Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

21 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

| ITM | No – ITM | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 147 | 49 |

| Age (Years) | 68.18 ± 7.697 | 70.27 ± 6.984 |

| Weight (Kg) | 85.64 ± 17.043 | 84.29 ± 13.995 |

| Height (cm) | 175.91 ± 9.485 | 175.91 ± 8.070 |

| Hospital Stay (days) | 12.41 ± 4.668 | 14.37 ± 7.857 |

| ICU / IMC Stay (days) | 0.94 ± 0.751 | 0.87 ± 0.647 |

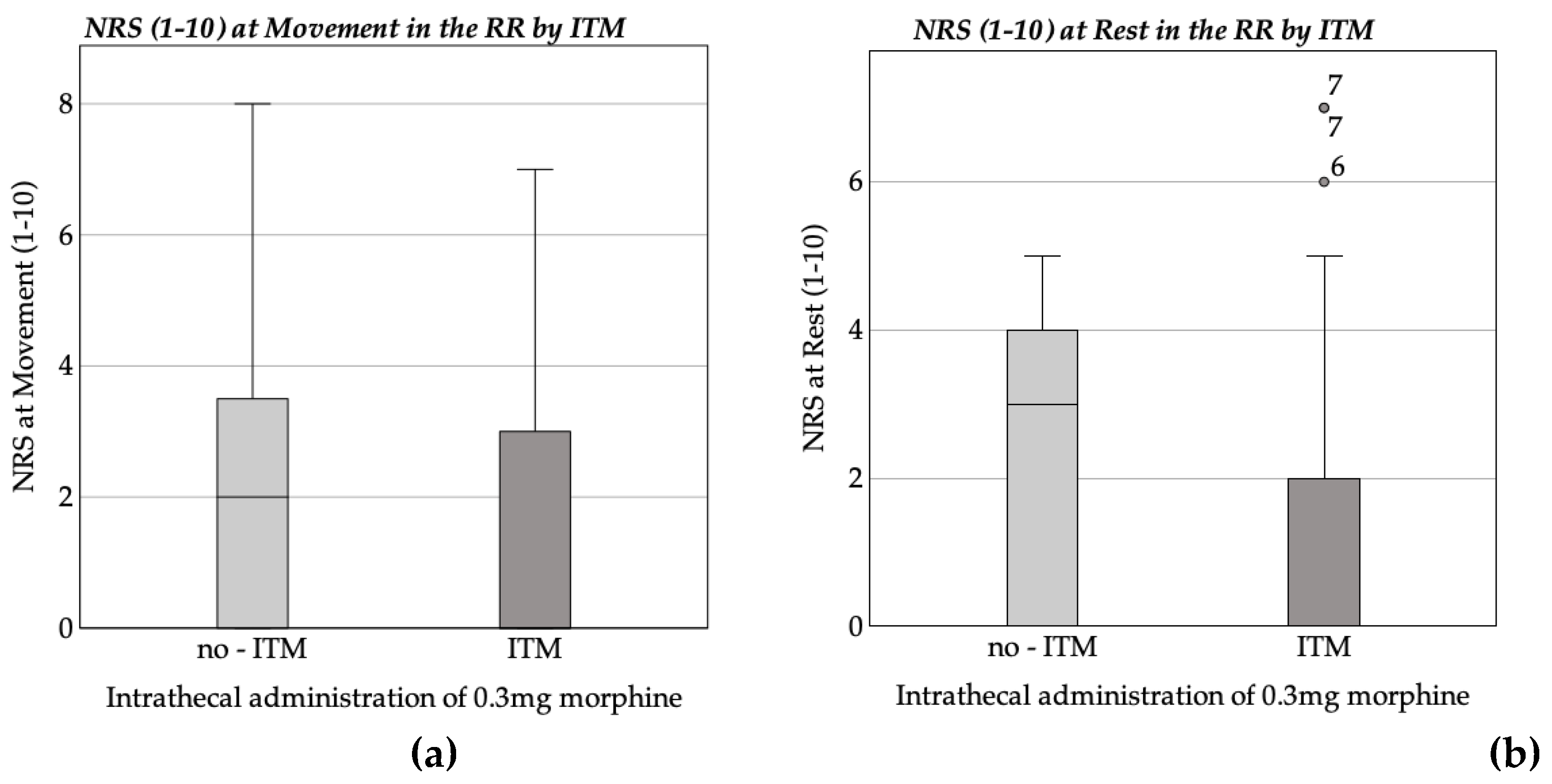

3.2. Pain Assessment and Analgesic Administration

3.2.1. Recovery Room Pain Assessment and Medication Administration

| NRS (1-10) at Rest in the recovery room | |||||

| Coefficients | b | SE | β | t | p |

| (Constant) | 9.246 | 1.992 | 4.641 | <.001 | |

| ITM | -1.156 | .345 | -.269 | -3.353 | .001 |

| Age | -.069 | .021 | -.275 | -3.223 | .002 |

| Weight | -.010 | .009 | -.091 | -1.076 | .284 |

| Propofol | -.004 | .002 | -.149 | -1.652 | .101 |

| Midazolam | -.005 | .005 | -.091 | -1.144 | .254 |

| Thiopental | -.010 | .006 | -.128 | -1.577 | .117 |

| Sufentanil | -.082 | .148 | -.048 | -.553 | .581 |

| Piritramide | .034 | .046 | .059 | .726 | .469 |

| Fentanyl. | -1843,000 | .884 | -.168 | -2.085 | .039 |

| Arterial Hypertony Diabetes Mellitus Hypothyroidism COPD Time after ITM |

-.079 .181 -.386 -4.85 -2.217E-5 |

.294 .490 .563 .749 .000 |

-.022 .030 -.055 -.056 -.041 |

-.269 .369 -.686 -.647 -.522 |

.788 .713 .494 .518 .603 |

| Remarks: N = 153; R² = 0.184; corr. R² = 0.101; F(14, 138) = 2.223; p = 0.009 | |||||

| NRS (1-10) at Movement in the recovery room | |||||

| Coefficients | b | SE | β | t | p |

| (Constant) | 9.614 | 2.275 | 4.226 | <.001 | |

| ITM | -.872 | .394 | -.181 | -2.214 | .028 |

| Age | -.082 | .025 | -.290 | -3.344 | .001 |

| Weight | -.009 | .010 | -.078 | -.903 | .368 |

| Propofol | -.005 | .003 | -.162 | -1.758 | .081 |

| Midazolam | -.006 | .005 | -.092 | -1.132 | .260 |

| Thiopental | -.010 | .007 | -.125 | -1.520 | .131 |

| Sufentanil | -.124 | .168 | -.064 | -.733 | .465 |

| Piritramide | .051 | .053 | .078 | .952 | .343 |

| Fentanyl | -1.727 | 1.009 | -.141 | -1.711 | .089 |

| Arterial Hypertony | -.108 | .336 | -.027 | -.321 | .749 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | .302 | .559 | .044 | .541 | .590 |

| Hypothyroidism | -.478 | .643 | -.061 | -.743 | .458 |

| COPD | -.083 | .856 | -.009 | -.097 | .923 |

| Time after ITM | 1.223E-5 | .000 | .020 | .252 | .801 |

| Remarks: N = 153; R² = 0.154; corr. R² = 0.068; F (14, 138) = 1.791; p = 0.045 | |||||

3.3. Complications and side effects

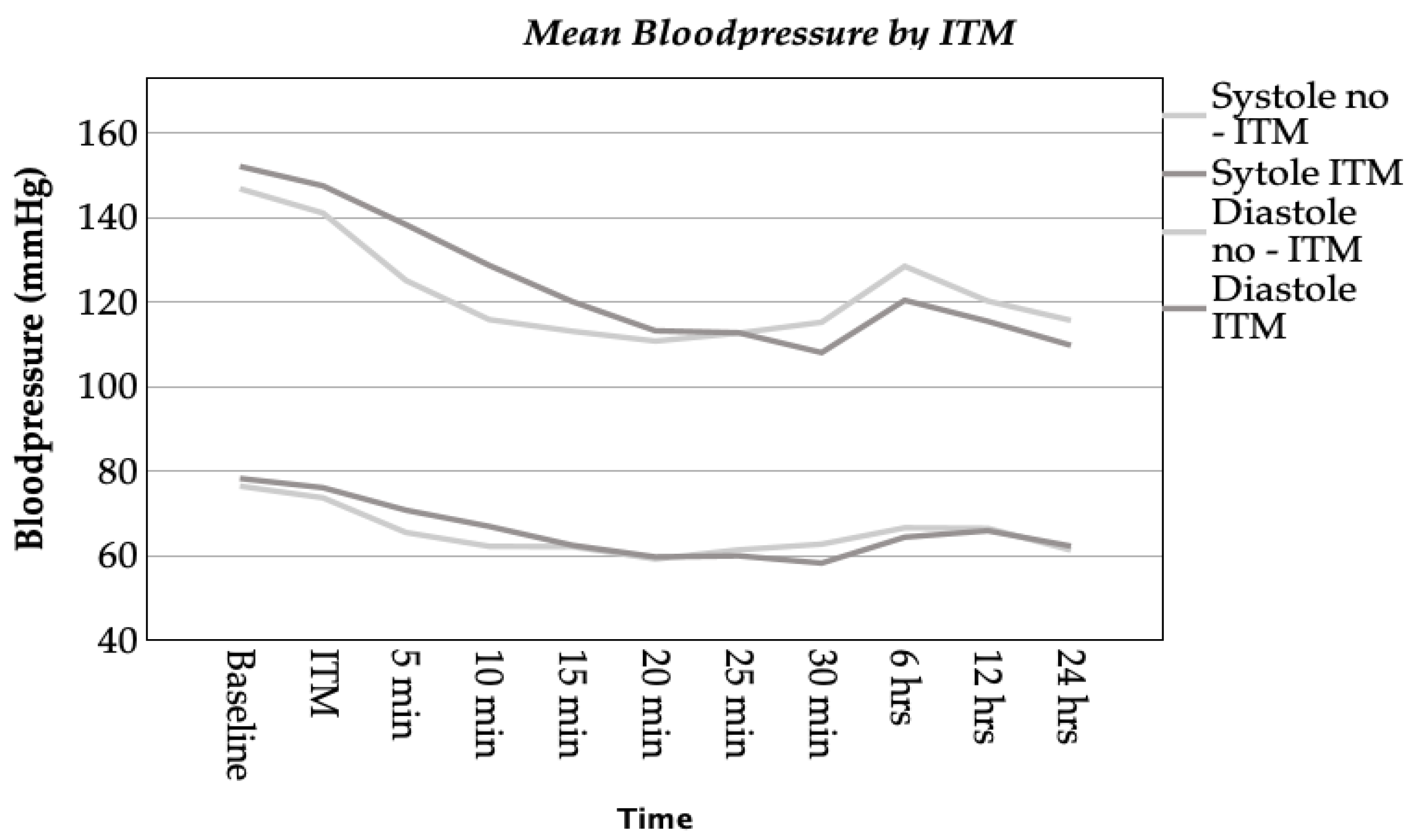

3.3.1. Hemodynamic Complications

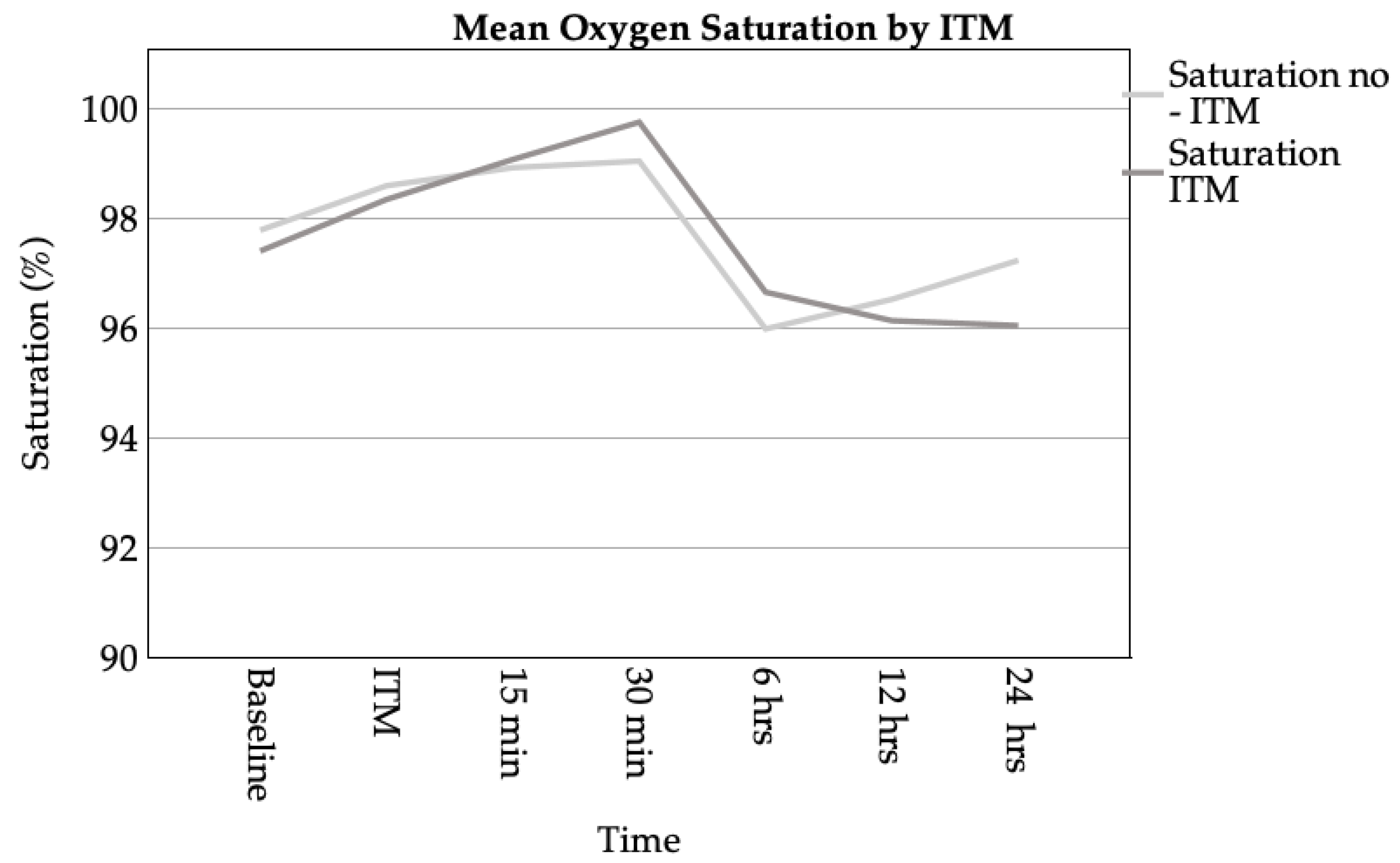

3.3.2. Respiratory Complications

3.3.3. Hospital Stay

3.3.4. Effect of Intrathecal Morphine on Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting

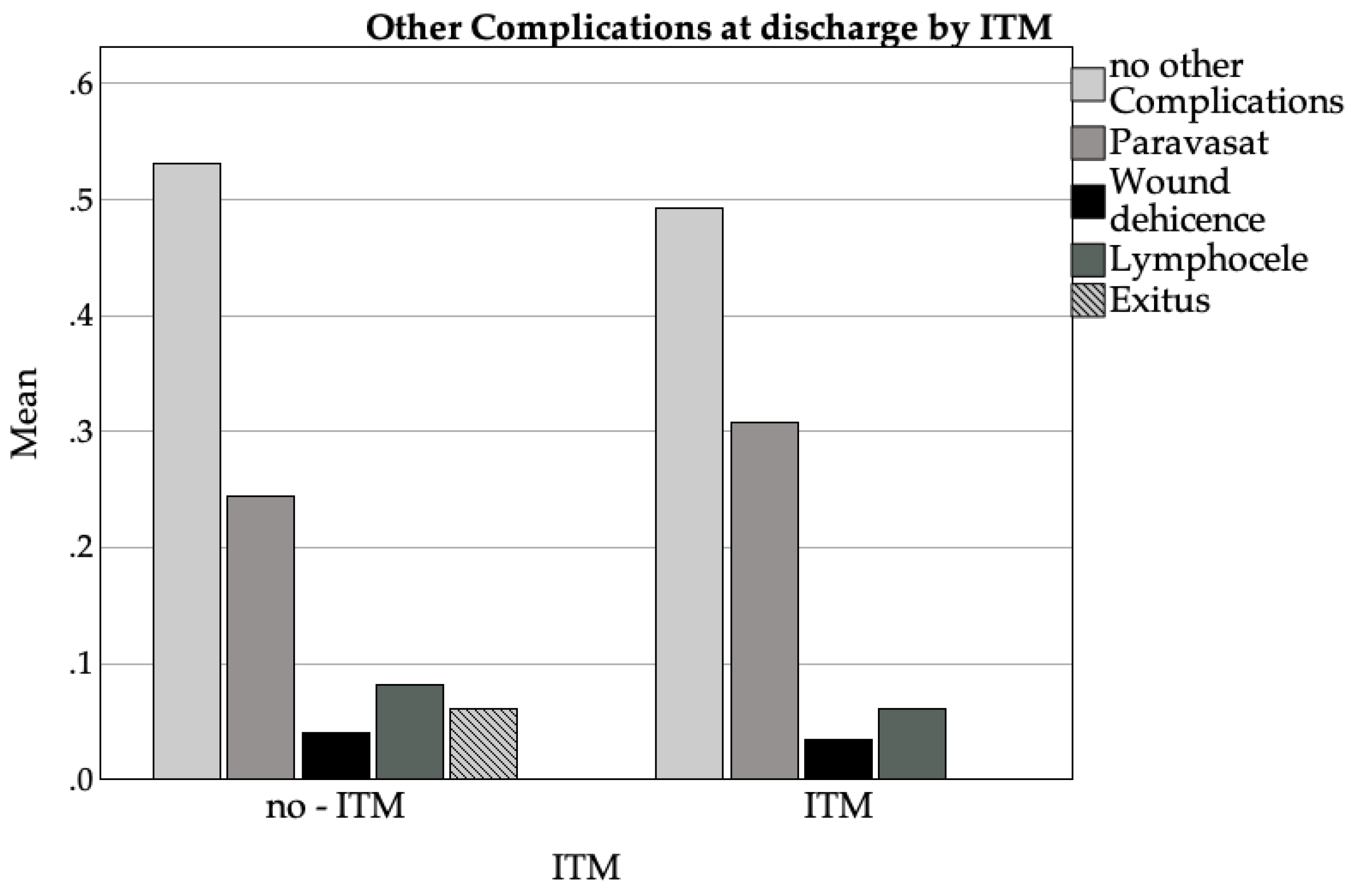

3.3.5. Other Complications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| DVT | Deep Venous Thrombosis |

| EAU | European Association of Urology |

| GA | General Anaesthesia |

| GDPR | Union’s General Data Protection Regulation |

| ITM | Intrathecal Morphin |

| IMC | Intermediate Care Unit |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| Kg | Kilogram |

| Mdn | Median |

| Mg | Milligram |

| ml | Millilitres |

| NRS | Numeric Rating Scale |

| PONV | Postoperative nausea and vomiting |

| RR | Recovery Room |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

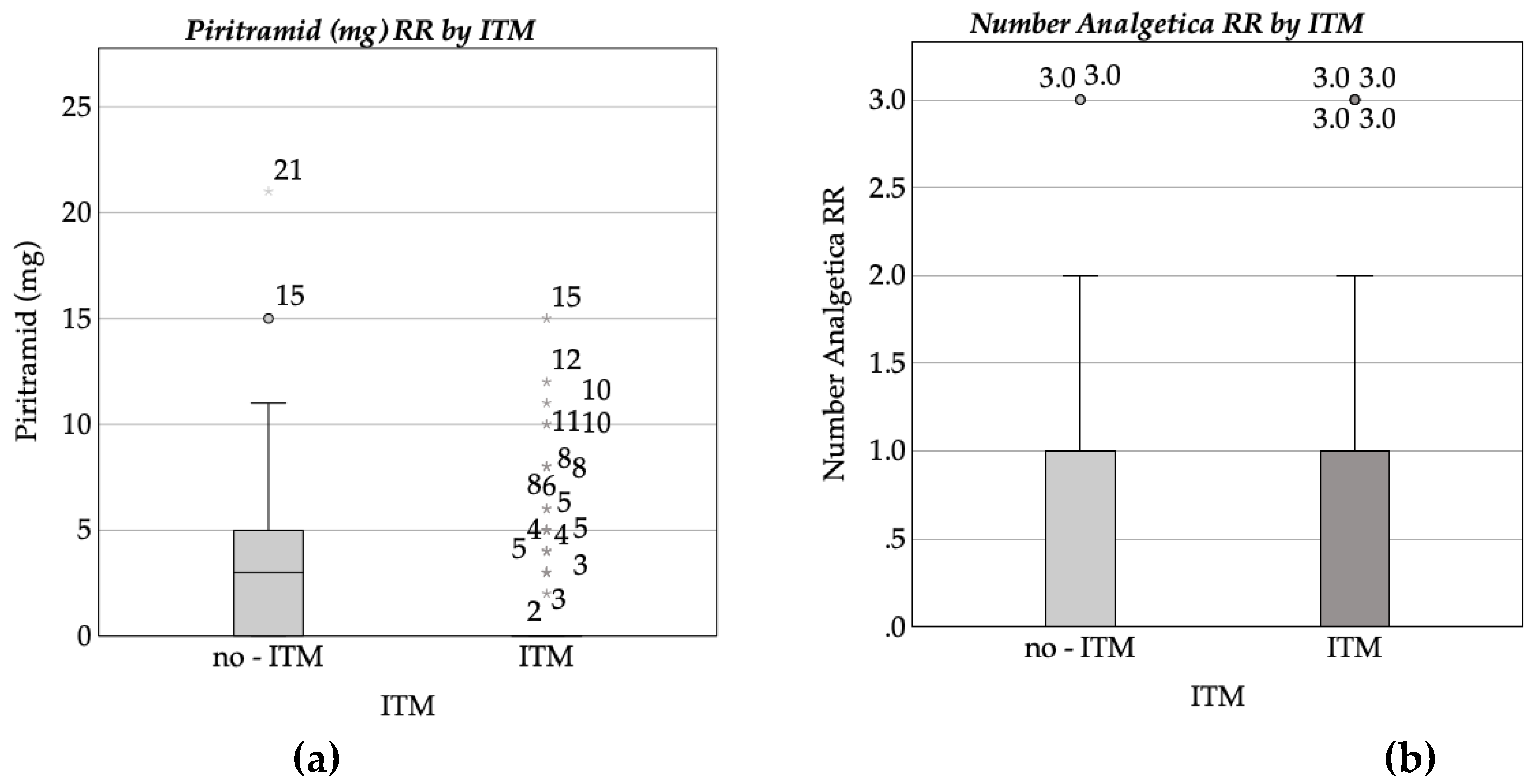

| Piritramide dosis in the recovery room | |||||||

| Coefficients | b | SE | β | t | p | ||

| (Constant) | 1.975 | 2.173 | .909 | .365 | |||

| ITM | -.380 | .362 | -.091 | -1.050 | .296 | ||

| Age | -.018 | .023 | -.071 | -.791 | .430 | ||

| Weight | .017 | .011 | .139 | 1.487 | .139 | ||

| Propofol | -.003 | .003 | -.114 | -1.158 | .249 | ||

| Midazolam | -.004 | .005 | -.078 | -.916 | .361 | ||

| Thiopental | -.004 | .006 | -.059 | -.683 | .496 | ||

| Sufentanil | .262 | .150 | .160 | 1.745 | .083 | ||

| Piritramide | -.046 | .049 | -.082 | -.939 | .349 | ||

| Fentanyl | -.319 | .957 | -.029 | -.333 | .739 | ||

| Arterial Hypertony | -.572 | .304 | -.162 | -.1884 | .0.62 | ||

| Diabetes Mellitus | -.531 | .579 | -0.80 | -.917 | .361 | ||

| Hypothyroidism | -.134 | .569 | -.020 | -.235 | .814 | ||

| COPD | .756 | .768 | -.092 | .984 | .327 | ||

| Time after ITM | -1.197E-5 | .000 | -.024 | -.277 | .782 | ||

| Remarks: N = 144; R² = .137; corr. R² = .044; F(14, 129) = .466; p = .132 | |||||||

Appendix A.2

| Number of analgetica in the recovey room | ||||||

| Coefficients | b | SE | β | t | p | |

| (Constant) | 0.883 | .924 | .955 | .341 | ||

| ITM | 0.054 | .154 | .031 | .350 | .727 | |

| Age | -0.005 | .010 | -.047 | -.516 | .607 | |

| Weight | .008 | .005 | .158 | 1.661 | .099 | |

| Propofol | -.002 | .001 | -.177 | -1.782 | .077 | |

| Midazolam | .000 | .002 | -.007 | -.082 | .935 | |

| Thiopental | -.004 | .003 | -.133 | -1.527 | .129 | |

| Sufentanil | .015 | .064 | .021 | .232 | .817 | |

| Piritramide | -.028 | .021 | -.121 | -1.362 | .175 | |

| Fentanyl | -.498 | .407 | -.108 | -1.223 | .224 | |

| Arterial Hypertony | -.223 | .129 | -.150 | -1.728 | .086 | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | -.230 | .246 | -.082 | -.932 | .353 | |

| Hypothyroidism | -.097 | .242 | -.035 | -.399 | .690 | |

| COPD | -.059 | .327 | -.017 | -.182 | .856 | |

| Time after ITM | -1.242E-5 | .000 | -.058 | .676 | .500 | |

| Remarks: N = 144; R² = .117; corr. R² = .021; F(14, 129) = 1.223; p = .266 | ||||||

Appendix A.3

| Systole at 30min | |||||

| Coefficients | b | SE | β | t | p |

| (Constant) | 118.183 | 15.395 | 7.677 | <.001 | |

| ITM | -7.471 | 3.037 | -.187 | -2.460 | .015 |

| Age | .076 | .183 | .032 | 0.413 | .680 |

| Weight | -.097 | .081 | -.092 | -1.201 | .231 |

| Arterial Hypertony | 2.853 | 2.644 | .082 | 1.079 | .282 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | .710 | 4.338 | .013 | 0.164 | .870 |

| Akinor | .039 | .180 | .016 | 0.216 | .829 |

| Atropine | -48.827 | 22.771 | -.164 | -2.144 | .033 |

| Noradrenalin | -.258 | .968 | -.020 | -0.267 | .790 |

| Remarks: N = 178; R² = .067; corr. R² = .023; F(8, 169) = 1.51; p = .156 | |||||

Appendix A.4

| Diastole at 30min | |||||

| Coefficients | b | SE | β | t | p |

| (Constant) | 74.093 | 9.475 | 7.820 | <.001 | |

| ITM | -5.426 | 1.869 | -.218 | -2.903 | .004 |

| Age | -.096 | .112 | -.064 | -.854 | .395 |

| Weight | -.044 | .050 | -.067 | -.880 | .380 |

| Arterial Hypertony | 1.649 | 1.627 | .076 | 1.014 | .312 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 2.641 | 2.670 | .075 | .989 | .324 |

| Akinor | -.106 | .110 | -.072 | -.960 | .339 |

| Atropine | -33.135 | 14.013 | -.178 | -2.365 | .019 |

| Noradrenalin | .435 | .596 | .054 | .730 | .466 |

| Remarks: N = 178; R² = .09; corr. R² = .047; F(8, 169) = 2.087; p = .039 | |||||

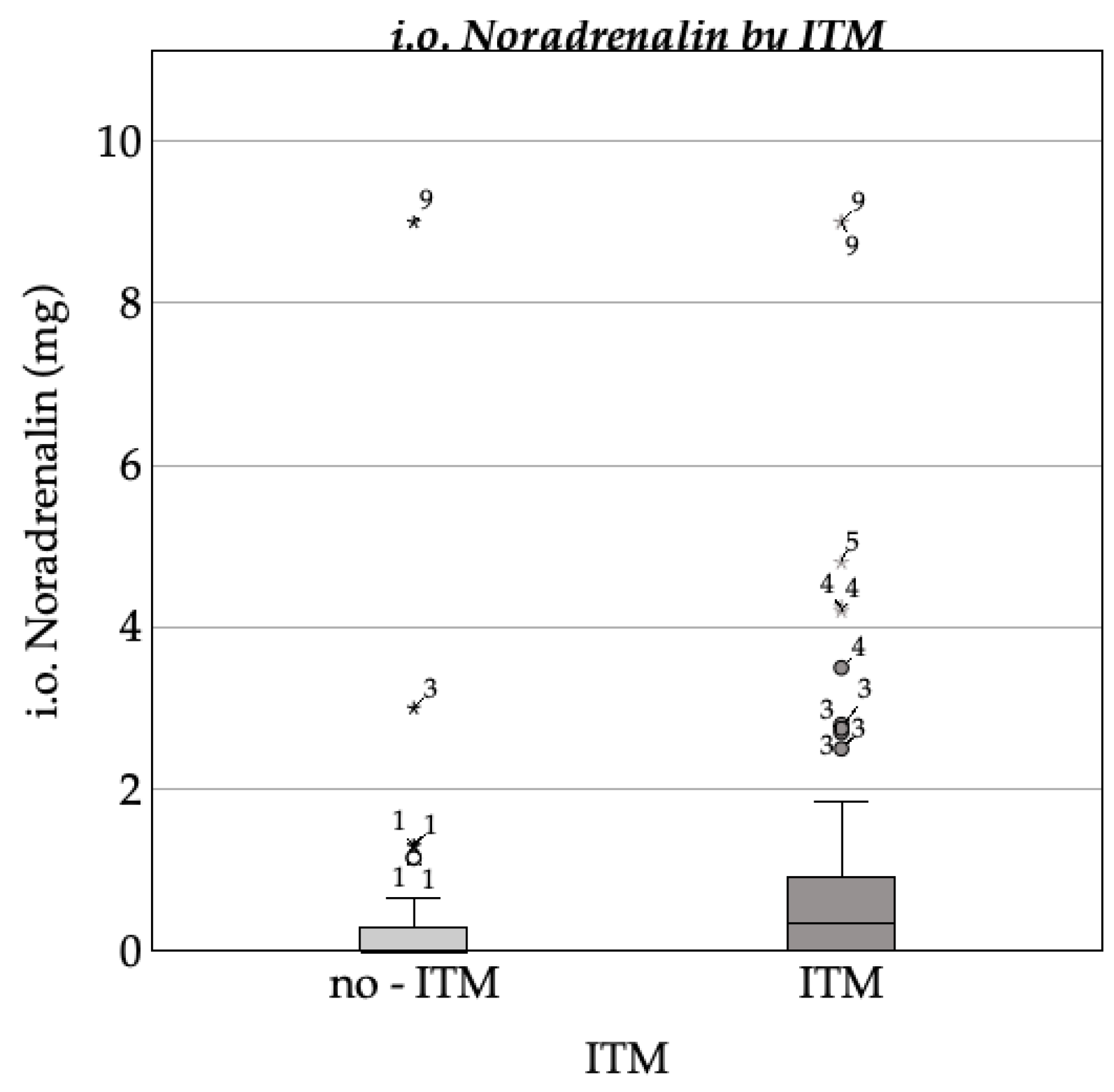

Appendix A.5

| Noradrenalin dosis | |||||

| Coefficients | b | SE | β | t | p |

| (Constant) | .706 | 1.205 | .86 | .559 | |

| ITM | .239 | .239 | .077 | .997 | .320 |

| Age | .003 | .014 | .014 | .175 | .862 |

| Weight | -.006 | .006 | -.071 | -.905 | .367 |

| Arterial Hypertony | .153 | .209 | .057 | .736 | .463 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | -.157 | .343 | -.036 | -.458 | .648 |

| Akinor | .005 | .014 | .027 | .349 | .727 |

| Atropine | -.978 | 1800 | -.042 | -.543 | .588 |

| Remarks: N = 179; R² = .019; corr. R² = -.022; F(7, 171) = .461; p = .861 | |||||

Appendix A.6

| Hospital Stay | |||||

| Coefficients | b | SE | β | t | p |

| (Constant) | 9,982 | 5.428 | 1.839 | .068 | |

| ITM | -1,743 | .952 | -.152 | -1.830 | .069 |

| Age | .008 | .057 | .012 | .146 | .884 |

| Weight | .040 | .023 | .142 | 1.731 | .086 |

| Arterial hypertension | -.676 | .794 | -.069 | -.852 | .396 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 5.262 | 1.448 | .294 | 3.635 | <.001 |

| Noradrenalin | -.040 | .277 | -.011 | -.146 | .885 |

| First in RR after Surgery | .071 | .000 | .049 | .613 | .541 |

| NRS at rest (1-10) | .412 | .554 | .154 | .744 | .458 |

| NRS at movement (1-10) | -.629 | .484 | -.263 | -1.300 | .196 |

| Days until regular ward | -1.025 | .799 | -.105 | -1.282 | .202 |

| Remarks: N = 149; R² = .174; corr. R² = .114; F(10, 138) = 2.9; p = .002 | |||||

Appendix A.7

| Nausea in the recovery room | |||||

| Coefficients | b | SE | β | t | p |

| (Constant) | .225 | .223 | 1010.000 | .314 | |

| ITM | .027 | .041 | .051 | .649 | .517 |

| Age | -.002 | .002 | -.078 | -1034.000 | .303 |

| Weight | -.001 | .001 | -.040 | -.525 | .601 |

| Pain at rest RR (NRS 1–10) | .013 | .024 | .109 | .554 | .580 |

| Pain during movement RR(NRS 1–10) | -.009 | .022 | -.077 | -.398 | .691 |

| Time until first action at RR | .000 | .000 | .002 | .031 | .975 |

| Sufentanil dose | -.003 | .016 | -.015 | -.197 | .844 |

| Fentanyl dose | .101 | .105 | .074 | .957 | .340 |

| Diabetes mellitus | -.037 | .059 | -.049 | -.621 | .535 |

| Dexamethasone | -.001 | .005 | -.011 | -.137 | .892 |

| Emesis RR | .936 | .149 | .477 | 6.272 | <.001 |

| Remarks: N = 153; R² = .259; corr. R² = .202; F(11, 141) = 4.491; p < .001 | |||||

References

- Alenezi, B.; Alsubhi, M.H.; Jin, X.; He, G.; Wei, Q.; Ke, Y. Global Development on Causes, Epidemiology, Aetiology, and Risk Factors of Prostate Cancer: An Advanced Study. Highlights Med. Med. Sci. 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottet, N.; Cornford, P.; Briers, E.; Santis, M.D.; Gillessen, S.; Grummet, J.; Henry, A.M. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG GUIDELINES ON PROSTATE CANCER. 2023, 17–21, 55–61, 85.

- Groeben, C.; Koch, R.; Baunacke, M.; Flegar, L.; Borkowetz, A.; Thomas, C.; Huber, J. Entwicklung Der Operativen Uroonkologie in Deutschland – Vergleichende Analysen Aus Populationsbasierten DatenTrends in Uro-Oncological Surgery in Germany—Comparative Analyses from Population-Based Data. Urol. 2021, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottet, N.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Briers, E.; Van den Broeck, T.; Cumberbatch, M.G.; De Santis, M.; Fanti, S.; Fossati, N.; Gandaglia, G.; Gillessen, S.; et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer-2020 Update. Part 1: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autorino, R.; Kaouk, J.H.; Stolzenburg, J.-U.; Gill, I.S.; Mottrie, A.; Tewari, A.; Cadeddu, J.A. Current Status and Future Directions of Robotic Single-Site Surgery: A Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. 2013, 63, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, D.; Djulbegovic, M.; Jung, J.H.; Hwang, E.C.; Zhou, Q.; Cleves, A.; Agoritsas, T.; Dahm, P. Prostate Cancer Screening with Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Test: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2018, 362, k3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, A.; Witdouck, A.; Beloeil, H.; Bonnet, F. ; PROSPECT Working Group Of The European Society Of Regional Anaesthesia And Pain Therapy (ESRA) PROSPECT Guidelines Update for Evidence-Based Pain Management after Prostatectomy for Cancer. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2021, 40, 100922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.L.; Rowlingson, A.J.; Partin, A.W.; Kalish, M.A.; Courpas, G.E.; Walsh, P.C.; Fleisher, L.A. Correlation of Postoperative Pain to Quality of Recovery in the Immediate Postoperative Period. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2005, 30, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, F.; Schüle, K. Bewegungstherapie Und Sport Bei Krebs. Leitfaden Für Die Praxis; Deutscher Ärzteverlag, 2008.

- Wani, M.; Al-Mitwalli, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Nabi, G.; Somani, B.K.; Abbaraju, J.; Madaan, S. Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) in Post-Prostatectomy Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghibi, K.; Saryazdi, H.; Kashefi, P.; Rohani, F. The Comparison of Spinal Anesthesia with General Anesthesia on the Postoperative Pain Scores and Analgesic Requirements after Elective Lower Abdominal Surgery: A Randomized, Double-Blinded Study. J. Res. Med. Sci. Off. J. Isfahan Univ. Med. Sci. 2013, 18, 543–548. [Google Scholar]

- Gehling, M.; Tryba, T. Risks and Side-Effects of Intrathecal Morphine Combined with Spinal Anaesthesia: A Meta-Analysis. Anaesthesia 2009, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onodera, H.; Ida, M.; Naito, Y.; Kinomoto, A.; Kawaguchi, M. Respiratory Depression Following Cesarean Section with Single-Shot Spinal with 100 Μg Morphine. J. Anesth. 2023, 37, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, G.P.; Jaschinski, T.; Bonnet, F.; Kehlet, H. ; PROSPECT collaboration Optimal Pain Management for Radical Prostatectomy Surgery: What Is the Evidence? BMC Anesthesiol. 2015, 15, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freise, H.; Van Aken, H.K. Risks and Benefits of Thoracic Epidural Anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 2011, 107, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, N.J., 1988.

- Ummenhofer, W.C.; Arends, R.H.; Shen, D.D.; Bernards, C.M. Comparative Spinal Distribution and Clearance Kinetics of Intrathecally Administered Morphine, Fentanyl, Alfentanil, and Sufentanil. Anesthesiology 2000, 92, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugabure Bujedo, B. A Clinical Approach to Neuraxial Morphine for the Treatment of Postoperative Pain. Pain Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 612145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, P.; Gutierrez, M.C.; Carvalho, B. Neuraxial Morphine and Respiratory Depression: Finding the Right Balance. Drugs 2011, 71, 1807–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, C.; Schäfer, M.; Hassan, A.H. Peripheral Opioid Receptors. Ann. Med. 1995, 27, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gregori, S.; De Gregori, M.; Ranzani, G.N.; Allegri, M.; Minella, C.; Regazzi, M. Morphine Metabolism, Transport and Brain Disposition. Metab. Brain Dis. 2012, 27, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verscheijden, L.F.M.; Litjens, C.H.C.; Koenderink, J.B.; Mathijssen, R.H.J.; Verbeek, M.M.; de Wildt, S.N.; Russel, F.G.M. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Model for the Prediction of Morphine Brain Disposition and Analgesia in Adults and Children. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1008786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koning, M.V.; Reussien, E.; Vermeulen, B.A.N.; Zonneveld, S.; Westerman, E.M.; de Graaff, J.C.; Houweling, B.M. Serious Adverse Events after a Single Shot of Intrathecal Morphine: A Case Series and Systematic Review. Pain Res. Manag. 2022, 2022, 4567192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittwer, E.; Kern, S.E. Role of Morphine’s Metabolites in Analgesia: Concepts and Controversies. AAPS J. 2006, 8, E348–E352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrieu, G.; Roth, B.; Ousmane, L.; Castaner, M.; Petillot, P.; Vallet, B.; Villers, A.; Lebuffe, G. The Efficacy of Intrathecal Morphine With or Without Clonidine for Postoperative Analgesia After Radical Prostatectomy. Anesth. Analg. 2009, 108, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurzova, A.; Malek, J.; Klezl, P.; Hess, L.; Sliva, J. A Single Dose of Intrathecal Morphine Without Local Anesthetic Provides Long-Lasting Postoperative Analgesia After Radical Prostatectomy and Nephrectomy. J. Perianesth. Nurs. 2024, 39, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathmell, J.P.; Lair, T.R.; Nauman, B. The Role of Intrathecal Drugs in the Treatment of Acute Pain. Anesth. Analg. 2005, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbek, H.; Deniz, M.N.; Erakgun, A.; Erhan, E. Comparison of 75 and 150 Μg Doses of Intrathecal Morphine for Postoperative Analgesia after Transurethral Resection of the Prostate under Spinal Anesthesia. J. Opioid Manag. 2013, 9, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meylan, N.; Elia, N.; Lysakowski, C.; Tramèr, M.R. Benefit and Risk of Intrathecal Morphine without Local Anaesthetic in Patients Undergoing Major Surgery: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Br. J. Anaesth. 2009, 102, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zand, F.; Amini, A.; Asadi, S.; Farbood, A. The Effect of Methylnaltrexone on the Side Effects of Intrathecal Morphine after Orthopedic Surgery under Spinal Anesthesia. Pain Pract. Off. J. World Inst. Pain 2015, 15, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koning, M.V.; Klimek, M.; Rijs, K.; Stolker, R.J.; Heesen, M.A. Intrathecal Hydrophilic Opioids for Abdominal Surgery: A Meta-Analysis, Meta-Regression, and Trial Sequential Analysis. Br. J. Anaesth. 2020, 125, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwirtz, K.H.; Young, J.V.; Byers, R.S.; Alley, C.; Levin, K.; Walker, S.G.; Stoelting, R.K. The Safety and Efficacy of Intrathecal Opioid Analgesia for Acute Postoperative Pain: Seven Years’ Experience with 5969 Surgical Patients at Indiana University Hospital. Anesth. Analg. 1999, 88, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.; Goldstein, D.H.; VanDenKerkhof, E.G. Definitions of “Respiratory Depression” with Intrathecal Morphine Postoperative Analgesia: A Review of the Literature. Can. J. Anaesth. 2003, 50, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deer, T.R.; Pope, J.E.; Hayek, S.M.; Lamer, T.J.; Veizi, I.E.; Erdek, M.; Wallace, M.S.; Grider, J.S.; Levy, R.M.; Prager, J.; et al. The Polyanalgesic Consensus Conference (PACC): Recommendations for Intrathecal Drug Delivery: Guidance for Improving Safety and Mitigating Risks. Neuromodulation J. Int. Neuromodulation Soc. 2017, 20, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prager, J.; Deer, T.; Levy, R.; Bruel, B.; Buchser, E.; Caraway, D.; Cousins, M.; Jacobs, M.; McGlothlen, G.; Rauck, R.; et al. Best Practices for Intrathecal Drug Delivery for Pain. Neuromodulation J. Int. Neuromodulation Soc. 2014, 17, 354–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhawan, R.; Daubenspeck, D.; Wroblewski, K.E.; Harrison, J.-H.; McCrorey, M.; Balkhy, H.H.; Chaney, M.A. Intrathecal Morphine for Analgesia in Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blinded Clinical Trial. Anesthesiology 2021, 135, 864–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thay, Y.; Goh, Q.; Han, R.; Sultana, R.; Sng, B. Pruritus and Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting after Intrathecal Morphine in Spinal Anaesthesia for Caesarean Section: Prospective Cohort Study. Proc. Singap. Healthc. 2018, 27, 201010581876034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauri, D.; Jäger, P. Checkliste Urologie, 4th ed.; Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, 2000.

- Gardner, T.A.; Bissonette, E.A.; Petroni, G.R.; McClain, R.; Sokoloff, M.H.; Theodorescu, D. Surgical and Postoperative Factors Affecting Length of Hospital Stay after Radical Prostatectomy. Cancer 2000, 89, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).