Submitted:

14 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

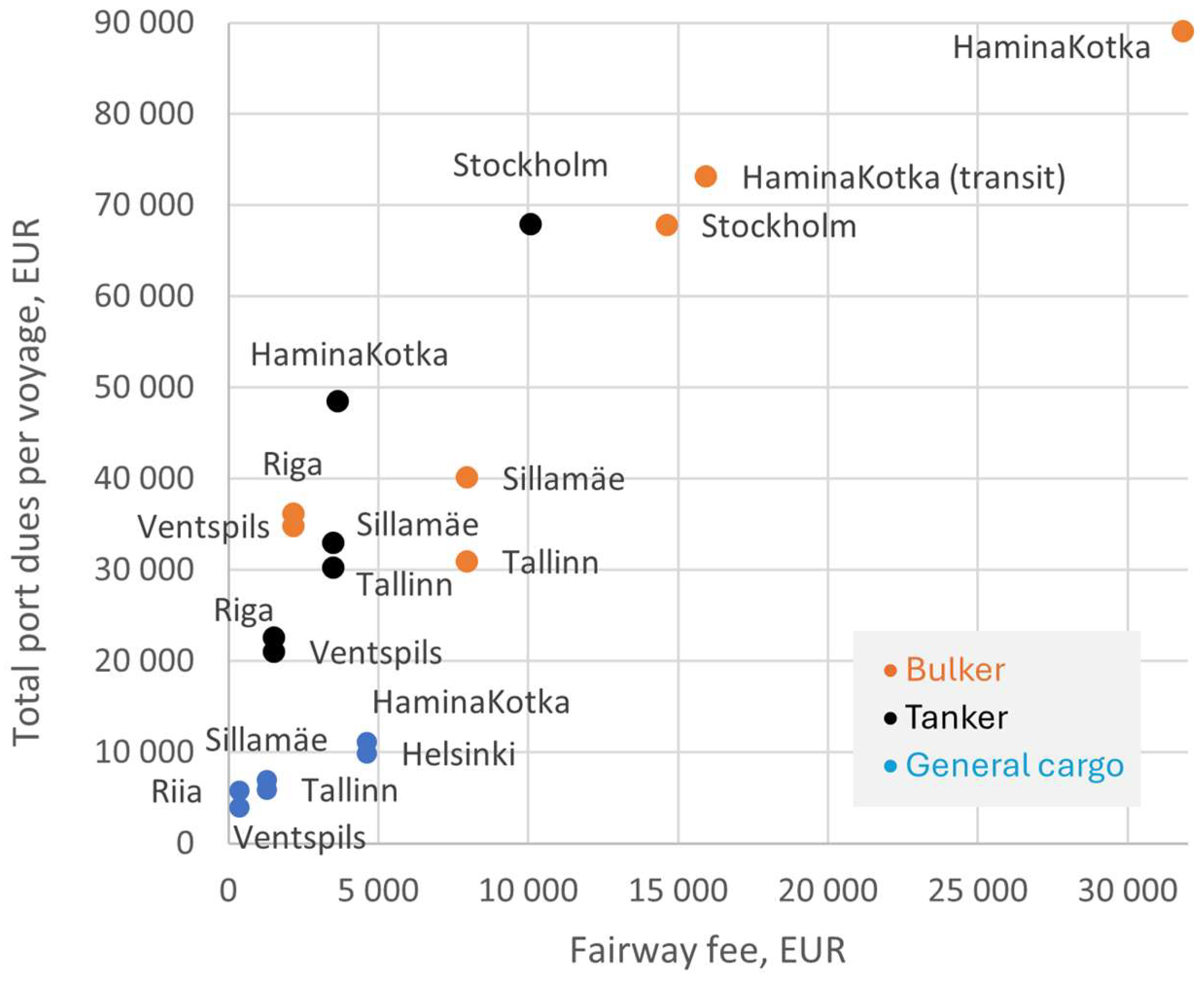

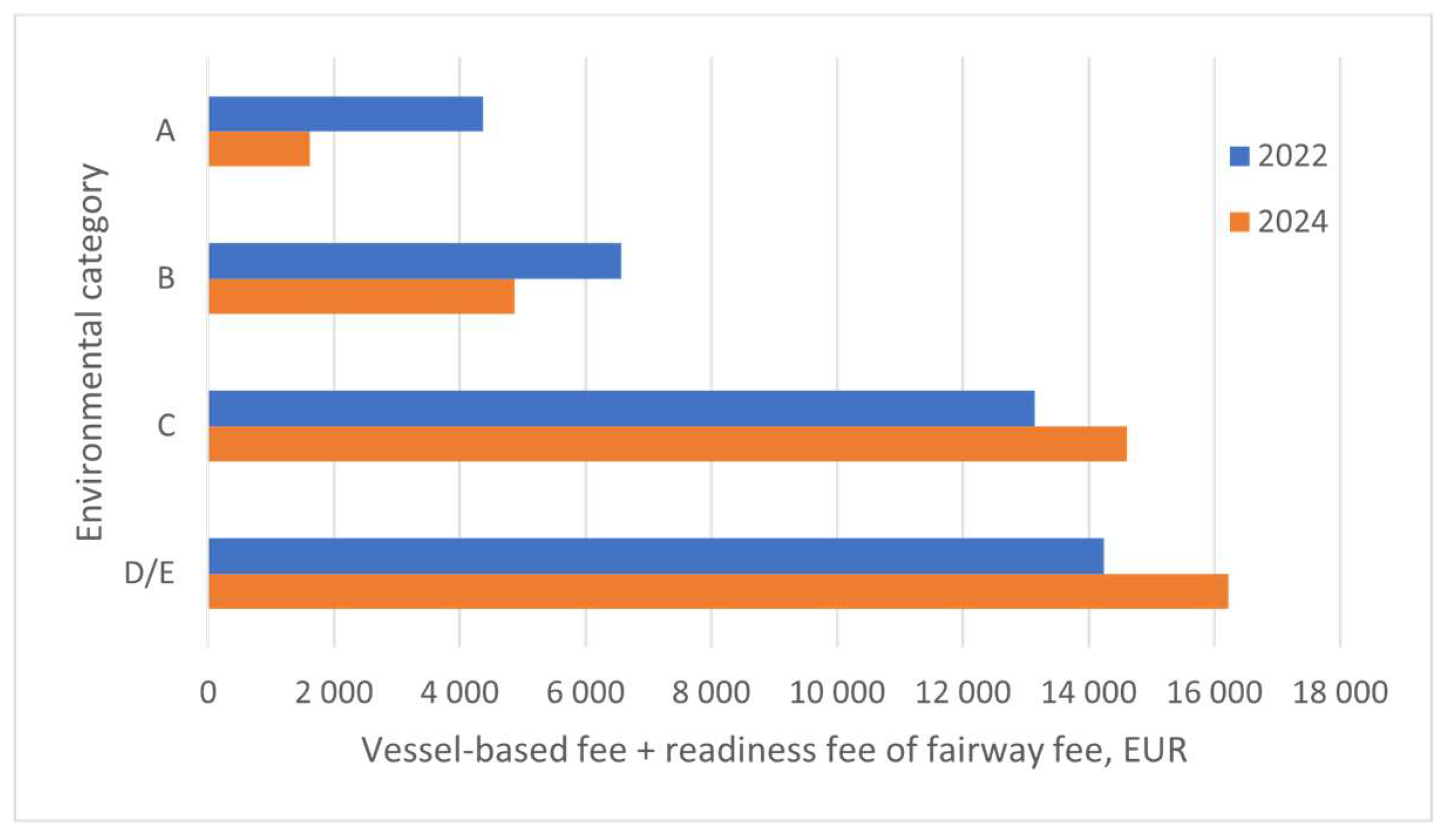

Ports and waterways are integral components of the maritime transport system, facilitating global trade and logistics. Governments, ports, and service providers levy charges on vessels for the use of fairways, port access, and associated services. This study analyzes the port and fairway fee strategies of seven major Baltic Sea ports across four countries: Estonia (Tallinn and Sillamäe), Latvia (Riga and Ventspils), Finland (Helsinki and HaminaKotka), and Sweden (Stockholm). The analysis evaluates the application of general port pricing principles in these ports' strategies. The findings reveal that port fees are predominantly value-based, with tariff rates varying by vessel type and cargo. However, no uniform structure exists for fairway fees. Notably, incorporating environmental components into fairway fee calculations emerges as a promising mechanism to promote sustainability in maritime transport. By incentivizing the adoption of environmentally friendly vessels through differentiated fee structures, ports and policymakers can accelerate the transition toward greener shipping practices. This study highlights the role of economic instruments in advancing environmental objectives and emphasizes the need for a harmonized, sustainability-driven approach to fairway and port pricing in the Baltic Sea region.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What are the port and fairway fees in the case countries with selected vessels?

- How are the port and fairway fees structured in the case countries?

- Is there a general structure of the port and fairway fees used by the countries?

2. Literature Review: Basis of the Port Fees

2.1. Port Pricing Policies

- Cost-based – based on the cost of products or services plus adding profit margin.

- Performance-based – based on the utilization of the facility above or below the optimum level with the objective of efficient use of the facility, e.g. berth utilisation.

- Value-based pricing – products and services are priced on their perceived value to the customer. Cargo groups with different price elasticities are charged differently based on the value of service. The strategy allows the port to promote specific market segments.

- Competition-based pricing – based on competitors expected or observed price levels

- Strategic port pricing or market-based pricing – expected market demand is the base for port tariffs.

2.2. Components of Port Fees and Charges

3. Port Pricing in Case Ports

3.1. Structure of the Port Fees

- type of vessel;

- regular/repeat visit or single visit within a certain period (may be more than one year);

- usually GT (Estonia, Sweden, Latvia) or NT (Finland, Sweden) of the vessels. In the case of fairway fees, the ice-class;

- per call, per operation, per time unit, per volume of service provided;

- in the case of a cargo charge, either weight, volume or unit;

- in the case of a passenger charge, the passenger (age restriction and other distinctions may apply);

- the environmental performance of the vessel;

- the purpose of the port call – loading, unloading, bunkering, etc.

- a number of surcharges and discounts have been introduced to port fees. These usually apply to general charges. Examples of basis of discounts are:

- the number of visits during a given period;

- the direction of the goods and the quantity of goods loaded/unloaded/on board;

- the number of times the ship has called at ports in the same country;

- the environmental performance of the ship;

- minimum/maximum charge limits may apply;

- non-commercial vessels, certain types of vessels (e.g. fishing vessels), vessels engaged in certain activities/activities or port calls fee to special circumstances may benefit from substantial discounts or be exempted from part of the charges;

- special permits.

- Environmental Ship Index (ESI) - e.g. Tallinn, Stockholm, Helsinki.

- Clean Shipping Index (CSI) - e.g. Helsinki, Stockholm, Sweden’s fairway fee.

- Green Award Certificate.

- Noise level.

- On investment/innovation verifiable by calculations/measurements – e.g. Helsinki.

- Rebate depending on the type of fuel used- e.g. Riga - LNG.

- Equipment on board - e.g. Ventspils, whether certain ships have an incinerator on board.

- Ship uses shore-side electricity under certain conditions for longer - e.g., Stockholm.

3.2. Calculation of Port Fees

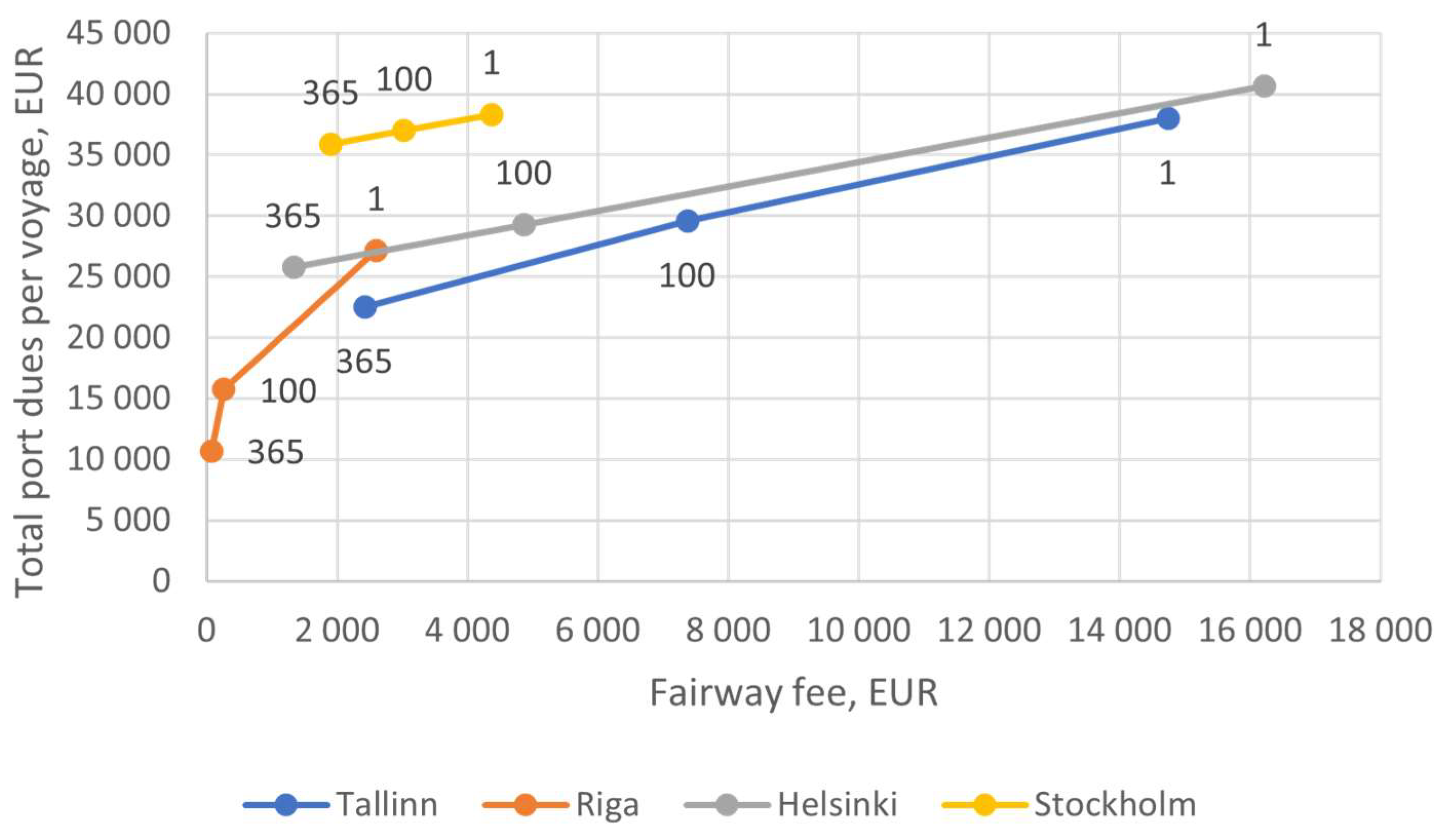

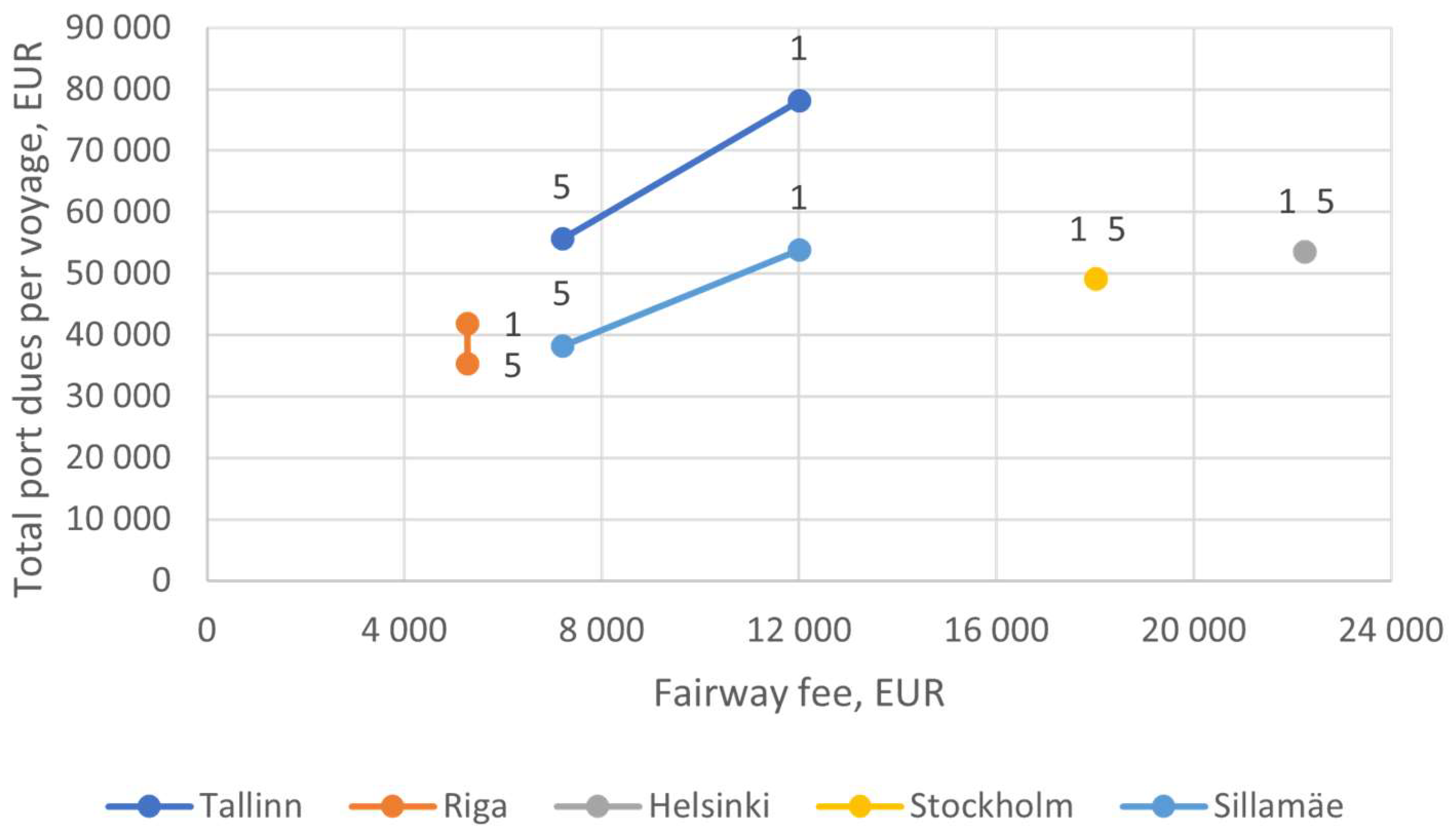

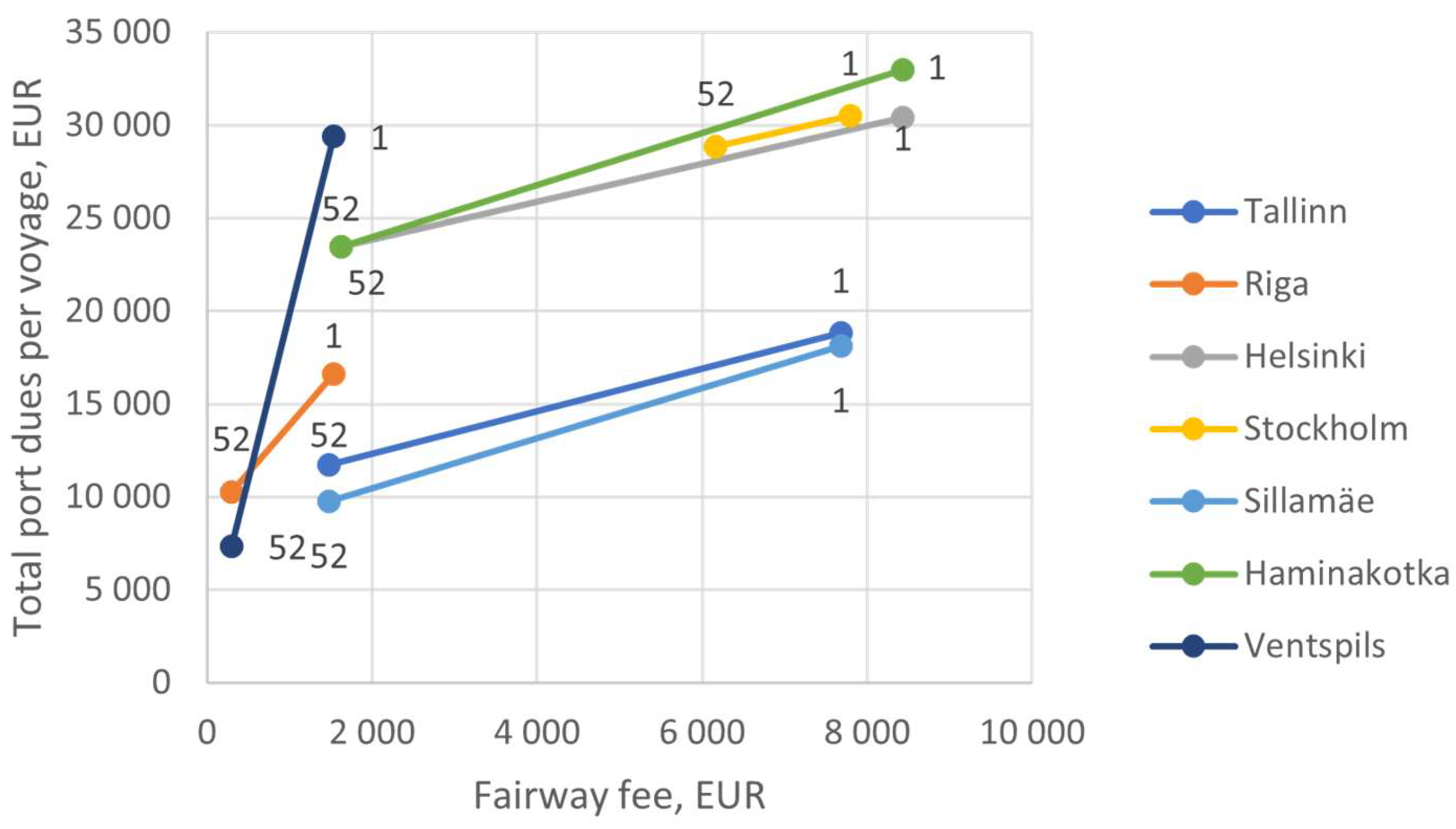

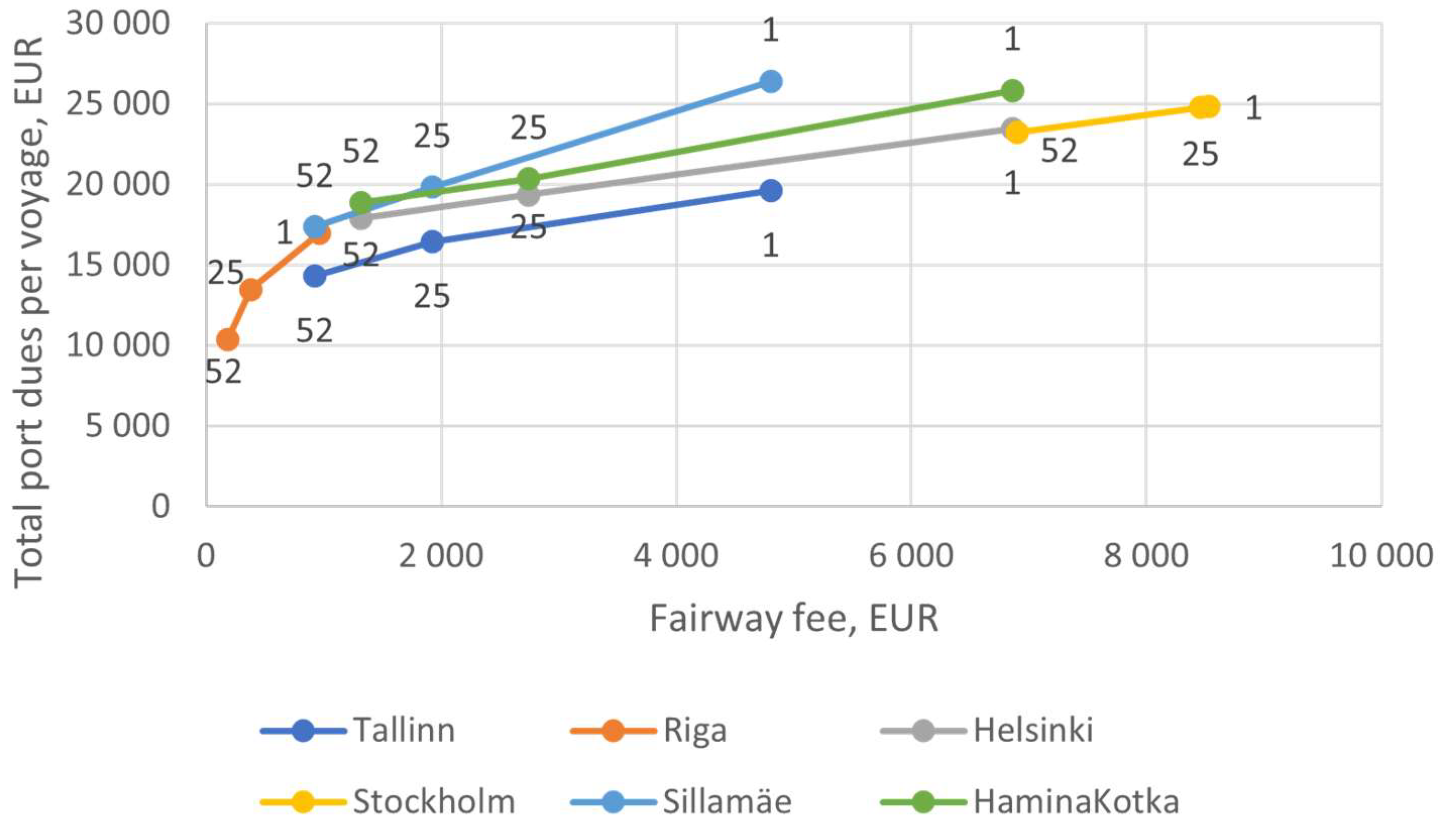

3.3. Comparison of Port Fees

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSI | Clean Shipping Index |

| DWT | Deadweight |

| EMDE | Estonian Electronic Maritime Information System |

| ESI | Environmental Ship Index |

| EU | European Union |

| EUR | Euro |

| GT | Gross Tonnage |

| NT | Net Tonnage |

| lm | Lane Meter |

| LNG | Liquified Natural Gas |

| m | Metre (UK) /meter (US) |

| mln | Million |

| RGT | Reduced Gross Tonnage |

| ro-ro | Roll on-roll off |

| TEU | Twenty Foot Equivalent Unit |

| UN | United Nations |

| VTS | Vessel Traffic Services |

References

- T. Notteboom, A. Pallis, and J.-P. Rodrigue, Port Economics, Management and Policy, 1st ed. London: Routledge, 2022. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- FINLEX ® - Ajantasainen lainsäädäntö: Laki Väylävirastosta 862/2009. Oikeusministeriö, Edita Lakitieto Oy. Accessed: Feb. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/2009/20090862.

- “Transpordiameti põhimäärus–Riigi Teataja.” Accessed: Feb. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/109122020001?leiaKehtiv.

- “Meresõiduohutuse seadus–Riigi Teataja.” Accessed: Feb. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/MSOS.

- “Maritime Safety Act–Riigi Teataja.” Accessed: Apr. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/511012024001/consolide.

- G. Sootla, L. Kalev, and K. Kattai, Eds., Avalik poliitika. I, Avaliku poliitika kujundamise protsess. Tallinn: TLÜ Kirjastus, 2021. Accessed: Feb. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.digar.ee/arhiiv/nlib-digar:994949.

- Parliament of Estonia, “Riigi 2020. aasta lisaeelarve seadusega seonduvate seaduste muutmise seadus (COVID-19 haigust põhjustava koroonaviiruse levikuga seotud meetmed) 169 SE,” Riigikogu. Accessed: Feb. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.riigikogu.ee/tegevus/eelnoud/eelnou/cad9e912-b0d8-428d-be1f-b14e22ed5ecd/riigi-2020.-aasta-lisaeelarve-seadusega-seonduvate-seaduste-muutmise-seadus-covid-19-haigust-pohjustava-koroonaviiruse-levikuga-seotud-meetmed/.

- H. E. Haralambides, “Competition, Excess Capacity, and the Pricing of Port Infrastructure,” Marit Econ Logist, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 323–347, Dec. 2002. [CrossRef]

- U. Tapaninen, Maritime transport : shipping logistics and operations. London [etc.]: Kogan Page, 2020.

- Meyiwa and M. Chasomeris, “South Africa’s port doctrine: dilemmas and the way forward,” Maritime Studies, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 179–191, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Haralambides, E. Musso, and M. Benacchio, “Port Financing and Pricing in the European Union: Theory, Politics and Reality,” Maritime Economics and Logistics, vol. 3, pp. 368–386, Dec. 2001. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Mthembu and M. Chasomeris, “Revisiting marine services pricing in South Africa’s ports,” WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 5–24, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Van Den Berg, P. W. De Langen, and P. C. J. Van Zuijlen, “Revisiting port pricing; a proposal for seven port pricing principles,” WMU J Marit Affairs, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 421–438, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Acciaro, “A Critical Review of Port Pricing Literature: What Role for Academic Research?,” The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 207–228, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Bergqvist and N. Egels-Zandén, “Green port dues — The case of hinterland transport,” Research in Transportation Business & Management, vol. 5, pp. 85–91, Dec. 2012. [CrossRef]

- “Comparative analysis of port tariffs in the ESCAP region.” 2002. [Online]. Available: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12870/2916.

- Hinterhuber, “Customer value-based pricing strategies: why companies resist,” Journal of Business Strategy, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 41–50, Jan. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Lavissiere, “Vessel Port Dues: An Influence from Path Dependency rather than Geography of Ports,” The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 61–70, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Eidast, Meretranspordi kommertsekspluatatsioon. Tallinn: Tallinn : Eesti Mereakadeemia, 2007.

- Directive (EU) 2019/883 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on port reception facilities for the delivery of waste from ships, amending Directive 2010/65/EU and repealing Directive 2000/59/EC (Text with EEA relevance), vol. 151. 2019. Accessed: Dec. 02, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/883/oj/eng.

- “Port Fees and Rules - Freeport of Ventspils authority.” Accessed: Oct. 10, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.portofventspils.lv/en/port-services/port-fees-and-rules/.

- “Port Dues | Freeport of Riga Authority.” Accessed: Oct. 10, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://rop.lv/en/port-dues.

- “Information Regarding Navigation Due For Vessels Entering Latvian Ports.” Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Latvia, Dec. 21, 2021. Accessed: Dec. 05, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.lja.lv/sites/default/files/pricelist_attachments/Navigation_due_2022.docx.

- “Price List 2022 | Helsinki.” Port of Helsinki, 2021. Accessed: Sep. 08, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.portofhelsinki.fi/sites/default/files/attachments/Price%20List%202022_0.pdf.

- “Additional information and implementation guidelines concerning the environmental discount 2022.” Port of Helsinki, 2021. Accessed: Sep. 08, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.portofhelsinki.fi/sites/default/files/attachments/Additional%20information%20and%20implementation%20guidelines%20concerning%20the%20environmental%20discount%20_2022.pdf.

- “Fairway dues - Finnish Customs,” Tulli. Accessed: Oct. 12, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://tulli.fi/en/businesses/transport-and-warehousing/fairway-dues.

- “Pilotage fees,” Finnpilot. Accessed: Nov. 12, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://finnpilot.fi/en/for-customers/pilotage-fees/.

- “Prices for services/tariffs - portsofstockholm.com.” Accessed: Sep. 16, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.portsofstockholm.com/about-us/prices-for-servicestariffs/.

- “price-list-2022_eng.pdf.” Accessed: Jul. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sjofartsverket.se/contentassets/ac04e861247b4019a9c0a9ea848904f3/price-list-2022_eng.pdf.

- “sjofartsverkets-foreskrifter-sjofs-2022-2-om-tillhandahallande-av-lots-lotsbestallning-tilldelning-av-lots-och-lotsavgifter---english-version.pdf.” Accessed: Jul. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sjofartsverket.se/globalassets/om-sjofartsverket/lagrum/oversatta-forfattningar/sjofartsverkets-foreskrifter-sjofs-2022-2-om-tillhandahallande-av-lots-lotsbestallning-tilldelning-av-lots-och-lotsavgifter---english-version.pdf.

- “Dues and fees.” Accessed: Jul. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sjofartsverket.se/en/about-us/about-the-swedish-maritime-administration/dues-and-fees/#fairway-dues.

- “Lootsitasud — Eesti loots.” Accessed: Oct. 10, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.loots.ee/lootsitasud/.

- “Sadamatasud_al_01_05_2022_002_.pdf.” Accessed: Jul. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ts.ee/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Sadamatasud_al_01_05_2022_002_.pdf.

- “silport_sadamaeeskirjad.pdf.” Accessed: Jul. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.silport.ee/silport_sadamaeeskirjad.pdf?rand=77.

- “Maritime Safety Act–Riigi Teataja.” Accessed: Sep. 28, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/ee/520122021001/consolide.

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/91 of 21 January 2022 defining the criteria for determining that a ship produces reduced quantities of waste and manages its waste in a sustainable and environmentally sound manner in accordance with Directive (EU) 2019/883 of the European Parliament and of the Council (Text with EEA relevance), vol. 015. 2022. Accessed: Dec. 02, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2022/91/oj/eng.

- “ABS: American Bureau of Shipping.” Accessed: Jun. 21, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://absrecord.eagle.org/#/absrecord/details.

- “DNV Vessel Register.” Accessed: Jun. 21, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://vesselregister.dnv.com/vesselregister/details/32300.

- “DNV Vessel Register.” Accessed: Jun. 21, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://vesselregister.dnv.com/vesselregister/details/23655.

- “DNV Vessel Register.” Accessed: Jun. 21, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://vesselregister.dnv.com/vesselregister/details/G113538.

- “DNV Vessel Register.” Accessed: Jun. 21, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://vesselregister.dnv.com/vesselregister/details/31618.

- “Fleet,” Hansa Shipping AS. Accessed: Jun. 21, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.hansashipping.ee/fleet.

- “Megastar - Tallink Silja Line.” Accessed: Jun. 21, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.tallink.com/fleet/fast-vessels/megastar.

- “Electronic Maritime Information System / TRANSPORDIAMET.” Accessed: Aug. 06, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.emde.ee/pm5052/vi-.

- U. Tapaninen and R. Palu, “Recovery of ro-pax ferry traffic from covid-19 under tightening environmental regulations: case Helsinki-Tallinn,” Journal of Shipping and Trade, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 10, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- “Key Figures,” Port of Tallinn. Accessed: Jun. 14, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ts.ee/en/investor/key-figures/.

- “Ostu likums,” LIKUMI.LV. Accessed: Apr. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://likumi.lv/doc.php?id=57435.

- H. Meersman, S. P. Strandenes, and E. van de Voorde, “Port Pricing: Principles, Structure and Models,” SSRN Journal, 2014. [CrossRef]

- “BV Fleet | Marine & Offshore.” Accessed: Jul. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://marine-offshore.bureauveritas.com/bv-fleet/#/bv-fleet/.

- “v.3-price-list-fairway-and-pilot-fees-2024.pdf.” Accessed: Jul. 18, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sjofartsverket.se/globalassets/tjanster/anlopstjanster/avgiftsforandringar-2024/v.3-price-list-fairway-and-pilot-fees-2024.pdf.

- Transpordi ja liikuvuse programm 2024-2027. 2024. Accessed: Jul. 18, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/883/oj/eng.

- “Esitys väylämaksulain muuttamisesta lausunnoille,” Valtioneuvosto. Accessed: Jul. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://valtioneuvosto.fi/-/1410829/esitys-vaylamaksulain-muuttamisesta-lausunnoille.

| Fee type | Estonia | Latvia | Finland | Sweden | Alternative term used | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tallinn | Sillamäe | Riga | Ventspils | Helsinki | Hamina Kotka | Stockholm | ||

| Vessel fee | GT, vessel type | GT, vessel type | GT, vessel type | NT cargo or passenger vessel | NT cargo or passenger vessel | GT | tonnage fee; vessel charge | |

| Canal fee | GT, vessel type | GT | ||||||

| Berth(ing) fee | GT, vessel type | GT | ||||||

| Waste management charges | GT, vessel type | GT, vessel type | GT, vessel type | Vessel type, GT, staying time span | NT, cargo or passenger vessel | NT, cargo or passenger vessel | Fixed, GT, m3, ton | waste fee; sanitary fee; solid waste + sewage + oil-containing waste originating from engine room |

| Mooring and unmooring carges | Per operation, GT range | Per operation, GT range, vessel type | Per operation, GT range | Per operation, GT range | Per operation, NT range | Per operation, NT range | Per operation, vessel length, time | |

| Passenger fee | Passenger | Passenger | Passenger | Passenger | Passenger | Passenger | passenger | |

| Cargo charge | Cargo unit* | Cargo unit/ ton | Cargo unit/ ton | Cargo unit/ ton/ lm | * vehicle cargo charge | |||

| Pilotage charge | GT range, pilotage in port+ distance 1 | GT range, pilotage in port+ distance 1 | GT, operation, (+ distance on sea if needed) | NT range, base fee+ distance 3 | NT range, base fee+ distance 3 | NT range, base fee+ distance 2 | ||

| Fairway fee | GT, ice-class 2 | GT, ice-class 2 | GT, vessel type 2 | GT, vessel type 2 | NT, ice-class, amount of cargo 4 | NT, ice-class, amount of cargo 4 | NT range, vessel’s environmental category, goods/passengers 2 | fairway due, waterway fee/due, navigation fee/due |

| General Cargo vessel | Container vessel | Tanker | Bulker | Ro-ro vessel | Cruise vessel | Passenger Ferry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length, m | 100.71 | 170.02 | 169.5 | 187 | 187.06 | 293.2 | 212 |

| GT | 3610 | 16023 | 15980 | 22746 | 25609 | 99526 | 49134 |

| RGT | 12748 | ||||||

| NT | 1783 | 6251 | 7777 | 12344 | 7682 | 63078 | 15621 |

| DWT | 5164 | 20073 | 25117 | 36746 | 11702 | 7900 | 6080 |

| TEU | 1440 | 156 | |||||

| Passengers | 2506 | 2800 | |||||

| Ro-ro capacity, lm | 3322 | 3653 | |||||

| Ice-class | 1C | 1A | 1A Super | 1C | 1A | --- | 1A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).