1. Introduction

Mental health during COVID-19 declined in populations in Canada; incidence of depression, anxiety [

1] and suicidal ideation increased [

2], demonstrating a need for improved access to care. Populations living in rural areas, in comparison to urban populations, had a higher risk burden as mental health resources were strained[

3]. Urban areas had high COVID-19 case counts and accounted for most cases in Ontario[

4], however, Ontario rural areas suffered[

5]. Gender inequities in division of household work were magnified during COVID-19, with women facing increased in household work and childcare [

6]. Working women experienced greater career disruptions in comparison to men [

6,

7]. Quarantine caused reported increases in intimate partner violence [

8]. Mental health in rural areas of Ontario [

5] and across Canada declined as a result of social isolation and reduced social support [

9]. The relationship between rural mental health and COVID-19 has not yet been explored in the context of gender in Ontario. Rural populations faced unique challenges during COVID-19. This analysis will investigate how COVID-19 impacted perceived mental health and if that perception differed between men and women living in seven rural Ontario counties.

Declining mental health in women as a result of COVID-19 has been studied provincially [

10,

11] and nationally. Few studies, however, have examined the intersection of gender, rurality, and mental health in Ontario [

12].

1.1. Rural Ontario & COVID-19

In a study of ten Ontario workers, lack of regulatory support, structural support (i.e., policy or management), and gender biases were identified as barriers to reception of adequate protections from COVID-19 [

13]. Female workers reported distress as a result of their caretaking responsibilities at home and work – fearing they were putting those in their care at risk [

13]. Cleaning protocols for COVID-19 in health care were reported to be inconsistent, sometimes changing daily, increasing lack of confidence in protective measures [

13]. In rural Ontario, between May 2021 and August 2021 physicians self-reported increases in changes in depression and anxiety and decline in well-being due to increased infection risk, lack of resources, and care demands [

14]. Burnout (defined as chronic workplace stress) [

15] in healthcare providers has been associated with poorer healthcare delivery [

14].

Ontario studies have explored substance use and rural health outcomes during COVID-19. There appeared to be an increase in disparities of alcohol related hospitalizations (all-cause ED visits) between urban and rural areas, with rural areas having a higher rate of admissions [

16]. During the pandemic there was a decline for both men and women in hospital admissions due to alcohol use, possibly signaling disinclination to utilize healthcare [

16]. Health care utilization did not decline in rural areas as much as urban areas – indicating healthcare access may not have been a driving force of alcohol related ED visits; unique characteristics of rural communities may have led to increased substance use [

16].

Rural Ontarians may have suffered from COVID-19’s economic impacts. Policies for controlling COVID-19 were developed for urban regions; lockdowns were implemented in rural areas - despite having lower COVID-19 cases. Lockdowns impacted small businesses and local economies; straining the gap between individuals shopping locally versus shopping at big box stores [

17]. To account for inequities between urban and rural, it has been suggested interventions are more geographically specific [

18].

Internationally, there are distinctive social and structural dynamics in rural communities. In the United States, at one point, rural communities were the epicenter of COVID-19; reflecting a need for an increase in healthcare resources [

19]. Qualitative research conducted in Melbourne, Australia reflects that specifically females in rural areas needed more resources during COVID-19 [

20]. In Bcharra, Lebanon, the rurality of the community is what strengthened COVID-19 response, as the relationships community leaders developed were leveraged for participation in pandemic response [

21]. Each citizen of Bcharra participated in pandemic response. The pandemic response framework was formed immediately and within the context of the area [

21]. Techniques within reach of smaller communities included contact tracing and concise protocol development (as rural areas had a delayed onset of cases) [

21].

1.2. Gender & COVID-19

Gender disparities during COVID-19 were a consistent theme. Trouble connecting, burden of care, and financial struggles were among the themes impacting workers at intimate partner violence (IPV) centres during COVID-19 [

22]. Management and staff reported experiencing additional burdens at home as a result of school and daycare closures [

22]. The need for IPV support during COVID-19 increased, leading to burnout of IPV service providers [

22]. Many women’s careers during COVID-19 suffered because of increased household burdens. Canadian mothers reported approximately 30 additional hours of childcare per week. Women in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) mostly worked from home (~70%) and 22% reported spending more than 3 hours per day on childcare (in comparison to men who reported 12%) [

23]. Women working in academia reported significant gender-based challenges (~20%), in comparison to men who reported ~13% [

23]. Women in earlier career stages (e.g., postdoctoral fellow or other early career scientists) may have been most impacted by this childcare gap, as they are most likely to have young children [

24]. Young children combined with the need for productivity during these formative career stages may have furthered gender gaps in academia. In British Columbia, Canada, mothers reported feeling like ‘bad moms’ in response to juggling household tasks and childcare [

25].

IPV was heightened during COVID-19, with support services across Canada and within Ontario reporting an increased rate of IPV [

26]. Men and women reported heightened concern of physical and emotional abuse, in one case, men reported being more concerned about this than women surveyed [

27]. Support resources for IPV were limited by stay-at-home orders, leaving providers to hide their own home to provide confidential care [

22], while IPV survivors struggled to access virtual appointments due to privacy concerns [

28]. Patterns of violence against women and IPV were examined with twitter data; women were identified as having experienced disproportionate violence [

29]. IPV providers reported four main themes of IPV during COVID-19: no escape, isolation, complex decision making, and increased vulnerability [

30]. These themes illustrate IPV supports for women were less accessible.

1.3. Mental Health & COVID-19

Canadian adults’ average self-reported mental health score during COVID-19 was lower than the average prior to the pandemic [

31]. Some adults in Canada reported an increase in junk food intake and no recreational physical activity [

31], indicating self-care behaviors may have declined during COVID-19. The proportion of all-cause emergency admissions attributed to alcohol increased during the first six months of COVID-19, although the proportion of alcohol related admissions declined [

16]. Hospital visits for acute alcohol poisoning decreased, and there was a decrease in visits for chronic alcohol use, although to a lesser extent, and in some instances, an increase [

16]. In rural Ontario, alcohol related emergency visit rates remained stable in comparison to pre-pandemic visits [

16]. Non-physician provided mental health care is not covered by Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP), leaving many without access to mental health support [

32].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area & Sample

Residents aged 18 or older living in Bruce (population density per square kilometer (pop/km2): 18.0, total population (pop): 73,396), Dufferin (pop/km2: 44.6, pop: 66,257), North Durham (only three municipalities: Scugog, Uxbridge, Brock, pop: 55,704), Elgin (pop/km2: 50.4, pop: 94,752), Grey (pop/km2: 22.4, pop: 100,905), Middlesex (pop/km2: 150.9, pop: 78,239), and Oxford (pop/km2: 59.7, pop: 121,781) were included [

33]. These counties are rural, with population densities less than 400 people per square kilometer [

34].

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Survey Data

A cross-sectional survey was designed to establish topics relevant to rural experiences. The survey questions on health were based on the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS) Health Survey for England [

35]. An advisory board of six individuals working in local government, health units, non-profit, or service provisions, reviewed the proposed topics and provided feedback. Experts in the topic areas selected were asked to provide input. The survey was finalized with five main subjects of interest: demographics, individual well-being, social behaviour, mental health, and risk planning. A pilot was distributed to Perth and Huron Counties and responses were collected between August and November 2020 [

5].

After the pilot survey study, the survey was revised to include additional questions (e.g., childcare). Pilot work was presented at Western Ontario Wardens Caucus and counties were offered survey access. County selection within the caucus was limited by funding, therefore the seven first counties to request the survey were selected for participation. Surveys for these rural western Ontario counties were distributed via Canada Post and online. Data were collected from September 2021 to November 2021. Surveys were mailed to each known individual residence within the study areas. The question on gender, was asked as ‘How do you describe your gender?’. The responses available were man, woman, non-binary, and ‘I use a different pronoun or prefer not to answer”.

2.2.2. Census Data

Census data were collected from the University of Toronto Computing in the Social Sciences and Humanities (CHASS) Data Centre [

33]. The 2021 Canadian census year was selected as it was the closest census year to the year of survey collection. While CHASS has variables on biological sex, the census’ newly introduced gender measures were not available via CHASS.

2.2.3. COVID-19 Data

COVID-19 case data were collected through Ontario’s Case and Contact Management system (CCM) [

36]. The data were limited to the start of COVID-19 to the end of the study period (November 2021), then aggregated to a count of total cases per study county. Case rates were derived by dividing the number of total cases for the period by the county population multiplied by 100,000.

2.3. Statistical Methods

2.3.1. Data Cleaning & Summary Statistics

Data were aggregated into one Stata dataset per county and then analyzed with R-Statistical Programming Software (R) [

37]. Responses were compiled into one dataset for analysis. Survey participants who did not respond to the gender portion of the survey OR responded as a gender other than man or woman were excluded. There was not a large enough sample to explore inequities of those respondents identifying as gender queer.

The selected outcome of interest was the survey question ‘How would you rate your mental health?’ for both the before COVID-19 section of the analysis and after COVID-19. If a respondent selected poor mental health, they were coded as ‘cases’ or ‘1’, if a respondent selected excellent, good, average, or satisfactory, then they were coded as ‘controls’ or ‘0’. Non-response to this question resulted in exclusion.

Survey sample alignment to population was estimated by comparing the demographic measurements of the counties to Census demographic measurements. The census data was compared at the county level, except for Durham County, which was estimated using the population totals from the three municipalities surveyed (Scugog, Uxbridge, and Brock). The survey sample was divided into a sample of men and a sample of women for comparison of survey responses, differences in responses were measured via chi-squared test. If estimates significantly differed, they were included in the final statistical models.

2.3.2. Data Visualization

Study areas, odds ratios for each county, and COVID-19 case rates for the survey period were visualized to identify spatial relationships in the data using ArcGIS Pro and R. Shapefiles were obtained from Statistics Canada [

38]. Maps were formatted in the projection Lambert Conformal Conic, the projection utilized by Statistics Canada [

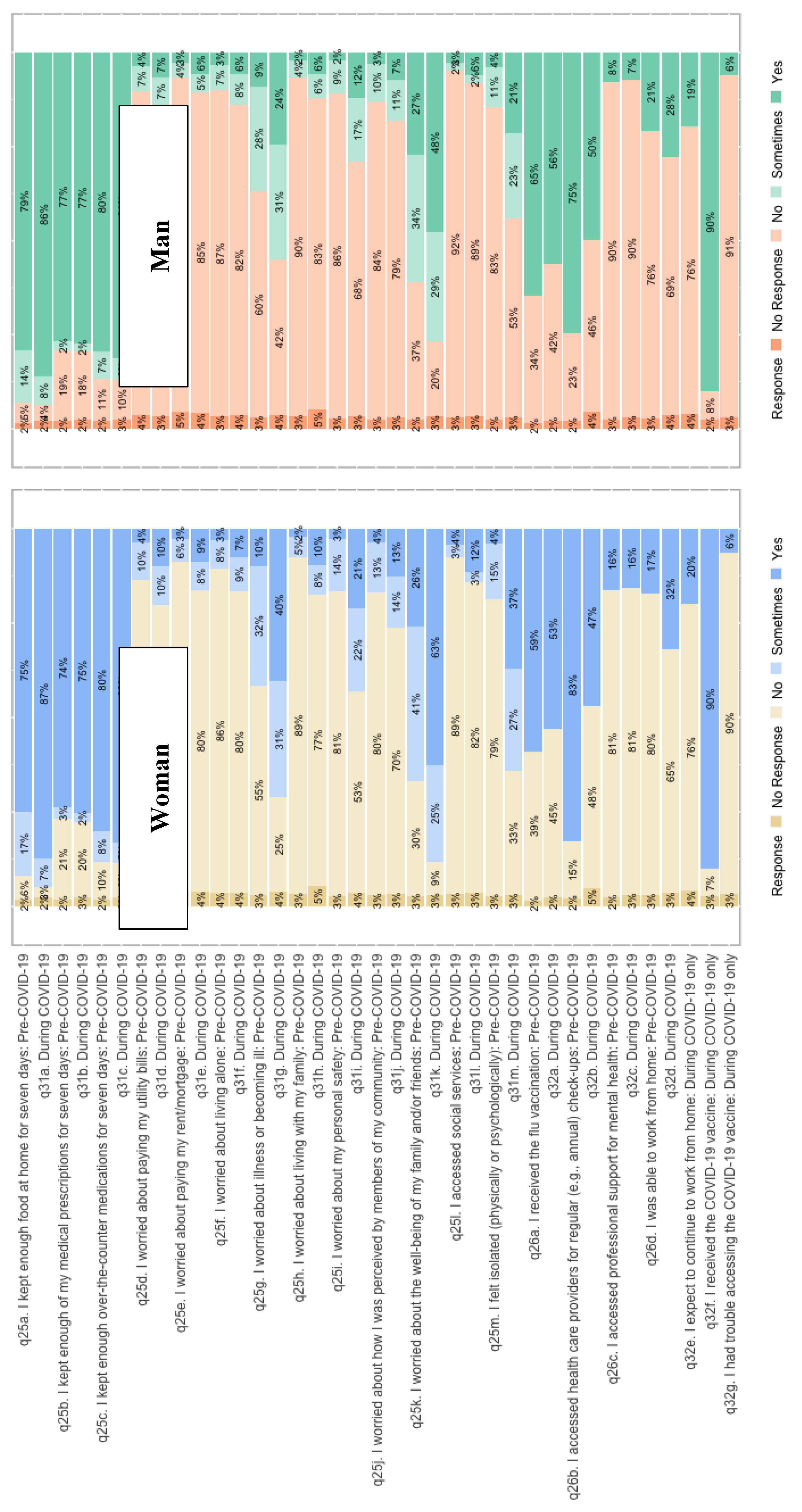

39]. Stacked bar charts were created to visualize differing proportions of responses for men and women prior to and during COVID-19.

2.3.3. Statistical Models

To evaluate differences in COVID-19 mental health by gender, unadjusted odds-ratios were calculated for each county and overall using the formula OR = AD/BC, where A is exposure and event occurrence, B is exposure but no event occurrence, C is no exposure and event occurrence, and D is no exposure and no event occurrence. Exposure was the gender ‘woman’, and the event was self-report of ‘poor mental health’; men were considered the ‘unexposed’ group. Logistic regression models were used to produce adjusted odds ratios. Covariates were selected using the results found in table 2; variables that significantly differed (p-value < 0.05) between men and women were included as a covariate, apart from housing situation and number of people in household. Housing situation was significantly associated with income (chi-squared test of independence, P<0.05) and number of people in household was significantly associated with dependents in the home (chi-squared test of independence, P<0.05).

Ethnicity, Education, and Primary Income (i.e., employment) had greater than 5% of data missing, they were imputed using the RStudio Package ‘missMDA’, a package developed for imputing categorical data using Multifactor Correspondence Analysis (MCA) [

40]. Children and other dependents were also included because they differed geographically.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

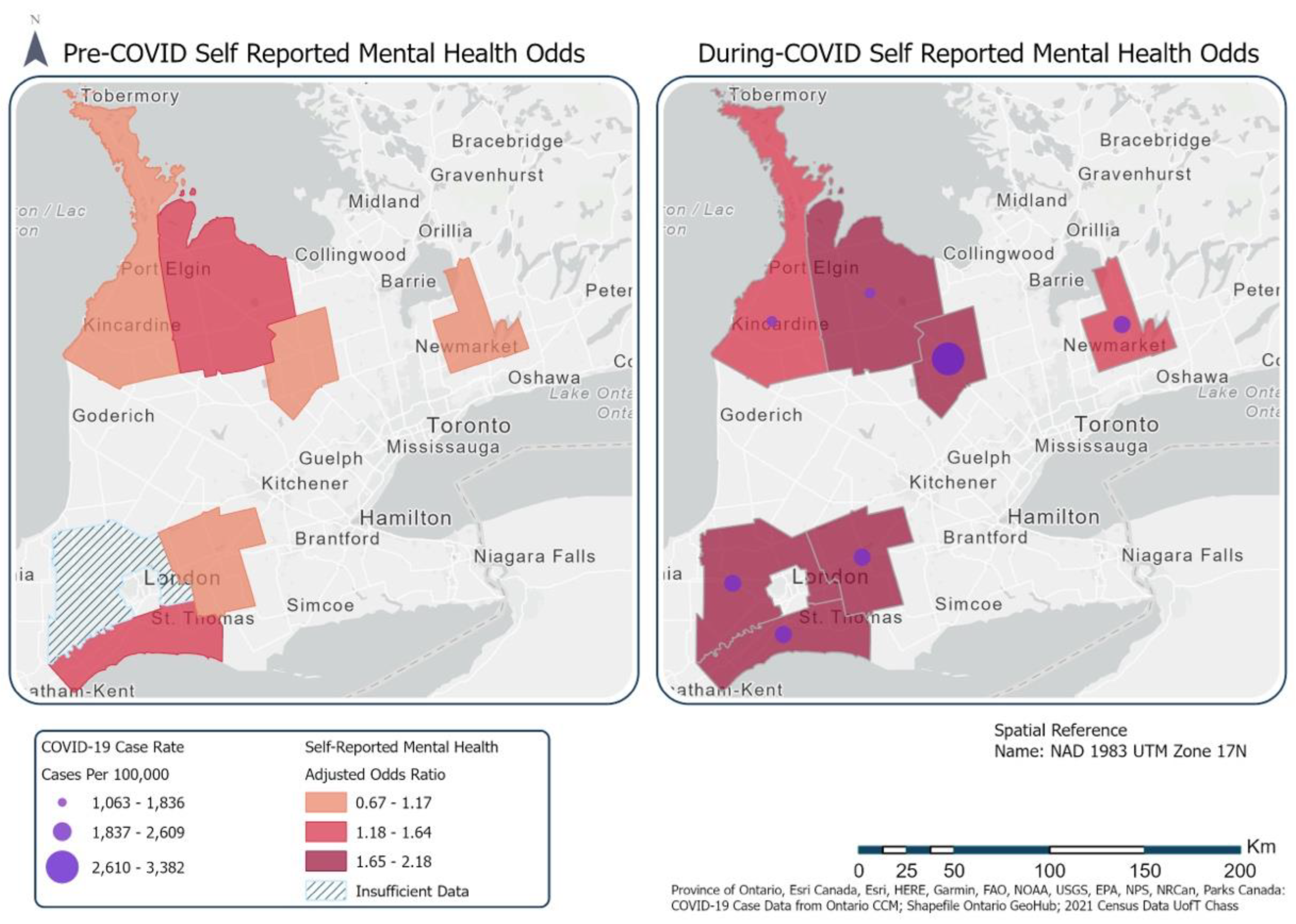

The study area (

Figure 1) shows each county represented by a different color. The study area is spatially discontinuous, although most counties, except for Durham, share a border with at least one other county in the study. There were 18,864 survey respondents and out of those, 11,978 reported their gender as woman and 6,211 reported their gender as man; these samples were sufficiently large and were retained in the study sample. In contrast, 32 respondents reported non-binary, 54 indicated preference not to disclose, and 589 respondents did not respond to the question.

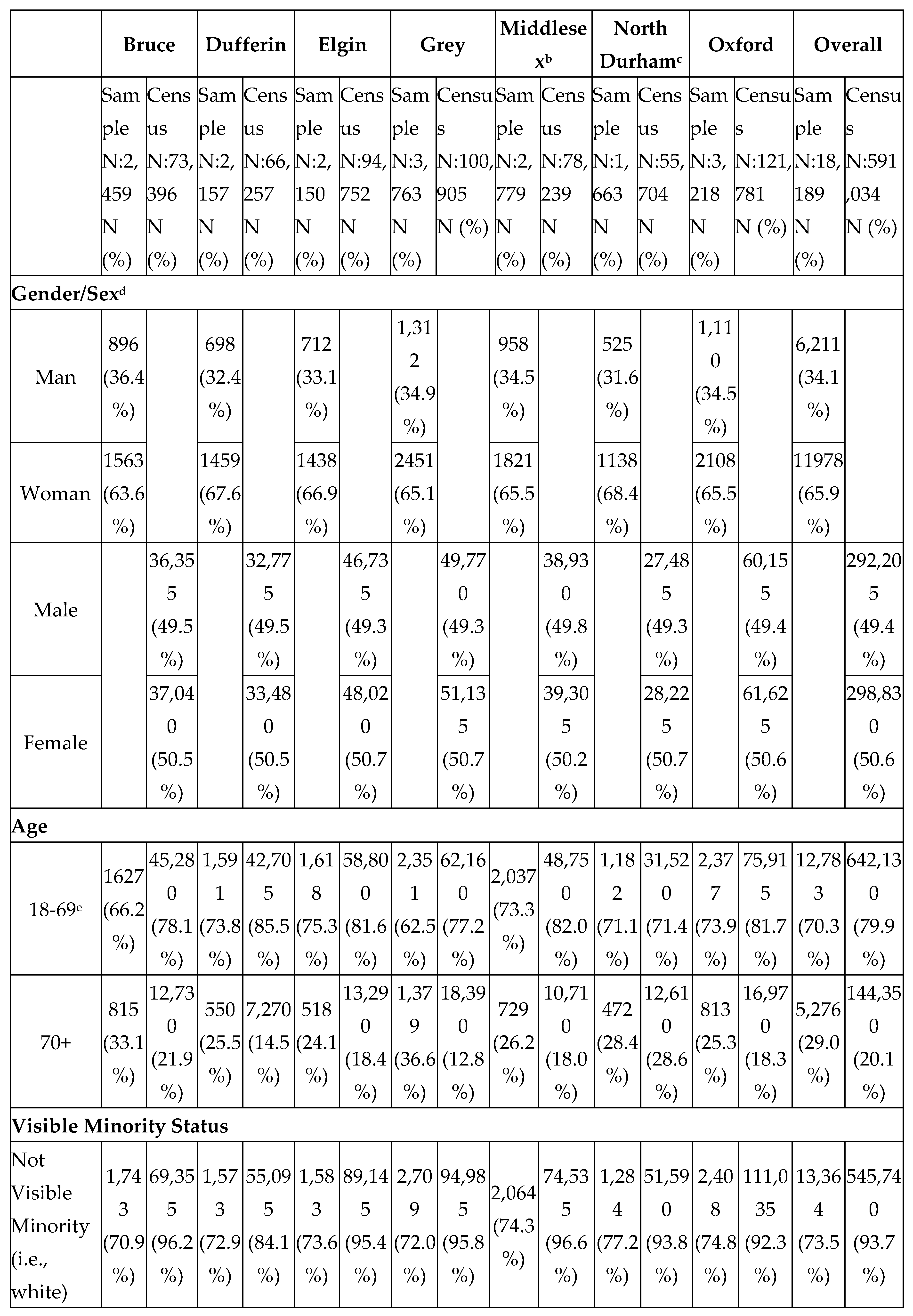

The counties’ study sample does not completely align with the census county populations (

Table 1). Gender identity was not available at the census division and subdivision level [

33], so the proportions of gender were compared to sex. The census sample shows there are more females (50.6%) than males (49.4%) in the counties studied. The survey sample is unbalanced, with most respondents identifying as women (65.9%) and only (34.1%) identifying as men. The age distribution of the sample varied geographically, with Elgin County having the highest percentage of (75.3%) adults less than 70, and Grey County having the highest percentage of (36.6%) adults aged 70 or more. In contrast, the census sample’s highest percentage of adults less than 70 was in Elgin County (85.5%) and the highest percentage of adults aged greater than 70 was in North Durham (28.6%). The age distribution (

Table 1) of the sample is older (29% being older than 70) than the census (20.1% of the population was over 70).

Visible minorities were slightly overrepresented in this sample (identified as a visible minority was 8.0%) in comparison to the census (identified as a visible minority was 6.3%). Approximately 20% of the survey sample did not respond to this question. Educational attainment distributions differed between the census and the sample. In the survey sample over 70% of respondents obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher; only 46.3% of the census population achieved this.

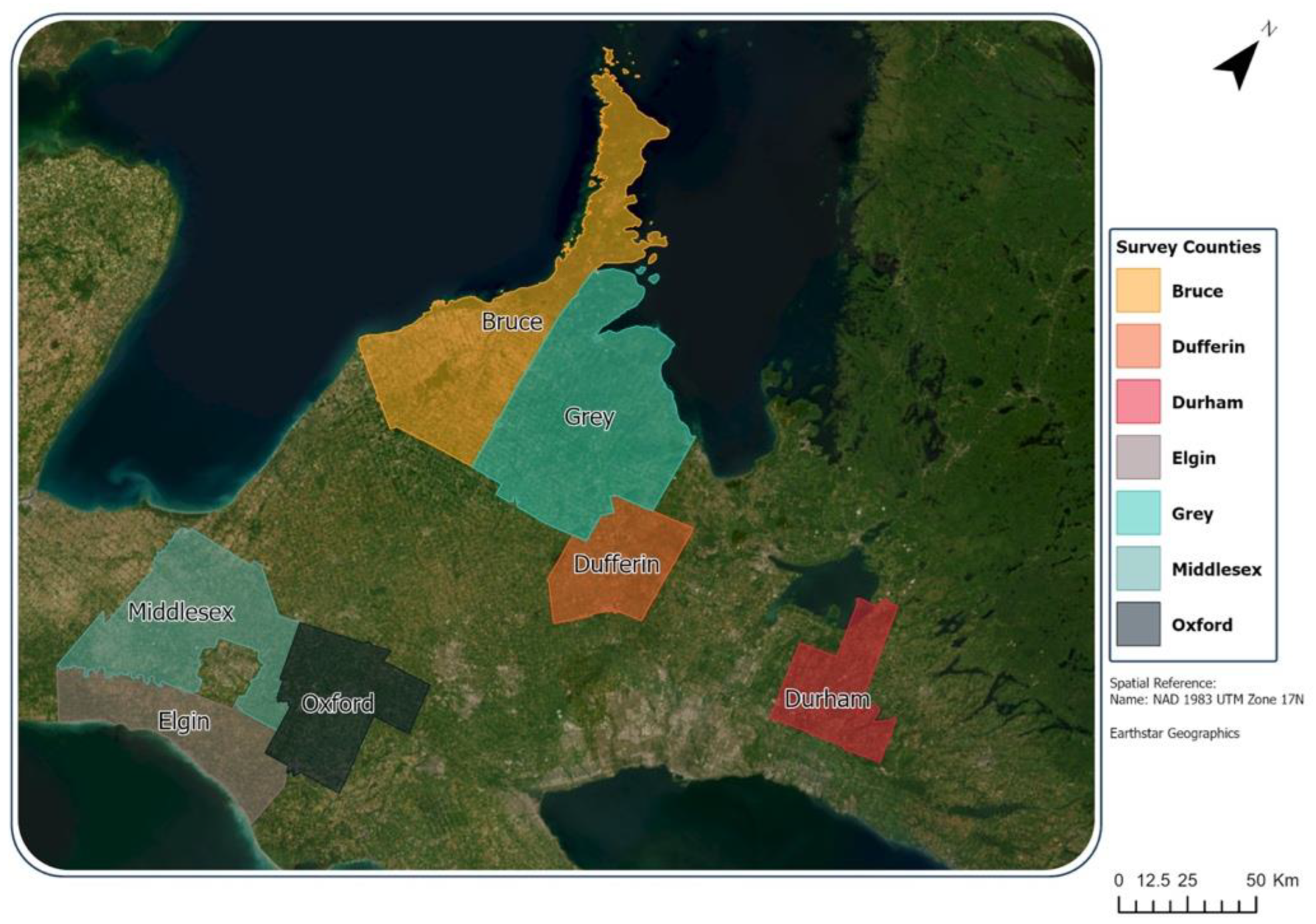

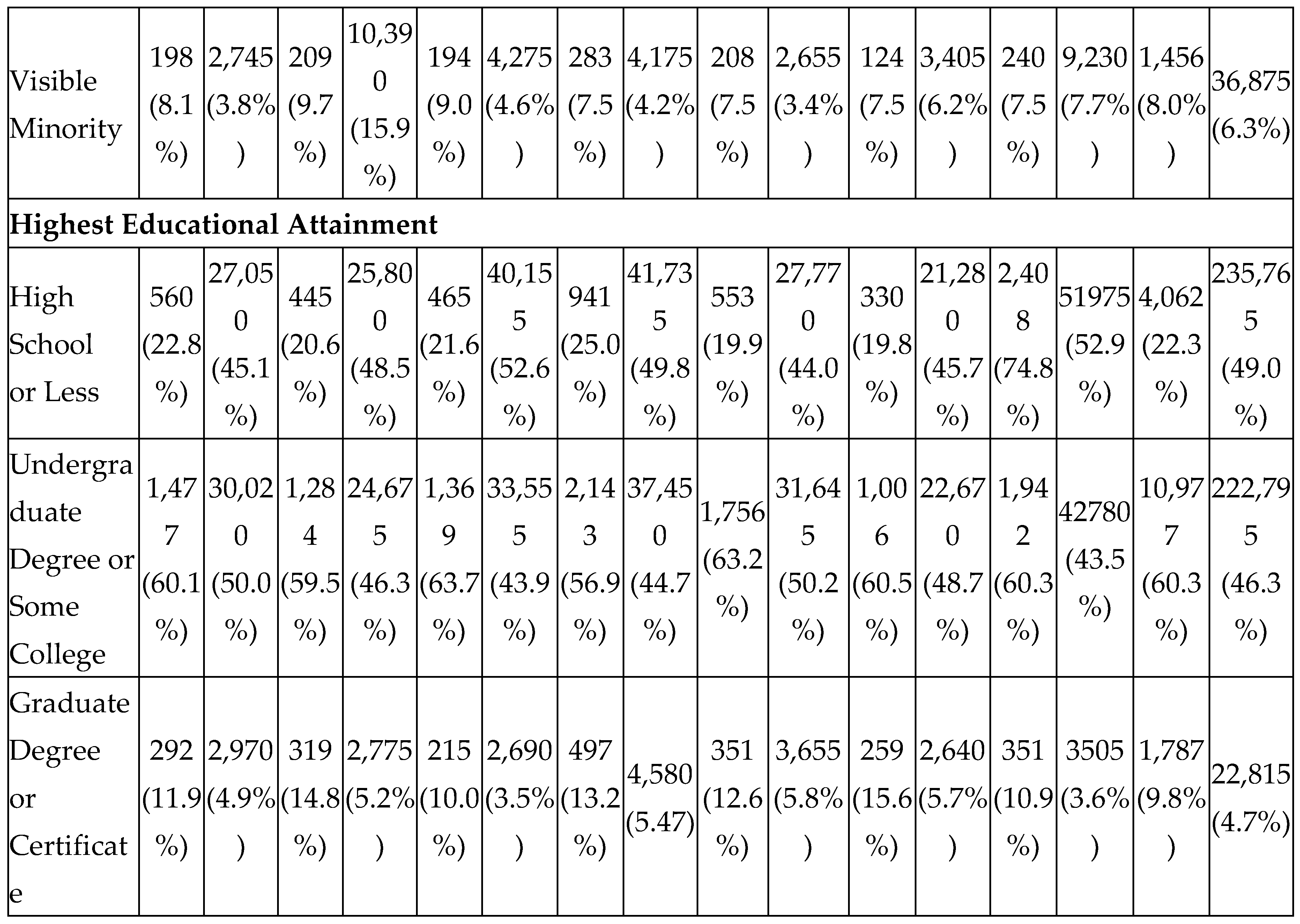

3.2. Survey Responses

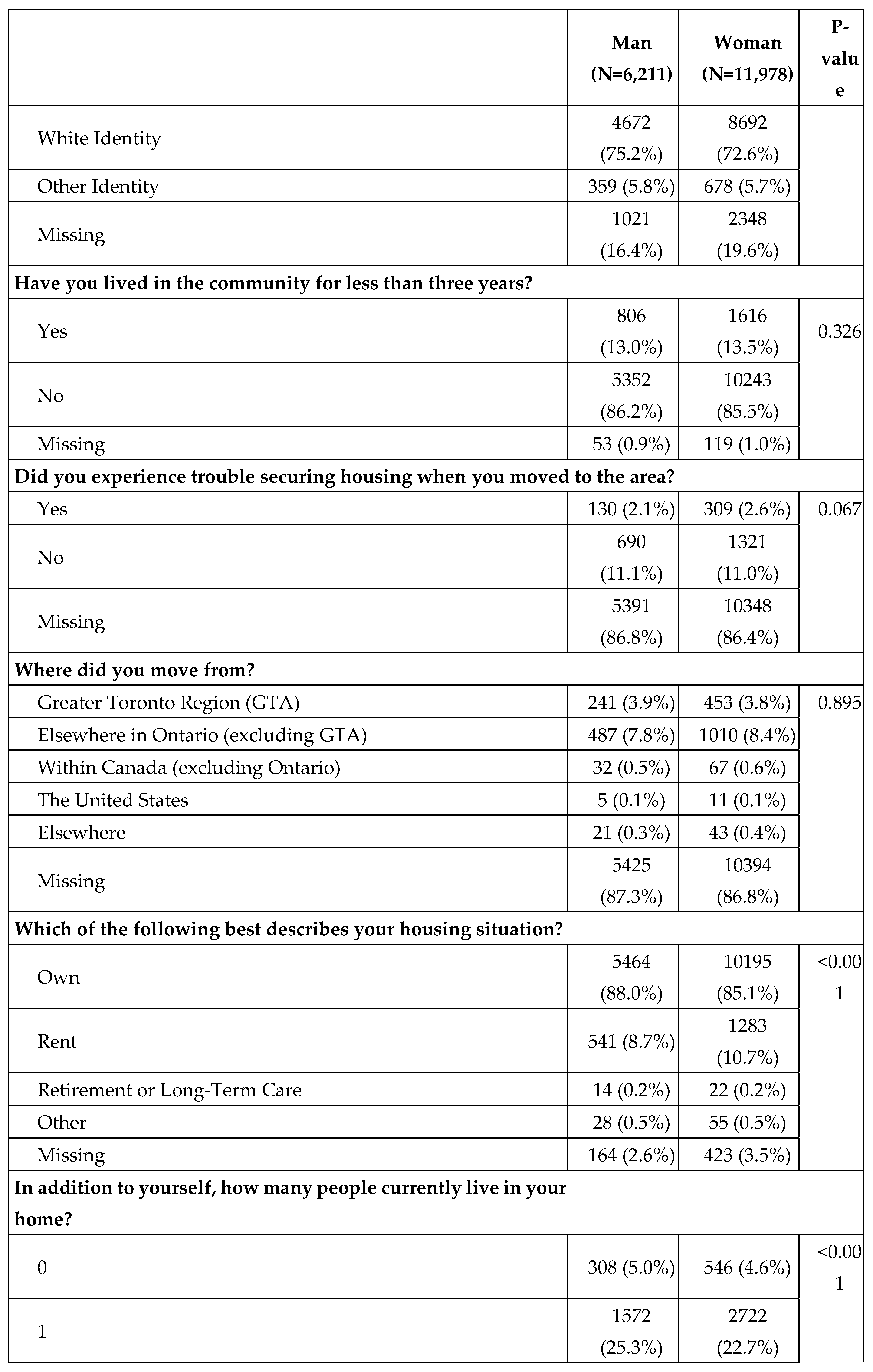

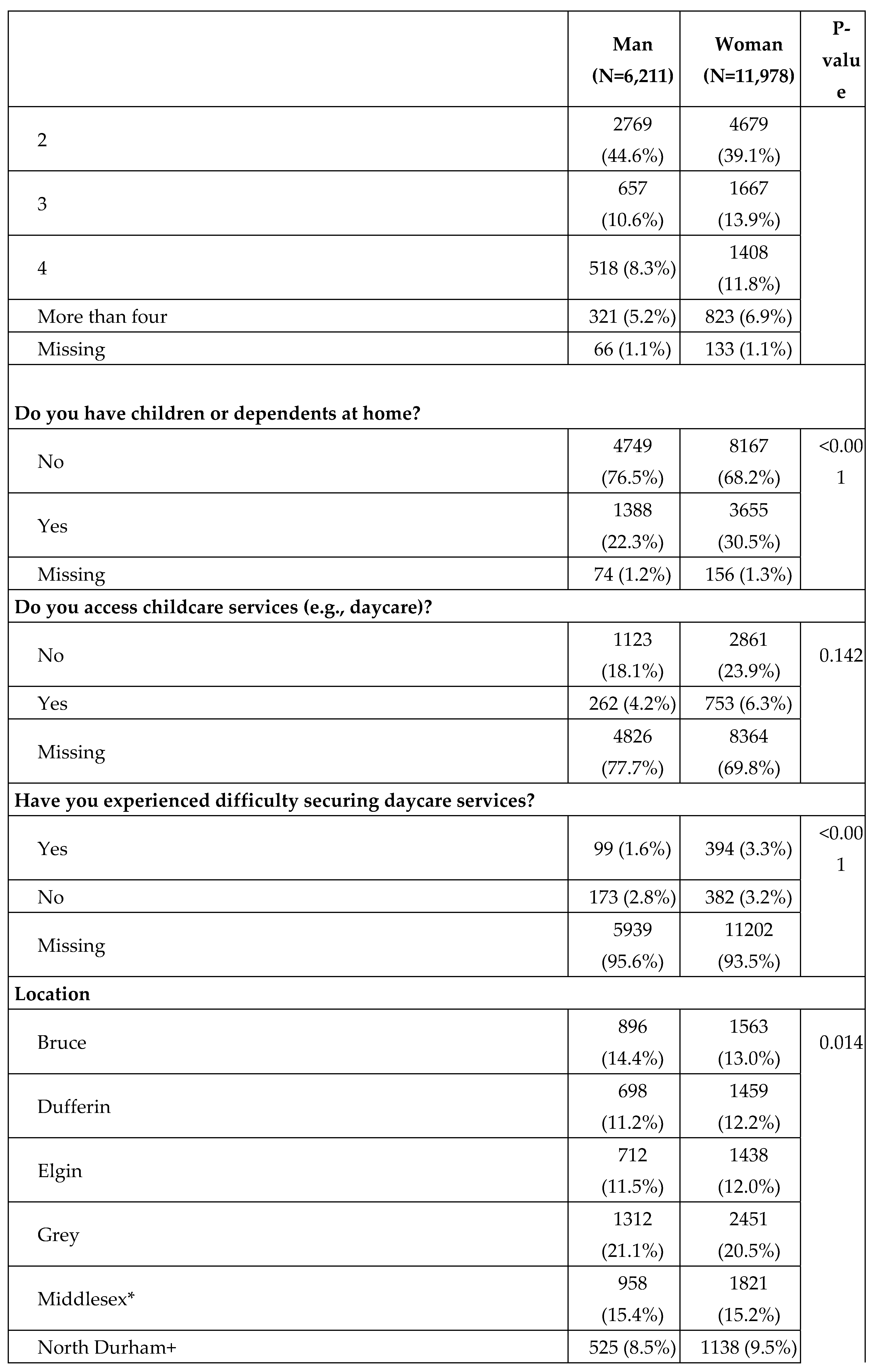

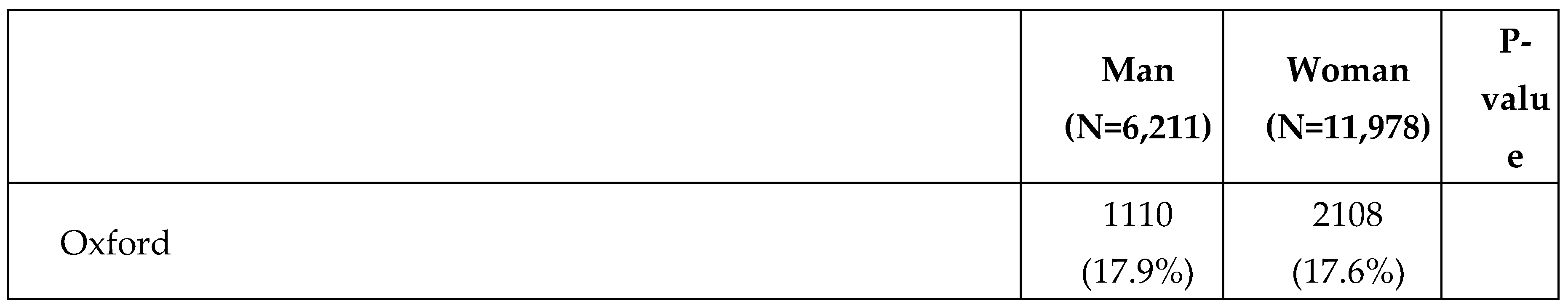

The survey questions were stratified by gender identity in

Table 2. The age distribution between men and women significantly differed. Men in the survey sample were older (aged 80 or more 10.4%) than women (aged 80 or more 6.0%), women had higher proportions of respondents aged 59 or less for each age grouping in comparison to men. Education significantly differed, with a larger proportion of women obtaining a bachelor’s degree (58.9%) in comparison to men (45.4%); men in this sample (13.7%) had a larger percentage of graduate degrees than women (12%). Men had less than or equal to a high school degree (23.1% vs women 22%). Men obtained a trades certificate (11.2%) more than women (3.3%). In terms of employment, more women reported being employed part time (men: 2.4%, women: 7.5%) while more men reported not being in the workforce (men: 51.6%, women: 42.7%). About a fifth (~20%) of ethnicity was missing for both men and women in the survey sample. The majority of those who did respond to the question were white (men: 75.2%, women: 72.6%).

Most survey respondents lived in their respective communities for three or more years (men:86.2%, women:85.5%). For those who did report moving, men and women did not report significant differences in securing housing or in where they were moving from. Most men and women in the survey sample owned their homes (men: 88%, women: 85.1%). Women rented (10.7%) more often than men (8.7%); women (3.5%) were less likely to respond to the question than men (2.6%). Women in the sample had more individuals living in their home– with higher percentages for three people (men: 10.6%, women: 13.9%), four people (men: 8.3%, women: 11.8%), and more than four people (men: 5.2%, women: 6.9%). Women in the survey sample reported having more children or dependents in the home (men: 22.3%, women: 30.5%). Women reported accessing daycare services more and reported increased difficulty during COVID-19.

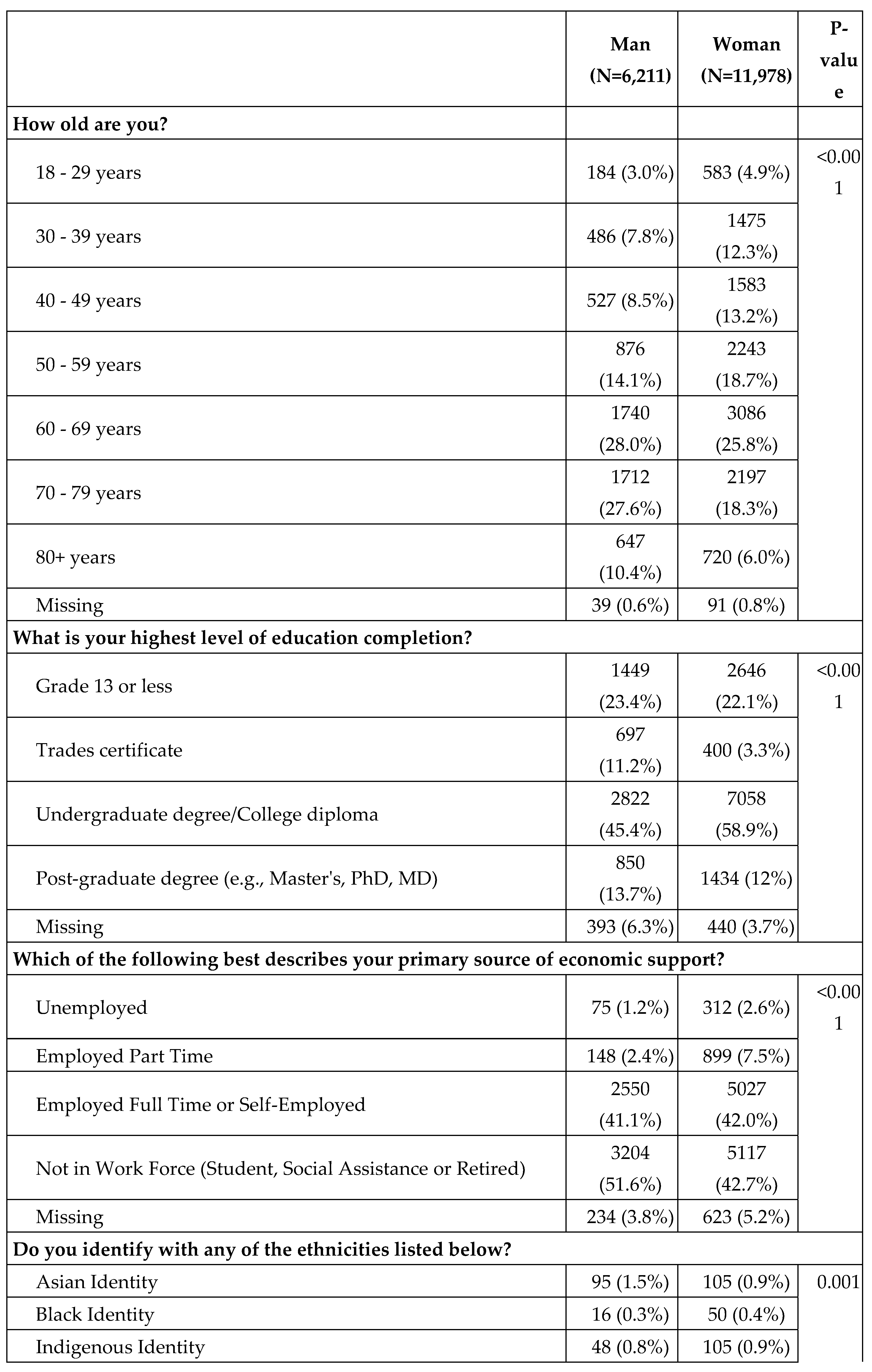

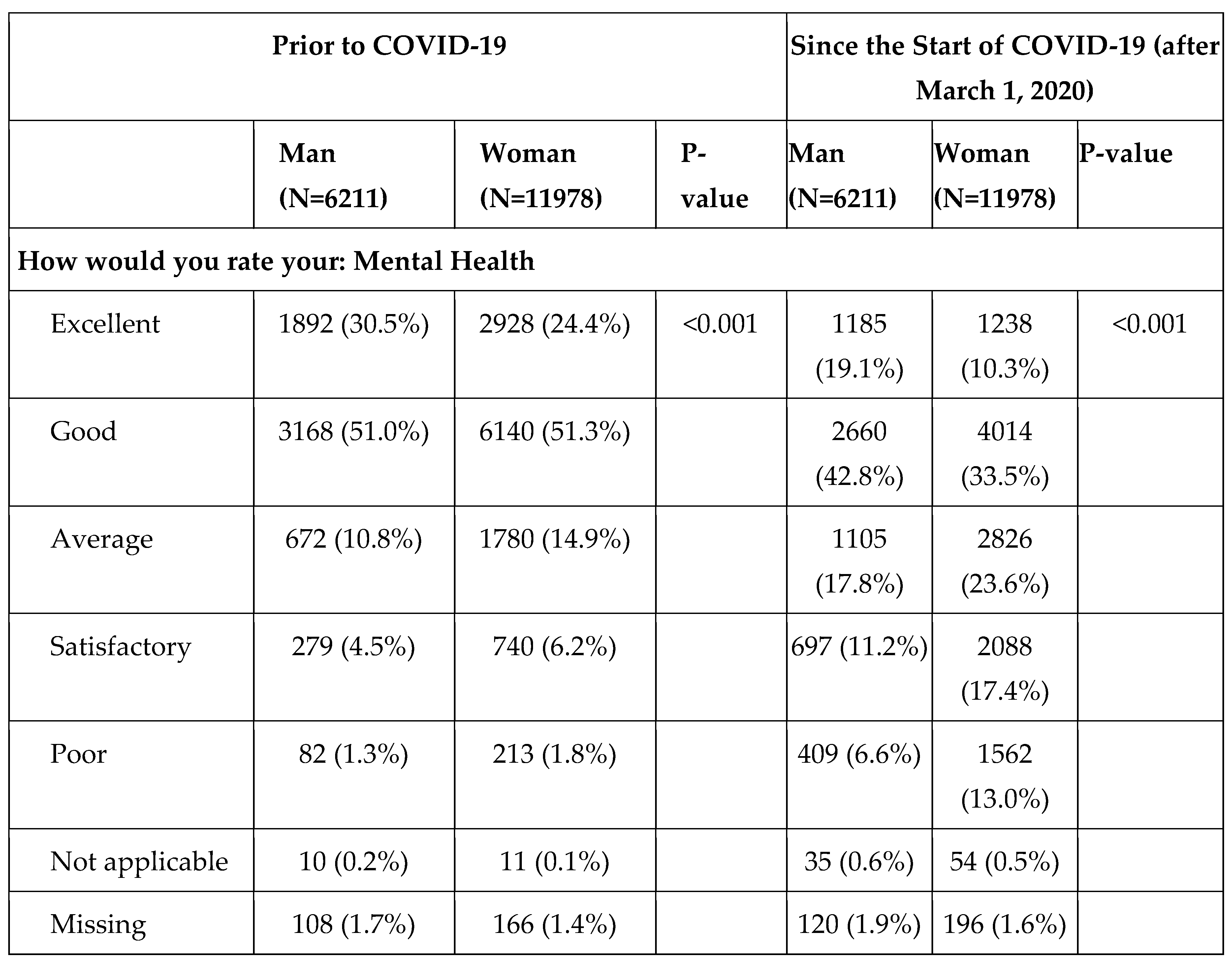

Self-reported mental health for all survey counties and regions were examined to establish if women reported differing mental health than men (

Table 3). Prior to COVID-19, a larger percentage of men self-reported ‘excellent’ in comparison to women (men: 30.5%, women: 24.4%). In contrast, women self-reported their mental health as ‘average’ more than men prior to COVID-19 (men: 10.8%, women 14.9%); neither had a high proportion of ‘poor’ self-reported mental health (men:1.3%, women: 1.8%). Since the start of COVID-19, fewer women reported ‘excellent’ mental health than before COVID-19 (men: 19.1%, women: 10.3%). In comparison to pre COVID-19 pandemic, more women and men reported ‘average’ mental health (men: 17.8%, women: 23.6%). The self-reported ‘poor’ mental health was greater in women and men since the start of COVID-19 (men: 6.6%, women: 13.2%).

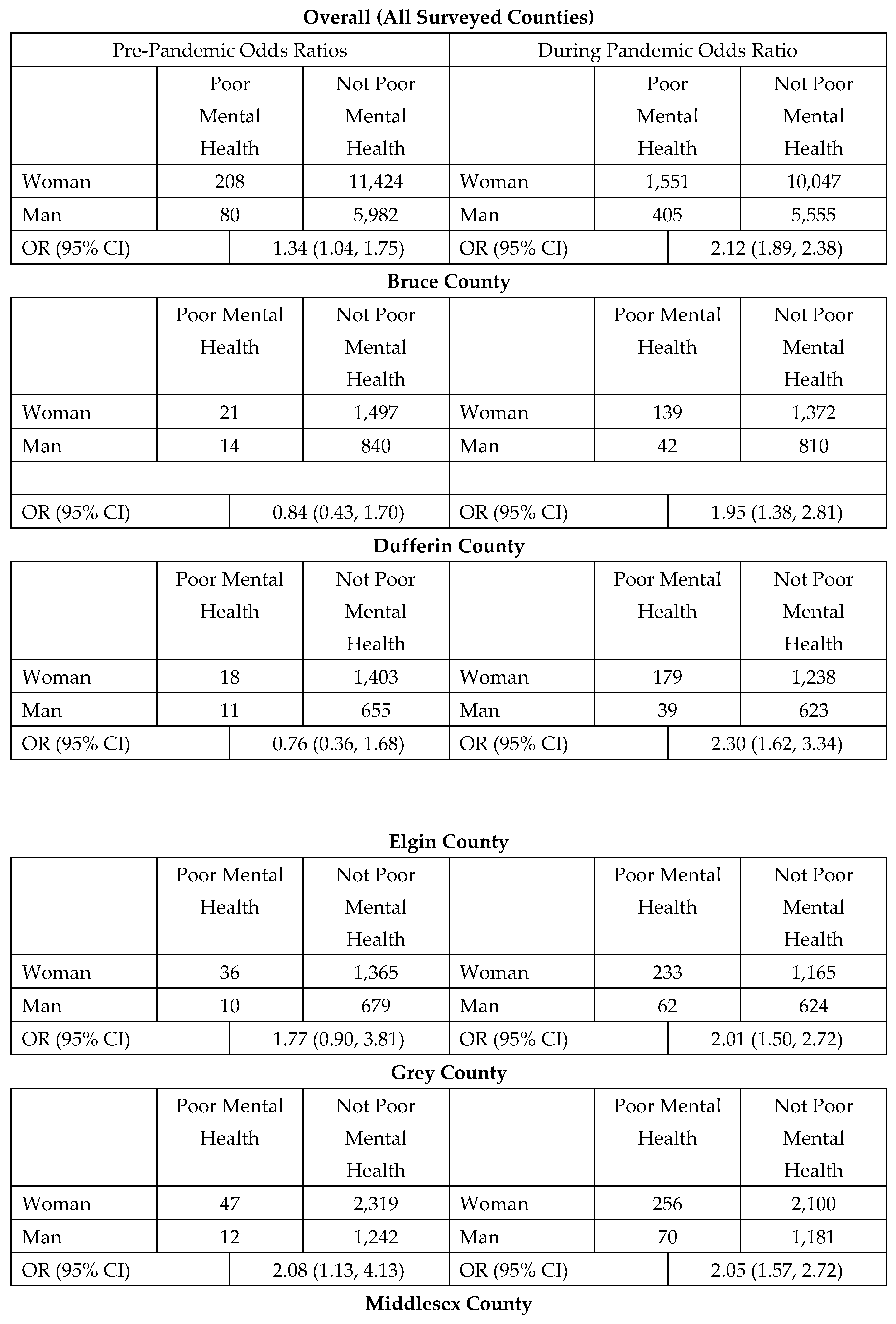

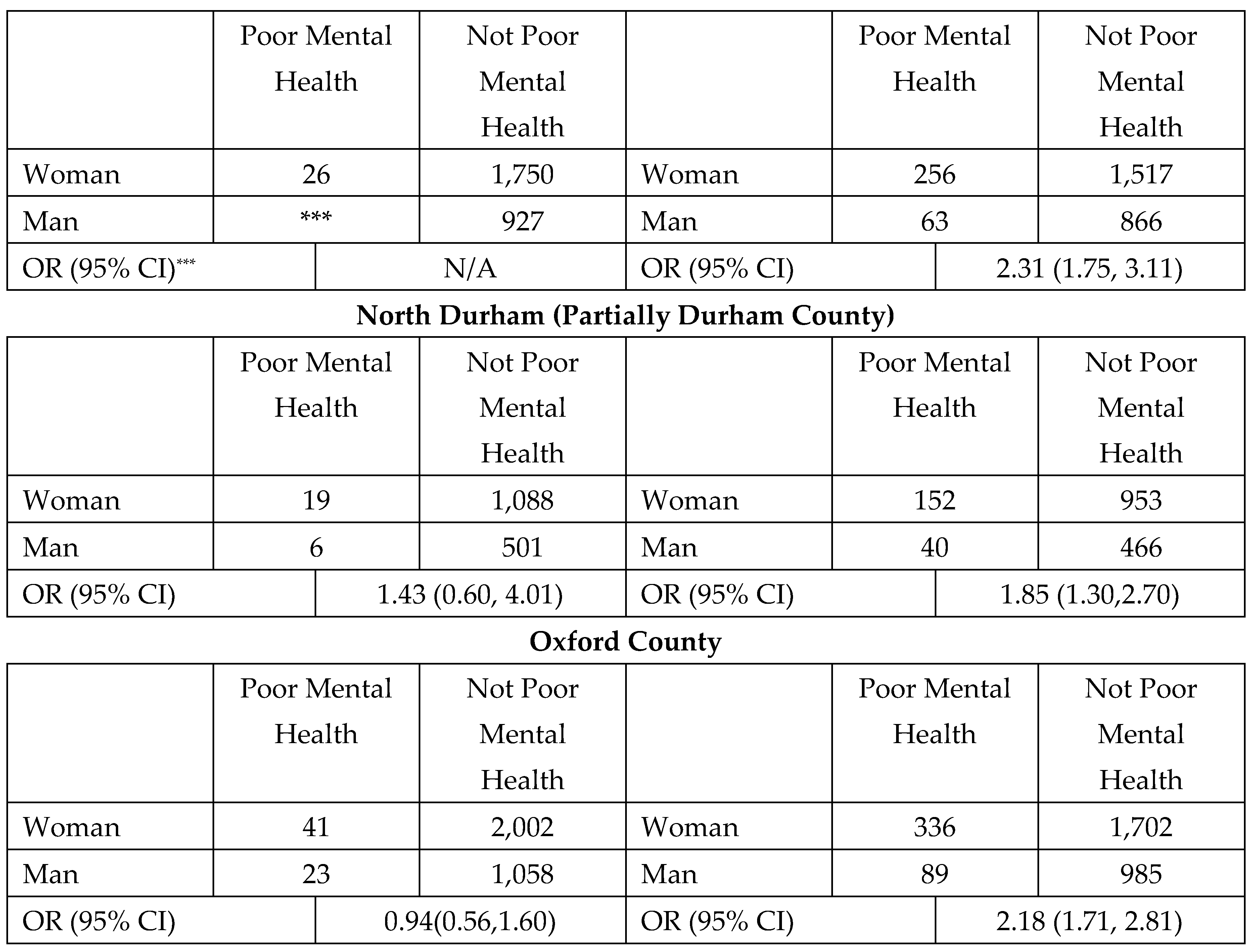

The unadjusted (

Table 4) odds ratios for poor mental health between men and women pre-pandemic were 1.34 with a 95% confidence interval between 1.04 and 1.75. The overall odds ratios for poor mental health between men and women post-pandemic were 2.12 with a 95% confidence interval between 1.89 and 2.38. The odds of a woman reporting ‘poor mental health’ pre-pandemic were 1.34 times that of men; the odds of a woman reporting ‘poor mental health’ during COVID-19 jumped to 2.12 times that of a man.

Adjusted odds ratios overall pre-pandemic were 1.09. At the 0.05 level, which was odds not significant and indicated self-reported poor mental health were the same for both men and women pre-pandemic. During-pandemic self-reported mental health was significant, with an odds ratio of 1.77; meaning the adjusted odds of a woman reporting poor mental health during COVID-19 were 1.77 times that of a man.

The segmented bar graph (

Figure 2) demonstrates women in the survey sample reporting less support and heightened worry during COVID-19 than men.

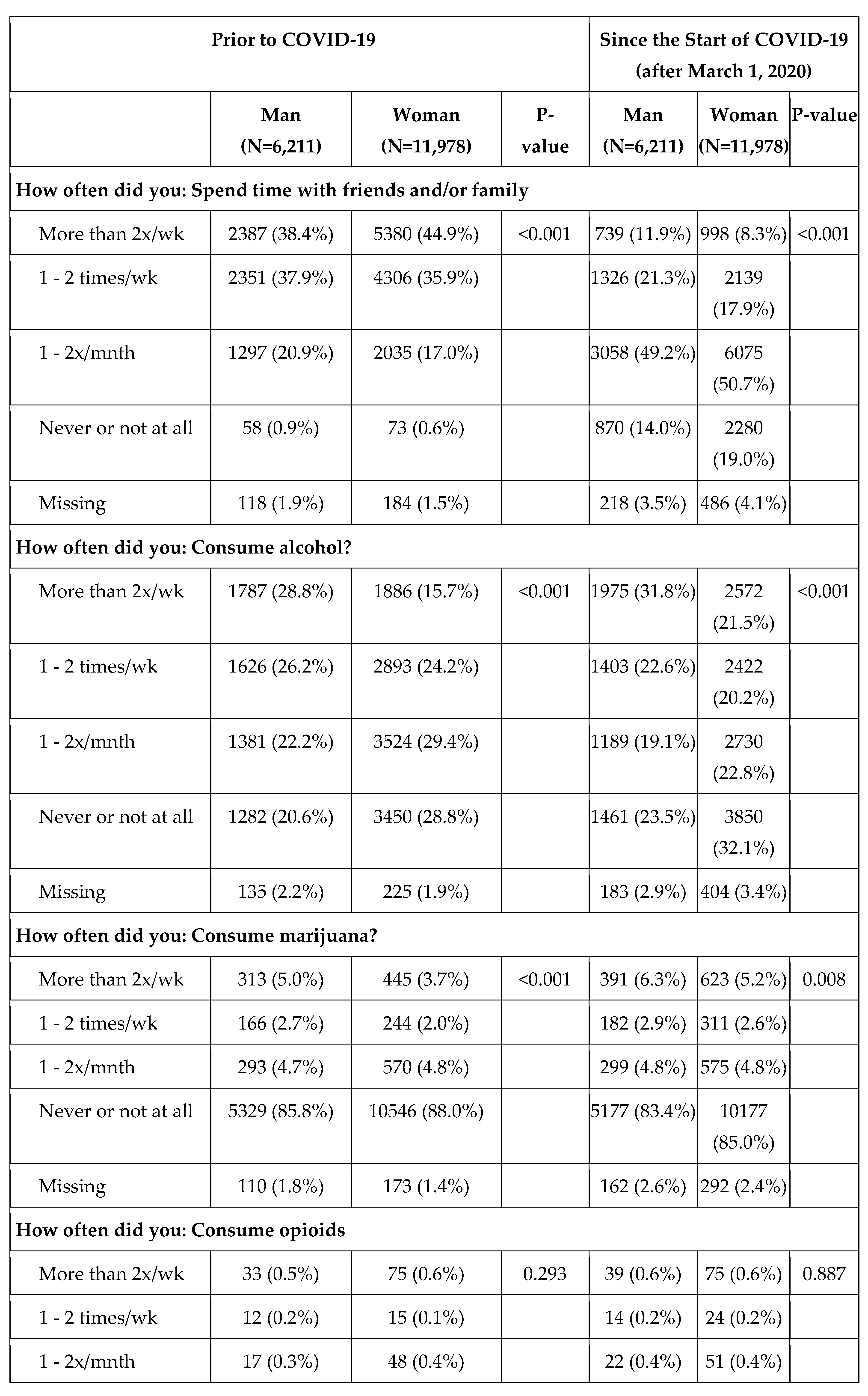

Health behaviors such as social interaction and substance consumption (Table 4) were evaluated to determine if they impacted the deterioration of mental health during COVID-19.

Table 4.

Health Behaviors.

Table 4.

Health Behaviors.

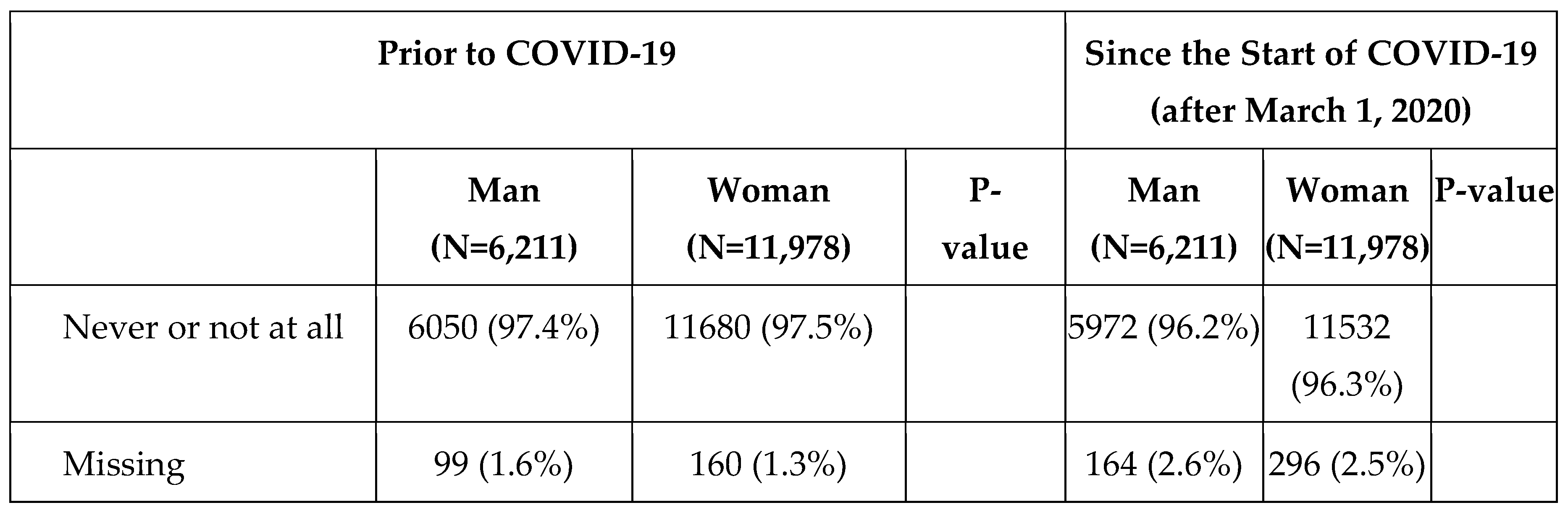

Figure 4.

Map of Self-Reported Mental Health by County with COVID-19 Case Overlay.

Figure 4.

Map of Self-Reported Mental Health by County with COVID-19 Case Overlay.

4. Discussion

This survey evaluated impacts of COVID-19 on rural southern Ontario communities. The survey sample was more women (65.9%) than men (34.1%), which may indicate a response bias as the census reports only slightly more females (50.6%) living in the sampled counties. The census is not an ideal comparator though, the survey measured gender whereas the census measured sex. The survey did not collect data on gender versus biological sex, therefore non-cisgender individuals are not captured, introducing opportunity for bias. Municipalities in North Durham County had the greatest gender disparity with 69.9% of respondents self-reporting woman and only 30.1% of respondents self-reporting man. Respondents identifying as women had a younger age distribution than men. Women reported having a higher percentage of bachelor’s degrees, while men in the sample had a higher percentage of graduate level degrees. Women in the sample appeared to fill part time roles more than full time, men in the sample had a higher percentage of full-time employment. These results align with research on gender equity in employment during COVID-19 – women were more unemployed. This work indicated advancement of women in the workplace during COVID-19 slowed as a result of household and childcare responsibilities in the home [

41].

Self-reported mental health for both men and women worsened from pre-COVID-19 to during COVID-19. Almost twice the percentage of women self-reported ‘poor’ mental health during COVID-19 in comparison to men. A Canada-wide survey had similar findings, males had less self-reported worsened mental health than females during COVID-19 [

42]. A scoping review found women had higher odds of reporting poor mental health conditions in comparison to men as did people living in rural areas in comparison to urban [

43]. When odds ratios were adjusted for age, education, primary source of economic support, and number of dependents, the odds of women reporting poor mental health during COVID-19 remained almost twice that of men. The odds of women reporting poor mental health during COVID-19 differed by county, indicating spatial variation even within rural areas. This aligns with similar findings in the United States where there was variation in mental health outcomes between rural and semi-rural communities [

44]. Rural areas each have unique social determinants of mental health outcomes [

45]. In the context of mental health intervention, some rural areas may have poorer access to mental health care – and alternative interventions may become more important as a result [

46]. The geographies of alternative mental health interventions (e.g. greenspaces) are not spatially homogenous and may differentially impact mental health [

47].

The survey evaluated factors which may have contributed to poorer mental health: stressors and health behaviors. Stressors (

Figure 2) were evaluated by asking respondents to gauge their level of worry pre and during COVID-19. The during pandemic responses to ‘I worried about my personal safety’ increased for both men and women respondents, with 21% of women responding ‘Yes’ and 22% responding ‘Sometimes’; 12% of men responded ‘Yes’ and 17% of men responded ‘Sometimes’. This may be a reflection of increased intimate partner violence that occurred during COVID-19 [

48]. In rural settings, intimate partner violence interventions such as in home support can be effective [

49] as well as facilitated group discussions [

50]; these were not possible during lockdowns. These interventions rely upon social support, which became another stressor for women in the sample during COVID-19. The responses to the survey question ‘I felt isolated physically or psychologically’ pre-pandemic was 4% ‘Yes’ for women and 4% for men. During the pandemic, 37% of women responded ‘Yes’ and 21% of men responded ‘Yes’; men may have felt isolated, but in this sample not to the same extent as women. Social supports have been linked to mental health, female university students who had greater social support had reduced anxiety, depression, and stress symptoms [

51]. Social supports may have a greater impact on female mental health symptoms in comparison to males [

52]; these findings show males may be more resilient to isolation [

51,

52]. Despite experiences of decreased perceived safety and increased isolation, reported mental health resource access did not differ for women during COVID-19, and increased only 1% from before to during in men; possibly indicating there are barriers to or stigma associated with accessing mental health support. Few sampled women and men reported seeing their family members never or not at all prior to COVID-19; during the pandemic, however, 19% of women and 14% of men reported no family contact.

Reported alcohol and marijuana use increased for men and women during COVID-19; indicating substance use as a coping mechanism [

53]. During COVID-19 21.5% of women reported consuming alcohol more than twice a week and 5.2% reported consuming marijuana more than twice a week. The increase in consumption of alcohol by women may be in response to increased stress [

54,

55]. While men reported increased use, the magnitude of increase for both substances were larger for women respondents.

The final figure shows counties with high cumulative COVID-19 case rates may have higher poor mental health adjusted odds. This possibility could be examined in future work – as it may be valuable to understand how mental health changed in response to the severity of COVID-19 in rural communities.

3.1. Limitations

This sample is not representative of the general populations living in the 7 counties surveyed. This sample was older, more educated), and had more visible minorities than the census. Non-Binary and other gender identities were not well captured by this survey; in the analysis process it was impossible to discern the difference between individuals who utilized other pronouns versus those who preferred not to answer. As a result of this, genders other than women and men were not included. This is a major limitation as gender exists on a spectrum and there are many more gender identities and expressions than man and woman [

56]. The survey did not collect biological sex data or data on sexuality, so it is unknown if the respondents in the home were living in heteronormative households; these are important considerations in understanding how social support may impact mental health outcomes [

57]. There is a need for additional research on gender identity and sexuality in the context of COVID-19. The sample could have been improved by expanding to include urban and suburban counties as comparators.

5. Conclusions

Women surveyed in this study reported increased isolation and greater concern for personal safety. Respondents who self-identified as women were slightly less educated, younger, and had more dependants than those who self-identified as men. Women reported poor mental health during COVID-19 more than men, and even with covariate adjustments. Odds ratios differed across the counties surveyed for this study, underscoring the importance of accounting for spatial variation within rural areas. Women and men reported increased substance use during COVID-19. There is a strong need for rural [

58] and gender specific interventions during pandemics or other distressing events. Women may experience increased burden of household work; it may become impossible to balance career, childcare, and household work when the demands for each increase. Women need social support to thrive, an increase in social isolation, will reduce women’s’ protections from poor mental health outcomes. It is imperative to take steps to ensure supports for women during future pandemics; gender-based health equity must be prioritized in hazard planning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D.; methodology, L.D., A.N., M.A.; analysis, A.N., M.A., L.D.; investigation, L.D.; data curation, L.D., L.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.N.; writing—review and editing, A.N., L.D., M.A., L.R.; visualization, A.N., L.D.; supervision, L.D., M.A.; project administration, L.D.; funding acquisition, L.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the Ontario Agri-Food Innovation Alliance.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The following work has been approved by the University of Guelph Research Ethics Board. (REB #20-05-020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to our survey participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- D. J. A. Dozois and Mental Health Research Canada, “Anxiety and depression in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey.,” Canadian Psychology / Psychologie canadienne, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 136–142, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Daly et al., “Associations between periods of COVID-19 quarantine and mental health in Canada,” Psychiatry Research, vol. 295, p. 113631, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Cannon, R. Ferreira, F. Buttell, and C. Anderson, “Sociodemographic Predictors of Depression in US Rural Communities During COVID-19: Implications for Improving Mental Healthcare Access to Increase Disaster Preparedness,” Disaster med. public health prep., vol. 17, p. e208, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xia et al., “Geographic concentration of SARS-CoV-2 cases by social determinants of health in metropolitan areas in Canada: a cross-sectional study,” CMAJ, vol. 194, no. 6, pp. E195–E204, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Deacon, S. Sarapura, W. Caldwell, S. Epp, M. Ivany, and J. Papineau, “COVID-19, mental health, and rurality: A pilot study,” The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe canadien, p. cag.12832, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- I. Chen and O. Bougie, “Women’s Issues in Pandemic Times: How COVID-19 Has Exacerbated Gender Inequities for Women in Canada and around the World,” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, vol. 42, no. 12, pp. 1458–1459, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Caldarulo et al., “COVID-19 and gender inequity in science: Consistent harm over time,” PLoS ONE, vol. 17, no. 7, p. e0271089, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. N. Laster Pirtle and T. Wright, “Structural Gendered Racism Revealed in Pandemic Times: Intersectional Approaches to Understanding Race and Gender Health Inequities in COVID-19,” Gender & Society, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 168–179, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mental Health Commission of Canada, “The Impact of COVID-19 on Rural and Remote Mental Health and Substance Use,” Health Canada, Ottowa, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/The-Impact-of-COVID-19-on-Rural-and-Remote-Mental-Health-and-Substance-Use.pdf.pdf.

- J. S. Moin et al., “Utilization of physician mental health services by birthing parents with young children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based, repeated cross-sectional study,” cmajo, vol. 11, no. 6, pp. E1093–E1101, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Moin et al., “Sex differences among children, adolescents and young adults for mental health service use within inpatient and outpatient settings, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based study in Ontario, Canada,” BMJ Open, vol. 13, no. 11, p. e073616, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Moyser, “Gender differences in mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Statistics Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, Jul. 2020. Accessed: May 06, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00047-eng.pdf?st=fZ4s0vGO.

- J. T. Brophy, M. M. Keith, M. Hurley, and J. E. McArthur, “Sacrificed: Ontario Healthcare Workers in the Time of COVID-19,” New Solut, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 267–281, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Mandal and E. Purkey, “Psychological Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Rural Physicians in Ontario: A Qualitative Study,” Healthcare, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 455, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Nadon, L. T. De Beer, and A. J. S. Morin, “Should Burnout Be Conceptualized as a Mental Disorder?,” Behavioral Sciences, vol. 12, no. 3, p. 82, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Myran et al., “Sociodemographic changes in emergency department visits due to alcohol during COVID-19,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, vol. 226, p. 108877, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Li, S. Sood, and C. Johnston, “Impact of COVID-19 on small businesses in Canada, fourth quarter of 2021,” Statistics Canada, Jan. 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/45-28-0001/2021001/article/00043-eng.pdf?st=Sffscto1.

- V. A. Karatayev, M. Anand, and C. T. Bauch, “Local lockdowns outperform global lockdown on the far side of the COVID-19 epidemic curve,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., vol. 117, no. 39, pp. 24575–24580, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. F. Cuadros, A. J. Branscum, Z. Mukandavire, F. D. Miller, and N. MacKinnon, “Dynamics of the COVID-19 epidemic in urban and rural areas in the United States,” Annals of Epidemiology, vol. 59, pp. 16–20, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Glenister, K. Ervin, and T. Podubinski, “Detrimental Health Behaviour Changes among Females Living in Rural Areas during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” IJERPH, vol. 18, no. 2, p. 722, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Kerbage et al., “Challenges facing COVID-19 in rural areas: An experience from Lebanon,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 53, p. 102013, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Michaelsen, E. Nombro, H. Djiofack, O. Ferlatte, B. Vissandjee, and C. Zarowsky, “Looking at COVID-19 effects on intimate partner and sexual violence organizations in Canada through a feminist political economy lens: a qualitative study,” Can J Public Health, vol. 113, no. 6, pp. 867–877, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Frize et al., “The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on gender-related work from home in STEM fields—Report of the WiMPBME Task Group,” Gender Work Organ, vol. 28, no. S2, pp. 378–396, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Shamseer et al., “Will COVID-19 result in a giant step backwards for women in academic science?,” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, vol. 134, pp. 160–166, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Smith, “From ‘nobody’s clapping for us’ to ‘bad moms’: COVID-19 and the circle of childcare in Canada,” Gender Work Organ, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 353–367, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. L. Bradley, A. M. DiPasquale, K. Dillabough, and P. S. Schneider, “Health care practitioners’ responsibility to address intimate partner violence related to the COVID-19 pandemic,” CMAJ, vol. 192, no. 22, pp. E609–E610, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Gadermann et al., “Examining the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on family mental health in Canada: findings from a national cross-sectional study,” BMJ Open, vol. 11, no. 1, p. e042871, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Montesanti, W. Ghidei, P. Silverstone, L. Wells, S. Squires, and A. Bailey, “Examining organization and provider challenges with the adoption of virtual domestic violence and sexual assault interventions in Alberta, Canada, during the COVID-19 pandemic,” J Health Serv Res Policy, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 169–179, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Xue, J. Chen, C. Chen, R. Hu, and T. Zhu, “The Hidden Pandemic of Family Violence During COVID-19: Unsupervised Learning of Tweets,” J Med Internet Res, vol. 22, no. 11, p. e24361, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Michaelsen, H. Djiofack, E. Nombro, O. Ferlatte, B. Vissandjée, and C. Zarowsky, “Service provider perspectives on how COVID-19 and pandemic restrictions have affected intimate partner and sexual violence survivors in Canada: a qualitative study,” BMC Women’s Health, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 111, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Shillington, L. M. Vanderloo, S. M. Burke, V. Ng, P. Tucker, and J. D. Irwin, “Ontario adults’ health behaviors, mental health, and overall well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic,” BMC Public Health, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 1679, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Scharf and K. Oinonen, “Ontario’s response to COVID-19 shows that mental health providers must be integrated into provincial public health insurance systems,” Can J Public Health, vol. 111, no. 4, pp. 473–476, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- STAT Can, “Canadian Census Data,” University of Toronto CHASS Data Center, 2016.

- K. Chastko, P. Charbonneau, and L. Martel, “Population growth in Canada’s rural areas, 2016 to 2021,” Statistics Canada. [Online]. Available: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/98-200-x/2021002/98-200-x2021002-eng.cfm.

- NatCen Social Research, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health University College London, and National Health Service (NHS), “Health Surveyfor England 2018.” 2018. Accessed: May 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://doc.ukdataservice.ac.uk/doc/8649/mrdoc/pdf/8649_hse_2018_user_guide.pdf.

- Ontario Ministry of Health, “Management of Cases and Contacts of COVID-19 in Ontario,” 2022.

- Posit team, “RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R,” Posit Software, PBC. [Online]. Available: http://www.posit.co/.

- Statistics Canada, “2021 Census - Boundary files.” Statistics Canada, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/geo/sip-pis/boundary-limites/index2021-eng.cfm?year=21.

- Statistics Canada, “Dictionary, Census of Population, 2021: Map projection,” Statistics Canada. [Online]. Available: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/ref/dict/az/Definition-eng.cfm?ID=geo031.

- J. Josse and F. Husson, “missMDA: A Package for Handling Missing Values in Multivariate Data Analysis,” J. Stat. Soft., vol. 70, no. 1, 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Vandecasteele, K. Ivanova, I. Sieben, and T. Reeskens, “Changing attitudes about the impact of women’s employment on families: The COVID-19 pandemic effect,” Gender Work & Organization, vol. 29, no. 6, pp. 2012–2033, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Michaud et al., “Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on self-reported health status and noise annoyance in rural and non-rural Canada,” Sci Rep, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 15945, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, M. P. Kala, and T. H. Jafar, “Factors associated with psychological distress during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on the predominantly general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” PLoS ONE, vol. 15, no. 12, p. e0244630, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Breslau, G. N. Marshall, H. A. Pincus, and R. A. Brown, “Are mental disorders more common in urban than rural areas of the United States?,” Journal of Psychiatric Research, vol. 56, pp. 50–55, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Cortina and S. Hardin, “The Geography of Mental Health, Urbanicity, and Affluence,” IJERPH, vol. 20, no. 8, p. 5440, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Ryan, M. M. Sugg, J. D. Runkle, and J. L. Matthews, “Spatial Analysis of Greenspace and Mental Health in North Carolina: Consideration of Rural and Urban Communities,” Family & Community Health, vol. 46, no. 3, pp. 181–191, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- O. Gruebner et al., “A spatial epidemiological analysis of self-rated mental health in the slums of Dhaka,” Int J Health Geogr, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 36, 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Hoffman, C. Ryus, G. Tiyyagura, and K. Jubanyik, “Intimate partner violence screening during COVID-19,” PLoS ONE, vol. 18, no. 4, p. e0284194, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Bacchus et al., “‘Opening the door’: A qualitative interpretive study of women’s experiences of being asked about intimate partner violence and receiving an intervention during perinatal home visits in rural and urban settings in the USA,” Journal of Research in Nursing, vol. 21, no. 5–6, pp. 345–364, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Gupta et al., “Gender norms and economic empowerment intervention to reduce intimate partner violence against women in rural Côte d’Ivoire: a randomized controlled pilot study,” BMC Int Health Hum Rights, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 46, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. Barros and A. Sacau-Fontenla, “New Insights on the Mediating Role of Emotional Intelligence and Social Support on University Students’ Mental Health during COVID-19 Pandemic: Gender Matters,” IJERPH, vol. 18, no. 24, p. 12935, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Shangguan, L. Zhang, Y. Wang, W. Wang, M. Shan, and F. Liu, “Expressive Flexibility and Mental Health: The Mediating Role of Social Support and Gender Differences,” IJERPH, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 456, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chan, Xue, Carlson, Gray, Bailey, and Vines, “Impact of COVID-19 on lifestyle and mental wellbeing in a drought-affected rural Australian population,” RRH, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Neill et al., “Alcohol use in Australia during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic: Initial results from the COLLATE project,” Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci., vol. 74, no. 10, pp. 542–549, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Emery, S. T. Johnson, M. Simone, K. A. Loth, J. M. Berge, and D. Neumark-Sztainer, “Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on stress, mood, and substance use among young adults in the greater Minneapolis-St. Paul area: Findings from project EAT,” Social Science & Medicine, vol. 276, p. 113826, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. P. Rahilly, Trans-affirmative parenting: raising kids across the gender spectrum. New York: New York University Press, 2020.

- D. M. Huisman, Social power and communicating social support: how stigma and marginalization affect our ability to help. New York ; London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2023.

- Nott and Hawthorn, “A networked approach to addressing COVID-19 in rural and remote Australia,” RRH, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).