Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

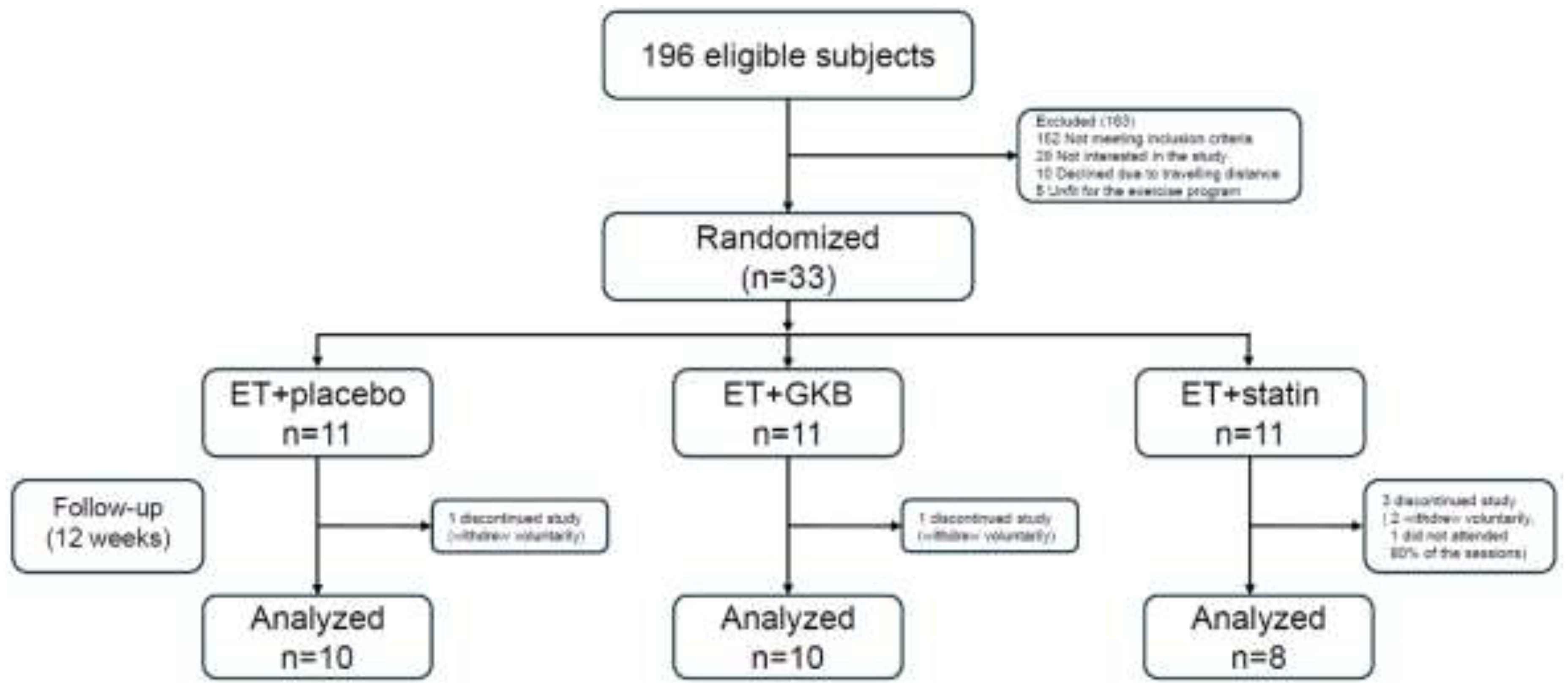

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Approval of the Study

2.2. Randomization and blinding

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Measurements

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marcus, J.L.; Leyden, W.A.; Alexeeff, S.E.; Anderson, A.N.; Hechter, R.C.; Hu, H.; Lam, J.O.; Towner, W.J.; Yuan, Q.; Horberg, M.A.; et al. Comparison of Overall and Comorbidity-Free Life Expectancy Between Insured Adults With and Without HIV Infection, 2000-2016. JAMA Netw Open 2020, 3, e207954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.J.; Westfall, A.O.; Chamot, E.; Willig, A.L.; Mugavero, M.J.; Ritchie, C.; Burkholder, G.A.; Crane, H.M.; Raper, J.L.; Saag, M.S.; et al. T: Patterns in HIV-Infected Patients, 2012.

- Shah, A.S.V.; Stelzle, D.; Lee, K.K.; Beck, E.J.; Alam, S.; Clifford, S.; Longenecker, C.T.; Strachan, F.; Bagchi, S.; Whiteley, W.; et al. Global Burden of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in People Living With HIV. Circulation 2018, 138, 1100–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahani, M.; Mulinder, H.; Farahani, A.; Marlink, R. Prevalence and Distribution of Non-AIDS Causes of Death among HIV-Infected Individuals Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J STD AIDS 2017, 28, 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sax, P.E.; Erlandson, K.M.; Lake, J.E.; McComsey, G.A.; Orkin, C.; Esser, S.; Brown, T.T.; Rockstroh, J.K.; Wei, X.; Carter, C.C.; et al. Weight Gain Following Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy: Risk Factors in Randomized Comparative Clinical Trials. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2020, 71, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, J.E.; Trevillyan, J. Impact of Integrase Inhibitors and Tenofovir Alafenamide on Weight Gain in People with HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2021, 16, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallon, P.W.; Brunet, L.; Hsu, R.K.; Fusco, J.S.; Mounzer, K.C.; Prajapati, G.; Beyer, A.P.; Wohlfeiler, M.B.; Fusco, G.P. Weight Gain before and after Switch from TDF to TAF in a U.S. Cohort Study. J Int AIDS Soc 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.S.; Guerreiro, V.; Carvalho, D.; Serrão, R.; Sarmento, A.; Freitas, P. Metabolically Healthy or Metabolically Unhealthy Obese HIV-Infected Patients: Mostly a Matter of Age? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozemek, C.; Erlandson, K.M.; Jankowski, C.M. Physical Activity and Exercise to Improve Cardiovascular Health for Adults Living with HIV. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2020, 63, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, N.; Cho, H.; Schnall, R. Supervised Physical Activity and Improved Functional Capacity among Adults Living with HIV: A Systematic Review. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2018, 29, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, K.L.; Borges, J.P.; Lopes, G. de O.; Pereira, E.N.G. da S.; Mediano, M.F.F.; Farinatti, P.; Tibiriça, E.; Daliry, A. Influence of Physical Exercise on Advanced Glycation End Products Levels in Patients Living With the Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Front Physiol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Chaparro, C.G.A.; Zech, P.; Schuch, F.; Wolfarth, B.; Rapp, M.; Heiβel, A. Effects of Aerobic and Resistance Exercise Alone or Combined on Strength and Hormone Outcomes for People Living with HIV. A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0203384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.K.; Tynan, A.-M.; Nixon, S.A.; Glazier, R.H. Effectiveness of Aerobic Exercise for Adults Living with HIV: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Using the Cochrane Collaboration Protocol. BMC Infect Dis 2016, 16, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, K.; Naclerio, F.; Karsten, B.; Vera, J.H. Physical Activity and Quality of Life in People Living with HIV. AIDS Care 2019, 31, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancampfort, D.; Mugisha, J.; De Hert, M.; Probst, M.; Firth, J.; Gorczynski, P.; Stubbs, B. Global Physical Activity Levels among People Living with HIV: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Disabil Rehabil 2018, 40, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacka, P.; Adamska, I.; Felisiak, K. The Potential of Ginkgo Biloba as a Source of Biologically Active Compounds—A Review of the Recent Literature and Patents. Molecules 2023, 28, 3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.; Ringstad, L.; Schäfer, P.; Just, S.; Hofer, H.W.; Malmsten, M.; Siegel, G. Reduction of Atherosclerotic Nanoplaque Formation and Size by Ginkgo Biloba (EGb 761) in Cardiovascular High-Risk Patients. Atherosclerosis 2007, 192, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Chai, H.; Lin, P.H.; Lumsden, A.B.; Yao, Q.; Chen, C. Clinical Use and Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Extract of Ginkgo Biloba Leaves in Cardiovascular Diseases. Cardiovasc Drug Rev 2004, 22, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahady, G.B. Ginkgo Biloba for the Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease: A Review of the Literature. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2002, 16, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisvand, F.; Razavi, B.M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. The Effects of Ginkgo Biloba on Metabolic Syndrome: A Review. Phytotherapy Research 2020, 34, 1798–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, L.; Yang, F.; Zhao, X.; Xue, S.; Gong, F. Ginkgo Biloba Extract 50 (GBE50) Ameliorates Insulin Resistance, Hepatic Steatosis and Liver Injury in High Fat Diet-Fed Mice. J Inflamm Res 2021, Volume 14, 1959–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, T.; Hussain, S.; Mahwi, T.; Ahmed, Z.A.; Rahman, H.; Rasedee, A. The Efficacy and Safety of <em>Ginkgo Biloba</Em> Extract as an Adjuvant in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients Ineffectively Managed with Metformin: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Drug Des Devel Ther 2018, Volume 12, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.P.; Rudenski, A.S.; Naylor, B.A.; Treacher, D.F.; Turner, R.C. Homeostasis Model Assessment: Insulin Resistance and ?-Cell Function from Fasting Plasma Glucose and Insulin Concentrations in Man. Diabetologia 1985, 28, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julious, S.A. Sample Size of 12 per Group Rule of Thumb for a Pilot Study. Pharm Stat 2005, 4, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahat, F.M.; Alghamdi, Y.S.; Farahat, A.F.; Alqurashi, A.A.; Alburayk, A.K.; Alabbasi, A.A.; Alsaedi, A.A.; Alshamrani, M.M. The Prevalence of Comorbidities among Adult People Diagnosed with HIV Infection in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Western Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health 2020, 13, 1699–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, P.D.; Buchner, D.; Piña, I.L.; Balady, G.J.; Williams, M.A.; Marcus, B.H.; Berra, K.; Blair, S.N.; Costa, F.; Franklin, B.; et al. Exercise and Physical Activity in the Prevention and Treatment of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2003, 107, 3109–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossomanno, C.I.; Herrick, J.E.; Kirk, S.M.; Kirk, E.P. A 6-Month Supervised Employer-Based Minimal Exercise Program for Police Officers Improves Fitness. J Strength Cond Res 2012, 26, 2338–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, N.; Cho, H.; Schnall, R. Supervised Physical Activity and Improved Functional Capacity among Adults Living with HIV: A Systematic Review. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2018, 29, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancampfort, D.; Mugisha, J.; Richards, J.; De Hert, M.; Lazzarotto, A.R.; Schuch, F.B.; Probst, M.; Stubbs, B. Dropout from Physical Activity Interventions in People Living with HIV: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AIDS Care 2017, 29, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutimura, E.; Crowther, N.J.; Cade, T.W.; Yarasheski, K.E.; Stewart, A. Exercise Training Reduces Central Adiposity and Improves Metabolic Indices in HAART-Treated HIV-Positive Subjects in Rwanda: A Randomized Controlled Trial. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2008, 24, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.A.; Neidig, J.L.; Nickel, J.T.; Mitchell, G.L.; Para, M.F.; Fass, R.J. Aerobic Exercise: Effects on Parameters Related to Fatigue, Dyspnea, Weight and Body Composition in HIV-Infected Adults. AIDS 2001, 15, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, H.R.; da Cruz, L.G.; Lourenço, C.L.M.; Neves, F. de F.; Silva-Vergara, M.L.; Mendes, E.L. Non-linear Resistance Training Reduces Inflammatory Biomarkers in Persons Living with HIV: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur J Sport Sci 2016, 16, 1232–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito-Neto, J.G. de; Andrade, M.F. de; Almeida, V.D. de; Paiva, D.C.C.; Morais, N.M. de; Bezerra, C.M.; Fernandes, J.V.; Nascimento, E.G.C. do; Fonseca, I.A.T.; Fernandes, T.A.A. de M. Strength Training Improves Body Composition, Muscle Strength and Increases CD4+ T Lymphocyte Levels in People Living with HIV/AIDS. Infect Dis Rep 2019, 11, 7925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes Neto, M.; Conceição, C.S.; Carvalho, V.O.; Brites, C. Effects of Combined Aerobic and Resistance Exercise on Exercise Capacity, Muscle Strength and Quality of Life in HIV-Infected Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0138066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrón-Cabrera, E.; Soria-Rodríguez, R.; Amador-Lara, F.; Martínez-López, E. Physical Activity Protocols in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Management: A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials and Animal Models. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, A.D.; Peters, B.S.; Rivas, C.; Goff, L.M. Reducing Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in <scp>HIV</Scp> : A Mixed-methods Investigation of the <scp>STOP</Scp> -Diabetes Diet and Physical Activity Intervention. Diabetic Medicine 2020, 37, 1705–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oursler, K.K.; Sorkin, J.D.; Ryan, A.S.; Katzel, L.I. A Pilot Randomized Aerobic Exercise Trial in Older HIV-Infected Men: Insights into Strategies for Successful Aging with HIV. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0198855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Lepe, M.A.; Ortiz-Ortiz, M.; Hernández-Ontiveros, D.A.; Mejía-Rangel, M.J. Inflammatory Profile of Older Adults in Response to Physical Activity and Diet Supplementation: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Chaparro, C.G.A.; Zech, P.; Schuch, F.; Wolfarth, B.; Rapp, M.; Heiβel, A. Effects of Aerobic and Resistance Exercise Alone or Combined on Strength and Hormone Outcomes for People Living with HIV. A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0203384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, G.; Pinacchio, C.; Santinelli, L.; Adami, P.E.; Borrazzo, C.; Cavallari, E.N.; Vullo, A.; Innocenti, G. Pietro; Mezzaroma, I.; Mastroianni, C.M.; et al. Physical Activity and HIV: Effects on Fitness Status, Metabolism, Inflammation and Immune-Activation. AIDS Behav 2020, 24, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenciner, L.; Barber, T.J. Non-Infective Complications for People Living with HIV. Medicine 2022, 50, 304–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, N.L.; Netangaheni, T.R. Risks of Type 2 Diabetes among Older People Living with HIV: A Scoping Review. South African Family Practice 2023, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudolo, G.B. The Effect of 3-Month Ingestion of Ginkgo Biloba Extract (EGb 761) on Pancreatic Β-Cell Function in Response to Glucose Loading in Individuals with Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2001, 41, 600–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Meng, Q.; Qian, T.; Yang, Z. Ginkgo Biloba Extract Enhances Glucose Tolerance in Hyperinsulinism-Induced Hepatic Cells. J Nat Med 2011, 65, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, N.; Tobe, K.; Terauchi, Y.; Eto, K.; Yamauchi, T.; Suzuki, R.; Tsubamoto, Y.; Komeda, K.; Nakano, R.; Miki, H.; et al. Disruption of Insulin Receptor Substrate 2 Causes Type 2 Diabetes Because of Liver Insulin Resistance and Lack of Compensatory Beta-Cell Hyperplasia. Diabetes 2000, 49, 1880–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, T.; Hussain, S.; Mahwi, T.; Ahmed, Z.A.; Rahman, H.; Rasedee, A. The Efficacy and Safety of <em>Ginkgo Biloba</Em> Extract as an Adjuvant in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients Ineffectively Managed with Metformin: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Drug Des Devel Ther 2018, Volume 12, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Agli, M.; Bosisio, E. Biflavones of Ginkgo Biloba Stimulate Lipolysis in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Planta Med 2002, 68, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, G.; Ermilov, E.; Knes, O.; Rodríguez, M. Combined Lowering of Low Grade Systemic Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Metabolic Syndrome Patients Treated with Ginkgo Biloba. Atherosclerosis 2014, 237, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonora, E.; Kiechl, S.; Willeit, J.; Oberhollenzer, F.; Egger, G.; Meigs, J.B.; Bonadonna, R.C.; Muggeo, M. Insulin Resistance as Estimated by Homeostasis Model Assessment Predicts Incident Symptomatic Cardiovascular Disease in Caucasian Subjects From the General Population. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuliani, G.; Morieri, M.L.; Volpato, S.; Maggio, M.; Cherubini, A.; Francesconi, D.; Bandinelli, S.; Paolisso, G.; Guralnik, J.M.; Ferrucci, L. Insulin Resistance and Systemic Inflammation, but Not Metabolic Syndrome Phenotype, Predict 9 Years Mortality in Older Adults. Atherosclerosis 2014, 235, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausk, K.J.; Boyko, E.J.; Ioannou, G.N. Insulin Resistance Predicts Mortality in Nondiabetic Individuals in the U.S. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaha, M.J.; DeFilippis, A.P.; Rivera, J.J.; Budoff, M.J.; Blankstein, R.; Agatston, A.; Szklo, M.; Lakoski, S.G.; Bertoni, A.G.; Kronmal, R.A.; et al. The Relationship Between Insulin Resistance and Incidence and Progression of Coronary Artery Calcification. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 749–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banin, R.M.; Hirata, B.K.S.; Andrade, I.S.; Zemdegs, J.C.S.; Clemente, A.P.G.; Dornellas, A.P.S.; Boldarine, V.T.; Estadella, D.; Albuquerque, K.T.; Oyama, L.M.; et al. Beneficial Effects of Ginkgo Biloba Extract on Insulin Signaling Cascade, Dyslipidemia, and Body Adiposity of Diet-Induced Obese Rats. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 2014, 47, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H. Hypocholesterolemic Effect of Ginkgo Biloba Seeds Extract from High Fat Diet Mice. Biomedical Science Letters 2017, 23, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, B.K.S.; Cruz, M.M.; de Sá, R.D.C.C.; Farias, T.S.M.; Machado, M.M.F.; Bueno, A.A.; Alonso-Vale, M.I.C.; Telles, M.M. Potential Anti-Obesogenic Effects of Ginkgo Biloba Observed in Epididymal White Adipose Tissue of Obese Rats. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, G.; A, J.; Wu, D.; Zhu, L.; Ma, B.; Du, Y. Application of GC/MS-Based Metabonomic Profiling in Studying the Lipid-Regulating Effects of Ginkgo Biloba Extract on Diet-Induced Hyperlipidemia in Rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2009, 30, 1674–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, L.; Hai, H. Clinical Observation of Gingko Biloba Extract Injection in Treating Early Diabetic Nephropathy. Chin J Integr Med 2005, 11, 226–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Liang, B.; Li, Y. Antihyperglycemic Effect of Ginkgo Biloba Extract in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes in Rats. Biomed Res Int 2013, 2013, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, H.R.; Gonçalves, A.; Teixeira Paranhos Lopes, L.; Mendes, E.L.; Roever, L.; Silva-Vergara, M.L.; Neves, F.F.; Resende, E.S. Effects of Exercise Training and Statin Use in People Living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus with Dyslipidemia. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2020, 52, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | ET + Placebo n=10 |

ET+ GKB n=10 |

ET+ Statin n=8 |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 41.8 ±11.0 | 41.8 ±7.0 | 40.5 ±10.5 | 0.949 |

| Weight (kg) | 80.7 ±13.3 | 75.9 ±12.4 | 76.2 ±12.5 | 0.277 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 91.6 ±13.6 | 90.0 ±10.5 | 87.2 ±6.5 | 0.695 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.90 ±0.10 | 0.95 ±0.07 | 0.90 ±0.05 | 0.253 |

| Waist-to-height ratio | 0.53 ±0.08 | 0.53 ±0.08 | 0.52 ±0.04 | 0.906 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.0 ±4.1 | 26.6 ±4.2 | 25.7 ±2.6 | 0.854 |

| Sum of 8 skinfolds (mm) | 118.8 ±47.7 | 127.6 ±40.8 | 129.6 ±43.9 | 0.855 |

| Body fat mass (%) | 26.0±5.5 | 24.9±4.2 | 25.7±2.6 | 0.854 |

| Lean body mass (%) | 39.0 ±6.4 | 40.3 ±4.9 | 40.2 ±3.4 | 0.827 |

| Bone mass (%) | 13.7 ±1.4 | 14.3 ±1.5 | 14.2 ±0.8 | 0.560 |

| Absolute CD4+ T Cell count/μl, mean | 534.3 ±310.4 | 694.2 ±310.1 | 570.6 ±154.6 | 0.171 |

| HIV-1 RNA (copies/mL), mean | 180.6 ±466.8 | 2,169.4±6,756.9 | 35.0 ±4.3 | 0.764 |

| Total, billirrubin (mg/dL) | 0.80 ±0.4 | 0.63 ±0.2 | 0.58 ±0.2 | 0.683 |

| Direct billirrubin (mg/dL) | 0.14 ±0.05 | 0.11 ±0.03 | 0.11 ±0.06 | 0.335 |

| Total, protein (g/dL) | 7.2 ±0.5 | 7.2 ±0.4 | 7.1 ±0.3 | 0.933 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.2 ±0.1 | 4.2 ±0.2 | 4.3 ±0.2 | 0.518 |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 3.1 ±0.5 | 2.9 ±0.4 | 2.7 ±0.4 | 0.374 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 31.8 ±11.2 | 36.8 ±55.0 | 18.7 ±5.4 | 0.024* |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 22.0 ±5.9 | 30.1 ±29.0 | 17.2 ±4.5 | 0.061 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (IU/L) | 45.8 ±31.0 | 35.7 ±32.4 | 27.3 ±15.7 | 0.273 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 79.7 ±21.4 | 73.6 ±14.8 | 69.2 ±19.5 | 0.533 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 159.1 ±35.7 | 174.1 ±41.2 | 156.8 ±22.7 | 0.514 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 34.0 ±10.9 | 28.3 ±7.7 | 41.2 ±11.2 | 0.039* |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 15.8 ±5.0 | 13.2 ±3.5 | 19.3 ±3.5 | 0.035* |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.91 ±0.12 | 0.096 ±0.12 | 1.04 ±0.19 | 0.213 |

| Prothrombin time | 10.8 ±0.9 | 11.0 ±0.4 | 10.7 ±0.6 | 0.824 |

| INR | 0.97 ±0.09 | 1.00 ±0.04 | 0.93 ±0.08 | 0.258 |

| Partial thromboplastin time | 32.4 ±2.5 | 33.6 ±4.5 | 31.4 ±2.7 | 0.487 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 421.4 ±73.9 | 459.0 ±93.6 | 422.6 ±82.9 | 0.559 |

| Characteristics | ET + Placebo n=10 |

ET+ GKB n=10 |

ET+ Statin n=8 |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

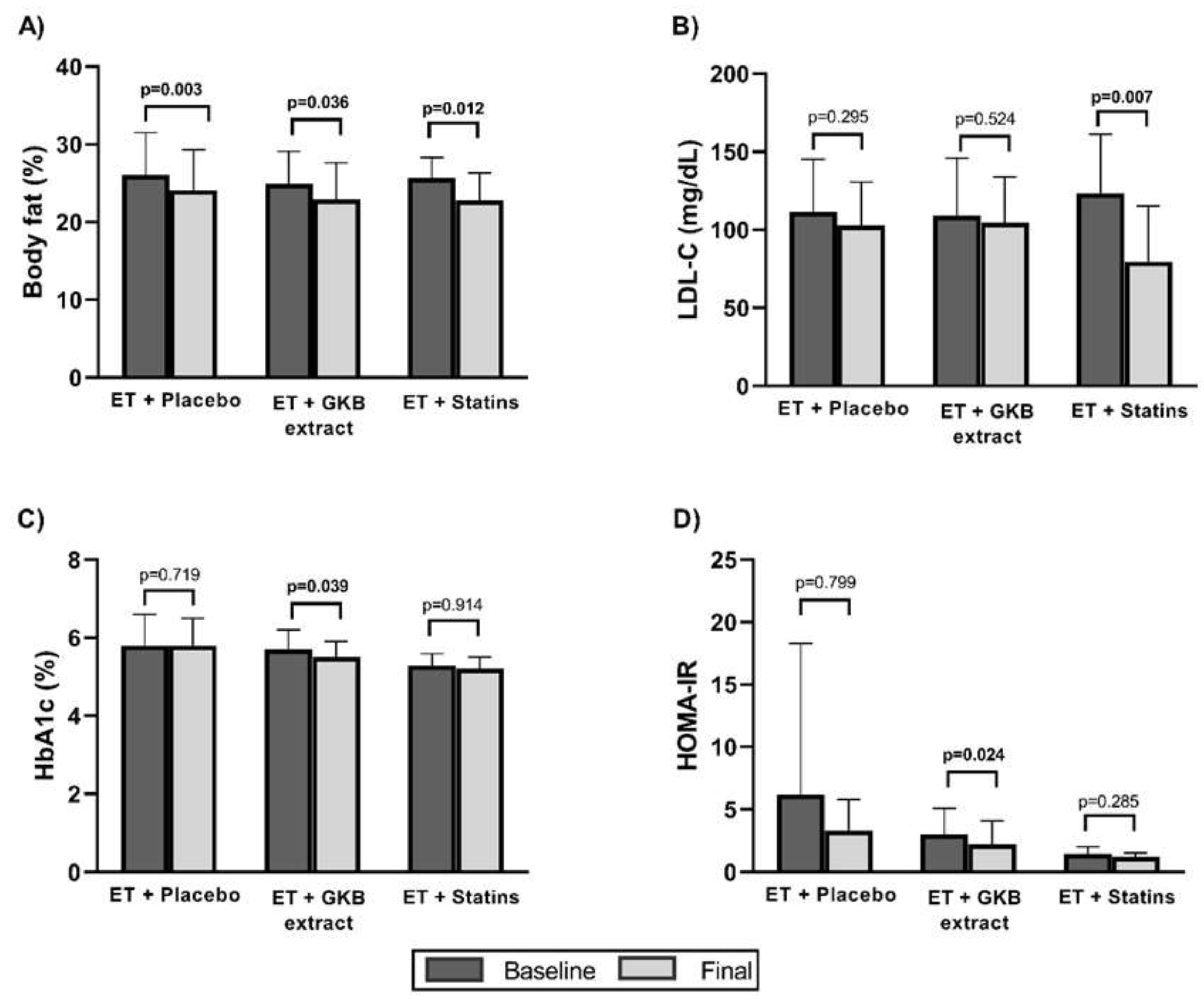

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | -11.5 ±33.2 | -12.3 ±20.9 | -53.7 ±63.9 | 0.044* |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.5 ±9.1 | 2.1 ±3.5 | 1.8 ±7.9 | 0.882 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | -8.9 ±25.3 | -4.3 ±20.5 | -44.0 ±32.5 | 0.426 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | -9.5 ±93.9 | -27.0 ±90.1 | -0.8 ±141.5 | 0.522 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | -5.9 ±22.2 | -2.4 ±11.1 | -2.6 ±19.6 | 0.687 |

| Insulin (µU/mL) | -4.4 ±20.5 | -3.0 ±2.7 | -0.9 ±2.2 | 0.107 |

| Glycated hemoglobin A1c (%) | -0.0 ±0.2 | -0.1 ±0.2 | 0.0 ±0.2 | 0.340 |

| HOMA-IR† | -2.9 ±10.0 | -0.7 ±0.7 | -0.2 ±0.5 | 0.119 |

| Triglycerides/HDL-c ratio | 0.1 ±2.6 | -1.4 ±3.0 | -0.6 ±3.4 | 0.903 |

| Variable | ET+ Placebo n=10 |

ET+ GKB n=10 |

ET+ Statin n=8 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal | Final | p vale | Basal | Final | p value | Basal | Final | p value | |

| VO2Máx† | 47.9 ±5.3 | 59.9 ±8.9 | 0.001** | 46.5 ±10.1 | 55.0 ±7.4 | 0.002** | 45.0 ±4.2 | 58.9 ±7.0 | 0.000*** |

| Grip strength in non-dominant hand (Kg) | 31.2 ±5.4 | 33.3 ±9.0 | 0.333† | 61.9 ±90.1 | 33.4 ±4.9 | 0.674† | 34.2 ±8.6 | 346 ±6.4 | 0.838 |

| Grip strength in dominant hand (Kg) | 33.7 ±8.6 | 33.3 ±11.9 | 0.849 | 34.4 ±4.1 | 35.6 ±6.1 | 0.380 | 35.6 ±6.1 | 37.8 ±6.1 | 0.297 |

| Back strength (Kg) | 36.5 ±20.7 | 42.8 ±18.1 | 0.272 | 32.6 ±11.4 | 40.0 ±12.9 | 0.025* | 39.3 ±18.1 | 39.2 ±15.0 | 0.978 |

| Lower limb strength (Kg) | 37.7 ±13.6 | 42.8 ±16.0 | 0.434 | 35.4 ±14.3 | 40.0 ±14.7 | 0.161 | 36.5 ±18.2 | 39.3 ±14.3 | 0.635 |

| Flexibility (cm) | 24.3 ±10.4 | 24.5 ±10.1 | 0.908 | 16.1 ±7.4 | 17.5 ±8.3 | 0.608 | 19.3 ±7.8 | 25.0 ±7.5 | 0.027* |

| Balance | 6.2 ±5.1 | 3.3 ±3.1 | 0.053 | 2.3 ±3.3 | 1.5 ±2.5 | 0.461† | 5.6 ±5.7 | 4.7 ±5.5 | 0.570 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).