1. PCMV/PRV—molecular biology

Porcine cytomegalovirus/porcine roseolovirus is a porcine herpesvirus in the genus

Roseolovirus, not in the genus

Cytomegalovirus [

1,

2]. The name given by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ITCV) is suid betaherpesvirus 2 (SuBHV2), indicating that it belongs to the subfamily Betaherpesvirinae [

3]. The misleading originally chosen name PCMV can be explained by reports on the appearance of cytomegalic cells with characteristic basophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies in the mucosal glands of turbinates of pigs [

4]. Sequence comparisons made it clear that PCMV/PRV is a roseolovirus closely related to the human roseoloviruses herpes virus-6 (HHV-6) and HHV-7. Whereas HHV-6 and HHV-7 are widespread in the human population, PCMV/PRV is also highly prevalent in pigs. For instance, a study on German slaughterhouse pigs found that all animals were infected [

5].

The virus has a linear double-stranded DNA genome 12837 bp long and containing 79 open reading frames (ORFs) [

2]. Of these ORFs, 69 have counterparts in HHV-6A, HHV-6B, and HHV-7. The genome is a Direct repeat (DR)—unique (U)—DR type, similar to HHV-6A, HHV-6B, and HHV-7, but the PCMV/PRV DR is shorter and lacks predicted genes and telomeric repeats (TMRs). The absence of these TMR sequences means that PCMV/PRV unlike the closely related HHV6 cannot integrate into the host cell genome [

2]. As a result, PCMV/PRV like most other herpesviruses has to maintain its genome as circular episome during the quiescent stage of infection.

It is still unclear whether PCMV/PRV can infect cells from non-human primates and humans. Herpesviruses were once believed to be strictly species-specific, incapable of infecting other species. However, this understanding has evolved, with evidence now confirming transspecies transmission of several herpesviruses (for review see [

6]). One example is baboon cytomegalovirus (BaCMV), which was shown to infect human cells in vitro and which was found in human recipients of baboon liver [

7,

8]. Furthermore, human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) was shown to infect pig cells [

9]. Regarding PCMV/PRV and human cells, one study has reported infection in human cells [

10], whereas two others have found no evidence of infection [

11], Morozov, Denner, unpublished results.

2. Pathogenesis in the pig

The primary route of infection is transmission from an infected mother sow, occurring after the maternal antiviral antibody levels decline in the piglet [

12]. Unlike in many other mammals, these antibodies are not transferred via the placenta in pigs but are instead provided through colostrum. If the mother is infected, the piglet typically experiences only mild clinical symptoms and recovers quickly. However, if the piglet is born to a PCMV-negative mother and lacks partial protection by maternal antibodies, a more severe respiratory disease may develop, potentially leading to fatal outcomes. PCMV/PRV is occasionally associated with inclusion body rhinitis and pneumonia in piglets, reproductive disorders in pregnant sows and respiratory disease complex in older pigs [

12]. The virus is shed in nasal secretions and it has also been detected in ocular secretion, urine, cervical fluid and semen [

13]. PCMV-infected sows are prone to abortion, with pathological changes including edema in the heart, lungs, and lymph nodes [

14]. In production facilities, infections are generally asymptomatic due to the development of herd immunity. However, Chinese scientists mention that PCMV/PRV has caused huge economic losses to the porcine breeding industry [

13].

PCMV/PRV is an immunosuppressive virus that mainly inhibits the immune function of the macrophage and T-cell lymphatic systems [

15]. Infections in pigs are often associated with opportunistic bacterial infections based on the immunosuppression by the virus. Transcriptome analysis of PCMV/PRV-infected pig thymuses showed that 2,161 genes were upregulated and 3,421 were downregulated compared with the uninfected group [

15]. Among others, interleukin 1 α (IL-1α), IL-1β, and IFN-α, were elevated in expression, whereas IL-12B, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) were found consistently downregulated as shown by qPCR, Western blot, and microarray analysis. IL-7, Il-8 and IL-15 were found up-regulated as shown by PCR and microarray. The expression levels of most genes involved in the T cell receptor (TCR) signaling pathway were downregulated. TGF-β is an immunosuppressive cytokine, and the activated TGF-β signaling pathway may function in PCMV/PRV infection as it does during infections by other immunosuppressive viruses, e.g., HCMV [

16]. When microRNA (miRNA) expression profiles of PCMV/PRV-infected porcine macrophages via high-throughput sequencing were analyzed, 239 miRNA database-annotated and 355 novel pig-encoded miRNAs were detected. Of these, 130 miRNAs showed significant differential expression between the PCMV-infected and uninfected porcine macrophages [

17]. When porcine small-RNA transcriptomes of PCMV-infected and uninfected organs were characterized by high-throughput sequencing, 92, 107, 95, 77 and 111 miRNAs were significantly differentially expressed in lung, liver, spleen, kidney and thymus after PCMV infection, respectively [

18].

PCMV/PRV is able to infect and propagate in pig monocyte derived macrophages (MDMs) in vitro. Infection decreased expression of IL-8 and TNF-α and increased expression of IL-10 on mRNA transcription level [

19].

Additionally, when primary porcine aortic endothelial cells (PAEC) were infected with PCMV/PRV in vitro, an increase in porcine tissue factor (TF) was observed, indicating virus-induced endothelial cell activation [

20]. TF is also called coagulation factor III, it is present in subendothelial tissue and leukocytes and plays a major role in coagulation initiating of thrombin formation from the prothrombin.

3. Pathogenesis in non-human primate xenotransplant recipients

PCMV/PRV was transmitted in numerous preclinical xenotransplantation trials involving non-human primates. In the first reported case, pig thymokidneys were transplanted into baboons, leading not only to the transmission and replication of PCMV/PRV but also to the activation of BaCMV [

21]. The intensive pharmaceutical immunosuppression required for xenotransplantation, combined with the absence of the pig's immune system to control viral replication, facilitated rapid PCMV/PRV replication in the transplanted organ.

In eight preclinical trials involving the transplantation of pig thymokidneys, hearts, kidneys, and livers into baboons and cynomolgus monkeys, the transmission of PCMV/PRV to baboons or cynomolgus monkeys, led to consumptive coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia, which were linked to a significantly reduction in survival time (for review, see [

6]).

A significant reduction of the survival time of orthotopically transplanted hearts from genetically modified pigs in baboons was also observed, when PCMV/PRV-positive hearts were used. Animals with a PCMV/PRV-positive heart did not survive beyond 30 days, whereas those with virus-negative pig hearts achieved survival times of up to 195 days [

22,

23]. In one case, PCMV/PRV was transmitted to the recipient despite the virus was not detected in the donor pig [

24]. In this case, PCMV/PRV was not detected in the donor pig's blood by PCR due to viral latency, yet it triggered virus-specific clinical symptoms in the recipient.

In baboons transplanted with PCMV/PRV-positive hearts, a high viral load was detected in the explanted pig heart which was higher compared with the virus load in donor pig organs [

23]. But virus was also found in all examined baboon organs. This was shown using PCR and immunohistochemistry using specific antiviral antibodies [

25]. The virus-protein-positive cells were likely disseminated pig cells.

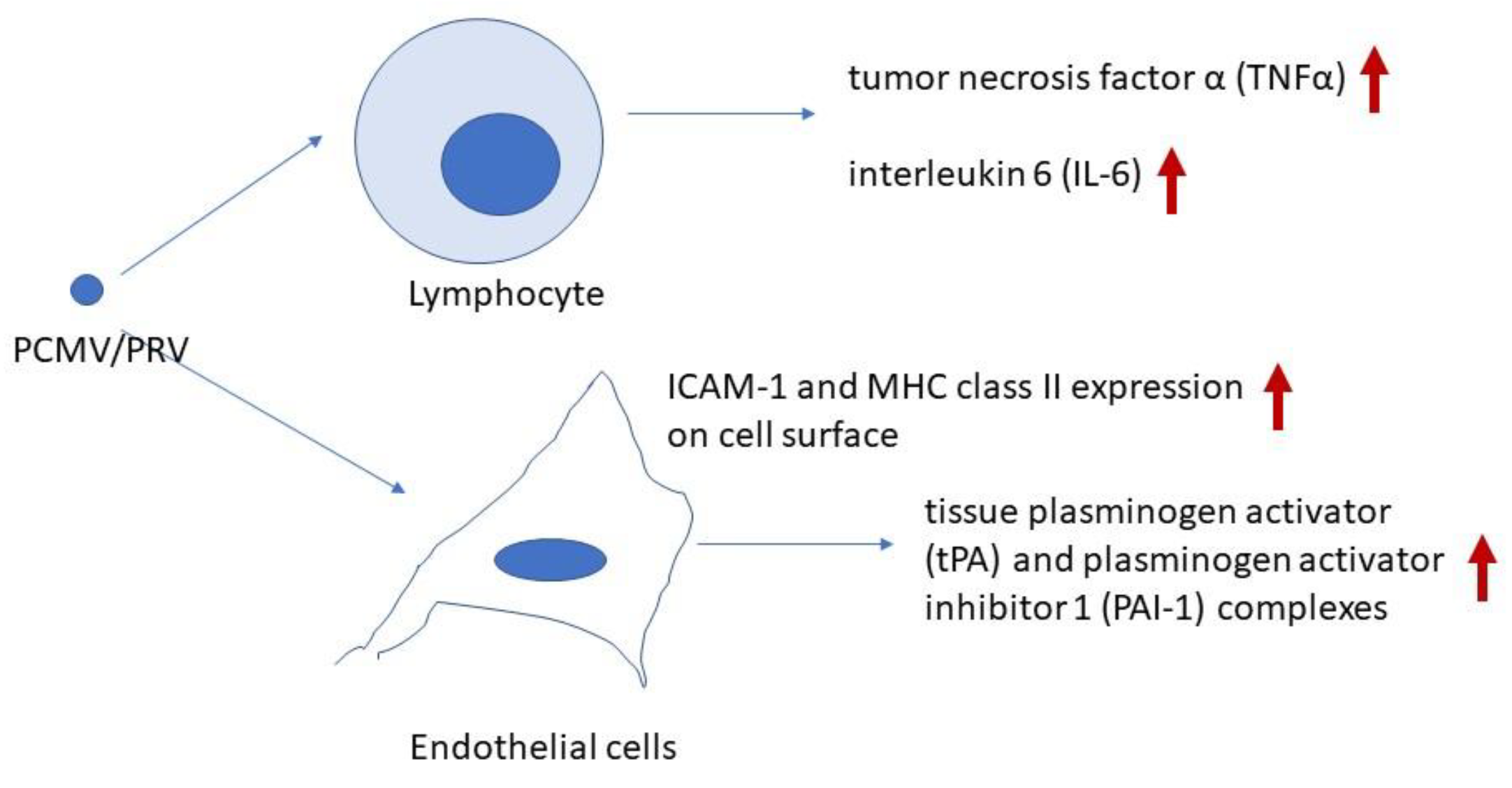

Analyzing the cytokine levels in the blood or baboon recipients, an increase of IL-6 and TNF in the baboons with PCMV/PRV-positive hearts was observed [

23]. No alterations were observed in serum levels of interferon γ (IFNγ), IL-2, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-10.

4. Transmission to a human pig heart recipient

PCMV/PRV was transmitted to the first patient who received a genetically modified pig heart and contributed to the death of the patient [

26,

27]. The cardiac xenotransplant from a ten-gene modified pig sustained life despite the recipient’s pre-existing conditions and multiple surgical and non-surgical complications until the patient died from graft failure on postoperative day 60. Clinical symptoms similar to the ones observed in the baboon with the PCMV/PRV-positive pig hearts were observed: At postoperative day 50, the endomyocardial biopsy revealed damaged capillaries with interstitial oedema, red cell extravasation, rare thrombotic microangiopathy, and complement deposition [

33]. Endothelial changes ranged from prominent nuclei to cell swelling with areas of complete vascular dissolution [

26]. The patient's viral load continued to rise despite antiviral treatment. However, these antivirals are very effective against HCMV but not against the roseolovirus PCMV/PRV [

28]. Additionally, the reactivation of latent PCMV/PRV in the xenotransplant may have triggered a harmful inflammatory response in the patient, comparable with increased release of IL-6 in the baboons [

23]. In addition, high levels of tPA-PAI-1 complexes were found in the animals with PCMV/PRV-positive pig hearts, indicating a decrease in fibrinolyis [

23].

5. Molecular insights into PCMV/PRV-induced xenozoonosis

Currently, two primary effects of PCMV/PRV on xenotransplant recipients can be proposed: first, an impact on the coagulation system, and second, an effect on the immune system (

Figure 1).

The mechanism by which PCMV/PRV induces endothelial cell activation, leading to the early and severe loss of xenotransplants, remains partially unclear. In one study, transmission of PCMV/PRV was associated with increased expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II in the transplant, indicating endothelial cell activation [

29].

For comparison, an in vitro study demonstrated that human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) infected with HCMV exhibited a significant increase in ICAM-1 surface expression [

30]. An association between HCMV infections and the occurrence of rejection after renal allotransplantation is well known. HCMV-infected human proximal tubular epithelial cells (PTEC) also displayed increased levels of ICAM-1 and this was a direct effect requiring infectious virus [

31].

Although PCMV/PRV is classified as a roseolovirus rather than a cytomegalovirus like HCMV, a similar upregulation of ICAM-1 and MHC class II antigens was observed on the endothelial surface of PCMV/PRV-positive pig kidney xenotransplants, but not in PCMV/PRV-negative kidneys [

29]. The increased ICAM-1 expression on endothelial cells in infected xenotransplants facilitated the adhesion of activated lymphocytes and platelets. This profound endothelial activation, particularly in tubular capillaries, may contribute to interstitial hemorrhage and subsequent transplant failure [

29]. Additionally, when primary porcine aortic endothelial cells (PAEC) were infected with PCMV/PRV in vitro, an increase in porcine tissue factor (TF) was observed, indicating virus-induced endothelial cell activation [

20].

Since there is no evidence that PCMV/PRV can infect non-human primate and human cells (see above), it has to be proposed a virus protein should be interacting with the target cells in the recipient.

It is not uncommon for viral proteins to interact independently of viral infection on target cells. This applies to both regulatory and structural proteins. For example, the human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) regulatory protein Tat (trans-activating factor) exhibits multifunctional activity, acting both endogenously within infected cells and exogenously on uninfected ones. Tat serves as the primary transcriptional regulator of HIV by binding to mRNA. Additionally, extracellular Tat interacts with various cellular membrane receptors and can penetrate host cells through endocytic pathways [

32]. Extracellular Tat, secreted by nearby infected macrophages, can bind to the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) on the surface of neurons, facilitating its entry via endocytosis. This interaction has been shown to induce neuronal death [

33].

Retroviral transmembrane envelope proteins illustrate how structural proteins can interact with uninfected cells and trigger immunosuppression (for review, see [

34]). By binding to unidentified receptors on immune cells, retroviruses, their transmembrane envelope proteins, and synthetic peptides corresponding to a highly conserved domain among all retroviruses, the so called immunosuppressive domain, stimulate the release of several cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-10, IL-6, IL-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 and MCP-2, tumor necrosis factor - α (TNF-α), and macrophage inflammatory proteins (MIP)-1α and MIP-3. Conversely, they suppress the expression of IL-2 and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 (CXCL-9, also known as monokine induced by gamma interferon, MIG) [

35].

Furthermore, mouse tumor cells, while incapable of inducing tumors in immunocompetent mice, can successfully form tumors when the transmembrane envelope proteins from various retroviruses are expressed on their surface [

36].

The genes and proteins of PCMV/PRV are not well studied. In the unique region, 79 genes were predicted and the majority of these genes have homologs in HHV-6A, HHV-6B, and HHV-7 in amino acid composition and sequence [

2]. Furthermore, two pp65 proteins of PCMV have been identified that might have similar function as the pp71 (UL82) and pp65 (UL83) of HCMV that can interact with different cellular proteins that regulate IE gene expression and host immune response.

Finally, it is worth emphasizing the following point: Zoonoses are defined as infectious diseases caused by a microorganism from a non-human vertebrate. Since PCMV/PRV does not harm healthy human individuals and since PCMV/PRV does not infect human cells, the disease caused by PCMV/PRV should be defined as xenozoonosis [

37].

5. PCMV/PRV and HHV-6

HHV-6 and HHV-7 are the closest relatives of PCMV. When we screened butchers and blood donors for antibodies against PCMV/PRV, using a Western blot assay and a recombinant part of the gB protein of PCMV/PTV as antigen, antibodies against this protein were found in several individuals [

38]. A detailed analysis showed that these antibodies are antibodies directed against HHV6, i.e., human sera infected with HHV-6 recognized a recombinant PCMV/PRV protein. Vice versa, pig sera reacting against PCMV also reacted with human cells infected with HHV-6. We also analyzed a human IgG preparation (Cytotect), produced for the prophylaxis of HCMV-infections for patients under immunosuppressive therapy, especially transplant recipients. These humane IgG preparations also reacted against the PCMV/PRV protein in our Western blot assay. Although derived from HCMV-positive donors, the reactivity with the PCMV protein can certainly be explained by the presence of antibodies against HHV-6 in the preparation. The prevalence of HHV-6 infection in the human population is very high.

Another situation suggesting a potential connection between anti-HHV-6 and anti-PCMV/PRV antibodies arises from the case of the first patient to receive a pig heart transplant. Interestingly, this patient was treated with cidofovir and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) [

26]. IVIG was administered due to severe hypogammaglobulinemia and its well-documented benefits in allotransplantation. However, it remains uncertain whether the temporary decrease in the otherwise steadily increasing PCMV/PRV load resulted from antiviral treatment or the presence of HHV-6 antibodies within the IVIG preparation [

28]. IVIG, derived from pooled plasma from 1,000 to 100,000 donors, is widely used as replacement therapy for primary and acquired humoral immunodeficiencies, as well as for immunomodulation in autoimmune diseases and transplantation [

39].

6. Conclusion

PCMV/PRV is a xenozoonotic virus that significantly shortens the survival of pig xenotransplants in non-human primates. It was also transmitted to the first human recipient of a pig heart, contributing to the patient's death. Although no evidence suggests that the virus infects human or other primate cells, it appears to interact directly with immune and endothelial cells, disrupting cytokine signaling and coagulation pathways. Further research is needed to uncover the molecular mechanisms underlying this xenozoonotic disease. Identifying the viral protein(s) responsible for the interactions between virus and xenotransplant recipient would be highly valuable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, J.D.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of Free University Berlin.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BaCMV |

baboon cytomegalovirus |

| CXCL-9 |

chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 |

| HCMV |

human cytomegalovirus |

| HHV6, 7 |

human herpesvirus 6, 7 |

| HUVEC |

human umbilical vein endothelial cells |

| ICAM-1 |

intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| IFNγ |

interferon γ |

| IL-1α, -1β, -4, -5, -6, -7, -8, -12B, -15 |

interleukin-1α, -1β, -6, -7, - 8, -12B, 15 |

| ITCV |

International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses |

| IVIG |

intravenous immunoglobulin |

| MCP-1, -2 |

monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, -2 |

| MDMs |

monocyte derived macrophages |

| MIP-1α, -3 |

macrophage inflammatory protein-1α, -3 |

| MHC |

major histocompatibility complex |

| miRNA |

micro RNA |

| MIG |

monokine induced by gamma interferon |

| PAEC |

porcine aortic endothelial cells |

| PAI-1 |

plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 |

| PCMV/PRV |

porcine cytomegalovirus/porcine roseolovirus |

| PTEC |

proximal tubular epithelial cells |

| SuBHV2 |

suid betaherpesvirus 2 |

| TCR |

T cell receptor |

| TGF-β1 |

transforming growth factor β1 |

| TF |

porcine tissue factor |

| TNFα |

tumor necrosis factor α |

| tPA |

tissue plasminogen activator |

References

- Denner, J.; Bigley, T.M.; Phan, T.L.; Zimmermann, C.; Zhou, X.; Kaufer, B.B. Comparative Analysis of Roseoloviruses in Humans, Pigs, Mice, and Other Species. Viruses. 2019, 11, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, W.; Zeng, N.; Zhou, L.; Ge, X.; Guo, X.; Yang, H. Genomic organization and molecular characterization of porcine cytomegalovirus. Virology. 2014, 460-461, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://ictv.global/report/chapter/orthoherpesviridae/orthoherpesviridae/roseolovirus (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Edington, N.; Plowright, W.; Watt, R.G. Generalized porcine cytomegalic inclusion disease: Distribution of cytomegalic cells and virus. J Comp Pathol. 1976, 86, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhelum, H.; Kaufer, B.; Denner, J. Application of Methods Detecting Xenotransplantation-Relevant Viruses for Screening German Slaughterhouse Pigs. Viruses. 2024, 16, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J. Reduction of the survival time of pig xenotransplants by porcine cytomegalovirus. Virol J. 2018, 15, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, M.G.; Alcendor, D.J.; St George, K.; Rinaldo, C.R., Jr.; Ehrlich, G.D.; Becich, M.J.; Hayward, G.S. Distinguishing baboon cytomegalovirus from human cytomegalovirus: Importance for xenotransplantation. J Infect Dis. 1997, 176, 1476–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, M.G.; Jenkins, F.J.; St George, K.; Nalesnik, M.A.; Starzl, T.E.; Rinaldo, C.R., Jr. Detection of infectious baboon cytomegalovirus after baboon-to-human liver xenotransplantation. J Virol. 2001, 75, 2825–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degré, M.; Ranneberg-Nilsen, T.; Beck, S.; Rollag, H.; Fiane, A.E. Human cytomegalovirus productively infects porcine endothelial cells in vitro. Transplantation. 2001, 72, 1334–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitteker, J.L.; Dudani, A.K.; Tackaberry, E.S. Human fibroblasts are permissive for porcine cytomegalovirus in vitro. Transplantation. 2008, 86, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, A.W.; Galbraith, D.; McEwan, P.; Onions, D. Evaluation of porcine cytomegalovirus as a potential zoonotic agent in xenotransplantation. Transplant Proc. 1999, 31, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plowright, W.; Edington, N.; Watt, R.G. The behaviour of porcine cytomegalovirus in commercial pig herds. J Hyg (Lond). 1976, 76, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Liao, S.; Zhu, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, Y. Molecular epidemiology of porcine Cytomegalovirus (PCMV) in Sichuan Province, China: 2010-2012. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8, e64648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edington, N.; Wrathall, A.; Done, J. Porcine cytomegalovirus (PCMV) in early gestation. Vet microbiol 1988, 17, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, L.; Liao, S.; Guo, W. Transcriptome analysis of porcine thymus following porcine cytomegalovirus infection. PLoS ONE. 2014, 9, e113921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, L.; Ma, J.; et al. The role of the CD95, CD38 and TGF-b 1 during active human cytomegalovirus infection in liver transplantation. Cytokine 2006, 35, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liao, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, L.; Yang, F.; Guo, W. Identification and Analysis of the Porcine MicroRNA in Porcine Cytomegalovirus-Infected Macrophages Using Deep Sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2016, 11, e0150971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wei, H.; Liao, S.; Ye, J.; Zhu, L.; Xu, Z. MicroRNA transcriptome analysis of porcine vital organ responses to immunosuppressive porcine cytomegalovirus infection. Virol J. 2018, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanová, L.; Moutelíková, R.; Prodělalová, J.; Faldyna, M.; Toman, M.; Salát, J. Monocyte derived macrophages as an appropriate model for porcine cytomegalovirus immunobiology studies. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2018, 197, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollackner, B.; Mueller, N.J.; Houser, S.; Qawi, I.; Soizic, D.; Knosalla, C.; Buhler, L.; Dor, F.J.; Awwad, M.; Sachs, D.H.; Cooper, D.K.; Robson, S.C.; Fishman, J.A. Porcine cytomegalovirus and coagulopathy in pig-to-primate xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 2003, 75, 1841–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, N.J.; Barth, R.N.; Yamamoto, S.; Kitamura, H.; Patience, C.; Yamada, K.; Cooper, D.K.; Sachs, D.H.; Kaur, A.; Fishman, J.A. Activation of cytomegalovirus in pig-to-primate organ xenotransplantation. J Virol. 2002, 76, 4734–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Längin, M.; Mayr, T.; Reichart, B.; Michel, S.; Buchholz, S.; Guethoff, S.; Dashkevich, A.; Baehr, A.; Egerer, S.; Bauer, A.; Mihalj, M.; Panelli, A.; Issl, L.; Ying, J.; Fresch, A.K.; Buttgereit, I.; Mokelke, M.; Radan, J.; Werner, F.; Lutzmann, I.; Steen, S.; Sjöberg, T.; Paskevicius, A.; Qiuming, L.; Sfriso, R.; Rieben, R.; Dahlhoff, M.; Kessler, B.; Kemter, E.; Kurome, M.; Zakhartchenko, V.; Klett, K.; Hinkel, R.; Kupatt, C.; Falkenau, A.; Reu, S.; Ellgass, R.; Herzog, R.; Binder, U.; Wich, G.; Skerra, A.; Ayares, D.; Kind, A.; Schönmann, U.; Kaup, F.J.; Hagl, C.; Wolf, E.; Klymiuk, N.; Brenner, P.; Abicht, J.M. Consistent success in life-supporting porcine cardiac xenotransplantation. Nature. 2018, 564, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J.; Längin, M.; Reichart, B.; Krüger, L.; Fiebig, U.; Mokelke, M.; Radan, J.; Mayr, T.; Milusev, A.; Luther, F.; Sorvillo, N.; Rieben, R.; Brenner, P.; Walz, C.; Wolf, E.; Roshani, B.; Stahl-Hennig, C.; Abicht, J.M. Impact of porcine cytomegalovirus on long-term orthotopic cardiac xenotransplant survival. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 17531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, V.A.; Abicht, J.M.; Reichart, B.; Mayr, T.; Guethoff, S.; Denner, J. Active replication of porcine cytomegalovirus (PCMV) following transplantation of a pig heart into a baboon despite undetected virus in the donor pig. Ann Virol Res. 2016, 2, 1018. [Google Scholar]

- Fiebig, U.; Abicht, J.M.; Mayr, T.; Längin, M.; Bähr, A.; Guethoff, S.; Falkenau, A.; Wolf, E.; Reichart, B.; Shibahara, T.; Denner, J. Distribution of Porcine Cytomegalovirus in Infected Donor Pigs and in Baboon Recipients of Pig Heart Transplantation. Viruses. 2018, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, B.P.; Goerlich, C.E.; Singh, A.K.; Rothblatt, M.; Lau, C.L.; Shah, A.; Lorber, M.; Grazioli, A.; Saharia, K.K.; Hong, S.N.; Joseph, S.M.; Ayares, D.; Mohiuddin, M.M. Genetically Modified Porcine-to-Human Cardiac Xenotransplantation. N Engl J Med. 2022, 387, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, M.M.; Singh, A.K.; Scobie, L.; Goerlich, C.E.; Grazioli, A.; Saharia, K.; Crossan, C.; Burke, A.; Drachenberg, C.; Oguz, C.; Zhang, T.; Lewis, B.; Hershfeld, A.; Sentz, F.; Tatarov, I.; Mudd, S.; Braileanu, G.; Rice, K.; Paolini, J.F.; Bondensgaard, K.; Vaught, T.; Kuravi, K.; Sorrells, L.; Dandro, A.; Ayares, D.; Lau, C.; Griffith, B.P. Graft dysfunction in compassionate use of genetically engineered pig-to-human cardiac xenotransplantation: A case report. Lancet. 2023, 402, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J. First transplantation of a pig heart from a multiple gene-modified donor porcine cytomegalovirus/roseolovirus, and antiviral drugs. Xenotransplantation 2023, 30, e12800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Tasaki, M.; Sekijima, M.; Wilkinson, R.A.; Villani, V.; Moran, S.G.; Cormack, T.A.; Hanekamp, I.M.; Hawley, R.J.; Arn, J.S.; Fishman, J.A.; Shimizu, A.; Sachs, D.H. Porcine cytomegalovirus infection is associated with early rejection of kidney grafts in a pig to baboon xenotransplantation model. Transplantation. 2014, 98, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedmak, D.D.; Knight, D.A.; Vook, N.C.; et al. Divergent patterns of ELAM-1, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 expression on cytomegalovirus-infected endothelial cells. Transplantation 1994, 58, 1379. [Google Scholar]

- van Dorp, W.T.; van Wieringen, P.A.; Marselis-Jonges, E.; et al. Cytomegalovirus directly enhances MHC class I and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression on cultured proximal tubular epithelial cells. Transplantation 1993, 55, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, A.; Vidotto, V.; Beltramo, T.; Petrini, S.; Torre, D. A review of HIV-1 Tat protein biological effects. Cell Biochem Funct. 2005, 23, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romani, B.; Engelbrecht, S.; Glashoff, R.H. Functions of Tat: The versatile protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 2010, 91, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J. The transmembrane proteins contribute to immunodeficiencies induced by HIV-1 and other retroviruses. AIDS. 2014, 28, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J.; Eschricht, M.; Lauck, M.; Semaan, M.; Schlaermann, P.; Ryu, H.; Akyüz, L. Modulation of cytokine release and gene expression by the immunosuppressive domain of gp41 of HIV-1. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8, e55199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlecht-Louf, G.; Renard, M.; Mangeney, M.; Letzelter, C.; Richaud, A.; Ducos, B.; Bouallaga, I.; Heidmann, T. Retroviral infection in vivo requires an immune escape virulence factor encrypted in the envelope protein of oncoretroviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010, 107, 3782–3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J. Zoonosis and xenozoonosis in xenotransplantation: A proposal for a new classification. Zoonoses Public Health. 2023, 70, 578–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebig, U.; Holzer, A.; Ivanusic, D.; Plotzki, E.; Hengel, H.; Neipel, F.; Denner, J. Antibody Cross-Reactivity between Porcine Cytomegalovirus (PCMV) and Human Herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6). Viruses. 2017, 9, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looney, R.J.; Huggins, J. Use of intravenous immunoglobulin G (IVIG). Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2006, 19, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).