3.1. The Iteration of Piecewise Function

A piecewise function is a mathematical function that is defined by different rules or formulas over different intervals or regions of its domain. The Collatz function, denoted by , can be expressed as a piecewise function, with separate cases for odd and even numbers.

An iterative function is a function that is repeatedly applied to its own output. In other words, the output of the function is used as the input for the next iteration of the function. Iterative methods involve using iterate functions to repeatedly update an initial estimate or solution until a desired level of accuracy is achieved.

In order to proof the Collatz conjecture 1 in section 1, finding the beingness and finiteness of the number m in the expression for a natural number n is the main challenge. Iteration is the key to Collatz conjecture, and although there are only two cases where piecewise functions are combined with iterative functions, the result is difficult to control.

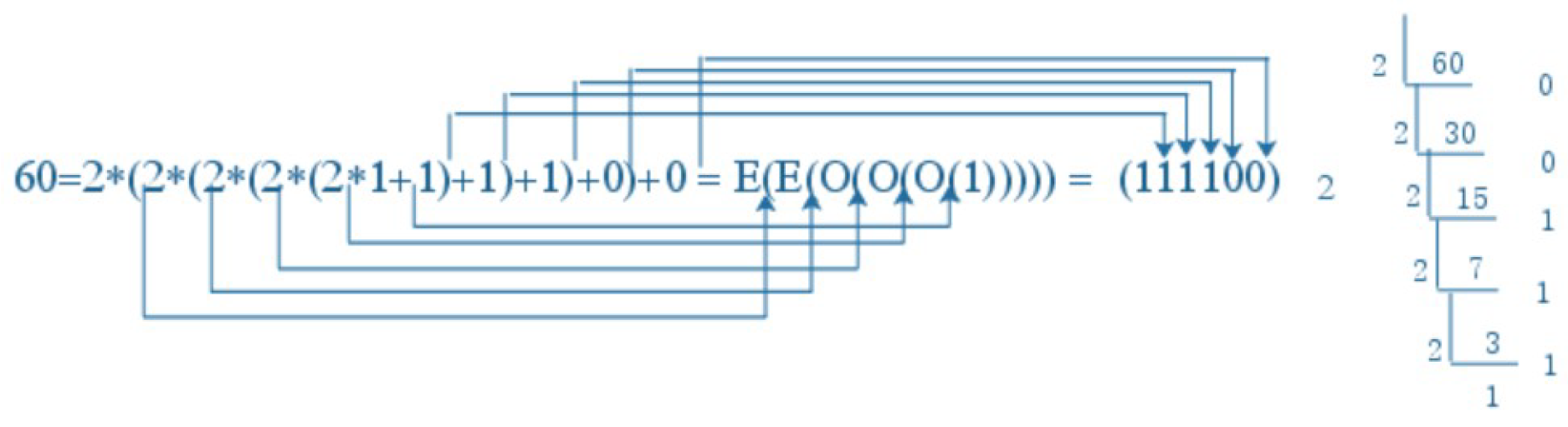

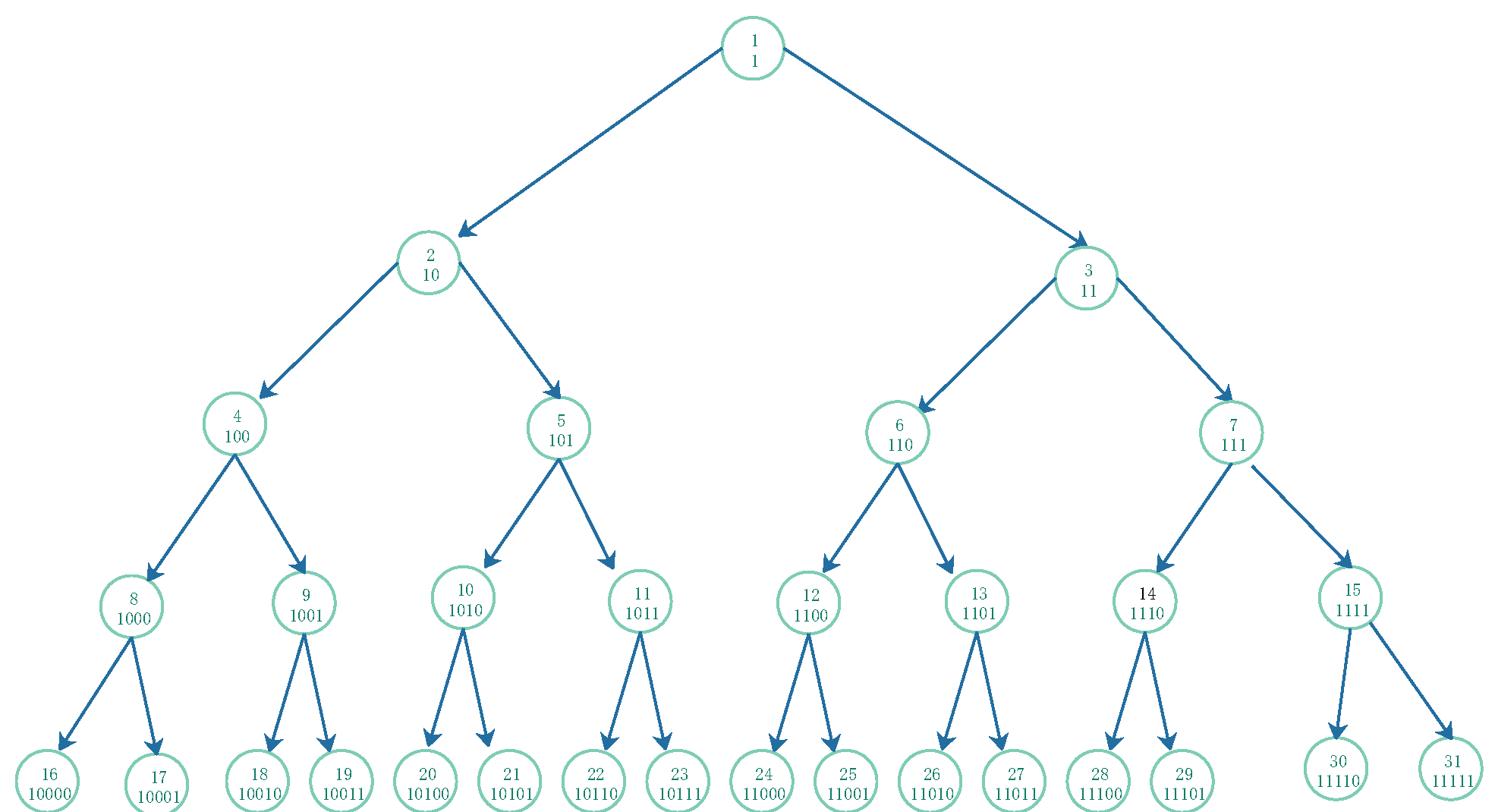

For given natural k, the iterative formula results n, we know that k is the length of the binary string of n minus 1, it is also the level of the full binary tree. In decimal notation, we represent n, which obscures the iteration process of odd- and /or even-number functions. When n is represented as a binary string, it can be used to understand how odd- and /or even-number functions iterative work.

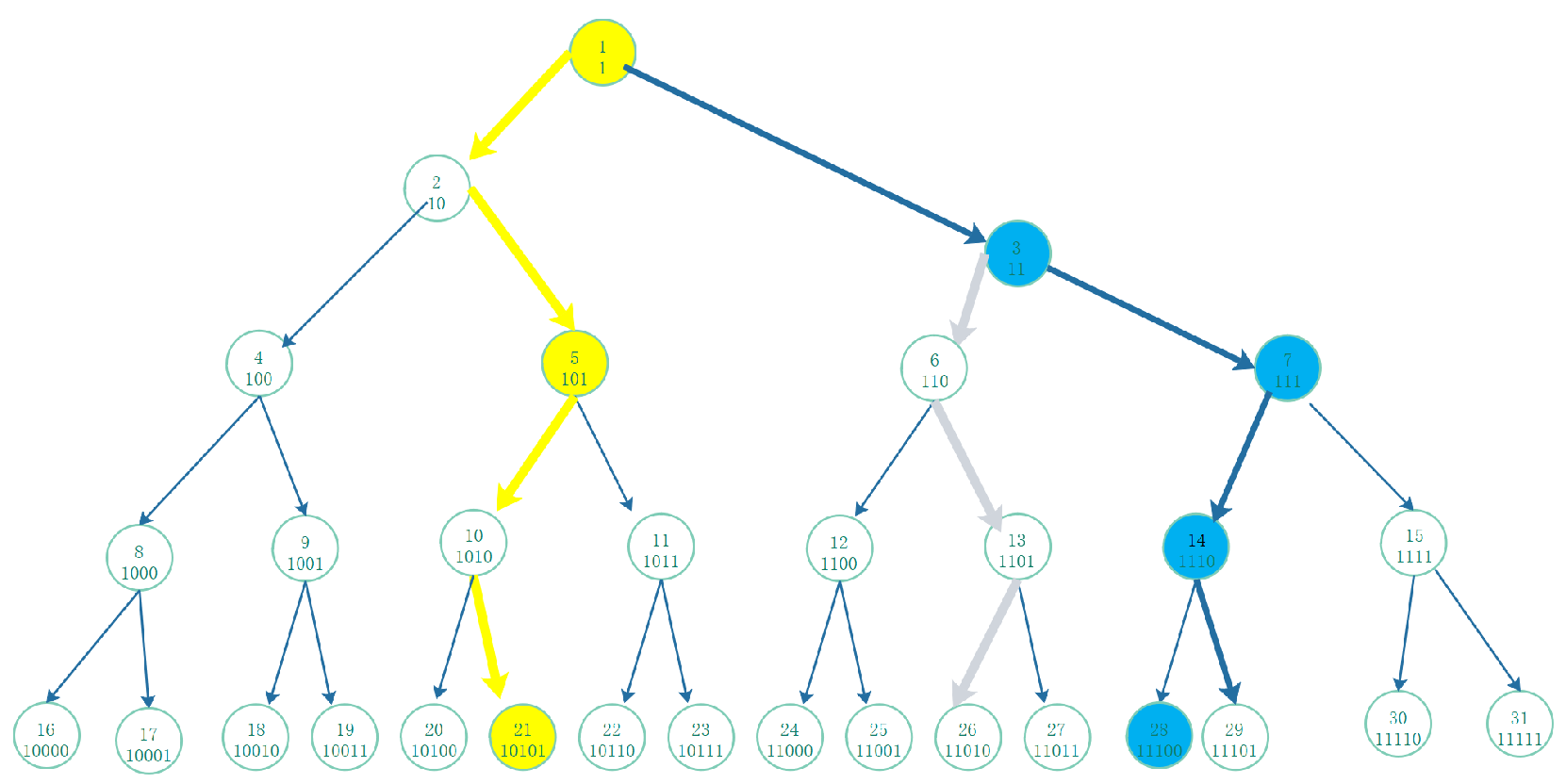

For given natural n, the iterative inverse formula apply from two cases according party in the procedure. We can use an iterative method to search for the backtracking path of its parent node’s natural tree, and eventually we will definitely return to its root node 1.

3.2. The Collatz Function and the Iterative Collatz Function

As the Collatz function

(1), we can get the result about the

and

The iteration of the Collatz function is the key topic in discuss the proof procedure. The iterative process of the Collatz function, where k is the number of bits of the last substring of the binary string of n. When n is an odd number, although the value is increased by 1.5 times when expressed in binary form, we find that every time the Collatz function is applied twice, that is , although it increases by approximately 1.5 times, the length of the trailing substring will decrease by one bit with each iteration. When the length of the trailing substring is 1, the subsequent operation must be , and the result must have . Then, we continue to repeat the case of odd numbers. The trailing substring of the binary string of must either be a single digit or a certain finite number of digits.

Thus, we have identified the root causes of the increase and decrease in the Collatz iteration sequence: We have discovered that the process of increase is finite, while the number of decreases, although relatively small, has a significant effect.

There are many different points for piecewise functions when comparing the Collatz function with the inverse function , and the some iterative Collatz function with the inverse function iteration .

1) For any natural number x function and are strictly monotonically decreasing.

2) The function is increasing in the case x is an odd, in the other case, is decreasing.

3) The function

that describes the procedure of the iterative function of

, is wavy when

x is a pure or mixed odd number and decreases when

x is pure even or mixed even.

|

|

|

|

|

… |

|

|

|

|

|

… |

|

↓ |

|

|

|

… |

|

|

|

|

|

… |

|

|

|

|

|

… |

|

|

|

|

|

… |

|

|

|

|

|

… |

|

|

|

|

|

… |

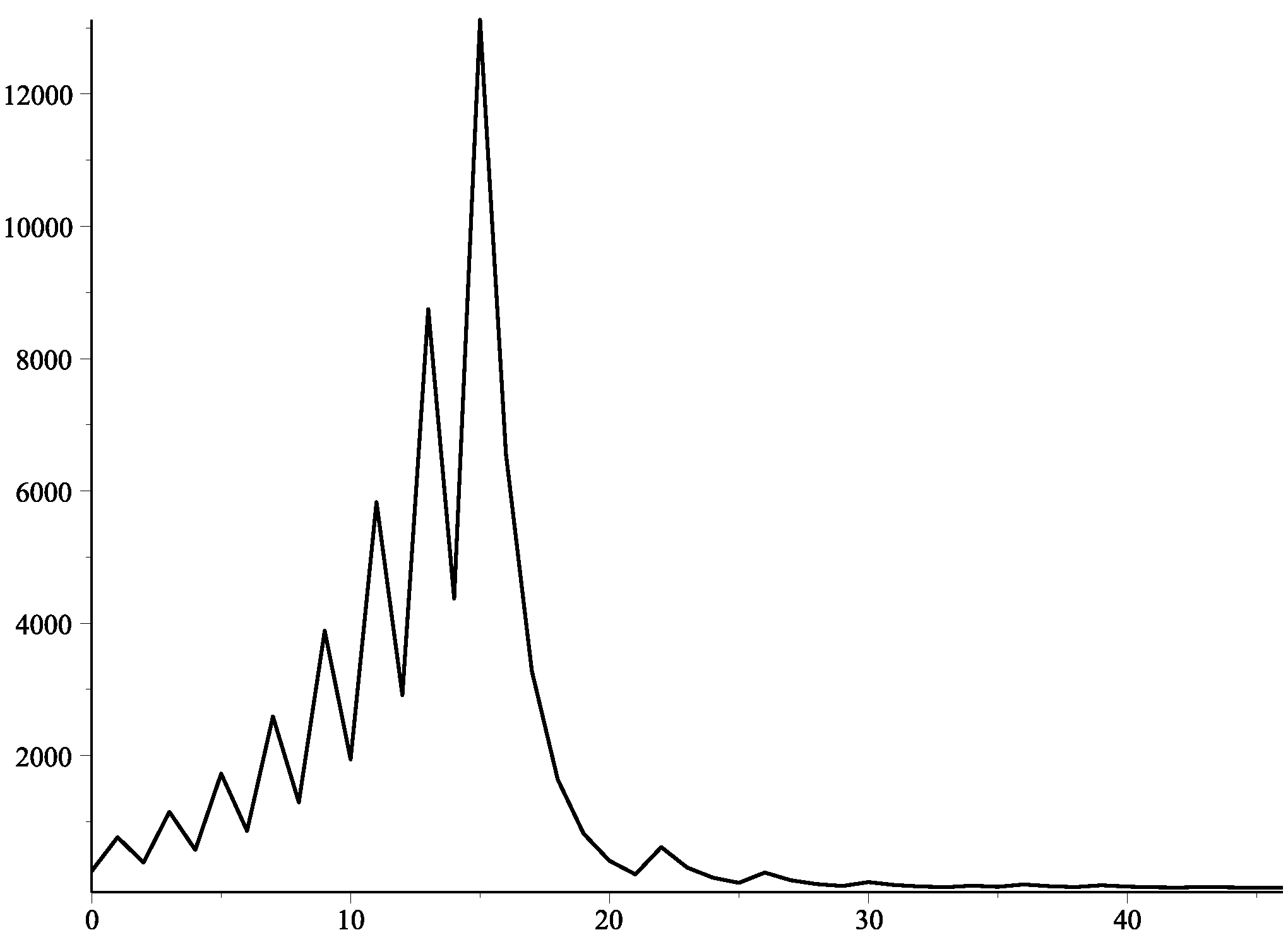

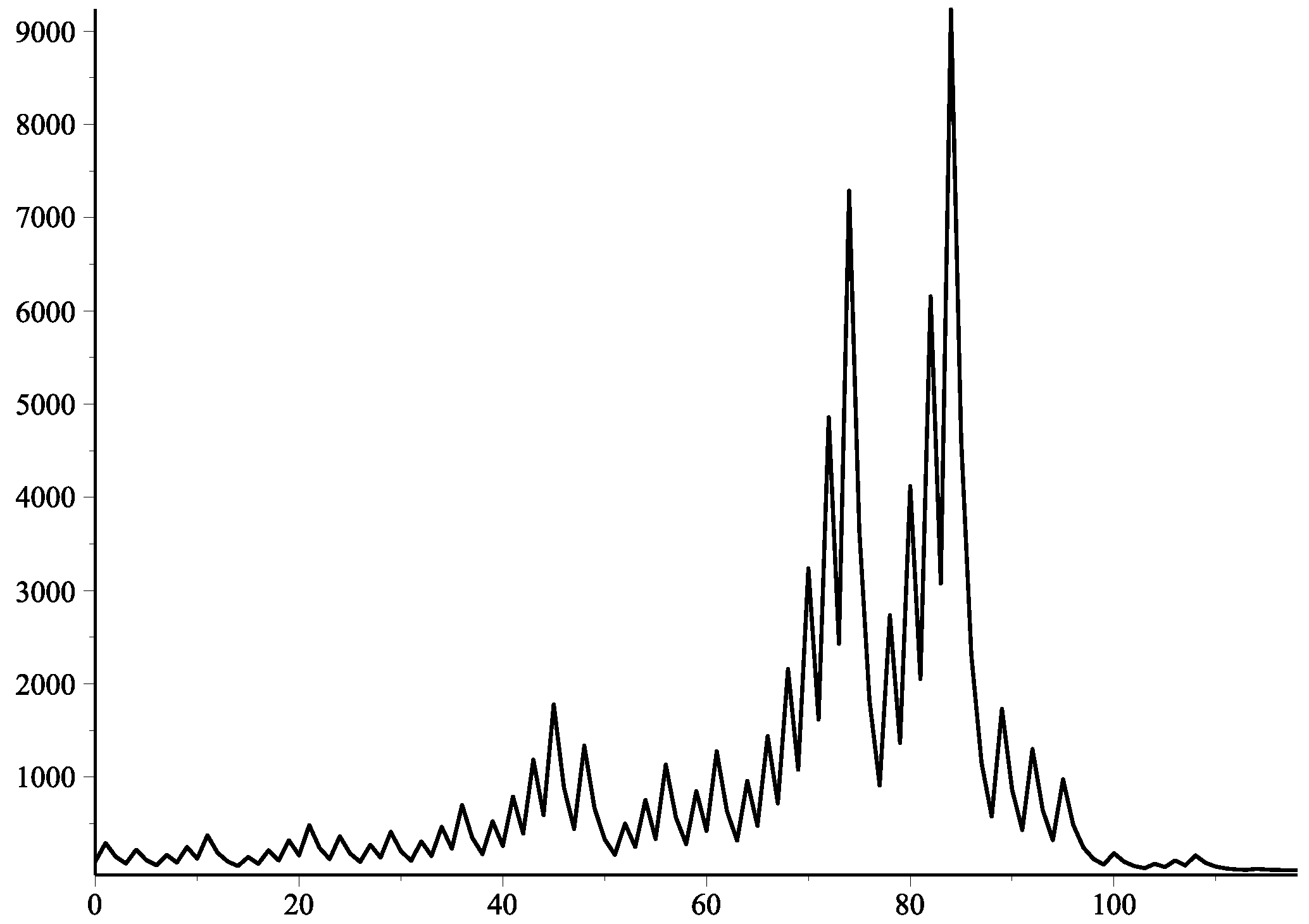

The function

describes the iterative procedure of

. The wavy function is increasing at first, then goes through one or more decreasing processes, either as "increase – decrease – increase" or "increase – decrease … decrease – increase." For example, the iterated sequence of Collatz functions is plotted in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, where the starting values are pure odd

and mixed odd numbers

, respectively.

For a given natural number n, the Collatz iterative function converges to 1 in a finite number of steps and cycles indefinitely between numbers 1, 4, and 2 for an infinite number of iterations.

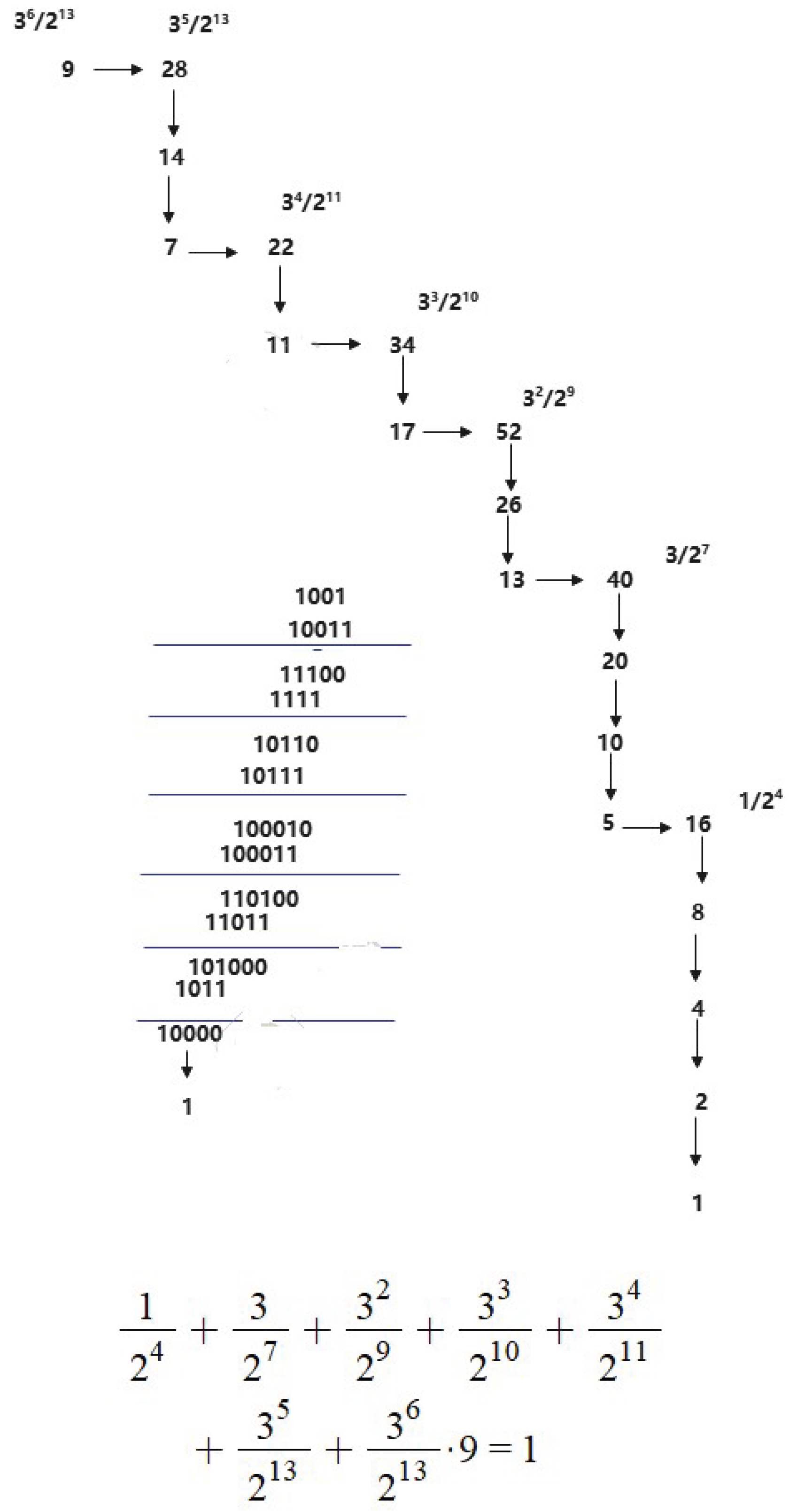

The iterative process of the Collatz function, the expression form of

is: the numerator is a power of 3, and the denominator is the sum of powers of 2. The power of 3 in the numerator increases successively from 1 to a certain value, while the power of 2 in the numerator sometimes increases continuously and sometimes jumps. For example,

, where 6 times

and 13 times

, the algebra expression in

Figure 7:

.

3.3. Using Binary String to Explore the Collatz Conjecture

In the book [8] authors look at the radix 2 representations of

n and

to solve the Josephus problem. Suppose the binary expansion is

where each

is either 0 or 1 and where the leading bit

is 1. When

, there are

If we start with n and iterate the J function times, we are doing one-bit cyclic shifts and delete 0 in the leading bit.

We use the binary string of the natural number

n to proceed the iteration of Collatz function

for odd number

n as the followig procedure

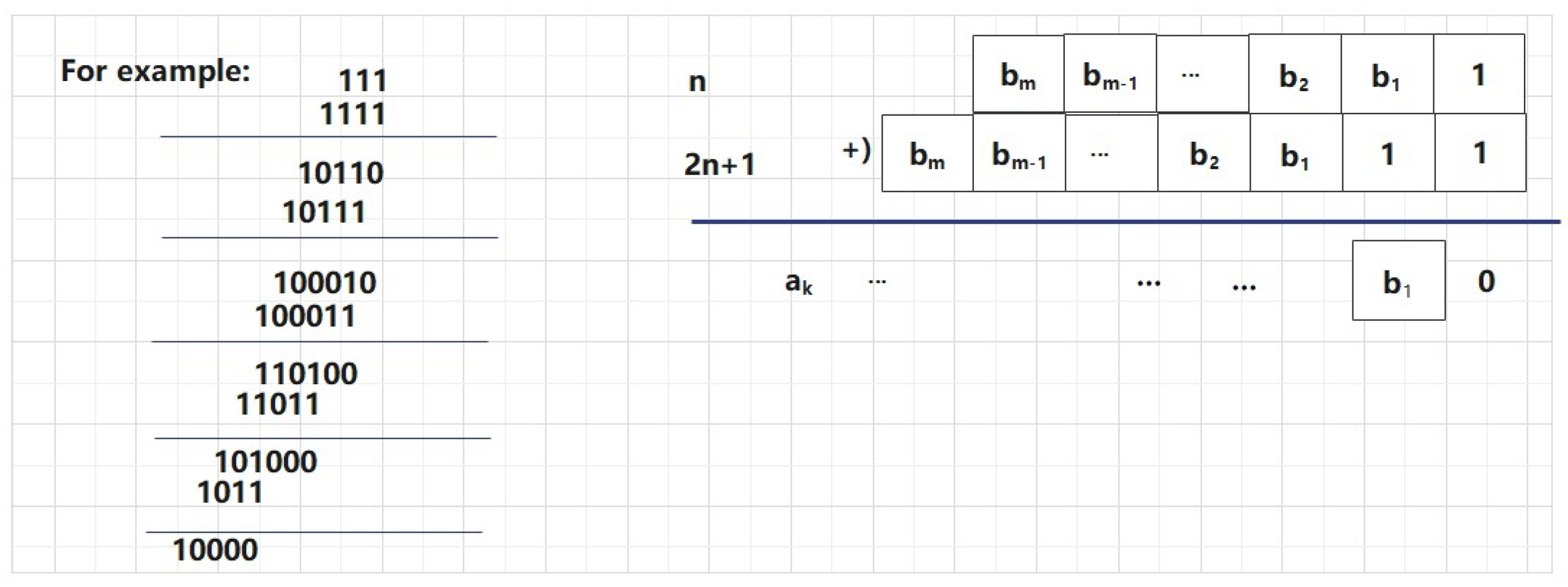

Key point 1 We find that for odd number , the Collatz iteration reduces the length of the substring is reduced by one, the number of additional bits in the left side of the binary string does not exceed one. The value , this is the key in the series of the Collatz iteration.

Key point 2 After some iteration when the length of the substring is one, the binary string must end with at least two zeros, this results that there is where and the value , this is the key in the series of the Collatz iteration. The length of the substring in the odd number’s binary string, is either 1 or r.

Key point 3 If

n is an even number, i.e. a mixed even number, which end-substring has

r zero, the iteration of Collatz function

is deleting all

m zeros at the end of the binary string.

As we know that for

n is an even number, the parity of

is uncertain, it is either even or odd. For

n is an odd number, the parity of

is certain, it is an even number. If we start with

n and do some iterations of the

T function some times, choice the next function from

and

according the parity of

. After shifting the binary string one bit to the left sequentially, fill the empty positions with 1s. For the example in Figure 9, the scratch paper of the sequence of

Figure 6.

The scratch paper of the sequence of

Figure 6.

The scratch paper of the sequence of

In the iterate squence

, for

, if its length of the end-substring in the binary string is

h which is bigger 1, then for the next odd number

, its length of the end-substring is

. then there is a relation

For the general, we can get an algebraic expression. For example, there are

We adopt the binary representation method for specific natural numbers and use mathematical experimental methods to obtain their Collatz sequences. The following are three kinds forms to describe the Collatz sequences respectively: (i)algebra expression, (ii)tabular, and (iii)scratch paper. We use the binary representation method for specific natural numbers and employ mathematical experimental techniques to generate their Collatz sequences. The Collatz sequences for the numbers are presented in three different formats:

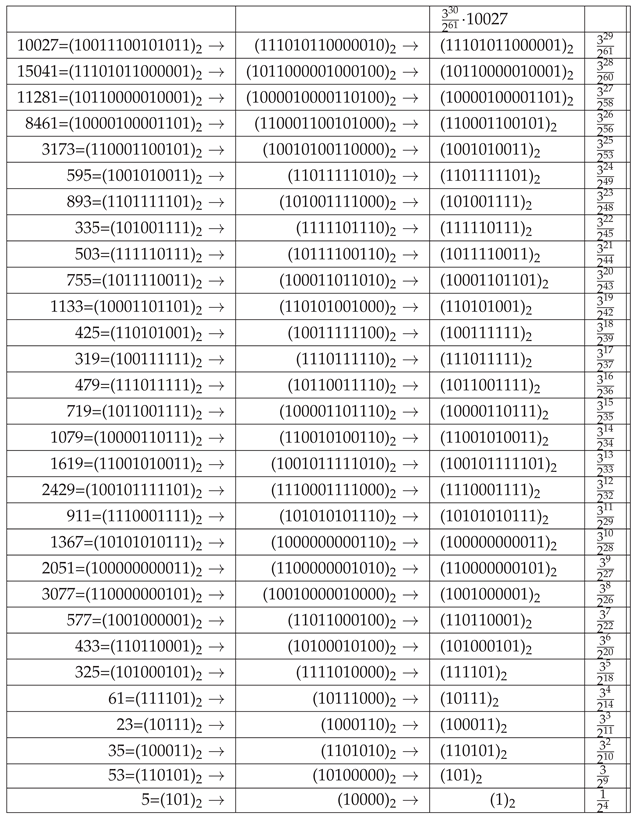

(A) For the formula , we apply the mathematical software Maple get the sequence are algebra expression, and in decimal and binary as the follows.

(B) For the formula

, we get the sequence

are in decimal and binary as the following scratch paper as in

Figure 7. The horizontal arrow line means the 3n+1 operation, and Vertical arrow line meams the n/2 operation. There 6

denoted by

where

, and 13

by

where

in algebra expression.

Figure 7.

The scratch paper of a sequence of 9 iterations of the Collatz function for odd 9 in decimal and binary forms, and its algebra expression.

Figure 7.

The scratch paper of a sequence of 9 iterations of the Collatz function for odd 9 in decimal and binary forms, and its algebra expression.

We observe the procedure of iterative Collatz function, namely the reduced Collatz function (7), i.e., the Collatz sequences, which we pay close attention to the zeros in the right-hand side of binary strings of an even number and the end-substring between the first 0 encountered from right to left which is made of 1. For instance, for 1011001 the end-substring is 1, for 1011001111 the end-substring is 1111, for 11111 the end-substring is itself 11111. There are many properties of the end substrings.

In the Collatz sequence represented by a binary string looking backward from 9:

(1) If there are several zeros at the end, remove one at a time until all zeros are deleted, and the number becomes an odd, namely , and in the algebra expression .

(2) When the number of bits at the end-substring is , the adjacent binary string must have only a single zero at the end. Remove this zero to make it the next odd number, and the number of bits at the end-substring is , continues these steps until only a 1 is left at the end. Namely, , …, and in the algebra expression .

(3) If the number of digits at the end-substring is only one, the adjacent binary string must end with several zeros. Deleting these zeros in sequence will result in the following two scenarios at the end of the binary string:

(i) When the length of the end-substring is one bit 1, then the adjacent Collatz sequent is , where , accordingly the Collatz sequent is decrease.

(ii) when the length of the end-substring is more than one bit 1, then the adjacent Collatz sequent is , accordingly the Collatz sequent is increase.

From this, we can obtain the following result: For any positive odd number, the number of bits in the trailing substring of its binary representation is necessarily finite, and thus the increasing process in its Collatz sequence is also finite. After several increments, it will eventually decrease.

3.4. Bezout Identity and Its Extension

In order to explain the algebraic expression, we associate with Bezouts identity, a fundamental theorem in number theory established by Etienne Bezout in 1779. Bezout’s Identity, also known as Bezout’s Lemma, is a fundamental theorem in number theory that describes a linear relationship between the greatest common divisor (GCD) of two integers and the integers themselves.

Bezout’s Identity (Bezout’s lemma) states that for any two integers

a and

b, there exists

x and

y such that:

where

is the greatest common divisor of

a and

b.

The extension of the Bezout identity is stated as the following, For some integers

, if

, then there are infinite many integers

such that

For , there are positive integers , such that , , and .

We get another extension of Bezout identity as the following:

Another extension of Bezout identity: For some natural

n, there are two natural numbers

m and

q, such that there is a linear combination expression of

and vector

and

.

Namely, there is the algebraic expression

which is dividing the left side of the equation by the right side. For example, the above algebraic expressions,

,

,

and

.