1. Introduction

The inflationary episode of 1603 was a defining event in Spain’s economic history, characterized by substantial monetary and social transformations. Triggered by the influx of precious metals from the Americas, this phenomenon disrupted price stability, altered income distribution, and affected the broader economic equilibrium. Understanding the mechanisms behind this historical inflation offers valuable insights into contemporary economic challenges, especially in periods of rapid monetary expansion.

Recent studies, such as those by Hamilton (1934) and Flynn (1978), have explored the broader implications of early modern inflationary episodes. However, existing analyzes often lack a robust theoretical framework for interpreting the uneven impacts of inflation across economic actors. Austrian Economic Theory, particularly the Cantillon Effect and the Austrian Business Cycle Theory, provides a comprehensive lens to examine these distortions. The Cantillon Effect emphasizes how monetary expansion benefits some sectors while impoverishing others (Cantillon, 1755), while the Austrian Business Cycle Theory underscores the misallocation of resources caused by artificial increases in the money supply (Mises, 1949).

This study integrates historical data with Austrian theoretical insights to explore the relationships between monetary expansion, raw material prices, and real wages in early 17th-century Spain. Using datasets normalized to 1601 as the base year, this study employs statistical methods to assess the impact of precious metal imports on economic variables. The findings highlight the uneven social and economic consequences of inflation, offering a nuanced understanding of Spain’s monetary history.

By bridging historical analysis with economic theory, this paper contributes to ongoing debates about the causes and consequences of inflationary episodes. The results not only deepen our understanding of Spain’s Golden Age economy but also provide a framework for interpreting similar phenomena in modern economies.

1.1. Historical Context

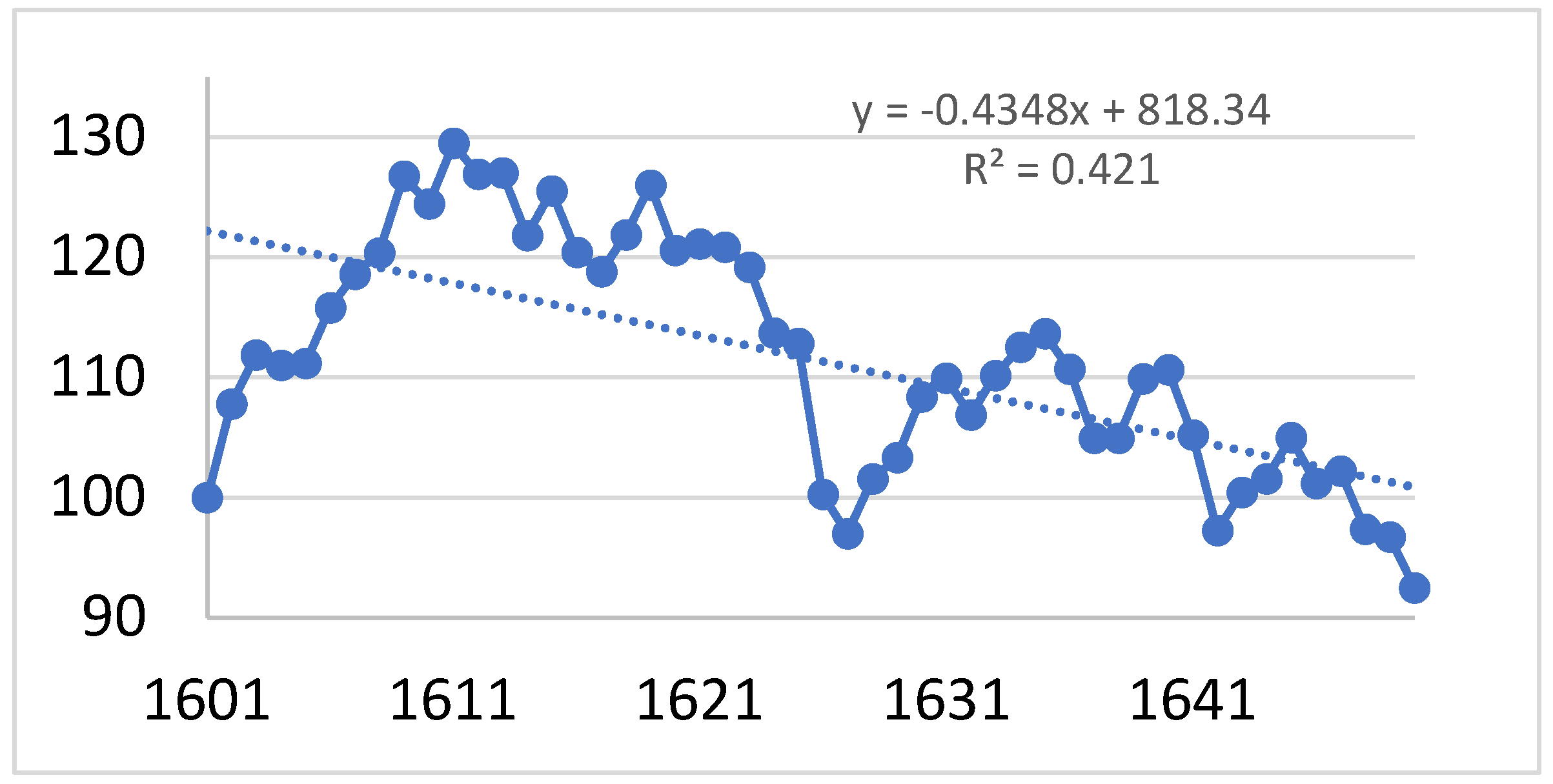

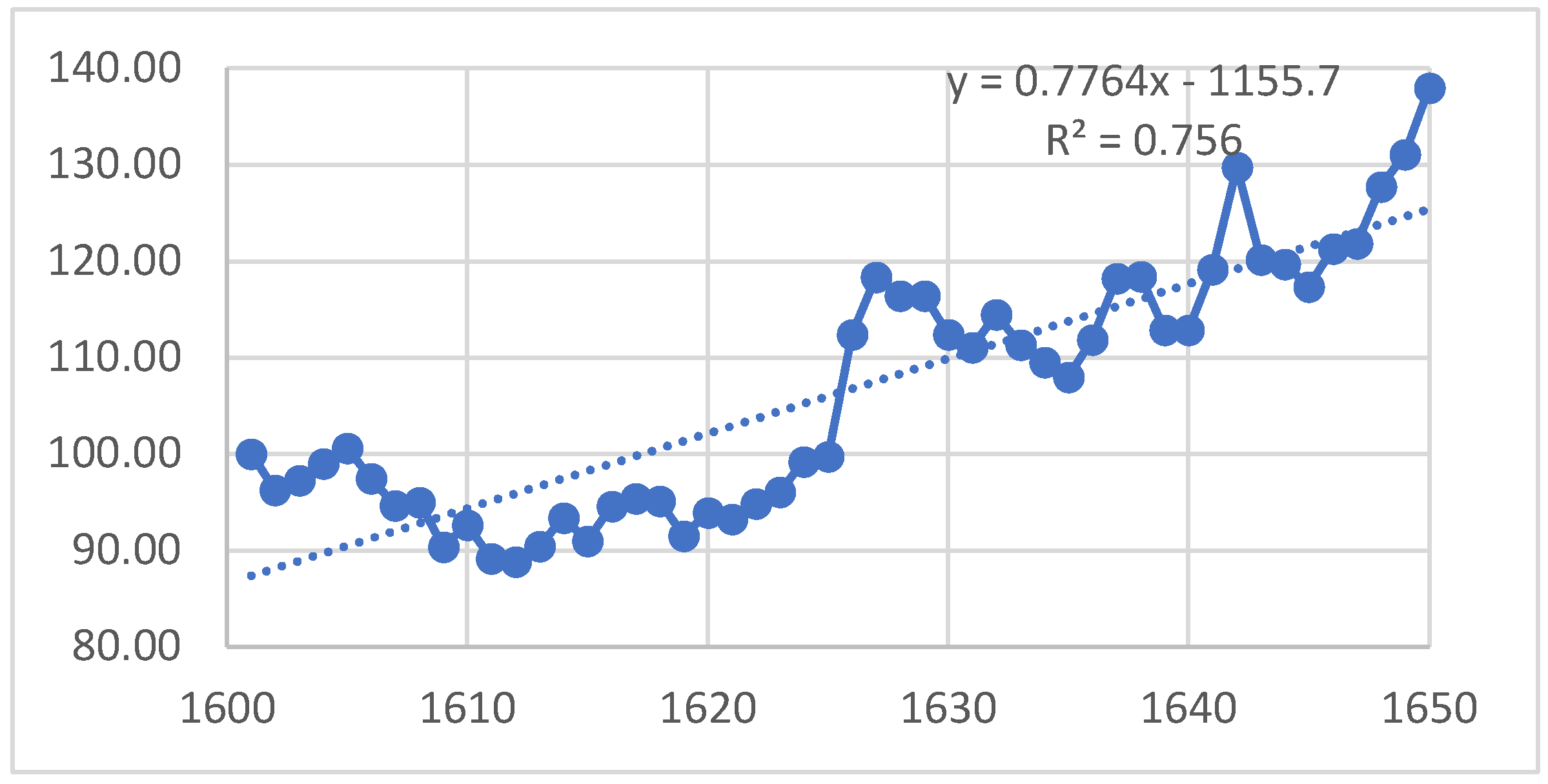

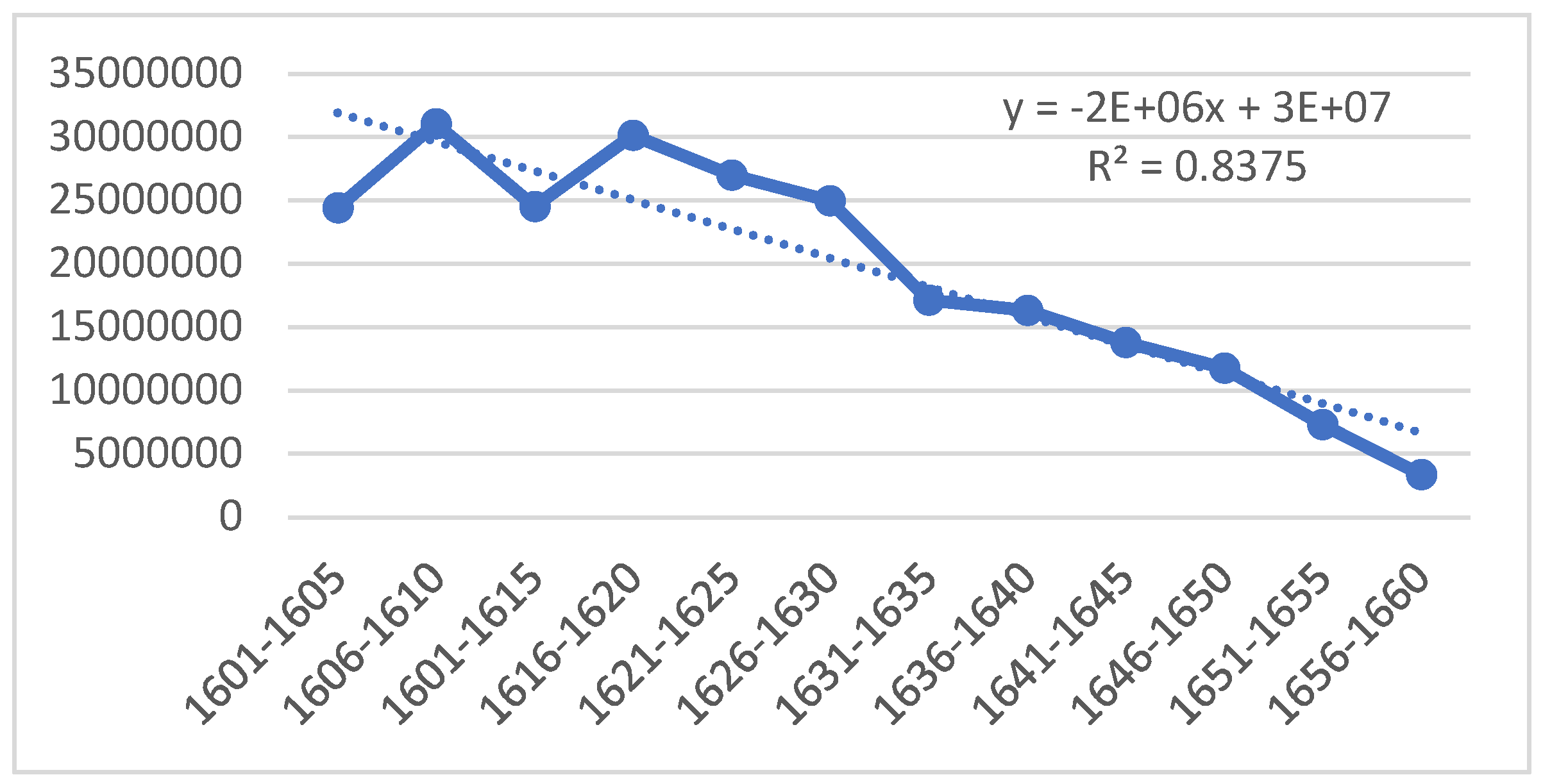

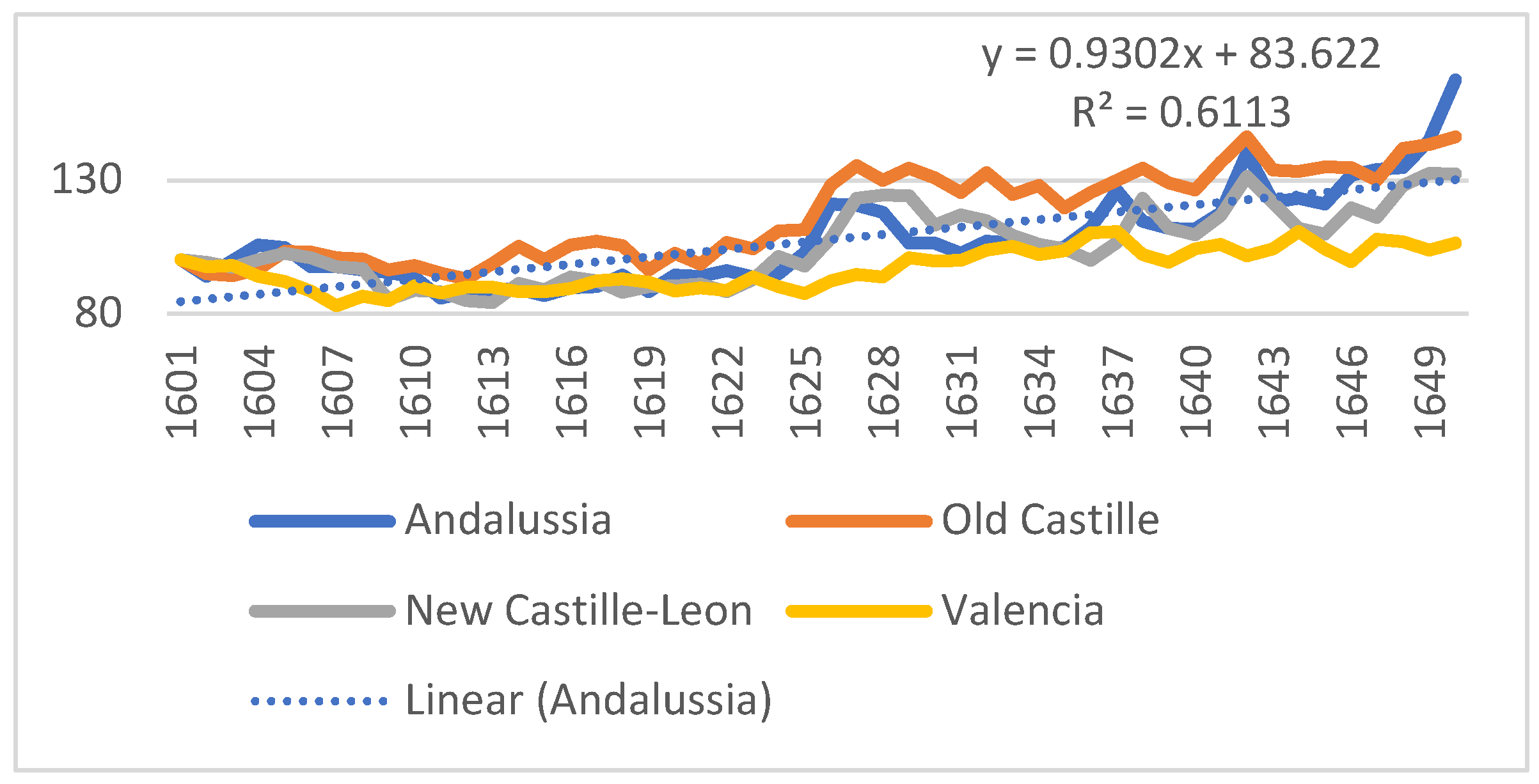

This section presents the findings of the study, focusing on the relationships between precious metal imports, raw material prices, and real wages during the period 1601–1650. The results are supported by descriptive statistics, regression analysis, and theoretical interpretations. Figures and tables are included to illustrate key trends and relationships.

The inflationary episode that occurred in Spain in 1603 is framed within the Spanish Golden Age, a period of cultural brilliance and economic challenges that spanned approximately from the late 15th century to the late 17th century. This period, marked by significant advancements in literature, art, and science, was also shaped by complex economic dynamics driven by the influx of precious metals from Spanish America and the effects of multiple military conflicts.

Following the discovery of the Americas in 1492, Spain saw a substantial influx of gold and silver, particularly from the mines of Potosí in Upper Peru (modern-day Bolivia) and Zacatecas in Mexico. These precious metals played a crucial role in financing European wars and the Crown’s expenditures; however, they also had disruptive effects on the national economy (Elliott, 1963). Hamilton (1934) argues that the influx of precious metals led to sustained inflation during the 16th and 17th centuries, a phenomenon known as the "Price Revolution."

Hamilton (1934) further posits that the constant flow of gold and silver from America increased the amount of money supply without a corresponding increase in the production of goods and services, resulting in a general rise in prices

1. This phenomenon particularly affected local economies, destabilising prices and widening the gap between the rich and the poor. Borges et al. (2018) confirm that fluctuations in the supply of silver impacted economies across Europe, suggesting that Spain’s experience with inflation is part of a broader trend of economic instability across the continent during this time.

Furthermore, Bennassar (1996) describes how this inflation exacerbated social inequalities. While the nobility and clergy were able to shield themselves from the worst effects, the lower classes and peasants saw their purchasing power significantly decline. Inflation also impacted urban workers, whose wages did not increase at the same rate as prices.

The fiscal policy of the time, characterised by an inefficient and regressive tax system, worsened inflationary pressures. Martínez Shaw (1994) explains how the Crown frequently resorted to currency devaluation to finance its expenses, further intensifying inflation. Moreover, the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648) against the Netherlands and other European conflicts drained Spain’s financial resources, increasing public debt and the issuance of debased currency. A recent analysis of inflation persistence in Spain highlights how external shocks can trigger prolonged inflationary pressures (Ayestarán, Infante, Tenorio, & Gil-Alana, 2023), underscoring the relevance of this historical episode in understanding inflationary dynamics.

Vilar (1994) offers a broad perspective on how these economic phenomena and fiscal policies were intertwined with Spain's social and political structure. Vilar highlights Spain’s dependence on the importation of precious metals and how this reliance created a fragile economy vulnerable to international fluctuations.

Lastly, Kamen (2003) complements this view by analysing the social and political implications of inflation. Kamen notes that inflation not only impacted the economy but also contributed to growing social discontent and internal political tensions, which eventually weakened the monarchy’s central power.

The inflationary episode of 1603 in Spain represents a complex phenomenon that reflects the interactions between multiple economic, social, and political factors during the Spanish Golden Age. This period, marked by the abundance of precious metals from Spanish America, demonstrates how the massive influx of gold and silver could trigger a chain of effects that deeply transformed Spain’s economy and society.

1.2. Objectives

This paper aims to provide an explanation of the inflationary episode experienced by Spain starting in 1603. To achieve this, we will first examine the internal and external causes that led to the exaggerated growth in prices. Subsequently, we will present an overview of the development of this inflationary episode, beginning from the late 15th century, specifically with the Discovery of America. This description will be complemented with relevant data and statistics.

Next, we will analyze the consequences of this inflation, employing the analytical tools of the Austrian School of Economics, particularly focusing on the effects of inflation on capital accumulation and income distribution. Furthermore, historiographical interpretations of this event will be contrasted with the Austrian perspective. Various economic historians have provided explanations based on different theoretical frameworks, and we will attempt to refute these points. Finally, we will formulate the corresponding conclusions.

2. Causes of the Inflation

2.1. External Factors

One of the main external factors that contributed to inflation in Spain in 1603 was the massive importation of precious metals from Spanish America. Since the discovery of the New World, large quantities of gold and silver were sent to Europe, particularly to Spain, the leading power in the conquests. The mines of Potosí in Upper Peru (present-day Bolivia) and Zacatecas in Mexico were particularly important in this flow of precious metals to Europe.

The impact of this influx of metals was profound. The amount of money in circulation increased dramatically, but the production of goods and services did not grow proportionally, resulting in an imbalance between supply and demand. This phenomenon, known as the "Price Revolution," led to a sustained increase in prices throughout the 16th and early 17th centuries. The resulting inflation not only affected Spain but also had repercussions across Europe by altering prices and the monetary economy of the continent (Hamilton, 1934, pp. 117-119; Martínez Shaw, 1994).

Another crucial external factor in the inflation of 1603 was the impact of the Eighty Years' War (the Dutch Revolt) and other European wars (Parker, 1972). The Eighty Years' War, which pitted Spain against the Netherlands, was a protracted conflict that demanded enormous financial resources. To finance this and other conflicts, the Spanish Crown resorted to the issuance of low-quality currency and borrowing, which exacerbated inflationary pressures. As Kamen points out:

"The Eighty Years' War and other prolonged conflicts drained the resources of the Spanish Crown, leading it to repeatedly resort to the issuance of public debt. By 1600, the Crown's debt had reached unprecedented levels, exacerbating inflationary pressures and economic instability" (Kamen, 2003, p. 201).

Thus, the war not only drained the country's financial resources but also diverted labor and material resources toward the war effort, reducing the productive capacity of the Spanish economy. Furthermore, the military conflicts increased economic and political instability, generating uncertainty that negatively impacted the economy. The increase in taxes to finance the wars also contributed to inflation, as the costs were passed on to consumers through higher prices.

In summary, the inflation in Spain in 1603 was the result of a combination of external factors. The massive importation of precious metals from America increased the amount of money in circulation without a proportional increase in the production of goods and services. Meanwhile, the costs and consequences of European wars, especially the Eighty Years' War, drained resources and generated economic and political instability. These external factors interrelated to create an economic environment conducive to the sustained inflation that characterized Spain during this period.

2.2. Internal Factors

One of the primary internal factors contributing to inflation in 1603 was the fiscal and monetary policy adopted by the Spanish Crown. The need to finance prolonged wars, such as the Eighty Years' War, compelled the government to resort to issuing low-quality currency, known as "vellón." This devaluation of the currency had an immediate inflationary effect, as the money supply significantly increased without a corresponding rise in the production of goods and services (Hamilton, 1934, pp. 157-160).

Martínez Shaw (1994) explanis that the fiscal policy of the time also played a crucial role, as the Crown increased the tax burden to finance the war effort, further exacerbating the economic situation. The tax burden disproportionately fell on the lower classes and peasants, who were already struggling with rising prices. This inefficient fiscal policy not only intensified inflation but also deepened social inequalities.

Another internal factor was the state of agriculture and local production. The Spanish economy of the 17th century relied heavily on agriculture, which faced numerous challenges. Agricultural techniques were largely primitive, characteristic of a precapitalist economy, resulting in low agricultural productivity. Poor harvests and frequent droughts exacerbated these problems, reducing the supply of food and other basic agricultural products.

The lack of technological innovation and restrictions on land ownership also played a significant role. Most agricultural land was in the hands of the nobility and the Church (dead hands), who had little incentive to improve agricultural techniques. Consequently, local production could not meet the growing demand, contributing to inflation (Bennassar, 1979, p. 143).

The social and economic structure of Spain during the Golden Age was also a significant internal factor in inflation. Society was highly stratified, with a substantial gap between the rich and the poor. The nobility and clergy controlled a large portion of wealth and resources, while the lower classes and peasants struggled to survive in an inflationary economy. This rigid social structure limited economic and social mobility, creating an environment in which it was difficult for the lower classes to improve their economic situation. The lack of economic opportunities and rising prices led to growing social discontent, which, in turn, contributed to economic instability (Kamen, 2003, p. 204).

In summary, inflation in Spain in 1603 was the result of a combination of internal and external factors. Inefficient fiscal and monetary policies, the state of agriculture and local production, and the social and economic structure of the country all played crucial roles in this phenomenon. These internal factors, along with the previously discussed external factors, created an environment conducive to sustained inflation that had profound repercussions on the economy and society of Golden Age Spain.

3. Matterials and Methods

3.1. Description of the Phenomenon

The inflationary episode that unfolded in Spain during the 17th century, particularly in 1603, is a phenomenon that had a profound and multifaceted impact on the economy and society of the time. This inflationary process is characterised by a sustained and widespread increase in prices, which affected different economic sectors unequally.

The rise in prices during this period was remarkable and impacted nearly all aspects of the economy. According to studies conducted by Hamilton (1934), prices in Spain increased on average by 400% between 1501 and 1650, with especially high peaks in the early decades of the 17th century. This increase in prices, largely driven by the influx of precious metals from America, generated sustained inflation that disrupted the national economy.

The economic impact of this inflation was significant. The loss of value of money affected the purchasing power of the population, especially those with fixed incomes, such as urban workers and peasants. Real wages did not adjust at the same pace as prices, resulting in a decrease in purchasing power and a deterioration of living conditions (Martínez Shaw, 1994, pp. 175-178).

The agricultural sector was one of the most affected by inflation. Agricultural production in Spain was already facing multiple challenges, including primitive farming techniques and adverse climatic conditions. Inflation exacerbated these issues by increasing the cost of agricultural inputs, further reducing the sector's profitability. Furthermore, small farmers and peasants were the most disadvantaged, as they were unable to adjust their selling prices at the same rate as consumer goods prices (Bennassar, 1979, p. 120).

Trade, both internal and external, also suffered the consequences of inflation. Merchants faced a volatile economic environment, where uncertainty about future prices made planning and investment difficult. The depreciation of the currency and inflation led to increased transportation and storage costs, negatively impacting trading profits. Martínez Shaw (1994) describes how this resulted in a decline in commercial activity and the disruption of many established trade networks.

Lastly, the manufacturing sector, although less developed than in other European countries, also experienced repercussions due to inflation. The costs of raw materials and labour increased, reducing profit margins and hindering the competitiveness of Spanish products in international markets. Inflation, combined with a lack of technological innovation, contributed to the stagnation of the manufacturing sector, limiting its capacity for expansion and development (Hamilton, 1934, pp. 140-142). In a country less intensive in capital, inflation posed a more significant detriment.

3.2. Methodology

To study this phenomenon and demonstrate that the influx of precious metals from the Americas led to a decline in the standard of living for Spaniards—manifested through rising raw material prices and falling real wages—we utilized data from the book American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain, published by Earl J. Hamilton in 1954.

This book provides tables spanning the period 1501–1650; however, many data points were missing. As a result, we focused our study on the years 1601–1650, where the data were more complete. Missing data points, such as the Andalusian price index for 1621, were estimated using a moving average of the adjacent years

The information was organized into four tables derived from Hamilton’s dataset and processed in Excel for the specified period. In the original source, raw material prices were presented in three separate tables, each covering a 50-year span. For our analysis, we selected only the data corresponding to the final third of the studied period. However, Hamilton’s original study used 1621 as the base year. We adjusted this to 1601—the beginning of our series—to align with our hypothesis. The normalization of indices to a common base year was performed using Equation 1:

where “Base” represents the raw material price in 1601,

is the price in the following year based on the original base, and

is the price in the current year under the adjusted base.

Additionally, to calculate the totals in Table 2, we used an arithmetic average of the four regions. This approach was necessary due to the absence of reliable statistics on the relative weights of each region in terms of population, production, or other relevant factors.

3.3. Data and Statistics

The data and statistics could be found in the Appendices at the end of the paper.

5. Consequences of Inflation

5.1. Economic Impact

The inflation that occurred in Spain during the 17th century had profound and lasting effects on production and trade. The widespread increase in prices, without a corresponding rise in the production of goods and services, led to significant economic imbalances (Hamilton, 1938).

Firstly, inflation severely impacted agricultural production. With the rising costs of agricultural raw materials and the declining purchasing power of farmers, agricultural output suffered a decline. Farmers could not adjust their prices as quickly as costs increased, resulting in decreased production and a greater scarcity of basic commodities (Hamilton, 1934, pp. 140-142).

The commercial sector was also affected by inflation. Merchants faced a volatile economic environment, where the depreciation of currency and rising prices made long-term economic calculations extremely challenging. Transportation and storage costs increased, negatively affecting profit margins. Economic instability generated uncertainty, disincentivising investment and commercial expansion (Martínez Shaw, 1994, pp. 175-178).

Moreover, inflation disproportionately impacted different sectors of the population, exacerbating existing economic and social inequalities. The most affected groups included urban workers, peasants, and small traders

2.

Workers whose incomes were predominantly derived from labour, such as artisans and peasants, were among the hardest hit by inflation. While the prices of goods and services rose, their wages did not adjust proportionally, resulting in a significant loss of purchasing power. This led to widespread impoverishment among these groups, who were already in a precarious economic position (Bennassar, 1979, p. 120).

Similarly, small traders, who relied on price stability to plan their economic activities, also suffered. Inflation increased operational costs, reduced profit margins, and led to the bankruptcy of many businesses. This situation contributed to the impoverishment of traders and their families, exacerbating economic inequality (Hamilton, 1934, pp. 157-160).

5.2. Social Impact

The inflationary episode in Spain during the 17th century had profound social consequences, exacerbating existing inequalities and generating new socioeconomic dynamics. This phenomenon destabilized society, disproportionately affecting various groups and altering the social fabric in significant ways.

Firstly, Yun Casalilla (2004) provides a nuanced analysis of the social stratification of inflationary effects during this period. Yun Casalilla argues that while some segments of society, particularly the nobility and clergy, were better equipped to weather inflationary pressures, others experienced severe economic hardship. The upper echelons of society often possessed diverse asset portfolios and the ability to adjust land rents, which provided a buffer against the erosion of their economic position (Yun Casalilla, 2004, pp. 325-330).

This perspective aligns with Hamilton's (1934) data, which demonstrates that prices in Spain rose by an average of 400% between 1501 and 1650, with particularly sharp increases in the early 17th century. The dramatic rise in prices had far-reaching effects on different social strata, as highlighted by both Hamilton and Yun Casalilla (Hamilton, 1934, pp. 117-119; Yun Casalilla, 2004, pp. 331-335).

Bennassar (1979) and Yun Casalilla (2004) both offer valuable insights into how inflation impacted the agricultural sector and rural populations. They argue that the rising costs of agricultural inputs, combined with the declining purchasing power of farmers, led to decreased agricultural production and greater scarcity of basic commodities. This situation particularly affected small farmers and rural workers, who struggled to maintain their livelihoods in the face of rising prices and stagnant wages (Bennassar, 1979, p. 120; Yun Casalilla, 2004, pp. 340-345).

Also, Martínez Shaw (1994) and Yun Casalilla (2004) both elaborate on the effects of inflation on urban workers and artisans. They note that while prices rose dramatically, wages failed to keep pace, resulting in a significant erosion of purchasing power for these groups. This disparity led to a decline in living standards and increased economic hardship for urban populations, contributing to social unrest in cities across Spain (Martínez Shaw, 1994, pp. 175-178; Yun Casalilla, 2004, pp. 350-355).

Additionally, Kamen (2003) and Yun Casalilla (2004) provide broader perspectives on the social and political implications of inflation. They argue that the economic instability caused by inflation contributed to growing social discontent and internal political tensions. The widening gap between the wealthy elite and the impoverished masses intensified social stratification, weakening the monarchy's central power and contributing to the overall decline of the Spanish Empire (Kamen, 2003, p. 204; Yun Casalilla, 2004, pp. 360-365).

Furthermore, Yun Casalilla's research illuminates how inflation served as a catalyst for altering patterns of social mobility. He demonstrates that opportunities for upward mobility diminished, particularly for the middle and lower classes, as economic instability eroded savings and investment capabilities. This trend reinforced existing social hierarchies and limited economic opportunities for large segments of the population (Yun Casalilla, 2004, pp. 370-375).

In conclusion, the inflationary episode of 17th century Spain, as elucidated by the works of Hamilton, Bennassar, Martínez Shaw, Kamen, and particularly Yun Casalilla, had multifaceted social impacts. It reshaped societal structures, altered demographic patterns, and influenced cultural and intellectual trends. These social transformations, intertwined with economic changes, had long-lasting effects on Spanish society, contributing to the complex socioeconomic landscape of early modern Spain.

6. Historiographic Interpretations

6.1. Classical Perspectives

The inflationary phenomenon that affected Spain from 1603 and extended throughout much of the 17th century has been the subject of various interpretations by historians and economists from different schools of thought. Below, some of the most notable interpretations are presented from the Marxist, Keynesian, and Neoclassical perspectives.

From a Marxist perspective, the inflationary episode is viewed as a manifestation of the inherent contradictions within the emerging capitalist mode of production. Marxist historians argue that inflation was not merely a consequence of the arrival of precious metals from America but also of the increasing exploitation of the working class and the accumulation of capital in the hands of an ever-shrinking elite. This interpretation emphasises how inflation exacerbated social inequalities and led to heightened class conflict.

According to Vilar (1976), the influx of precious metals from America played a crucial role, but the true underlying cause of inflation was the contradiction between the growth of merchant capital and stagnant feudal production. Vilar contends that inflation was a symptom of the collapse of the feudal system and the emergence of capitalism (Vilar, 1976, pp. 321-324).

In contrast, the Keynesian interpretation of the inflationary phenomenon in Spain focuses on the imbalance between aggregate supply and demand. Keynesian economists argue that the arrival of precious metals increased the money supply, but the rigidity in the production of goods and services did not allow for a swift adjustment, resulting in a widespread rise in prices.

Although not explicitly identified as Keynesian, Hamilton (1934) analyzes how the influx of precious metals from America led to an increase in the money supply, a concept that resonates with the Keynesian idea of the impact of aggregate demand on prices. Hamilton also described how the increase in the quantity of money without a corresponding rise in production led to inflation

3.

From the Neoclassical perspective, inflation in Spain during the 17th century is primarily viewed as a monetary phenomenon. Neoclassical economists emphasise the relationship between the money supply and the price level, following the quantity theory of money. According to this interpretation, the increase in the money supply, without a corresponding increase in the production of goods and services due to the importation of precious metals from America, caused a proportional rise in prices.

Friedman (1963), although later than the period in question, developed the quantity theory of money, which is applicable to the analysis of this phenomenon. Friedman asserted that "inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon" (Friedman, 1969, p. 39), a statement that Neoclassical historians use to explain inflation in Spain. The arrival of large quantities of gold and silver increased the monetary base, and as production did not grow at the same rate, prices rose. However, the Neoclassical aggregate-based analysis overlooks the impact on income distribution and social inequalities, an area explored by Austrian analysis, which will be addressed in the following section.

In summary, classical interpretations of inflation in Spain during the 17th century vary significantly according to the school of thought. Marxists focus on the contradictions of the economic system and social inequalities, Keynesians on the imbalance between supply and demand, and Neoclassicals on the impact of the money supply on prices. Each interpretation offers a distinct perspective, enriching our understanding of the complex inflationary phenomenon that affected Spain during this period. However, the Austrian perspective evaluates the situation among different classes once inflation has occurred, as well as its impact on capital accumulation.

6.2. The Cantillon Efect

In this section, the analysis of the inflationary episode of 1603 will be explored from the perspective of the Austrian School of Economics. This approach emphasizes how inflation disproportionately affects lower-income classes and distorts capital accumulation, known as the Cantillon Effect.

Thus, the Austrian School argues that inflation is not neutral and affects different groups in society unevenly. This phenomenon is partly explained by the Cantillon Effect, which describes how newly created money is initially distributed to certain individuals or sectors before filtering through the rest of the economy. Those who receive the new money first benefit by spending it before prices rise, while those who receive it later face higher prices without a prior increase in their incomes. As Cantillon himself states:

"When there is an increase of actual money in a state, it does not at first distribute itself through the entire state to the hands of all the inhabitants. It is at first spent by those who receive it; and it is successively spread to the other people until the money has been distributed through the entire state. This money will have the same effect as a river which flows into the ocean, where the water will not rise immediately in the same level everywhere. It will rise first around the mouth of the river, and little by little it will be distributed until the water level is raised everywhere" (Cantillon, 1755/1978, p. 193).

Mises (1949) argued that inflation causes an unjust redistribution of wealth, disproportionately harming those with fixed incomes or wages that do not adjust rapidly to inflation. He states: "Inflation […] does not affect all people to the same extent and at the same time. It redistributes wealth and income. Some people profit from it; for them, it is good business. But the majority suffer losses. They are the ones who ultimately pay for the gains of the others” (von Mises, [1949] 2009, p. 423).

Another Austrian author, Rothbard (1963), nuances how inflation induces errors in economic calculation and investment. Thus, the expansion of the money supply not only raises prices generally but also distorts the structure of production by channeling resources into less sustainable investments that would not have been profitable in a non-inflationary environment. He notes: "The inflationary boom induces businessmen to make unsound investments, which are revealed as errors when the boom collapses" (Rothbard M. N., [1963] 2000, p. 82).

Finally, the redistributive effect of inflation can lead to an erosion of savings and capital accumulation, as individuals attempt to protect their purchasing power by investing in tangible and speculative assets rather than in long-term productive projects. Huerta de Soto (2012) describes how inflation discourages saving and productive investment, which in turn hampers sustainable economic growth: "The artificial expansion of credit induces systematic errors in investment decisions, leading to the malinvestment of resources and ultimately causing economic crises" (Huerta de Soto, [1998] 2012, p. 367).

6.3. New Interpretations

Recent interpretations of the 1603 inflationary episode in Spain, particularly from the perspective of Austrian Economic Theory, offer new insights into this historical phenomenon. The Austrian School, with its emphasis on monetary theory and business cycles, provides a unique framework for understanding the causes and consequences of this inflation.

From the Austrian perspective, the inflation of 1603 can be interpreted as a direct consequence of monetary expansion caused by the influx of precious metals from America. This expansion, not backed by a proportional increase in the production of goods and services, led to a widespread distortion of relative prices in the Spanish economy.

Mises (1912) argued that such artificial monetary expansion alters the price structure, sending erroneous signals to economic agents. As Mises states: "The increase in the quantity of money causes a fall in the objective exchange value of money" (Mises, 1912, p. 240). This misallocation of resources and unsustainable long-term investments aligns with the observed economic distortions in XVIIth century Spain.

The Austrian Business Cycle Theory (ABCT), developed by Mises and refined by Hayek, provides a framework for understanding the boom-bust cycle that characterized the Spanish economy of the period. According to this theory, artificial monetary expansion leads to an unsustainable boom phase, inevitably followed by a recession.

Hayek (1931) explains: "The artificial lowering of the rate of interest stimulates the production of capital goods at the expense of consumption goods" (Hayek, 1931, p. 89). In the context of 1603, the abundance of precious metals acted similarly to credit expansion, encouraging investments that did not reflect the true time preferences of economic agents.

In the case of 1603, the first recipients of the new precious metals (such as the Crown, merchants, and bankers) benefited at the expense of those who received the new money later, such as wage workers and farmers. This uneven distribution of inflationary effects exacerbated social inequalities and economic distortions.

Austrian economists would also point out how government policies, such as currency devaluation and tax increases, exacerbated economic problems. Rothbard (1963), argues: "Government intervention in money can only lead to distortions and harm" (Rothbard, 1963, p. 56). These interventions, intended to alleviate the symptoms of inflation, aggravated the situation by further distorting prices and economic incentives. The Spanish government's attempts to manipulate the currency and control prices likely contributed to the prolonged nature of the economic crisis.

Thus, the Austrian interpretation of the 1603 inflationary episode offers valuable insights for understanding modern economic phenomena. It highlights the importance of sound monetary policy and the dangers of artificial credit expansion. The analysis of Cantillon Effects provides a framework for understanding the uneven impacts of inflation on different social and economic groups, a phenomenon still relevant in contemporary economies. Moreover, this interpretation challenges traditional narratives that focus solely on the quantity of money in circulation. It emphasizes the importance of the structure of production and the role of time preference in economic decision-making, offering a more nuanced understanding of inflationary processes.

While the Austrian perspective provides valuable insights, it is important to note its limitations. Critics argue that the Austrian School's emphasis on monetary factors may oversimplify the complex social and political dynamics of 17th century Spain. Additionally, the application of modern economic theory to historical events requires careful consideration of the different institutional and technological contexts. In conclusion, the Austrian interpretation of the 1603 inflationary episode in Spain offers a fresh perspective on this historical event. By focusing on monetary expansion, price distortions, and the unintended consequences of government intervention, it provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the complex economic dynamics of the period. This approach not only enhances our understanding of historical events but also offers valuable lessons for contemporary economic policy and analysis.

7. Materials and Methods

This study employs a comprehensive methodological framework to analyze the inflationary episode of 1603 in Spain. The approach integrates historical data, statistical techniques, and theoretical interpretation to explore the impact of monetary expansion on raw material prices and real wages.

7.1. Data Sources

The primary dataset originates from American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain by Earl J. Hamilton (1954). This source includes tables covering the period 1501–1650, with detailed records of precious metal imports, price indices for raw materials, and real wage data. However, the dataset had limitations, such as missing data points. Therefore, the study focused on the period 1601–1650, where data were more complete. Missing values, such as the Andalusia price index for 1621, were estimated using a moving average based on surrounding years.

7.2. Data Normalization

To ensure comparability, all data were normalized to a base year of 1601. For details on the normalization process, refer to the Methodology section.

7.3. Aggregated Totals

For aggregated totals in

Table 2, regional indices were computed as arithmetic averages across Andalusia, Old Castile, New Castile, and Valencia. Due to the absence of accurate regional weights (e.g., population or production shares), arithmetic averages were applied to approximate overall trends.

7.4. Statistical Analysis

The study utilized descriptive statistics to identify trends and patterns in real wages, raw material prices, and precious metal imports. Regression models were applied to evaluate:

The impact of precious metal imports on raw material prices.

The relationship between raw material prices and real wages.

The combined effects of monetary expansion on living standards.

Significance was assessed using-values, and explanatory power was measured via the coefficient of determination. The statistical analysis was performed using Python, employing libraries such as NumPy and pandas for data processing and statsmodels for regression modeling.

7.5. Availability of Data

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The processed tables and Python scripts used for statistical analysis will also be made available in a public repository prior to publication.

8. Conclusions

8.1. Summary of Findings

First, the massive influx of precious metals expanded the money supply without a proportional increase in the production of goods and services. This imbalance resulted in a sustained rise in prices, known as the "Price Revolution." The inflation that ensued particularly affected local economies, destabilising prices and widening the gap between the rich and the poor. The agricultural and manufacturing sectors were especially impacted, facing volatile prices and fluctuating demand that complicated economic planning.

Furthermore, inflation exacerbated existing social inequalities. While the elites, including the nobility and clergy, managed to protect their wealth and maintain their status, the lower classes and peasants experienced a significant decline in their purchasing power. Urban workers' wages did not rise at the same pace as prices, leading to a reduction in their quality of life and an increase in poverty and the marginalisation of large sectors of the population.

The Crown’s response to these economic challenges included the devaluation of the currency and an increasing reliance on public debt. These inefficient fiscal policies aggravated the inflationary situation, creating a cycle of inflation and debt that weakened the Spanish economy in the long term. The issuance of debased currency and other attempts to finance the Crown’s expenditures without adequate structural reforms resulted in greater economic instability.

Moreover, the inflation and inadequate fiscal policies had significant political repercussions. The growing social discontent stemming from the loss of purchasing power and the rise in inequalities contributed to internal tensions and social conflicts. These tensions weakened the central power of the monarchy and limited its capacity to respond effectively to both internal and external challenges.

On the other hand, the understanding of the inflationary episode of 1603 has been enriched by multiple historiographical approaches that highlight both monetary and structural factors. Contemporary research suggests that the interaction between the influx of precious metals, fiscal policies, and military conflicts was crucial to the development of inflation. This multidimensional analysis allows for a more comprehensive view of how these interrelated factors shaped the economic and social landscape of Golden Age Spain.

In summary, the inflationary episode of 1603 in Spain was not merely a monetary phenomenon but also the result of a series of complex interactions among the economy, society, and politics of the time. The lessons learned from this period provide a deeper understanding of how economic policies and external circumstances can significantly influence a nation's stability and development.

8.2. Lessons For The Present

The hyperinflation of 1603 in Spain, as detailed in this article, was predominantly caused by the massive influx of precious metals from America, resulting in a significant increase in the money supply without a corresponding rise in production. This contrasts with modern inflationary episodes, such as those analyzed by Van Riet (2017), where inflation is often linked to expansive monetary policies and fiscal imbalances within a complex financial framework. While inflation in the 17th century primarily affected the economy through rising prices of basic goods, contemporary inflation dynamics are more closely related to financial stability and the security of sovereign assets in the context of the Eurozone.

Furthermore, the analysis by Purificato and Astarita (2015) regarding the imbalances in the TARGET2 system during the European sovereign debt crisis highlight the importance of central bank liquidity and confidence in economic and monetary stability. Although the circumstances differ, both situations underscore the critical role of confidence in the financial system and the careful management of monetary policy to avoid inflationary crises.

Lastly, Hsing’s (2015) study on the yields of Spanish government bonds during periods of modern economic crisis provides an example of how inflation expectations can influence financial markets and the economy at large. This analysis is particularly relevant for understanding how expectations and perceptions can amplify the effects of inflation.

By considering these contemporary studies, it becomes apparent that while the underlying mechanisms of inflation and their impact on the economy may vary across historical contexts, the importance of well-managed monetary policy and confidence in the financial system remains constant. This analysis not only clarifies historical inflationary dynamics but also offers valuable insights for contemporary and future monetary policy.

8.3. Final Reflection

The analysis of the inflationary episode of 1603 in Spain through the lens of Austrian economic theory not only sheds light on a complex historical period but also offers valuable lessons for contemporary economic policy. History, with its wealth of events and trends, acts as a natural laboratory where the effects of various economic policies can be observed in real time.

Firstly, the Spanish experience of the 17th century underscores the importance of monetary stability. The massive importation of precious metals, without a corresponding increase in the production of goods and services, triggered sustained inflation that destabilized the economy. Today, this lesson is especially relevant in the context of expansive monetary policies and prolonged low interest rates. The creation of money without real backing in the productive economy can lead to speculative bubbles and economic imbalances, similar to those observed during the Price Revolution in Spain.

Moreover, the Spanish case highlights the risks associated with financing government expenditures through currency devaluation and excessive indebtedness. The issuance of low-quality currency and the increase in public debt to finance wars and other expenditures, although immediate solutions, had devastating long-term effects. Today, economies must be cautious with excessive public debt and maintain fiscal discipline to avoid the temptation of resorting to inflationary solutions to resolve financial problems.

Another crucial aspect is the relationship between fiscal policy and economic inequality. The disproportionate tax burden on the lower classes and peasants, combined with the lack of wage adjustments in line with inflation, exacerbated social and economic inequalities during Spain's Golden Age. Currently, fiscal policies must be designed to be equitable and consider their distributive impacts. Measures to protect the purchasing power of wages are essential to prevent inflation from eroding the well-being of the most vulnerable sectors of society.

Finally, the rigidity of social and economic structures also played a role in prolonging and exacerbating the inflationary crisis in Spain. Restrictions on land ownership and the lack of technological innovation limited the economy's capacity to respond to changes in supply and demand. In today's world, fostering innovation, economic flexibility, and social mobility are fundamental to creating resilient economies that can adapt quickly to changes and minimise the negative impacts of crises.

Therefore, it is crucial to emphasise that the hyperinflation of 1603 in Spain was not an economic cycle in the classical Austrian sense of credit expansion above real available savings. Instead, the inflation observed during this period consisted of a price increase directly caused by the massive increase in the money supply due to the importation of precious metals from America. According to Austrian theory, economic cycles are triggered by credit expansion that distorts the structure of capital and leads to poor investments that eventually result in recessions. However, in the case of the inflation of 1603, the problem was the disproportionate money supply relative to the production of goods and services.

The inflation resulting from an increase in the money supply, as observed in 17th-century Spain, led to a series of unprecedented economic and social distortions. This distinction is essential for understanding that not all inflationary crises arise from the same economic mechanisms, and policies to address them must be tailored according to their specific causes. The economic history of Spain during this period reminds us of the importance of carefully managing monetary policy to avoid the disasters associated with uncontrolled inflation.

In summary, the study of the inflationary episode of 1603 not only enriches our historical understanding but also offers valuable lessons for the formulation of modern economic policies. Monetary stability, fiscal discipline, equity in fiscal policy, and structural flexibility are fundamental pillars for preventing and mitigating the effects of economic crises. These principles should guide the decisions of policymakers to ensure sustainable and equitable growth in the contemporary world.