1. Introduction

The oldest recorded air-breathing land animal, the millipede, Pneumodesmus newmani Wilson & Anderson, 2004, is enormously significant in the understanding of the evolution of the earliest terrestrial ecosystems (Wilson and Anderson, 2004; Brookfield, 2020; Buatois et al., 2022; Wellman et al., 2023). The single specimen was found by Mike Newman in 2001 in the Cowie Harbour Fish Bed (or Dictyocaris bed as fish are scarce), just east of Cowie, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. The age of this Fish bed is controversial. Using the current Silurian and Devonian time scales of Melchin et al (2020) and Becker et al. (2020), the Fish Bed was initially estimated as Downtonian (latest Silurian, Pridoli) based on the fish fauna (Westoll, 1951). Floral evidence from isolated inland exposures later pointed to a late Wenlock- early Ludlow (mid-Silurian) age (Marshall, 1991; Wellman, 1993). LA-ICP-MS U/Pb youngest single grain detrital zircon dates of 414.3±7.1 and 413.7±4.1(2σ) Ma, from strata bounding the fish bed, re-established the Pridoli/Lochkovian (latest Silurian-early Devonian) age (Suarez et al., 2017); but was followed by a return to a Wenlockian age again, based on further floral evidence and a youngest detrital zircon LA-ICP-MS U-Pb date of 430 ± 6 (1σ) Ma from adjacent, but fault-separated, exposures (Wellman et al., 2023).

In fact, the two divergent interpretations of the age of the Cowie Fish bed are easily reconciled by considering the locations of the materials analyzed, which come from separate fault-bounded structural blocks with different lithostratigraphy and fossils. The Pridoli/Lochkovian age comes from strata enclosing the Cowie Harbour Fish bed, while the late Wenlock age comes from sediments in a different structural block.

In order to place the earliest recorded air-breathing land animal in context and to establish its environmental setting and age, we review, in detail, the stratigraphy, sedimentology, paleontology, paleoenvironments, radiometric dating and structure of the late Silurian to early Devonian Stonehaven Group which hosts the Cowie Fish bed. The geology of the Lower Old Red Sandstone around Stonehaven (including the Stonehaven Group) is summarized in Gillen and Trewin (1986), McKellar (2017), and McKellar and Hartley (2021).

2. Structural units

Around Stonehaven, rock exposures adequate to determine stratigraphic and structural relationships are only found in the coastal exposures (Campbell, 1913; Gillen and Trewin, 1986; MacGregor, 1996; Adrian and Leleu, 2015; Shillito and Davies, 2017). Away from the coast, it is difficult to correlate strata across separate structural blocks because of the very limited bedrock exposure with over 90% of Quaternary cover and many faults (

Figure 1). Each exposed area thus needs to be examined separately and in detail.

2.1. Inland exposures

Evidence from the inland exposures can be easily dismissed as they show only diverse small and isolated outcrops in numerous fault splays along the Highland Boundary fault, juxtaposing diverse rock units (Anderson, 1947; McKay et al., 2020). The strata, apart from the two spore-bearing siltstone exposures in two isolated exposures (AS12, AS16) (Marshall, 1991, Wellman, 1993), were stratigraphically assigned purely on lithology (

Figure 1).

The Cowie Harbour Conglomerate member is mapped in extremely small isolated and faulted exposures to the N and NW; while the inland spore- and plant-bearing localities come from small isolated exposures in and near the Carron water south and west of Tewil farm, (Marshall, 1991; Wellman, 1993) (

Figure 1). The large supposed Castle Harbour Siltstone exposure mapped by the BGS lies one kilometre west of the spore-bearing localities along the south bank of the Carron water (

Figure 1). During a visit in October, 2024, only fine-grained-greenish-gray and purplish-gray sandstones with no interbedded siltstones were poorly exposed in the overgrown left bank meander cliff, but with no exposures in the stream bed and right bank.

2.2. Coastal exposures

On the Cowie foreshore, two distinct areas with differing stratigraphic sections are separated by a postulated tear fault through Cowie Harbour, which fault has been inferred for over 100 years on the stratigraphic differences across it (Campbell, 1913) (

Figure 2 inset) (see also Shillito, A.P and Davies, N.S., 2017, Figure 9, and Wellman et al., 2023,

Figure 3).

The northern block has a steeply NNW dipping overturned section of non-marine fluviatile and lacustrine section with supposed late Wenlock spore assemblages and a maximum youngest detrital zircon Llandoverian date of 439 ± 4 Ma from its lowermost beds as noted by Wellman et al. (2023). It is separated from the southern block by the inferred tear fault along Cowie Harbour.

The

southern block with a steeply NW dipping section, with a divergent strike and dip to the northern block, has a different section with the Cowie Harbour Conglomerate and the Cowie Harbour Fish bed (or

Dictyocaris bed), containing Pridoli/Lochkovian vertebrates and maximum youngest detrital zircon Lochkovian/Pragian date of 413.7±4.1 Ma (Suarez et al., 2017). The Cowie Fish bed occurs nowhere else, even where apparently similar enclosing strata are mapped in scattered inland exposures (

Figure 1).

To the south of the southern Cowie Harbour outcrop, a covered area of beach sand 500 metres wide, with an inferred fault, separates it from a foreshore outcrop attributed to the Cowie Formation, with another nearby foreshore outcrops just south around Stonehaven harbour, with the type section of the Carron Sandstone Formation (

Figure 1, section E).

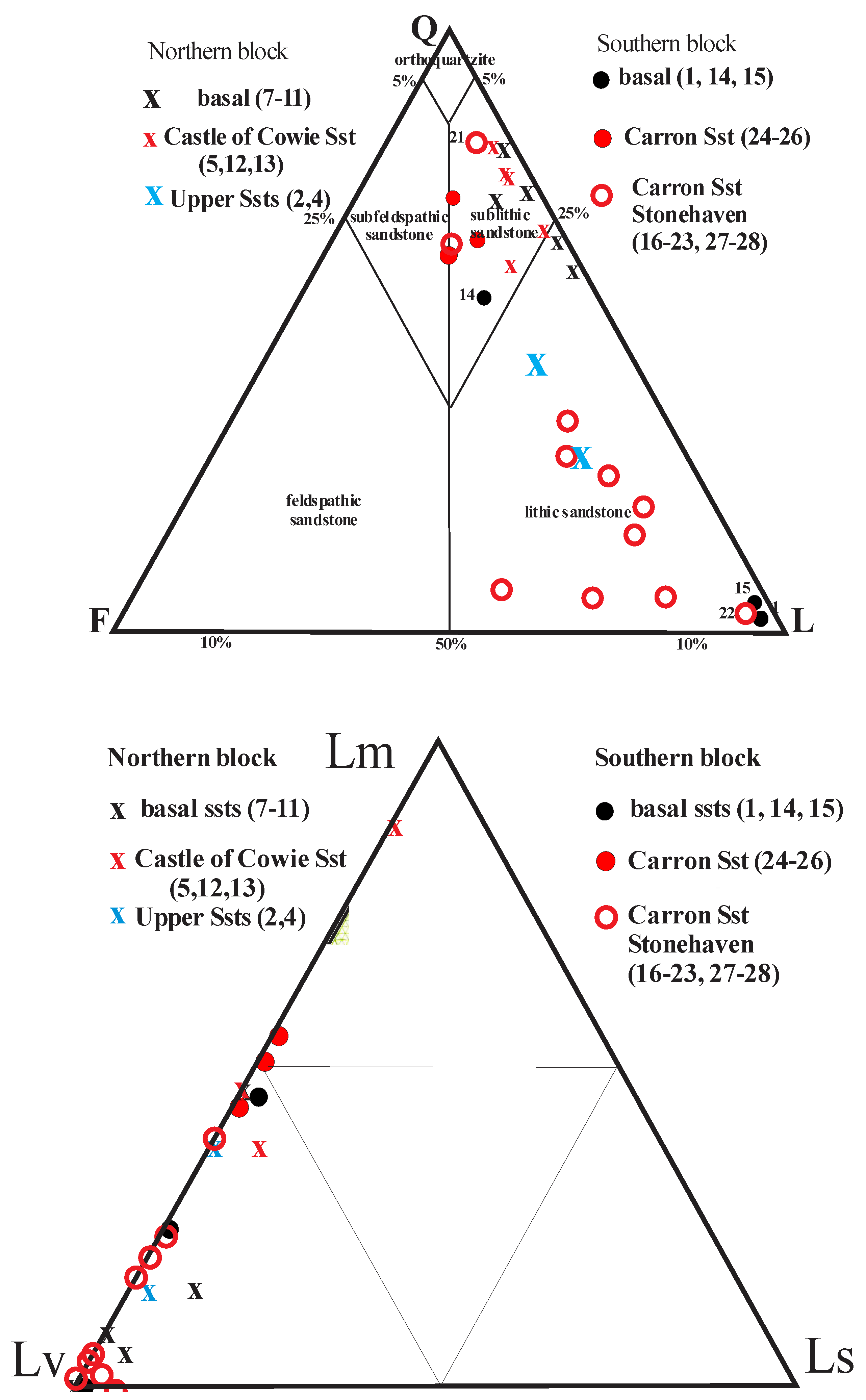

The detailed petrology of many of the Old Red Sandstones was reported by McKellar (2017; Appendix 2), but the locations not plotted on a detailed geological map. We have plotted the location and constituent values of samples relevant to this on supplementary table T1 and supplementary figure F1. In some units very few analyses are available and the results may be unrepresentative (Figure 9; Supplementary Fig F1 and Supplementary Table T1). The analyses are, however, compatible with those reported by Phillips (2007).

3. Descriptions and interpretations of the northern and southern blocks

3.1. Northern block

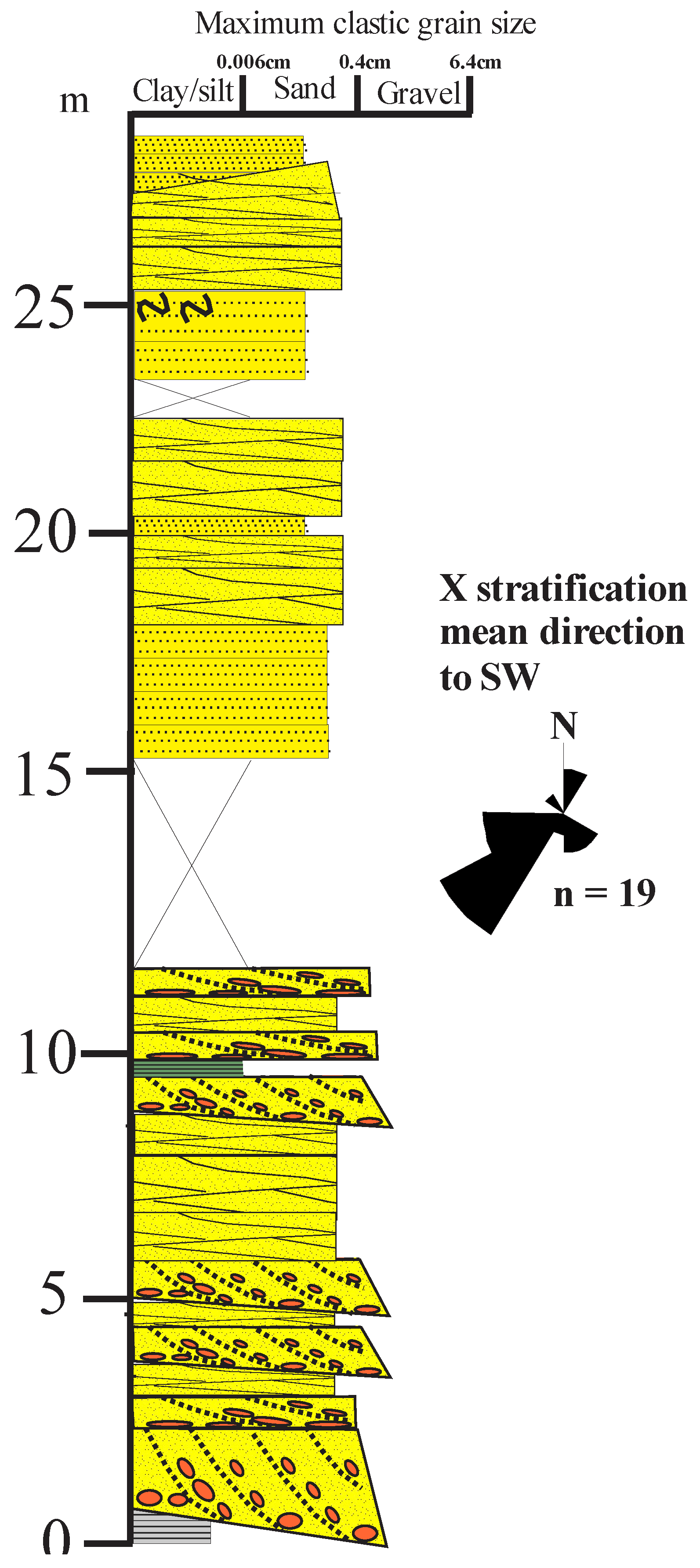

3.1.1. Sediments

The northern block has thin basal pediment breccias resting unconformably on the Highland Border Group basalts (

Figure 3) and contain angular clasts of reddened basalts and chert entirely derived from the underlying rocks (

Figure 4A, B).

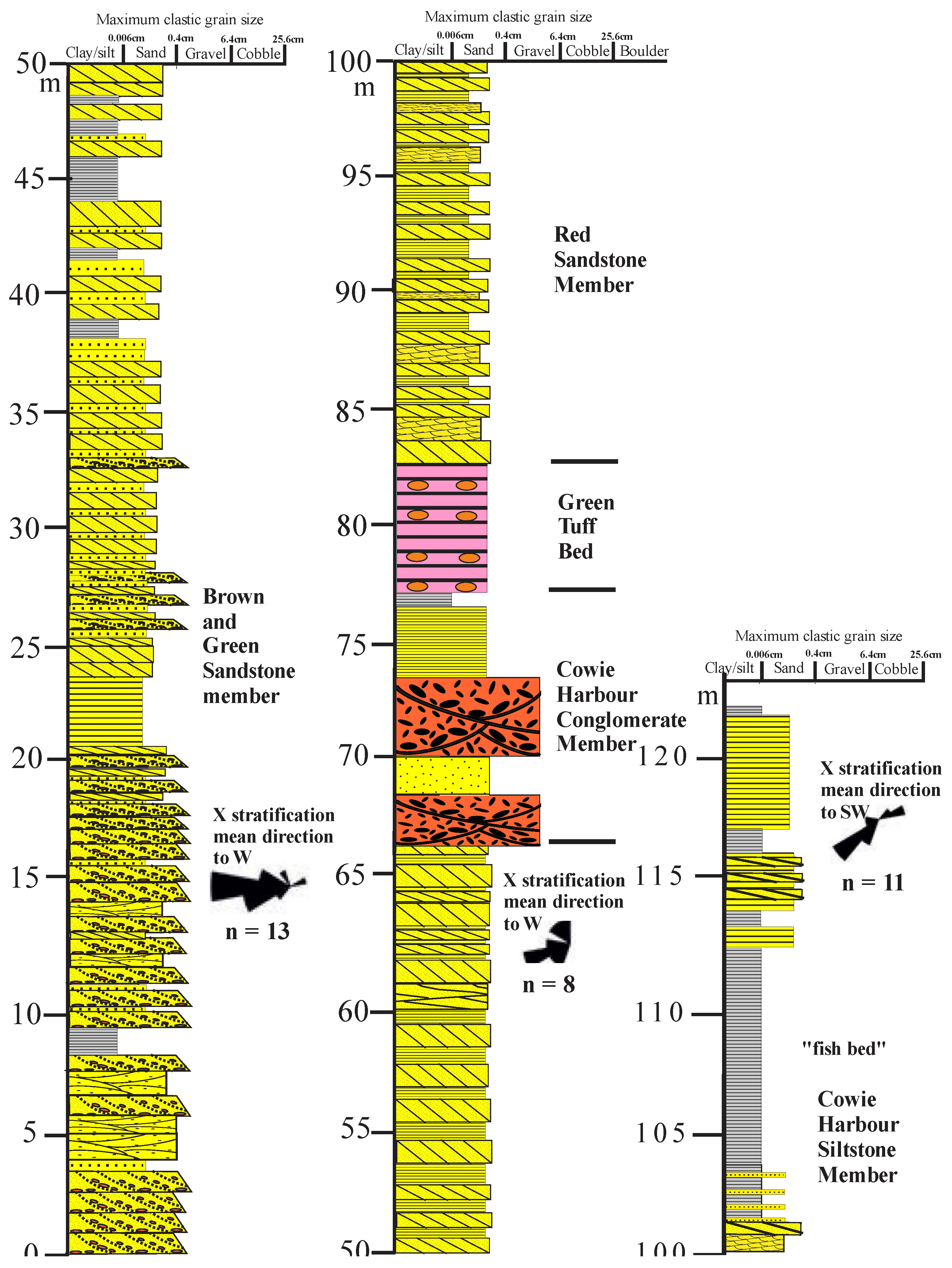

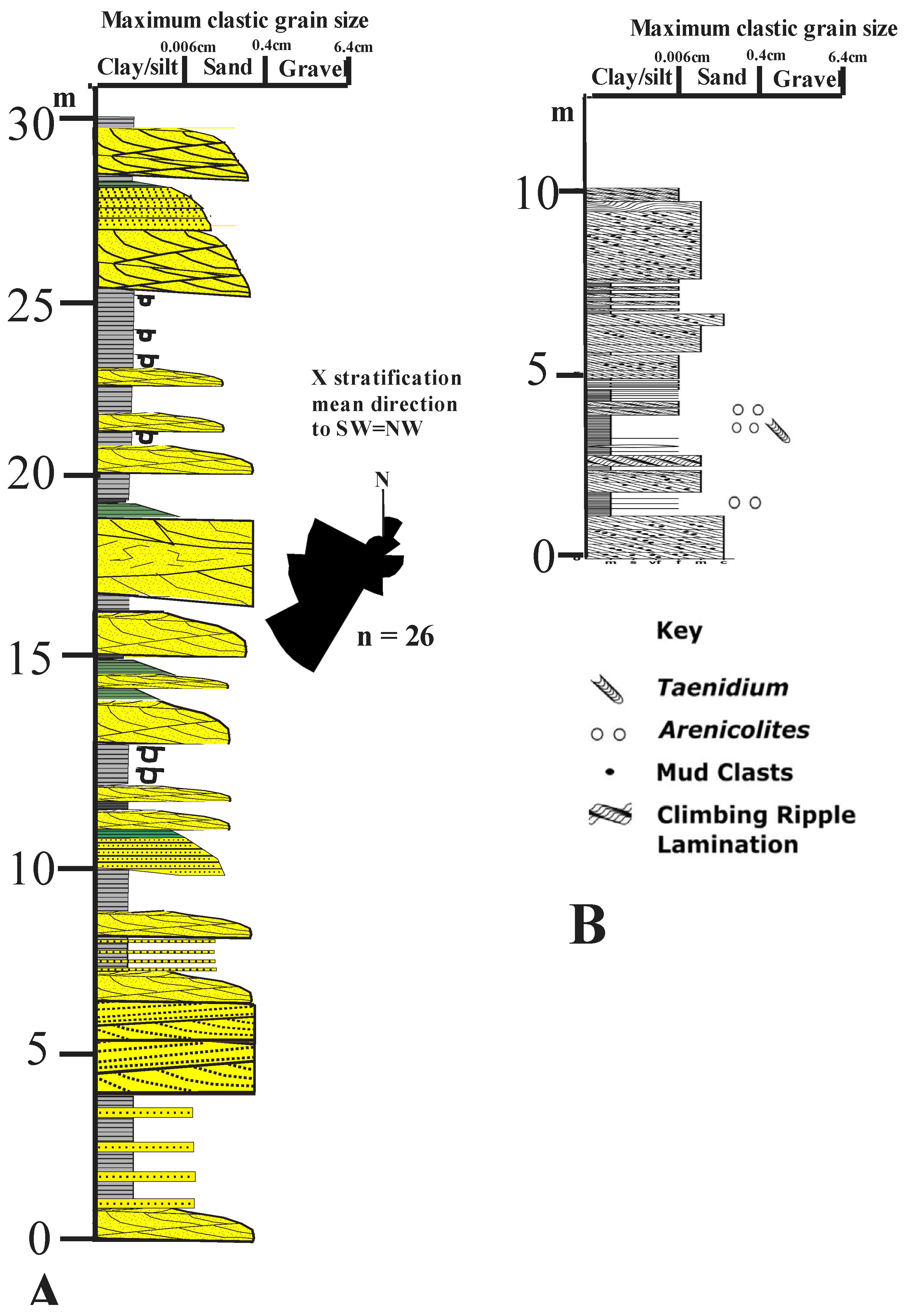

The breccias are overlain by about 90 metres of the Purple Sandstone Member, which consists of brownish to greenish, lithic volcaniclastic sandstones with minor interbedded red and grey siltstones and mudstones, with one thin interbedded andesite lava flow or sill at about + 10 metres. The lowermost beds are predominantly trough cross-bedded fine- to medium-grained sandstones, with minor parallel laminated sandstones and minor interbedded mudstones and siltstones, and with unidirectional paleocurrent flow to the ESE, with only a 90o spread. Such characteristics are typical of large low-gradient Platte type braided streams, far from bedrock sources, with variable flow, transporting medium-grained sand, with an abundance of linguoid bar and dune deposits (planar and trough crossbedding), but with no well-developed cyclicity (Smith, 1971; Miall, 2014).

Petrographically, the, basal Purple Sandstone samples (#7-11) are lithic to sublithic sandstones, dominated by acid to intermediate volcanic grains, with variable metasandstone grains, but very little feldspar, very low plagioclase/K-feldspar ratios, very low Qm/Qp ratios, and no biotite (

Figure 5; Supplementary Fig F1 and Supplementary Table T1). Sources are thus dominantly acid to intermediate volcanics to the west-north-west.

The higher beds starting just below the andesite, are tabular and trough cross-bedded fine- to coarse- grained lithic to sublithic sandstones with abundant often burrowed mudstones and siltstones (Figs. 3, 4C, D). The fining upward cycles indicate lateral accretion deposits in a lowland channelized river system with extensive floodplain deposits, while trace fossils and fragmentary plant remains indicate a humid climate (Li et al., 2023; Finotello et al., 2024; Wang, 2024). Such characteristics are found in Donjek type wet climate braided streams, distinguished by fining-upward cycles caused by lateral point-bar accretion or vertical channel aggradation, with longitudinal and linguoid-bar deposits, channel-floor dune deposits, and bar-top and fine overbank deposits (Miall, 2014). Cycles are commonly less than 3 m thick, as in the Purple Sandstone cycles. Though dominantly WNW, the almost 360

o spread in paleocurrents (Gillen and Trewin, 1987; Hartley and Leleu, 2015) (

Figure 3), however, suggests an intricate meandering channel pattern analogous to multi-channel (anastomosing) rivers on alluvial plains forming under low energy conditions near local base levels (Makaske, 2001). The distinction between sinuous, single-channel ‘meandering’ rivers and straighter, multi-channel ‘braided’ rivers is not clearcut (Ferguson, 1984) and may be impossible in the absence of a complex vegetation cover, though the late Silurian-early Devonian may mark the onset of small meandering channels (Gibling and Davies, 2012).

The overlying Castle of Cowie member consists of about 74 metres of red medium-grained tabular, and trough cross-bedded and planar bedded sandstones and pebbly sandstones with intraformational red siltstone clasts, interbedded with very minor red siltstones (

Figure 4E, F, 6). The lower trough cross-bedded units form in migrating channels, while the dominantly tabular cross beds above indicate downstream-migrating sand flats (Miall, 2014; Li et al., 2023). Minor trough and parallel laminated sands and mudstones/siltstones, in fining upwards cycles show relatively uniform southwesterly paleocurrents (Gillen and Trewin, 1986; Hartley and Leleu, 2015).

The absence of paleosols, partly attributable to the lack of an integrated plant cover anywhere outside water-saturated environments (Retallack, 1992, 2022; Gibling and Davies, 2012), and red siltstones are comparable with the semi-arid unconfined chaotic, vertical accretion braided stream networks of central Australia with overbank fines accumulating during major floods (Williams, 1971; Nansen et al., 1986; Pickup, 1991; Bourke, 1994). Some beds, of uncertain stratigraphic position, have a low diversity trace fossil assemblage assigned to the Pridoli-Lochkovian (Shillito and Davies, 2017) (

Figure 5B).

The Castle of Cowie sandstones (#5,12,13) are slightly more feldspathic sublithic sandstones than the basal beds with greater amounts of metasandstone grains, very low plagioclase/K-feldspar ratios, variable Qm/Qp ratios and biotite. The slight differences indicate somewhat lower chemical weathering due to drier conditions in the Castle of Cowie sandstones.

The overlying clastic sediments, up to 1800-metre-thick, are a combination of dominant tabular and trough cross-bedded lithic, occasionally pebbly, sandstones with abundant mudstone clasts (

Figure 7). These higher sediments are only exposed during low tides and have not had a complete detailed section measured. Their brownish to greenish colours indicate a return to more humid conditions similar to, but not as wet as, the basal beds with lake deposits, in unconfined chaotic, vertical accretion braided stream networks, marking a return to Platte-type braided stream deposition. Petrographically the upper sandstones (#2-4) are more lithic sandstones dominated by acid to intermediate volcanic grains, variable but mostly few metasandstone grains, with moderate plagioclase/K-feldspar ratios, low Qm/Qp ratios and relatively high plagioclase and biotite contents, indicating less chemical weathering (

Figure 3).

Figure 7.

Northern block; upper Cowie Formation. A section C,

Figure 2: NO88098685 (based on McKellar, 2017); paleocurrents from Gillen and Trewin (1986).

Figure 7.

Northern block; upper Cowie Formation. A section C,

Figure 2: NO88098685 (based on McKellar, 2017); paleocurrents from Gillen and Trewin (1986).

3.1.2. Fossils

The low diversity trace fossil assemblage from the Castle of Cowie Member is more diverse than that from other continental deposits of middle Silurian age, and shares greater similarity with worldwide Pridoli to Devonian-aged ichnofaunas (Shillito and Davies, 2017).

Land plant spores were found in two horizons in the northern block: i) a grey sandy siltstone (NO88290/87036) from the lowermost mudstones and siltstones; and ii) a large cobble (20cm in diameter) of dark grey siltstone within a sandstone at the base of the Castle of Cowie Member (NO88420/87136) (Wellman et al., 2023). The latter only dates the cobble, NOT the sandstone. Its large size in fine-grained sandstone, without other intraclasts or extraclasts, indicates that it was very locally derived since such a large siltstone clast is hydrodynamically incompatible with the enclosing sandstones, whether it was near-contemporaneous with the sandstone or older. The fact that it survived transport suggest that it was at least partly indurated. Individual sample taxa lists for the two samples were not published separately, presumably on the assumption that they belong to the same floras and no taxonomic ranges were given for individual species (Wellman et al., 2023).

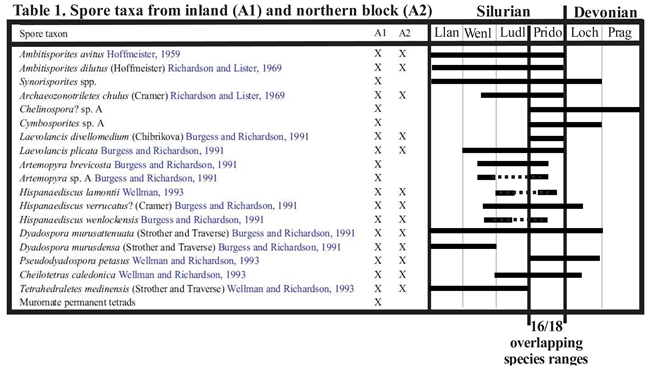

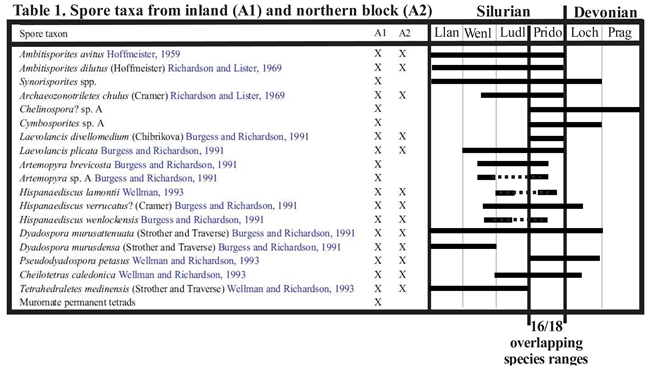

Range charts are the critical limiting factor for biostratigraphic resolution which requires detailed local range charts that resolve the first and last appearances of numerous fossil species (Webster et al., 2008). Using the individual species ranges from White’s (2008) palynodata compilation (current to 2006), however, and accepting only those species ranges in marine strata which can be correlated with the standard stages, gives the ranges of the individual species in the inland (A1) and northern block (A2) as shown on Table 1.

|

These do not define a Wenlockian assemblage: 16 out of 18, overlap in the Pridoli. Dyadospora murusdensa and Tetrahedraletes medinsis, range only up to the end Wenlock and end Ludlow respectively, but could be reworked older fossils (Stanley, 1966). Hispanaediscus lamonitii is found in both the Ludlovian (Burgess and Richardson, 1995) and Pridoli (Rubinstein and Steemans, 2002) but not in between; similarly, Artemopyra sp. A Burgess and Richardson 1991, is found in the upper Wenlock (Burgess and Richardson, 1991) and lower Pridoli (Wetherall et al., 1999) of the Welsh borders. Hispanaediscus wenlockensis is found not only in the upper Wenlock and Ludlow (Rubinstein and Steemans, 2002) but also in the lower Pridoli (Steemans et al., 1996). The standard biostratigraphic overlapping range method firmly indicates a Pridoli age for both assemblages, and none of the species are exclusively Wenlock.

3.1.3. Detrital zircon U/Pb dates

The detrital zircon laser ablation-sector field-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (LA–SF–ICP–MS) U-Pb dates cited by Wellman et al. (2023) come from McKellar (2017) and McKellar et al. (2020) with 2σ errors. Using McKellar’s (2017) grid reference locations on a stratigraphic section, the analyzed zircons came from three samples from the lower beds in the northern block, and one from the Carron Formation in the Stonehaven Harbour section, far to the south (McKellar et al., 2020, Figure 14). Unfortunately, detailed analytical data for the individual zircons (e.g., % discordances, raw U and Pb values) are given in neither McKellar (2017) nor McKellar et al. (2020), only probability density plots for lumped U-Pb data. without making available the tables or spreadsheets expected in geochronological studies (Horstwood et al., 2016). Such details are necessary because” few, if any, scientific disciplines publish numerical data that are accepted by nonexperts and propagated through the literature as extensively as geochronology”, and, “quantifying random and systematic sources of instrumental and geological uncertainty is vital, and requires transparency in methodology, data reduction, and reporting” (Schoene et al., 2013).

Assuming a conventional 10% discordance cut-off was used for acceptable dates, the youngest zircons in the four McKellar et al. (2020) samples (with >100 grains per sample), in supposed stratigraphic order, are 439 ± 4, 478 ± 4, 470 ± 7 (basal “Cowie”), and 430 ± 6 Ma (Carron Sandstone Formation. The 439 ± 4 Ma (Llandoverian) date is from the lowermost northern block sediments (petrographic sample # 11), while the 430 ± 6 Ma (Wenlock) date is from the isolated type Carron Sandstone outcrop in Stonehaven Harbour (petrographic samples #28). The two older dates in the strata in between indicate that no near contemporary igneous rocks were being sourced at that time.

Detrital zircon dates give only a maximum, not necessarily true, depositional age, and need careful evaluation (Sharman et al., 2020) and understanding of various U/Pb methods and their significance (Schoene, et al., 2013; Garza et al., 2023). Thus, a sediment cannot be any older than the youngest thing in it, though it can be younger (Dickinson and Gehrels, 2009). The Llandoverian date for the basal northern block sediments is compatible with both the Wenlock and Pridoli alternative ages from the spores, though we consider the Pridoli age more accurate.

3.1.4. Summary

The northern block section therefore shows basal pediment breccias overlain by SE-flowing low gradient braided stream deposits passing up into anastomosing streams under wetter climate of Pridoli age, succeeded by SW-flowing braided streams of Pridoli-Lochkovian age with variable wetter and drier conditions: all of which have dominantly distant acid volcanic sources. There is no sign any topographic effect on sedimentation by the adjacent Highland Boundary fault (McKellar, 2017).

3.2. Southern block

3.2.1. Sediments

The southern block has a lower sandstone-dominated section, overlain by the Cowie Harbour Conglomerate Member with volcanic clasts, and the Cowie Harbour Siltstone Member with fish bed, overlain by sandstones correlated with the Carron Sandstone Formation, whose type section is in Stonehaven Harbour, 2 km to the south across faulted and unexposed terrain (Figs. 1, 7).

The lower beds are similar in character, and may belong to, the same stratigraphic unit as those at the top of the northern section, but displaced westwards by right-lateral movement on the Cowie Harbour fault; which displacement is also indicated by the small right-lateral shears next to the fault in the southern block (MacGregor, 1996) (

Figure 2 inset). Two of three basal sandstones (#1,14,15) are extreme volcaniclastic lithic sandstones. with no metamorphic or sedimentary rock grains, moderate Plagioclase/K-feldspar ratios, high Qm/Qp ratios and relatively high plagioclase and variable biotite contents; indicating predominantly physical weathering of an acid- to intermediate- volcanic source. They are distinct from any other samples in the succession.

The overlying Cowie Harbour Conglomerate Member consists of a 6-metre-thick unit of two thick beds of conglomerate with rounded clasts of andesite and rhyolite, mostly around 10 cm in diameter but some of boulder size (Gillen and Trewin, 1986) supplied by local outcrops to predominantly well-sorted conglomerates with rounded, more distantly travelled pebbles.

Figure 7.

Southern section; Brown and Green Sandstones to Cowie Harbour Siltstone Member, section C,

Figure 2: starts at NO88048663 (after Shillito and Davies, 2017); paleocurrents from Hartley and Leleu (2015).

Figure 7.

Southern section; Brown and Green Sandstones to Cowie Harbour Siltstone Member, section C,

Figure 2: starts at NO88048663 (after Shillito and Davies, 2017); paleocurrents from Hartley and Leleu (2015).

The Cowie Harbour Siltstone Member consists of tabular- to ripple drift cross-laminated fine- to medium grained sandstones interbedded and passing up into laminated siltstones and mudstones which bear the Cowie Harbour fish bed (Figure 7). This latter fine-grained unit is thicker than any other such unit in the Stonehaven Group. It marks a relatively long-lived lake depositional environment as shown by the scattered plant remains in the thicker siltstones and mudstones, as well as by the unique Fish bed (Campbell, 1913)

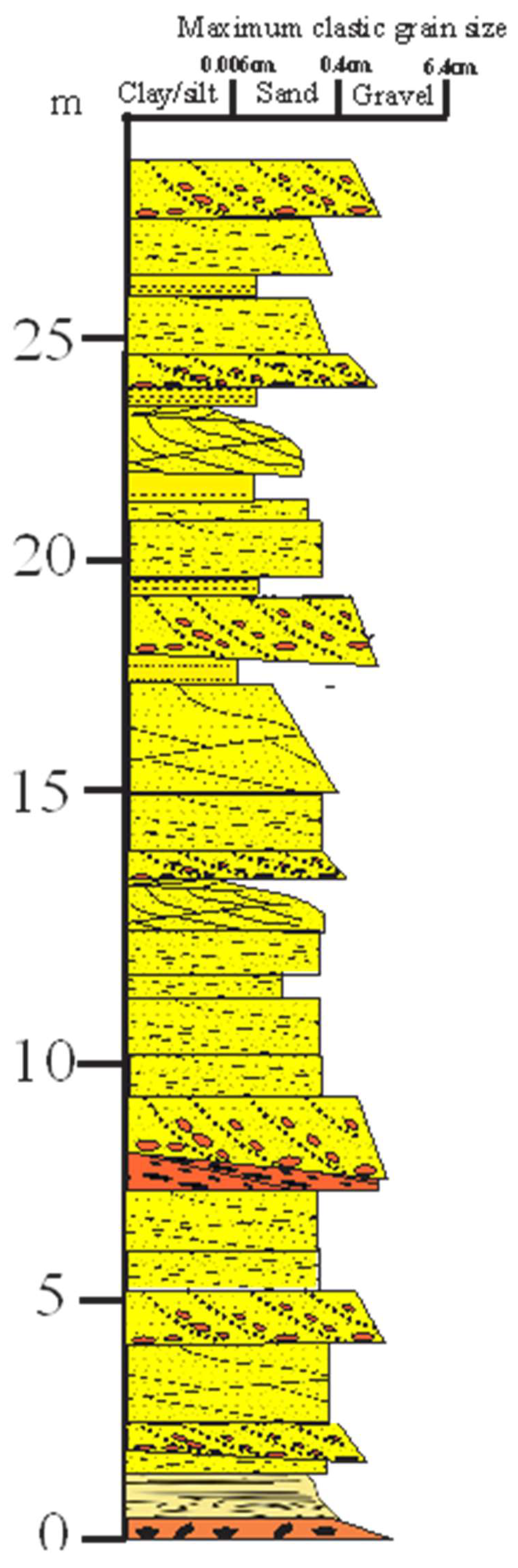

The overlying ‘Carron Sandstone formation’ in this block consists of a thick sequence of red, fine- to coarse-grained, trough cross-bedded and horizontally-laminated locally pebbly lithic sandstone with lenses of conglomerate, analogous to the type Carron Sandstone Formation at Stonehaven Harbour to the south, but with distinct though overlapping petrologies. This “Carron Sandstone Formation” has quartzo-feldspathic sublithic sandstones, with moderate plagioclase/K-feldspar ratios, moderate Qm/Qp ratios (~2.5), relatively high plagioclase (>14% of grains) and moderate biotite contents (

Figure 3, Supplementary Table T1), indicating greater chemical weathering and/or recycling of sediments. At Stonehaven harbour, the type Carron Formation consists of red fine- to very coarse-grained trough-festoon-cross bedded and tabular- and horizontally-laminated lithic pebbly sandstone and sandstone, with thin quartzite-pebble beds and fine- to medium- grained planar laminated micaceous sandstone (McKellar and Hartley, 2021) (

Figure 8). These river channel deposits record dune migration at the base of channels and migration of transverse bars in a downstream accreting semi-arid to arid braided fluvial system (Miall, 2014; Bridge & Lunt, 2004; Allen, 2007; Fielding et al., 2011; Colombera et al., 2013).

The type Carron Sandstones are petrologically distinct from the “Carron Sandstones” int the southern block, being volcaniclastic lithic sandstones, with low to high plagioclase/K-feldspar ratios, very variable Qm/Qp ratios, moderate to high plagioclase (>14% of grains) and very variable biotite contents (

Figure 3, Supplementary Table T1). This limited sandstone petrography indicates distinct sources for the “Cowie” sandstones and “Carron” sandstones in the two areas.

Since the paleocurrents in both sections indicate a dominant palaeoflow direction towards the west to southwest (Hartley and Leleu, 2015; McKellar, 2017) (Figs. 5,6,7), possibly different sources were sequentially provided by strike-slip faulting to the east during sedimentation (Dewey and Strachan, 2003).

The variable constituents indicate variable weathering processes, in contrast to the “Carron Sandstones” of the southern block. Though these are not correlatable units, the overlap of sublithic sandstone compositions suggest that the type Carron Sandstones may be higher sedimentary strata of the southern block “Carron Sandstones”.

3.2.2. Fossils

Fossils occur only in the Cowie Harbour Siltstone member, with identifiable taxa only in the Fish Bed.

Only indeterminate plant remains and no spore fossils are recorded, even from the apparently suitable Cowie Harbour Fish bed (Campbell, 1913; Marshall, 1991; Wellman, 1993)

The fauna of the fish bed has, however, been studied for many years. Initially considered Downtonian (Pridoli), based on comparisons with fish-arthropod biotas elsewhere (Campbell 1913; Westoll 1945, 1951), Wellman et al. (2023) assigned it to the mid-Silurian, based on correlation with spore-bearing sediments in the northern block, and supposedly more diverse and evolutionarily ‘advanced’ Lochkovian faunas elsewhere. In view of these divergent interpretations, a detailed taxonomic evaluation and comparison is required.

All the fish taxa in the Cowie Harbour fish bed range into the Lower Devonian and are not exclusively Silurian. Hemiteleaspis heintzi Westoll 1945 is now regarded as only an indeterminable species of Hemicyclaspis (Ritchie, 1967; Heintz, 1974) which is a Pridoli to Devonian form (Blieck and Elliot, 2017). Traquairaspis campbelli Traquair 1912 is found only at Cowie, where a single specimen of a dorsal plate defined the genus (Dineley. 1964). T. campbelli is one of only two species in the Traquairaspidae, as Tarrant (1991) removed all the Welsh Border species to other genera. The second Traquairaspis species is found in Pridoli sediments of northern Canada, Poland and Russia (Elliot, 1984; Dec, 2020; Talimaa,1995). The birkeniid anapsid, Cowielepis richiei Blom 2008, is confined to the Cowie Fish bed and Blom attributed it to the mid-Silurian only because the Cowie Fish bed was then so assigned (Blom, 2008). Birkenids range into the Lochkovian and are not exclusively Silurian (Blom et al., 2002). The vertebrate fauna cannot therefore be assigned to any marine-based biostratigraphic unit. The agnathan taxa have non-overlapping ranges from Ludfordian to Lochkovian, and cannot therefore be used for a vertebrate biostratigraphy applicable to the Cowie assemblage (Davies et al., 2005)

The arthropods, Nanahughmilleria norvegica Kiaer 1911, was assigned by Kiaer (1911) to the Downtonian or uppermost Ludfordian (Kjellesvig-Waering, 1961), but other Nanahughmilleria species range into the Devonian (Tetlie, 2007). The original record of N. norvegica comes from the Ludfordian lower Sundvollen Formation (Kiaer, 1911; Davies et al., 2005). Dictyocaris is the most abundant fossil in the Fish bed (also called the Dictyocaris bed), and is a long-ranging fossil found in many suitable facies from Llandoverian to Pridoli (Størmer, 1935). Dictyocaris occurs only as abundant, frequently large thin carbonized fragments in strata bearing well-preserved articulated eurypterids. Its apparent originally cone-shaped morphology was first compared with the living liverwort Marchantia, but was subsequently attributed to a cephalaspid fish or an arthropod (Campbell, 1913; Störmer,1935): it is more likely to be a plant than a fish or an arthropod (O’Connell, 1916; Ritchie, 1963), but is still enigmatic (Van der Brugghen, 1995: see discussion in Brookfield, 2024). The three fossil millipedes Cowiedesmus eroticopodus Wilson &Anderson, Albadesmus almondi Wilson & Anderson, and Pneumodesmus newmani Wilson & Anderson, have no stratigraphic value, except that the assemblage is more diverse than any other Silurian occurrence including the single millipede species in the Kerrera fish bed in Argyll, Kampecaris obanensis, dated 425.5 ± 4.5 Ma (Gorstonian) (Brookfield et al, 2020, 2024).

3.2.3. Detrital zircon U/Pb dates

The detrital zircon dates in the southern section with the fish bed, are discussed in detail in Suarez et al. (2017). They are carefully evaluated U-Pb zircon LA-ICP-MS dates, with standard 2σ errors, of 413.7±4.1 Ma (% discordance 0.72) from the Green Tuff below and 414.3±7.1 Ma (%discordance 0.65) from a sandstone above the fish bed (Suarez et al., 2017). These are identical within error, and consistent with a maximum Pridoli-Lochkovian age assigned. Attempts to explain these dates by appealing to lead loss is contradicted by the low % discordance, which in any case would make them only slightly older (Vermeesch, 2021). Thus, assuming all the measured 207Pb is common, and that the concordia discordance is due to simple Pb loss, then the low discordance dates become 413.6±4.4 Ma and of 414.0±7.3 Ma, which are Lochkovian.

3.2.4. Summary

The southern block strata show an upward change from semi-arid W-flowing braded streams with, unlike the northern block, beds of locally derived basement clasts (indicting volcanics exposed by contemporary faulting, passing up into thicker wetter climate anastomosing streams with marsh and lake beds, followed by coarse locally derived semi-arid braided stream deposits.

4. Conclusions

The northern and southern block strata at Cowie show distinctly different sedimentary successions with fossils indicating that both were deposited in Pridoli to Lochkovian times. The sedimentology suggests that there were two relatively wet periods represented by brownish to greenish anastomosing channel and overbank deposits, with nearby vascular plant communities, during the Pridoli-Lochkovian, separated in time by drier braided stream deposits.

The late Wenlock age inferred by Wellmann et al. (2023) for the Cowie Harbour Fish bed can only apply to the lowermost strata of the northern structural block and to some disconnected tectonically isolated exposures along the Highland boundary fault kilometers away across unexposed terrain, and these may in fact be Pridoli. The Pridoli-Lochkovian age for the Cowie Harbour Fish bed is based on vertebrate faunas and maximum detrital zircon dates from the actual strata bearing the fish bed. The various lines of evidence, lithostratigraphic, sedimentological, biostratigraphic, and radiometric clearly indicate that the Cowie Fish bed is Pridoli to possibly early Lochkovian. Using spores or detrital zircon ages to suggest a Wenlock age for the Cowie Harbour Fish bed only works by accepting a spurious lithological correlation of the southern block strata with the dissimilar spore-bearing strata to the north of the Cowie Harbour fault, and disregarding the known ranges of both the vertebrate fossils and the spore species.

Lastly, if the basal Cowie sediments of the northern block are Pridoli, then the Old Red Sandstone continental sedimentation began in the Pridoli and not in the Wenlock in the northern Midland valley, and is contemporary with the basal Old Red Sandstone in the Welsh Borders (Kendall, 2017). This apparently synchronous onset of lowland desert conditions in the United Kingdon may reflect the moderate to rapid warming and development of supergreenhouse conditions during the Přídolí in northern Gondwanaland (Lehnert et al., 2013).

5. Future work

More precise dates for the various Stonehaven units (and beyond) could be obtained by TIMS U-Pb analysis of the youngest of the already LA-ICP-MS dated near-concordant zircons. An objective procedure would be to analyze the youngest concordant zircon grains from many (cheap) imprecise LA-ICP-MS dated ones, with (expensive) TIMS methods. As demonstrated by Garza et al. (2023) and Howard et al. (2024), while LA-ICP-MS provides a useful preliminary approach for dating, its accuracy and precision are generally lower compared to other methods. Specifically, LA-ICP-MS often yields younger zircon U-Pb dates than those obtained with CA-ID-TIMS, primarily due to undetectable cryptic Pb loss and systematic biases such as matrix mismatch effects. These issues highlight the necessity for future analyses using the more precise CA-ID-TIMS technique. We do not have TIMS facilities in Austin, but if anyone would like to do this method on our dated zircons, we would be happy to provide them.

6. Acknowledgements

We thank Susan Turner for comments on the vertebrate faunas.

Author contributions

MEB: conceptualization (lead), investigation (lead), writing – original draft (lead), writing – review and editing (lead); EJC: formal analysis (supporting), investigation (supporting), methodology (lead), writing – review and editing (supporting)HKG: methodology (supporting), writing – review and editing (supporting)

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Data availability statement

All data analyzed during this study are in Suarez et al. (2017) and McKellar (2017)

Funding information:

Supporting funds for field work and analysis were provided to EJC and HKG by the Jackson School of Geosciemces.

References

- Allen, J.R.L. A quantitative model of grain size and sedimentary structures in lateral deposit. Geol. J. 2007, 7, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.G.C. The Geology of the Highland Border: Stonehaven to Arran. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 1947, 61, 479–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, R.T.; Marshall, J.A.E. Da Silva, A. -C., Agterberg, F.P., Gradstein, F.M., Ogg, J.G. The Devonian Period, In: Gradstein, F.M., Ogg, J.G., Schmitz, M.D., Ogg, G.M. Geologic Time Scale 2020, 2020, Chapter 22, Elsevier, Amsterdam. P. 733–810, doiorg/101016/B978. [Google Scholar]

- Blieck, A.; Elliott, D.K. Pteraspidomorphs (Vertebrata), the Old Red Sandstone, and the special case of the Brecon Beacons National Park, Wales, U. K. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association 2017, 128, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, H. A new anaspid fish from the Middle Silurian Cowie Harbour Fish Bed of Stonehaven, Scotland," J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2008, 28, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, H.; Märss, T.; Miller, C. Silurian and earliest Devonian birkeniid anaspids from the Northern Hemisphere. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. : Earth Sci. 2002, 92, 263–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, M.C. 1994. Cyclical Construction and Destruction of Flood Dominated Semiarid Central Australia. In Olive, L.J., Loughlan, R. and Kesby, J.A. (Eds). Variability in Stream Erosion and Sediment Transport, International Association of Hydrological Sciences Publication 224, 113–123.

- Bridge, J.S.; Lunt, I.A. Depositional models for braided rivers. In G. H. Sambrook Smith, J.L. Best, C.S. Bristow, & G. E. Petts (Eds.), Braided Rivers (pp. 11–50). Blackwell: IAS Special Publications, 2004.

- Brookfield, M.E. The Life and Death of Jamoytius kerwoodi White; A Silurian Jawless Nektonic Herbivore? Foss. Stud. 2024, 2, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookfield, M.E.; Catlos, E.J.; Suarez, S.E. Myriapod divergence times differ between molecular clock and fossil evidence: U/Pb zircon ages of the earliest fossil millipede-bearing sediments and their significance. Hist. Biol. 2020, 33, 2014–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookfield, M.E.; Catlos, E.J.; Garca, H.K. The oldest ‘millipede’-plant association? Age, paleoenvironments and sources of the Silurian Lake sediments at Kerrera, Argyll and Bute, Scotland. Hist. Biol. 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, N.D.; Richardson, J.B. Silurian cryptospores and miospores from the type Wenlock area, Shropshire, England. Palaeontology 1991, 34, 601–628. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, N.D.; Richardson, J.B. Late Wenlock to Early Přídolí cryptospores and miospores from South and southwest Wales, Great Britain. Palaeontogr. B 1995, 236, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, R. The geology of northeastern Kincardineshire. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 1913, 48, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombera, L.; Mountney, N.P.; McCaffrey, W.D. A quantitative approach to fluvial facies models: Methods and example results. Sedimentology 2013, 60, 1526–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, N.S.; Turnery, P.; Sansom, I.J. A revised stratigraphy of the Ringerike Group (Upper Silurian, Oslo, Norway). Nor. J. Geol. 2005, 85, 193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Dec, M. Traquairaspididae and Cyathaspididae (Heterostraci) from the Lower Devonian of Poland. Ann. De Paléontologie 2020, 106, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J.F.; Strachan, R.A. Changing Silurian–Devonian relative plate motion in the Caledonides: sinistral transpression to sinistral transtension. J. Geol. Soc. 2003, 160, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, W.R.; Gehrels, G.E. Use of U-Pb ages of detrital zircons to infer maximum depositional ages of strata: a test against a Colorado Plateau Mesozoic database. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2009, 288, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dineley, D.L. New specimens of Traquairaspis from Canada. Palaeontology 1964, 7, 210–219. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, D.K. Siluro-Devonian fish biostratigraphy of the Canadian arctic islands. Proc. Linn. Soc. New South Wales 1984, 107, 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, R.I. The Threshold between Meandering and Braiding. In: Smith, K.V.H. (eds) Channels and Channel Control Structures. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. 1984, 749-763. [CrossRef]

- Fielding, C.R.; Allen, J.P.; Alexander, J.; Gibling, M.R.; Rygel, M.C.; Calder, J.H. Fluvial Systems and their Deposits in Hot, Seasonal Semiarid and Subhumid Settings: Modern and Ancient Examples. In: S. K. Davidson, S. Leleu; C. P. North (eds.), From River to Rock Record: The preservation of fluvial sediments and their subsequent interpretation. Soc. Sediment. Geol. Spec. Publ. 2011, 97, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finotello, A.; Ielpi, A.; Lapôtre, M.G.A.; Lazarus, E.D.; Ghinassi, M.; Carniello, L.; Favaro, S.; Tognin, D.; D’Alpaos, A. Vegetation enhances curvature-driven dynamics in meandering rivers. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garza, H.K.; Catlos, E.J.; Chamberlain, K.R.; Suarez, S.E.; Brookfield, M.E.; Stockli, D.F.; Batchelor, R.A. † How old is the Ordovician–Silurian boundary at Dob’s Linn, Scotland? Integrating LA-ICP-MS and CAID-TIMS U-Pb zircon dates. Geol. Mag. 2023, 160, 1775–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibling, M.R.; Davies, N.S. Palaeozoic landscapes shaped by plant evolution. Nat. Geosci. 2012, 5, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillen, G.; Trewin, N.H. Dunnottar to Stonehaven and the Highland Boundary Fault. In Trewin, N.H., Kneller, B.C. and Gillen, C. (eds), Excursion Guide to the Geology of the Aberdeen Area. Scottish Academic Press, Edinburgh. 1986; pp. 265-273.

- Hartley, A.J.; Leleu, S. Sedimentological constraints on the late Silurian history of the Highland Boundary Fault, Scotland: implications for Midland Valley Basin development. J. Geol. Soc. 2015, 172, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintz, A. Additional remarks about Hemicyclaspis from Jeløya, southern Norway. Nor. Geol. Tidsskr. 1974, 54, 375–384. [Google Scholar]

- Horstwood, M.S.A.; Košler, J.; Gehrels, G.; Jackson, S.E.; McLean, N.M.; Paton, C.; Pearson, N.J.; Sircombe, K.; Sylvester, P.; Vermeesch, P.; et al. Community-Derived Standards for LA-ICP-MS U-(Th-)Pb Geochronology – Uncertainty Propagation, Age Interpretation and Data Reporting. Geostand. Geoanalytical Res. 2016, 40, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, B.L.; Sharman, G.R.; Crowley, J.L.; Wersan, E.R. The leaky chronometer: Evidence for systematic cryptic Pb loss in laser ablation U-Pb dating of zircon relative to CA-TIMS. Terra Nova, 2024, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Kendall, R.S. The Old Red Sandstone of Britain and Ireland: a review. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 2017, 128, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiaer J A new Downtonian fauna in the Sandstone Series of the Kristiania area: a preliminary report Vidensabers selskrab Skrifter, I. Matematisk-naturvidenskabelig klasse, Kristiania, 1911, 1911, 1–22.

- Kjellesvig-Waering, E.N. The Silurian Eurypterida of the Welsh Borderland". J. Paleontol. 1961, 35, 789–835. [Google Scholar]

- Lehnert, O.; Fryda, J.; Joachimski, M.; Meinhold, G.; Calner, M.; Čáp, P. 2013. The 'Přídolí hothouse', a trigger of faunal overturns across the latest Silurian Transgrediens Bioevent. In: Lindskog A., Mehlqvist K., editors. Proceedings of the 3rd IGCP 591, Annual Meeting; Lund, Sweden. ; Lund, Sweden: Lund University; p. 175–176. 9–19 June.

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Gao, H.; Liu, F.; Xing, W.; Zhang, C.; Qiao, Q.; Lei, X. Fluvial Responses to Late Quaternary Climate Change in a Humid and Semi-Humid Transitional Area: Insights from the Upper Huaihe River, Eastern China. Water 2023, 15, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, A.R. 1996. Fife and Angus Geology: an excursion guide. Excursion 1. Arbroath, Crawton and Stonehaven. Third edition. The Pentland Press, Edinburgh.

- Makaske, B. Anastomosing rivers: a review of their classification, origin and sedimentary products. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2001, 53, 149–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.E.A. Palynology of the Stonehaven Group, Scotland: evidence for a mid-Silurian age and its geological implications. Geol. Mag. 1991, 128, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, L.; Shipton, Z.K.; Lunn, R.J.; Andrews, B.; Raub, T.D.; Boyce, A.J. Detailed internal structure and along-strike variability of the core of a plate boundary fault: the Highland Boundary fault, Scotland. J. Geol. Soc. 2020, 177, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKellar, Z. 2017. Sedimentology of the Lower Old Red Sandstone of the Northern midland Valley Basin and Grampian Outliers, Scotland: Implications for Post-Orogenic Basin Development. thesis, University of Aberdeen, 303p.

- McKellar, Z.; Hartley, A.J. Caledonian foreland basin sedimentation: A new depositional model for the Upper Silurian-Lower Devonian Lower Old Red Sandstone of the Midland Valley Basin, Scotland. Basin Res. 2021, 33, 754–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKellar, Z.; Hartley, A.J.; Morton, A.; Frei, D. A Multidisciplinary Approach to Sediment Provenance Analysis of the Late Silurian-Devonian Lower Old Red Sandstone succession, Northern Midland Valley Basin, Scotland. J. Geol. Soc. 2020, 177, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlqvist, K.; Larsson, K.; Vajda, V. Linking upper Silurian terrestrial and marine successions-palynological study from Skåne, Sweden. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2014, 202, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchin, M.J.; Sadler, P.M.; Cramer BD 2020 The Silurian period In: Gradstein, F.M.; Ogg, J.G.; Schmitz, M.D.; Ogg, G.M. Geologic Time Scale 2020, Chapter 22, Elsevier, Amsterdam. p. 695-732. [CrossRef]

- Miall, A.D. 2014. Fluvial depositional systems. Springer International, Berlin. 316p.

- Nanson, G.G.; Rust, B.R.; Taylor, G. Coexistent mud braids and anastomosing channel in an arid-zone river: Cooper Creek, central Australia. Geology 1986, 14, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, M. The habitat of the Eurypterida. Bulletin of the Buffalo Scoiety of Natural History 1916, 11, 277p. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, E.R. 2007. Petrology and provenance of the Siluro-Devonian (Old Red Sandstone facies) sedimentary rocks of the Midland Valley, Scotland. British Geological Survey Internal Report, IR/07/040, 65pp.

- Pickup, G. Event frequency and landscape stability on the flood plain systems of arid central Australia. Quatern. Sci. Rev. 1991, 10, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retallack, G.J. Paleozoic paleosols. Ch 21. In: I.P. Martini, W. Chesworth (Eds). Developments in Earth Surface Processes. Elsevier, Amsterdam 1992, 2, 543–564. [CrossRef]

- Retallack, G.J. Ordovician-Devonian lichen canopies before evolution of woody trees. Gondwana Res. 2022, 106, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, A. 1963. Palaeontological studies on Scottish Silurian fish beds. Upublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Edinburgh.170pp.

- Ritchie, A. Ateleaspis tessellata Traquair, a non-cornate Cephalaspid from the Upper Silurian of Scotland. J. Linn. Soc. (Zool. ) 1967, 47, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, C.V.; Steemans, P. Miospore assemblages from the Silurian–Devonian boundary, in borehole A1-61, Ghadamis Basin, Libya. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2002, 118, 397–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, C.V.; et al. Miospore assemblages from the Silurian-Devonian boundary, in Borehole A1-61, Ghadamis Basin, Libya. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2002, 118, 397–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoene, B.; et al. Precision and Accuracy in Geochronology. Elements 2013, 9, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharman, G.R.; Matthew, A.; Malkowsi, A. Needles in a haystack: Detrital zircon U/Pb ages and the maximum depositional age of modern global sediment. Earth-Science Reviews. 2020; 203, 103109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shillito, A.P.; Davies, N.S. Archetypically Siluro-Devonian ichnofauna in the Cowie Formation, Scotland: implications for the myriapod fossil record and Highland Boundary Fault Movement. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 2017, 128, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.D. Transverse bars and braiding in the lower Platte River, Nebraska: Geological Society of America Bulletin 1971, 82, 3407–3420.

- Stanley, E.A. The problem of reworked pollen and spores in marine sediments. Mar. Geol. 1966, 4, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steemans, P.; Le, H.é.r.i.s.s.é.; A; Bozdogan, N. Ordovician and Silurian cryptospores and miospores from southeastern Turkey. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 1996, 93, 35–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Störmer, L. Dictyocaris salter, a large crustacean from the Upper Silunan and. Downtownian. Nor. Geol. Tidsskr. 1935, 15, 267–298. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez, S.E.; Brookfield, M.E.; Catlos, E.J.; Stöckli, D.F. A U-Pb zircon age constraint on the oldest-recorded air-breathing land animal. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0179262–10p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talimaa, V. 1995. Vertebrate complexes in the heterofacial Lower Devonian deposits of Timan-Pechora Province. In TURNER, S. (ed.). UNESCO-I.U.G.S. IGCP No. 328. Palaeozoic microvertebrate biochronology and global marine/non-marine correlation (1991-1995) state of research. Ichthyolith Issues, Special Publication 1. J. Zidek Serv, Socorro, New Mexico, 72 pp.

- Tarrant, P.R. The ostracoderm Phialaspis from the Lower Devonian of the Welsh Borderland and South Wales. Palaeontology 1991, 34, 399–438. [Google Scholar]

- Tetlie, O.E. Distribution and dispersal history of Eurypterida (Chelicerata). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2007, 252, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Brugghen Dictyocaris, een enigmatisch fossiel uit het Silur. Grondboor em Hamuir, 1995, 1, 18–22.

- Vermeesch, P. On the treatment of discordant detrital zircon U–Pb data. Geochronology 2021, 3, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.A. Method for Estimating the Hydrodynamic Values of Anastomosing Rivers: The Expression of Channel Morphological Parameters. Water 2024, 16, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, M.; Sadler, P.; Kooser, M.; Fowler, E. Combining stratigraphic sections and museum collections to increase biostratigraphic resolution. In: Harries, P.J. (ed.), High-Resolution Approaches in Stratigraphic Paleontology. Springer, Berlin, 2008; pp.95-128. [CrossRef]

- Wellman, C.H. A land plant microfossil assemblage of Mid Silurian age from the Stonehaven Group, Scotland. J. Micropalaeontology 1993, 12, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, C.H.; Lopes, G.; McKellar, Z.; Hartley, A. Age of the basal ‘Lower Old Red Sandstone’ Stonehaven Group of Scotland: The oldest reported air-breathing land animal is Silurian (late Wenlock) in age. J. Geol. Soc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westoll, T.S. A new cephalaspid fish from the Downtonian of Scotland, with notes on the structure and classification of ostracoderms. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 1945, 61, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westoll, T.S. The vertebrate-bearing strata of Scotland. Rep. 18th Int. Geol. Congr. 1951, 2, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherall, P.M.; Dorning, K.; Wellman, C.H. Palynology, biostratigraphy, and depositional environments around the Ludlow-Pridoli boundary at Woodbury Quarry, Herefordshire, England. Boll. Della Soc. Paleontol. Ital. 1999, 38, 397–404. [Google Scholar]

- White, J. 2008. Palynodata Datafile: 2006 version. Geological Survey of Canada Open File Report 5793. (https://paleobotany.ru/palynodata).

- Williams, G.E. Flood deposits of the sand-bed ephemeral streams of central Australia. Sedimentology 1971, 17, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, H.; Anderson, L. Morphology and taxonomy of Paleozoic millipedes (Diplopoda: Chilognatha: Archipolypoda) from Scotland. J. Paleontol. 2004, 78, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).