1. Introduction

With the advancement of virtual reality (VR) technology, its applications have been expanding across various fields [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In particular, improvements of head-mounted display (HMD) devices have significantly enhanced the sense of immersion [

6], increasing demand for highly realistic virtual environments [

7]. Consequently, there is growing interest in interactions within three-dimensional (3D) virtual spaces that extend beyond conventional 3D virtual environments by incorporating physics-based mechanics that reflect real-world physical principles.

In virtual environments, when unintended actions occur during task execution, users often attempt to revert to a previous state using the undo function, a capability that is not available in the physical world. The undo function is an essential feature in virtual environments [

8], enabling users to quickly recover from unintentional operations or errors [

9,

10]. Its necessity can be emphasized from four key perspectives. First, from the perspective of error recovery [

11], users can instantly reverse unintended operations or system errors that may occur during interactions. This minimizes task interruptions, ensures workflow continuity, and ultimately enhances overall task efficiency. Second, from the perspective of performance retrace [

12], users can review previous task stages to assess their performance or analyze work process. This feature is particularly useful for learning, analysis, and optimization, contributing to the improvement of task quality. Third, from the perspective of applying changes in plan, when task plans need to be modified or new direction must be adopted, the undo function allows for effective adjustments and seamless integration of revised plans. Finally, from the viewpoint of usability enhancement, the undo function provides users with a sense of reliability and convenience, thereby improving the overall usability.

In traditional 2D environments, interactions with target objects (or groups of objects) are performed using a keyboard and mouse, with interaction histories stored in a linear sequence [

13]. Since user interactions occur explicitly in response to user commands, control is relatively straightforward, and the scope of the undo function is clearly defined.

In contrast, in realistic physics-based 3D virtual environments, objects are influenced by physical forces such as impact forces, gravity, and friction. As a result, unintended interactions may occur not only between the user and a specific object but also among multiple objects within the environment. This significantly increases the likelihood of errors compared to 2D environments, further underscoring the necessity of an effective undo function in 3D environments.

In 2D environments, interactions are explicitly triggered by user commands, and their effects are confined to specific objects or object groups, making the scope of the undo function clearly defined. However, in physics-based 3D virtual environments, the influence of physical forces can lead to unintended cascading interactions across multiple objects, even from a single user action. Therefore, an undo function in such an environment must not only restore the state of a specific object but also revert a series of unintended interactions resulting from the initial interaction. Due to these inherent complexities, conventional undo mechanisms designed for 2D environments cannot be directly applied to physics-based 3D virtual environments. Consequently, a novel undo mechanism tailored to the dynamic interactions of physics-based 3D virtual environments is required.

Several studies have explored the implementation of undo functionality in 3D virtual environments. Müller et al. proposed undo actions for locomotion that allow users to quickly return to a previous point in a VR environment [

14]. However, this study was limited to undo mechanisms for locomotion and did not address broader application in general 3D interactions. Rasch et al. investigated appropriate undo strategies for multi-user VR environments, proposing design recommendations for implementing multi-user undo in Computer-Supported Cooperative Work(CSCW) environments [

15]. However, this study primarily focused on undo techniques with multi-user collaborative environments, without addressing undo mechanisms for effectively reverting cascading object interactions in physics-based 3D virtual spaces. Despite existing research on undo mechanisms, studies that can efficiently handle unintended cascading interactions among objects in physics-based 3D virtual environments remain insufficient.

Therefore, this study proposes a novel undo mechanism that account for cascading interactions occurring in physics-based 3D virtual environments. Furthermore, the proposed undo mechanism is evaluated through a user study to assess its efficiency and usability.

The contributions of this study are as follows:

We proposed Action-based Undo, a novel 3D undo mechanism designed to effectively revert cascading object interactions caused by physical forces in physics-based 3D virtual environments.

We analyze the impact of the proposed 3D undo mechanism on task efficiency and usability in 3D virtual spaces.

Through a user study, we validate that Action-based Undo enhances task efficiency and usability compared to conventional undo techniques.

2. Related Work

Kim et al. [

16] designed a history tool for undoing hand-based interactions in 3D virtual environments. This study presents the necessity of a new history tool that offers a distinct user experience compared to conventional 2D applications, distinguishing itself from prior research that primarily emphasized the importance of undo functionality in 3D virtual environments. While previous studies have emphasized the need for undo functionality in 3D virtual environments, discussions on user experience with the history tool and the specific contexts in which the tool is applied have been limited. To bridge this gap, a pilot study was conducted, demonstrating the tool's usefulness in tasks such as modifying past commands to resolve errors, creating alternative versions, and re-executing failed processes.

The undo function, once limited to desktop systems, is now a widely adopted and commercialized feature across multiple platforms, including mobile devices. However, research on undo functionality in VR environments remains in its early stages, with existing studies primarily focused on conceptualizing undo in VR and exploring its applications. For instance, Müller et al. proposed an extended point-and-teleport method as an undo mechanism to address challenges associated with locomotion in VR environments, such as disorientation, performance degradation, and difficulties in acquiring spatial knowledge [

14]. Their study introduced three undo concepts: position undo, orientation undo, and movement visualization. Eight experimental conditions were designed to examine different combinations of these concepts. The findings revealed that the proposed undo mechanism effectively enabled users to return to previously visited locations more efficiently. However, this research primarily focused on improving locomotion in VR environments and did not address undo functionality for virtual object manipulation.

Meanwhile, Rasch et al. conducted a study on undo functionality for multi-user object manipulation in 3D virtual spaces [

15]. The research compared three distinct undo techniques -Individual Undo, Selective Undo, and World Undo– as well as no-undo condition across two modes of collaboration: divided mode, where participants work in separate spaces, and collaborative mode, where they interact within a shared virtual environment. Individual Undo allows users to linearly undo only their own actions. Selective Undo enables users to selectively undo specific objects using a ray-based selection mechanism. World Undo provides a linear undo of all actions performed within the environment, while the no-undo condition represents a setting without any undo functionality.

The study analyzed participants' satisfaction and willingness to use each undo technique in the future, evaluating how different collaboration modes influenced user experience in terms of efficiency, recoverability, and intuitiveness. The findings demonstrated that undo functionality in collaborative VR tasks significantly aids error recovery, thereby reducing user frustration and task load. Furthermore, the study suggested that the most suitable undo technique may vary depending on the social dynamics of the VR scene and the specific task objectives.

However, previous studies have not directly addressed undo techniques that accommodate physics-driven interactions in a 3D virtual environments. In particular, research on the effective implementation of undo functionality for cascading object movements caused by physical forces, such as gravity or impact forces, remains insufficient.

Accordingly, this study aims to investigate and propose an undo technique for physics-based 3D virtual environments involving a single user. The proposed method seeks to efficiently reverse unintended cascading interactions between objects, triggered by forces like gravity, to restore the environment to its prior state.

3. 3D Undo

In a 2D virtual environment, the outcomes of interactions are limited exclusively to the target object with which the user intended to interact. Consequently, the undo operations in such environments can be performed by reverting only the state of the target object. Similarly, 3D virtual environments that do not incorporate physical properties can be handled interactions using the same principles as 2D undo mechanisms.

However, in physics-based 3D virtual environments, real-world physical forces such as gravity and friction, influence object interactions. As a result, a single interaction may trigger a cascading effect that extends beyond the intended target object, affecting surrounding objects. This cascading interaction, driven by external physical forces, can cause multiple objects to respond in unintended and unpredictable ways.

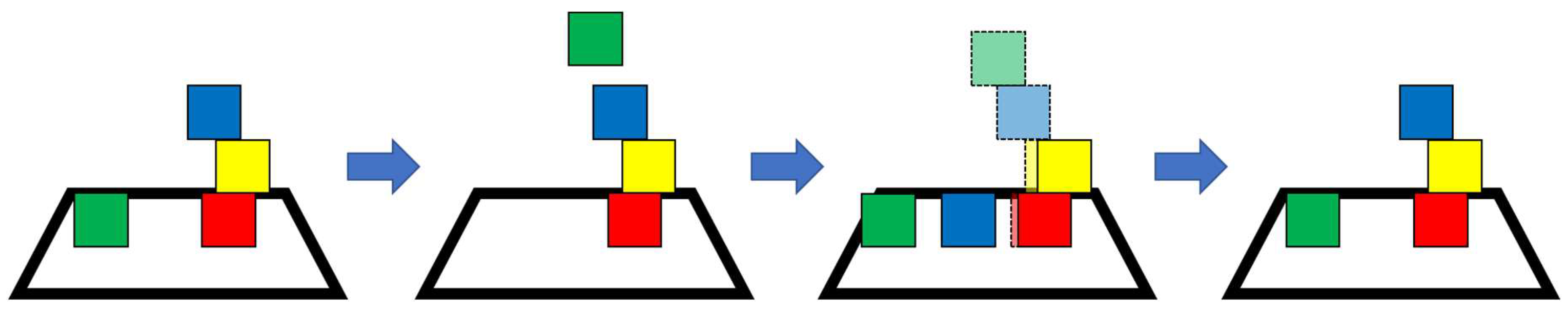

Thus, implementing undo functionality in physics-based 3D environments requires more than simply restoring the state of an individual object. It must also recover all dependent actions, which are secondary interactions triggered by the initial action. For instance, as illustrated in

Figure 1, if manipulating a single object inadvertently causes the movement of other objects, applying undo only to the manipulated object will be insufficient to restore the environment to its original state. Therefore, an effective 3D undo mechanism must revert both the intended action and any subsequent dependent actions.

This study examine the fundamental components required for implementing undo functionality in physics-based 3D environments and propose a systematic method for managing interaction dependencies during the undo process.

3.1. History System for 3D Undo

To implement undo functionality effectively, interactions occurring in a virtual environment must be stored in appropriately structured units. In this study, an Action is defined as a distinct unit of interaction that results in changes in the environment. An Action is initiated when an object's state begins to change and is completed when the object’s state stabilizes. Each Action consists of two key elements: the intended action and the dependent action. The intended action refers to the direct interaction performed by the user on a specific object, whereas the dependent action refers to any additional interactions that arise from or are indirectly triggered by the intended action.

An effective 3D undo mechanism must not only restore the state of the target object affected by the intended action but also properly handle all objects influenced by the dependent actions. Therefore, defining the structure of an Action and systematically managing the relationships between intended actions and dependent actions is essential for ensuring accurate and consistent undo operations in physics-based 3D virtual environments.

The conventional method of recording history involves logging all actions associated with each object individually. However, this approach presents several issues. First, there is the problem of the exponential growth in history units. In a 3D environment where multiple objects and interactions are involved, recording every action for each object separately lead to a rapid increase in storage requirement. This exponential growth imposes significant burdens on both storage capacity and processing efficiency. Second, undo execution inefficiency arises. Even when a user performs a single interaction, multiple related actions must be undone sequentially, which can negatively impact system performance and degrade user experience.

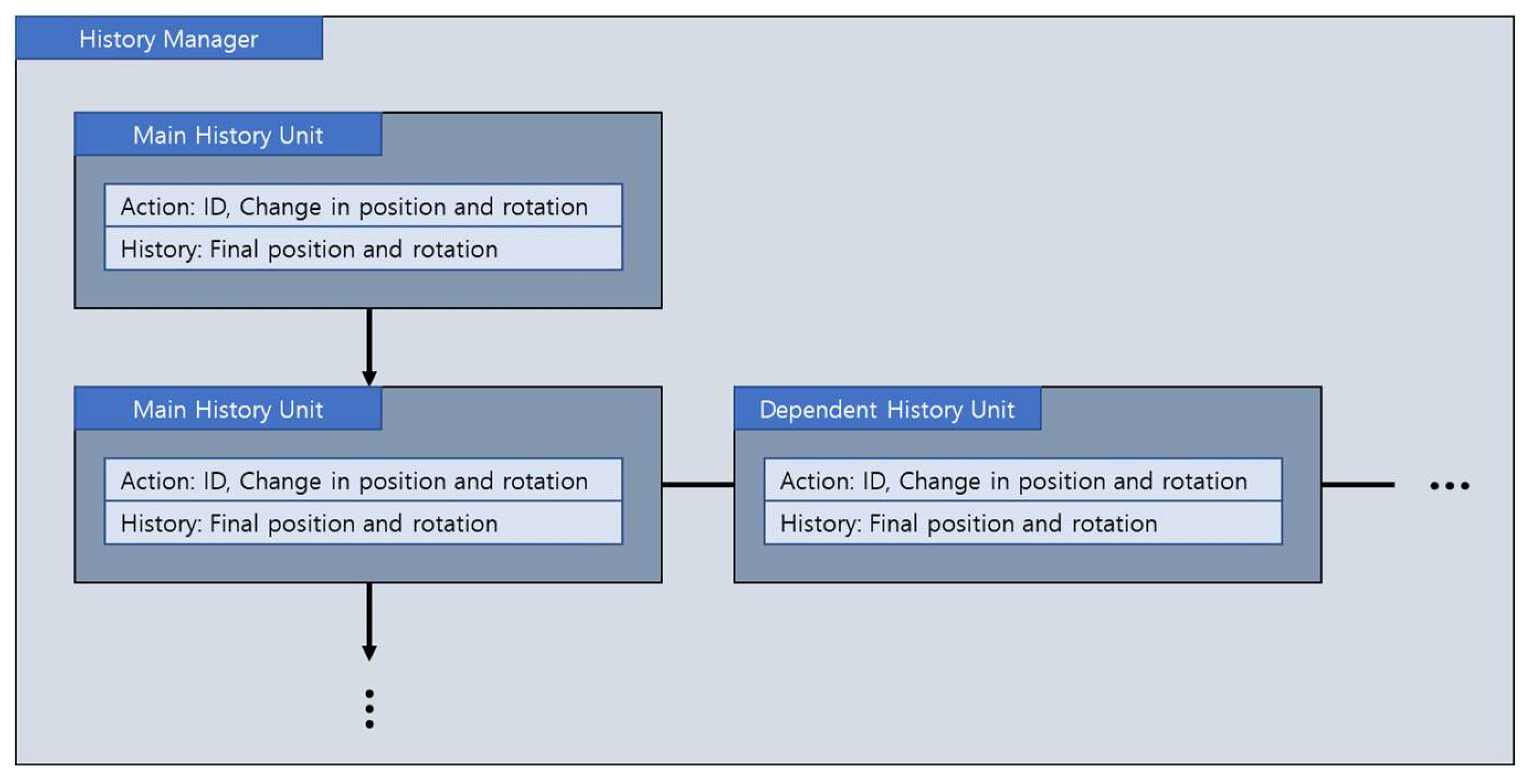

In this study, the fundamental storage unit for interactions in the 3D undo system is defined as an Action. An Action is created at the moment when a state change of a specific object begins, and it stores the changes in the object’s position and rotation once the object comes to rest. A History retains the final position and rotation values of the object after the Action is completed. A History unit serves as the storage entity that records both the Action from the initiation to the termination of an interaction and the corresponding History with a specific object. The History Manager is responsible for storing and managing each History unit across interactions, thereby facilitating the execution of 3D undo operations.

When 3D undo is provided, users operate in two distinct modes: Object Manipulation and History Manipulation. In Object Manipulation mode, users directly manipulate objects, changing their position and rotation through interactions. During this process, new Actions and Histories are generated, leading to the creation of new History units. These generated History units are stored and managed by the History Manager. History Manipulation mode is the step where users perform undo operations on interactions previously executed in Object Manipulation mode. In this mode, all physical interactions and object-to-object interactions are restricted, ensuring that no new Actions are generated. Users reconstruct the desired state by executing undo and redo operations based on the stored History. Once the desired state is reached, users confirm the state through a history confirmation step and then return to Object Manipulation mode to continue interactions.

3.2. Action-Based Undo

This study proposes an Action-based Undo technique that manages history based on the user interactions, specifically focusing on the intended actions, to enable efficient 3D undo functionality. A key feature of this technique is its hierarchical management of all dependent actions triggered by an intended action.

In the proposed Action-based Undo system, the History Manager generates and stores History units based on the objects affected by the user’s intended actions. The History unit created from an intended action is defined as the Main History Unit, while the movement data of objects influenced by the dependent actions triggered by the intended action are stored as Dependent History Units in a hierarchical structure. This structured relationship between the Main History Unit and Dependent History Units systematically manages the dependencies among actions. Consequently, when a user performs an undo operation, the intended action and all associated dependent actions are restored in a single operation. This approach provides several advantages for effectively tracking and restoring interactions in a 3D environment. First, users can perform undo operations at the level of the interaction unit (i.e. the intended action). Second, unlike traditional undo methods in 3D environments, which often suffer from exponential growth in history caused by cascading interactions, the proposed Action-based Undo technique efficiently manages history records. Lastly, the system performance is enhanced by restoring multiple object states through a single undo operation, minimizing computational overhead and improving execution efficiency.

Figure 2.

Structure of Action, History, History Unit and History Manager in Action-based Undo.

Figure 2.

Structure of Action, History, History Unit and History Manager in Action-based Undo.

The proposed Action-based Undo approach is designed based on the following assumptions. First, an intended action occurs on a single object at a time, meaning that user manipulates only one object per interaction. Second, all dependent actions associated with a previous intended action must be completed before a new intended action begins. This assumption ensures clarity and consistency in history management.

4. Evaluation Methodology

4.1. Experiment Setup

We developed the 3D undo system and experimental environment using Unity 2022.3.11f1. The experiment utilized the HTC Vive Pro HMD, along with its default controllers and base stations. The experimental tasks were executed on a desktop PC equipped with an Intel Core i7-7700K CPU @ 4.20GHz, 32GB of RAM, an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1070 GPU, and running Windows 10.

4.2. User Study

4.2.1. Participants

We recruited 24 participants (15 females and 9 males), with ages ranging from 23 to 35 years (M = 26.5, SD = 3.48). Regarding experience with AR/XR/VR devices, 9 participants had little to no prior experience, and none had used such devices more than five times.

4.2.2. Experiment Design

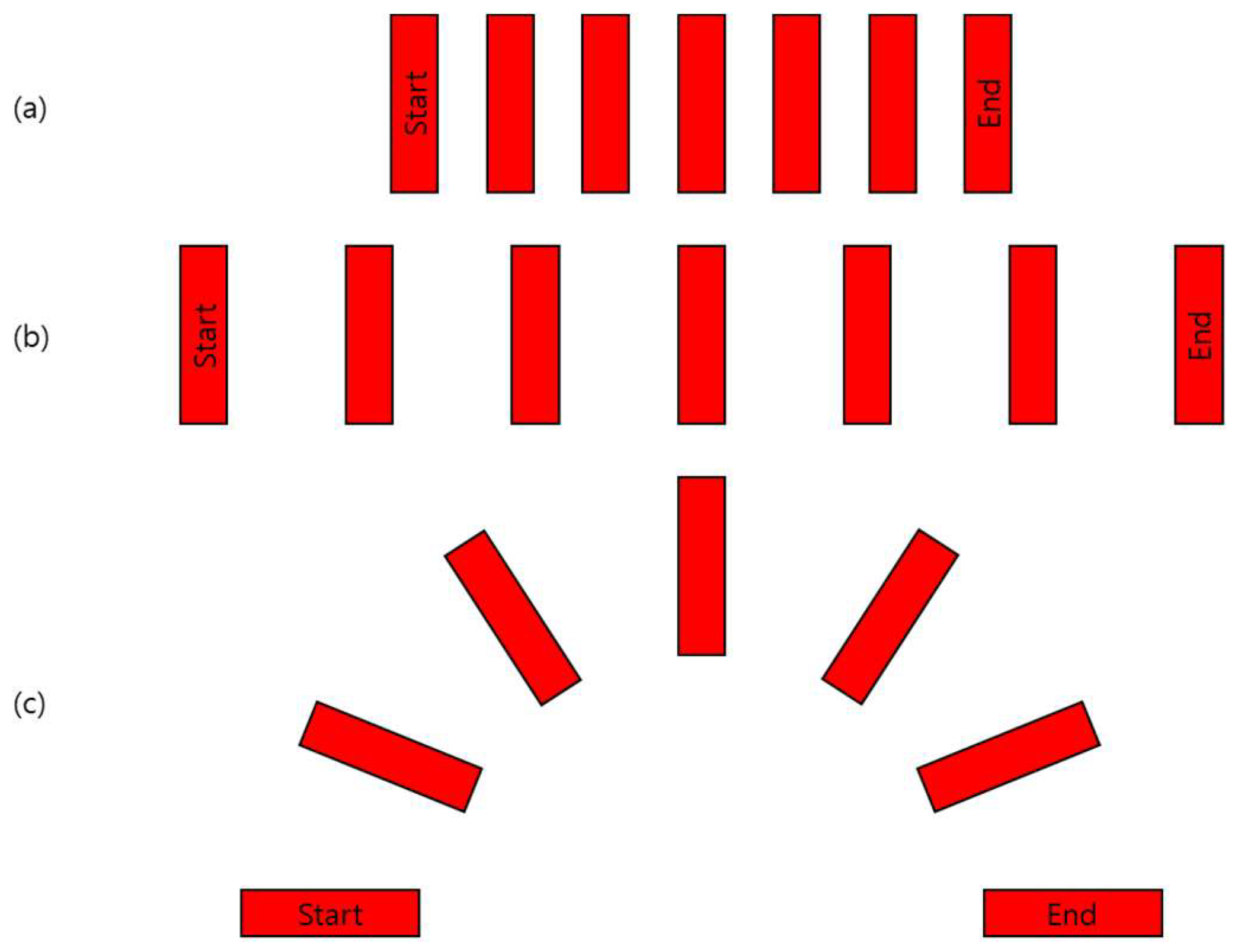

To create a realistic 3D virtual environment, the experimental setup incorporated physical forces such as gravity and friction. This experiment involved a task where a single interaction triggered a series of subsequent interactions, performed through the following domino tasks. At the start of each trial, a start domino block was positioned at the leftmost end, and an end domino block was placed at the rightmost end. Participants were required to place five additional domino blocks at the center, between the start and end blocks, ensuring appropriate spacing for proper toppling. When the participant toppled the start block, all the domino blocks, including the end block, fell sequentially. The experimental task was completed by resetting all fallen domino blocks to their original upright positions.

The experiment included three different placement configurations, each varying the distance and arrangement between the start and end blocks. In the first and second tasks, the domino blocks were arranged in a straight line. The second task increased the distance between the start and end blocks compared to the first task. In the third task, the distance between the start and end blocks was reduced, but the start block was tilted at -90 degrees, and the end block was tilted at 90 degrees. In this case, the domino blocks had to be arranged in curved pattern resembling a semicircle to ensure all blocks fall successfully. To assist participants and to facilitate task completion, a central guideline was provided as a visual aid.

Figure 3.

Expected domino arrangement for (a) Task 1, (b) Task 2, and (c) Task 3.

Figure 3.

Expected domino arrangement for (a) Task 1, (b) Task 2, and (c) Task 3.

For each configuration, participants were required a set up all domino blocks, trigger the start block to topple all blocks up to the end block, and then reset all blocks to their upright positions. This process marked the completion of the task for each configuration.

4.2.3. Undo Methods

Before verifying the efficiency and usability of the proposed Action-based Undo method in a 3D virtual environment, this study also designed and implemented an Object-based Undo mechanism, similar to the undo functionality found in traditional 2D computer environments. Object-based Undo operates with individual objects as the unit of undo operations. When an object’s movement occurs, the movement information is defined as an Action and History, forming a History unit that is systemically managed. The Object-based Undo system consists of two management modules: Global History Manager and Object History Manager. The Global History Manager is a singular entity within the system that stores only the names (identifiers) of objects in the order their actions are completed. In contrast, the Object History Managers is a separate history manager for each individual object in the system. the number of Object History Managers corresponds to the number of objects in the system, with each managing its respective object's movement data by defining actions and histories to create and maintain History units. These history units are stored in the respective object's history manager in the order of action completion. The definitions of action, history, and history unit in this mechanism remain consistent with those used in the Action-based Undo system.

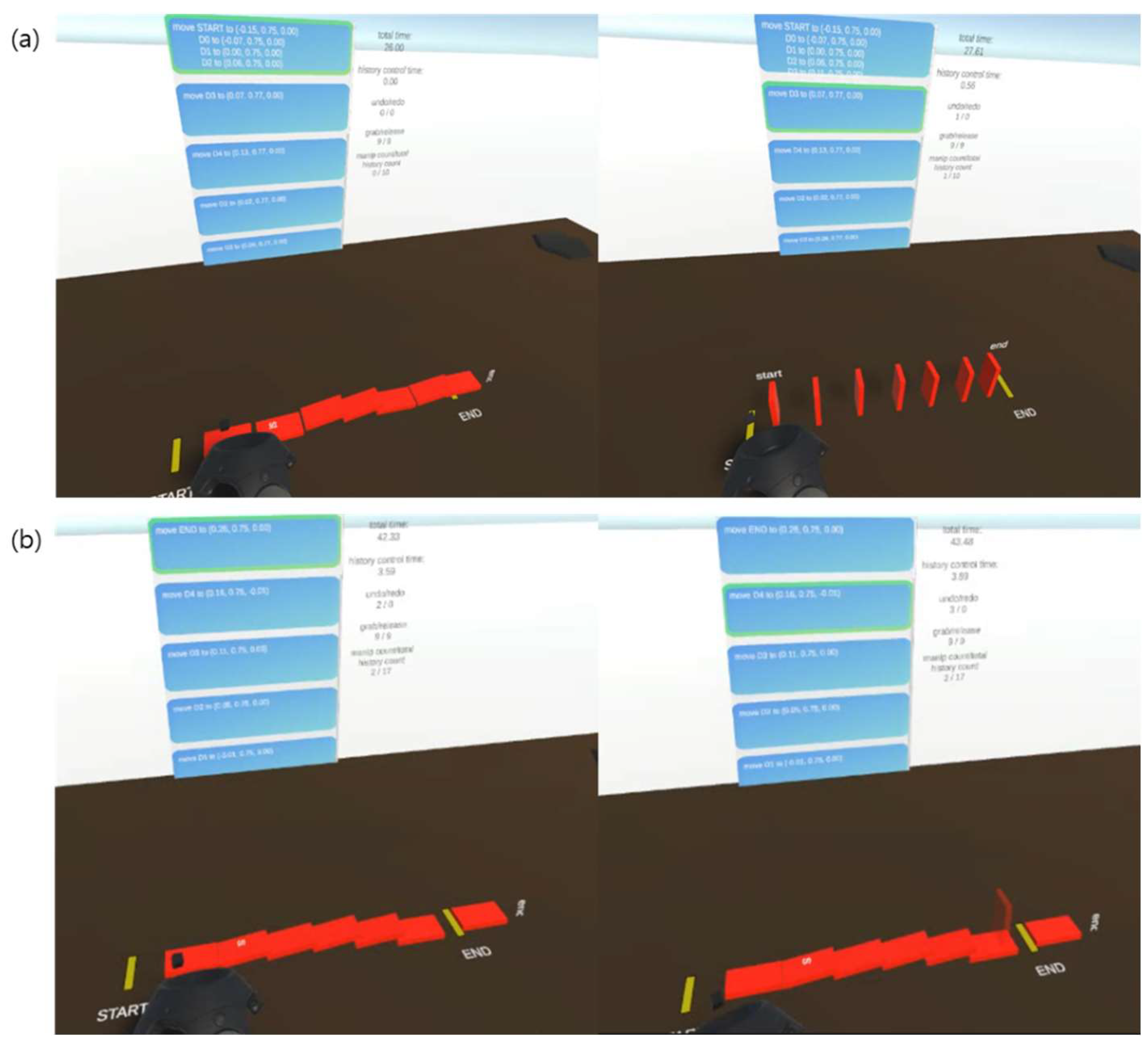

Figure 4.

State after the toppling of dominoes and after single execution of (a) Action-based Undo, (b) Object-based Undo.

Figure 4.

State after the toppling of dominoes and after single execution of (a) Action-based Undo, (b) Object-based Undo.

When a user performs an undo operation, the system references the Global History Manager to identify the most recently modified object and then accesses the corresponding Object History Manager to execute the undo operation. Consequently, each undo operation restores only the most recent action performed on a specific object, operating at the individual object level and reverting only the last action associated with that object.

To evaluate the efficiency and usability of the proposed Action-based Undo method in a 3D virtual environment, this study compared three methods: No Undo, Object-based Undo, and Action-based Undo.

No Undo, as the name suggests, does not provide any undo functionality. Users cannot revert to a previous state, even if an unintended action occurs and must manually manipulate objects to recreate the desired state.

In the Object-based Undo method, the undo operation is performed at the level of a single action on a single object. Since no action dependency exists between consecutive interactions, each object's movement is stored in its respective History unit. Thus, executing an undo command reverts only the most recently completed action on the last modified object, in reverse chronological order. This method performs undo operations in the same manner as traditional 2D environments, allowing the study to assess the efficiency and usability when applying this approach in a 3D virtual environment.

The Action-based Undo method performs undo operations based on the user’s intended actions. All dependent actions resulting from an intended action are managed hierarchically as dependencies. When an undo command is executed, the intended action along with all its dependent actions are simultaneously reverted. Due to this dependency structure between actions, a single undo command can restore the states of multiple objects at once.

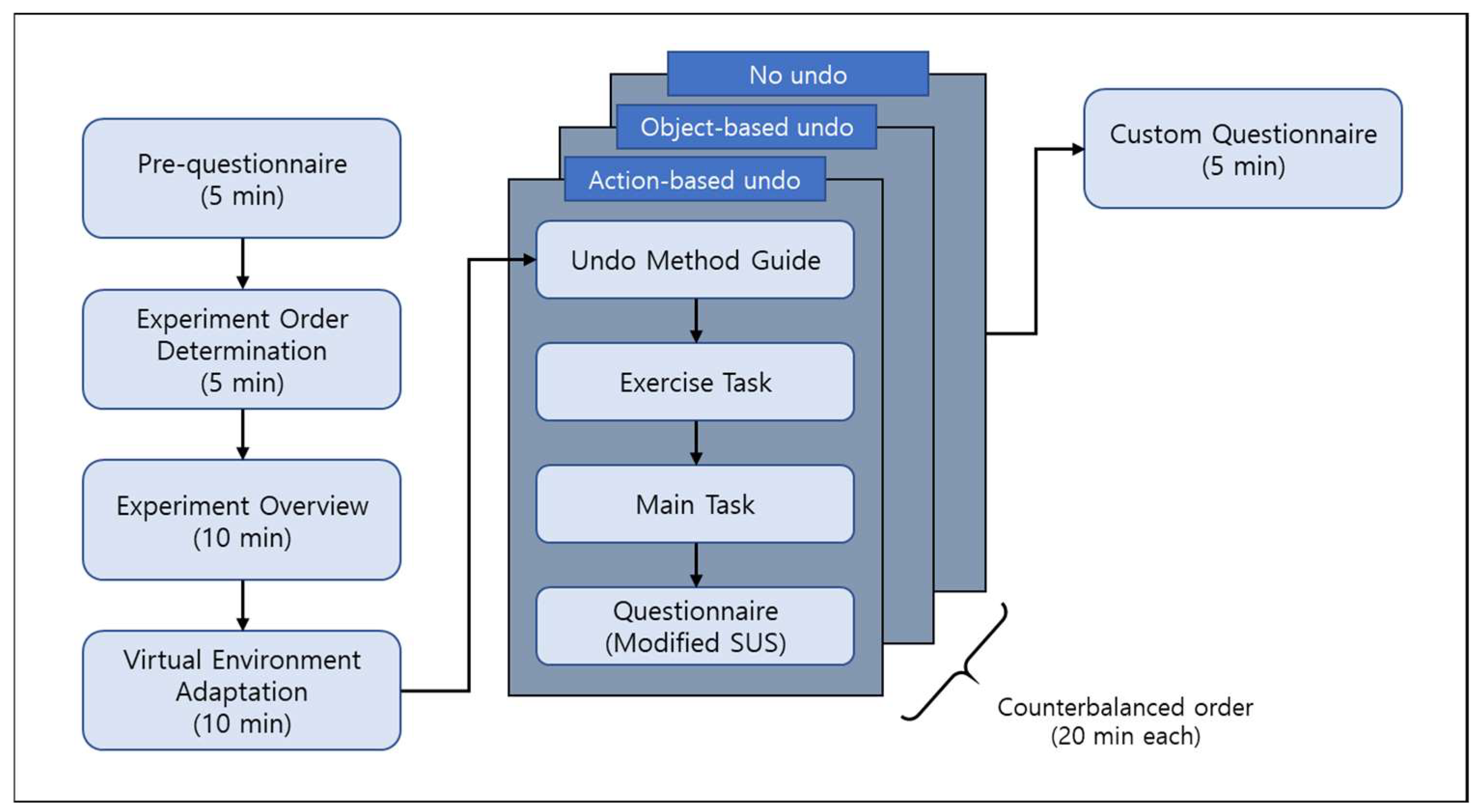

4.2.4. Experiment Procedure

Prior to the experiment, participants completed a pre-questionnaire to collect basic information including name, age, gender, and prior experience with VR. To ensure a counterbalanced experimental design, the order of the three undo methods used as control conditions—Action-based Undo, Object-based Undo, and No Undo— was randomly determined. Once the experimental order was established, participants received a preliminary briefing outlining the purpose and overall procedure of the experiment. Following the briefing, participants were given time to familiarize themselves with the virtual environment in which the experiment would be conducted.

Figure 5.

A Diagram of Experiment Procedure.

Figure 5.

A Diagram of Experiment Procedure.

Before the main experiment, two preparatory exercises were performed to allow participants to acclimate to the 3D virtual environment and the domino block task. In the first exercise, participants were instructed to arrange domino blocks in a straight line between a designated start block and an end block within the virtual environment. In the second exercise, participants performed the same task but arranged the domino blocks in a curved pattern between the same starting and ending blocks, both of which were tilted outward. Participants were guided to place the domino blocks at appropriate intervals to ensure that toppling one block would result in a continuous chain reaction. To assist in accurate block placement and facilitate the exercise, a central guideline was provided along the designated placement path. Upon completing the arrangement, participants initiated the toppling sequence by lightly striking the starting block and observing the resulting chain reaction. The exercise was considered complete once all blocks had fallen and were subsequently reset to their original positions. During these preparatory exercises, no undo functionality was provided.

Upon completing the preparatory exercises, the main experiment commenced. The experiment was conducted three times in a predetermined order, following the sequence outlined below: 1) Participants received an introduction to the current undo method, including an explanation of its features and usage instructions. 2) Participants performed an exercise task using the current undo method to familiarize themselves with its operation. 3) Participants performed the main experimental task, which involved a domino arrangement using the designated undo method. 4) Upon completing the domino task, participants filled out a Modified System Usability Scale (SUS) questionnaire regarding their experience with the current undo method. 5) The experiment proceeded to the next undo condition. After completing the experiment for all three undo conditions, participants responded to a custom questionnaire designed to gather feedback on which undo method they found most effective in different situations.

4.2.5. Evaluation Metrics

4.2.5.1. Quantitative Measurements

To evaluate the efficiency of the proposed method, the following metrics were measured. The experiment was conducted three times with different configurations, and the following metrics were assessed for each trial:

Completion Time (Undo Time): The total time required to reset all fallen domino blocks, measured from the moment the start domino block was toppled to the point when all blocks were reset to their upright positions.

Number of Interactions: The total number of interactions (e.g., undo, redo, or block manipulation) used to reset all fallen domino blocks. This specifically represents the number of history manipulation actions performed during undo operations for Action-based Undo and Object-based Undo. For No Undo condition, number of block manipulation is counted as number of interactions.

4.2.5.2. Subjective Measurements

Modified System Usability Scale (SUS): To evaluate usability, a questionnaire was developed by modifying items based on System Usability Scale (SUS). The questionnaire consisted of 12 items and was evaluated on a five-point scale where 1 is "strongly disagree" and 5 is "strongly agree.". There were six positive (odd-numbered) questions and six negative (even-numbered) questions on six items, including ease of use, learnability, naturalness, comfort, efficiency, and usability. This evaluation was conducted at the end of each trial for each method.

Custom Questionnaire: A single survey conducted after completing all experiments for all undo methods to evaluate user preferences regarding each undo technique. Participants were asked to choose the most appropriate undo method (Action-based Undo, Object-based Undo, or No Undo) for various questions. The questions are as follows:

Table 1.

Categories and list of questions for Custom Questionnaire.

Table 1.

Categories and list of questions for Custom Questionnaire.

| Category |

Question |

| Helpfulness |

Which of the three provided undo methods helped you perform tasks more easily? |

| Preference |

Which of the three provided undo methods do you prefer the most? |

| Satisfaction |

Which of the three provided undo methods were you most satisfied with? |

| Clarity |

Which of the three provided undo methods made it most clear what you were undoing? |

| Effectiveness |

Which undo method helped you perform the domino application quickly and accurately? |

| Usefulness |

Which undo method was most useful in achieving your goal? |

| Ease of use |

Which of the three provided undo methods was the easiest to use? |

| Best undo |

Which of the three provided undo methods was the best for undoing a task, and why? |

5. Results

In this section, we present the analysis results of differences in the dependent variables according to the three experimental conditions: Action-based Undo, Object-based Undo, and No Undo.

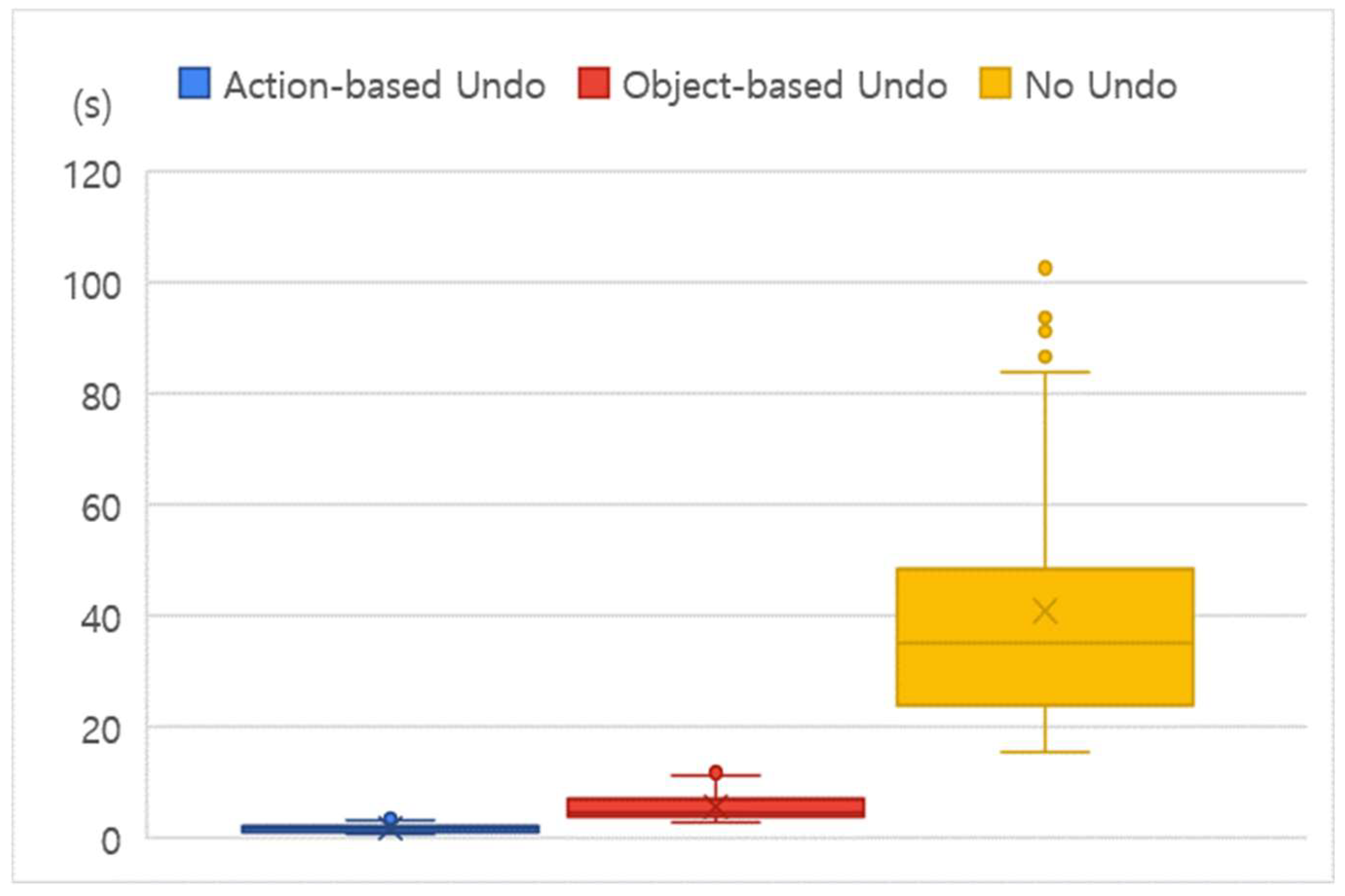

5.1. Undo Time

To evaluate participants’ efficiency in using the undo function, we measured the domino undo time, which refers to the time required to restore toppled dominoes to their original upright position. The results indicated that participants using the Action-based Undo method completed the task significantly faster than those in the Object-based Undo and No Undo conditions. Specifically, the mean completion time for the Action-based Undo was M = 1.65 s (SD = 0.837), whereas the Object-based Undo and No Undo conditions showed a mean time of M = 40.8 s (SD = 20.9).

To test the normality of the data distributions, we conducted the Shapiro–Wilk test, which indicated that none of the three conditions followed a normal distribution (p < .05). Accordingly, we performed a Friedman test, which revealed a statistically significant difference (2) = 107.1, p < .001). Further post-hoc analysis using the Nemenyi test indicated significant differences among all three pairs of conditions: Action-based Undo vs. Object-based Undo (p < .001), Action-based Undo vs. No Undo (p < .001), and Object-based Undo vs. No Undo (p < .001). These findings demonstrate that the efficiency of undo operations varied significantly depending on the undo method employed.

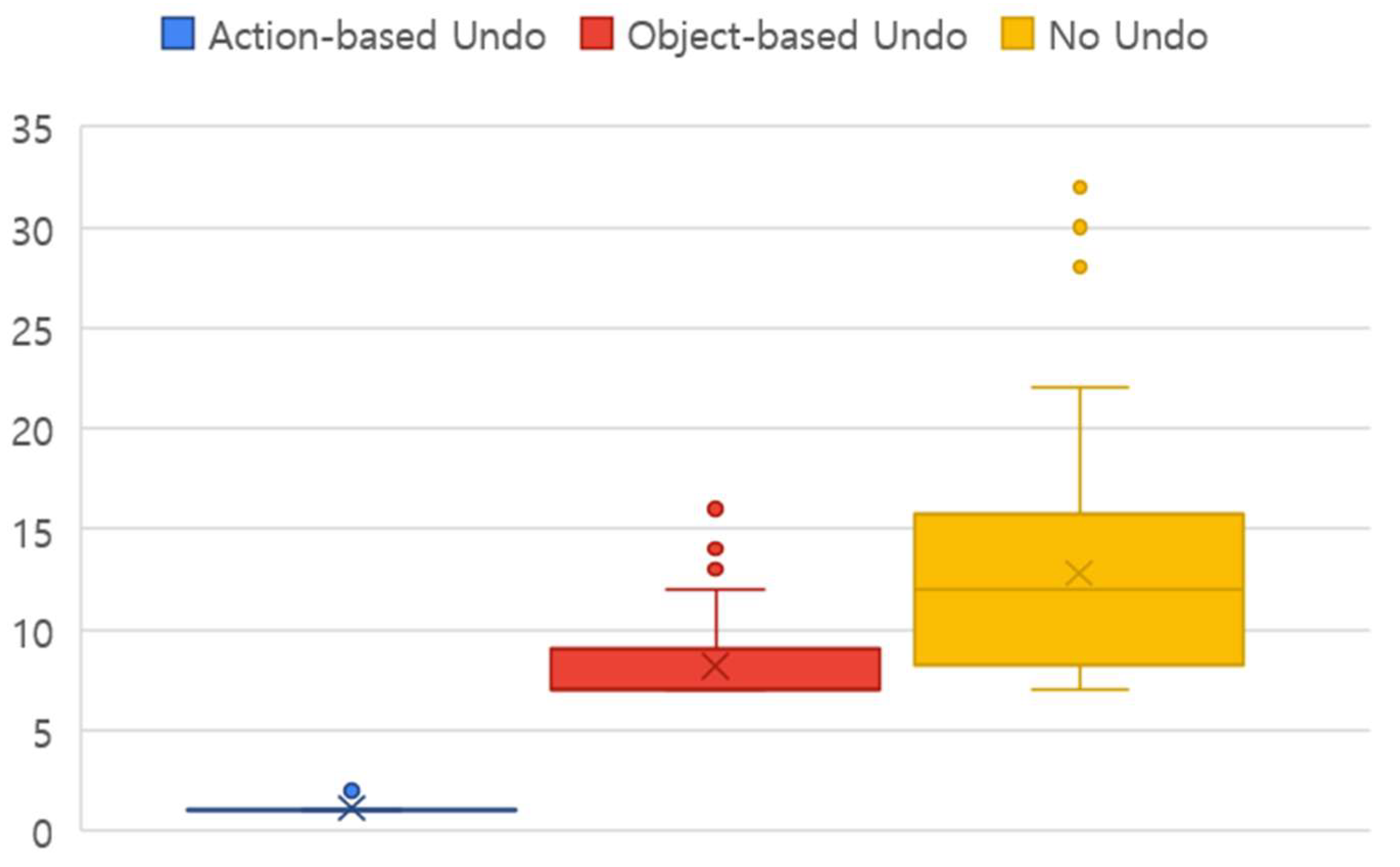

5.2. Number of Interactions

The number of interactions required for participants to restore the toppled dominoes to their original state was analyzed using the Friedman test. The results revealed significant differences among the three conditions ((2) = 125.8, p < .001). The mean and standard deviation of interactions for each condition were as follows: Action-based Undo (M = 1.13, SD = 0.348), Object-based Undo (M = 8.21, SD = 1.92), and No Undo (M = 12.8, SD = 5.44).

Figure 7.

Number of Interactions.

Figure 7.

Number of Interactions.

Additionally, a post-hoc analysis using the Nemenyi test indicated statistically significant differences between all three conditions: Action-based Undo vs. Object-based Undo (p < .001), Action-based Undo vs. No Undo (p < .001), and Object-based Undo vs. No Undo (p < .001). These results demonstrate that the Action-based Undo method required the fewest interactions to restore the dominoes, followed by the Object-based Undo method, while the No Undo condition required the highest number of interactions.

5.3. Subjective Data

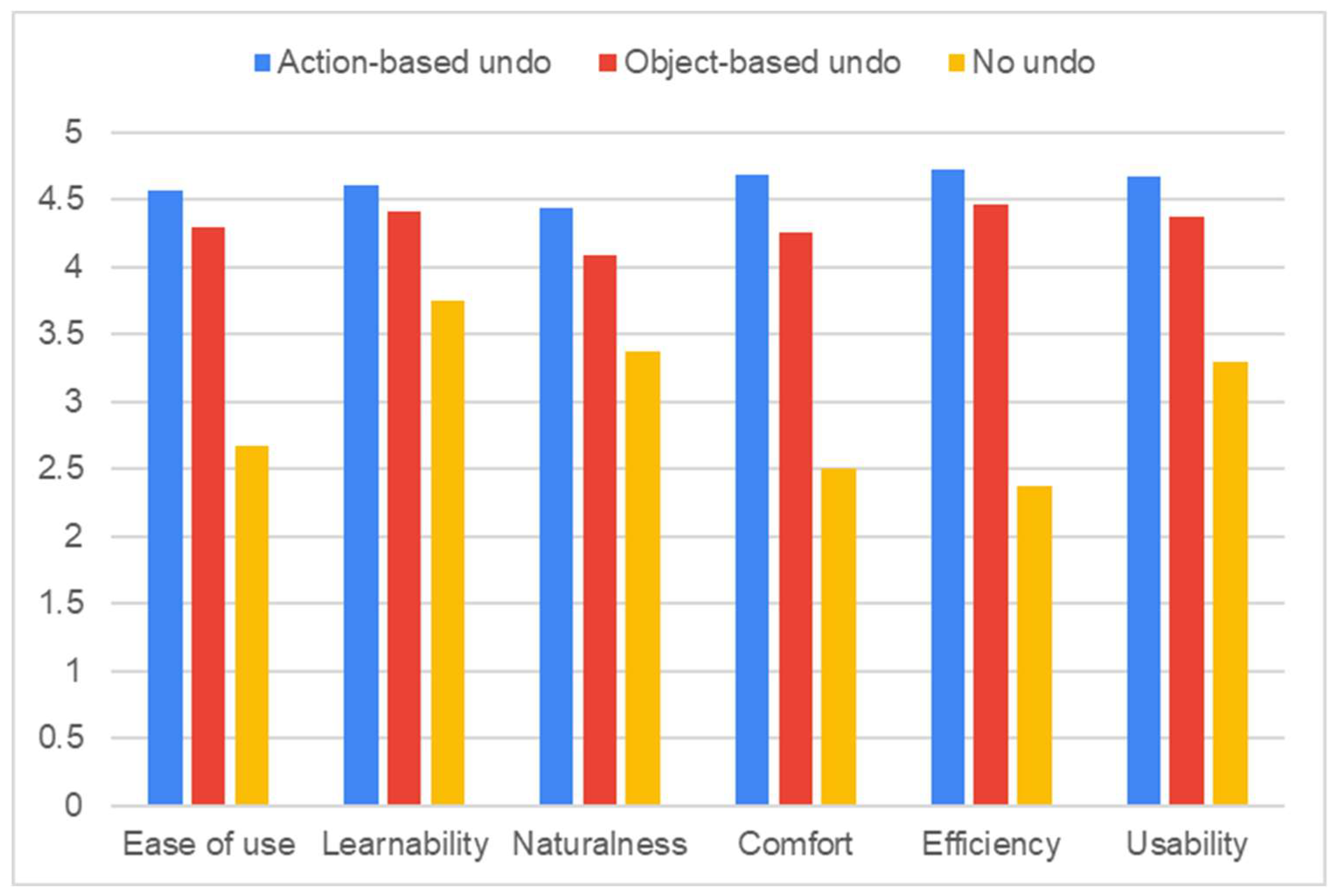

5.3.1. Modified SUS

5.3.1.1. Ease of Use

The Friedman test indicated a statistically significant difference among the three conditions (). The mean and standard deviation for each condition were as follows: Action-based Undo (M = 4.56, SD = 0.681), Object-based Undo (M = 4.29, SD = 0.69), and No Undo (M = 2.67, SD = 1.2). To further investigate pairwise differences, a post-hoc Nemenyi test was conducted. The results indicated statistically significant differences between Action-based Undo and Object-based Undo, as well as between Action-based Undo and No Undo (). However, no significant difference was observed between Object-based Undo and No Undo ().

Figure 8.

Average Scores of Modified System Usability Scale.

Figure 8.

Average Scores of Modified System Usability Scale.

5.3.1.2. Learnability

The Friedman test revealed a statistically significant difference among the conditions (). The mean and standard deviation for each condition were as follows: Action-based Undo (M = 4.60, SD = 0.818), Object-based Undo (M = 4.42, SD = 0.584), and No Undo (M = 3.75, SD = 1.29). To further analyze pairwise difference, a post-hoc Nemenyi test was performed. The results indicated a statistically significant difference between Action-based Undo and No Undo (). However, no significant differences were found between Action-based Undo and Object-based Undo, nor between Object-based Undo and No Undo ().

5.3.1.3. Naturalness

The Friedman test indicated a statistically significant difference among the conditions (). The mean and standard deviation for each condition were as follows: Action-based Undo (M = 4.44, SD = 0.741), Object-based Undo (M = 4.08, SD = 0.776), and No Undo (M = 3.38, SD = 1.31). To further investigate pairwise differences, a post-hoc Nemenyi test was conducted. The results show statistically significant differences between Action-based Undo and Object-based Undo, as well as between Action-based Undo and No Undo (). However, no significant difference was observed between Object-based Undo and No Undo ().

5.3.1.4. Comfort

The Friedman test showed a statistically significant difference among the conditions (). The mean and standard deviation for each condition were as follows: Action-based Undo (M = 4.69, SD = 0.512), Object-based Undo (M = 4.25, SD = 0.847), and No Undo (M = 2.5, SD = 1.21). To further investigate pairwise differences, a post-hoc Nemenyi test was conducted. The results indicated statistically significant differences between Action-based Undo and No Undo, as well as between Object-based Undo and No Undo (). However, no significant difference was observed between Action-based Undo and Object-based Undo ().

5.3.1.5. Efficiency

The Friedman test revealed a statistically significant difference among the conditions (). The mean and standard deviation for each condition were as follows: Action-based Undo (M = 4.73, SD = 0.449), Object-based Undo (M = 4.46, SD = 0.779), and No Undo (M = 2.38, SD = 0.97). To further investigate pairwise differences, a post-hoc Nemenyi test was conducted. The results indicated statistically significant differences between Action-based Undo and No Undo, as well as between Object-based Undo and No Undo (). However, no significant difference was observed between Action-based Undo and Object-based Undo ().

5.3.1.6. Usability

The Friedman test showed a statistically significant difference among the conditions (). The mean and standard deviation for each condition were as follows: Action-based Undo (M = 4.67, SD = 0.476), Object-based Undo (M = 4.38, SD = 0.647), and No Undo (M = 3.29, SD = 1.2). To further analyze pairwise differences, a post-hoc Nemenyi test was conducted. The results indicated statistically significant differences between Action-based Undo and No Undo, as well as between Object-based Undo and No Undo (). However, no significant difference was found between Action-based Undo and Object-based Undo ().

5.3.2. Custom Questionnaire

The results of the Custom Questionnaire indicated that, exception for the Clarity item, Action-based Undo outperformed Object-based Undo across all other evaluated aspects. Furthermore, No-undo was not identified as the most appropriate undo method for any of assessed criteria. When participants were asked to justify their selection in the "Best undo" category, those who preferred Action-based Undo provided the following rationales: "It closely resembles commonly used undo method," "It enables multiple actions to be undone simultaneously, saving time," "It is simple to operate," and "It is intuitive and convenient, as the undo point is clearly identifiable." Conversely, participants who favored Object-based Undo cited the following justifications: "It is beneficial for performing precise tasks," "It allows undoing actions to a specific, desired state," and "It enables step-by-step undo functionality."

Figure 9.

Custom Questionnaire.

Figure 9.

Custom Questionnaire.

6. Discussion

6.1. Efficiency

The analysis of undo time confirmed that using a 3D undo system enables users to recover to a desired previous state more quickly than performing a task without an undo function. Among the methods evaluated, Action-based Undo allowed users to revert to their previous state with the shortest time and the fewest interactions. While Object-based Undo enabled faster task completion compared to the No Undo condition, its undo time was 3.34 times longer than that of Action-based Undo. This disparity can be attributed to an inherent characteristics of 3D virtual environments, namely the chain reactions caused by various external forces.

Additionally, the number of interactions required for task completion was significantly higher for No Undo, with 11.3 times more compared to Action-based Undo. For Object-based Undo, 7.2 time more history manipulations were needed to revert all the domino blocks to their previous state than in the Action-based Undo. In realistic 3D virtual environments, the chain reactions inherently make it challenging for users to deliberately stop or control unintended actions. When unintended actions disrupt task progression, users must choose between two recovery strategies:

Start over: Restart the task from the current state to achieve the intended goal

Return to a previous state and re-execute action: Undo actions to revert to a desired previous state and resume task execution.

The first approach (start over) was simulated under the No Undo condition and was found to be significantly more time consuming than the second approach (returning to a previous state and re-execute actions). This finding suggests that returning to a previous state is more efficient strategy for achieve their desired world state.

Notably, Action-based Undo provides an action dependency mechanism, allowing multiple actions to be undone with a single undo command. This capability significantly enhances efficiency compared to Object-based Undo, which undoes only one action per command. As a result, Action-based Undo enables faster recovery to previous states, minimizing task completion time and user effort.

These findings demonstrate that Action-based Undo effectively improves user performance within 3D virtual environments by offering superior efficiency and reducing the time and effort required for interaction recovery.

6.2. Usability

The analysis of usability revealed that Action-based Undo demonstrated more positive outcomes compared to other conditions. This was verified through both the Modified System Usability Scale (Modified SUS) and the Custom Questionnaire. The Modified SUS applied in this study consisted of 12 questions, where positive and negative statements are alternated for each of six categories (Ease of use, Learnability, Naturalness, Comfort, Efficiency, Usability).

From the perspective of Ease of use, the Action-based Undo received the highest score, followed by Object-based Undo, with No Undo scoring the lowest score. This result highlights the advantage of the Action-based Undo system, which allows users to simultaneously revert multiple objects to their previous states through action dependency management. The higher score of Object-based Undo compared to No Undo can be attributed to the challenges participants faced when manipulating objects without an undo functionality during task completion.

Regarding Learnability, a significant difference was observed only between Action-based Undo and No Undo. However, due to the shared concept of 3D undo, no statistically significant difference was found between Action-based Undo and Object-based Undo. Additionally, since Object-based Undo operates similarly to the traditional 2D undo system by reverting a single action on a single object with each undo command, the required learning effort was relatively low. As a result, there was no significant difference between Object-based Undo and No Undo in terms of learnability.

In terms of Naturalness, the Action-based Undo method scored significantly higher than both Object-based Undo and No Undo. Participants found it natural that dependent actions triggered by a single intended action could be reverted with a single undo command in the Action-based Undo system. In contrast, Object-based Undo was perceived as less natural because when a single intended action triggered a chain of dependent events, participants had to press undo multiple times to fully revert to the desired previous state. Although No Undo represents the most realistic condition, it received the lowest score due to the experimental setting being a 3D virtual environment. Participants, who subconsciously expected undo functionality in a PC-connected virtual space, perceived the absence of such functionality as unnatural.

Comfort, which measured the perceived ease of use, Efficiency, which assessed the extent to which the undo function facilitated task completion, and Usability, which evaluated the smoothness of the user experience, all showed statistically significant differences between Action-based Undo and No Undo, as well as between Object-based Undo and No Undo. However, no significant difference was observed between Action-based Undo and Object-based Undo in any of these aspects. Participants reported that the presence of a 3D undo function made working in the virtual environment more comfortable than No Undo condition, but the type of 3D undo did not have a significant impact on Comfort, Efficiency, or Usability.

Ultimately, while Action-based Undo recorded the highest mean score across all categories, statistically significant differences compared to the other two undo methods were observed only in Ease of use and Naturalness. In the remaining four categories, although Action-based Undo scored higher than No Undo, no significant differences were found when compared to Object-based Undo.

To further evaluate the appropriateness of each undo method, the Custom Questionnaire was conducted. None of the participants selected No Undo as their preferred choice for any question, and all participants indicated that the availability of a 3D undo system improved task completion. For all questions except Question 4, Action-based Undo was the preferred choice. Most participants rated Action-based Undo as easier to use, faster, more accurate, and more user-friendly compared to Object-based Undo.

An exception was found in Question 4 ("Which of the three provided undo methods made it most clear what you were undoing?"), where Object-based Undo received slightly higher scores. This outcome was attributed to its design, which undoes one action per undo command, allowing participants to clearly identify the specific action being reverted through the use of guide objects. In contrast, Action-based Undo reverses multiple interdependent actions simultaneously, which some participants found less transparent. However, participants who preferred Action-based Undo noted that its action dependency feature, which groups related actions into a single undo command, enhanced their understanding the overall undo flow.

For Question 8 ("Which of the three provided undo methods was the best for undoing a task, and why?"), Action-based Undo was the most frequently selected. However, a notable number of participants also preferred Object-based Undo. Participants who chose Action-based Undo prioritized efficiency, while those who chose Object-based Undo valued the clarity it provided. The inability of Action-based Undo to reverse individual dependent actions was identified as a limitation, making it less appealing to some users. Additionally, participants familiar with traditional 2D undo systems found Object-based Undo more intuitive and familiar, leading to more favorable evaluations.

These findings confirm that 3D undo systems improve both user performance and user experience in 3D virtual environments. While Action-based Undo demonstrates advantages in efficiency and usability, Object-based Undo provides the benefit of clearly identifying the target of undo operations.

7. Limitations and Future Work

7.1. Guide Object in Object-Based Undo

In a physics-based 3D virtual environment, where a single interaction can trigger a series of cascading actions, we conducted an experiment comparing three different undo methods. In the Object-based Undo method, where only a single object is reverted per undo command, a translucent guide object was introduced to distinguish the actual object from the target of the undo operation. This guide object was implemented to aid participants in effectively performing tasks by clearly indicating the undo target during the history manipulation phase. However, this additional feature influenced responses to Question 8 of the custom questionnaire, which asked: “Which of the three provided undo methods do you think is the most effective for reverting actions, and why?”

Among the 24 participants, five explicitly mentioned the guide object in their responses. Of these, two participants selected Object-based Undo, stating that the guide object helped them clearly identify the intended undo point. Conversely, three participants chose Action-based Undo, reporting that the guide object caused confusion in determining the exact undo target. These results indicate that the responses were significantly influenced not solely by the usability of 3D undo methods themselves but also by the presence of the guide object as an auxiliary feature. Therefore, further research is required to investigate the impact of such auxiliary features on user experience in 3D undo systems.

7.2. Experimental Scenario

The effectiveness of the undo function becomes evident in situations where undo operations are required, particularly when error recovery is needed. According to the pre-experiment questionnaire, all participants were VR novices with fewer than five prior experiences using VR equipment. As a result, errors frequently occurred during the experiment, leading to a proportional increase in the demand for undo functionality. However, due to substantial individual differences in participants’ task performance ability, evaluating the effectiveness of undo functionality solely based on total task completion time proved to be challenging. To address this issue, the experiment was designed in a way that eliminates variability in individual task performance, allowing for a more controlled assessment of 3D undo effectiveness under consistent conditions. For future research, it is essential to design scenarios where undo operations are naturally required, enabling a more in-depth evaluation of the scalability and generalizability of 3D undo functionality.

8. Conclusion

This study explored the efficiency and usability of 3D undo methods in a physics-based three-dimensional virtual environment during object manipulation tasks. Using a domino setup within a 3D space, the study compared two self-developed 3D undo methods, Action-based Undo and Object-based Undo, against a No Undo condition as a control. The comparison focused on undo time and user experience across the three conditions. The results indicated that the presence of a 3D undo function significantly improved both efficiency and usability. In terms of user performance, which considered the time required to revert to a previous state and the number of commands used during history manipulation, the Action-based Undo method allowed users to return to the previous state in the shortest time with the fewest commands. From a usability perspective, both Action-based Undo and Object-based Undo received positive feedback from users when compared to the No Undo condition. The proposed 3D undo mechanism offers an effective solution for enhancing user experience in environments where frequent multi-object interactions occur. These research findings will contribute to the design of more intuitive and effective 3D interaction systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jung-Min Park; Data curation, Sang Yup Han; Formal analysis, Sang Yup Han and Jung-Min Park; Funding acquisition, Jung-Min Park; Investigation, Sang Yup Han; Methodology, Sang Yup Han; Project administration, Jung-Min Park; Resources, Jung-Min Park; Software, Sang Yup Han; Supervision, Jung-Min Park; Validation, Sang Yup Han and Jung-Min Park; Writing – original draft, Sang Yup Han and Jung-Min Park; Writing – review & editing, Sang Yup Han and Jung-Min Park.

Funding

This research was funded by the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) Institutional Program (Project No. 2E33602) and by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) (2022M3C1A309874611)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cucinella, S.L.; de Winter, J.C.F.; Grauwmeijer, J.; Evers, M.; Marchal-Crespo, L. Towards personalized immersive virtual reality neurorehabilitation: a human-centered design. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, Volume 22, No 7, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Conrad, M.; Kablitz, D.; Schumann, S. Learning effectiveness of immersive virtual reality in education and training: A systematic review of findings. Computers & Education: X Reality, Volume 4, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Miguel-Alonso I.; Checa D.; Guillen-Sanz H.; Bustillo A. Evaluation of the novelty effect in immersive Virtual Reality learning experiences, Virtual Reality, Volume 28, Issue 1, 27 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Joshi, S.; Wang, H.; Young, C.; Pervez, A.; Qu, Y.; Washburn, S. Using immersive virtual reality technology to enhance nursing education: A comparative pilot study to understand efficacy and effectiveness. Applied Ergonomics, Volume 115, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, S.; Wang, L. The Development of Virtual Reality Technology and the Origin of the Metaverse. SIDICDT 2022, Volume 53, pp. 627-630. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, C. Verification of the possibility and effectiveness of experiential learning using HMD-based immersive VR technologies. Virtual Reality 2019, Volume 23, pp. 101-118. [CrossRef]

- Höll, M.; Oberweger, M; Arth, C.; Lepetit, V. Efficient Physics-Based Implementation for Realistic Hand-Object Interaction in Virtual Reality. In Proceeding of 2018 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interface, pp.175-182, 2018.

- Shneiderman, B.; Plaisant, C. Designing the User Interface: Strategies for Effective Human-Computer Interaction, 4th ed.; Pearson Addison Wesley: Boston, US, 2004; pp. 241-246.

- Archer, J.E.; Conway, R.; Schneider, F.B. User Recovery and Reversal in Interactive Systems. ACM Transactions on Programming Language and Systems, 6, pp. 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Teitelman, W. Automated programmering—The programmer’s assistant. AFIPS '72 (Fall, part II): Proceedings of the December 5-7, 1972, fall joint computer conference, part II, pp. 917-921.

- Jenson, S.Q.; Fender, A.; Müller, J. Inpher: Inferring Physical Properties of Virtual Objects from Mid-Air Interaction. In Proceeding of the 2018 CHI on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, Canada, 530, pp. 1-5.

- McNeill, M.D.J.; Sayers, H.; Wilson, S.; Mc Kevitt, P. A Spoken Dialogue System for Navigation in Non-Immersive Virtual Environment. Computer Graphics Forum, Volume 21, pp. 713-722. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Imamiya, A. Object-based Linear Undo model. Object-based Linear Undo model. In: Howard, S., Hammond, J., Lindgaard, G. (eds) Human-Computer Interaction INTERACT ’97. IFIP — The International Federation for Information Processing. Springer, Boston, MA, Boston, MA. [CrossRef]

- Müller, F.; Ye, A.; Schön, D.; Rasch, J. UndoPort: Exploring the Influence of Undo-Actions for Locomotion in Virtual Reality on the Efficiency, Spatial Understanding and User Experience. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 234, pp. 1-15.

- Rasch, J.; Perzl, F.; Weiss, Y.; Müller, F. Just Undo It: Exploring Undo Mechanics in Multi-User Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, USA, 952, pp. 1-14.

- Kim, M.G.; Lee, J.J.; Park, J.M. Designing a History Tool for a 3D Virtual Environment System. In Proceedings of the 2019 HCI International Conference, Volume 1033, pp. 398-405.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).