Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. A Brief History of Drug Discovery and Development

2.1. Early Stage of Drug Discovery

2.2. Keynote Discoveries in Drug Development

2.3. Evolution of Pharmaceutical Practices

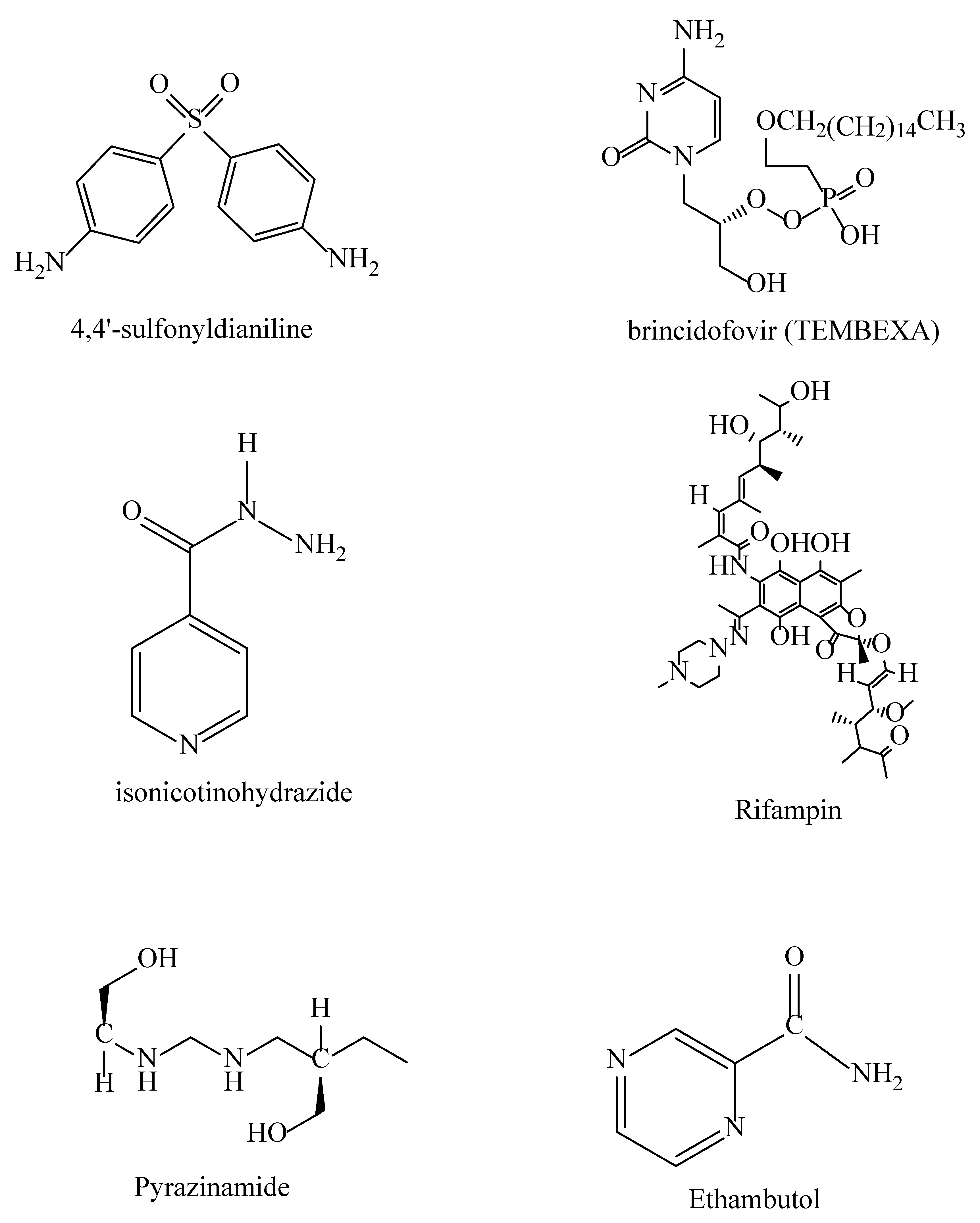

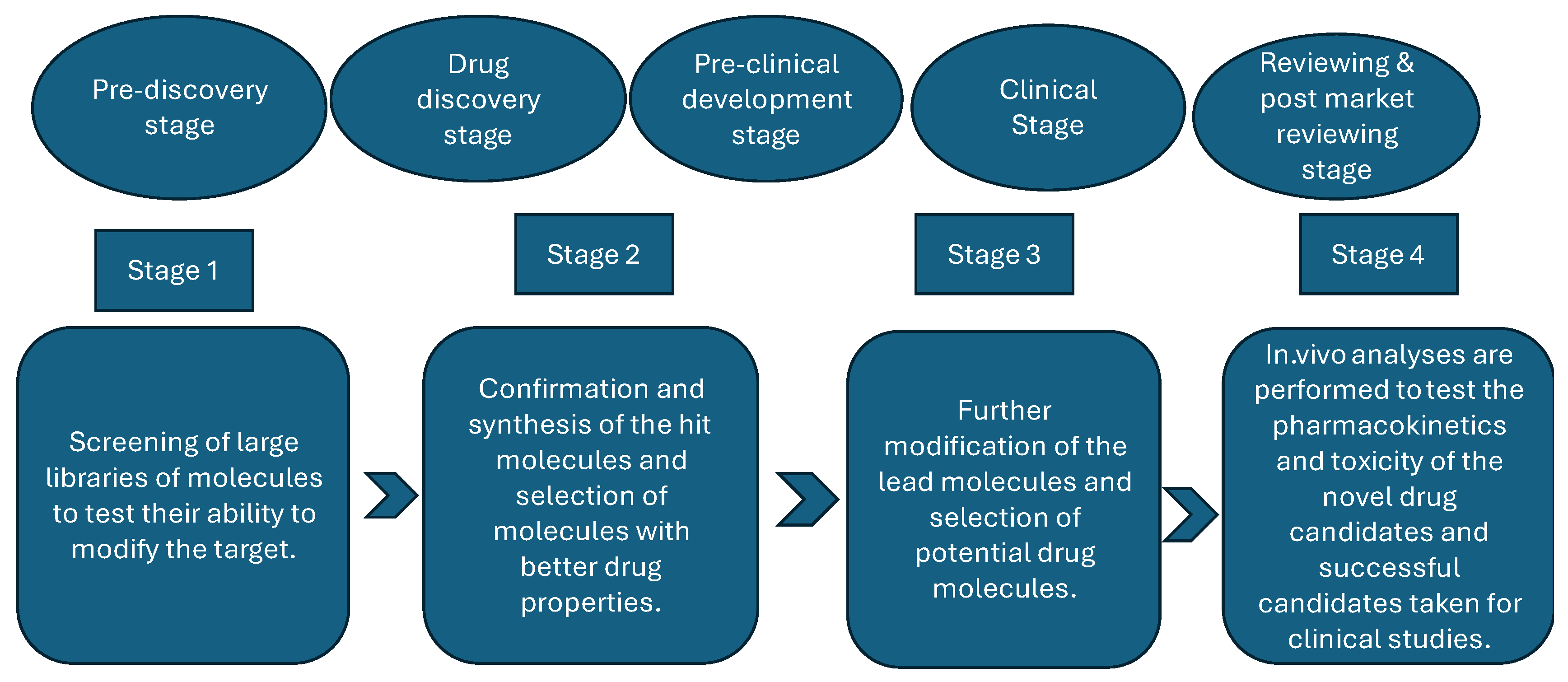

3. Conventional Drug Discovery and Development Process

- The pre-discovery stage entails conducting basic research to understand the mechanisms that result in the occurrence of diseases while also identifying possible targets, such as proteins. It is the stage at which scientists conduct basic research to understand the disease and formulate an appropriate target molecule [52].

- The drug discovery stage is the most important of all the stages, as it entails researching possible drug molecules (chemical or biological) that may have the potential to cure the investigated disease or at least alleviate the symptoms [53]. This stage is crucial because it allows for the discovery of target and lead molecules, followed by the validation and synthesis of drug candidates. The ultimate stage of the phase is drug development [54].

- The preclinical development stage entails studying the mode of action of drug candidates and researching the potential toxicity of the developed drugs; that is, researchers gather crucial data on medication safety, feasibility, and repeated testing—usually in laboratory animals—during this stage, which precedes clinical trials (testing in humans) [55].

- The clinical stage involves conducting the study by testing the safety of the developed drugs in humans. If the tests prove successful, the study is expanded to include many more participants to determine the drug’s effectiveness when consumed by numerous people with various traits, such as body weight, and so on [5].

- The reviewing, approval, and post-market monitoring stage entails the approval or disapproval of the developed drug, including conducting surveillance to confirm the efficacy and safety of pharmaceutical products and to detect the occurrence of diseases caused by adverse reactions [56].

4. Integration of AI in Drug Development

4.1. AI Technologies and Their Applications

- (i)

- Machine learning (ML) is a branch of AI that enables systems to learn from provided data and improve their performance based on that data without requiring additional programming [63]. ML’s application in drug discovery involves identifying potential drug candidates by predicting ligand-receptor interactions. ML also has the potential to predict ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) conditions, which are pharmacokinetic parameters that affect a drug’s safety, efficacy, and clinical success. These parameters help avoid late-stage drug failures by flagging poor ADMET conditions early [64].

- (ii)

- Deep learning (DL) is a branch of machine learning that uses artificial neural networks to teach computers to perform tasks that humans can do [65]. One major application of DL in drug development is its ability to generate novel drug candidates with desired properties. Additionally, DL can analyze large datasets from imaging and genomic data related to drug efficacy and safety [6].

- (iii)

- Reinforcement learning is a branch of machine learning that teaches computer software to make optimal decisions. DL’s application in drug discovery includes predicting synthetic pathways for synthesizing new molecules and iteratively modifying compounds to improve their efficacy or reduce their toxicity [66].

- (iv)

- Generative models are machine-learning models that design new molecules with properties and constraints similar to those of the molecules used to train the models. Their advantage lies in expanding the molecule bank by creating novel molecules; they also have the potential to tailor molecules for specific therapeutic agents [67].

- (v)

- Bioinformatics is a branch of molecular biology that extensively analyzes biological data using various computational tools to manage and interpret it. This discipline provides information such as DNA and amino acid sequences and annotations about those sequences [61].

- (vi)

- Cheminformatics is a field focused on solving chemical problems using computers. It involves tasks such as coding chemical structures, modeling properties, and developing databases [68].

- (vii)

- Molecular descriptors are quantitative measures of molecular properties, such as molecular weight, geometry, and polarity. Their advantage is that they simplify complicated molecular structures into numerical values, enabling model training. They also allow for determining the bioactivity of designed molecules [69].

- (viii)

- Molecular fingerprints (e.g., chemical fingerprints and pharmacophore fingerprints) are techniques that describe a molecule’s structure by converting it into bit strings. They aid in drug development by facilitating similarity-based searches of molecules, and they are also useful for the virtual screening and clustering of molecules with similar activity profiles [70].

- (ix)

- Molecular docking scores are computer-generated estimates of how strong the binding affinity of a small drug molecule to the target molecule is. The score is derived from computer simulations and often guides prioritizing molecules with high binding affinities [71]. For instance, Pang and Kozikowski successfully utilized computer-based molecular docking to predict through rigid docking, the bound pose of huperzine A, [72] thereby dramatically reducing the time needed to conduct molecular docking experimentally. Computer-based molecular docking was also used successfully in the identification of common chemoresistance-associated genes that impact cancer survival [73].

- (x)

- Drug screening (also known as toxicity test) is a process used to determine the presence of drugs or chemicals in a person’s body. It can be used to identify illegal drugs, monitor drug use, or assess the effects of an overdose. Various AI parameters such as molecular descriptors and dataset parameters have been utilized during drug screening.

- (xi)

- Fragmentation-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD) is rapidly progressing as another option for innovative and efficient early-stage de novo drug discovery [76,77]. “The main goal of de novo [drug discovery] is to generate chemically sound and original structures predicted to have desired physicochemical and biological properties” [78].

4.2. Advantages of AI in Drug Discovery

4.3. Challenges of AI in Drug Discovery

4.3. Case Studies

4.4. Comparison Between AI-Enhanced Drug Discovery and Traditional Drug Discovery

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Ritter, J. M., MacEwan, D., Flower, R., Robinson, E., Henderson, G., Fullerton, J., Loke, Y. K., Rang and Dale’s pharmacology, 10th ed, London New York Oxford, 2024.

- Dias D. A., Urban, S., Roessner, U., Metabolites, 2012, 2(2), 303-336.

- Paterson, G., R., Neilson, J. B., Roland, C. G., Canadian Medical Association Journal, 1982, 127 (10), 948.

- Crocq, M. A., Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2007, 9(4), 355-61.

- Atanasov, A. G., Waltenberger, B., Pferschy-Wenzig, E. M., Linder, T., Wawrosch, C., Uhrin, P., Temml, V., Wang, L., Schwaiger, S., Heiss, E. H., Rollinger, J. M., Schuster, D., Breuss, J. M., Bochkov. V., Mihovilovic, M. D., Kopp, B., Bauer, R., Dirsch, V. M., Stuppner, H., Advanced Biotechnology, 2015, 33(8), 1582-1614.

- Paul, D., Sanap, G., Shenoy, S., Kalyane, D., Kalia, K., Tekade, R. K., Drug Discovery Today, 2021, 26(1), 80-93.

- Matt, C., What is Machine Learning? Definition, Types, Tools & More, Accessed 23 September 2024, @11: 00 am.

- Kinghorn, A.D., Pan, L., Fletcher, J.N., Chai, H., Journal of Natural Products, 2011,74,1539–1555.

- Singh, S., Kumar, R., Payra, S., Singh, S. K., Cureus, 2023, 15(8), e44359.

- Gad, H. A., El-Ahmady, S. H., Abou-Shoer, M. I., Al-Azizi, M.M., Phytochemical Analysis, 2013, 24(1),1–24.

- Noohi, M., Inavolu, S.S., Sujant, M., Springer Nature, 2022, 65(3), 399–411.

- Underwood, E., Ashworth, R., Philip, R., Robert, G., Guthrie, Douglas, J., Thomson, W.

- Woodruff, H. B., Selman, A., Waksman, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80 (1), 2-8.

- Riedel, S., Proceedings (Baylor University, Medical Center), Vol. (18), 1, 2005, 21–25.

- Kirian, M., “Notifiable disease”, Encyclopedia Britannica, 21 June 2024, https://www.britannica.com/science/notifiable-disease. Accessed 6 August 2024.

- Serrano-Coll, H., Cardona-Castro, N., Journal of Wound Care. Vol 31 (6), 2022, S32–S40.

- Gordon, S. V., Parish, T., Microbiology, 164 (4), 2018, 437–439.

- Bates, B., Bargaining for Life, A Social History for Tuberculosis, 1876-1938. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992.

- Arlian, L., Annual Review of Entomology, 1989, 34, 139–61.

- McMichael, A.J., BMC Biology,2010, 8(108), 1-3.

- Murray R. L., Crane, J. S., Scabies. StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544306/.

- Steven, L., Percival, D., Williams, W., Microbiology of waterborne diseases: microbiological aspects and risks, 2nd edition, Academic Press, Boston, Massachusetts, London (England), 2014.

- Santacroce, L., Del Prete, R., Charitos, I. A., Bottalico L., Le Infezioni in Medicina, 2021, 29 (4), 623-632.

- Christensen, S. B., Molecules, 2021, 7:26(19), 6057.

- Gelmo, P., Journal of Practical Chemistry, 1908, 77, 369-382.

- Bennett, B. H., Parker, D. L., Robson, M., Public Health Reports, 2008, 123(2), 198-205.

- Barr, J., Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 2011, 66(4), 425-467.

- Pai, V.V., Rao, P.N., Agarwal, A.K., Darlong, J.,Kar, H.K., Narang, T.,Phiske, M.M., Jayashree, P.K., Reddy, S.A., Sarah, N., Chugh, R., Sunkara, G., Pathak, H., Borde, P.P., Kota, J., Modali, S., Indian Journal of Leprosy, 2023, 95, 293-297.

- Fenner, F., Henderson, D. A., Arita, I., Ježek, Z., Ladnyi, I. D., Smallpox and its eradication. History of International Public Health, Geneva, World Health Organization,1988, 6, 209–44.

- Wilson, P. K., “William Withering”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 22 April 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Withering. Accessed 6 August 2024.

- Granupas, European Medicines Agency, 2018, Accessed: 15/08/2024 at 3:25 pm.

- Sterling, T. R., Villarino, M. E., Borisov, A. S., Shang, N., Gordin, F., Bliven-Sizemore, E., The New England Journal of Medicine, 2011, 365 (23), 2155–66.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information, Retrieved September 24, 2024, from https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Pyrazinamide.

- Lee, N., Patel, P., Nguyen, H., In: StatPearls [Internet], StatPearls Publishing, 2024, Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559050/.

- Tröhler, U., Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 2007, 100(3),155-6.

- Winters, William L. “Cardiology”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 26 Apr. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/science/cardiology. Accessed 23 September 2024.

- Evans, C. H., Journal of Orthopedic Research, 2007, 25(4), 556-60.

- Carpenter K. J., Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2012, 61(3), 259-64.

- Sandhu, G. K., Journal of Global Infectious Diseases, 2011, 3 (2),143–50.

- O’Connor, C., Patel, P., Brady, M. F., Isoniazid. In: StatPearls [Internet], StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557617/.

- Flemming, A., British Medical Journal, 1952, 2(4778), 269-273.

- Maclagan, T., The Journal of Rheumatology, 1876, 1, 342–4.

- Flemming, A., British Journal of Experimental Pathology, 1929, 10, 226–36.

- American Chemical Society, Discovery and Development of penicillin, http://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/flemingpenicillin.html (accessed: 6 August 2024).

- Mushtaq, S, Abbasi B, H., Uzair, B., Abbasi, R., International Online Journal for Advances in Sciences, 2018, 17, 420-425.

- Loban, P.E., and Kaiser, A.D., Journal of Molecular Biology, 1973, 78, 453–471.

- Bolivar, F., Rodriguez, R.L., Greene, P.J., Betlach, M.C., Heyneke, H.L., Boyer, H.W., Gene, 1977, 2, 95–113.

- Novick, R.P., Clowes, R.C., Cohen, S.N., Curtiss, R., Datta, N., and Falkow, S., Bacteriological Reviews, 1976, 40, 168.

- Sikora, S., Hurley, B., and Tharakan, A. G., “Intelligent drug discovery: Powered by AI,” 2019.

- Mohs, R.C., Greig, N.H., Alzheimer and Dementia Journals, 2017, 11;3(4), 651-657.

- Wouters, O. J., McKee, M., Luyten, J., The Journal of the American Medical Association, 2020, 3;323(9), 844-853.

- Brown, D. G., Wobst, H. J., Kapoor, A., Kenna, L. A., Southall N., Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2022, 21(11), 793-794.

- Umscheid, C. A., Mitchell, M.D., Doshi, J.A., Agarwal, R., Williams, K., Brennan, P. J., Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 2011, 32(2),101-14.

- Lombardino, J. G., Lowe III, J. A., Nature Reviews, Drug Discovery, 2004, 3, 853-862.

- Markan, U., Pasupuleti, S., Pollard, C.M., Perez, A., Aukszi, B., Lymperopoulos, A., Therapeutic Advances in Cardiovascular Diseases, 2019, 13(6), 1-7.

- Drug Bank, “ATC Classification: C09.” [Online]. Available: https, Accessed: 26 July 2024.

- Luu, K.T., Kraynov, E., Kuang B., Vicini P., Zhong W.Z., Journal of the American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists, 2013, 15, 551–558.

- Zong, W.Z., Zhou, S.F., International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2014,15, 20072–20078.

- Mohsen, S., Behrooz, A., Roza, D., Cognitive Robotics, 2023, 3, 54-70.

- Guan, L., Yang, H., Cai, Y., Sun, L., Di, P., Li, W., Liu, G., Tang, Y., Medicinal Chemistry Communications, 2018, 10(1), 148-157.

- Kufel, J., Bargieł-Łączek, K., Kocot, S., Koźlik, M., Bartnikowska, W., Janik, M., Czogalik, Ł., Dudek, P., Magiera, M., Lis, A., Paszkiewicz, I., Nawrat, Z., Cebula, M., Gruszczyńska, K., Diagnostics (Basel), 2023,3:13(15), 2582.

- Singh, R.J., Lebeda, A., Tucker O., Chapter 2, Medicinal plants—nature’s pharmacy, Medicinal plants, Boca Raton, CRC Press, 2012, 13–51.

- Zeng, X., Wang, F., Luo, Y., Kang, S. G., Tang, J., Lightstone, F. C., Fang, E. F., Cornell, W., Zhang, X. C., Wu, C. K., Yi, J. C., Zeng, X. X., Yang, C. Q., Lu, A. P., Hou, T. J., Cao, D. S., Pushing the Boundaries of Molecular Property Prediction for Drug Discovery with Multitask Learning BERT Enhanced by SMILES Enumeration. Research, 2022.

- Engel, T., Journal of Chemical Informatics and Models, 2006, 46 (6), 2267–2277.

- Muegge, I., Mukherjee, P., Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery, 2016, 11(2), 137- 48.

- Agu, P. C., Afiukwa, C. A., Orji, O. U., Ezeh, E. M., Ofoke, I. H., Ogbu, C. O., Ugwuja, E. I., Aja, P. M., Scientific Reports, 2023, 17:13(1), 13398.

- Pang, Y. P., Kozikowski, A. P., Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design, 1994, 8(6), 669-81.

- Thipani Madhu M., Balaji, O., Kandi, V., Ca J., Harikrishna, G. V., Metta N, Mudamanchu, V. K., Sanjay, B. G., Bhupathiraju, P. A., A Narrative Review of Chondrocalcinosis, 2024,16(6), e63448.

- Guha R, Willighagen, E., Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry, 2012, 12(18), 1946-1956.

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., Stewart, L. A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A. C., Welch, V. A., Whiting, P., McKenzie, J. E., British Medical Journal, 2021, 29(372), 60.

- Russell, S. J., Norvig., P., Artificial Intelligence, A modern approach, 2021, 4th ed., Hoboken, Pearson.

- Bian, Y., (Sean) Xie, X.Q., “Computational Fragment-Based Drug Design: Current Trends, Strategies, and Applications,” American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists, 2018, (20) 59,1–11.

- Erlanson, D.A., McDowell, R.S., Brien, T.O., Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2004, (47)14,10–12.

- Vora, L. K., Gholap, A. D., Jetha, K., Thakur, R. R. S., Solanki, H. K., Chavda, V. P., Pharmaceutics, 2023, 10:15(7), 1916.

- Vamathevan, J., Clark, D., Czodrowski, P., Dunham, I., Ferran, E., Lee, G., Li, B., Madabhushi, A., Shah, P., Spitzer, M., Zhao, S., Nature Reviews: Drug Discovery, 2019, 18(6), 463-477.

- Feng, R., New Milestone in AI Drug Discovery, 2023, https://insilico.com/blog/first_phase2: Accessed August 2024.

- Liebman, M., Chemistry International, (44) (1), 2022, 16-19.

- Blanco-González, A., Cabezón, A., Seco-González, A., Conde-Torres, D., Antelo-Riveiro, P., Piñeiro, Á., Garcia-Fandino, R., Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2023, 18:16(6), 891.

- Hughes, J. P., Rees, S., Kalindjian, S. B., Philpott, K. L., British Journal of Pharmacology, 2011, 162(6), 1239-49.

- Han, R., Yoon, H., Kim, G., Lee, H., Lee, Y., Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2023, 6:16(9), 1259.

- Quazi, S., Medical Oncology, 2022, 15:39(8), 120.

- Zhavoronkov, A., Ivanenkov, Y. A., Aliper, A., Veselov, M. S., Aladinskiy, V. A., Aladinskaya, A. V., Terentiev, V. A., Polykovskiy, D. A., Kuznetsov, M. D., Asadulaev, A., Volkov, Y., Zholus, A., Shayakhmetov, R. R., Zhebrak, A., Minaeva, L. I., Zagribelnyy, B. A., Lee, L. H., Soll, R., Madge, D., Xing, L., Guo, T., Aspuru-Guzik, A., Nature Biotechnology, 2019, (9), 1038-1040.

- Dara, S., Dhamercherla, S., Jadav, S. S., Babu, C. M., Ahsan, M. J., Artificial Intelligence Reviews, 2022, 55(3), 1947-1999.

- Drews, J., Drug discovery, 2000, 287(5460), 1960-4.

- Hassija, V., Chamola, V., Mahapatra, A., Cognitive Computing, 2024, 16, 45–74.

- Seema, Y., Abhishek, S., Rishika, S., Jagat, P. Y., Intelligent Pharmacy, 2024, 2(3), 367-380.

- Feng, R., New Milestone in AI Drug Discovery, 2023, https://insilico.com/blog/first_phase2: Accessed August 2024.

- Balfour, H., DSP-1181: drug created using AI enters clinical trials. European Pharmaceutical Review – News on 4 February DSP-1181, 2020: drug created using AI enters clinical trials. europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com.

- Bess, A., Berglind, F., Mukhopadhyay, S., Brylinski, M., Griggs, N., Cho, T., Galliano, C., Wasan, K. M., Drug Discovery Today, 2022, 27(4), 1099-1107.

- Desai, D., Kantliwala, S. V., Vybhavi, J., Ravi, R., Patel, H., Patel, J., Review of AlphaFold 3, Cureus: Journal of Medical Science, 2024, 16(7), e63646.

- Shang, Z., Chauhan, V., Devi, K., Patil, S., Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 2024, 15(17), 4011-4022.

- Aiumtrakul, N., Thongprayoon, C., Suppadungsuk, S., Krisanapan, P., Miao, J., Qureshi, F., Cheungpasitporn, W., Journal of Personalized Medicine, 2023, 30:13(10),1457.

- Visan, A. I., Negut, I., Life (Basel), 2024, 7:14(2), 233.

| Aspect | Traditional Drug discovery | AI-enhanced drug discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Cost of production | It is quite slow since it involves many manual processes and trial and error. | Quite fast since most of the processes are automated, resulting in large amounts of data being processed quickly. |

| Reaction accuracy | Reactions are less accurate because they rely solely on humans Capabilities. |

It has the potential to increase reaction accuracy by accurately predicting reaction interactions. |

| Screening | Physical high-throughput screening takes longer and is expensive. | Virtual screening of millions of compounds in a short time time. |

| Lead Optimization | Requires manual labor and intensive effort optimization. | AI-driven algorithms optimize lead compounds more efficiently. |

| Innovation | Innovation is driven more by established scientific paradigms. | AI can identify novel drug candidates and mechanisms that humans cannot easily identify and observe. |

| Drug Repurposing | Drug repurposing is slower due to limited experimental evidence insights. | AI can identify existing drugs for new uses by analyzing large datasets. |

| Target Identification | Relies heavily on human hypotheses and experiment validation. | AI can quickly identify new drug targets using complex data patterns. |

| Personalization | Limited ability to tailor drugs to individual genetics profiles. | Can assist in developing personalized therapies based on patient’s data. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).