Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Search Strategy

2.2. Literature Selection and Eligibiltiy Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Analysis

- Categorization: The selected studies were categorized into three main dental specialties: prosthodontics, orthodontics, and endodontics. This classification allowed for a structured analysis of 3D printing applications in each field.

- Thematic Analysis: Within each specialty, key themes were identified, including: Clinical applications of 3D printing, Advantages and limitations of 3D printing techniques, Comparison with traditional methods, Material properties and their impact on outcomes

- Comparative Assessment: Where available, comparative data between 3D printing and other manufacturing methods (e.g., milling, traditional casting) were analyzed. This included: Accuracy and precision of fabricated products, Mechanical properties of materials used, Time efficiency in production, Cost-effectiveness

- Technological Evaluation: The analysis included an assessment of different 3D printing technologies used in dentistry, such as Stereolithography (SLA) and Digital Light Processing (DLP), focusing on their specific advantages and limitations in dental applications.

- Clinical Relevance: The clinical significance of findings from various studies was evaluated, particularly in terms of the applicability and effectiveness of 3D-printed dental products in real-world clinical settings.

- Quality Assessment: The quality of evidence presented in each study was assessed, considering factors such as study design, sample size, and methodological rigor

- Synthesis of Findings: The analyzed data were synthesized to form comprehensive conclusions about the current state and future potential of 3D printing in dentistry, highlighting both its promising aspects and areas needing further research and development.

3. Results and Discussion

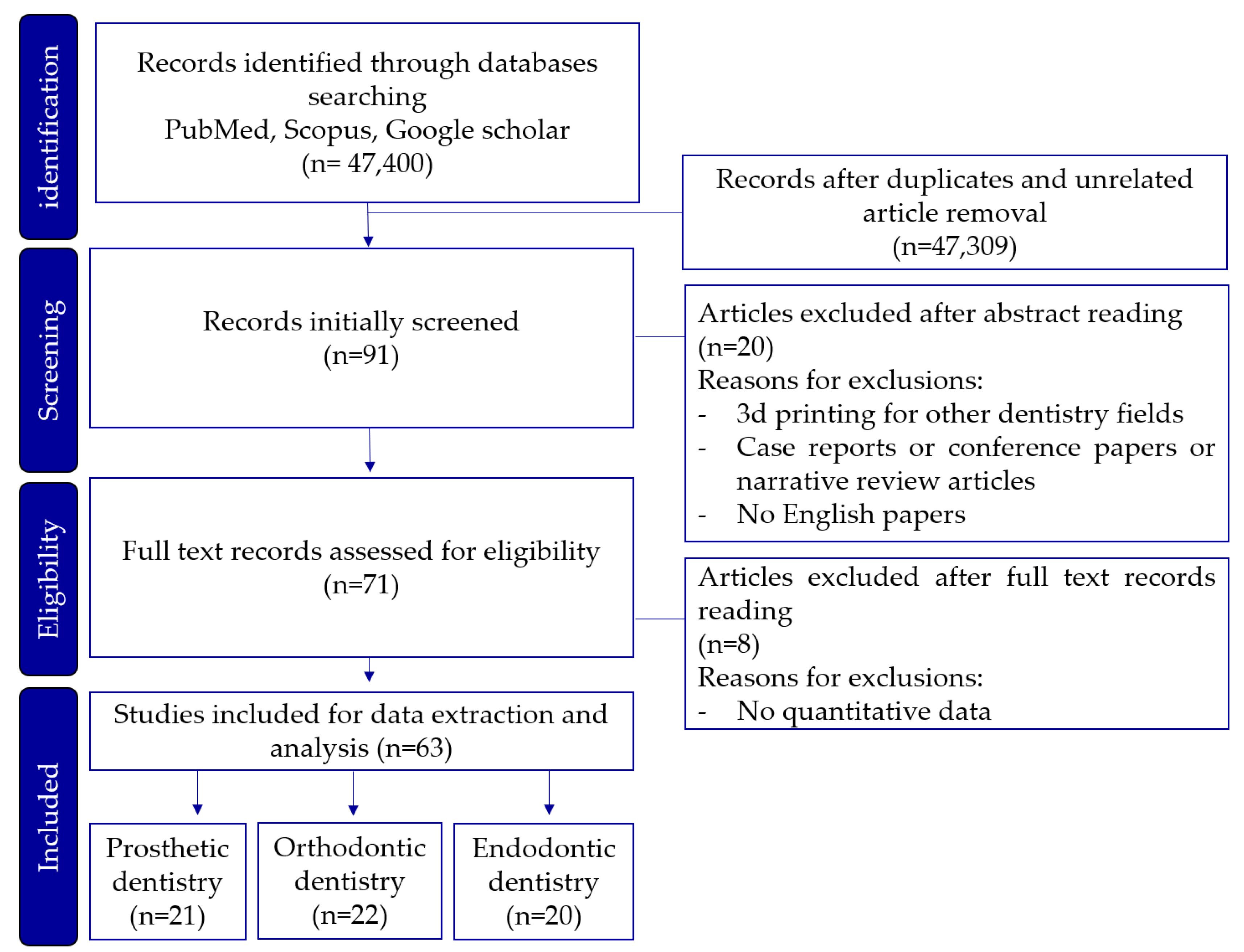

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. 3D Printing Techniques in Prosthetic Dentistry

3.3. 3D Printing in Orthodontic Dentistry

| Dentistry field | 3d printer type | Objective | Evaluation criteria |

Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthodontics | SLA | Fabrication of clear aligners | Aesthetics, patient comfort |

High precision for clear aligners, Biocompatible materials |

Post-processing required |

| DLP | Fabrication of diagnostic models | Reproducibility, accuracy |

Faster production of aligners,Minimal deformation | Limited size for larger appliances |

3.3. Endodontic Application of 3D Printing in Dentistry

| Dentistry field | 3d printer type | Objective | Evaluation criteria |

Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endodontics | SLA | Fabrication of surgical guides and anatomical models | Accuracy surgical planning support, training effectiveness |

High accuracy for surgical guides | Longer production time |

| DLP | Fabrication of endodontic training for root canals models |

Similarity to actual clinical environment |

Faster production of root canal models | Limited build volume for larger models |

|

| PolyJet | Fabrication of complex surgical guides | Accuracy, safety | Multi-material printing capability,High precision for complex anatomical models |

Higher material costs,Post-processing required |

| Application | Author (Year) | Study design |

Printer technology |

Objective of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fabrication of protheses | Huang, Zhuoli et al. (2015) [34] | In vitro | SLM | To compare the marginal and internal fit of single crowns fabrication |

| Chang, Hao-Sheng et al. (2019) [30] | In vitro | No information |

To evaluate the marginal gaps of dental restorations | |

| Khaledi, Amir-Alireza et al. (2020) [37] | In vitro | SLA and Polyjet | To evaluate the marginal fit of metal copings fabrication | |

| Addugala, Hemavardhini et al. (2022) [38] | In vitro | DLP | To compare the marginal discrepancy and internal adaptation of copings fabrication | |

| Ali Majeed, Zainab et el. (2023) [39] | In vitro | SLM | To evaluate the trueness and fitness of Co-Cr crown copings fabrication | |

| Kim, Dong-Yeon et al. (2018) [41] | In vitro | SLM | To evaluate the marginal and internal gaps of Co-Cr alloy copings fabrication | |

| Qian, B et al. (2015) [42] | In vitro | SLM | To investigate the microstructure of SLM specimens and its effect on mechanical properties | |

| Goguta, Luciana et al. (2021) [40] | In vitro | SLM | To ascertain the retention forces for telescopic crowns fabricated with SLM and SLS | |

| Complete denture | Herpel, Christopher et al. (2021) [20] | In vitro | SLA and DLP |

To compare the accuracy of 3D-printed and milled complete dentures. |

| Kalberer, Nicole et al. (2019) [45] | In vivo | Prototype machine | To compare the differences in trueness of complete dentures. | |

| Gad, Marwa A et al. (2024) [46] | In vitro | SLA | To assess and contrast the color stability and dimensional accuracy of denture base resins before and after aging | |

| Helal, Mohamed Ahmed et al. (2023) [47] | In vitro | DLP | To compare the dimensional changes of complete denture | |

| Prpić, Vladimir et al. (2020) [49] | In vitro | DLP | To evaluate the mechanical properties of denture base materials | |

| Freitas, Rodrigo Falcão Carvalho Porto de et al. (2023) [50] | In vitro | DLP | To investigate the surface roughness and contact angle, anti-biofilm formation, and mechanical properties of denture base resins | |

| Zeidan, Ahmed Abd El-Latif et al. (2023) [51] | In vitro | DLP | To compare the flexural strength of the denture base resin | |

| Dental cast model | Jeong, Yoo-Geum et al. (2018) [48] | In vitro | SLA | To evaluate the accuracy of models for dental prosthesis production |

| Park, Mid-Eum et al. (2018) [52] | In vitro | Polyjet | to compare the accuracy and reproducibility of dental casts production | |

| Grassia, Vincenzo et al. (2023) [60] | In vitro | SLA and DLP | To assess the trueness and precision of orthodontic models | |

| Ellakany, Passent et al. (2022) [68] | In vitro | SLA | To compare the accuracy of dental casts | |

| Rungrojwittayakul, Oraphan et al. (2020) [69] | In vitro | CLIP and DLP | To evaluate the accuracy of 3D printed models production | |

| Brown, Gregory B et al. (2018) [71] | In vitro | DLP and Polyjet | To assess the accuracy of 2 types of 3D printing techniques. | |

| Indirect bonding tray | Bachour, Petra C et al. (2022) [53] | In vivo | DLP | To evaluate the transfer accuracy of indirect bonding trays |

| Duarte, Maria Eduarda Assad et al. (2020) [72] | In vitro | Polyjet | To evaluate the reproducibility of digital tray transfer fit on digital indirect bonding | |

| Clear dental aligners |

Jindal, Prashant et al. (2019) [55] | In vitro | SLA | To compare compressive mechanical properties and geometric inaccuracies of dental aligners |

| Venezia, Pietro et al. (2022) [59] | In vitro | SLA and DLP | To evaluate the accuracy of the production of clear aligners | |

| Willi, Andreas et al. (2023) [61] | In vitro | DLP | To quantitatively assess the degree of conversion and water-leaching compounds | |

| Šimunović, Luka et al. (2024) [65] | In vitro | SLA | To evaluate the aligners’ response to common staining agents in color and chemical stability. | |

| Pasaoglu Bozkurt, Aylin et al. (2025) [66] | In vitrp | SLA | to compare and evaluate time-dependent biofilm formation and microbial adhesion of clear aligner | |

| Surgical and non-surgical guide | Sarkarat, Farzin et al. (2023) [54] | In vivo | Polyjet | To investigate the accuracy of surgical splints for practical use |

| van der Meer, Wicher J et al. (2016) [73] | In vivo | Polyjet | To describe the application of 3D digital mapping technology for navigation of obliterated canal systems | |

| Ackerman, Shira et al. (2019) [74] | In vivo | SLA | To evaluate the accuracy of CBCT-designed surgical guides | |

| Connert, T et al. (2018) [75] | In vivo | Polyjet | To present a novel treatment for root canal localization | |

| Lara-Mendes, Sônia T de O et al. (2018) [76] | In vivo | Polyjet | to describe a guided technique for accessing root canals | |

| Connert, Thomas et al. (2019) [77] | In vitro | Polyjet | To compare endodontic access cavities in teeth with calcified root canals | |

| Loureiro, Marco Antônio Z et al. (2021) [78] | In vivo | DLP | To discuss the impact of new technologies on treating a complex case | |

| Lee, Seung-Jong et al. (2006) [79] | In vivo | Prototype machine | To demonstrate the anatomy of 3 distal roots of a right mandibular first molar | |

| Byun, Chanhee et al. (2015) [80] | In vivo | Polyjet | To present a case of successful root canal treatment | |

| Connert, Thomas et al. (2017) [81] | In vitro | Polyjet | To assess the accuracy of guided endodontics in mandibular anterior teeth | |

| Pinsky, Harold M et al. (2007) [82] | In vitro | No information | To introduce periapical surgical guidance computer-aided manufacturing surgical guides | |

| Buchgreitz, J et al. (2016) [84] | Ex vivo | No information | To evaluate the accuracy of a preparation for teeth with pulp canal obliteration | |

| Kfir, A et al. (2013) [85] | In vivo | Polyjet | To report on the use of a 3D plastic model for the diagnosis and treatment of densinvaginatus | |

| Hawkins, T K et al. (2020) [92] | In vitro | Polyjet | To compare surgical time, bevel angle and site volumetric profiles of osteotomy and resection area of endodontic microsurgery | |

| Clinical Training | Marending, M et al. (2016) [87] | In vitro | No information | To assess contemporary rotary instrumenting systems in a pre-clinical student course setting. |

| Tonini, Riccardo, et al. (2021) [89] | In vivo | No information | To evaluate the applicability of a novel print and try technique in the presence of aberrant endodontic anatomies | |

| Kamburoğlu, Kıvanç, et al. (2023) [90] | In vitro | SLA | To evaluate the accuracy of guides prepared using CBCT images on 3D-printed teeth for root canal treatment | |

| Llaquet Pujol, Marc et al. (2021) [91] | In vivo | SLA | To describe the endodontic management of pulp canal obliteration by guided endodontics using both a virtually designed 3D guide | |

| Kröger, E et al. (2017) [93] | In vitro | Polyjet | To introduce workflow to create 3D printed simulation models based on real patient situations for hands-on practice. | |

| Pouhaër, Matéo et al. (2022) [94] | In vitro | SLA | To show the design phases of different dental models of a lower first molar, showing root canal anatomy and the ideal access cavity. | |

| Autotrans-plantation | Kamio, Takashi et al. (2019) [95] | In vivo | Fused filament fabrication |

To describe 3D morphological evaluation, preoperative treatment planning, and surgical simulation |

| Lee, Seung-Jong, et al. (2001) [96] | In vivo | Prototype machine | To minimize extra-oral time and achieve optimal contact in autotransplantation | |

| Lee, Seung-Jong, et al. (2012) [97] | In vivo | Prototype machine | To reduce extra-oral time and secure optimal contact in autogenous tooth transplantation | |

| Honda, M et al. [99] | In vivo | SLA | To simplify the surgical technique in autotransplantation | |

| Keightley, Alexander J et al. (2010) [100] | In vivo | Binder jetting (powder-based type) |

To develop and apply a surgical template for autotransplantation | |

| Park, Young-Seok et al. (2012) [101] | In vivo | Prototype machine | To develop autotransplantation with simultaneous sinus floor elevation and implant installation | |

| Strbac, Georg D et al. (2016) [102] | In vivo | Polyjet | To introduce a method for autotransplantation of teeth |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haidar, Z.S. Digital dentistry: past, present, and future. Digital Medicine and Healthcare Technology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anadioti, E.; Musharbash, L.; Blatz, M.B.; Papavasiliou, G.; Kamposiora, P. 3D printed complete removable dental prostheses: a narrative review. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harikrishnan, S.; Subramanian, A.K. 3D printing in orthodontics: A narrative review. Journal of International Oral Health 2023, 15, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, P.; Chong, B. 3D imaging, 3D printing and 3D virtual planning in endodontics. Clinical oral investigations 2018, 22, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strbac, G.D.; Schnappauf, A.; Giannis, K.; Moritz, A.; Ulm, C. Guided Modern Endodontic Surgery: A Novel Approach for Guided Osteotomy and Root Resection. J Endod 2017, 43, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoukala, E.; Lyros, I.; Tsolakis, A.I.; Maroulakos, M.P.; Tsolakis, I.A. Direct 3D-Printed Orthodontic Retainers. A Systematic Review. Children (Basel) 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyami, M.H. The Applications of 3D-Printing Technology in Prosthodontics: A Review of the Current Literature. Cureus 2024, 16, e68501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansbury, J.W.; Idacavage, M.J. 3D printing with polymers: Challenges among expanding options and opportunities. Dental materials 2016, 32, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahayeri, A.; Morgan, M.; Fugolin, A.P.; Bompolaki, D.; Athirasala, A.; Pfeifer, C.S.; Ferracane, J.L.; Bertassoni, L.E. 3D printed versus conventionally cured provisional crown and bridge dental materials. Dental materials 2018, 34, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-M.; Park, J.-M.; Kim, S.-K.; Heo, S.-J.; Koak, J.-Y. Flexural strength of 3D-printing resin materials for provisional fixed dental prostheses. Materials 2020, 13, 3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, J.; Cheng, M.; Wagels, M. Utility and cost–effectiveness of 3D-printed materials for clinical use. Journal of 3D printing in medicine 2019, 3, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Fang, Y.; Liao, Y.; Chen, G.; Gao, C.; Zhu, P. 3D printing and digital processing techniques in dentistry: a review of literature. Advanced Engineering Materials 2019, 21, 1801013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, G.K.; Gharib, H.; Liao, P.; Liu, H. Guided access cavity preparation using cost-effective 3D printers. Journal of endodontics 2022, 48, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, A.; Hickel, R.; Reymus, M. 3D printing in dentistry—State of the art. Operative dentistry 2020, 45, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansbury, J.W.; Idacavage, M.J. 3D printing with polymers: Challenges among expanding options and opportunities. Dent Mater 2016, 32, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, K.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, K.-B. Comparison of intaglio surface trueness of interim dental crowns fabricated with SLA 3D printing, DLP 3D printing, and milling technologies. In Proceedings of the Healthcare; 2021; p. 983. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmassl, O.; Dumfahrt, H.; Grunert, I.; Steinmassl, P.A. Influence of CAD/CAM fabrication on denture surface properties. Journal of oral rehabilitation 2018, 45, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Kratchman, S. Modern endodontic surgery concepts and practice: a review. J Endod 2006, 32, 601–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.-G.; Lee, W.-S.; Lee, K.-B. Accuracy evaluation of dental models manufactured by CAD/CAM milling method and 3D printing method. The journal of advanced prosthodontics 2018, 10, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herpel, C.; Tasaka, A.; Higuchi, S.; Finke, D.; Kühle, R.; Odaka, K.; Rues, S.; Lux, C.J.; Yamashita, S.; Rammelsberg, P. Accuracy of 3D printing compared with milling—A multi-center analysis of try-in dentures. Journal of Dentistry 2021, 110, 103681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, S.; Mukai, E.; Santos-Junior, J.A.; Shibli, J.A.; Faveri, M.; Giro, G. Assessment of the reproducibility and precision of milling and 3D printing surgical guides. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, C.; Federici, M.I.; Masciotti, F.; Marinucci, L.; Xhimitiku, I.; Cianetti, S.; Pagano, S. Mechanical properties of 3D printed prosthetic materials compared with milled and conventional processing: A systematic review and meta-analysis of in vitro studies. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 2024, 132, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousef, H.; Harris, B.T.; Elathamna, E.N.; Morton, D.; Lin, W.-S. Effect of additive manufacturing process and storage condition on the dimensional accuracy and stability of 3D-printed dental casts. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 2022, 128, 1041–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-M.; Jeon, J.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, H.-Y.; Kim, W.-C. Three-dimensional evaluation of the reproducibility of presintered zirconia single copings fabricated with the subtractive method. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry 2016, 116, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Chen, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Hou, X.; Li, K.; Lu, X.; Shi, H.; Lee, E.-S.; Jiang, H.B. A review of 3D printing in dentistry: Technologies, affecting factors, and applications. Scanning 2021, 2021, 9950131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawood, A.; Marti, B.M.; Sauret-Jackson, V.; Darwood, A. 3D printing in dentistry. British dental journal 2015, 219, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barazanchi, A.; Li, K.C.; Al-Amleh, B.; Lyons, K.; Waddell, J.N. Additive technology: update on current materials and applications in dentistry. Journal of Prosthodontics 2017, 26, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolakis, I.A.; Papaioannou, W.; Papadopoulou, E.; Dalampira, M.; Tsolakis, A.I. Comparison in terms of accuracy between DLP and LCD printing technology for dental model printing. Dentistry journal 2022, 10, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, H.; Zhang, T.; Xu, H.; Luo, S.; Nie, J.; Zhu, X. Photo-curing 3D printing technique and its challenges. Bioactive materials 2020, 5, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.S.; Peng, Y.T.; Hung, W.L.; Hsu, M.L. Evaluation of marginal adaptation of Co-Cr-Mo metal crowns fabricated by traditional method and computer-aided technologies. J Dent Sci 2019, 14, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövgren, N.; Roxner, R.; Klemendz, S.; Larsson, C. Effect of production method on surface roughness, marginal and internal fit, and retention of cobalt-chromium single crowns. J Prosthet Dent 2017, 118, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V, H.; Ali, S.A.M.; N, J.; Ifthikar, M.; Senthil, S.; Basak, D.; Huda, F.; Priyanka. Evaluation of internal and marginal fit of two metal ceramic system - in vitro study. J Clin Diagn Res 2014, 8, Zc53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundar, M.K.; Chikmagalur, S.B.; Pasha, F. Marginal fit and microleakage of cast and metal laser sintered copings--an in vitro study. J Prosthodont Res 2014, 58, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X. Clinical Marginal and Internal Fit of Crowns Fabricated Using Different CAD/CAM Technologies. J Prosthodont 2015, 24, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, S.M.; Yesil Duymus, Z. Influence of Tooth Preparation Design on Fitting Accuracy of CAD-CAM Based Restorations. J Esthet Restor Dent 2016, 28, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, B.E.; Rønold, H.J.; Dahl, J.E. Internal fit of single crowns produced by CAD-CAM and lost-wax metal casting technique assessed by the triple-scan protocol. J Prosthet Dent 2017, 117, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaledi, A.A.; Farzin, M.; Akhlaghian, M.; Pardis, S.; Mir, N. Evaluation of the marginal fit of metal copings fabricated by using 3 different CAD-CAM techniques: Milling, stereolithography, and 3D wax printer. J Prosthet Dent 2020, 124, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addugala, H.; Venugopal, V.N.; Rengasamy, S.; Yadalam, P.K.; Albar, N.H.; Alamoudi, A.; Bahammam, S.A.; Zidane, B.; Bahammam, H.A.; Bhandi, S.; et al. Marginal and Internal Gap of Metal Copings Fabricated Using Three Types of Resin Patterns with Subtractive and Additive Technology: An In Vitro Comparison. Materials (Basel) 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Majeed, Z.; Hasan Jasim, H. Digital Evaluation of Trueness and Fitting Accuracy of Co-Cr Crown Copings Fabricated by Different Manufacturing Technologies. Cureus 2023, 15, e39819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goguta, L.; Lungeanu, D.; Negru, R.; Birdeanu, M.; Jivanescu, A.; Sinescu, C. Selective Laser Sintering versus Selective Laser Melting and Computer Aided Design - Computer Aided Manufacturing in Double Crowns Retention. J Prosthodont Res 2021, 65, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, W.C. Comparison and evaluation of marginal and internal gaps in cobalt-chromium alloy copings fabricated using subtractive and additive manufacturing. J Prosthodont Res 2018, 62, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, B.; Saeidi, K.; Kvetková, L.; Lofaj, F.; Xiao, C.; Shen, Z. Defects-tolerant Co-Cr-Mo dental alloys prepared by selective laser melting. Dent Mater 2015, 31, 1435–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.S.; Gurumurthy, V.; Quadri, S.A.; Bavabeedu, S.S.; Abdelaziz, K.M.; Okshah, A.; Alshadidi, A.A.F.; Yessayan, L.; Mosaddad, S.A.; Heboyan, A. The flexural strength of 3D-printed provisional restorations fabricated with different resins: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herpel, C.; Tasaka, A.; Higuchi, S.; Finke, D.; Kühle, R.; Odaka, K.; Rues, S.; Lux, C.J.; Yamashita, S.; Rammelsberg, P.; et al. Accuracy of 3D printing compared with milling - A multi-center analysis of try-in dentures. J Dent 2021, 110, 103681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalberer, N.; Mehl, A.; Schimmel, M.; Müller, F.; Srinivasan, M. CAD-CAM milled versus rapidly prototyped (3D-printed) complete dentures: An in vitro evaluation of trueness. J Prosthet Dent 2019, 121, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gad, M.A.; Abdelhamid, A.M.; ElSamahy, M.; Abolgheit, S.; Hanno, K.I. Effect of aging on dimensional accuracy and color stability of CAD-CAM milled and 3D-printed denture base resins: a comparative in-vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, M.A.; Abdelrahim, R.A.; Zeidan, A.A.E. Comparison of Dimensional Changes Between CAD-CAM Milled Complete Denture Bases and 3D Printed Complete Denture Bases: An In Vitro Study. J Prosthodont 2023, 32, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.G.; Lee, W.S.; Lee, K.B. Accuracy evaluation of dental models manufactured by CAD/CAM milling method and 3D printing method. J Adv Prosthodont 2018, 10, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prpić, V.; Schauperl, Z.; Ćatić, A.; Dulčić, N.; Čimić, S. Comparison of Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed, CAD/CAM, and Conventional Denture Base Materials. J Prosthodont 2020, 29, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, R.; Duarte, S.; Feitosa, S.; Dutra, V.; Lin, W.S.; Panariello, B.H.D.; Carreiro, A. Physical, Mechanical, and Anti-Biofilm Formation Properties of CAD-CAM Milled or 3D Printed Denture Base Resins: In Vitro Analysis. J Prosthodont 2023, 32, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, A.A.E.; Sherif, A.F.; Baraka, Y.; Abualsaud, R.; Abdelrahim, R.A.; Gad, M.M.; Helal, M.A. Evaluation of the Effect of Different Construction Techniques of CAD-CAM Milled, 3D-Printed, and Polyamide Denture Base Resins on Flexural Strength: An In Vitro Comparative Study. J Prosthodont 2023, 32, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.E.; Shin, S.Y. Three-dimensional comparative study on the accuracy and reproducibility of dental casts fabricated by 3D printers. J Prosthet Dent 2018, 119, e861–e861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachour, P.C.; Klabunde, R.; Grünheid, T. Transfer accuracy of 3D-printed trays for indirect bonding of orthodontic brackets: a clinical study. The Angle Orthodontist 2022, 92, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkarat, F.; Tofighi, O.; Jamilian, A.; Fateh, A.; Abbaszadeh, F. Are Virtually Designed 3D Printed Surgical Splints Accurate Enough for Maxillary Reposition as an Intermediate Orthognathic Surgical Guide. Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery 2023, 22, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, P.; Juneja, M.; Siena, F.L.; Bajaj, D.; Breedon, P. Mechanical and geometric properties of thermoformed and 3D printed clear dental aligners. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2019, 156, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, G.M.; Mapelli, A.; Maspero, C.; Santaniello, T.; Serafin, M.; Farronato, M.; Caprioglio, A. Direct 3D printing of clear orthodontic aligners: current state and future possibilities. Materials 2021, 14, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, M.; Arqub, S.A. Biomechanics of clear aligners: hidden truths & first principles. J World Fed Orthod 2022, 11, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maspero, C.; Tartaglia, G.M. 3D Printing of Clear Orthodontic Aligners: Where We Are and Where We Are Going. Materials (Basel) 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venezia, P.; Ronsivalle, V.; Rustico, L.; Barbato, E.; Leonardi, R.; Lo Giudice, A. Accuracy of orthodontic models prototyped for clear aligners therapy: A 3D imaging analysis comparing different market segments 3D printing protocols. J Dent 2022, 124, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassia, V.; Ronsivalle, V.; Isola, G.; Nucci, L.; Leonardi, R.; Lo Giudice, A. Accuracy (trueness and precision) of 3D printed orthodontic models finalized to clear aligners production, testing crowded and spaced dentition. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willi, A.; Patcas, R.; Zervou, S.-K.; Panayi, N.; Schätzle, M.; Eliades, G.; Hiskia, A.; Eliades, T. Leaching from a 3D-printed aligner resin. European Journal of Orthodontics 2023, 45, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamer, İ.; Öztaş, E.; Marşan, G. Orthodontic Treatment with Clear Aligners and The Scientific Reality Behind Their Marketing: A Literature Review. Turk J Orthod 2019, 32, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narongdej, P.; Hassanpour, M.; Alterman, N.; Rawlins-Buchanan, F.; Barjasteh, E. Advancements in Clear Aligner Fabrication: A Comprehensive Review of Direct-3D Printing Technologies. Polymers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, G.M.; Mapelli, A.; Maspero, C.; Santaniello, T.; Serafin, M.; Farronato, M.; Caprioglio, A. Direct 3D Printing of Clear Orthodontic Aligners: Current State and Future Possibilities. Materials (Basel) 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šimunović, L.; Čekalović Agović, S.; Marić, A.J.; Bačić, I.; Klarić, E.; Uribe, F.; Meštrović, S. Color and Chemical Stability of 3D-Printed and Thermoformed Polyurethane-Based Aligners. Polymers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasaoglu Bozkurt, A.; Demirci, M.; Erdogan, P.; Kayalar, E. Comparison of microbial adhesion and biofilm formation on different orthodontic aligners. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2025, 167, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoukala, E.; Lyros, I.; Tsolakis, A.I.; Maroulakos, M.P.; Tsolakis, I.A. Direct 3d-printed orthodontic retainers. a systematic review. Children 2023, 10, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellakany, P.; Al-Harbi, F.; El Tantawi, M.; Mohsen, C. Evaluation of the accuracy of digital and 3D-printed casts compared with conventional stone casts. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 2022, 127, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rungrojwittayakul, O.; Kan, J.Y.; Shiozaki, K.; Swamidass, R.S.; Goodacre, B.J.; Goodacre, C.J.; Lozada, J.L. Accuracy of 3D Printed Models Created by Two Technologies of Printers with Different Designs of Model Base. J Prosthodont 2020, 29, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, A.; Marti Marti, B.; Sauret-Jackson, V.; Darwood, A. 3D printing in dentistry. Br Dent J 2015, 219, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.B.; Currier, G.F.; Kadioglu, O.; Kierl, J.P. Accuracy of 3-dimensional printed dental models reconstructed from digital intraoral impressions. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2018, 154, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.E.A.; Gribel, B.F.; Spitz, A.; Artese, F.; Miguel, J.A.M. Reproducibility of digital indirect bonding technique using three-dimensional (3D) models and 3D-printed transfer trays. Angle Orthod 2020, 90, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, W.J.; Vissink, A.; Ng, Y.L.; Gulabivala, K. 3D Computer aided treatment planning in endodontics. J Dent 2016, 45, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackerman, S.; Aguilera, F.C.; Buie, J.M.; Glickman, G.N.; Umorin, M.; Wang, Q.; Jalali, P. Accuracy of 3-dimensional-printed Endodontic Surgical Guide: A Human Cadaver Study. J Endod 2019, 45, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connert, T.; Zehnder, M.S.; Amato, M.; Weiger, R.; Kühl, S.; Krastl, G. Microguided Endodontics: a method to achieve minimally invasive access cavity preparation and root canal location in mandibular incisors using a novel computer-guided technique. Int Endod J 2018, 51, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Mendes, S.T.O.; Barbosa, C.F.M.; Santa-Rosa, C.C.; Machado, V.C. Guided Endodontic Access in Maxillary Molars Using Cone-beam Computed Tomography and Computer-aided Design/Computer-aided Manufacturing System: A Case Report. J Endod 2018, 44, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connert, T.; Krug, R.; Eggmann, F.; Emsermann, I.; ElAyouti, A.; Weiger, R.; Kühl, S.; Krastl, G. Guided Endodontics versus Conventional Access Cavity Preparation: A Comparative Study on Substance Loss Using 3-dimensional-printed Teeth. J Endod 2019, 45, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, M.A.Z.; Silva, J.A.; Chaves, G.S.; Capeletti, L.R.; Estrela, C.; Decurcio, D.A. Guided endodontics: The impact of new technologies on complex case solution. Aust Endod J 2021, 47, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Jang, K.H.; Spangberg, L.S.; Kim, E.; Jung, I.Y.; Lee, C.Y.; Kum, K.Y. Three-dimensional visualization of a mandibular first molar with three distal roots using computer-aided rapid prototyping. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2006, 101, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, C.; Kim, C.; Cho, S.; Baek, S.H.; Kim, G.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, S.Y. Endodontic Treatment of an Anomalous Anterior Tooth with the Aid of a 3-dimensional Printed Physical Tooth Model. J Endod 2015, 41, 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connert, T.; Zehnder, M.S.; Weiger, R.; Kühl, S.; Krastl, G. Microguided Endodontics: Accuracy of a Miniaturized Technique for Apically Extended Access Cavity Preparation in Anterior Teeth. J Endod 2017, 43, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsky, H.M.; Champleboux, G.; Sarment, D.P. Periapical surgery using CAD/CAM guidance: preclinical results. J Endod 2007, 33, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Rabié, C.; Torres, A.; Lambrechts, P.; Jacobs, R. Clinical applications, accuracy and limitations of guided endodontics: a systematic review. Int Endod J 2020, 53, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchgreitz, J.; Buchgreitz, M.; Mortensen, D.; Bjørndal, L. Guided access cavity preparation using cone-beam computed tomography and optical surface scans - an ex vivo study. Int Endod J 2016, 49, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kfir, A.; Telishevsky-Strauss, Y.; Leitner, A.; Metzger, Z. The diagnosis and conservative treatment of a complex type 3 dens invaginatus using cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) and 3D plastic models. Int Endod J 2013, 46, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Wealleans, J.; Ray, J. Endodontic applications of 3D printing. Int Endod J 2018, 51, 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marending, M.; Biel, P.; Attin, T.; Zehnder, M. Comparison of two contemporary rotary systems in a pre-clinical student course setting. Int Endod J 2016, 49, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, O.; Scott, R.; Arias, A.; Lim, E.; Paque, F.; Almassi, S.; Hejlawy, S. Evaluation of Dental Students' Skills Acquisition in Endodontics Using a 3D Printed Tooth Model. European endodontic journal 2021, 6, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonini, R.; Xhajanka, E.; Giovarruscio, M.; Foschi, F.; Boschi, G.; Atav-Ates, A.; Cicconetti, A.; Seracchiani, M.; Gambarini, G.; Testarelli, L. Print and try technique: 3D-printing of teeth with complex anatomy a novel endodontic approach. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamburoğlu, K.; Sönmez, G.; Koç, C.; Yılmaz, F.; Tunç, O.; Isayev, A. Access Cavity Preparation and Localization of Root Canals Using Guides in 3D-Printed Teeth with Calcified Root Canals: An In Vitro CBCT Study. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llaquet Pujol, M.; Vidal, C.; Mercadé, M.; Muñoz, M.; Ortolani-Seltenerich, S. Guided Endodontics for Managing Severely Calcified Canals. J Endod 2021, 47, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, T.K.; Wealleans, J.A.; Pratt, A.M.; Ray, J.J. Targeted endodontic microsurgery and endodontic microsurgery: a surgical simulation comparison. Int Endod J 2020, 53, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kröger, E.; Dekiff, M.; Dirksen, D. 3D printed simulation models based on real patient situations for hands-on practice. Eur J Dent Educ 2017, 21, e119–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouhaër, M.; Picart, G.; Baya, D.; Michelutti, P.; Dautel, A.; Pérard, M.; Le Clerc, J. Design of 3D-printed macro-models for undergraduates' preclinical practice of endodontic access cavities. Eur J Dent Educ 2022, 26, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamio, T.; Kato, H. Autotransplantation of Impacted Third Molar Using 3D Printing Technology: A Case Report. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll 2019, 60, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Jung, I.Y.; Lee, C.Y.; Choi, S.Y.; Kum, K.Y. Clinical application of computer-aided rapid prototyping for tooth transplantation. Dent Traumatol 2001, 17, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Kim, E. Minimizing the extra-oral time in autogeneous tooth transplantation: use of computer-aided rapid prototyping (CARP) as a duplicate model tooth. Restor Dent Endod 2012, 37, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, J.P.; Jongkees, F.A.; Anssari Moin, D.; Wismeijer, D.; van Merkesteyn, J.P.R. Autotransplantation of teeth using computer-aided rapid prototyping of a three-dimensional replica of the donor tooth: a systematic literature review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2017, 46, 1466–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, M.; Uehara, H.; Uehara, T.; Honda, K.; Kawashima, S.; Honda, K.; Yonehara, Y. Use of a replica graft tooth for evaluation before autotransplantation of a tooth. A CAD/CAM model produced using dental-cone-beam computed tomography. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010, 39, 1016–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keightley, A.J.; Cross, D.L.; McKerlie, R.A.; Brocklebank, L. Autotransplantation of an immature premolar, with the aid of cone beam CT and computer-aided prototyping: a case report. Dent Traumatol 2010, 26, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S.; Baek, S.H.; Lee, W.C.; Kum, K.Y.; Shon, W.J. Autotransplantation with simultaneous sinus floor elevation. J Endod 2012, 38, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strbac, G.D.; Schnappauf, A.; Giannis, K.; Bertl, M.H.; Moritz, A.; Ulm, C. Guided Autotransplantation of Teeth: A Novel Method Using Virtually Planned 3-dimensional Templates. J Endod 2016, 42, 1844–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dentistry field | 3d printer type | Objective | Evaluation criteria |

Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prosthodontics | SLA | Fabrication of prosthetics | Accuracy, resolution, post-processing needs |

High resolution,Suitable for detailed work |

Requires post- curing,Longer production time |

| DLP | Mass production of prosthetics | Production speed, build volume | Faster print times,Cost-effective for large-scale production | Limited build volume | |

| Milling | Final crown fabrication | Accuracy, durability |

Superior strength and durability,High precision |

Material waste,Difficulty in creating intricate internal structures |

|

| PolyJet | Fabrication of metal coping | Accuracy, resolution, safety |

Multi-material printing High precision for coping | Higher material costs, Low durabilityPost-processing required |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).