1. Introduction

In the contemporary landscape, both policymakers in

developing and modern industrial countries encounter formidable challenges in

achieving sustainable development, especially in the context of the

multifaceted challenges posed by globalization. These challenges encompass the

environmental, financial, technical, economic, and social dimensions within the

framework of the global international system. This study aims to elucidate the

significance of digital technology and its pivotal role in promoting economic

and social equality, ultimately contributing to growth and sustainable

development.

Despite the increasing relevance of digitization,

the economic literature has yet to adequately demonstrate its role in

harnessing both economic and social globalization to propel the economies of

developing nations and expedite their economic advancement. Consequently, the

present research investigates the impact of globalization—both economic and

social—on economic growth while establishing a connection to the role that

digitization plays in this dynamic. Utilizing empirical research data from the

Saudi economy—an illustrative example of a developing country undergoing

significant structural transformations and accelerated economic and social

growth—this study aspires to examine the causal and cointegration relationships

among socioeconomic globalization, digitalization, and their collective impact

on economic growth. The analysis draws evidence from Saudi Arabia, particularly

focusing on the period from 1990 to 2022.

Saudi Arabia is endowed with abundant primary

energy resources, including crude oil, coal, and natural gas. Notably,

petroleum products account for approximately 90 percent of the country's

exports, with the oil industry contributing around 45 percent to the gross

domestic product (GDP) (Mahalik et al., 2017). The industrial and manufacturing

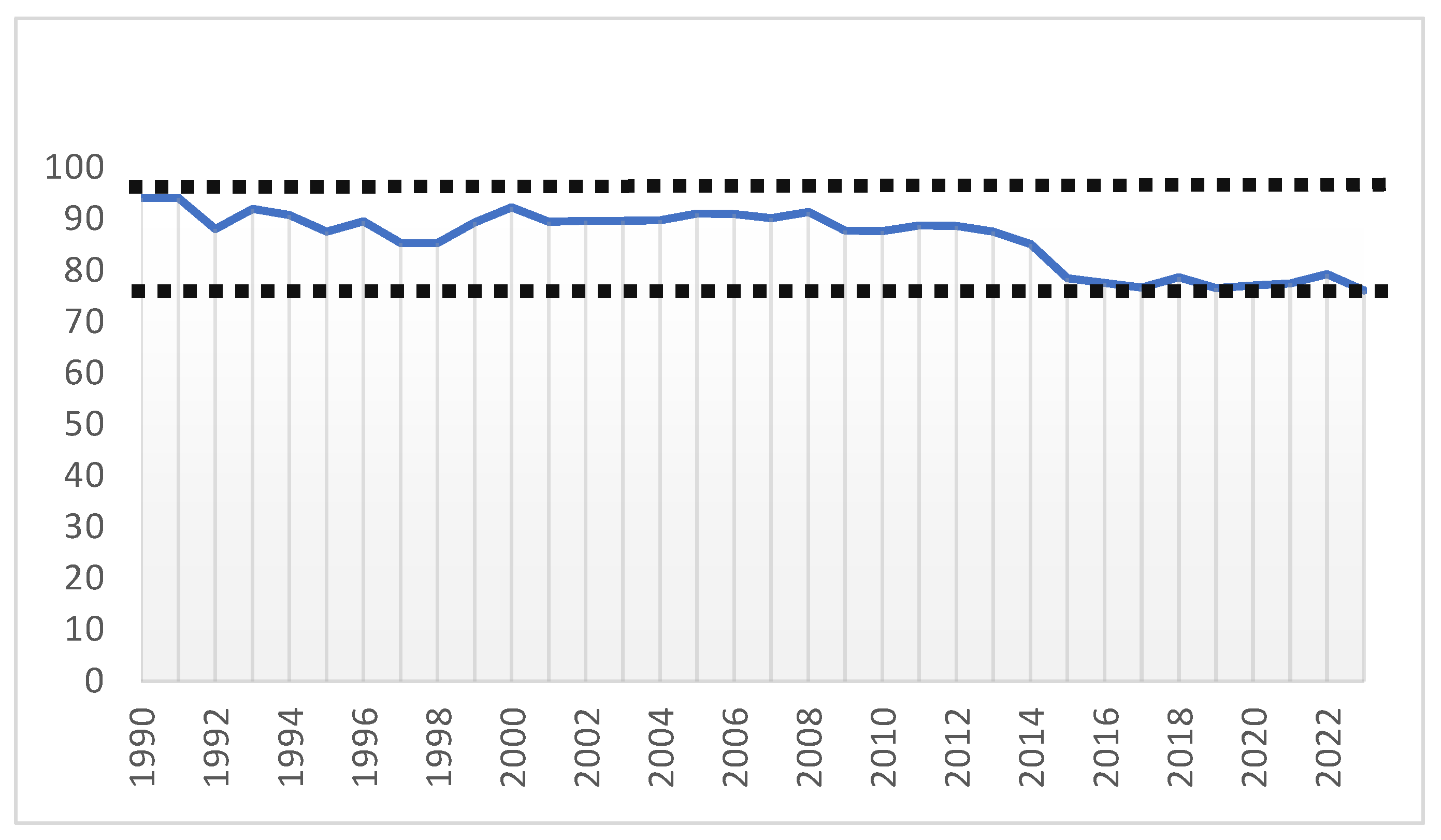

sectors collectively represent 52 percent of Saudi Arabia's GDP. As depicted in

Figure 1, the proportion of crude oil in

total Saudi oil exports has decreased from 95 percent in 1990 to roughly 75

percent in 2022, highlighting a trend toward diversification that has become

increasingly apparent over the past decade.

Despite its resource wealth, Saudi Arabia has

encountered economic challenges stemming from persistent declines in oil prices

in recent decades, resulting in diminished oil revenues. To alleviate its

dependency on the oil sector, the government has initiated strategies aimed at

diversifying the economy, recognizing the essential role of the financial

sector in fostering economic growth. These measures encompass the promotion of

the banking sector, the enhancement of financial markets, and the development

of the insurance sector. In alignment with this economic diversification

strategy, the government has introduced Vision 2030, underscoring the

significance of enhanced globalization. This global engagement not only

facilitates financial development but also nurtures sustainable economic growth

by bolstering the quality of the country's institutions (Shahbaz et al., 2019).

As a widespread phenomenon, globalization exerts a

profound influence on global socio-economic and political factors, facilitating

the integration of economies through trade and foreign direct investment (FDI).

However, the process of globalization is not devoid of challenges. In pursuit

of globalization, multinational corporations may compromise environmental

standards during the establishment of factories in host countries (Shahbaz et

al., 18). The structural changes in industries necessitated by globalization to

meet international demand often require additional resources, posing risks of

environmental degradation. Moreover, globalization, facilitated by trade

liberalization, promotes the free exchange of goods among nations, leading to

increased production and consumption of goods and energy (Kandil et al., 2015).

The influx of foreign firms investing in host

countries represents another dimension of globalization. Recent technological

advancements and societal trends favoring digitalization have engendered

significant global transformations. This paradigm shift necessitates

substantial adjustments. The global economy has experienced considerable

changes within the socioeconomic-educational system, especially in higher

education. These transformations include alterations in educational standards,

quality, decentralization, and the emergence of virtual and independent

learning (Mohamed Hashim et al., 2022). The strategic focus has shifted toward

students rather than exclusively on technology and learning opportunities. The

integration of digital devices and transformations has positively influenced

the learning environment, yielding promising outcomes over time (Hanelt et al.,

2021).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a comprehensive literature

background. Section 3 presents the

empirical studies and methodology adopted in this study. Section 4 highlights the test specification,

proposed method, results discussion, and robustness of our method. Finally,

section 5 provides concluding remarks and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Background

The Solow model (1957) posits that continual

improvements in living standards can be attributed solely to technological

progress. Subsequent growth theories, as exemplified by Sala-i-Martin &

Barro, (1995), underscore the significance of technological advancement in

economic growth. Departing from the Solow growth model, these newer theories

seek to internalize technological progress. In contrast to the Solow model,

which treats technology as exogenous, emerging growth models aim to endogenize

technological progress. Moreover, it is argued that the pace of modern

technological advancements not only influences economic growth but also exerts

wide-ranging effects on life expectancy, social levels, health outcomes,

poverty rates, and literacy, as asserted by Grossman and Helpman (1993).

Scholars such as Oliner and Sichel (1994) contend that innovation and the

enhancement of existing products act as catalysts for growth. They utilize the

neoclassical framework and incorporate information technology into the growth

model, demonstrating that the growth rate of output hinges not only on the

stock of computing equipment but also on factors including capital, labor, and

multifactor productivity. The fundamental concept behind digitization revolves

around leveraging information and communication technology (ICT) facilities to

access global resources for societal benefit. Embracing digitization is

essential in the current era to promote environmental health and safety.

Numerous organizations are actively engaged in digitizing their materials,

recognizing the enduring value of such resources for educational purposes.

Furthermore, digitization enhances the reputation of institutions, enabling

global users to be aware of institutional collections and utilize these

resources from remote locations.

Over the past three decades, the global advancement

of ICT has garnered considerable attention from economists and researchers.

Numerous studies have explored the impact of globalization and ICT diffusion on

the economic growth of both developed and developing economies. It is widely

acknowledged in the literature that globalization and ICT play a pivotal role

in fostering economic prosperity in both contexts, as highlighted by Arendt

(2015). The impacts of globalization on economic development are varied for

both developed and developing countries, yielding both positive and, at times,

negative outcomes. Notably, the benefits of globalization are not equally

distributed across countries, sectors, and individuals within the same country.

A wide range of theoretical and empirical studies investigate globalization and

its socioeconomic impacts, justifying this dual effect. Many studies confirm

the crucial role of globalization in the economy as a whole (Bhagwati, 2004;

Grossman and Helpman, 1993; Crafts, 2004; Stiglitz, 2002, 2006; Dreher, 2006;

Rahman, 2020; Shahbaz et al., 2019), among others. Bhagwati (2004), a

world-renowned economist, posits that globalization, if properly regulated, is

one of the most influential forces for social good globally. His book, *In

Defense of Globalization*, addresses criticisms related to the social effects

of economic globalization. The issues discussed include the effects on women's

rights and equality, poverty in underdeveloped nations, democracy, and the

preservation of both dominant and indigenous cultures, as well as environmental

concerns. To counter accusations that globalization leads to cultural

dominance, he argues that internationalization contributes to solutions rather

than being part of the problem. However, Stiglitz (2002) contends that the

influence of globalization depends on a country's preparedness to capitalize on

the opportunities offered by globalization to promote economic growth. Bhagwati

(2004) further asserts that, under the right conditions, globalization is

indeed the most potent force for social good in the modern world. He

illustrates that globalization frequently resolves many issues in developing

countries by rapidly decreasing child labor and raising literacy rates, as

affluent parents choose to send their children to school instead of work.

Furthermore, globalization advances women's rights globally and demonstrates

that economic expansion need not inevitably lead to higher pollution levels

when combined with sensible environmental protections. Bhagwati (2004)

persuasively argues that globalization is part of the solution, not the cause

of the issue.

Stiglitz (2006) illustrates in *Making Globalization Work* that economic globalization transcends political considerations and moral sensitivity to ensure a just and sustainable world. He emphasizes that the real work required of all countries to achieve this goal is to understand and utilize globalization correctly. Numerous influential studies assert that globalization can significantly accelerate economic growth, provided that a threshold level of institutional quality, including international openness, equal access to information in financial markets, and a favorable composition of capital inflows, is present in countries importing capital (Kose et al., 2009; Stiglitz, 2002; Wei, 2006; Daude and Stein, 2007; Uusitalo and Lavikka, 2021). The lack of empirical studies validating these propositions in the aforementioned seminal works prompts an examination of the roles of quality of governance (QoG) and foreign direct investment (FDI) as key factors influencing the impact of globalization on economic growth.

Within the economics profession, it is widely accepted that fostering international trade accelerates economic growth (Crafts, 2004; Dollar and Kraay, 2004). The rationale behind this belief varies depending on the growth theory considered. Specifically, neoclassical growth theory posits that openness facilitates a more efficient allocation of resources, thereby contributing to growth. Conversely, endogenous growth theory suggests that openness can stimulate growth through mechanisms such as the diffusion of technology, learning by doing, and the exploitation of scale economies. Shahbaz et al. (2019) affirm that the understanding of globalization is widespread when economies are tightly integrated, sharing social standards and political platforms. Additionally, Dreher (2006) asserts that globalization facilitates the opening up of economies, fostering growth and prosperity, thus suggesting potential benefits for national economic growth and development.

Hirst and Thompson (1996) provide a critical analysis of globalization and its implications. They examine the economic, political, and social dimensions of globalization and question its consequences for governance and the nation-state. They argue that globalization is not an all-encompassing, inevitable force but rather a complex and contested process. They challenge the prevailing view that globalization leads to the withering away of the nation-state, maintaining that the nation-state remains a significant actor in global affairs. Hirst and Thompson (1996) suggest that globalization should be understood as a set of interrelated processes that interact with political and social structures at various levels. They highlight the role of economic globalization in shaping the international economy, discussing the liberalization of trade and finance, the rise of multinational corporations, and the growth of global financial markets. They also address the impact of technological advancements, such as ICT, on global economic integration. Hirst and Thompson (1996) raise concerns about the consequences of globalization, arguing that it can lead to increased inequality within and between countries. They emphasize that global economic integration can exacerbate social and economic divisions, particularly in developing countries. They express apprehension regarding the potential erosion of democratic governance and the concentration of power in the hands of non-state actors, such as multinational corporations and international financial institutions.

Moreover, the authors critique the notion of a borderless world, arguing for the continued significance of borders and national institutions. They contend that the nation-state remains a crucial source of political authority and that democratic governance and accountability should be maintained at the national level. Hirst and Thompson (1996) propose the need for new forms of global governance to address the challenges posed by globalization, emphasizing the importance of democratic accountability, transparency, and social regulation in shaping global economic processes. They advocate for the establishment of international institutions capable of effectively addressing global issues while respecting democratic principles. Overall, their perspective on globalization challenges the prevailing narratives of an inevitable and all-encompassing force, emphasizing the complexities and contradictions of globalization and advocating for a more nuanced understanding of its implications for governance and societal well-being.

In fact, an increase in economic globalization may not contribute to economic development and growth in countries with limited economic opportunities. Consequently, these nations might not fully benefit from globalization in the absence of necessary prerequisites. Many scholars emphasize the structural and socioeconomic factors shaping the relationship between globalization and economic development, particularly economic growth. Consequently, globalization is often perceived as having a positive effect on economic growth, assuming a certain level of quality in structural and socioeconomic indicators across countries. Variation in a country's growth performance is attributed to policy complementarities that play a crucial role in enhancing economic growth. Policy integrations must accompany trade openness to effectively boost economic growth, making them prerequisites for such growth. Financial liberalization shows a more significant impact on output in countries where institutional quality has improved (Omoke & Opuala-Charles, 2021). However, policy complementarities in each country impose constraints on the optimal design of growth strategies in nations resistant to reform and facing unfavorable initial conditions (Calderon and Fuentes, 2006). In this context, Chang et al. (2013) discovered that reforms in banking, governance, the labor market, infrastructure, and trade influence the nexus between globalization and growth in developing countries. Similarly, research by Gu and Dong (2011) asserts that financial development and financial integration are prerequisites for effective financial globalization. They found that without improvements in the financial system, globalization can lead to volatile growth in countries. The foundational study by Samimi and Jenatabadi (2014) suggests that economic globalization and a country's structural characteristics are interdependent and complementary. In alignment with this perspective, Sirgy et al. (2004) delve into the impact of globalization on life expectancy in developing countries, highlighting the pronounced challenges these nations face, particularly regarding health outcomes. While limited studies explore the effect of globalization on human health (e.g., Sirgy et al., 2004), the majority indicate various channels through which globalization may impact middle-income countries (Shahbaz et al., 2018; Audretsch et al., 2014). Evidence also suggests that countries with more adaptable labor markets experience structural changes that are more conducive to growth.

Globalization is broadly supported by key international organizations such as the World Bank (WB), International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Trade Organization (WTO), Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), which emphasize its positive impact on economic growth, global trade, and sustainable development for all countries.

The World Bank views globalization as a potent force for generating economic growth, reducing poverty, and improving living standards worldwide. It underscores the benefits of increased international trade, investment, and economic integration, as reflected in its publications, such as the "World Development Report" (World Bank, 2020), which focuses on globalization's role in promoting economic development and inclusive growth strategies.

Similarly, the IMF supports globalization and highlights its positive effects on global economic growth and development. The IMF advocates for policies that enhance international trade, investment, and financial integration to foster economic stability. Its reports, including the "World Economic Outlook" (IMF, 2021), often explore the benefits of trade liberalization and macroeconomic stability within a globalized framework.

UNCTAD emphasizes the development dimension of globalization, promoting inclusive and sustainable growth, particularly for developing nations. Its reports, like the "Trade and Development Report" (UNCTAD, 2022), talk about the pros and cons of globalization. They push for policies that work well together so that everyone can benefit, and they cover topics like fair trade and technology transfer.

The WTO champions principles of open trade, market access, and non-discrimination, promoting the reduction of trade barriers to facilitate global commerce. The WTO's annual "World Trade Report" (WTO, 2021) examines trade trends, the impact of trade policies, and the importance of rules-based trade governance, addressing challenges such as protectionism and the necessity for global cooperation.

Finally, the OECD perceives globalization as a catalyst for economic development, innovation, and productivity growth. It emphasizes the significance of open markets and cross-border collaboration in fostering economic integration. OECD reports, like the "OECD Economic Outlook" (OECD, 2022), look at how globalization affects many policy areas, such as trade and the environment. They also talk about problems like income inequality and the need for strategies for growth that benefit everyone.

According to Robertson (1992), globalization is not merely the spread of global economic forces, but a complex phenomenon encompassing economic, political, cultural, and social aspects. He highlights technology's role in facilitating globalization, emphasizing advances in transportation and communication technologies. Robertson (1992) asserts that globalization involves creating a shared awareness of global interconnectedness and interdependence. Baldwin (2018) provides a comprehensive analysis of information technology's impact on globalization and its implications for the global economy. Baldwin (2016) argues that the current phase of globalization, referred to as the second unbundling, differs from earlier phases, being driven by advances in ICT and leading to the fragmentation of service activities across borders. He also discusses potential consequences such as labor market polarization and rising income inequality.

Overall, Baldwin (2016) emphasizes information technology's role in driving globalization and reshaping economic interactions. The nature of the relationship between digitalization and globalization is complex and multidimensional, with both positive and negative implications. While digitalization enhances global connectivity and economic opportunities, it also exacerbates inequalities and raises governance challenges. In the digitally connected global economy, Manyika et al. (2016) highlighted how the complexities of globalization have changed, pointing out that the network of global economic connections is growing in complexity, breadth, and depth, as well as the growing cross-border data flows that now bind the global economy with the same dependability as the traditional movement of manufactured goods.

Digitalization has significantly influenced Saudi Arabia's socioeconomic landscape, driving economic growth, enhancing employment opportunities, and improving transparency (Neffati & Gouidar, 2019; Neffati & Jbir, 2024; Al-Sahli & Bardesi, 2024). The education sector, in particular, has experienced significant advancements, with digital tools revolutionizing learning behaviors and improving accessibility (Alaboudi & Alharbi, 2021). Moreover, the Vision 2030 initiative highlights the strategic importance of digitalization in diversifying Saudi Arabia’s economy, reducing oil dependency, and fostering innovation (Khan, 2019; Vision 2030 Report, 2021). However, this relationship between digitalization and globalization also presents challenges. While digitalization promotes connectivity and economic opportunities, it raises concerns about inequality, data privacy, security, and governance. Different levels of digital access and literacy can make socioeconomic differences worse. To close these gaps and make sure everyone has an equal chance to participate in the digital economy, policies are needed (Hilbert, 2016; Ragnedda & Muschert, 2013).

Research Gap

The relationship between digitalization and globalization is complex and multifaceted, offering both opportunities and challenges. Nations that effectively integrate digital technologies can leverage globalization's benefits while mitigating its adverse effects, as illustrated by Saudi Arabia’s experience in harnessing digitalization for sustainable growth and development.

In short, the Solow model is a starting point for theories of endogenous economic growth that emphasize the leading role of technological progress in economic growth and that digitalization and information and communication technologies have a significant impact on social and economic aspects. Globalization is a phenomenon with complex and dual effects, some positive and some negative, on economic development, and its benefits are distributed unevenly across regions and countries of the world.

Many factors influence the complex relationship between globalization and economic growth, including the quality of institutions, governmental structures, and foreign direct investment. Furthermore, there are diverse viewpoints on how globalization affects nation states and global governance, reflecting the multifaceted nature of this global phenomenon and its long-term consequences.

In the light of previous studies, we conclude that there are many areas that require further research, including the lack of empirical studies proving the validity of theoretical proposals on the roles of quality governance and FDI in shaping the impact of globalization on economic growth, especially in developing countries or specific industries. Perhaps the Saudi economy, which has undergone significant and accelerated transformations after the country's accession to the World Trade Organization in 2005, is one of the examples worth studying. In addition, there is a need for further exploration of the long-term effects of digitization technology on economic growth, social structures and environmental sustainability. In addition, while the importance of digitization is being discussed, there is a need to further explore the long-term effects of digital transformations on economic growth, social structures, and environmental sustainability.

3. Empirical Studies and Methodology

Several empirical studies have successfully employed the ARDL (Autoregressive Distributed Lag) model to ascertain both short-term and long-term dynamic relationships between study variables. Specifically, the ARDL model has been utilized across various disciplines to analyze long-term connections among variables. For instance, Pesaran, Shin, and Smith (2001) applied the ARDL approach to investigate the long-run relationship between inflation and money growth in the United States, providing critical insights into the stability of this long-term association. Similarly, Shahbaz et al. (2018) utilized the ARDL methodology to assess the long-term impact of financial development on stock market performance in emerging economies, revealing a positive and significant long-run relationship between these constructs. Furthermore, Banday and Aneja (2019) employed the ARDL model to explore the long-run dynamics between energy consumption (EC), economic growth as measured by GDP, and carbon dioxide emissions (CO2) in G7 countries. Their research elucidated the intricate long-run interactions among these variables. In addition, Pata et al. (2023) applied the ARDL model to examine the long-run effects of foreign direct investment (FDI) on trade in ASEAN countries, uncovering positive and significant long-run causal links between FDI and trade in the region. These studies underscore the versatile applications of the ARDL model in empirical research.

Conversely, the ARDL model is also adept at analyzing short-term dynamics among variables. For example, Kandil and Mirzaie (2016) utilized the ARDL framework to investigate the short-term effects of monetary policy on output in selected Middle Eastern and North African countries, focusing on how changes in interest rates and money supply influenced short-term output fluctuations. Similarly, Bahmani-Oskooee and Ratha (2015) explored the short-run causal relationships between exchange rate volatility and trade flows in the United States and Canada. Their findings illustrated the impact of exchange rate fluctuations on short-term trade dynamics. Additionally, Abdur Chowdhury and Mavrotas (2006) employed the ARDL model to assess the short-term effects of fiscal policy on economic growth in developing countries, examining how government spending, taxation, and public debt influenced short-term growth trajectories. Collectively, these instances highlight the adaptability of the ARDL model in scrutinizing short-term relationships across diverse fields of inquiry.

Based on the aforementioned studies and acknowledging the existence of time series that are not integrated in the same order, the ARDL model is chosen for this analysis. The prerequisite for employing the VAR model is that all series must be integrated of order 1, which does not apply to our series. The ARDL model, developed by Pesaran and Shin in 1998 (PS 1998) and further refined by Pesaran, Shin, and Smith in 2001 (PSS 2001), is particularly advantageous as it accommodates regression models with varying orders of integration, i.e., series I(0) and I(1). Moreover, it effectively captures both short-term and long-term dynamic relationships among the study variables through the bounds cointegration test, thus enhancing the precision of forecasts and informing government policy decisions. Consequently, this model aligns seamlessly with our research hypotheses.

Prior to estimating the ARDL model equation using the ordinary least squares (OLS) method, it is imperative to conduct the bounds cointegration test. Should our variables exhibit cointegration, we will refine our model by incorporating the long-term dynamic relationship via the Conditional Error Correction Model (CECM). Conversely, if the variables are not integrated, we will exclusively specify the ARDL model. The general ARDL (p, q) model is expressed as follows:

is a vector, and the variables contained in the matrix ()′ may be integrated of order 0, I(0), or integrated of order 1, I(1).

γ is the constant; i = 1, … ,k is the number of variables in the model.

δ and β are the coefficients of the variables.

p, q are the optimal orders of lags for the dependent and independent variables, respectively.

is the vector of error terms, also referred to as innovation or shocks.

3.1. The Empirical Model

To establish the right form of empirical models, we started with the traditional Cobb-Douglass production model, which uses only capital stock (K) and labor (L) to describe economic growth (Y) as follows:

we suppose the constant return to scale:

, and we apply the logarithm,

We suppose that

, production per capita, and

, capital intensity.

we apply log then we have

The most popular metric of growth is production per capita (expressed as the ratio between the quantity produced and the number of workers required for its production, i.e. the term Y/L), which rises when capital intensity rises, as measured by an increase in the K/L ratio.

If we introduce the variables according to the object of our study especially globalization variables (GI) and digital economic variable (DI) to the equation (1) and replace Yt by real gross domestic product per capita (GDPC) we obtain the general form of estimated equation as following:

3.2. Variables and Database Sources

In this paper we investigate the relationship between; socioeconomic globalization, digitalization and economic growth. Then We will validate this relation using equation (5) in the case of Saudi Arabia. The time series data used during the period spans from 1990 to 2022.

Table 1 below provides a summary of the definitions for each variable, and the sources from which they were extracted:

Our study focusses on the KOF Globalization Index which measures the economic, social and political dimensions of globalization (Dreher, (2006); Potrafke, (2015)) We use only the economic globalization index (EcGI), social globalization index (SoGI) as calculated by for all countries of the world. While for Digitalization index (DI) we use as a proxy the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) which calculate referring to the study of Olczyk and Kuc-Czarnecka (2022), this index was used as a suitable variable that characterizes the development level of the digital economy. Olczyk and Kuc-Czarnecka (2022) verify that DESI sub-indicators can be used to analyze the country’s digital transformation (Neffati and Jbir , 2024).

In the light of the above discussion relationship between economic growth (GDPC), socioeconomic globalization and digitalization will be studied as shown in the following equation (6):

Where,

GDPC; Gross Domestic Product per Capita,

; Capital Intensity

; Globalization index

; Social Globalization Index

; Economic Globalization index

; Digital Economy and Society Index, and

; Error terms

In order to use and analyze our time series, we will first check their stationarity over time, which is a crucial step in the study of time series.

3.3. Specification Tests

3.3.1. Stationarity Test

A time series is considered stationary when all its marginal and joint distributions do not change over time, meaning it does not contain a unit root. Let's consider the following equation:

With ∶ error term (i.i.d)

This series is considered stationary if ρ < 1. The null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis for each of the series will be: H0: ρ = 1: the series contains a unit root. Ha: ρ < 1: the series does not contain any unit root. Several stationarity tests, such as the Phillips-Perron (PP) test, the Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt, and Shin (KPSS) test, and the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test, can help us address these hypotheses. However, we will proceed with the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test in Eviews.

Based on the estimation of unit root test,

Table 2, all the studied variables are purely stationary into the first difference, or integrated at I(1). According to the result, we can perform the cointegration test and ARDL model to estimate the short- and long-term relationship. The ARDL model combines endogenous and exogenous variables.

As a necessary yet not sufficient condition, the ADF and PP tests are employed to identify unit root conditions. The results presented in

Table 2 indicate that all series exhibit nonstationary at the levels but become stationary at first differences (I(1)) at a significance level of 0.05. Furthermore, the PP test results confirm that all selected variables can be classified under the I(1) process.

Building on the outcomes from

Table 1, the next step involves proposing the Johansen rank with trace and maximum-Eigen-value test statistics to detect cointegration (Johansen, 1991).

3.3.2. Cointegration Test

The strong co-integration phenomenon was developed by Engle and Granger in 1987. Indeed, a regression derived from non-stationary time series can yield misleading correlation results, commonly referred to as "spurious correlation." Cointegration analysis allows us to distinguish regressions that have a plausible causal relationship.

Two non-stationary variables are said to be cointegrated if there is a long-term dynamic relationship between them. That is, if two variables are cointegrated of order I(1), their linear combination becomes I(0). Thus, even if they diverge in the short term, they eventually converge in the long term. One limitation of the Engle-Granger 1987 cointegration test is that it only applies to series integrated of order 1. Therefore, PS in 1998 (PS 1998) and PSS in 2001 (PSS 2001) developed the bounds cointegration test, which allows studying the short-term and long-term dynamic relationship of two variables integrated with different orders, for example, I(0) and I(1). In their respective studies, Mbarek et al. (2017, 2018), Saidi and Mbarek (2016), and Ngoma and Yang (2024) utilize cointegration estimation to explore the dynamic relationships between key economic variables over the short and long term. These estimations are essential in detecting long-run equilibrium relationships amidst short-run fluctuations, allowing the authors to assess how different economic factors co-move and influence each other over time. For instance, Mbarek et al. (2017) focus on the relationship between energy consumption and economic growth, while Saidi and Mbarek (2016) investigate environmental quality's impact on economic development.

Cointegration assumptions:

Ho: absence of cointegration relationship among the study variables.

Ha: There is one or more cointegration relationships among the study variables.

The co-integration results, as shown in

Table 3, reveal the presence of two co-integration equations at the 0.05 significance level. This implies a significant long-term relationship between socioeconomic globalization, digitalization, and economic growth in Saudi Arabia. In the following phase, we will use the ARDL model, with support from FMOLS and DOLS, to investigate both the long- and short-run causal-links between all variables (dependent and independent). While theoretically, running a VECM is possible when variables are co-integrated in the first-level to determine causality between them, it is not sufficient.