Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Search Methods

3. Potential Mechanism of CMVD After AMI

3.1. Ischemia, Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury and Endothelial Dysfunction

3.2. Inflammation

3.3. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and Distal Embolization

3.4. Patient’s-Specific Factors

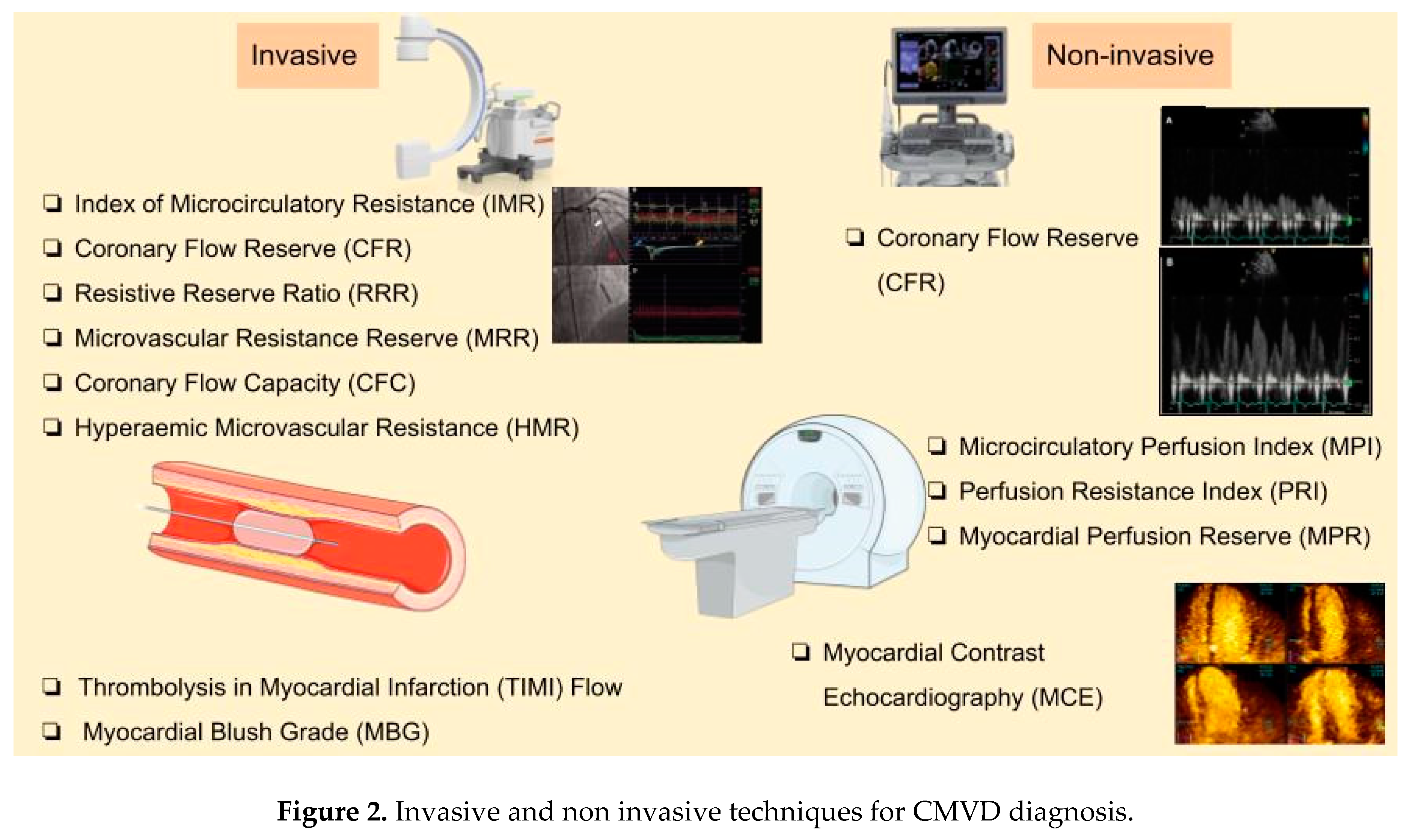

4. Diagnostic Methods

| Method (cut-off value) | Physiology | Prognostic value | Comments (pros & Cons) |

| Invasive methods | |||

| TIMI flow (≤2) | Qualitative index of blood flow of the epicardial coronary arteries | Correlation with increased in-hospital mortality | Pros: cost-free, simple technique, without hyperemic provocation Cons: may not capture the adequacy of myocardial perfusion, low accuracy and sensitivity, interobserver and intra-observer variability |

| MBG (≤1) | Qualitative index of myocardial perfusion, grading the intensity of contrast within the myocardium | larger infarct sizes, adverse ventricular remodelling, worse post-MI outcomes, increased hospitalisation for HF | Pros: cost-free, simple technique Cons: low accuracy, limited sensitivity, interobserver and intra-observer variability |

| CTFC (unknown) | microvascular resistance during hyperaemia | Independent association with in-hospital mortality | Cons: low accuracy, limited sensitivity, interobserver and intra-observer variability |

| IMR (>25, also 23 and 40 are proposed as cut-offs) | measurement of pressure and temperature in the coronary vessels | Association with adverse clinical events, independent predictor of MACE in 4 years | Pros: can be used as a stratification tool, has the largest body of evidence, objective measurement Cons: required hyperaemia, variability |

| CFR (<2) | Ratio: maximal coronary blood flow during hyperaemia / resting blood flow; using pressure-temperature sensor guidewire | Association with higher in-hospital mortality | Pros: Cons: cannot distinguish impairment between macro- and microcirculation, not independent predictor in STEMI, limited utility, requires hyperaemia, high variability, special equipment |

| CFR (<2.1) | Ratio: maximal coronary blood flow during hyperaemia / resting blood flow; using Doppler method | Association with increased cardiac mortality | Cons: cannot distinguish impairment between macro- and microcirculation, influenced by systemic hemodynamic changes |

| RRR (≤1.5, also 1.7 and 2.62 are proposed as cut-offs) | Functional reserve of the coronary microvasculature | In combination with IMR association with MVO, myocardial haemorrhage, infarct size and clinical outcomes | Pros: useful in identifying reduced microvascular responsiveness post-MI Cons: required hyperaemia |

| CFC (<2.8) | Combination of absolute flow measurements and CFR | Improves risk stratification following reperfusion, association with increased MACE | Pros: overcomes the limitations of CFR Cons: requires advanced imaging and technical expertise |

| HMR (≥3) |

Ratio: hyperaemic mean distal pressure /Doppler-derived hyperaemic average peak velocity | Prediction of adverse clinical outcomes | Pros: specific to microvasculature, independent of systemic factors Cons: required precise measurements and pharmacological hyperaemia, technically challenging |

| Non-invasive methods | |||

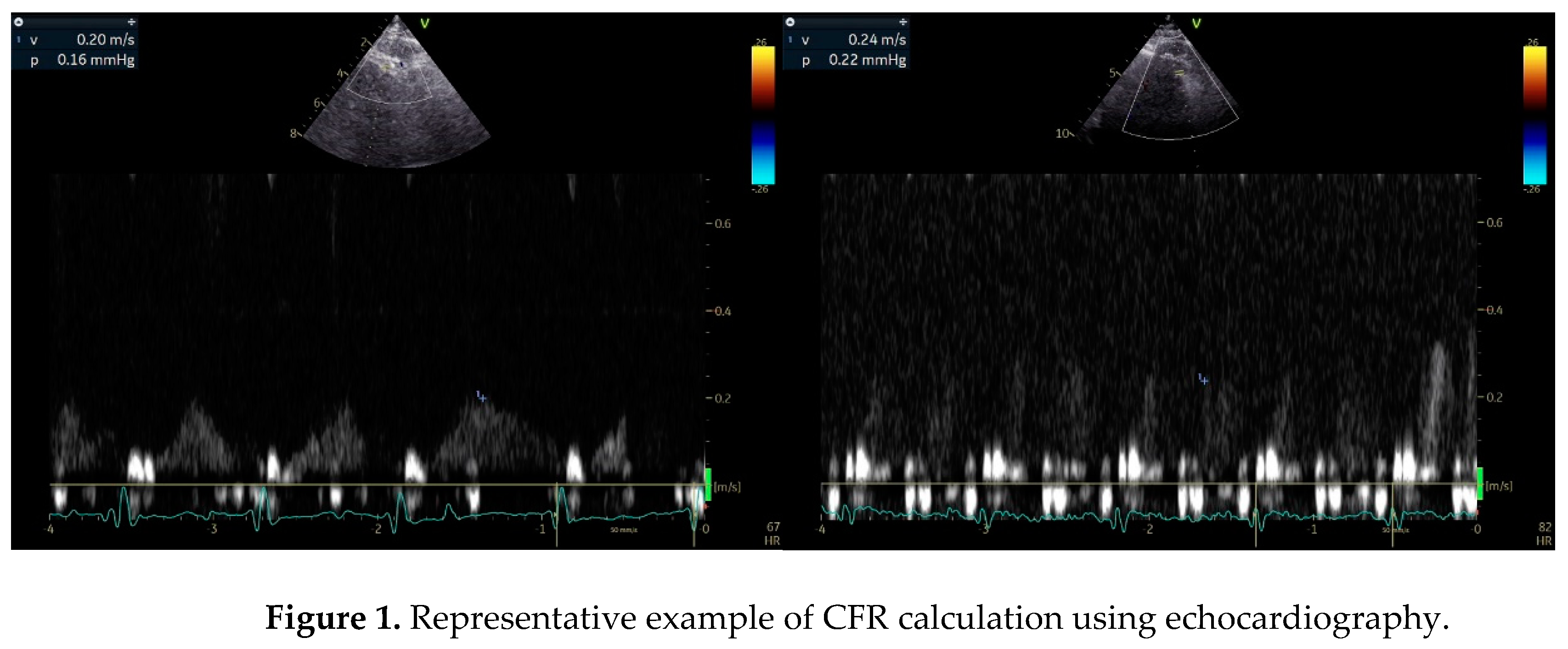

| CFR (<2) | Ratio: maximal coronary blood flow during hyperaemia / resting blood flow; using Doppler method | Reduced survival | Pros: easily accessible with echocardiography Cons: cannot distinguish microvascular from macrovascular obstruction, discrepancy between CFR und FFR |

| MCE | Myocardial contrast signal is calculated, which reflects the blood flow | Prognostic data not yet available | Cons: operator dependency, uncertain reproducibility, low sensitivity, reimbursement issues |

| CMR: MVO (≥2.6), MPI, MRPI | Direct visualization of myocardial perfusion and MVO, | MVO≥2.6: strong predictor of MACE, death, HF hospitalization | Pros: safe, significant with invasive-derived measurements Cons: Claustrophobia, high cost |

| PET: CFR (<2.6, also 2.0 is proposed as cut-off) | Detection no reflow phenomenon | increased long-term cardiovascular events und mortality | Pros: quantitative assessment, high sensitivity Cons: reduced availability, cost |

4.1. Angiography-Based Techniques

Pressure-Wire-Based Techniques

Index of Microcirculatory Resistance (IMR)

Coronary Flow Reserve (CFR)

Resistive Reserve Ratio (RRR)

Microvascular Resistance Reserve (MRR)

Invasive Doppler-Based Methods

4.2. Non-Invasive Methods

Stress Echocardiography (SE)

Myocardial Perfusion in Stress Echocardiography

CMR Imaging

5. Prognostic Value of CMVD

6. Discussion and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 18F-FDG | Fluorodeoxyglucose F-18 |

| AHA/ACC | American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology |

| ACS | Acute Coronary Syndrome |

| AMI | Acute Myocardial Infarction |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| CAD | Coronary Artery Disease |

| CDKN2B-AS1 | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2B Antisense RNA 1 |

| CFC | Coronary Flow Capacity |

| CFR | Coronary Flow Reserve |

| CFVR | Coronary Flow Velocity Reserve |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CMVD | Coronary Microvascular Disease |

| CMR | Cardiac Magnetic Resonance |

| CTFC | Corrected TIMI Frame Count |

| DAMPs | Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| DE-CMR | Delayed Enhancement Cardiac Magnetic Resonance |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| FFR | Fractional Flow Reserve |

| FPP | First-Pass Perfusion |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| HMR | Hyperemic Microvascular Resistance |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IMH | Intramyocardial Haemorrhage |

| IMR | Index of Microcirculatory Resistance |

| IMRangio | Angiography-Derived Index of Microcirculatory Resistance |

| INOCA | Ischemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries |

| IRA | Infarct-Related Artery |

| LAD | Left Anterior Descending Artery |

| LGE | Late Gadolinium Enhancement |

| LV | Left Ventricular |

| LVEF | Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction |

| MACE | Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events |

| MBG | Myocardial Blush Grade |

| MCE | Myocardial Contrast Echocardiography |

| MINOCA | Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructed Coronary Arteries |

| MPI | Microcirculatory Perfusion Index |

| MPRI | Myocardial Perfusion Reserve Index |

| MRR | Microvascular Resistance Reserve |

| MVO | Microvascular Obstruction |

| MYH15 | Myosin Heavy Chain 15 |

| NH-IMRangio | Non-Hyperemic Angiography-Derived Index of Microcirculatory Resistance |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NT5E | 5′-Nucleotidase Ecto |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PCI | Percutaneous Coronary Intervention |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| PPCI | Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention |

| QFR | Quantitative Flow Ratio |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RRR | Resistive Reserve Ratio |

| SE | Stress Echocardiography |

| SPECT | Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography |

| STEMI | ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction |

| STR | ST-segment Resolution |

| TDE | Transthoracic Doppler Echocardiography |

| TIMI | Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| VEGFA | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A |

References

- Pries, A.R.; Badimon, L.; Bugiardini, R.; Camici, P.G.; Dorobantu, M.; Duncker, D.J.; Escaned, J.; Koller, A.; Piek, J.J.; De Wit, C. Coronary Vascular Regulation, Remodelling, and Collateralization: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications on Behalf of the Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology and Microcirculation. Eur Heart J 2015, 36, 3134–3146. [CrossRef]

- Robbers, L.F.H.J.; Eerenberg, E.S.; Teunissen, P.F.A.; Jansen, M.F.; Hollander, M.R.; Horrevoets, A.J.G.; Knaapen, P.; Nijveldt, R.; Heymans, M.W.; Levi, M.M.; et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Defined Areas of Microvascular Obstruction after Acute Myocardial Infarction Represent Microvascular Destruction and Haemorrhage. European Heart Journal 2013, 34, 2346–2353. [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.H.; Dai, N.; Li, Y.; Kim, J.; Shin, D.; Lee, S.H.; Joh, H.S.; Kim, H.K.; Jeon, K.-H.; Ha, S.J.; et al. Functional Coronary Angiography–Derived Index of Microcirculatory Resistance in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2021, 14, 1670–1684. [CrossRef]

- Kunadian, V.; Chieffo, A.; Camici, P.G.; Berry, C.; Escaned, J.; Maas, A.H.E.M.; Prescott, E.; Karam, N.; Appelman, Y.; Fraccaro, C.; et al. An EAPCI Expert Consensus Document on Ischaemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries in Collaboration with European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology & Microcirculation Endorsed by Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group. European Heart Journal 2020, 41, 3504–3520. [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.; Stiermaier, T.; Fuernau, G.; Pöss, J.; De Waha-Thiele, S.; Desch, S.; Thiele, H.; Eitel, I. Impact of Direct Stenting on Myocardial Injury Assessed by Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Prognosis in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. International Journal of Cardiology 2019, 283, 88–92. [CrossRef]

- El Aidi, H.; Adams, A.; Moons, K.G.M.; Den Ruijter, H.M.; Mali, W.P.Th.M.; Doevendans, P.A.; Nagel, E.; Schalla, S.; Bots, M.L.; Leiner, T. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings and the Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Recent Myocardial Infarction or Suspected or Known Coronary Artery Disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2014, 63, 1031–1045. [CrossRef]

- Canu, M.; Khouri, C.; Marliere, S.; Vautrin, E.; Piliero, N.; Ormezzano, O.; Bertrand, B.; Bouvaist, H.; Riou, L.; Djaileb, L.; et al. Prognostic Significance of Severe Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction Post-PCI in Patients with STEMI: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268330. [CrossRef]

- Beltrame, J.F.; Crea, F.; Camici, P. Advances in Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction. Heart, Lung and Circulation 2009, 18, 19–27. [CrossRef]

- Niccoli, G.; Scalone, G.; Lerman, A.; Crea, F. Coronary Microvascular Obstruction in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Eur Heart J 2016, 37, 1024–1033. [CrossRef]

- Galli, M.; Niccoli, G.; De Maria, G.; Brugaletta, S.; Montone, R.A.; Vergallo, R.; Benenati, S.; Magnani, G.; D’Amario, D.; Porto, I.; et al. Coronary Microvascular Obstruction and Dysfunction in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Nat Rev Cardiol 2024, 21, 283–298. [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, J.S.; Jaffe, A.S.; Chaitman, B.R.; Bax, J.J.; Morrow, D.A.; White, H.D. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2018, 72, 2231–2264. [CrossRef]

- Heusch, G. Myocardial Ischaemia–Reperfusion Injury and Cardioprotection in Perspective. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020, 17, 773–789. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.-H.; Ruze, A.; Zhao, L.; Li, Q.-L.; Tang, J.; Xiefukaiti, N.; Gai, M.-T.; Deng, A.-X.; Shan, X.-F.; Gao, X.-M. The Role and Mechanisms of Microvascular Damage in the Ischemic Myocardium. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2023, 80, 341. [CrossRef]

- Heusch, G. Treatment of Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Ischemic and Pharmacological Postconditioning. In Comprehensive Physiology; Terjung, R., Ed.; Wiley, 2015; pp. 1123–1145 ISBN 978-0-470-65071-4.

- Maslov, L.N.; Popov, S.V.; Naryzhnaya, N.V.; Mukhomedzyanov, A.V.; Kurbatov, B.K.; Derkachev, I.A.; Boshchenko, A.A.; Khaliulin, I.; Prasad, N.R.; Singh, N.; et al. The Regulation of Necroptosis and Perspectives for the Development of New Drugs Preventing Ischemic/Reperfusion of Cardiac Injury. Apoptosis 2022, 27, 697–719. [CrossRef]

- Doherty, D.J.; Sykes, R.; Mangion, K.; Berry, C. Predictors of Microvascular Reperfusion After Myocardial Infarction. Curr Cardiol Rep 2021, 23, 21. [CrossRef]

- Reffelmann, T.; Kloner, R.A. The No-Reflow Phenomenon: A Basic Mechanism of Myocardial Ischemia and Reperfusion. Basic Res Cardiol 2006, 101, 359–372. [CrossRef]

- Konijnenberg, L.S.F.; Damman, P.; Duncker, D.J.; Kloner, R.A.; Nijveldt, R.; Van Geuns, R.-J.M.; Berry, C.; Riksen, N.P.; Escaned, J.; Van Royen, N. Pathophysiology and Diagnosis of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Cardiovascular Research 2020, 116, 787–805. [CrossRef]

- Dörge, H.; Schulz, R.; Belosjorow, S.; Post, H.; Van De Sand, A.; Konietzka, I.; Frede, S.; Hartung, T.; Vinten-Johansen, J.; Youker, K.A.; et al. Coronary Microembolization: The Role of TNF- α in Contractile Dysfunction. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2002, 34, 51–62. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, B.; Peng, W.; Xu, Z. Protective Effect of Glycyrrhizin on Coronary Microembolization-induced Myocardial Dysfunction in Rats. Pharmacology Res & Perspec 2021, 9, e00714. [CrossRef]

- Loubeyre, C.; Morice, M.-C.; Lefèvre, T.; Piéchaud, J.-F.; Louvard, Y.; Dumas, P. A Randomized Comparison of Direct Stenting with Conventional Stent Implantation in Selected Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2002, 39, 15–21. [CrossRef]

- Selvanayagam, J.B.; Cheng, A.S.H.; Jerosch-Herold, M.; Rahimi, K.; Porto, I.; Van Gaal, W.; Channon, K.M.; Neubauer, S.; Banning, A.P. Effect of Distal Embolization on Myocardial Perfusion Reserve After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Perfusion Study. Circulation 2007, 116, 1458–1464. [CrossRef]

- Kleinbongard, P.; Heusch, G. A Fresh Look at Coronary Microembolization. Nat Rev Cardiol 2022, 19, 265–280. [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.C. CMR of Microvascular Obstruction and Hemorrhage in Myocardial Infarction. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 2012, 14, 72. [CrossRef]

- Heusch, G.; Gersh, B.J. The Pathophysiology of Acute Myocardial Infarction and Strategies of Protection beyond Reperfusion: A Continual Challenge. Eur Heart J 2016, ehw224. [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, S.; Cilluffo, R.; Best, P.J.M.; Atkinson, E.J.; Aoki, T.; Cunningham, J.M.; De Andrade, M.; Choi, B.-J.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms Associated with Abnormal Coronary Microvascular Function. Coronary Artery Disease 2014, 25, 281–289. [CrossRef]

- Iwakura, K.; Ito, H.; Ikushima, M.; Kawano, S.; Okamura, A.; Asano, K.; Kuroda, T.; Tanaka, K.; Masuyama, T.; Hori, M.; et al. Association between Hyperglycemia and the No-Reflow Phenomenon Inpatients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2003, 41, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska, E.; Narkiewicz, K. Hypertension and Dyslipidemia: The Two Partners in Endothelium-Related Crime. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2023, 25, 605–612. [CrossRef]

- Ferdinandy, P.; Andreadou, I.; Baxter, G.F.; Bøtker, H.E.; Davidson, S.M.; Dobrev, D.; Gersh, B.J.; Heusch, G.; Lecour, S.; Ruiz-Meana, M.; et al. Interaction of Cardiovascular Nonmodifiable Risk Factors, Comorbidities and Comedications With Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury and Cardioprotection by Pharmacological Treatments and Ischemic Conditioning. Pharmacological Reviews 2023, 75, 159–216. [CrossRef]

- Scarsini, R.; Portolan, L.; Della Mora, F.; Marin, F.; Mainardi, A.; Ruzzarin, A.; Levine, M.B.; Banning, A.P.; Ribichini, F.; Garcia Garcia, H.M.; et al. Angiography-Derived and Sensor-Wire Methods to Assess Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2023, 16, 965–981. [CrossRef]

- The TIMI Study Group* The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Trial: Phase I Findings. N Engl J Med 1985, 312, 932–936. [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, R.; Charron, T.; Puley, G.; Dick, A.; Strauss, B.H. Microvascular Obstruction and the No-Reflow Phenomenon After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Circulation 2008, 117, 3152–3156. [CrossRef]

- Marra, M.P.; Corbetti, F.; Cacciavillani, L.; Tarantini, G.; Ramondo, A.B.; Napodano, M.; Basso, C.; Lacognata, C.; Marzari, A.; Maddalena, F.; et al. Relationship between Myocardial Blush Grades, Staining, and Severe Microvascular Damage after Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. American Heart Journal 2010, 159, 1124–1132. [CrossRef]

- Ohara, Y. Relation between the TIMI Frame Count and the Degree of Microvascular Injury after Primary Coronary Angioplasty in Patients with Acute Anterior Myocardial Infarction. Heart 2005, 91, 64–67. [CrossRef]

- Kest, M.; Ágoston, A.; Szabó, G.T.; Kiss, A.; Üveges, Á.; Czuriga, D.; Komócsi, A.; Hizoh, I.; Kőszegi, Z. Angiography-Based Coronary Microvascular Assessment with and without Intracoronary Pressure Measurements: A Systematic Review. Clin Res Cardiol 2024, 113, 1609–1621. [CrossRef]

- Fearon, W.F.; Balsam, L.B.; Farouque, H.M.O.; Robbins, R.C.; Fitzgerald, P.J.; Yock, P.G.; Yeung, A.C. Novel Index for Invasively Assessing the Coronary Microcirculation. Circulation 2003, 107, 3129–3132. [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.K.C.; Yeung, A.C.; Fearon, W.F. Invasive Assessment of the Coronary Microcirculation: Superior Reproducibility and Less Hemodynamic Dependence of Index of Microcirculatory Resistance Compared With Coronary Flow Reserve. Circulation 2006, 113, 2054–2061. [CrossRef]

- Okura, H.; Fuyuki, H.; Kubo, T.; Iwata, K.; Taguchi, H.; Toda, I.; Yoshikawa, J. Noninvasive Diagnosis of Ischemic and Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy Using Coronary Flow Velocity Measurements of the Left Anterior Descending Coronary Artery by Transthoracic Doppler Echocardiography. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography 2006, 19, 552–558. [CrossRef]

- Knuuti, J.; Wijns, W.; Saraste, A.; Capodanno, D.; Barbato, E.; Funck-Brentano, C.; Prescott, E.; Storey, R.F.; Deaton, C.; Cuisset, T.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Coronary Syndromes. European Heart Journal 2020, 41, 407–477. [CrossRef]

- Gulati, M.; Levy, P.D.; Mukherjee, D.; Amsterdam, E.; Bhatt, D.L.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blankstein, R.; Boyd, J.; Bullock-Palmer, R.P.; Conejo, T.; et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2021, 144. [CrossRef]

- Carrick, D.; Haig, C.; Ahmed, N.; Carberry, J.; Yue May, V.T.; McEntegart, M.; Petrie, M.C.; Eteiba, H.; Lindsay, M.; Hood, S.; et al. Comparative Prognostic Utility of Indexes of Microvascular Function Alone or in Combination in Patients With an Acute ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2016, 134, 1833–1847. [CrossRef]

- De Waard, G.A.; Hollander, M.R.; Teunissen, P.F.A.; Jansen, M.F.; Eerenberg, E.S.; Beek, A.M.; Marques, K.M.; Van De Ven, P.M.; Garrelds, I.M.; Danser, A.H.J.; et al. Changes in Coronary Blood Flow After Acute Myocardial Infarction. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2016, 9, 602–613. [CrossRef]

- Maznyczka, A.M.; Oldroyd, K.G.; Greenwood, J.P.; McCartney, P.J.; Cotton, J.; Lindsay, M.; McEntegart, M.; Rocchiccioli, J.P.; Good, R.; Robertson, K.; et al. Comparative Significance of Invasive Measures of Microvascular Injury in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circ: Cardiovascular Interventions 2020, 13, e008505. [CrossRef]

- Toya, T.; Ahmad, A.; Corban, M.T.; Ӧzcan, I.; Sara, J.D.; Sebaali, F.; Escaned, J.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. Risk Stratification of Patients With NonObstructive Coronary Artery Disease Using Resistive Reserve Ratio. JAHA 2021, 10, e020464. [CrossRef]

- Scarsini, R.; De Maria, G.L.; Borlotti, A.; Kotronias, R.A.; Langrish, J.P.; Lucking, A.J.; Choudhury, R.P.; Ferreira, V.M.; Ribichini, F.; Channon, K.M.; et al. Incremental Value of Coronary Microcirculation Resistive Reserve Ratio in Predicting the Extent of Myocardial Infarction in Patients with STEMI. Insights from the Oxford Acute Myocardial Infarction (OxAMI) Study. Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine 2019, 20, 1148–1155. [CrossRef]

- Gallinoro, E.; Candreva, A.; Colaiori, I.; Kodeboina, M.; Fournier, S.; Nelis, O.; Di Gioia, G.; Sonck, J.; Van ’T Veer, M.; Pijls, N.H.J.; et al. Thermodilution-Derived Volumetric Resting Coronary Blood Flow Measurement in Humans. EuroIntervention 2021, 17, e672–e679. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.-Y.; Aldujeli, A.; Haq, A.; Knokneris, A.; Briedis, K.; Hughes, D.; Unikas, R.; Renkens, M.; Revaiah, P.C.; Tobe, A.; et al. The Impact of Microvascular Resistance Reserve on the Outcome of Patients With STEMI. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2024, 17, 1214–1227. [CrossRef]

- Doucette, J.W.; Corl, P.D.; Payne, H.M.; Flynn, A.E.; Goto, M.; Nassi, M.; Segal, J. Validation of a Doppler Guide Wire for Intravascular Measurement of Coronary Artery Flow Velocity. Circulation 1992, 85, 1899–1911. [CrossRef]

- Van De Hoef, T.P.; Bax, M.; Meuwissen, M.; Damman, P.; Delewi, R.; De Winter, R.J.; Koch, K.T.; Schotborgh, C.; Henriques, J.P.S.; Tijssen, J.G.P.; et al. Impact of Coronary Microvascular Function on Long-Term Cardiac Mortality in Patients With Acute ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circ: Cardiovascular Interventions 2013, 6, 207–215. [CrossRef]

- De Waard, G.A.; Fahrni, G.; De Wit, D.; Kitabata, H.; Williams, R.; Patel, N.; Teunissen, P.F.; Van De Ven, P.M.; Umman, S.; Knaapen, P.; et al. Hyperaemic Microvascular Resistance Predicts Clinical Outcome and Microvascular Injury after Myocardial Infarction. Heart 2018, 104, 127–134. [CrossRef]

- Van De Hoef, T.P.; Echavarría-Pinto, M.; Van Lavieren, M.A.; Meuwissen, M.; Serruys, P.W.J.C.; Tijssen, J.G.P.; Pocock, S.J.; Escaned, J.; Piek, J.J. Diagnostic and Prognostic Implications of Coronary Flow Capacity. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2015, 8, 1670–1680. [CrossRef]

- Van Lavieren, M.A.; Stegehuis, V.E.; Bax, M.; Echavarría-Pinto, M.; Wijntjens, G.W.M.; De Winter, R.J.; Koch, K.T.; Henriques, J.P.; Escaned, J.; Meuwissen, M.; et al. Time Course of Coronary Flow Capacity Impairment in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. European Heart Journal. Acute Cardiovascular Care 2021, 10, 516–522. [CrossRef]

- Wijnbergen, I.; Van ’T Veer, M.; Lammers, J.; Ubachs, J.; Pijls, N.H.J. Absolute Coronary Blood Flow Measurement and Microvascular Resistance in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction in the Acute and Subacute Phase. Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine 2016, 17, 81–87. [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, K.; Karamasis, G.V.; Davies, J.R.; Alsanjari, O.; Tang, K.H.; Gamma, R.A.; Kelly, P.R.; Pijls, N.H.J.; Keeble, T.R.; Clesham, G.J. Absolute Microvascular Resistance by Continuous Thermodilution Predicts Microvascular Dysfunction after ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. International Journal of Cardiology 2020, 319, 7–13. [CrossRef]

- Kogame, N.; Ono, M.; Kawashima, H.; Tomaniak, M.; Hara, H.; Leipsic, J.; Andreini, D.; Collet, C.; Patel, M.R.; Tu, S.; et al. The Impact of Coronary Physiology on Contemporary Clinical Decision Making. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2020, 13, 1617–1638. [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.; Westra, J.; Yang, J.; Von Birgelen, C.; Ferrara, A.; Pellicano, M.; Nef, H.; Tebaldi, M.; Murasato, Y.; Lansky, A.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Fast Computational Approaches to Derive Fractional Flow Reserve From Diagnostic Coronary Angiography. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2016, 9, 2024–2035. [CrossRef]

- Oxford Acute Myocardial Infarction (OXAMI) Study Investigators; De Maria, G.L.; Scarsini, R.; Shanmuganathan, M.; Kotronias, R.A.; Terentes-Printzios, D.; Borlotti, A.; Langrish, J.P.; Lucking, A.J.; Choudhury, R.P.; et al. Angiography-Derived Index of Microcirculatory Resistance as a Novel, Pressure-Wire-Free Tool to Assess Coronary Microcirculation in ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2020, 36, 1395–1406. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Peregrina, E.; Garcia-Garcia, H.M.; Sans-Rosello, J.; Sanz-Sanchez, J.; Kotronias, R.; Scarsini, R.; Echavarria-Pinto, M.; Tebaldi, M.; De Maria, G.L. Angiography-derived versus Invasively-determined Index of Microcirculatory Resistance in the Assessment of Coronary Microcirculation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cathet Cardio Intervent 2022, 99, 2018–2025. [CrossRef]

- Parwani, P.; Kang, N.; Safaeipour, M.; Mamas, M.A.; Wei, J.; Gulati, M.; Naidu, S.S.; Merz, N.B. Contemporary Diagnosis and Management of Patients with MINOCA. Curr Cardiol Rep 2023, 25, 561–570. [CrossRef]

- Abreu, J.S.D.; Rocha, E.A.; Machado, I.S.; Parahyba, I.O.; Rocha, T.B.; Paes, F.J.V.N.; Diogenes, T.C.P.; Abreu, M.E.B.D.; Farias, A.G.L.P.; Carneiro, M.M.; et al. Prognostic Value of Coronary Flow Reserve Obtained on Dobutamine Stress Echocardiography and Its Correlation with Target Heart Rate. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia 2017. [CrossRef]

- Simova, I.; National Cardiology Hospital, Sofia, Bulgaria Coronary Flow Velocity Reserve Assessment with Transthoracic Doppler Echocardiography. European Cardiology Review 2015, 10, 12. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.G. MINOCA and INOCA: Role in Heart Failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2023, 20, 139–150. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.; Harbaoui, B.; Van De Hoef, T.P.; Meuwissen, M.; Nijjer, S.S.; Echavarria-Pinto, M.; Davies, J.E.; Piek, J.J.; Lantelme, P. Relationship between FFR, CFR and Coronary Microvascular Resistance – Practical Implications for FFR-Guided Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0208612. [CrossRef]

- Dikic, A.D.; Dedic, S.; Jovanovic, I.; Boskovic, N.; Giga, V.; Nedeljkovic, I.; Tesic, M.; Aleksandric, S.; Cortigiani, L.; Ciampi, Q.; et al. Noninvasive Evaluation of Dynamic Microvascular Dysfunction in Ischemia and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease Patients with Suspected Vasospasm. Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, G.; Janardhanan, R.; Hayat, S.A.; Lim, T.K.; Greaves, K.; Senior, R. Relationship between Myocardial Perfusion with Myocardial Contrast Echocardiography and Function Early after Acute Myocardial Infarction for the Prediction of Late Recovery of Function. International Journal of Cardiology 2010, 140, 169–174. [CrossRef]

- Galiuto, L.; Garramone, B.; Scarà, A.; Rebuzzi, A.G.; Crea, F.; La Torre, G.; Funaro, S.; Madonna, M.; Fedele, F.; Agati, L. The Extent of Microvascular Damage During Myocardial Contrast Echocardiography Is Superior to Other Known Indexes of Post-Infarct Reperfusion in Predicting Left Ventricular Remodeling. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2008, 51, 552–559. [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoneim, S.S.; Dhoble, A.; Bernier, M.; Erwin, P.J.; Korosoglou, G.; Senior, R.; Moir, S.; Kowatsch, I.; Xian-Hong, S.; Muro, T.; et al. Quantitative Myocardial Contrast Echocardiography during Pharmacological Stress for Diagnosis of Coronary Artery Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging 2009, 10, 813–825. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.M.; Schulz-Menger, J.; Holmvang, G.; Kramer, C.M.; Carbone, I.; Sechtem, U.; Kindermann, I.; Gutberlet, M.; Cooper, L.T.; Liu, P.; et al. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Nonischemic Myocardial Inflammation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2018, 72, 3158–3176. [CrossRef]

- Herling De Oliveira, L.L.; Correia, V.M.; Nicz, P.F.G.; Soares, P.R.; Scudeler, T.L. MINOCA: One Size Fits All? Probably Not—A Review of Etiology, Investigation, and Treatment. JCM 2022, 11, 5497. [CrossRef]

- Lubbers, D.D.; Janssen, C.H.C.; Kuijpers, D.; Van Dijkman, P.R.M.; Overbosch, J.; Willems, T.P.; Oudkerk, M. The Additional Value of First Pass Myocardial Perfusion Imaging during Peak Dose of Dobutamine Stress Cardiac MRI for the Detection of Myocardial Ischemia. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2008, 24, 69–76. [CrossRef]

- Tonet, E.; Pompei, G.; Faragasso, E.; Cossu, A.; Pavasini, R.; Passarini, G.; Tebaldi, M.; Campo, G. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction: PET, CMR and CT Assessment. JCM 2021, 10, 1848. [CrossRef]

- Adjedj, J.; Picard, F.; Durand-Viel, G.; Sigal-Cinqualbre, A.; Daou, D.; Diebold, B.; Varenne, O. Coronary Microcirculation in Acute Myocardial Ischaemia: From Non-Invasive to Invasive Absolute Flow Assessment. Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases 2018, 111, 306–315. [CrossRef]

- Mayala, H.A.; Yan, W.; Jing, H.; Shuang-ye, L.; Gui-wen, Y.; Chun-xia, Q.; Ya, W.; Xiao-li, L.; Zhao-hui, W. Clinical Characteristics and Biomarkers of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction and Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease. J Int Med Res 2019, 47, 6149–6159. [CrossRef]

- Flores, C.H.; Díez-Delhoyo, F.; Sanz-Ruiz, R.; Vázquez-Álvarez, M.E.; Tamargo Delpon, M.; Soriano Triguero, J.; Elízaga Corrales, J.; Fernández-Avilés, F.; Gutiérrez Ibañes, E. Microvascular Dysfunction of the Non-Culprit Circulation Predicts Poor Prognosis in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. IJC Heart & Vasculature 2022, 39, 100997. [CrossRef]

- Taqueti, V.R.; Solomon, S.D.; Shah, A.M.; Desai, A.S.; Groarke, J.D.; Osborne, M.T.; Hainer, J.; Bibbo, C.F.; Dorbala, S.; Blankstein, R.; et al. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction and Future Risk of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. European Heart Journal 2018, 39, 840–849. [CrossRef]

- Henriques, J.P.S.; Zijlstra, F.; Van ‘T Hof, A.W.J.; De Boer, M.-J.; Dambrink, J.-H.E.; Gosselink, M.; Hoorntje, J.C.A.; Suryapranata, H. Angiographic Assessment of Reperfusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction by Myocardial Blush Grade. Circulation 2003, 107, 2115–2119. [CrossRef]

- Taqueti, V.R.; Shaw, L.J.; Cook, N.R.; Murthy, V.L.; Shah, N.R.; Foster, C.R.; Hainer, J.; Blankstein, R.; Dorbala, S.; Di Carli, M.F. Excess Cardiovascular Risk in Women Relative to Men Referred for Coronary Angiography Is Associated With Severely Impaired Coronary Flow Reserve, Not Obstructive Disease. Circulation 2017, 135, 566–577. [CrossRef]

- Ćorović, A.; Nus, M.; Mallat, Z.; Rudd, J.H.F.; Tarkin, J.M. PET Imaging of Post-Infarct Myocardial Inflammation. Curr Cardiol Rep 2021, 23, 99. [CrossRef]

- De Waha, S.; Patel, M.R.; Granger, C.B.; Ohman, E.M.; Maehara, A.; Eitel, I.; Ben-Yehuda, O.; Jenkins, P.; Thiele, H.; Stone, G.W. Relationship between Microvascular Obstruction and Adverse Events Following Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: An Individual Patient Data Pooled Analysis from Seven Randomized Trials. European Heart Journal 2017, 38, 3502–3510. [CrossRef]

- Hamirani, Y.S.; Wong, A.; Kramer, C.M.; Salerno, M. Effect of Microvascular Obstruction and Intramyocardial Hemorrhage by CMR on LV Remodeling and Outcomes After Myocardial Infarction. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2014, 7, 940–952. [CrossRef]

- Symons, R.; Pontone, G.; Schwitter, J.; Francone, M.; Iglesias, J.F.; Barison, A.; Zalewski, J.; De Luca, L.; Degrauwe, S.; Claus, P.; et al. Long-Term Incremental Prognostic Value of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance After ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2018, 11, 813–825. [CrossRef]

- Atkins, T.; Freidoonimehr, N.; Beltrame, J.; Zeitz, C.; Arjomandi, M. The Impact of the Microvascular Resistance on the Measures of Stenosis Severity. Journal of Biomechanics 2024, 176, 112353. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Sun, L.; Yang, F.; Zhao, X.; Cai, R.; Yuan, W. Evaluation of Myocardial Viability in Myocardial Infarction Patients by Magnetic Resonance Perfusion and Delayed Enhancement Imaging. Herz 2019, 44, 735–742. [CrossRef]

- Demirkiran, A.; Robbers, L.F.H.J.; Van Der Hoeven, N.W.; Everaars, H.; Hopman, L.H.G.A.; Janssens, G.N.; Berkhof, H.J.; Lemkes, J.S.; Van De Bovenkamp, A.A.; Van Leeuwen, M.A.H.; et al. The Dynamic Relationship Between Invasive Microvascular Function and Microvascular Injury Indicators, and Their Association With Left Ventricular Function and Infarct Size at 1-Month After Reperfused ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circ: Cardiovascular Interventions 2022, 15, 892–902. [CrossRef]

- Westman, P.C.; Lipinski, M.J.; Luger, D.; Waksman, R.; Bonow, R.O.; Wu, E.; Epstein, S.E. Inflammation as a Driver of Adverse Left Ventricular Remodeling After Acute Myocardial Infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2016, 67, 2050–2060. [CrossRef]

- Dorbala, S.; Di Carli, M.F. Cardiac PET Perfusion: Prognosis, Risk Stratification, and Clinical Management. Seminars in Nuclear Medicine 2014, 44, 344–357. [CrossRef]

- Rischpler, C.; Dirschinger, R.J.; Nekolla, S.G.; Kossmann, H.; Nicolosi, S.; Hanus, F.; Van Marwick, S.; Kunze, K.P.; Meinicke, A.; Götze, K.; et al. Prospective Evaluation of18 F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Uptake in Postischemic Myocardium by Simultaneous Positron Emission Tomography/Magnetic Resonance Imaging as a Prognostic Marker of Functional Outcome. Circ: Cardiovascular Imaging 2016, 9. [CrossRef]

- Vera Cruz, P.; Palmes, P.; Bacalangco, N. Prognostic Value of Myocardial Blush Grade in ST-Elevation MI: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Interv Cardiol 2022, 17, e10. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y. Mechanism of Coronary Microcirculation Obstruction after Acute Myocardial Infarction and Cardioprotective Strategies. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 25, 367. [CrossRef]

- M.G. Kaya; F. Arslan; A. Abaci; G. van der Heijden; T. Timurkaynak; A. Cengel Myocardial Blush Grade: A Predictor for Major Adverse Cardiac Events after Primary PTCA with Stent Implantation for Acute Myocardial Infarction. Acta Cardiologica 2007, 445–451. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, X.; Feng, W.; Zhou, H.; Peng, W.; Wang, X. Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of Angiography-Derived Index of Microvascular Resistance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1360648. [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, H.; Zheng, D.; Xia, L. Index of Microcirculatory Resistance: State-of-the-Art and Potential Applications in Computational Simulation of Coronary Artery Disease. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2022, 23, 123–140. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi Hamidabad, N.; Kanaji, Y.; Ozcan, I.; Sara, J.D.S.; Ahmad, A.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. Prognostic Implications of Resistive Reserve Ratio in Patients With Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease With Myocardial Bridging. JAHA 2024, 13, e035000. [CrossRef]

- Eerdekens, R.; El Farissi, M.; De Maria, G.L.; Van Royen, N.; Van ‘T Veer, M.; Van Leeuwen, M.A.H.; Hoole, S.P.; Marin, F.; Carrick, D.; Tonino, P.A.L.; et al. Prognostic Value of Microvascular Resistance Reserve After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients With Myocardial Infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2024, 83, 2066–2076. [CrossRef]

- Milasinovic, D.; Nedeljkovic, O.; Maksimovic, R.; Sobic-Saranovic, D.; Dukic, D.; Zobenica, V.; Jelic, D.; Zivkovic, M.; Dedovic, V.; Stankovic, S.; et al. Coronary Microcirculation: The Next Frontier in the Management of STEMI. JCM 2023, 12, 1602. [CrossRef]

- Nolte, F.; Hoef, T.P. van de; Meuwissen, M.; Voskuil, M.; Chamuleau, S.; Henriques, J.P.S.; Verberne, H.J.; Eck-Smit, B.L.F. van; Koch, K.; Winter, R. de; et al. Increased Hyperaemic Coronary Microvascular Resistance Adds to the Presence of Myocardial Ischaemia Available online: https://eurointervention.pcronline.com/article/increased-hyperaemic-coronary-microvascular-resistance-adds-to-the-presence-of-myocardial-ischaemia (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Pu, J.; Niu, T.; Fang, J.; Chen, D.; Yidilisi, A.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, J.; Hu, Y.; Koo, B.-K.; et al. Prognostic Value of Coronary Angiography–Derived Index of Microcirculatory Resistance in Non–ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2024, 17, 1874–1886. [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, R.; Salzillo, C.; Caffè, A.; Montone, R.A. Invasive Functional Coronary Assessment in Myocardial Ischemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries: From Pathophysiological Mechanisms to Clinical Implications. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 23, 371. [CrossRef]

- Gdowski, M.A.; Murthy, V.L.; Doering, M.; Monroy-Gonzalez, A.G.; Slart, R.; Brown, D.L. Association of Isolated Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction With Mortality and Major Adverse Cardiac Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Aggregate Data. JAHA 2020, 9, e014954. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.M.; Prescott, E.I.B.; Abdulla, J. The Prognostic Value of Coronary Flow Reserve in Patients with Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease and Microvascular Dysfunction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Focus on Imaging Modality and Sex Difference. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2023, 39, 2545–2556. [CrossRef]

- Montisci, R.; Marchetti, M.F.; Ruscazio, M.; Biddau, M.; Secchi, S.; Zedda, N.; Casula, R.; Tuveri, F.; Kerkhof, P.L.; Meloni, L.; et al. Non-Invasive Coronary Flow Velocity Reserve Assessment Predicts Adverse Outcome in Women with Unstable Angina without Obstructive Coronary Artery Stenosis. Journal of Public Health Research 2023, 12, 22799036231181716. [CrossRef]

- Sadauskiene, E.; Zakarkaite, D.; Ryliskyte, L.; Celutkiene, J.; Rudys, A.; Aidietiene, S.; Laucevicius, A. Non-Invasive Evaluation of Myocardial Reperfusion by Transthoracic Doppler Echocardiography and Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography in Patients with Anterior Acute Myocardial Infarction. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2011, 9, 16. [CrossRef]

- Schröder, R. Prognostic Impact of Early ST-Segment Resolution in Acute ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2004, 110. [CrossRef]

- Nijveldt, R.; Van Der Vleuten, P.A.; Hirsch, A.; Beek, A.M.; Tio, R.A.; Tijssen, J.G.P.; Piek, J.J.; Van Rossum, A.C.; Zijlstra, F. Early Electrocardiographic Findings and MR Imaging-Verified Microvascular Injury and Myocardial Infarct Size. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2009, 2, 1187–1194. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).