejected.

Miniscrews are used as temporary anchorage devices because of their immediate loading, ease of insertion and removal, and relatively low cost. The small width of miniscrews allows them to be inserted atraumatically into the alveolar bone between the roots of the teeth. Despite the advantages of self-drilling miniscrews, as all surgical procedures have complications, the use of self-drilling miniscrews has been associated with inadequate anchorage, miniscrew migration and failure [

26]. Mechanical evaluation of the stability of implanted screws, including miniscrews, is usually measured by insertion and removal torque [

27]. The stability of the miniscrews is influenced by many factors such as insertion technique, insertion angle, length, applied loads, bone density and cortical bone thickness. Among these factors, the thickness and density of the alveolar bone in which the miniscrews are placed is one of the most important factors affecting stability [

21,

28]. Baumgaertel et al. reported that the insertion torque increased with increasing cortical bone thickness [

29]. High stability of the miniscrew is desirable for anchorage, but it has been reported that screw-related complications increase with increasing insertion torque during miniscrew placement. Self-drilling miniscrews may be easier to place in areas of thin cortical bone, and studies have also reported that miniscrew fracture may occur in cases where cortical bone thickness increases [

22,

28]. These results show that care must be taken when working on thick cortical bone. For this reason, in this study we used a single layer 60 PCF polyurethane block to simulate thick cortical bone, which we believe simulates alveolar cortical bone in the clinical environment.

To simulate thick cortical bone, some studies have used acrylic models to evaluate the fracture resistance of miniscrews. Among these studies, in Smith's study, self-drilling screws of similar diameter from 6 different brands were placed in an acrylic model and fracture torques ranged from 25.8 to 72.07 [

28]. In another study, Wilmes et al (2011) placed many different types of miniscrews in acrylic blocks and showed that the miniscrews fractured with torques ranging from 10.8 Ncm to 64 Ncm depending on the type of miniscrew [

30]. In a study on a femoral bone model, Pithon et al. found fracture torques of various miniscrews ranging from 49.6 to 99.15 Ncm [

31]. These studies were concerned with the high torque values associated with miniscrew fracture in high density models simulating thick cortical bone, and given the results of the above studies, the fracture resistance of miniscrews may vary depending on the model material and miniscrew type [

28,

30,

31]. There are no studies in the literature that have evaluated mini-screw fracture in polyurethane blocks. In this study, no screw fracture was observed during insertion and removal of the mini-screws. It may not be appropriate to compare the results of studies using acrylic and animal models with our results using a polyurethane block. From the literature, polyurethane is an accepted material for alveolar bone simulation under in vitro conditions and is similar to bone in its mechanical and physical properties. In this study, we chose a polyurethane block for cortical bone modelling in accordance with the literature [

32,

33].

There are few studies in the literature that investigate the effect of the guide socket on the primary stability of the miniscrew in polyurethane models. Among these, Cho et al. investigated the effect of different guide socket formation methods on miniscrew stability. In their study, they used a 2-layer polyurethane block with a density of 40 pcf. They formed 2 groups according to the thickness of the outer layer. One group was 2mm thick with a density of 102 pcf and the other group was 4mm thick with a density of 102 pcf. They made 5mm deep guide sockets with hand and power drills and the width of the hand drill they used was 1.6mm wide. They found that there was no difference in insertion torque between the hand and power drills. They found that the removal torque was higher in the 4mm group [

24]. Similarly, the study by Phusantisampan et al investigated the effect of guide socket on miniscrew stability and 5mm deep guide sockets were created using pilot drills of 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4 and 1.5mm diameter. The polyurethane block used was a two-layer block with the inner part having a density of 20 pcf and the outer part having a thickness of 2 mm and a density of 40 pcf. According to the results of the study, the insertion torque values of the groups with guide sockets were lower than the control group without guide sockets. In their study, they also evaluated pull-out strength, another method of evaluating stability, and showed that the pull-out strength of the miniscrews placed in the sockets formed with small-diameter pilot drills was higher than that of those with larger diameters [

23]. In another study using two-layer polyurethane blocks, Heo et al. used polyurethane blocks with a 3 mm thick outer part with a density of 50 pcf and an inner part with a density of 30 pcf. In their study, they created guide sockets with depths of 1.5 and 4 mm and an angle of 60 degrees. They compared the stability of the miniscrew in guide sockets of different depths with the control group without guide sockets. They found that there was a decrease in insertion torque in both groups compared to the control group, but the decrease was greater in the 4mm group [

34]. In the study by Cho and Baek, using the same polyurethane model and 1mm pilot drill as in the study by Heo et al, the insertion torque of the guide sockets prepared at a depth of 1.5 and 3mm with a 90 degree angle was compared with the control group. The results showed that the insertion torque value in the control group, i.e. the group without a guide socket, was higher than in the other groups prepared with a guide socket. The authors attributed the main reason for this decrease to the drilling of the cortical part of the cortical part in the blocks with guide sockets and the thickness of the supported cortical part [

35]. Although all these studies used two-layer polyurethane blocks, it can be seen that the outer and inner layer thicknesses and densities of the blocks are different, and despite these differences it can be seen that cortical bone was modelled in all 3 studies. It can be seen that as the density of the outer layer, which is the dense part in the models used, increases, so does the stability of the miniscrew. The insertion torques in the control groups in these studies ranged from 11.58 to 29.75 Ncm. Unlike the above studies, our study used a single layer polyurethane block with a density of 60 pcf. In this study, the insertion torque values obtained for the control group were found to be 23 Ncm, in agreement with the literature, and this result supports the use of the blocks we used in modelling cortical bone. In the present study, using screws of the same diameter as in the previous studies, it was observed that, unlike in the previous studies, the formation of the guide socket did not reduce the stability of the miniscrew, on the contrary, the guide socket formed at a depth of 2 mm did not affect the insertion torque value of the miniscrew, but increased the removal torque value. When the depth of the guide socket was increased to 4 mm, it was observed that the insertion torque value decreased, but the removal torque value did not change. We believe that this difference in our study is due to the different density and thickness of the polyurethane model used, as well as the different depth and diameter of the prepared guide sockets. Cho and Baek and Heo et al. showed that the insertion torque values decreased as the guide sleeve diameter remained the same and the depth increased. Similar to these studies, in the present study, the miniscrew insertion torque value of the 4 mm depth guide socket was less than that of the 2 mm depth guide socket.

The use of artificial bone in mechanical studies may give different results to those obtained with human bone. The main reason for this is the inhomogeneous bone density at the insertion site in human bone. To control for bone density as a variable, it is advantageous to use experimental artificial bone with homogeneous density values and a linear direction during insertion [

29]. Therefore, a bone model with a density of 60 pcf (approximately 0.96 g/cm3), similar to the density of the jaw bone, was used in this study. Although self-drilling screws are used for the stability of miniscrews, predrilling can be considered in all areas of high bone density. The diameter and depth of predrilling should be appropriate for the bone quality and the area where the miniscrew will be placed [

36]. Self-drilling miniscrews may be subject to dislocation under orthodontic loading. Although the behaviour of self-drilling miniscrews under orthodontic loading is not clinically clear, a miniscrew placed in the interdental region may be displaced under loading and a serious problem may occur if it contacts the adjacent tooth roots [

26]. For this reason, we believe that increasing the stability of the miniscrew may be beneficial. In this study, the effect of guide socket formation on the primary stability of the miniscrew was analysed. The 2mm and 4mm deep guide socket study groups were compared with the no guide socket group. Higher removal torques were achieved in the 2mm deep guide socket group compared to the control group and the 4mm deep guide socket group. Lower insertion torques were achieved in the 4mm deep guide socket group compared to the other 2 groups. According to these results, displacements at the initial bone entry may lead to wider socket formation and this may reduce stability. It shows that with a guided stem we can achieve a more stable stem and therefore increase primary stability. Increasing the depth of the socket may decrease the screw contact achieved and therefore decrease stability. These results from our study have shown that mushroom head miniscrews can be used in dentistry with an appropriate guided socket where skeletal anchorage is required. In cases where the cortical bone is dense and thick, it has been observed that a guide socket of appropriate depth and diameter can increase or decrease the stability of the miniscrew. Thus, the use of the appropriate guide slot allows for the management of unfavourable and challenging factors emanating from the cortical bone.

The limitations of this study were as follows: although the guide sockets in the study were created by a surgeon independent of the study, there may have been minimal variation in the sockets due to application. The miniscrews were inserted by a surgeon conducting the study and there may have been minimal differences in the balance of forces applied during insertion. The study used 2mm and 4mm sockets and different widths and depths of the sockets may have produced different results. At the same time, the choice of different densities of the polyurethane block used in the study may also have caused differences in the results of the study.