Introduction

The whistleblower is a legal institution or mechanism created to protect and support people who report illegal activities, corruption, or abuse within public and private organizations or institutions, including academic institutions. This concept encourages transparency and accountability, providing a safe framework for those who want to bring information about wrongdoing to the public or authorities.

Through the public integrity whistleblower, whistleblowers benefit from protection against reprisals or negative consequences that could occur because of exposing illegal facts. This mechanism is essential for promoting ethics and integrity in public administration or other institutions, helping to fight corruption and ensure good governance. It is an important tool in strengthening a society based on principles of transparency and responsibility.

At the level of academic institutions, Signaling to Guidance and Monitoring (SCIM) procedures are carried out regarding the reporting of irregularities aimed at:

establishes the way of carrying out the activity, the departments and the people involved

assurance regarding the existence of adequate documentation for the performance of the activity.

ensures the continuity of the activity, including in conditions of personnel fluctuation by establishing some steps for the development of the procedural activity.

supports the audit and/or other competent bodies in audit and/or control actions, and the manager, in decision-making.

helps in the early identification of any irregularities found by employees within the institution.

establishes the way to protect the employees of the institution that reports irregularities.

From the perspective of legislative regulations, Law 361/2022 on the protection of whistleblowers in the public interest stands out, published in the Official Gazette no. 1218 of December 19, 2022, and entered into force on December 22, 2022. This law transposed, with a delay, the provisions of the European Directive 1937/2019, introducing new obligations for large employers. The purpose of the law is to facilitate the reporting of legal violations, both within private entities and within public authorities and institutions.

Among other measures, the law imposes the obligation for private companies to establish internal channels for reporting violations and procedures for managing these reports. Its implementation will be gradual: for companies with 250 or more employees starting from the law's entry into force, and for those with 50–249 employees from December 17, 2023.

Whistleblowers protected by Law 361/2022 can include not only employees but also third parties such as job candidates or independent individuals without contractual relations with the entity in question. Article 2 of the law states that protection applies to those who obtain information about violations in a professional context, including workers, self-employed individuals, shareholders, members of management or supervisory boards, volunteers, and interns. Additionally, the law applies to individuals making anonymous disclosures or who acquire information during recruitment processes or pre-contractual negotiations. What are the rights of whistleblowers?

In accordance with European Directive 1937/2019, whistleblowers are persons who report and which oversees compliance with the law, and they benefit from two important rights, namely the right to be protected against reprisals and the right to privacy when making reports.

We can provide you with a general list of resources that may be relevant to the topic of public whistleblowing for integrity, particularly in the context of supporting academic ethics. Please note that you should check the availability of these resources in your local library or online databases.

The public whistleblower is a legal entity or tool created to ensure the protection and support of people who report illegal activities, corruption, or abuses within public and private organizations or institutions, including academic institutions. This concept encourages transparency and accountability, providing a safe environment for those who want to bring information about wrongdoing to the public or authorities.

Through the public integrity whistleblower, whistleblowers benefit from protection against retaliation or negative consequences that may arise from exposing wrongdoing. This mechanism is essential for promoting ethics and integrity in public administration or other institutions, helping to fight corruption and ensure effective governance. It is a crucial tool in strengthening a society based on principles of transparency and responsibility.

Within the academic institutions, SCIM procedures are developed regarding the reporting of irregularities, with the following objectives: establishing the way the activity is carried out, the departments and the people involved; ensuring the existence of adequate documentation for the performance of the activity; maintaining the continuity of the activity, including in conditions of staff fluctuation by establishing the steps for carrying out the procedural activity; supporting the audit and/or other competent bodies in audit and/or control actions, as well as supporting the manager in decision-making; early identification of any irregularities found by employees within the institution; establishing the way to protect the institution's employees who report irregularities.

Article 2 of Law no. 361/2022 outlines that the law applies to individuals who report legal violations discovered in a professional context. This includes employees, self-employed persons as defined by Article 49 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU, shareholders, members of management or supervisory boards, volunteers, and both paid and unpaid interns. Additionally, those working under the direction of a contracting party, including subcontractors and suppliers, are covered.

The law also extends to individuals whose employment hasn't yet begun, such as those involved in recruitment or pre-contractual negotiations, and applies even if the employment or service relationship has ended. Moreover, the law provides protection for individuals making anonymous reports or disclosures about legal violations.

Under European Directive 1937/2019, whistleblowers have two key rights: protection from retaliation and confidentiality when making reports.

The purpose of this study is to investigate the following key research questions:

What are the primary challenges to ensuring academic integrity within educational institutions, and how do they impact the overall transparency of the educational environment?

How does the implementation of whistleblowing mechanisms, specifically the protection and confidentiality provided under European Directive 1937/2019 and national laws such as Law no. 361/2022, contribute to safeguarding academic integrity?

What is the effectiveness of specific whistleblower mechanisms, such as the SCIM (Signaling to Guidance and Monitoring) procedures, in fostering a transparent and ethically responsible academic environment?

This structure ensures a focused analysis that moves beyond a general overview to specifically investigate how these tools and legal frameworks support academic integrity. By addressing these questions, the study aims to provide insights into the effectiveness of whistleblower protections and mechanisms in academic settings and identify areas where additional support may be beneficial for educational institutions seeking to maintain transparency and integrity.

Literature Review

In scientific literature, the definition of whistleblowers varies depending on the author's perspective. For instance, [

1] describes a whistleblower as someone who acts to prevent harm to others, rather than for personal gain. They typically attempt to resolve the challenge within the organization first, presenting evidence that would convince a reasonable person. The harm they aim to prevent can be physical, such as illegal toxic waste disposal; financial, such as the misuse of public funds; or legal, involving violations of laws.

[

26] provides an insight into the current state of the whistleblowing process in several jurisdictions around the world. Furthermore, this paper also presents topics of wide and growing interest among legislators, professionals, and academics around the globe, and the paper examines the various aspects of warning. At the same time, the authors of the paper investigate the level of legal protection granted to whistleblowers, the persons and behaviors protected, as well as the types of behaviors against which they are insured. The authors' approach is carried out through general comparisons and country-specific analyses, providing information on abuse reporting practices in various jurisdictions. Countries studied include Canada, Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and the USA. A concise summary in tabular form summarizes information on whistleblowing in 23 countries. The chapters were initially prepared for presentation at the XIX International Congress of Comparative Law, which took place in Vienna on July 20 and 21, 2014, organized by the International Academy of Comparative Law. An important reference is

The Whistleblower's Handbook [

27], a trusted guide on reporting workplace misconduct. It has been revised to include updated information on whistleblowing in areas such as wildlife protection. The manual also includes a new "Toolkit" for international whistleblowers. This guide details virtually every federal and state whistleblower law and, in its bulk, provides a step-by-step overview of over twenty mandatory whistleblower rules. This broad spectrum covers issues such as identifying the best federal and state laws, as well as the risks associated with relying solely on the corporation's “internal hotlines” to obtain the evidence necessary to win the case.

Research on whistleblowing has faced challenges due to a lack of a strong theoretical foundation. In their work, [

19] present theories on motivation and power dynamics, aiming to develop a whistleblowing process model. They focus on how organizational members decide to report violations and how authorities respond. Additionally, the paper provides a rare review of empirical studies in this area.

Another study by [

9] explores whistleblowing across multiple disciplines, defining it as the act of exposing illegal or unethical practices within organizations to those who may be impacted. This is particularly relevant in the tourism industry, where whistleblowing plays a critical role in addressing unethical behavior. Such misconduct can stem from internal actions, individual traits of employees, or external factors like industry practices, societal values, and organizational policies. Therefore, encouraging and legally protecting whistleblowers who report unethical and illegal behavior to the authorities is an essential necessity [

16]. The work [

13] represents a valuable tool for public managers who are run daily with numerous ethical challenges in their work environment. It provides a variety of practical tools and strategies that these public managers can use in making ethical decisions [

9] in a public service characterized by ambiguity and constant pressure. It also provides new material on a variety of topics. Relevant guides to whistleblower-related and technical details include [

5,

21], and [

18]. Furthermore, government documents issued by empowered institutions that support whistleblowers include the following [

29,

30], and [

10].The attributes of whistleblowers and their moral value system and political orientation are under close scrutiny through the similarities and differences between conservatives and liberals in the United States, as outlined in the works made by the authors [

2,

6], and [

17].

Education regarding the concept of public integrity whistleblower, its role, and its functions: we appreciate that it is a priority to disseminate knowledge on this topic at the level of high schools and universities, especially in the context of the digital era [

15].

Research Methodology

Starting from the definitions of the concepts reflected both in the specialized scientific literature and in the legislation, we appreciate that the knowledge tool of how to code whistleblowers and associate them with the fields of activity in which they are integrated represents the central element of the methodology of our study.

Whistleblowers must benefit from these rights when they make a report, regardless of whether they do it through the internal or external procedure, i.e., reporting to certain public authorities or in the public space, which, in most cases, is presented by journalists.

In addition to whistleblowers, the law defines a "facilitator" in Article 3, point 8, as an individual who provides confidential assistance to the whistleblower during the reporting process within a professional context.

The law's provisions for protection, support, and remediation extend to:

- ✓

Facilitators.

- ✓

Third parties related to the whistleblower, such as colleagues or family members, who may face retaliation.

- ✓

Legal entities connected to the whistleblower, either through employment or other professional relationships.

- ✓

Whistleblowers who initially reported violations anonymously but were later identified and faced reprisals.

- ✓

Whistleblowers who report violations to relevant institutions, bodies, or agencies of the European Union.

Table 1.

Coding of whistleblowers/integrity experts.

Table 1.

Coding of whistleblowers/integrity experts.

| ENCODE |

Specification |

ENCODE |

Specification |

| A1 |

Whistleblower from public media institution |

A14 |

Whistleblower from the private environment |

| A2 |

Whistleblower from the health system |

A15 |

Whistleblower from the road infrastructure system |

| A3 |

Whistleblower from the working apparatus of the Government |

A16 |

Whistleblower from the national statistical system |

| A4 |

Whistleblower from the education system |

A17 |

Police whistleblower |

| A5 |

Whistleblower from public media institution |

A18 |

Alert from the health system

|

| A6 |

Whistleblower from the health system |

A19 |

Alert from the local authority (town hall of

municipality)

|

| A7 |

Whistleblower from the health system |

A20 |

Whistleblower in the field of infrastructure of

water management

|

| A8 |

Whistleblower from the forestry system |

A21 |

Whistleblower in the field of infrastructure of

water management |

| A9 |

Police whistleblower |

A22 |

Research Alert |

| A10 |

Whistleblower from the forestry system |

E1 |

Lawyer |

| A11 |

Whistleblower from the public transport system |

E2 |

Independent expert |

| A12 |

Whistleblower from the public transport system |

E3 |

Independent expert |

| A13 |

Police whistleblower |

E4 |

Independent expert |

Certainly, at the level of each public integrity whistleblower, terms defined according to the current legislation in force, namely Law no. 361/2022, are not only an obligation but also a responsibility to ensure not only knowledge but also their transposition in the execution activity of theirs.

This methodology adopts a multidimensional approach, encompassing a legislative and literature review and an advanced, context-based coding technique for whistleblowers, associating them with relevant fields of activity.

1. Legislative and Literature Review: This initial phase aims to identify and define key concepts (such as "whistleblower," "facilitator," and "protection mechanism") through a detailed analysis of European legislation, including Directive 1937/2019 and Law No. 361/2022, as well as existing studies on academic integrity. This contextual analysis establishes a foundation for understanding the role of whistleblowers in maintaining integrity within educational settings and identifies associated challenges and limitations.

2. Context-Based Coding of Whistleblowers and Activity Fields: To provide a deeper understanding of the role of whistleblowers in the academic domain, we adopt an extended coding technique. This method not only identifies fields of activity but also includes a detailed classification of reporting types and specific contributing factors. The coding involves categorizing whistleblowing instances based on the professional context and reporting channels used (internal, external authorities, or public reporting), incorporating information about the extended protections under current legislation for whistleblowers, facilitators, and third parties (as outlined in Article 3, point 8).

3. Evaluation of Protection Mechanisms’ Effectiveness in Academic Settings: Based on the whistleblower typology and activity fields from the coding stage, the methodology includes a qualitative analysis of the effectiveness of protective measures (such as confidentiality and protection from retaliation) on the climate of academic integrity. This analysis explores SCIM mechanisms and their role in academic institutions, as well as the impact of whistleblowing on institutional ethics and accountability.

4. Impact Analysis and Recommendations for Strengthening Whistleblowing Mechanisms in Academia: The final phase evaluates how these mechanisms can be enhanced and offers recommendations to improve existing measures, facilitating a transparent and ethical educational environment. Conclusions will emphasize the importance of a robust legislative framework and a well-structured reporting system in promoting integrity within academic settings.

With this comprehensive, integrated approach, the proposed methodology aims to move beyond a simplistic analysis, offering a detailed perspective on the dynamics and challenges of whistleblowing in academic environments.

Results and Discussion

Transposing the directive into the national laws of each EU member state poses significant challenges, primarily due to cultural and political factors that hinder effective whistleblower protection. The term "integrity whistleblower" often carries negative connotations, being likened to informer or traitor, which affects public perception.

Many countries exhibit a general reluctance to establish and enforce whistleblower protections. In some instances, existing laws against disclosure, such as defamation and slander statutes, further discourage potential whistleblowers. However, there are legal frameworks in certain states that could support the expansion of whistleblower rights. For example, Bulgaria's conflict-of-interest law and provisions in the labor codes of the Czech Republic and Italy may serve as foundations for more comprehensive whistleblower legislation.

Nonetheless, for these legal measures to be effective, societal attitudes towards whistleblowers must improve. A recent study in the Czech Republic highlighted that while respondents recognize the importance of whistleblowers, they also acknowledged the numerous challenges these individuals face, often leading to negative outcomes.

Enhancing the environment for whistleblowers in the assessed EU Member States requires addressing both legal and cultural barriers that impede the implementation of whistleblower protections. Specific recommendations were proposed for each country based on individual case studies.

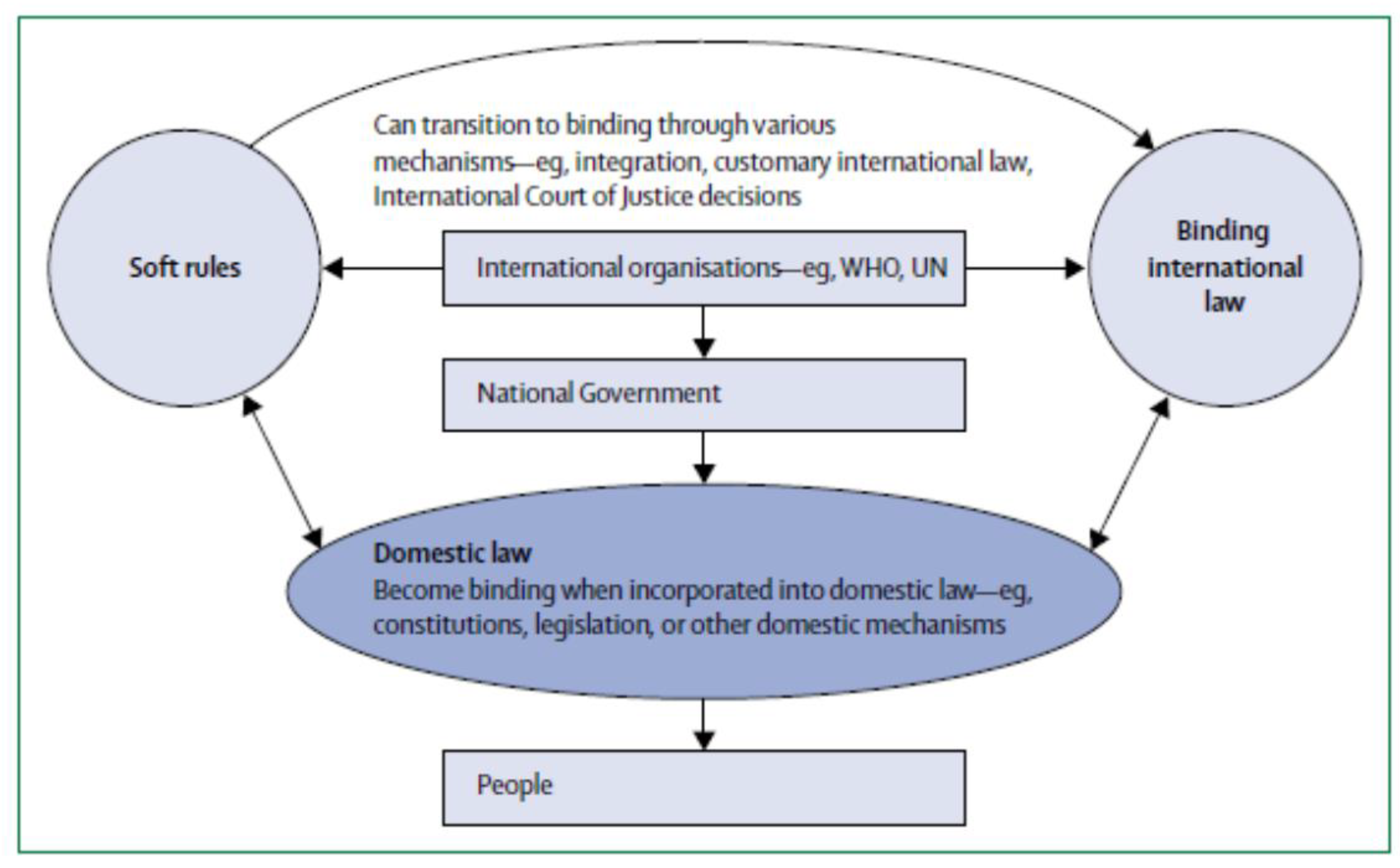

Figure 1.

Existing relationships between national and international legislation. Source: [31]

Figure 1.

Existing relationships between national and international legislation. Source: [31]

Legal protections for whistleblowers will only be effective if public perceptions of them improve. Understanding public integrity involves defining it as the fulfillment of three key conditions: (a) incorruptibility of decisions regardless of beneficiaries, (b) adherence to transparency, competitiveness, ethics, and morality, and (c) effective and efficient administration. To achieve these, "safety nets" must be in place, including strict compliance with procedures, transparency in administrative processes, avoidance of favoritism, and adherence to legal standards.

Public interest whistleblowing is characterized as a good-faith report of any act that violates laws, ethical standards, or principles of good administration. This definition requires careful consideration of the whistleblower's role, the reported issue, and the context of the report. For example, an employee in a hospital can be seen as a whistleblower for reporting unethical nursing practices, while a patient reporting the same issue would not be classified as such.

Integrity whistleblowers, who may include public officials and other professionals, often face retaliation for their disclosures. While many countries have enacted laws to protect whistleblowers, these laws do not cover all potential challenges they may encounter. Whistleblowers are encouraged to remain morally and ethically steadfast despite potential repercussions.

Internal whistleblowers are typically employees tasked with reporting misconduct anonymously, using mechanisms like dedicated hotlines. Studies indicate that people are more likely to report wrongdoing when complaint systems provide confidentiality and flexibility. Furthermore, institutional reporting mechanisms promote an environment where employees feel safe to voice concerns.

External whistleblowers report misconduct to entities outside their organization, such as law enforcement or anti-corruption agencies. This approach has gained traction due to inadequate protections for whistleblowers. Organizations such as the Whistleblowing International Network offer support in these situations.

In the private sector, whistleblowing often goes unnoticed compared to the public sector, although it is widespread and sometimes suppressed by strict corporate regulations. For instance, an employee may report various challenges, from harassment to financial fraud. Despite existing protections, many still fear retaliation, prompting legislative efforts such as the Dodd-Frank Act in the U.S., which incentivizes whistleblowing with financial rewards for substantial disclosures.

Ultimately, whistleblowers face difficult choices between exposing wrongdoing for ethical reasons and risking their job security and reputation. Research indicates that a significant percentage of whistleblowers experience negative repercussions, such as termination or forced retirement.

The European Commission has acknowledged the need for enhanced whistleblower protections and is committed to ensuring compliance with EU laws. The effectiveness of a whistleblower relies not only on professional skills but also on their moral integrity and mental resilience.

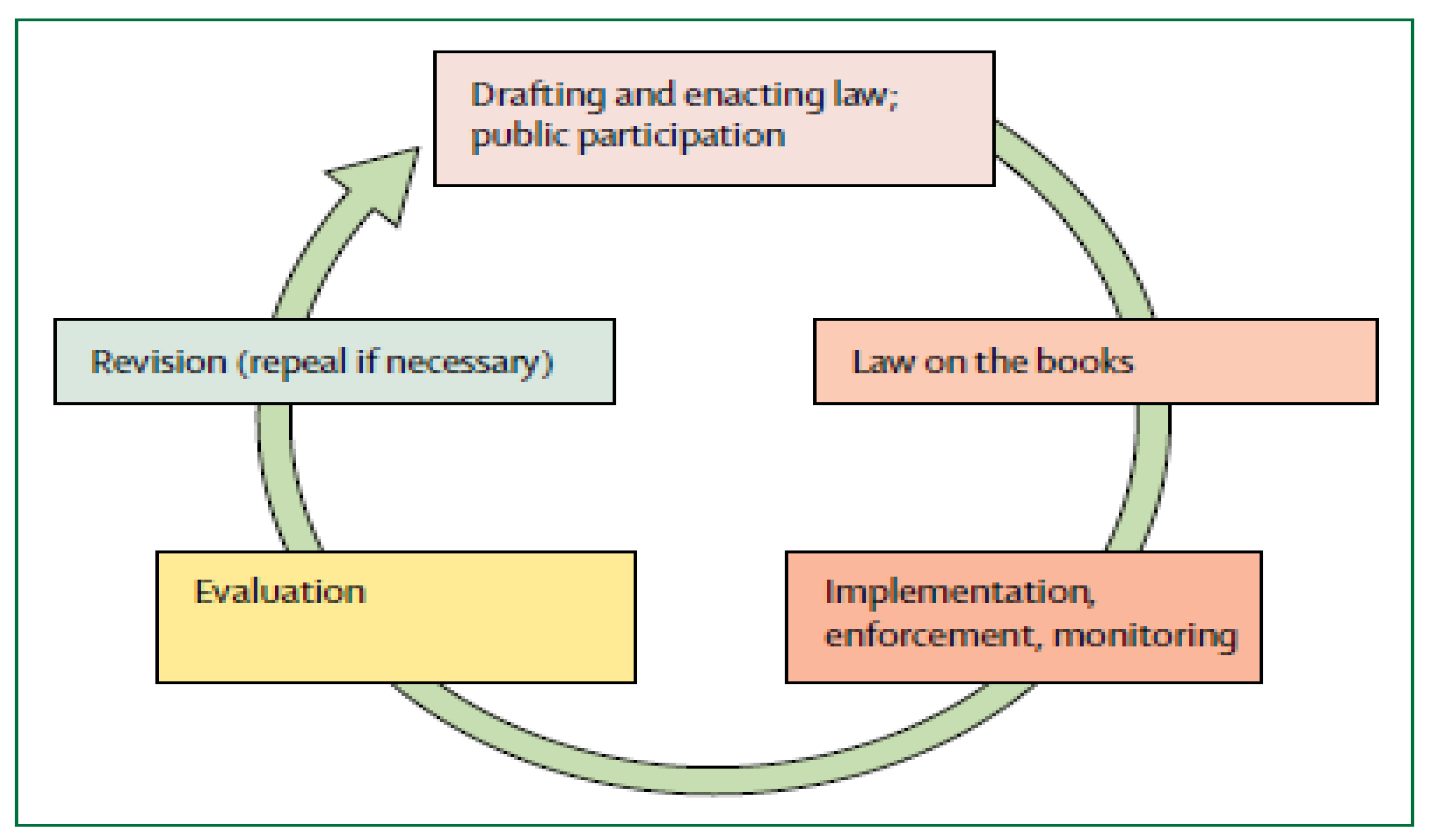

Figure 2.

Characteristics of an effective legal framework. Source: [31].

Figure 2.

Characteristics of an effective legal framework. Source: [31].

Research on the psychological effects of whistleblowing is limited, but the experiences can significantly impact their mental health. Whistleblowers often face silence and hostility when attempting to report misconduct [

19,

20,

22], leading to high levels of stress, substance abuse, anxiety, and, in severe cases, depression and suicidal thoughts, which may affect about 10% of them [

3,

11]. Symptoms can resemble those of PTSD, although it's uncertain if the experiences qualify for a formal diagnosis [

3,

4].

The situation can be exacerbated by retaliatory actions from those accused of wrongdoing, who may employ tactics such as gaslighting to undermine the whistleblower’s credibility and mental stability [

7,

14].

In Romania, whistleblower protection has been in place since 2004 through "Law no. 571/2004," which safeguards public sector personnel disclosing legal violations. This law, the first of its kind in a continental legal system, only applies to public employees, leaving private sector workers with limited protections under general labor laws [

28]. The EU Directive on whistleblower protection has introduced clearer regulations for the private sector, outlining the obligations of employers and the procedures for integrity whistleblowers.

Importantly, if whistleblowers face reprisals, they have the right to appeal in court [

25]. Many countries, including Romania and Ireland, have legal provisions to support whistleblowers throughout the reporting process, though Romanian protections remain restricted to public sector employees, while private employees are covered under the labor code.

There is a pressing need for clear regulations on retaliation against whistleblowers to ensure they aren't solely reliant on the judicial system's interpretation of unfair dismissals. Current legal frameworks can serve as a foundation for enhancing whistleblower protections [

8]. A recent Czech study highlighted that while participants recognize the importance of whistleblowers, they face numerous challenges that often lead to negative outcomes.

Many whistleblowers reported experiencing various forms of retaliation, including:

- ✓

Intense scrutiny and audits of their work.

- ✓

Perceived abusive fines following these audits.

- ✓

Disciplinary actions leading to salary cuts, reassignments, or even dismissal.

- ✓

Organizational changes that eliminate their positions.

- ✓

Forced relocations or isolations within the workplace.

- ✓

Budget cuts affecting their departments.

- ✓

Harassment targeting them and their families.

- ✓

Legal actions against them, including civil and criminal complaints.

Retaliation tends to escalate after a whistleblower's reports are made public. Most whistleblowers interviewed were unaware of the existing whistleblower protection laws at the time of their reports. Many began by reporting issues internally but felt compelled to take their concerns to the media when internal mechanisms failed to act [

22].

Moreover, whistleblowers in law enforcement often lack official recognition under existing legislation, which can further deter potential future whistleblowers. Union leaders expressed concern that whistleblowers were more vulnerable to institutional retaliation, serving as examples to dissuade others from reporting misconduct.

Without explicit internal regulations and employee education regarding whistleblower laws, institutions frequently claim that the whistleblower did not follow proper procedures, thus undermining their status [

23,

24]. Despite the presumption of good faith for whistleblowers, institutions typically react swiftly with punitive measures rather than addressing the reported challenges.

All whistleblowers in the study faced some form of retaliation, most commonly salary reductions, involuntary transfers, and diminished job responsibilities. Many felt targeted by institutional efforts to "damage the image" of the organization once their reports gained public attention.

A notable proportion of whistleblowers challenged disciplinary actions in court, with some successfully overturning decisions. However, many reported a lack of understanding of whistleblower laws among legal professionals, complicating their ability to navigate the system effectively.

Whistleblowers expressed frustration over the inability to enact systemic change, attributing stagnation to political influences. Support for whistleblowers often came from external sources rather than institutional mechanisms, as many felt hostility and intimidation from public institutions.

The institutions involved in the study exhibited a consistent pattern of retaliation, including audits, disciplinary proceedings, and structural changes aimed at undermining whistleblowers. The role and importance of the public whistleblower to be integrated into academic ethics.

The whistleblower has a crucial role in promoting and maintaining academic ethics. In an academic environment, integrity is essential for trust in the education system and for ensuring a fair and equitable learning process. Here are some ways the whistleblower can influence academic ethics:

Preventing academic fraud: The Public Integrity Whistleblower can help prevent and combat academic fraud by reporting situations where students or teachers violate academic integrity rules, such as plagiarism or falsifying results.

Protecting research integrity: In academic research, transparency and fairness are crucial. The public integrity whistleblower can help identify situations where researchers or institutions violate research ethics, thus contributing to maintaining scientific integrity.

Ensuring fairness in evaluation: The whistleblower can bring unfair or discriminatory practices in the evaluation process of students or teaching staff to the attention of academic authorities, thus supporting a fair academic environment.

Reinforcement of academic values: The public integrity whistleblower can help reinforce the core values of education, such as honesty, respect, and responsibility. By reporting abuses or ethical violations, you support an academic environment where these values are promoted and respected.

Following the considerations mentioned above, we appreciate that the public integrity whistleblower plays an essential role in maintaining and promoting academic ethics at the level of public and private institutions, thus contributing to the creation of an environment of knowledge based on moral principles and integrity.

The instrument that regulates and supports academic ethics is the Code of Ethics. The ethical code of the personnel within the academic institutions defines the values and principles of conduct that must be applied in the relations between the employees, between them and the institution, as well as in the relations with the external environment. At the same time, the code is a guide for increasing the responsibility and involvement of the staff within the institution in the realization of research projects and programs and in the management and development of the entire activity of the unit.

The principles contained in this document are not exhaustive. Associated with the sense of responsibility towards the academic institution and towards partners and authorities, they establish essential rules of behavior and ethics applicable to the entire staff of the institution.

These guidelines complement existing laws and regulations in education, research, and public administration, aligning with the ethics codes for educators and researchers as well as those governing academic staff. The ethical code is sanctioned by the institution’s director and disseminated to employees through the human resources department. Compliance with this Code is mandatory for all staff, with violations leading to disciplinary action.

The code of ethics aims to enhance the quality of work performed by academic personnel and ensure proper administration of public interest objectives. It focuses on preventing non-compliance and corruption through:

Establishing professional conduct standards to foster social and professional relationships that enhance the institution's reputation.

Promoting an environment of trust and mutual respect among staff and between the institution and its external stakeholders.

Key principles guiding professional behavior within the institution include:

- ✓

Rule of law, all staff must respect the Constitution and national laws.

- ✓

Professionalism, employees are expected to carry out their duties responsibly and effectively.

- ✓

Public interest, the public interest must take precedence over personal interests in job performance.

- ✓

Impartiality and independence, the staff should maintain objectivity in their duties, free from external influences.

- ✓

Moral integrity, employees are prohibited from soliciting or accepting any undue advantages or benefits.

- ✓

Freedom of thought and expression, the staff can express their opinions while adhering to legal and ethical standards.

- ✓

Honesty and fairness, the employees should act in good faith and align with societal and academic values.

The Code also addresses conflicts of interest, defined as situations where personal financial interests could impact an employee's impartiality in fulfilling their responsibilities. The principles to mitigate conflicts of interest include impartiality, integrity, transparency, and prioritizing the public good.

Employees may be in conflict-of-interest situations if they have personal relationships with individuals or entities involved in decision-making processes affecting their duties. To avoid conflicts, staff must:

- ✓

Refrain from entering into business relationships that could compromise their responsibilities.

- ✓

Remain uninfluenced by personal interests or pressures.

- ✓

Avoid situations that could create conflicts between institutional and personal interests

- ✓

Steer clear of activities that could sway their decision-making in favor of personal interests.

In case a conflict of interest arises, the employee must abstain from any related decision-making and promptly notify their supervisor to ensure impartiality in their role. The institution will assign another qualified employee to handle the matter. Breaches of these conflict-of-interest guidelines may result in disciplinary, civil, or criminal consequences. Each Code of Ethics is built upon these core values.

The commitment—this implies the desire of each employee and the management of the academic institution to progress day by day in fulfilling the position held and to improve their performance, according to the action plans decided by mutual agreement, to ensure the development of high-quality research works.

Teamwork—that is, all the employees of the academic institution are part of a team that must be supported in its entirety, and all its members must receive support from the management. Team spirit must be felt and expressed in relationships with other collaborators, regardless of their cultural or professional origin.

Internal and external transparency—internally, transparency means sharing solutions to problems, based on available information, and quickly resolving difficulties that may cause damage to the academic institution, the team, and partners of the academic institution. Externally, transparency means developing relationships with the partners of the academic institution based on trust and ethics.

Human dignity—every employee is unique, and their dignity must be respected. Each employee of the academic institution is guaranteed the free and full development of their personality. All employees of the academic institution must be treated with dignity regarding their way of life, culture, faith, and personal values. Rules of behavior and conduct in collegial relations mentioned in the Code of Ethics.

There must be cooperation and mutual support between colleagues, motivated by the fact that all employees are mobilized to achieve common objectives, and communication through the transfer of information between colleagues is essential in solving problems efficiently; colleagues owe each other mutual respect, consideration, the right to an opinion; any divergences, dissatisfactions, arising between them will be resolved without affecting the collegiality relationship, avoiding the use of inappropriate words, expressions and gestures, showing a conciliatory attitude; between colleagues there must be sincerity and fairness, the opinions expressed must correspond to reality, any grievances between colleagues can be expressed directly, without bias; collegial relationships should be founded on mutual respect, professional recognition, and performance. Employees are expected to extend understanding and support to colleagues with special needs. A collaborative team spirit should be consistently encouraged, fostering openness to suggestions and constructive criticism. It is essential for staff to share knowledge and experiences to promote collective professional development. Additionally, employees are obligated to assist one another through collegial support, cooperating sincerely on collaborative projects.

The Ethics Code also outlines relevant legislation, including Ordinance no. 57/2002 on scientific research and technological development, as amended; Law no. 319/2003 concerning the status of research and development personnel; Law no. 206/2004 on ethical conduct in research, technological development, and innovation; and the Statute of the academic institution, as well as the Higher Education Law of 2023. This list is not exhaustive.

Our study analyzed several case studies from diverse academic institutions to illustrate the experiences of integrity whistleblowers and the challenges they face in maintaining an ethical and transparent academic environment. These cases include both internal reporting through institutional mechanisms and external reporting to independent bodies. Additionally, interviews with whistleblowers, legal experts, and institutional representatives provided insights into the perceptions and experiences of those involved in whistleblowing cases within universities and other higher education institutions.

A particular case at a state university illustrated an instance of internal reporting regarding favoritism in the allocation of scholarships, where the whistleblower used the internal reporting hotline. Despite confidentiality measures, the whistleblower was identified and subsequently faced retaliation in the form of reassignment to a position with reduced responsibilities. Despite some support from colleagues, the whistleblower reported a lack of backing from the institution’s leadership, highlighting the limitations of internal protection mechanisms.

Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis of Whistleblowers' Experiences

We collected and analyzed quantitative data on the types and frequencies of reprisals, as well as the outcomes of legal proceedings initiated by whistleblowers. The most common reprisals included salary reductions (60%), involuntary transfers (45%), and diminished job responsibilities (35%). Among those who challenged disciplinary actions in court, only a portion (around 25%) succeeded in overturning decisions, pointing to the complexity of the legal framework and the limited effective protection in practice.

Qualitatively, the interviews revealed a general trend of intimidation and hostility toward whistleblowers, particularly in institutions where protection regulations are not clearly communicated or implemented. Specifically, whistleblowers mentioned difficulties in accessing adequate support within the institution and a discouraging attitude from both peers and leadership.

Effectiveness of Institutional Protection Mechanisms

The results indicate that the effectiveness of institutional protection mechanisms for whistleblowers is limited. Although national and EU legislation provides specific rights for whistleblowers (confidentiality and protection from retaliation), the implementation of these measures varies significantly between institutions. Case studies showed that the lack of clear procedures and a supportive culture for integrity reporting within academic institutions often led to cases where whistleblowers were marginalized.

The SCIM mechanisms, while implemented in some universities, have proven insufficient in preventing reprisals or providing real support to whistleblowers. Internal reporting is often discouraged due to fears of retaliation, and whistleblowers frequently resort to external reporting only as a last resort, suggesting a need for better institutional support to prevent and penalize retaliation.

Comparative Analysis of the Legislative Framework and Policy Improvement Recommendations

Comparing the applicability of national and European legislation, the results suggest that while the legislation is well-intentioned, its application and interpretation within academic institutions remain limited. According to interviews with legal experts, a common challenge is the lack of clarity in the law and internal regulations regarding reporting procedures and whistleblower protection.

To address these gaps, we recommend the following measures:

- ✓

Clarify and standardize internal reporting procedures across all academic institutions and establish clear measures to protect whistleblowers from retaliation.

- ✓

Implement training programs for academic and administrative staff on whistleblower rights and protections, including clear sanctions for retaliation.

- ✓

Develop an institutional culture of integrity support, encouraging transparency and accountability so that whistleblowers are viewed as advocates of ethics and are effectively protected.

The findings of this study highlight the need for more robust protection for whistleblowers in academic institutions, showing that without an effectively enforced protection framework, current mechanisms may discourage integrity reporting.