1. Introduction

Septal accessory pathways (APs) are challenging targets, representing 30% of all APs [

1]. Ablation of anteroseptal and midseptal APs increases the risk of atrioventricular (AV) block due to their proximity to the normal AV conduction system. However, AV block may also occur in other septal locations. In contrast, the complex anatomy of the posteroseptal space presents a risk of coronary injury [

2].

Radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFA) is the preferred treatment for eliminating accessory pathways (APs) [

3]. However, RFA for septal APs is linked to higher complication rates than other locations [

4]. Since 2003, cryoablation has emerged as a safe alternative to RFA for several arrhythmogenic substrates, particularly in the septal region [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The pediatric literature indicates that cryoablation has higher recurrence rates compared to RFA. Nevertheless, some benefits of cryothermal energy, such as lesion reversibility, a reduced risk of thrombus formation, and improved catheter stability, make it a favorable option when the AP is near the AV node or bundle of His [

6,

8,

9].

Although many expert consensus reports on the management of AP in the pediatric population estimate an overall acute procedural success rate of 95%, septal AP ablation presents lower acute success rates with higher recurrence rates when evaluated over a more extended follow-up period [

10,

11,

12]. Many patients require multiple procedures to achieve definitive success.

This study aims to contribute to pediatric literature by sharing our long-term experience with septal AP ablations using limited fluoroscopy at a single center. Consequently, we evaluated the initial and repeat procedures regarding techniques and strategies to understand better the factors that may have influenced long-term outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Study Design

This retrospective, single-center study involved reviewing the clinical and procedural reports of patients who underwent electrophysiological studies (EPS) for septal atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia substrates mediated by APs in the Pediatric Cardiology/Electrophysiology Department of Medipol University in Istanbul, Turkey, between July 2012 and July 2023. Data collection was performed using FileMaker® software and included the following variables: patient characteristics, type of access, location of APs, presence of additional arrhythmia substrates, type of catheter and energy used, imaging modality used to guide the procedure, transseptal puncture, procedure duration, fluoroscopy duration, and complications. Initial ablation data were incorporated for patients who underwent second or third ablation procedures due to recurrent or unsuccessful attempts. The study received approval from our institution’s ethical committee.

2.2. Procedure

Informed written consent was obtained from all patients’ legal guardians, and retrospective case analysis was conducted under a consent waiver approved by the local institutional research committee.

Antiarrhythmic medications were discontinued at least five half-lives prior to the procedure. All procedures were conducted under general anesthesia using an EnSite 3D electroanatomic system (St. Jude Medical, Inc., St. Paul, MN, USA) with limited fluoroscopy. A comprehensive electrophysiological study (EPS) was initiated to identify the arrhythmia substrate and evaluate its characteristics. Initially, a risk assessment was performed for manifest AP (Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome [WPW]). Risk stratification was based on consensus guidelines established by experts from the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society in collaboration with the Heart Rhythm Society in 2012, along with the study published by Etheridge et al. in 2018. The shortest pre-excitatory RR interval (SPERRI), the anterograde effective refractory period of the AP (APERP), and the shortest paced cycle length with preexcitation during rapid atrial pacing (SPPCL) ≤ 250 ms are considered to carry an increased risk for sudden cardiac death. Borderline risk is defined as values for APERP, SPERRI, and SPPCL between 250 and 300 ms.13,14

Delta wave mapping and retrograde mapping during supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) and/or V-pace were utilized in patients with manifest APs), whereas the latter two techniques were employed in patients with concealed APs. Additionally, a qS pattern in the unipolar electrogram was targeted during sinus rhythm or atrial pacing in patients with manifest APs. Electroanatomic mapping assisted in identifying potential targets within a 3D geometric framework.

The location of APs was defined as follows [

11].

1. Anteroseptal (AS) if earliest ventricular activation during anterograde conduction or earliest retrograde atrial activation during ventricular pacing were in the upper 1/3 of the triangle of Koch, including the presence of a His bundle potential (0.1 mV) at the successful ablation region.

2. Midseptal (MS) if the earliest ventricular activation during anterograde conduction or earliest retrograde atrial activation conduction during ventricular pacing were in the middle third of the triangle of Koch.

3. Posteroseptal (PS) if the earliest ventricular activation during anterograde conduction or retrograde atrial activation during ventricular pacing were located near or in the CS ostium or inside the proximal CS (right-PS). If the AP was located on the left side of the septum opposite the right-PS location, it was labeled as left-PS AP.

Ablations conducted through the CS and middle cardiac vein were categorized under a separate heading as “epicardial ablations.”

If the AP was considered to be left-sided, the patent foramen ovale was initially explored; otherwise, an anterograde approach was employed, typically through transeptal puncture under fluoroscopy utilizing a transseptal long sheath and Brokenbrough needle.

Catheter selection, technique, energy source, and ablation settings varied based on each case, resource availability, and expert preference. The Freezor Xtra™ catheter (8 FR, Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) with 6-mm and 8-mm tips were used for the cryoablation procedures. When using a 6-mm tip catheter, cryomapping was conducted at –30°C at the previously marked location. Cryomapping was stopped if no effect was observed within 30–45 seconds. When using an 8-mm tip catheter, short cryoablation test applications lasting 30 seconds were performed and were terminated when no effect was seen. If the patient had manifest atrial pre-excitation, cryomapping was carried out during sinus rhythm to monitor for loss of delta wave, during orthodromic tachycardia to terminate it, or during ventricular pacing to establish retrograde AP block. For concealed APs, cryomapping was conducted either during orthodromic tachycardia to terminate it or during ventricular pacing to establish retrograde AP block. Ablation continued at -70°C to -80°C for 240-360 seconds once the AP block was achieved. Finally, insurance lesions were applied to achieve the freeze-thaw-freeze effect.

Conventional RF energy (7 FR RF Marinr™ Multi-curve Steerable Catheter; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was primarily preferred and delivered using an IBI generator (St. Jude Medical) in a temperature-controlled mode at 40-50 Watts (W) with a temperature cut-off of 50–60 degrees Celsius (°C). Irrigated-tip RF catheters (7 FR 4-mm tip Cool Flex™ and 8 FR 4-mm tip Flex Ability™ Catheters; St. Jude Medical, Inc., St. Paul, MN, USA) were utilized with the same generator in temperature-controlled mode, starting with 25 W and increasing to 30-35 W, at 85–90 Ω and a temperature range of 30–35 °C. Power was titrated from 15 W to 20-25 W while delivering energy into the coronary sinus. The duration of the energy lesion was limited to 60 seconds, typically employing two consolidation lesions. Irrigated radiofrequency ablation (RFA) was preferred for patients weighing more than 30 kg when standard RF catheter procedures were unsuccessful or the desired wattage could not be achieved.

The AV node conduction was closely monitored during mapping and ablation. Ablation was stopped immediately if any AV conduction delay was observed, and an accelerated junctional rhythm was noted during RFA. Acute success was defined as the elimination of both antegrade and retrograde AP conduction, along with the absence of other arrhythmia substrates at the end of the 30-minute waiting period.

2.3. Follow-Up

All patients were routinely monitored for 24 hours after the procedure. A 12-lead ECG and echocardiography were performed before discharge. Another 12-lead ECG was obtained 2 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months after the ablation at our outpatient department or by the referring physician. Aspirin was continued for 6 weeks following left-sided procedures.

Recurrence is defined as the reappearance of anterograde AP conduction or SVT) as documented by ECG, 24-hour Holter monitoring, or through an event recorder. Palpitations alone are not considered a recurrence of arrhythmia. Long-term success is defined as the absence of any recurrence of manifest AP conduction or documented SVT during the follow-up period.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using version 21.0 of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. Descriptive features were expressed as percentages and mean ± standard deviation or as medians, depending on the distribution of the data as determined by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

During the study period, 291 children underwent 336 EPS and 332 ablation procedures. Ten patients (3.5%) had previously received EPS at other centers. The mean age and weight of the patients were 11.8 ± 4.9 years and 48.8 ± 27.3 kg, respectively. Congenital heart disease was present in 21 patients. The youngest patient included in the study was a 4-month-old (5 kg) infant diagnosed with ’tachycardia-induced dilated cardiomyopathy’ that was resistant to multiple antiarrhythmic drugs. Two hundred twenty-five cases (73%) were diagnosed with WPW syndrome (140 with SVT, 71 with asymptomatic WPW, and 1 with pre-excited atrial fibrillation), while 79 cases (27%) were diagnosed with SVT. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Initial procedure

We identified 298 AP connections in the 291 patients. Seven (2.4%) patients had multiple APs, including three with Ebstein anomaly. The prevailing anatomic AP location was PS (n = 159; 54%), followed by AS (n = 86; 30%) and MS (n = 46; 16%).

Of those diagnosed with WPW, 61 (28%) had high-risk AP based on procedural features, with APERP, SPERRI, and SPPCL ≤ 250 ms; 77 (34.5%) had borderline risk since their APERP, SPERRI, and SPPCL measurements ranged from 251 to 300 ms; 82 (36.5%) patients were classified as low risk according to their APERP, SPERRI, and SPPCL measurements ≥ 300 ms; and 5 (1%) cases were classified as unknown (

Table 2).

After the EPS, all patients except 3 underwent ablation procedures. In 70 (24%) cases, mapping was performed by stimulation SVT, in 116 (40%) cases by delta mapping, in 71 (25%) cases by both SVT stimulation and delta mapping, and in 31 (11%) cases by V-pacing mapping. Five (2%) AP connections showed “Mahaim-like AP” properties, which resulted in the prolongation of AH, shortening of HV, and negativity of VH intervals.

Cryoablation was used in 190 patients (66%), RFA in 36 patients (12.5%), and both RFA and cryoablation in 62 patients (21.5%). Irrigated RFA catheters were employed in 10 patients (3.4%). Cryoablation was conducted using a 6 mm-tipped catheter for 188 patients, an 8 mm-tipped catheter for 62 patients, and both types of catheters for 2 patients. The average number of complete cryoablation lesions was 6.2 ± 3.2.

The acute success rate of overall initial procedures was 89.6%. A transient successful effect of ablation was observed during the procedure, with immediate AP conduction returning in 7 patients. The acute success rate for cryoablation was 86.6%, showing the highest efficacy in MS and the lowest in PS locations (AS: 89.1%, MS: 91.1%, PS: 80.7%). The acute success rate for RFA was 94.1%. Thirty-two patients (11.1%) underwent epicardial ablations, with an acute success rate of 53.1%.

The overall recurrence rate was 11.3%, with the highest at the right-PS location (16.4%). Thirty-three patients presented with recurrences; 20 (61%) had WPW on baseline ECG, while 13 (39%) presented with documented SVT. The overall recurrence rate of cryoablation is 12.1%, with the highest at the PS location (18.9%).

In our electrophysiology practice, fluoroscopy is only utilized when a transseptal approach is required or in rare cases to confirm catheter position. Fluoroscopy was used for 39 patients (13.5%), with a mean fluoroscopy time of 5.2±3.7 minutes (range: 0.3-18.3). A transseptal puncture was performed in 22 cases (7.6%) to identify the optimal site in the left PS area. The mean procedure duration was 154±54 minutes (range: 54-340).

3.3. Redo procedure

During a mean follow-up of 88.5±33.0 months, 45 out of 291 patients underwent repeat procedures due to initial failure or recurrences. The second procedure was conducted an average of 19.2 months after the initial ablation, with an average of 1.2 procedures per patient.

The acute success rate of redo procedures was 95.3%. During these redo procedures, an irrigated RFA was preferred in 20 (45%) cases, all of which were PS locations (19 right-PS, 1 left-PS). Only 3 (1%) patients underwent ≥ 2 procedures for the initial substrate that recurred multiple times. Consequently, the long-term success rate reached 99% when considering the repeat procedures. A comparison of initial and redo procedures based on pathway locations and ablation outcomes is summarized in

Table 3.

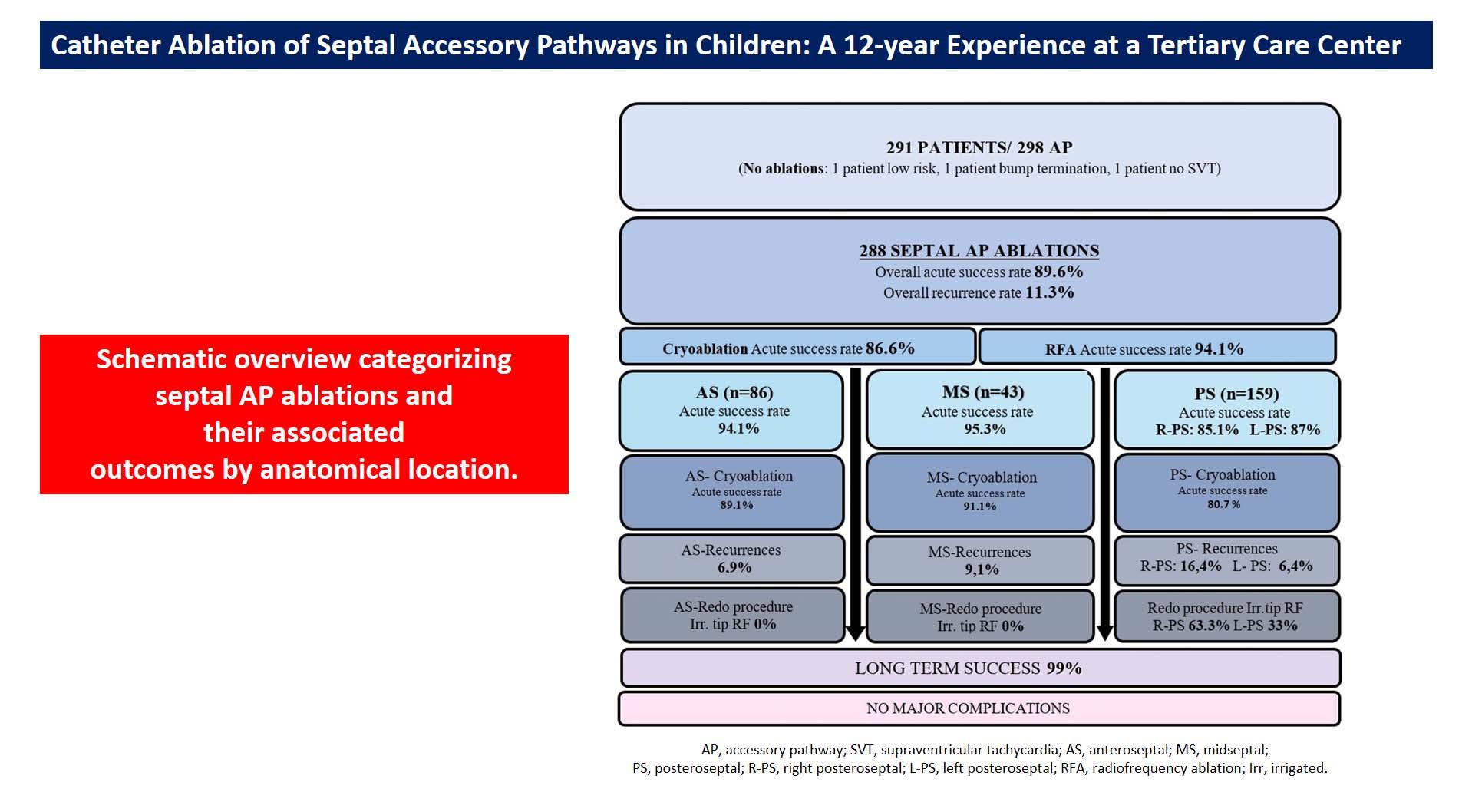

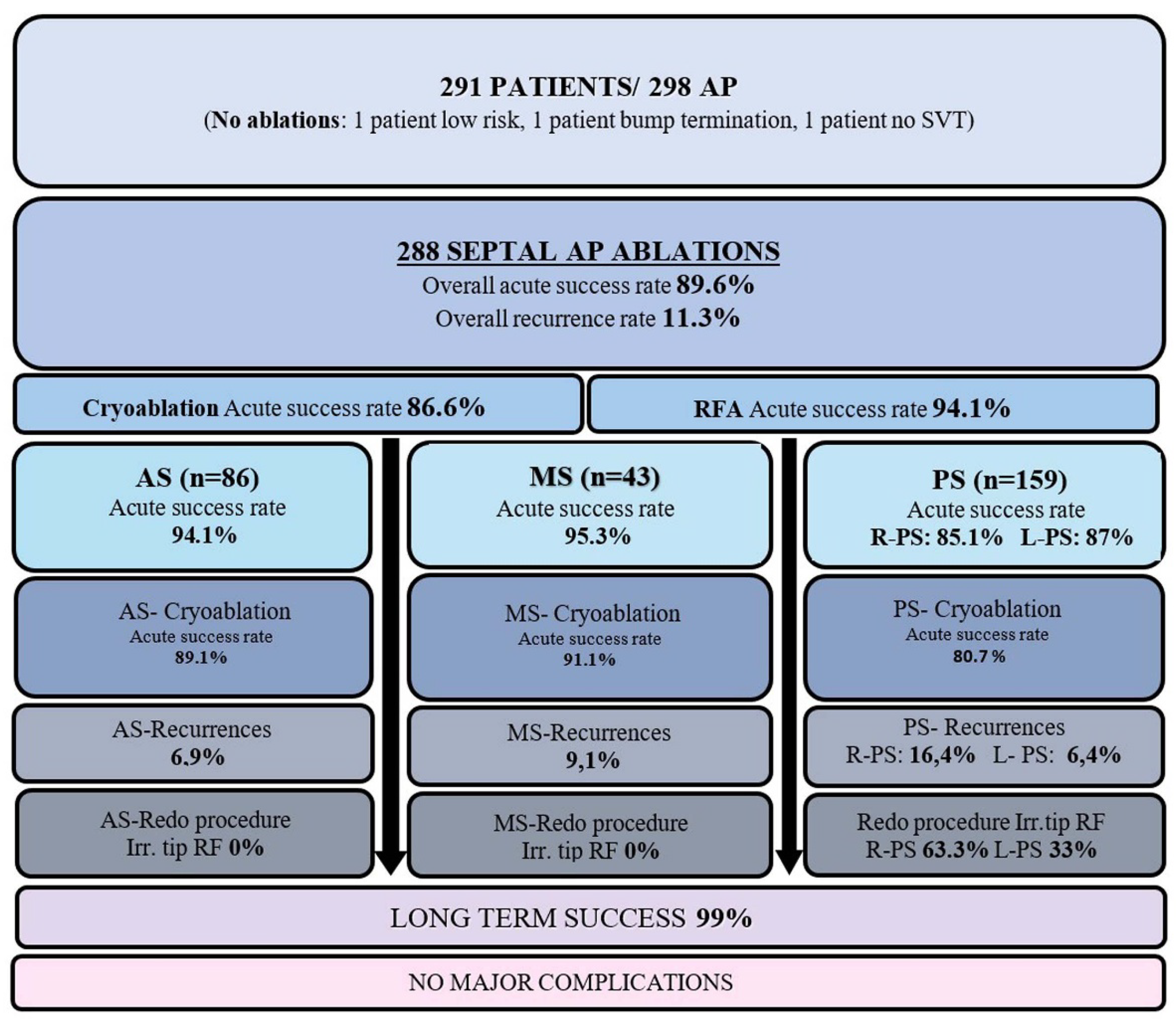

A schematic overview of the study categorizing septal AP ablations and their associated outcomes by anatomical location was presented in

Figure 1.

3.4. Complications

Transient complete AV block occurred during energy delivery, and complete recovery was observed after tissue warming. At long-term follow-up, no permanent PR interval prolongation was observed, and we did not observe any other major complications, such as pericardial effusion and thrombotic events. None of the patients developed clinical or ECG signs of new-onset ischemia.

4. Discussion

The present study supports excellent contemporary pediatric data showing that the long-term high success rate of septal AP ablation, > 97%, can be achieved safely. We observed a moderate recurrence rate and a high long-term success rate, achieved with an average of 1.2 procedures per patient. Manifest APs and right-PS APs presented with the highest recurrence rate in the long term. RFA for the treatment of septal AP has higher overall acute and long-term efficacy rates than cryo energy. Cryoablation of PS APs showed the lowest acute and long-term efficacy rates compared to other septal APs. Furthermore, the other main finding of the present study was that irrigated-tip catheters are effective and safe for right-PS APs resistant to conventional RFA or for ones who presented with recurrences.

Cryoablation has emerged as a safe alternative to RFA for various arrhythmogenic substrates, particularly in the septal region among young patients with reduced dimensions of Koc

h’s triangle and overall tissue thickness [

2]. The significance of precise mapping and catheter stability is paramount, yet a notable drawback is the stiffness of the catheter, complicating manipulation in small hearts [

15]. Studies involving pediatric and adult populations have reported similar acute success rates for cryoablation and RFA, albeit with higher recurrence rates for cryoablation. Bar-Cohen et al. reported an acute success rate of 78% and a recurrence rate of 45% over an average follow-up period of 207 days. The risk of recurrence was noted to be particularly elevated in MS locations. The low success and high recurrence rates were attributed to the use of a 4 mm–tip cryocatheter in 89% of cases [

7]. We previously reported the acute success rate of cryoablation for eliminating AS APs was 95.8%, with a short-term recurrence rate of 8.7% [

16]. Bastani et al. observed a similar acute success rate but with a higher recurrence rate of 27% during an average follow-up of 33 months [

5].

The first meta-analysis of 4,244 pediatric cohort articles comparing the efficacy and safety of cryoablation versus RFA for septal substrates reported similar acute procedural success rates for cryoablation and RFA (86% and 89%, respectively) [

17]. However, it was noted that efficacy was highly dependent on the AP) location. The acute procedural success rate of cryoablation was highest for parahissian APs and lowest for posteroseptal (PS) APs. The recurrence rate for cryoablation was 18.1%, while it was 9.9% for RFA. Despite their similar acute efficacy rates, the meta-analysis demonstrates the superiority of RFA over cryoablation regarding long-term efficacy outcomes. When analyzing results according to AP location, cryoablatio

n’s long-term outcomes for parahissian APs are comparable to those achieved by RFA, but its long-term efficacy at other septal locations was significantly lower. We reported an acute success rate of 93% for cryoablation and a recurrence rate of 12.5% for septal APs during mid-term follow-up from our center [

18]. In our study, the overall success rate of initial procedures was 89.6%, and the recurrence rate was 11.3% in an extended pediatric case series with longer follow-up. Both RFA and cryoablation demonstrated excellent acute outcomes. The procedur

e’s success was highly dependent on the AP location, with the highest efficacy observed in midseptal (MS) locations and the lowest in PS locations.

The PS region of the heart is likely the most complex area for catheter ablation and is associated with a higher recurrence rate. A common reason for unsuccessful ablation attempts with the standard endocardial approach is the epicardial localization of the APs, which may necessitate intervention within the CS [

19,

20]. Recent studies suggest that the possibility of a CS diverticulum should be considered in cases of failed ablation attempts in the CS [

15,

20,

21]. A previously published study involving 51 patients with a PS pathway found that 31% had a CS diverticulum [

22]. Furthermore, a CS diverticulum was reported in 40% of patients undergoing CS ablations [

19]. Some studies routinely recommend coronary vein angiography to detect coronary vein anomalies during PS ablations to enhance acute success [

23]. In the study by Collins et al., cryoablation in the CS was successful in 71% of cases [

21]. Due to the low acute success rates and high recurrence rates associated with cryoenergy, data indicated that RFA was predominantly used in adult studies with better outcomes [

21,

22]. Raja J. Selvaraj et al. collected data on adults who underwent ablation of PS APs with manifest preexcitation, comparing cases by dividing them into two groups based on the presence or absence of diverticulum [

22]. RF energy was used for ablation in all cases. The acute procedural success rate was 88% in the diverticulum group and 97% in the non-diverticulum group. Our findings align with those of previous studies, showing that epicardial ablations had the highest number of unsuccessful applications. Since routine venography was not performed prior to CS ablations, the possibility of a coronary diverticulum may have been overlooked, potentially contributing to procedural failure. Coronary artery injury represents the most significant concern associated with intra-CS ablation with RF energy [

15]. In a comprehensive study involving 68 ablation procedures in 62 patients, Alazard et al. conducted coronary angiography in 29 cases before and after the procedure [

24]. In 12 cases, the ablation area was found to be in close proximity to the coronary artery, with a distance of less than 5 mm. In these cases, coronary damage was observed in 3 patients, with two cases involving an irrigated RF catheter and one case involving a non-irrigated RF catheter. In contrast, no coronary artery injury was reported in patients with a true safety margin. Although we did not perform coronary artery angiography in any patients before the procedure, all patients were closely monitored for electrocardiographic ST changes for ischemia throughout the procedure. None of the patients developed clinical or ECG signs of new onset ischemia.

In addition to the epicardial location in the PS area, the causes of recurrence were likely multiple, including insufficient lesion depth and inadequate energy delivery. Over the years, studies have indicated that irrigated RF energy is more effective on deep myocardial or epicardial substrates than on superficial endocardial structures [

25,

26]. Kamali et al. reported that their high success rate for CS ablations is linked to the use of irrigated RFA. In the study by Yamane et al., irrigated RFA (often used after conventional RFA) was associated with improved procedural success in right-PS APs [

27]. In our study, the overall acute success rate for right-PS APs was 85.1%. Furthermore, right-PS APs exhibited the highest long-term recurrence rate (16.4%). Cryoablation demonstrated the lowest acute efficacy rate for the PS AP location. Consequently, we primarily utilized irrigated RFA in 60.6% of PS redo procedures. Given the numerous heat-related complications, including perforation, coronary damage, and the risk of venous stenosis in CS, we administered irrigated RF energy in a temperature-controlled mode ranging from 15-25 W within the CS and 25-35 W in the PS area. We attribute the low complication rate to these measures. Despite technological improvements, extensive RFA experience, and cautious RF applications, the iatrogenic incidence of undesired AV block during septal ablations is still non-negligible. No case of persistent AV block was reported using cryoablation, whereas RFA accounts for between 2 and 10 % [

4,

17,

28]. Knowledge of these risks may influence both the patient’s and the electrophysiologists’ decisions. For instance, in a wide pediatric case series by Mandapati et al. (127 patients with 145 septal APs), RF ablation could not be performed [

28].Due to the high risk of AV block, the electrophysiology study had to be stopped in 17 % of patients with anteroseptal APs and 15 % of patients with midseptal APs. Similarly, Ergul et al. reported that RFA was not performed in 29% of their patients who underwent previous EPSs at other centers due to the high risk of AV block [

16]. So, despite the concerns regarding a greater recurrence rate, cryo energy has been recommended for AS and MS locations due to AV block risk reported for RFA [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

28]. In our study, only cryoablation was preferred in 94.1% of AS and 76% of MS APs. There were no instances of permanent damage to normal conduction in our series. Besides monitoring AV node conduction closely during mapping and ablation, we emphasize confirmation of underlying intact AV node conduction with differential atrial pacing maneuvres before and during the ablation. Using long sheaths, a superior approach via the jugular vein in selected patients, and performing the ablation during apnea may also increase catheter stability and help limit the risk of AV node injury.

Previous studies have reported that Ebstein’s anomaly poses a risk for failed ablation and recurrence, with difficulties being related to the high prevalence of multiple pathways and the lack of catheter stability caused by the displacement of the tricuspid valve [

15,

29]. Walsh et al. found similar results, noting that Ebstein malformation does not predict procedural failure or recurrence [

30]. In our study, we did not observe procedural failure or recurrence in patients diagnosed with Ebstein’s anomaly. However, we believe that the limited number of patients in our study is insufficient to draw such a conclusion.

We have achieved an excellent long-term success rate within our patient group. It can be argued that reversible tissue injury represents a relative weakness of cryoablation concerning recurrence risk. However, this aspect may also be a major strength of the technology when ablating near-normal conduction tissues. In our opinion, utilizing a larger catheter tip size and a greater number of cryo-energy applications could significantly affect the overall long-term success rate of cryoablation. This is because the freeze-thaw–freeze technique has been reported to result in more effective lesion formation. Particularly with the use of RFA energy, the potential benefit of consolidated lesions must be weighed against the risk of AV nodal conduction and coronary artery injury. In such cases, it may be appropriate to limit consolidation time and accept a reasonable risk of recurrence. Additionally, employing a 3D electroanatomic mapping system aids in targeting locations and helps place the insurance lesions at precise anatomical locations. Furthermore, redo procedures may be enhanced by incorporating steerable long sheaths, the implantation of irrigated RF catheter technologies, and utilizing angiograms to better understand the anatomy. These strategies have the potential to improve long-term outcomes.