1. Introduction

In 1927, Cochrane [1] noted that the elastic resistance in hallux dorsiflexion remained after cheilectomy or dorsiflexion osteotomy of the metatarsal head. He hypothesized that this hallux rigidus was attributed to shortened and contracted structures on the plantar aspect of the joint. To address this, a novel surgery was devised, wherein a longitudinal skin incision was made over the plantar aspect of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon was secured, and the joint capsule, flexor hallucis brevis (FHB) tendon, and plantar portion of the lateral ligament were divided. This surgery was performed on 12 patients with hallux rigidus, all of whom were satisfied with the outcomes. Notably, the elastic resistance during dorsiflexion disappeared, and there were no cases of recurrence. However, despite this great breakthrough, the current treatments for hallux rigidus do not address its causes.

This paper provides a critical review of the current treatment for hallux rigidus. This includes a review of the literature on the etiologies of hallux rigidus, dorsal impingement, functional hallux rigidus, hallux primus elevatus, and long metatarsal, followed by a review of studies on metatarsal decompression osteotomy, metatarsal dorsiflexion osteotomy, and cheilectomy. Finally, studies on arthroscopic cheilectomy were reviewed, and the feasibility of arthroscopic surgery for hallux rigidus, including the arthroscopic Cochrane procedure, was explored.

2. Dorsal Impingement

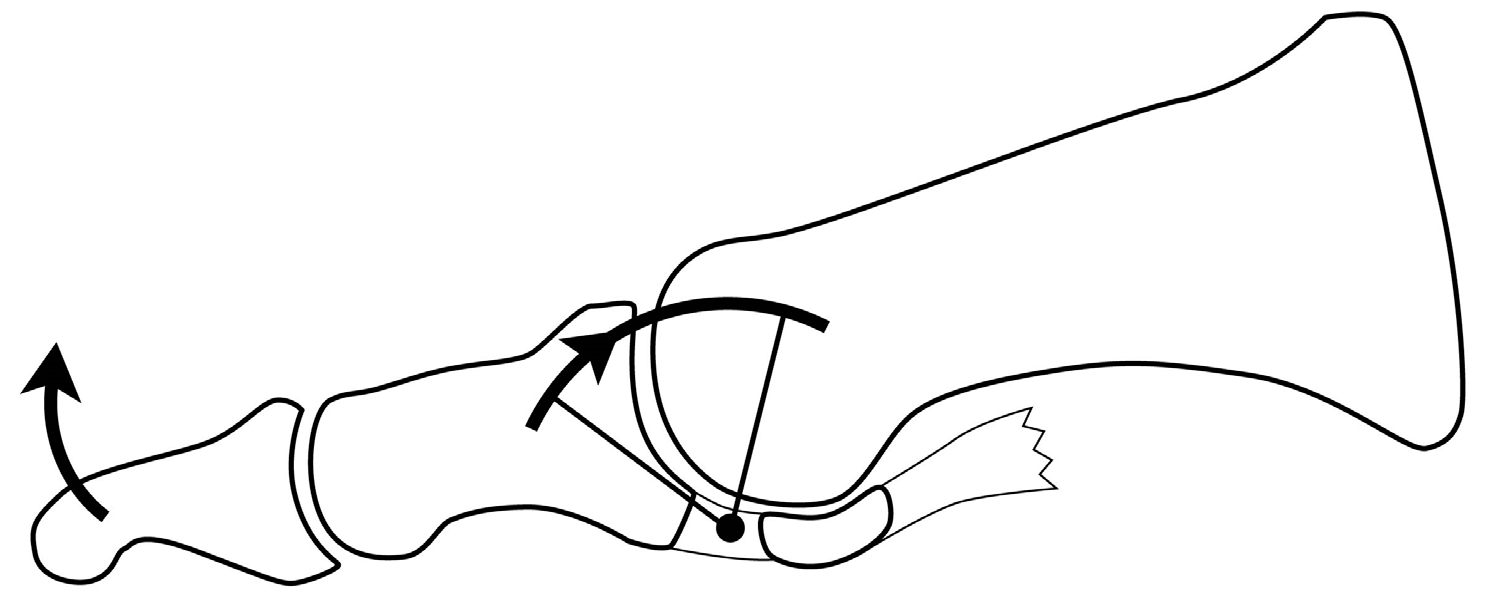

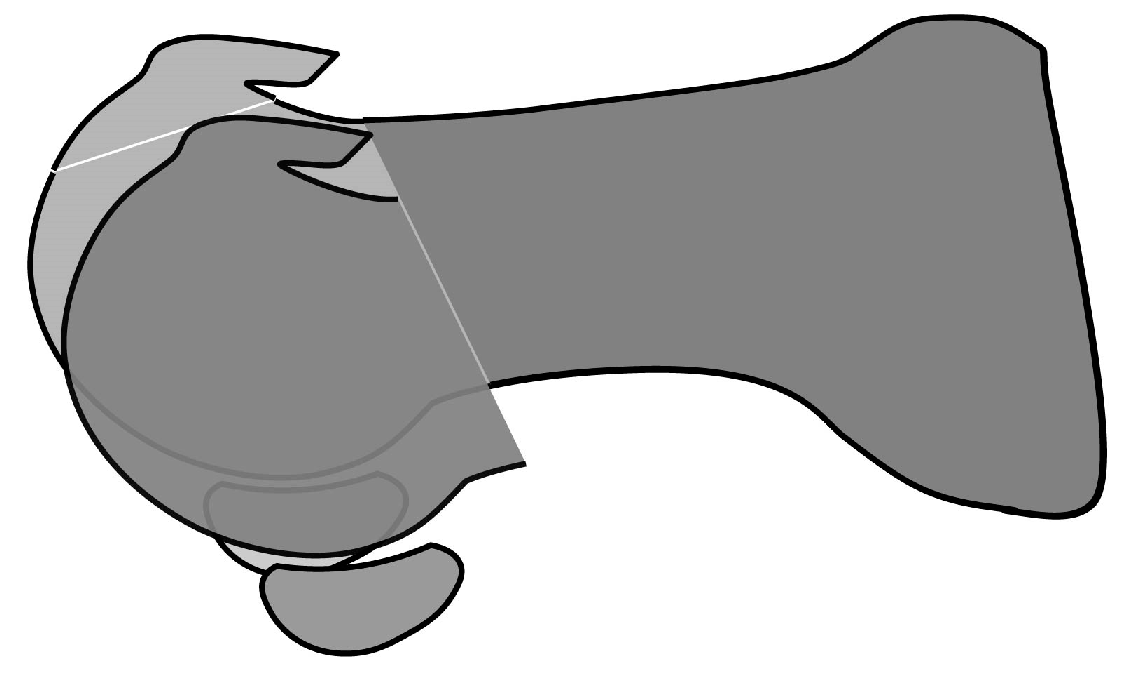

As illustrated by Camasta [2] (

Figure 1), when the soft tissues at the bottom of the first MTP joint in the hallux rigidus contract, the proximal phalanx of the hallux undergoes wire motion centered on that area, similar to a windshield wiper. This causes impingement between the metatarsal head and the dorsal side of the proximal phalanx.

Dorsal impingement causes cartilage defects on the dorsal metatarsal head. Bingold and Collins [3] performed a pathological examination of the surgically resected metatarsal head, which revealed the loss of superficial cartilage layers and irregularity of the calcified line at the base of the articular cartilage. It was hypothesized that FHB contracture causes increased compressive force on the dorsal articular surface, resulting in arthritic changes. Similarly, McMaster [4] showed a pathological photograph of the separating flap of the dorsal articular cartilage of the metatarsal head in a patient with hallux rigidus. It was suspected that the defect caused impingement of the proximal phalanx edge on the dorsal metatarsal head. A previous study by Nakajima [5] on MTP joint arthroscopy included photographs of a case of hallux rigidus, wherein the articular cartilage was lost from the center to the dorsal third of the articular surface, but the cartilage was preserved above that and at the dorsal spur.

Dorsal impingement of the hallux rigidus has also been studied using kinematic approaches. Sheff et al. [6] investigated the axis of motion of an articular surface in cadaveric X-rays. Under normal conditions, the proximal phalanx glided on the articular surface of the metatarsal bone. In hallux rigidus, there was decreased movement of the joint between the sesamoid bones and metatarsal head, and the proximal phalanx surface appeared to be jammed against the metatarsal surface. Flavin et al. [7] found that the stress of the articular cartilage on the dorsal third of the metatarsal head increased in the presence of contractures, from 3.6 MPa under normal loading to 4.3 MPa under a 30% increase in the FHB contracture and to 7.3 MPa under a 30% increase in the plantar fascia contracture. Therefore, contractures of these tissues can damage the articular cartilage on the dorsal third of the metatarsal head.

3. Windlass Mechanism and Functional Hallux Rigidus

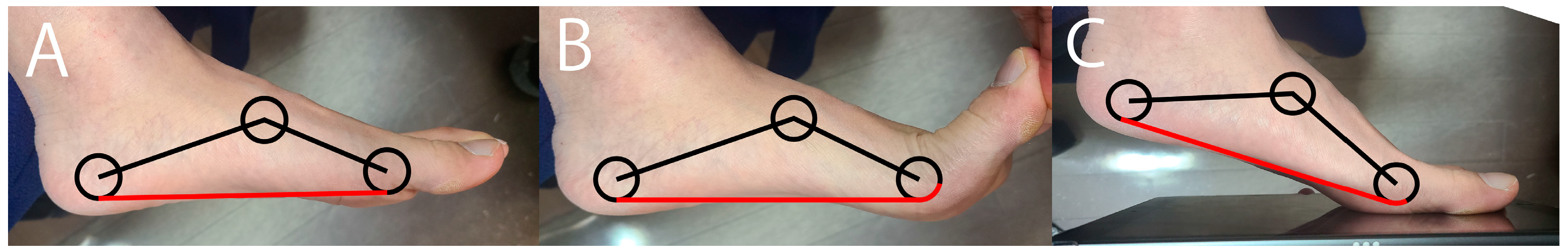

The windlass mechanism explains the restriction of dorsiflexion under the weight-bearing conditions of a normal foot [8] (

Figure 2). Under nonweight-bearing conditions, as the hallux dorsiflexes, the longitudinal arch heightens, and the plantar fascia rolls up to the first MTP joint. Meanwhile, under weight-bearing conditions where the plantar fascia is stretched, the heightening of the longitudinal arch and rolling-up of the plantar fascia are both restricted, thereby limiting dorsiflexion.

This tendency was especially evident in the hallux rigidus due to the slight tightness or shortening of the plantar soft tissues. Dananberg [9,10] coined the term “functional hallux rigidus” to describe the condition wherein dorsiflexion is noticeably restricted only during weight-bearing, but not otherwise. A review article by Maceira and Monteagudo [11] demonstrated a manual test for functional hallux rigidus (

Figure 3), wherein functional hallux rigidus is indicated by dorsiflexion angles of 65°–90° during the nonweight-bearing test and <0° during the weight-bearing test. Nevertheless, the shortening and contracture of plantar soft tissues can be restored in functional hallux rigidus. Shrmus et al [12] designed a comparative experimental study including 20 patients with functional hallux rigidus. After 1 month of sesamoid mobilizations, flexor hallucis strengthening exercises, and gait training, the experimental group achieved a greater hallux dorsiflexion angle and less pain versus the control group.

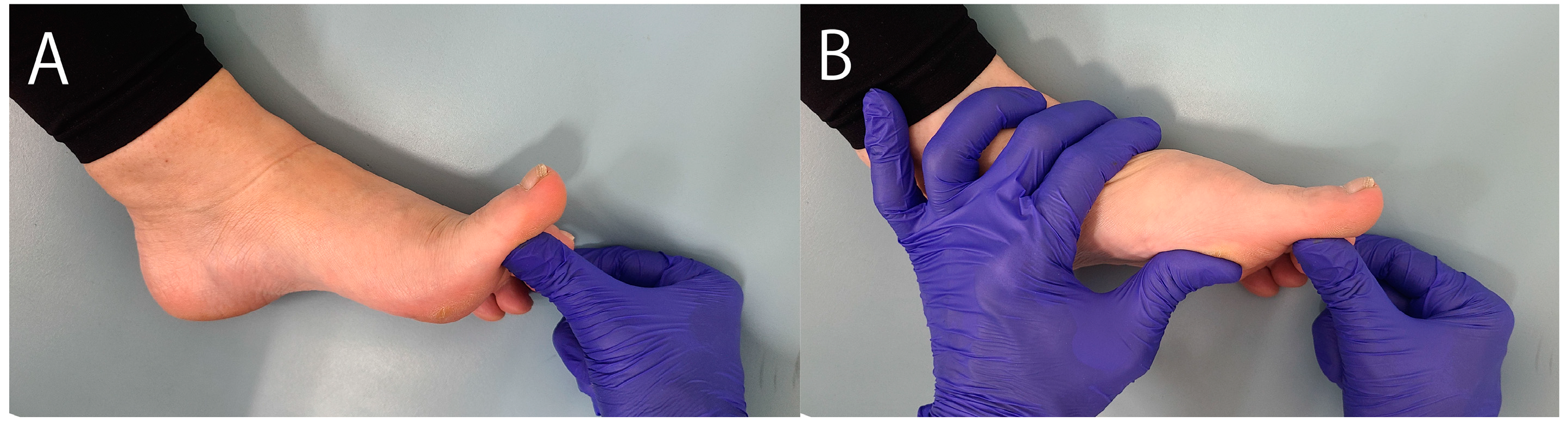

4. Structural Change from Functional Hallux Rigidus to Metatarsal Primus Elevatus

Camasta [2] discussed the similarity of bone alignment between hallux rigidus and hammer toe (

Figure 4). When the tendon is shortened, the most distal bone touches the ground, the second most distal bone plantarflexes, and the third most distal bone dorsiflexes during weight-bearing to stabilize the toe. In this situation, the proximal phalanx is elevated in hammer toe, while the metatarsal is elevated in hallux rigidus.

The structural change from functional hallux rigidus to hallux primus elevatus in hallux rigidus has been supported by the literature. Horton et al. [13] compared the weight-bearing lateral radiographs of 81 patients with hallux rigidus and 50 normal controls. The mean metatarsal elevation of patients with mild or moderate hallux rigidus was comparable to that of controls, whereas this was slightly higher among patients with advanced hallux rigidus versus controls. Similarly, Coughlin et al. [14] found no metatarsal elevation in grades 1 and 2 hallux rigidus, but metatarsal elevation was more common in grades 3 and 4 hallux rigidus versus controls. Furthermore, Shurnas [15] proposed that metatarsal elevation occurs secondary to arthritic changes and decreased range of motion of the MTP joint. In contrast, studies that did not differentiate between the stages of hallux rigidus had conflicting results regarding metatarsal elevation. In a study of weight-bearing radiographs, Meyer et al. [16] found that the average elevation of the first metatarsal was 6.91 mm in 120 randomly selected feet and 5.95 mm in 22 feet with hallux rigidus. This finding casted doubt regarding the existence of the hallux primus elevatus in hallux rigidus. Meanwhile, Roukis [17] compared 100 cases of hallux rigidus versus patients with hallux valgus, plantar fasciitis, and Morton’s disease, revealing a significant elevation of the first metatarsal with respect to the second metatarsal in the hallux rigidus group. Jones et al. [18] devised a method for measuring metatarsal elevation in relation to the proximal phalanx and reported that the first metatarsal was significantly elevated in hallux rigidus versus controls, with high intra- and inter-rater evaluations. Additionally, Anwandar et al. [19] found significant metatarsal elevation when comparing 25 patients with hallux rigidus versus 50 healthy individuals, with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.93 between both observers. These findings suggest that differentiating between the stages of hallux rigidus is essential when evaluating hallux primus elevatus.

5. Long Metatarsal

The long metatarsal is a controversial etiology of hallux rigidus. To the best of our knowledge, studies discussing the metatarsal length in hallux rigidus are scarce. Among the existing studies, Nilsonne [20] evaluated the length of the first metatarsal in 497 normal feet and 49 feet with hallux rigidus. Using the tip of the second metatarsal as a reference, a positive index, zero index, and negative index, respectively, were observed in 34%, 13%, and 52% of normal feet and in 81%, 14%, and 5% of feet with hallux rigidus. However, a comparison of radiographs of patients with and without (n = 51 each) hallux rigidus by Zgonis et al. [21] revealed significantly shorter metatarsal length in patients with hallux rigidus (65.4 vs. 67.7 mm), thus casting doubt on its role in the etiology of hallux rigidus. Meanwhile, in a study of 132 cases with hallux rigidus and a control group of 132 normal feet, Calvo et al. [22] found that the ratio of the metatarsal length to the total foot length was significantly greater in hallux rigidus versus controls. These findings suggest that having a long first metatarsal does not cause limited dorsiflexion unless the tissue on the plantar aspect of the first MTP joint restricts dorsiflexion. However, a long first metatarsal may tend to shorten the plantar tissues.

6. Metatarsal Decompression and Dorsiflexion Osteotomies

Due to the shape of the osteotomy, metatarsal decompression osteotomy is used in the surgical management of hallux primus elevatus and long metatarsals, although its application for each grade varies. [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30] However, Derner et al. [30] stated that metatarsal decompression osteotomy can alleviate pain in hallux rigidus by reducing the compressive force on the dorsal metatarsal head and loosening the soft tissues below the joint.

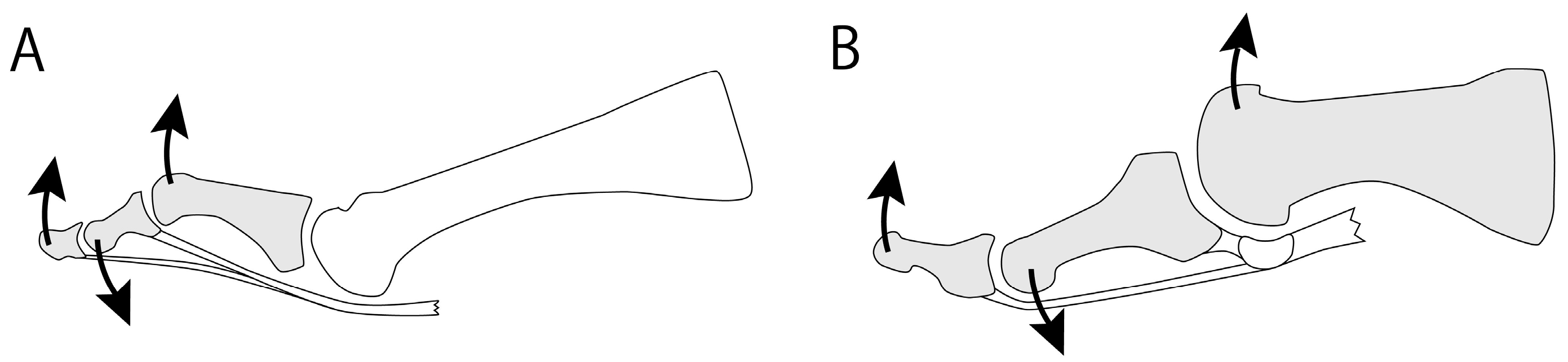

Decompression osteotomy includes various methods such as Youngswick osteotomy [26,27,28,29,30,32] and oblique osteotomy, [23,24,25,33,34,35] which usually result in favorable outcomes except after modified Reverdin Green osteotomy. [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,33,34,35,36] Only one comparative study has been done between osteotomies, which reported similar outcomes between Youngswick and oblique osteotomies. [37] However, because the metatarsal osteotomies reported so far were combined with cheilectomies, it remains unclear whether the improved outcomes were associated with metatarsal osteotomies or cheilectomies. [38] Nakajima [33] believes that cheilectomy is unnecessary if metatarsal osteotomy is able to reduce the compressive force on the dorsal metatarsal head, reporting good outcomes after metatarsal osteotomy without cheilectomy (

Figure 5).

Recent studies have reported the effectivity of metatarsal decompression osteotomy across all grades of hallux rigidus. Saur et al. [34] reported that AOFAS scores improved from 54 to 92 in 87 feet across all stages of hallux rigidus after a mean follow-up of 51 months, with scores of 95% patient being excellent or good. Two studies by Nakajima [33, 35] also reported the effectivity of metatarsal decompression osteotomy in 119 feet across all grades, all with similar improvements in pain. This suggests that plantar soft tissue contracture and dorsal impingement occur in all grades of hallux rigidus, which can be effectively relieved by metatarsal osteotomy in all grades.

One concern in metatarsal decompression osteotomy is plantar pain due to the plantar shift of the metatarsal head. Zammit et al. [39] reported that plantar pressure of hallux rigidus feet was lower under the first MTP joint compared to the first distal phalanx and the second to fourth MTP joints. Bryant et al. [40] reported that plantar pressure under the first MTP joint did not increase after Youngswick osteotomy (n = 17) compared to controls (n = 23). Meanwhile, Nakajima reported that 28% of patients felt discomfort under the metatarsal head after a 7-mm plantar shift of the metatarsal head [33], whereas only 5% felt discomfort after a 3-mm plantar shift. [35]

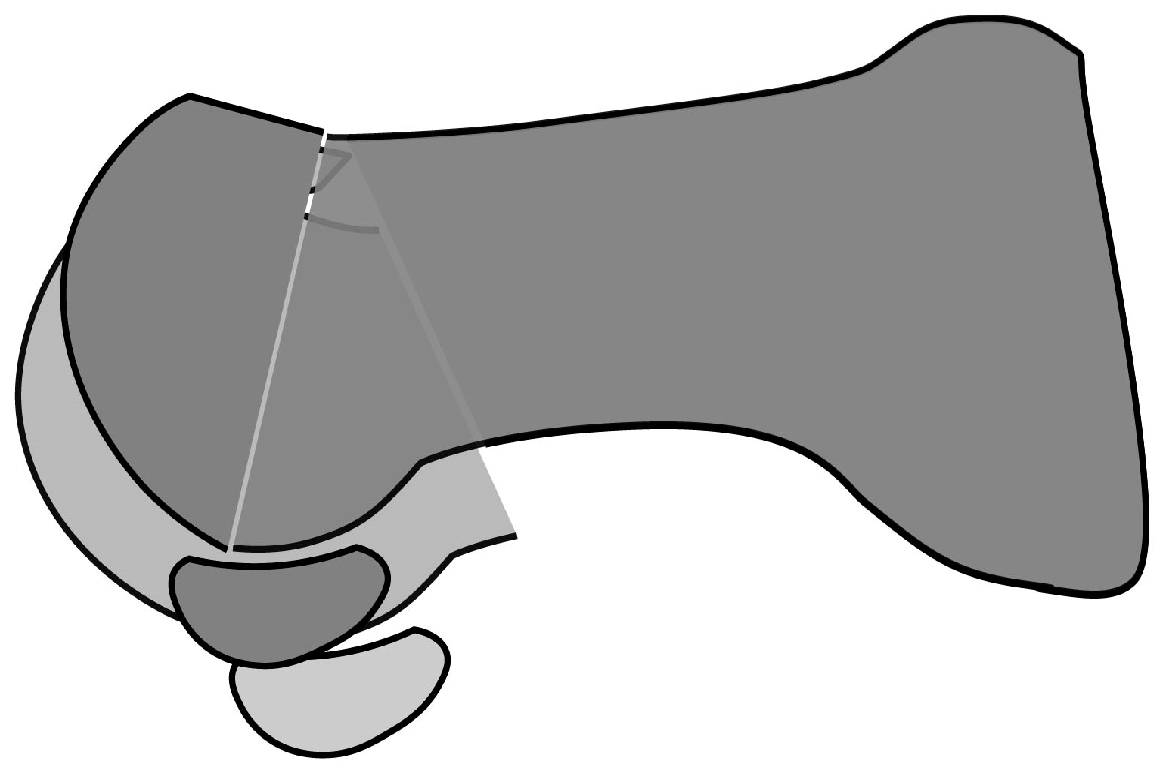

Metatarsal dorsiflexion osteotomy appears to have a similar effect in reducing compressive force on the dorsal articular surface. However, recent studies have reported poor outcomes of dorsiflexion osteotomy in high-grade hallux rigidus. [41, 42] Although both osteotomies reduce compressive force on the dorsal third of the first MTP joint surface, decompression osteotomy loosens the soft tissues below the joint due to the plantar shift of the metatarsal head, whereas dorsiflexion osteotomy does not (

Figure 6). Since dorsiflexion osteotomy does not sufficiently alleviate the compressive force on the joint surface, it results in poor pain relief.

7. Cheilectomy

Cheilectomy is considered the gold standard for early-stage hallux rigidus [43,44], but some recent studies have reported poor results. [45,46,47,48,49] Hattrup and Johnson [45] reviewed 58 patients who underwent cheilectomy, reporting dissatisfaction rates of 15%, 31.8%, and 37.5% among patients with grade 1, 2, and 3 hallux rigidus, respectively. Harrison et al. [46] evaluated 25 patients who underwent cheilectomy with a mean follow-up of 17 months using the Manchester-Oxford Foot and Ankle Questionnaire (MOXFQ); only 84% patients showed improvements in gait, 68% in the social domain, and 59% in the pain domain, while 3 patients subsequently required arthrodesis. A systematic review by Roukis et al. [47] reported that among 706 isolated cheilectomy for hallux rigidus, 8.8% underwent surgical revision of arthrodesis. Sidon et al. [48] found that among 165 patients (169 feet) who underwent cheilectomy with an average follow-up of 6.6 years, 31% felt neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, dissatisfied, or very dissatisfied, 5.3% underwent reoperation, and 24.9% would prefer not to repeat the surgery in the same situation. Lastly, Teoh et al. [49] evaluated 89 patients (98 feet) who underwent cheilectomy with a mean follow-up of 50 months, revealing improvements in visual analog scale (VAS) score (80 to 30) and MOXFQ score (58.6 to 30.5). Additionally, 12% underwent reoperation, and 7% underwent arthrodesis.

Several studies have reported that arthritic changes progress after cheilectomy. Mulier et al. [50] performed cheilectomy in 20 athletes (22 feet) with an average age of 31 years with grade 1 or 2 hallux rigidus and reported fair, good, and excellent ratings in 1, 7, and 14 patients respectively using their own clinical score sheet, but on follow-up, 7 out of 13 patients had progression of radiographic arthritic changes. Easley et al. [51] performed cheilectomy in 57 patients (75 feet) with average follow-up of 63 months, revealing improvements in AOFAS score (45 to 85) and dorsiflexion angle (34° to 64°). However, a considerable number progressed from grade 1 to grades 2 and 3 (9/17 and 6/17, respectively) and from grade 2 to grade 3 (24/39). A review by Tomilinson [52] reported that conversion from cheilectomy to arthrodesis was necessary in up to 25% of patients. This may be because cheilectomy does not move the hallux sesamoids proximally, causing the plantar soft tissue to remain tight and the pressure on the femoral head to persist (

Figure 5).

Although cheilectomy is essentially a joint-destructive surgery, it is still performed in patients with early-stage hallux rigidus. Mann and Clanton [53] demonstrated cheilectomy that removes the dorsal fourth to third of the articular surface, similar to that of Coughlin et al. [54] Because of its destructive nature, normal joint movement is lost. A cadaveric study by Heller et al. [55] reported that cheilectomy increased the dorsiflexion angle but replaced the normal sliding movement with a pivot shift movement.

To the best of our knowledge, there has been only one comparative study between cheilectomy and metatarsal decompression osteotomy. In this study, Cullen et al. [56] compared cheilectomy (341 feet) versus decompression osteotomy (82 feet), revealing a significantly higher 5-year reoperation rate for cheilectomy (8.2% vs. 1.2%).

Cheilectomy is a form of symptomatic treatment that removes the dorsal articular surface where impingement pain occurs, but this does not address the underlying etiology. Thus, Cochrane [1] regarded cheilectomy as illogical. Meanwhile, Geldwert et al. [57] argue that cheilectomy without addressing the underlying etiology is a disadvantage, although they reported good outcomes. This raises the important question: should we not address the etiology when treating the early stages of a disease?

8. Arthroscopic Cheilectomy

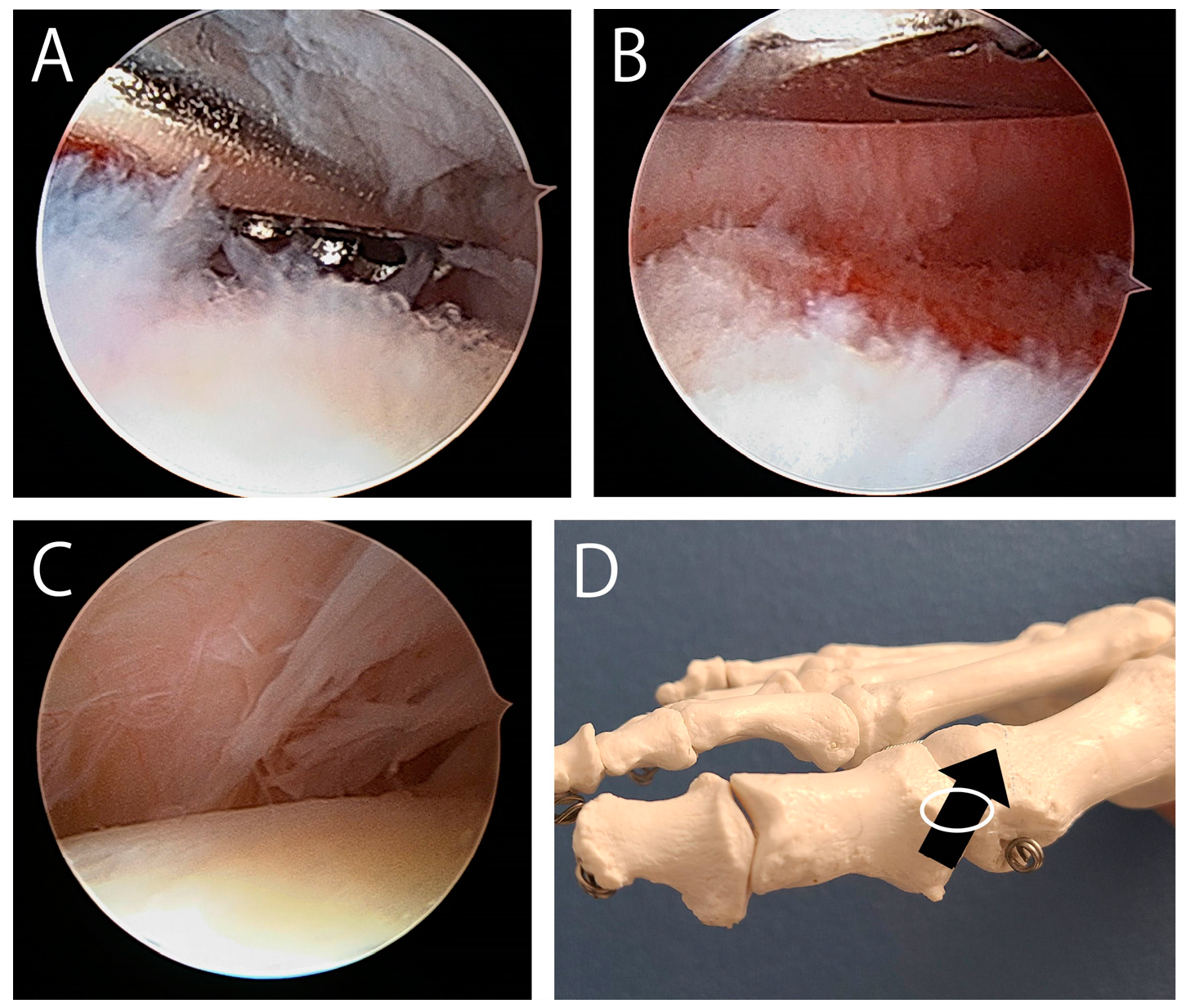

An increasing number of studies have investigated arthroscopic cheilectomy. Some have reported that dorsal exostosis can be resected under arthroscopic guidance, [58-62] but none have provided photographs of this process. Therefore, the specifics of how the exostosis is viewed and removed under arthroscopic guidance remain unclear. Arthroscopically resecting the exostosis can be difficult because of the following reasons. First, since the exostosis occupies the dorsal first MTP joint space, it can be difficult to effectively manipulate both an arthroscope and an abrader in this narrow space. [5] Second, it can be difficult to determine the entire shape of the exostosis during arthroscopic resection. Third, surgeons who are unfamiliar with first MTP joint arthroscopy can have difficulty in differentiating between the normal dorsal view versus in the presence of an exostosis (

Figure 7). To overcome these issues, several recent reports introduced a technique wherein the exostosis was first removed under fluoroscopy, then the joint space was arthroscopically observed. [63,64,65,66,67] Another report used ultrasound instead of fluoroscopy. [68]

Similar clinical outcomes have been reported for arthroscopic and open cheilectomies. Hickey et al. [63] performed arthroscopic cheilectomy in 36 patients with a mean follow-up of 4.7 years, revealing that 28% had no pain, 56% had mild pain (VAS score 34), and 1 patient had extensor hallucis longus tendon rupture. Furthermore, 83% of the patients reported that they would recommend this surgery. Moreover, in a study of 20 patients who underwent arthroscopic cheilectomy, Glenn et al. [64] reported improvements in VAS score (70.5 to 7.5) and dorsiflexion angle (32° to 48°) after 16.5 months. Additionally, Di Nallo et al. [67] conducted a retrospective multicenter cohort study among 28 patients (30 feet) who underwent arthroscopic cheilectomy. After an average follow-up of 4 years, 97% of patients were satisfied, with notable improvements in dorsiflexion angle (42° to 46°) and AOFAS score (59 to 84).

Based on our experience, we do not believe that arthroscopic cheilectomy is superior to open cheilectomy because of the following reasons. First, open cheilectomy can relieve the tightness and adhesions of the joint capsule by opening it, but this is not sufficiently done in arthroscopic cheilectomy. Second, the bleeding that occurs due to spur resection should also be considered. This can be sufficiently drained through the large wound in open surgery but not in the small wound in arthroscopic surgery, thereby increasing the possibility of intraarticular adhesions due to hematoma. Lastly, the arthroscopic water can cause persistent edema, resulting in difficulties in early postoperative rehabilitation and an increased possibility of intraarticular adhesions. Therefore, in cheilectomy, it is important to note that simply reducing the wound size does not necessarily lead to better treatment outcomes.

9. Arthroscopic Cochrane Procedure

Considering the aforementioned issues on cheilectomy, arthroscopy in hallux rigidus would better suit for the observation and treatment of the plantar side of the joint rather than for cheilectomy. For example, arthroscopic observation and treatment of the tightness around the sesamoid bones can help elucidate the pathology of the hallux rigidus. Furthermore, the arthroscopic Cochrane procedure holds potential, although only one technical note has been published regarding this procedure without reporting clinical outcomes. [69] One concern regarding the Cochrane procedure is the postoperative risk of developing a cock-up deformity due to division of the FHB tendon. However, the development of a postoperative hallux deformity is unlikely due to the degenerative changes and limited range of motion of the first MTP joint. [69,70]

10. Conclusions

In 1927, Cochrane noticed that the elastic resistance in hallux dorsiflexion persisted even after cheilectomy or resection arthroplasty. In response, the Cochrane procedure was devised to divide the shortened soft tissue beneath the hallux MTP joint using a plantar approach, resulting in favorable outcomes. This surgical procedure was able to directly address the underlying etiology of hallux rigidus. However, the current surgical treatments for hallux rigidus have failed to live up to this high standard. This review article discussed surgeries for hallux rigidus based on its etiology. When the sesamoid bones become immobile due to shortened plantar tissues, the center of rotation of the proximal phalanx shifts to the base of the hallux MTP joint, resulting in dorsal impingement. This impingement mechanism is supported by pathological studies of the articular cartilage of the MTP joint. Meanwhile, some have reported that the metatarsal bone is elevated in advanced hallux rigidus but not in its early stages, which could be explained by a windlass mechanism and shortening of the FHB tendon. Metatarsal decompression osteotomy, which was initially considered a treatment for the hallux primus elevatus and long metatarsals, was found to be effective across all grades of hallux rigidus. This surgery reduces compressive pressure on the dorsal articular surface by lowering the metatarsal head and loosening the plantar soft tissue. However, cheilectomy is a joint-destructive surgery for early-stage hallux rigidus that is associated with poor outcomes, with a high rate of arthritic progression and subsequent reoperation, including arthrodesis. Therefore, it is questionable whether cheilectomy should be regarded as the gold standard for early-stage hallux rigidus. Similarly, arthroscopic cheilectomy yielded comparable results to open cheilectomy. Considering the issues of cheilectomy, the use of arthroscopy for hallux rigidus may instead be more meaningful for elucidating its intraarticular pathogenesis and for arthroscopic Cochran’s surgery.

Author Contributions

Kenichiro Nakajima is the only author and performed everything regarding this research.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Elsevier Language Editing Services and Enago (

https://www.enago.jp) for reviewing the English.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AOFAS |

The American Orthopedic Foot & Ankle Society |

| FHB |

Flexor hallucis brevis |

| FHL |

Flexor hallucis longus |

MOXFQ

MTP

VAS |

The Manchester-Oxford Foot and Ankle Questionnaire

Metatarsophalangeal

Visual analog scale |

References

- Cochrane, W.A. AN OPERATION FOR HALLUX RIGIDUS. BMJ 1927, 1, 1095–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camasta, C.A. HALLUX LIMITUS AND HALLUX RIGIDUS. Clin. Podiatr. Med. Surg. 1996, 13, 423–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bingold, A.C.; Collins, D.H. HALLUX RIGIDUS. J. Bone Jt. Surgery. Br. Vol. [CrossRef]

- McMaster, M. The pathogenesis of hallux rigidus. J. Bone Jt. Surgery. Br. Vol. 87. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, K. Arthroscopy of the First Metatarsophalangeal Joint. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2018, 57, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shereff, M.J.; Bejjani, F.J.; Kummer, F.J. Kinematics of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1986, 68, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavin, R.; Halpin, T.; O’sullivan, R.; FitzPatrick, D.; Ivankovic, A.; Stephens, M.M. A finite-element analysis study of the metatarsophalangeal joint of the hallux rigidus. J. Bone Jt. Surgery. Br. Vol. 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, E. The windlass mechanism of the foot. A mechanical model to explain pathology. J. Am. Podiatr. Med Assoc. 2000, 90, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dananberg, H. Functional hallux limitus and its relationship to gait efficiency. J. Am. Podiatr. Med Assoc. 1986, 76, 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dananberg, H. Gait style as an etiology to chronic postural pain. Part I. Functional hallux limitus. J. Am. Podiatr. Med Assoc. 1993, 83, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maceira, E.; Monteagudo, M. Functional Hallux Rigidus and the Achilles-Calcaneus-Plantar System. Foot Ankle Clin. 2014, 19, 669–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamus, J.; Shamus, E.; Gugel, R.N.; Brucker, B.S.; Skaruppa, C. The Effect of Sesamoid Mobilization, Flexor Hallucis Strengthening, and Gait Training on Reducing Pain and Restoring Function in Individuals With Hallux Limitus: A Clinical Trial. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2004, 34, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, G.A.; Park, Y.-W.; Myerson, M.S. Role of Metatarsus Primus Elevatus in the Pathogenesis of Hallux Rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 1999, 20, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, M.J.; Shurnas, P.S. Hallux Rigidus: Demographics, Etiology, and Radiographic Assessment. Foot Ankle Int. 2003, 24, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shurnas, P.S. Hallux Rigidus: Etiology, Biomechanics, and Nonoperative Treatment. Foot Ankle Clin. 2009, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O Meyer, J.; Nishon, L.R.; Weiss, L.; Docks, G. Metatarsus primus elevatus and the etiology of hallux rigidus. . 1987, 26, 237–41. [Google Scholar]

- Roukis, T.S. Metatarsus Primus Elevatus in Hallux Rigidus. J. Am. Podiatr. Med Assoc. 2005, 95, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.T.; Sanders, A.E.; DaCunha, R.J.; Cody, E.A.; Sofka, C.M.; Nguyen, J.; Deland, J.T.; Ellis, S.J. Assessment of Various Measurement Methods to Assess First Metatarsal Elevation in Hallux Rigidus. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwander, H.; Alkhatatba, M.; Lerch, T.; Schmaranzer, F.; Krause, F.G. Evaluation of Radiographic Features Including Metatarsus Primus Elevatus in Hallux Rigidus. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2022, 61, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsonne, H. Hallux Rigidus and Its Treatment. Acta Orthop. 1930, 1, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgonis, T.; Jolly, G.P.; Garbalosa, J.C.; Cindric, T.; Godhania, V.; York, S. The Value of Radiographic Parameters in the Surgical Treatment of Hallux Rigidus. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2005, 44, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, A.; Viladot, R.; Giné, J.; Alvarez, F. The importance of the length of the first metatarsal and the proximal phalanx of hallux in the etiopathogeny of the hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle Surg. 2009, 15, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronconi, P.; Monachino, P.; Baleanu, P.; Favilli, G. Distal oblique osteotomy of the first metatarsal for the correction of hallux limitus and rigidus deformity. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2000, 39, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, J.V.; Garrett, P.P.; Jordan, M.J.; Reilly, C.H. The modified Hohmann osteotomy: An alternative joint salvage procedure for hallux rigidus. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2004, 43, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malerba, F.; Milani, R.; Sartorelli, E.; Haddo, O. Distal Oblique First Metatarsal Osteotomy in Grade 3 Hallux Rigidus: A Long-Term Followup. Foot Ankle Int. 2008, 29, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloff, L.M.; Jhala-Patel, G. A Retrospective Analysis of Joint Salvage Procedures for Grades III and IV Hallux Rigidus. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2008, 47, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceccarini, P.; Ceccarini, A.; Rinonapoli, G.; Caraffa, A. Outcome of Distal First Metatarsal Osteotomy Shortening in Hallux Rigidus Grades II and III. Foot Ankle Int. 2015, 36, 1469–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slullitel, G.; López, V.; Seletti, M.; Calvi, J.P.; Bartolucci, C.; Pinton, G. Joint Preserving Procedure for Moderate Hallux Rigidus: Does the Metatarsal Index Really Matter? J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2016, 55, 1143–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voegeli, A.V.; Marcellini, L.; Sodano, L.; Perice, R.V. Clinical and radiological outcomes after distal oblique osteotomy for the treatment of stage II hallux rigidus: Mid-term results. Foot Ankle Surg. 2017, 23, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slullitel, G.; López, V.; Calvi, J.P.; D’ambrosi, R.; Usuelli, F.G. Youngswick osteotomy for treatment of moderate hallux rigidus: Thirteen years without arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Surg. 2020, 26, 890–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derner, R.; Goss, K.; Postowski, H.N.; Parsley, N. A Plantarflexory-Shortening Osteotomy for Hallux Rigidus: A Retrospective Analysis. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2005, 44, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngswick, F.D. Modifications of the Austin bunionectomy for treatment of metatarsus primus elevatus associated with hallux limitus. . 1982, 21, 114–6. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, K. Sliding Oblique Metatarsal Osteotomy Fixated With a K-Wire Without Cheilectomy for Hallux Rigidus. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2022, 61, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saur, M.; Hernandez, J.L.Y.; Barouk, P.; Bejarano-Pineda, L.; Maynou, C.; Laffenetre, O. Average 4-Year Outcomes of Distal Oblique First Metatarsal Osteotomy for Stage 1 to 3 Hallux Rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 2021, 43, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, K. Sliding Oblique Metatarsal Osteotomy Fixated With K-Wires Without Cheilectomy for All Grades of Hallux Rigidus: A Case Series of 76 Patients. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilmartin, T.E. Phalangeal osteotomy versus first metatarsal decompression osteotomy for the surgical treatment of hallux rigidus: A prospective study of age-matched and condition-matched patients. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2005, 44, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viladot, A.; Sodano, L.; Marcellini, L.; Zamperetti, M.; Hernandez, E.S.; Perice, R.V. Youngswick–Austin versus distal oblique osteotomy for the treatment of Hallux Rigidus. Foot 2017, 32, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, N.R.; Kadakia, A.R. Surgical Management of Hallux Rigidus: Cheilectomy and Osteotomy (Phalanx and Metatarsal). Foot Ankle Clin. 2009, 14, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammit, G.V.; Menz, H.B.; Munteanu, S.E.; Landorf, K.B. Plantar pressure distribution in older people with osteoarthritis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint (hallux limitus/rigidus). J. Orthop. Res. 2008, 26, 1665–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, A.R.; Tinley, P.; Cole, J.H.; Alan, R. Bryant, PhD, MSc(Pod)*, Paul Tinley, PhD†, and Joan H. Cole, PhD‡ *Private practice, Subiaco, Western Australia, Australia. †Department of Podiatry, Charles Sturt University, Albury-Wodonga, New South Wales, Australia. ‡School of Physiotherapy, Cu; Pod), M.; D, P. Plantar Pressure and Joint Motion After the Youngswick Procedure for Hallux Limitus. J. Am. Podiatr. Med Assoc. 2004, 94, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blyth, M.; Mackay, D.; Kinninmonth, A. Dorsal wedge osteotomy in the treatment of hallux rigidus. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 1998, 37, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, B.-K.; Park, K.-J.; Park, J.-K.; SooHoo, N.F. Outcomes of the Distal Metatarsal Dorsiflexion Osteotomy for Advanced Hallux Rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 2017, 38, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, B.-K.; Park, K.-J.; Park, J.-K.; SooHoo, N.F. Outcomes of the Distal Metatarsal Dorsiflexion Osteotomy for Advanced Hallux Rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 2017, 38, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Murphy, G.A. Treatment of Hallux Rigidus with Cheilectomy Using a Dorsolateral Approach. Foot Ankle Int. 2009, 30, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattrup, S.J.; Johnson, K.A. Subjective results of hallux rigidus following treatment with cheilectomy. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1988, (226), 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, T.; Fawzy, E.; Dinah, F.; Palmer, S. Prospective Assessment of Dorsal Cheilectomy for Hallux Rigidus Using a Patient-reported Outcome Score. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2010, 49, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roukis, T.S. The Need for Surgical Revision After Isolated Cheilectomy for Hallux Rigidus: A Systematic Review. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2010, 49, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidon, E.; Rogero, R.; Bell, T.; McDonald, E.; Shakked, R.J.; Fuchs, D.; Daniel, J.N.; Pedowitz, D.I.; Raikin, S.M. Long-term Follow-up of Cheilectomy for Treatment of Hallux Rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 2019, 40, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teoh, K.H.; Tan, W.T.; Atiyah, Z.; Ahmad, A.; Tanaka, H.; Hariharan, K. Clinical Outcomes Following Minimally Invasive Dorsal Cheilectomy for Hallux Rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 2018, 40, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulier, T.; Steenwerckx, A.; Thienpont, E.; Sioen, W.; Hoore, K.D.; Peeraer, L.; Dereymaeker, G. Results After Cheilectomy in Athletes with Hallux Rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 1999, 20, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easley, M.E.; Davis, W.H.; Anderson, R.B. Intermediate to Long-term Follow-up of Medial-approach Dorsal Cheilectomy for Hallux Rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 1999, 20, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson, M. Pain After Cheilectomy of the First Metatarsophalangeal Joint. Foot Ankle Clin. 2014, 19, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, R.A.; Clanton, T.O. Hallux rigidus: treatment by cheilectomy. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1988, 70, 400–406 PMID: 3126190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughlin, M.J.; Shurnas, P.S. Hallux Rigidus. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2004, 86, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, W.A.; Brage, M.E. The Effects of Cheilectomy on Dorsiflexion of the First Metatarsophalangeal Joint. Foot Ankle Int. 1997, 18, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, B.; Stern, A.L.; Weinraub, G. Rate of Revision After Cheilectomy Versus Decompression Osteotomy in Early-Stage Hallux Rigidus. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2017, 56, 586–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geldwert, J.J.; Rock, G.D.; McGrath, M.P.; E Mancuso, J. Cheilectomy: still a useful technique for grade I and grade II hallux limitus/rigidus. . 1992, 31, 154–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, M.; Chana, G. Arthroscopic cheilectomy for hallux rigidus. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 1998, 14, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siclari, A.; Piras, M. Hallux Metatarsophalangeal Arthroscopy. Foot Ankle Clin. 2015, 20, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, R.; Perera, A. Open, Arthroscopic, and Percutaneous Cheilectomy for Hallux Rigidus. Foot Ankle Clin. 2015, 20, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K.J. Hallux Metatarsophalangeal (MTP) Joint Arthroscopy for Hallux Rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 2014, 36, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levaj, I.; Knežević, I.; Dimnjaković, D.; Smoljanović, T.; Bojanić, I. First Metatarsophalangeal Joint Arthroscopy of 36 Consecutive Cases. Acta Chir. Orthop. et Traumatol. Cechoslov. 2021, 88, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K.J. Hallux Metatarsophalangeal (MTP) Joint Arthroscopy for Hallux Rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 2014, 36, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, R.L.; Gonzalez, T.A.; Peterson, A.B.; Kaplan, J. Minimally Invasive Dorsal Cheilectomy and Hallux Metatarsal Phalangeal Joint Arthroscopy for the Treatment of Hallux Rigidus. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D.J.; Chen, J.S.; Colasanti, C.A.; Dankert, J.F.; Kanakamedala, A.; Hurley, E.T.; Mercer, N.P.; Stone, J.W.; Kennedy, J.G. Needle Arthroscopy Cheilectomy for Hallux Rigidus in the Office Setting. Arthrosc. Tech. 2022, 11, e385–e390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, P.M.; Gallagher, J.; Curatolo, C.; Pettit, D.; Martin, K.D. Dorsal Cheilectomy Using Great Toe Metatarsophalangeal Joint Arthroscopy for the Treatment of Hallux Rigidus. Arthrosc. Tech. 2023, 12, e603–e608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nallo, M.; Lebecque, J.; Hernandez, J.L.Y.; Laffenetre, O. Percutaneous arthroscopically assisted cheilectomy combined to percutaneous proximal phalanx osteotomy in hallux rigidus: Clinical and radiological outcomes in 30 feet at a 48-month follow-up. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2023, 110, 103710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paczesny, Ł.M.; Kruczyński, J. Ultrasound-guided arthroscopic management of hallux rigidus. Videosurgery Other Miniinvasive Tech. 2016, 11, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lui, T.H.; Slocum, A.M.Y.; Li, C.C.H.; Kumamoto, W. Arthroscopic Dorsal Cheilectomy, Plantar Capsular Release, Flexor Hallucis Brevis Release, and Sesamoid Cheilectomy for Management of Early Stages of Hallux Rigidus. Arthrosc. Tech. 2024, 14, 103198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagoe, M.; Brown, H.A.; Rees, S.M. Total Sesamoidectomy for Painful Hallux Rigidus: A Medium-Term Outcome Study. Foot Ankle Int. 2009, 30, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).