1. Introduction

Data science and machine learning models for high-dimensional data frequently employ feature selection methods [

8,

39]. Feature selection, also known as variable selection or variable subset selection, involves choosing a relevant subset of features for further analysis, such as in classification or regression models. Feature selection is motivated by several factors, including reducing computational training costs, preventing overfitting, eliminating irrelevant or redundant features, and simplifying models to enhance interpretability [

29,

47]. Interestingly, the pursuit of interpretability is closely linked to explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) [

1,

21]. Unfortunately, feature selection introduces an additional layer of complexity to the overall problem since finding the optimal feature set within the feature space is a challenging task.

Over the last decades, numerous feature selection methods have been introduced [

52,

56]. Importantly, several approaches that came recently into spotlight are exploiting a framework based on Shapely value [

48], spurred partly due to its success in explainable AI and interpretable machine learning [

25]. While the earliest use of Shapely value for feature selection dates back to 2007 [

13], recent studies introduced extended methods [

10,

60]. These studies show promising results but lack a more comprehensive analysis. In this paper, we aim to fill this gap by investigating the functionality of Shapely value for feature selection of two approaches: Shapley value feature selection (SHAP) [

34] and Interaction Shapely Value (ISV) [

11]. In order to gain comprehensive insights, we compare SHAP and ISV with well-established feature selection methods. In total, we compare 14 different feature selection methods (FSM) for 4 different datasets. The methods include 10 filtering approaches (Term Strength (TS) [

2], Mutual Information (MI) [

57], Joint Mutual Information (JMI) [

59], Maximum Relevance and Minimum Redundancy feature selection (mRMR) [

46],

(Chi-squared test) [

5], Term ReLatedness (TRL) [

6], Entropy-based Category Coverage Difference (ECCD) [

38], Linear Measure (LM) [

14], F-stat [

9,

19] and Class-based term frequency–inverse document frequency (c-TF-IDF) [

33] and 4 wrapper methods (Linear Forward Search (LFS) [

27], Predictive Permutation Feature Selection (PPFS) [

30], Shapley value-based feature selection (SHAP) [

34]) and Interaction Shapely Value (ISV) [

11].

In addition, our paper aims to enhance our general understanding of feature selection. Importantly, one needs to distinguish between theoretical considerations and practical realizations. While, ideally, an optimal feature selection method would be able to find the Markov blanket, i.e., a subset of features that carries all information providing causal relations among covariates [

24,

36,

45,

61], practically, this goal is very difficult to achieve. A reason therefor is that available data have always a finite sample size and may be corrupted by measurement errors. Furthermore, data may be incomplete by not including all relevant features. All of those issues may be present for a given dataset but usually we lack detailed information. To obtain insights about this and related problems, we include Predictive Permutation Feature Selection (PPFS) [

30] in our analysis that aims to estimate the Markov blanket. We study also the very popular approach called Maximum Relevance and Minimum Redundancy (mRMR) [

46]. While mRMR does not directly target conditional independence, it indirectly relates to it by encouraging the selection of features that exhibit minimal redundancy, which is conducive to the notion of conditional independence. In contrast, most other approaches we are studying, including SHAP and ISV, are more heuristic with respect to their underlying working mechanisms. Hence, a comparison between such different methods will allow to evaluate their practical functioning under different conditions.

This paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we review related work and specify our research questions. The next section discusses the methods and the data we use for the analysis. Then we present our numerical results. The paper finishes with a discussion and concluding remarks.

4. Results

In this section, we show numerical results for 14 feature selection methods and 4 datasets where the following subsections are structured according to the datasets. For all results, the baseline model shown in the figures corresponds to a classifier using all features. That means, the baseline model is a classifier without feature selection. The standard errors are estimated using a 5-fold cross-validation (CV).

4.1. Enron Spam Detection

For performing spam detection with text data from Enron, we use a Support Vector Machine (SVM) for a binary classification. That means each instance, corresponding to an email, is either classified as spam or non-spam email. The Enron dataset a very high-dimensional consisting of features.

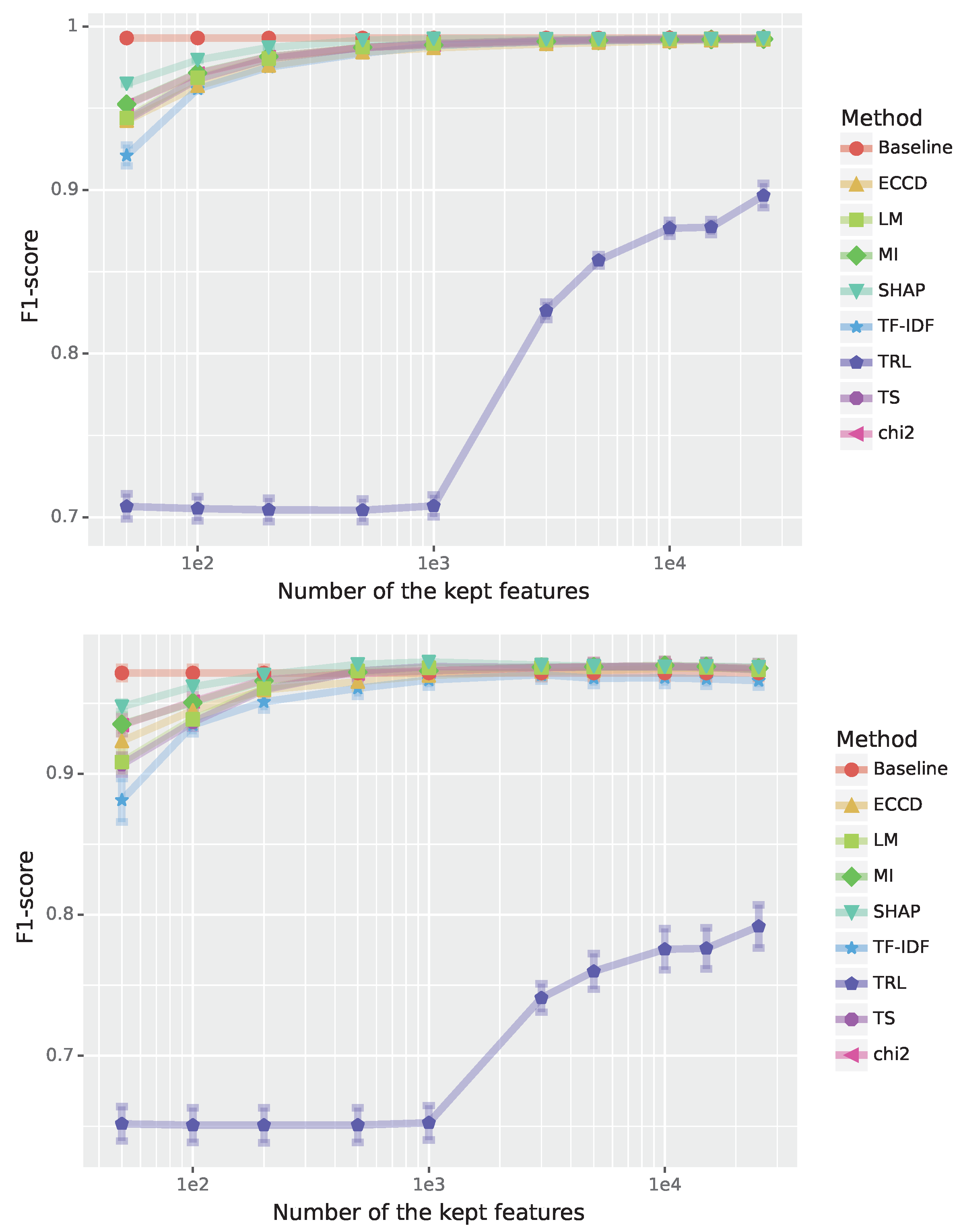

The results of the analysis are shown in

Figure 1 where the top figure shows results for the training data and the bottom figure for the test data. From this one can see that all feature selection methods except Term ReLatedness (TRL) converge around 3000 features. For the test data, the best performance is achieved for the Shapley value-based feature selection (SHAP) but other methods perform similarly well, including Term Strength (TS) and Mutual Information (MI). Interestingly, the baseline model that used all available features performs also very well.

In

Table 1, we show Jaccard scores between SHAP and the 7 feature selection methods from

Figure 1 for different numbers of features. As one can see, the highest observable overlap is 50.5% between SHAP and LM for 1000 features. Similar values are observed for TS, TF-IDF and

. In general, for small feature sets the overlap is higher than for large feature sets for all feature selection methods. For 3000 features, for smallest overlap is with TRL and ECCD. This is interesting because TRL performs very poorly (see

Figure 1) while the performance of ECCD is similar to SHAP. This indicates that a small overlap is no indicator of large performance changes between the feature selection methods but shows that there is a lot of redundancy in the features/words, so it is possible to pick different features while maintaining a high performance.

Table 2 shows the Jaccard scores between all tested methods for 3000 features/words, where the best performance was achieved. Overall, the overlap between TRL and all other methods is lowest followed by SHAP. Interestingly, all other methods have a higher overlap with each other. For instance, the overlap between LM and TS is 96.3% and between

and MI 89.5%. These are very high values considering the each of those feature selection methods is based on a different methodology.

We want to mention that Linear Forward Search (LFS) is not shown in this or any other analysis due to its slowness. Considering that it has to train models, where k is the number of features to be consider during each feature expansion and n is the total number of features/words, it is simply impractical to use it for such a highly dimensional dataset as Enron. It will severely underperform with small k and take too much time to select the optimal features subset with a sufficiently large k.

4.2. Brown Genre Classification

For the Brown data, we study a multiclass classification task with 15 classes corresponding to document genres. For this, we use a one-vs-rest classifier to deal with the multiclass classification. The reported -scores are macro averages over class labels and the error bars correspond to the standard errors (SE) from a cross validation. Also the Brown text dataset is very high-dimensional consisting of features/words.

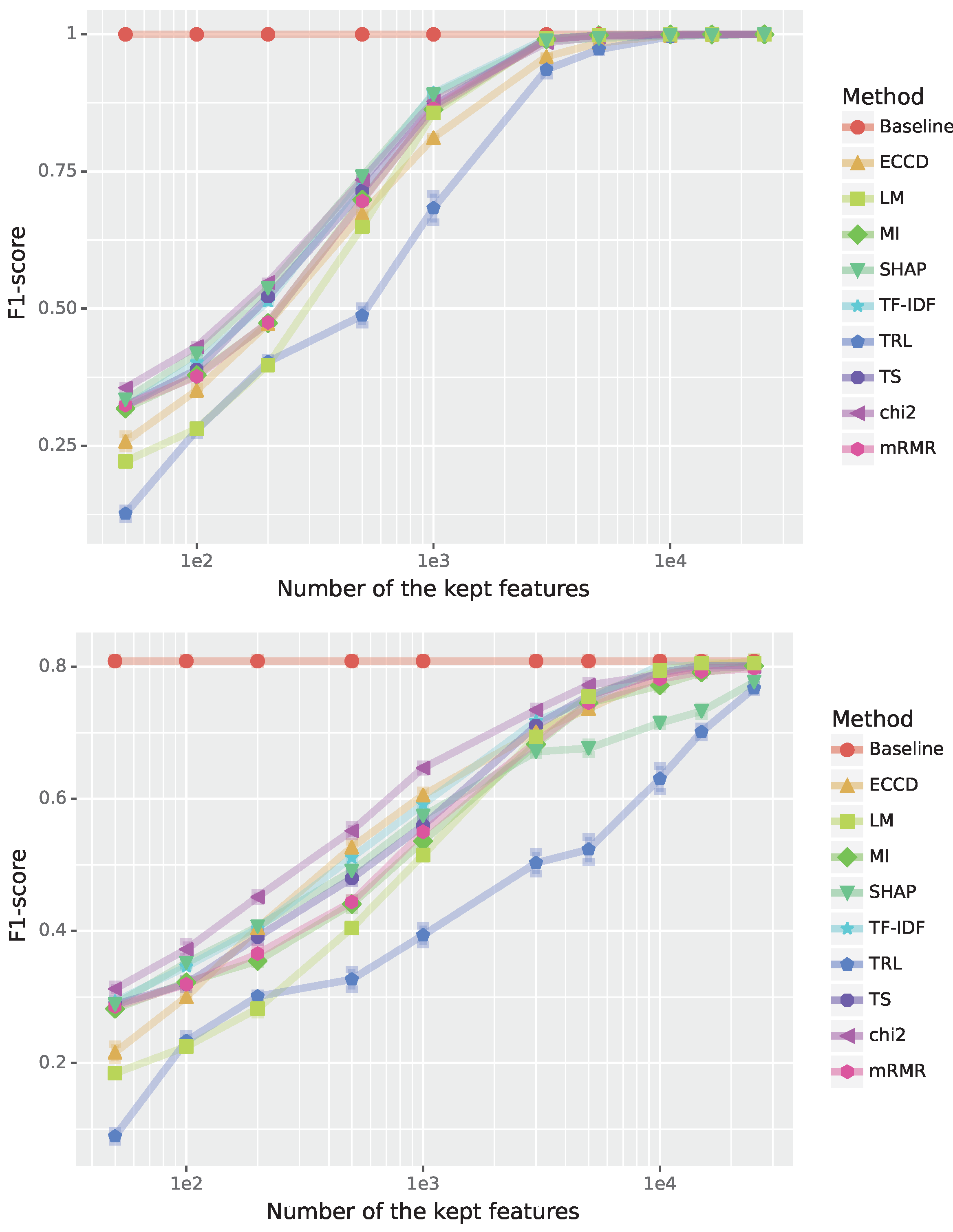

In general, multiclass classification is a much more difficult problem than binary classification. This can be seen when comparing the results in

Figure 2 with

Figure 1 (showing a binary classification) because the F1-scores for the test data are for all methods significantly reduced. TRL is still the worst performer, however, this time it does converge to the baseline, though much slower than all other feature selection methods. From

Figure 2 one can see that most of the feature selection methods obtain the best performance around 11000 features/words being only slightly worse than the baseline.

For the Brown data, the SHAP is no longer the best-performing method, but it still performs reasonably. Interestingly, mRMR is slightly better than SHAP but worse than the top performer which is a considerably simpler method. Overall, all feature selection methods are useful for this dataset but the number of features for obtaining a certain performance/F1-score differ greatly among the methods.

Next, we study again the composition of the selected feature sets with Jaccard scores and compare these for the different feature selection methods.

Table 3 shows the Jaccard scores between the 9 feature selection methods studied in

Figure 2. As one can see, the overlap between SHAP and all other methods is always higher than

and the largest similarity is to MI with

. In comparison to the Enron data, these similarities are much higher. Also the other feature selection methods have larger overlap similarities. It is likely that this is related to the total number of features which is for the Enron data

and

for the Brown data.

Feature removal: In addition to the above analysis, we study the effect removing the best features has on the classification performance. That means, we remove the best features and then finding the second best feature set by a feature selection method and this process is repeated iteratively. Hence, the number of available features is successively decreased and within those limited sets the best available features are selected. The results of this analysis are shown in

Figure 3. It is interesting to note that removing up to 200 features/words does not lead to much change for all feature selection methods. However, removing more features starts showing an effect. Most severely effected is mRMR which has a total breakdown when removing more than 1000 features. Next, TRL shows the second strangest effect but to a different extend. That means even removing 10000 features gives actually satisfying results for TRL. The remaining methods are even less effected indicating that they can still find good feature sets to compensate for the lost information contained in the removed features. Also these results are a reflection of the redundancy in the data allowing to compensate for the loss of “good” features. The fact that mRMR is most severely effect may be also related to the way it aims to estimate feature sets having a minimum redundancy. This could make mRMR more susceptible for the removal of “good” features.

4.3. Arcene Cancer Classification

The Arcene data provides information about mass-spectrometry measurements of ovarian and prostate cancer patients where the patients are either labeled as “cancer” or “normal”. This allows to perform a binary classification task.

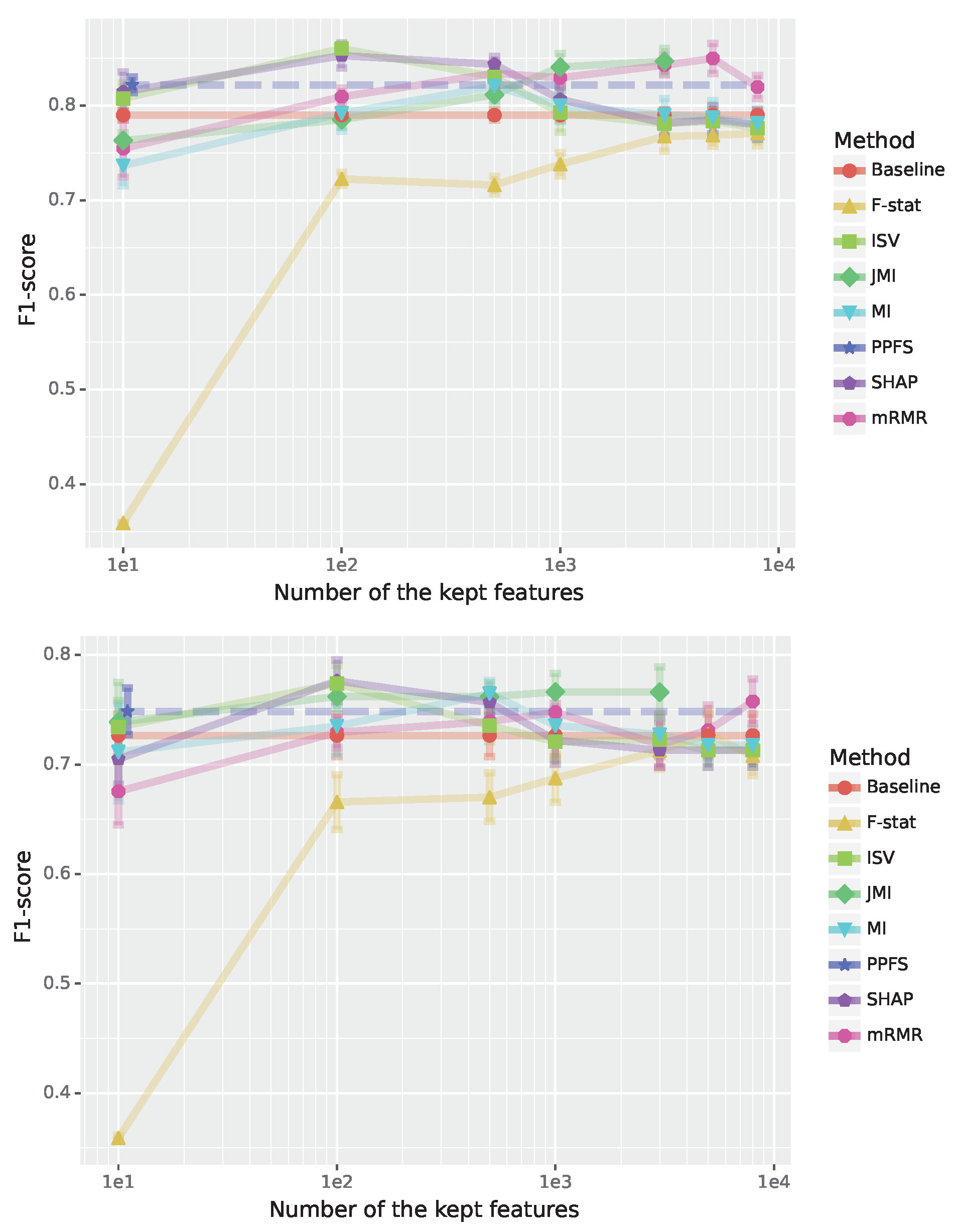

Results for the training and test sets are shown in

Figure 4. From this we see that all methods perform sufficiently well even with a small number of features (lef-hand-side) except F-stat. The F-test based feature selection needs at least 10 features to become competitive and about 300 features to perform similarly well as the other methods. Overall, the best performing methods are PPFS and SHAP followed by MI. One important point to note is that PPFS selects the optimal number of features by itself and for the Arcene data this is 12. For this reason, the results for PPFS are shown as a dashed horizontal line to distinguish it from the baseline. Interestingly, one needs at least a hundred features for the Shapley-values-based method to obtain a better performance than PPFS and PPFS’s performance is lagging behind the Shapley-values-based method for 100-500 selected features. The fact that SHAP, ISV, MI and mRMA are better than PPFS indicates that PPFS is not able to find the Markov Blanket.

In

Table 4, we show results for the Jaccard score between all feature selection methods for 100 features. One can see that the overlap between the different methods is quite low while the highest value is obtained for SHAP and ISV. However, also this similarity is only 9.9%. Considering that SHAP and ISV are both based on the Shapley value this indicates that the two approaches are quite different from each other. A similar behavior can be observed for MI and JMI with a similarity of 1.5% which is highest compared to all other methods but still quite low. Regarding the in general low similarity values, this is understandable considering the heterogeneity of the data consisting of a mixture of ovarian and prostate cancer patients and a combination of three datasets (see

Section 3.3.3). As a note, we would like to emphasize that this heterogeneity is also reflected in the increased standard errors one can see in

Figure 4 compared to he preceding results.

4.4. Ionosphere Radar Classification

Finally, we present results for the Ionosphere data containing 34 features from radar signals. Also for this dataset, we perform a binary classification. In total, we have 225 samples in class one and 126 samples in class two. We would like to highlight that in contrast to all previously studied dataset, the Ionosphere data are low-dimensional.

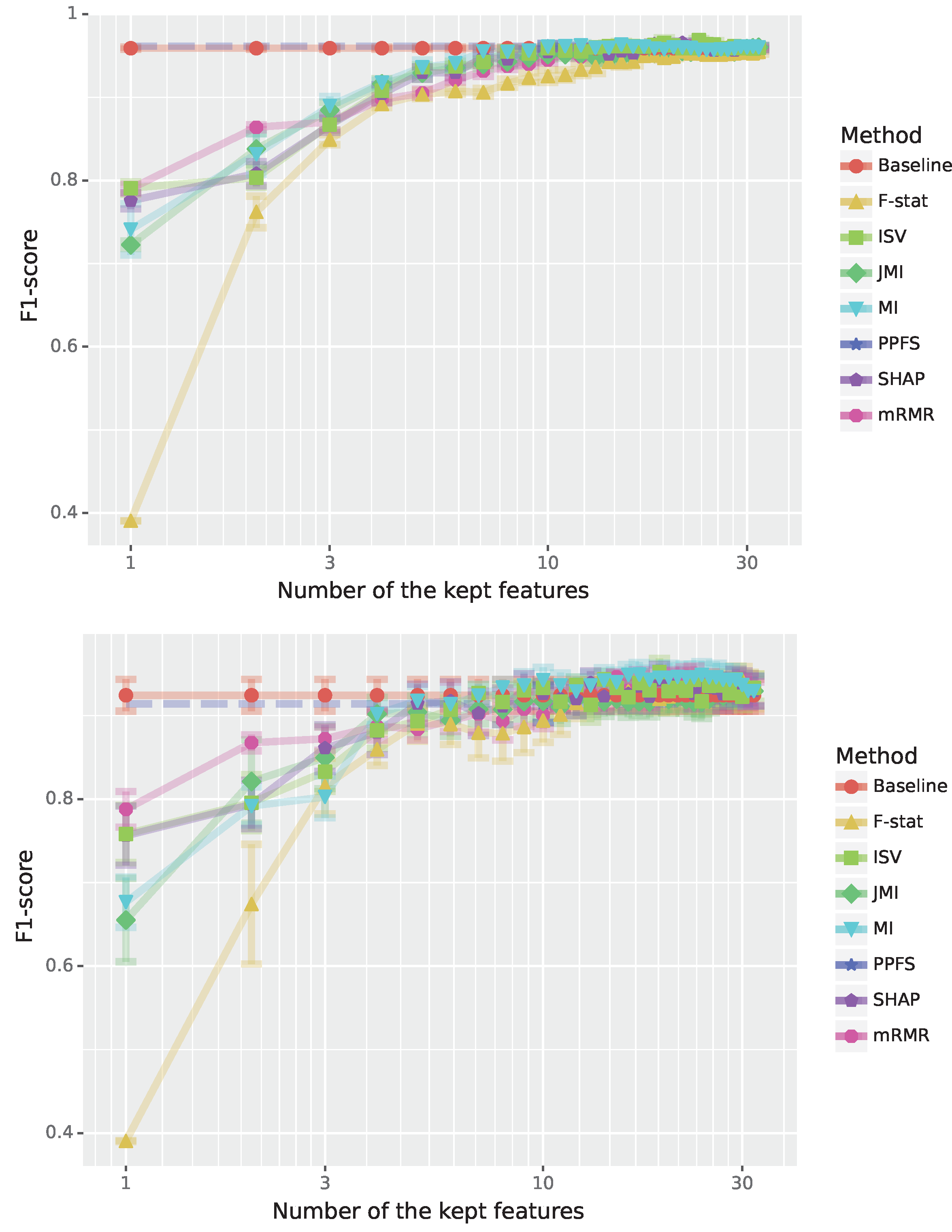

The results for the training and test data are shown in

Figure 5. First, we observe that the F1-scores for training and test data for all methods are quite similar indicating overall a good learning behavior of all methods. Second, F-stat shows a poor performance from the start but improves for larger feature sets and by using 12 features or more its performance is even comparable to all other methods. Third, most methods need about 10 features to reach saturation and further increasing the number of features has only a marginal effect. Still, it is surprising that even one feature results in respectable performance, especially for mRMR, SHAP and MI. Here it is important to note that the optimal number of features of PPFS is 10 features, shown as a straight blue line in

Figure 5. Interestingly, PPFS performs slightly worse than the baseline classifier using all features. Lastly, we would like the remark that mRMR, Mutual Information (MI) and Shapley-values-based approaches obtain a similar performance for

features and slightly improve over PPFS in performance after that on the test set.

In

Table 5, we show results for the Jaccard scores between all feature selection methods for 6 features. Compared to the results for the Arcene data in

Table 4, the similarity values are now significantly increased reaching

for (SHAP, ISM), (ISV, MI) and (mRMR, F-stat). However, one needs to place these similarity values into perspective because the number of features for the Ionosphere data is much smaller than for the Arcane data (the Arcene data contain 10000 features and the Ionosphere data only 34). Hence, for the Ionosphere data, it is easier to find overlapping feature sets by chance.

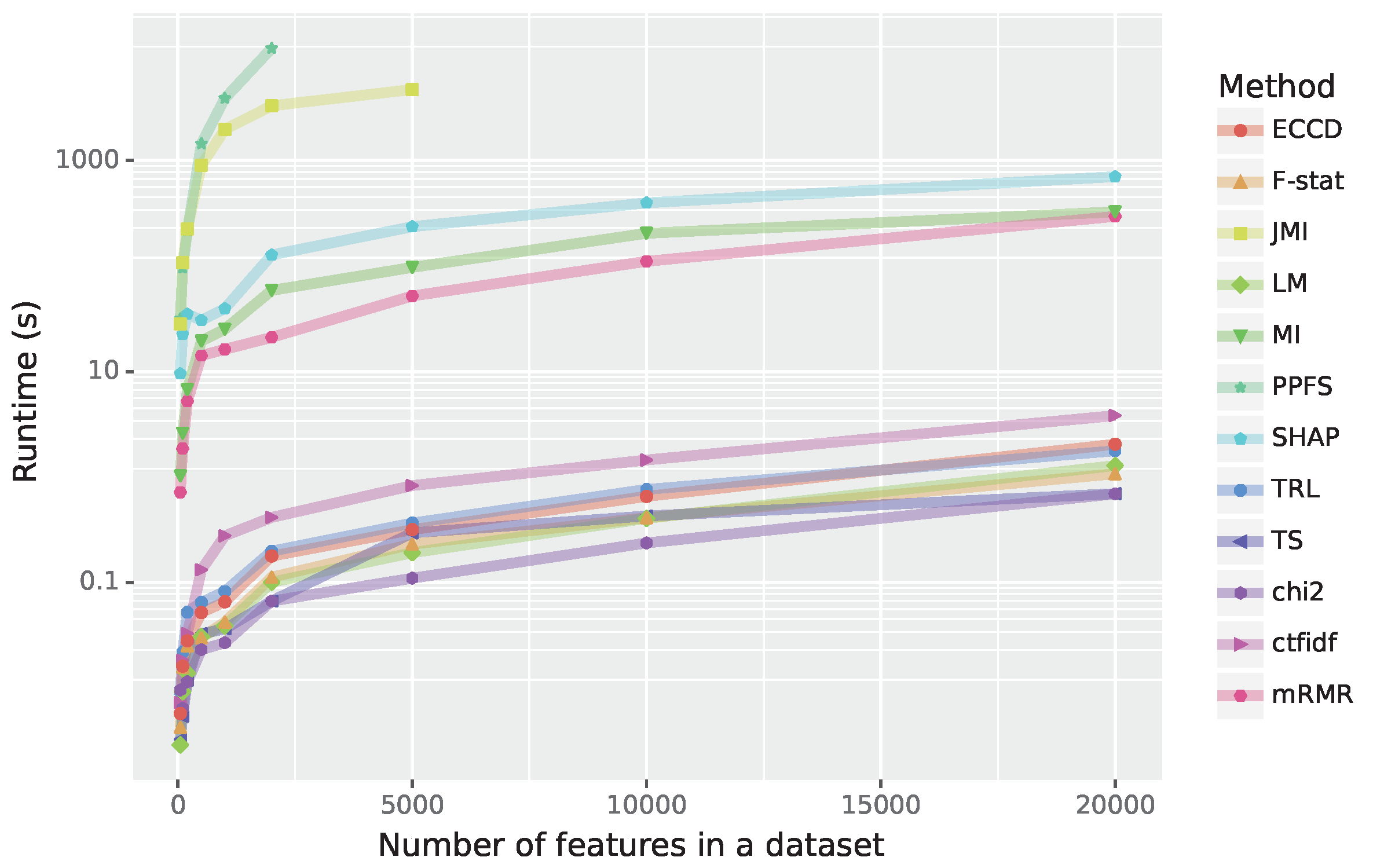

4.5. Runtime of the methods

In general, the time complexity of methods is one of the main limiting factors in feature selection. If not for the computational performance of the algorithms, it would be possible to simply check all the possible feature combinations to find the best. Therefore, to fully understand the benefits of the used methods their complexity has to be taken into account.

In this section, we compare the feature selection methods based on their runtimes depending on the number of features. For this analysis, for reasons of simplicity, we use simulated data with 5000 samples. The results are shown in

Figure 6. Overall, in this figure one can see three groups of methods. The group with the slowest methods includes PPFS and JMI and these methods become even prohibitive for more than 400 respectively 5000 features. The second group of methods includes SHAP, MI and mRMR. While this group is about 100 times faster than the first group, it is also 100 slower than group three whereas group three consists of cTFIDF, ECCD, TRL, LM, F-stat, JMI and

. To complement our numerical results, we show in

Table 6 the theoretical time complexity of all algorithms.

One interesting factor encountered with the runtime analysis is that not only the number of features matters but also other factors. As an example, while the LFS method scales linearly with the number of features, each iteration is extremely slow. Similar problems are also encountered for PPFS, ISV and JMI. On the other hand, mRMR and Term Strength are relatively fast despite being of order .

Another point to be considered is the implementation itself. Some of the algorithms were implemented professionally with efficient programming languages compared to some others. For example, we implemented the ISV method in python with numpy. Hence, some better and more optimized implementation could lead to a more efficient runtime.

5. Discussion

In recent years, Shapley values are frequently used in the context of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) for making otherwise black-box models more interpretable. However, their usage for feature selection is so far underexplored. For this reason in this paper, we study two Shapley-based feature selection approaches, SHAP and ISV, and compare them to 12 established feature selection methods: Term Strength (TS), Mutual Information (MI), Joint Mutual Information (JMI), Maximum Relevance and Minimum Redundancy (mRMR), (chi2), Term ReLatedness (TRL), Entropy-based Category Coverage Difference (ECCD), Linear measure-based (LM), F-test (F-stat), Class-based Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (c-TF-IDF), Linear Forward Search (LFS) and Predictive Permutation Feature Selection (PPFS). Of these approaches, 10 are filtering methods and 4 are wrapper methods. In order to obtain robust results, we study 4 different datasets (Enron, Brown, Arcene and Ionosphere) to cover a wide range of information regarding the functioning of these methods.

From our analysis, we obtain a number of different results. These finding can be summarized as follows.

Shapley-based feature selection is a competitive feature selection method.

There is not one feature selection method that dominates all others.

Simple/fast feature selection methods do not necessarily perform poor.

Feature selection is not always beneficial to improve prediction performance.

Using all features gives a fast and good approximation of the optimal prediction performance.

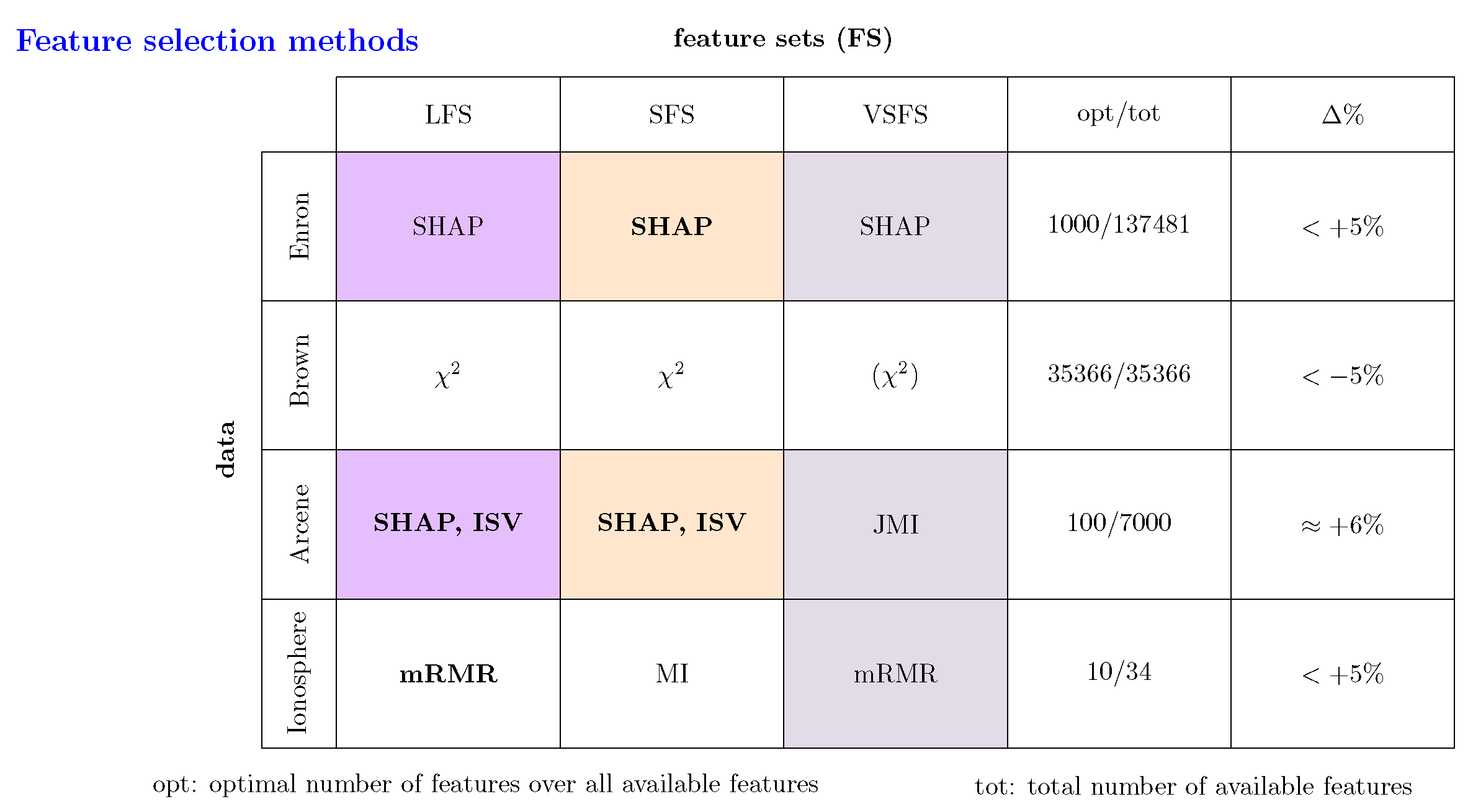

To 1: From our results about the four different datasets, we can see that SHAP is a feature selection method that gives competitive results compared to well-established methods from the literature; see

Figure 1 to

Figure 5. In

Figure 7, we summarize these results by providing information about the best performing feature selection methods. Here we distinguish between three different types of feature sets: LFS (large feature sets), SFS (small feature sets) and VSFS (very small feature sets). Specifically, for LFS we allow to select the method for all studied sizes of feature sets. For instance, for the Arcene data this corresponds to the interval

. For SFS we allow set sizes up to

of LFS and for VSFS we allow set sizes up to

of LFS. As one can see from

Figure 7, SHAP is the best performing method for the Enron and Arcene data but not for the Brown and Ionosphere data. Still, also for those data, SHAP gives reasonable results, especially for the Ionosphere data.

To 2: An immediate consequence of the above observations is that there is no feature selection method that dominates all others over all datasets. This is of course related to the heterogeneity of data sources because we studied two text datasets (Enron and Brown), one dataset from mass-spectrometry (Arcene) and one dataset from radar systems (Ionosphere). These data provide quite different information about different phenomena. Also the dimensionality of the four dataset is very different. While the Enron and Brown data are high-dimensional, having and features respectively, the Ionosphere data is low-dimensional with 34 features and the Arcene data is situated in between with 10000 features. All these factors influence the selection behavior of a feature selection method and as one can see from our results there is no method that performs optimally under all conditions.

To 3: From the presentation of the methods (see

Section 3) and their runtime analysis (see

Figure 6) one can see that some of the methods are quite complex and others have a high computational complexity. Surprisingly, neither is an indicator for a feature selection method to perform well. Instead, we found that

a method that is a fast and rather simple performs quite well in general without being the top performer. Also F-stat gives reasonable results, if one uses large feature sets. In contrast, a complex and rather slow method like mRMR performs by far not as good as expected, considering it’s widespread usage and popularity.

To 4: In order to be able to quantify the benefit of a feature selection, we added to each of our analysis information above a baseline classification using all available features; see

Figure 1 to

Figure 5. From this we can see if there is a difference between the optimal size of a feature set (opt) and the total number of available features (tot). This information is summarized in

Figure 7 by showing opt/tot (column four). As one can see for 2 of the 4 studied dataset (Enron and Arcene) the application of a feature selection method is clearly benefitial because the number of optimal features is much smaller than the number of total features. In contrast, for the Brown dataset not using feature selection is in fact best.

In addition to the size of the optimal feature set it is of interest to know what is the actual difference in performance. In

Figure 7 this information is shown by

corresponding to

where

is the F1-score for all features (shown as the baseline in all figures) and

is the F1-score for the optimal number of features of the feature selection methods. That means opt - the actually optimal number of features over all sizes - is different to opt’ which is only over the corresponding analysis range of the feature selection methods that does not extend to the full range because otherwise it would coincide with the baseline. Hence,

is the change in percentage between

and

. Importantly, a positive sign indicates that

is better than

whereas for a negative

is better than

.

From

Figure 7 (column five) one can see that for all studied datasets the value of

is quite small. Specifically, for three of the datasets, we obtain an actual improvement (as discussed above) when performing a feature selection (indicated by a positive sign) whereas for one dataset (Brown) using all features gives the best results. This implies that a feature selection mechanism, reducing the number of features, results in a small but noticeable performance decrease (less than

).

It is interesting to note that similar results have been found in [

50] by studying the classification of gene expression data from lung cancer patients. Currently, the frequency of datasets that either do not significantly or only marginally benefit from feature selection in achieving optimal prediction performance remains unclear. However, this aspect appears to be a topic deserving further attention. Also, this may be related to the redundancy of biomarkers that has been found for breast and prostate cancer [

42,

43] because the selection of optimal biomarkers is a feature selection problem [

20,

31].

To 5: The quantification of

allows to draw another important conclusion. Specifically, from the numerical values of

in

Figure 7 one can also see that using the results from the baseline gives a good approximation of the optimal prediction performance even when the optimal number of features is (much) less than the total number of features. Considering the fact that, depending on the data and the feature selection method, determining the optimal size of a feature set can require considerable resources, results for the baseline are easy and fast to obtain. Hence, results for the baseline should always be obtained for every analysis because its numerical value carry important information about optimal prediction capabilities.

Aside from the above results, we performed a feature removal analysis; see

Figure 3. This allowed us to obtain insights into the stability of the feature selection methods when successively removing the best features and then repeating the analysis. As one can see from

Figure 3, mRMR is most sensitive showing the most severe response. In fact, removing 5000 or more features leads to the breakdown of mRMR. In contrast, all other feature selection methods including SHAP are quite robust given reasonable results even when more than 10000 features are removed. On the other hand, when removing less than 1000 all methods including mRMR show a good performance.

Finally, we would like to re-emphasize that, theoretically, the best possible feature set is called Markov Blanket and it is a minimally sufficient set that carries all the information about the target variable in a dataset. It is important to note that the Markov Blanket is a property of the causal relations among covariates represented by a dataset and not of a model. Interestingly, methods like PPFS [

30] (the slowest method in our study; see

Figure 6) attempt to directly estimate the Markov’s Blanket. Despite this well-justified approach and good numerical results (see

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) PPFS is for no dataset the top performer. Instead, more heuristic approaches including SHAP perform better and are much faster. This indicates that there is a crucial difference between a theoretical characterization of a problem and a numerical estimator for its approximation. Especially, when data are inapt, e.g., providing only observational data without perturbations, for conducting a causal inference [

17,

32].

Figure 1.

Performance for the Enron spam detection (binary classification). The F1-scores are shown in dependence on the number of features; see legend for the color code of the feature selection method. Top: Results for training data. Bottom: Results for test data.

Figure 1.

Performance for the Enron spam detection (binary classification). The F1-scores are shown in dependence on the number of features; see legend for the color code of the feature selection method. Top: Results for training data. Bottom: Results for test data.

Figure 2.

Performance for the Brown corpus genre categorization (multi-class classification). The F1-scores are shown in dependence on the number of features; see legend for the color code of the feature selection method. Top: Results for training data. Bottom: Results for test data.

Figure 2.

Performance for the Brown corpus genre categorization (multi-class classification). The F1-scores are shown in dependence on the number of features; see legend for the color code of the feature selection method. Top: Results for training data. Bottom: Results for test data.

Figure 3.

Performance for the Brown corpus genre categorization (multi-class classification). The F1-scores are shown in dependence on the number of removed (best) features; see legend for the color code of the feature selection method. Top: Results for training data. Bottom: Results for test data.

Figure 3.

Performance for the Brown corpus genre categorization (multi-class classification). The F1-scores are shown in dependence on the number of removed (best) features; see legend for the color code of the feature selection method. Top: Results for training data. Bottom: Results for test data.

Figure 4.

Performance for the Arcene cancer classification (binary classification). The F1-scores are shown in dependence on the number of features; see legend for the color code of the feature selection method. Top: Results for training data. Bottom: Results for test data.

Figure 4.

Performance for the Arcene cancer classification (binary classification). The F1-scores are shown in dependence on the number of features; see legend for the color code of the feature selection method. Top: Results for training data. Bottom: Results for test data.

Figure 5.

Performance for the Ionosphere radar signals (binary classification). The F1-scores are shown in dependence on the number of features; see legend for the color code of the feature selection method. Top: Results for training data. Bottom: Results for test data.

Figure 5.

Performance for the Ionosphere radar signals (binary classification). The F1-scores are shown in dependence on the number of features; see legend for the color code of the feature selection method. Top: Results for training data. Bottom: Results for test data.

Figure 6.

Runtime of the feature methods in dependence on the number of features in a dataset.

Figure 6.

Runtime of the feature methods in dependence on the number of features in a dataset.

Figure 7.

Summary of all results. The best performing feature selection method over all sizes of feature sets (FS) is shown in bold. The feature selection method in bracket indicates that the best performing method performs unsatisfactorily. LFS (large feature sets), SFS (small feature sets) and VSFS (very small feature sets)

Figure 7.

Summary of all results. The best performing feature selection method over all sizes of feature sets (FS) is shown in bold. The feature selection method in bracket indicates that the best performing method performs unsatisfactorily. LFS (large feature sets), SFS (small feature sets) and VSFS (very small feature sets)

Table 1.

Jaccard scores for the Enron data. Shown are the Jaccard scores between features from the Shapley based method and all other feature selection methods for a different number of features (first column).

Table 1.

Jaccard scores for the Enron data. Shown are the Jaccard scores between features from the Shapley based method and all other feature selection methods for a different number of features (first column).

| |

ECCD |

MI |

TRL |

LM |

TS |

TF-IDF |

|

| features |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 50 |

0.205 |

0.351 |

0.075 |

0.235 |

0.220 |

0.266 |

0.299 |

| 100 |

0.235 |

0.351 |

0.047 |

0.282 |

0.266 |

0.282 |

0.351 |

| 200 |

0.286 |

0.394 |

0.042 |

0.356 |

0.338 |

0.270 |

0.375 |

| 500 |

0.247 |

0.344 |

0.018 |

0.445 |

0.422 |

0.357 |

0.350 |

| 1000 |

0.214 |

0.299 |

0.010 |

0.505 |

0.499 |

0.463 |

0.305 |

| 3000 |

0.099 |

0.132 |

0.016 |

0.192 |

0.191 |

0.184 |

0.137 |

| 5000 |

0.082 |

0.100 |

0.024 |

0.125 |

0.125 |

0.121 |

0.102 |

| 10000 |

0.070 |

0.076 |

0.042 |

0.085 |

0.085 |

0.085 |

0.077 |

| 15000 |

0.082 |

0.086 |

0.037 |

0.092 |

0.092 |

0.092 |

0.087 |

| 25000 |

0.112 |

0.113 |

0.110 |

0.113 |

0.113 |

0.114 |

0.113 |

Table 2.

Jaccard scores between all feature selection methods for the Enron data. The shown results are for 3000 features.

Table 2.

Jaccard scores between all feature selection methods for the Enron data. The shown results are for 3000 features.

| |

ECCD |

SHAP |

MI |

TRL |

LM |

TS |

TF-IDF |

|

| ECCD |

1.000 |

0.099 |

0.757 |

0.001 |

0.354 |

0.338 |

0.360 |

0.679 |

| SHAP |

0.099 |

1.000 |

0.132 |

0.016 |

0.192 |

0.191 |

0.184 |

0.137 |

| MI |

0.757 |

0.132 |

1.000 |

0.003 |

0.483 |

0.463 |

0.475 |

0.895 |

| TRL |

0.001 |

0.016 |

0.003 |

1.000 |

0.011 |

0.011 |

0.009 |

0.003 |

| LM |

0.354 |

0.192 |

0.483 |

0.011 |

1.000 |

0.963 |

0.815 |

0.519 |

| TS |

0.338 |

0.191 |

0.463 |

0.011 |

0.963 |

1.000 |

0.816 |

0.499 |

| TF-IDF |

0.360 |

0.184 |

0.475 |

0.009 |

0.815 |

0.816 |

1.000 |

0.505 |

| chi2 |

0.679 |

0.137 |

0.895 |

0.003 |

0.519 |

0.499 |

0.505 |

1.000 |

Table 3.

Jaccard score between all feature selection methods for 10000 features for the Brown data.

Table 3.

Jaccard score between all feature selection methods for 10000 features for the Brown data.

| |

TF-IDF |

mRMR |

TRL |

LM |

TS |

MI |

ECCD |

|

SHAP |

| TF-IDF |

1.000 |

0.639 |

0.388 |

0.446 |

0.651 |

0.643 |

0.454 |

0.568 |

0.299 |

| mRMR |

0.639 |

1.000 |

0.451 |

0.530 |

0.743 |

0.825 |

0.387 |

0.494 |

0.309 |

| TRL |

0.388 |

0.451 |

1.000 |

0.313 |

0.433 |

0.448 |

0.210 |

0.283 |

0.281 |

| LM |

0.446 |

0.530 |

0.313 |

1.000 |

0.558 |

0.533 |

0.411 |

0.442 |

0.262 |

| TS |

0.651 |

0.743 |

0.433 |

0.558 |

1.000 |

0.745 |

0.398 |

0.548 |

0.304 |

| MI |

0.643 |

0.825 |

0.448 |

0.533 |

0.745 |

1.000 |

0.388 |

0.500 |

0.306 |

| ECCD |

0.454 |

0.387 |

0.210 |

0.411 |

0.398 |

0.388 |

1.000 |

0.550 |

0.223 |

|

0.568 |

0.494 |

0.283 |

0.442 |

0.548 |

0.500 |

0.550 |

1.000 |

0.269 |

| SHAP |

0.299 |

0.309 |

0.281 |

0.262 |

0.304 |

0.306 |

0.223 |

0.269 |

1.000 |

Table 4.

Results for the Arcene data. Jaccard score between all feature selection methods for 100 features.

Table 4.

Results for the Arcene data. Jaccard score between all feature selection methods for 100 features.

| |

F-stat |

MI |

ISV |

mRMR |

JMI |

SHAP |

| F-stat |

1.000 |

0.015 |

0.010 |

0.010 |

0.005 |

0.010 |

| MI |

0.015 |

1.000 |

0.026 |

0.020 |

0.015 |

0.031 |

| ISV |

0.010 |

0.026 |

1.000 |

0.036 |

0.005 |

0.099 |

| mRMR |

0.010 |

0.020 |

0.036 |

1.000 |

0.010 |

0.026 |

| JMI |

0.005 |

0.015 |

0.005 |

0.010 |

1.000 |

0.005 |

| SHAP |

0.010 |

0.031 |

0.099 |

0.026 |

0.005 |

1.000 |

Table 5.

Results for the the Ionosphere dataset. Jaccard score between all feature selection methods for 5 features.

Table 5.

Results for the the Ionosphere dataset. Jaccard score between all feature selection methods for 5 features.

| |

SHAP |

JMI |

ISV |

MI |

mRMR |

F-stat |

| SHAP |

1.000 |

0.250 |

0.429 |

0.250 |

0.111 |

0.250 |

| JMI |

0.250 |

1.000 |

0.250 |

0.250 |

0.250 |

0.111 |

| ISV |

0.429 |

0.250 |

1.000 |

0.429 |

0.111 |

0.250 |

| MI |

0.250 |

0.250 |

0.429 |

1.000 |

0.111 |

0.429 |

| mRMR |

0.111 |

0.250 |

0.111 |

0.111 |

1.000 |

0.429 |

| F-stat |

0.250 |

0.111 |

0.250 |

0.429 |

0.429 |

1.000 |

Table 6.

Time complexity of the different feature selection methods.

Table 6.

Time complexity of the different feature selection methods.

| Method |

Time Complexity |

Notes |

| c-TFIDF |

|

n: number of features, L: average length of all documents in a class. |

| JMI |

|

n: number of features, d: number of samples |

| TS |

|

n: number of features, d: number of samples |

| MI |

|

with optimization is possible |

|

|

with optimization is possible |

| TRL |

|

m: number of classes, n: number of features, d: samples |

| ECCD |

|

m: number of classes, n: number of features, d: samples |

| LM |

|

m: number of classes, n: number of features, d: samples |

| F-stat |

|

n: number of features, d: number of samples |

| SHAP |

|

d: max depth of a tree model, t: number of trees in a model, l: maximum number of leaves |

| LFS |

|

n: all features, k: number of selected features |

| SFS |

|

n: number of features |

| PPFS |

|

b: copies, k: folds, n: features |

| mRMR |

|

n: features, d: samples |

| ISV |

|

n: all features, k: number of selected features |