1. Introduction

The bimaxillary orthognathic surgeries, function and aesthetics are always associated. However, it has become evident that there are nasal changes in the postoperative period whenever the maxilla is positioned superiorly or advanced [

1]. With Lefort I osteotomy, there is a widening of the nasal base associated with the flattening and thinning of the upper lip. Depending on the patient's nasal anatomy, skin thickness, and soft tissue characteristics, other nasal changes such as those in the dorsum or tip may occur. The maxillary movement associated with dissection and detachment of the facial muscles at the anterior nasal spine and nasolabial region causes lateral muscle retraction and widening of the nasal base [

2].

The movement of the maxillary bone during orthognathic surgeries, such as linear advancement, anterior impaction, and posterior impaction, can produce modifications in the angulation and position of the nasal tip, as well as widening of the nasal base, thus affecting the shape of the nose after orthognathic surgery [

3]. These nasal changes can be expected whenever there are maxillary bone movements during the surgery. Regarding the nasal dorsum, nasal height, and nasal length, there are no significant changes in these regions; however, due to changes in the nasal tip angle, the nasal profile may become more concave after surgery [

4].

Knowing the nasal alterations that can occur during maxillary movement in orthognathic surgery, there are several ways we can improve the manipulation of the soft tissues in this region. The incision and subperiosteal dissection should be gentle and limited to the osteotomy performed for the necessary fixation of the maxilla. Suturing the alar base can neutralize nasal widening. In this suture, the fibroareolar tissue and the nasal muscle are identified and pulled down towards the midline to create a loop. Another commonly used suture to combat the adverse effects caused by Lefort I osteotomy in the nasolabial region is the V-Y closure, thus providing support to the soft tissues, volumizing and projecting the upper lip [

5].

Patients with dentofacial deformities who undergo orthognathic surgery report dissatisfaction regarding the aesthetics of their nose before surgery. In orthognathic surgeries with alar base closure and V-Y suture, there is a high satisfaction rate regarding postoperative nasal aesthetics [

6]. The suturing of the alar base shows effective and stable results in the nasal base widening produced by maxillary advancement. Intraoperative measurements show increases in the alar base of 8 to 10%, and when combined sutures with V-Y are performed, this increase is reduced by 53 to 58% from the initial measurement [

7].

To measure the soft tissue changes in the nasal region, computed tomography proves to be effective, especially in 3D reconstructions [

8]. Maxillary movement forward and upward causes changes in the nasal tip, alar base, and nostril areas, and these measurements can be easily obtained through 3D computed tomography [

9]. The effectiveness of 3D measurements allows us to explore various regions of the facial soft tissue, which can be performed in the short, medium, or long term and can be compared to each other or compared with changes in hard tissues, thereby producing endless ways of measuring and enhancing the understanding of facial changes after orthognathic surgery [

10].

Our study aims to evaluate whether there were significant alterations in nasal structure after orthognathic surgery, comparing them with the nasal measurements prior to the surgical procedure, and whether there was a relationship between the alteration of nasal structures and the amount of advancement of Lefort 1 osteotomy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Methodology

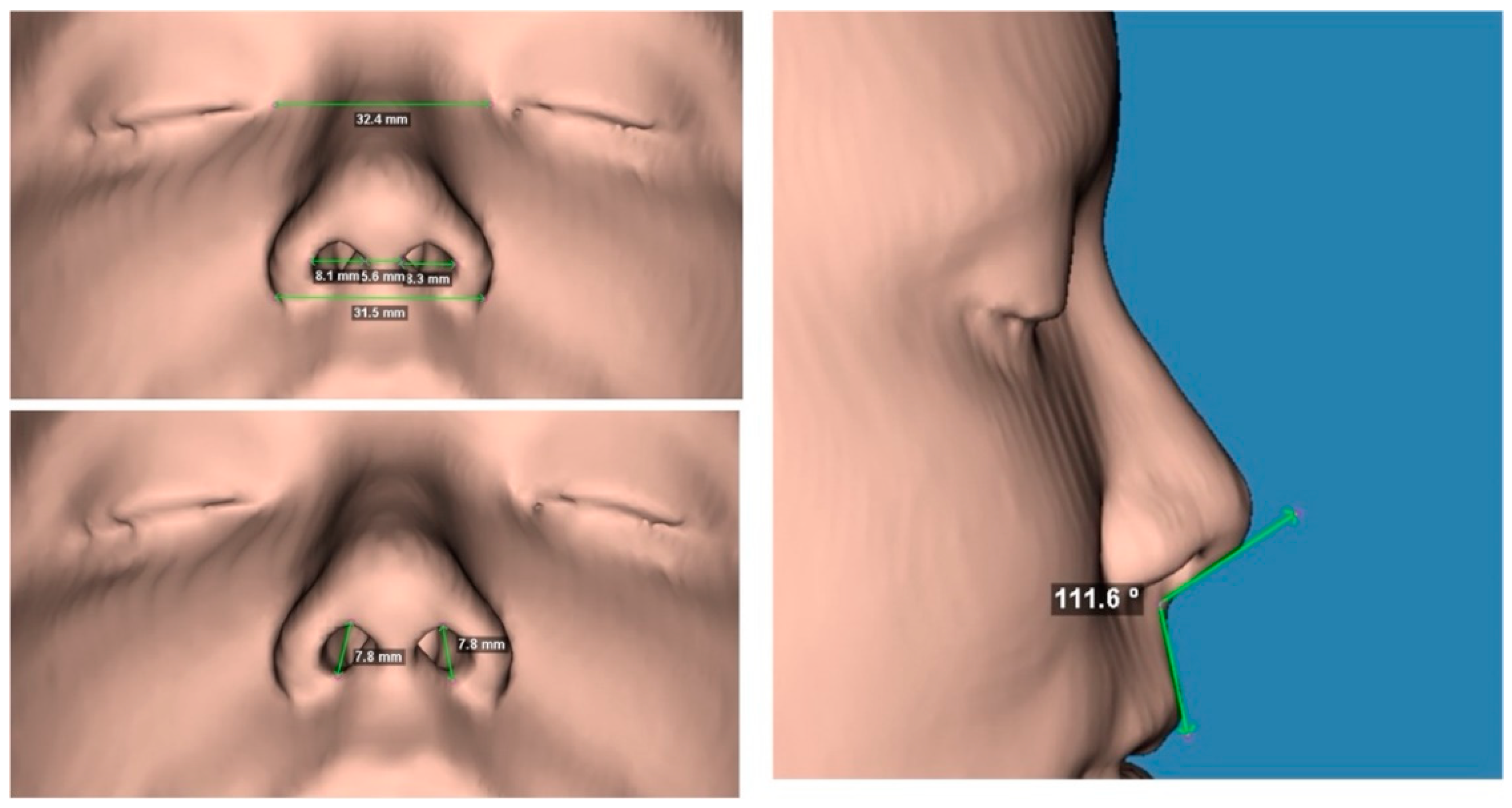

Computed tomography scans of 21 patients who underwent orthognathic surgery were used. These CT scans were performed prior to the surgical procedure (T1) and at least 6 months after orthognathic surgery (T2). The intercanthal distance, the alar width of the nose, the intercrural distance, the right and left nostrils (horizontal and vertical) and the nasolabial angle were measured. Maxillary advancement was measured in millimeters through the ANS (anterior nasal spine) point of the maxilla (

Figure 1).

Statistical analysis was conducted in three main stages: description of the sample variables, comparison between pre- and post-surgical moments, and evaluation of correlations between maxillary advancement, age, and facial measurements. All analyses were performed using the R software, version 4.3.2, considering a significance level α = 0.05. In the first stage, a descriptive analysis of the study variables was performed, including age, gender, maxillary advancement, and facial tomographic measurements. Measures of central tendency (mean and median) and dispersion (standard deviation, quartiles, minimum and maximum values) were calculated for all continuous variables. To investigate the impact of orthognathic surgery, a comparative analysis of facial measurements between pre- and post-surgical moments was conducted. For each variable measured before and after surgery, the normality of the distribution was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Based on this criterion, comparisons were performed using the paired Student's t-test for variables with normal distribution and the Wilcoxon test for paired samples when normality was not observed. The results were presented with measures of central tendency and dispersion for the two moments evaluated, accompanied by the respective p-values to determine the statistical significance of the differences found. The third stage consisted of the analysis of the correlation between maxillary advancement, age, and tomographic measurements. The normality of the distributions was evaluated for each variable, and the correlation method was chosen based on this criterion: Pearson's correlation coefficient was used for variables with normal distribution, while Spearman's coefficient was applied for variables without normal distribution. The correlation coefficients range from -1 to 1, where values close to -1 indicate a strong negative correlation, values close to 1 indicate a strong positive correlation, and values close to 0 indicate no significant correlation, suggesting that there is no clear linear or monotonic relationship between the variables analyzed. The analysis was conducted for the total sample and replicated separately in the groups of men and women, allowing the evaluation of possible differences in the correlations between the sexes. The results of these analyses were complemented by boxplot plots to illustrate the differences between the pre- and post-surgical time points and by scatter plots to explore the correlation between maxillary advancement and the difference in facial measurements that showed statistically significant relationship trends.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All patients undergoing orthognathic surgery with Lefort 1 osteotomy with linear advancement of at least 2 mm (ANS point).

The exclusion criteria used for our study were: previous orthognathic surgeries, cleft lip patients, rhinoplasty or injectable procedure, previous facial trauma, and local pathologies.

2.3. Surgical Technique

All patients were operated on by the same surgeon in different hospitals in the city of São Paulo. These surgeries were performed under general anesthesia and performed sequentially through the mandible, maxilla, and chin. Surgical access to the maxilla was performed with a cold scalpel between the canines and the entire periosteum and soft tissue was tunneled to the region of the maxilla tuber. LeFort 1 ostetomy performed in the maxilla was performed with an ultrasonic tip. The LeFort 1 osteotomy started at the piriform opening approximately 5 mm above the roots and proceeded to the posterior region of the maxillary tuber. A curved chisel was used to release the pterygopalatine pillar, thus achieving total maxillary mobilization. After repositioning and placing the final splint with maxillomandibular lock, we used 4 plates and screws for fixation. In suturing the alar base, after its identification and manipulation with Dietrich forceps, we used 2-0 monofilament nylon thread to close the alar base, pulling this base medially and downwards. This thread was sutured in a procedure performed in the anterior nasal spine. After suturing the alar base, we sutured the septum in position with 2-0 monofilament nylon thread and performed V-Y suturing of the soft tissues of the upper lip with 4-0 braided vicryl thread. Soon after, all the soft tissues of the maxilla were sutured with 4-0 braided vicryl sutures.

3. Results

The

Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample composed of 21 patients who underwent orthognathic surgery. Regarding gender, the distribution was balanced, with 52.4% of the participants being male and 47.6% female. The age of the patients ranged from 18 to 46 years, with a mean of 29.3 years (standard deviation of 8.5) and a median of 28 years. The mean mean surgical maxillary advancement was 4.9 mm (standard deviation of 1.2), with a median of 4.7 mm and a range between 3.1 and 7.2 mm.

The

Table 2 presents the results of the comparisons of the tomographic characteristics measured before and after orthognathic surgery. The variables evaluated included intercanthal, alar width, intercrural distances, nostril measurements (horizontal and vertical) and nasolabial angle. Among the measurements evaluated, the distance from the alar base showed a mean difference of 1.1 mm, with a p-value of 0.024, while the horizontal dimensions of the right and left nostrils had mean differences of 0.5 mm and 0.6 mm, respectively, with p-values of 0.029 and 0.034. In addition, the nasolabial angle showed a mean difference of 4.9 degrees, with a p-value of 0.007. The other variables, such as intercantal distance, intercrural distance, and vertical nostril dimensions, did not present statistically significant differences.

When interpreting these results, it is important to consider that paired statistical tests, such as the t-test and the Wilcoxon test, assess changes within everyone, being sensitive to small differences when data variability is low. In the present study, the low variability observed in variables such as distance from the alar base and horizontal dimensions of the nostrils contributed to the minimal changes being detected as statistically significant. However, statistically significant differences, such as those observed in the alar base (1.1 mm) and nostrils (0.5 to 0.6 mm), may be clinically irrelevant, as changes of this magnitude may not be perceptible or impactful aesthetically and functionally. On the other hand, the alteration observed in the nasolabial angle, of 4.9 degrees, may have greater clinical relevance, since changes in this parameter may be more aesthetically visible. In general, the results suggest that statistical significance should be analyzed with caution, especially in variables with small changes, prioritizing clinical evaluation to determine the practical relevance of the findings.

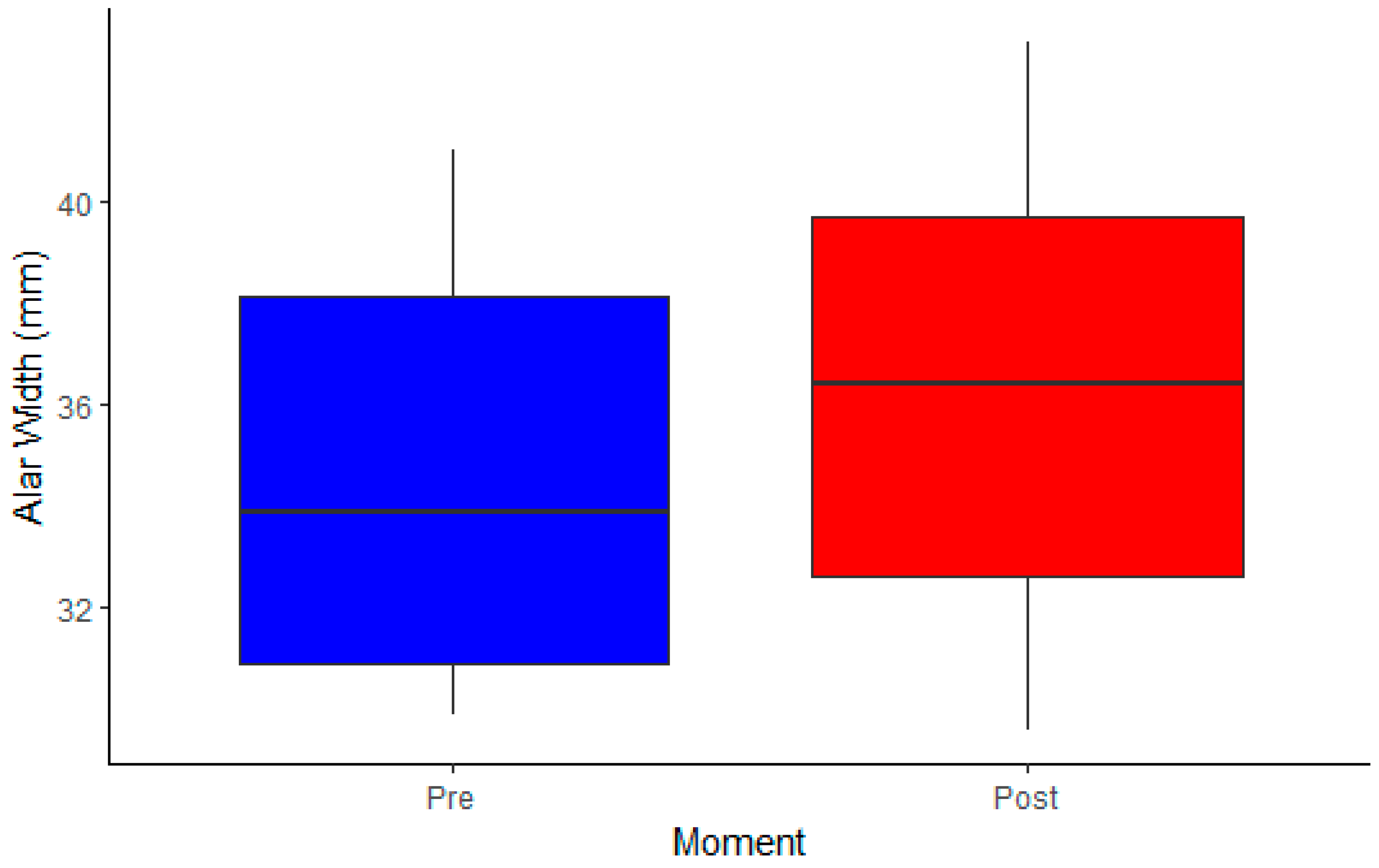

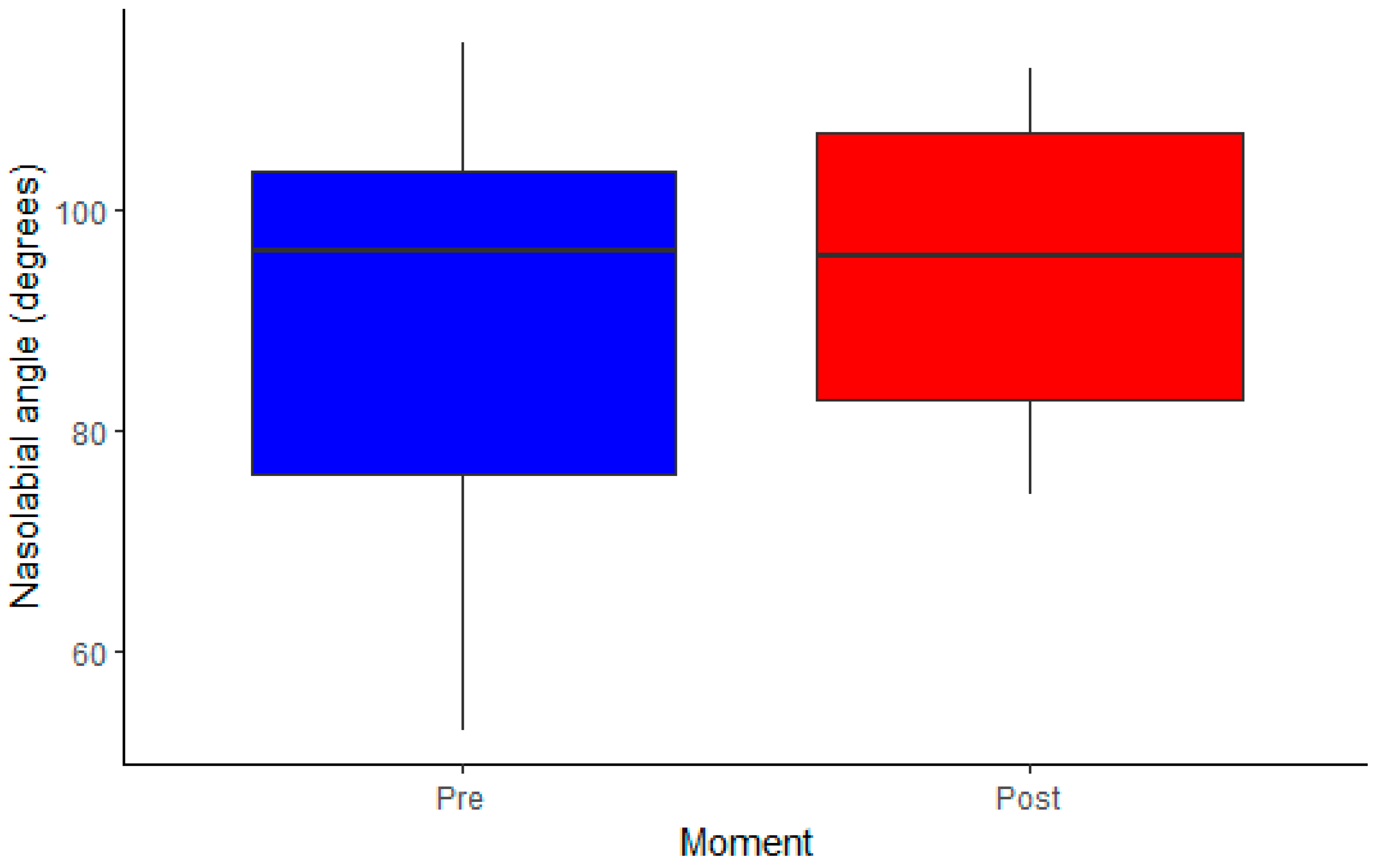

The following graphs illustrate the statistically significant differences observed in the tomographic measurements before and after orthognathic surgery. Each boxplot represents the distribution of the pre- and post-surgery values for the variables analyzed, allowing a visualization of the medians, dispersions, and possible outliers. As the data is paired, the graphs help to identify trends of variation for each of the measures evaluated.

The first graph (

Figure 2) shows a slight upward shift of the values at the post-surgery moment. The median of the alar width increased in relation to the preoperative period, which agrees with the statistical results that indicated a significant difference, although of small magnitude.

The second graph (

Figure 3) reveals a more evident increase in the median nasolabial angle after surgery, suggesting a more noticeable impact on this parameter. Unlike the other variables, this change may have more evident aesthetic implications.

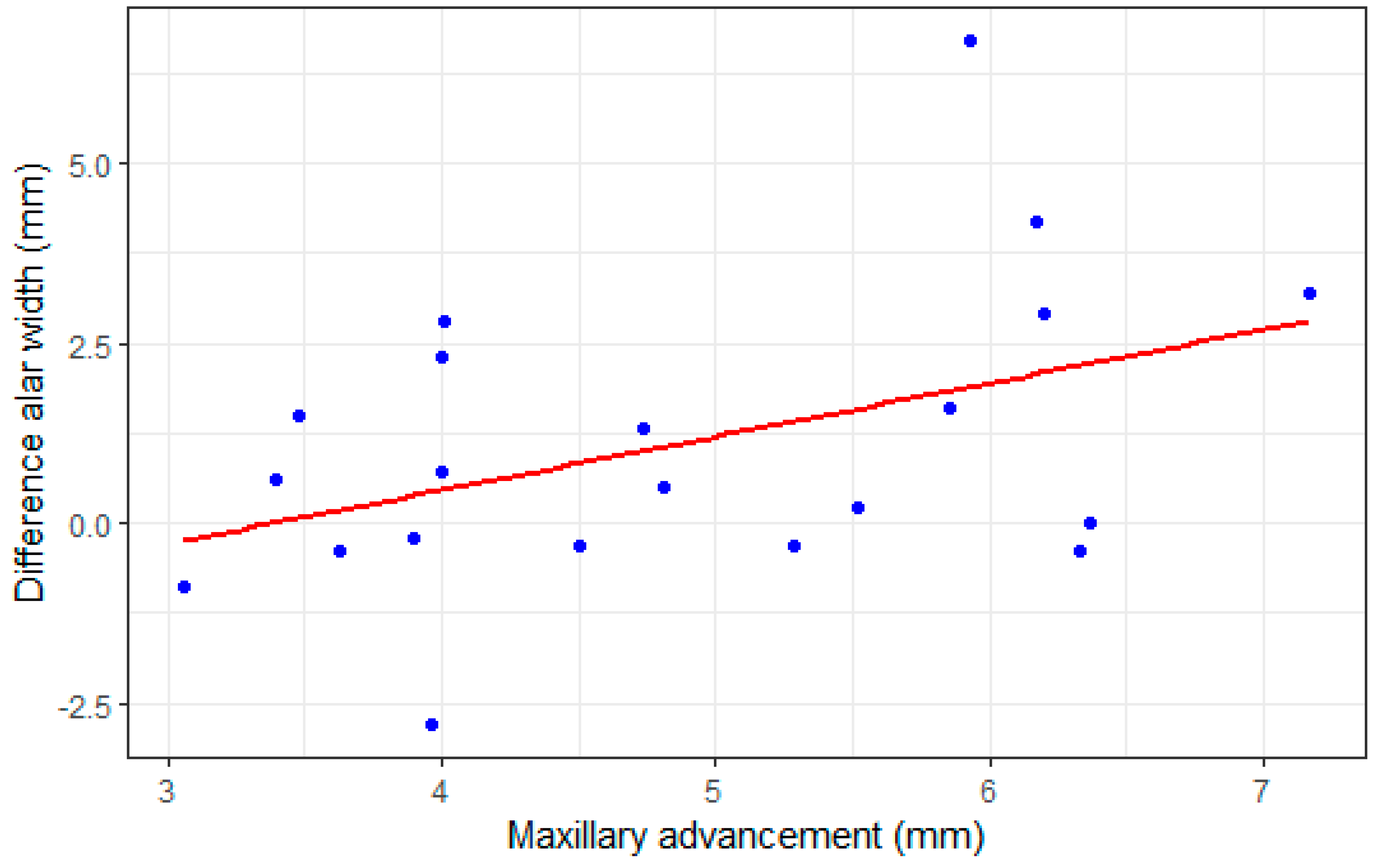

The correlation matrix (

Table 3) below shows the correlation between the surgical maxillary advancement and the tomographic measurements analyzed, considering the total sample of the study. The main objective of this analysis is to investigate whether maxillary advancement was a determining factor for the change in facial measurements, allowing us to understand the surgical impact on the structures evaluated. Among the correlations observed, the relationship between maxillary advancement and intercanthal distance, a measure of primary interest in the study, stands out. However, the correlation coefficients were low, suggesting a weak association between these variables. The second main variable, the nasolabial angle, also did not show a significant correlation with maxillary advancement, indicating that the increase in maxillary projection may not have been the preponderant factor for the changes in these measurements.

It is also observed that most of the associations were not statistically significant, suggesting that the variations in facial measurements after surgery were not directly related to the magnitude of maxillary advancement. One of the most relevant findings was the correlation between maxillary advancement and the difference in distance from the alar base, which presented a borderline p-value (p = 0.05), indicating a possible trend between surgical advancement and enlargement of this structure. To better explore this relationship, a scatter plot was generated, which allows us to visualize the distribution of the data and the direction of the association between the variables (

Figure 4).

The scatter plot (

Figure 4) presented below illustrates the relationship between maxillary advancement and the difference in distance from the alar width, allowing us to assess whether there is a linear pattern between these measurements. Each point represents an individual in the study, and the trend line suggests a slight positive association, indicating that patients with greater maxillary advancement may have experienced a proportionally greater increase in the alar width.

4. Discussion

Computed tomography scans have excellent accuracy for measurements on the face. With the aid of software, it is possible to measure both hard and soft tissues with excellent precision [

4,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. This allows us to have a better visualization in 3D, unlike radiographic and cephalometric exams, which allow us to only measure in a single plane [

3,

14] An alternative that has also been shown to be very effective is facial scanning, especially when there is a need to work with measurements only with the soft tissues of the face [

13,

20].

The augmentation of the Alar width is the main aesthetic complaint in the postoperative period of orthognathic surgery and there are numerous techniques that seek to improve the results. Rauso et al [

15] proposed a classification of alar width plication suture into four types (type 1: soft tissue plication; Type 2: soft tissue plication with cartilage anchorage; Type 3: soft tissue plication with bone anchorage; Type 4: anchorage of the soft tissue in the piriform opening without the plication of the alar base). There is also the possibility of using extraoral techniques that apparently can produce better results than intraoral techniques [

16,

17]. An alternative that has also been shown to be effective is to change the intubation from nasotracheal to orotracheal [

18] or to start orthognathic surgery with submental intubation [

19], thus leaving the nose free to be sutured symmetrically and proportionally.

When Lefort 1 osteotomies are performed, the result of our study is in accordance with the literature, maxillary advancement movements [

3,

4,

9,

10,

12,

13] produce significant changes in the enlargement of the alar base of the nose, even so the enlargement of the alar base may be related to maxillary intrusions [

4,

13], extrusions, transverse expansions [

12] and counterclockwise rotations [

12]. There is also a consensus in the literature on the need for closure of the alar base after Lefort 1 osteotomy [

4,

9,

11,

20], in a study [

20] comparing patients who underwent suturing of the alar width and the control group (without sutures), the results for those who underwent suturing are much superior to the control group. However, a study conducted by van Loon et al.(8) did not find a significant difference between patients who sutured the alar cinch and those who did not, going against the literature, leading some authors to the need to modify the suture technique with anchors [

21,

22,

23], extra-oral [

12,

16,

17] or associate the VY suture [

4,

24,

25,

26] of the upper lip. Our technique of anchoring the suture of the alar width to the anterior nasal spine allowed us to have good clinical results (1.1mm difference in the postoperative period), even though it was statistically significant.

Compared to other studies, our mean opening of the alar width was lower than in other studies [

11,

12,

16] even when using the Lefort 1 subspinal osteotomy [

6]. One possibility is minimally invasive maxillary access and less bone detachment. One of the limitations of this study is the follow-up in the n, final CT scans were requested at least 6 months after surgery. Long-term studies are needed to confirm these data. Our internal suture with lower traction and anchorage produced a significant but clinically acceptable opening of the alar base. Studies that performed extraoral sutures [

16,

17,

23,27] produced results closer to the measurements of the initial alar width.

The nasolabial angle had a significant increase, but it did not have a direct relationship with maxillary advancement, unlike another studies [

4,

24], which did not obtain a significant difference in the nasolabial angle and an even smaller change in the patients who did not have the alar base closed. With these data, we can understand that the repositioning of the soft tissues in the closure of the alar base produces changes in the nasolabial angle, totally in accordance with our data. The closure of the alar cinch associated with V-Y suture has been shown to be effective in stabilizing the soft tissues of the nasolabial region, supporting the nasal tip and maintaining the nasolabial angle [

25,

26].

The intercrural distance showed a significant increase in T2, and in direct relation to maxillary advancement. This relationship has already been noted in similar studies (9), but when we evaluate by sex, women showed a negative association where maxillary advancement led to a decrease in intercrural distance. The nostrils showed a statistically significant increase, but clinically imperceptible, not exceeding 2 mm, in line with other studies that endorsed changes in the nasal structure (9).

5. Conclusions

The nasal structures measured in orthognathic surgeries, the distance from the alar base, the nasolabial angle, and the horizontal dimensions of the right and left nostrils show statistically significant differences in the postoperative period.

Regarding maxillary advancement, there is a positive association, indicating that patients with greater maxillary advancement may have experienced a proportionally greater increase in the alar base.

Increased nasolabial angle is not associated with maxillary advancement.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conceptualization, methodology, data analysis, validation, drafting, review, editing, and final approval of this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines. It was approved by ethical committee of São Leopoldo Mandic University (number CAAE: 78722624.3.0000.5374; project number: 2289342).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Collins, P.C.; Epker, B.N. The alar base cinch: A technique for prevention of alar base flaring secondary to maxillary surgery. Oral Surgery, Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1982, 53, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schendel, S.A.; Carlotti, A.E. Nasal considerations in orthognathic surgery. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1991, 100, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, W.R.M.; da Silveira, M.M.F.; Vasconcelos, B.C.D.E.; Porto, G.G. Evaluation of the nasal shape after orthognathic surgery. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 81, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allar, M.L.; Movahed, R.; Wolford, L.M.; Oliver, D.R.; Harrison, S.D.; Thiesen, G.; Kim, K.B. Nasolabial Changes Following Double Jaw Surgery. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2019, 30, 2560–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Alfaro, F.; Valls-Ontañón, A. Aesthetic Considerations in Orthofacial Surgery. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. North Am. 2023, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, R.; Rezaie, P.; Sadeghi, H.M.; Malekigorji, M.; Dehghanpour, M. Patients Satisfaction and Nasal Morphologic Change after Orthognathic Surgery. World J. Plast. Surg. 2022, 11, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.; Edler, R. Efficacy and stability of the alar base cinch suture. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 49, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loon, B.; Verhamme, L.; Xi, T.; de Koning, M.; Bergé, S.; Maal, T. Three-dimensional evaluation of the alar cinch suture after Le Fort I osteotomy. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 45, 1309–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-B.; Yoon, J.-K.; Kim, Y.-I.; Hwang, D.-S.; Cho, B.-H.; Son, W.-S. The evaluation of the nasal morphologic changes after bimaxillary surgery in skeletal class III maloccusion by using the superimposition of cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) volumes. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2012, 40, e87–e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryckman, M.S.; Harrison, S.; Oliver, D.; Sander, C.; Boryor, A.A.; Hohmann, A.A.; Kilic, F.; Kim, K.B. Soft-tissue changes after maxillomandibular advancement surgery assessed with cone-beam computed tomography. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2010, 137, S86–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisiol, L.; Lanaro, L.; Favero, V.; Lonardi, F.; Vania, M.; D'Agostino, A. The effect of subspinal Le Fort I osteotomy and alar cinch suture on nasal widening. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2020, 48, 832–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A.P.d.S.; Guijarro-Martínez, R.; Haas, O.; Masià-Gridilla, J.; Valls-Ontañón, A.; de Oliveira, R.; Hernández-Alfaro, F. Nasolabial soft tissue effects of segmented and non-segmented Le Fort I osteotomy using a modified alar cinch technique—a cone beam computed tomography evaluation. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aihara, T.; Yazaki, M.; Okamoto, D.; Saito, S.; Suzuki, H.; Nogami, S.; Yamauchi, K. Changes in three-dimensional nasal morphology according to the direction of maxillary movement during Le Fort I osteotomy. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2024, 98, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauso, R.; Tartaro, G.; Tozzi, U.; Colella, G.M.; Santagata, M. Nasolabial Changes After Maxillary Advancement. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2011, 22, 809–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauso, R.; Tartaro, G.; Nicoletti, G.; Fragola, R.; Giudice, G.L.; Santagata, M. Alar cinch sutures in orthognathic surgery: scoping review and proposal of a classification. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 51, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, T.B.B.; Aires, C.C.G.; de Souza, R.R.L.; Gueiros, L.A.M.; Vasconcellos, R.J.d.H.; Leão, J.C. Comparison of two alar cinch base suture in orthognathic surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Braz. Dent. J. 2022, 33, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritto, F.G.; Medeiros, P.J.; de Moraes, M.; Ribeiro, D.P.B. Comparative analysis of two different alar base sutures after Le Fort I osteotomy: randomized double-blind controlled trial. Oral Surgery, Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 2011, 111, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, T.N.S.; Meka, S.; Ch, P.K.; Kolli, N.N.D.; Chakravarthi, P.S.; Kattimani, V.S.; L, K.P. Evaluation of modified nasal to oral endotracheal tube switch—For modified alar base cinching after maxillary orthognathic surgery. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2017, 7, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raithatha, R.; Naini, F.; Patel, S.; Sherriff, M.; Witherow, H. Long-term stability of limiting nasal alar base width changes with a cinch suture following Le Fort I osteotomy with submental intubation. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 46, 1372–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howley, C.; Ali, N.; Lee, R.; Cox, S. Use of the alar base cinch suture in Le Fort I osteotomy: is it effective? Br. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 49, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.; Kuo, C.; Liu, I.; Su, W.; Jiang, H.; Huang, I.; Liu, S.; Lee, S. Modified alar base cinch suture fixation at the bilateral lower border of the piriform rim after a maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 45, 1459–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, Z.S.; Susarla, S.M. Is the Pyriform Ligament Important for Alar Width Maintenance After Le Fort I Osteotomy? J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 73, S57–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Lin, C.-H.; Ko, E.-C. Effects of two alar base suture techniques suture techniques on nasolabial changes after bimaxillary orthognathic surgery in Taiwanese patients with class III malocclusions. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 44, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahsoub, R.; Naini, F.B.; Patel, S.; Wertheim, D.; Witherow, H. Nasolabial angle and nasal tip elevation changes in profile view following a Le Fort I osteotomy with or without the use of an alar base cinch suture: a long-term cohort study. Oral Surgery, Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2020, 130, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradin, M.; Rosenberg, A.; van der Bilt, A.; Stoelinga, P.; Koole, R. The effect of alar cinch sutures and V-Y closure on soft tissue dynamics after Le Fort I intrusion osteotomies. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2009, 37, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradin, M.S.; Seubring, K.; Stoelinga, P.J.; Bilt, A.V.; Koole, R.; Rosenberg, A.J. A Prospective Study on the Effect of Modified Alar Cinch Sutures and V-Y Closure Versus Simple Closing Sutures on Nasolabial Changes After Le Fort I Intrusion and Advancement Osteotomies. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).