3.2.2. Impact on Logistics-Production Potential

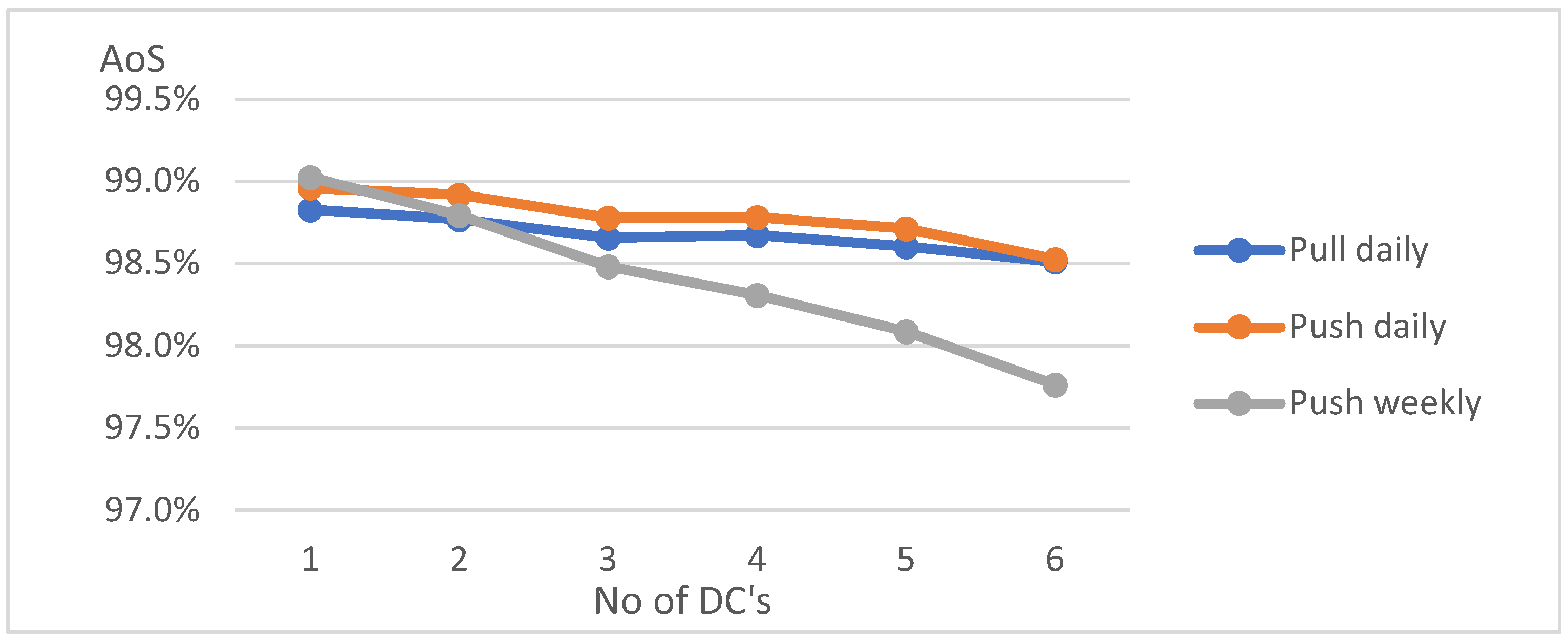

The first parameter and effect of using these strategies was the level of stock availability in warehouses, which can be a measure of logistical customer service. The simulation results are presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

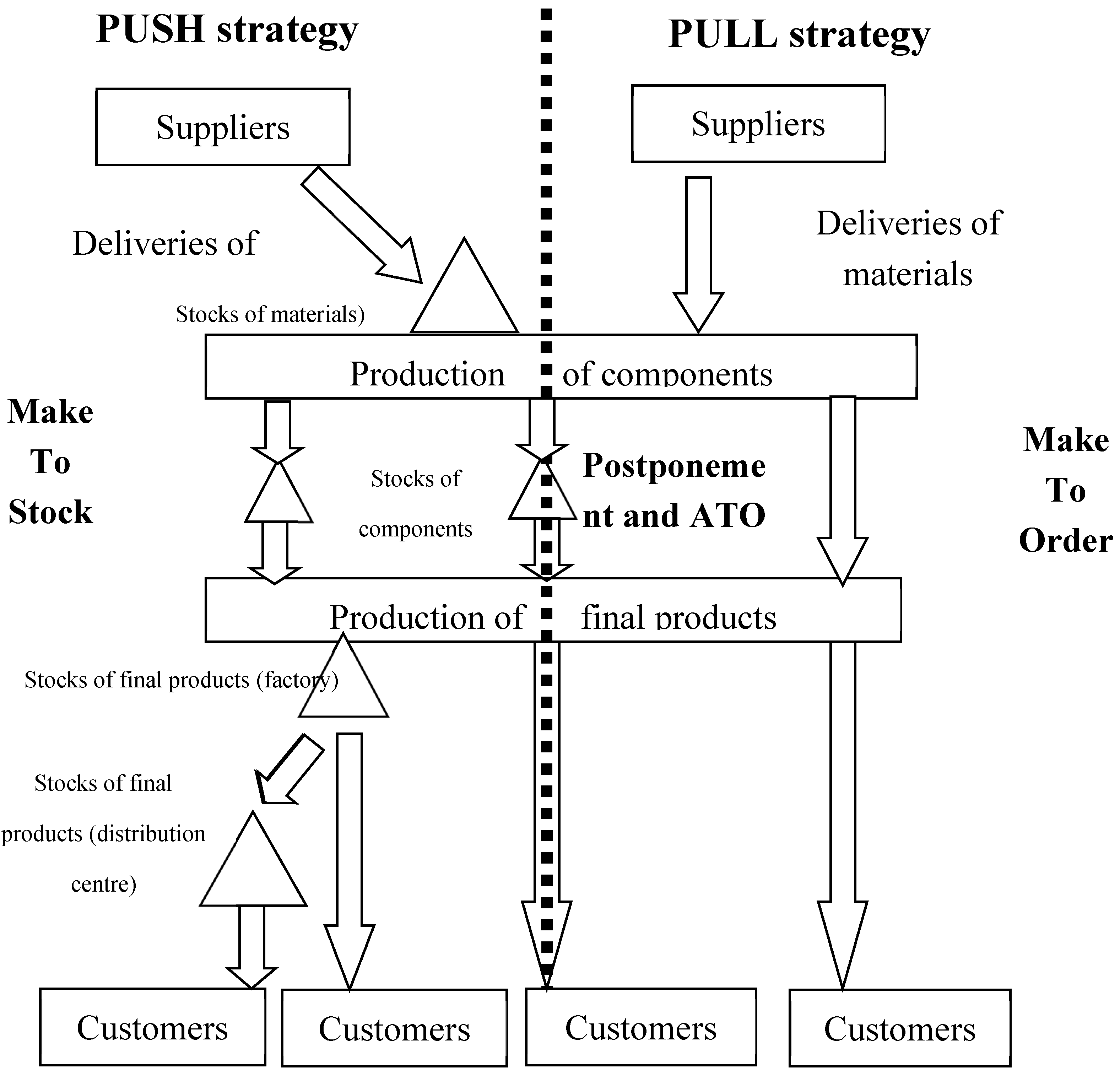

CD’s are replenished in 3 ways:

“Pull daily” in quantities to meet actual demand;

“Push daily” also in small but fixed amounts according to forecasts of demand;

“Push weekly” in fixed amounts corresponding to the average weekly demand.

This third option applies when e.g. rail transport is used, which is less flexible than road transport, and deliveries are made on schedule.

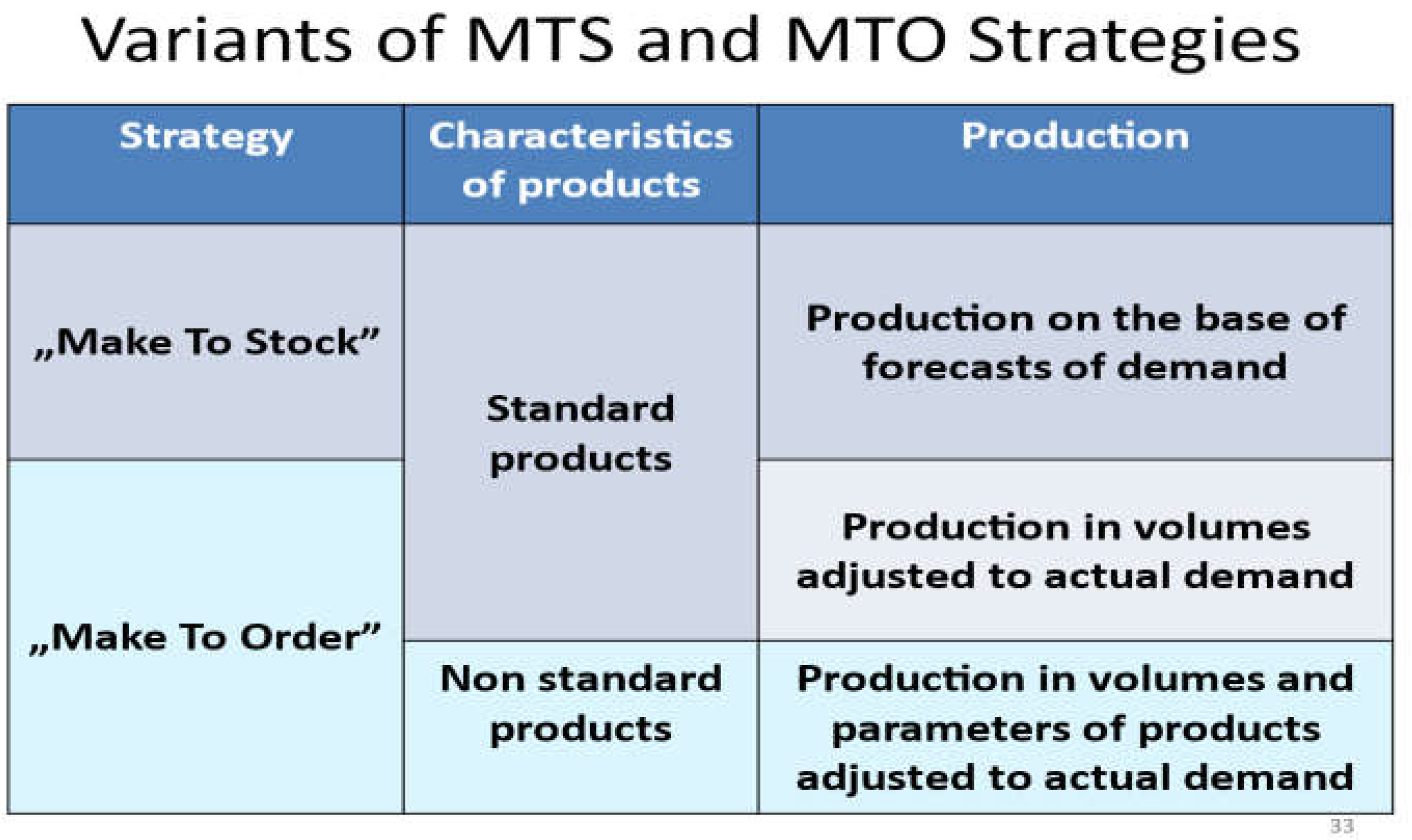

In the first step, simulations were carried out for a Gaussian distribution and standard deviations of 5% and 30% from the average demand.

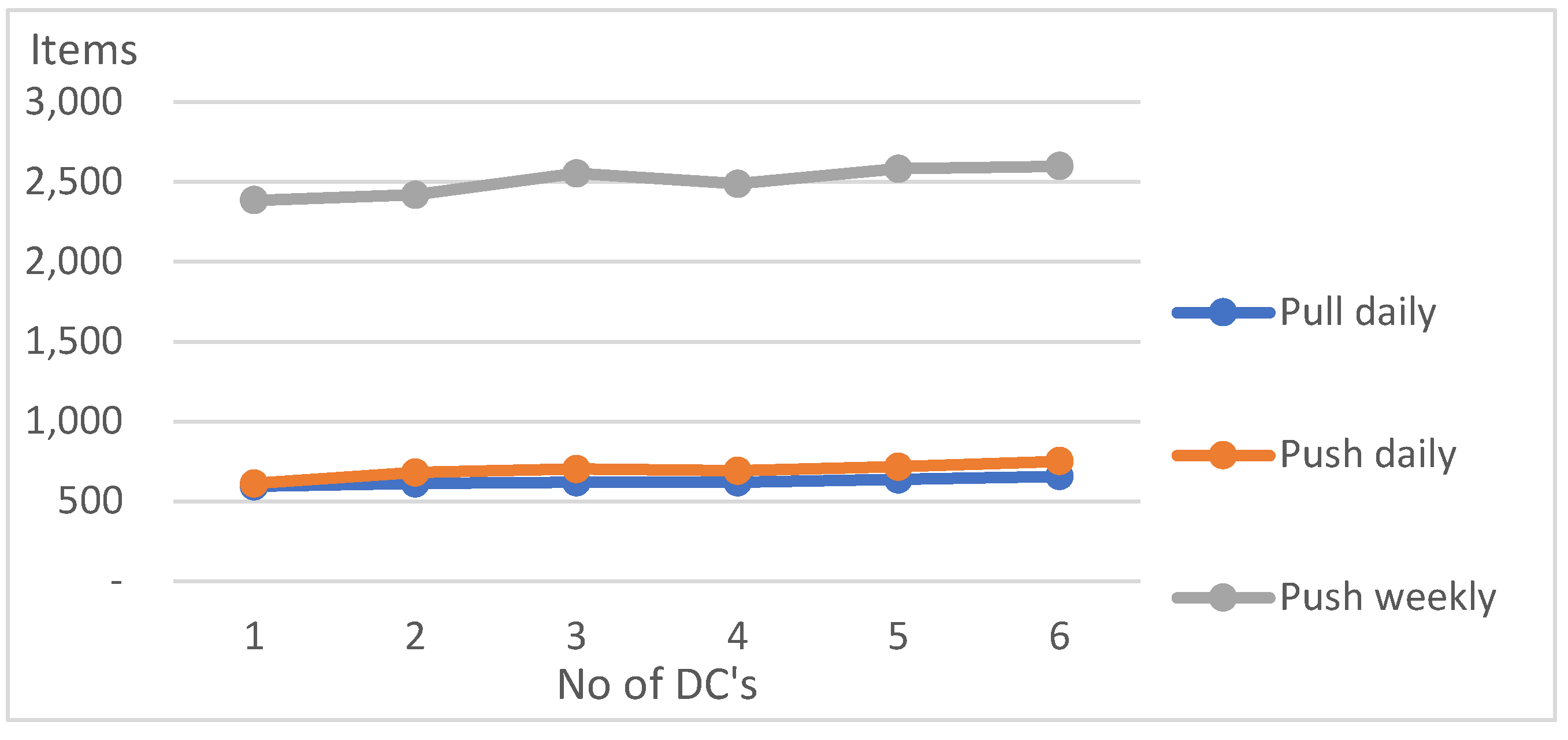

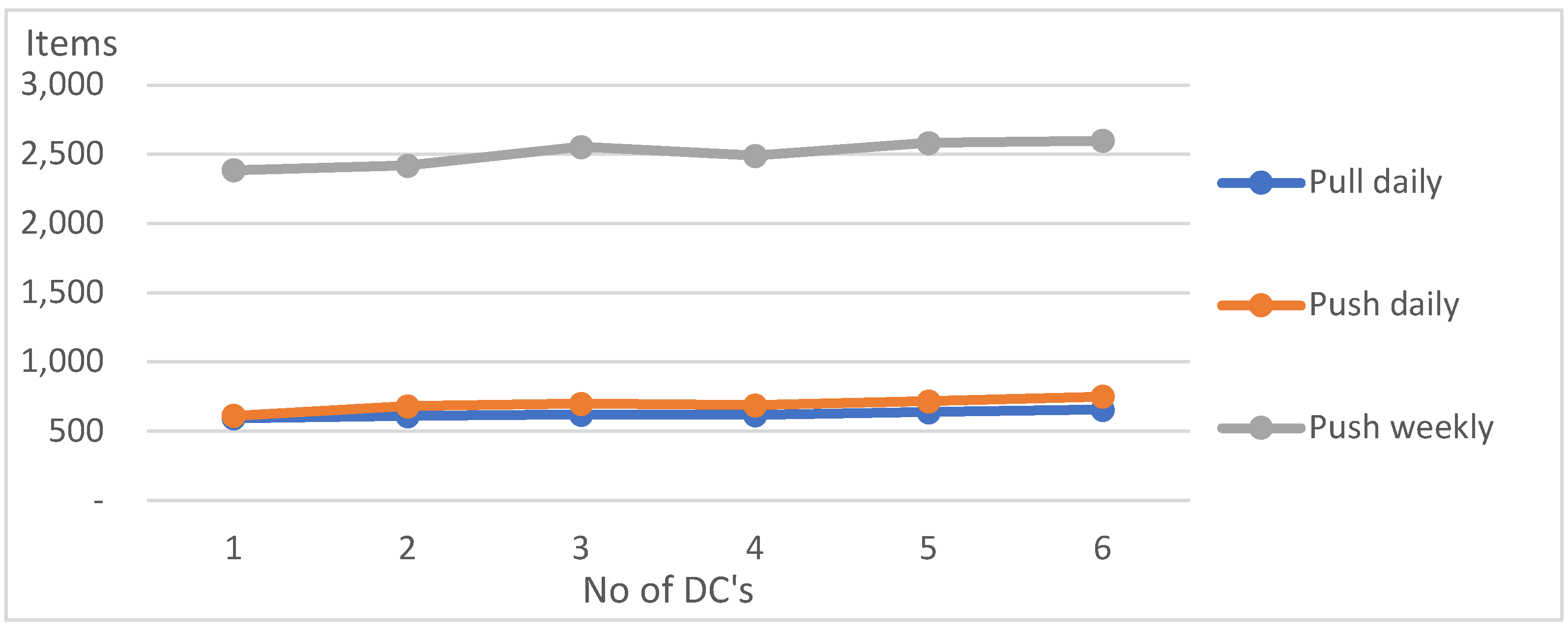

For small fluctuations in sales (5% of Standard deviation of average sales) deliveries in large quantities (“Push weekly”) are the most effective in this regard. A high level of customer service is also ensured by “pushing” goods daily from the plant to the warehouses. As the number of warehouses increases, the level of customer service drops very sharply in weekly deliveries, while in the “Push daily” remain high.

Daily “pulled” deliveries result in a lower level of customer service. Only with 6 distribution centers they offer a higher level of service than weekly “Push” deliveries. However, in most cases, the best customer service is associated with “Pushing” deliveries in small quantities (daily).

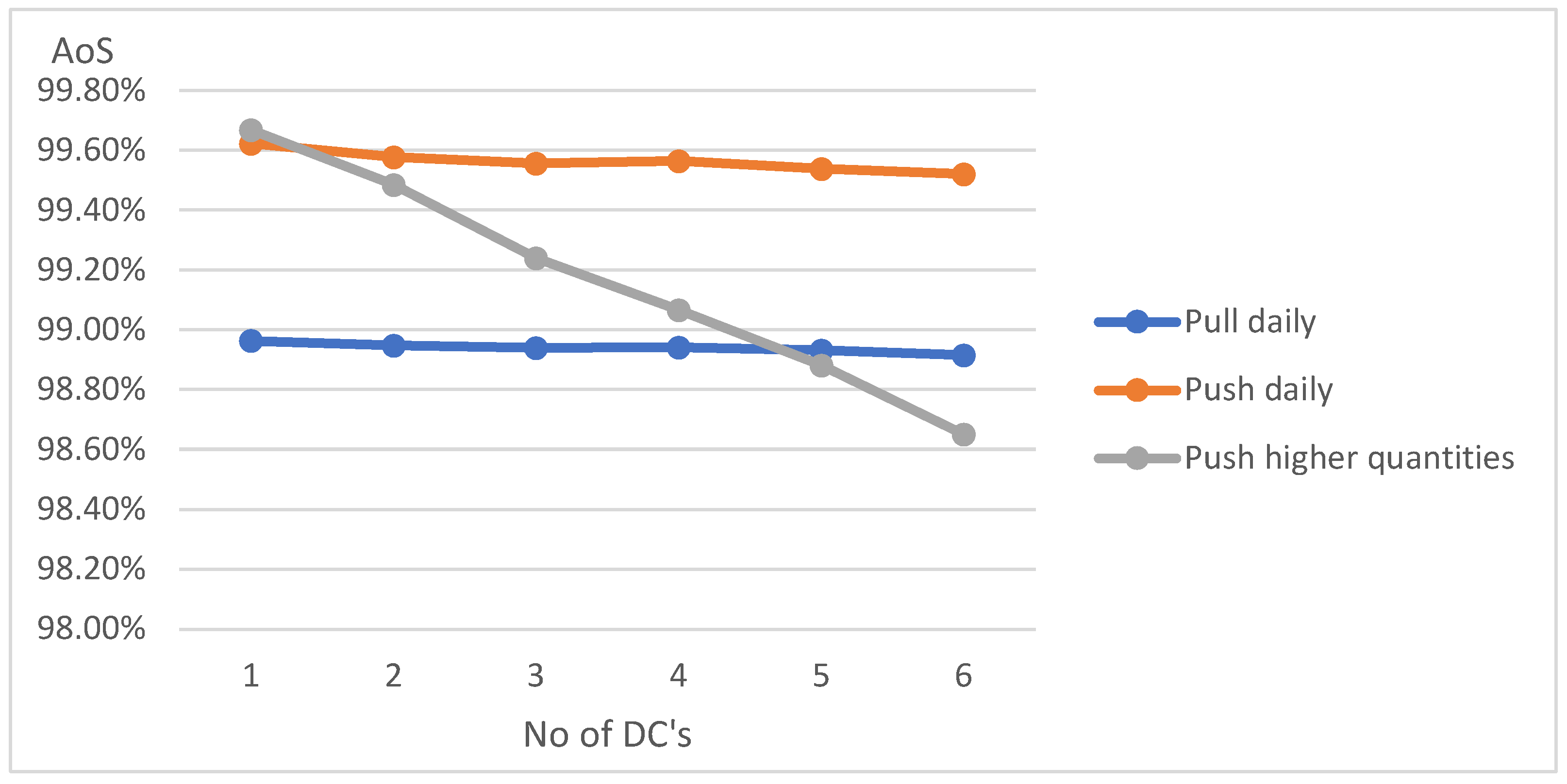

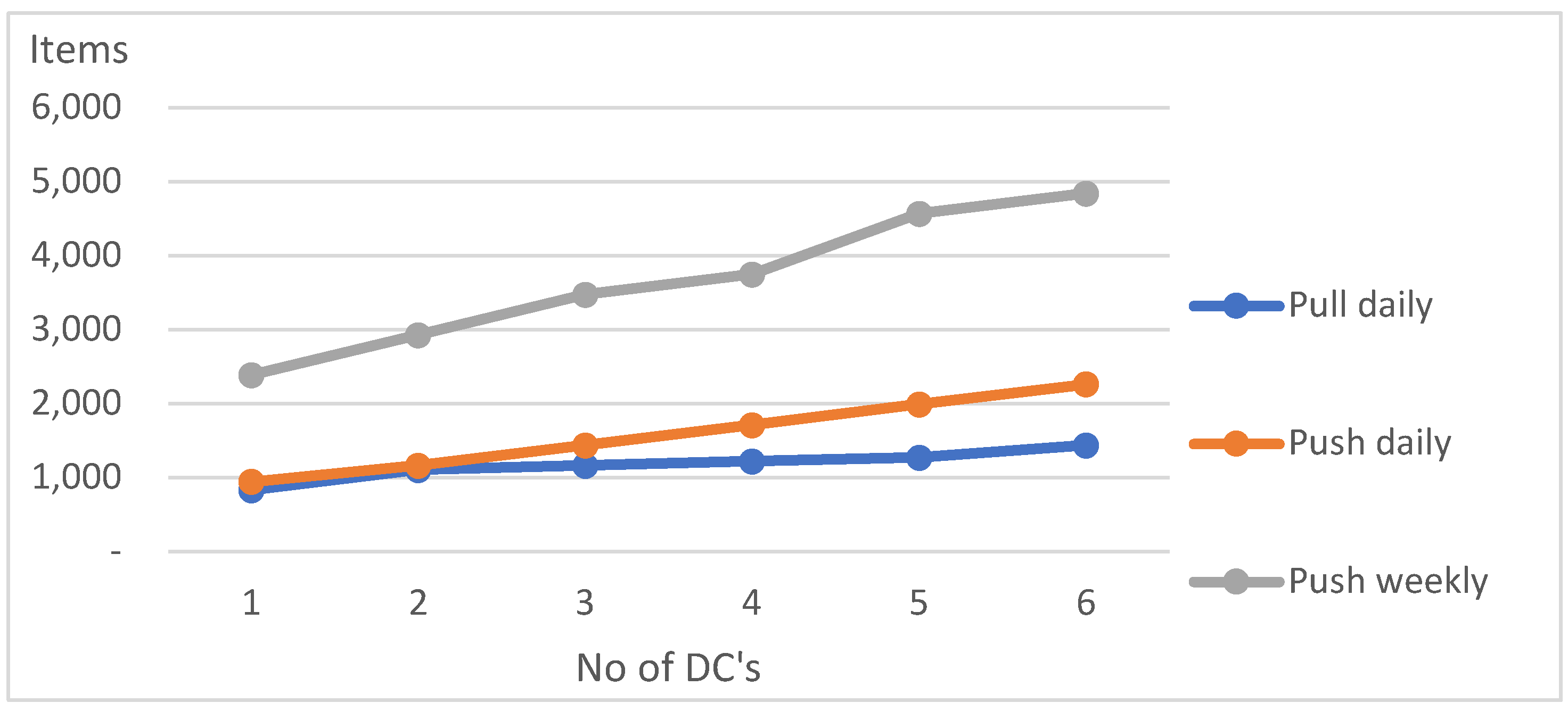

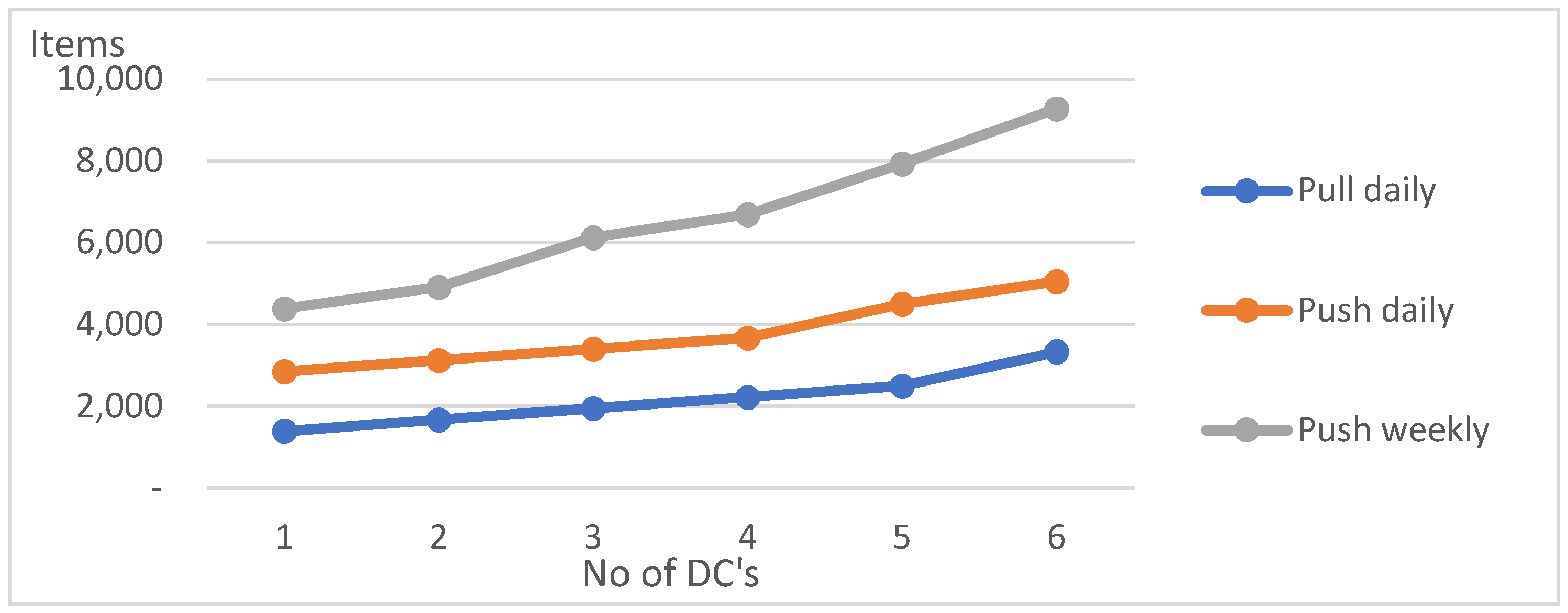

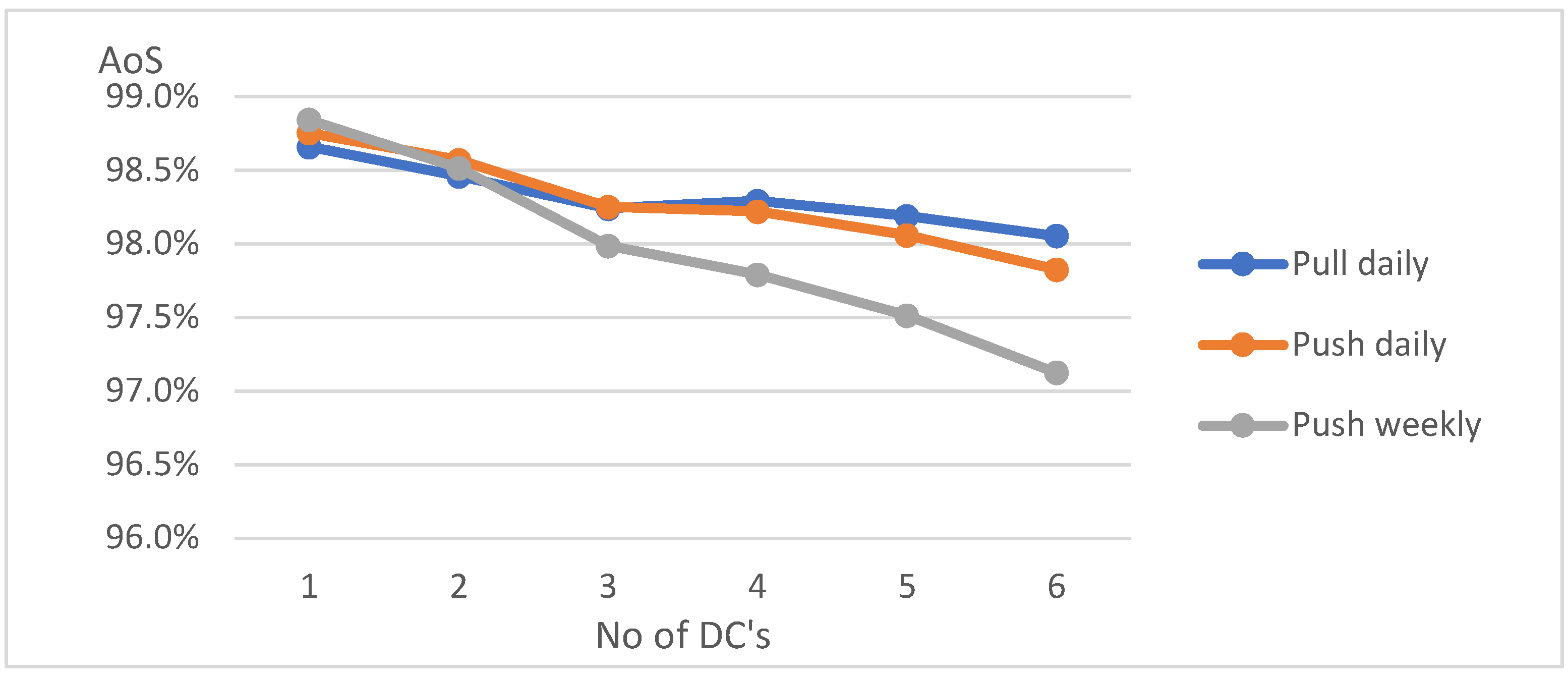

The situation changes when demand is more volatile (standard deviation of 30% of average demand) - in all strategies and variants, the level of customer service measured by inventory availability is lower, but to varying degrees.

Regardless of the number of CD’s in the distribution network, the best inventory availability is again observed for daily “Push” deliveries (

Figure 4). This time yet a slightly lower, but also high level of service is observed for daily “Pull” deliveries. In the case of weekly “Push” deliveries, the level of service is much lower. The results of these simulations are not surprising - as expected with greater fluctuations of demand and therefore less predictability of demand, a more flexible system that adjusts the volume of deliveries to actual rather than forecast demand is more efficient from a customer service perspective.

The differences between the levels of logistics service appear to be small. But first, they are due to the probability distributions assumed in the simulations and the data generated by the model developed by the author. Since lower levels of service are observed in practice, there is a need to investigate what the actual probability distributions and sales fluctuations of companies are. The model does not take into account one more service level factor - on-time delivery. This is because it assumes that deliveries arrive on time. Taking into account the delays in deliveries to warehouses would result in either lower service levels or increased inventories.

However, even without considering the above factors, even a small change in the level of logistical customer service can have a big impact on the efficiency of the system. As demonstrated later in the article, deterioration of service by even a few percent can result in high costs of lost sales. Increasing that service by just a few percent as well can also result in a significant increase in costs - for example, inventory maintenance and warehousing.

Table 2 and

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 presents results of the simulation of the impact of different strategies at the level of stocks for the levels of service from

Table 1.

It is, of course, no surprise that inventory levels increase if there is a shift from a “Pull daily” strategy, which is the most flexible, to a “Push daily” strategy. The largest is in “Push weekly” due to larger sizes of deliveries to warehouses. In all strategies, inventories increase if sales fluctuations increase from 5% to 30%. In all strategies, too, inventory levels increase as the number of warehouses increases, which confirms (and explains) the existence of the benefits of the strategy of “centralization of stocks” - better customer service can be achieved with less inventory.

To ensure comparability - calculations were made also for the situation when the level of service in all variants is 100%, what is presented in

Table 3 and

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

In all variants there were large increases in stocks - even in the first variant - “Pull daily”/1 DC/5% standard deviation. This confirms the relationship known from the logistics literature between service level, sales and costs, that when the service level is already very high, increasing it even by a small percentage requires a large increase in costs.

The differences are larger in the case of “Pull daily” but smaller in the case of “Push weekly, ” which can be explained by the fact that deliveries in larger quantities already result in high inventory levels. The differences increase as the number of warehouses increases, once again showing the benefits of centralizing warehousing and confirming the need to combine these two decision problems. In all variants, increasing the number of warehoues results in a very high increase in inventory levels. This increase is even greater if sales fluctuations are greater.

The purpose of the next simulation was to examine how these strategies affect the amount of production capacity required in the case that customer demand is to be satisfied in 100%. The impact here is weaker than in the case of inventory (

Table 4). However, given that the cost of maintaining production potential may be greater than maintaining inventory, there is a need to take this relationship into account as well.

One can see a regularity - the highest required production potential occurs in the “Pull - daily” strategy, and the lowest when products are “pushed out” in weekly volumes. This also seems easy to interpret - “Pull” requires either a flexible production system or a high potential for the system to adapt to changing needs. Schedule deliveries, on the other hand, promote production stability.

If demand has a Gamma distribution, service levels are slightly lower than in the case of Gauss distribution (

Table 5 and

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). The difference, however, is which strategy is more efficient. In the case of Gamma, in almost all cases the level of service is better with daily deliveries than with weekly deliveries. In the strategy “Push Weekly ”, the level of service is slightly better with a single warehouse. However, it decreases to a large extent with more warehouses. Thus, with weekly deliveries to 1 warehouse and a standard deviation of 3%, the inventory availability level was 99.0%. When deliveries were made to 6 DC’s the service level dropped to 97.8%. The situation was similar when the standard deviation was 6%.

Service levels for both Pull and Push daily deliveries also decrease as the number of warehouses increases, but to a much lesser extent than for weekly deliveries.

However, despite not much difference in service levels, the impact of these strategies on stocks is greater. In all cases, stock levels are significantly higher for Gamma than Gauss distributions (

Table 6) and in most cases, these differences increase with the number of warehouses. For example, with small standard deviations of demand and 1 warehouse, the inventory level is 126.85% higher in the case of a Gamma distribution than in the case of a Gaussian distribution. If the goods are distributed over a network of 6 warehouses, this difference is even greater, at 155.27%. Stocks in the other variants are also significantly higher than under the Gamma distribution. Interestingly, however, these differences would also be very large if customer orders were fully (100%) satisfied. However, in the case of “Pull daily”, inventory levels are very similar (

Table 7). This leads to the conclusion that the quick response strategy allows for a high level of customer service without building up high inventory levels.

The effect of distribution strategy on production potential for Gamma distribution was also analyzed. The results are similar - first, for each strategy, the amount of required potential is the same for each size of distribution network (number of DC’s). Second, the largest production potential is required with the Pull strategy. Thirdly, it is larger with larger sales fluctuations (

Table 8). However, in the case of a Gamma distribution - it is more than 30% larger than in the case of a Gaussian distribution.

The simulation results prove that decisions on the choice of replenishment strategy and the size of the warehouse network should be considered together. However, this is obviously not enough to assess the economic effectiveness of a given strategy, as the impact on costs and sales would have to be taken into account.

3.2.3. Economic efficiency of Pull and Push systems

Based on the results obtained from the above simulations, calculations of the economic efficiency of each strategy can be conducted.

The assumptions (data) are shown in

Table 9. When calculating the costs, the author of the article tried to make the best use of data on processes and the costs of these processes that occur in economic practice - e.g. in Poland.

The calculation results for the Gaussian distribution are shown in

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Table 12 . They take into account the parameters of shipments and the value of goods and the resulting costs of transportation, inventory maintenance and storage, and the cost of lost sales. Differences in total costs depend on the delivery strategy used but also on the type of product, because size and tonnage impact costs of warehousing and transportation.

The criterion for evaluating the effectiveness of the system is the “Total Cost, ” which includes the costs of inventory and storage, transportation and the costs of “lost sales”.

The costs of lost sales are derived from the level of inventory availability from previous simulations (

Table 1). Thus, if the logistical customer service measured by such a parameter is 98.96% for the “Pull daily”/1 DC variant. i.e. the company loses 1.04%. The costs of lost sales are calculating in following way for “Food”:

No of items x Price of a commodity x 1.04%=

32000000 [pcs./year] x 1 [EUR/item] x.04%= 332 EUR/year

which is 11.23% of the “Total Cost” (

Table 10).

For this group of products, the share of these costs increases with the number of warehouses in the distribution network and is obviously higher with larger sales fluctuations. As expected, these costs will be higher for more expensive products (

Table 12). Which provides justification for including them in cost calculations.

For “Food” (the cheapest) and 5% standard deviation, the lowest Total Costs occurs with regular (“Push every week”) deliveries to 6 warehouses by rail transport. If sales fluctuations were higher (30%) then deliveries to 6 warehouses would also be the most efficient, but with the more flexible “Pull daily” delivery system.

Since the value of the goods and the parameters of the shipments are important factors of costs, it can be expected that for more expensive goods (“Electronics”), deliveries with a higher degree of flexibility will be most effective. And this is indeed the case: with small fluctuations in sales (5%), a system of 6 warehouses is also optimal, yet not the cheapest rail transport every week should be used, but by daily deliveries with road transport, although still in the “Push” system. With larger fluctuations in sales (30%) a centralized system is more profitable. This is also the case of “Clothing”.

For similar delivery parameters in the case of Gamma distribution, costs are higher because there is a higher level of inventory and cost of lost sales are higher. For the first variant - deliveries to 1 warehouse every day in the “Pull” total costs increase as the value of goods supplied increases.

Since, as the cases of companies that have centralized their distribution systems show, centralization is effective in the case of large fluctuations in sales, this strategy should be more favorable precisely in the distribution of Gamma demand and more expensive goods. And so it is: only in the case of cheap “Food” is the network of 6 warehouses still the cheapest.

The simulation results presented here prove the truth of the thesis that these two decision problems - the choice of distribution strategy - Pull or Push, and the choice of the degree of centralization of the distribution network are not two separate decision problems, but should be considered together.

A very important conclusion is that the choice of the optimal strategy has a significant impact on the financial results of companies. In all product cases, in all demand variants and replenishment strategies, the share of the costs calculated here represents a few percent of the revenue value. As expected, the lowest share was found for the cheapest goods (“Food”), and the highest share for the most expensive goods. In all cases, the share increased with the fluctuation of demand. For example: in the case of “Food”, the share of these costs for 1 warehouse supplied with the “Pull daily” strategy and a standard deviation of demand of 5% is 9.23%. If the distribution network is expanded to 6 warehouses, this share drops to 5.72%. However, if demand fluctuations are greater (30%), the share of these costs increases to 11.59%, i.e. with greater fluctuations, the strategy of centralizing storage is more profitable. In the case of more expensive “Electronics”, the share of these costs in the sales value is lower: 2-6%. This may not seem like much, but it is important to remember that many companies only have a few percent profitability. Choosing the optimal strategy is therefore crucial for profitability.

For example, the profitability of the largest Polish companies listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange is: GRENEVIA (“Elektromaszynowy”) 13% 2023, but in 2020 only 3%. In WIELTON from the same industry, it was only 2 and 3%. In the clothing industry, the profitability of the tycoons of the Polish clothing industry in 2023 will only reach: LPP 9% and VISTULA RETAIL GROUP 8%.

The share of these costs is even higher in the case of a Gamma distribution, especially with 6 warehouses. The share of these costs in the sales value of cheap “Food” is 15.28% for 3% deviations from the average sales, and when sales fluctuate more (6%), this share increases to 19.87%. Even for the most expensive goods (“Electronics”), these costs account for 5.48% and 7.17% of the sales value, respectively.