1. Introduction

When delving into modern and developed societies, one finds that strategically significant and intricately complete civil infrastructures and buildings constitute their core commonality. This commonality manifests broadly in their widespread application across transportation, industrial production, economic activities, and the protection of personnel and materials. Given the importance of these facilities, we cannot overlook their aging and degradation, nor can we afford the inestimable losses and harm that may result from failing to detect and take timely action. Furthermore, due to the large number and ubiquity of these structures, the majority of them are inevitably and frequently exposed to severe disaster events and continuous environmental vibrations, such as earthquakes, floods, tornadoes, and corrosion, as well as other uncertain factors like traffic loads, material aging, impacts, and environmental corrosion. Consequently, monitoring and assessing structural performance has become a fundamental requirement for enhancing structural integrity and safety.

Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) and structural damage detection methods have continuously evolved, with research gaining new life across various scientific fields such as aerospace, civil, and mechanical engineering. [

1]To achieve SHM, researchers employ a variety of different sensor devices to collect signal data, including acoustic, pressure, temperature, force, and accelerometer sensors. This has given rise to the processing of multivariate signals.

The core objective of signal processing is to collect, analyze, and process multivariate signals such as vibrations, noise, temperature, and pressure generated during the operation of mechanical systems, extracting key features that reflect the system’s state, thereby enabling early fault detection, precise diagnosis, and effective prevention. In recent years, SHM researchers have dedicated themselves to integrating and fusing various cutting-edge technologies, particularly those from different information technology and engineering methodologies, to develop economical, accurate, and reliable monitoring methods. Additionally, various data mining, visualization tools, and statistical computations frequently appear in monitoring and processing solutions. Beyond traditional vibration-based monitoring, detections related to sound, temperature, and motor current are now emerging, as mentioned by Wonho Jung[

2]. Moreover, changes in structural properties, such as stiffness, are significantly observable in variations of multivariate signals, and internal structural components can also be accurately represented through these signals. Therefore, it is crucial that signal processing techniques for monitoring changes in structural vibration responses are robust during the process of damage localization, quantification, and detection.

The diversity of signals requires the adoption of corresponding processing techniques based on their specific characteristics, and for a particular signal, a so-called powerful signal technique is one that is appropriately adapted. For example, linear signals satisfy the superposition principle and can thus be analyzed using linear processing techniques such as linear filters and Fourier transforms. Nonlinear signals, however, do not satisfy the superposition principle and require nonlinear processing techniques such as nonlinear filters and Hilbert-Huang transforms to reveal their complex characteristics. Directly applying a highly powerful linear signal processing model cannot guarantee perfect representation of nonlinear signals. Therefore, in the process of studying nonlinear signal processing models, new and specific technologies are often required.

In mechanical systems and structures, due to the complexity of operating conditions, external environmental interferences, and the gradual aging and damage of materials and components, the collected signals are often non-stationary and nonlinear. These non-stationary and nonlinear signals contain rich state information, such as vibrations, stresses, and strains, which can reflect the health status of mechanical systems and structures. Therefore, signal processing techniques in the field of structural health require the integration of time-domain, frequency-domain, and time-frequency-domain characteristics to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the nature of signals and improve the accuracy of diagnosis.

In recent years, researchers have made unremitting efforts to achieve precise processing of signals in the field of structural health monitoring (SHM), particularly for non-stationary and nonlinear signals. The emergence of non-parametric time-frequency analysis techniques, such as Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), Wavelet Transform (WT), and Wigner-Ville Distribution (WVD), has found widespread application in SHM. These techniques can simultaneously provide information about signals in both the time and frequency domains, aiding in a more comprehensive understanding of signal characteristics. However, these techniques have their limitations, such as the trade-off between time resolution and frequency resolution in STFT, the sensitivity of WT to the choice of basis functions, and the cross-term and noise sensitivity issues in WVD.

To address these issues, adaptive signal processing techniques have emerged. Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) and its optimized models (e.g., Ensemble EMD (EEMD), Multivariate EMD (MEEMD)) decompose signals into a series of Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) through an iterative process, with each IMF representing a natural oscillation mode in the signal. This method excels in processing nonlinear and non-stationary signals but also faces challenges in practical applications, such as endpoint effects and energy non-conservation.

Furthermore, Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) and its variants (e.g., Sparse VMD (SVMD), Adaptive VMD (AVMD)) achieve signal decomposition by minimizing a variational problem, offering higher flexibility and stability. The optimized model, Empirical Wavelet Transform, combines the adaptive decomposition concept of EMD with the compact support framework of wavelet transform theory. By decomposing the signal into multiple frequency bands and constructing wavelet functions compatible with a wavelet filter bank for each band, it achieves adaptive decomposition of the signal. This approach can capture local features of the signal and is particularly suitable for processing nonlinear and non-stationary signals.

The latest technology, deconvolution techniques such as Minimum Entropy Deconvolution (MED) and Maximum Correlated Kurtosis Deconvolution (MCKD), enhance signal fault features through filtering processing, improving diagnostic accuracy. These techniques can be regarded as a method of adaptive signal processing. In the deconvolution process, it is often necessary to estimate the Point Spread Function (PSF) or convolution kernel of the signal, a process that typically relies on adaptive algorithms like the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm or blind deconvolution algorithms. These algorithms can automatically adjust parameters based on observed data and prior knowledge to optimize the deconvolution effect. The combination of deconvolution with the aforementioned adaptive and non-parametric time-frequency analyses elevates signal processing techniques to a new level.

This paper aims to review key signal processing techniques in SHM, particularly non-parametric time-frequency analysis, adaptive decomposition, and deconvolution techniques. The first part introduces non-parametric time-frequency analysis. It begins by presenting the concept, applications, advantages, and disadvantages of STFT and discussing its widespread use in SHM. It then elaborates on the basic principles of WT, application examples, and its advantages and disadvantages compared to STFT. Furthermore, this paper delves into the application of WVD in time-frequency analysis, including its definition, specific application cases in SHM, and the advantages of high time resolution and instantaneous frequency analysis, while also pointing out the limitations of cross-terms and noise sensitivity. The second part introduces adaptive time-frequency analysis, detailing the principles, applications, and advantages and disadvantages of EMD and its optimized models (e.g., EEMD, MEEMD), emphasizing EMD’s unique advantages in processing nonlinear and non-stationary signals. Additionally, it explores the concepts, applications, and comparisons with traditional methods of VMD and its variants (e.g., SVMD, AVMD), highlighting VMD’s flexibility and stability in signal decomposition. The final part discusses deconvolution techniques, examining the applications of deconvolution techniques such as MED and MCKD in machinery fault diagnosis, and analyzing their advantages and disadvantages. This paper aims to provide researchers in the SHM field with a comprehensive understanding of signal processing techniques and serve as a reference for future research.

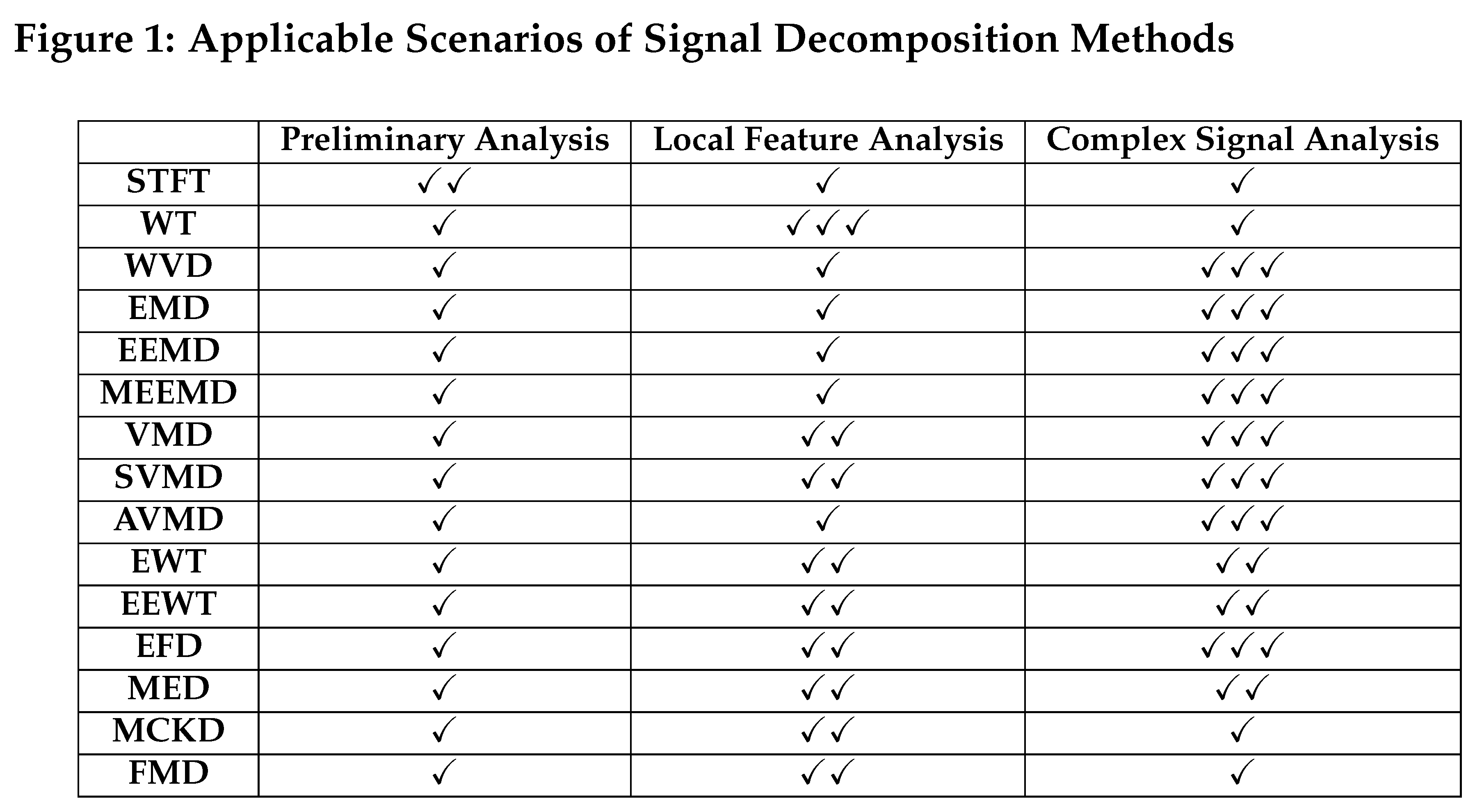

Table 1.

Applicable scenarios and optimization methods for various signal decomposition techniques.

Table 1.

Applicable scenarios and optimization methods for various signal decomposition techniques.

| Method |

Applicable Scenarios |

Optimization Methods |

| STFT |

Preliminary analysis and signal feature extraction |

Multi-window techniques, linear frequency modulation Gaussian windows |

| WT |

Local signal feature analysis |

Optimization of wavelet basis function selection |

| WVD |

Single-component linear frequency-modulated signals |

Cross-term suppression methods (e.g., DMD-WVD) |

| EMD |

Complex signal analysis |

Noise-assisted methods (e.g., EEMD), parameter optimization |

| EEMD |

Complex signal analysis |

Parameter optimization (e.g., adaptive noise bandwidth), hardware acceleration |

| MEEMD |

Multi-physical field signal fusion |

Parameter optimization, multi-signal synchronous processing |

| VMD |

Complex signal analysis |

Parameter optimization (e.g., particle swarm optimization), multi-variable signal processing |

| SVMD |

Complex signal analysis |

Parameter self-adaptive update, minimum bandwidth constraint |

| AVMD |

Complex signal analysis |

Parameter self-adaptive update, optimization algorithms (e.g., differential evolution) |

| EWT |

Complex signal analysis |

Optimization of filter design, multi-variable signal processing |

| EEWT |

Complex signal analysis |

Parameter optimization, multi-signal synchronous processing |

| EFD |

Complex signal analysis |

Optimization of spectral segmentation, noise suppression |

| MED |

Random pulse signals |

Noise suppression methods (e.g., wavelet threshold), parameter optimization |

| MCKD |

Periodic fault signals |

Fault cycle estimation optimization, noise suppression |

| FMD |

Complex signal analysis |

Parameter optimization, multi-variable signal processing |

2. Non-Parameterised Time-Frequency Analysis

2.1. Short-Time Fourier Transform

2.1.1. Definition

The Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) provides a local time-frequency analysis by sliding a window function over the signal and performing Fourier transforms segment by segment. The definition is as follows:

1.Continuous-Time Signal For a continuous signal

, the STFT is defined as:

where: -

is the time position parameter, indicating the center of the window function. -

f is the frequency variable. -

is the window function (such as a rectangular window or Hamming window), used to extract a local segment of the signal around time

.[

3]

2.Discrete-Time Signal For a discrete signal

, the discrete form of the STFT is:

where: -

m is the discrete time frame index. -

k is the discrete frequency index. -

N is the length of the window function or the number of FFT points. -

is the discrete window function, which slides with

m.

Key Points

Time-Frequency Analysis: The STFT divides the signal into short segments, and each segment is transformed into the frequency domain via Fourier transform to reveal how frequency components vary over time.

Role of the Window Function: It restricts the signal to a local time segment, balancing time resolution and frequency resolution (the narrower the window, the higher the time resolution and the lower the frequency resolution).

2.1.2. Application

In recent years, the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), as a significant form of the Fourier Transform, has witnessed remarkable and rapid development in its research and application fields.

Firstly, the integration with classical models elevates their performance to a higher level while better aligning with signal characteristics. For instance, a method that first processes the signal using STFT and further integrates it with Google-Net CNN [

4] has demonstrated in experimental results that this innovation not only enhances the accuracy of signal processing but also effectively reduces the false alarm rate. Another study significantly improves diagnostic accuracy by combining STFT with CNN [

5]. These achievements fully showcase the unique advantages of STFT in enhancing signal processing performance.

Furthermore, significant breakthroughs have been made in optimizing the time-frequency resolution of STFT. The introduction of the ASTFT-CMGW-FVVA method [

6], which cleverly employs multi-window techniques and linear frequency modulation Gaussian windows, notably improves time-frequency resolution, enabling more refined signal analysis. Meanwhile, the integration of STFT into models has played a pivotal role in bearing health assessment and enhancing the time resolution of PET detectors. An autoencoder modeling approach based on STFT and ensemble strategies [

7] effectively extracts deep vibration features of bearings. Another study combines STFT with residual neural networks [

8], significantly improving time-of-flight estimation and coincidence time resolution for PET detectors. These results adequately demonstrate the significant value and application potential of STFT in the era of deep learning.

STFT also plays a crucial role in sparse representation and synchrosqueezing transforms. By combining these techniques with STFT, researchers have achieved optimized signal processing and applications [

9]. This innovation not only expands the application scope of STFT but also introduces new ideas and methods to the field of signal processing. Target localization algorithms represent another important area of STFT application. Researchers have proposed an improved target localization algorithm based on STFT [

10], which significantly enhances the accuracy of target instantaneous frequency estimation and localization by dynamically adjusting the window function and introducing a new distribution estimator. This achievement provides robust technical support for fields such as target localization and tracking.

Beyond the aforementioned applications, STFT also plays a vital role in signal processing decomposition, linear axis misalignment diagnosis, and train wheel anomaly detection. A decomposition method based on STFT [

11] improves the time and frequency resolution of signal processing. Another study, based on servo motor current data and an STFT-based linear axis misalignment diagnosis method [

12], achieves sensorless fault diagnosis. Additionally, a train wheel anomaly detection method using STFT and unsupervised learning algorithms [

13] effectively monitors wheel health. Furthermore, STFT is applied to analyze multi-time scale variations [

14], further expanding its application scope.

Notably, researchers have also conducted innovative studies by combining STFT with fractal theory and the uncertainty principle. They have investigated the fractal uncertainty principle of STFT and Gaussian windows [

15] and explored its application in discrete Gaussian Gabor multipliers. This innovation not only provides new perspectives and methods for STFT research but also brings new insights to the study of fractal theory and the uncertainty principle.

Lastly, many researchers have deeply developed and innovated the underlying algorithms of STFT. Some researchers have introduced ST-QPFT and studied the fundamental properties and uncertainty inequalities of STFT, contributing to the field of short-time quadratic phase Fourier transforms [

16]. Another study proposes the FrFTSG method related to short-time fractional Fourier transforms [

11], improving the time and frequency resolution of signal processing. These innovative achievements not only enrich the theoretical framework of STFT but also provide strong support for its further optimization in practical applications.

2.1.3. Strength and Weakness

The Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) offers numerous advantages in signal processing within the field of structural health monitoring:

Firstly, STFT provides excellent time-frequency resolution, allowing signals to be represented in detail in both the time and frequency domains. This is particularly crucial for structural health monitoring, as the response signals of structures often exhibit non-stationary characteristics when subjected to external excitations or internal damages. Traditional Fourier transform methods are ineffective in processing such non-stationary signals, whereas STFT can accurately capture the temporal variations in signals, providing a solid basis for structural health assessment.

Secondly, STFT is computationally efficient. Compared to other time-frequency analysis methods, STFT has relatively low complexity, enabling it to play a significant role in real-time applications. In structural health monitoring systems, real-time performance is a key indicator, as timely and accurate detection of structural damages is vital for ensuring structural safety. The efficiency of STFT enables it to meet this requirement, providing strong support for real-time structural health monitoring.

However, the Short-Time Fourier Transform also has some limitations in signal processing within the field of structural health monitoring:

One notable drawback is the window effect. The analysis results of STFT are highly dependent on the choice and length of the window function. In structural health monitoring, different window functions and lengths may lead to variations in time-frequency resolution, thereby affecting the accuracy of damage identification. Therefore, careful consideration is needed when selecting the window function and length to ensure consistent and accurate analysis results. Another key limitation is the inherent trade-off between time and frequency resolution. Due to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, STFT cannot achieve optimal resolution in both the time and frequency domains simultaneously. In structural health monitoring, certain damages may exhibit rapidly changing characteristics, requiring time-frequency analysis methods to capture high-frequency components of signals within short periods. However, the performance of STFT in this aspect may be limited, leading to inaccurate identification of certain rapidly changing damage features.

Furthermore, STFT struggles to accurately capture the time-frequency features of highly non-stationary signals, especially those with abrupt or transient components. In structural health monitoring, certain damages may cause abrupt or transient changes in signals, requiring time-frequency analysis methods to sensitively capture these changes. However, STFT may have deficiencies in this regard, leading to inaccurate identification of certain damage features.

To address these limitations, STFT often needs to be combined with complementary methods, such as wavelet transforms or adaptive time-frequency techniques. These methods can compensate for the shortcomings of STFT in terms of time-frequency resolution and capture of abrupt signals, improving its performance in complex signal analysis scenarios. Despite these challenges, STFT remains a fundamental and widely used time-frequency analysis tool. Owing to its advantages of simplicity, efficiency, and broad applicability, it plays a significant role in signal processing within the field of structural health monitoring.

2.2. Wavelet Transform

2.2.1. Definition

Wavelet Transform is a time-frequency analysis method used to analyze the local characteristics of non-stationary signals. Different from Fourier Transform, Wavelet Transform represents the signal through a set of scalable and shiftable wavelet functions, thereby being able to provide high-resolution analysis simultaneously in time and frequency. Wavelet Transform can be divided into Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) and Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT). The former is mainly used for signal analysis, while the latter is often used in signal compression and feature extraction.

2.2.2. Application

The emergence of the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) has caused a tremendous stir. The number of research papers on wavelet transform-related directions far exceeds that of similar signal processing models. Moreover, optimized models based on DWT have emerged in an endless stream. One such method is the identification of homologous acoustic emission signals based on Synchrosqueezing Wavelet Transform Coherence (SWTC). This method aims to improve the accuracy of identifying homologous acoustic emission signals in structural health monitoring, thereby enhancing the precision of damage localization [

17]. Additionally, an unsupervised tunnel damage identification method based on Convolutional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) and wavelet packet analysis has been proposed, with experimental results validating its efficiency and accuracy [

18].

The integration of wavelet analysis with deep learning models has led to a new breakthrough. SWT [

19] represents an innovative approach for bearing fault diagnosis, which combines wavelet packet transform with convolutional neural networks and further optimizes network parameters through a simulated annealing algorithm. The Swin Residual Network (WSRN) based on multi-level Discrete Wavelet Transform has been employed to reconstruct continuously missing data [

20]. By replacing the traditional sampling layers with multi-level DWT, this approach significantly enhances the recovery of weak signals and the extraction of multi-scale features, thereby greatly improving the accuracy of data reconstruction.

In the field of structural health monitoring, DWT has proven to be a powerful tool. However, its accuracy heavily relies on the selected wavelet basis function and the number of vanishing moments, posing significant challenges in practical applications. To address this issue, a method [

21] cleverly combines statistical properties with DWT, markedly improving the accuracy of steel beam crack identification.

Lastly, Generalized Morse Wavelets have found widespread application in fields such as dynamic system analysis [

22]. Their unique time-frequency localization characteristics and flexible multi-scale analysis capabilities make them indispensable tools for signal processing and analysis. By adjusting parameters such as symmetry and width, Generalized Morse Wavelets can optimize the analysis of specific signals, providing more accurate signal feature extraction and diagnostic information. These wavelets demonstrate their powerful capabilities through fine time-frequency analysis of non-stationary signals in complex dynamic systems, revealing the dynamic behavior characteristics of the system across different time scales and frequency ranges. This is crucial for understanding the operational mechanism of the system, modeling and simulating the system, and ultimately optimizing system performance.

2.2.3. Strength and Weakness

The application of wavelet transform in the field of structural health monitoring (SHM) presents multiple advantages and disadvantages, with its strengths particularly prominent: Firstly, wavelets exhibit excellent time-frequency localization characteristics. This property enables wavelet transform to perform high-resolution analysis simultaneously in both time and frequency domains, providing a unique advantage for processing non-stationary signals. In SHM, structural responses are often influenced by various factors, resulting in non-stationary signals. Wavelet transform can therefore more accurately capture the changing features of these signals, providing strong support for structural condition assessment. Secondly, wavelets facilitate multi-scale analysis. By adjusting the scale and position of the wavelet function, signals can be decomposed at different scales, thereby extracting hierarchical features. These features can reflect damage conditions and performance changes in the structure at different scales, providing rich information for SHM and damage identification. Furthermore, the flexibility of wavelets is another significant advantage. The diversity of wavelet basis functions allows for the selection of appropriate wavelet bases for transformation based on specific signal types and requirements. In the field of SHM, different structural types and damage forms may require different wavelet bases to better represent signal characteristics, and the flexibility of wavelets satisfies this need.

Notably, the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) possesses high computational efficiency. This characteristic makes wavelet transform highly potential for real-time SHM. Especially in signal compression and feature extraction, DWT can efficiently process large amounts of data, providing rapid and accurate analysis results for online monitoring and damage warning of structures.

However, the application of wavelet transform in the field of SHM also faces some challenges. Firstly, the selection of wavelet basis functions is crucial. Different wavelet basis functions have significant impacts on analysis results, necessitating professional knowledge and insight to choose appropriate ones. In practical applications, experts in the field of SHM need to make careful selections based on specific circumstances. Secondly, the choice of parameters in wavelet transform (such as scale and position) has a substantial influence on the results. However, a rigorous methodology for this process is currently lacking. This may lead to instability and inaccuracy in analysis results, necessitating further research and exploration to refine this method. Lastly, the sensitivity of wavelets to noise is also a concern in their application. In SHM, signals are often contaminated with noise due to environmental noise and measurement errors. Wavelet transform may be interfered by noise when processing these noisy signals, leading to distorted analysis results. Therefore, complementary denoising techniques need to be integrated to mitigate the impact of noise on analysis results and improve the accuracy and reliability of wavelet transform in SHM .

2.3. Wigner-Ville Distribution

2.3.1. Definition

The Wigner-Ville Distribution (WVD) is a sophisticated time-frequency analysis technique employed to examine the time-frequency properties of non-stationary signals. It offers a means to simultaneously visualize both temporal and spectral information by transforming the signal into the time-frequency domain. The WVD is formally defined as follows:

where

is the input signal, * is the complex conjugation, and

t and

f are the time and frequency variables, respectively.

2.3.2. Application

The development of the Wigner-Ville Distribution (WVD) in the field of structural health monitoring (SHM) exhibits trends of diversification, deepening, and innovation.

The application of the WVD in SHM is becoming increasingly widespread. From traditional signal processing to the enhancement of deep learning models, and further to the integration with other advanced technologies such as Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD), Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), the applications of the WVD in the field of structural health continue to expand. These applications not only improve the accuracy and efficiency of signal processing but also provide more comprehensive and accurate data support for SHM. Ref.[

23] employs the Smoothed Pseudo Wigner-Ville Distribution (SPWVD) to enhance deep learning models. The DMD-WVD method [

24] combines Dynamic Mode Decomposition with the Wigner-Ville Distribution to eliminate cross-terms.

As research deepens, the technical methods of the WVD continue to innovate. The introduction of the Quadratic Chirp-Scaled Wigner Distribution (QSWD) [

25] further enhances the advantages of signal detection. In combination with other deep learning models, time-frequency analysis methods for partial discharge signals based on VMD and WVD [

26] have emerged, as well as the integration of the WVD with CNNs for classification [

27], specifically applied to composite material damage classification methods [

28]. Additionally, there are methods based on the Polynomial Wigner-Ville Distribution [

29], hybrid Wigner-Ville distributions defined in the octonion domain [

30], and other innovative technical approaches that provide new ideas and methods for SHM.

The development of the WVD in the field of structural health is also reflected in the depth of theoretical research. Researchers have not only conducted in-depth studies on the WVD itself but also combined it with other mathematical and physical theories to explore its application potential in SHM. For example, the study of the uncertainty principle of the Coupled Fractional Wigner-Ville Distribution (CFrWVD) [

31] helps to better understand the behavior of the WVD in complex signal analysis; the combination of the WVD with theories such as the Quaternion Linear Canonical Transform (QOLCT) [

32] also provides new perspectives and methods for signal processing. The emergence of the WVD in special mathematical domains, such as the study of the interaction between the two-dimensional hypercomplex WVD and the quadratic phase Fourier transform [

24], is also noteworthy.

Finally, in SHM, real-time performance and accuracy are two crucial indicators. The WVD plays a significant role in enhancing these two aspects. For instance, the proposal of the Short-Time Wigner-Ville Distribution (STWD) [

33] method provides a new approach for real-time signal processing, enabling SHM to respond more promptly to changes in structural conditions.

2.3.3. Strength and Weakness

High time-frequency resolution and energy concentration

Precision in instantaneous frequency analysis

Mathematical completeness and cross-term interference

The advantages of the Wigner-Ville Distribution (WVD) in structural health signal processing are evident.

Firstly, it possesses high time-frequency resolution and energy concentration [

34]. The WVD directly reflects the distribution of signal energy in the time-frequency plane through the Fourier transform of the instantaneous correlation function, without the constraints of a window function, thereby breaking through the limitations of time-frequency resolution imposed by the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) and wavelet transforms. For single-component linear frequency-modulated signals, such as the impulse response generated by structural damage, the time-frequency energy concentration of the WVD reaches theoretical optimality, enabling clear capture of high-frequency transient components, such as nonlinear vibrations resulting from crack propagation or bolt loosening.

Furthermore, it exhibits precision in instantaneous frequency analysis [

35]. The quadratic nature of the WVD allows it to directly represent changes in the instantaneous frequency of a signal, such as the time-varying characteristics of structural modal frequencies or frequency modulation phenomena in nonlinear vibrations. Compared to linear time-frequency methods (e.g., STFT), the WVD offers higher accuracy in the analysis of frequency-hopping signals and rapid frequency changes.

Additionally, it is characterized by mathematical completeness and information richness. The WVD satisfies the marginal conditions (the integrals of time and frequency energy equal the total signal energy) and possesses phase shift invariance. The Fourier transform of its autocorrelation function can be directly used for modal parameter identification and damage localization. Moreover, the real-valued nature of the WVD simplifies the physical interpretation of the energy density distribution, making it suitable for energy decay analysis in structural health monitoring. Lastly, it demonstrates adaptability as a non-parametric method. The WVD does not require pre-assuming a signal model, making it suitable for extracting unknown damage features under complex operating conditions. For example, in composite material delamination damage monitoring, the WVD can adaptively analyze the time-frequency characteristics of nonlinear acoustic emission signals without relying on a preset damage model.

Of course, the WVD has limitations and challenges. Firstly, there is the interference of cross-terms [

26]. The bilinear nature of the WVD leads to the generation of spurious cross-terms in the time-frequency distribution of multicomponent signals (such as multimode vibrations or environmental noise interference). These cross-terms can obscure real damage features, potentially leading to misjudgment, especially in the presence of multiple coexisting damages or strong noise environments. For instance, when multi-point damage signals in a bridge structure overlap, cross-terms may form pseudo-frequency peaks, interfering with damage localization [

36].

Secondly, there is the issue of non-positivity of energy and ambiguity in physical meaning. Although the WVD is a real-valued distribution, its energy density may exhibit negative values, conflicting with the concept of energy in a physical sense and limiting its application in quantitative energy analysis, such as damage severity assessment.

Finally, there are limitations in computational complexity and real-time performance. The high resolution of the WVD relies on instantaneous correlation calculations over the entire data length, leading to low processing efficiency for long time-series signals (such as long-term structural monitoring data) and making it difficult to meet real-time monitoring requirements.

3. Adaptive Time-Frequency Analysis

3.1. Empirical Mode Decomposition and Optimization Models

3.1.1. Empirical Mode Decomposition

3.1.1.1. Definition

Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD), proposed by Huang et al. [

37], is an adaptive signal processing method that decomposes a signal into a set of Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs), each representing a natural oscillation mode in the signal. The EMD method extracts different frequency components from the signal through an iterative process based on the signal’s local characteristic time scale.

An IMF, which is the basic function obtained during the EMD decomposition process, must satisfy the following two conditions:1ïijL’Relationship between the number of extrema and the number of zero-crossings: They must be equal or differ by at most one.2ïijL’Mean of the local envelope: At any point, the mean of the envelope defined by the local maxima and minima is zero.[

38] It is worth noting that IMFs are determined by the signal itself, rather than predefined kernel functions, making EMD an adaptive signal processing method.

The formula for the EMD method can be expressed as:

where: -

is the original signal, -

is the

i-th IMF, -

is the residual term, representing the part of the signal not decomposed into IMFs, -

N is the number of IMFs.

3.1.1.2. Application

In recent years, researchers have applied Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) in conjunction with various network models.

A multitude of methods have emerged for sequence prediction by integrating EMD with neural networks. Typically, EMD is used to decompose signals into modal functions, which are then analyzed using classical networks. One approach combines EMD with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural networks to estimate the State of Health (SOH) and predict the Remaining Useful Life (RUL) of lithium-ion batteries. EMD is utilized to decompose the voltage signals of lithium-ion batteries and extract Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs). These IMFs are then processed by an LSTM network to predict the battery’s SOH and RUL [

39]. Another method involves a model that combines EMD with Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) neural networks. EMD is used to decompose time series data and extract IMFs, which are subsequently processed by a GRU network to enhance prediction accuracy and robustness [

40]. Additionally, there is a predictive model that combines EMD with Least Squares Support Vector Regression (LSSVR). EMD is used to decompose time series data, extract IMFs and residuals, which are then individually predicted by LSSVR. The final prediction is obtained by aggregating these individual predictions [

41]. Furthermore, a hybrid model that integrates three classical modelsâĂŤEMD—EMD, LSTM, and Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA)âĂŤis used for wind speed prediction. EMD is used to decompose wind speed data and extract IMFs, LSTM processes the time series data, and ARIMA captures the linear trends in the data. The overall model improves prediction accuracy and stability [

42].

Moreover, research on noise reduction methods is also making progress. One noise reduction method combines Uniform Phase Empirical Mode Decomposition (MUPEMD) with a Genetic Algorithm-Dynamic Zero-Phase Interval Filtering algorithm (GA-DZPIF) to improve the processing efficiency of ship-radiated noise signals and mitigate modal aliasing issues. MUPEMD is used to decompose the signals, while GA-DZPIF is used to filter the single-mode components, with Structural Similarity (SSIM) used as an evaluation metric [

43]. Additionally, a method based on Improved Ensemble Noise Reconstruction Empirical Mode Decomposition (IENEMD) and Adaptive Threshold Denoising (ATD) has been proposed. This method combines IENEMD and ATD to extract weak fault features of rolling bearings. IENEMD is used to decompose the signals, while ATD is used for denoising. The effectiveness and robustness of this method have been verified through simulation experiments and practical cases [

44].

Furthermore, Guo Junyu et al. have proposed a hybrid scheme for rolling bearing fault prediction based on Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) and Kernel Principal Component Analysis (PCA). This hybrid scheme combines Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Multiscale Interpolation (CEEMD-MsI) and PCA to construct a nonlinear health indicator, and uses a dual-channel transformer network and convolutional block attention module to extract multi-domain features for rolling bearing fault prediction [

45].

3.1.1.3. Strength and Weakness

Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) is the most classic adaptive time-frequency analysis technique. Compared with the aforementioned non-parametric dependent time-frequency analysis techniques, it can decompose signals based on their inherent characteristics without the need to preset the number of modes or frequency ranges. This method is particularly suitable for processing signals with complex nonlinear and multiscale characteristics. Furthermore, the decomposition process of EMD is driven by data iteration, based on the local maxima and minima of the signal. During this process, the signal is naturally decomposed into a series of intrinsic mode functions (IMFs) without the need for additional prior knowledge or model parameter adjustments.

Compared with traditional Fourier Transform and Wavelet Transform, the mode mixing phenomenon in EMD is reduced. Each IMF represents a local manifestation of the signal within a specific frequency range. Although they are not completely orthogonal, they ensure a certain degree of frequency-time resolution of the signal. In terms of handling boundary effects, EMD has also undergone certain optimizations. By specially processing the signal boundaries, the influence of boundary effects on the decomposition results is reduced. In contrast, the aforementioned time-frequency analysis methods may encounter issues such as reduced resolution or spectrum leakage at signal boundaries. Additionally, the IMFs obtained after EMD decomposition can be reconstructed through simple addition operations with high reconstruction accuracy. This characteristic gives EMD advantages in applications such as signal denoising, feature extraction, and pattern recognition. It is particularly noteworthy that EMD is especially suitable for processing nonlinear and non-stationary signals, capable of capturing complex patterns and transient features in the signal. In contrast, Wavelet Transform and Short-Time Fourier Transform may require more complex multiscale analysis when processing nonlinear signals.

Finally, regarding the adaptability of EMD, it can process any type of signal, including process control [

46,

47], modeling [

48,

49], surface engineering, wind speed prediction [

50,

51], system identification [

52,

53], bearing diagnosis [

54], etc. This excellent adaptability makes its application versatile.

Of course, as the most basic adaptive time-frequency analysis technique, EMD still has much room for development. Its disadvantages include endpoint effects and energy non-conservation, which are inherent to the EMD algorithm itself. Since IMFs are not strictly orthogonal, the total energy of the decomposed IMFs may not match the energy of the original signal, leading to energy non-conservation in some cases. For example, in the study by Yaguo Lei [

38], simulations and analyses of IMFs revealed distortions at both ends of the IMFs, with the decomposition results exhibiting distortions at both ends. Furthermore, another prominent disadvantage of EMD is the mode mixing problem, where a single IMF contains oscillations of different scales, or oscillations of similar scales are distributed across different IMFs. This is caused by the intermittency of the signal. As stated by Huang et al. [

37], intermittency can lead to severe mixing of time-frequency distributions, making the physical meaning of individual IMFs ambiguous.

3.1.2. Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition

3.1.2.1. Definition

Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD) is an improved method of Empirical Mode Decomposition designed to address the mode mixing issue that may arise when EMD processes signals. EEMD adds white noise of a certain amplitude to the signal to be analyzed and performs multiple EMD decompositions, which are then averaged to obtain more stable and accurate intrinsic mode functions. EEMD retains the adaptive characteristics of EMD, enabling decomposition based on the local characteristic time scales of the signal itself.

3.1.2.2. Application

Extensive experimental research on prediction related to Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD) is being conducted. Various models for prediction have emerged. Researchers have adopted data-driven models such as EEMD-RF, EEMD-ANN, and EEMD-GBM for precise prediction and conducted sensitivity analyses to understand model behavior [

55]. Another study employed a method that combines EEMD with SVM [

56]. Similarly, the W-EEMD-ARIMA model achieved the same objective [

57]. A method using the EEMD-ANN model for prediction has been proposed, aiming to address inherent challenges in prediction, such as difficulties in model construction, low prediction accuracy, and high computational intensity [

58].

EEMD exhibits good denoising performance. The effectiveness of the EEMD-based denoising method proposed in [

59] was compared with various wavelet transform-based threshold denoising methods, demonstrating the potential of EEMD in signal denoising applications. A study combined the EEMD-Independent Component Analysis (ICA) method to effectively remove artifacts [

60]. Furthermore, there are other innovative models and applications. Such as a EEMD-TCN machine learning method has been utilized [

61].

3.1.2.3. Strength and Weakness

Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD), as an enhanced version of the classical Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD), demonstrates unique application value in structural health signal processing while facing several limitations that require urgent resolution. Its core advantage lies in effectively alleviating the mode mixing issue caused by signal intermittency in traditional EMD through multiple additions of Gaussian white noise to the original signal and ensemble averaging. For instance, in the analysis of bridge vibration signals with multiple damage sources, EEMD can separate high-frequency transient components from crack propagation and low-frequency modulated signals from bolt loosening into distinct Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs), significantly improving the accuracy of damage feature extraction. This noise-assisted mechanism not only enhances decomposition stability but also preserves EMD’s adaptability, enabling it to process nonlinear, non-stationary signalsâĂŤsuch as acoustic emission signals from composite material delamination or dynamic structural responses under seismic excitationâĂŤwithout predefined basis functions. Furthermore, the decomposed IMFs possess clear multi-scale physical meanings: high-frequency components typically correspond to transient features of localized structural damage (e.g., impact components in early-stage gearbox faults), while low-frequency components reflect global structural vibration modes, providing reliable references for early detection of fatigue cracks in wind turbine blades.

However, the engineering application of EEMD still faces multiple challenges. First, its performance heavily depends on manually set noise intensity and decomposition iterations. Improper parameter selection may lead to signal features being obscured by noise or incomplete modal separation. For example, in rail crack monitoring, excessive noise amplitude settings could contaminate high-frequency IMFs related to damage, compromising diagnostic accuracy. Second, the algorithm’s computational complexity increases significantly, with single decomposition time approximately a hundredfold that of EMD, limiting real-time processing capabilities for massive datasets in long-term monitoring scenarios such as bridges and dams. Although boundary distortion in IMFs caused by end effects can be partially mitigated through mirror extension or local mean prediction (e.g., OFCEEMDAN algorithm), signal anomalies under extreme operating conditions may still interfere with envelope fitting precision. Additionally, residual noise contamination from repeated noise additions and energy non-conservation in IMFs might affect the reliability of quantitative damage assessment, necessitating post-processing optimization through wavelet threshold denoising or energy compensation algorithms.

To address these limitations, current research focuses on improvements from two dimensions: algorithm optimization and engineering implementation. Regarding noise-assisted strategies, Complementary Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (CEEMD) reduces residual noise by 40% while preserving modal separation advantages through symmetric positive-negative noise pair addition, significantly enhancing signal-to-noise ratio. Adaptive parameter adjustment methods dynamically optimize noise amplitude based on signal entropy or energy distribution, reducing manual intervention requirements. The introduction of hardware acceleration technologies provides new pathways for real-time breakthroughsâĂŤfor instance, GPU-based parallel computing can improve long-sequence signal processing efficiency by 5-8 times, while the development of FPGA embedded modules meets low-power demands for field monitoring equipment. Multi-sensor fusion strategies further expand EEMD’s application boundaries. Multivariate EEMD achieves cross-scale feature extraction in composite damage diagnosis of wind turbine blades through joint analysis of multi-physical field data (vibration, acoustic emission, and fiber optic sensing), with false alarm rates reduced to below 3%.

Future research should prioritize three directions: First, constructing parameter self-optimization networks through deep learning, utilizing convolutional neural networks to dynamically analyze signal characteristics and generate optimal noise parameters. Second, establishing IMF energy correction models to address quantitative assessment deviations caused by modal energy leakage. Third, developing multi-physical field coupled diagnostic frameworks that incorporate environmental parameters such as temperature and strain into the EEMD decomposition process, building a time-space-frequency joint analysis system for structural health status. Through the integration of algorithmic innovation and engineering practice, EEMD is expected to achieve deeper engineering applications in fields such as aerospace composite material monitoring and super high-rise building dynamic response analysis, providing robust and precise signal processing tools for structural health monitoring.

3.1.3. Multivariate Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition

3.1.3.1. Definition

Modified Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (MEEMD) is an improved method of empirical modal decomposition. It evenly distributes the extrema of the signal by adding pairs of positive and negative Gaussian white noise and reduces the number of spurious components through multiple trials. MEEMD not only inherits the adaptability and the ability to address mode mixing issues from Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD), but also further enhances the accuracy and stability of the decomposition by introducing a median operator.

The specific steps are as follows: (1)Adding Gaussian white noise: Pairs of positive and negative Gaussian white noise are added to the original signal, ensuring that the noise has a mean of zero and equal standard deviations. (2)Empirical modal decomposition: Multiple empirical modal decompositions are performed on the noise-added signal, with each decomposition yielding a series of Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) and a residual.(3)Median operation: A median operation is applied to the IMFs and residuals obtained from each decomposition to produce the final IMFs and residual.

3.1.3.2. Application

Multivariate Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (MEEMD) effectively addresses the complexity and non-stationarity of signals by decomposing composite waves into distinct components, thereby facilitating the examination of their spatiotemporal heterogeneity and separation characteristics [

62].

Research has also leveraged this attribute, employing MEEMD to manage the nonlinear and non-stationary nature of Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) data, integrating MEEMD with the Geographically and Temporally Weighted Regression (GTWR) method [

63].

Innovatively, MEEMD has been applied to non-destructive testing. By processing data obtained from pulsed thermography with MEEMD, signals of different frequency components can be separated. Due to the differences in thermal responses between defective and non-defective regions, the decomposition by MEEMD better highlights these discrepancies, thereby enabling non-destructive testing and enhancing the accuracy and reliability of detection [

64]. A method combining MEEMD and Prony [

65], wherein MEEMD decomposes the signal and introduces permutation entropy to detect randomness, followed by the reconstruction of the remaining Intrinsic Mode Function (IMF) components, has also achieved innovative progress.

Furthermore, MEEMD is extensively utilized for prediction [

66]. A sequence prediction method based on the MEEMD-Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network model has been proposed. Another prediction approach employs a model based on MEEMD-LSTM-Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) [

67]. MEEMD initially decomposes the data, LSTM handles the dynamic changes in time series, and MLP models complex nonlinear relationships. The synergy among these three enhances prediction accuracy and stability under different conditions and data characteristics. A prediction model based on improved MEEMD and Quasi-Affine Transformation (QUATRE) optimized Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BILSTM) network [

68] has also been developed. In this model, MEEMD processes photovoltaic output data to extract key features, QUATRE optimizes these features, and BILSTM captures forward and backward dependencies in time series data.

Simultaneously, MEEMD is applied to fault detection. A rotor fault detection method based on MEEMD energy entropy and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) has been developed. MEEMD decomposes the operational signals of the rotor and calculates energy entropy to construct a feature vector reflecting the energy distribution characteristics of the signal [

69]. Another fault diagnosis method for reciprocating machinery based on improved MEEMD-SqueezeNet has also been proposed [

70].

Researchers have further optimized MEEMD focusing on the crucial issue of noise in signal processing. To address the noise reduction problem in tunnel blasting vibration signals, a complete method based on MEEMD-Least Mean Squares (LMS) has been developed [

71]. Additionally, a method combining MEEMD and Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) is used to remove noise from high slope deformation data. MEEMD is employed for the initial decomposition of high slope deformation data, and SVD further processes the decomposed matrix to effectively eliminate noise, fully preserving the intrinsic details of the deformation data and providing a more accurate basis for subsequent data analysis and processing [

72].

3.1.3.3. Strength and Weakness

Suppression of modal aliasing and fusion of multi-physical field signals

Parameter sensitivity, residual noise, and endpoint effect

algorithm generalization and Poor adaptability to extreme working conditions

On the one hand, MEEMD (Multivariate Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition) possesses multiple advantages. Firstly, it excels in mode mixing suppression and computational efficiency enhancement. By adopting a multivariate signal ensemble decomposition strategy and incorporating a median operator to integrate and average the decomposition results of multiple signal sets, MEEMD effectively reduces spurious components induced by the addition of random noise in EEMD (Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition). Secondly, it enhances multi-physical field signal fusion and robustness. The multivariate signal ensemble nature of MEEMD enables it to process multi-channel sensor data simultaneously (such as vibration, acoustic emission, and fiber optic sensing). Through joint analysis of time-frequency characteristics of signals from different physical fields, it strengthens the identification capability for complex damage patterns (such as the coexistence of composite delamination and metal fatigue). Experiments demonstrate that in the diagnosis of composite damages in wind turbine blades, MEEMD can reduce the false alarm rate to below 3%, significantly outperforming the single-channel EEMD method. Furthermore, its adaptive noise bandwidth design dynamically adjusts to different signal characteristics (such as high-frequency transients or low-frequency slow variations), avoiding the masking of signal features by fixed-bandwidth noise. Additionally, computational cost optimization and real-time performance improvement are achieved. By optimizing the ensemble averaging strategy (such as stage-wise averaging instead of global averaging), MEEMD shortens the computation time by 30%-45% while maintaining decomposition accuracy [

73]. For example, for 24-hour bridge vibration monitoring data, combining MEEMD with GPU parallel computing can enhance processing efficiency by 5-8 times, meeting the requirements of real-time monitoring. This improvement is particularly suitable for long-term health monitoring scenarios, such as dam deformation analysis or aerospace structural fatigue assessment. The main technical challenges of MEEMD are as follows. Firstly, parameter sensitivity and residual noise persistence. The performance of MEEMD still relies on manually set noise bandwidth and the number of ensemble trials. If the noise bandwidth is too wide, it may introduce high-frequency artifacts; if too narrow, it may result in incomplete mode separation. For instance, in rail crack monitoring, improper noise parameter settings can contaminate damage-related high-frequency IMFs (Intrinsic Mode Functions) with noise, reducing the signal-to-noise ratio by about 20%. Moreover, multiple overlays of limited-bandwidth noise may lead to the accumulation of low-frequency residual noise, necessitating post-processing with wavelet threshold denoising or energy compensation algorithms. Secondly, endpoint effects and poor adaptability to extreme conditions. Although MEEMD partially suppresses endpoint distortions through local mean prediction (such as the OFCEEMDAN algorithm), under extreme conditions of strong impact loads or abrupt signal amplitude changes (such as building responses during earthquakes), envelope fitting errors may still cause IMF boundary frequency shifts, affecting damage localization accuracy. Experiments indicate that modal energy leakage in such cases can reach 8Thirdly, hardware resource constraints and algorithm generalization limitations. The multi-channel data processing requirements of MEEMD significantly increase memory usage, posing challenges to the hardware resources of embedded devices (such as wireless sensor nodes). For example, FPGA-implemented MEEMD modules require an additional 20% of logic units for multi-signal synchronous processing, limiting their promotion in low-power scenarios [

73,

74]. Furthermore, the algorithm’s generalization capability for non-stationary signals still needs verification, particularly the decomposition stability under multi-physical field coupling (such as the combined effect of temperature and strain) has not been fully investigated.

3.2. Variational Mode Decomposition and Optimization Models

3.2.1. Variational Mode Decomposition

3.2.1.1. Definition

Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) is a signal processing method proposed by Dragomiretskiy et al. in 2013. VMD decomposes a signal into several Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs), each of which possesses a specific center frequency and bandwidth. The core idea of VMD is to achieve signal decomposition by minimizing the solution to a variational problem, ensuring that each IMF is as concentrated as possible within a certain frequency band[

75].

3.2.1.2. Application

Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) has demonstrated remarkable performance in machinery fault diagnosis, particularly in extracting fault features from rotating machinery such as bearings and gearboxes. By decomposing vibration signals, VMD effectively isolates fault characteristic frequencies and, when combined with methods like envelope spectrum analysis, achieves precise fault diagnosis. For instance, a method for estimating spalling size in rolling bearings based on signal processing techniques has been proposed [

76]. Another example is a natural gas pipeline leak detection method based on optimized VMD and the ConvFormer model [

77].

Furthermore, VMD has been applied to the prediction of structures such as bridges and buildings. For example, by decomposing the vibration response signals of structures, VMD can identify modal changes caused by damage, providing a basis for predictive assessment. To accommodate different prediction scenarios, researchers have also optimized the VMD model in various ways. One study introduced a thermal load time series decomposition and prediction model based on VMD and Fast Independent Component Analysis (FastICA) [

78]. Another proposed a short-term offshore wind speed prediction method based on a hybrid VMD-PE-FCGRU model [

79]. Additionally, a lithium-ion battery health state estimation method based on the MEWOA-VMD and Transformer architecture has been developed [

80]. There is also a concrete dam displacement prediction model based on VMD, TSVR, and GRU [

81]. In another approach, complex power load time series are decomposed into multiple relatively simple subsequences using VMD, and by combining the ICSS algorithm, abrupt and irregular changes in the time series are identified and separated. Finally, neural networks in deep learning are used to predict these subsequences, and the final prediction results are obtained through ensemble learning, significantly improving the accuracy and stability of predictions [

82].

VMD is also widely applied in signal denoising and feature extraction. Thanks to its inherent proficiency in handling noise, VMD excels in these applications. Moreover, researchers are dedicated to optimizing and upgrading VMD using innovative methods. One such method is a signal preprocessing approach based on VMD technology and sample entropy. This method decomposes milling robot response signals into multiple modal components using VMD and then calculates the sample entropy of each component to assess its complexity and irregularity. By setting appropriate thresholds, modal components containing amplitude and frequency modulation (AM-FM) harmonic components can be identified and eliminated, achieving the goals of denoising and signal optimization [

83]. Another method combines VMD, Empirical Wavelet Transform (EWT), and Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) to improve the signal-to-noise ratio of acoustic signals and accurately detect pipeline leak locations. By analyzing and processing signals in different frequency domains, noise can be effectively suppressed, and useful information can be extracted, significantly enhancing the accuracy of leak detection [

84].

A joint denoising method based on VMD parameter optimization has been proposed for removing noise from acoustic signals of high-voltage shunt reactors [

85]. This method integrates VMD, Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise (CEEMDAN), and an Improved Continuous Wavelet Transform (ICWT) structure. The combination of these three methods allows for more effective noise removal from density logging data, improving data resolution and thin-layer identification accuracy [

86]. An optimized VMD algorithm based on Tunable Diode Laser Absorption Spectroscopy (TDLAS) has been developed for signal denoising [

87]. A wavelet threshold function based on the combination of Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) and VMD has been proposed to address noise interference in ultrasonic echo signals [

88]. An adaptive denoising and detrending method based on an Improved Seagull Optimization Algorithm (ISOA) and VMD has been developed for processing signals from nuclear circulating water pump impellers [

89]. VMD can effectively remove trend components from signals, significantly improving the signal-to-noise ratio of nuclear circulating water pump impeller signals while preserving valuable information. Additionally, a photoacoustic spectroscopy second-harmonic signal denoising method that utilizes the Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA) to optimize VMD combined with Wavelet Threshold Denoising (WTD) technology has been proposed, which can improve the detection accuracy and real-time measurement stability of acetylene sensors [

90].

To enhance the performance of VMD, researchers have proposed various parameter optimization methods, such as adaptive parameter selection methods based on Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and genetic algorithms. These methods automatically adjust VMD parameters, thereby improving decomposition accuracy and efficiency. A fault diagnosis method for electric valves in nuclear power plants based on a Random Forest model that integrates VMD, MDI, and ISSA has been proposed [

91]. Another study introduced an ultrasonic machining vibration signal processing method based on SE-PSO-VMD, which improves signal processing efficiency by optimizing VMD parameters [

92].

The pursuit of high anti-interference capability and precision in models is also a direction of model optimization. The Complex Variational Mode Decomposition (CVMD) algorithm has been proposed for analyzing complex-valued data [

93]. VMD can also be used to decompose projectile signals [

94], and by detecting the mathematical model of the skyscreen, the measurement accuracy of projectile muzzle velocity can be improved. Compared with traditional methods, this algorithm has significant advantages in anti-interference capability and measurement accuracy.

3.2.1.3. Strength and Weakness

susceptible to the influences of noise and spurious components

Stability and Noise Resistance

Adaptability and Parameter Controllability

Effective Mitigation of Mode Mixing

The advantages of Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) in the realm of structural health signal processing are manifold.

Firstly, VMD demonstrates a robust capacity to mitigate mode mixing. By integrating a regularization term within a variational optimization framework, VMD effectively curtails the occurrence of mode mixing, a pervasive challenge in signal decomposition, particularly when confronting nonlinear and non-stationary signals. Traditional approaches, exemplified by Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD), are prone to mode mixing due to the perturbations induced by local extrema points. In contrast, Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) dissects the signal into multiple narrowband mode components through the judicious application of frequency domain constraints and bandwidth limitations, thereby significantly reducing the likelihood of mode mixing.

Secondly, VMD distinguishes itself through its adaptability and parameter controllability. It possesses the proficiency to adaptively determine the number of modes and frequency centers, obviating the necessity to rely on envelope calculations predicated on signal extrema points. This attribute endows VMD with heightened flexibility and precision in the processing of complex signals. For instance, within the context of structural health monitoring, VMD has the capability to dynamically adjust decomposition parameters in accordance with the idiosyncrasies of vibration signals, thereby facilitating the extraction of fault features with unparalleled accuracy. Moreover, while the parameters of VMD, such as the penalty factor and bandwidth constraint, necessitate manual calibration, their controllability opens up avenues for extensive optimization in signal processing.

Thirdly, the algorithm embodies stability and resilience against noise. VMD recasts the signal decomposition process as an optimization problem, and through iterative computations, arrives at the optimal solution. This mathematical framework underpins the stability of the algorithm. In the presence of noisy signals, VMD exhibits formidable noise resistance, effectively attenuating the perturbations wrought by noise on decomposition results. For example, in the domain of bearing fault diagnosis, VMD adeptly isolates fault characteristic frequencies, preserving high decomposition accuracy even amidst noisy environments.

Conversely, VMD is not without its limitations in structural health signal processing. Firstly, its efficacy is contingent upon the judicious selection of parameters. Despite its adaptive prowess, the performance of VMD is significantly influenced by the choice of parameters, including the penalty factor () and the number of modes (K). The determination of these parameters often necessitates empirical insight or refinement through optimization algorithms, thereby escalating the complexity and application challenge of the algorithm. For instance, in the analysis of acoustic emission signals emanating from centrifugal pump cavitation, inappropriate parameter configurations may engender inaccurate decomposition results, thereby impeding the extraction of fault features.

Secondly, VMD is encumbered by computational complexity and time costs. While its iterative optimization process ensures decomposition stability, it also imposes substantial computational demands. When confronted with prolonged signals or high-sampling-rate data, the computational onus of VMD escalates markedly, thereby constraining its applicability in real-time monitoring systems.

Lastly, VMD is susceptible to the influences of noise and spurious components. Notwithstanding its noise resistance, decomposition results may still be corrupted in high-noise environments. Furthermore, the decomposition process of VMD may introduce spurious components, which not only exacerbate the complexity of signal processing but may also obscure genuine fault features. For example, in the detection of looseness in threaded connections, the emergence of spurious components may precipitate misjudgments, thereby compromising the accuracy of detection outcomes.

3.2.2. Successive Variational Mode Decomposition

3.2.2.1. Definition

Successive Variational Mode Decomposition (SVMD) is a signal decomposition method proposed by Nazari and Sakhaei [

95], which does not require prior knowledge of the number of modes in the signal. Through an iterative optimization process, SVMD decomposes the signal into multiple Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs), each representing a specific frequency component of the signal.

3.2.2.2. Application

Research on the underlying principles of Self-adaptive Variational Mode Decomposition (SVMD) exhibits a profound level of depth [

96]. One such method is the self-adjusting SVMD, which adaptively updates the mode number K and penalty parameter α based on energy ratio and frequency-domain mode orthogonality, thereby addressing the issues of parameter selection and poor adaptability in the original Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD). Ref.[

97] introduces a novel signal decomposition approach termed Continuous Variational Mode Decomposition (also abbreviated as SVMD in this context), which obviates the need for prior knowledge of the number of signal modes and boasts lower computational complexity and higher robustness. In terms of lateral development, SVMD has been integrated with other network models. One example is a milling chatter detection method based on SVMD and a deep attention information fusion network, which extracts chatter features from multi-channel time-series signal data for detection [

98]. It can also be combined with the Instantaneous Linear Mixture Model, resulting in the SMVMD method, which adaptively extracts joint or common modes from multi-channel signals. Furthermore, SVMD has been combined with other signal processing techniques. An improved Wigner-Ville distribution method based on SVMD [

99] is used for time-frequency analysis of multicomponent signals, reducing cross-terms and enhancing signal reconstruction accuracy. In [

100], a new method called Narrowband Constraint Enhanced Continuous Variational Mode Decomposition (NCESVMD) is proposed, which improves signal decomposition by introducing a minimum bandwidth constraint. Given the inherent characteristics of SVMD, parameter optimization is also a crucial aspect of optimizing the model. In [

101], an Ultra-Weak Fiber Bragg Grating (UWFBG) hydrophone array-enhanced Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) system based on optimized SVMD and matched interference methods is proposed for noise resistance, with SVMD parameters optimized using the RIME algorithm.Ref.[

102] demonstrates the combination of spatial dependency recursive sample entropy and improved wavelet thresholding for noise reduction.

In [

103], researchers introduce a dual-end traveling wave fault location method based on SVMD and frequency-dependent propagation velocity. This method extracts the intrinsic mode functions of the signal through SVMD and uses the Teager energy operator to determine the arrival time of the traveling wave. Additionally, researchers have designed adaptive SVMD algorithms that dynamically adjust decomposition parameters based on signal characteristics to avoid falling into local optimal solutions.

3.2.2.3. Strength and Weakness

Unlike the traditional Variational Mode Decomposition method, SVMD (Successive Variational Mode Decomposition) extracts signals by successively implementing the variational mode decomposition technique. SVMD decomposes multicomponent signals into a series of band-limited Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) in a successive manner, whereas in the VMD method, modes are extracted concurrently. This successive approach eliminates the need for prior knowledge of the number of modes to be extracted, which is a significant advantage in practical applications where the mode count may be unknown or variable[

95].

Moreover, compared to VMD, SVMD reduces the computational burden, especially when dealing with complex signals. In specific applications within the field of structural health signal processing, where certain modes are considered as interference or noise and are not of interest, the concurrent implementation of VMD may lead to a wastage of computational resources. On the other hand, SVMD can extract modes one by one, skipping unnecessary modes, which significantly improves convergence speed and reduces overall computation time[

95].

Furthermore, SVMD overcomes the sensitivity issue of VMD to initialization parameters. As SVMD is less sensitive to the initial values of the modal center frequencies, it can reduce the likelihood of converging to incorrect or duplicate modes, a problem that has been noted by Dragomiretskiy and Zosso in their work[

70]. This robustness enhances the reliability of the decomposition results in structural health monitoring, where accurate mode identification is crucial.

However, SVMD is not without its drawbacks. In some cases, it may get trapped in local optimal solutions, particularly when dealing with signals that have highly similar modal components or when the signal-to-noise ratio is low. This can affect the decomposition effect and lead to inaccurate mode separation. Additionally, the sequential nature of SVMD may limit its parallelization potential, making it less efficient than VMD in applications requiring real-time processing. Despite these limitations, SVMD remains a promising method for structural health signal processing, offering a balance between accuracy, efficiency, and robustness.

3.2.3. Variational Mode Extraction

3.2.3.1. Definition

Variational Mode Extraction (VME) is a signal processing method, and it is a signal processing technique based on variational Bayesian inference. In VME, the modal functions of the signal are treated as latent variables, while the observed signal data are used to estimate the distributions of these latent variables. By maximizing the likelihood function, VME can find the modal function parameters that best fit the signal data.

3.2.3.2. Application

It is noteworthy that a post-processing method for structural health monitoring (SHM) data based on Variational Mode Extraction (VME) has been proposed. This method converts time lags into phase period differences through a variational mode extraction algorithm, enhancing the accuracy and automation of frequency domain analysis. Its effectiveness has been verified in the actual SHM system of the Shanghai Tower [

104].

In other applications, the field of fault analysis has seen extensive use. Researchers have made various optimizations in this domain.

Firstly, deep learning networks have been integrated. For instance, an intelligent fault diagnosis method for rolling bearings based on VME and an improved one-dimensional convolutional neural network (I-1DCNN) has been proposed. By combining VME and I-1DCNN, useful features of bearing vibration signals are extracted from noisy environments, improving the accuracy and computational efficiency of fault diagnosis [

105]. Another method [

106] involves rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on Power Spectral Density-Variational Mode Extraction (PSD-VME), multiclass Relevance Vector Machines (mRVM), and Dempster-Shafer evidence theory. Features are extracted through PSD-VME and classified using mRVM and DS evidence theory, verifying the method’s high classification accuracy with small sample data.

Furthermore, innovations have been made while accurately grasping the advantages of VME. In the multi-fault diagnosis of rolling bearings, a variational mode extraction method based on the convergence trend of Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) has been applied [

107]. The initial center frequency is adaptively determined through the VMD convergence trend graph, and kurtosis is used as an evaluation index to optimize the balance factor, enhancing the accuracy and computational efficiency of fault feature extraction.

Additionally, parameter optimization algorithms have been employed. A parameter-adaptive variational mode extraction method based on Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) has been proposed for bearing fault diagnosis [

108]. Researchers have constructed a comprehensive index, L-KCIE, to optimize VME parameters and verified its effectiveness and superiority in fault feature extraction.

3.2.3.3. Strength and Weakness