Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. OU Relation and ETAS Model

2.2. GR Relation

2.3. Stress-Change Calculation

3. Data

3.1. Earthquake Catalogs

3.2. Fault Models

4. Results

4.1. Pre-Doublet-Quake Sequence

4.1.1. b-Value and Change in Seismicity Rate

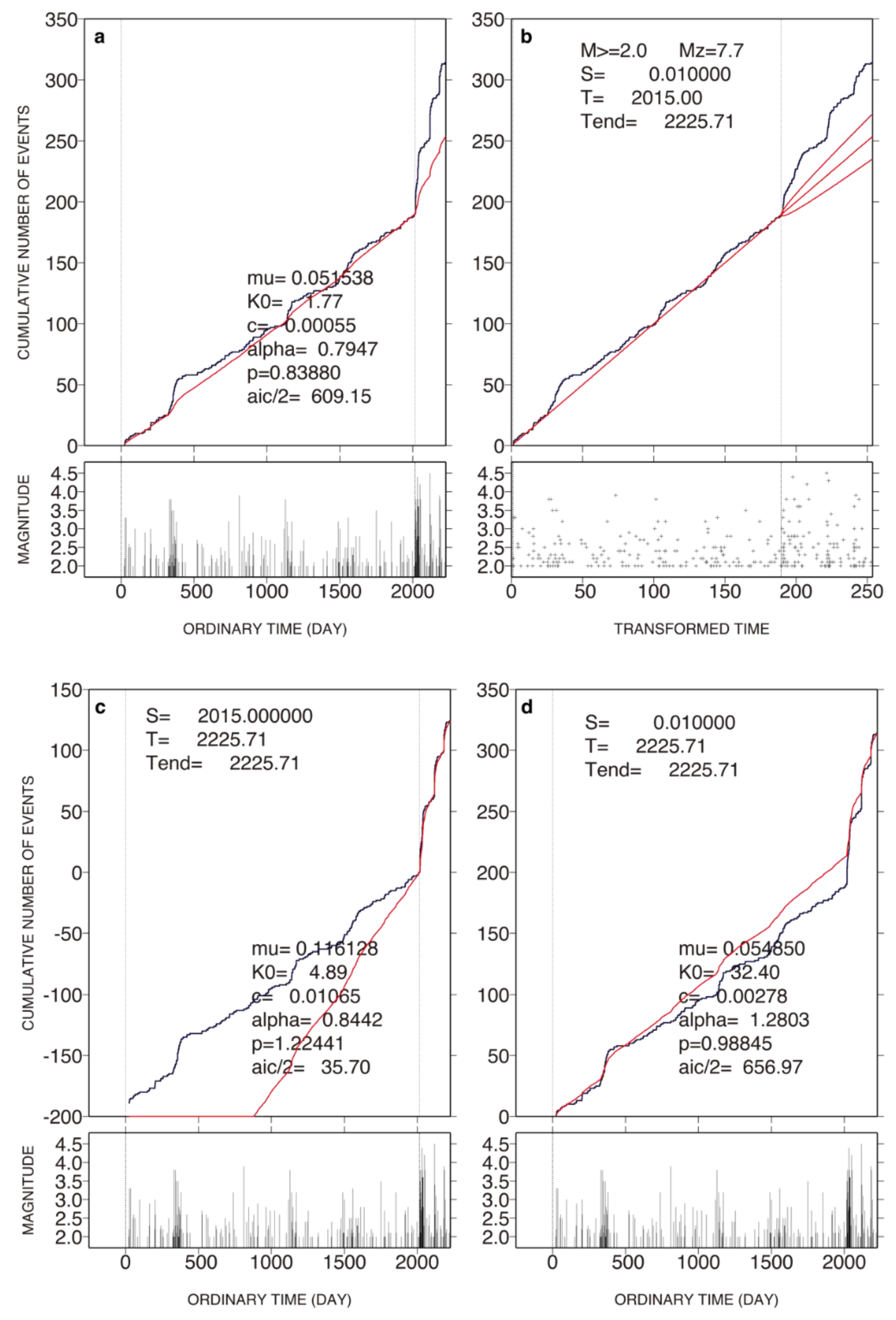

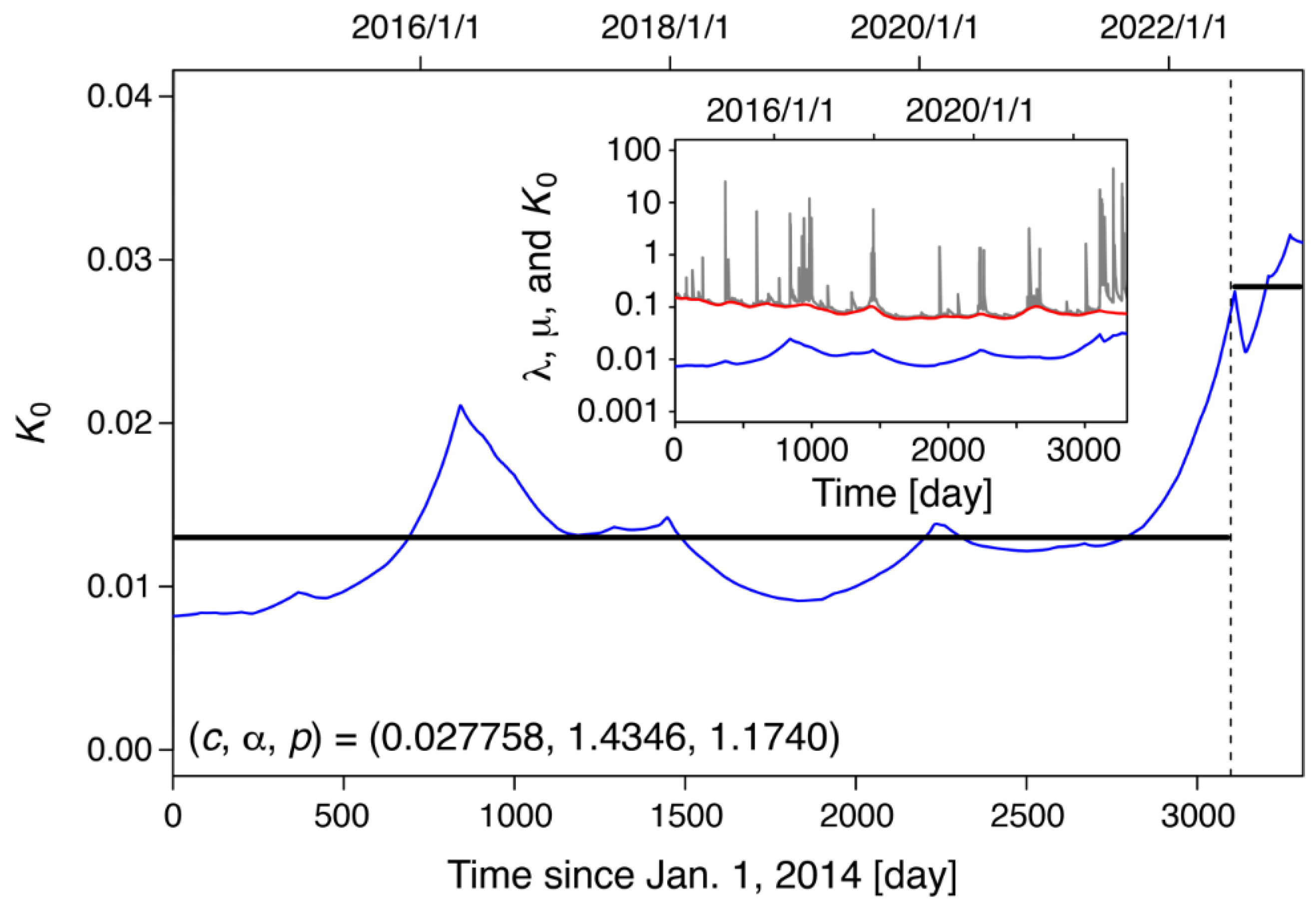

4.1.2. Background Activity and Clustering Activity

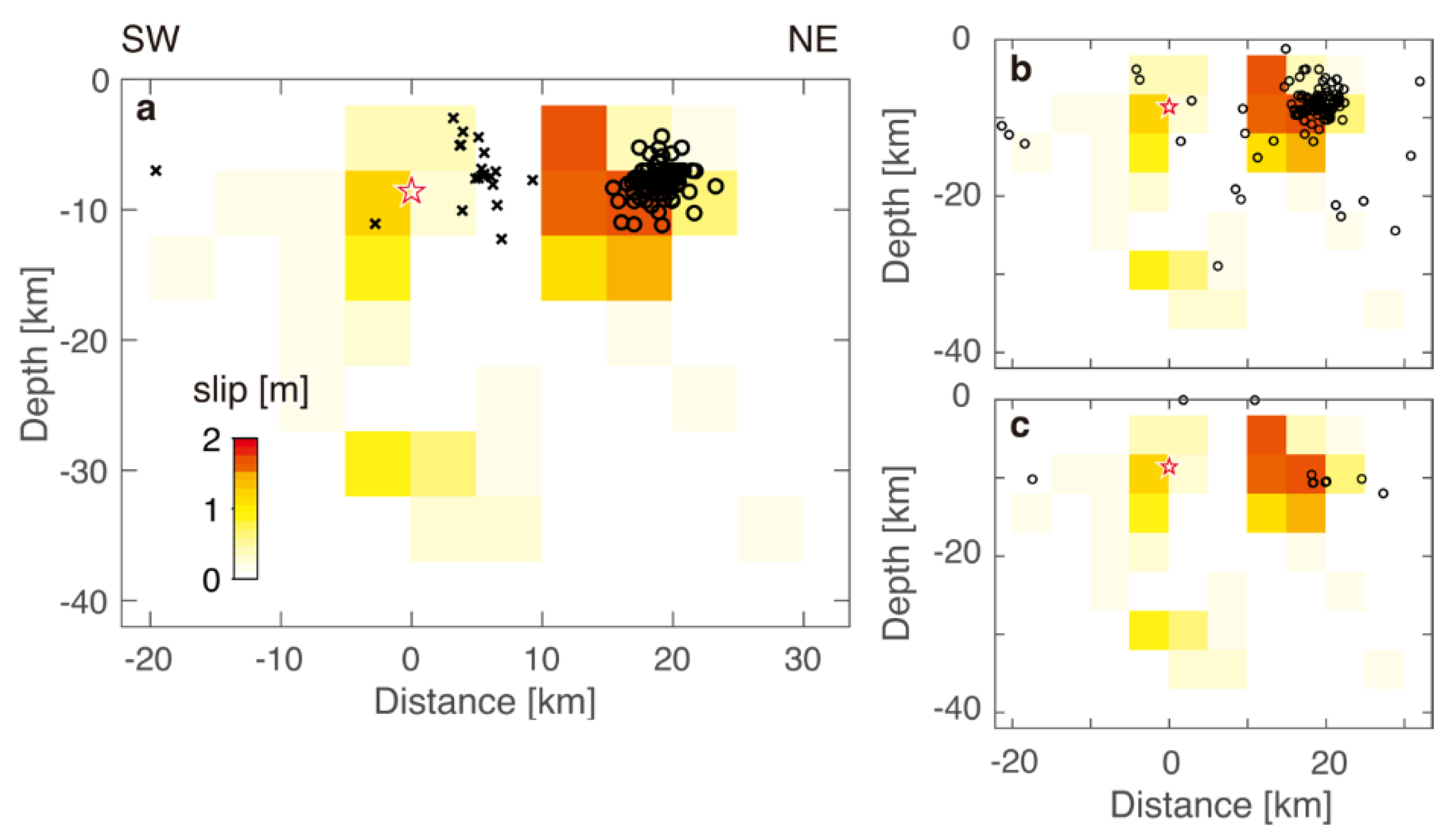

4.1.3. Slip Distribution of the M7.7 Quake and Preceding Seismicity

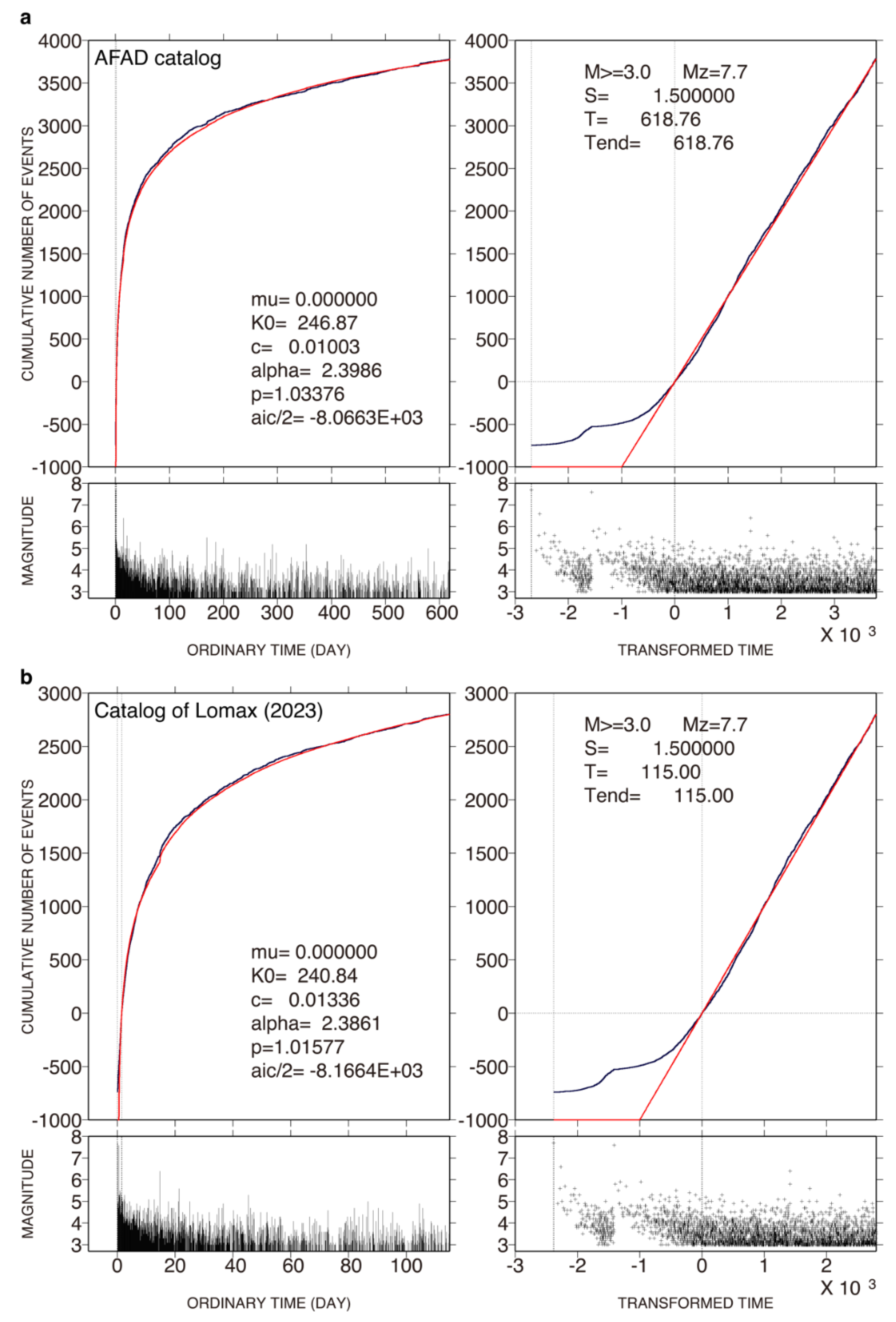

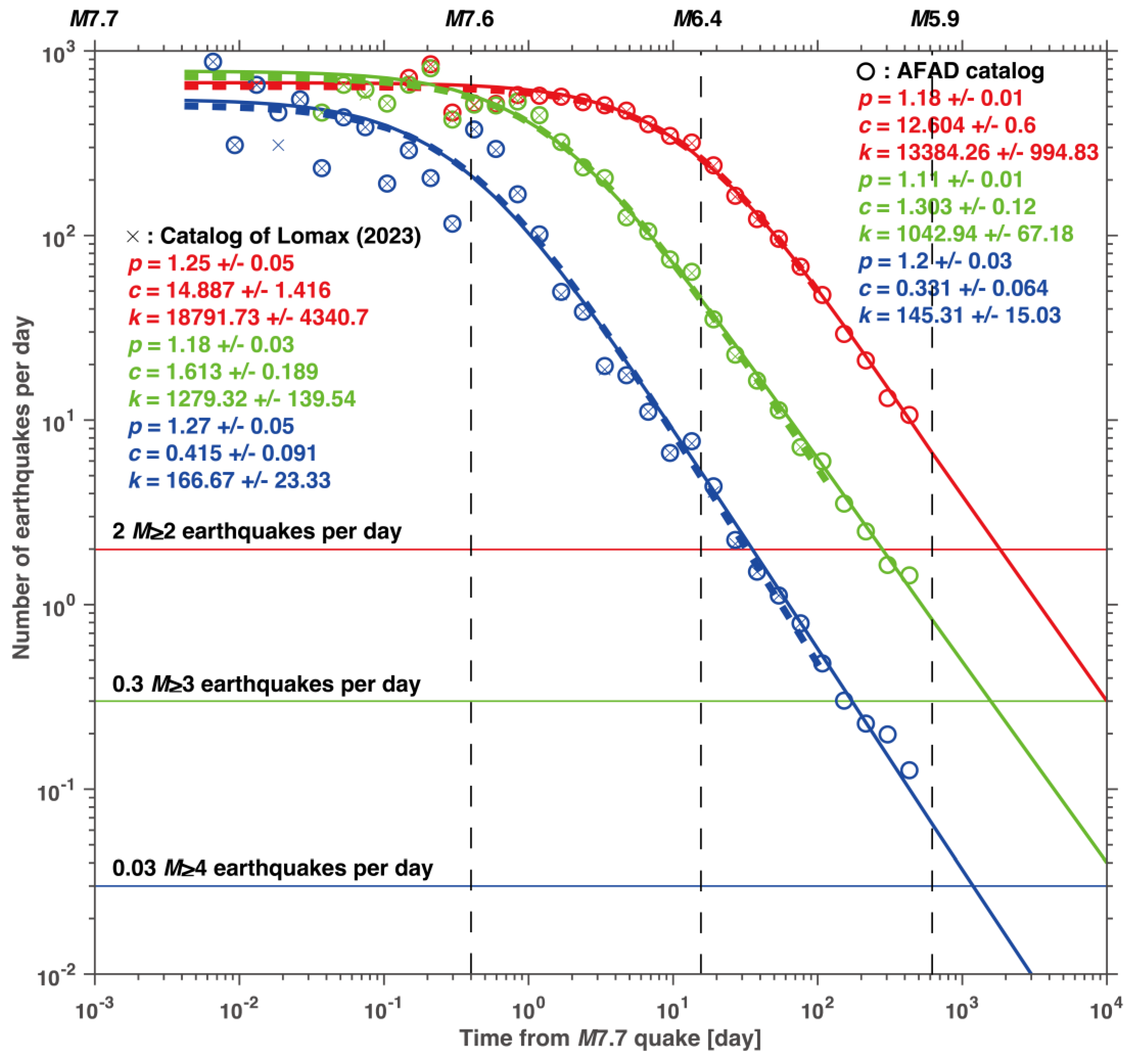

4.2. Post-Doublet-Quake Sequence

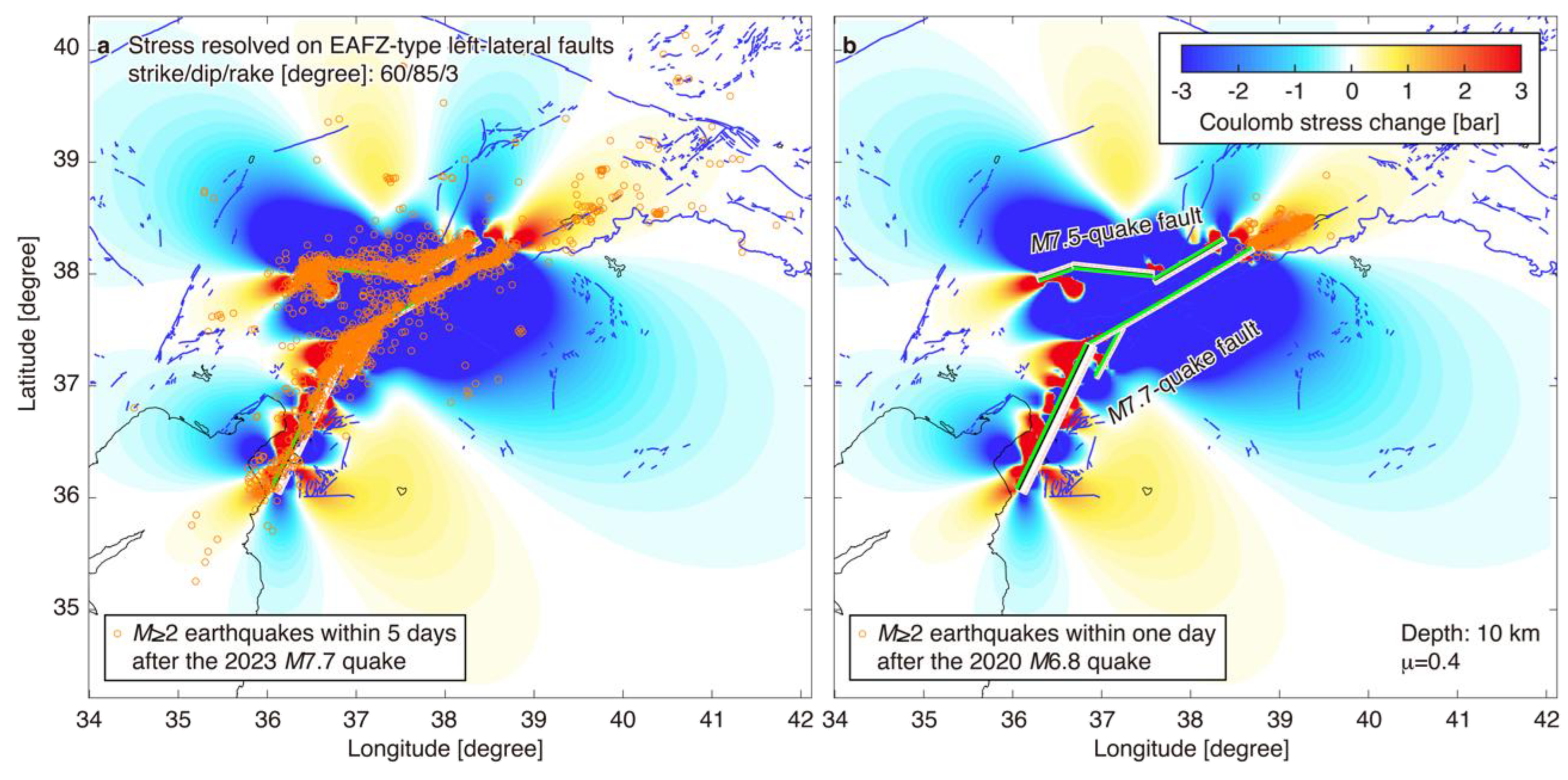

4.2.1. Seismicity Immediately After the Doublet Quakes

4.2.2. Seismicity Until the M6.4 Quake

4.2.3. Seismicity Until the M5.9 Quake

5. Discussion

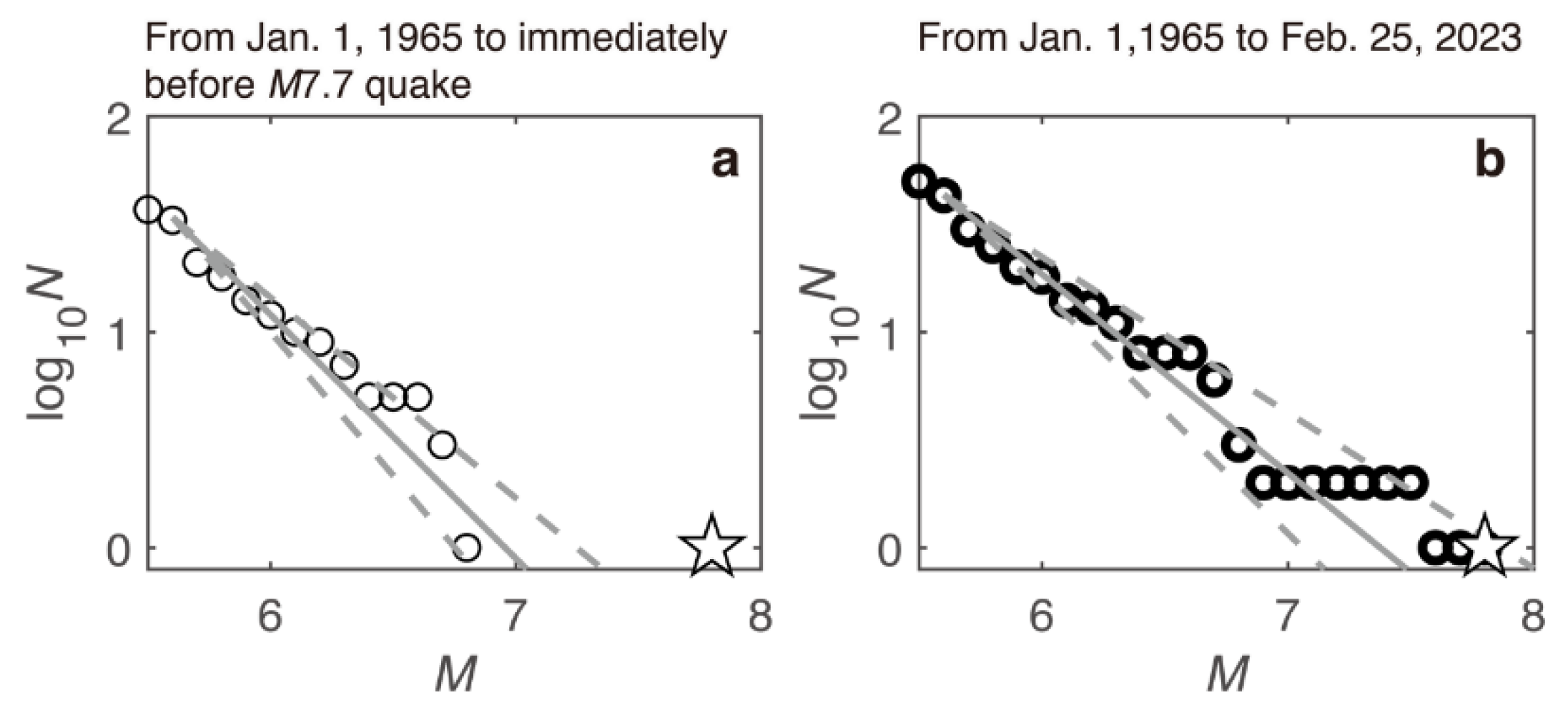

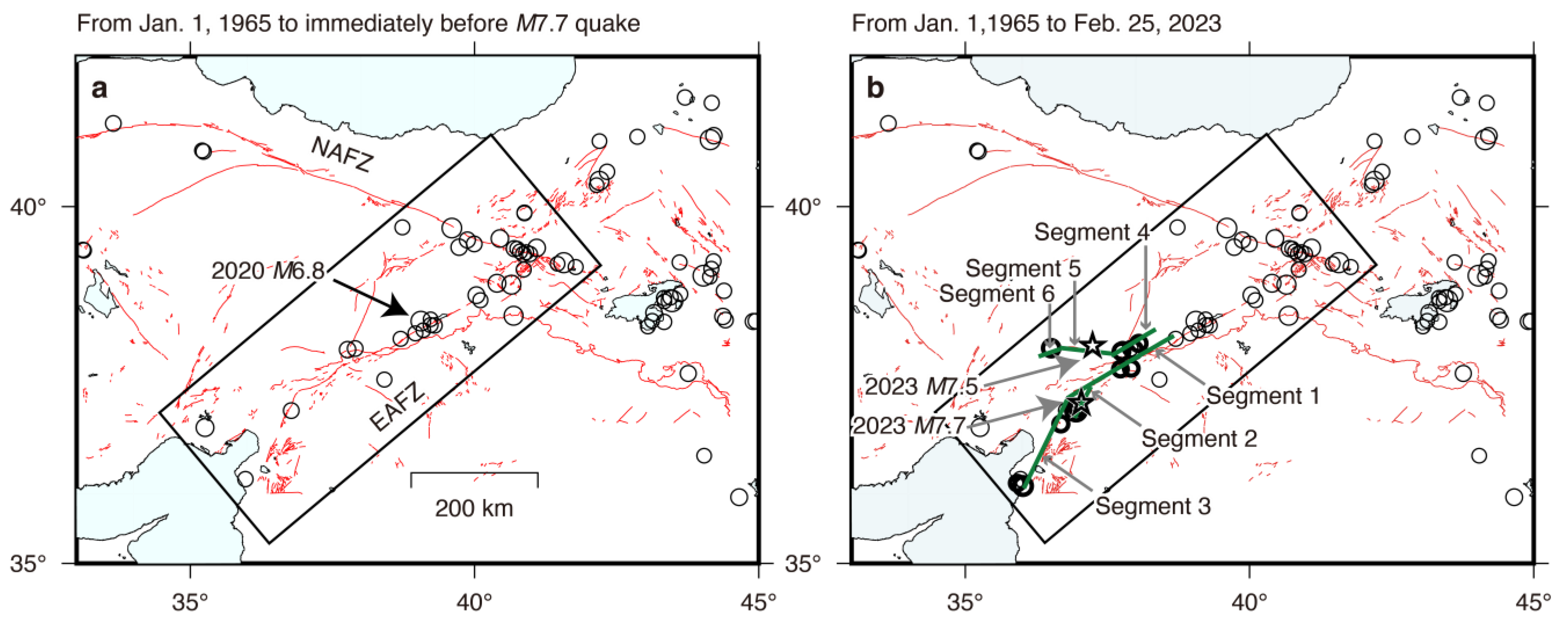

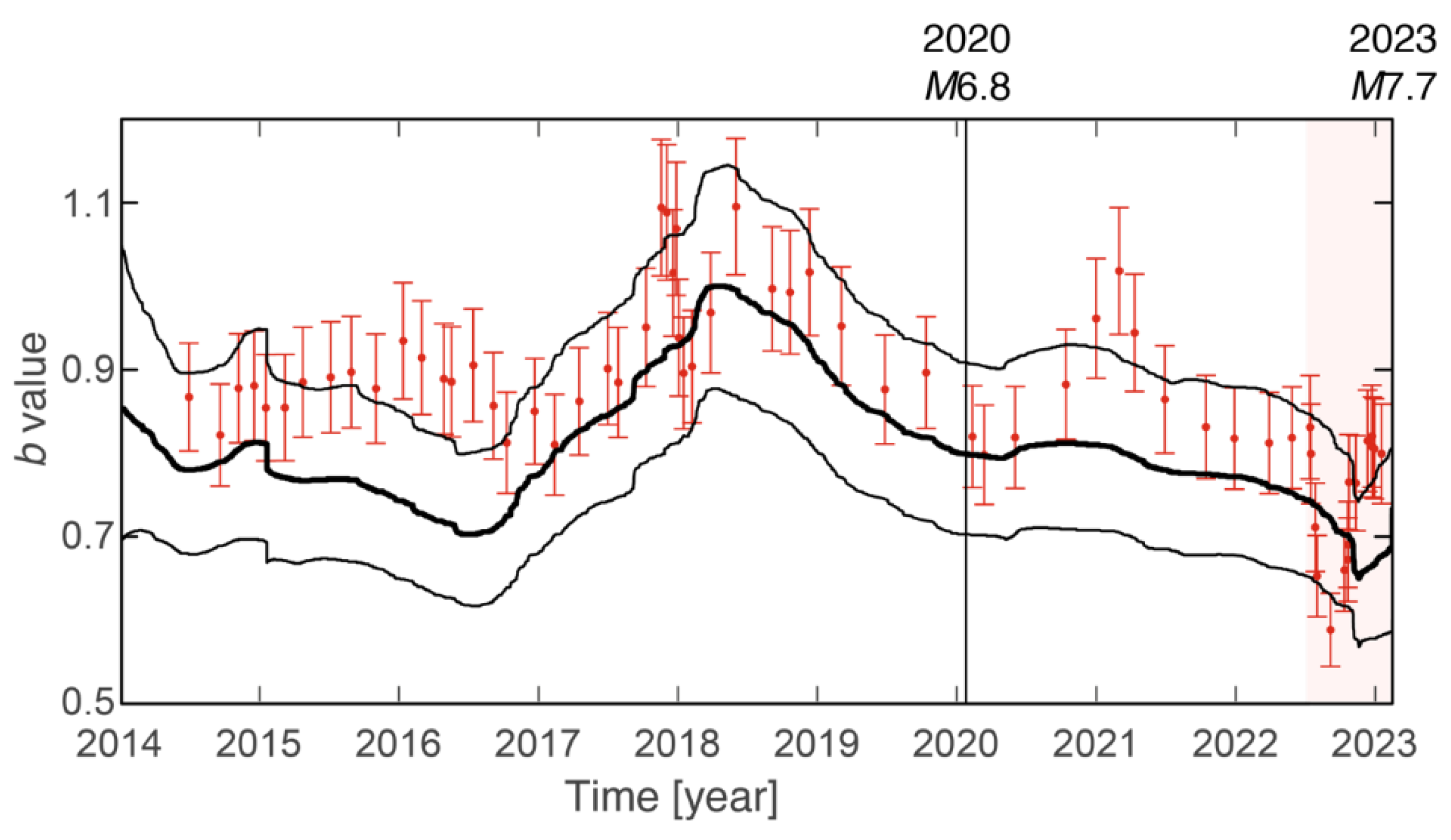

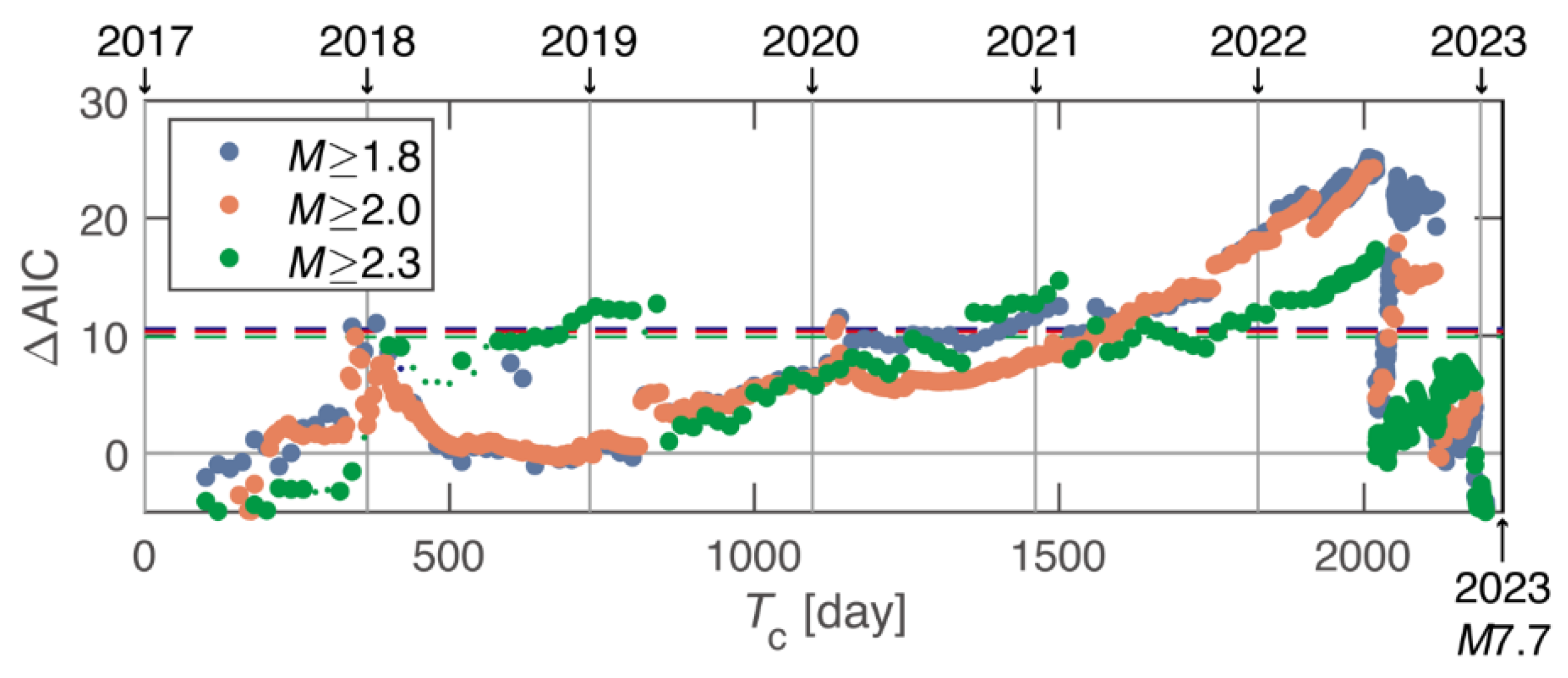

- Seismicity transients began in mid-2022 within 50 km of the future M7.7 epicenter. We revealed that the occurrence rate after mid-2022 was significantly larger than that before it, showing seismic activation. Small b-values were observed after the start of activation. The transients reported previously [10,11] were confirmed by our study, which applied the ETAS model and the Bayesian b-value model to events in two different earthquake catalogs.

- Seismicity within 50 km of the future M7.7 epicenter decomposed into two types of activity: background and clustering. The parameter representing background activity was almost constant over time while that representing clustering activity was smaller before the start of activation than after it. Seismic activation is interpreted as the effect of clustering activity. This was attributed to the emergence of two clusters near the future M7.7 epicenter [10].

- A high-slip area on the segment (referred to as segment 2 in this study) from which the M7.7 rupture started, overlaps with seismicity after the start of activation. This seismicity mostly consisted of events of the cluster displaying low b-values. A similar result was observed for the 2011 Tohoku megaquake [30], where a correlation between areas of low b-values and areas of large co-seismic displacement was shown. A cluster of high b-values that emerged in 2017-2018 overlapped with a low-slip area on the same segment.

- Seismicity following the 2020 M6.8 quake suggests that the south end of the M6.8 rupture was close to the north end of the M7.7 rupture. There was a lack of post-M7.5-quake seismicity at the zone of increase in Coulomb stress imparted by the doublet quakes beyond the north end of the M7.7 rupture, noting that this area, which lacked seismicity, closely matched the area of the 2020 M6.8 rupture. Our result is consistent with a previous finding [5].

- Locations of the two M6-class quakes around the north and south ends of the M7.7-quake rupture were in relatively high-stress regions compared with the surrounding ones, as implied by the b-value and Coulomb-stress analyses. The region around the hypocenters of the M6-class quakes became closer to failure by the doublet quakes. A similar result was obtained when adding the 2020 M6.8 fault to source faults of Coulomb stress changes.

- The decay of seismic activity with time after the M7.7 quake around the causative faults was well modeled by the standard (single) ETAS model, indicating no pronounced activation or quiescence. This decay also followed the OU relation. Our estimation of the duration of the post-doublet-quake sequence was 1-2×103 days (2.7-5.5 years), a longer duration than that proposed by an earlier study [5]. The difference between the present study and the previous study emerged from the fact that the former used events within 618 days since the M7.7 quake while the latter used events within about 100 days.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFAD | Disaster and Emergency Management Authority |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| EAFZ | East Anatolian fault zone |

| ETAS | Epidemic-Type Aftershock Sequence |

| GR | Gutenberg-Richter |

| NAFZ | North Anatolian fault zone |

| NP | nodal plane |

| OU | Omori-Utsu |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

References

- USGS The 2023 Kahramanmaraş, Turkey, Earthquake Sequence. 2024. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/storymap/index-turkey2023.html (Accessed on Feb. 15, 2025).

- USGS M7.8-Pazarcik earthquake, Kahramanmaras earthquake sequence. 2023. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us6000jllz/executive (Accessed on Feb. 15, 2025).

- USGS M7.5-Elbistan earthquake, Kahramanmaras earthquake sequence. 2023. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us6000jlqa/executive (Accessed on Feb. 15, 2025).

- USGS M6.7-13 km N of Doğanyol, Turkey. 2020. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us60007ewc/executive (Accessed on Feb. 15, 2025).

- Toda, S.; Stein, R. The role of stress transfer in rupture nucleation and inhibition in the 2023 Kahramanmaraş, Türkiye, sequence, and a one-year earthquake forecast. Seismological Research Letters 2024, 95(2A), 596-606. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, C.; Dal Zilio, L.; Cao, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, G.; Göğüş O.H.; Zhang, H.; Shi, Y. Decoding Stress Patterns of the 2023 Türkiye-Syria Earthquake Doublet. Journal of Geophysical Research 2024, 129(10), e2024JB029213. [CrossRef]

- Toda, S.; Stein, R.S.; Özbakir, A.D.; Gonzalez-Huizar, H.; Sevilgen, V.; Lotto, G.; Sevilgen, S. Stress change calculations provide clues to aftershocks in 2023 Türkiye earthquakes. Temblor 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Munekane, H.; Kuwahara, M.; Furui, H. Insights on the 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquake, Turkey, from InSAR: fault locations, rupture styles and induced deformation. Geophysical Journal International 2024, 236(2), 1068-1088. [CrossRef]

- Ren, C. et al. Supershear triggering and cascading fault ruptures of the 2023 Kahramanmaraş, Türkiye, earthquake doublet. Science 2024, 383(6680), 305-311. [CrossRef]

- Kwiatek, G.; Martínez-Garzón, P.; Becker, D.; Dresen, G.; Cotton, F.; Beroza, G.C.; Acarel, D.; Ergintav, S.; Bohnhoff, M. Months-long seismicity transients preceding the 2023 MW 7.8 Kahramanmaraş earthquake, Türkiye. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 7534. [CrossRef]

- Över, S.; Demirci, A.; Özden, S. Tectonic implications of the February 2023 Earthquakes (Mw7.7, 7.6 and 6.3) in south-eastern Türkiye. Tectonophysics 2023, 866, 230058. [CrossRef]

- Gutenberg, B.; Richter, C.F. Frequency of earthquakes in California. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 1944, 34(4), 185-188. [CrossRef]

- USGS M6.3-2 km NNW of Uzunbağ, Turkey. 2023. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us6000jqcn/executive (Accessed on Feb. 15, 2025).

- USGS M6.0-19 km W of Doğanyol, Turkey. 2024. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us6000nyzk/executive (Accessed on Feb. 15, 2025).

- Utsu, T. A statistical study on the occurrence of aftershocks. Geophysical Magazine 1961, 30(4), 521-605.

- Lomax, A. Precise, NLL-SSST-coherence hypocenter catalog for the 2023 Mw 7.8 and Mw 7.6 SE Turkey earthquake sequence. 2023. https://zenodo.org/records/8089273 (Accessed on Feb. 15, 2025).

- Ogata, Y., Statistical models for earthquake occurrences and residual analysis for point processes. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1988, 83, 9-27. [CrossRef]

- Dieterich, J. 1994. A constitutive law for rate of earthquake production and its application to earthquake clustering. Journal of Geophysical Research 1994, 99(B2), 2601-2618. [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 1974, 19(6), 716-723. [CrossRef]

- Ogata, Y.; Tsuruoka, H. Statistical monitoring of aftershock sequences: a case study of the 2015 Mw7.8 Gorkha, Nepal, earthquake. Earth, Planets and Space 2016, 68, 44. [CrossRef]

- Wiemer, S. A software package to analyze seismicity: ZMAP. Seismological Research Letters 2012, 72(3), 373-382. [CrossRef]

- Woessner, J.; Wiemer, S. Assessing the quality of earthquake catalogues: estimating the magnitude of completeness and its uncertainty. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2005, 95, 684-698. [CrossRef]

- Nanjo, K.Z.; Yoshida, A. A b map implying the first eastern rupture of the Nankai Trough earthquakes. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 1117. [CrossRef]

- Kumazawa, T.; Ogata, Y.; Tsuruoka, H. Characteristics of seismic activity before and after the 2018 M6.7 Hokkaido Eastern Iburi earthquake. Earth, Planets and Space 2019. 71, 130. [CrossRef]

- Nanjo, K.Z. Were changes in stress state responsible for the 2019 Ridgecrest, California, earthquakes? Nature Communications 2020, 11, 3082. [CrossRef]

- Scholz, C.H. The frequency-magnitude relation of microfracturing in rock and its relation to earthquakes. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 1968, 58(1), 399-415. [CrossRef]

- Lei, X. How do asperities fracture? An experimental study of unbroken asperities. Earth Planetary Science Letters 2003, 213(3-4), 347-359. [CrossRef]

- Goebel, T.H.W.; Schorlemmer, D.; Becker, T.W.; Dresen, G.; Sammis, C.G. Acoustic emissions document stress changes over many seismic cycles in stick-slip experiments. Geophysical Research Letters 2013, 40, 2049-2054. [CrossRef]

- Tormann, T.; Enescu, B.; Woessner, J.; Wiemer, S. Randomness of megathrust earthquakes implied by rapid stress recovery after the Japan earthquake. Nature Geoscience 2015, 8, 152-158. [CrossRef]

- Nanjo K.Z., Hirata, N.; Obara, K.; Kasahara, K. Decade-scale decrease in b value prior to the M9-class 2011 Tohoku and 2004 Sumatra quakes. Geophysical Research Letters 2012, 39(20), L20304. [CrossRef]

- Schurr, B. et al. Gradual unlocking of plate boundary controlled initiation of the 2014 Iquique earthquake. Nature 2014, 512, 299-302. [CrossRef]

- Ito, R; Kaneko, Y. Physical mechanism for a temporal decrease of the Gutenberg-Richter b-value prior to a large earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research 2023, 128(12), e2023JB027413. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Stein, R.S. Stress triggering in thrust and subduction earthquakes, and stress interaction between the southern San Andreas and nearby thrust and strike-slip faults. Journal of Geophysical Research 2024, 109, B02303. [CrossRef]

- Toda, S.; Stein, R.S.; Richards-Dinger, K.; Bozkurt, S. Forecasting the evolution of seismicity in southern California: Animations built on earthquake stress transfer. Journal of Geophysical Research 2005, 110, B05S16. [CrossRef]

- Storchak, D.A.; Di Giacomo, D.; Bondár, I.; Engdahl, E.R.; Harris, J.; Lee, W.H.K.; Villaseñor, A.; Bormann, P. Public release of the ISC-GEM Global Instrumental Earthquake Catalogue (1900-2009). Seismological Research Letters 2013, 84(5), 810-815. [CrossRef]

- Storchak, D.A.; Di Giacomo, D.; Engdahl, E.R.; Harris, J., Bondár, I., Lee, W.H.K., Bormann, P.; Villaseñor, A. The ISC-GEM Global Instrumental Earthquake Catalogue (1900-2009): Introduction. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 2015, 239, 48-63. [CrossRef]

- Di Giacomo, D.; Engdahl, E.R.; Storchak, D.A. The ISC-GEM Earthquake Catalogue (1904–2014): status after the Extension Project, Earth System Science Data 2018, 10, 1877-1899. [CrossRef]

- International Seismological Centre. ISC-GEM Earthquake Catalogue. 2022. [CrossRef]

- USGS Earthquake Hazards Program. Advanced National Seismic System (ANSS) Comprehensive Catalog of Earthquake Events and Products: Various. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Lomax, A.; Savvaidis, A. High-precision earthquake location using source-specific station terms and inter-event waveform similarity. Journal of Geophysical Research 2022, 127(1), e2021JB023190. [CrossRef]

- Lomax, A.; Henry, P. Major California faults are smooth across multiple scales at seismogenic depth. Seismica 2023, 2(1), 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Melgar, D. et al. Sub- and super-shear ruptures during the 2023 Mw 7.8 and Mw 7.6 earthquake doublet in SE Türkiye. Seismica 2023, 2(3), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Kumazawa, T.; Ogata, Y.; Tsuruoka, H. Measuring seismicity diversity and anomalies by point process models: case studies before and after the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquakes in Kyushu, Japan. Earth, Planets and Space 2017, 69, 169. [CrossRef]

- Nanjo, K.Z.; Yukutake, Y.; Kumazawa, T. Activated volcanism of Mount Fuji by the 2011 Japanese large earthquakes. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 10562. [CrossRef]

- Ogata, Y. Detection of precursory relative quiescence before great earthquakes through a statistical model. Journal of Geophysical Research 1992, 97, 19,845-19,871. [CrossRef]

- Kumazawa, T.; Ogata, Y. Quantitative description of induced seismic activity before and after the 2011 Tohoku-Oki Earthquake by non-stationary ETAS models. Journal of Geophysical Research 2013, 118, 6165-6182. [CrossRef]

- Kumazawa, T.; Ogata, Y.; Kimura, K.; Maeda, K.; Kobayashi, A. Background rates of swarm earthquakes that are synchronized with volumetric strain changes. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2016, 442, 51-60. [CrossRef]

- Schorlemmer, D.; Wiemer, S.; Wyss, M. Earthquake statistics at Parkfield: 1. Stationarity of b values. Journal of Geophysical Research 2024, 109, B12307. [CrossRef]

- Shimazaki, K. The almighty earthquake. Seismological Research Letters 1999, 70(2), 147-148. [CrossRef]

- Main, I.; Li, L.; McCloskey, J.; Naylor, M. Effect of the Sumatran mega-earthquake on the global magnitude cut-off and event rate. Nature Geoscience 2008, 1, 142. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, T.; Geist, E.L.; Console, R; Carluccio, R. Characteristic earthquake magnitude frequency distributions on faults calculated from consensus data in California, Journal of Geophysical Research 2018, 123(12), 10,761-10,784. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.P., Coppersmith, K. J. Fault behavior and characteristic earthquakes: examples from Wasatch and San Andreas fault zones. Journal of Geophysical Research 1984, 89, 5681-5698. [CrossRef]

- Emre, Ö.; Duman, T.Y.; Olgun, S.; Elmaci, H.; Özalp, S. 1:250,000 Scale Active Fault Map Series of Turkey, Gaziantep (NJ 37-9) Quadrangle. Serial Number: 38, General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration, Ankara-Turkey 2012.

- Wessel, P.; Smith, W.H.F.; Scharroo, R.; Luis, J.F.; Wobbe, F. Generic Mapping Tools: improved version released. EOS, Transactions, AGU 2013, 94(45), 409-410. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).