Submitted:

15 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Autoradiographic Analyses of the Density of α1-AR, α2-AR, and β-AR Receptors in the Brains of Triple ABD-KO Mice

2.2. Neurotransmitters’ and Their Metabolite Levels in the Cerebral Hypothalamic Tissues of Genetically Modified Mice

2.3. The Impact of α1-AR Subtype-Specific Deletions and Antidepressant Drugs on the mRNA Levels of Remaining α1-AR Subtypes

2.4. Assessment of the Impact of α1-AR Subtype Deletions and Antidepressant Drugs on the Gene Expression Profile

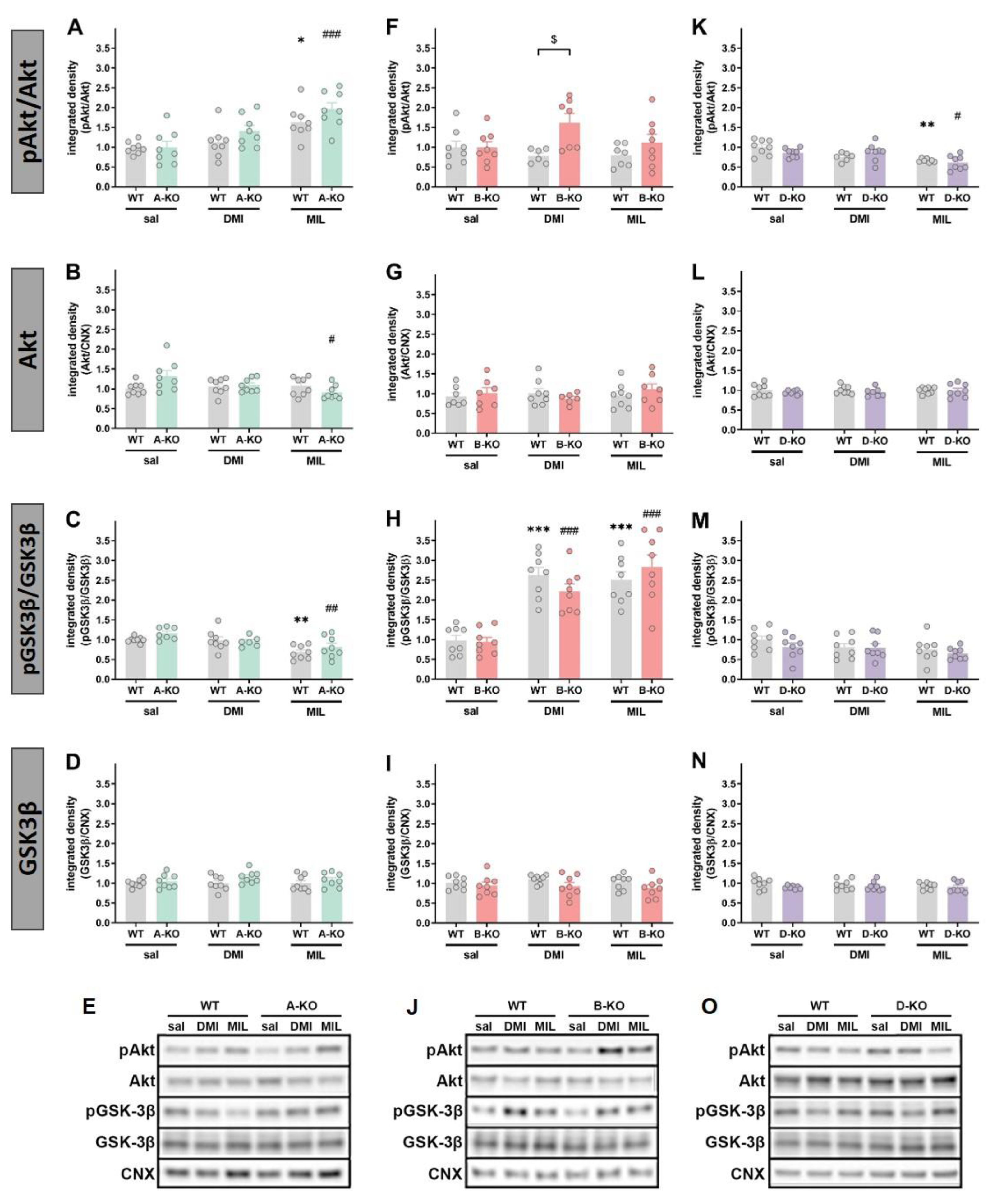

2.5. Evaluation of the Impact of α1-AR Subtypes’ Deletions and Repeatedly Given Antidepressant Drugs on the Phosphorylation of Selected Protein Kinases

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Mice Breeding and Genotyping

4.3. Drugs

4.4. Autoradiography of Adrenergic Receptors in the Brain of WT and ABD-KO Mice

4.4.1. [3H]prazosin Binding to α1-AR

4.4.2. [3H]RX821002 Binding to α2-ARs

4.4.3. [3H]CGP121 Binding to β-ARs

4.4.4. Quantitative Image Analysis of the Autoradiographs

4.5. Measurement of Neurotransmitters and Their Metabolite Levels in Brain Tissue

4.6. RNA Isolation and Gene Expression Analysis

4.7. Gene Expression Profiling

4.8. Western Blot Analyses of Protein Levels

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| α1-AR | α1-adrenergic receptors |

| Akt | Akt kinase, also known as protein kinase B (PKB) |

| CAM | constitutively active mutant |

| DA | dopamine |

| DAG | diacylglycerol |

| DMI | desipramine |

| DOPAC | 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid |

| ERK1/2 | extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 |

| GPCR | G-protein-coupled receptor |

| GSK3β | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta |

| 5-HIAA | 5-hydroxy indole acetic acid |

| HIP | hippocampus |

| HPA | hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis |

| HPRT | hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase |

| 5-HT | serotonin |

| HVA | homovanillic acid |

| HY | hypothalamus |

| LTP | long-term potentiation |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MIL | milnacipran |

| MSA | multiple system atrophy |

| NA | noradrenaline |

| NRI | norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor |

| PFC | prefrontal cortex |

| PGK1 | phosphoglycerate kinase 1 |

| PI3K | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PKC | protein kinase C |

| PLC | phospholipase Cβ |

| SNRI | serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors |

| TCA | tricyclic antidepressants |

| UHPLC | ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography |

| WT | wild-type |

References

- Aston-Jones, G.; Rajkowski, J.; Cohen, J. Role of Locus Coeruleus in Attention and Behavioral Flexibility. Biological Psychiatry 1999, 46, 1309–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berridge, C.W.; Waterhouse, B.D. The Locus Coeruleus–Noradrenergic System: Modulation of Behavioral State and State-Dependent Cognitive Processes. Brain Research Reviews 2003, 42, 33–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton-Provencher, V.; Drummond, G.T.; Sur, M. Locus Coeruleus Norepinephrine in Learned Behavior: Anatomical Modularity and Spatiotemporal Integration in Targets. Front. Neural Circuits 2021, 15, 638007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, S.P.H.; Benson, H.E.; Faccenda, E.; Pawson, A.J.; Sharman, J.L.; McGrath, J.C.; Catterall, W.A.; Spedding, M.; Peters, J.A.; Harmar, A.J.; et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Overview. British J Pharmacology 2013, 170, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, S.P.H.; Benson, H.E.; Faccenda, E.; Pawson, A.J.; Sharman, J.L.; Spedding, M.; Peters, J.A.; Harmar, A.J. CGTP Collaborators The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G Protein-Coupled Receptors. British J Pharmacology 2013, 170, 1459–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieble, J.P.; Bylund, D.B.; Clarke, D.E.; Eikenburg, D.C.; Langer, S.Z.; Lefkowitz, R.J.; Minneman, K.P.; Ruffolo, R.R. International Union of Pharmacology. X. Recommendation for Nomenclature of Alpha 1-Adrenoceptors: Consensus Update. Pharmacol Rev 1995, 47, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinaga, J.; García-Sáinz, J.A.; Pupo, A.S. Updates in the Function and Regulation of α 1 -adrenoceptors. British J Pharmacology 2019, 176, 2343–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalepa, I.; Kreiner, G.; Bielawski, A.; Rafa-Zabłocka, K.; Roman, A. α1-Adrenergic Receptor Subtypes in the Central Nervous System: Insights from Genetically Engineered Mouse Models. Pharmacological Reports 2013, 65, 1489–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, D.M. α1-Adrenergic Receptors in Neurotransmission, Synaptic Plasticity, and Cognition. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 581098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinaga, J.; Lima, V.; Kiguti, L.R.D.A.; Hebeler-Barbosa, F.; Alcántara-Hernández, R.; García-Sáinz, J.A.; Pupo, A.S. Differential Phosphorylation, Desensitization, and Internalization of α 1A−Adrenoceptors Activated by Norepinephrine and Oxymetazoline. Mol Pharmacol 2013, 83, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcántara-Hernández, R.; Hernández-Méndez, A.; Romero-Ávila, M.T.; Alfonzo-Méndez, M.A.; Pupo, A.S.; García-Sáinz, J.A. Noradrenaline, Oxymetazoline and Phorbol Myristate Acetate Induce Distinct Functional Actions and Phosphorylation Patterns of α1A-Adrenergic Receptors. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2017, 1864, 2378–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalothorn, D.; McCune, D.F.; Edelmann, S.E.; Garcı́a-Cazarı́n, M.L.; Tsujimoto, G.; Piascik, M.T. Differences in the Cellular Localization and Agonist-Mediated Internalization Properties of the α 1 -Adrenoceptor Subtypes. Mol Pharmacol 2002, 61, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotecchia, S. The α 1 -Adrenergic Receptors: Diversity of Signaling Networks and Regulation. Journal of Receptors and Signal Transduction 2010, 30, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcı́a-Sáinz, J.A.; Vázquez-Prado, J.; Del Carmen Medina, L. α1-Adrenoceptors: Function and Phosphorylation. European Journal of Pharmacology 2000, 389, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sáinz, J.A.; Vázquez-Cuevas, F.G.; Romero-Ávila, M.T. Phosphorylation and Desensitization of α1d-Adrenergic Receptors. Biochemical Journal 2001, 353, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Aso, M.; Segura, V.; Montó, F.; Barettino, D.; Noguera, M.A.; Milligan, G.; D’Ocon, P. The Three α1-Adrenoceptor Subtypes Show Different Spatio-Temporal Mechanisms of Internalization and ERK1/2 Phosphorylation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2013, 1833, 2322–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, V.; Pérez-Aso, M.; Montó, F.; Carceller, E.; Noguera, M.A.; Pediani, J.; Milligan, G.; McGrath, I.C.; D’Ocon, P. Differences in the Signaling Pathways of α1A- and α1B-Adrenoceptors Are Related to Different Endosomal Targeting. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotecchia, S.; Del Vescovo, C.D.; Colella, M.; Caso, S.; Diviani, D. The Alpha1-Adrenergic Receptors in Cardiac Hypertrophy: Signaling Mechanisms and Functional Implications. Cellular Signalling 2015, 27, 1984–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docherty, J.R. Subtypes of Functional α1-Adrenoceptor. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.C. Localization of α-adrenoceptors: JR V Ane M Edal L Ecture. British J Pharmacology 2015, 172, 1179–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, D.M. Current Developments on the Role of α1-Adrenergic Receptors in Cognition, Cardioprotection, and Metabolism. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 652152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanbe, A.; Tanaka, Y.; Fujiwara, Y.; Tsumura, H.; Yamauchi, J.; Cotecchia, S.; Koike, K.; Tsujimoto, G.; Tanoue, A. α1-Adrenoceptors Are Required for Normal Male Sexual Function. British Journal of Pharmacology 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnerstall, J.R.; Fernandez, I.; Orensanz, L.M. The Alpha-Adrenergic Receptor: Radiohistochemical Analysis of Functional Characteristics and Biochemical Differences. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 1985, 22, 859–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papay, R.; Gaivin, R.; McCune, D.F.; Rorabaugh, B.R.; Macklin, W.B.; McGrath, J.C.; Perez, D.M. Mouse α1B -adrenergic Receptor Is Expressed in Neurons and NG2 Oligodendrocytes. J of Comparative Neurology 2004, 478, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papay, R.; Gaivin, R.; Jha, A.; Mccune, D.F.; Mcgrath, J.C.; Rodrigo, M.C.; Simpson, P.C.; Doze, V.A.; Perez, D.M. Localization of the Mouse α1A-Adrenergic Receptor (AR) in the Brain: α1A-AR Is Expressed in Neurons, GABAergic Interneurons, and NG2 Oligodendrocyte Progenitors. Journal of Comparative Neurology 2006, 497, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadalge, A.; Coughlin, L.; Fu, H.; Wang, B.; Valladares, O.; Valentino, R.; Blendy, J.A. α1d Adrenoceptor Signaling Is Required for Stimulus Induced Locomotor Activity. Mol Psychiatry 2003, 8, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalepa, I.; Sulser, F. New Hypotheses to Guide Future Antidepressant Drug Development. In Antidepressants: Past, Present and Future; Preskorn, S.H., Feighner, J.P., Stanga, C.Y., Ross, R., Eds.; Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2004; ISBN 978-3-642-62135-2. [Google Scholar]

- Vetulani, J.; Nalepa, I. Antidepressants: Past, Present and Future. European Journal of Pharmacology 2000, 405, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalepa, I.; Kreiner, G.; Kowalska, M.; Sanak, M.; Zelek-Molik, A.; Vetulani, J. Repeated Imipramine and Electroconvulsive Shock Increase α1A-Adrenoceptor mRNA Level in Rat Prefrontal Cortex. European Journal of Pharmacology 2002, 444, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, R.S.; Aghajanian, G.K.; Sanacora, G.; Krystal, J.H. Synaptic Plasticity and Depression: New Insights from Stress and Rapid-Acting Antidepressants. Nat Med 2016, 22, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duric, V.; Duman, R.S. Depression and Treatment Response: Dynamic Interplay of Signaling Pathways and Altered Neural Processes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskoski, R. ERK1/2 MAP Kinases: Structure, Function, and Regulation. Pharmacological Research 2012, 66, 105–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, Y.; Rizavi, H.S.; Roberts, R.C.; Conley, R.C.; Tamminga, C.A.; Pandey, G.N. Reduced Activation and Expression of ERK1/2 MAP Kinase in the Post-mortem Brain of Depressed Suicide Subjects. Journal of Neurochemistry 2001, 77, 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalewska, T.; Bielawski, A.; Stanaszek, L.; Wieczerzak, K.; Ziemka-Nałęcz, M.; Nalepa, I. Imipramine Administration Induces Changes in the Phosphorylation of FAK and PYK2 and Modulates Signaling Pathways Related to Their Activity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - General Subjects 2016, 1860, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jope, R.; Roh, M.-S. Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 (GSK3) in Psychiatric Diseases and Therapeutic Interventions. CDT 2006, 7, 1421–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcántara Hernández, R.; García-Sáinz, J.A. Roles of Phosphoinositide-Dependent Kinase-1 in α1B-Adrenoceptor Phosphorylation and Desensitization. European Journal of Pharmacology 2012, 674, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcántara-Hernández, R.; Carmona-Rosas, G.; Hernández-Espinosa, D.A.; García-Sáinz, J.A. Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Modulates α1A-Adrenergic Receptor Action and Regulation. European Journal of Cell Biology 2020, 99, 151072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballou, L.M.; Cross, M.E.; Huang, S.; McReynolds, E.M.; Zhang, B.-X.; Lin, R.Z. Differential Regulation of the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt and P70 S6 Kinase Pathways by the α1A-Adrenergic Receptor in Rat-1 Fibroblasts. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2000, 275, 4803–4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballou, L.M.; Lin, H.-Y.; Fan, G.; Jiang, Y.-P.; Lin, R.Z. Activated Gαq Inhibits P110α Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase and Akt. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 23472–23479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccurello, R.; Bielawski, A.; Zelek-Molik, A.; Vetulani, J.; Kowalska, M.; D’Amato, F.R.; Nalepa, I. Brief Maternal Separation Affects Brain α1-Adrenoceptors and Apoptotic Signaling in Adult Mice. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2014, 48, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalepa, I.; Vetulani, J.; Borghi, V.; Kowalska, M.; Przewłocka, B.; Pavone, F. Formalin Hindpaw Injection Induces Changes in the [3H]Prazosin Binding to α1-Adrenoceptors in Specific Regions of the Mouse Brain and Spinal Cord. J Neural Transm 2005, 112, 1309–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalepa, I.; Witarski, T.; Kowalska, M.; Vetulani, J. Effect of Cocaine Sensitization on α1-Adrenoceptors in Brain Regions of the Rat: An Autoradiographic Analysis. Pharmacological Reports 2006, 58, 827. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sanders, J.D.; Szot, P.; Weinshenker, D.; Happe, H.K.; Bylund, D.B.; Murrin, L.C. Analysis of Brain Adrenergic Receptors in Dopamine-β-Hydroxylase Knockout Mice. Brain Research 2006, 1109, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziedzicka-Wasylewska, M.; Faron-Górecka, A.; Kuśmider, M.; Drozdowska, E.; Rogóż, Z.; Siwanowicz, J.; Caron, M.G.; Bönisch, H. Effect of Antidepressant Drugs in Mice Lacking the Norepinephrine Transporter. Neuropsychopharmacol 2006, 31, 2424–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis: A Knowledge-Based Approach for Interpreting Genome-Wide Expression Profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, H.; Muruganujan, A.; Thomas, P.D. PANTHER in 2013: Modeling the Evolution of Gene Function, and Other Gene Attributes, in the Context of Phylogenetic Trees. Nucleic Acids Research 2012, 41, D377–D386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- España, R.A.; Schmeichel, B.E.; Berridge, C.W. Norepinephrine at the Nexus of Arousal, Motivation and Relapse. Brain Research 2016, 1641, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doze, V.A.; Handel, E.M.; Jensen, K.A.; Darsie, B.; Luger, E.J.; Haselton, J.R.; Talbot, J.N.; Rorabaugh, B.R. α1A- and α1B-Adrenergic Receptors Differentially Modulate Antidepressant-like Behavior in the Mouse. Brain Research 2009, 1285, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doze, V.A.; Papay, R.S.; Goldenstein, B.L.; Gupta, M.K.; Collette, K.M.; Nelson, B.W.; Lyons, M.J.; Davis, B.A.; Luger, E.J.; Wood, S.G.; et al. Long-Term α 1A -Adrenergic Receptor Stimulation Improves Synaptic Plasticity, Cognitive Function, Mood, and Longevity. Mol Pharmacol 2011, 80, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuscik, M.J.; Sands, S.; Ross, S.A.; Waugh, D.J.J.; Gaivin, R.J.; Morilak, D.; Perez, D.M. Overexpression of the α1B-Adrenergic Receptor Causes Apoptotic Neurodegeneration: Multiple System Atrophy. Nat Med 2000, 6, 1388–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishima, K.; Tanoue, A.; Tsuda, M.; Hasebe, N.; Fukue, Y.; Egashira, N.; Takano, Y.; Kamiya, H.; Tsujimoto, G.; Iwasaki, K.; et al. Characteristics of Behavioral Abnormalities in α1d-Adrenoceptors Deficient Mice. Behavioural Brain Research 2004, 152, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sáinz, J.A.; Romero-Ávila, M.T.; Medina, L.D.C. α1D-Adrenergic Receptors. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier, 2010; Vol. 484, pp. 109–125 ISBN 978-0-12-381298-8.

- Konstandi, M.; Johnson, E.; Lang, M.A.; Malamas, M.; Marselos, M. NORADRENALINE, DOPAMINE, SEROTONIN: DIFFERENT EFFECTS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL STRESS ON BRAIN BIOGENIC AMINES IN MICE AND RATS. Pharmacological Research 2000, 41, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillman, P.K. Tricyclic Antidepressant Pharmacology and Therapeutic Drug Interactions Updated. British J Pharmacology 2007, 151, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puozzo, C.; Panconi, E.; Deprez, D. Pharmacology and Pharmacokinetics of Milnacipran. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 2002, 17, S25–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielarz, P.; Kuśmierczyk, J.; Rafa-Zabłocka, K.; Chorązka, K.; Kowalska, M.; Satała, G.; Nalepa, I. Antidepressants Differentially Regulate Intracellular Signaling from α1-Adrenergic Receptor Subtypes in Vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, A.; Hogan, E.L.; Pahan, K. Ceramide and Neurodegeneration: Susceptibility of Neurons and Oligodendrocytes to Cell Damage and Death. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2009, 278, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbins, E.; Palmada, M.; Reichel, M.; Lüth, A.; Böhmer, C.; Amato, D.; Müller, C.P.; Tischbirek, C.H.; Groemer, T.W.; Tabatabai, G.; et al. Acid Sphingomyelinase–Ceramide System Mediates Effects of Antidepressant Drugs. Nat Med 2013, 19, 934–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornhuber, J.; Müller, C.P.; Becker, K.A.; Reichel, M.; Gulbins, E. The Ceramide System as a Novel Antidepressant Target. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2014, 35, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbins, E.; Walter, S.; Becker, K.A.; Halmer, R.; Liu, Y.; Reichel, M.; Edwards, M.J.; Müller, C.P.; Fassbender, K.; Kornhuber, J. A Central Role for the Acid Sphingomyelinase/Ceramide System in Neurogenesis and Major Depression. Journal of Neurochemistry 2015, 134, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinoff, A.; Herrmann, N.; Lanctôt, K.L. Ceramides and Depression: A Systematic Review. Journal of Affective Disorders 2017, 213, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, F.; Edwards, M.J.; Mühle, C.; Carpinteiro, A.; Wilson, G.C.; Wilker, B.; Soddemann, M.; Keitsch, S.; Scherbaum, N.; Müller, B.W.; et al. Ceramide Levels in Blood Plasma Correlate with Major Depressive Disorder Severity and Its Neutralization Abrogates Depressive Behavior in Mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2022, 298, 102185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, P.; Hajka, D.; Wójcicka, O.; Rakus, D.; Gizak, A. GSK3β: A Master Player in Depressive Disorder Pathogenesis and Treatment Responsiveness. Cells 2020, 9, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, R.; Mesquita, A.R.; Bessa, J.; Sousa, J.C.; Sotiropoulos, I.; Leão, P.; Almeida, O.F.X.; Sousa, N. Lithium Blocks Stress-Induced Changes in Depressive-like Behavior and Hippocampal Cell Fate: The Role of Glycogen-Synthase-Kinase-3β. Neuroscience 2008, 152, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, H.; Voleti, B.; Banasr, M.; Sarhan, M.; Duric, V.; Girgenti, M.J.; DiLeone, R.J.; Newton, S.S.; Duman, R.S. Wnt2 Expression and Signaling Is Increased by Different Classes of Antidepressant Treatments. Biological Psychiatry 2010, 68, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beurel, E.; Song, L.; Jope, R.S. Inhibition of Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Is Necessary for the Rapid Antidepressant Effect of Ketamine in Mice. Mol Psychiatry 2011, 16, 1068–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, M.; Abrial, E.; Jope, R.S.; Beurel, E. GSK3β Isoform-selective Regulation of Depression, Memory and Hippocampal Cell Proliferation. Genes Brain and Behavior 2016, 15, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omata, N.; Chiu, C.-T.; Moya, P.R.; Leng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Hunsberger, J.G.; Leeds, P.; Chuang, D.-M. Lentivirally Mediated GSK-3β Silencing in the Hippocampal Dentate Gyrus Induces Antidepressant-like Effects in Stressed Mice. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2011, 14, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, W.N. Synaptic Plasticity in Depression: Molecular, Cellular and Functional Correlates. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2013, 43, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballou, L.M.; Tian, P.-Y.; Lin, H.-Y.; Jiang, Y.-P.; Lin, R.Z. Dual Regulation of Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3β by the α1A-Adrenergic Receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 40910–40916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeGates, T.A.; Kvarta, M.D.; Thompson, S.M. Sex Differences in Antidepressant Efficacy. Neuropsychopharmacol 2019, 44, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokras, N.; Hodes, G.E.; Bangasser, D.A.; Dalla, C. Sex Differences in the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis: An Obstacle to Antidepressant Drug Development? British J Pharmacology 2019, 176, 4090–4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangasser, D.A.; Cuarenta, A. Sex Differences in Anxiety and Depression: Circuits and Mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci 2021, 22, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sramek, J.J.; Murphy, M.F.; Cutler, N.R. Sex Differences in the Psychopharmacological Treatment of Depression. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2016, 18, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlidi, P.; Kokras, N.; Dalla, C. Sex Differences in Depression and Anxiety. In Sex Differences in Brain Function and Dysfunction; Gibson, C., Galea, L.A.M., Eds.; Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; ISBN 978-3-031-26722-2. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, J.; Ryan, C.; Curley, A.; Mulcaire, J.; Kelly, J.P. Sex Differences in Baseline and Drug-Induced Behavioural Responses in Classical Behavioural Tests. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2012, 37, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Frazer, A. Influence of Acute or Chronic Administration of Ovarian Hormones on the Effects of Desipramine in the Forced Swim Test in Female Rats. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 3685–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma-Corvi, S.; García-Fuster, M.J. Revisiting the Antidepressant-like Effects of Desipramine in Male and Female Adult Rats: Sex Disparities in Neurochemical Correlates. Pharmacol. Rep 2022, 74, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, S.; Arita, S. Differential Effects of Milnacipran, Fluvoxamine and Paroxetine for Depression, Especially in Gender. Eur. psychiatr. 2003, 18, 418–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, S.; Sato, K.; Yoshida, K.; Higuchi, H.; Takahashi, H.; Kamata, M.; Ito, K.; Ohkubo, T.; Shimizu, T. Gender Differences in the Clinical Effects of Fluvoxamine and Milnacipran in Japanese Major Depressive Patients. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007, 61, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; He, J.; Hou, J.; Lin, F.; Tian, J.; Kurihara, H. Gender Differences in CMS and the Effects of Antidepressant Venlafaxine in Rats. Neurochemistry International 2013, 63, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, V.C.; Hughes, R.N. Drug-, Dose- and Sex-Dependent Effects of Chronic Fluoxetine, Reboxetine and Venlafaxine on Open-Field Behavior and Spatial Memory in Rats. Behavioural Brain Research 2015, 281, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ma, L.; Jiang, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, R. Study of Sex Differences in Duloxetine Efficacy for Depression in Transgenic Mouse Models. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Wang, L.; Yang, B.; Li, X. Sex Differences in Noradrenergic Modulation of Attention and Impulsivity in Rats. Psychopharmacology 2021, 238, 2167–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokosh, D.G.; Simpson, P.C. Knockout of the α1A͞C-Adrenergic Receptor Subtype: The α1A͞C Is Expressed in Resistance Arteries and Is Required to Maintain Arterial Blood Pressure. MEDICAL SCIENCES.

- Cavalli, A.; Lattion, A.-L.; Hummler, E.; Nenniger, M.; Pedrazzini, T.; Aubert, J.-F.; Michel, M.C.; Yang, M.; Lembo, G.; Vecchione, C.; et al. Decreased Blood Pressure Response in Mice Deficient of The. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 11589–11594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanoue, A.; Nasa, Y.; Koshimizu, T.; Shinoura, H.; Oshikawa, S.; Kawai, T.; Sunada, S.; Takeo, S.; Tsujimoto, G. The α1D-Adrenergic Receptor Directly Regulates Arterial Blood Pressure via Vasoconstriction. J. Clin. Invest. 2002, 109, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafa–Zabłocka, K.; Kreiner, G.; Bagińska, M.; Kuśmierczyk, J.; Parlato, R.; Nalepa, I. Transgenic Mice Lacking CREB and CREM in Noradrenergic and Serotonergic Neurons Respond Differently to Common Antidepressants on Tail Suspension Test. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 13515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxinos, G.; Franklin, K.B.J. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates; Academic Press, 2001; ISBN 978-0-12-547636-2.

- Haduch, A.; Bromek, E.; Wojcikowski, J.; Gołembiowska, K.; Daniel, W.A. Melatonin Supports CYP2D-Mediated Serotonin Synthesis in the Brain. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2016, 44, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haduch, A.; Danek, P.J.; Kuban, W.; Pukło, R.; Alenina, N.; Gołębiowska, J.; Popik, P.; Bader, M.; Daniel, W.A. Cytochrome P450 2D (CYP2D) Enzyme Dysfunction Associated with Aging and Serotonin Deficiency in the Brain and Liver of Female Dark Agouti Rats. Neurochemistry International 2022, 152, 105223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, G.; Bierhoff, H.; Armentano, M.; Rodriguez-Parkitna, J.; Sowodniok, K.; Naranjo, J.R.; Bonfanti, L.; Liss, B.; Schütz, G.; Grummt, I.; et al. A Neuroprotective Phase Precedes Striatal Degeneration upon Nucleolar Stress. Cell Death Differ 2013, 20, 1455–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentleman, R.C.; Carey, V.J.; Bates, D.M.; Bolstad, B.; Dettling, M.; Dudoit, S.; Ellis, B.; Gautier, L.; Ge, Y.; Gentry, J.; et al. Bioconductor: Open Software Development for Computational Biology and Bioinformatics. Genome Biology 2004, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelek-Molik, A.; Bobula, B.; Gądek-Michalska, A.; Chorązka, K.; Bielawski, A.; Kuśmierczyk, J.; Siwiec, M.; Wilczkowski, M.; Hess, G.; Nalepa, I. Psychosocial Crowding Stress-Induced Changes in Synaptic Transmission and Glutamate Receptor Expression in the Rat Frontal Cortex. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).