Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology

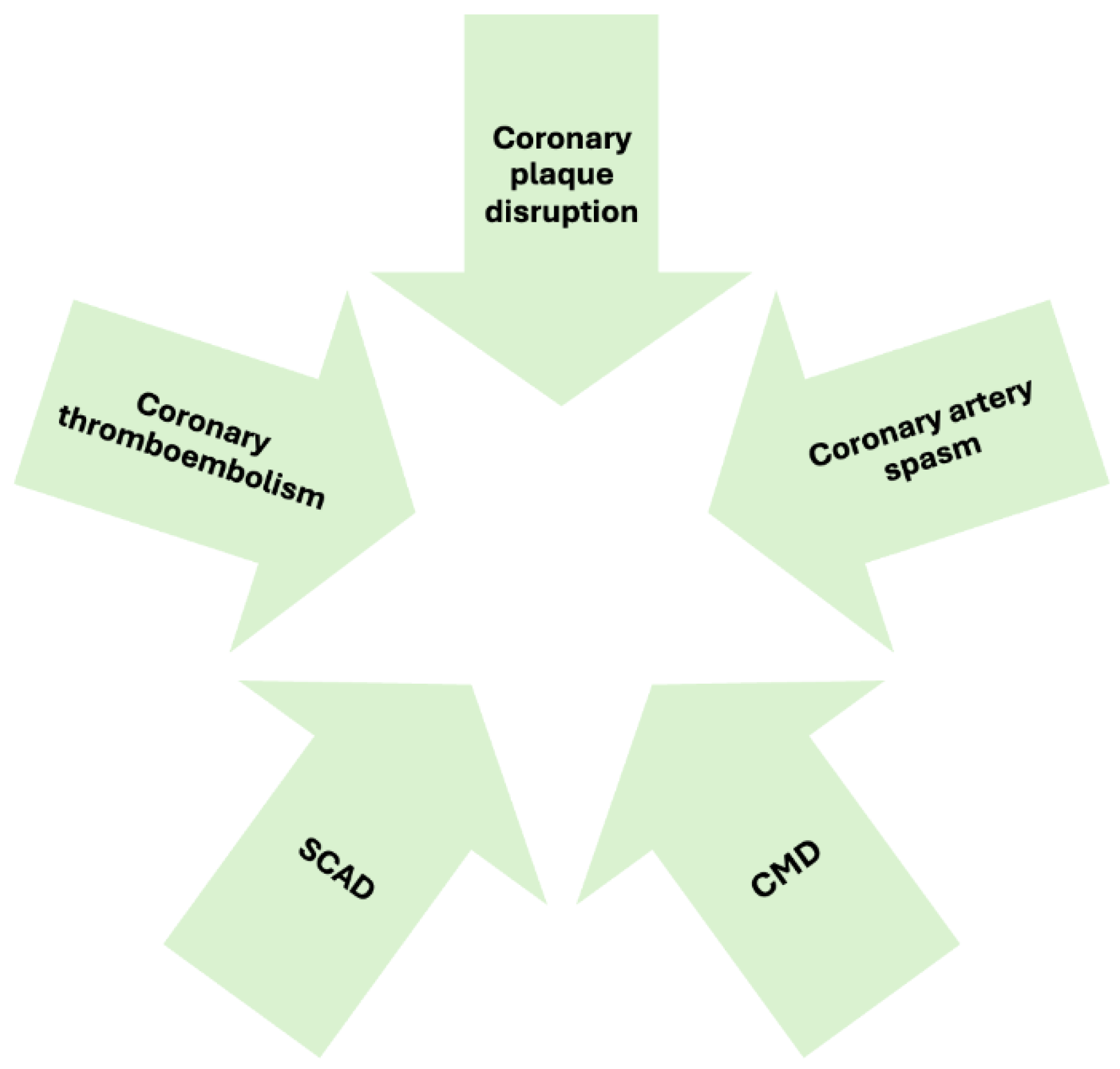

3. Pathophysiology

3.1. Atherosclerotic Causes of Myocardial Necrosis

- Coronary plaque disruption

3.2. Non-Atherosclerotic Causes of Myocardial Necrosis

- Coronary Artery Spasm

- Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction

- Coronary embolism and thrombosis

- Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection

3.3. Supply-Demand Mismatch

3.4. MINOCA Mimics

4. Clinical Presentation

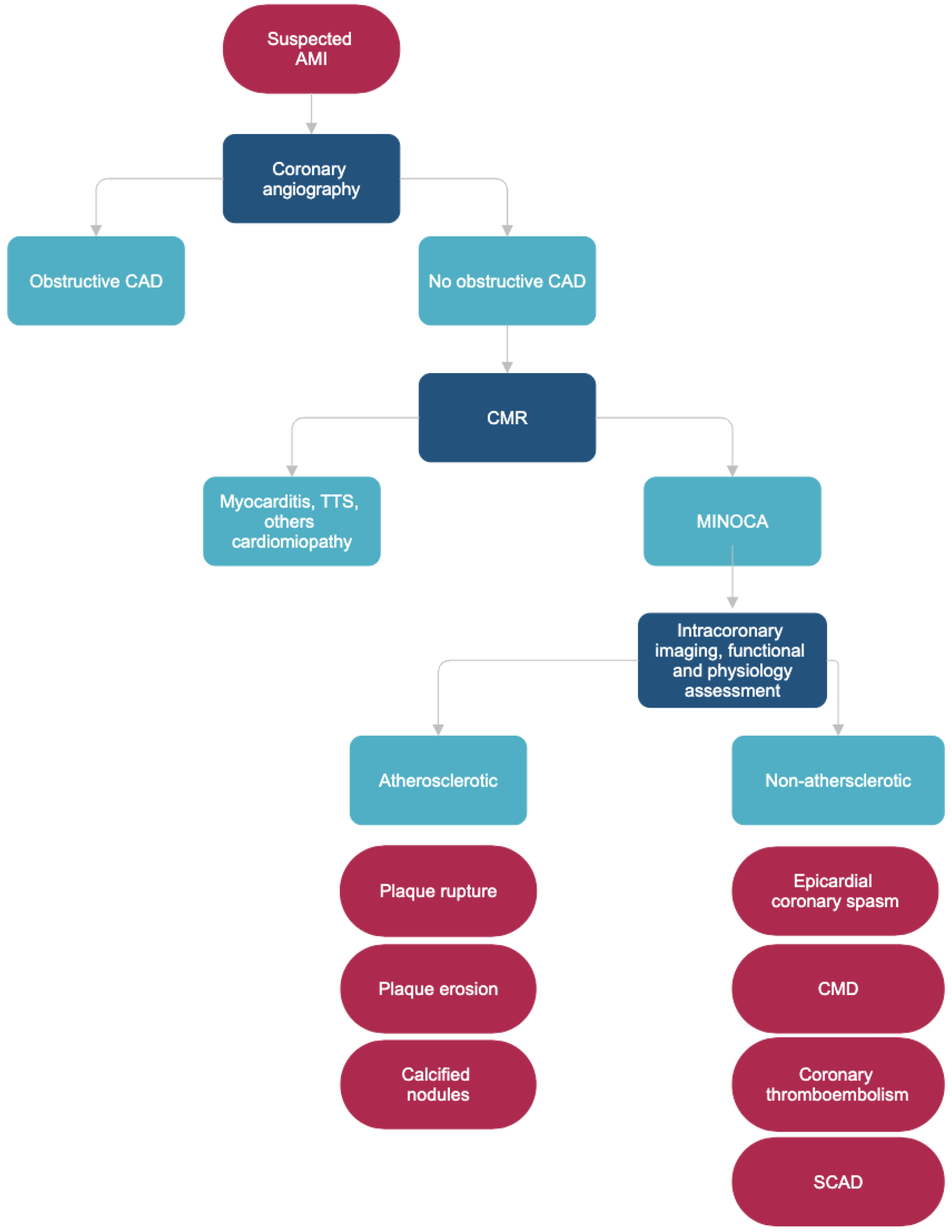

5. Diagnosis

- Intravascular imaging (OCT and IVUS)

- Intracoronary functional test (Ach, ergonovine)

- Coronary physiology assessment (FFR, CMR, IMR)

6. Management

7. Other Sex-Related Considerations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agewall S, Beltrame JF, Reynolds HR, Niessner A, Rosano G, Caforio ALP, et al. ESC working group position paper on myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries. Eur Heart J. 2017 Jan 14;38(3):143–53. [CrossRef]

- Tamis-Holland JE, Jneid H, Reynolds HR, Agewall S, Brilakis ES, Brown TM, Lerman A, Cushman M, Kumbhani DJ, Arslanian-Engoren C, Bolger AF, Beltrame JF; American Heart Association Interventional Cardiovascular Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Contemporary Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Myocardial Infarction in the Absence of Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019 Apr 30;139(18):e891-e908. [CrossRef]

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Circulation. 2018 Nov 13;138(20):e618–51. [CrossRef]

- Lindahl B, Baron T, Albertucci M, Prati F. Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention. 2021 Dec 3;17(11):e875-e887. Erratum in: EuroIntervention. 2022 Apr 01;17(17):e1366. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-21-0042C. [CrossRef]

- Boivin-Proulx LA, Haddad K, Lombardi M, Chong AY, Escaned J, Mukherjee S, et al. Pathophysiology of Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Contemporary Systematic Review. CJC Open. 2024 Feb;6(2Part B):380–90. [CrossRef]

- Pasupathy S, Air T, Dreyer RP, Tavella R, Beltrame JF. Systematic Review of Patients Presenting With Suspected Myocardial Infarction and Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries. Circulation. 2015 Mar 10;131(10):861–70. [CrossRef]

- Eggers KM, Hjort M, Baron T, Jernberg T, Nordenskjöld AM, Tornvall P, et al. Morbidity and cause-specific mortality in first-time myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries. J Intern Med. 2019;285(4):419–28. [CrossRef]

- Ang SP, Chia JE, Krittanawong C, Lee K, Iglesias J, Misra K, et al. Sex Differences and Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries: A Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024 Aug 6;13(15):e035329. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco C, Luu J, Mehta PK, Wei J, Gulati M, Merz CNB. INOCA and MINOCA: Are Women’s Heart Centres the Answer to Understanding and Management of These Increasing Populations of Women (and Men)? Can J Cardiol. 2022 Oct;38(10):1611–4. [CrossRef]

- Cano-Castellote M, Afanador-Restrepo DF, González-Santamaría J, Rodríguez-López C, Castellote-Caballero Y, Hita-Contreras F, et al. Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Treatment of Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection in Peripartum Women. J Clin Med. 2022 Nov 10;11(22):6657. [CrossRef]

- Pelliccia F, Pasceri V, Niccoli G, Tanzilli G, Speciale G, Gaudio C, et al. Predictors of Mortality in Myocardial Infarction and Nonobstructed Coronary Arteries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression. Am J Med. 2020 Jan 1;133(1):73-83.e4. [CrossRef]

- Nordenskjöld AM, Lagerqvist B, Baron T, Jernberg T, Hadziosmanovic N, Reynolds HR, Tornvall P, Lindahl B. Reinfarction in Patients with Myocardial Infarction with Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA): Coronary Findings and Prognosis. Am J Med. 2019 Mar;132(3):335-346. [CrossRef]

- Hjort M, Lindahl B, Baron T, Jernberg T, Tornvall P, Eggers KM. Prognosis in relation to high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T levels in patients with myocardial infarction and non-obstructive coronary arteries. Am Heart J. 2018 Jun 1;200:60–6. [CrossRef]

- Pasupathy S, Lindahl B, Litwin P, Tavella R, Williams MJA, Air T, et al. Survival in Patients With Suspected Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis From the MINOCA Global Collaboration. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021 Nov;14(11):e007880. [CrossRef]

- Davies MJ. The pathophysiology of acute coronary syndromes. Heart. 2000 Mar 1;83(3):361–6. [CrossRef]

- White SJ, Newby AC, Johnson TW. Endothelial erosion of plaques as a substrate for coronary thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2018 Mar 20;115:509–19. [CrossRef]

- Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Kolodgie FD. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Apr 18;47(8 Suppl):C13-18. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds HR, Maehara A, Kwong RY, Sedlak T, Saw J, Smilowitz NR, et al. Coronary Optical Coherence Tomography and Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Determine Underlying Causes of Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries in Women. Circulation. 2021 Feb 16;143(7):624–40. [CrossRef]

- Opolski MP, Spiewak M, Marczak M, Debski A, Knaapen P, Schumacher SP, et al. Mechanisms of Myocardial Infarction in Patients With Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease: Results From the Optical Coherence Tomography Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019 Nov 1;12(11, Part 1):2210–21. [CrossRef]

- Gerbaud E, Arabucki F, Nivet H, Barbey C, Cetran L, Chassaing S, et al. OCT and CMR for the Diagnosis of Patients Presenting With MINOCA and Suspected Epicardial Causes. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 Dec 1;13(12):2619–31. [CrossRef]

- Beltrame JF, Crea F, Kaski JC, Ogawa H, Ong P, Sechtem U, et al. International standardization of diagnostic criteria for vasospastic angina. Eur Heart J. 2017 Sep 1;38(33):2565–8. [CrossRef]

- Montone RA, Niccoli G, Fracassi F, Russo M, Gurgoglione F, Cammà G, et al. Patients with acute myocardial infarction and non-obstructive coronary arteries: safety and prognostic relevance of invasive coronary provocative tests. Eur Heart J. 2018 Jan 7;39(2):91–8. [CrossRef]

- Woudstra J, Vink CEM, Schipaanboord DJM, Eringa EC, den Ruijter HM, Feenstra RGT, et al. Meta-analysis and systematic review of coronary vasospasm in ANOCA patients: Prevalence, clinical features and prognosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1129159. [CrossRef]

- Park JY, Choi SY, Rha SW, Choi BG, Noh YK, Kim YH. Sex Difference in Coronary Artery Spasm Tested by Intracoronary Acetylcholine Provocation Test in Patients with Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease. J Intervent Cardiol. 2022;2022:5289776. [CrossRef]

- Caralis DG, Deligonul U, Kern MJ, Cohen JD. Smoking is a risk factor for coronary spasm in young women. Circulation. 1992 Mar;85(3):905–9. [CrossRef]

- Scalone G, Niccoli G, Crea F. Editor’s Choice- Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of MINOCA: an update. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2019 Feb;8(1):54–62. [CrossRef]

- Ong P, Camici PG, Beltrame JF, Crea F, Shimokawa H, Sechtem U, et al. International standardization of diagnostic criteria for microvascular angina. Int J Cardiol. 2018 Jan 1;250:16–20. [CrossRef]

- Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, Amsterdam E, Bhatt DL, Birtcher KK, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368–454. [CrossRef]

- Del Buono MG, Montone RA, Camilli M, Carbone S, Narula J, Lavie CJ, et al. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction Across the Spectrum of Cardiovascular Diseases: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 Sep 28;78(13):1352–71. [CrossRef]

- Mauricio R, Srichai MB, Axel L, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR. Stress Cardiac MRI in Women With Myocardial Infarction and Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease. Clin Cardiol. 2016 Oct;39(10):596–602. [CrossRef]

- Wei J, Bakir M, Darounian N, Li Q, Landes S, Mehta PK, et al. Myocardial Scar Is Prevalent and Associated With Subclinical Myocardial Dysfunction in Women With Suspected Ischemia But No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: From the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation-Coronary Vascular Dysfunction Study. Circulation. 2018 Feb 20;137(8):874–6. [CrossRef]

- Crea F, Camici PG, Bairey Merz CN. Coronary microvascular dysfunction: an update. Eur Heart J. 2014 May;35(17):1101–11. [CrossRef]

- Godo S, Takahashi J, Yasuda S, Shimokawa H. Role of Inflammation in Coronary Epicardial and Microvascular Dysfunction. Eur Cardiol. 2021 Feb;16:e13. [CrossRef]

- Odaka Y, Takahashi J, Tsuburaya R, Nishimiya K, Hao K, Matsumoto Y, et al. Plasma concentration of serotonin is a novel biomarker for coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with suspected angina and unobstructive coronary arteries. Eur Heart J. 2017 Feb 14;38(7):489–96. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi J, Suda A, Nishimiya K, Godo S, Yasuda S, Shimokawa H. Pathophysiology and Diagnosis of Coronary Functional Abnormalities. Eur Cardiol. 2021 Feb;16:e30. [CrossRef]

- Raphael CE, Heit JA, Reeder GS, Bois MC, Maleszewski JJ, Tilbury RT, et al. Coronary Embolus: An Underappreciated Cause of Acute Coronary Syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018 Jan 22;11(2):172–80. [CrossRef]

- El Sabbagh A, Al-Hijji MA, Thaden JJ, Pislaru SV, Pislaru C, Pellikka PA, et al. Cardiac Myxoma: The Great Mimicker. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017 Feb;10(2):203–6. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Yang J, Chen W, Yang X, Liu Y, Cong X, et al. Acute myocardial infarction as the first sign of infective endocarditis: a case report. J Int Med Res. 2020 Dec;48(12):300060520980598. [CrossRef]

- Karameh M, Golomb M, Arad A, Kalmnovich G, Herzog E. Multi-Valvular Non-bacterial Thrombotic Endocarditis Causing Sequential Pulmonary Embolism, Myocardial Infarction, and Stroke: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus. 2022 Dec;14(12):e32261. [CrossRef]

- Talebi S, Jadhav P, Tamis-Holland JE. Myocardial Infarction in the Absence of Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease (MINOCA): a Review of the Present and Preview of the Future. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2021 Jul 6;23(9):49. [CrossRef]

- Pasupathy S, Rodgers S, Tavella R, McRae S, Beltrame JF. Risk of Thrombosis in Patients Presenting with Myocardial Infarction with Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA). TH Open Companion J Thromb Haemost. 2018 Apr;2(2):e167–72. [CrossRef]

- Shen YM, Nagalla S. Hypercoagulable Workup in Thrombotic Cardiovascular Diseases. Circulation. 2018 Jul 17;138(3):229–31. [CrossRef]

- Stepien K, Nowak K, Wypasek E, Zalewski J, Undas A. High prevalence of inherited thrombophilia and antiphospholipid syndrome in myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries: Comparison with cryptogenic stroke. Int J Cardiol. 2019 Sep 1;290:1–6. [CrossRef]

- Saw J, Starovoytov A, Aymong E, Inohara T, Alfadhel M, McAlister C, et al. Canadian Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection Cohort Study: 3-Year Outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Oct 25;80(17):1585–97. [CrossRef]

- García-Guimaraes M, Bastante T, Macaya F, Roura G, Sanz R, Barahona Alvarado JC, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection in Spain: clinical and angiographic characteristics, management, and in-hospital events. Rev Espanola Cardiol Engl Ed. 2021 Jan;74(1):15–23. [CrossRef]

- Lewey J, El Hajj SC, Hayes SN. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: New Insights into This Not-So-Rare Condition. Annu Rev Med. 2022 Jan 27;73:339–54. [CrossRef]

- Tweet MS, Hayes SN, Codsi E, Gulati R, Rose CH, Best PJM. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection Associated With Pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Jul 25;70(4):426–35. [CrossRef]

- Waterbury TM, Tweet MS, Hayes SN, Eleid MF, Bell MR, Lerman A, et al. Early Natural History of Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018 Sep;11(9):e006772. [CrossRef]

- Hayes SN, Tweet MS, Adlam D, Kim ESH, Gulati R, Price JE, et al. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Aug 25;76(8):961–84. [CrossRef]

- Alfonso F, Paulo M, Gonzalo N, Dutary J, Jimenez-Quevedo P, Lennie V, et al. Diagnosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection by optical coherence tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 Mar 20;59(12):1073–9. [CrossRef]

- La S, Beltrame J, Tavella R. Sex-specific and ethnicity-specific differences in MINOCA. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024 Mar;21(3):192–202. [CrossRef]

- Collste O, Sörensson P, Frick M, Agewall S, Daniel M, Henareh L, et al. Myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries is common and associated with normal findings on cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging: results from the Stockholm Myocardial Infarction with Normal Coronaries study. J Intern Med. 2013;273(2):189–96. [CrossRef]

- Dastidar AG, Baritussio A, De Garate E, Drobni Z, Biglino G, Singhal P, et al. Prognostic Role of CMR and Conventional Risk Factors in Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructed Coronary Arteries. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019 Oct 1;12(10):1973–82. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi M, Harden S, Abid N, Peebles C, Nicholas Z, Jones T, et al. Troponin-positive chest pain with unobstructed coronary arteries: definitive differential diagnosis using cardiac MRI. Br J Radiol. 2012 Aug 1;85(1016):e461–6. [CrossRef]

- Kramer CM, Barkhausen J, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Flamm SD, Kim RJ, Nagel E. Standardized cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) protocols: 2020 update. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2020 Jan 20;22(1):17. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira VM, Schulz-Menger J, Holmvang G, Kramer CM, Carbone I, Sechtem U, et al. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Nonischemic Myocardial Inflammation: Expert Recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Dec 18;72(24):3158–76. [CrossRef]

- Cundari G, Galea N, De Rubeis G, Frustaci A, Cilia F, Mancuso G, et al. Use of the new Lake Louise Criteria improves CMR detection of atypical forms of acute myocarditis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021 Apr 1;37(4):1395–404. [CrossRef]

- Lintingre PF, Nivet H, Clément-Guinaudeau S, Camaioni C, Sridi S, Corneloup O, et al. High-Resolution Late Gadolinium Enhancement Magnetic Resonance for the Diagnosis of Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructed Coronary Arteries. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 May 1;13(5):1135–48. [CrossRef]

- Dastidar AG, Rodrigues JCL, Johnson TW, De Garate E, Singhal P, Baritussio A, et al. Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructed Coronary Arteries: Impact of CMR Early After Presentation. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017 Oct 1;10(10, Part A):1204–6. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto MH, Maehara A, Song L, Matsumura M, Chin CY, Losquadro M, et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Assessment of Morphological Characteristics in Suspected Coronary Artery Disease, but Angiographically Nonobstructive Lesions. Cardiovasc Revascularization Med Mol Interv. 2019 Jun;20(6):475–9. [CrossRef]

- Usui E, Murai T, Kanaji Y, Hoshino M, Yamaguchi M, Hada M, et al. Clinical significance of concordance or discordance between fractional flow reserve and coronary flow reserve for coronary physiological indices, microvascular resistance, and prognosis after elective percutaneous coronary intervention. EuroIntervention J Eur Collab Work Group Interv Cardiol Eur Soc Cardiol. 2018 Sep 20;14(7):798–805. [CrossRef]

- Taruya A, Tanaka A, Nishiguchi T, Ozaki Y, Kashiwagi M, Yamano T, et al. Lesion characteristics and prognosis of acute coronary syndrome without angiographically significant coronary artery stenosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 Feb 1;21(2):202–9. [CrossRef]

- Mas-Lladó C, Maristany J, Gómez-Lara J, Pascual M, Alameda MDM, Gómez-Jaume A, et al. Optical Coherence Tomography for the Diagnosis of Exercise-Related Acute Cardiovascular Events and Inconclusive Coronary Angiography. J Intervent Cardiol. 2020;2020:8263923. [CrossRef]

- Zeng M, Zhao C, Bao X, Liu M, He L, Xu Y, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Prognosis of MINOCA Caused by Atherosclerotic and Nonatherosclerotic Mechanisms Assessed by OCT. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023 Apr;16(4):521–32. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri L, D’Errico A, Avallone C, Gentile D, Provenzale G, Guagliumi G, et al. Optical Coherence Tomography and Coronary Dissection: Precious Tool or Useless Surplus? Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:822998. [CrossRef]

- Vrints C, Andreotti F, Koskinas KC, Rossello X, Adamo M, Ainslie J, Banning AP, Budaj A, Buechel RR, Chiariello GA, Chieffo A, Christodorescu RM, Deaton C, Doenst T, Jones HW, Kunadian V, Mehilli J, Milojevic M, Piek JJ, Pugliese F, Rubboli A, Semb AG, Senior R, Ten Berg JM, Van Belle E, Van Craenenbroeck EM, Vidal-Perez R, Winther S; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2024 Sep 29;45(36):3415-3537. [CrossRef]

- Takagi Y, Yasuda S, Takahashi J, Tsunoda R, Ogata Y, Seki A, et al. Clinical implications of provocation tests for coronary artery spasm: safety, arrhythmic complications, and prognostic impact: Multicentre Registry Study of the Japanese Coronary Spasm Association. Eur Heart J. 2013 Jan 21;34(4):258–67. [CrossRef]

- Ong P, Athanasiadis A, Borgulya G, Vokshi I, Bastiaenen R, Kubik S, et al. Clinical usefulness, angiographic characteristics, and safety evaluation of intracoronary acetylcholine provocation testing among 921 consecutive white patients with unobstructed coronary arteries. Circulation. 2014 Apr 29;129(17):1723–30. [CrossRef]

- Curzen N, Rana O, Nicholas Z, Golledge P, Zaman A, Oldroyd K, et al. Does routine pressure wire assessment influence management strategy at coronary angiography for diagnosis of chest pain?: the RIPCORD study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014 Apr;7(2):248–55. [CrossRef]

- AlBadri A, Bairey Merz CN, Johnson BD, Wei J, Mehta PK, Cook-Wiens G, et al. Impact of Abnormal Coronary Reactivity on Long-Term Clinical Outcomes in Women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Feb 19;73(6):684–93. [CrossRef]

- Lindahl B, Baron T, Erlinge D, Hadziosmanovic N, Nordenskjöld A, Gard A, et al. Medical Therapy for Secondary Prevention and Long-Term Outcome in Patients With Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation. 2017 Apr 18;135(16):1481–9. [CrossRef]

- Kovach CP, Hebbe A, O’Donnell CI, Plomondon ME, Hess PL, Rahman A, et al. Comparison of Patients With Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease With Versus Without Myocardial Infarction (from the VA Clinical Assessment Reporting and Tracking [CART] Program). Am J Cardiol. 2021 May 1;146:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Abdu FA, Liu L, Mohammed AQ, Xu B, Yin G, Xu S, et al. Effect of Secondary Prevention Medication on the Prognosis in Patients With Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2020 Dec;76(6):678. [CrossRef]

- Ciliberti G, Verdoia M, Merlo M, Zilio F, Vatrano M, Bianco F, et al. Pharmacological therapy for the prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with myocardial infarction with non-obstructed coronary arteries (MINOCA): Insights from a multicentre national registry. Int J Cardiol. 2021 Mar 15;327:9–14. [CrossRef]

- Paolisso P, Bergamaschi L, Saturi G, D’Angelo EC, Magnani I, Toniolo S, et al. Secondary Prevention Medical Therapy and Outcomes in Patients With Myocardial Infarction With Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease. Front Pharmacol [Internet]. 2020 Jan 31 [cited 2025 Feb 7];10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2019.01606/full. [CrossRef]

- Eggers KM, Hadziosmanovic N, Baron T, Hambraeus K, Jernberg T, Nordenskjöld A, et al. Myocardial Infarction with Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries: The Importance of Achieving Secondary Prevention Targets. Am J Med. 2018 May 1;131(5):524-531.e6. [CrossRef]

- Chen ZM, Jiang LX, Chen YP, Xie JX, Pan HC, Peto R, et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45,852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2005 Nov 5;366(9497):1607–21. [CrossRef]

- Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001 Aug 16;345(7):494–502. [CrossRef]

- Prati F, Uemura S, Souteyrand G, Virmani R, Motreff P, Di Vito L, et al. OCT-Based Diagnosis and Management of STEMI Associated With Intact Fibrous Cap. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013 Mar 1;6(3):283–7. [CrossRef]

- Xing L, Yamamoto E, Sugiyama T, Jia H, Ma L, Hu S, et al. EROSION Study (Effective Anti-Thrombotic Therapy Without Stenting: Intravascular Optical Coherence Tomography–Based Management in Plaque Erosion). Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017 Dec;10(12):e005860. [CrossRef]

- Imola F, Mallus MT, Ramazzotti V, Manzoli A, Pappalardo A, Di Giorgio A, et al. Safety and feasibility of frequency domain optical coherence tomography to guide decision making in percutaneous coronary intervention. EuroIntervention J Eur Collab Work Group Interv Cardiol Eur Soc Cardiol. 2010 Nov;6(5):575–81. [CrossRef]

- Beltrame JF, Crea F, Kaski JC, Ogawa H, Ong P, Sechtem U, et al. The Who, What, Why, When, How and Where of Vasospastic Angina. Circ J Off J Jpn Circ Soc. 2016;80(2):289–98. [CrossRef]

- Beltrame JF, Crea F, Camici P. Advances in coronary microvascular dysfunction. Heart Lung Circ. 2009 Feb;18(1):19–27. [CrossRef]

- Lerman A, Burnett JC, Higano ST, McKinley LJ, Holmes DR. Long-term L-arginine supplementation improves small-vessel coronary endothelial function in humans. Circulation. 1998 Jun 2;97(21):2123–8. [CrossRef]

- Kurtoglu N, Akcay A, Dindar I. Usefulness of oral dipyridamole therapy for angiographic slow coronary artery flow. Am J Cardiol. 2001 Mar 15;87(6):777–9, A8. [CrossRef]

- Saha S, Ete T, Kapoor M, Jha PK, Megeji RD, Kavi G, et al. Effect of Ranolazine in Patients with Chest Pain and Normal Coronaries- A Hospital Based Study. J Clin Diagn Res JCDR. 2017 Apr;11(4):OC14–6. . [CrossRef]

- Kilic S, Aydın G, Çoner A, Doğan Y, Arican Özlük Ö, Çelik Y, et al. Prevalence and clinical profile of patients with myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries in Turkey (MINOCA-TR): A national multi-center, observational study. Anatol J Cardiol. 2020 Feb;23(3):176–82. [CrossRef]

- Suhrs HE, Michelsen MM, Prescott E. Treatment strategies in coronary microvascular dysfunction: A systematic review of interventional studies. Microcirc N Y N 1994. 2019 Apr;26(3):e12430. [CrossRef]

- Saw J, Aymong E, Sedlak T, Buller CE, Starovoytov A, Ricci D, et al. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014 Oct;7(5):645–55. [CrossRef]

- Nakashima T, Noguchi T, Haruta S, Yamamoto Y, Oshima S, Nakao K, et al. Prognostic impact of spontaneous coronary artery dissection in young female patients with acute myocardial infarction: A report from the Angina Pectoris–Myocardial Infarction Multicenter Investigators in Japan. Int J Cardiol. 2016 Mar 15;207:341–8. [CrossRef]

- Tweet MS, Hayes SN, Pitta SR, Simari RD, Lerman A, Lennon RJ, Gersh BJ, Khambatta S, Best PJ, Rihal CS, Gulati R. Clinical features, management, and prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Circulation. 2012 Jul 31;126(5):579-88. [CrossRef]

- Adlam D, Alfonso F, Maas A, Vrints C, Writing Committee. European Society of Cardiology, acute cardiovascular care association, SCAD study group: a position paper on spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Eur Heart J. 2018 Sep 21;39(36):3353–68. [CrossRef]

- Macaya F, Salinas P, Gonzalo N, Camacho-Freire S, Jackson R, Massot M, et al. Long-term follow-up of spontaneous coronary artery dissection treated with bioresorbable scaffolds [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 7]. Available from: https://eurointervention.pcronline.com/article/long-term-follow-up-of-spontaneous-coronary-artery-dissection-treated-with-bioresorbable-scaffolds.

- Alkhouli M, Cole M, Ling FS. Coronary artery fenestration prior to stenting in spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;88(1):E23–7. [CrossRef]

- Saw J, Mancini GBJ, Humphries KH. Contemporary Review on Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Jul 19;68(3):297–312. [CrossRef]

- Saha M, McDaniel JK, Zheng XL. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: pathogenesis, diagnosis and potential novel therapeutics. J Thromb Haemost JTH. 2017 Oct;15(10):1889–900. [CrossRef]

- Nordenskjöld AM, Agewall S, Atar D, Baron T, Beltrame J, Bergström O, et al. Randomized evaluation of beta blocker and ACE-inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker treatment in patients with myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA-BAT): Rationale and design. Am Heart J. 2021 Jan 1;231:96–104. [CrossRef]

- Bairey Merz CN, Andersen H, Sprague E, Burns A, Keida M, Walsh MN, et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs Regarding Cardiovascular Disease in Women: The Women’s Heart Alliance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Jul 11;70(2):123–32. [CrossRef]

- Mosca L, Hammond G, Mochari-Greenberger H, Towfighi A, Albert MA, American Heart Association Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke in Women and Special Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on High Bloo. Fifteen-year trends in awareness of heart disease in women: results of a 2012 American Heart Association national survey. Circulation. 2013 Mar 19;127(11):1254–63, e1-29. [CrossRef]

- Dhawan S, Bakir M, Jones E, Kilpatrick S, Merz CNB. Sex and gender medicine in physician clinical training: results of a large, single-center survey. Biol Sex Differ. 2016;7(Suppl 1):37. [CrossRef]

- Melloni C, Berger JS, Wang TY, Gunes F, Stebbins A, Pieper KS, et al. Representation of women in randomized clinical trials of cardiovascular disease prevention. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010 Mar;3(2):135–42. [CrossRef]

- Tweet MS, Gulati R, Aase LA, Hayes SN. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a disease-specific, social networking community-initiated study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011 Sep;86(9):845–50. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).