1. Introduction

Innovation and invention have long been regarded as processes driven by creativity, problem-solving, and collaboration. At the heart of these processes lies the dialogue between inventors, which serves as a medium for exchanging ideas, defining goals, identifying constraints, and iteratively refining solutions. Such dialogues are inherently structured yet dynamic, reflecting the interplay between constraints imposed by the problem space and the conceptual flexibility required to generate novel solutions. This paper proposes a formal model for inventor dialogues, framing invention as a process that can be analyzed through the lens of category theory and constraint satisfaction problems (CSPs).

Representing inventions in the form of dialogue has significant pedagogical value because it engages learners actively, enhances comprehension, and stimulates critical thinking. Dialogues allow students to follow a conversation between characters, making it easier to explore ideas step-by-step. Also, dialogues simulate a classroom discussion where learners can anticipate questions and mentally respond, reinforcing understanding. Dialogue introduces contrasting viewpoints, pushing learners to evaluate and synthesize ideas. Moreover, it encourages learners to think hypothetically—how an invention might impact society or solve specific problems.

An Example Scenario on 3D Bioprinting for Organ Transplants can look as follows:

Student A: "Why can't we just grow organs in labs?"

Mentor: "That's what 3D bioprinting tries to solve. Instead of waiting for donors, it prints tissues layer by layer."

Student B: "But what materials do they use?"

Mentor: "Special bio-inks made from living cells. For example, they use stem cells to build custom tissue structures." |

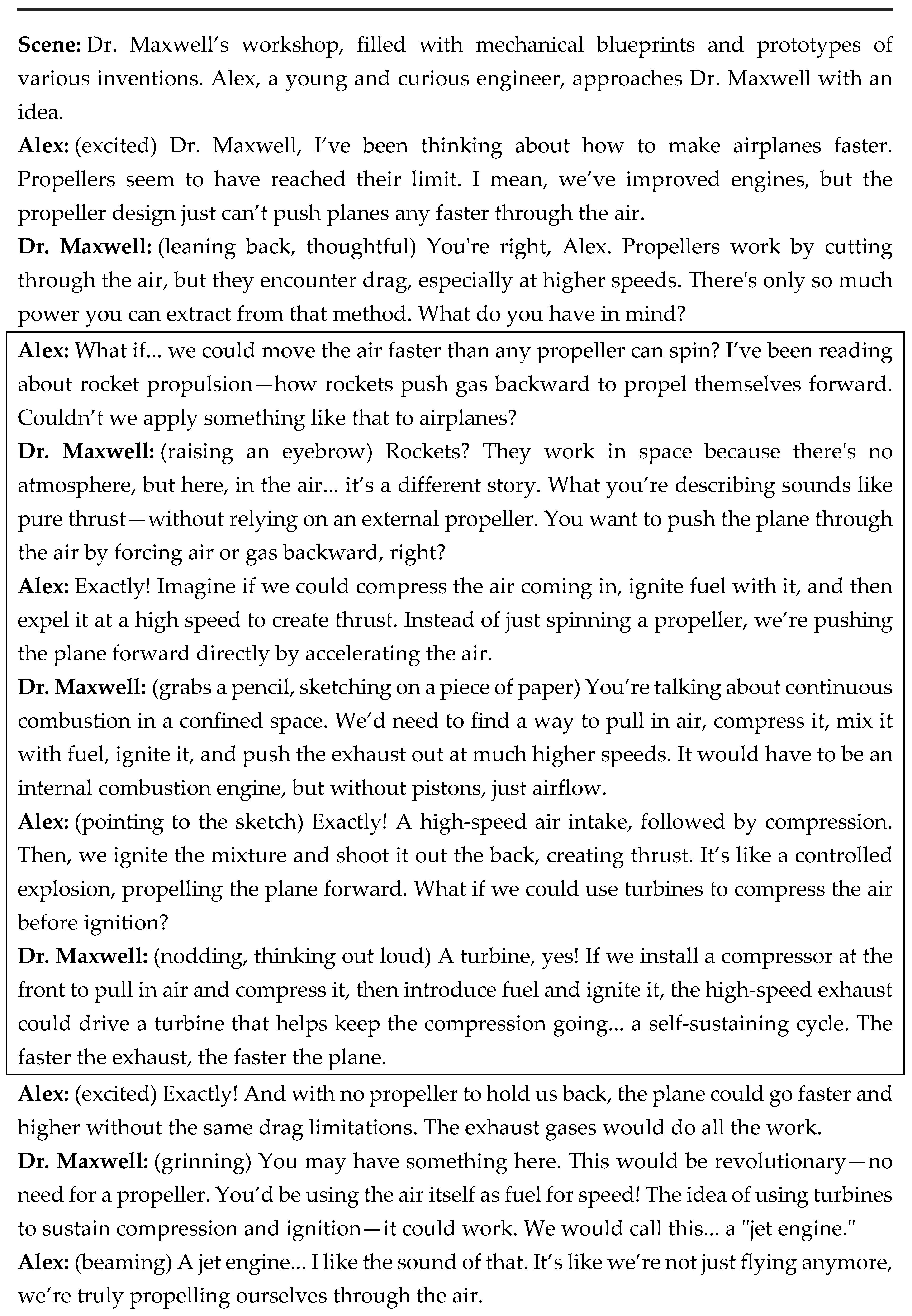

There is indeed a noticeable scarcity of documented records capturing actual dialogues between famous inventors. While it is widely acknowledged that many groundbreaking inventions likely emerged from discussions, debates, and collaborative exchanges of ideas, concrete examples of such inventive dialogues remain elusive. Conversations between inventors and their peers may have played a pivotal role in refining concepts, addressing technical challenges, and sparking creative insights. However, the absence of preserved transcripts or detailed accounts has left this aspect of the inventive process largely speculative. Despite thorough searches, the authors were unable to uncover any verifiable examples of dialogues that directly contributed to specific inventions through online sources. This gap highlights the need for further archival research and exploration into personal correspondences, laboratory notebooks, and memoirs that might shed light on the conversational dynamics behind some of history’s most transformative innovations (

Figure 1).

One famous dialogue that led to a well-known invention occurred between Alexander Graham Bell and his assistant Thomas Watson during the development of the telephone in 1876 (

Figure 2).

While experimenting with the device, Bell famously said:

"Mr. Watson, come here. I want to see you."

These were the first words transmitted via a telephone, marking a groundbreaking moment in communication history. This exchange demonstrated the practical application of voice transmission over electric wires, revolutionizing global communication.

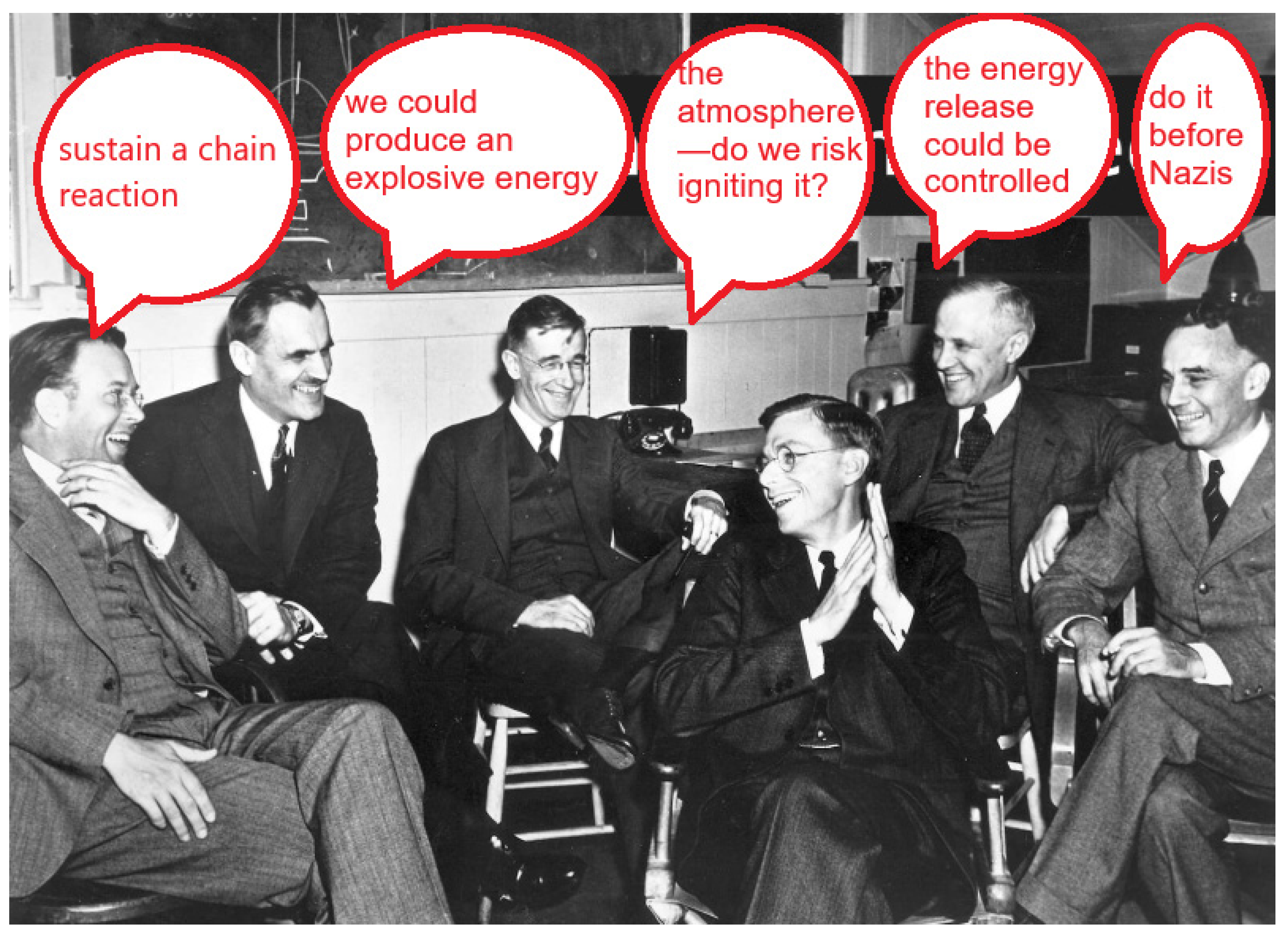

Another example is the Manhattan Project discussions involving Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard in the 1930s. Their letters to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, warning of Nazi Germany's potential to build atomic weapons, led to the development of the atomic bomb during World War II (

Figure 3).

Oppenheimer:

"If we can sustain a chain reaction, what yields are we realistically expecting?"

Enrico Fermi:

"In theory, with enough uranium-235 or plutonium, we could produce an explosive energy equivalent to thousands of tons of TNT."

Edward Teller:

"And if the reaction runs away, the atmosphere—do we risk igniting it?"

Oppenheimer (pausing):

"That’s precisely what we must calculate. Safety first. But if the calculations hold..."

Hans Bethe:

"Then the energy release could be controlled—directed—enough to end the war."

Oppenheimer (nodding):

"But at what cost? Still, we have to proceed. We cannot let the Nazis get there first."

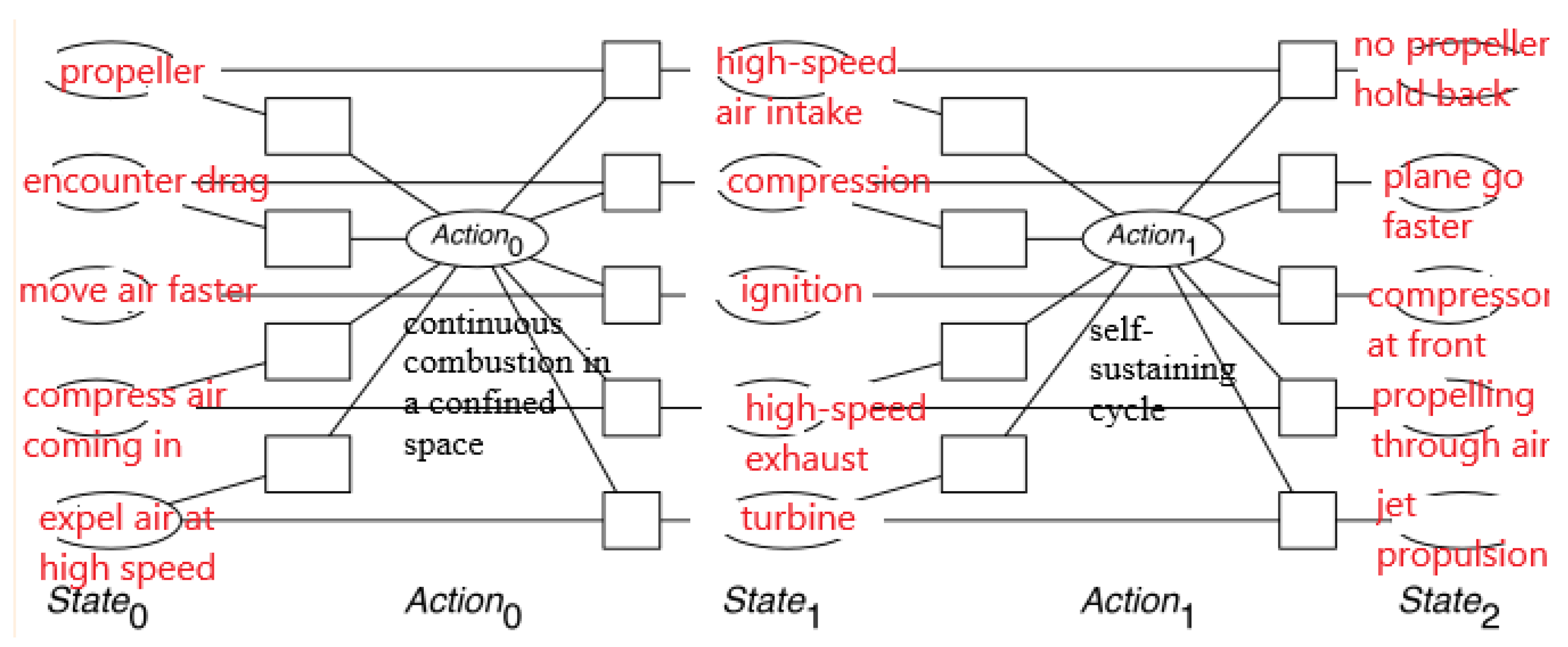

Traditional approaches to modeling invention often emphasize brainstorming techniques, heuristic optimization, or rule-based reasoning systems. While these methods capture aspects of creativity, they frequently overlook the formalizable structure of invention dialogues, which integrate logical reasoning, constraint handling, and conceptual blending. This paper addresses this gap by providing a mathematical framework that not only represents the informational flow within inventor dialogues but also models invention as a form of constraint satisfaction that balances feasibility with novelty.

We conceptualize invention as a dialogue-driven process where inventors collaboratively explore and refine a design space through constraints and transformations. In this framework:

Category theory provides the algebraic tools to formalize relationships between concepts, capturing transformations and mappings between ideas.

Constraint satisfaction problems define the boundaries within which invention operates, modeling constraints as logical and computational entities to ensure solutions are both feasible and innovative.

By integrating these two formal systems, we bridge the linguistic and mathematical dimensions of invention, enabling precise modeling of dialogue dynamics while preserving the exploratory nature of human creativity (

Figure 4).

Contribution

This paper makes the following contributions (

Figure 5):

- 1)

Dialogue Formalism for Invention – It develops a formal model for inventor dialogues, highlighting their structure, patterns, and transitions.

- 2)

Category-Theoretic Representation – It applies category theory to describe transformations in idea development, capturing abstraction, refinement, and integration processes.

- 3)

Constraint Satisfaction Problem Framework – It frames invention as a CSP, modeling constraints and dependencies within the design process.

- 4)

Unified Model for Creative Reasoning – It integrates the above methods to provide a unified computational framework for analyzing and supporting invention dialogues.

- 5)

Developing pedagogical value for invention dialogues.

This research is motivated by the need for structured frameworks that support invention in domains ranging from engineering and design to AI-driven innovation platforms. The proposed model has implications for computational creativity, knowledge representation, and collaborative AI systems, offering tools to simulate and enhance human-machine co-creation.

2. Categorial Theory Formalization

Category theory provides a universal language for defining interactions among objects in all of mathematics, physics, computer science, and mathematical logic. Category theory has recently seen increasing use in machine learning, including dimensionality reduction (McInnes et al. 2018) and clustering. One unique aspect of defining machine learning as extending functors in a category (Mahadevan 2024).

2.1. First Example of an Invention Dialogue

We introduce the full dialogue and highlight its entities and components for categorial analysis (

Figure 6).

We identified three components of an invention dialogue highlighted in three ways :

- 1)

Problem formulation

- 2)

Problem resolution attempt

- 3)

Successful break-through

Handling components and entities is important as we design prompts for LLMs to auto build invention dialogues. In prompt constructions, we need to outline the variable and constant parts of prompts. Domains in a dialogue come via the certain sequence, and entities could be varied to obtain a wide spectrum of dialogues.

2.2. Categorial Model

To formalize a model of an invention dialogue using category theory, we start by defining key components such as objects, morphisms, functors, and natural transformations. Here's a breakdown of how to build the model step by step:

1. Objects in the Dialogue Model

In the categorical framework, objects in a dialogue represent participants, physical entities under discussion, and mental attributes associated with these entities. Specifically:

Participants: People engaged in the dialogue (e.g., inventors, engineers).

Physical Objects: The things being discussed, such as the engine or parts of the invention.

Mental Attributes: Intentions, ideas, or desires related to physical objects (e.g., "intent to improve an engine").

We will denote these objects as:

P for a participant in the dialogue.

O for a physical object (e.g., the engine).

A for a mental attribute (e.g., an intent to improve the engine).

An epistemic category models a state of knowledge or perspective of a dialogue participant. It contains both the physical objects of interest to a participant and the mental attributes associated with those objects.

For each participant P, an epistemic category EP can be defined as:

Objects in EP: These are pairs (O,A), where O is a physical object and A is a mental attribute associated with O.

Morphisms in EP : These represent transitions between different mental states or perspectives regarding the same object or different objects. For instance, a morphism could represent the change in a participant’s view about how to improve an engine, or a shift in focus from one part of the engine to another.

An epistemic functor F maps one epistemic category (corresponding to an initial dialogue state) to another epistemic category (corresponding to a consecutive dialogue state). This captures the evolution of the dialogue, reflecting how a participant's knowledge or intentions change as the conversation progresses.

For each participant P, an epistemic functor F:→: maps:

Objects: (O,A) in : to new objects (O′,A′) in :, where O′ and A′ represent updated knowledge or intentions about the physical object after some part of the dialogue.

Morphisms: Any transition or change in mental state or knowledge about physical objects is mapped from one dialogue state to another.

The category of all epistemic functors consists of all possible functors between epistemic categories for each participant across different stages of the dialogue. This can be considered as representing the structure of the entire dialogue process.

Each participant's epistemic functor can be seen as a natural transformation between different epistemic categories. Specifically, a natural transformation η:F→G between two functors F, G would describe a transformation of dialogue states (and their associated changes in knowledge or mental attitudes) that respects the underlying structure of the participants' epistemic categories.

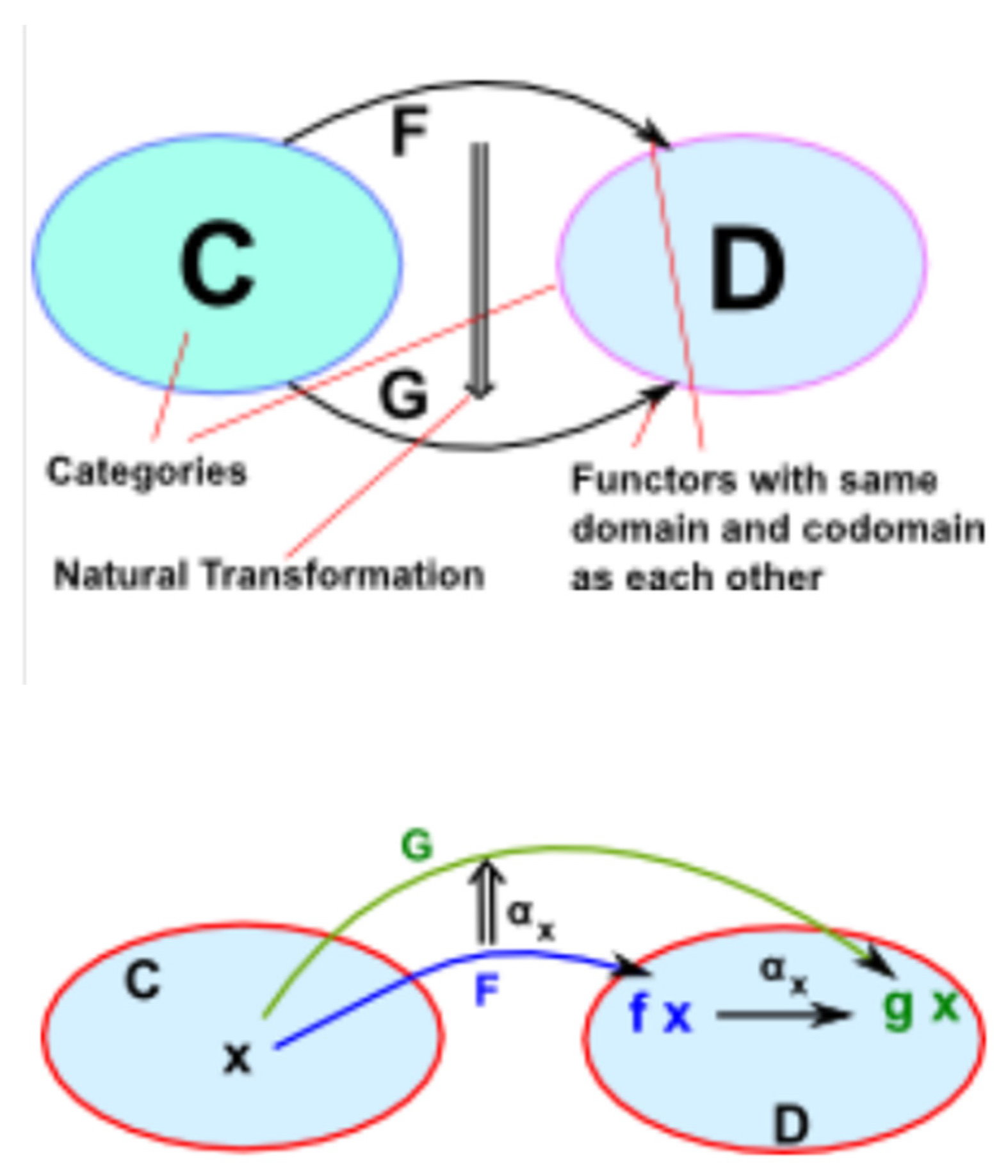

2.3. Defining Natural Transformation

A natural transformation is a mapping between two functors. The functors must have the same domain and codomain as each other. There is also the naturality square condition that must apply for this to be a natural transformation as we shall see below.

We take an object

x in

C and we map it into a morphism in

D (

Figure 7). For every object x in C there is a morphism in D (

f x→

g x) known as the components of α at

x (written α

x).

So now we know what happens to an object in

C, we now want to know what happens to structure in

C, for this we see what happens to a morphism in

C. A morphism in

C would map to two component morphisms in

D. This diagram must commute for every morphism in

C. So

αx is the component of the natural transformation at

x, and

αy is the component of the natural transformation at

y. For naturality we require that the square in

D commutes (

Figure 8):

where: M = F m and N = G m

so: αy• F m = G m • αx

5. Dialogue Model as Natural Transformation

The natural transformation formalizes the idea that different paths of reasoning, questioning, and discussing in the dialogue are systematically related. A dialogue model can now be viewed as a natural transformation between epistemic functors F and G for different participants P.

For example, if participant P1 and participant P2 are discussing how to improve an engine, and they start from different initial states (different epistemic categories the dialogue serves as a natural transformation between the functors , representing the change in their perspectives.

In this model of invention dialogue:

Objects represent participants, physical objects, and associated mental attributes.

Epistemic categories capture the knowledge and intentions about physical objects for each participant.

Epistemic functors map changes in knowledge and mental attributes over the course of the dialogue.

Natural transformations between functors model the relationships between the evolving perspectives of different participants.

This framework allows us to represent a structured, categorical model of a dialogue about an invention, where participants' knowledge, ideas, and intentions evolve in response to the conversation.

2.4. Invention as Constrain Satisfaction

Formulating an invention as a CSP involves defining the problem in terms of variables, domains, and constraints. This method provides a structured way to identify and solve the core challenges involved in designing an invention. CSP consists of variables (elements of the system that need to be determined, domains (the set of possible values for each variable), and constraints (relationships or rules that define how the variables interact or limit their values). The goal is to assign values to the variables from their domains such that all constraints are satisfied.

Steps to Formulate an Invention via CSP are as follows:

1) Define the problem. Identify the key functional goals and requirements of the invention. Break them down into measurable components. For example, if invention is a solar-powered water purifier, then the goal is to purify water effectively, operate using solar power, be portable, and affordable.

2) Identify variables, determining the key design elements that influence the invention. These could be physical dimensions, performance characteristics, or system components. For the solar-powered water purifier, the variables are:

- ○

Type of purification technology (x1): e.g., UV filtration, reverse osmosis.

- ○

Solar panel size (x2).

- ○

Battery capacity (x3).

- ○

Material type (x4).

- ○

Weight (x5).

3) Define domains, specifying the possible values each variable can take. Domains should reflect realistic choices or ranges.

- ○

x1: {UV filtration, reverse osmosis, activated carbon}.

- ○

x2: {50 cm² to 500 cm²}.

- ○

x3: {10 Wh to 50 Wh}.

- ○

x4: {plastic, aluminum, stainless steel}.

- ○

x5: {1 kg to 5 kg}.

4)Specify constraints, defining the relationships or rules that must hold between variables. These capture the functional requirements and practical limitations of the invention.

- ○

The solar panel size (x2) must generate enough energy to power the purification system (x1).

- ○

The battery capacity (x3) must store sufficient energy for nighttime operation.

- ○

The total weight (x5) must be less than 5 kg to ensure portability.

- ○

The material (x4) must be non-toxic and corrosion-resistant.

- ○

The cost of components must not exceed a certain budget.

5) Solve the CSP using a CSP solver to find values for the variables that satisfy all constraints. This step often involves optimization techniques to identify the best solution (e.g., minimize cost, maximize efficiency). In our example, the solver might determine:

- ○

x1: UV filtration,

- ○

x2: 200 cm² solar panel,

- ○

x3: 20 Wh battery,

- ○

x4: plastic,

- ○

x5: 3 kg.

2.5. From Categories to Constrain Satisfaction

From the standpoint of category theory, constraint propagation can be viewed as morphisms.

Constraints, variables, and domains are treated as objects in a category.

Propagation rules (e.g., arc consistency algorithms) are modeled as morphisms that map objects (CSP states or variable domains) to other objects. These morphisms encode how constraints reduce or refine possible variable assignments.

A functor is then a mapping between categories that lifts the propagation process to a higher level of abstraction. For instance: category 1 represents the CSP problem space (variables, domains, and constraints), and category 2 represents transformations or refined solutions (e.g., narrowed domains, more consistent variable assignments). The functor maps CSP objects and propagation morphisms in one category to another category where propagation has been applied systematically.

In an abstract CSP solvers, functors could represent the transition from the initial CSP state to a refined state after applying propagation algorithms:

- 1)

Type systems for CSPs: in programming, functors might implement CSP propagation rules while preserving type safety and compositionality.

- 2)

Optimization frameworks: using category theory, a functor could model the search process in constraint satisfaction, ensuring it respects certain mathematical properties (e.g., monotonicity or consistency).

If the reader is familiar with functional programming: A "constraint satisfaction propagation functor" could represent something like a monad or applicative functor that applies propagation rules to CSP states in a composable way. For instance, a functor might encapsulate the propagation process, allowing transformations like propagate : CSP → CSP to be composed while maintaining structure.

Hence a CSP propagation morphism functor likely refers to a structured, compositional framework (inspired by category theory) for modeling constraint satisfaction and propagation. It highlights morphisms as transformations (like propagation rules) between CSP states, and functors as mappings between categories that abstract the propagation process, enabling compositional and reusable algorithms.

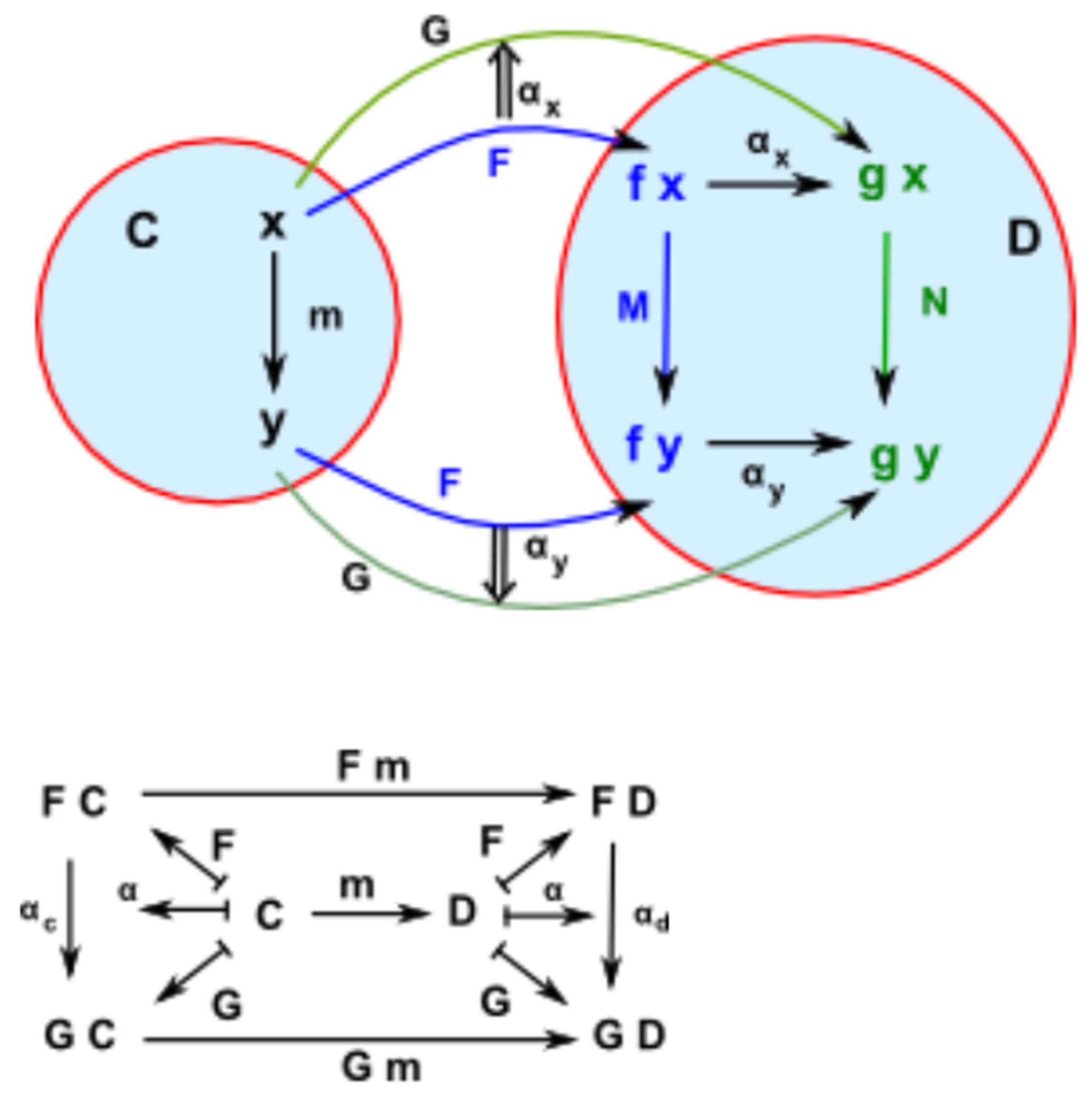

3. Phases of Invention Dialogue

Invention dialogues share a common structure that drives the discovery process. Here is the breakdown of invention dialogue features (

Figure 9):

- 1)

Problem Identification: Each dialogue begins with the recognition of a challenge or limitation in the current technology or approach. The characters often express frustration or curiosity about an issue that needs solving.

- 2)

Hypothesis or Idea Introduction: A new idea, hypothesis, or alternative approach is proposed, typically by a second character or as part of a collaborative brainstorming process. This is often based on an understanding of existing science or technology, suggesting a new path.

- 3)

Discussion of Feasibility: The characters explore the feasibility of the proposed idea, often discussing its theoretical basis, challenges, or how it differs from current methods. There may be skepticism or clarification, but the characters ultimately show enthusiasm about testing the idea.

- 4)

Testing or Experimentation: The conversation moves towards a plan for experimentation or testing the new idea. The characters outline a basic methodology to see if their theory holds.

- 5)

Anticipation of Impact: The dialogue ends with excitement or realization of the potential impact of their innovation. The characters foresee how their discovery could revolutionize a field or solve a significant problem.

This structure mirrors real-world innovation processes, where problem-solving, hypothesis generation, collaborative brainstorming, and practical experimentation lead to groundbreaking discoveries.

In terms of its sequential structure, an invention dialogue includes three phases:

- 1)

Defining the problem and setting the intent to invent. The process begins with clearly articulating the problem at hand. This involves understanding the challenge, identifying the constraints, and expressing a deliberate intent to discover a solution. The dialogue here focuses on framing the problem, setting objectives, and fostering a mindset geared toward innovation.

- 2)

Collaborative problem-solving: the invention session. In this phase, the invention process is approached as solving a Constraint Satisfaction Problem (CSP). This involves systematically exploring potential solutions within the defined constraints, iterating through possibilities, and refining ideas. The dialogue revolves around brainstorming, analyzing trade-offs, and experimenting with creative strategies to overcome obstacles.

- 3)

Achieving the invention breakthrough. The final phase is marked by the moment when a viable solution emerges, and the CSP is successfully resolved. The dialogue here shifts to celebrating the breakthrough, detailing the solution, and reflecting on the journey of discovery. This phase also sets the stage for translating the solution into actionable outcomes.

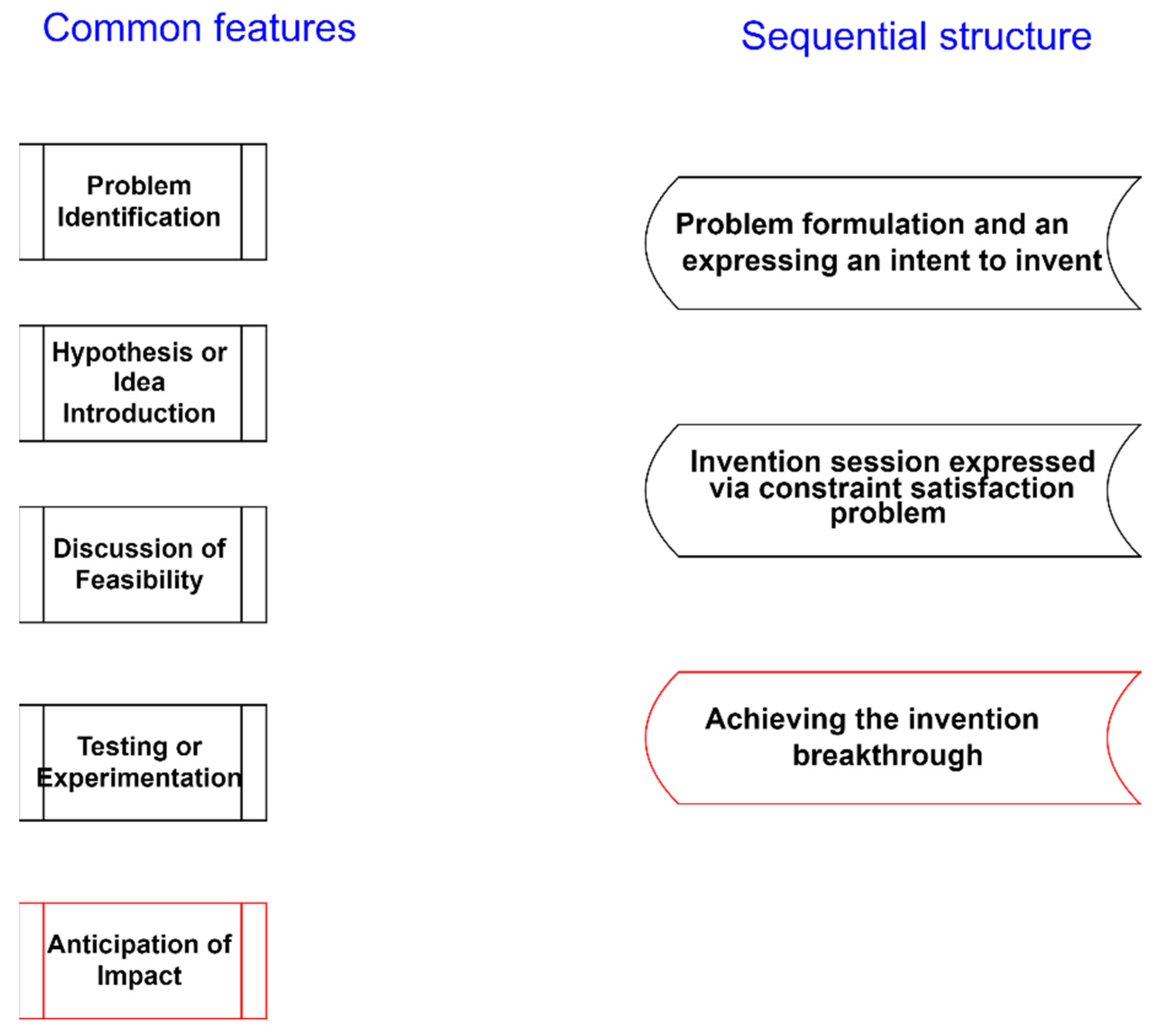

We visualize CSP as a state machine for jet engine invention dialogue (section 2.1) in

Figure 10.

In category theory, we can define a category of CSPs where:

Objects are CSP instances. Each CSP consists of variables, domains, and constraints.

Morphisms between CSPs are constraint satisfaction morphisms, which map one CSP to another in a structure-preserving way (preserving the relationships defined by the constraints).

For two CSPs, CSP1 and CSP2, a morphism f:CSP1→CSP2 might involve:

A mapping of variables in CSP1 to variables in CSP2.

A mapping of constraints in CSP1 to constraints in CSP2, ensuring that solutions are preserved between CSP1 and CSP2.

A functor is a structure-preserving map between categories. In the context of CSPs, a constraint satisfaction morphism functor could map from the category of CSPs (let’s call it C_CSP) to another category D which could be, for example, a category representing solution spaces, sets, or algebraic structures).

Formally, a functor F:C_CSP→D F: consists of:

Object Mapping: For each CSP A in C_CSP, the functor maps A to an object F(A) in D. For instance, F(A) might represent the solution space of A as a set.

Morphism Mapping: For each morphism f:A→B in C_CSP, the functor maps f to a morphism F(f):F(A)→F(B) in D. This morphism should preserve the structure induced by the CSP morphism f, meaning it should map solutions of A in a way that respects the constraints in B.

A few examples help illustrate different uses of constraint satisfaction morphism functors:

Solution Space Functor: A functor from CSP to the category of sets Set might map each CSP A to the set of its solutions. A morphism between CSPs then maps solution sets, preserving the structure of possible assignments that satisfy the constraints.

Algebraic CSP Functor: In algebraic CSPs, a functor might map CSPs to algebraic structures, such as groups or lattices, where solutions and constraints represent homomorphisms between different algebraic structures. This functor would help translate CSP problems into a form where algebraic tools can be applied.

Graph Representation Functor: If we represent CSPs as graphs where variables are nodes and constraints are edges, a functor could map CSPs to graph categories, translating CSP morphisms into graph homomorphisms. This allows graph-theoretic techniques to be used to analyze and solve CSPs.

To qualify as a functor, a constraint satisfaction morphism functor must satisfy two properties:

- 1)

Identity Preservation: The identity morphism in CSP for each CSP A (which maps A to itself) must map to an identity morphism in D.

- 2)

Composition Preservation: For any two composable morphisms f and g in CSP, the functor must map the composition g∘fg to F(g)∘F(f)F(g).

Constraint satisfaction morphism functors offer a formal way to translate CSP problems into other categories where different methods of analysis and solution can be applied. This approach is particularly useful in theoretical computer science and artificial intelligence, where many real-world problems can be formulated as CSPs, and mapping these problems into different structures can provide insights into their solvability, complexity, and solution spaces.

Invention Failure

Invention attempts can be successful or unsuccessful. We will now provide prompts and examples of successful and unsuccessful invention dialogues on the same topic.

Prompt:

Compose a dialogue between two inventors inventing a frame for a backpack to move it on a mountain trail. The dialogue starts with problem formulation, followed by a discussion on satisfying all invention constraints one by one, and concluding with invention description

ChatGPT:

Dialogue: Inventing a Backpack Frame for Mountain Trails

Inventor 1 (Alex): Alright, we’ve got a challenge: how do we design a backpack frame that can make carrying heavy loads on a mountain trail easier? Traditional backpacks work, but they put a lot of strain on the back and shoulders. Inventor 2 (Jordan): True. The key problem is balancing the weight efficiently while keeping mobility intact. What are the main constraints we need to address? Alex: Let’s break it down: |

Weight distribution — the load needs to be evenly spread to avoid strain.

Mobility — it must allow smooth movement, especially on uneven trails.

Stability — it should keep the load secure, no swaying or shifting.

Comfort — it needs to be ergonomic, with padding and proper ventilation.

Durability and weight — strong but lightweight materials are essential. |

Jordan: Great. For weight distribution, what if we create a frame that shifts the load to the hips instead of the shoulders? Alex: Yes! A rigid external frame that transfers the load to the hips via a padded belt could work. Maybe with adjustable straps to fine-tune the center of gravity. Jordan: Good. But we also need mobility. How do we ensure the wearer can bend, twist, and climb comfortably? Alex: Let’s make the frame articulated at key joints—around the shoulders and lower back—so it can flex with the body’s movements, almost like an exoskeleton. Jordan: Perfect! For stability, how do we keep the load from shifting as they move? Alex: Compression straps along the sides of the frame. They’ll hold the gear snugly and prevent any swaying. Maybe even some stabilizer fins that hug the body without restricting movement. Jordan: Smart. Now, comfort. What can we do to reduce pressure points and improve ventilation? Alex: Use mesh panels for airflow, combined with contoured foam padding on the hips and shoulders. And adjustable straps everywhere—custom fit is key. Invention Description: Alex: We’ve created a modular backpack frame designed specifically for mountain trails. It features a titanium external frame that transfers the load to the hips via a padded, adjustable belt. The frame is articulated at key joints, allowing full mobility while maintaining stability… |

Prompt: now convert this dialogue into an unsuccessful invention, which run against something which cannot be done

Dialogue: Inventing a Backpack Frame for Mountain Trails (Unsuccessful Attempt) Inventor 1 (Alex): We’ve got a tough challenge: designing a backpack frame that makes heavy loads easier to carry on a mountain trail. Traditional backpacks strain the back and shoulders—there has to be a better way. Inventor 2 (Jordan): Agreed. Let’s outline the main constraints: |

Alex: For weight distribution, what if we shift all the load to the legs instead of the shoulders? Jordan: To the legs? Hmm. Maybe we could create a frame that extends down to the thighs, kind of like an exoskeleton, transferring the weight directly to the legs. Alex: Exactly! The frame could bypass the upper body entirely and connect to some lightweight braces on the thighs. No more shoulder or back strain! Jordan: That sounds revolutionary. But how do we ensure mobility? Wouldn’t braces on the legs restrict movement? Alex: Good point, but we could make them flexible. Maybe they could hinge at the knees and swivel at the hips. That way, hikers can still bend and climb easily. Jordan: Interesting. But now for stability—how do we prevent the frame from shifting while the user moves? Alex: We could attach the frame tightly to the waist and thighs, with locking mechanisms that adjust to the user's leg movements. Jordan: I see the issue already. If the frame locks with the legs but still needs to move with them, we risk either limiting motion or causing chafing. And adding hinges increases complexity and failure points. Wouldn’t this frame make the user feel like they’re carrying a rigid cage? Alex: True, but maybe ultralight materials can fix that. What if we use carbon fiber braces? |

Conclusion: Unsuccessful Invention Jordan: We aimed to develop a frame that shifts weight to the legs, bypassing the back and shoulders, but the constraints of mobility, stability, and user fatigue make this approach unworkable. The complexity of hinging and locking mechanisms, combined with the increased strain on leg muscles, renders the idea both impractical and unsafe. |

4. Constraint Satisfaction for Invention Dialogues

4.1. Exploration-Exploitation

The “Exploitation vs. Exploration” discussion is simply a “new” fancy way of referring to a problem that is as old as making decisions about efficient resource allocation. It is a name that has been borrowed from probability theory, very likely via product management, data science, and financial services circles. (Rocca 2021) provides a comprehensive definition for both:

- 1)

Exploitation consists of taking the decision assumed to be optimal with respect to the data observed so far. This safe approach tries to avoid bad decisions as much as possible but also prevents from discovering potential better decisions.

- 2)

Exploration consists of not taking the decision that seems to be optimal, betting on the fact that observed data are not sufficient to truly identify the best option. This more risky approach can sometimes lead to poor decisions but also makes it possible to discover better ones, if there exist any.

The problem of choosing between exploitation and exploration can be encountered in many situations where observations drive decisions and decisions lead to new observations.

The idea of a constraint satisfaction exploration-exploitation functor combines concepts from constraint satisfaction, exploration-exploitation trade-offs (common in optimization and reinforcement learning), and category theory. In this framework, we aim to map CSPs to strategies for balancing exploration and exploitation in solution spaces. Such a functor would formalize the relationship between CSP structures and the decision-making process for exploring new solutions versus exploiting known good ones.

Exploration CSP refers to searching or navigating through the solution space of a CSP to discover possible solutions. It is often associated with techniques like brute-force search, backtracking, or random sampling, where the focus is on exploring the entire or a large part of the solution space without necessarily favoring the best solutions. Searching through less-visited regions of the solution space to discover new solutions. In CSPs, this might involve testing variable assignments that have not been thoroughly examined, even if they have uncertain outcomes

Exploitation CSP refers to using prior knowledge or feedback to focus on the most promising areas of the solution space. This is often associated with more targeted search methods like hill-climbing, simulated annealing, or greedy algorithms, where the search is steered toward areas that are expected to yield good solutions based on past performance. Focusing on promising regions of the solution space that are known to produce feasible or optimal solutions, refining known assignments to maximize satisfaction or optimize a criterion.

CSP consists of variables with domains, constraints that restrict combinations of variable values, solutions are assignments of values to variables that satisfy all constraints. Categories of CSPs are as follows:

- 1)

Objects are CSPs, each representing a different problem instance.

- 2)

Morphisms are mappings between CSPs that preserve constraint structures, as in typical CSP morphisms. These could translate to transformations between problem instances where similar solutions or solving techniques can apply.

An exploration-exploitation functor is a mapping from the category of CSPs to a category of decision processes or strategies that captures both exploration and exploitation strategies for solving CSPs. Formally, a functor F:CSP→Strategy would map each CSP instance A to an object F(A) in a category Strategy, where F(A) represents a specific strategy or decision-making process for solving A using exploration-exploitation techniques. Similarly, a CSP morphism f:A→B maps to a morphism F(f):F(A)→F(B) in Strategy, which translates strategies between CSPs.

Components of the Exploration-Exploitation Functor are:

- 1)

Object Mapping: For each CSP AAA, the functor maps it to a specific exploration-exploitation strategy F(A) in Strategy. For example, F(A) could represent a probabilistic strategy that starts by exploring a broad range of assignments, then shifts toward exploitation as high-satisfaction solutions are identified.

- 2)

Morphism Mapping: For each morphism f:A→B between CSPs, F(f) translates an exploration-exploitation strategy for A into a compatible strategy for B. This morphism mapping might involve adjustments in the balance between exploration and exploitation, based on similarities in the structure of A and B. For example, if B is known to be a stricter version of A, F(f) might favor exploitation strategies focused on tightening known solutions.

Example Scenarios for the Exploration-Exploitation Functor are:

- 1)

Adaptive CSP Solvers: Suppose strategy Strategy represents a category of CSP solvers that adaptively balance exploration and exploitation. Given a CSP instance A, the exploration-exploitation functor could map it to a solver that initially explores diverse variable assignments to cover the search space and gradually converges on refined solutions.

- 2)

Probabilistic Solution Methods: If Strategy includes probabilistic strategies, such as simulated annealing or genetic algorithms, the functor could map CSPs to such methods, tuning exploration and exploitation parameters based on the problem’s complexity and constraint density. A morphism between CSPs could adjust these parameters to reflect the nature of constraints in the target problem.

- 3)

Transfer Learning for CSPs: In machine learning contexts, this functor could formalize a transfer-learning approach for CSPs by mapping a known strategy for a source CSP A to a new CSP B. For instance, if A and B share structural similarities, F(f) could favor exploitation based on known solutions from A when applied to B, reducing redundant exploration.

The exploration-exploitation functor is useful for building generalized, adaptable solvers for CSPs. By formalizing strategies that dynamically balance exploration and exploitation, this functor can improve efficiency in finding solutions, especially for large or complex CSPs, enable the reuse of problem-solving strategies across related CSPs, and guide automated reasoning about when to explore new solutions versus refining known ones.

Hence, an exploration-exploitation functor in the context of CSPs leverages category theory to formalize a decision-making strategy for balancing between discovering new solutions and optimizing known ones, enabling more efficient and adaptive approaches to solving constraint satisfaction problems.

4.2. Functors Representing Exploration and Exploitation

A functor from the category of CSPs to another category can model different types of exploration and exploitation strategies, each representing a different way of mapping a CSP into another structure, possibly with the aim of solving it.

Our first example is Exploration functor for Random Walks. In this case, we might define a functor that models an exploration strategy through random walks or stochastic search techniques.

- 1)

Category: {CSP}(category of CSPs) → {Graph}(category of graphs).

- 2)

Object Mapping: Each CSP is mapped to a search tree or state space graph. Each variable in the CSP corresponds to a node, and the constraints define the edges between nodes (possible assignments to variables that respect constraints).

- 3)

Morphisms: A CSP morphism f between two CSPs is mapped to a graph traversal or a random walk between the two graphs, where the search space is explored non-deterministically.

In this setting, the functor represents an exploration strategy where the solution space is explored via random decisions, and each step in the exploration corresponds to a state transition in the graph.

In Exploitation Functor - Greedy Algorithm, a functor could represent an exploitation strategy, like a greedy algorithm, where the CSP is mapped to a solution space that is explored in a way that always seeks the most optimal solution at each step:

- 1)

Category: {CSP} → {Set} (category of sets, where solutions are considered as sets).

- 2)

Object Mapping: Each CSP is mapped to the set of variables and their domains, along with the partial assignments that are currently being considered. A CSP might be translated into a set of possible configurations or partial assignments, from which the best configuration is chosen at each step.

- 3)

Morphisms: A morphism f between two CSPs might be mapped to a greedy selection function, which maps partial assignments or variable assignments to the most promising candidates according to some evaluation function (such as minimizing conflicts or cost).

In this case, the functor corresponds to an exploitation strategy where the solver chooses the "best" solution at each step based on the evaluation function, focusing the search on high-value areas of the solution space.

We proceed to an example of Exploration-Exploitation Balance Functor - Multi-Armed Bandit. A more sophisticated functor could model the balance between exploration and exploitation, much like in the multi-armed bandit problem from reinforcement learning. The Multi-Armed Bandit problem is a classic problem in probability theory and decision-making that captures the essence of balancing exploration and exploitation. This problem is named after the scenario of a gambler facing multiple slot machines (bandits) and needing to determine which machine to play to maximize their rewards. The problem has significant applications in various fields, including online advertising, clinical trials, adaptive routing in networks, and more. The goal is to explore new strategies (new parts of the solution space) while also exploiting known strategies that have worked well in the past.

- 1)

Category: {CSP} → {Probabilistic}(category of probabilistic processes, e.g., Markov decision processes or reinforcement learning environments).

- 2)

Object Mapping: Each CSP is mapped to a probabilistic model of solutions, where each possible solution or partial solution is associated with a probability or expected value. The CSP is seen as a decision problem where different solution paths are taken probabilistically, with some paths explored more thoroughly and others based on previous experience.

- 3)

Morphisms: A morphism f between two CSPs could be represented as a probabilistic policy that decides whether to explore (search in a new area) or exploit (focus on previously successful solutions), potentially adjusting the balance over time.

In this case, the functor represents a strategy that adapts to the problem by both exploring new solutions and exploiting promising solutions from previous experience. This is similar to how algorithms like ε-greedy or Upper Confidence Bound work in the context of the multi-armed bandit problem.

Applications in CSP Solvers include Exploration-Exploitation Functors in Search Algorithm. These functors are useful in CSP solvers that combine global search (exploration) with local search (exploitation). For instance, algorithms like Genetic Algorithms or Simulated Annealing may explore the search space randomly at first (exploration) and then focus the search in promising regions as it converges to a solution (exploitation). A functor can formalize this shifting behavior within a category-theoretic framework.

Also, they can be applied to AI and Reinforcement Learning. In AI, especially reinforcement learning, exploration-exploitation trade-offs are crucial. Functors can model how an agent explores different solutions to a CSP and then exploits the best solutions as it gains more experience or feedback from previous actions.

In the context of CSPs, functors modeling exploration and exploitation strategies offer a way to formalize how CSP solvers navigate the solution space. Functors can map CSPs to different categories representing various search strategies (e.g., random walks for exploration, greedy algorithms for exploitation), and by doing so, they provide a structured framework for understanding the relationship between problem-solving techniques and their theoretical foundations.

4.3. Hypergraph Representation for CSP

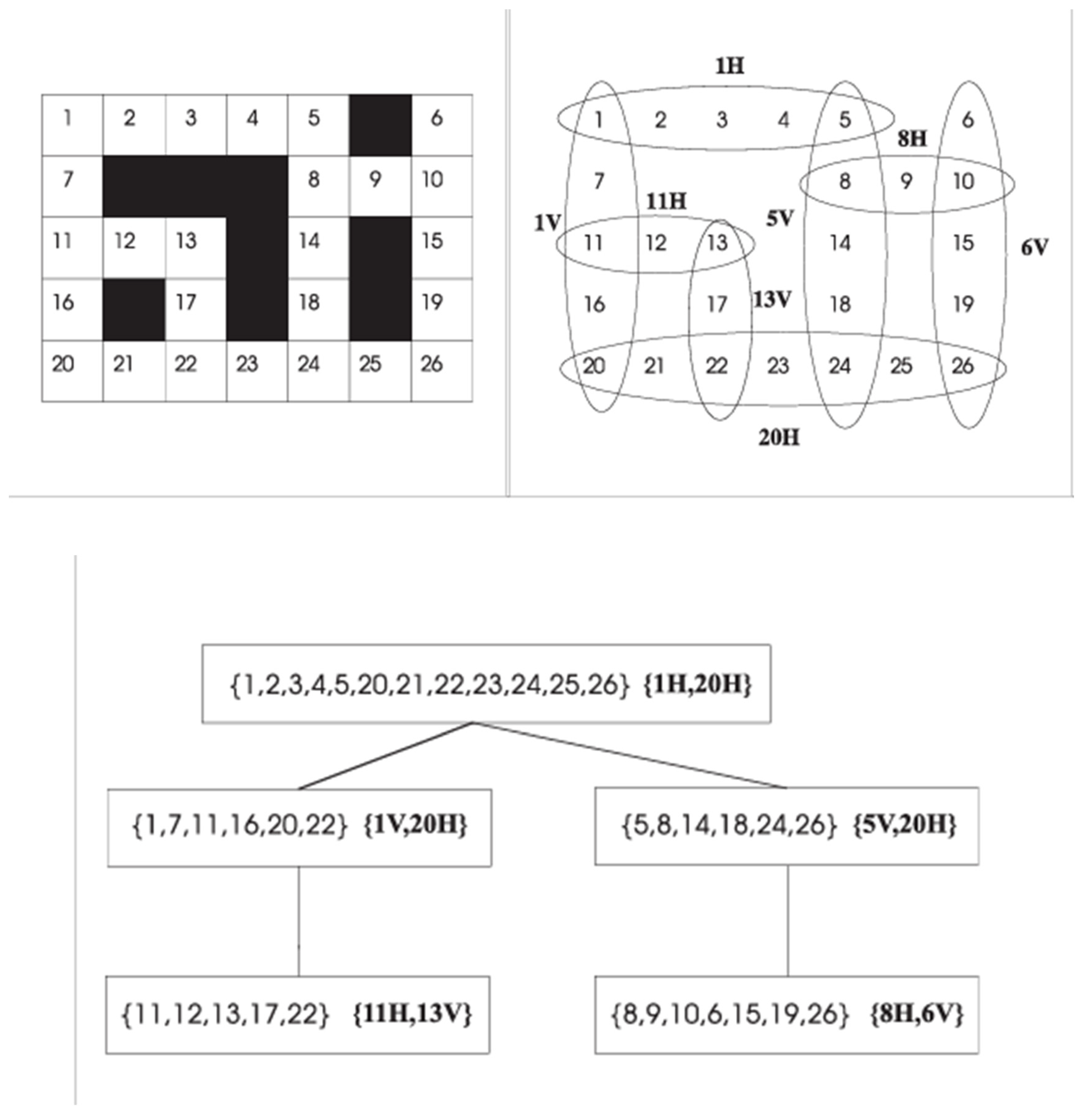

A crossword can be viewed as a partial case of invention. In the course of a dialogue, participants suggest solution words which might fit the crossword instantly, but rejected later, never fit or fit and remain. A crossword puzzle can be formulated as a CSP and then be represented as hypertree decomposition.

Figure 11 shows a combinatorial crossword puzzle. A set of English words is associated with each horizontal or vertical array of white boxes separated by black boxes. A successful solution to the puzzle problem, which we view as an invention, is an assignment of a character to each white box such that to each white array is assigned a word from its set of English words. This problem can be reduced to a CSP by assigning a CSP variable to each white box, and by defining a constraint for each array of white boxes prescribing the existing English words that are mapped into it.

Solving a crossword in the course of a dialogue can be viewed as an invention process. A combinatorial crossword puzzle is a typical CSP (Dechter 1992). A set of legal words is associated to each horizontal or vertical array of white boxes delimited by black boxes. A solution to the puzzle is an assignment of a letter to each white box such that to each white array is assigned a word from its set of legal words. This problem is represented as follows.

There is a variable Xi for each white box, and a constraint C for each array D of white boxes. (For simplicity, we just write the index i for variable Xi.) The scope of C is the list of variables corresponding to the white boxes of the sequence D; the relation of C contains the legal words for D.

Structural decomposition methods are considered in (Gottlob et al 2000), which identify tractable classes by exploiting the structure of constraint scopes as it can be formalized as a hypergraph whose nodes correspond to the variables and where each group of variables occurring in some constraint induce a hyperedge. A hypergraph can be defined as a generalization of a graph where edges, called hyperedges, can connect any number of nodes, not just two. Structural methods based on the notions of generalized hypertree width and treewidth turn out to be efficient (Robertson and Seymour 1984). Gottlob et al (2012) suggests a primal graph representation, where nodes correspond to variables and an edge between two variables indicates that they are related by some constraint.

The underlying idea is that solutions to CSP instances that are associated with acyclic (or nearly-acyclic) structures can efficiently be computed via dynamic programming, by incrementally processing the structure according to some of its topological orderings.

An instance of a constraint satisfaction problem for an invention is a triple I = <Var,U,C> , where Var is a finite set of variables, U is a finite domain of values, and C = {C1,C2,...,Cq} is a finite set of constraints. Each constraint Cv, for 1 ≤ v ≤ q, is a pair (Sv,rv), where Sv ⊆ Var is a set of variables called the invention scope, and rv is a set of substitutions (also called tuples) from variables in Sv to values in U indicating the allowed combinations of simultaneous values for the variables in Sv. Any substitution from a set of variables V ⊆ Var to U is extensively denoted as the set of pairs of the form X/u, where u ∈ U is the value to which X ∈ V is mapped. Then, a solution to I is a substitution θ: Var → U for which q-tuples tq ∈ r1,...,t1 ∈ rq exist such that θ = t1 ∪ ... ∪ tq.

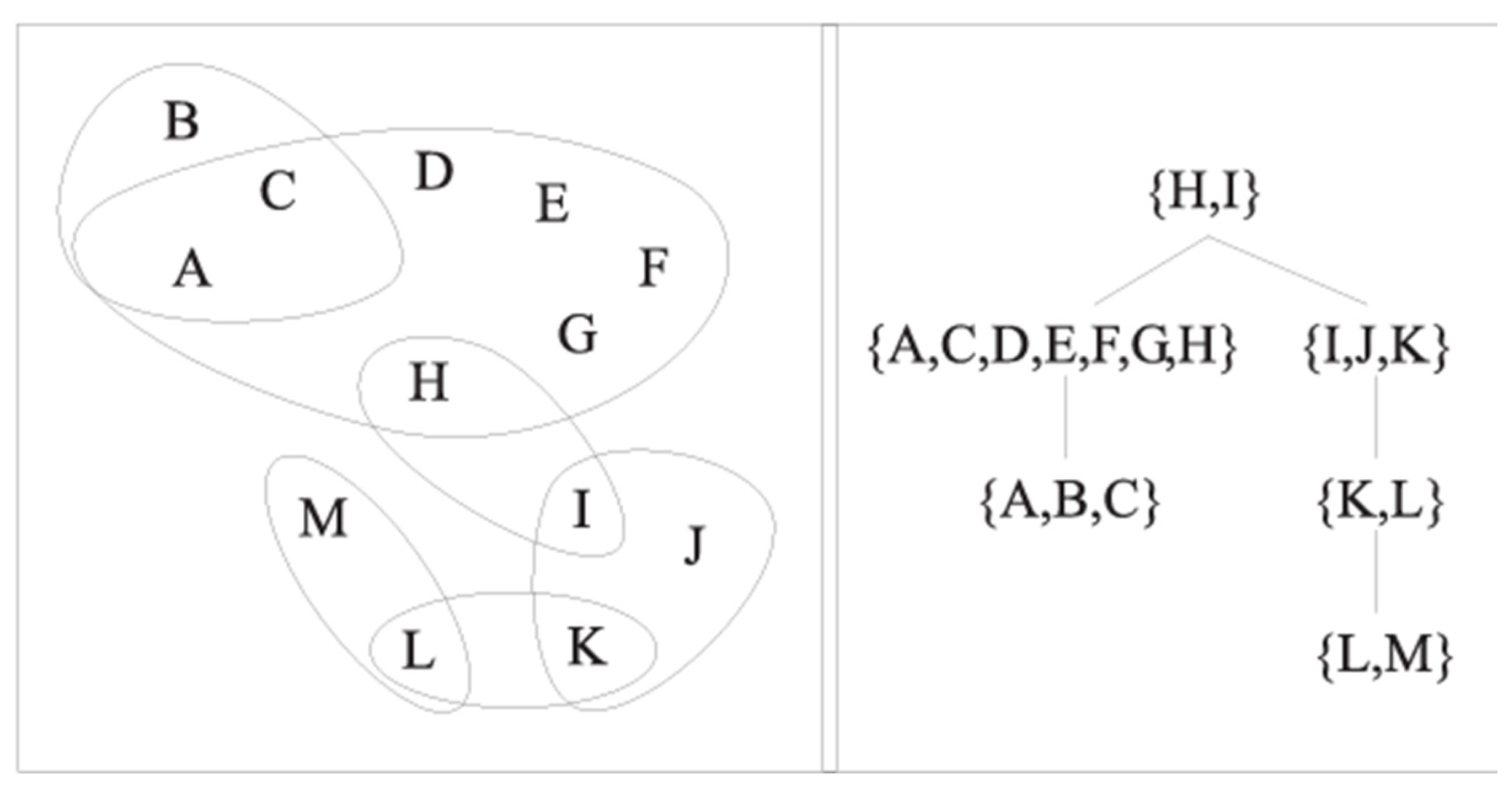

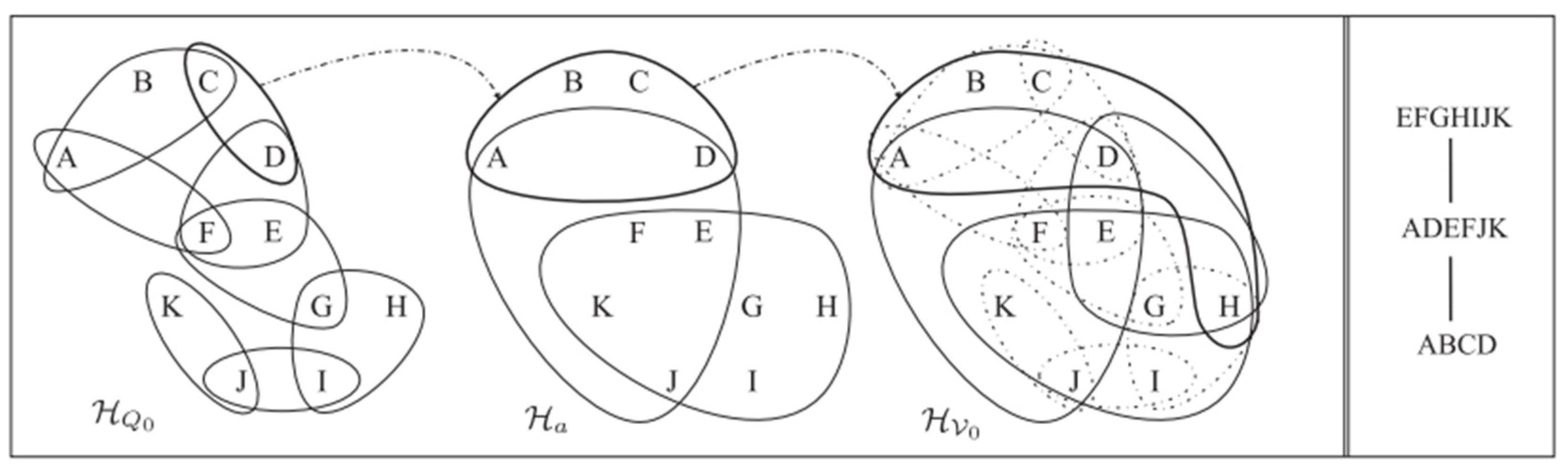

We now proceed to the example of representation for invention entities

H (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13). In the hypergraph

H shown on the left , which is associated with a CSP formulation for an invention problem over the set of variables

{A,B...}. A few constraints are defined over the instance whose scopes precisely correspond to the hyperedges in

E(H); for instance,

{A,B,C} is an example of constraint scope.

H is acyclic: a join tree

JT(H) for it is depicted on the right.

The structure of a CSP instance I is best represented by its associated hypergraph H(I) = (V,H), where V = Var and H = {S | (S,r) ∈ C}. A hypergraph H is acyclic iff it has a join tree. A join tree is a tree structure that captures relationships between hyperedges in the hypergraph. For a hypergraph H to be acyclic, it must have a join tree satisfying the running intersection property: For any two hyperedges connected through a path in the join tree, their intersection (shared variables) must also appear in all hyperedges along that path.

This ensures that constraints can be processed in a tree-like order, simplifying constraint propagation and search algorithms. A join tree imposes an order where constraints can be checked locally while ensuring global consistency through propagation. Since trees have no cycles, processing constraints in this order avoids revisiting variables unnecessarily. The existence of a join tree guarantees that the CSP can be solved using polynomial-time algorithms such as tree decomposition or join-tree clustering.

A join tree

JT(

H) for a hypergraph

H is a tree whose vertices are the hyperedges of

H such that, whenever the same node

X ∈

V occurs in two hyperedges

h1 and

h2 of

H, then

X occurs in each vertex on the unique path linking

h1 and

h2 in

JT(

H) (

Figure 13). The notion of acyclicity we use here is the most general one known in the literature, coinciding with α-acyclicity. α-acyclicity is a concept introduced by Fagin(1983), related to hypergraphs and database theory. It extends the notion of acyclicity to hypergraphs, which are widely used in CSPs and relational databases.

4.4. Hypergraph Solvers

Once a CSP problem is expressed as a finite set of constraints, the goal is to find the variables' values satisfying them. Even though the problem is in general NP-complete, there are some approximation and ractical techniques to tackle its intractability. One of the most widely used techniques is the Constraint Propagation. It consists in explicitly excluding values or combination of values for some variables whenever they make a given subset of constraints unsatisfied. Oucheikh et al (2019) define a CSP subclass called 4-CSP whose constraint network infers relations of the form: {x∼α, x−y∼β, (x−y)−(z−t)∼λ}, where x, y, z, and t are real variables, α,β and λ are real constants and ∼∈{≤,≥}. The authors provide a graph-based proofs of the 4-CSP tractability and elaborates algorithms for 4-CSP resolution based on the positive linear dependence theory, the hypergraph closure and the constraint propagation technique. Time and space complexities of the resolution algorithms are proved to be polynomial.

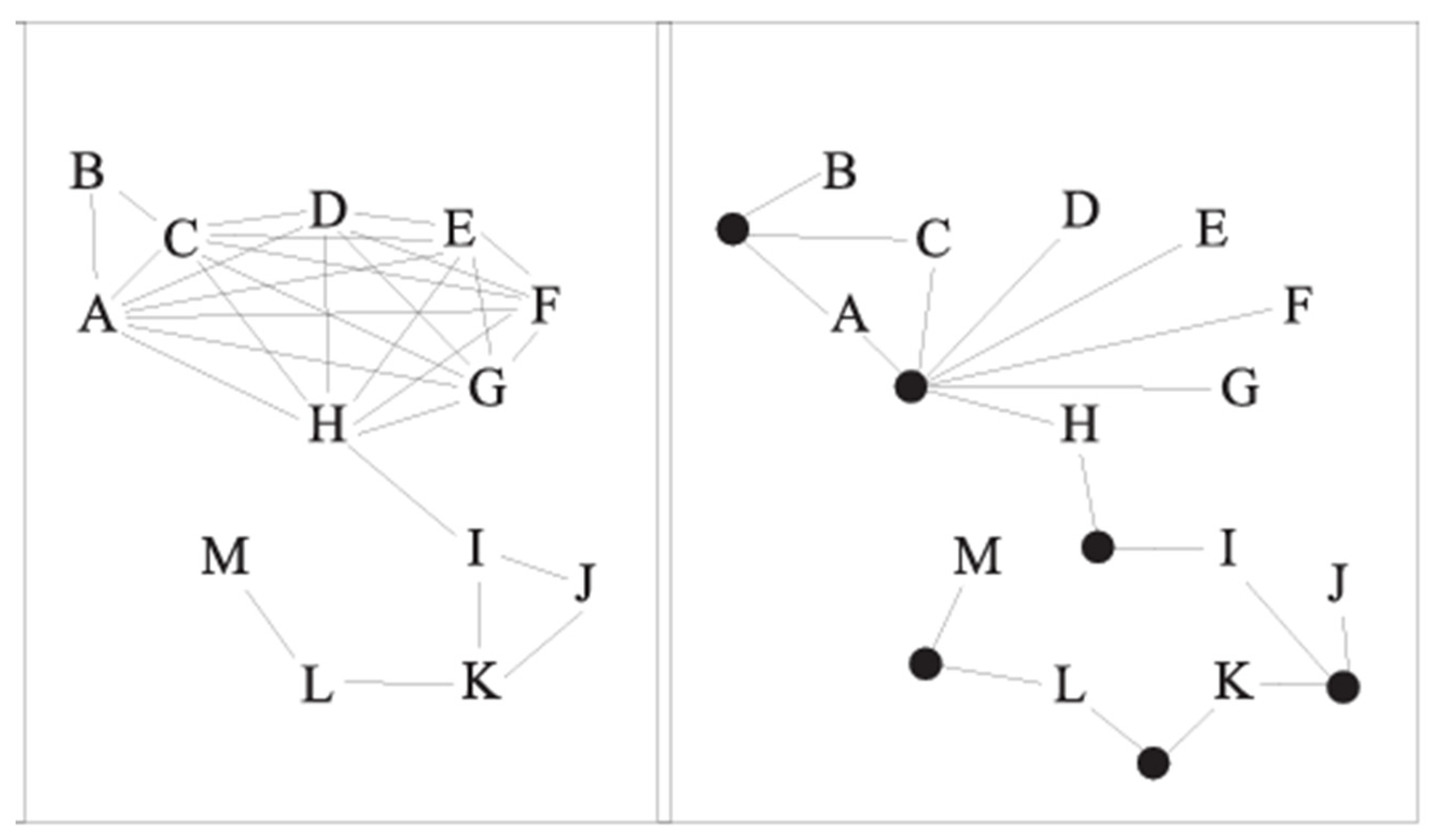

The invention process in the form of Four Phase Handshake Protocol (Blunno et al 2004) depicted in

Figure 14 on the bottom. This protocol uses two clocks

x1, x2, two parameters

minIO, maxIO, and the following constraints:

x1 <

maxIO,

x1 >

inIO,

x2 <

maxIO,

x2 >

inIO, and

x1 – x2 ≤

maxIO − minIO. Implementing the protocol can be reduced to its 4-CSP equivalent.

The de-synchronization model presented in this section aims at the substitution of the global clock by a set of asynchronous controllers that guarantee an equivalent behavior. The model assumes that the circuit has combinational blocks (CL) and registers implemented with D flip-flops (FF), all of them working with the same clock edge (e.g. rising in

Figure 14). The de-synchronization method proceeds in three steps:

- 1)

Conversion of the flip-flop-based synchronous circuit into a latch-based one (M and S latches). D-flip-flops are conceptually composed of master-slave latches.

- 2)

Generation of matched delays for the combinational logic (denoted by rounded rectangles). Each matched delay must be greater than or equal to the delay of the critical path of the corresponding combinational block. Each matched delay serves as a completion detector for the corresponding combinational block.

- 3)

Implementation of the local controllers.

Structural decomposition methods, as developed by Greco and Scarcello (2016), are designed to identify tractable classes of Constraint Satisfaction Problems (CSPs) by leveraging the hypergraph structure of problem instances. These methods transform cyclic hypergraphs into acyclic ones by grouping their edges (or nodes) into a polynomial number of clusters and arranging these clusters into a hierarchical structure known as a decomposition tree. Using this decomposition tree—or simply knowing that such a tree exists—enables the problem instance to be solved in polynomial time.

Inventions can also be modeled as conjunctive queries, where evaluating these queries is generally NP-hard. However, it becomes computationally feasible in polynomial time for the class of acyclic queries (Q). Each query Q is associated with an acyclic query hypergraph HQ, where the nodes represent the variables of Q and the hyperedges correspond to the sets of variables occurring in its atoms.

To handle cyclic hypergraphs, methods exist to transform them into acyclic ones. This transformation involves grouping edges (or nodes) into polynomially bounded clusters and arranging them into a decomposition tree. The original problem can then be evaluated by processing the subproblems represented in this tree. The computational cost depends on the width of the decomposition, which is the size of the largest cluster. The process is polynomial if this width is bounded by a constant and exponential otherwise.

The notion tree projection is an efficient decomposition method, where a query

Q is given together with a set

V of atoms, called views, which are defined over the variables in

Q (Greco and Scarcello 2016). The question is whether (parts of) the views can be arranged as to form a tree projection (playing the role of a decomposition tree), i.e., a novel acyclic query that still subsumes

Q. By representing

Q and

V via the hypergraphs

HQ and

HV, where hyperedges one-to-one correspond with query atoms and views, respectively, the tree projection problem reveals its graph-theoretic nature. For a pair of hypergraphs

H1, H2, let

H1 ≤

H2 denote that each hyperedge of

H1 is contained in some hyperedge of

H2. Then, a tree projection of

HQ w.r.t.

HV is any acyclic hypergraph

Ha such that

HQ ≤

Ha ≤

HV . If such a hypergraph exists, then we say that the pair of hypergraphs (

HQ, HV) has a tree projection (

Figure 15).

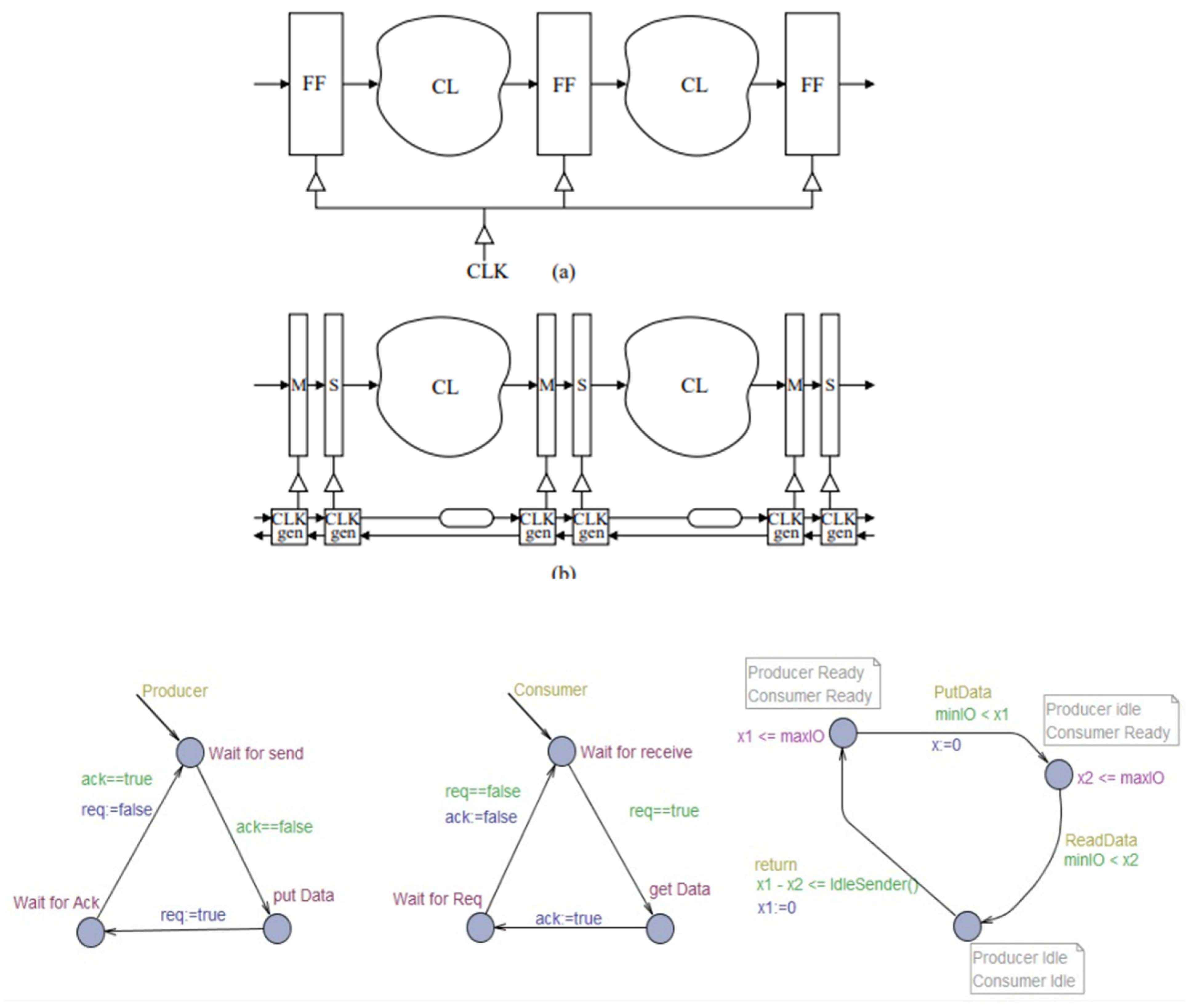

4.5. Game-Theoretic Interpretation of Invention Dialogues

The invention proponent and opponent dialogue game is played on a pair of hypergraphs (H1, H2) by two main agents (proponent and opponent) where the proponent controlling her servant agents, in charge of the “surveillance” of a number of strategic invention possibilities. The objective for the proponent of this invention is to catch any possibility of invention failure, expressed by the opponent.

The dialogue is driven by the moves of the proponent with her agents and of the opponent. The opponent stands on a node and can run at great speed along the edges of

H1. However, she is not permitted to run through a node that is controlled by a servant agent. Each move of the proponent involves one squad of service agents, which is encoded as a hyperedge

h ∈

edges(

H2). The proponent may ask some agents in the squad

h to run in action, as long as they occupy nodes that are currently reachable by the opponent, thereby blocking an escape path for the opponent. Thus, “second-lines” agent cannot be activated by the invention proponent. Note that the invention opponent is fast and may see agent that are entering in action. Therefore, while agents move, the opponent may run through those positions that are left by agents or not yet occupied. The goal of the proponent is to place an agent on the node occupied by the opponent, while the robber tries to avoid her/his capture in the form of finding a flaw in this invention (

Figure 16).

This setting follows the Robber and Captain game (Bonato and Nowakowski 2010) which is a combinatorial game used to analyze CSPs through their hypergraph structures. It is particularly useful for studying treewidth, hypertree decompositions, and the tractability of CSP instances. The minimum number of proponent’s agents required to block the opponent directly relates to the treewidth (or hypertree width) of the graph. Treewidth ≤ k if k + 1 agents can capture the opponent. This property determines whether the CSP can be solved efficiently in polynomial time. CSP instances with low treewidth are computationally tractable because they can be decomposed into tree-like structures (e.g., decomposition trees). Higher treewidth values indicate cyclic dependencies, making the problem potentially NP-hard.

5. Evaluation

5.1. Evaluation Domains

We experiment with a broad range of domains where inventions are made (

Table 1).

5.2. CSP Tools

We suggest AI Space CSP tool (O’Neil et al 2024) to solve CSP in a consistency-based manner arising in invention dialogue. Tutorials include creating a CSP , giving information about how to create a new CSP from scratch, loading a preexisting CSP, covering how to load one of the ready-made CSPs and giving a brief description of each of them. Moreover, there is solving a CSP tutorial that covers how to solve a CSP, and includes domain splitting and backtracking.

CSP solvers find solutions to CSPs, where the most complex algorithms build on simpler ones; but a common thread throughout all CSP solvers is that they iteratively check potential solutions or partial solutions against the constraints. Wong at al (2024) build recursive backtracking and forward checking algorithms for CSPs. In recursive backtracking, progressive partial solutions are recursively explored, with backtracking occurring when there is no possibly path forward due to the constraints.

A pseudocode for the backtracking algorithm to solve invention dialogues is shown below for the case of a grid of entities forming an invention:

function backtrack(grid, col):

for 1 <= i <= row.length:

Add a new invention entity at (row, column) = (i, col)

Check constraints

if constraints fail:

if i == row.length:

Return false;//could not find a solution for this column

Keep going

else:

backtrack(grid, col + 1) |

Another way of solving a CSP is to use the method of forward checking. In forward checking, the possibilities for each node in the graph (in this case, for each state) are tracked.

We compare default prompt for dialogue construction with category theory based, where categorial model is enforced. One terminates a search path if there are no legal values possible for the node being considered.

function forwardCheck(map):

for each entities in map:

entities.optionsSet = list of all invention entities(…);

forwardCheckPartner({}, map);

function forwardCheckPartner(labelAssignment, CSP):

if all entities have labels:

return labelAssignment

select randomly assigned state from CSP

for each entity in entities.optionsSet:

if entity is not the same as any terminal label entity

add entity and label to labelAssignment

for each terminalLabel:

remove option from terminalLabel.optionSet

forwardCheckPartner(labelAssignment, CSP)

if labelAssingment works:

return labelAssignment

remove entity and label from labelAssignment

for each terminalLabel:

add option to terminalLable.optionSet

return failure |

An Arc Consistency CSP Solver is an algorithm designed to enforce arc consistency in CSPs. It focuses on reducing the domain of variables by eliminating values that cannot satisfy the binary constraints between pairs of variables, ensuring that every remaining value is consistent with the constraints. Arc Consistency includes:

A binary constraint between two variables X and Y forms an arc denoted as (X,Y).

A variable X is arc consistent with Y if, for every value in DX (domain of X), there exists at least one value in DY such that the constraint between X and Y is satisfied.

If no such value exists, the inconsistent value is removed from DX .

The algorithm processes the CSP by iteratively checking and enforcing arc consistency. The most common algorithm start with a queue containing all arcs(X,Y).

Output is a reduced domain for variables, ensuring consistency. The CSP might still need backtracking search if no full assignment is possible.

5.3. CSP-Based Dialogue Construction

We evaluate a direct construction vs CSP-supported construction of an invention dialogue, as well as the contribution of our categorial model. Human experts evaluate the correctness of inventive dialogues constructed by ChatGPT with different prompts:

- 1)

Construct an inventive dialogue for <device>

- 2)

Construct the inventive dialogue for <device> where components include <components in section ..> where entities obey constraints from <section …> and categorial constraints from section …> are satisfied

- 3)

Construct the CSP expressed by a logic program and an invention dialogue based on this resolved CSP where entities obey constraints (2). Then resolve the constructed CSP by a CSP solver from section 5.2 and use ChatGPT to verify the consistency, given the resolved CSP.

The consistency and correctness results for these three scenarios are shown in

Table 2. We used 100 devices from the list of domains in section 5.1.

We observe a systematic improvement in generated invention dialogues once we add the dialogue model (column 3) and then explicit CSP resolution (column 4). These improvements are 3.3% and 5.3% respectively, confirming the importance of CSP solver in a specific sense and a logical reasoning companion in a broader sense for improving LLM results.

5.4. Pedagogical Value

We assess the pedagogical value of representing invention in the form of dialogue. We assess the following features of dialogue-based inventions vs plain text or math-based exploration of new topics.

We compare conventional format of learning plain text + supportive media versus inventive dialogue format + supportive media. As inventive dialogues encourage step-by-step learning of a concept being invented, it is expected to help students memorize all required intermediate concepts that led to invention (column 2). Evaluation questions are focused on sequences of involved concepts.

Inventive dialogues also promote critical thinking. Dialogues introduce contrasting viewpoints, pushing learners to evaluate and synthesize ideas (column 3). Moreover, they encourage learners to think hypothetically: how an invention might impact society or solve specific problems (column 4). Evaluation questions are focused on societal impact.

There is a memorizing impact on learners: dialogues mimic storytelling, which is easier to remember than abstract descriptions. Also, learners are emotionally invested in character interactions, improving memory retention (column 5). Evaluation questions are focused on details of inventions, specific details of a concept.

We evaluate the quality of acquired knowledge by asking students to answer questions about the topic unrelated to inventive dialogue but important for understanding the phenomenon being learned. These questions are automatically generated from textbooks (and not from dialogue texts), relying on simple question generation prompts.

In

Table 3 we assess an improvement or decline in measured knowledge and skills by student in the specific knowledge domain, as estimated by answering questions. The value in each cell is a proportion of questions correctly answered by a student trained by inventive dialogue relative to the ones trained by traditional textbooks. For this evaluation task, six students used 234 text – invention dialogue pairs to learn from and attempt to answer questions. All invention dialogues and questions were generated by ChatGPT. An assessment of correct/incorrect answers to questions was conducted by ChatGPT as well.

One can observe that the best impact of learning from invention dialogues is made in case of Step-by-step learning of a concept, followed by Thinking hypothetically. In Healthcare domain the value of learning from invention dialogues is greatest, followed by Communication & Computing. Whereas in some domain and kinds of knowledge invention dialogues can deteriorate learning outcomes, the overall assessment show the improved learning efficiency.

5.5. Manual Construction of Invention Dialogues

We proceed to an assessment task on manual construction of invention dialogues, based on a description of a phenomenon in health, engineering or computing. Dialogues manually constructed by students from the previous evaluation settings for the same topics. The dialogues written by students were compared with the above 234 invention dialogues. We count the portion of invention dialogues written as well as ChatGPT with respect to consistency, originality, and plausibility in

Table 4.

We conclude from this evaluation that once the students learn new technical achievements from hypothetical invention dialogues and answer questions about what they have learned, they can successfully construct such invention dialogues in about ¾ of cases. Plausibility turns out to be most successfully achieved feature, followed by originality and then consistency.

6. Discussions and Conclusions

In conclusion, we share a hypothetical dialogue between Thomas Edison and his collaborators.

Thomas Edison, renowned for his prolific inventions, often collaborated with a team of skilled assistants and co-inventors. While direct transcripts of their dialogues are scarce, historical accounts provide insights into their collaborative processes (

Figure 17).

Charles Batchelor, a British engineer, was one of Edison's closest associates. Their partnership was instrumental in developing the incandescent light bulb. Batchelor's technical expertise complemented Edison's inventive vision. Their interactions likely involved detailed discussions on filament materials, vacuum techniques, and design improvements.

Francis Upton, a mathematician and physicist, joined Edison's team to work on the electric light and power system. Upton's analytical skills were crucial in solving complex problems related to electrical distribution. Their conversations would have encompassed mathematical analyses, experimental results, and system optimization strategies.

Edison's Menlo Park laboratory was a hub of innovation, housing a diverse team of talented individuals. The collaborative environment fostered open communication, brainstorming sessions, and collective problem-solving. While specific dialogues are undocumented, the team's synergy was evident in the rapid development of groundbreaking technologies.

Edison was known for his hands-on approach and often engaged in direct communication with his team. He encouraged experimentation and valued practical results. His leadership likely involved motivational discussions, critical evaluations of ideas, and guidance on experimental methodologies.

Although verbatim records of Edison's dialogues with his co-inventors are limited, the collaborative essence of their interactions is well-documented. Their collective efforts led to innovations that have profoundly impacted modern society. Edison's approach—blending invention, entrepreneurship, and aggressive marketing—set a model for modern inventors and tech entrepreneurs. His success illustrates the importance of securing funding, demonstrating commercial value, and building networks to transform ideas into profitable ventures (

Figure 18).

Several studies on converting text into dialogue format preceded the development of invention dialogue systems. Galitsky et al. (2019) introduced a chatbot capable of delivering content as virtual dialogues, which are automatically generated from plain texts extracted and selected from documents. These virtual dialogues consist of answers derived from identified and segmented document fragments, paired with questions that are automatically generated based on the initial text. Building on this approach, Galitsky (2021) proposed the Doc2Dialogue algorithm, which transforms paragraphs of text into hypothetical dialogues by analyzing their discourse trees. This method enables a significant expansion of chatbot training datasets across diverse domains.

Another method for building dialogues involves detecting rhetorical agreement between texts (Galitsky, 2022). This approach utilizes a rhetorical agreement application that processes a multi-part initial query based on the topic of the intended dialogue. It generates a question communicative discourse tree, which represents the rhetorical relationships between fragments of the query. The algorithm then identifies a sub-discourse tree within the question communicative discourse tree. Next, the algorithm generates a candidate answer communicative discourse tree for each potential answer in each set. It evaluates the level of complementarity between the sub-discourse tree and each candidate answer discourse tree by applying a classification model to both structures. Based on the computed complementarity, the application selects the most appropriate answer from the candidates, thereby constructing a dialogue structure for an interactive session.

An invention can streamline bureaucracy by automating repetitive tasks, improving data management, and enhancing communication systems, thereby reducing paperwork, delays, and human errors (Galitsky 2021). Technologies such as workflow automation software, artificial intelligence-driven decision-making tools, and digital document management systems can simplify processes like approvals, record-keeping, and compliance monitoring. By enabling faster processing, better tracking, and secure storage of information, inventions can increase transparency, accountability, and efficiency within bureaucratic systems, ultimately saving time and resources while improving public service delivery (

Figure 19).

Galitsky (2025) investigates CSP for scheduling and resource allocation in healthcare environments. The study begins with fundamental scheduling tasks for nurses and physicians and gradually addresses more complex scenarios where single-shot solutions prove inadequate. The author further examines the role of LLMs in facilitating schedule construction by converting natural language constraints into formats compatible with CSP algorithms. The chapter concludes with an in-depth analysis of temporal CSP techniques.

In a common dialogue, such as customer support or patient-doctor, the dialogue structure can be pre-defined by the initial conversation and problem formulation (Galitsky 2022). This dialogue structure is encoded in the form of discourse tree, a means to represent an overall high level logical organization of a dialogue. Such a dialogue structure determinism can also hold for an invention dialogue, where problem formulation may suffice for the CSP resolution scenario and the whole dialogue structure is determined by problem formulation utterances.

Mahadevan (2022) presents a unified formalism for structure discovery of causal models such as invention dialogues (caused by initial dialogue utterances) and predictive state representation models in reinforcement learning using higher-order category theory. The author describes structure discovery in both settings using simplicial objects, contravariant functors from the category of ordinal numbers into any category. A simplicial object in a category C is a structure that captures the idea of objects organized in a way analogous to simplices in geometry (points, line segments, triangles, etc.). These structures are defined via functors from the simplicial category Δ to C. A contravariant functor is a mapping between categories that reverses the direction of morphisms.

We conclude with the dialogue related to the invention for an automatic shaving (

Figure 20):

Marketing: "Could you please explain how your invention works?"

Inventor: "It's very simple! The client inserts their head here, and from these openings, manipulators with straight razors extend and shave the client!"

Marketing: "But wait! Every person has a unique head and face shape!"

Inventor: "Well... the first time, yes..." |

Our evaluation demonstrates a systematic improvement in the quality of generated invention dialogues when incorporating both the dialogue model and explicit CSP resolution. These enhancements result in performance gains of 3.3% and 5.3%, respectively, underscoring the critical role of CSP solvers in specific applications and the broader importance of logical reasoning companions in improving LLM outcomes.

The pedagogical value of automatically constructed invention dialogues is also evident. Compared to traditional plain-text learning materials, invention dialogues substantially improve learning efficiency. The most pronounced benefits are observed in step-by-step learning of concepts, followed by thinking hypothetically. Domain-specific evaluations reveal the highest pedagogical impact in healthcare, with significant benefits also seen in communication and computing. However, it is worth noting that in some domains and knowledge types, invention dialogues may occasionally hinder learning outcomes. Despite these exceptions, the overall assessment affirms the efficacy of invention dialogues in enhancing learning.

Additionally, our findings highlight that students trained with hypothetical invention dialogues can successfully construct similar dialogues in approximately 75% of cases. Among the evaluated features, plausibility is the most consistently achieved, followed by originality and consistency. These results underscore the potential of invention dialogues not only as a learning tool but also as a means of fostering creative and logical reasoning skills in learners.

References

- Blunno I, J. Cortadella, A. Kondratyev, L. Lavagno, K. Lwin, C.P Sotiriou. Handshake protocols for de-synchronization. In Proc. of 10th International Symposium on Advanced Research in Asynchronous Circuits and Systems (ASYNC 2004), pp. 149-158, (2004).

- Bonato A and Richard J. Nowakowski (2010) The Game of Cops and Robbers on Graphs . American Mathematical Society. STUDENT MATHEMATICAL LIBRARY Volume 61.

- Dechter R, Constraint networks, in: Encyclopedia of Artificial Intelligence, 2nd edn., Wiley, New York, 1992, pp. 276–285.

- Galitsky B , Dmitry Ilvovsky, and Elizaveta Goncharova (2019) On a Chatbot Providing Virtual Dialogues. Proceedings of Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing, pages 382–387, Varna, Bulgaria, Sep 2–4.

- Galitsky B (2022) Building dialogue structure by using communicative discourse trees. US Patent 11537645.

- Galitsky B. (2021). Chatbots for CRM and Dialogue Management. In: Artificial Intelligence for Customer Relationship Management. Human–Computer Interaction Series. Springer, Cham.

- Galitsky B (2025) Employing LLM to solve Constraint Satisfaction. In: Health Applications of Nero Symbolic AI. Elsevier.

- Gottlob G, Gianluigi Greco, and Francesco Scarcello (2012) Tractable Optimization Problems through Hypergraph-Based Structural Restrictions. Arxiv 1209.3419.

- Gottlob G, N. Leone, and F. Scarcello. A comparison of structural CSP decomposition methods. Artificial Intelligence, 124(2), pp. 243–282, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Robertson N and P.D. Seymour. Graph minors III: Planar tree-width. Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B, 36, pp. 49-64, 1984. [CrossRef]

- Fagin, R (1983). Acyclic Database Schemes (of Various Degrees): A Painless Introduction. CAAP'83, Trees in Algebra and Programming, 8th Colloquium, L'Aquila, Italy, March 9-11,.

- 12. A Hypergraph Based Approach for the 4-Constraint Satisfaction Problem Tractability.

- Oucheikh R, Ismail Berrada, Outman El Hichami (2019) A Hypergraph Based Approach for the 4-Constraint Satisfaction Problem Tractability. arXiv:1905.09083.

- Greco G, Francesco Scarcello (2016) Greedy Strategies and Larger Islands of Tractability for Conjunctive Queries and Constraint Satisfaction Problems. arXiv:1603.09617v2.

- O'Neill K, Shinjiro Sueda, Saleema Amershi, Mike Pavlin, Kyle Porter, and Byron Knoll (2024) AI Space. www.cs.ubc.ca/labs/lci/AIspace/constraint/.

- Wong R, Jefferson Van Wagenen, Nicole Riley, Camille Birch (2024) CSP Solvers https://cse442-17f.github.io/CSP-Solver/.

- Rocca J (2021) The exploration-exploitation trade-off: intuitions and strategies.

- Understanding e-greedy, optimistic initialization, UCB and Thompson sampling strategies. Towards Data Science. https://towardsdatascience.com/the-exploration-exploitation-dilemma-f5622fbe1e82Mahadevan S (2024) GAIA: Categorical Foundations of Generative AI. arXiv:2402.18732.

- Mahadevan S (2022) Unifying causal inference and reinforcement learning using higher-order category theory. arXiv:2209.06262.

Figure 1.

A non-verbal dialogue on inventing oil-to-money machine.

Figure 1.

A non-verbal dialogue on inventing oil-to-money machine.

Figure 2.

Alexander Bell and his invented telephone.

Figure 2.

Alexander Bell and his invented telephone.

Figure 3.

The hypothetical dialog around the Manhattan project.

Figure 3.

The hypothetical dialog around the Manhattan project.

Figure 4.

Combining category theory and CSP.

Figure 4.

Combining category theory and CSP.

Figure 5.

Visualization of contribution of this chapter.

Figure 5.

Visualization of contribution of this chapter.

Figure 6.

An invention dialogue with highlighted entities and components.

Figure 6.

An invention dialogue with highlighted entities and components.

Figure 7.

Defining natural transformation.

Figure 7.

Defining natural transformation.

Figure 8.

Naturality square.

Figure 8.

Naturality square.

Figure 9.

Features and sequential structure of invention dialogue. Red frame indicates the components which are absent in unsuccessful inventions.

Figure 9.

Features and sequential structure of invention dialogue. Red frame indicates the components which are absent in unsuccessful inventions.

Figure 10.

Two actions in the course of invention of a jet engine. The first action is to use continuous combustion in confined space, and the second action is to achieve a self-sustain cycle in step 1.

Figure 10.

Two actions in the course of invention of a jet engine. The first action is to use continuous combustion in confined space, and the second action is to achieve a self-sustain cycle in step 1.

Figure 11.

Crossword puzzle and its associated hypergraph (on the top). A hypertree decomposition (on the bottom).

Figure 11.

Crossword puzzle and its associated hypergraph (on the top). A hypertree decomposition (on the bottom).

Figure 12.

A hypergraph H for invention entities, and a join tree JT(H).

Figure 12.

A hypergraph H for invention entities, and a join tree JT(H).

Figure 13.

The primal graph for invention entities G(H), and the incidence graph for them inc(H).

Figure 13.

The primal graph for invention entities G(H), and the incidence graph for them inc(H).

Figure 14.

Inventing a de-synchronized circuit (in the middle) given the synchronous circuit. The handshake protocol is shown on the bottom.

Figure 14.

Inventing a de-synchronized circuit (in the middle) given the synchronous circuit. The handshake protocol is shown on the bottom.

Figure 15.

A tree projection Ha of Q0 w.r.t. for entities of an invention A, B, …. On the right: the join tree JTa.

Figure 15.

A tree projection Ha of Q0 w.r.t. for entities of an invention A, B, …. On the right: the join tree JTa.

Figure 16.

A proponent, her agents and their opponent.

Figure 16.

A proponent, her agents and their opponent.

Figure 17.

A triple of co-inventors.

Figure 17.

A triple of co-inventors.

Figure 18.

Financing an invention.

Figure 18.

Financing an invention.

Figure 19.