1. Introduction

Integrated photonics represents an unmatched opportunity for implementing a large variety of programmable functions [

1,

2] and it may be expected in the next future a large-scale implementation of fabrication facilities for Photonics Integrated Circuits (PICs), targeting an economy of scale comparable to the one attained by ASICs in microelectronics. There is a great expectation for this roadmap [

3] aiming to standardization of the overall process, from design-simulation to the fabrication-packaging steps [

4]. Great interest has been posed, among others, in the application of photonic switching structures [

5], aiming to the development of programmable devices for optical data processing [

6]. An interesting approach recently reported, used nanostructured material geometry to create an arbitrary distribution of the refractive index values, permitting power splitting with arbitrary input and output directions [

7]. The combination of Deep Artificial Neural Network with the optimized design of a local perturbation for the refractive index in nanophotonic structures, has opened a path toward the fabrication of universal optical components [

8]. Considering that while the overmentioned examples are based on a lithographic design to produce a device associated to a specific function, there is also a large investment in the scientific community in developing proper layouts for programmable integrated circuits (PICs), compatible with standard CMOS fabrication technology and capable of addressing a wide range of applications by providing higher-level platform for prototyping novel optical functionalities without the need for custom chip fabrication [

9]. PICs manipulation of light flow is based on a tunable control operated on switching devices, over an array of gates connected by waveguides. Programming functionality allows the implementation of a wide set of logical functions, leading to the conception of a general-purpose photonic processor to leverage the unique properties of photonics in terms of ultra-high bandwidth, high-speed operation, and low power consumption [

10].

The switching operation in the devices proposed and described in literature are typically based on phase shifting control, operated on a set of light couplers conveniently distributed and mutually interconnected. The phase shifting function is generally operated by thermo-optical effect [

11]. For reducing the power requirements of these systems, novel approaches using liquid crystals [

12] and/or MEMS [

13] structures have been proposed as an alternative to heaters, in line with the general recommendations for the next generation of energy-efficient smart edge devices.

More recently, externally induced material phase changes have also been demonstrated, allowing reconfigurable bistable functions [

14], giving rise, among other applications, the proposal of efficient structure for non-volatile memory storage with reconfigurable memory addressing to be used in photonic computing architectures [

15].

Independently of the underlying physical effect, the switching mechanism depends on the fine tuning of the refractive index of suitable materials incorporated in the device. So, the integration of subwavelength-structured metasurfaces and metamaterials on the standard optical waveguides can be suited to the proper design of a variety of meta-waveguides with unprecedented control capabilities [

16]. Within this context, the application of machine learning techniques grants the project of metamaterial-based devices [

17] that can be fabricated in the traditional semiconductor process. Neural network method for optimization of metamaterial-based devices permits us to overcome the intrinsic limitations of conventional design allowing an inverse design approach for metamaterial-based devices [

18]. From this point of view, a deep learning model can be used to determine the output spectrum of a specific photonic device, using the nanostructured geometry of the material as an input. The supervised model needs to be trained with a large dataset of input/output points obtained from simulation, but once trained, it can be used to accurately approximate the output spectrum of a metamaterial much faster than using direct simulations [

19]. The inverse problem can be solved also with a deep learning model by using the outputs as inputs and training the network to find the configuration for a particular output.

One of the most important limits for a large-scale commercialization of Photonic Integrated Circuits (PICs) is the manufacturing tolerances that strongly degrade the PICs fabrication [

20]. While nanoimprint lithography is generally accepted as a technology with great potential to approach these problems [

21,

22,

23] an alternative approach, based on waveguide with multi-micron dimension, allowing a better polarization and process tolerance management, has been recently proposed [

24]. In agreement with these considerations, the increased fabrication tolerance induced by a multi-micron dimension paves the way to a new efficient use of hydrogenated amorphous silicon (a-Si:H) deposited by the Pressure Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition (PECVD) method [

25]. State of the art good quality a-Si:H can be deposited by PECVD as this technique has reached a stable maturity and quality, due to the large investment directed to mass production of a-Si:H solar cells [

26] and thin film transistor for active-matrix flat panel displays [

27].The electro-optical effects in silicon were well described and theoretically supported by Soref in 1987 [

28], where the charge carrier effect is reported to produce a modification of the semiconductor refractive index up to an order of 1-10%. Based on the same, adapted, Soref model, electrooptic modulators based on a-Si:H material have been dimensioned and fabricated [

29,

30]. Indium thin Oxide (ITO) has been observed to exhibit a huge enhancement of the non-linear optical response [

31] and proposed as a good candidate for nonlinear photonics metasurface [

32]. Such peculiar characteristics have been exploited for ITO-Silicon integrated structures in very attractive structures for photonics neural network applications [

33] and reconfigurable devices where the ITO/Si structure acts as a localized MOS capacitor island [

34].

Taking into consideration all the application opportunities and the technology requirements presented above, following a methodology previously introduced35 by the authors [

36], this work presents a feasibility study about an alternative switching structure. The study is based on numerical simulations performed using the RSOFT Photonics Packages FDTD and BPM algorithms via an University Donation Program [

37]. The proposed solution joins the multi-micron approach to the switching functionality and the specific electro-optic properties of amorphous silicon. The typical light splitter/coupler multimode interference structure (MMI) configuration is interfaced with a reconfigurable pixeled meta-surface, producing a building block suitable to be used as a photonic 1x2 logic gate. The configuration proposed, where each MOS “pixel” produces a local alteration of the refractive index is only possible with the use of amorphous silicon. In fact, due to its intrinsic low conductivity, a-Si:H lateral transport effects are naturally confined to the region of the charge source [

38,

39], as it has been extensively reported in previous works targeting imaging devices [

40]. So, limiting the crosstalk between neighbor MOS pixels, amorphous silicon appears to be a natural choice for the idea hereby proposed, based on joining the concept of metamaterial-based devices with PECVD materials and Active-Matrix control.

2. The Optical Phase Shifter

The main building block for a programmable PIC is a 2x2 gate, and the the standard approach for implementing a programmable functionality is based on the thermo-optic effect, by employing an electrically controlled heater on the waveguide surface and inducing a slight change on the semiconductor refractive index. The thermo-optic coefficient of a-Si:H at room temperature is estimated to be 2.3×10−4 K−1 [

41], about 20% higher than that of c-Si [

42].

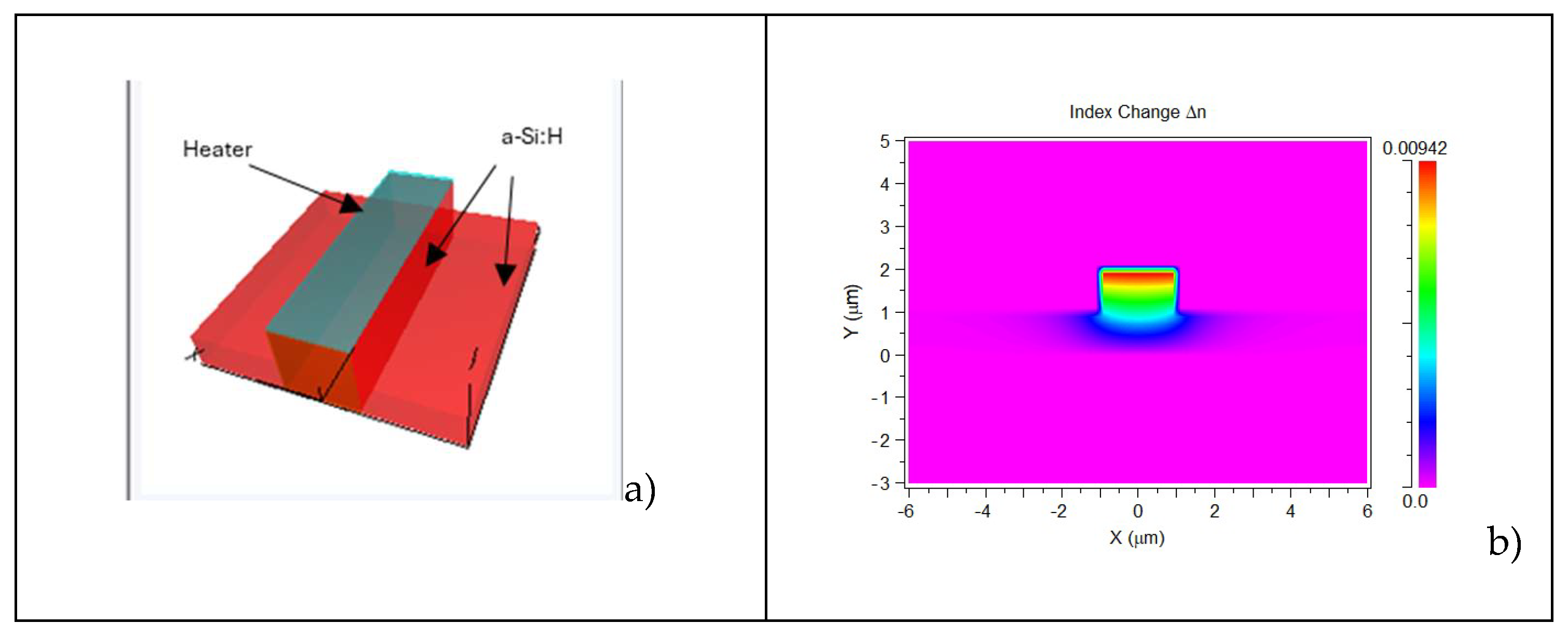

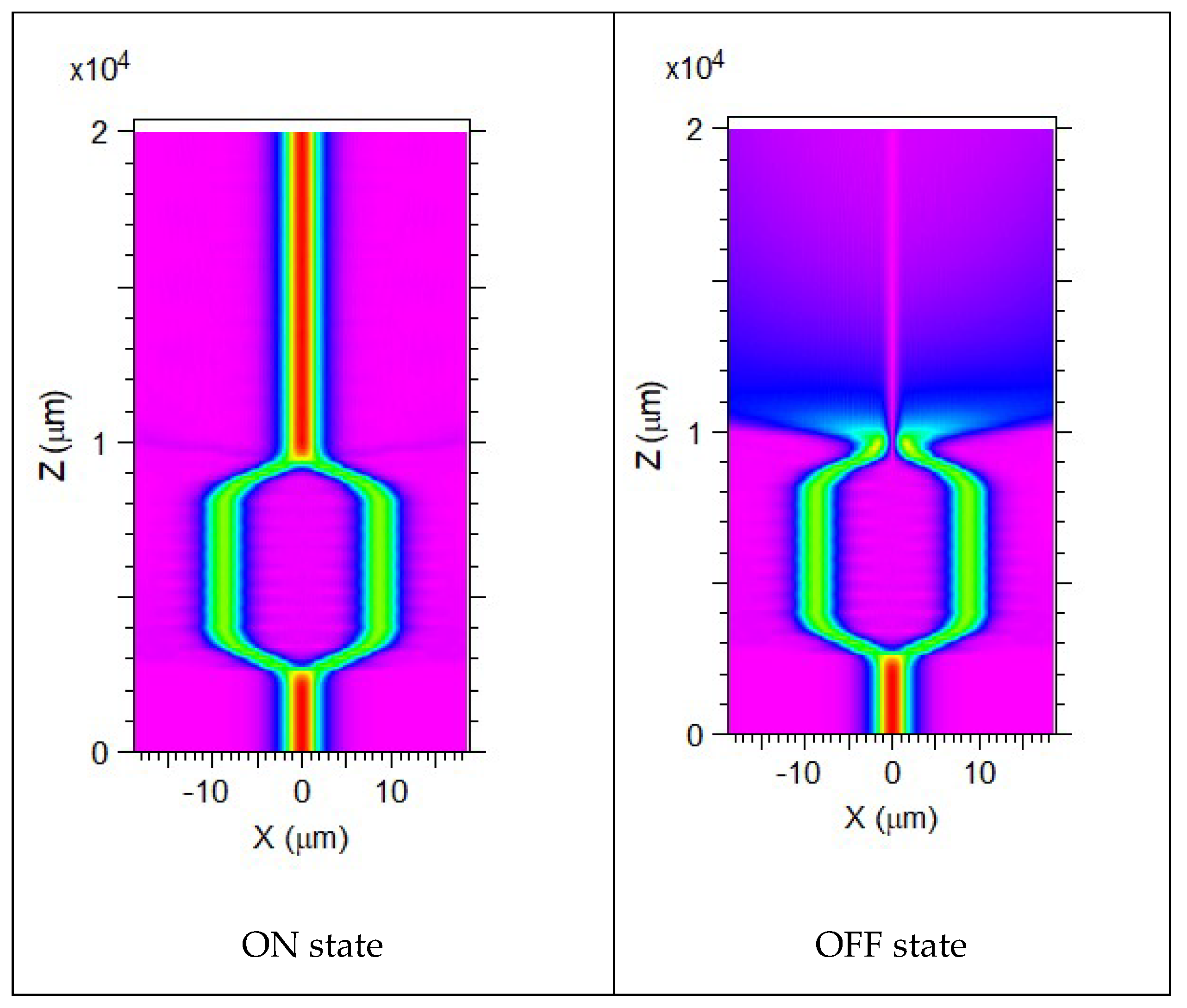

Figure 1 reports the simulated results about the index change over a temperature variation of 100 K. The extent of the index variation is present but limited to small values, which lead to a standard geometry for an interferometric switch with dimensions in the order of magnitude of tenths of millimeters (see

Figure 2). While the PECVD deposition technique is prone to handle the fabrication of large area devices, the uniformity of the lithographic process can be a challenge requirement to be fulfilled. A largely exploited alternative is based on the electro-optic effect induced by free carrier accumulation, extensively described in silicon [

43] as having a refractive index change up to 10-2 for the wavelength of 1550 nm and even higher in a-Si:H the because of the presence of the trapped carriers at localized states [

44]. Yet, the dimension of the phase shifter, necessary for an On-Off function, remains higher, limiting the fabrication of Programmable Pics with a large number of gates. So, other alternatives approaches have been proposed to address the problem of scaling PICs dimension, like phase change materials, liquid crystal based, MEMS, Piezo or Pockels [

45]. In the following of this manuscript, we propose the

Meta-MMI as alternative switching structure with reduced dimension.

3. The metaMMI model

MMI couplers, based on self-imaging multimode waveguides, are highly compact integrated optical components that can perform multiple different splitting and recombining functions. The underlying self-imaging principle, in multimode waveguides, is described using a guided mode propagation analysis [

46] and an optimal configuration can be analytically calculated [

47]. Anyway, when the device geometry becomes irregular, an analytical approach is no longer possible, and the solution can be obtained only by the application of numerical simulation techniques [

48].

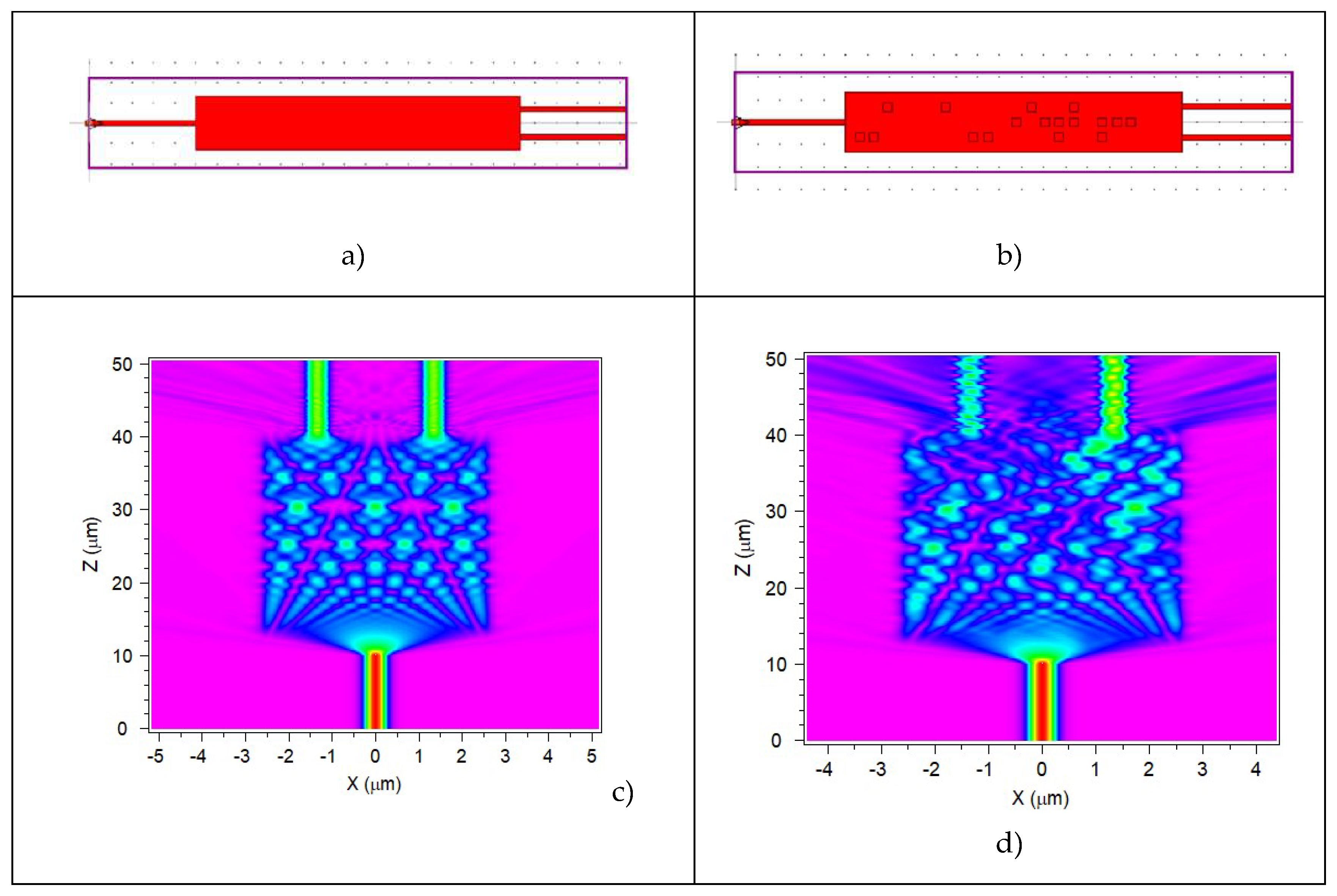

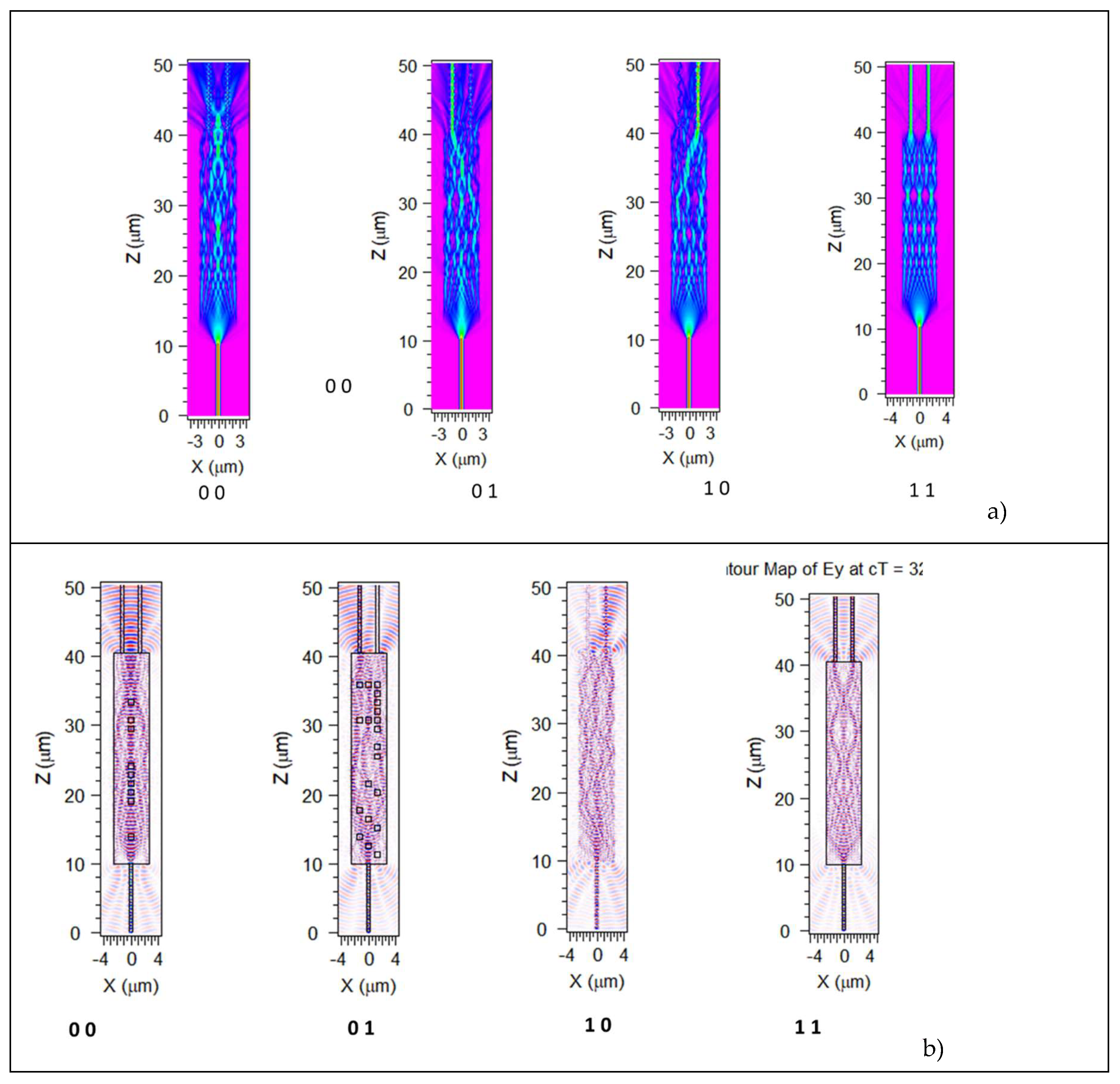

As a first step, we have simulated and optimized the MMI behavior. It can be observed in

Figure 1.c that if all the MMI dimensions are optimized, the field entering through the input port is equally divided into two output channels. This configuration (figure 1.a), typical in the splitter devices, is very sensitive to the parameter defining the device geometry, the material used and the light wavelength.

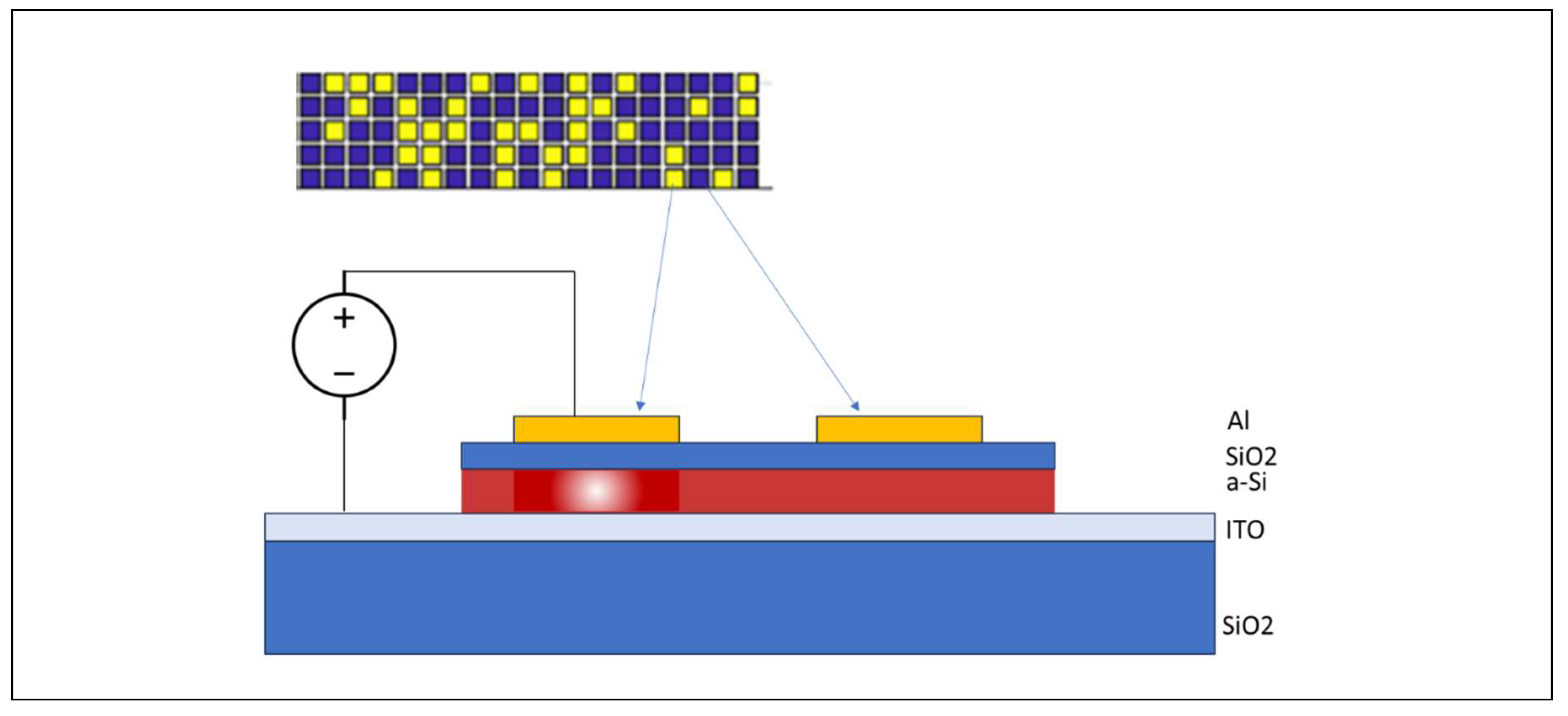

The second step is the introduction, in the simulation layout, of an array of small square regions where the material optical properties (i.e the refractive index) are locally modified. Consequently, light propagation inside the MMI is also modified and the light intensity at the output channels changes conveniently. This configuration can be considered as an externally induced metasurface in the MMI main body. Such metasurface effect could be created and controlled by a MOS structure deposited on top of the semiconductor surface, where the charge accumulation induced at the surface by an externally applied voltage, together with the thin dimension in the vertical dimension of the photonic layer produces a small change in the semiconductor refractive index that can be approximated by a uniform vertical distribution.

Figure 2 reports a sketch of the proposed MOS controlled metasurface, as we have introduced it in our simulations. Indeed, the perturbation induced on the refractive index depends on the concentration of the accumulated charge, which in its turn depends on the MOS structure and on the applied voltage. Finally, once one knows the induced charge accumulation, the new refractive index can be calculated by the Soref model. The fine tuning of the electrically controlled refractive index was not studied in detail in this work, and our conclusion about its feasibility relies on the well-established technology for Thin Film Transistor (TFTs) supporting Active Matrix Displays [

49]. At the present stage, our approach targets mainly the demonstration of the metasurface effects, to control the output of a reconfigurable logic gate, so the physical considerations about the material properties, even if of major importance in a fabrication step, will be further addressed in a second time, together with the specific requirements from the selected facilities for the device fabrication. The semiconductor used in our simulation is amorphous silicon, with a refractive index

naSi = 3.42149, deposited on a ITO substrate [

50]. Covered by a SiO2 layer with

nSiO2= 1.4551. By a straightforward calculation, as reported in literature [

51], over a MOS structure ITO/SiO2/a-Si:H the bias application is expected to produce a charge accumulation in the range 1019-1020 cm-3., being possible to control this value through the modulation of the oxide layer thickness. Such charge accumulation corresponds to an index variation spanning in the range 0.01-0.22 [

43]. As an example, in

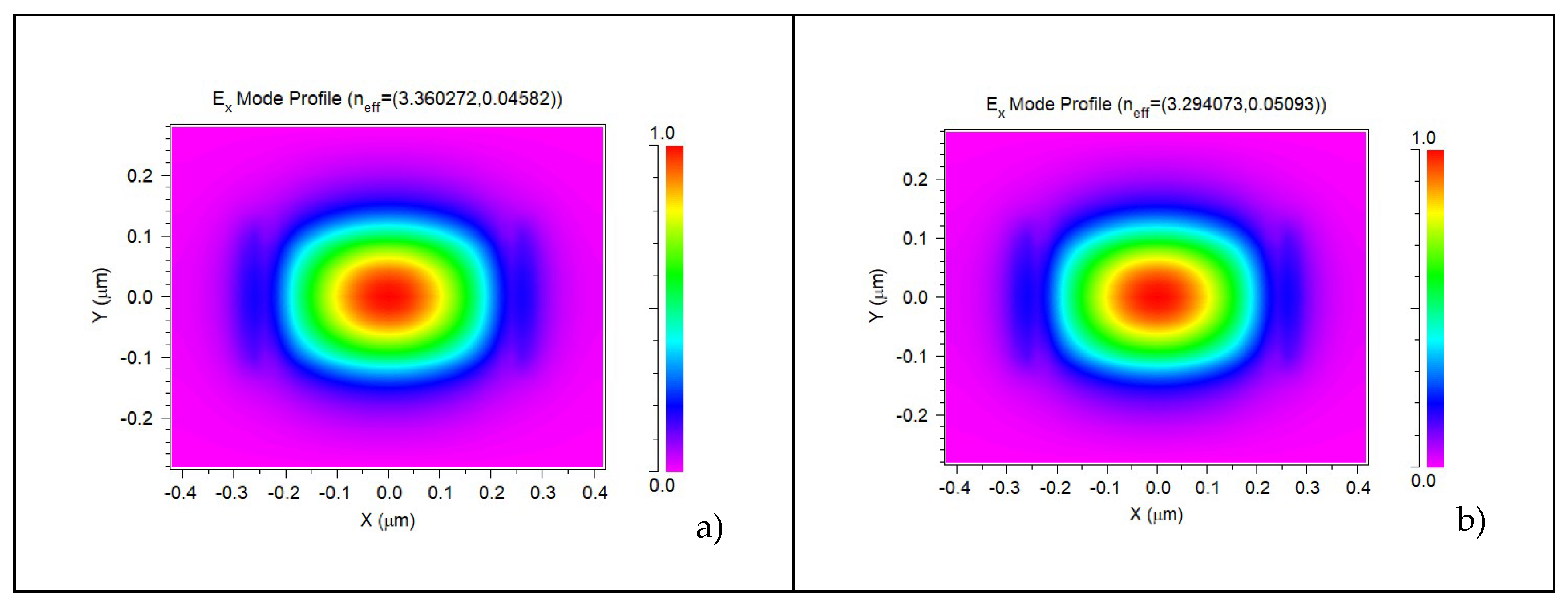

Figure 3 is reported the TE00 mode within an a-Si:H waveguide with no charge accumulation compared with the case of a charge accumulation of 1020 cm-3; it is posible to onserve that the effective modal index reduction is of the order of 10-2.

Figure 2.

MOS controlled metasurface. The white region represents the charge accumulation when an external bias is applied to the metal contacts.

Figure 2.

MOS controlled metasurface. The white region represents the charge accumulation when an external bias is applied to the metal contacts.

Figure 3.

TE00 mode within an a-Si:H waveguide with no charge accumulation (a) and with a charge accumulation of 1020 cm-3 (b).

Figure 3.

TE00 mode within an a-Si:H waveguide with no charge accumulation (a) and with a charge accumulation of 1020 cm-3 (b).

In our simulation we have assumed the MOS activation to induce a variation in the refractive index of 0.01%. This value is in the range of what is reported in literature for crystalline silicon [

52] and below the values that could be expected in the amorphous counterpart by exploiting the localized charge trapping due to the unavoidable presence of midgap density of states. Additionally, the choice of amorphous silicon allows taking profit from the high resistivity of the material, reducing lateral charge diffusion [

53] and its related cross-talking effects. In

Figure 4 it is possible to see the device simulations layout, and the results obtained by the simulation, as well as the impact of a random distribution of activated MOS on the output channels.

Once defined the objective of the study, it is necessary to design a 1x2 MMI layout suitable to host on its surface a matrix array of contacts with dimension and density capable of imposing a control on the light intensity of the output channels. The same standard 1x2 3dB splitter function can be obtained by varying conveniently the length (LMMI) and the width (WMMI) of the MMI box. Following a preliminary study, our choice has been guided by the following requirements, where the dimension of the structure is maintained within the limits of a standard lithography process:

The size of each metal contact should be larger than 0.5 mm2.

The separation between adjacent metal contact should be at least 0.5 mm.

The number of metal contacts should maintained be as small as possible

The MMI should perform an optimized 3dB splitting function when no bias is applied to the metal contacts.

By varying the activated MOS contacts, each of the output channels should allow an independent and continue variation of the light intensity.

Considering these requirements, we have chosen an MMI with dimensions

LMMI = 30.55 mm and

LMMI = 5.2 mm. This small footprint allows complete control of the output channels with a 3x20 MOS array where each metal contact is a square with 0.8 mm side. On the active control of the MOS array, we have imposed a rule for maintaining an average of 70% of the contacts in ON state, while the other 30% is kept in OFF state. This choice allows for the possibility of having one of the output channels with full light intensity while the other one receives no light. This configuration, interesting from the digital application point of view, cannot be completely attained with a lower number of contacts in ON state.

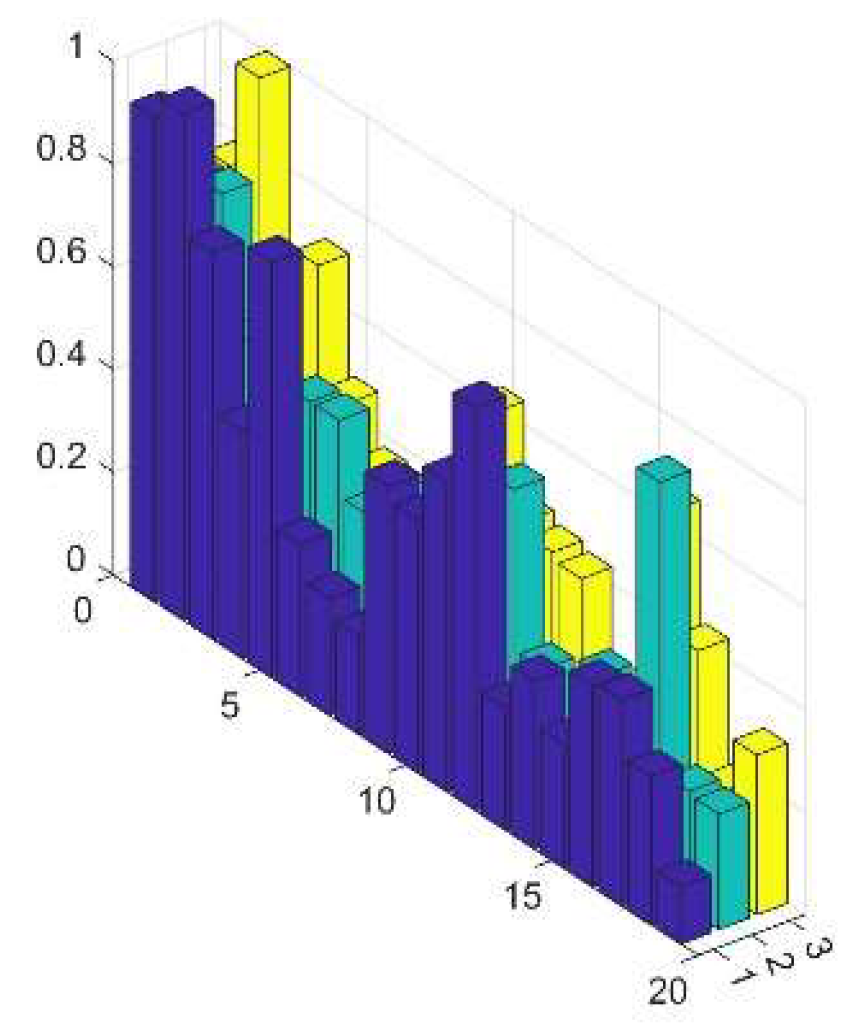

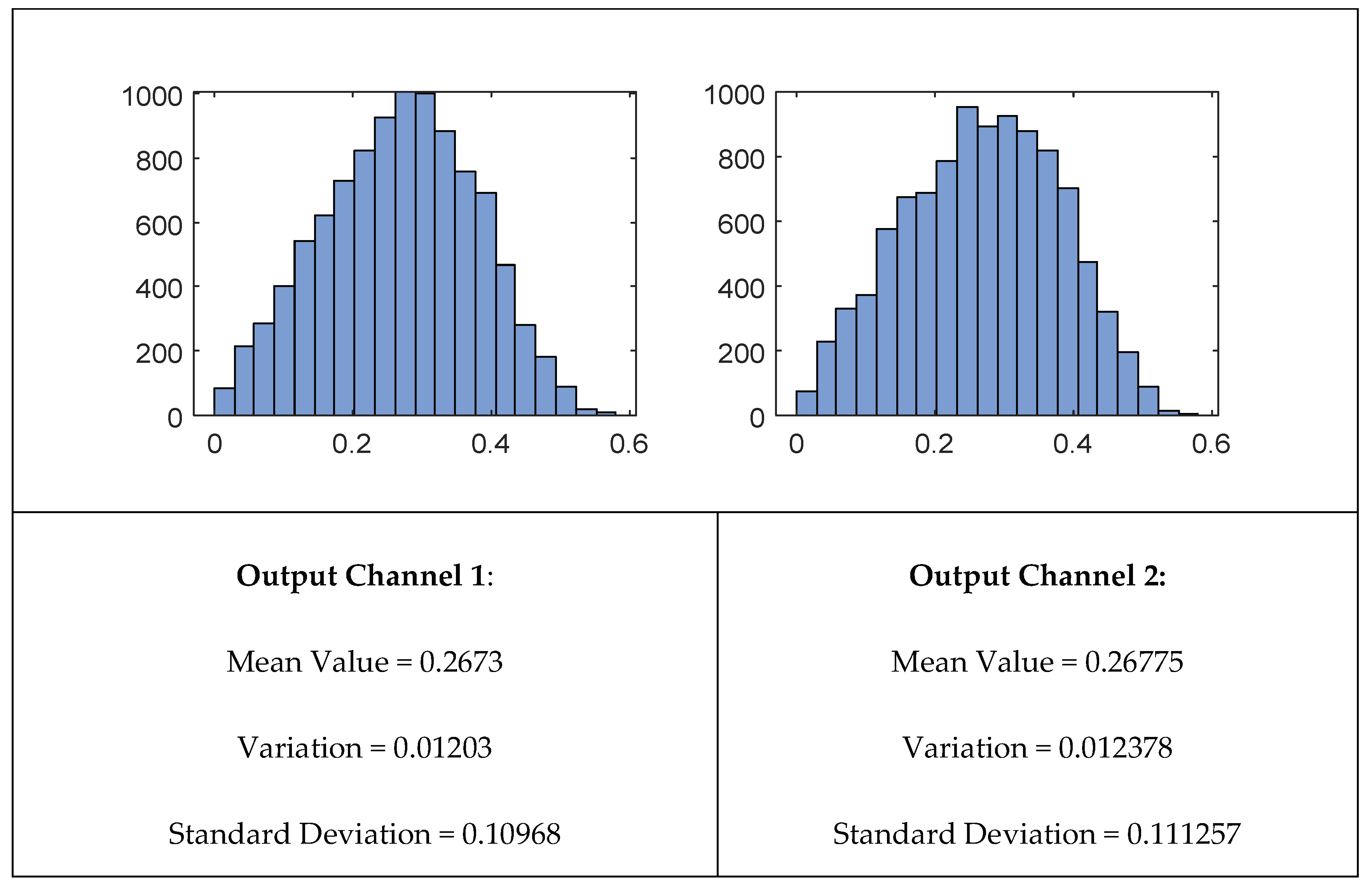

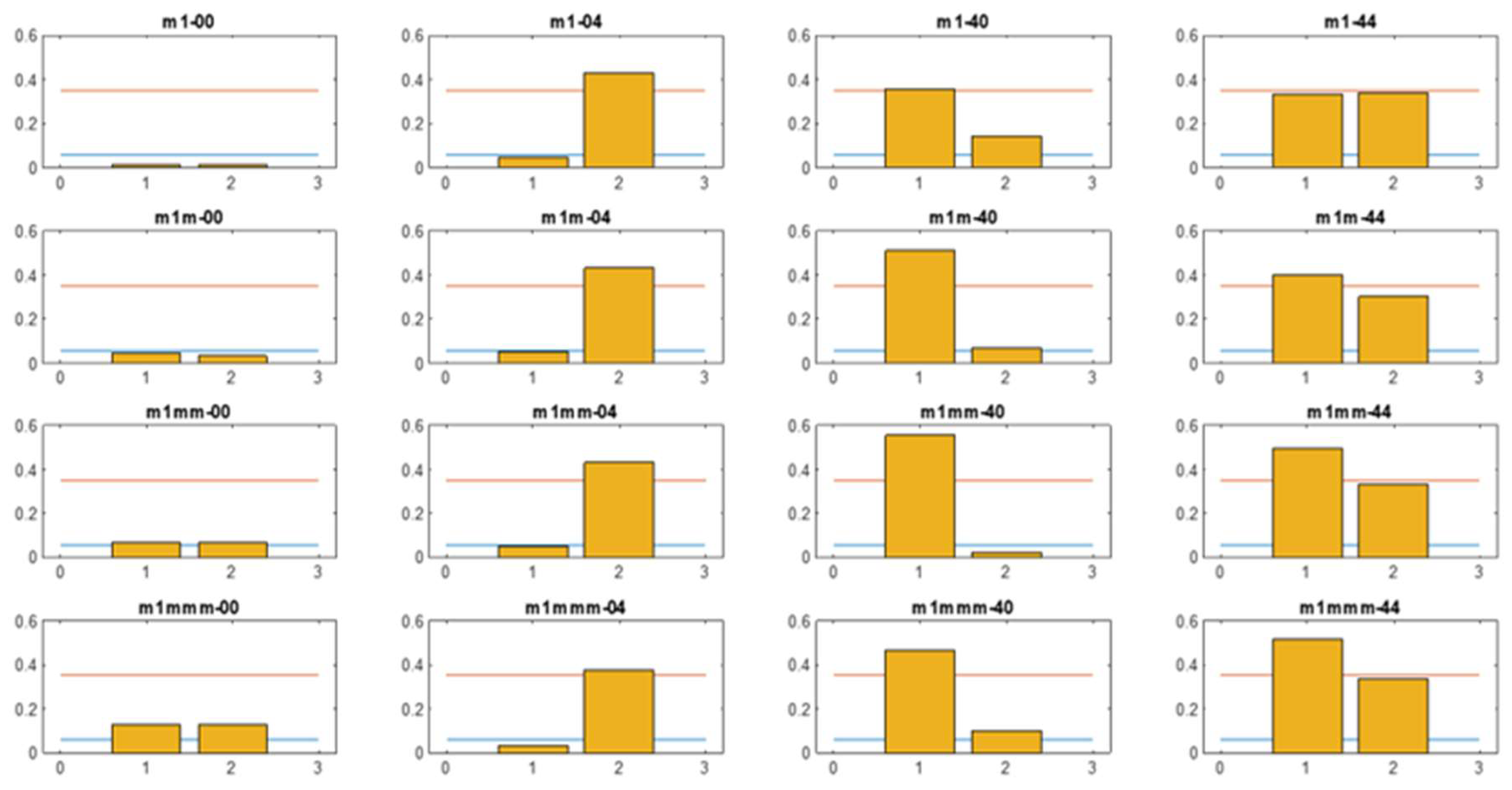

Figure 5 reports a simple statistical analysis of power distribution on each of the two channels, obtained on a set with 1000 samples, randomly generated, yet respecting the optimal condition described above. The channels are symmetric and each one spans between 0 and 50% of the input power.

4. Database creation and analysis

Using the model and the layout described in section 2, it has been produced a database with 105 simulations, obtained using the BeamProp method. Each simulation run has a different configuration of the ON-OFF distribution state of the electric contacts. The result of each simulation run has been classified on the base of the power reading on the output channels. Two different approaches have been attempted, where the power intensity has been discretized on 3 or 5 levels. In the 3-level configuration, the thresholds, defined on the power fraction, separating the different classes are 0.05 and 0.35 for the lower and the higher level, respectively. So, we have the level 0 representing the dark state (power between 0 and 0,5), the level 1 representing the light state (power higher than 0.35) and an intermediate level 2 (power between 0.5 and 0.35). From a digital point of view, we may consider levels 0 and 1 as the significative ones, while level 2 is an intermediate value with no information content. In the 5-level configuration the higher and lower threshold are maintained, while the intermediate level is subdivided in 3 parts. This approach permits a better understanding of the impact that the array ON/OFF configuration has on the final output.

A python script produced a set of about 2×105 RSOFT simulation runs, based on a random generation of the MOS distribution. The results have been saved in three different formats: straight numerical, B&W graphical representation of the matrix, internally generated EM field.

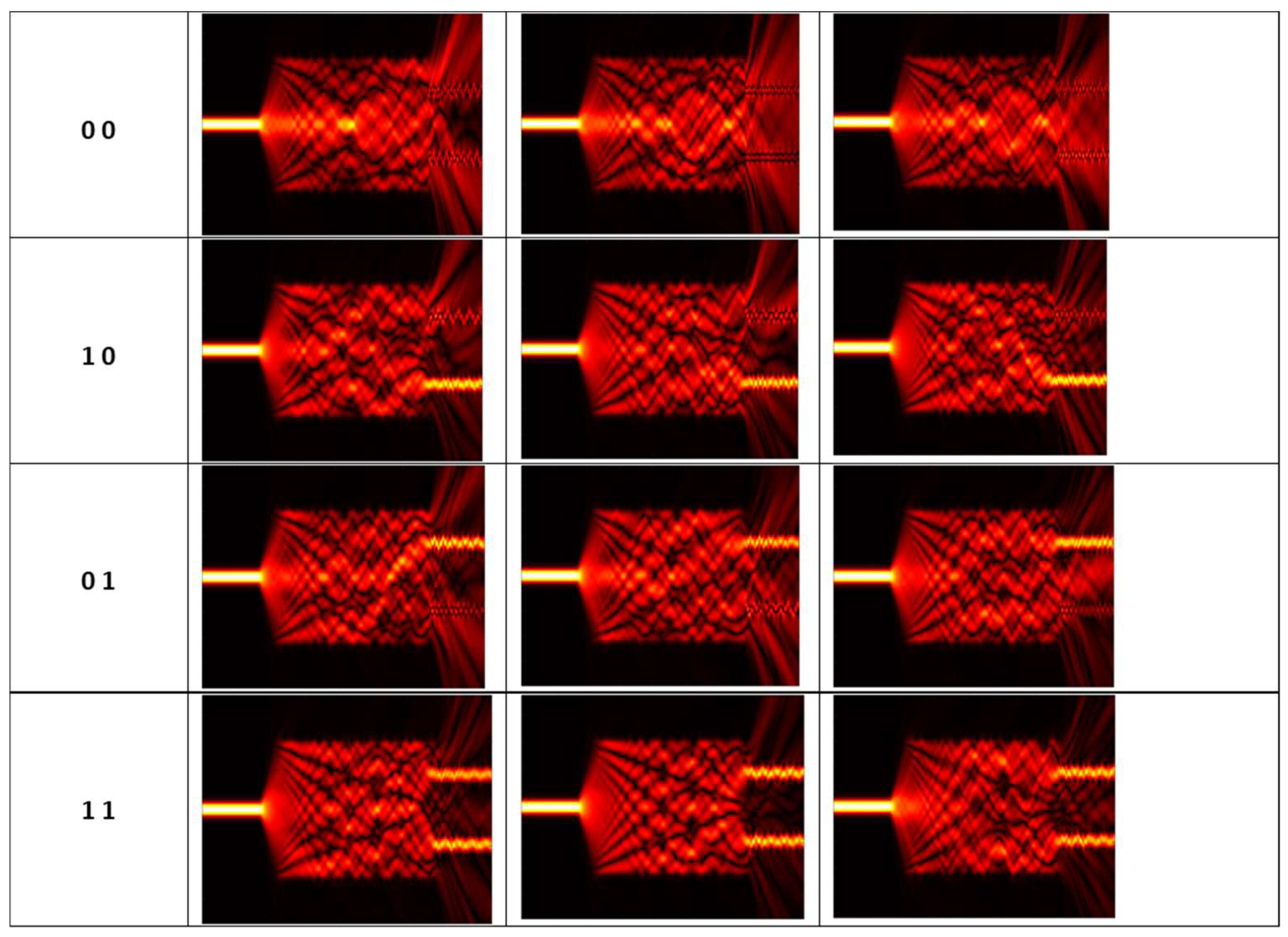

Figure 6 reports an example of the three output formats. The classification of the gate function has been operated on the same scheme previously described in the beginning of this section.

Figure 7 reports a few samples of the classification result. We attribute the digital value 0 or 1 to the output of each channel, depending on the intensity of light. For the analysis carried on, two consequent strategies have been adopted: a machine learning approach from the images and a statistical one from the numerical descriptions. They are detailed in the next section.

5. Machine Learning

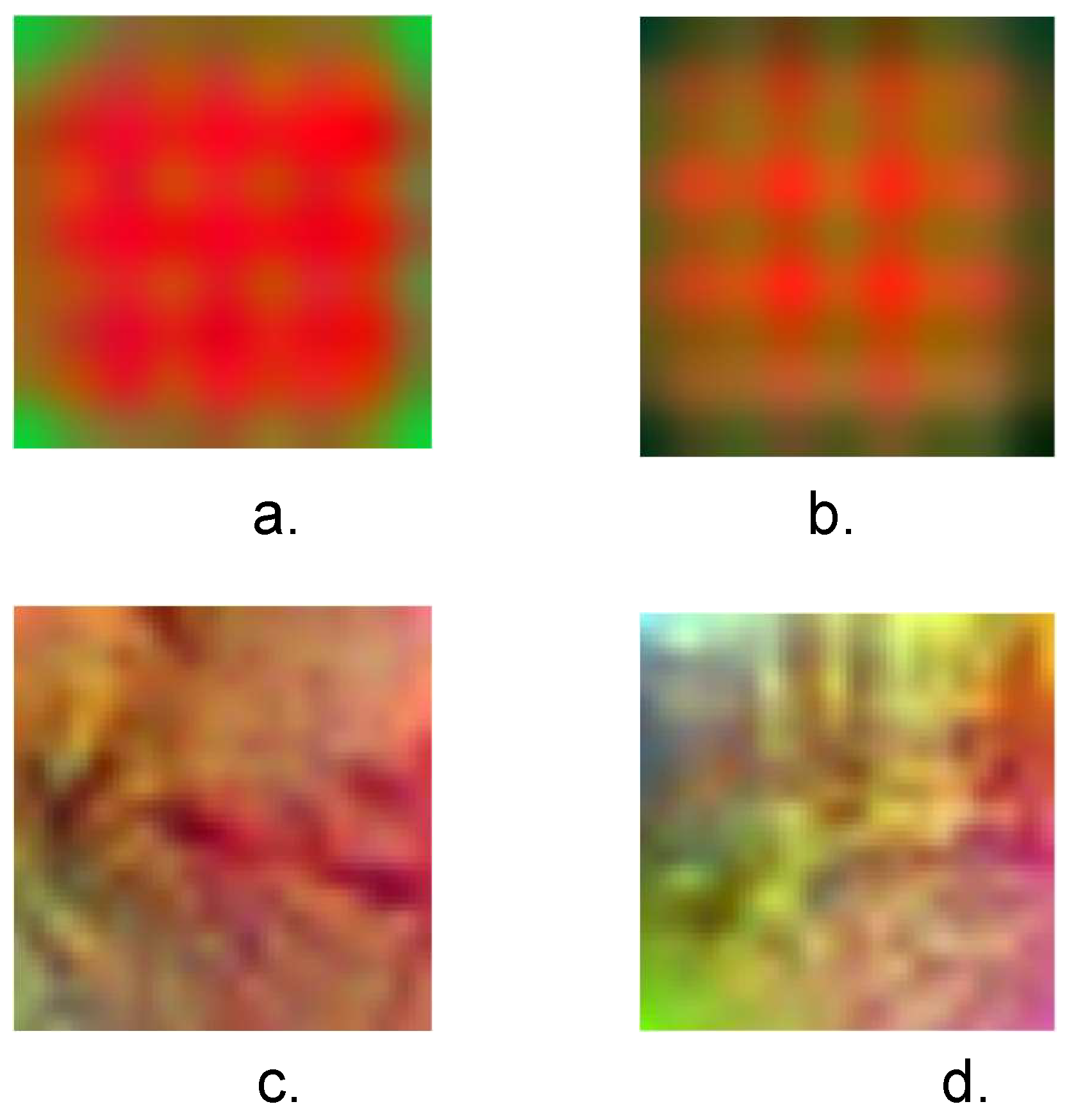

The ML approach for patterns classification according to their generated outputs tries to define a relationship between the features that can be identified in the pictures and the corresponding output they generate. It is a very useful technique when it is assumed that there are also features that cannot be identified by human inspection. In this case, the simulations output in the form of image of internally generated EM field (rightest image in

Figure 6) has been used for training of a machine learning network, developed on the Deep Learning Matlab Toolbox. It is mainly constituted by a sequence of segmentation and convolutions, followed by Normalization and a Rectifying Linear Unit operation to get only positive quantities (for example, ReLU(x)=max(0,x) ). Going deeper in the network, the images transformations produce patterns and features that human interpretation cannot explain but are somehow connected to the original images through deterministic operations. For example, one can have patterns like the ones in

Figure 8 (a. and b., higher level, still geometric features, c. and d., deeper level, lost human visual correspondence and interpretation).

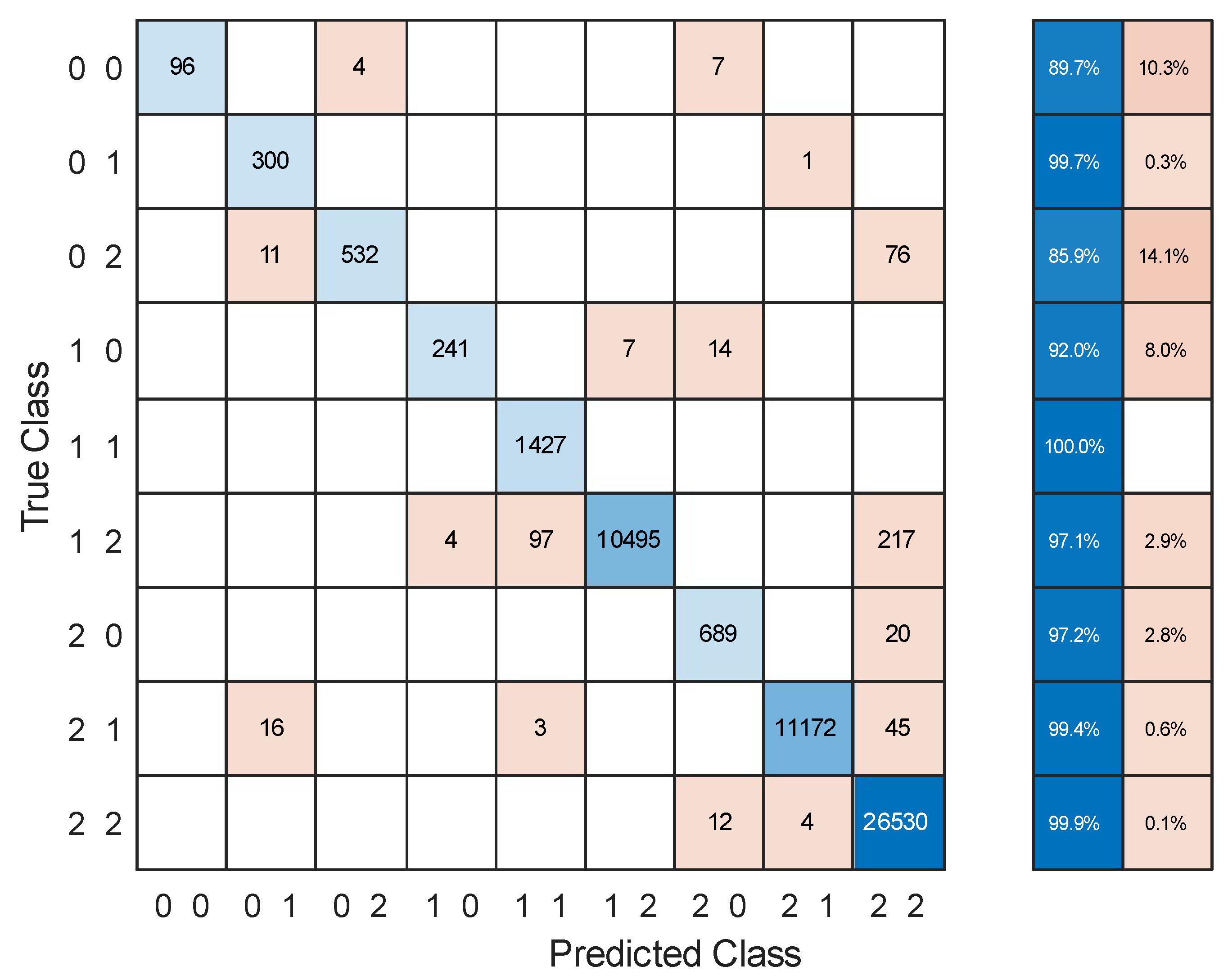

Figure 6 synthetizes the effectiveness of the system identification of the output produced for any given image to be analyzed. It is reported in the form of a confusion matrix for a classification of a 1x2 logic gate output channels, obtained by the previously trained network. It reports, for all the images belonging to each class and given in the vertical axis, which class the trained network associates to, horizontal axis.

Power in the channel is subdivided in three levels (0, 1, and 2). Precision of the classification is 90%. Accuracy is 97%. 0 should be intended as “light off”, 1 as “light on”, while 2 represents an intermediate value. The four combinations of interest are (0,0); (1,0); (1,0); (1,1).

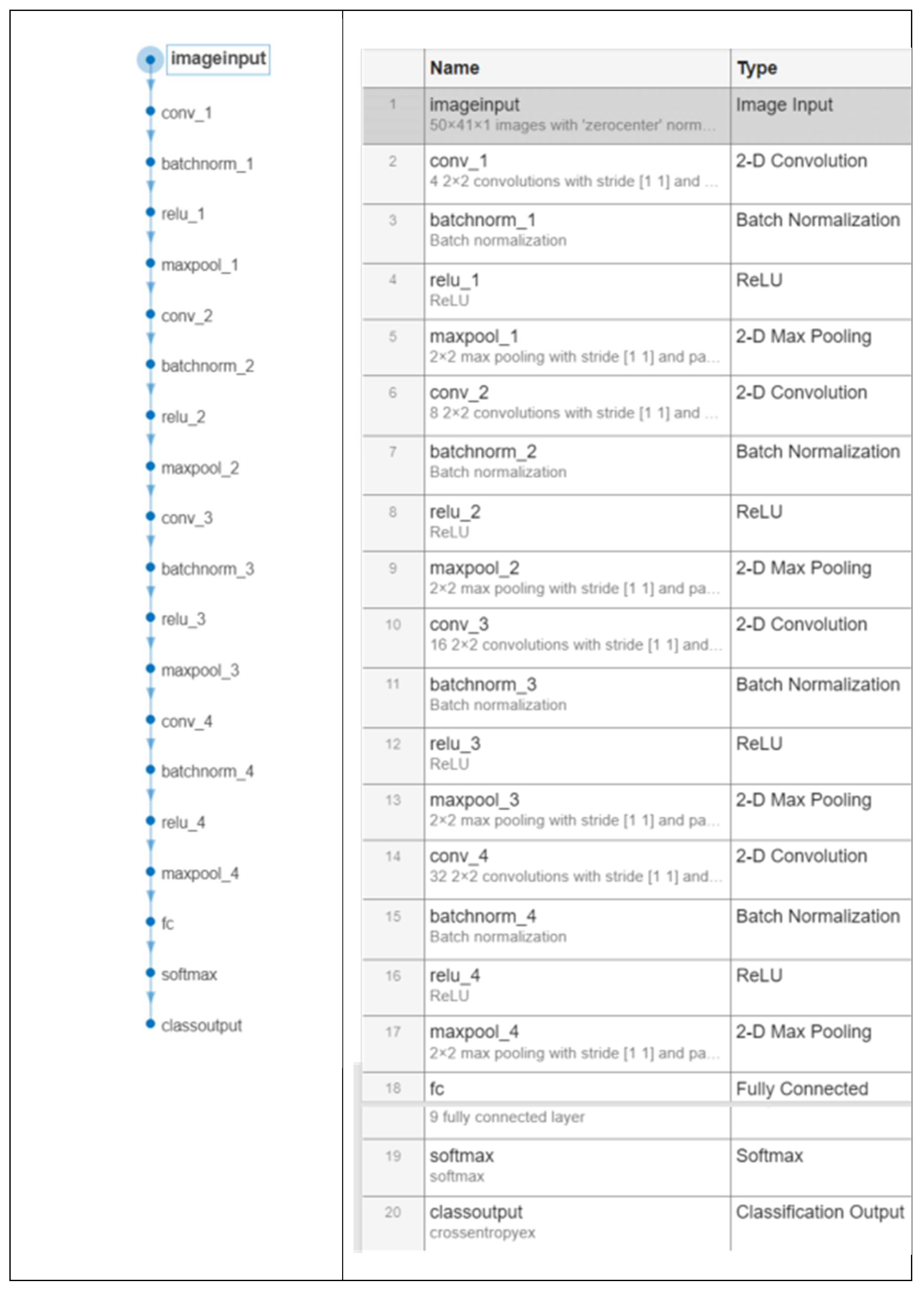

A graphical representation of the network architecture is reported in

Figure 9. And the confusion matrix obtained after the ML training is reported in

Figure 10. The result confirms that the approach can successfully produce an optical reconfigurable digital 1x2 output by controlling the distribution of the refractive index inside a MMI structure, imposed by a MOS active matrix behaving as a reconfigurable metasurface.

6. Statistical analysis

The matrix structure of the device, once seen as an array of activation points, suggests a different approach for the identification and the detection of the characteristic patterns generating each output.

In fact, it is possible to assume that there exists at least one optimal activation pattern for any desired output, and small changes in the optimal pattern (differences in a few activation points, ON instead of OFF and vice versa) produce small changes in the output signals. In this case, given a randomly generated activation array, the closer it is to the (one of) optimal pattern, the more the output is like the exact one. Then, given two activation arrays with comparable output, the differences between their patterns and the optimal one should be small and, consequently, also the differences between their patterns should be small too.

Be

the

-th array associated with a certain pattern configuration of activated points,

the one of (unknown) optimal pattern which best generates the output

, and be

the error between patterns, for example defined simply as the array

so that each entry

, with 0 when the activation point is present in both the patterns and

when it is present in only one.

Then, given a set of

p patterns which produces outputs comparable with the

k-th optimal one

, a classical procedure of the least square error computation can be adopted to find the best estimation

of the optimal one, defining the mean square error

and computing

to minimize

. One has

yielding to the classical expression of the average value

Clearly, according to those definitions, each entry of belongs to the continuous interval . A statistical interpretation of such a result allows one to associate the values of the entries to the probability of the presence of the corresponding activation point in the optimal pattern.

Being the input matrix defined over

, possible choices for reliable activation patterns can be obtained assuming a confidential threshold

for probability, defining the NxM array

with all entries equal to

and choosing

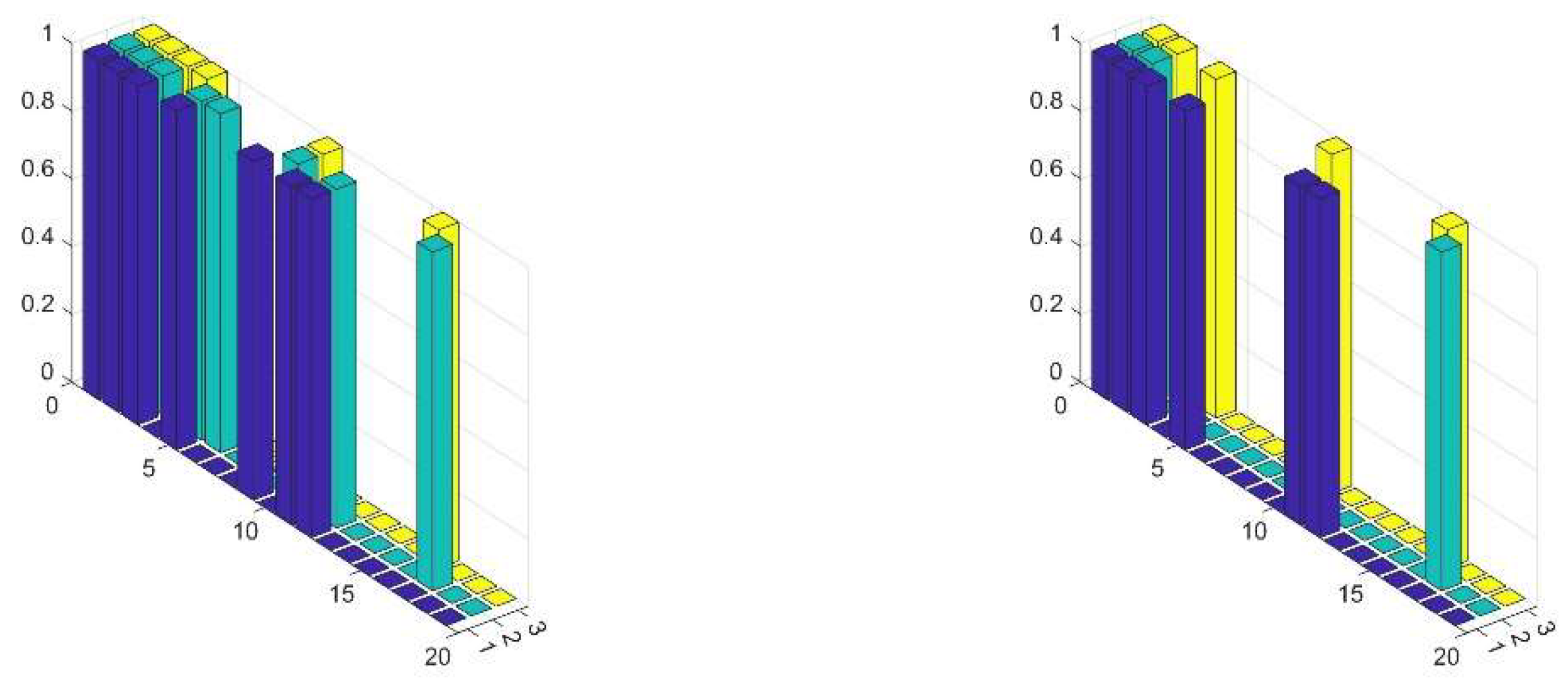

as best approximation of optimal pattern. An example is depicted in

Figure 10, where the probability array obtained as the average matrix over all the patterns corresponding to acceptable outputs close to (1,0),

, is reported: Correspondently, the appliable configurations obtained choosing as possible confidence thresholds 0.5 and 0.6 are depicted in

Figure 11. All the

patterns obtained with such a procedure for all the possible output have been simulated, obtaining very satisfactory results.

Figure 10.

Matrix of probability of activation points for the configuration with output (1,0)

Figure 10.

Matrix of probability of activation points for the configuration with output (1,0)

Figure 11.

Matrix of activation points for output (1,0) assuming a threshold (left) and (right).

Figure 11.

Matrix of activation points for output (1,0) assuming a threshold (left) and (right).

7. Conclusion

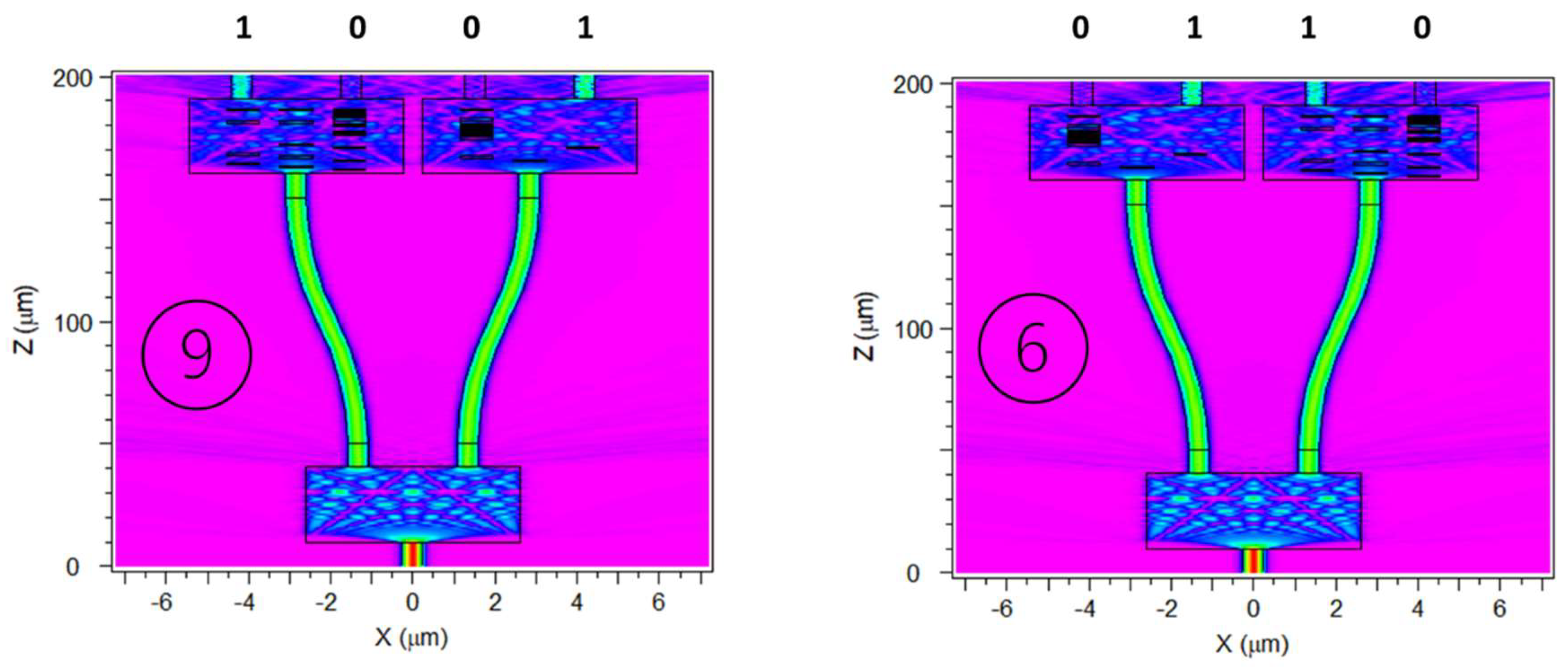

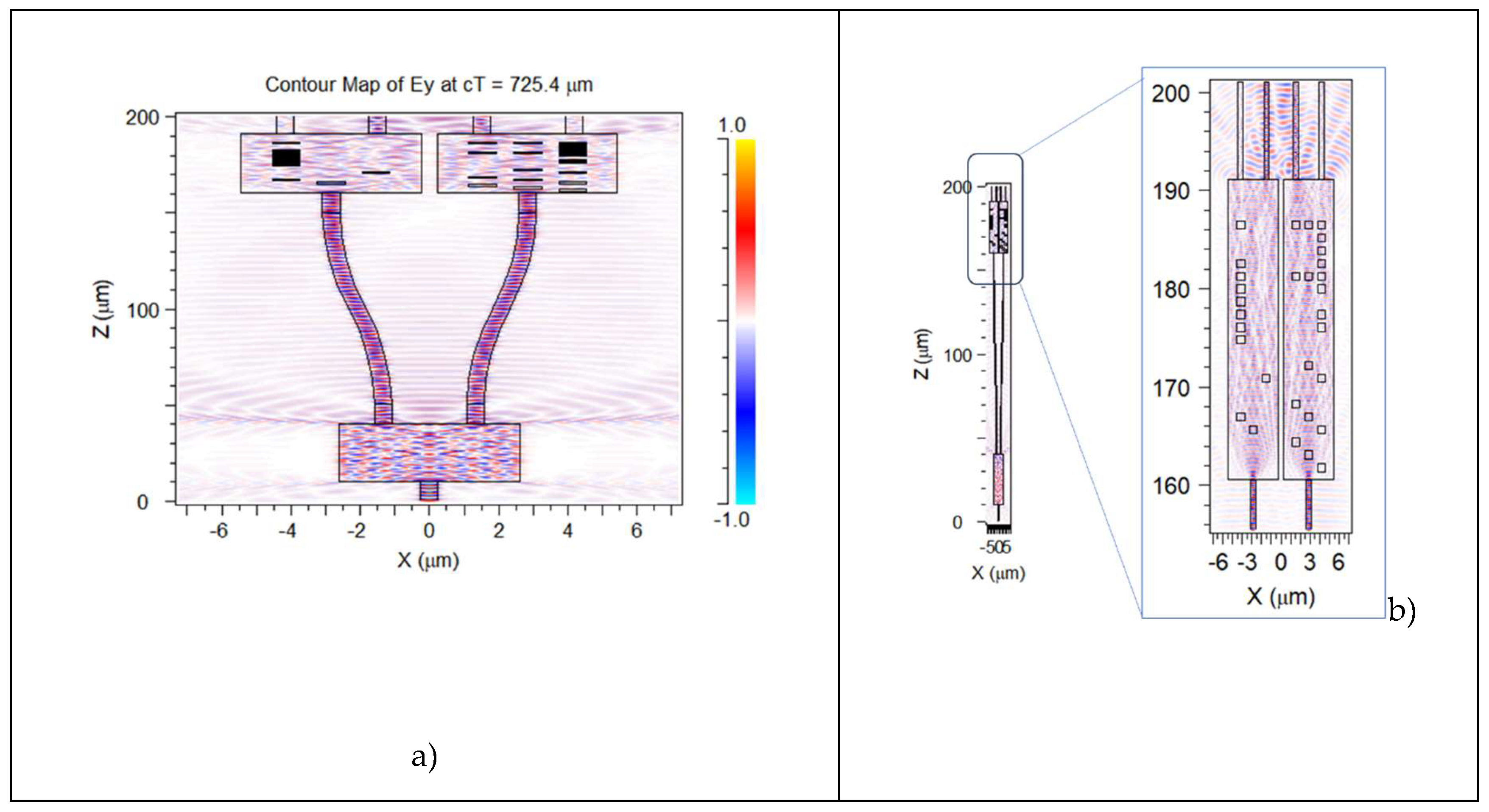

The recent advances in silicon photonic integrated circuits have highlighted the need for a new class of reconfigurable building blocks. In this paper we have proposed a novel approach, based on a MOS induced charge accumulation and respective local refractive index modification. As a proof of concept, a 1x2 logic gate has been demonstrated through the application of a machine learning approach for analyzing the MOS matrix configuration. A similar approach can be used for configuring more complex devices, with special attention to a 2x2 reconfigurable optical gate, with the potential of being used as the basic building block for programmable photonic integrated circuits. As proof of concept, a 4-bit register, operated by a combination of three metaMMIs has been demonstrated in continuous wave and pulsed light input conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Video S1: Time dependent .simulation of a pulsed light input traveling inside a metaMMI (1-1 oputput) and

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s2, Video S2: Time dependent .simulation of a pulsed light input traveling inside a metaMMI (0-1 oputput).

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, A.F. and P.DG.; methodology, A.F. and P.DG; software, A.F. and P.DG; validation, A.F.; formal analysis, P.DG; resources, A.F. and P.DG; data curation, A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F. and P.DG; funding acquisition, A.F. and P.DG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was supported by FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, through the Portuguese FCT program, Center of Technology and Systems (CTS) UIDB/00066/2020 / UIDP/00066/2020, by FCT project ASER-META 2022.07694.PTDC, by project IPL/IDI&CA2024/OPAPIC2D_ISEL and by the University of Roma “la Sapienza” through Sapienza Visiting Professor Programme 2022

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- D. Thomson et al., “Roadmap on silicon photonics,” J. Opt., vol. 18, pp. 073003-1–073003-20, 2016.

- C. Minkenberg et al. Reimagining datacenter topologies with integrated silicon photonics. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2018, 10, B126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Near Margalit, Chao Xiang, Steven M. Bowers, Alexis Bjorlin, Robert Blum, and John E. Bowers. Perspective on the future of silicon photonics and electronics. Applied Physics Letters 2021, 118, 220501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, S. , Bogaerts, W., Chrostowski, L., Bowers, J. E., Hochberg, M., Soref, R., & Shastri, B. J. Roadmapping the next generation of silicon photonics. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 751. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soref, R. Tutorial: Integrated-photonic switching structures. Apl Photonics 2018, 3, 021101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miscuglio, M. , & Sorger, V. J. Photonic tensor cores for machine learning. Applied Physics Reviews 2020, 7, 031404. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y. , Huang, J., Yang, L., Ma, H., Yuan, H., Xie, T.,... & Zhang, Z. Inverse-designed ultra-compact high efficiency and low crosstalk optical interconnect based on waveguide crossing and wavelength demultiplexer. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dinsdale, N. J. , Wiecha, P. R., Delaney, M., Reynolds, J., Ebert, M., Zeimpekis, I.,... & Muskens, O. L. Deep learning enabled design of complex transmission matrices for universal optical components. ACS photonics 2021, 8, 283–295. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaerts, W. , Pérez, D., Capmany, J., Miller, D. A., Poon, J., Englund, D.,... & Melloni, A. Programmable photonic circuits. Nature 2020, 586, 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- José Capmany Francoy "General-purpose programmable integrated photonics processors: what things can you do with them?", Proc. 19 June 1301; C2. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, D. , Gasulla, I., Mahapatra, P. D., & Capmany, J. Principles, fundamentals, and applications of programmable integrated photonics. Advances in Optics and Photonics 2020, 12, 709–786. [Google Scholar]

- Beeckman, J. , Bogaerts, W., Van Iseghem, L., García, J. P., & Liu, J. (2024, June). Liquid crystal as material for highly efficient phase shifters in integrated photonics. In Liquid Crystals Optics and Photonic Devices (p. PC130160H). SPIE.

- Quack, N. , Takabayashi, A. Y., Sattari, H., Edinger, P., Jo, G., Bleiker, S. J.,... & Bogaerts, W. Integrated silicon photonic MEMS. Microsystems & Nanoengineering 2023, 9, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. , Rogers, E. T., Gholipour, B., Wang, C. M., Yuan, G., Teng, J., & Zheludev, N. I. Optically reconfigurable metasurfaces and photonic devices based on phase change materials. Nature Photonics 2016, 10, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Nurgali, A. , Nakarmi, B., Molardi, C., & Ukaegbu, I. A. (2024). 4x4 bit Programmable Optical Memory Array with Digital Addressing using Micro-Ring Resonators. IEEE Access.

- Meng, Y. , Chen, Y., Lu, L., Ding, Y., Cusano, A., Fan, J. A.,... & Ni, X. Optical meta-waveguides for integrated photonics and beyond. Light: Science & Applications 2021, 10, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Banerji, S. , Majumder, A., Hamrick, A., Menon, R., & Sensale-Rodriguez, B. Ultra-compact integrated photonic devices enabled by machine learning and digital metamaterials. OSA Continuum 2021, 4, 602–607. [Google Scholar]

- Khatib, O. , Ren, S., Malof, J., & Padilla, W. J. Deep learning the electromagnetic properties of metamaterials—a comprehensive review. Advanced Functional Materials 2021, 31, 2101748. [Google Scholar]

- Nadell, C. C. , Huang, B., Malof, J. M., & Padilla, W. J. Deep learning for accelerated all-dielectric metasurface design. Optics express 2019, 27, 27523–27535. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, A. , Matsiusheuski, D., Polatynski, A., Duzgol, O., Sokolov, E., Koltchanov, I., & Mingaleev, S. (2021, March). Schematic-driven PIC design process considering manufacturing tolerances. In Smart Photonic and Optoelectronic Integrated Circuits XXIII (Vol. 11690, p. 1169004). International Society for Optics and Photonics.

- Hillmer, H. , Woidt, C., Istock, A., Kobylinskiy, A., Nguyen, D. T., Ahmed, N.,... & Kusserow, T. Role of nanoimprint lithography for strongly miniaturized optical spectrometers. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 164. [Google Scholar]

- Rabus, D.G. , Sada C. (2020) Sensors. In: Integrated Ring Resonators. Springer Series in Optical Sciences, vol 127. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Oh, D. K. , Lee, T., Ko, B., Badloe, T., Ok, J. G., & Rho, J. Nanoimprint lithography for high-throughput fabrication of metasurfaces. Frontiers of Optoelectronics 2021, 14, 229–251. [Google Scholar]

- Zilkie, A. J. , Srinivasan, P., Trita, A., Schrans, T., Yu, G., Byrd, J.,... & Rickman, A. G. Multi-micron silicon photonics platform for highly manufacturable and versatile photonic integrated circuits. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2019, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Trita, A. , Thomas, A., & Rickman, A. CMOS compatible athermal silicon photonic filters based on hydrogenated amorphous silicon. Optics Express 2022, 30, 19311–19319. [Google Scholar]

- Schropp, R. E. , Carius, R., & Beaucarne, G. Amorphous silicon, microcrystalline silicon, and thin-film polycrystalline silicon solar cells. MRS bulletin 2007, 32, 219–224. [Google Scholar]

- Jin Jang, [Preparation and Properties of Hydrogenated Amorphous Silicon Thin-Film Transistors, Thin Film Tansistors], C.Kagan, P. Andry (Eds.), 2003.

- Soref, R. I. C. H. A. R. D. A. , & Bennett, B. R. I. A. N. R. Electrooptical effects in silicon. IEEE journal of quantum electronics 1987, 23, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, S. , & Della Corte, F. G. Numerical analysis of electro-optical modulators based on the amorphous silicon technology. Journal of lightwave technology 2014, 32, 2399–2407. [Google Scholar]

- Della Corte, F. G. , Rao, S., Coppola, G., & Summonte, C. Electro-optical modulation at 1550 nm in an as-deposited hydrogenated amorphous silicon pin waveguiding device. Optics express 2011, 19, 2941–2951. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reshef, O. , De Leon, I., Alam, M. Z., & Boyd, R. W. Nonlinear optical effects in epsilon-near-zero media. Nature Reviews Materials 2019, 4, 535–551. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. , Zhang, S., & Zentgraf, T. Nonlinear photonic metasurfaces. Nature Reviews Materials 2017, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, R. , George, J. K., Sun, S., Ferreira de Lima, T., Tait, A. N., Khurgin, J. B.,... & Sorger, V. J. ITO-based electro-absorption modulator for photonic neural activation function. APL Materials 2019, 7, 081112. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, C. , Liu, K., Soref, R. A., & Sorger, V. J. A compact plasmonic MOS-based 2× 2 electro-optic switch. Nanophotonics 2015, 4, 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- .

- Fantoni, A. , & Di Giamberardino, P. (2024, June). A machine learning-based analysis of a reconfigurable 1x2 logic gate operated through an externally-induced metamaterial. In Machine Learning in Photonics (Vol. 13017, pp. 190-196). SPIE.

- Available online:. Available online: https://www.synopsys.com/photonic-solutions/rsoft-photonic-device-tools/rsoft-products.html (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Fernandes, M. , Vieira, M., Rodrigues, I., & Martins, R. Large area image sensing structures based on a-SiC: H: a dynamic characterization. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2004, 113, 360–364. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, M. A. , Vieira, M., Louro, P., Silva, V., Costa, J., & Fantoni, A. SiC multilayer structures as light controlled photonic active filters. Plasmonics 2013, 8, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, M. , Fernandes, M., Fantoni, A., Louro, P., & Schwarz, R. A new CLSP sensor for Image recognition and color separation. MRS Online Proceedings Library (OPL) 2002, 715, A4–3. [Google Scholar]

- Cocorullo, G. , Della Corte, F. G., Moretti, L., Rendina, I., & Rubino, A. Measurement of the thermo-optic coefficient of a-Si: H at the wavelength of 1500 nm from room temperature to 200° C. Journal of non-crystalline solids 2002, 299, 310–313. [Google Scholar]

- Della Corte, F. G. , Esposito Montefusco, M., Moretti, L., Rendina, I., & Cocorullo, G. Temperature dependence analysis of the thermo-optic effect in silicon by single and double oscillator models. Journal of Applied Physics 2000, 88, 7115–7119. [Google Scholar]

- Nedeljkovic, M. , Soref, R., & Mashanovich, G. Z. Free-Carrier Electrorefraction and Electroabsorption Modulation Predictions for Silicon Over the 1–14-$\mu\hbox {m} $ Infrared Wavelength Range. IEEE Photonics Journal 2011, 3, 1171–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, S. , & Della Corte, F. G. Numerical analysis of electro-optical modulators based on the amorphous silicon technology. Journal of lightwave technology 2014, 32, 2399–2407. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaerts, W. , Nagarjun, K. P., Van Iseghem, L., Chen, X., Deng, H., Zand, I.,... & Khan, U. (2023, March). Scaling programmable silicon photonics circuits. In Silicon Photonics XVIII (Vol. 12426, p. 1242601). SPIE.

- Soldano, L. B. , & Pennings, E. C. Optical multi-mode interference devices based on self-imaging: principles and applications. Journal of lightwave technology 1995, 13, 615–627. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, A. , Kwong, D. N., Zhang, Y., Subbaraman, H., Xu, X., & Chen, R. T. 1× N multimode interference beam splitter design techniques for on-chip optical interconnections. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2011, 17, 510–515. [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço, P. , Fantoni, A., Costa, J., & Vieira, M. (2019, November). Lithographic mask defects analysis on an MMI 3 dB splitter. In Photonics (Vol. 6, No. 4, p. 118). MDPI.

- Brotherton, S. D. (2013). Introduction to thin film transistors: Physics and technology of TFTs. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Fantoni, A. , Lourenco, P., & Vieira, M. (2017, July). A model for the refractive index of amorphous silicon for FDTD simulation of photonics waveguides. In 2017 International Conference on Numerical Simulation of Optoelectronic Devices (NUSOD) (pp. 167-168). IEEE.

- Muller, R. S. , & Kamins, T. I. (2002). Device electronics for integrated circuits. Cap 8, John Wiley & Sons.

- Nedeljković, M. (2013). Silicon photonic modulators for the mid-infrared (Doctoral dissertation, University of Southampton).

- Fantoni, A. , Vieira, M., Cruz, J., Schwarz, R., & Martins, R. A two-dimensional numerical simulation of a non-uniformly illuminated amorphous silicon solar cell. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 1996, 29, 3154. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Temperature induced variation of the refractive index of an a-Si:H waveguide. The simulated sctructure (a) and the spatial distribution of the index change (b).

Figure 1.

Temperature induced variation of the refractive index of an a-Si:H waveguide. The simulated sctructure (a) and the spatial distribution of the index change (b).

Figure 2.

On-Off function of an a-Si:H interferometer controlled by thermo-optioc effect.

Figure 2.

On-Off function of an a-Si:H interferometer controlled by thermo-optioc effect.

Figure 4.

Simulation layout of basic MMI structure (a), the MMI interfaced to a metasurface (b) and the correspondent calculated EM field inside the MMIs. In the basic structure (c) the input light is equally split in the two output waveguides, while in the MMI controlled by the metasurface the output balance is changed (d).

Figure 4.

Simulation layout of basic MMI structure (a), the MMI interfaced to a metasurface (b) and the correspondent calculated EM field inside the MMIs. In the basic structure (c) the input light is equally split in the two output waveguides, while in the MMI controlled by the metasurface the output balance is changed (d).

Figure 5.

Histogram of the distribution of the power level at the output channels, calculated on a set of 1000 samples randomly generated. On the x-axis the fraction of the power is reported, calculated on the input power, while on the y-axis the number of occurrences is reported.

Figure 5.

Histogram of the distribution of the power level at the output channels, calculated on a set of 1000 samples randomly generated. On the x-axis the fraction of the power is reported, calculated on the input power, while on the y-axis the number of occurrences is reported.

Figure 6.

Simulation output in three different formats, straight numerical, B&W graphical representation of the matrix, internally generated EM field.

Figure 6.

Simulation output in three different formats, straight numerical, B&W graphical representation of the matrix, internally generated EM field.

Figure 7.

Examples of the simulation output obtained for the logical output classes.

Figure 7.

Examples of the simulation output obtained for the logical output classes.

Figure 8.

Examples of output at different levels of the ML network.

Figure 8.

Examples of output at different levels of the ML network.

Figure 9.

Network architecture used to classify the output of the 1x2 logic gate.

Figure 9.

Network architecture used to classify the output of the 1x2 logic gate.

Figure 10.

confusion matrix for a classification of a 1x2 logic gate output channels, obtained by the previously trained network.

Figure 10.

confusion matrix for a classification of a 1x2 logic gate output channels, obtained by the previously trained network.

Figure 12.

Figure of Merit for the simulation output obtained by using the optimized MOS arrays. The orange and cyan horizontal lined represents the LOW and HIGH logical threshold.

Figure 12.

Figure of Merit for the simulation output obtained by using the optimized MOS arrays. The orange and cyan horizontal lined represents the LOW and HIGH logical threshold.

Figure 13.

Internal field obtained by using the optimized MOS arrays for each of the logical class. Simulation obtained by BPM (a) and FDTD (b) algorithms. Different from the other plots, Class 1 0 simulated in FDTD, does not show the device boundaries, for a better visual insight.

Figure 13.

Internal field obtained by using the optimized MOS arrays for each of the logical class. Simulation obtained by BPM (a) and FDTD (b) algorithms. Different from the other plots, Class 1 0 simulated in FDTD, does not show the device boundaries, for a better visual insight.

Figure 14.

Internal field of a metaMMI combination used as a 4-bit register writing two binary numbers: 9 and 6 (1001 and 0110, respectively). Simulation obtained with BPM method.

Figure 14.

Internal field of a metaMMI combination used as a 4-bit register writing two binary numbers: 9 and 6 (1001 and 0110, respectively). Simulation obtained with BPM method.

Figure 15.

Internal field of a metaMMI combination used as a 4-bit register writing number: 9 (1001) respectively). Simulation obtained with FDTD method. In (a) is reported the overall file distribution. (b) report a zoom on the output port, with respected dimension proportionality.

Figure 15.

Internal field of a metaMMI combination used as a 4-bit register writing number: 9 (1001) respectively). Simulation obtained with FDTD method. In (a) is reported the overall file distribution. (b) report a zoom on the output port, with respected dimension proportionality.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).