1. Introduction

HAIs are ubiquitously associated with a prolonged length of stay (LOS) and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), while putting patients at serious risk of morbidity and in-hospital mortality [

1]. The inability to fully implement infection prevention protocols, coupled with steep increases in antibiotic use throughout the pandemic, have only facilitated further development of antimicrobial resistance [

2], which is now responsible for almost 5 million deaths each year [

3]. Effective IPCs are crucial to ending avoidable NIs and an integral part of the delivery of safe, effective, high quality health service delivery [

4]. The contribution of malnutrition to this remains uncertain, but earlier studies have shown that neonatal infections rates are 3-20 times higher than that of higher-income countries compared to newborn children in low-and middle income countries (LMICs) [

5]. Inadequate and unsafe water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) and the lack of adherence to guidelines and practices of infection control protocols (ICPs), unsafe waste management, exacerbated by the overcrowding of health facilities, increase the risk for HAIs [

6].

Hospital-acquired infections or Nosocomial infections (NIs) are a major challenge for LMICs that have limited healthcare resources. HAIs/NIs are acquired infections that were not previously present in the patient prior to hospital admission [

7]. Nosocomial infections increase the costs of healthcare due to added antimicrobial treatment and prolonged hospitalization. Since the prevalence of NIs is generally higher in developing countries with limited resources, the socioeconomic burden is even more severe in these countries [

8]. HAIs can be caused by microorganisms already present in the patient’s skin and mucosa (endogenous) or by microorganisms transmitted from another patient or the surrounding environment (exogenous). There are three common modes of transmission direct contact, indirect contact through contaminated objects, and airborne droplets [

9].

The current burden of malnutrition globally is unacceptably high, and every country in the world is affected by malnutrition. Severe acute malnutrition (SAM) is the leading cause of death among under-5-year-old children in addition to pneumonia and neonatalsepsis with 20% of pediatric hospital admissions in Ethiopia and is a cause of 25%- 30% ofdeath in many poor countries [

10]. The problem of SAM is not only a medical disorder, but also a social disorder. Therefore, successful treatment of severely malnourished patients requires both medical and social efforts and [

7] In 2019, 144 million under-five-year-old children were suffering from stunting while 47 million were wasted of which 14.3 million were severely wasted worldwide. Across the world, SAM has contributed to 3.6 million under-five children death [

11].

Malnutrition affects between 20% and 50% of hospitalized patients at admission, with further declines expected during hospitalization. Hospital malnutrition is a predictor of longer stay, impaired wound healing, increased risk of infections and complications, and increased morbidity and mortality. Recovery from SAM, especially among HAIs, remains challenging, insufficient, and even little is known about recovery time from SAM among those infected and its predictors among children aged 6 to 59 months in Ethiopia, in general, and in the study area in particular. The proportion of recovery from SAM among children aged 6 to 59 months in Ethiopia ranges from 58.4% to 87% [

10]. Hospital acquired infections (HAIs, called Nosocomial infections (NIs), are among the most significant causes of morbidity and mortality in healthcare settings around the world.

Worldwide, hundreds of millions of patients are estimated every year in developed and developing countries are affected by HAIs [

12]. In the USA, approximately 2 million patients developed HAIs, and nearly a hundred thousand of these patients were estimated to die annually, and this ranked HAIs as the fifth leading cause of death in acute care hospitals annually [

13]. From the study done by Sheng

et al [

14]

, in 2017 NIs were directly involved in 80.5% of patients and 67.9% of death occurred within two weeks. The available evidence also showed that the financial burden, increased resistance of microorganisms to antimicrobials, prolonged hospital stay, and sometimes deaths are caused by HAIs. In developing countries, the magnitude and incidence of HAIs remains underestimated and uncertain specifically in pediatric populations. Furthermore, in Ethiopia, studies focused only on adults were previously conducted, and many of these were limited to surgical site infections, [

15,

16] and few on urinary tract (UTI) and bloodstream infections (BSIs), and mostly common forms of HAIs in Ethiopia. In pediatric studies of factors and incidence investigation of HAIs, 13 per 100 admitted children was reported cumulative incidence, and SAM and LOS are reported as an underlying factor to the risk of HAIs [

17].

In Ethiopia, regardless of the growing burden of various types of HAIs; it continues to receive relatively low public health priority. HAIs have continued to be a public health issue due to their devastating effect and double burden on both patients and their families in general; however, no research has been conducted focusing on the management appropriateness of HAIs [

15].

However, the impact of malnutrition on the incidence of NIs and their effect on the duration of hospitalization have not been established among paediatric patients in developing countries. Due to the current need for investigation, we have planned to evaluate the recovery time of acquired hospital infections among severely acute malnourished children admitted to Asella referral and teaching hospital. The evaluation of the outcomes, time-to-recovery and predictors of hospital-acquired infections at hospital levels with SAM should emphasise accurate assessment of malnutrition using validated assessment tools.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Area, Design and Period

The pediatric and child health department of Asella Referral and Teaching Hospital hosted the study. Presently, the hospital provides care for approximately 841,158 patients a year, including 19,452 children under five years of age and 4395 pregnant women from various agro-ecological environments in the Oromia region state's Arsi Zone, West Arsi, and East Shewa Zone. A retrospective cohort study design was implemented to select the infections acquired children in the healthcare setting among SAM from Hospital registry data from May to June 2023.

2.2. Population of the Study

The targeted study included the records of all children under 59 months of age who were treated for SAM in the inpatient therapeutic feeding center of the Asella referral and teaching hospital. All the children were admitted according to the Ethiopian National SAM guidelines and WHO recommendation (i.e, MUAC, bilateral edema, WFH/L, and medical complications) [

18,

19]. The data registry included in this study was includes the children admitted in the hospital Therapeutic Feeding Unit (TFU) from September 9, 2020, to January 20, 2022. Incomplete documentation (incomplete data charts, an outcome not known), admission criteria not registered in their TFU card and SAM Children treated at Outpatient Therapeutic Program (OTP) units were excluded.

2.3. Sample Size Determination and Sampling Procedure

The sample size is calculated using the double population formula in Epi-info version 7.2 considering the recent report assumption of the proportion of children recovered in exposed 65.4% and adjusted to increase sample 70% [

20] and children recovered in the non-exposed 96%taken from a retrospective cohort study considering Ethiopian context [

10,

21]. The ratio of non-exposed to exposed (r=1) =1:1, where p1 is the proportion of subjects (recovered) in the exposuregroup, p2 is the proportion of subjects (recovered) in the non-exposuregroupand Power= 80% =1-β, Z

β=0.84. Taking into account the assumption to calculate the sample size, α= level of significance, Zα/2=1.96 at 95% CL and compensation for the missing effect of the potential source error design of 2 is used. Considering the missing records/incomplete data, 10% of the sample is included, and the final sample size of 493 SAM records were included. Eligible cases were selected using existing medical registration numbers using a systematic sampling technique to generate the required samplesize, starting from the most recent month and goingbackward, based on the sequence of medical card numbers.

2.4. Data Collection and Quality Assurance

Structured data extraction tools adapted from the Ethiopian SAM management protocol [

22], and reviewing relevant literature [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Data was collected from patient cards and SAM registration logbook by data collectors who was trained in data collection techniques. Data were extracted for one month and half by two nurses working in the pediatric ward and four administrative staff members from the patient registry ward where they received intensive work training. The overall activities were controlled by the principal investigator. The technique for data collection is daily extraction from the patient's medical record and the SAM treatment registry retrospectively. The supervisors strictly followed the general activities of the data collection on a daily basis to ensure the completeness of the questionnaire and to provide further clarification and support to the data collectors.

2.5. Data Management and Analysis

Epi-info was used for data entry and the data was subsequently exported to Stata version 17 for data cleaning and analysis. Finally, data were analyzed using the R software version 4.3.3. A descriptive Kaplan–Meier (KM) survival estimator and log-rank test method was used, of which non-parametric survival analysis was used to estimate the survival between SAM and hospital acquired infected SAM recovery. The independent effect of the survival predictors for the recovery time was estimated using the Cox proportional hazard model. The Akaike information criteria (AIC) were used to identify model fitness . The Cox proportional hazard assumption was checked graphically (log-log plot) & statistically (Global goodness of fit test). Finally, the Cox Snell residual test was used for checking final model Adequacy. Goodness of fit of the model was assessed using the Cox-Snell residual technique. The model was built by a stepwise analysis procedure. The potential predictors for the entire model were selected by bi-variable Cox proportional regression with cut-off point P <0.25. The association between predictors and survival of the children with SAM was summarized using adjusted hazard ratio (AHR) and statistical significance was tested at P < 0.05.

2.6. Ethical Consideration

Formally, the research was ethically approved by letter of support is sent to Oromia and South Nation, nationalities and People regional Health Bureaus with the letter of minute no. (ምሳኒፕ/ 453/13/21). The Oromia Regional Health Bureau Ethics review committee also reviewed the research for the implementation and approved the research with the IRB minute number of BEF/IRB/1-16/3022. Before starting -the data collection, ethical clearance was obtained from Arsi University College of Health Sciences. I/n addition to this, a supportive letter was prepared to the Pediatrics department of Arsi University, as well as permission to review the registry card was obtained from the Clinical Medical Director of the Asella Teaching and Referral Hospitals. To ensure confidentiality, the name and other identifiers of patients, physicians, and other healthcare members who examine the patient are not recorded in the data abstraction format.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.1.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics, Nutritional Status, and Incidence of HAIs

Baseline Data Characteristics of Children

From the cohort of all children with SAM followed retrospectively, we recruited 493 children with SAM based on inclusion criteria (190 found nosocomial infection, that is, 38.5%) from hospital registry cards. The median age of the children is 11 months with an interquartile range of 7 months. Among these children followed, 292 (59.2%) were male and 245 (40.8%) were female. Most (n = 426, 86.4%) of the children were from rural areas. Regarding the immunization history of these children, 232 (47.10%) were fully immunized and 446 children (90.5%) EBF. Additionally, 424 (86%) children started complementary foods (CF). Bottle-feeding was practiced among 235 children (47.7%) and recovery was registered among 96 children (i.e. 39.2%) of the SAM children practicing bottle-feeding. Among children who started and completed complementary feeding according to the WHO guideline, 211 children (that is, 83.7%) recovered whereas, only 40 (16.3%) of children was recovered among who did not complete therapeutic feeding (

Table 1).

Table 2. Therapeutic feeding and supplementation characteristics of the children.

Based on the current investigation of recovery between different SAM groups, the marasmus was the predominant type of SAM recorded (n = 447, 90.70%), where half of them were recovered from SAM during therapeutic feeding management (n=221, 90.2%). Various types of graded edema were observed among 43 (8.70%) of SAM children. Folic acid, Vitamin A and zinc supplementations were provided to 76 (15.4%), 13 (2.6%), and six (1.2%) of children with SAM, respectively. Regarding vitamin A supplementation, among the total children (n=252) expected to take supplementation according to the WHO recommendation, only 2.78% of the children received vitamin A (data are presented in supplementary Table S1). Formula 75 (F-75) was the main supplement during the treatment course 380 (77.1%) (

Table 2). Six (6) children received zinc supplementation [Zn (CH

3COO)

2] as part of their diarrhea treatment, according to the 2019 SAM management guideline in Ethiopia and the WHO standard.

1.1. Magnitude of HAIs, Body Composition, and Clinical Characteristic of Children

Regarding the hospital-acquired infection assessment out of the 493 children screened 190 (38.5%) of them acquired NI during hospital treatment as presented in

Table 3. From these children, recovery was observed among 70 (28.6%) children during treatment, where this recovery is strongly affected with the presence of HAIs (

=16.724, p < 0.001) and Fever (

=8.09, p = 0.003). The predominant type of HAIs that was named by the physician and recorded accordingly was Pneumonia 181(36.7%) followed by UTI 21(4.30%). Regarding to the clinical history 328 (66.5%) of the children have a recorded history of vomiting during treatments. Diarrhea, and cough are the most common clinical symptoms among these children reported at 283 (57.4%) and 338 (68.6%) respectively, where recovery is low in this group of children (the recovery from SAM among the dehydrated group is 142 (49.1%) and 167 (47.85%) among the group of cough symptoms).

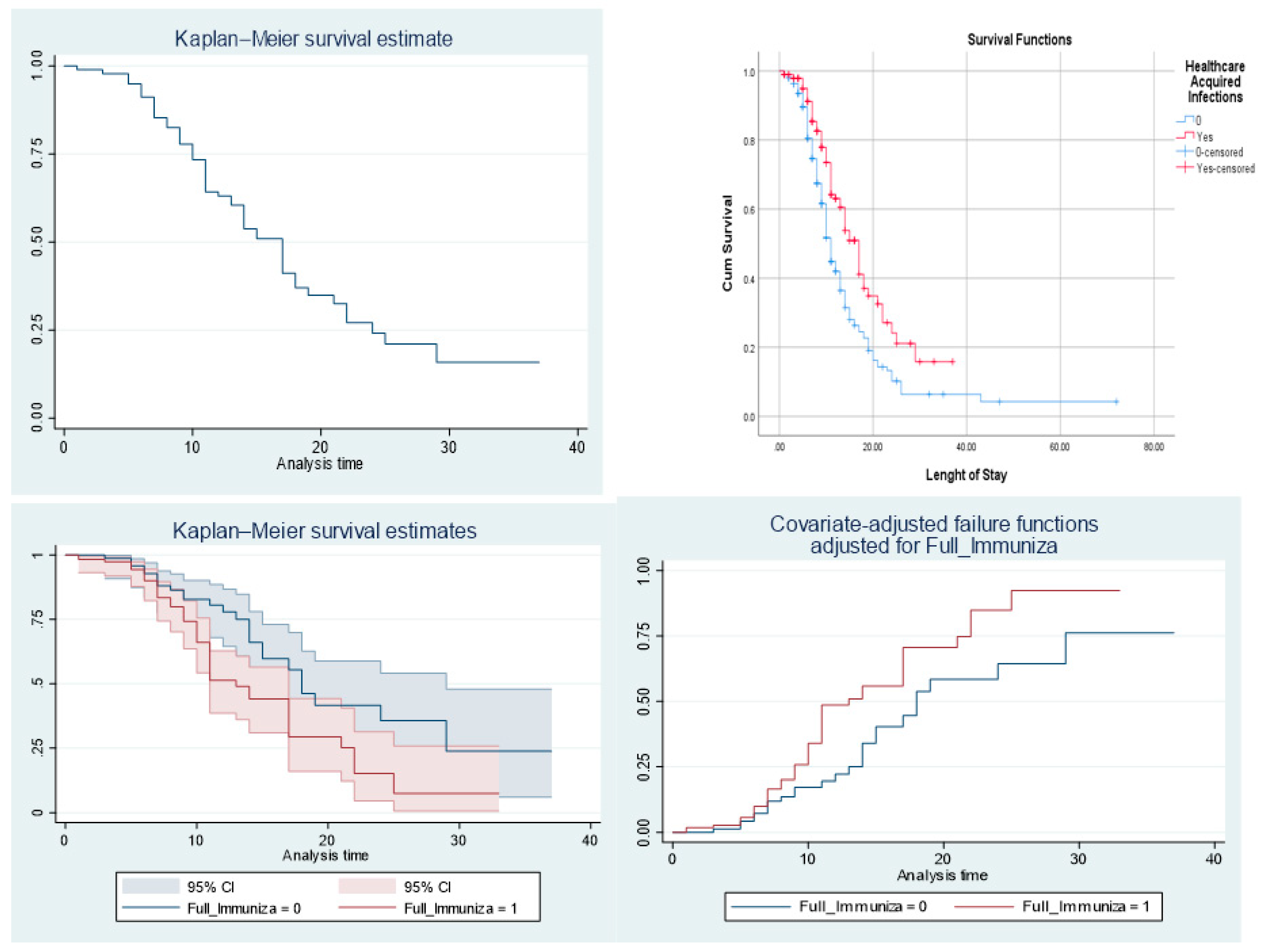

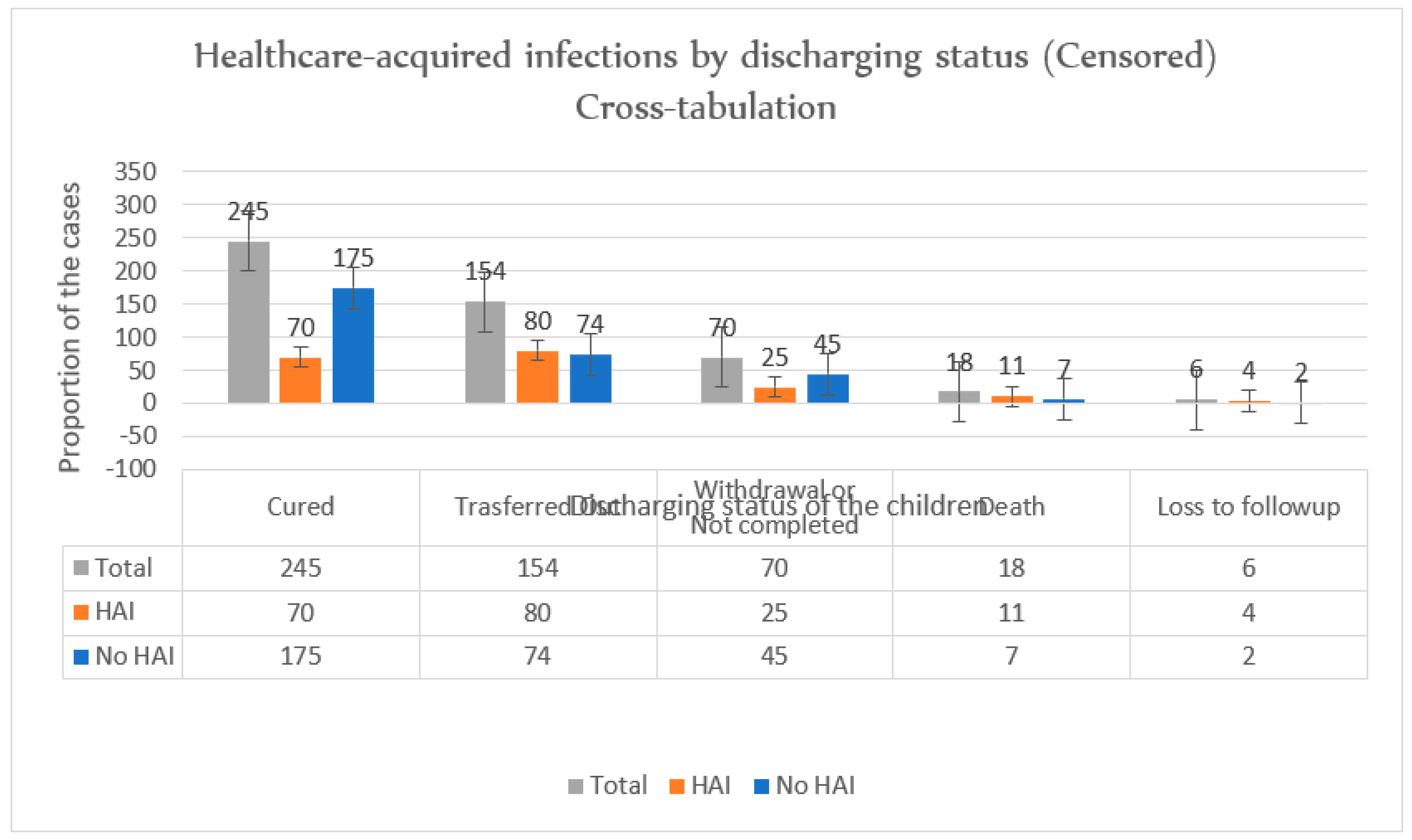

1.2. The Median Time to Recovery and Treatment Outcomes

Regarding the survival outcome of the 493 cohorts, the median recovery time is 18.12 days with an interquartile range of 1.22 days (95% CI: 15.73: 20.50) (

Figure 1). In full observation of the children during treatment, 245 (49.7%) of the children were recovered or cured, and 154 (31.2%) of the SAM children were transferred out, 70 (14.2%) of the children were released (they had not completed the treatment) and 18 (3.7%) of the deaths were reported (

Figure 2). The survival curves for the children recruited in the survival analysis were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier curve. The estimated survival status of children with HAIs among SAM shows that most of the children recovered within the first 17 days. The survival of the SAM children was evaluated using the log-rank test between the gender, fully immunization and antibiotics medications, the result shows significantstatistically (

= 3.5, df = 1, p= 0.06, (

= 0.53, P= 0.467), and, (

= 4.34, p = 0.0373 respectively). When comparing the discharged status of children followed by the NIs (HAIs) category, about 252 (50%) of the children recovered from the HAIs during treatment.

1.3. Incidence Rate (IR) of the Recovery

The management of HAIs associated SAM for complicated or uncomplicated diseases was treated at the stabilization center according to the WHO and SAM management guideline for the 1957 days were 72 (37.9%) recovery was registered [

22]. The incidence (the rate at which a new event occurs) within the specified period is calculated based on the time overall children were following during the treatment 1957 days . The IR of recovery/survival was 0.03678 per-person day (36.8 recovery/1000 person days) among NIs. The IR of death among non NI associated SAM was 0.04 per-person day (4.0 death/1000 person days) and 0.0656 per-person day (6.56 death/1000 person days) among the NI group per day observation. The recovery rate of the SAM associated with NI is 29.39% and 175 (57.75)%% among associated SAM treated children.

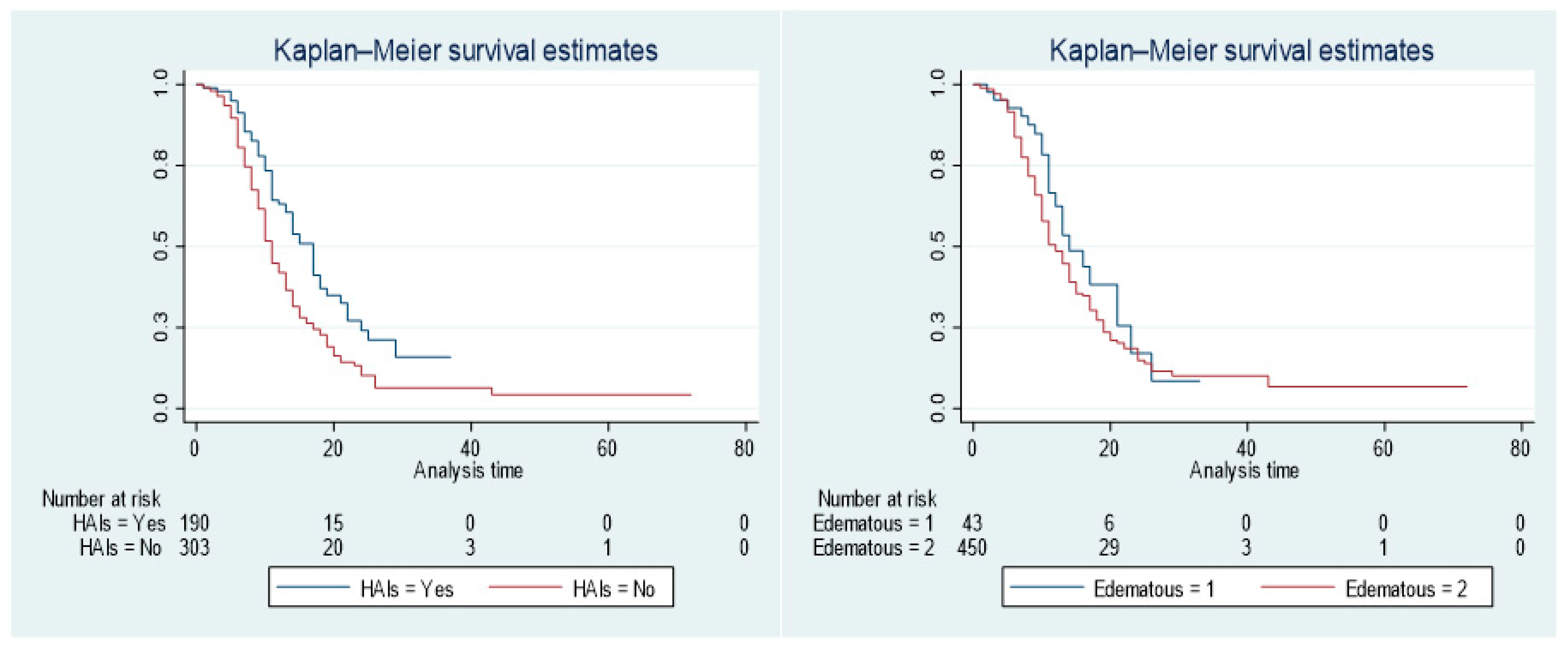

The Kapla-Mierer curve showed the survival of the offspring among SAM with or without HAIs/NIs (

Figure 3). When comparing the median survival of children among HAIs, the group of SAM with HAIs had a worse survival rate than the group of children without HAIs. However, compared to children who did not acquire infections at hospital after started treatment, children with SAM associated with HAIs had longer survival times.

Figure 3.

The Kaplan-Meier survival estimates by HAIs status and Edematous group.

Figure 3.

The Kaplan-Meier survival estimates by HAIs status and Edematous group.

| Log-rank test for equality of survivor functions (For mortality indicator) |

Log-rank test for equality of survivor functions (For survival indicator) |

| |

Observed |

Expected |

|

|

|

|

Observed |

Expected |

| HAIs |

events |

events |

|

|

|

HAIs |

events |

events |

| Yes |

7 |

7.25 |

|

|

|

Yes |

72 |

103.66 |

| No |

11 |

10.75 |

|

|

|

No |

173 |

141.34 |

| Total |

18 |

18 |

|

|

|

Total |

245 |

245 |

| |

chi2(1) |

0.01 |

|

|

|

|

chi2(1) |

18.27 |

| |

Pr>chi2 |

0.9042 |

|

|

|

|

Pr>chi2 |

0 |

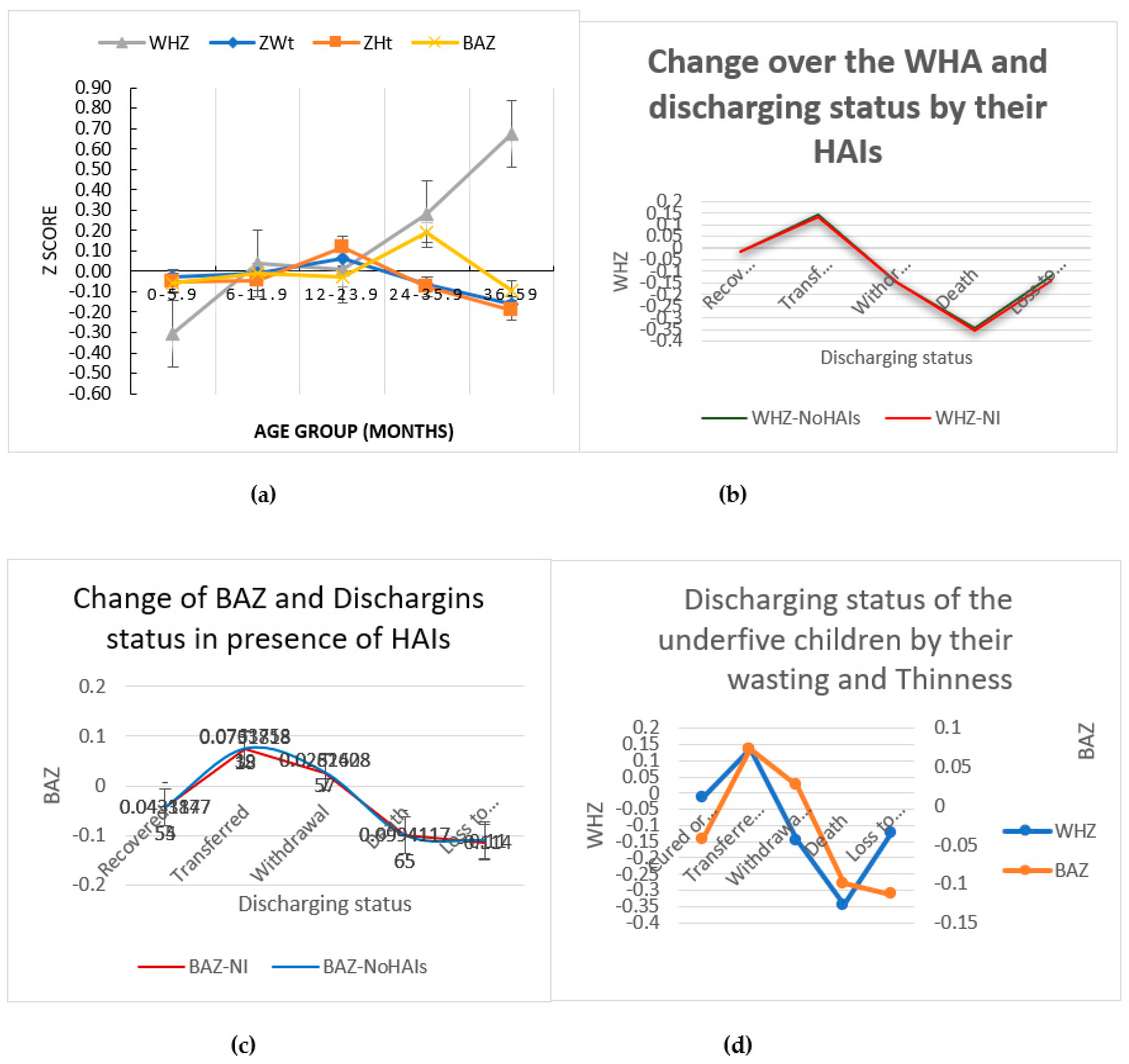

1.1. Body Composition Assessment and Nutritional Indicators by Their Discharging Status

Figure 4 showed the evaluation of body composition of the children and their nutritional status at the time of discharge or in the record before an event (a to d). Although there are still obstacles in the way of implementing the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) definition of pediatric malnutrition, which includes several characteristics of poor health outcomes of a malnourished child, in daily clinical practice [

29]. In an effort to harmonize the method for using Z-score to diagnose malnutrition in children, global data suggested z-score has a higher sensitivity for both forecasting death and identifying children who are more likely to experience SAM [

18,

19].

Figure 4 (a) shows that, according to the WHZ Z score, children under the age of zero to five and a half months fell in the range of -0.5 < Z-score< -0.10, indicating a higher risk of severity in SAM and a good predictor of the age group in question predicting mortality after hospital release. On the other hand, children in the 36- to 59-month age group fell into the 0.10 < Z-score < 0.90 area, which means that there is no assurance that they will recover fully recover and catch up on their growth [

30].

The distribution of SAM children according to their HAI status is shown in

Figure 4 (b). Both children who contracted infections while in hospital and those who did not fall into the categories of death and loss of follow-up had low WHZ Z scores (- 0.35 < WHZ < -0.05), denoting a higher risk of severity. The children's BAZ was used for the current investigation. Children who did not survive to follow-up were at risk of wasting compared to the remaining group of children, regardless of their HAI status, based on the Z score of BMI for age (BAZ) of the children that suggested identifying the risk of wasting (

Figure 4(c)). However, as

Figure 4 (d) illustrates, the inclusion of thinness variables in the model has demonstrated a significant change in every group of children throughout discharge.

1.1. Predictors of Hospital-Acquired Infections Among Severely Acutely Malnourished Children

We conducted a bivariate Cox regression analysis to identify candidate factors for the entire model with cut-off point P <0.25. Children's sex, exclusive breastfeeding, bottle-feeding, complementary feeding, immunization, blood in the stool, tuberculosis infection, intravenous fluids, HAIs and their types (UTI), and Formula-75 were the variables. TB infections, intravenous fluid use, exclusive breastfeeding, full vaccination, and HAIs were identified as independent predictors of SAM survivalwith HAI (P-value < 0.25).

Children who received exclusive breast-feeding had a chance of full recovery of 1.458 (AHR = 1.458, 95% CI: 1.249-1.841, P = 0.012) higher than as compared to those who did not receive such care. Furthermore, compared to children with SAM without TB infection, those with a history of prior TB infection had a 10% (AHR = 0.9, 95% CI 0.834 – 0.928, P = 0.038) higher chance of experiencing a delayed recovery rate. Additionally, children who used intravenous fluids had a 30% higher probability of experiencing delayed recovery than children who did not (AHR = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.561 – 0.903, P = 0.006), a finding supported by highly significant statistical reports. Furthermore, compared to children who did not acquire any infections, children who acquired hospital infections (HAI) during treatment experienced a high percentage 40% delay in recovery (AHR = 0.60, 95% CI 0.445 – 0.829, P = 0.002), and the statistical report indicated that the result is significant (

Table 4).The Cox regression model adequacy test using proportional hazards assumption test

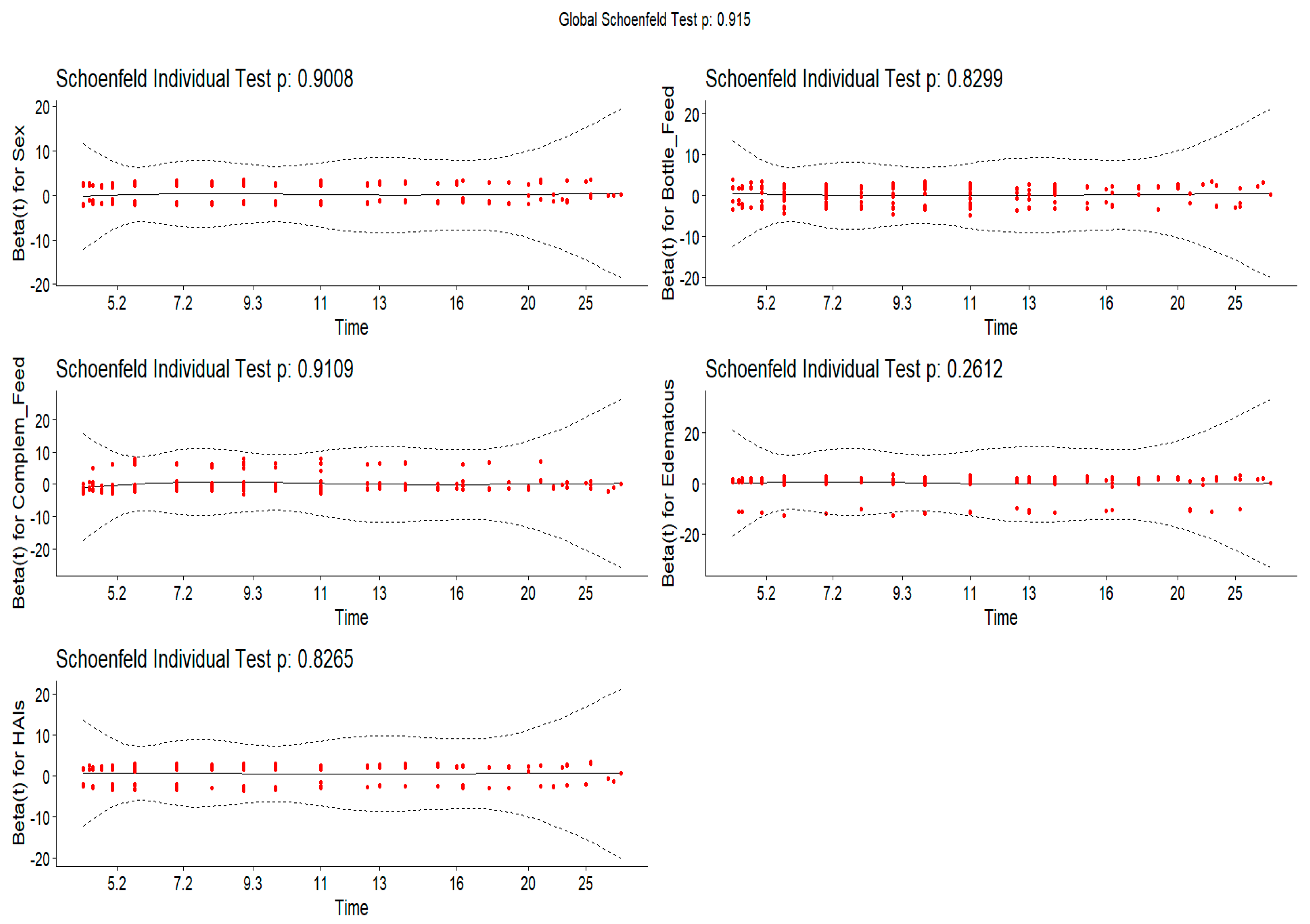

3.2. Diagnostic Test Based on the Schoenfeld Residuals

To test the proportional hazards assumption, the Schoenfeld residuals - a plot of residual vs. time event - were produced for each individual variable at a particular time for all covariates (

Figure 5). Based on the obtained plot we understand that the straight line passing through a residual value (0) with gradient 0 shows that the variable satisfies the proportional hazards assumption and we conclude that it does not depend on time value. Furthermore, based on the plot's output, each covariate's independence test between the residuals and the time is not statistically significant (p >0.05), and the global test is also not significant (

= 2.66, df = 5, P = 0.7525) which indicates enough to support the adequacy of the model to predict the dependent variable. Additionally, the model was tested using Akaike's information criterion and Bayesian information criterion (AIC: 607.96 and BIC: 624.196)

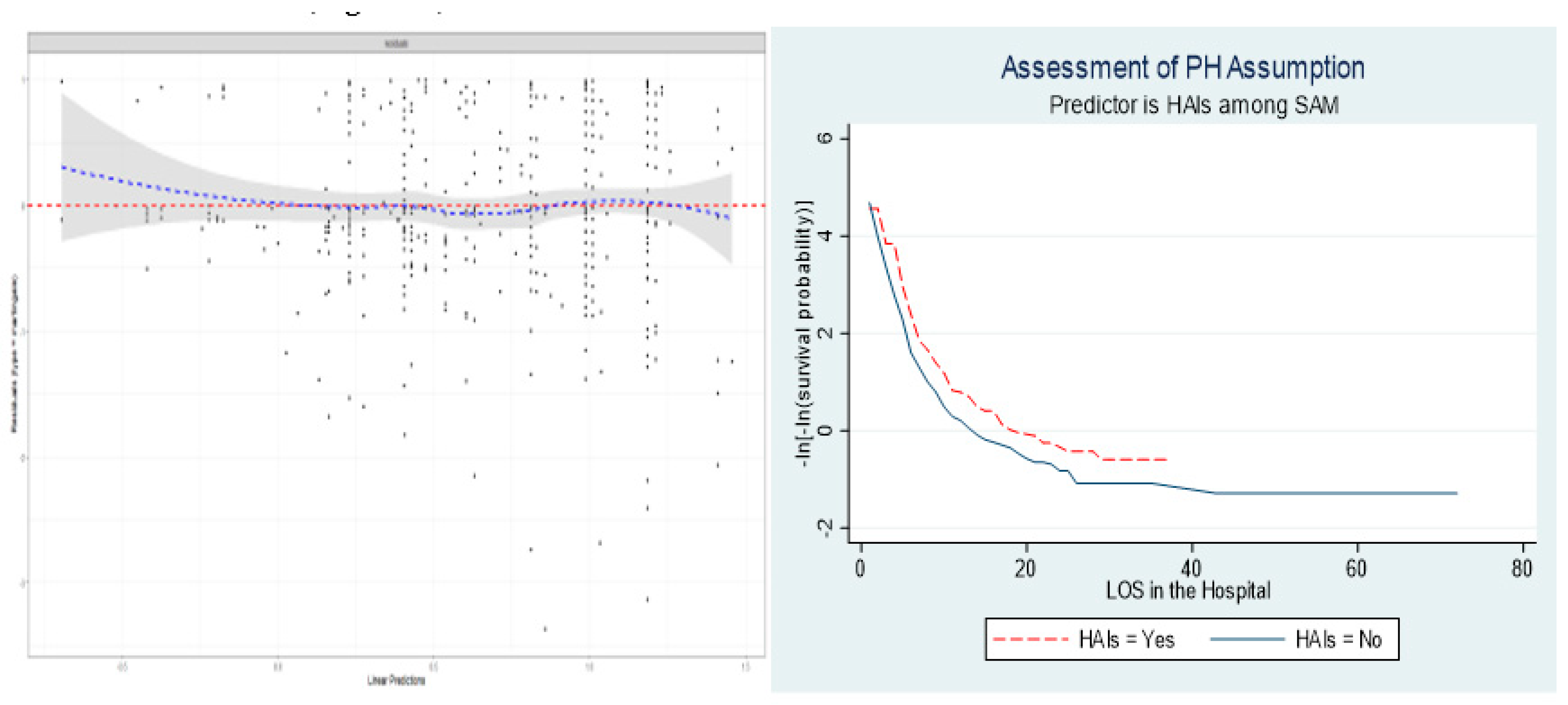

3.3. Model Goodness-of-Fit and Diagnostic Validity

The other test of the standardized residual test for the reliability analysis of the difference between an observed data and predicted value was performed accordingly. Model fitness adequacy was assessed using Cox Snell residuals, where the residual test is used to compare the survival rate between different groups of categories. After fitting the multivariate Cox proportional risk model (an indicator tool for survival analysis and measures the time until an event occurs), the graph of the Nelson-Aalen cumulative hazard function and the cox Snell residuals variable were compared to the hazard function to the diagonal line (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

The incidence rate of death among SAM was 0.04 per-person day (4.0 death/100 person days) and 0.0656 per-person day (6.56 death/100 person days) among the NI group per day observation. The recovery rate of the HAIs associated SAM is 70 (36.8%) and 175 (57.8%) of the non-HAIs associated SAM. The recovery rate from HAIs linked with SAM was below and far from the recovery rate of children with SAM who received therapy at the stabilization center and it is below the minimum standard of WHO recommendation [

31]. This could be due inclusion criteria that used focusing HAIs specifically to SAM and poor management of addressing the national and WHO guidelines. In addition, the recovery rate of SAM children in the study area is lower than in the previous study conducted in Ethiopia [

23,

24,

25,

26,

28,

32,

33]. In this study, marasmus (non-edematous) was the predominant, which accommodates 90.3% parts and in which less than 50% of the children were recovered compared to other types of SAM that in line with study in Bangladesh [

34].

Concerning the children's nutritional status during discharge, we used child length/height and weight collected retrospectively to determine weight-to-height Z score and BMI for-Age Z score. The BMI was obtained by determining the ratio of child weight (in Kg) and length (in M2) as WHO child growth standard for 2006. For the determination of nutritional status, children whose age between 36 and 59 months had still a risk of severe malnutrition according to the BAZ indices. Furthermore, children between the ages of 0 and 5.9 months were at risk of severe malnutrition using both the BAZ and the WHZ indices. The BAZ indicator of the children increased significantly as the age of the child increased. Whereas, looking at the clinical discharge of the children at all stages, those who acquired infections at hospital had lower WHZ significantly compared to the children who did not acquire infections. In another way of reporting child WHZ according to their clinical discharge status, we observed that children who transferred to different programs had a WHZ between 0.1 and 0.15, while the WHZ of children who did not recover (died) was below -0.3.

Regarding the outcome of the treatment of these children, the recovery rate of the children in the current study was 50%, which is below the minimum standard of the SPHERE project (the recovery rate of > 75%) and other studies in Ethiopia [

24,

25,

32]. Similarly, the incidence rate of death among SAM was 0.04 per-person day (4.0 death/100 person days). However, EBF and completed vaccination are independent predictors of the survival of children with SAM (complete EBF and vaccination reduced the risk of not being recovered). This study had shown a similar finding to the study conducted in different part of Ethiopia and SSA [

20,

35,

36] and which would be associated with the strategies explained as the role of vaccination in protecting several diseases [

25].

The majority of predictors of SAM recovery in the presence of HAIs having TB infection had a high risk of low recovery than those who did not have TB infection. Regarding the implementation of intravenous fluids, those who received IV fluids are highly at risk of low recovery compared to those children who did not receive IV fluids in this study. Marasmus (90.1%), the most prevalent complications and cough (68.6%) and diarrhea (57.4%) were the two most prevalent symptoms detected in children with SAM associated with HAIs, where it is the most frequently reported by different scholars in Ethiopia [

24,

25,

32], Zambia [

37] and Kenya [

38].

Looking for the type of edematous malnutrition, it is a predominant type of SAM in the current study, which makes the result in line with the study conducted at Jimma University and other African studies [

25,

26,

33,

39]. This result might indicate that there is a frequent and high intake of carbohydrates and an insufficient intake of protein-rich foods.

Children who have severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) have a very poor survival rate. Malnourished children with HAIs had much worse recovery results than malnourished children without HAIs. The data show a significantly reduced survival rate when compared to regular WHO statistics, highlighting the urgent need for national focus on hospital-acquired illness prevention and management. Children who received antibiotic (commonly: Amoxicillin) during care were recovered far better than those who did not (Adjusted Hazard Ratio [AHR]: 0.607, 95% CI: 0.445–0.82, P = 0.002). This emphasizes how crucial the right antibiotic treatment is to be enhancing these children's likelihood of recovery. Additionally, vaccination played a big part. During illness and hospital care, children who had completed their vaccination programs showed a greater survival rate (AHR: 1.91, 95% CI: 1.16–3.13, P = 0.010). This suggests that children who had received all of their recommended vaccinations had almost double the chance of recovering from their illnesses.

In another way of the rate of recovery, the current study shows 2.93 per 100 (95% CI: 2.34, 3.68) per person which is below the rate of recovery registered in different Ethiopian retrospective [

25] and longitudinal studies. This could be due to our studies that included the HAIs in the major way as important variables in addition to other factors that contributed to the low recovery of HAI-associated SAMs with the shortage of pediatricians in the health facility setting. Anemia, TB infections, HAIs, and bottle feedings are the most common comorbidities seen and the main contributors to the delay of recovery, which is consistent with different reports by scholars report in Africa [

24,

25,

32,

38,

40]

5. Strength and Limitation

The nature of the study design, which excludes the active data to use in additional research, is the main weakness of the study. We were unable to pinpoint the precise date of discharge and the kind of hospital-acquired infections in a few patient reports. Due to inadequate patient biographies, missing CBC results, and missing entry date, we have eliminated 47 patient reports. The study sheds important light on an issue with little previous research: how infections acquired in healthcare facilities can impede the healing of critically malnourished infants.

One of our strengths is that, in contrast to other similar studies that have been published, we attempted to include each child's CBC result, have multiple clinical nurses cross-check the data, and appoint one supervisor from the child-nursing department. We paid particular attention to the SAM associated to HAIs rather considering HAIs as a variable. Because only one hospital was used for the study, the findings may not be as applicable to different contexts or geographical areas. The ability to pinpoint certain bacteria causing recovery delays has been limited by the lack of comprehensive microbiological data on the many forms of HAIs.

6. Conclusion and Recommendation

The recovery rate from severe malnutrition among HAI was lower than the minimal standard recovery of SAM according to the National and WHO recommendations, as well as lower than the recovery rate of children with SAM undergoing care at the stabilization center. Stunting and underweight outcomes are the focus of evidence-based treatments to prevent malnutrition, and may not be entirely transferable to prevent wasting. Based on the inclusion criteria derived from hospital registration cards, we enrolled 493 children with SAM for the current study. However, because certain HIAs are resistant to antibiotics, they can be very difficult to treat.

The most common type of SAM reported was marasmus and edema, from which half of the cases were recovered with therapeutic feeding management. The existence of HAIs is closely related to children's recovery during treatment. On the contrary, the interquartile survival range is 6 days and the median survival duration is 9 days. Among HAIs, the incidence rate of survival/recovery was 0.0293 per-person day (2.93 death/100 person days). During daily observation, the incidence rate of death for the SAM group was 0.04 per-person day (4.0 death/100 person days) and for the NIs group it was 0.0656 per-person day (6.56 death/100 person days).

When it came to children with SAM linked to HAIs, the median recovery time was 17.0 + 1.2 days. The standard definition of pediatric malnutrition, which incorporates several indicators of poor health outcomes in a malnourished child, is still not widely applied in clinical practice. Regardless of their status with HAI, children who did not live to follow-up were at risk of wasting compared to the other group of children. Compared to children who did not receive this kind of care, those who were exclusively breastfed had a higher probability of making a full recovery. Additionally, children who received intravenous fluids and were not infected with tuberculosis (TB) were at increased risk of suffering a slower recovery rate.

As a result, we suggested investigating more research on the impact of HAIs on the recovery of malnutrition, particularly to SAM. It is challenging to pinpoint the precise causes of HAIs due to the various intersecting variables linked to children's eating habits. Successful treatment is achieved by the initial use of the correct antimicrobial agent in the most appropriate dose to optimize the likelihood of clinical and bacteriological success and minimize drug-related toxicities. However, the availability of waste management system and strategies to minimize environmental exposure is believed to reduce HAIs in hospitalized patients and health care workers, and need critical attentions.

To determine the reasons generating the NIs using various control elements, the longitudinal study will demonstrate a notable contribution. To put it another way, we strongly recommend conducting an interventional trial to treat SAM with and without HAIs in a hospital setting. Determining the most common type of HAI in a hospital setting also requires defining the various types of HAIs.

Author Contributions

TBE, came up with the idea to develop concept, organization, took a part in data collection supervision, data cleaning, analysis, and manuscript drafting. TD, KTR, AH, and SG supervision and assisted in revising the initial draft and finalization of manuscript data analysis. GE clinical advisor and helped with the editing the data collection instruments and the manuscript. KB concept development, overall management, supervision, funding and manuscript edition. The final manuscript was read and approved by all writers.

Funding

This study was partially funded by the Addis Ababa University, There were no other external organizations that funded this research. Therefore, the University has no conflicts of interest in this study. .

Data availability

The data used in this this study will be available and author will provide whenever required.

Ethics Statement

The human study protocol in which it is involved was examined and approved by the College of Natural and Computational Science, AAU, College of Health Science, Arsi University and Oromia regional IRB committee. It was made clear to pediatrics department of School of Medicine in Asella referral and teaching hospital.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratitude goes to the Addis Ababa University for review and approval of the study protocol, and partial fund support. The authors would also like to extend their gratitude to the Oromia Regional Health Bureau, data collectors, and supervisors for their valuable contribution to the success of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Lydeamore, M.J.; Mitchell, B.G.; Bucknall, T.; Cheng, A.C.; Russo, P.L.; Stewardson, A.J. Burden of five healthcare associated infections in Australia. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2022, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Salah, A.B.; Amri, F.; Chlif, S.; Rzig, B.; Kharrat, H.; Hadhri, H.; et al. Investigation of the spread of human visceral leishmaniasis in central Tunisia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2000, 94, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärki, T.; Plachouras, D.; Cassini, A.; Suetens, C. Burden of healthcare-associated infections in European acute care hospitals. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2019, 169 (Suppl. S1), 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassini, A.; Högberg, L.D.; Plachouras, D.; Quattrocchi, A.; Hoxha, A.; Simonsen, G.S.; et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: a population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidi, A.K.; Huskins, W.C.; Thaver, D.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Abbas, Z.; Goldmann, D.A. Hospital-acquired neonatal infections in developing countries. Lancet 2005, 365, 1175–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lydeamore, M.J.; Mitchell, B.G.; Bucknall, T.; Cheng, A.C.; Russo, P.L.; Stewardson, A.J. Burden of five healthcare associated infections in Australia. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2022, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S. Nosocomial infection: general principles and the consequences, importance of its control and an outline of the control policy-a review article. Bangladesh Med. J. 2009, 38, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raka, L. Lowbury Lecture 2008: infection control and limited resources–searching for the best solutions. J. Hosp. Infect. 2009, 72, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahida, S.; Islam, A.; Dey, B.; Islam, F.; Venkatesh, K.; Goodman, A. Hospital acquired infections in low and middle income countries: root cause analysis and the development of infection control practices in Bangladesh. Open J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.; Sadler, K. Outpatient care for severely malnourished children in emergency relief programmes: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2002, 360, 1824–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H. World health statistics 2022: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. 2022.

- Allegranzi, B.; Storr, J.; Dziekan, G.; Leotsakos, A.; Donaldson, L.; Pittet, D. The first global patient safety challenge “clean care is safer care”: from launch to current progress and achievements. J. Hosp. Infect. 2007, 65, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.E.; Neiman, M. Persistent copulation in asexual female Potamopyrgus antipodarum: evidence for male control with size-based preferences. Int. J. Evol. Biol. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, W.-H.; Wang, J.-T.; Lin, M.-S.; Chang, S.-C. Risk factors affecting in-hospital mortality in patients with nosocomial infections. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2007, 106, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yallew, W.W.; Kumie, A.; Yehuala, F.M. Risk factors for hospital-acquired infections in teaching hospitals of Amhara regional state, Ethiopia: a matched-case control study. PloS One 2017, 12, e0181145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earnest, J.; Mansi, R.; Bayati, S.; Earnest, J.A.; Thompson, S.C. Resettlement experiences and resilience in refugee youth in Perth, Western Australia. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahiledengle, B.; Seyoum, F.; Abebe, D.; Geleta, E.N.; Negash, G.; Kalu, A.; et al. Incidence and risk factors for hospital-acquired infection among paediatric patients in a teaching hospital: a prospective study in southeast Ethiopia. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, S.M.; Bi, C.; Thaete, K. Construction of lambda, mu, sigma values for determining mid-upper arm circumference z scores in US children aged 2 months through 18 years. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2017, 32, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization, WH. WHO child growth standards and the identification of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children: joint statement by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children's Fund. 2009.

- Bizuneh, F.K.; Tolossa, T.; Bekonjo, N.E.; Wakuma, B. Time to recovery from severe acute malnutrition and its predictors among children aged 6–59 months at Asosa general hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. A retrospective follow up study. PloS One 2022, 17, e0272930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabalo, M.Y.; Seifu, C.N. Treatment outcomes of severe acute malnutrition in children treated within Outpatient Therapeutic Program (OTP) at Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia: retrospective cross-sectional study. J Health Popul Nutr 2017, 36, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FMOH National Guideline for the Management of Acute Malnutrition in Ethiopia. Gov. Ethiop. 2019.

- Gebremichael, D.Y. Predictors of nutritional recovery time and survival status among children with severe acute malnutrition who have been managed in therapeutic feeding centers, Southern Ethiopia: retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebremichael, M.; Bezabih, A.M.; Tsadik, M. Treatment outcomes and associated risk factors of severely malnourished under five children admitted to therapeutic feeding centers of Mekelle City, Northern Ethiopia. Open Access Libr. J. 2014, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussen Kabthymer, R.; Gizaw, G.; Belachew, T. Time to cure and predictors of recovery among children aged 6–59 months with severe acute malnutrition admitted in Jimma University medical center, Southwest Ethiopia: A retrospective cohort study. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarso, H.; Workicho, A.; Alemseged, F. Survival status and predictors of mortality in severely malnourished children admitted to Jimma University Specialized Hospital from 2010 to 2012, Jimma, Ethiopia: a retrospective longitudinal study. BMC Pediatr. 2015, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oumer, A.; Mesfin, F.; Demena, M. Survival Status and Predictors of Mortality among Children Aged 0-59 Months Admitted with Severe Acute Malnutrition in Dilchora Referral Hospital, Eastern Ethiopia. East Afr. J. Health Biomed. Sci. 2016, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yallew, W.W.; Kumie, A.; Yehuala, F.M. Point prevalence of hospital-acquired infections in two teaching hospitals of Amhara region in Ethiopia. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 2016, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N.M.; Corkins, M.R.; Lyman, B.; Malone, A.; Goday, P.S.; Carney, L.; et al. Defining pediatric malnutrition: a paradigm shift toward etiology-related definitions. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2013, 37, 460–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.N.; Carsley, S.; Lebovic, G.; Borkhoff, C.M.; Maguire, J.L.; Parkin, P.C.; et al. Misclassification of child body mass index from cut-points defined by rounded percentiles instead of Z-scores. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutaki, M.; Halbeisen, F.S.; Spycher, B.D.; Maurer, E.; Belle, F.; Amirav, I.; et al. Growth and nutritional status, and their association with lung function: a study from the international Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Cohort. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, K. Survival status and predictors of mortality among children aged 0–59 months with severe acute malnutrition admitted to stabilization center at Sekota Hospital Waghemra Zone. J Nutr Disord Ther. 2015, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Teferi, E.; Lera, M.; Sita, S.; Bogale, Z.; Datiko, D.G.; Yassin, M.A. Treatment outcome of children with severe acute malnutrition admitted to therapeutic feeding centers in Southern Region of Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 2010, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, Z.; Chowdhury, D.; Hoq, T.; Begum, M.; Shamsul Alam, M. A comparative study between SAM with Edema and SAM without Edema and associated factors influencing treatment, outcome & recovery. Am. J. Pediatr. 2020, 6, 468–475. [Google Scholar]

- Eyi, S.E.; Debele, G.R.; Negash, E.; Bidira, K.; Tarecha, D.; Nigussie, K.; et al. Severe acute malnutrition’s recovery rate still below the minimum standard: predictors of time to recovery among 6-to 59-month-old children in the healthcare setting of Southwest Ethiopia. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2022, 41, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegeye Mk Belew Ak Aserese, A.D.; Daba, D.B. Time to recovery from malnutrition and its predictors among human immunodeficiency virus positive children treated with ready-to-use therapeutic food in low resource setting area: A retrospective follow-up study. Health Sci. Rep. 2023, 6, e959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwanza, M.; Okop, K.J.; Puoane, T. Evaluation of outpatient therapeutic programme for management of severe acute malnutrition in three districts of the eastern province, Zambia. BMC Nutr. 2016, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbert, A.; Thuo, N.; Karisa, J.; Chesaro, C.; Ohuma, E.; Ignas, J.; et al. Diarrhoea complicating severe acute malnutrition in Kenyan children: a prospective descriptive study of risk factors and outcome. PloS One. 2012, 7, e38321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munthali, T.; Jacobs, C.; Sitali, L.; Dambe, R.; Michelo, C. Mortality and morbidity patterns in under-five children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in Zambia: a five-year retrospective review of hospital-based records (2009–2013). Arch. Public Health 2015, 73, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buse, K.; Hawkes, S. Health in the sustainable development goals: ready for a paradigm shift? Glob. Health 2015, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).