6. Discussion

6.1. Effectiveness of Wavelength Selection

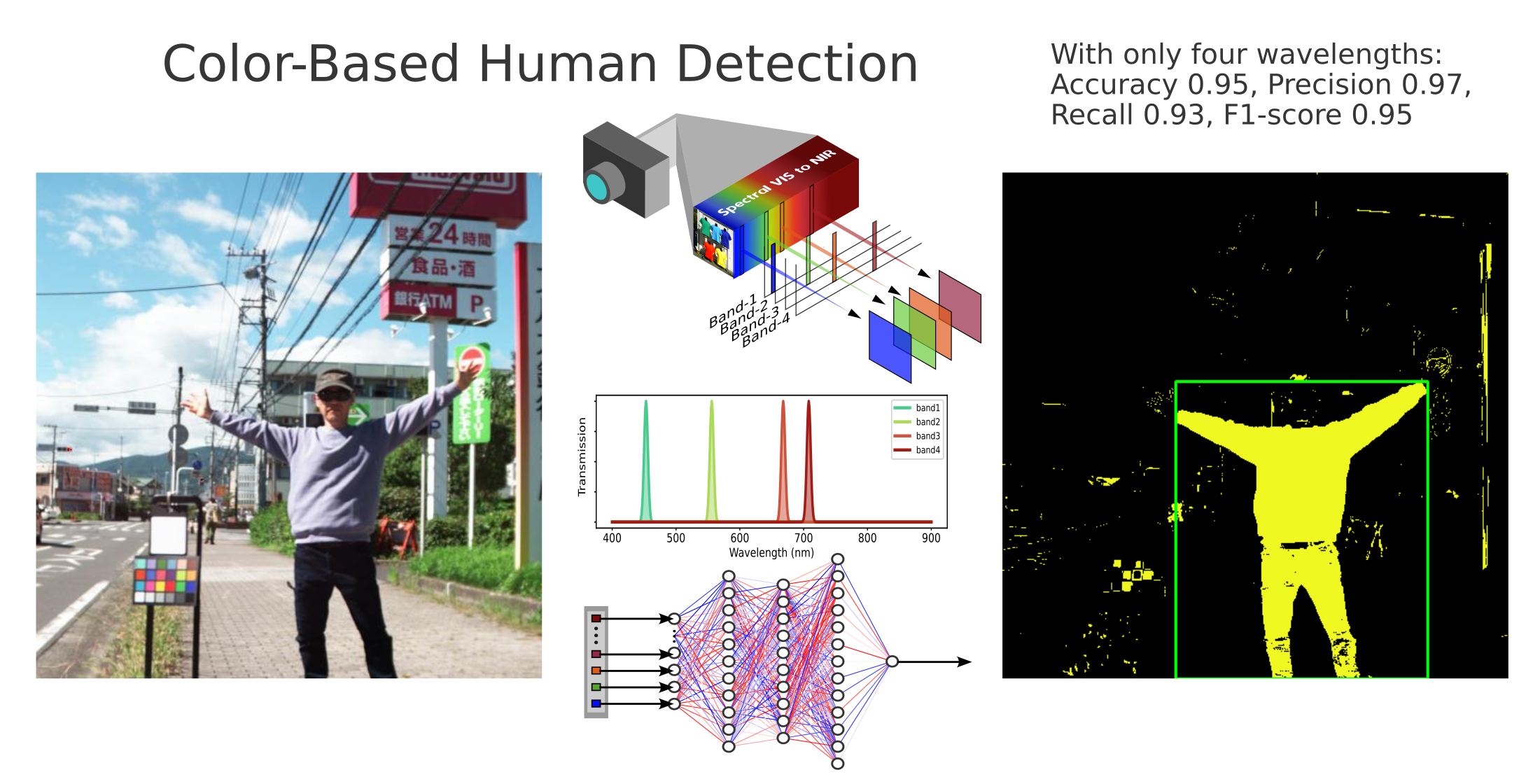

The results indicate that, by selecting four wavelengths spanning the visible to near-infrared region, clothing detection is feasible to some extent. Using only four bands instead of the full spectrum simplifies the camera system and offers advantages for real-time capability.

Tests confirmed that using only the visible range or only the near-infrared was insufficient. Employing both visible and near-infrared wavelengths together proved critical. In other words, adding near-infrared to visible bands improved detection performance over visible-only approaches.

6.2. Effectiveness of Each Wavelength

Why are these four specific wavelengths so effective? Here, we consider the physical and spectral background. We hypothesize the roles of the four bands in OWS4-1 as follows:

-

Fourth Wavelength: Capturing “many garments”

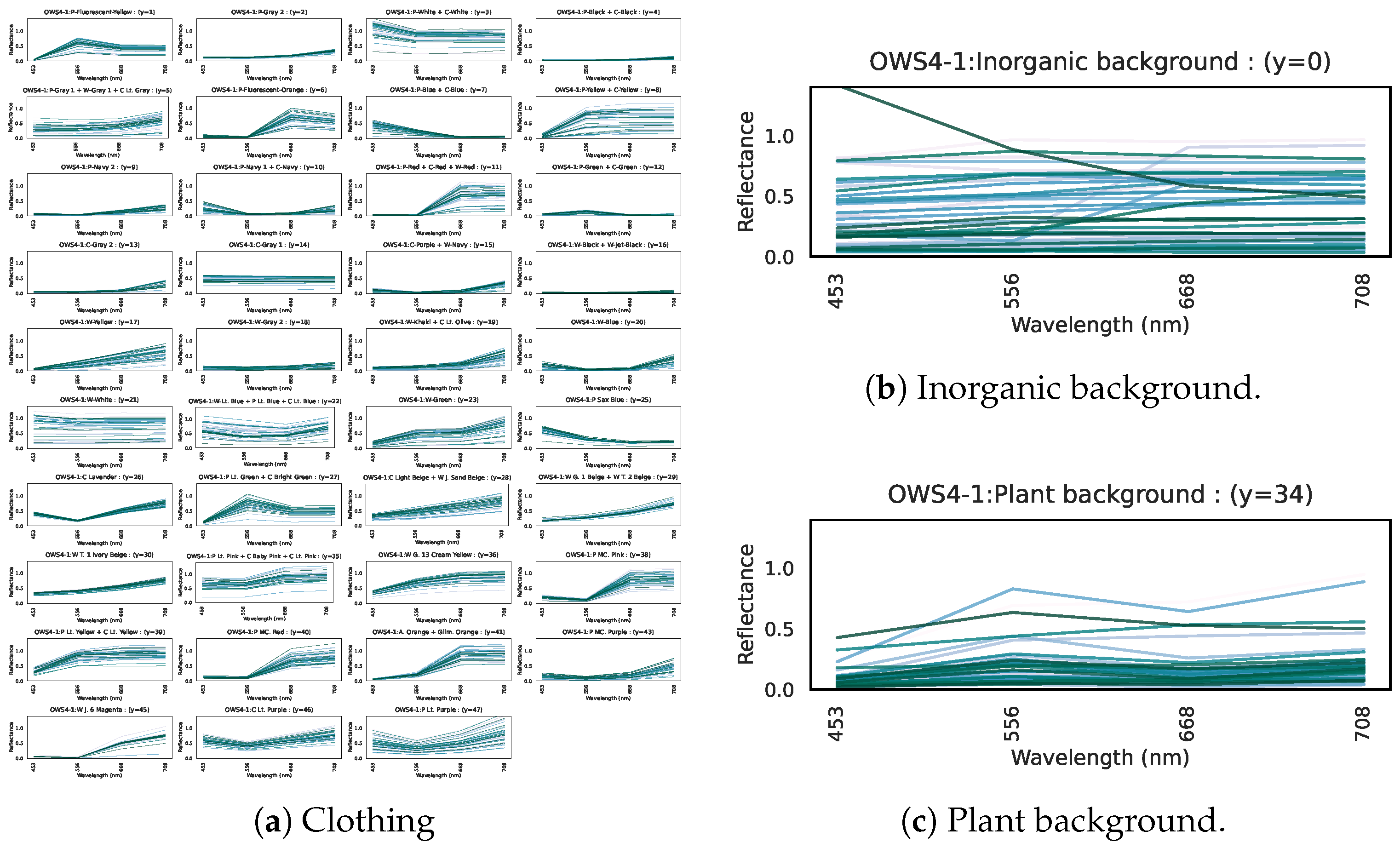

As shown in

Figure 14, the majority of clothing (32 labels) exhibits high reflectance in the 4th wavelength. This band captures the high near-infrared reflectance of most clothing, consistent with our hypothesis that fibers/dyes often reflect well in the near infrared. In addition, combining this band with the second or third bands is helpful for identifying particular clothing colors.

-

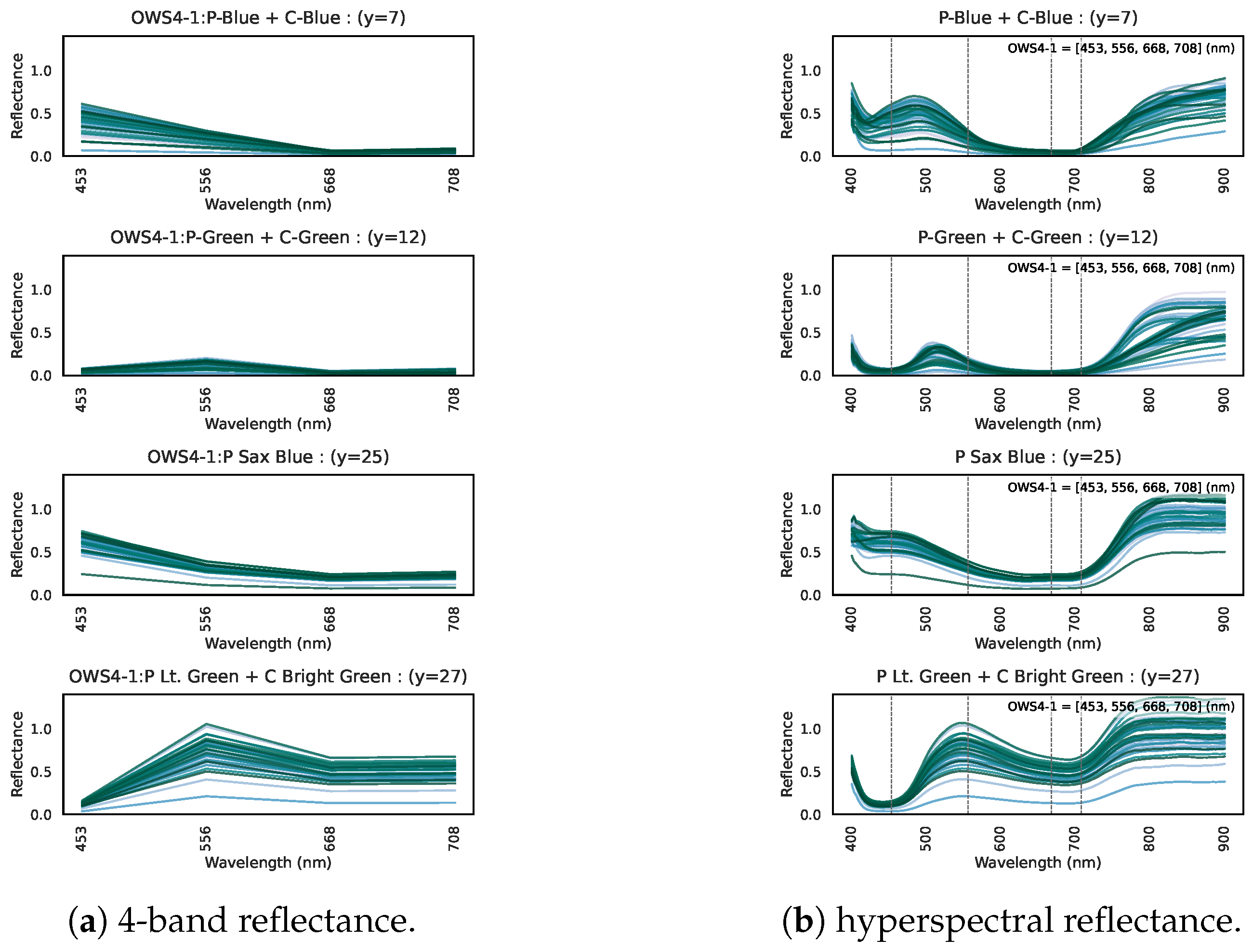

Combination of Second, Third, and Fourth Wavelengths: Distinguishing “green/blue clothing” from vegetation

The second and third wavelengths alone do not appear to capture any single specific physical property. We infer that the reflectance pattern across these three bands (including the fourth) helps discriminate certain colors. For instance, the clothes labeled “P-Blue + C-Blue,” “P-Green + C-Green,” “P Sax Blue,” and “P Lt. Green + C Bright Green” have low reflectance at the 4th band.

Figure 27(a) shows their 4-band reflectance, all satisfying 2nd band > 3rd band = 4th band. However, the hyperspectral curves in

Figure 27(b) reveal that these green/blue garment curves do rise sharply beyond 708 nm. Because the 4th band (708 nm) is slightly short of the near-infrared region where reflection spikes, these garments appear to have lower reflectance at that band.

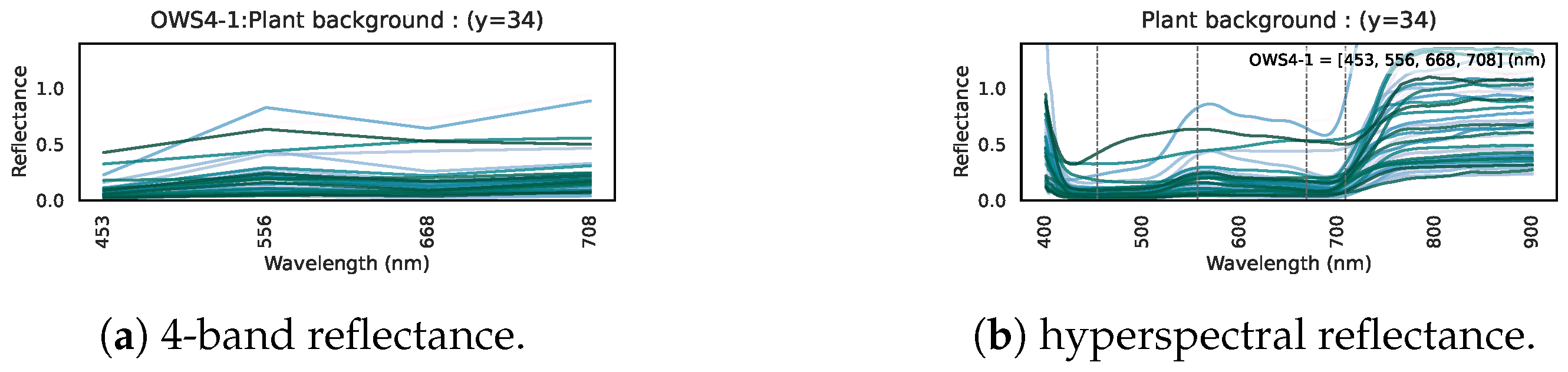

However, vegetation that looks similarly green to the human eye shows 2nd band > 3rd band < 4th band, as indicated by

Figure 28. Comparison of

Figure 27(b) and

Figure 28(b) indicates that vegetation transitions to high near-infrared reflectance at a slightly shorter wavelength than does green clothing. Hence, the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th wavelengths together capture this difference in the onset of near-infrared reflectance, allowing the model to distinguish green clothing from plants.

-

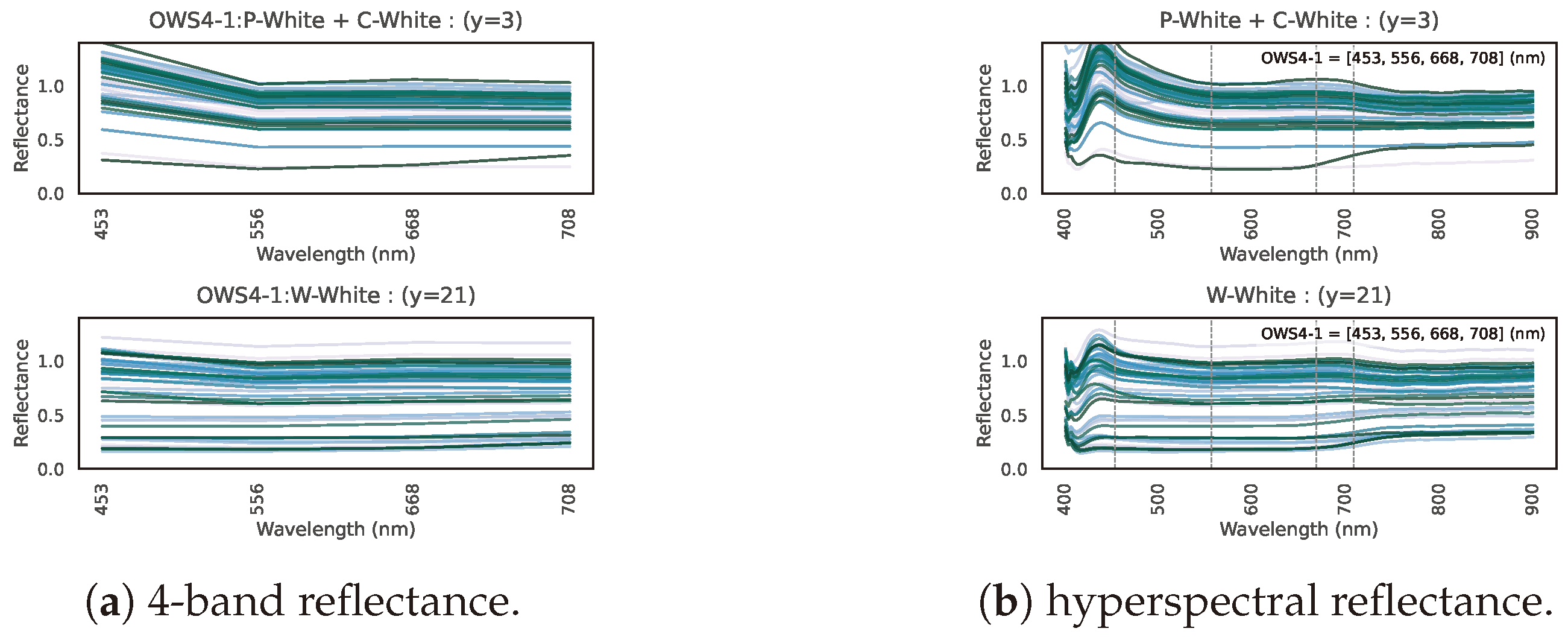

First Wavelength: Capturing “white clothing”

In

Figure 29, we show (a) the 4-band reflectance and (b) the hyperspectral reflectance of white polyester/cotton garments (“P-White + C-White”). Their reflectance is very high (above 1.0) at the first band, likely due to fluorescent brighteners used in white fabric dyes [

36,

37,

38]. Hence, the first wavelength is effective for capturing the high reflectance of P+C whites. White wool (“W-White”) may likewise incorporate fluorescent brighteners, as evidenced by a peak at approximately 440 nm in the 167-band data. However, the peak wavelength of these brighteners (

nm) inferred from the spectral curves does not fully coincide with the first wavelength (453 nm). This discrepancy suggests that the convergence approach employed in this study will benefit from further refinement.

6.3. Limitations of Spectral-Only Detection: Counterexamples of Hypothesis, Materials, Nighttime, and Red/Yellow

Counterexamples to the Hypothesis:Uncolored wool or gray cotton that does not increase near-infrared reflectance is easily missed. Nude bodies are not considered.

Material Constraints:Leather or synthetic leather that does not reflect well in the near-infrared cannot be detected. Military camouflage clothing [

39] or materials that are difficult to see even with the naked eye are beyond the scope of this method.

Nighttime or Low-Light Environments:Our experiments assume outdoor daytime conditions. Nighttime use would require external infrared illumination. Because spectral distributions change drastically under different lighting, our approach cannot be directly applied.

Red or Yellow Background: If these colors have spectral properties similar to that of clothing, false positives may occur.

Possible countermeasures include (1) collecting extra training data emphasizing these challenging garments, or (2) introducing a hybrid method that combines spectral data with spatial pattern features such as texture or shape. However, adding more challenging clothing might also increase false positives for similar backgrounds. Also, incorporating spatial pattern recognition can increase the computational demand, undermining the speed advantages of a purely spectral approach.

Hence, we consider it reasonable to “give up” in cases where the material does not satisfy the “fiber high near-infrared reflectance” assumption or where background objects share very similar spectra. In this research, we deliberately focused on the scenario of daytime outdoor people wearing normal fiber garments, which yields high recall within that domain.

To our knowledge, there is no clear statistical data confirming that most people in public areas wear textile garments, but in urban environments, this is generally true. Therefore, treating clothing detection as an approximation of human detection is likely to have sufficient merit.

6.4. Prospects for MLP Model Generalization

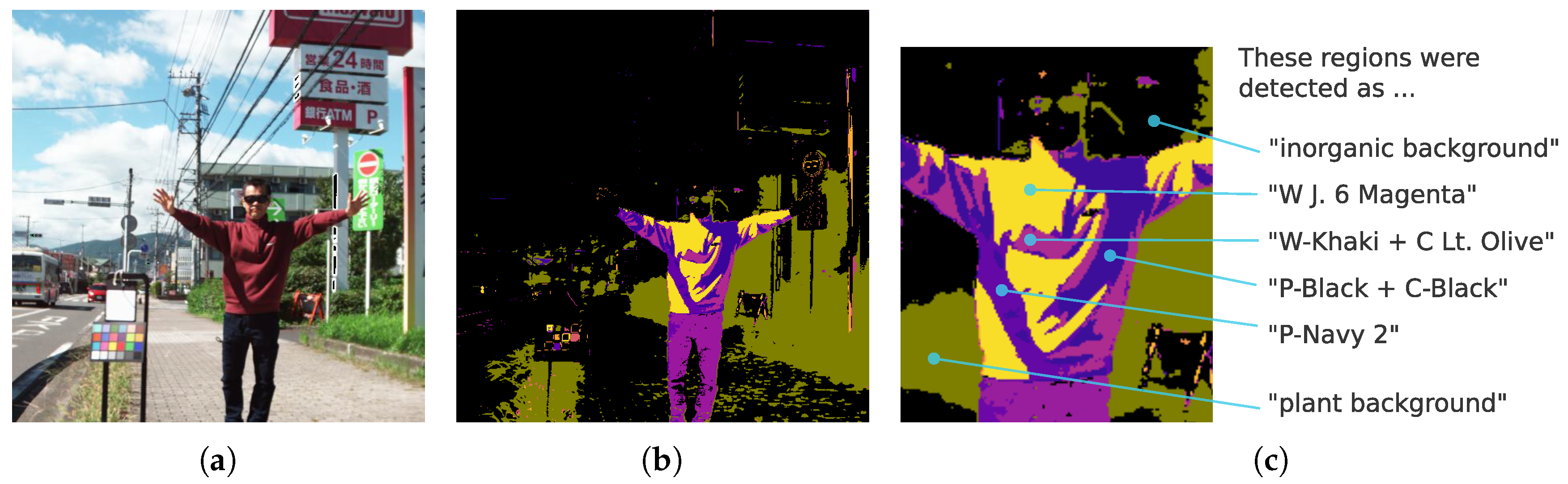

The dataset of hyperspectral images used in this study was limited, covering only daytime outdoor environments and a modest number of test images. Nighttime or highly dynamic situations have not been evaluated. Even so, the real-image results in

Section 5 suggest some degree of generalization: the model detected clothing that was not part of the training.

Going forward, we must clarify the range of scenarios for which the “clothing hypothesis” is valid. A much larger dataset spanning various locations, times, weather conditions, and urban/rural settings will be needed to further assess the generality of clothing detection. With sufficient data from large-scale experiments, we can gain deeper insight into how broadly the method applies.

Because a still-image hyperspectral camera makes large-scale data collection difficult, we plan to use a smaller, video-capable spectral camera to capture diverse scenes and subjects continuously, thus enriching the training data.

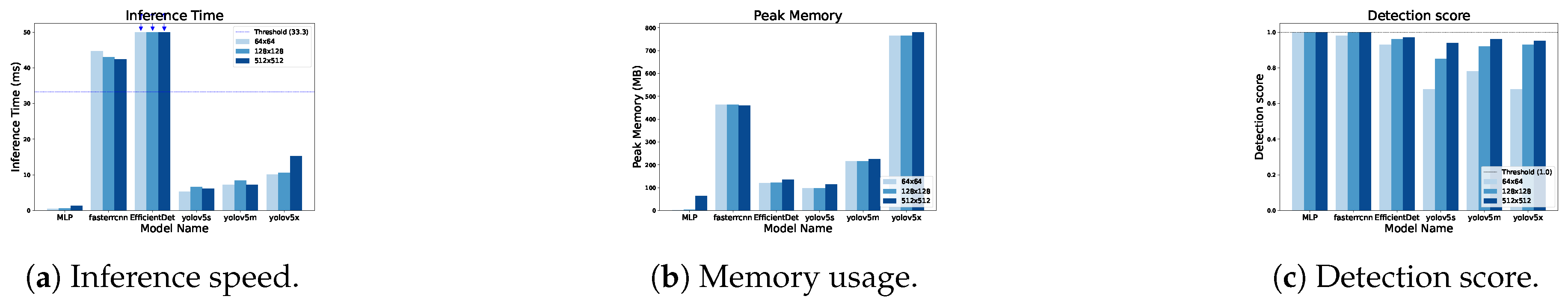

6.5. Outlook for a Real-Time Camera System

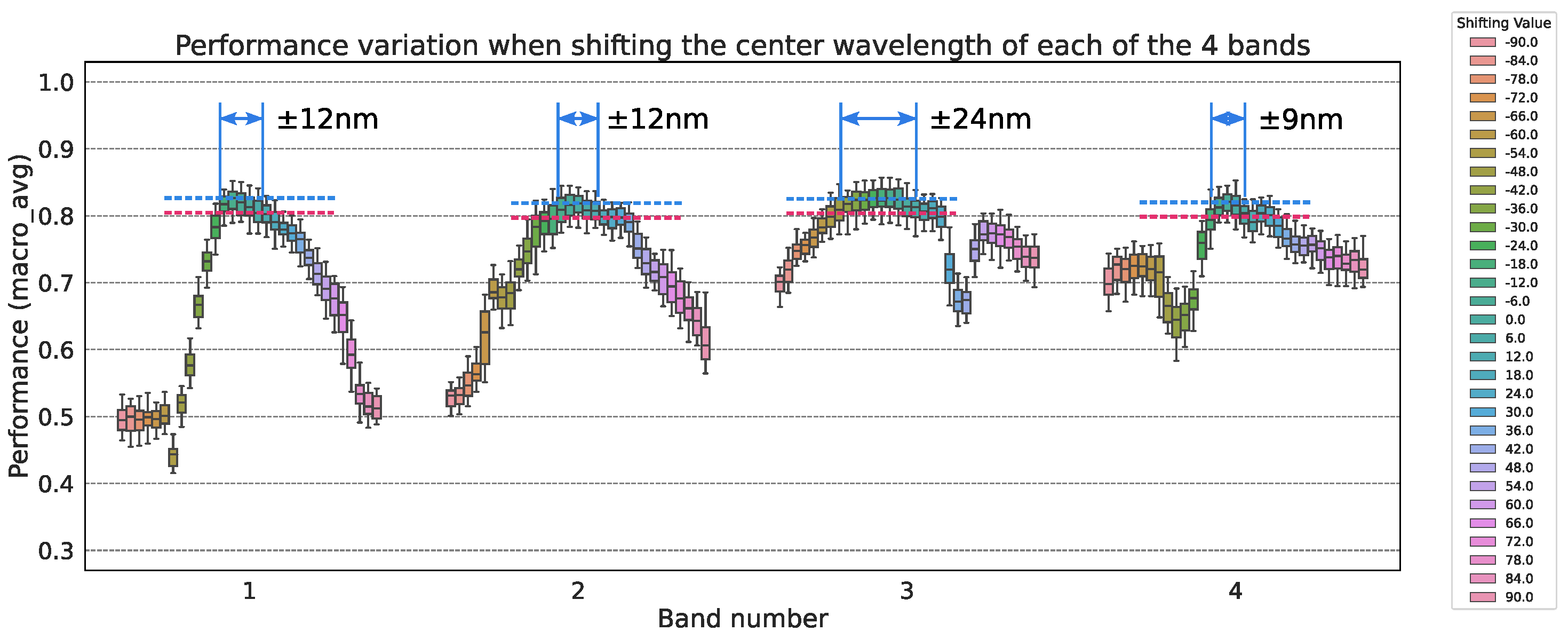

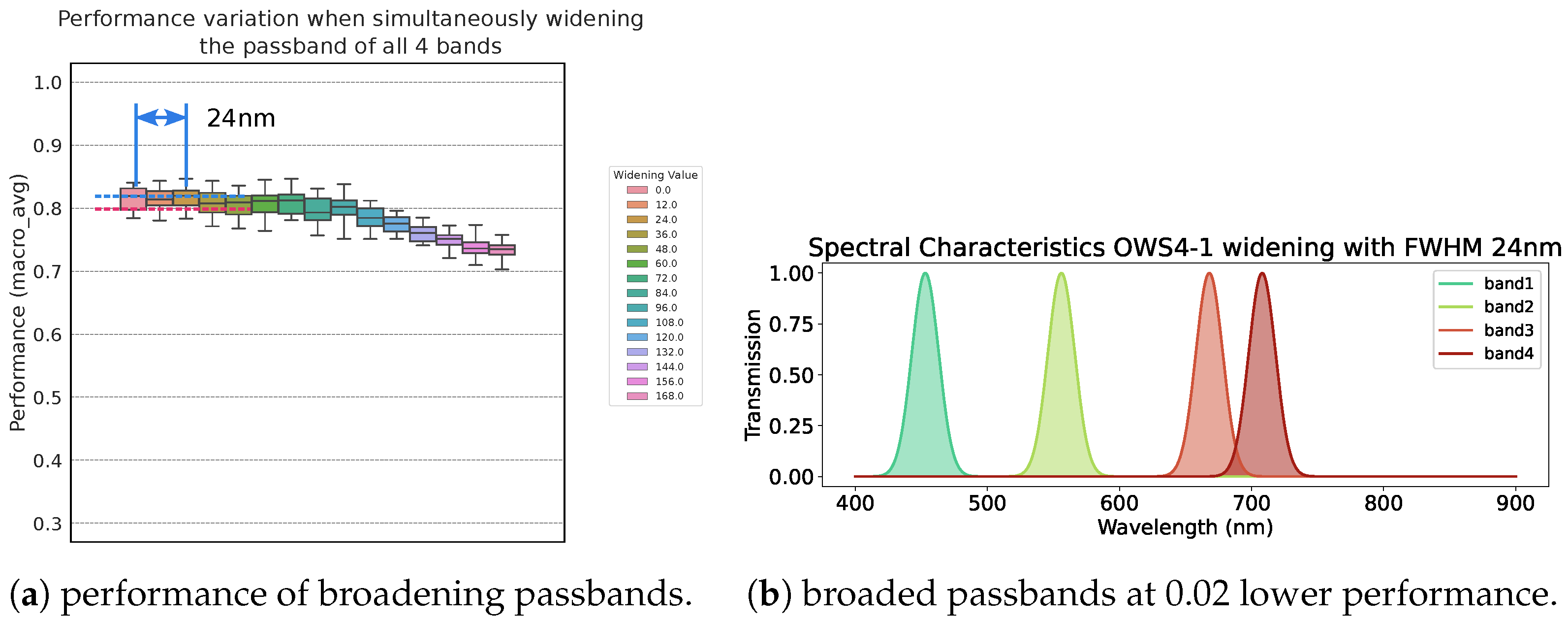

The MLP approach offers fast, memory-efficient inference, suitable for IoT devices or compact cameras. Using only four bands reduces the complexity compared to high-end systems with many bands. From the robustness evaluation in

Section 4-3-3, we can see that moderate variations in the center wavelength or passband width are tolerable, making it feasible to use off-the-shelf filters.

Small multispectral cameras with selectable wavelengths, such as polarization-based multispectral cameras [

40] or multi-lens TOMBO cameras [

41,

42,

43], can potentially be adapted to create a 4-band camera for human detection. In outdoor settings, however, illumination can vary by time and place, so we must address how to track or adapt to changing lighting conditions.

We plan to move forward with prototyping. Adapting to nighttime or indoor settings through infrared illumination or an improved sensor signal-to-noise ratio is a future challenge.

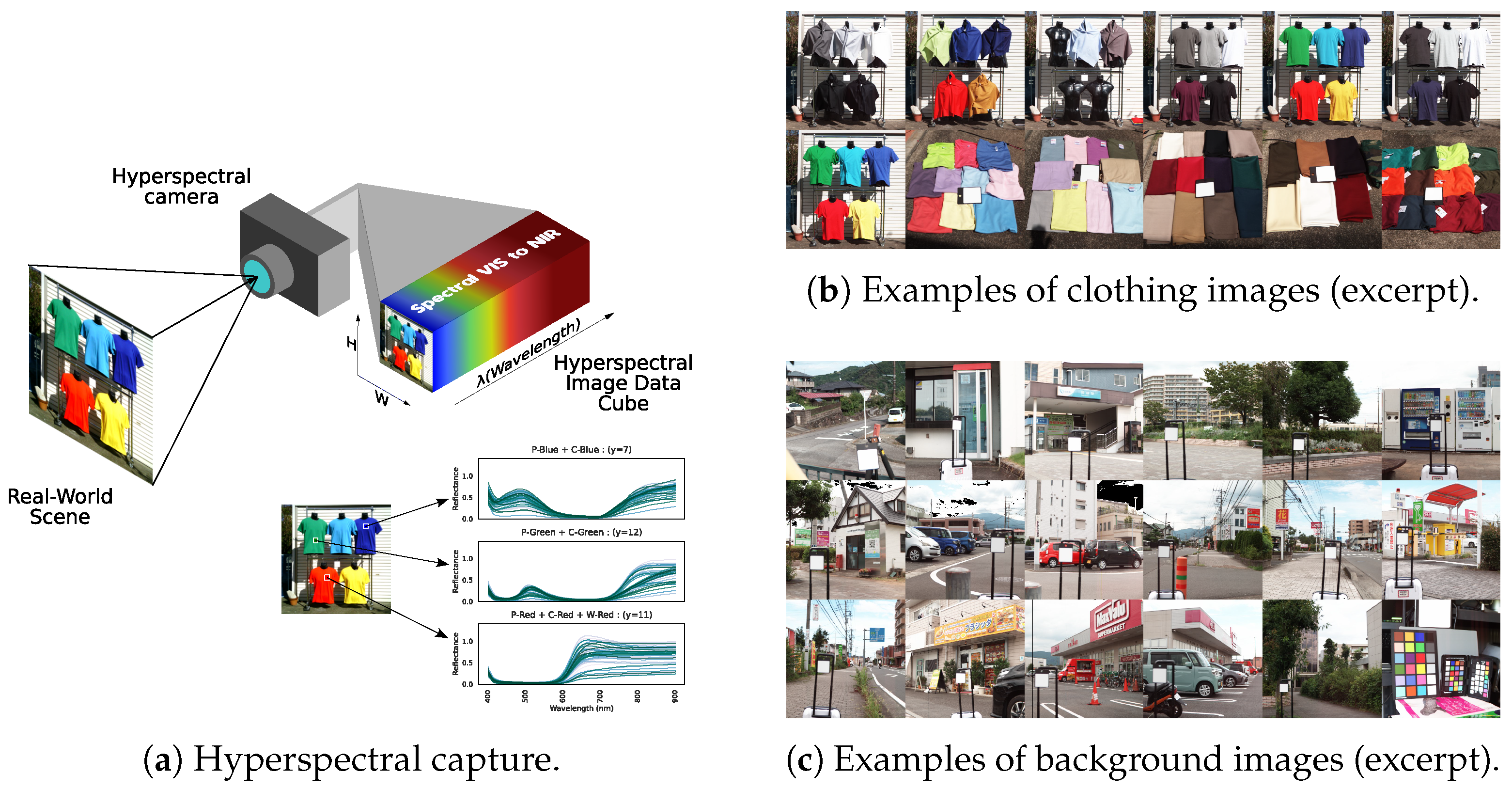

Figure 1.

Hyperspectral imaging of clothing and scenery. (a) Hyperspectral capture. (b) Examples of clothing images (excerpt). (c) Examples of background images (excerpt).

Figure 1.

Hyperspectral imaging of clothing and scenery. (a) Hyperspectral capture. (b) Examples of clothing images (excerpt). (c) Examples of background images (excerpt).

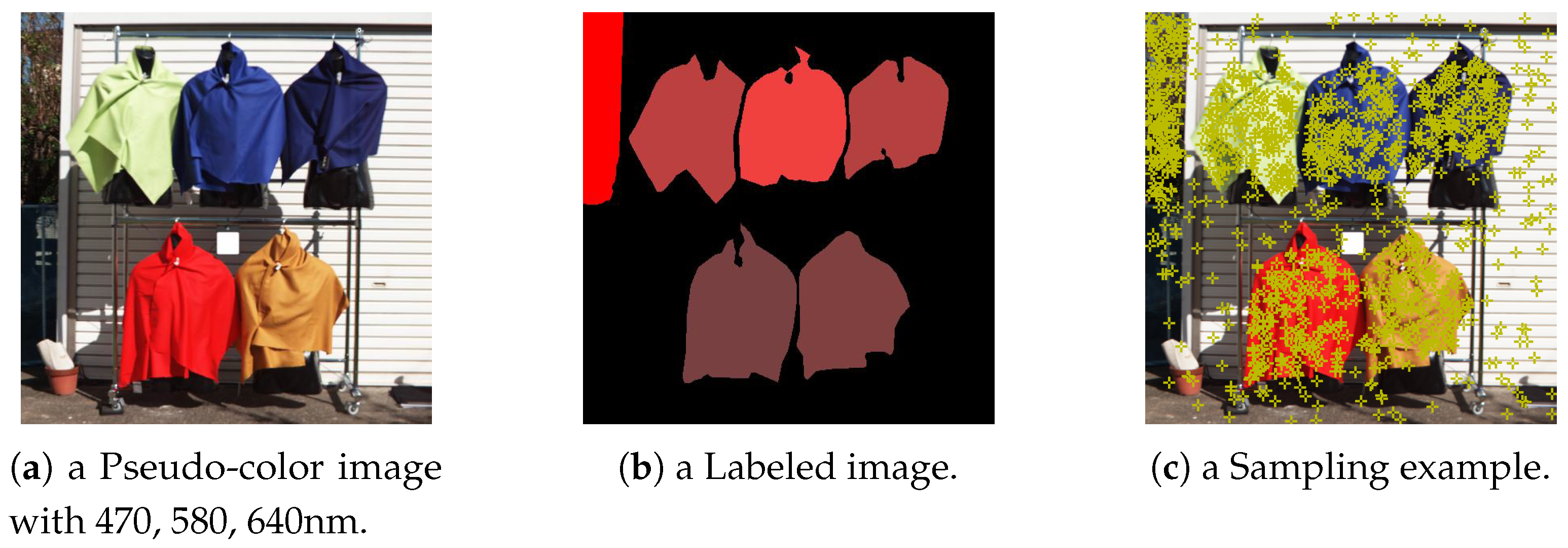

Figure 2.

Example of a labeled image (a) and its corresponding pseudo-color image (b).

Figure 2.

Example of a labeled image (a) and its corresponding pseudo-color image (b).

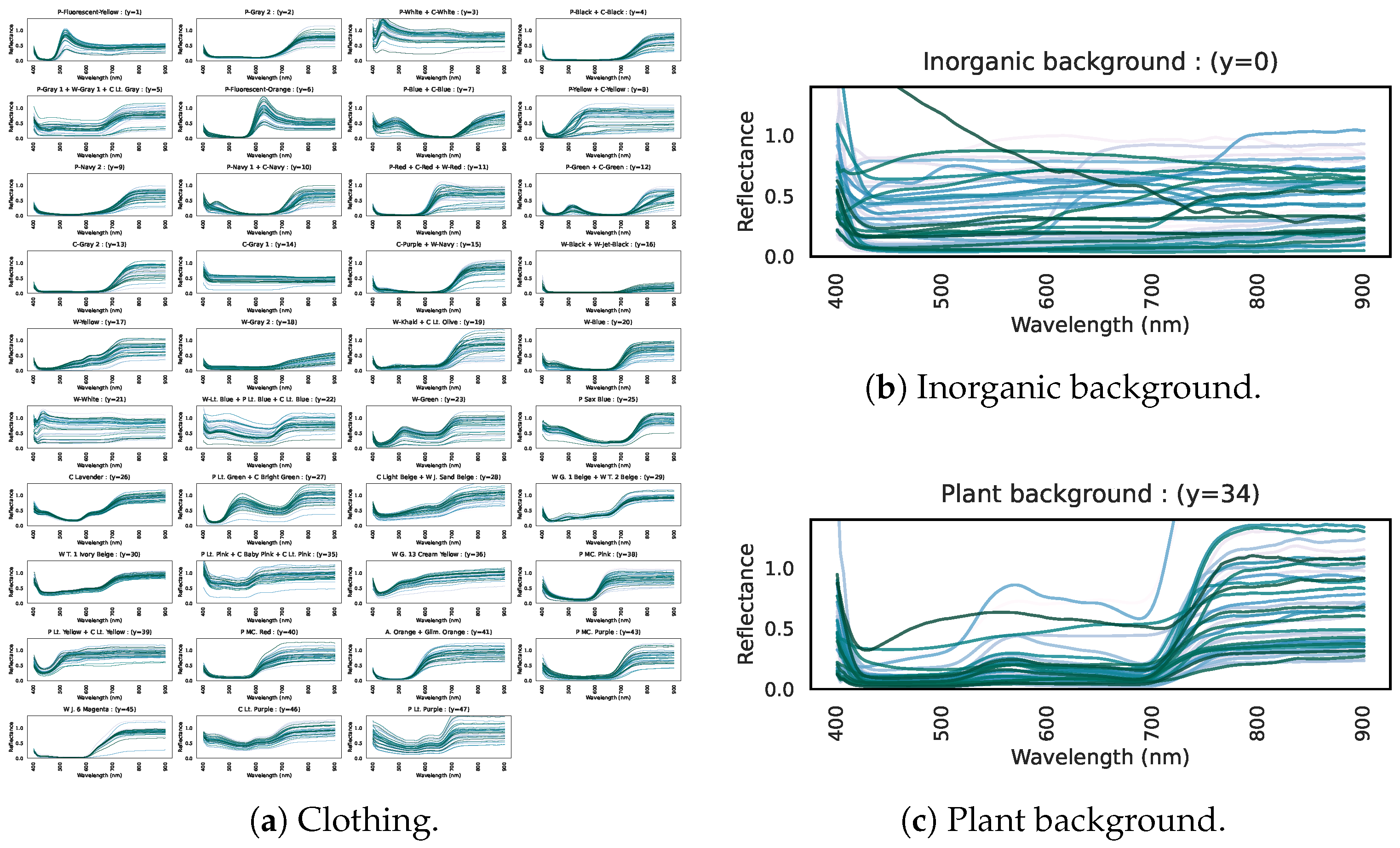

Figure 3.

Hyperspectral reflectance curves, showing reflectance (vertical axis) over the visible–near-infrared range (horizontal axis) for 100 samples. (a) Clothing. (b) Inorganic background. (c) Plant background.

Figure 3.

Hyperspectral reflectance curves, showing reflectance (vertical axis) over the visible–near-infrared range (horizontal axis) for 100 samples. (a) Clothing. (b) Inorganic background. (c) Plant background.

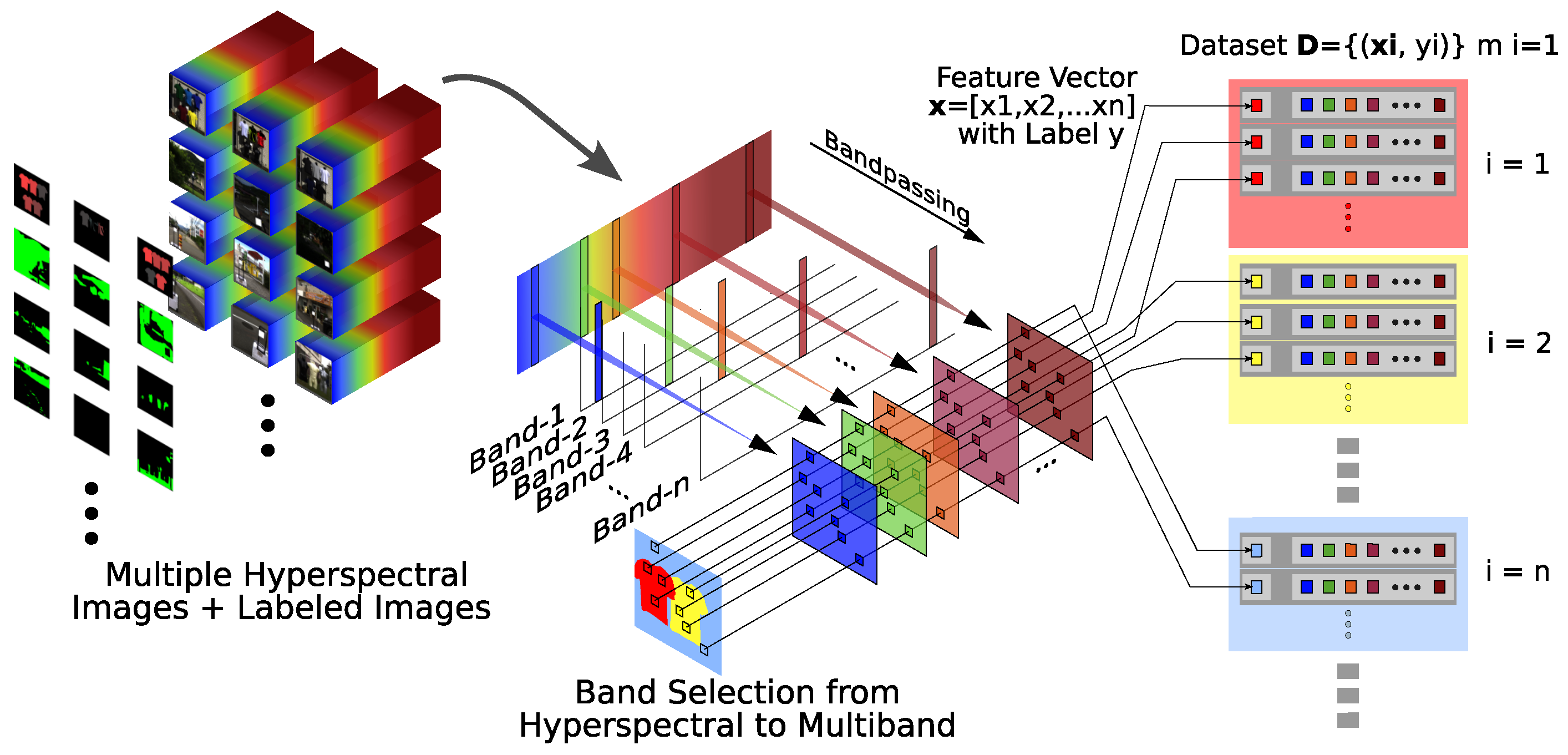

Figure 4.

Multi-Layer Perceptron dataset creation workflow.

Figure 4.

Multi-Layer Perceptron dataset creation workflow.

Figure 5.

Sampling example, with moss-green dots indicating chosen pixels.

Figure 5.

Sampling example, with moss-green dots indicating chosen pixels.

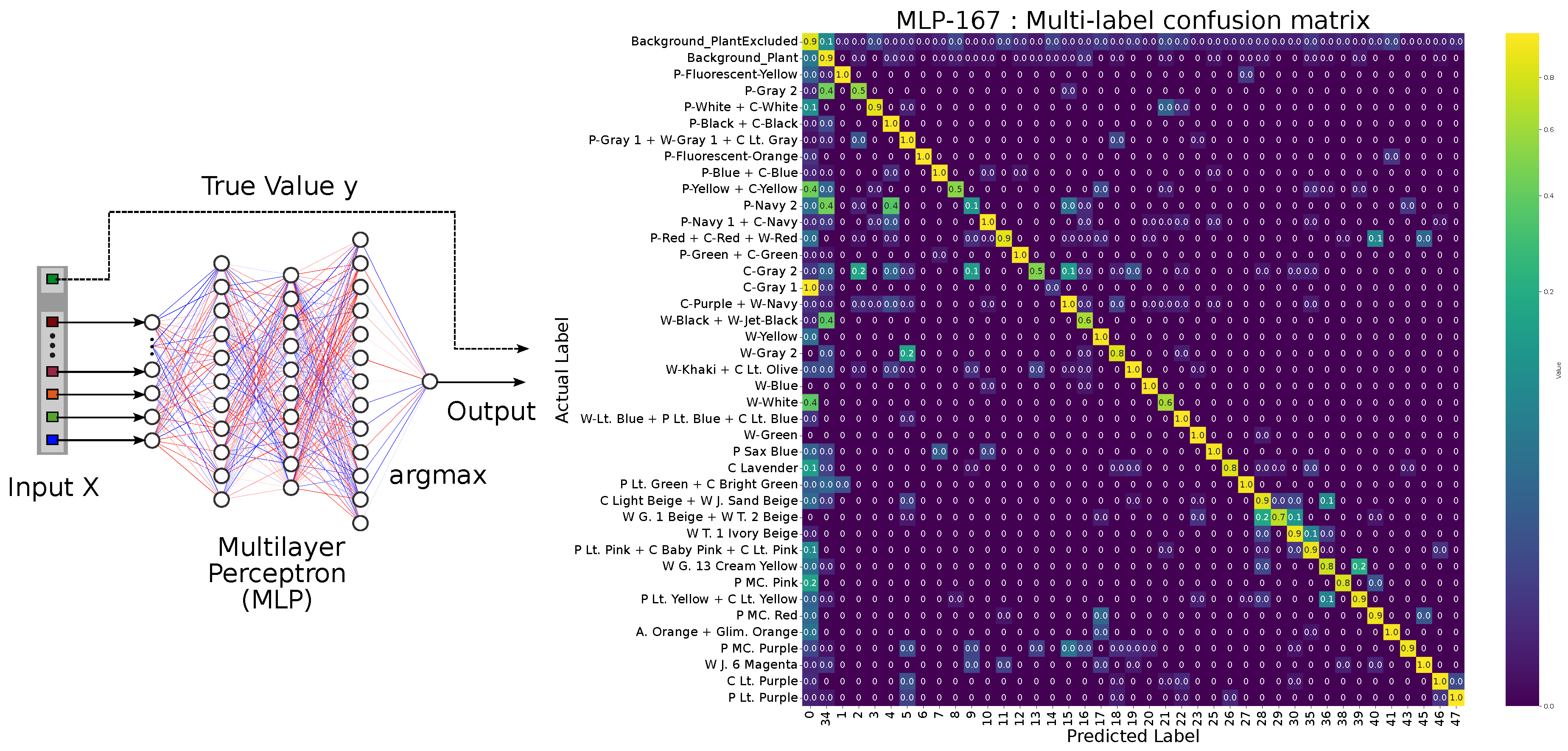

Figure 6.

Multi-Layer Perceptron workflow and multi-label confusion matrix for 167 bands.

Figure 6.

Multi-Layer Perceptron workflow and multi-label confusion matrix for 167 bands.

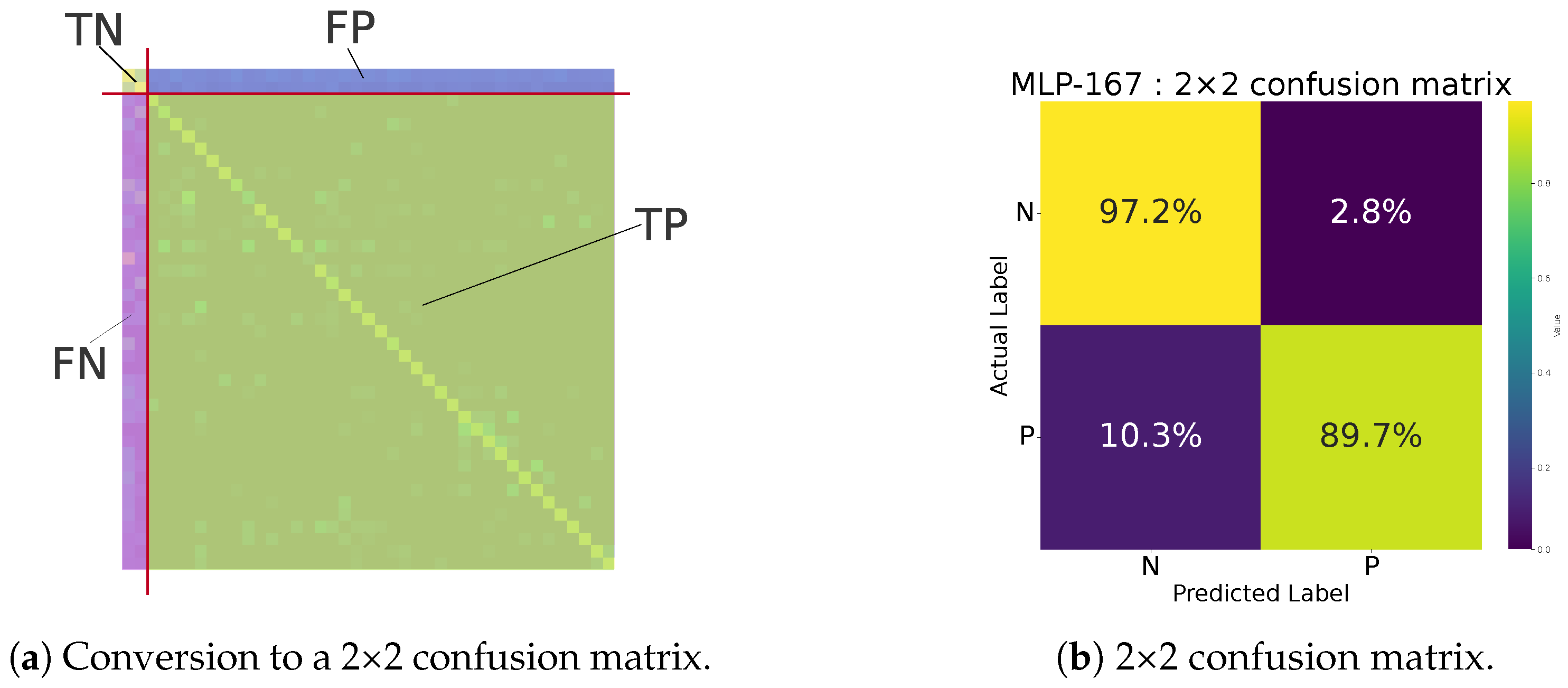

Figure 7.

(a) Conversion to the clothing versus background matrix. (b) Example of the 2×2 confusion matrix for the 167-band model.

Figure 7.

(a) Conversion to the clothing versus background matrix. (b) Example of the 2×2 confusion matrix for the 167-band model.

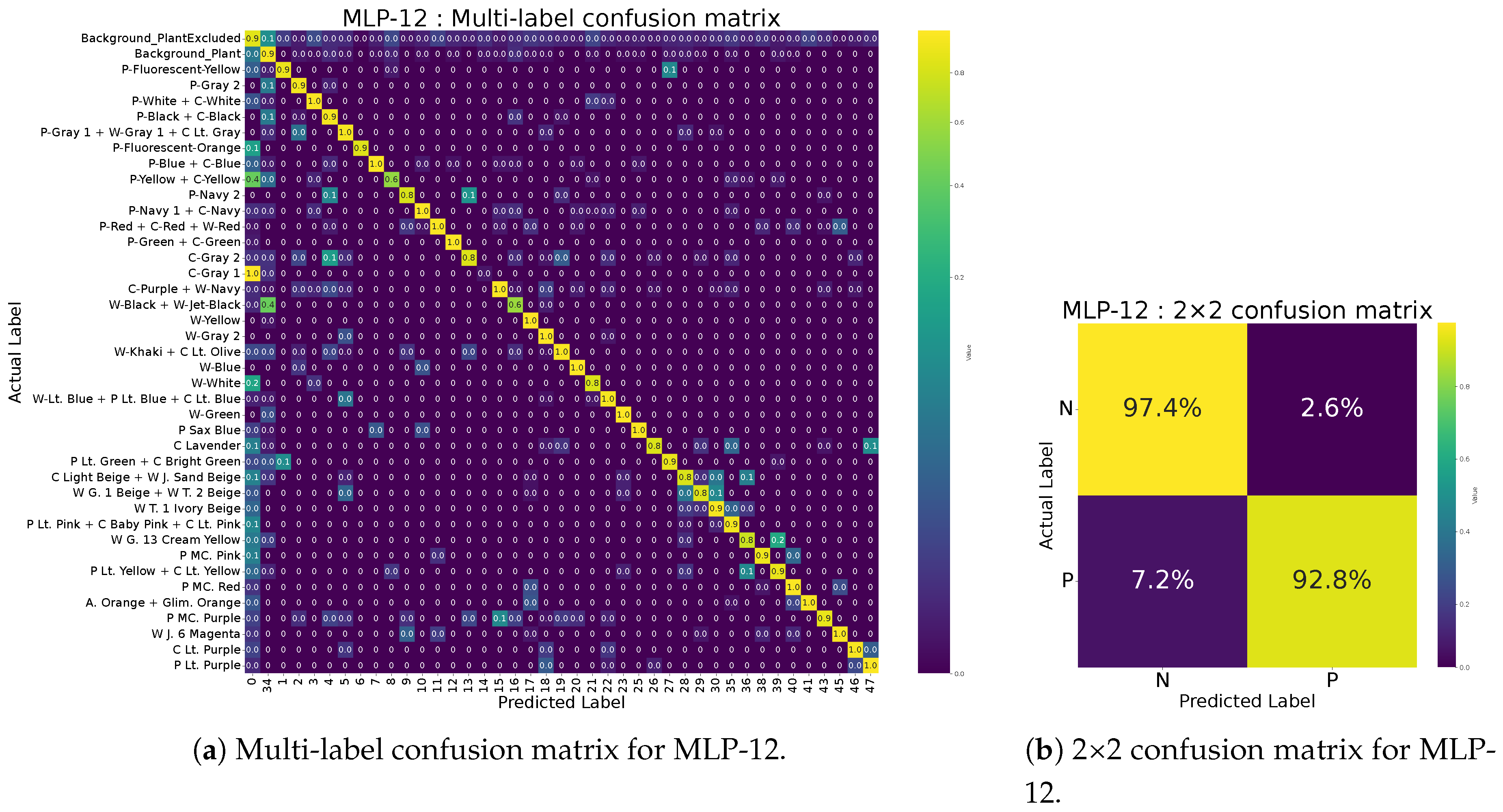

Figure 8.

(a) Multi-label confusion matrix for 12-band Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP-12). (b) 2×2 confusion matrix for MLP-12.

Figure 8.

(a) Multi-label confusion matrix for 12-band Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP-12). (b) 2×2 confusion matrix for MLP-12.

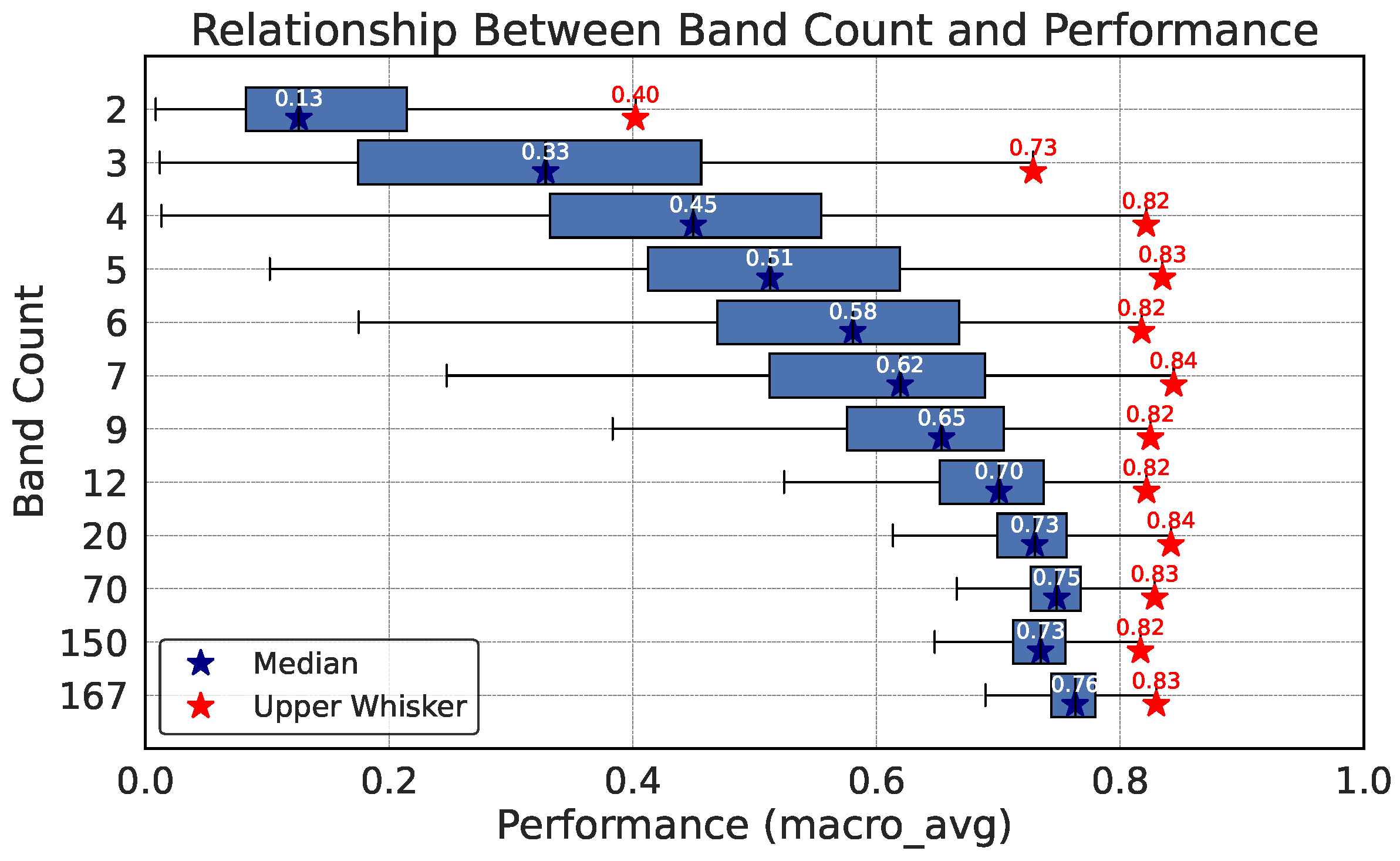

Figure 9.

Relationship between band count and macro_avg.

Figure 9.

Relationship between band count and macro_avg.

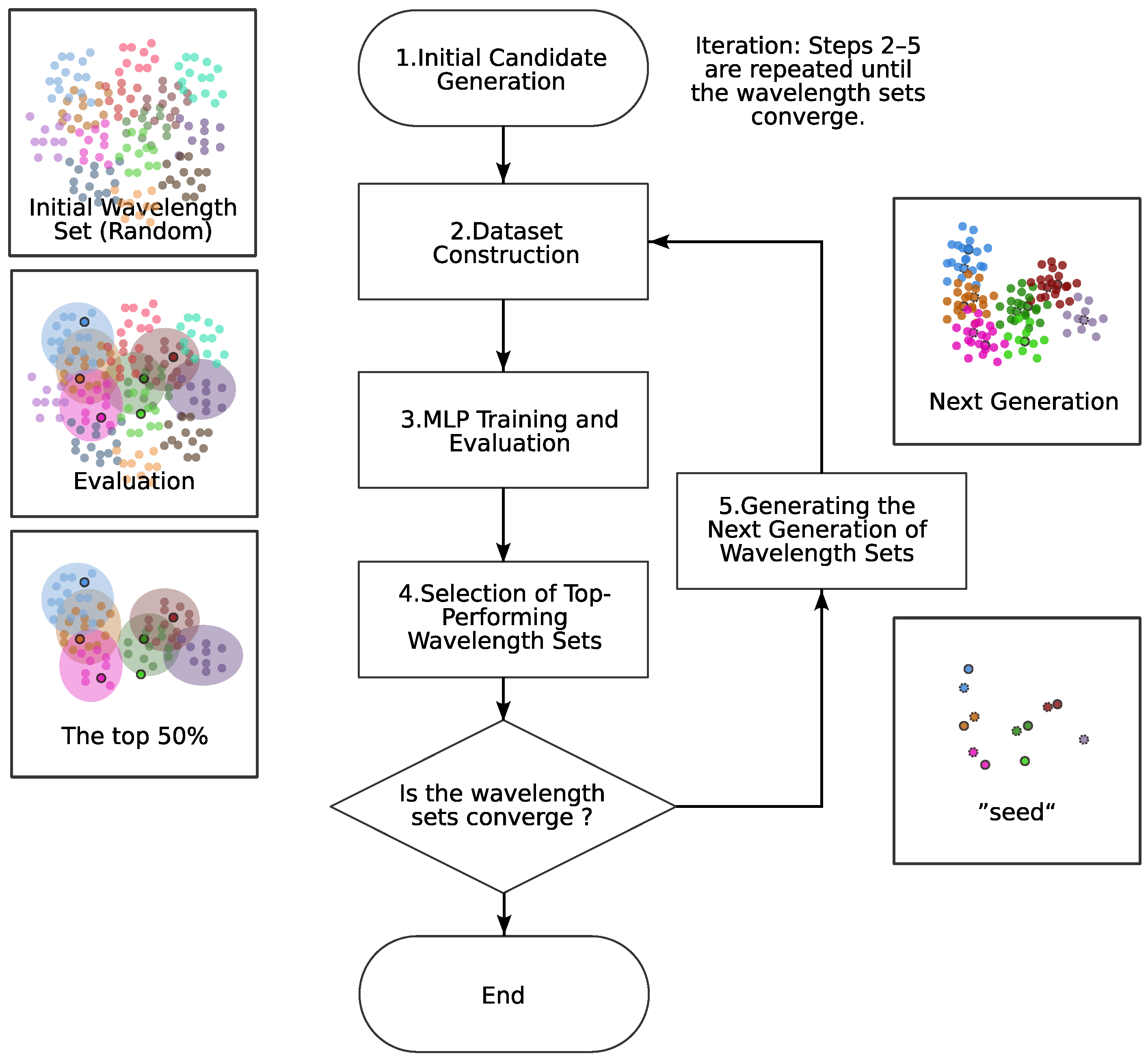

Figure 10.

Flowchart of Optimal Wavelength Set exploration (Steps 1–5 in the text). See

Section 4.3.2 for details.

Figure 10.

Flowchart of Optimal Wavelength Set exploration (Steps 1–5 in the text). See

Section 4.3.2 for details.

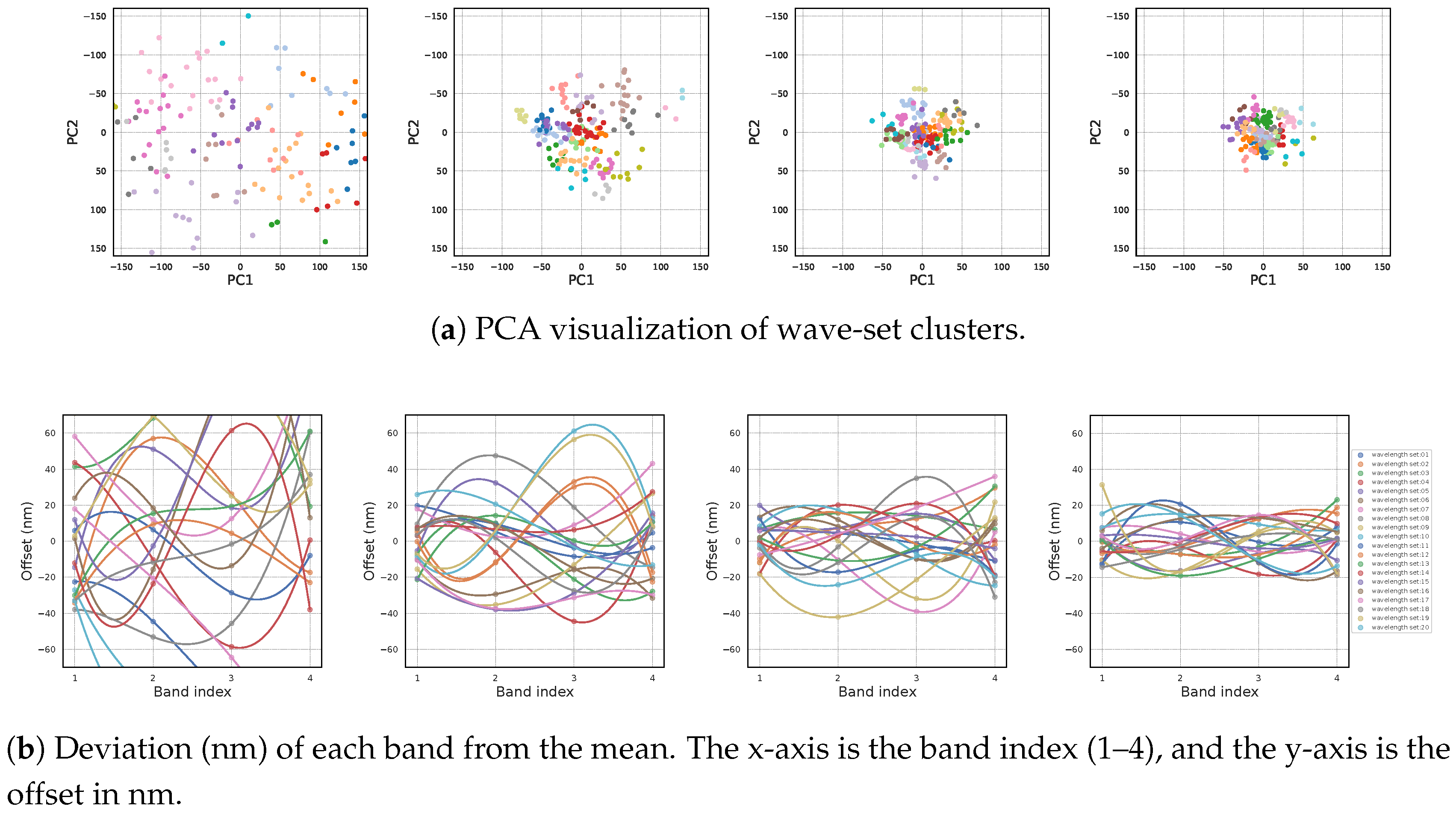

Figure 11.

Example of convergence for the 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set search (from left to right: initial state, iteration 1, iteration 2, iteration 5). (a) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) visualization of wave-set clusters. (b) Deviation (nm) of each band from the mean. The x-axis is the band index (1–4), and the y-axis is the offset in nm.

Figure 11.

Example of convergence for the 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set search (from left to right: initial state, iteration 1, iteration 2, iteration 5). (a) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) visualization of wave-set clusters. (b) Deviation (nm) of each band from the mean. The x-axis is the band index (1–4), and the y-axis is the offset in nm.

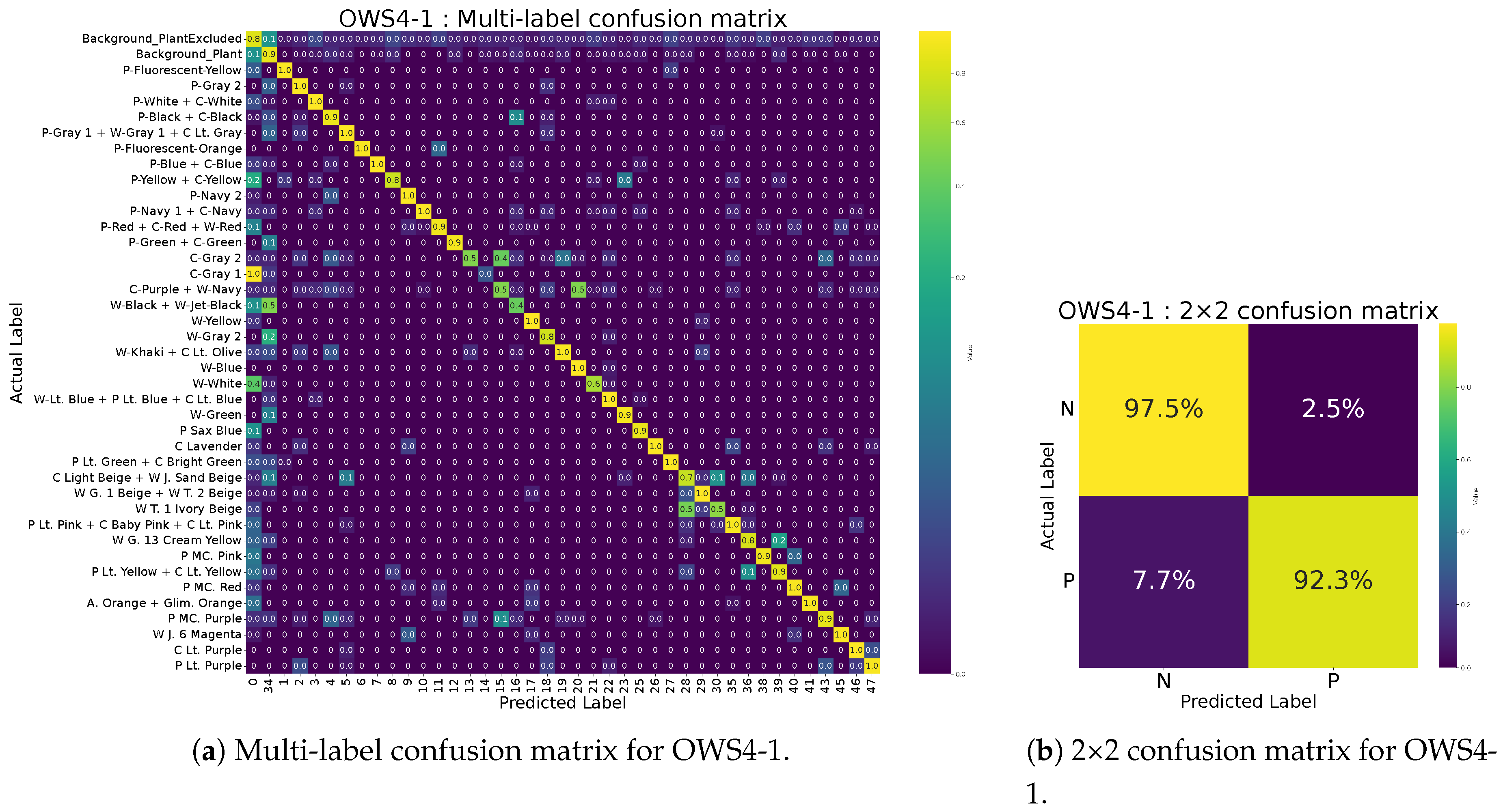

Figure 12.

(a) Multi-label confusion matrix for Optimal Wavelength Set with 4 bands (OWS4-1). (b) 2×2 confusion matrix for OWS4-1.

Figure 12.

(a) Multi-label confusion matrix for Optimal Wavelength Set with 4 bands (OWS4-1). (b) 2×2 confusion matrix for OWS4-1.

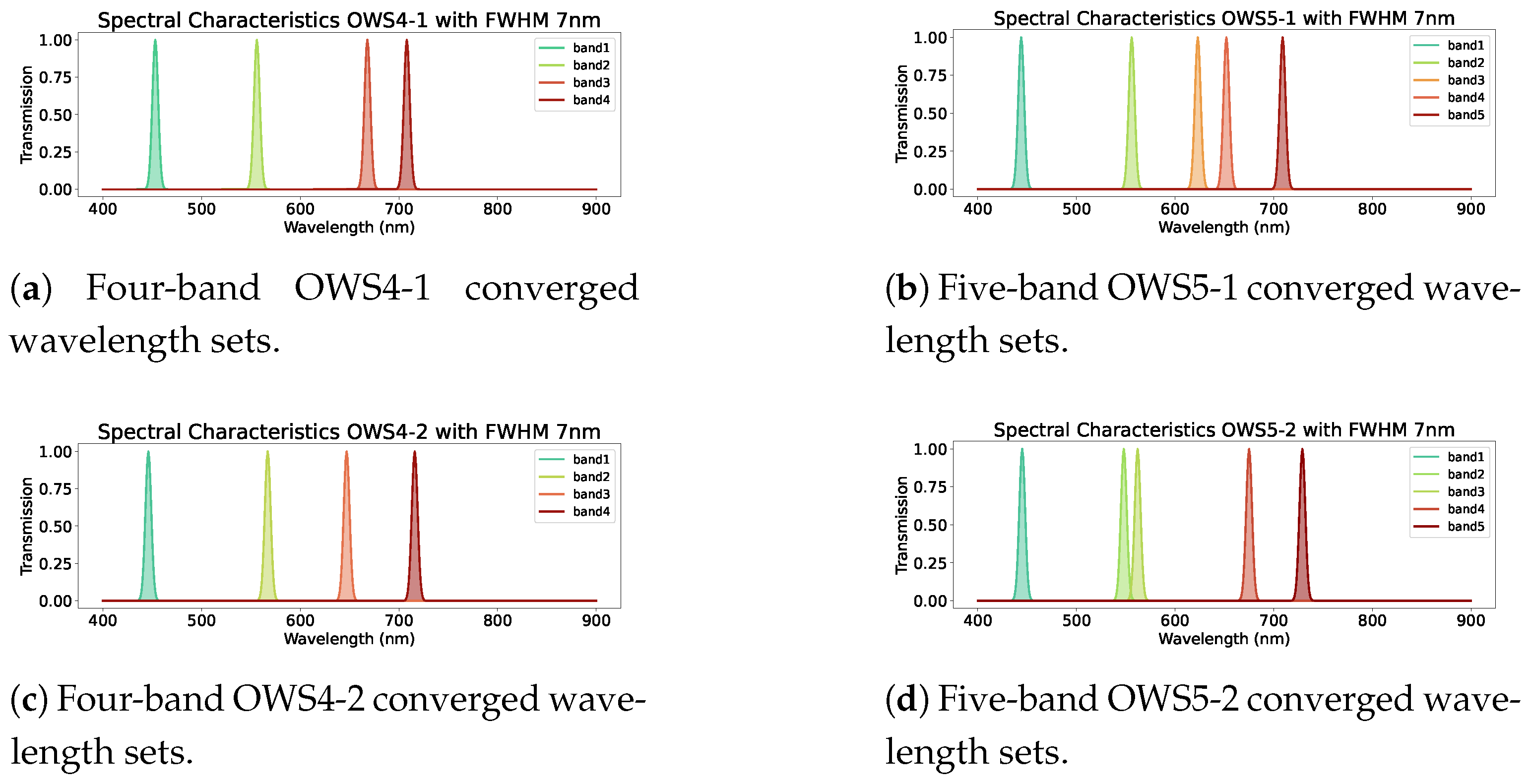

Figure 13.

Passbands of the 4- and 5-band Optimal Wavelength Sets (OWS). (a) OWS4-1. (b) OWS5-1. (c) OWS4-2. (d) OWS5-2.

Figure 13.

Passbands of the 4- and 5-band Optimal Wavelength Sets (OWS). (a) OWS4-1. (b) OWS5-1. (c) OWS4-2. (d) OWS5-2.

Figure 14.

Multispectral reflectance at the four wavelengths of the Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1: 453, 556, 668, 708 nm) for (a) clothing, (b) inorganic background, and (c) plant background.

Figure 14.

Multispectral reflectance at the four wavelengths of the Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1: 453, 556, 668, 708 nm) for (a) clothing, (b) inorganic background, and (c) plant background.

Figure 15.

Performance variation when shifting the center wavelength of each of the 4 bands.

Figure 15.

Performance variation when shifting the center wavelength of each of the 4 bands.

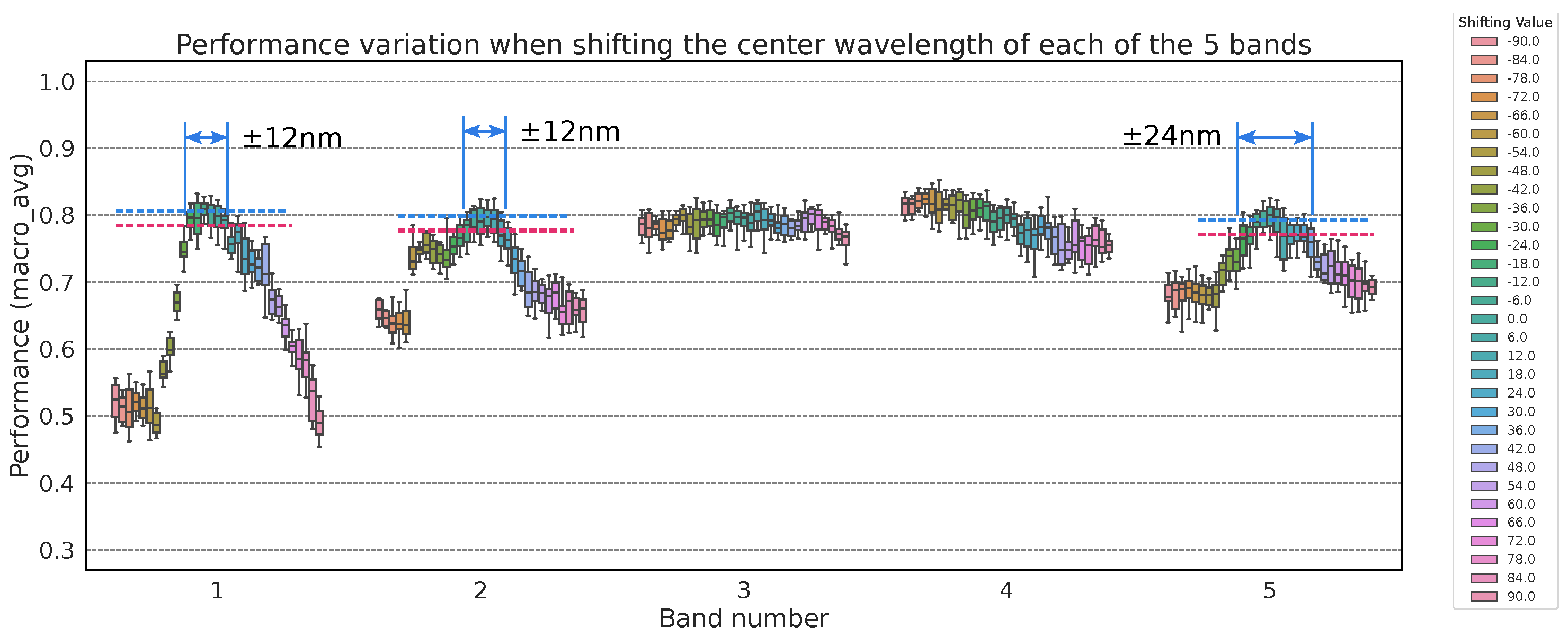

Figure 16.

Performance variation for the 5-band set under center-wavelength shifts. Shifting the 3rd or 4th band alone had minimal impact (see text).

Figure 16.

Performance variation for the 5-band set under center-wavelength shifts. Shifting the 3rd or 4th band alone had minimal impact (see text).

Figure 17.

Performance variation when simultaneously widening the passband of all 4 bands.

Figure 17.

Performance variation when simultaneously widening the passband of all 4 bands.

Figure 18.

Example inference results at resolutions (a) Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) at 512×512 pixels, (b) MLP at 64×64 pixels, and (c) YOLOv5m at 512×512 pixels, (d) YOLOv5m at 64×64 pixels. The MLP detects the boundary of clothing pixels and draws bounding boxes. It uses only spectral information from each pixel to decide whether it is clothing.

Figure 18.

Example inference results at resolutions (a) Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) at 512×512 pixels, (b) MLP at 64×64 pixels, and (c) YOLOv5m at 512×512 pixels, (d) YOLOv5m at 64×64 pixels. The MLP detects the boundary of clothing pixels and draws bounding boxes. It uses only spectral information from each pixel to decide whether it is clothing.

Figure 19.

inference speed, memory usage, and detection score. (a) Inference speed. The Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) stays well below the 33 ms real-time threshold. (b) Memory usage. (c) Detection score.

Figure 19.

inference speed, memory usage, and detection score. (a) Inference speed. The Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) stays well below the 33 ms real-time threshold. (b) Memory usage. (c) Detection score.

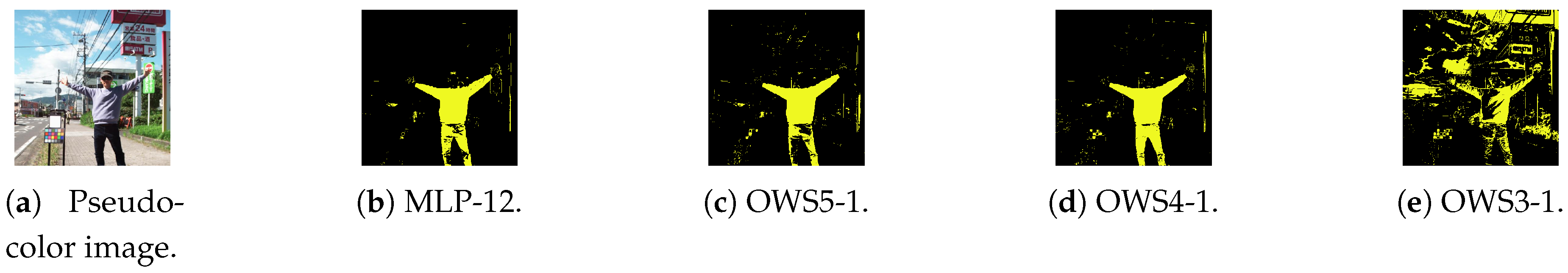

Figure 20.

Examples of inference results from some Wavelength Sets models with different band counts (12, 5, 4, and 3). Models with bands perform well. (a) Pseudo-color image. (b) 12-band Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP-12). (c) 5-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS5-1) MLP. (d) 4-band OWS4-1 MLP. (e) 3-band OWS3-1 MLP.

Figure 20.

Examples of inference results from some Wavelength Sets models with different band counts (12, 5, 4, and 3). Models with bands perform well. (a) Pseudo-color image. (b) 12-band Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP-12). (c) 5-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS5-1) MLP. (d) 4-band OWS4-1 MLP. (e) 3-band OWS3-1 MLP.

Figure 21.

Example of a street scene containing a person with clothing not included in the training dataset. (a) Pseudo-color image. (b) 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1) MLP predictions. (c) Detailed labeling of the clothing region.

Figure 21.

Example of a street scene containing a person with clothing not included in the training dataset. (a) Pseudo-color image. (b) 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1) MLP predictions. (c) Detailed labeling of the clothing region.

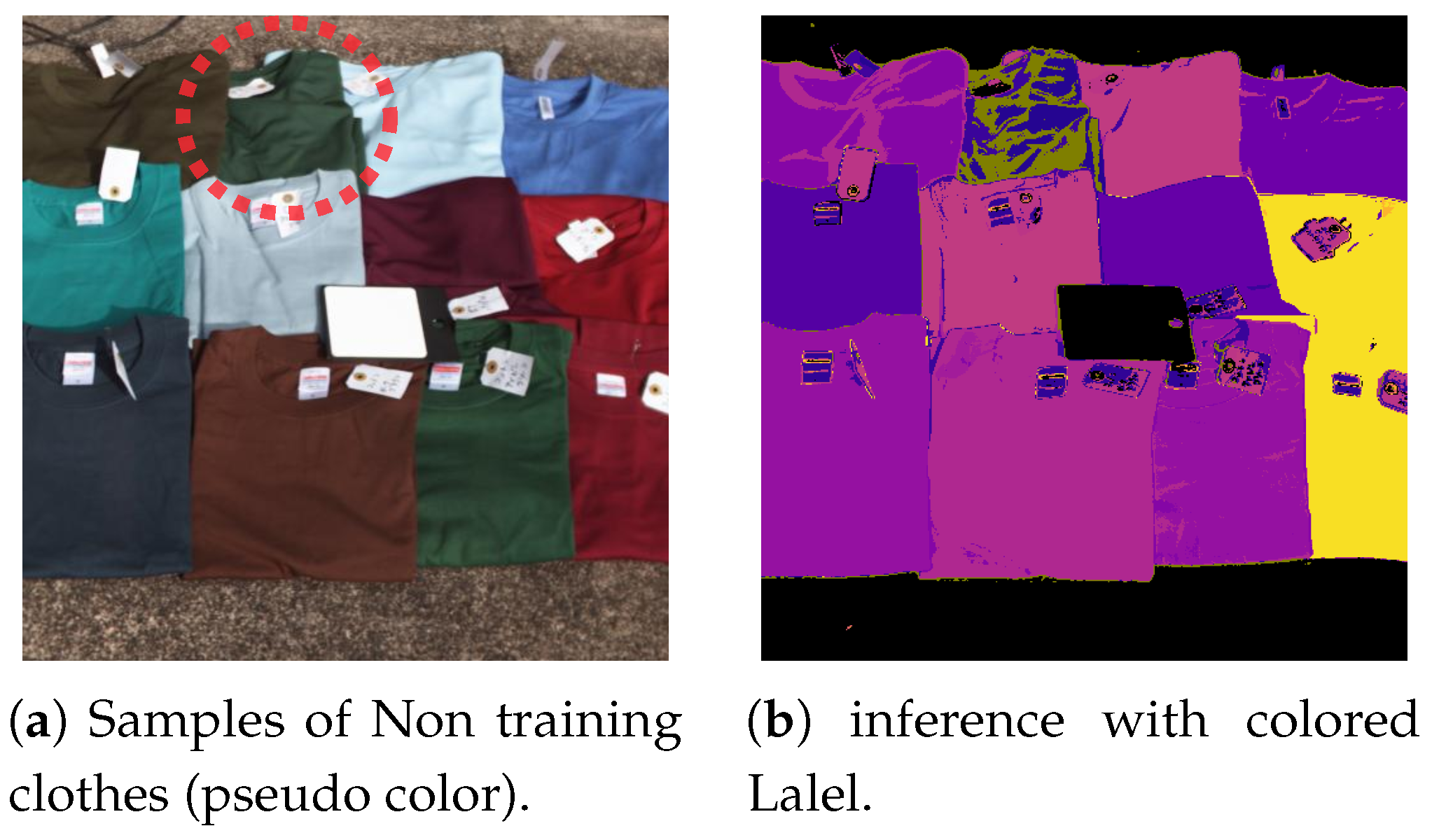

Figure 22.

Samples of detected clothing not included in the training dataset. A single case misidentified as “plant” (red circle). (a) Pseudo-color image. (b) 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1) MLP predictions.

Figure 22.

Samples of detected clothing not included in the training dataset. A single case misidentified as “plant” (red circle). (a) Pseudo-color image. (b) 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1) MLP predictions.

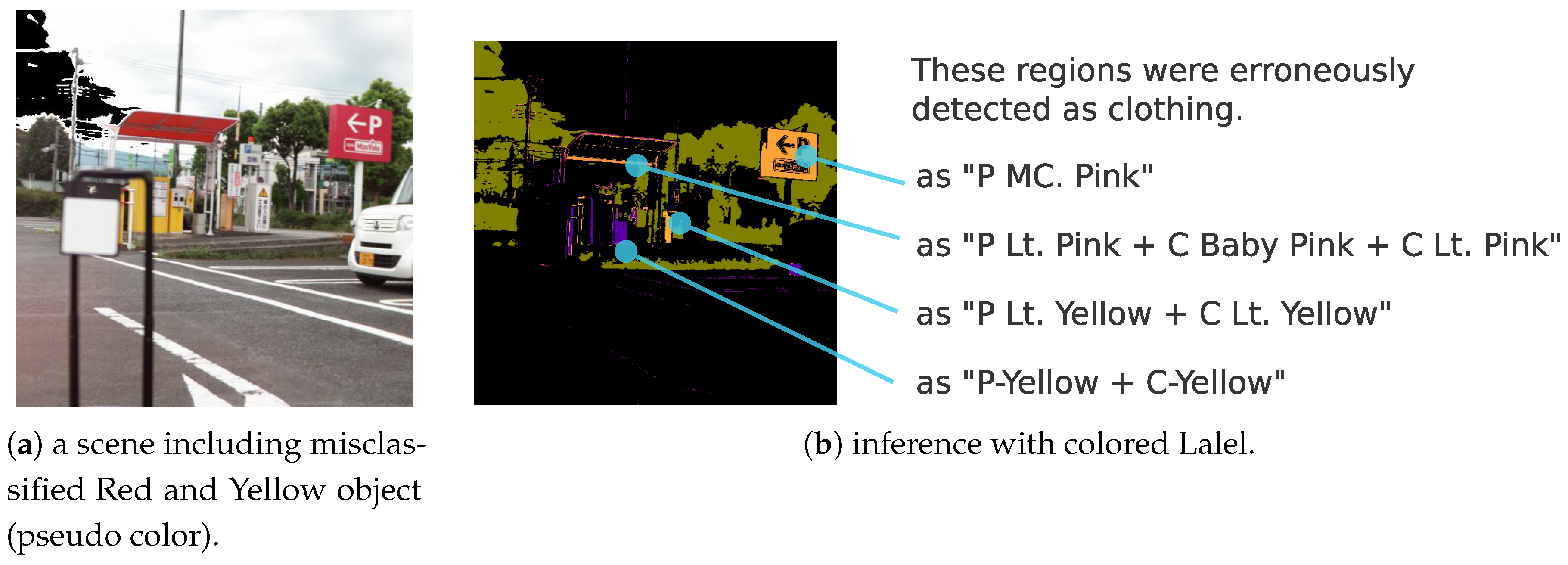

Figure 23.

Example of a street scene containing background objects likely to be misclassified as clothing. (a) Pseudo-color image. (b) Multi-label predictions by the 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1) MLP.

Figure 23.

Example of a street scene containing background objects likely to be misclassified as clothing. (a) Pseudo-color image. (b) Multi-label predictions by the 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1) MLP.

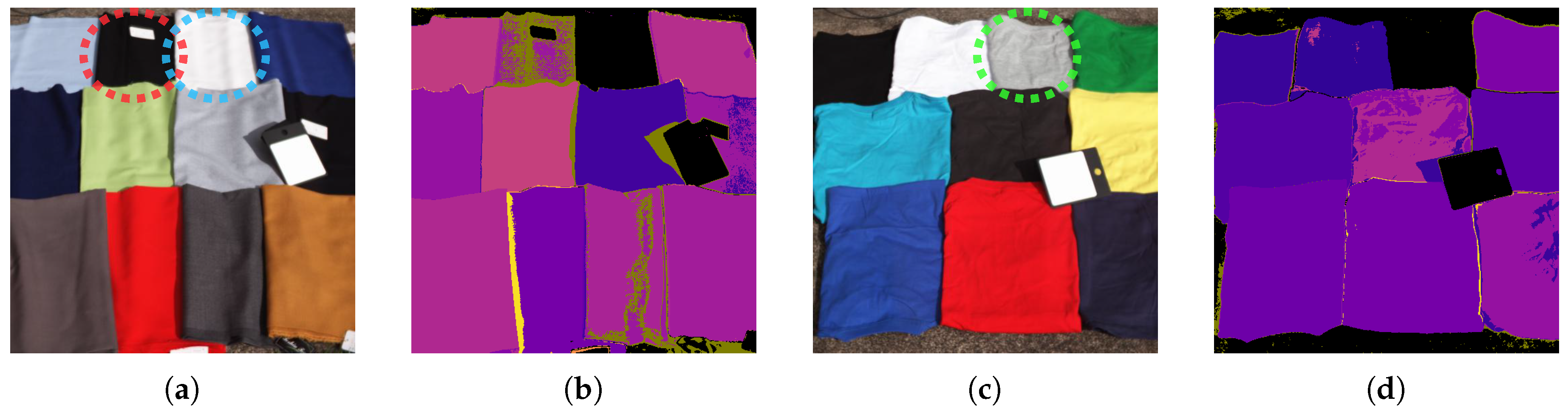

Figure 24.

White (blue circle) or black (red circle) wool garments can be missed. (a) Pseudo-color image. (b) Multi-label predictions by the 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1) MLP. Gray cotton (green circle) garments can be missed. (c) Pseudo-color image. (d) Multi-label predictions by the 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1) MLP.

Figure 24.

White (blue circle) or black (red circle) wool garments can be missed. (a) Pseudo-color image. (b) Multi-label predictions by the 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1) MLP. Gray cotton (green circle) garments can be missed. (c) Pseudo-color image. (d) Multi-label predictions by the 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1) MLP.

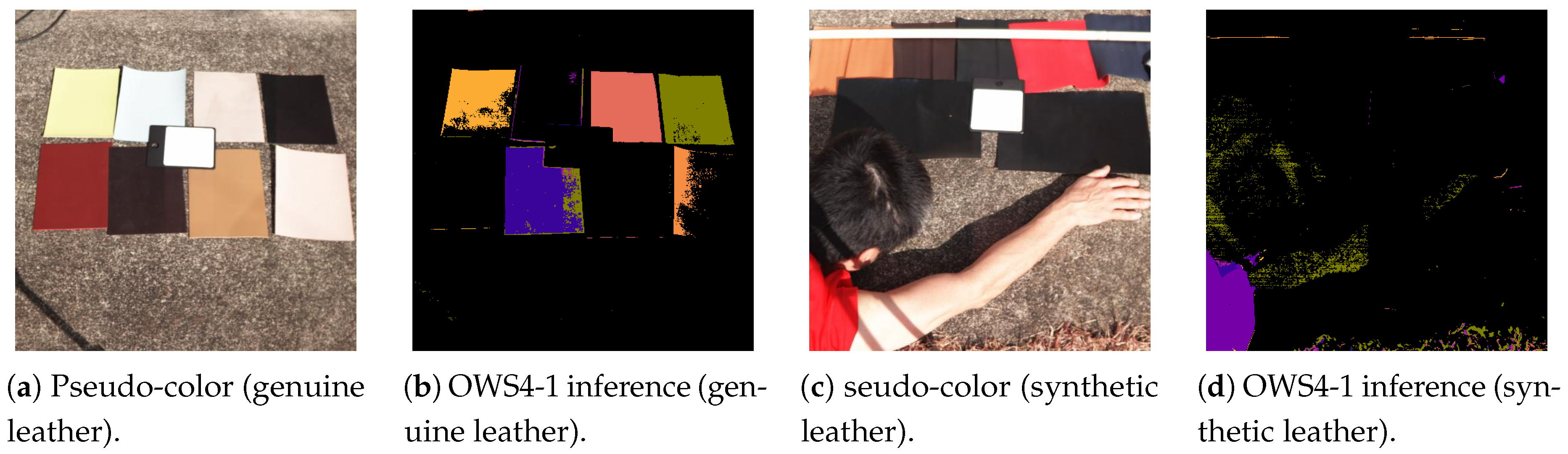

Figure 25.

Examples of clothing materials deviating from this study’s “clothing hypothesis” (genuine leather and synthetic leather). (a) Pseudo-color image (genuine leather). (b) 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1) MLP inference (genuine leather). (c) Pseudo-color image (synthetic leather). (d) 4-band OWS4-1 MLP inference (synthetic leather).

Figure 25.

Examples of clothing materials deviating from this study’s “clothing hypothesis” (genuine leather and synthetic leather). (a) Pseudo-color image (genuine leather). (b) 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1) MLP inference (genuine leather). (c) Pseudo-color image (synthetic leather). (d) 4-band OWS4-1 MLP inference (synthetic leather).

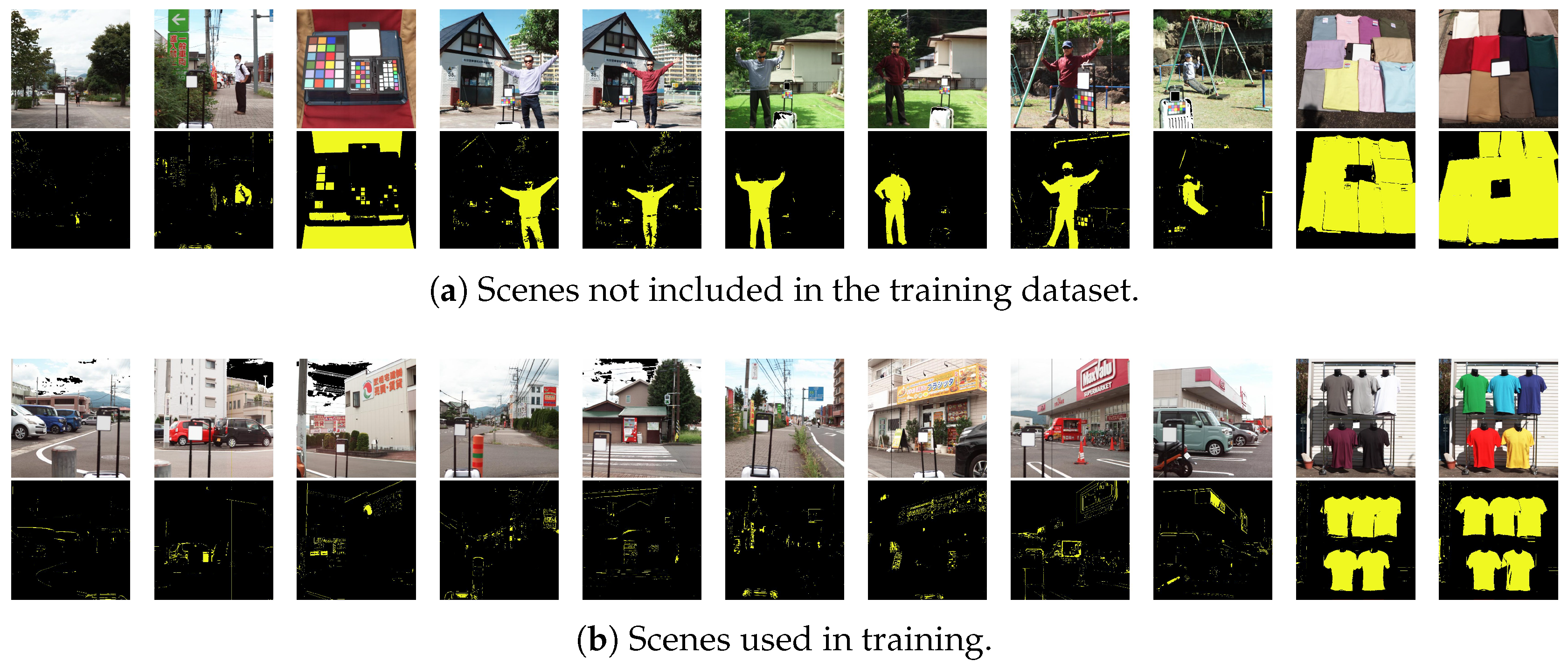

Figure 26.

Overall inference examples from the 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1) MLP (top: pseudo-color image; bottom: classification result with bright yellow for clothing and black for background). (a) Scenes not included in the training dataset. (b) Scenes used in training.

Figure 26.

Overall inference examples from the 4-band Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS4-1) MLP (top: pseudo-color image; bottom: classification result with bright yellow for clothing and black for background). (a) Scenes not included in the training dataset. (b) Scenes used in training.

Figure 27.

(a) 4-band reflectance and (b) hyperspectral reflectance for four types of green/blue garments.

Figure 27.

(a) 4-band reflectance and (b) hyperspectral reflectance for four types of green/blue garments.

Figure 28.

(a) 4-band and (b) hyperspectral reflectance for plants.

Figure 28.

(a) 4-band and (b) hyperspectral reflectance for plants.

Figure 29.

Reflectance at (a) 4 bands and (b) full hyperspectral data for white garments (polyester, cotton, and wool).

Figure 29.

Reflectance at (a) 4 bands and (b) full hyperspectral data for white garments (polyester, cotton, and wool).

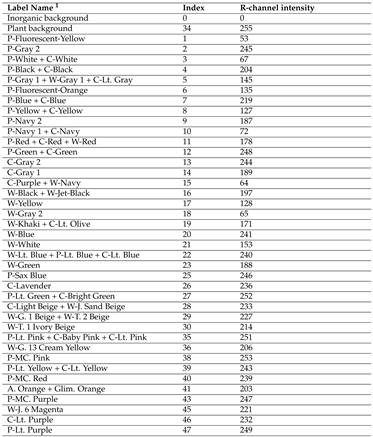

Table 1.

List of 41 labels (label name, index, and R-channel intensity in the labeled image).

Table 1.

List of 41 labels (label name, index, and R-channel intensity in the labeled image).

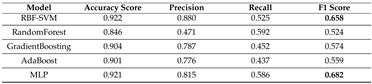

Table 2.

Comparison of five machine learning approaches: Radial Basis Function Support Vector Machine (RBF-SVM), Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Adaptive Boosting, and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP).

Table 2.

Comparison of five machine learning approaches: Radial Basis Function Support Vector Machine (RBF-SVM), Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Adaptive Boosting, and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP).

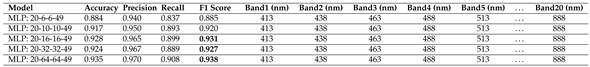

Table 3.

Results of preliminary experiments on the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) hidden units (6/10/16/32/64). Performance plateaued with 16 units × 2 layers.

Table 3.

Results of preliminary experiments on the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) hidden units (6/10/16/32/64). Performance plateaued with 16 units × 2 layers.

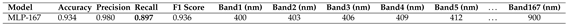

Table 4.

Accuracy/Precision/Recall/F-measure for 167-band Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP-167).

Table 4.

Accuracy/Precision/Recall/F-measure for 167-band Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP-167).

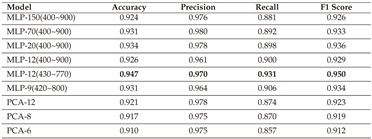

Table 5.

Comparison of evaluation metrics for Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) models with reduced dimensions by uniformly subsampling wavelengths or by Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

Table 5.

Comparison of evaluation metrics for Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) models with reduced dimensions by uniformly subsampling wavelengths or by Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

Table 6.

Final Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS) combinations and evaluation metrics for 4-, 5-, and 3-band searches.

Table 6.

Final Optimal Wavelength Set (OWS) combinations and evaluation metrics for 4-, 5-, and 3-band searches.

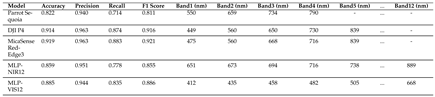

Table 7.

Performance of Additional Wavelength Set Configurations: Agricultural-Use and Range-Limited (Visible-Only and Near-Infrared-Only) Examples.

Table 7.

Performance of Additional Wavelength Set Configurations: Agricultural-Use and Range-Limited (Visible-Only and Near-Infrared-Only) Examples.

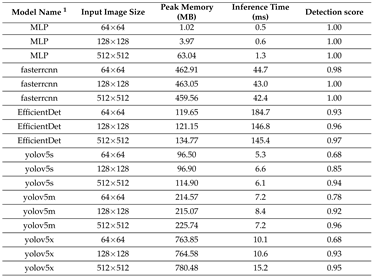

Table 8.

Comparison of speed, memory, and detection score for a sample test image.

Table 8.

Comparison of speed, memory, and detection score for a sample test image.