This section reflects upon how the approach to design, implement, and evaluate the CNN model for image recognition has been done. It covers the architectural decisions [

14,

15] regarding the design and the technical steps required to build up and optimize the model to classify images correctly. The process was divided into sharply defined stages to eventually provide a clear-cut roadmap that will help take the model from design through implementation, considering both theoretical considerations and practical execution.

3.1. Architecture Design

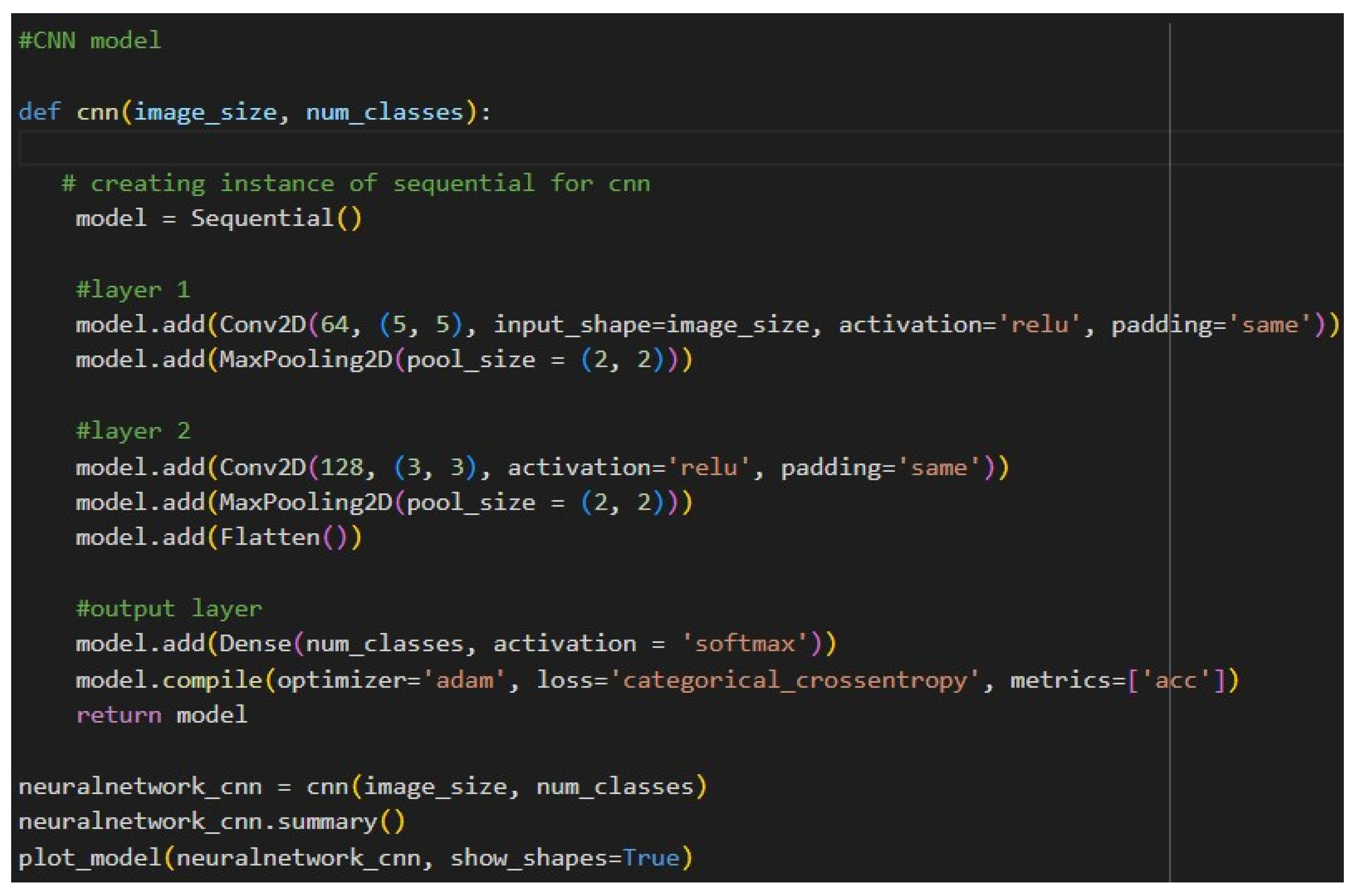

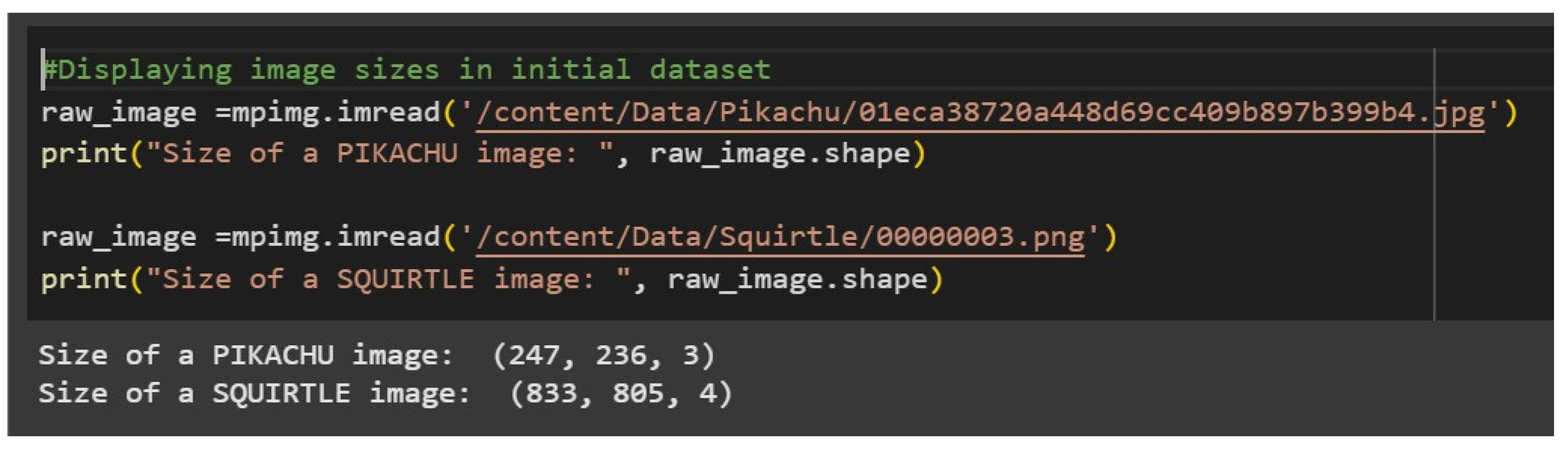

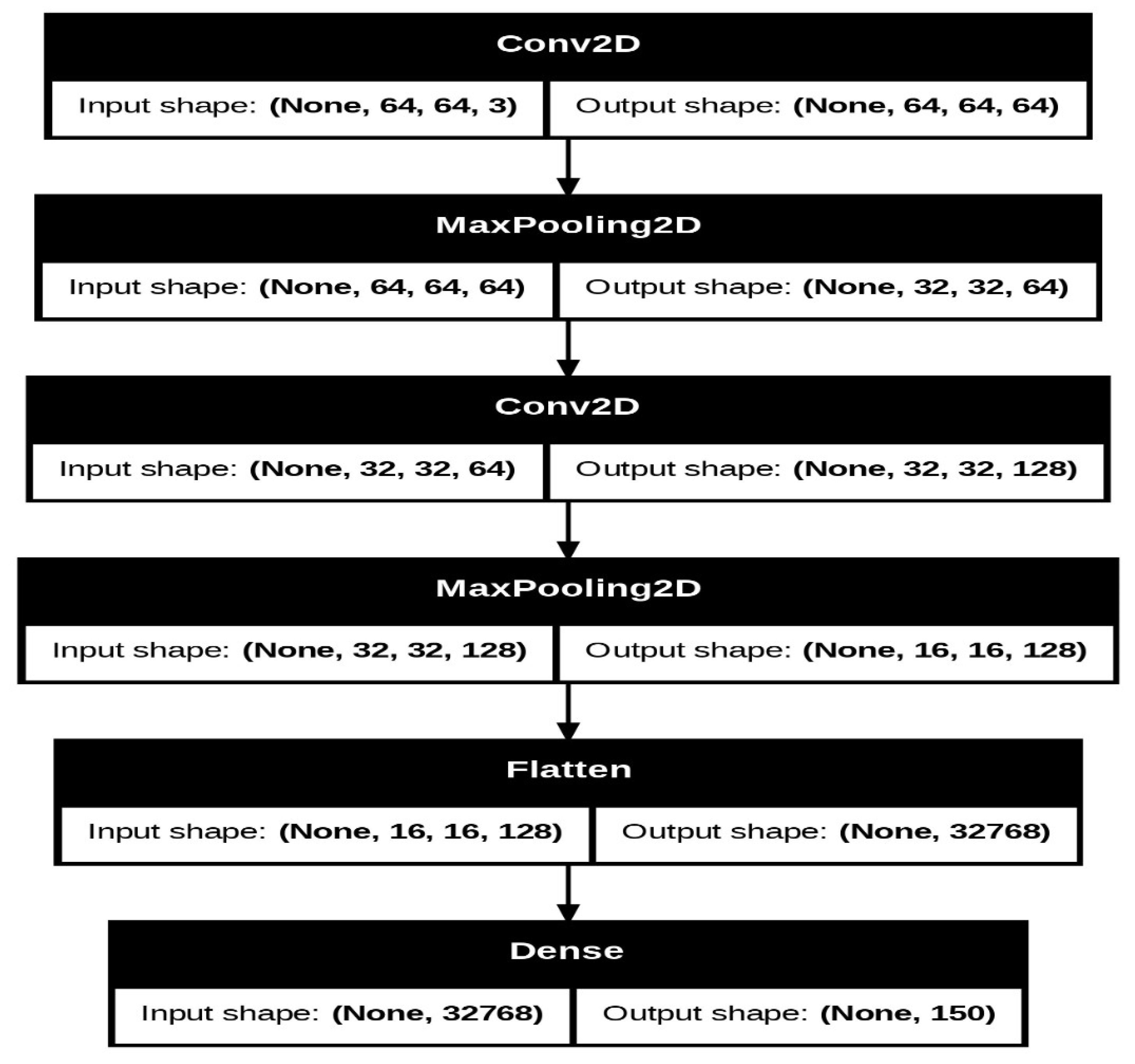

Our CNN model design takes the role of progressively extracting and refining features from input images, from a basic pattern in initial layers to abstract and complex feature detection in later layers. It contains two main convolutional layers with max-pooling to reduce dimensionality, followed by a fully connected output layer for final classification. The model is optimized using the Adam optimizer and categorical cross-entropy loss. It is designed in such a way that it performs multi-class classification with effective learning and good accuracy among the classes. The architecture of the model starts with a Conv2D layer, which takes in 64x64 RGB images, followed by a MaxPooling2D layer that reduces the spatial dimensions. This pattern is once again repeated Conv2D followed by MaxPooling2D to increase the feature extraction along with a decrease in spatial information. Further, these feature maps are flattened into a single-dimensional vector and fed in at the very end to a dense layer.

Layer 1: A Conv2D layer with 64 filters and a kernel size of (5,5) acts as a shallow feature extractor to identify some basic patterns in the input images, such as edges, lines, and shapes. This is followed by a max-pooling layer with a pool size of (2,2) that reduces spatial dimensions and, consequently, computational complexity.

Layer 2: The first layer's output is fed into another Conv2D, which has 128 filters with a kernel size of (3,3); this layer aims to find more complex patterns while another max-pooling layer reduces the dimensionality and retains features.

Output Layer: The output from the convolutional and pooling layers is fed into a fully connected Dense layer with num_classes neurons using the softmax activation function, which gives class probability distributions for effective multi-class classification.

Figure 5.

Our CNN Model Architecture.

Figure 5.

Our CNN Model Architecture.

The image

Figure 6 depicts a visual representation of a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architecture, showing the sequential layers of the model with clear input and output shapes for each stage. The diagram starts with a Conv2D layer, which processes 64x64 RGB images, followed by a MaxPooling2D layer that reduces spatial dimensions. This pattern repeats with another Conv2D and MaxPooling2D pair, further extracting features and compressing the spatial information. The feature maps are then flattened into a single-dimensional vector, which is passed to a dense layer at the end. The flow between layers is illustrated with arrows, and each block prominently displays the input and output shapes, emphasizing the transformation of data across the model.

3.1.1. Layer 1

Layer 1 starts with a Conv2D layer that has 64 filters, each with a kernel size of (5, 5). This initial layer acts as a basic feature extractor, focusing on identifying fundamental patterns in the input images, such as edges, lines, or simple shapes. The relatively large kernel size of (5, 5) allows the network to capture more extensive spatial patterns early on, which can be particularly beneficial if the images contain more intricate or larger structures that need to be recognized. Additionally, the use of padding='same' ensures that the output feature maps retain the same spatial dimensions as the input, thus preserving important boundary information in the images. Following the convolution, there is a max-pooling layer with a pool size of (2, 2), which reduces the spatial dimensions of the feature maps by half. This pooling layer helps reduce the overall computational cost and provides a degree of translation invariance by focusing on the most prominent features.

3.1.2. Layer 2

Layer 2 builds upon the features learned in the first layer by introducing a new Conv2D layer with 128 filters and a smaller kernel size of (3, 3). By increasing the filter count, the network can capture more complex and abstract features, as each subsequent layer in a CNN generally learns more intricate patterns. The smaller kernel size in Layer 2 narrows the focus of the feature extraction process, helping the network detect finer details within the image. Like Layer 1, this layer also uses padding='same' to maintain spatial dimensions, ensuring that no valuable information is lost along the edges. Another max-pooling layer with the same pool size of (2, 2) follows, further reducing the spatial size of the feature maps while retaining the most crucial information. Finally, a Flatten () layer converts the 3D output of the second pooling layer into a 1D array, preparing the data for the fully connected layer.

3.1.3. Output Layer

The output layer is a fully connected Dense layer with num_classes neurons, where each neuron represents a possible class in the classification task. The softmax activation function is applied here to provide a probability distribution over the classes, allowing the model to output a confidence level for each class. This setup is suitable for multi-class classification tasks, as softmax is specifically designed to handle such scenarios. The model is compiled with the Adam optimizer, a widely used optimizer that adapts the learning rate during training, making it efficient for deep learning tasks. The categorical cross-entropy loss function is ideal for multiclass classification, as it measures the divergence between the predicted and actual distributions. Overall, the CNN model architecture is crafted to effectively balance feature extraction with computational efficiency, progressing from basic pattern detection to sophisticated classification. Each layer plays a distinct role in capturing essential image details and refining the model’s ability to differentiate between classes. This design supports reliable image recognition, meeting the needs of multi-class classification while accommodating the dataset's complexity.

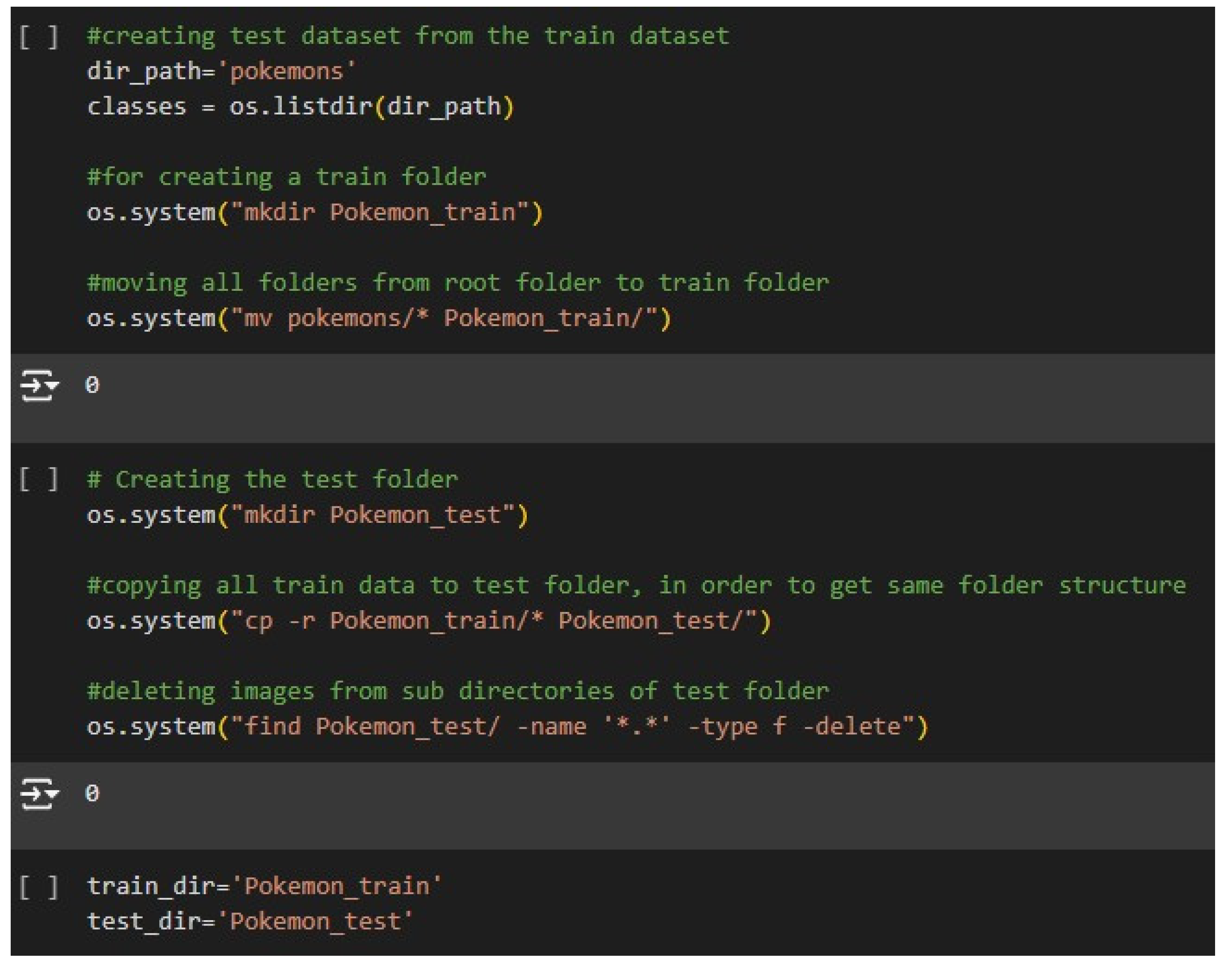

3.2. Implementation

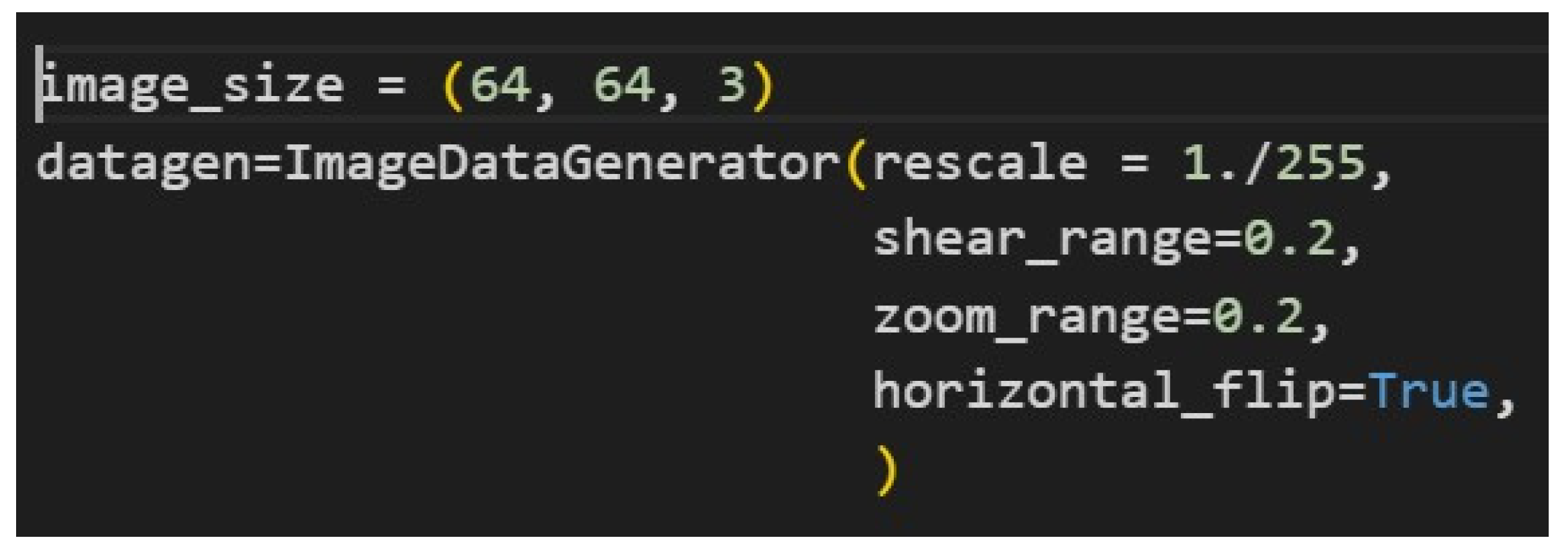

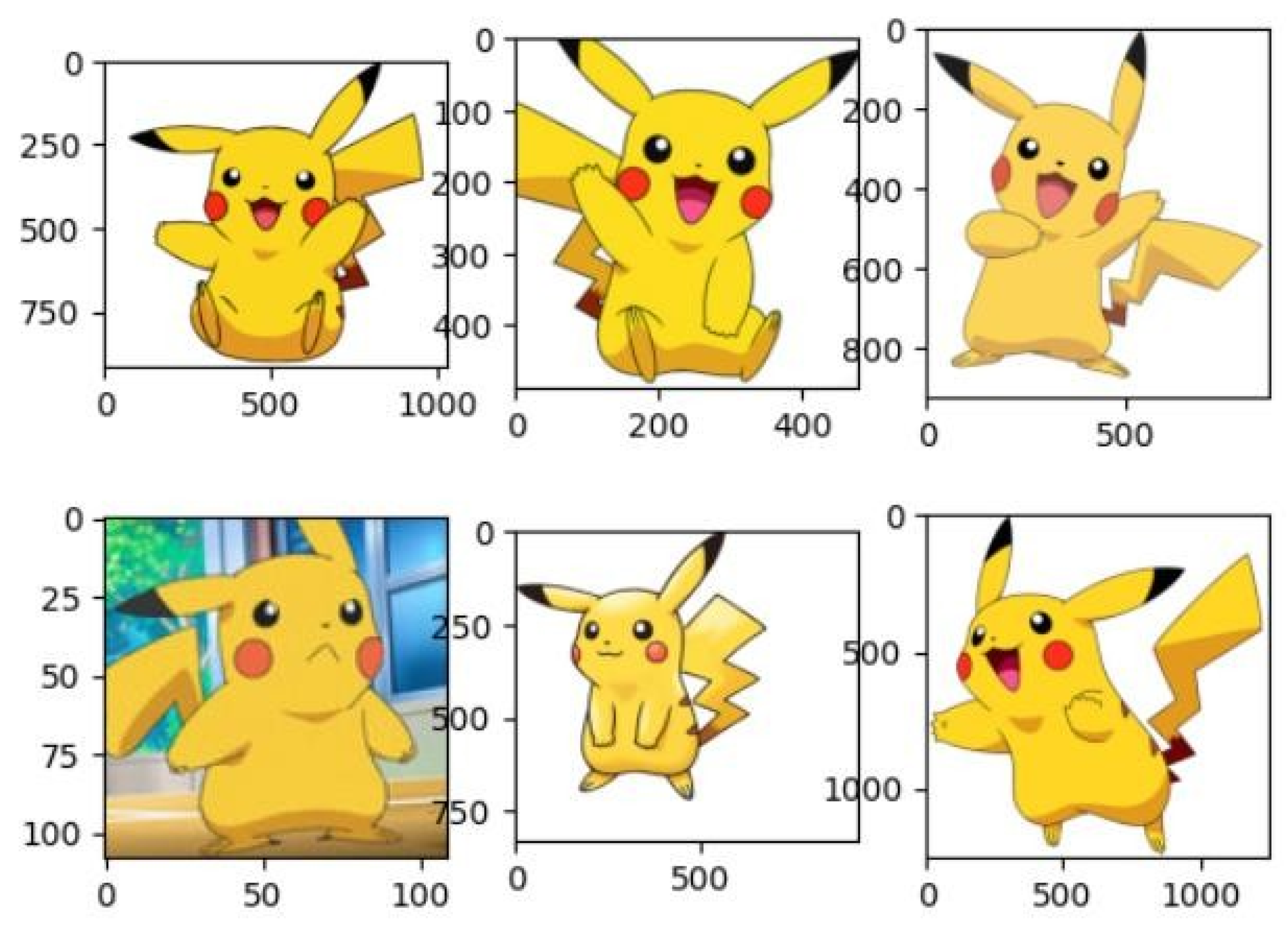

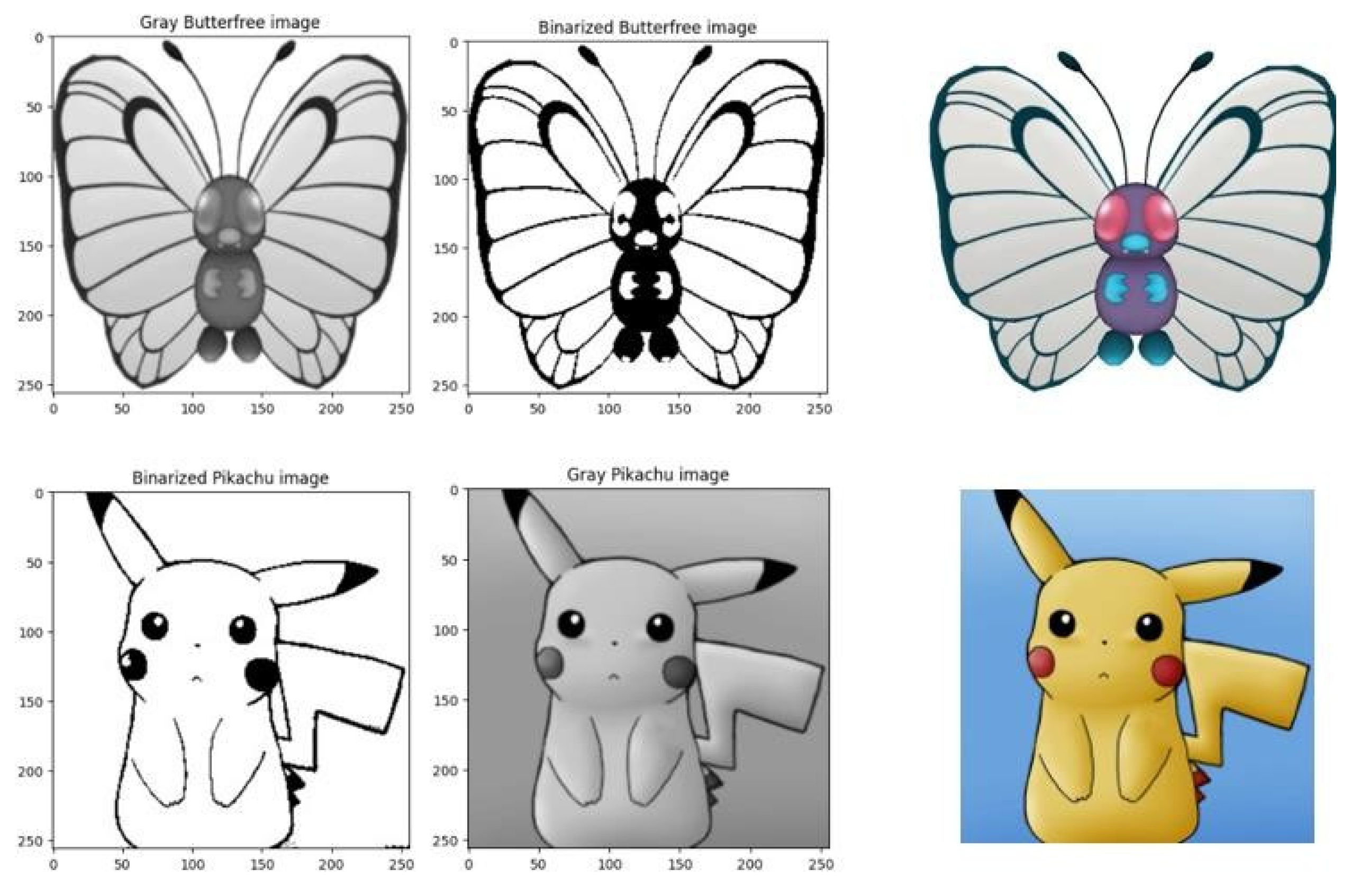

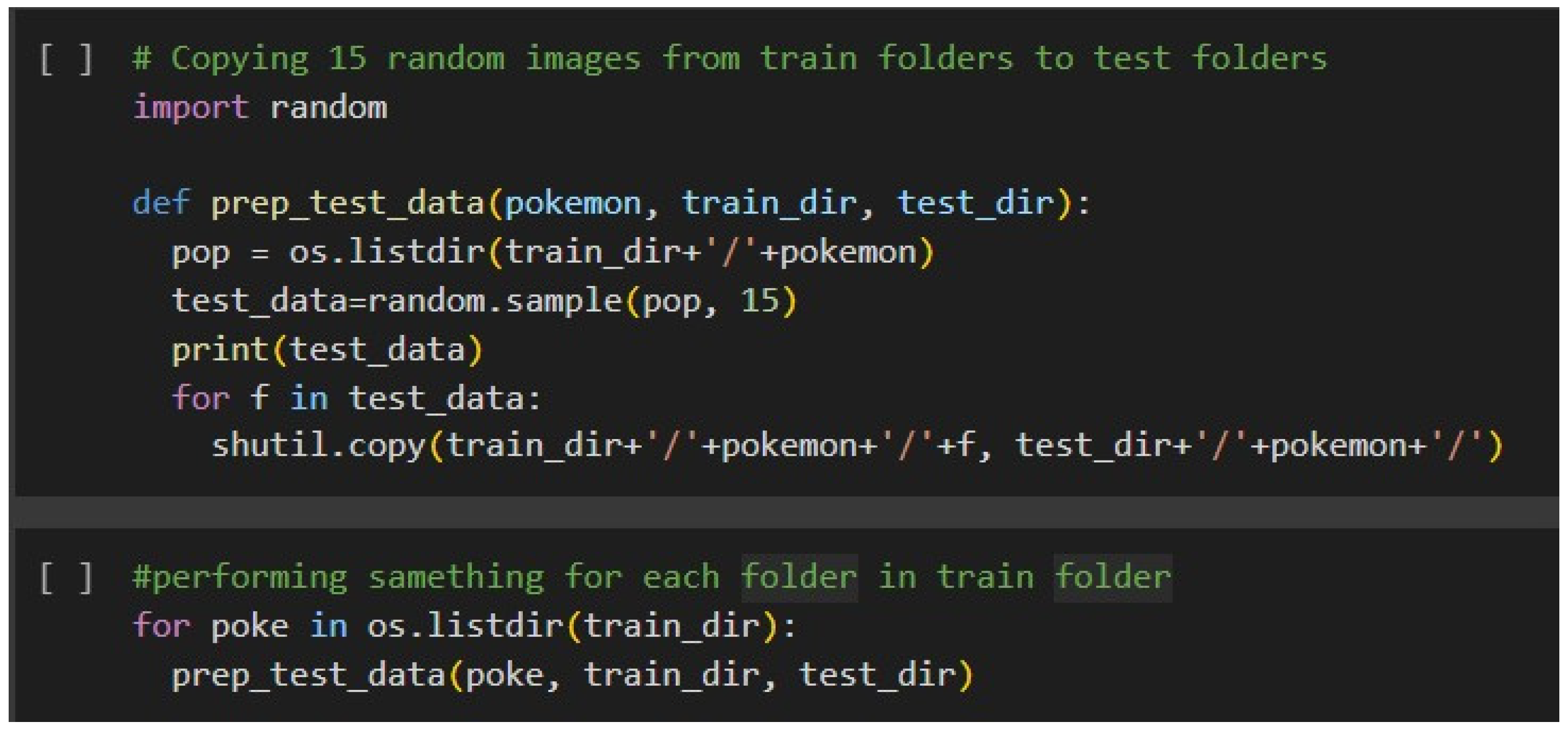

This is now the implementation stage, structuring, preprocessing, and training of the dataset. First, there's the division of the dataset into a training set and a test set where the training images are put in the 'Pokemon_Train' directory, and classes are represented as structured sets of empty folders in the 'Pokemon_Test' directory. The function was modified to randomly select 15 images per class from the training dataset and copy them into the test directory to create this test dataset so that the test set is unbiased. Data augmentation and preprocessing are two of the most crucial steps in any model's performance. The images here are resized, and pixel values are normalized, along with different augmentations such as random shearing, zooming, and flipping, using Keras' Image Data Generator. These transformations result in the introduction of variance in the dataset, thereby increasing the generalization capability of the model to avoid overfitting.

Figure 7 describes creating and preparing a dataset to perform Pokémon classification, structuring data organization. It first defines the working directory, 'Pokemon', which would house all classes in a total number of 150 classes. Furthermore, create a new directory named 'Pokemon_Train' and move all class folders from the main 'Pokemon' directory into 'Pokemon_Train', so that 'Pokemon_Train' will be a home for training data. Then, a 'Pokemon_Test' folder is created with a copy of all subdirectories inside 'Pokemon_Train'. That way, both folders will have exactly the same hierarchical structure, a thing that is very important for most of the libraries relying on directory organization as a basis for classifying images. Finally, all images are removed inside the 'Pokemon_Test' folder, leaving only empty folders, therefore creating a test structure with labels but no data. Both directories are assigned to variables matching their names in the last step.

Code given makes a function selecting 15 random images in every Pokémon class inside the Train directory and transfers to the right folder in each test class folder, thus arranging everything for Train-Test divisions. It's this way sure the test data contains a portion of images in the same distribution than the dataset; this represents, in actual case, more precise testing the skill of your model. The code constructs a separate test dataset with the balanced classes inside the train-test sets by looping over each class folder in the training set and performing this function. This random choice helps to avoid biased results because of a fixed test set and keeps the model from getting over-fitted by seeing a wide range of test data. The generalizing capability of the model, along with its robustness, improves in this process.

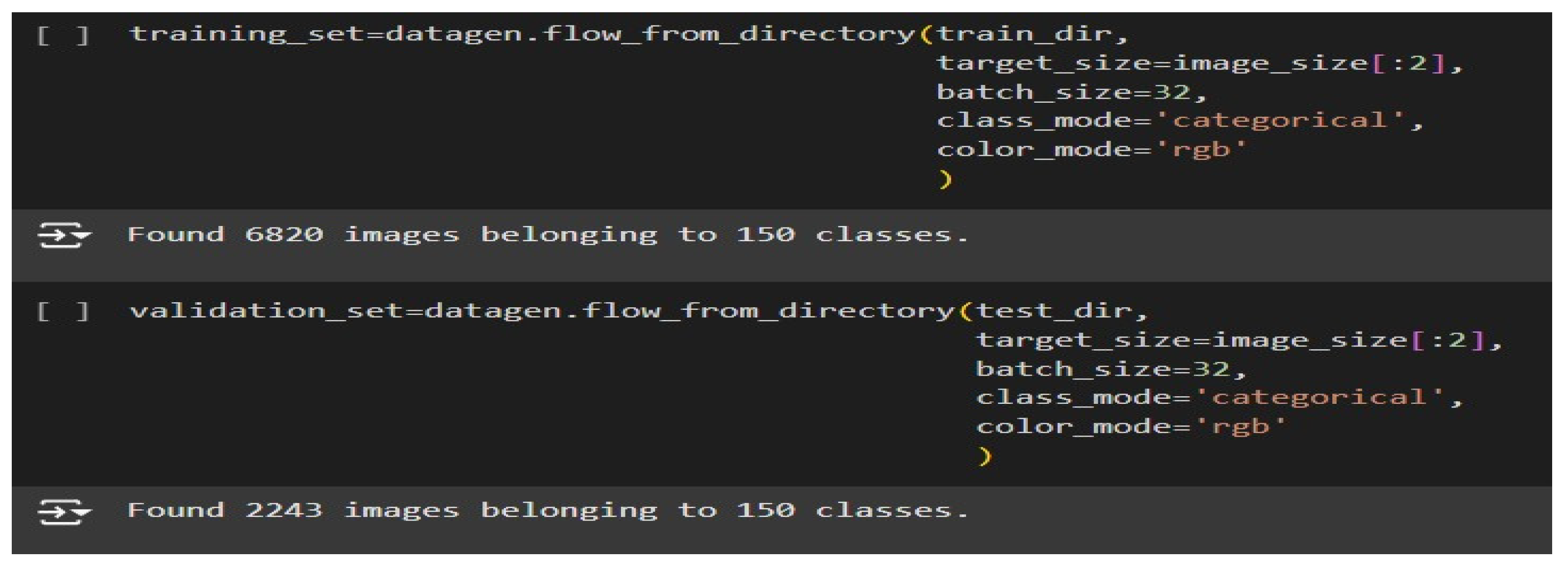

Figure 9 shows how the ImageDataGenerator class from Keras is used to load, preprocess, and batch images from specified directories and prepare them for training and validation. The first snippet defines a training set generator by calling the function datagen.flow_from_directory(train_dir). The generator targets the train_dir, which should contain subdirectories named according to the categories in the training dataset. Each subdirectory is supposed to hold pictures for one class in general. For example, "cats" or "dogs" in a classifier able to recognize animal types. A configuration like this will ensure that the model will learn from labelled data [

19,

20,

21].

In this target_size= image_size[:2], it's indicated that all images will be resized to 'uniform width and height' from the image_size variable. This just slices out the first two dimensions, disregarding any channel information so that these could be made uniform across the dataset for the input layer of the CNN. The batch_size = 32 parameter sets the number of images to process in a single batch-a trade-off between computational efficiency and memory consumption because batches are processed sequentially during training [

16,

17,

18]. Finally, class_mode = 'categorical' states that the labels are categorical and automatically one-hot-encodes them, which is useful if using categorical cross-entropy as a loss function. Lastly, color_mode = 'rgb' ensures that images are loaded in full color-three channels for red, and green, and blue-which is important for models that rely on color information for classification. The second snippet is to create a validation_set generator, which, similarly in structure, points to test_dir instead of train_dir. In this folder are the validation images, arranged like in the training directory, with class-named subfolders. The images for validation determine how well the model generalizes on unseen data; thus, enabling the detection of overfitting that may occur. This class takes target_size, batch_size, class_mode, and color_mode identical to the ones used in the creation of training_set, ensuring that both datasets are uniformly processed.

These steps were essential to be done before the execution of the model. However, since the model execution process is already explained in the Architecture Overview, the discussion hereafter will be done on the steps performed post running the model [

22,

23,

24,

25].

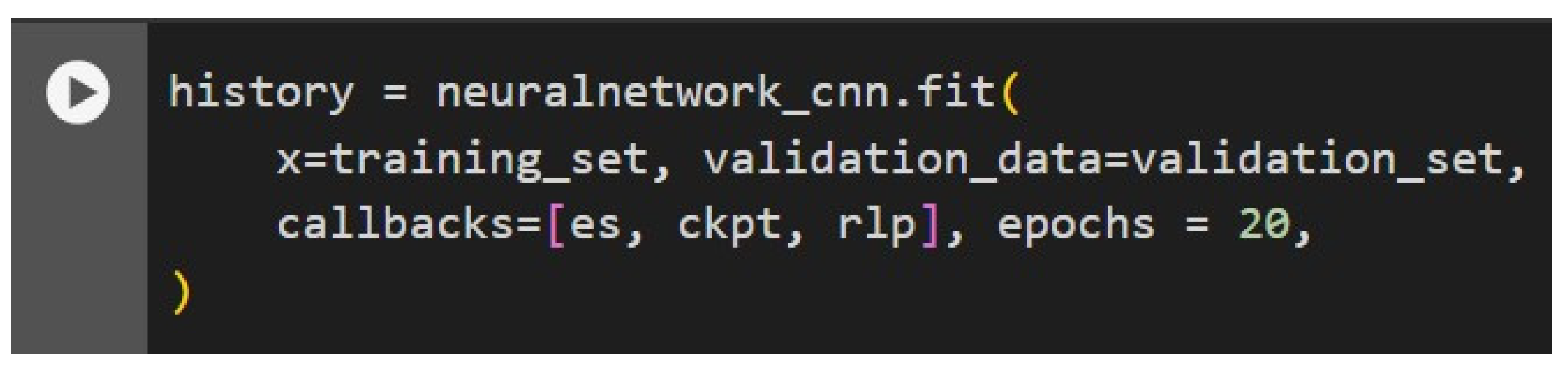

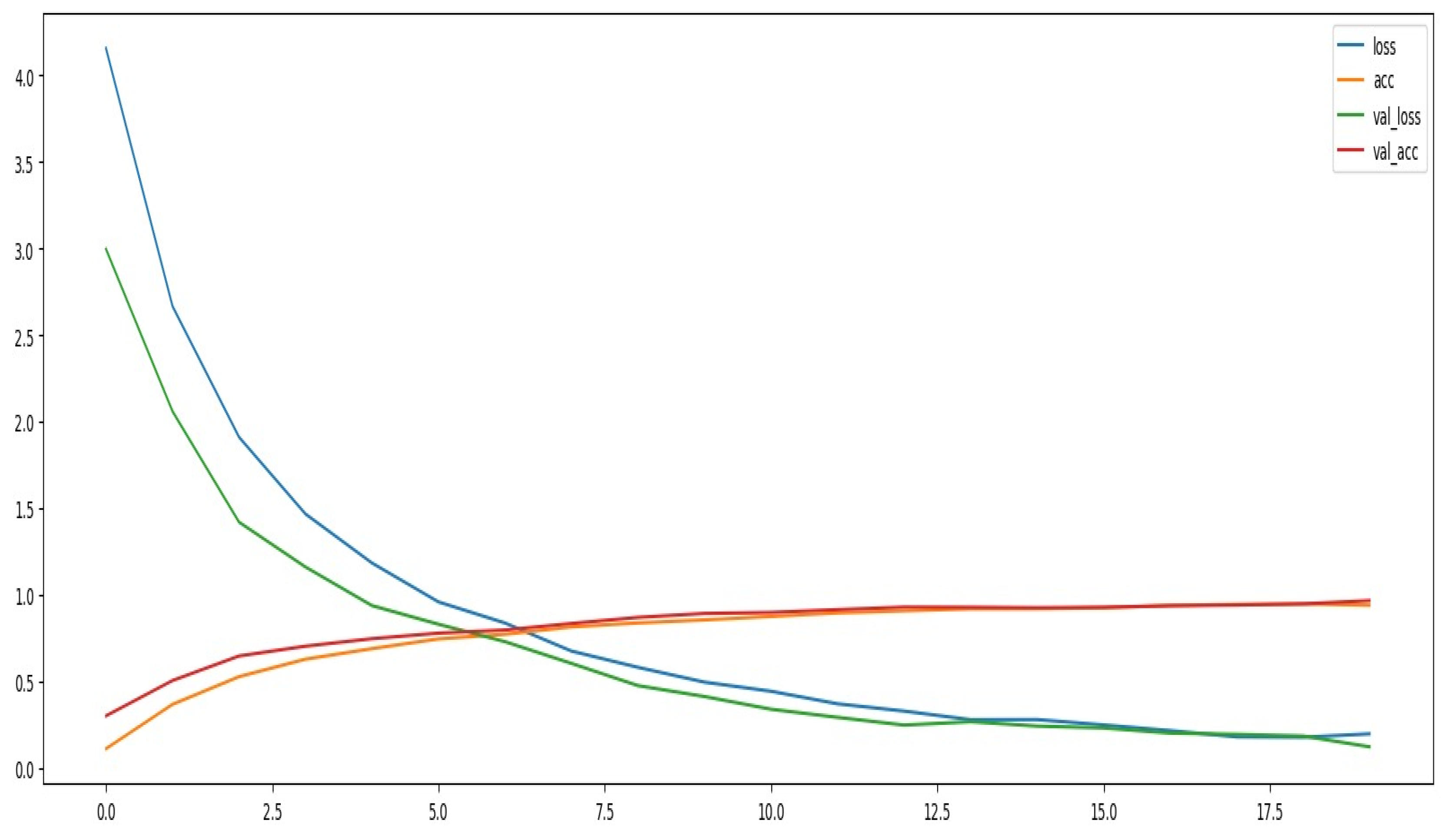

Figure 10 shows the code for the training process of the constructed model, which is trained through the fit method. It took in the training set as input and the validation set as validation data to monitor model performance. To optimize, manage, and control the training process, several callback functions were created: 'es' for early stopping, 'ckpt' for saving model checkpoints, and 'rlp' for reducing the learning rate in case of no further improvement. These callbacks will enhance training efficiency and help avoid overfitting by stopping the training when it stops improving, while it saves the best model and dynamically adjusts the learning rate. The model is trained up to a limit of 20 epochs, but if the early stop criteria are fulfilled, training could stop earlier. The limit has been set as 20 to strike a fine balance in terms of training time, ensuring effectiveness in learning from the model but not overfitting. Details concerning metrics both on training and validation across all epochs are captured in the history object returned by the fit method, which can be used later for performance analysis and visualization.

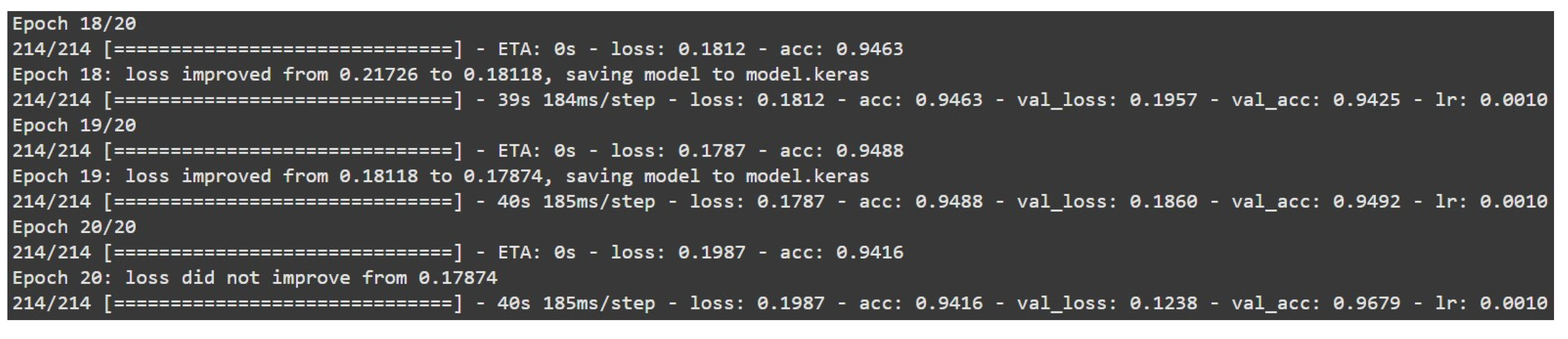

Figure 11 presents the result of running 20 epochs. It would be too time-consuming to paste the output of all 20 runs here, so only the results of the last few runs are shown. From these, one can see that the model is still improving in accuracy. As was mentioned before, 20 runs should give a good balance: The model learned from most of the dataset and will not overfit.