Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- «2016 European Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents - PubMed». Consultato: 26 gennaio 2025. [Online]. Disponibile su. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27467768/.

- J. T. Flynn et al., «Clinical Practice Guideline for Screening and Management of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents», Pediatrics, vol. 140, fasc. 3, p. e20171904, set. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Battistoni, F. Canichella, G. Pignatelli, A. Ferrucci, G. Tocci, e M. Volpe, «Hypertension in Young People: Epidemiology, Diagnostic Assessment and Therapeutic Approach», High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev, vol. 22, fasc. 4, pp. 381–388, dic. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. de Onis, A. W. Onyango, E. Borghi, A. Siyam, C. Nishida, e J. Siekmann, «Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents», Bull World Health Organ, vol. 85, fasc. 9, pp. 660–667, set. 2007. [CrossRef]

- G. V. Giuliana, G. Saggese, e C. Maffeis, «Diagnosi, trattamento e prevenzione dell’obesità del bambino e dell’adolescente», Area Pediatrica, vol. 18, fasc. 4, pp. 150–157, ott. 2017.

- P. K. Whelton et al., «2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines», Hypertension, vol. 71, fasc. 6, pp. e13–e115, giu. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Mancia, «2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)», Eur Heart J, vol. 34, fasc. 28, pp. 2159–2219, lug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Goulas I, Farmakis I, Doundoulakis I, Antza C, Kollios K, Economou M, Kotsis V, Stabouli S. Comparison of the 2017 American Academy of Pediatrics with the fourth report and the 2016 European Society of Hypertension guidelines for the diagnosis of hypertension and the detection of left ventricular hypertrophy in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2022 Feb 1;40(2):197-204. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Bonito P, Valerio G, Pacifico L, Chiesa C, Invitti C, Morandi A, et al. Impact of the 2017 blood pressure guidelines by the American Academy of Pediatrics in overweight/obese youth. J Hypertens. 2018; 36, 2018.

- E. Lurbe et al., «Impact of ESH and AAP hypertension guidelines for children and adolescents on office and ambulatory blood pressure-based classifications», Journal of Hypertension, vol. 37, fasc. 12, p. 2414, dic. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, Elvira; Di Monaco, Silvia; Pappaccogli, Marco; Eula, Elisabetta; Fasano, Chiara; Masera, Guglielmo; Rabbone, Ivana; Rabbia, Franco; Veglio, Franco. IMPACT OF 2017 AAP AND 2016 ESH GUIDELINES ON PAEDIATRIC HYPERTENSION PREVALENCE. Journal of Hypertension 39(): p e188, April 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. K. Aksoy, D. Yapar, N. S. Koyun, e Ç. S. Doğan, «Comparison of ESHG2016 and AAP2017 hypertension guidelines in adolescents between the ages of 13 and 16: effect of body mass index on guidelines», Cardiol Young, vol. 32, fasc. 1, pp. 94–100, gen. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lissau, «Body mass index and overweight in adolescents in 13 European countries, Israel, and the United States», Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, vol. 158, fasc. 1, pp. 27–33, gen. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Kvaavik E, Tell GS, Klepp KI. Predictors and tracking of body mass index from adolescence into adulthood: follow-up of 18 to 20 years in the Oslo Youth Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003 Dec;157(12):1212-8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.12.1212. PMID: 14662578.«Predictors and tracking of body mass index from adolescence into adulthood: follow-up of 18 to 20 years in the Oslo Youth Study - PubMed».

- C. J. Rudolf et al., «Rising obesity and expanding waistlines in schoolchildren: a cohort study», Arch Dis Child, vol. 89, fasc. 3, pp. 235–237, mar. 2004. [CrossRef]

- « Bowman SA, Gortmaker SL, Ebbeling CB, Pereira MA, Ludwig DS. Effects of fast-food consumption on energy intake and diet quality among children in a national household survey. Pediatrics. 2004 Jan;113(1 Pt 1):112-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Pediatrics Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee, «Policy statement: organizational principles to guide and define the child health care system and/or improve the health of all children», Pediatrics, vol. 113, fasc. 5 Suppl, pp. 1545–1547, mag. 2004.

- S. Wiehe, H. Lynch, e K. Park, «Sugar high: the marketing of soft drinks to America’s schoolchildren», Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, vol. 158, fasc. 3, pp. 209–211, mar. 2004. [CrossRef]

- « Muntner P, He J, Cutler JA, Wildman RP, Whelton PK. Trends in blood pressure among children and adolescents. JAMA. 2004 ;291(17):2107-13. 5 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn JT, Alderman MH. Characteristics of children with primary hypertension seen at a referral center. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005 Jul;20(7):961-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. M. Sorof et al., «Cardiovascular risk factors and sequelae in hypertensive children identified by referral versus school-based screening», Hypertension, vol. 43, fasc. 2, pp. 214–218, feb. 2004. [CrossRef]

- R. Daniels, «Is there an epidemic of cardiovascular disease on the horizon?», J Pediatr, vol. 134, fasc. 6, pp. 665–666, giu. 1999. [CrossRef]

- Wing YK, Hui SH, Pak WM, Ho CK, Cheung A, Li AM, Fok TF. A controlled study of sleep related disordered breathing in obese children. Arch Dis Child. 2003 Dec;88(12):1043-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilleminault, K. Li, A. Khramtsov, L. Palombini, e R. Pelayo, «Breathing patterns in prepubertal children with sleep-related breathing disorders», Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, vol. 158, fasc. 2, pp. 153–161, feb. 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscemi S, Giordano C. Physical activity and cardiovascular prevention: Is healthy urban living a possible reality or utopia? Eur J Intern Med. 2017 May;40:8-15 Epub 2017 Feb 16. PMID: 28215975.«Physical activity and cardiovascular prevention: Is healthy urban living a possible reality or utopia? - PubMed». [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocchini AP, Katch V, Kveselis D, Moorehead C, Martin M, Lampman R, Gregory M. Insulin and renal sodium retention in obese adolescents. Hypertension. 1989 Oct;14(4):367-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- G. Kolterman, J. Insel, M. Saekow, e J. M. Olefsky, «Mechanisms of insulin resistance in human obesity: evidence for receptor and postreceptor defects», J Clin Invest, vol. 65, fasc. 6, pp. 1272–1284, giu. 1980. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Reaven, H. Chang, B. B. Hoffman, e S. Azhar, «Resistance to insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in adipocytes isolated from spontaneously hypertensive rats», Diabetes, vol. 38, fasc. 9, pp. 1155–1160, set. 1989. [CrossRef]

- S. Freedman, W. H. Dietz, S. R. Srinivasan, e G. S. Berenson, «The relation of overweight to cardiovascular risk factors among children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study», Pediatrics, vol. 103, fasc. 6 Pt 1, pp. 1175–1182, giu. 1999. [CrossRef]

- Reaven GM, Ho H, Hoffmann BB. Somatostatin inhibition of fructose-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 1989 Aug;14(2):117-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- « Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y. Metabolic syndrome: clinical concept and molecular basis. Ann Med. 2007;39(7):482-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishi S, Teixido-Tura G, Ning H, Venkatesh BA, Wu C, Almeida A, Choi EY, Gjesdal O, Jacobs DR Jr, Schreiner PJ, Gidding SS, Liu K, Lima JA. Cumulative Blood Pressure in Early Adulthood and Cardiac Dysfunction in Middle Age: The CARDIA Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Jun 30;65(25):2679-87. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aatola H, Magnussen CG, Koivistoinen T, Hutri-Kähönen N, Juonala M, Viikari JS, Lehtimäki T, Raitakari OT, Kähönen M. Simplified definitions of elevated pediatric blood pressure and high adult arterial stiffness. Pediatrics. 2013 Jul;132(1):e70-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

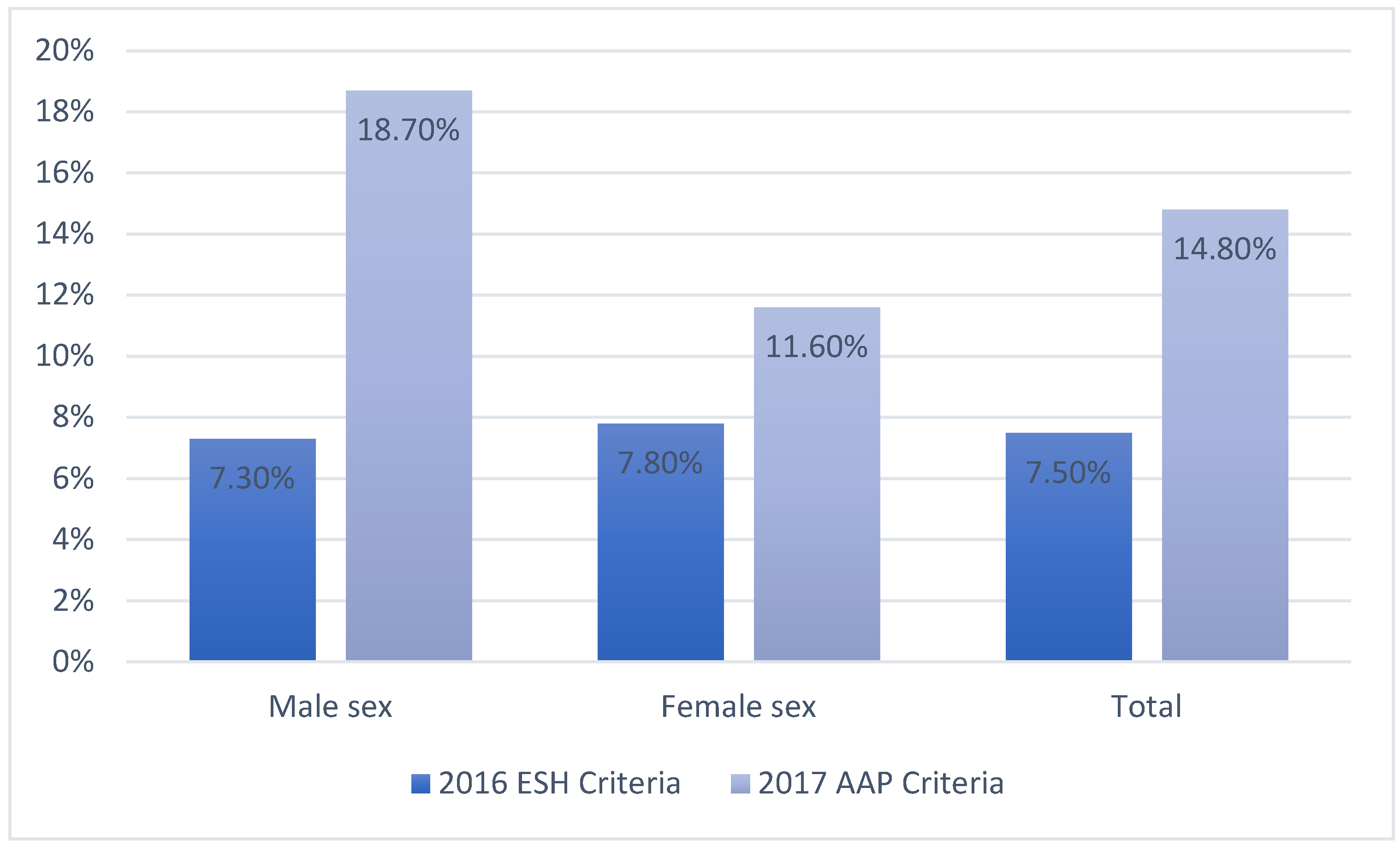

| 2016 ESH Criteria | 2017 AAP Criteria | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL (n=1301) | Increased BP(n=99) | Normal BP (n=1202) | p | Increased BP (n=195) | Normal BP (n=1122) | p | |

| Age (years) | 15.6 ± 1.7 | 16.6 ± 1.55 | <0.001 | 16.8 ± 1.7 | 16.5 ± 1.6 | 0.006 | |

| Male sex.n (%) | 46 (46) | 541 (45) | 0.753 | 110 (56) | 477 (43) | <0.001 | |

| Height (cm) | 168.9 ± 9.6 | 168.7 ± 9.1 | 0.443 | 171 ± 9.3 | 168.2 ± 9 | <0.001 | |

| Weight (kg) | 65.7 ± 13.8 | 61.3 ± 11.8 | <0.001 | 69.2 ± 14 | 60.3 ± 11 | <0.001 | |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 23 ± 3.4 | 21.5 ± 3.2 | <0.001 | 23.4 ± 3.7 | 21.2 ± 3 | <0.001 | |

| Overweight, n(%) | 39 (39.4) | 202 (16.8) | <0.001 | 66 (33.8) | 175 (15.5) | <0.001 | |

| Obesity, n (%) | 11 (11.1) | 35 (2.9) | <0.001 | 23 (11.8) | 23 (2) | <0.001 | |

| 2016 ESH Criteria | 2017 AAP Criteria | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total(n=1301) | Increased BP(n=99) | Normal BP (n=1202) | p | Increased BP (n=195) | Normal BP (n=1122) | P | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 114 ± 12 | 132±15 | 112±11 | <0.001 | 16.8 ± 1.7 | 16.5 ± 1.6 | 0.006 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 46 (46) | 541 (45) | 0.753 | 110 (56) | 477 (43) | <0.001 | |

| HR (bpm) | 168.9 ± 9.6 | 168.7 ± 9.1 | 0.443 | 171 ± 9.3 | 168.2 ± 9 | <0.001 | |

| Total | Increased BP | Normal BP | P | Increased BP | Normal BP | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 ESH | 2017 AAP | ||||||

| Current smokers, n (%) | 203 (15) | 13 (13) | 190 (16) | 0.56 | 35 (18) | 168 (15) | 0.284 |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 267 (21) | 9 (9) | 258 (21) | 0.03 | 42 (25) | 227(20) | 0.7 |

| Drugs consumption, n (%) | 88 (7) | 2 (2) | 86 (7) | 0.058 | 17 (9) | 71 (6) | 0.2 |

| Regular physical activity, n (%) | 192 (15) | 8 (8) | 185 (15) | 0.055 | 34(17) | 163 (15) | 0.32 |

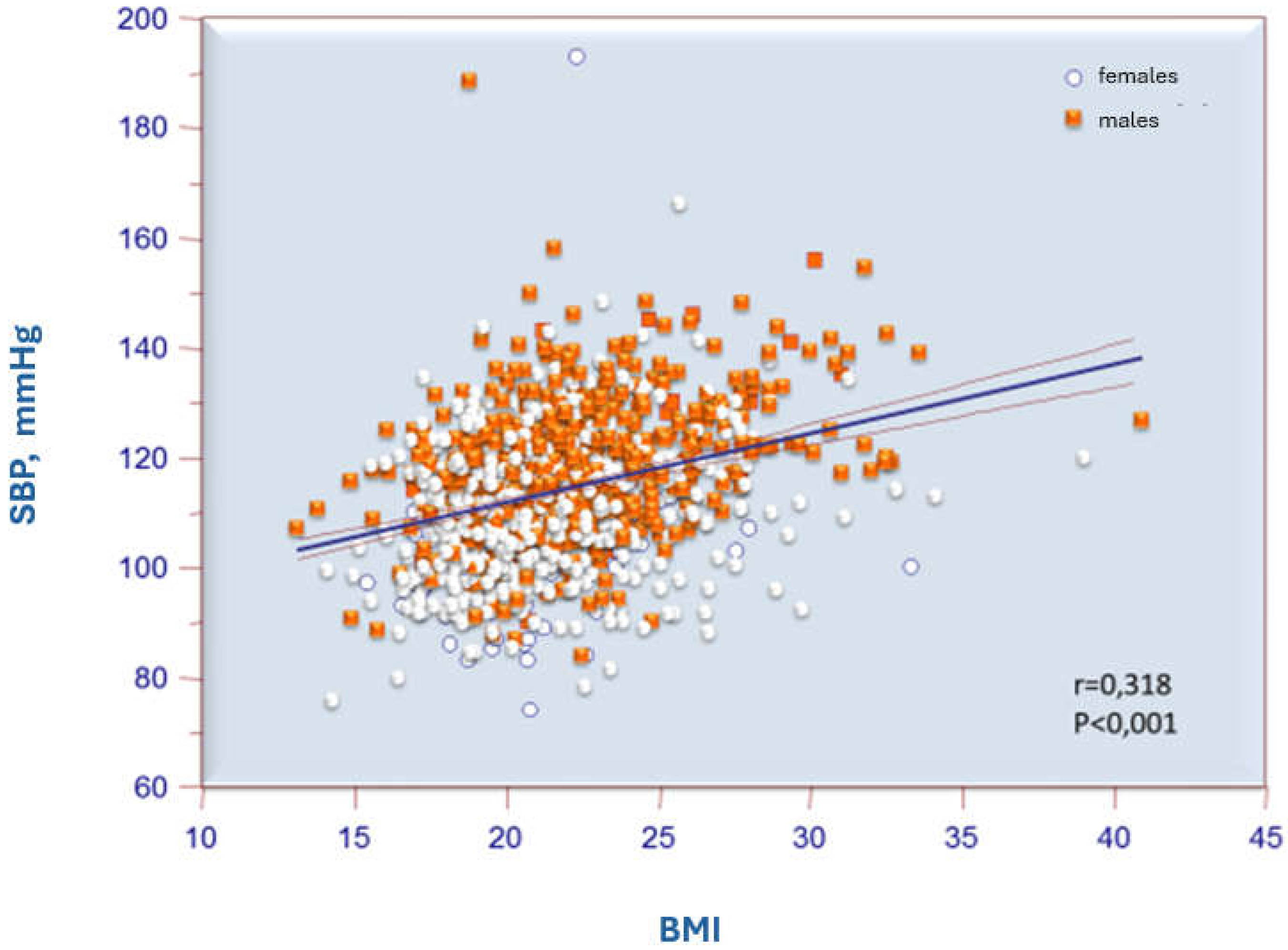

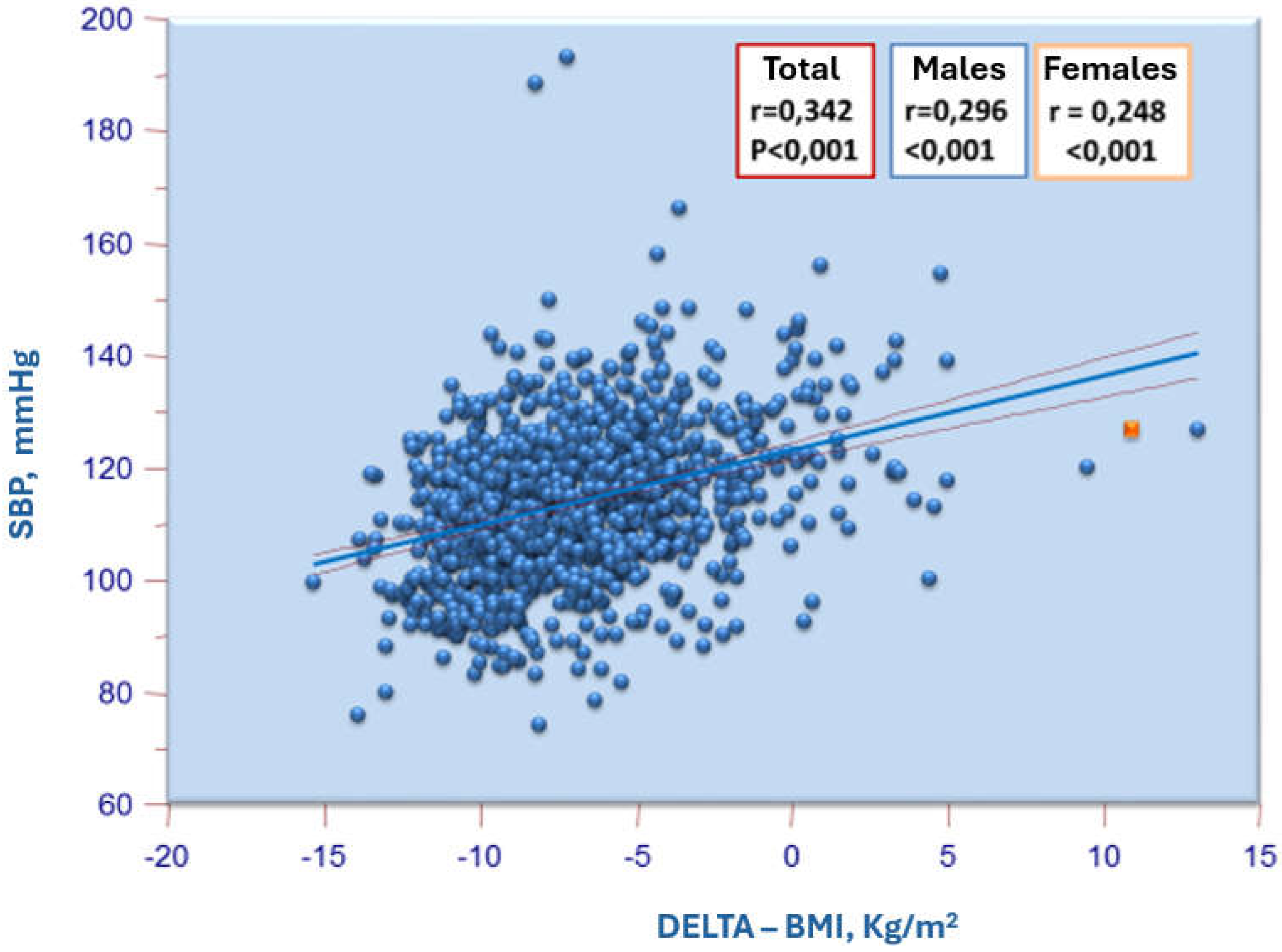

| Total | Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP | DBP | SBP | DBP | SBP | DBP | ||

| Height. cm | r | 0.321 | 0.02 | 0.233 | 0.038 | 0.089 | 0.039 |

| p | <0.001 | 0.47 | <0.001 | 0.362 | 0.018 | 0.305 | |

| Weight. Kg | r | 0.432 | 0.102 | 0.398 | 0.15 | 0.256 | 0.099 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.009 | |

| BMI | r | 0.318 | 0.116 | 0.338 | 0.157 | 0.226 | 0.087 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.023 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).