1. Introduction

As the global population grows, ensuring a stable supply of crops has become a critical challenge for the international community [

1,

2]. Pests and diseases are major contributors to yield losses in essential crops such as rice, wheat, and potatoes. Early detection of these threats is vital, as it allows for timely interventions that can mitigate damage and prevent significant losses.

With the advancement of deep neural networks [

2,

3,

4], the performance of object detection models has significantly improved. However, this progress has come at the cost of increased model complexity and parameter count. In contrast, developing efficient detection models for specific application scenarios, such as agriculture, remains a challenging task. On one hand, existing research primarily focuses on designing complex models that achieve high detection accuracy across a variety of scenes. On the other hand, hardware resources in specialized application areas, such as agriculture, are often limited. Therefore, it is crucial to focus on reducing computational overhead to accelerate model inference while maintaining detection accuracy.

In recent years, numerous methods have been proposed to balance detection accuracy and efficiency, including image enhancement [

5], neural architecture search [

6], knowledge distillation [

7], and lightweight model design [

8]. Among these, lightweight model design has become the leading approach, with a focus on reducing the complexity of the backbone network [

9]. Popular models such as MobileNet [

10] and ShuffleNet [

11] leverage depth-separable and group convolutions for efficient image feature extraction. However, detection accuracy still requires further improvement, as current methods often omit the heavy detection heads commonly used in state-of-the-art detectors. To address this, additional approaches, such as network pruning and structural redesign, have been proposed and shown to speed up inference. Despite their effectiveness, these methods often lead to significant drops in detection performance when computational resources are drastically reduced. Furthermore, these techniques are primarily optimized for low-resolution input images and thus struggle to effectively balance both detection accuracy and efficiency. Meanwhile, diffusion models [

12,

13] have recently emerged as a powerful alternative for high-quality generative modeling, demonstrating strong capabilities in object detection and semantic understanding by leveraging iterative denoising processes. These models [

14,

15] have been successfully applied in pose-guided image synthesis and virtual dressing applications , showcasing their potential in enhancing feature extraction and improving robustness in detection tasks.

Sparse convolution [

16,

17,

18] selectively performs convolution operations only on non-zero elements in the input feature map, significantly reducing computational complexity and improving detection efficiency. This makes it a promising alternative for enhancing computational efficiency in object detection tasks. Yan et al. [

16] demonstrated substantial improvements in 3D object detection by integrating sparse convolution with an efficient embedding strategy. Similarly, Chen et al. [

17] optimized sparse convolution by introducing a focused sparse convolution operation, making it more effective for processing large-scale 3D point cloud data. Furthermore, Hong et al. [

18] proposed a dynamic sparse detection framework that selectively focuses on important foreground regions during both training and inference, thereby reducing computational overhead through a dynamic sparse sampling strategy.

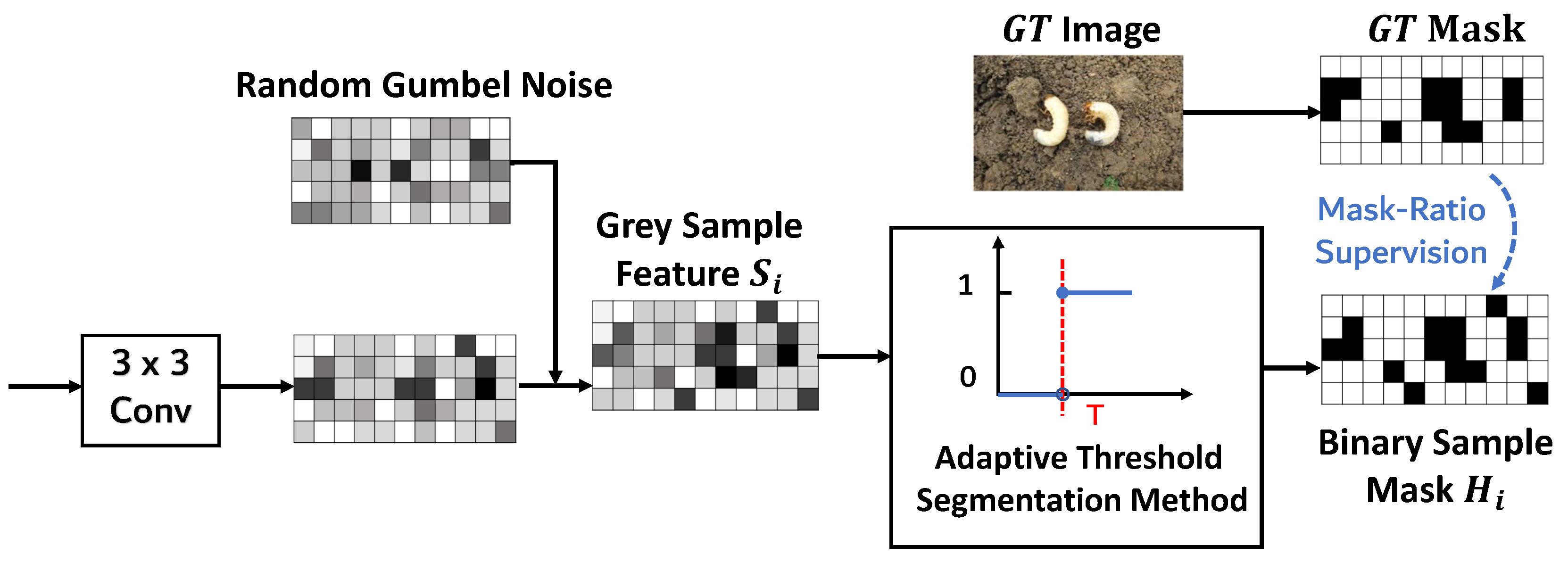

Recently, Sparse Convolutional Neural Networks (SCNNs) have gained attention as an efficient approach for accelerating inference by generating pixel-level sample masks [

19]. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the input feature map is first filtered using sample masks to identify valid pixel points, which are then extracted to form sparse feature vectors. These sparse features undergo convolution with a kernel, ensuring that computations are only performed at valid positions. The resulting sparse convolved features are subsequently mapped back to the 2D space of the original feature map, forming a computationally efficient representation. Efforts have been made to leverage sparse convolution for optimizing detection heads. Song et al. [

20] proposed a method that reduces computational costs by integrating spatial gates at different feature scales within an FPN (Feature Pyramid Network). Similarly, QueryDet [

21] was designed for high-resolution images, utilizing P2 features of FPN to enhance small-object detection accuracy. Furthermore, a cascaded sparse query structure was introduced using focus loss [

22] to accelerate training. However, existing methods often rely on fixed mask ratios, which fail to effectively capture global context information, leading to suboptimal performance when handling varying foreground-background feature distributions. As a result, their effectiveness is limited in diverse application scenarios where feature distributions differ significantly.

In order to solve this problem, we propose a plug-and-play adaptive sparse convolution network with background-feature fusion (ASCBF). Specifically, the generated sample masks are supervised by estimating the optimal mask ratios using GT labels, so that they can be dynamically and adaptively adjusted to the optimal mask ratios, thus achieving adequate coverage of features in different foreground regions. In addition, relying only on the foreground features extracted by sparse convolution for detection while ignoring the background features that contain other useful information can lead to degradation of detection performance. In this regard, we design a lightweight feature fusion method to guide the fusion of sparse foreground features with background features through difference mapping. While retaining the high sensitivity of the sparse foreground features to the target region, the global context information of the background features is fully utilised, thus significantly improving the overall performance of the model. The contribution of our work lies in three-fold:

We propose an adaptive multi-layer mask-ratio strategy based on sparse convolution to focus on the most informative features and reduce computational overhead.

We introduce an adaptive threshold segmentation method based on Otsu to address the limitations of fixed threshold segmentation in handling feature distribution differences of different pests and complex environmental scenes.

We propose a lightweight difference-guided feature fusion method to effectively integrate foreground and background features, which not only improves detection performance but also achieves a lightweight design of the model.

2. Methods

In this section, we will describe in detail the datasets used in the work of the paper in

Section 2.1, furthermore, adaptive sparse convolution network with background-feature fusion (ASCBF) will be introduced in detail. The network model is shown in

Figure 2. In a given base detector (RetinaNet is used as an example in the paper), an adaptive multilayer mask-ratio strategy(AMMS) is adopted for the different scales of the FPN features, and a binary sample mask generated under the supervision of the GT labels is added to the FPN features of each layer, and this sample mask is used to corresponding pixel-level features are filtered to form sparse foreground features, and the specific process will be described in detail in

Section 2.2. In an effort to more accurately distinguish foreground features from background features and thus achieve better foreground coverage with sparse convolution, we propose the adaptive threshold segmentation method (ATSM), and the specific process is described in detail in

Section 2.3. For the reason that the background features containing context and background information, and avoid the problem of insufficient detection accuracy and model generalisation ability due to the loss of background information, we construct a difference-guided feature fusion (DGFF) method for integration of foreground and background features, and generates corresponding spatial weights and channel weights to complete the weighted fusion of foreground and background features, which further improves the detection accuracy of the model, and the specific process is described in

Section 2.4. Finally, we will present our experimental platform in

Section 2.5 and evaluation metrics in

Section 2.6, respectively.

2.1. IP102 Dataset

To validate the effectiveness of the ASCBF module, the paper uses a large-scale benchmark dataset for crop pest identification, IP102. IP102 [

23] dataset is a crop pest dataset for the object classification and detection task, containing more than 75,000 images of eight crops, rice, maize, wheat, sugar beets, alfalfa, grapes, citrus, and mango, with 102 types of pests images, which show a natural long-tailed distribution. Considering the difficulty of marking the bounding box, IP102 randomly selects some images from each category to form a data subset for the object detection task, including a total of 18,983 images that can be used for the object detection task of crop pests, as shown in

Table 1, and IP102 divides these images into the training set and the test set according to the ratio of 4:1.

In addition, considering that pests at different life stages have different levels of damage to agricultural products [

24], and in order to increase the relevance of the crop pest object detection task, the IP102 object detection task dataset retains images of pests at different life stages, including egg, larvae, pupae, and adult during the data collection and annotation period , as shown in

Figure 3.

2.2. Adaptive Multilayer Mask-Ratio Strategy

Conventional sparse convolution performs convolution operations only on the non-zero elements of the input feature map, thus reducing the computational effort significantly. Based on this idea, we propose an improved method to perform sparse convolution on an image by generating pixel-level binary sample masks to efficiently extract foreground features. Specifically, for a given feature map

of the

ith layer of the FPN , ASCBF employs a shared convolution kernel

, where

B ,

C ,

H ,

W denote the batch size, the number of channels, the height and the width, respectively. Firstly, a grey feature map is generated based on the convolution of

to the feature

, which is subsequently further transformed into a binary mask matrix by using the Gumbel-Softmax technique [

25], as shown in Equation (

1).

In Equation (

1),

denote two random gumbel noises,

is the sigmoid function,

is the corresponding temperature parameter in Gumbel-Softmax, and

T is the threshold discussed in detail in

Section 2.3. According to Equation (

1), sparse convolution is performed only on regions with mask value of 1 during the model training and inference phases, which significantly reduces the overall computational cost. However, in the absence of any additional constraints, sparse detectors often tend to generate masks with large mask ratios in order to obtain higher accuracy, e.g., most of the existing studies use fixed mask-ratios (usually manually set to be greater than

), which increases the overall computational cost to a certain extent, and is unable to flexibly adapt to the feature distributions of different scenarios, limiting the model performance optimisation space.

To solve this problem, the sparsity in the paper is controlled by the optimal mask-ratio of GT labels. As shown in

Figure 4, the adaptive multilayer masking strategy first estimates the optimal mask-ratio based on GT labels. By using the label assignment technique, the GT detection result

can be obtained for the features of the

ith layer of the FPN , where

denote the height and

denote the width of the features of

ith layer, respectively, and then the optimal mask-ratio of FPN layer is shown in Equation (

2).

where

and

denote the number of pixels belonging to the foreground instance and the total number of pixels, respectively. In order to guide the network to generate a mask that is close to the optimal mask-ratio of the GT labels, a loss function as shown in Equation (

3) is used for constraints.

where

denotes the mask-ratio of the binary sample mask. By minimizing

, the network is able to generate a binary sample mask that is closer to the optimal mask ratio of the GT tag, thus extracting better sparse foreground features and achieving better coverage of the foreground region.

2.3. Adaptive Threshold Segmentation Method

In the crop pest object detection task, there are significant limitations in directly using a fixed threshold (e.g., 0.5) for grey-scale feature map segmentation [

26]. Firstly, fixed thresholds lack dynamic adaptability and are difficult to deal with feature distribution differences of different target pests and complex environmental scenes, which may lead to the loss of object features or the introduction of background interference. Secondly, this method ignores semantic information such as the complex shape of the target pests, lacks robustness to noise or fuzzy boundaries, and is prone to misjudgment [

27]. In addition, fixed thresholds are difficult to cope with the challenges of multi-scale objects and complex feature distributions in agricultural scenarios, especially performing poorly in detecting multi-category small pest objects. Therefore, the paper adopts an adaptive threshold segmentation method based on Otsu [

28], which divides the image pixels into foreground and background classes, and determines the optimal threshold

T by maximising the inter-class variance. Specifically, the probability of a pixel with grey value

i is first calculated as shown in Equation (

4).

where

denotes the number of pixels with grey value

i and

N denotes the total number of pixels. Then the weight

and the average grey value

of the pixels in the two categories are calculated separately , as shown in Equation (

5)-(8).

where

denote the weights and mean grey values of the background class pixels,

denotes the weights and mean grey values of the foreground class pixels. Finally, the inter-class variance

is calculated according to Equation (

5)-(8), as shown in Equation (

9). The

T with the largest

is selected as the optimal threshold for segmenting the grey scale feature map.

Aiming at the limitations of fixed threshold segmentation methods in the object detection task, the adaptive threshold segmentation method based on Otsu effectively solves the problem that fixed thresholds cannot dynamically adapt to the scene changes [

29] by maximising the interclass variance, and significantly improves the segmentation accuracy and robustness.

2.4. Difference-Guided Feature Fusion

Sparse convolution demonstrates significant advantages in extracting foreground object features, mainly in its ability to efficiently process sparse information and reduce computational overhead. However, despite its ability to accurately capture details of foreground objects, sparse convolution tends to ignore contextual information in background regions [

30]. This characteristic may lead to model limitations in global scene understanding, especially in crop pest detection tasks where contextual information plays a key role, e.g., the appearance of pests is usually closely related to the growing environment of the crop, the lighting conditions, and the background features. There are often complex correlations between the background and foreground, and the lack of adequate understanding of background information can significantly affect detection performance.

To address this problem, the paper proposes a lightweight difference-guided feature fusion (DGFF) method, which aims to effectively fuse background information and sparse foreground features. The method dynamically adjusts the fusion weights of both foreground and background features by guiding the network according to their saliency differences, which ensures the accurate extraction of foreground object features and enhances the global context information of the background region, and ultimately improves the detection accuracy of the model. Specifically, the pixel-level difference between the sparse features and the background features is first calculated to obtain the difference mapping , which reflects the saliency differences between the foreground and the background at different spatial locations and channels, and provides the basis for the subsequent generation of spatial and channel weights [

31], as shown in Equation (

10).

where

is the foreground feature extracted by sparse convolution and

is the global background feature. Then Gaussian blurring and normalisation are applied to each pixel position of the feature difference mapping to generate the spatial weight map

, as shown in Equation (

11).

where

x and

y denote the position coordinates of the current pixel in the feature map, and

and

denote the position coordinates of all pixels, respectively. The spatial weight map

is able to highlight regions with large differences between sparse foreground features and global background features, and ensures that the weight distribution is smooth and suppresses the effect of noise. Summing the difference maps over the spatial dimension, we obtain the channel-level weights

, as shown in Equation (

12).

where

c denotes the channel index where the current pixel is located in the feature map of the feature map, and the channel weight

is used to capture the saliency of foreground and background in different feature dimensions. Finally, the sparse features are weighted and fused with the background features using spatial weights

and channel weights

as shown in Equation (

13).

where ⊙ denotes element-by-element multiplication,

denotes the all-1 vector, which is used to extend the weighting dimension. The fused feature

contains both foreground and background features extracted by sparse convolution, which can improve the understanding of global contextual information, in addition to this, the difference-guided feature fusion method does not rely on complex attention mechanisms, and the computation is simple and efficient, which further achieves the lightweight design of the model.

Since the base detectors have a classification and a regression header in the detection framework, and the two tend to focus on different feature regions, the paper introduces an ASCBF module for each base detector respectively, as shown in

Figure 2. The sparse foreground features extracted by the ASCBF module and the global background features are fed into the detection head by feature fusion guided by feature differences. This design not only enhances the adaptability of the model to different regions, but also further optimises the detection performance.

2.5. Experimental Platform

The experiments in the paper are based on PyTorch [

32] deep learning framework and MMDetection [

33] open source object detection toolkit. The server configuration used is Intel Xeon Silver 4314, with a main frequency of 2.4Ghz, 128 RAM, and a GPU of RTX 3090 with 24 video memory. For model training in the paper, the SGD optimiser is used on the IP102 dataset, the batch size is set to 8, the initial momentum is 0.937, the weight decay rate is set to

, the initial learning rate is set to

, and the temperature parameter

in Equation (

1) is set to 1. The training set images are scaled to

in equal proportions to be input into the network.

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

The experiments in the paper use average precision (AP), mean average precision (mAP), floating point operations (GFLOPs), and frames per second (FPS) as the metrics to measure the precision and efficiency of the detection model. The AP metrics are calculated from the precision and recall, and the specific formula is shown in Equation (

14)-(17).

where

denotes the number of correctly predicted positive samples as positive samples,

denotes the number of incorrectly predicted negative samples as positive samples,

denotes the number of incorrectly predicted positive samples as negative samples, and

metrics are the average of

of all the categories, where the number of categories included is

N. The

@0.5:0.95 used in the paper refers to the average

value with IOU thresholds in the range of 0.5-0.95. GFLOPs and FPS denote the computational quantity and detection speed of the model, respectively.

3. Implementation and Results

In this section, to exemplify the performance of the ASCBF module, we will validate it in combination with four prevailing object detectors, and the specific experimental results will be shown in

Section 3.1. In this paper, adaptive multilayer mask-ratio strategy(AMMS), adaptive threshold segmentation method(ATSM) and difference-guided feature fusion method(DGFF) are introduced in ASCBF module, respectively. Compared with the fixed mask-ratio strategy, AMMS module can significantly reduce the computational redundancy caused by too high mask-ratios, so this section focuses on analysing the rationality of ATSM and DGFF module. To further validate the effectiveness of the ATSM and DGFF module, we will perform experimental validation in

Section 3.2 and

Section 3.3, respectively. Then, we will perform ablation experiments on the three modules in order to verify the mutual enhancement between the three modules, as described in

Section 3.4. Finally, we will perform comparison experiments with other state-of-the-art lightweight detectors to verify the excellent performance of our proposed ASCBF module, and the experimental results will be shown in

Section 3.5.

3.1. Analysis of Experimental Results with Different Base Detectors

The ASCBF network proposed in the paper is a plug-and-play modular network, in order to verify the effectiveness of ASCBF, the paper combines the ASCBF module with four classical object detection algorithms, namely RetinaNet [

34], Faster-RCNN [

35], FSAF [

36], and CenterNet [

37], the experimental results are shown in

Table 2. According to the experimental results in the table, the introduction of the ASCBF module results in significant performance gains for each model, mAP for RetinaNet is increased from 25.6% to 26.2%, and FPS from 20.41 to 26.57, an increase of about 15%, mAP for Faster-RCNN is increased from 26.0% to 27.2%, and FPS is increased to 32.59, an increase of about 25%, mAP of FSAF improves from 28.3% to 28.9%, and FPS improves to 34.36, and the GFLOPs are reduced, mAP of CenterNet improves from 27.6% to 28.3%, and FPS improves dramatically to 40.40, an increase of about 16%, which exhibits better computational efficiency and performance improvement. Overall, the ASCBF module demonstrates the utility and efficiency of the ASCBF module by significantly increasing the inference speed and reducing the computational complexity while improving the accuracy.

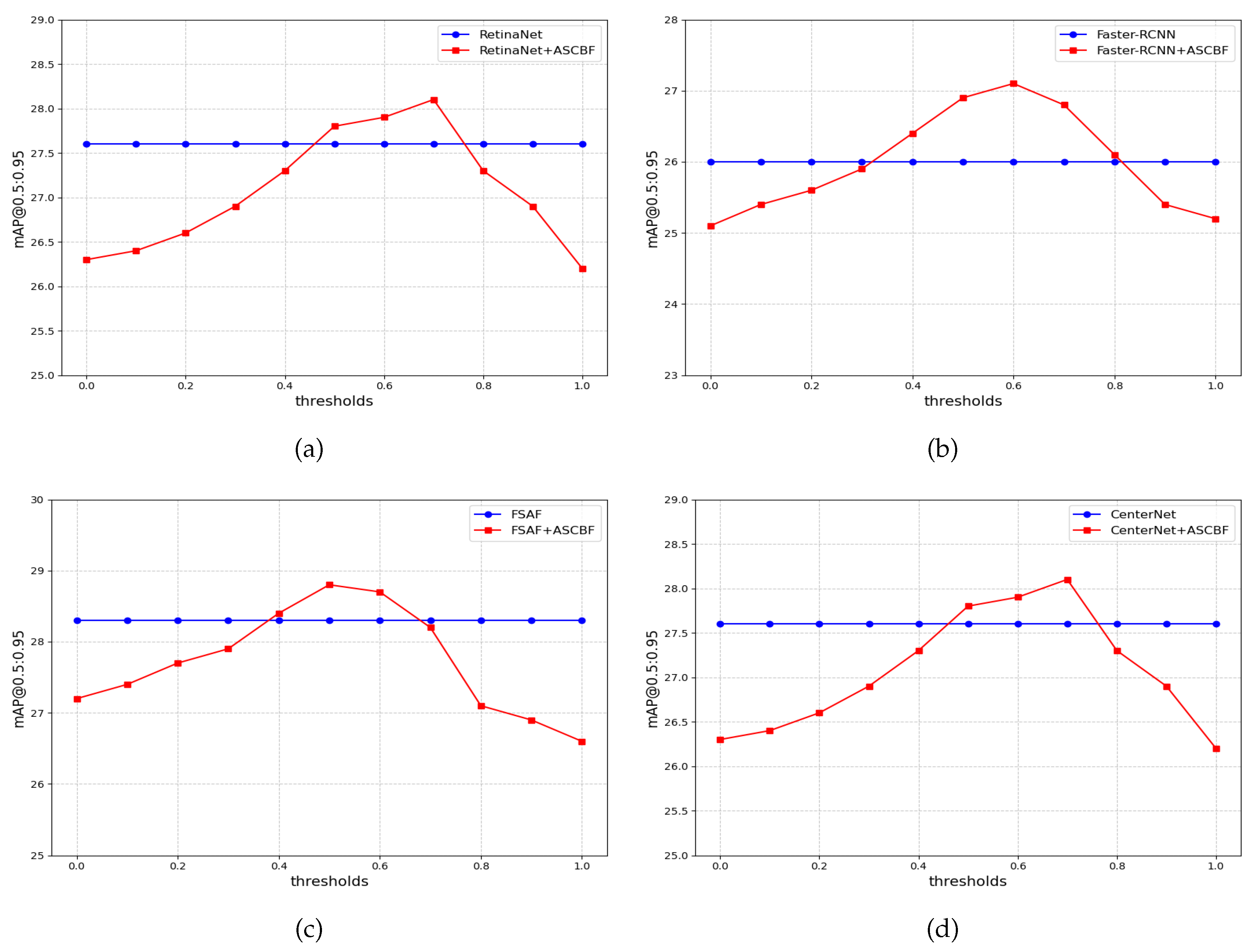

3.2. Analysis of the Effectiveness of the ATSM Module

In order to verify the effectiveness of adaptive threshold segmentation method (ATSM) in segmenting foreground features, in this section, experiments are conducted for the detection performance of ASCBF module under different thresholds in four classical base detectors and the results of the experiments are shown in

Figure 5.

From the experimental results, it can be observed that when the threshold is fixedly set to 0.5, the model is still not the optimal performance even though it has shown good detection performance. Therefore, the fixed-threshold approach fails to give full play to the potential advantages of the adaptive multilayer mask-ratio strategy. Combined with the analysis of the crop pest detection task, certain pests tend to evolve features (e.g., colours, etc.) that are similar to their environment in order to hide from natural enemies[

38], thus making it easier to hide. In terms of the feature level of the image, the fixed threshold method is difficult to effectively extract foreground features that are similar to the background features, thus limiting the detection accuracy of the model in complex environments, whereas the adaptive dynamic calculation of the optimal threshold can avoid the degradation of the model performance due to the lack of information of the edge features that are not clear enough to extract the foreground features.

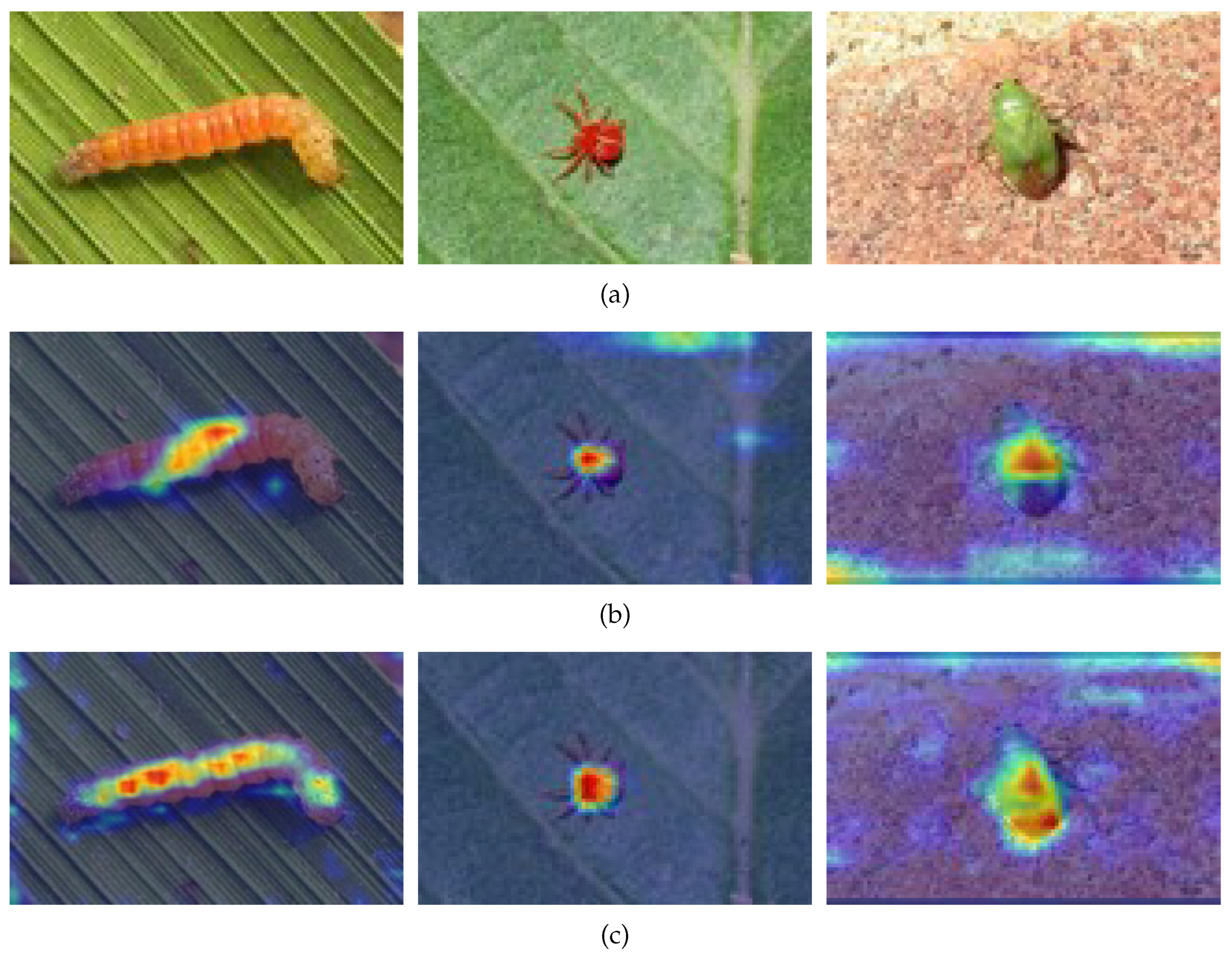

3.3. Analysis of the Effectiveness of the DGFF Module

The traditional sparse convolutional framework will directly use the activation elements for group normalisation after extracting the foreground features, which fails to make good use of the background features that contain numerous useful information. In order to verify the effectiveness of the difference-guided feature fusion method, the paper carries out experiments for the specific performance of the two different feature processing modes in the RetinaNet-based detector, and the feature heatmaps are shown in

Figure 6.

From the results in

Figure 6, it can be seen that the range of the feature heat map of the difference-guided feature fusion method is larger, and the shape of the focus area is closer to the shape characteristics of the object itself. Combined with the analysis of the crop pest detection task, when the pest to be detected has its corresponding category of special background (e.g., tree trunks, leaves, etc.), then the feature fusion module can obtain the difference features of the background, so as to be able to better identify the type of pest. This is especially important in situations where pests are camouflaged or blend into complex backgrounds, as it helps the model distinguish the pest from similar-looking background features [

39]. This further demonstrates that the difference-guided feature fusion method can learn deeper information in the features (e.g., the shape of the pests, the background of the habitat, etc.), allowing for a more nuanced understanding of the pest’s environment and improving the detection of pests in varied conditions. Furthermore, by focusing on both the pest and its surrounding habitat, this method can potentially reduce false positives, which are common when background clutter is mistaken for pests. In summary, the method not only enhances the extraction of useful features for the object detection task of crop pests but also enables the model to perform more accurately in challenging, real-world agricultural settings [

40].

3.4. Ablation Experiment

In order to further verify the mutual reinforcement among the three modules of adaptive multilayer mask ratio strategy(AMMS), adaptive threshold segmentation method(ATSM) and difference-guided feature fusion method(DGFF) in ASCBF, these three modules are integrated into the same base detector for ablation experiments in this section. The experiments are framed in RetinaNet base detector and the experimental results are shown in

Table 3.

From the experimental results in

Table 3, it can be seen that when the sparse convolutional network with adaptive multilayer mask-ratio with fixed threshold is used, the mAP@0.5:0.95 value decreases by 0.5% although it still reduces the computational amount by 33%, and this status quo can be improved after the adaptive threshold segmentation method is used, but it still falls short of the detection performance of the baseline model, and when the difference mapping guided feature fusion method is introduced, the complementary background feature When the difference-guided feature fusion method is introduced, the mAP value of this paper’s model, which complements the background feature information, exceeds that of the baseline model. In addition, the GFLOPs value of the model is significantly reduced, and the FPS value is greatly improved, reflecting the balanced detection performance and superior detection efficiency [

41], which fully proves the effectiveness of this paper’s method, and is in line with the expected goal of the object detection task in the resource-limited scenario.

3.5. Comparison Experiments with Other State-of-the-Art Lightweight Detectors

To further validate the performance and efficiency of the ASCBF module proposed in this paper, this section compares it with the state-of-the-art lightweight model QueryDet [

21], which uses a novel querying mechanism of cascading sparse queries to accelerate the inference of a dense FPN-based object detector, and MobileNet V4 [

10], which performs the trade-off between detection accuracy and speed through universal inverted bottlenecks(UIB) and neural architecture search(NAS) for the trade-off between detection accuracy and speed. The experiments are still framed by RetinaNet base detector, and the experimental results are shown in

Table 4.

From the results in

Table 4, it can be seen that compared to the state-of-the-art lightweight models QueryDet [

21] and MobileNet V4 [

10], the ASCBF module proposed in this paper has a significant reduction in GFLOPs and a significant increase in FPS along with an increase in mAP@0.5:0.95, which is significantly better than them in terms of accuracy and efficiency.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we have presented an adaptive sparse convolution network with background-feature fusion (ASCBF) network for improving the accuracy and efficiency of crop pest detection. Our main contributions can be summarized as follows:

(1) We introduced an adaptive multi-layer mask-ratio strategy to dynamically adjust the sparsity of feature maps at different layers of FPN. This strategy allows the network to focus on the most informative features while reducing computational overhead. By minimizing the mask loss, the network is able to generate binary sample masks that are closer to the optimal mask ratios of ground truth labels, thereby extracting better sparse foreground features and achieving better coverage of the foreground region.

(2) To address the limitations of fixed threshold segmentation in handling feature distribution differences of different pests and complex environmental scenes, we adopted an adaptive threshold segmentation method based on Otsu. This method divides the image pixels into foreground and background classes and determines the optimal threshold by maximizing the inter-class variance. This approach enhances the network’s ability to accurately segment pest objects from their backgrounds.

(3) We proposed a difference-guided lightweight feature fusion method to effectively integrate foreground and background features. By dynamically adjusting the fusion weights of both foreground and background features based on their saliency differences, the network is able to accurately extract foreground features while enhancing the global context information of the background region. This method not only improves detection performance but also achieves a lightweight design of the model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M.; methodology, F.M.; software, F.M.; validation, F.M.; formal analysis, F.M. and H.L.; investigation, F.M.; resources, F.M.; data curation, F.M. and H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M.; writing—review and editing, F.M. and Q.M.; visualization, F.M.; supervision, Q.M. and Y.Z.; project administration, F.M.; funding acquisition, Q.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research was funded by the National Nature Science Foundation of China under Grant 62176106, the Special Scientific Research Project of the School of Emergency Management of Jiangsu University under Grant KY-A-01, the Key Project of National Nature Science Foundation of China under Grant U1836220, the Jiangsu Key Research and Development Plan Industry Foresight and Key Core Technology under Grant BE2020036, and the Project of Faculty of Agricultural Engineering of Jiangsu University under Grant NGXB20240101.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu H, Zhan Y, Xia H, et al. Self-supervised transformer-based pre-training method using latent semantic masking auto-encoder for pest and disease classification. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 2022, 203, 107448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal M, Gupta V, Aamash M, et al. Machine learning for pest detection and infestation prediction: A comprehensive review. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery. 2024, 14, 1551. [Google Scholar]

- Ji W, Pan Y, Xu B, et al. A real-time apple targets detection method for picking robot based on ShufflenetV2-YOLOX. Agriculture. 2022, 12, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu T, Wang W, Gu J, et al. Research on apple object detection and localization method based on improved yolox and rgb-d images. Agronomy. 2023, 13, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu Z, Guo Y, Zhang L, et al. Improved Lightweight Zero-Reference Deep Curve Estimation Low-Light Enhancement Algorithm for Night-Time Cow Detection. Agriculture. 2024, 14, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsken T, Metzen J H, Hutter F. Neural architecture search: A survey. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2019, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gou J, Yu B, Maybank S J, et al. Knowledge distillation: A survey. International Journal of Computer Vision. 2021, 129, 1789–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao C, Liu R W, Qu J, et al. Deep learning-based object detection in maritime unmanned aerial vehicle imagery: Review and experimental comparisons. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence. 2024, 128, 107513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang T, Chu X, Liu Y, et al. Cbnet: A composite backbone network architecture for object detection. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing. 2022, 31, 6893–6906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin D, Leichner C, Delakis M, et al. MobileNetV4: Universal Models for the Mobile Ecosystem. European Conference on Computer Vision(ECCV), Springer, Cham, 2025; pp. 78-96.

- Ma N, Zhang X, Zheng H T, et al. Shufflenet v2: Practical guidelines for efficient cnn architecture design. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), Springer, Cham, 2018; pp. 78-96.

- Shen F, Ye H, Liu S, Zhang J, Wang C, Han X, Yang W. Boosting Consistency in Story Visualization with Rich-Contextual Conditional Diffusion Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.02482.

- Shen F, Jiang X, He X, Ye H, Wang C, Du X, Li Z, Tang J. IMAGDressing-v1: Customizable Virtual Dressing. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.12705.

- Shen F, Ye H, Zhang J, Wang C, Han X, Yang W. Advancing pose-guided image synthesis with progressive conditional diffusion models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06313.

- Shen F, Tang J. IMAGPose: A Unified Conditional Framework for Pose-Guided Person Generation. In Proceedings of the Thirty-eighth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. 2024.

- Yan Y, Mao Y, Li B. Second: Sparsely embedded convolutional detection. Sensors. 2018, 18, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Li Y, Zhang X, et al. Focal sparse convolutional networks for 3d object detection. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition(CVPR), 2022; pp. 5428-5437.

- Hong Q, Liu F, Li D, et al. Dynamic sparse r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition(CVPR), 2022; pp. 4723-4732.

- Du B, Huang Y, Chen J, et al. Adaptive sparse convolutional networks with global context enhancement for faster object detection on drone images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition(CVPR), 2023; pp. 13435-13444.

- Song L, Li Y, Jiang Z, et al. Fine-grained dynamic head for object detection. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems(NeurIPS), 2020, 33; pp. 11131-11141.

- Yang C, Huang Z, Wang N. QueryDet: Cascaded sparse query for accelerating high-resolution small object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on computer vision and pattern recognition(CVPR), 2022; pp. 13668-13677.

- Gallego G, Gehrig M, Scaramuzza D. Focus is all you need: Loss functions for event-based vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition(CVPR), 2019; pp. 12280-12289.

- Wu X, Zhan C, Lai Y K, et al. Ip102: A large-scale benchmark dataset for insect pest recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition(CVPR), 2019; pp. 8787-8796.

- Liu H, Zhan Y, Sun J, et al. A transformer-based model with feature compensation and local information enhancement for end-to-end pest detection. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 2025, 231, 109920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verelst T, Tuytelaars T. Dynamic convolutions: Exploiting spatial sparsity for faster inference. Proceedings of the ieee/cvf conference on computer vision and pattern recognition(CVPR), 2020; pp. 2320-2329.

- Wu Z, Gao Y, Li L, et al. Semantic segmentation of high-resolution remote sensing images using fully convolutional network with adaptive threshold. Connection Science. 2019, 31, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Gao Z, Zhang Y, et al. Real-time detection and location of potted flowers based on a ZED camera and a YOLO V4-tiny deep learning algorithm. Horticulturae. 2021, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu X, Xu S, Jin L, et al. Characteristic analysis of Otsu threshold and its applications. Pattern recognition letters. 2011, 32, 956–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, Chen Z, Ali S, et al. Multi-class detection of cherry tomatoes using improved Yolov4-tiny model. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering. 2023, 16, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Sun Y, Huang H, et al. Pest region detection in complex backgrounds via contextual information and multi-scale mixed attention mechanism. Agriculture. 2022, 12, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Tan X, Zhang P, et al. A CBAM based multiscale transformer fusion approach for remote sensing image change detection. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing. 2022, 15, 6817–6825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imambi S, Prakash K B, Kanagachidambaresan G R. PyTorch. Programming with TensorFlow: solution for edge computing applications. 2021, 87–104.

- Kai Chen, Jiaqi Wang, Jiangmiao Pang, Yuhang Cao, Yu Xiong, Xiaoxiao Li, Shuyang Sun, Wansen Feng, Ziwei Liu, Jiarui Xu, et al. Mmdetection: Open mmlab detection toolbox and benchmark. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.07155.

- Lin, T. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.02002. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.01497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu C, He Y, Savvides M. Feature selective anchor-free module for single-shot object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition(CVPR), 2019; pp. 840-849.

- Duan K, Bai S, Xie L, et al. Centernet: Keypoint triplets for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision(CVPR), 2019; pp. 6569-6578.

- Sun J, He X, Ge X, et al. Detection of key organs in tomato based on deep migration learning in a complex background. Agriculture. 2018, 8, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie H, Zhang Z, Zhang K, et al. Research on the visual location method for strawberry picking points under complex conditions based on composite models. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2024, 104, 8566–8579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li W, Zheng T, Yang Z, et al. Classification and detection of insects from field images using deep learning for smart pest management: A systematic review. Ecological Informatics. 2021, 66, 101460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Lu Y, Zhao Y, et al. Ts-yolo: an all-day and lightweight tea canopy shoots detection model. Agronomy. 2023, 13, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).