1. Introduction

Glomerular podocytes are highly differentiated epithelial cells that line the urinary side of the glomerular basement membrane of the kidney and play a key role in blood filtration. Podocytes on capillaries form complex processes that interdigitate with those of neighbouring podocytes to form and maintain glomerular slit diaphragms [

1].

Glutamate is a major intercellular transmitter in the nervous system that activates ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors [

2]. Endocrine tissues, such as the pineal gland and pancreatic islets, also use glutamate to transmit signals [

3,

4]. Glomerular podocytes express functional ionotropic NMDA receptors and metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 (mGluR1) and mGluR5 receptors [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Stimulation of these receptors is involved in the formation and maintenance of slit diaphragms and podocyte injury [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], indicating that the glutamatergic system in podocytes has physiological importance.

The glutamatergic system consists of the release, reception and termination of glutamate signals. To transmit glutamate signals, glutamate must be taken up by vesicular-type glutamate transporters (VGLUTs) and stored in synaptic vesicles. There are three VGLUT isoforms, VGLUT1, VGLUT2 and VGLUT3 [

10]. All VGLUT isoforms are localised at synaptic vesicle membranes and commonly transport cytoplasmic glutamate into vesicles using the membrane potential coupled with ATP hydrolysis by V-ATPase [

10]. VGLUT1 is expressed in podocytes [

11] and VGLUT3 is expressed in the kidney, suggesting that the kidney contains cells, including podocytes, which transmit glutamate signals [

12].

The ionotropic NMDA receptor in mature podocytes is involved in the progression of diabetic nephropathy [

8], and NMDA receptor antagonism in cultured podocytes alters cytoskeletal remodeling and the integrity of the glomerular filtration barrier [

13]. Metabotropic mGluR1 and mGluR5 are expressed in the foot processes of podocytes, and their activation improves albumin levels and apoptosis, which are processes that depend at least on cAMP [

5]. Thus, accumulating evidence suggests the existence of a glutamate signalling system in glomerular podocytes. However, little is known about its molecular mechanisms. In this study, we investigated the functional expression of VGLUT3 in differentiated mouse podocytes (MPCs) and observed that VGLUT3 largely colocalised with VGLUT1 and VAMP2, as well as the synaptic vesicle marker proteins synaptophysin 1 and synapsin 1. Furthermore, immuno-electron microscopy showed that VGLUT3 was present on the membrane of vesicle-like structures. Differentiated MPCs secreted glutamate into extracellular space upon the stimulation with pilocarpine or by depolarization with KCl. Depletion of VGLUT3 in differentiated MPCs decreased the KCl-induced glutamate release. These results suggest that podocytes can release glutamate in a VGLUT3-dependent manner and VGLUT3 is likely important for regulating the glomerular slit diaphragm.

2. Results

2.1. VGLUT3 Is Present in Glomerular Podocytes

To investigate the expression of VGLUT1 and VGLUT3 in rat podocytes, immunohistochemistry was performed. Consistent with a previous report [

11], VGLUT1 immunoreactivity was clearly observed in glomeruli, which localise at the periphery of glomerular capillaries (

Figure 1A). VGLUT3 was also observed in glomeruli, and the staining pattern was similar to that of VGLUT1 (

Figure 1B). Furthermore, both VGLUT1 and VGLUT3 were colocalised with synaptopodin, a podocyte marker, indicating their presence in glomerular podocytes (

Figure 1).

2.2. VGLUT1 and VGLUT3 Are Co-Expressed in Differentiated MPCs

Given the presence of VGLUT1 and VGLUT3 proteins in rat podocytes, we next examined their expression in an MPC line. MPCs can be differentiated by changing the culture temperature from 33°C to 37°C, along with the removal of γ-interferon from the culture medium [

14]. First, we examined the mRNA expression of VGLUT1, VGLUT2 and VGLUT3 in MPCs by real-time PCR. Both VGLUT1 and VGLUT3 mRNAs were detected in undifferentiated and differentiated MPCs, whereas VGLUT2 mRNA was undetectable under our experimental conditions. Furthermore, VGLUT3 mRNA was markedly increased during differentiation (

Figure 2A). Western blotting analyses detected expression of VGLUT1 and VGLUT3 proteins in homogenates prepared from undifferentiated or differentiated MPCs (

Figure 2B,

Figure S1). Next, the localisation of VGLUT1 or VGLUT3 in MPCs was examined by double immunofluorescence. In undifferentiated and differentiated cells, VGLUT1 and VGLUT3 were present as punctata scattered throughout the cell, and the two proteins significantly colocalised (

Figure 2C and D). The colocalisation rate of VGLUT3 with VGLUT1 was 30.3 ± 1.0 % (n=33 cells) in undifferentiated cells and 37.0 ± 0.62 % (n=33 cells) in differentiated cells (

Figure 2E).

2.3. VGLUT3 Colocalises with Synaptic Vesicle Marker Proteins in Differentiated MPCs

In brain, VGLUT3 is localised at synaptic vesicles and is involved in the exocytosis of transmitters [

10]. Next, the colocalisation of VGLUT3 with vesicular exocytosis-related proteins, namely vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2), synaptophysin 1 or synapsin 1, were determined in differentiated MPCs. As shown in

Figure 3A–C, these proteins showed the same punctate pattern as VGLUT3 and were colocalised with VGLUT3. The colocalisation rate of VGLUT3 with these proteins was 30–40% (

Figure 3D). These results suggest that vesicular trafficking using VGLUT3-containing synaptic-like vesicles takes place in differentiated MPCs.

2.4. VGLUT3 Associates with Synaptic-Like Vesicles in Differentiated MPCs

Ultrastructural observation of differentiated MPCs by transmission microscopy revealed that podocytes contain a considerable number of clear, small vesicles that are 100–150 nm in diameter (

Figure 4A). By immunoelectron microscopy, VGLUT3 was present on the membrane of these vesicles (

Figure 4B). Taken together, these results indicate that podocytes express VGLUT3-positive synaptic-like vesicles, which could contain glutamate that is released into the intercellular space by exocytosis upon some kind of stimulus.

2.5. VGLUT3 Depletion in Differentiated MPCs Reduces Glutamate Release into the Intracellular Space

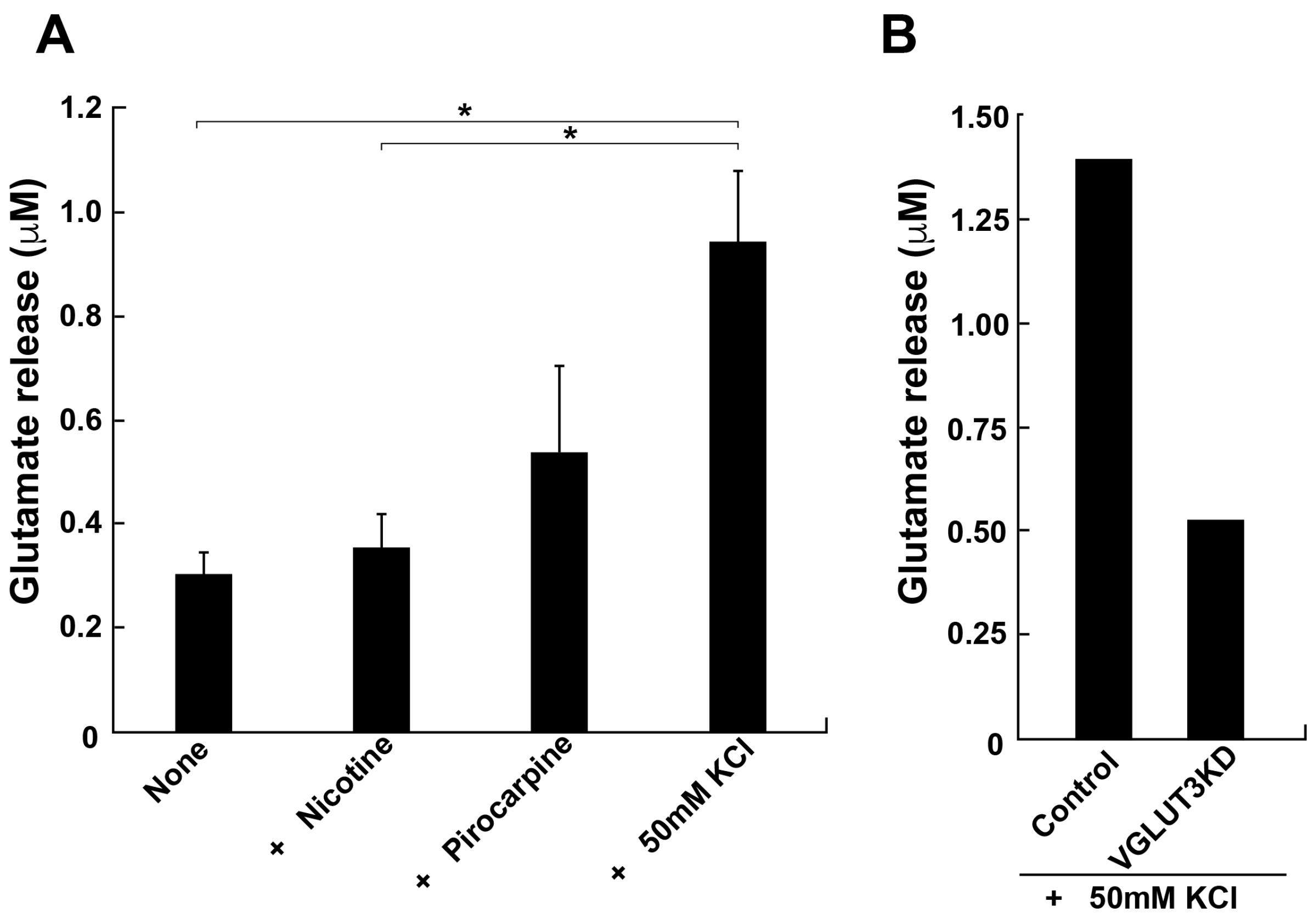

Since our results strongly suggested the presence of glutamate transport and release in podocytes, we directly measured glutamate release from differentiated MPCs. The glutamate concentration in the culture medium was determined by HPLC after 5 min stimulation of the cells with pilocarpine or high K

+. Stimulated podocytes released a considerable amount of glutamate, 0.54 ± 0.17 or 0.94 ± 0.14 µM, following the addition of pilocarpine or high K

+, respectively (

Figure 5A). By contrast, nicotine, an agonist for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, had little effect on the release. These results are consistent with a previous report [

11]. Finally, we examined whether the expression of VGLUT3 is essential for the glutamate release from differentiated MPCs, utilising RNA interference (RNAi) to reduce expression of VGLUT3. Immunofluorescence revealed that expression of VGLUT3 was selectively knocked down by approximately 50% compared with control cells (

Figure 2S). High K

+-dependent glutamate release was reduced by approximately 60% compared with control MPCs (

Figure 5B). These results suggest that VGLUT3 is functionally expressed by MPCs and is involved in glutamate release into the intracellular space.

3. Discussion

In the current study, we investigated the expression, intracellular localisation and possible roles of VGLUTs in conditionally immortalised mouse podocytes (MPCs). We demonstrated the expression of VGLUT1 and VGLUT3 in MPCs as well as renal glomerular podocytes (

Figure 1 and 2). In differentiated MPCs, VGLUT3 was colocalised with synaptic vesicle markers VGLUT1, VAMP2, synaptophysin 1 and synapsin 1 (

Figure 2). Furthermore, the presence of VGLUT3 on the membrane of intracellular vesicles was indicated by immunoelectron microscopy (

Figure 4). These results suggested podocytes can release glutamate into extracellular space through vesicle-mediated exocytosis. Finally, we demonstrated that MPCs can release glutamate upon depolarization with a high concentration of K

+ or the muscarinic agonist pilocarpine, but not nicotine. RNAi-mediated depletion of VGLUT3 reduced KCl-dependent glutamate release (

Figure 5). Taken together, these results suggest that VGLUT3 is functionally expressed in differentiated MPCs, and it might be involved in glutamatergic regulation of podocyte functions.

VGLUT3 was identified by several groups in 2002 as a third VGLUT isoform [

12,

15,

16,

17] and characterised in brain and neurons in comparison with VGLUT1 and VGLUT2. In humans, VGLUT3 shares approximately 80% amino-acid homology and has almost identical functional properties such as glutamate uptake and substrate specificity as VGLUT1 and VGLUT2, suggesting that VGLUT3 contributes to exocytotic glutamate release. Few studies have investigated VGLUTs in non-neuronal cells. Although VGLUT3 mRNA is present in liver and kidney as well as brain [

12], the expression of VGLUT3 at a protein level was not known before the current study. We systematically investigated VGLUT expression in podocytes by quantitative PCR, Western blot analysis, and immunostaining, and demonstrated that VGLUT1 and VGLUT3 are highly expressed in podocytes. Approximately 30–40% of VGLUT3 expression was colocalised with that of the synaptic vesicle marker proteins VAMP2, synaptophysin 1, and synapsin 1 (

Figure 3), and ultrastructurally, VGLUT3 was present on the membrane of intracellular vesicles (

Figure 4). These findings suggest that at least a subpopulation of VGLUT3 is engaged in the exocytosis of glutamate. Other subpopulations of VGLUT3 might be involved in glutamate storage or an as-yet-unknown “novel mode” of glutamate signaling, which is proposed in neurons [

12]. Since an approximately 50% reduction of VGLUT3 protein reduced KCl-induced glutamate secretion by 60% (

Figure 5), VGLUT3 is molecule responsible for the majority of this glutamate secretion.

In this study, pilocarpine, a muscarinic acetylcholine receptor agonist, stimulated glutamate release from cultured differentiated podocytes, consistent with a previous report [

11]. In addition, depolarizing stimuli also triggered glutamate release (

Figure 5). Pilocarpine increases intracellular Ca

2+ concentration [

18]. The depolarization stimuli open N-type voltage-dependent calcium channels, which are present in podocytes [

19]. Since both pilocarpine and depolarization increased the intracellular calcium concentration, it is conceivable that muscarinic acetylcholine receptors and N-type voltage-dependent calcium channels are involved in VGLUT3-dependent glutamate release. Further research is required to clarify the details of VGLUT3-dependent glutamate release, including the identification of the physiological stimuli that promote glutamate release.

Previous reports suggest that glutamate signaling is essential for the morphological regulation of the slit diaphragm formed by the interdigitation of foot processes of neighbouring podocytes and apoptosis [

5,

8,

9]. In mature podocytes, the ionotropic NMDA receptor is involved in the progression of diabetic nephropathy [

8]. Furthermore, metabotropic mGluR1 and mGluR5 are functionally expressed in differentiated podocytes. In particular, mGluR1 and mGluR5 are expressed in the foot processes of podocytes, and their activation improves albumin levels and apoptosis, which are processes that depend on cAMP [

5]. Thus, glutamate signaling and the signal reception machinery expressed by mature podocytes are crucial for controlling blood filtration function, and VGLUT3 is an essential component of this machinery.

In this study, we found that podocytes themselves release glutamate via the activity of VGLUT3. Future studies are needed to clarify what stimuli cause glutamate release from podocytes, but the podocyte glutamatergic system will likely become important as a drug target for protecting podocytes from injury and improving proteinuria.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Antibodies and Reagents

Guinea pig polyclonal anti-vesicular glutamate transporter 3 (anti-VGLUT3) antibodies (cat# AB5421-I), rabbit polyclonal anti-synapsin1 antibodies (cat# AB1543P) and rabbit polyclonal anti-glutamate antibodies (cat# AB133) were purchased from Merck Millipore (Darmstadt, Germany). Rabbit polyclonal anti-synaptobrevin 2 (anti-VAMP2) antibodies (cat# 104202), rabbit polyclonal anti-synaptophysin1 antibodies (cat# 101002) and rabbit polyclonal anti-vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (anti-VGLUT1) antibodies (cat#135303) were purchased from Synaptic Systems GmbH (Göttingen, Germany). A mouse monoclonal antibody against beta-actin (cat# A5441) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). A mouse monoclonal antibody against synaptopodin (clone G1D4, cat# 65194) was purchased from PROGEN Biotechnic GmbH (Heidelberg, Germany). Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (cat# A21206) or Alexa Fluor 555- conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (cat# A31572), Alexa Fluor 555- conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (cat# A31570), and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies (cat# A11001) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-guinea pig IgG (cat# 706-546-148) and peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-guinea pig IgG (cat# 706-035-148) antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Baltimore, PA, USA). Ten nm gold-conjugated secondary antibodies (cat# EMGAG10) was purchased from BBI Solutions (ME, USA). Nicotine (cat#190671), pilocarpine hydrochloride (cat# 161-07201) and O-phthalaldehyde (cat# SS-7380) were purchased from Wako-Fujifilm CO. LTD. (Osaka, Japan). DL-TBOA (Threo-β-Benzyloxyaspartic acid, cat#1223) was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK).

4.2. Cell Culture

The conditionally immortalised mouse podocyte cell line (MPC) was cultured as described previously [

14]. Briefly, the cells were cultured on type I collagen-coated plastic dishes (cat# 356450; Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) in RPMI 1640 medium (cat# 189-02025; Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemicals Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (cat# 10100147, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin (cat# 15140122, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 50 U/ml mouse recombinant γ-interferon (cat# 315-05; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), and were maintained at 33°C and 5% CO

2. For differentiation, podocytes were cultured at 37°C in medium lacking γ-interferon for 7–14 days. Under these conditions, the cells stopped proliferating and became positive for synaptopodin expression.

4.3. siRNA-Mediated Interference and Transfection

The pre-annealed siRNA mixture for mouse VGLUT3 (cat# 4390771) was purchased from Ambion (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the negative control (cat# D0018101005) siRNAs were synthesised and purified by Dharmacon Inc. (Lafayette, CO, USA). The siRNAs targeting independent sequences of mouse VGLUT3 were mixed: oligo 1 sense, 5’-GGACAAAUGUGGAAUCAUU -3’. Scrambled RNA with no significant sequence homology to the mouse, rat or mouse VGLUT3 gene sequence was used as the negative control. Undifferentiated MPCs were transfected with the siRNAs using Lipofectamine RNAiMax reagent (cat# 13778-150, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cells were seeded either into 6-well plates coated with type I collagen (cat# 356400, Corning Inc.) at a density of 1 × 103 cells/well for for immunostaining experiments or a 10 cm diameter culture dish coated with type I collagen (cat #4020-010, AGC Techno Glass Co. Ltd., Shizuoka, Japan) at a density of 1 × 104 cells/dish for glutamate release.

Two days later, each well was incubated for 6 h with 150 pmol siRNA and 7.5 µl RNAiMax in Opti-MEM (cat#31985070, Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing γ-interferon. Each dish was incubated with 600 pmol siRNA and 35 µl RNAiMax in Opti-MEM containing γ-interferon. Subsequently, the transfection medium was replaced with fresh medium containing γ-interferon. After 72 h, a second transfection was performed, and the cells were cultured for another 72 h. It was confirmed that the siRNAs reduced the expression of VGLUT3 by approximately 50% (

Supplementary Figure S1). To enable differentiation, the cells were plated into new culture dishes and maintained in medium lacking γ-interferon at 37°C for 7 days.

4.4. Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was prepared from MPCs using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was generated using a PrimeScript RT master mix (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) with 1 µg of total RNA as the template. Quantitative PCR was carried out with specific forward and reverse primers at 0.25 µM and Luna universal qPCR master mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) in a 20 µl reaction volume using a QuantStudio3 PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reaction conditions included an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 60 s, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60°C for 30 s. The primer sets used for the detection of mouse Vglut1 (140 bp), mouse Vglut2 (142 bp), and mouse Vglut3 (124 bp) were as follows: 5´-TTGAAGAAGTGTTCGGCTTTGAGA-3´ and 5´-GTTGGTAGTGGACATTATGTGACGA-3´; 5´-AGCAAATTCTCTCAACAACTACAGTG-3´ and 5´-CTGAATCCTACTGCAAGCACCAA-3´; 5´-TTACGGCTGTGTCATGGGTGT-3´ and 5´-AGTCGTGGCTAGACGGCTTC-3´, respectively. The level of Vglut1-3 was evaluated relative to that of the housekeeping gene, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3pdh). The primer set used for the detection of mouse G3pdh (150 bp) was as follows: 5´-TGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTG-3´ and 5´-TTGCTGTTGAAGTCGCAGGAG-3´.

4.5. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on renal glomerular podocytes obtained from rats. Under sevoflurane anaesthesia, 7-week-old male Wister rats (Shimizu Laboratory Supplies Co., Kyoto, Japan) were perfusion-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and 20% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH7.4). The kidney was removed then cut into sections and fixed with the same fixative at 4°C for 16 h. The fixed kidney was cryoprotected with 18% sucrose and frozen sectioned at 8 µm thickness. Dissected kidney obtained from 2-day-old rats under sevoflurane anaesthesia was fixed in the same fixative and was frozen-sectioned at 8 µm thickness. The sections were double stained by immunofluorescence as described previously [

20].

4.6. Electron Microscopy

Pre-embedding immunoelectron microscopy of cultured podocytes was performed as described previously [

21]. Briefly, differentiated MPCs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH7.4 for 15 min, and then washed once. Cells were permeabilised with 0.25% saponin in 0.1 M phosphate buffer for 30 min. After incubation in blocking solution (1% bovine serum albumin and 10% goat serum in 0.1 M PB) for 15 min, samples were incubated with guinea pig polyclonal anti-VGLUT3 antibody (1:750) diluted in blocking solution at 4°C for 16 h, washed with 1% bovine serum albumin in 0.1 M phosphate buffer five times, incubated with 10 nm gold-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:50), and then fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer for 5 min. The samples were post-fixed with 0.5% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 90 min, dehydrated, and embedded in Epon 812 embedding resin (cat# 341; Nissin EM Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) to enable ultra-thin sectioning. The sections were observed with a Hitachi H-7650 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi High-Tech Corp., Tokyo, Japan). For conventional electron microscopy, cell specimens were immersed in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 2% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde for 16–18 h. Post-fixation was performed in 2% osmium tetroxide for 1.5 h. After washing with cacodylate buffer, the specimens were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol solutions and embedded in Spurr resin (Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA, USA). Then, 80-nm sections were prepared using an ultramicrotome (EM-UC7; Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany) and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Specimens were observed by transmission electron microscopy (H-7650, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

4.7. Fluorescent Microscopy

MPCs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained by immunofluorescence as described previously [

20]. VGLUT1, VGLUT3, synapsin 1, synaptophysin 1, VAMP2, or glutamate were visualised by double immunofluorescence. Samples were examined using a spinning disc confocal microscope system (X-Light confocal imager; Crestoptics S.p.A., Rome, Italy) combined with an inverted microscope (IX-71; Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and an iXon+ camera (Oxford Instruments, Oxfordshire, UK). The confocal system was controlled by MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). When necessary, images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS3 or Illustrator CS3 software.

4.8. Determination of Glutamate Release

Cultured cells (1 x 10

4 cells per 10 cm diameter dish) were washed three times with Ringer’s solution comprising 128 mM NaCl, 1.9 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH

2PO

4, 2.4 mM CaCl

2, 1.3 mM MgSO

4, 26 mM NaHCO

3, 3.3 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). After cells had been incubated in 5 ml of Ringer’s solution at 37°C, glutamate release was stimulated by the addition of the indicated stimulants or high K

+ Ringer’s solution (83 mM NaCl, 50 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH

2PO

4, 2.4 mM CaCl

2, 1.3 mM MgSO

4, 26 mM NaHCO

3, 3.3 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)). All medium contained 50 µM DL-TBOA, an inhibitor for Na

+-dependent glutamate transporter for decreasing of glutamate reuptake into podocyte. Aliquots (500 µl) of the incubation media were taken at specific times, and the amount of extracellular glutamate was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with precolumn O-phthalaldehyde derivatization, separation on a reverse-phase Resolve C18 column (4.6 x 150 mm) (cat#38144-31; Nacalai Tesque Inc., Kyoto, Japan), and fluorescence detection [

22].

4.9. Morphometry

To assess the colocalisation of VGLUT3 with VGLUT1, VAMP2, synaptophysin 1 or synapsin 1, immunostained cells were imaged, and the immunoreactivities in three randomly selected areas (25 µm2 each, total 75 µm2) per cell were measured using MetaMorph software. To determine the effect of VGLUT3 knockdown in MPCs, images of control or VGLUT3 siRNA-treated cells stained with an antibody against VGLUT3 were acquired at identical settings with a 60 × objective for cells. The average pixel intensities per cell were then measured using Image J software. To enable the fluorescence to be quantified, a background correction was performed before each measurement.

4.10. Ethics and Animal Use Statement

All experiments and protocols were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of Okayama University (OKU-2023112, Japan). All efforts were made to minimise animal suffering. Whole kidneys were removed from mice after euthanising.

4.11. Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed for statistical significance using KaleidaGraph software for Macintosh, version 4.1 (Synergy Software Inc., Essex Junction, VT, USA). Student’s t-tests were used to analyse two groups. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

5. Conclusions

Podocytes themselves release glutamate via the activity of VGLUT3. The podocyte glutamatergic system will likely become important as a drug target for protecting podocytes from injury and improving proteinuria.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Western blot analyses of VGLUT1 and VGLUT3 expression in undifferentiated and differentiated MPCs; Figure S2: The knockdown efficiency of VGLUT3 determined by immunofluorescence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Naoko Nishii, Jun Wada, Kohji Takei and Hiroshi Yamada; Investigation, Naoko Nishii, Tomoko Kawai, Hiroki Yasuoka, Tadashi Abe, Nanami Tatsumi, Yuika Harada, Takaaki Miyaji, Shunai Li, Moemi Tsukano, Masami Watanabe, Daisuke Ogawa and Hiroshi Yamada; Writing – original draft, Naoko Nishii, Tomoko Kawai, Jun Wada, Kohji Takei and Hiroshi Yamada. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (grant numbers 23H27170 to K. T, 20K08591 to H. Yamada), by Okayama University Central Research Laboratory, and by Ehime University Proteo-Science Center (PROS).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experiments and protocols were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of Okayama University (OKU-2024424). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering. After euthanizing mice, whole hearts were removed.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank to all people involved in Okayama University Central Research Laboratory for technical assistant. This work has been partly supported by Core-Facility at Okayama University (CFPOU DGP_653 and 654).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Pavenstädt, H., Kriz, W., and Kretzler, M. (2003) Cell biology of the glomerular podocyte. Physiol Rev 83, 253-307. [CrossRef]

- Flavell, S.W., Greenberg, M.E. (2008) Signaling mechanisms linking neuronal activity to gene expression and plasticity of the nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 31, 563-590. [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, R., Hayashi, M., Yatsushiro, S., Otsuka, M., Yamamoto, A., Moriyama, Y. (2003) Co-expression of vesicular glutamate transporters (VGLUT1 and VGLUT2) and their association with synaptic-like microvesicles in rat pinealocytes. J Neurochem. 84, 382-391. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M., Morimoto, R,, Yamamoto, A., Moriyama, Y. (2003) Expression and localization of vesicular glutamate transporters in pancreatic islets, upper gastrointestinal tract, and testis. J Histochem Cytochem. 51, 1375-1390. [CrossRef]

- Gu, L., Liang, X., Wang, L., Yan, Y., Ni, Z., Dai, H., Gao, J., Mou, S., Wang, Q., Chen, X., Wang, L., Qian, J. (2012) Functional metabotropic glutamate receptors 1 and 5 are expressed in murine podocytes. Kidney Int. 81, 458-468. [CrossRef]

- Puliti, A., Rossi, P.I., Caridi, G., Corbelli, A., Ikehata, M., Armelloni, S., Li, M., Zennaro, C., Conti, V., Vaccari, C.M., Cassanello, M., Calevo, M.G., Emionite, L., Ravazzolo, R., Rastaldi, M.P. (2011) Albuminuria and glomerular damage in mice lacking the metabotropic glutamate receptor 1. Am J Pathol. 178, 1257-1269. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M., Suh, J.M., Kim, E.Y., Dryer, S.E. (2011) Functional NMDA receptors with atypical properties are expressed in podocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 300, C22-32. [CrossRef]

- Roshanravan, H., Kim, E.Y. Stuart, Dryer, S.E. (2016) NMDA Receptors as Potential Therapeutic Targets in Diabetic Nephropathy: Increased Renal NMDA Receptor Subunit Expression in Akita Mice and Reduced Nephropathy Following Sustained Treatment With Memantine or MK-801. Diabetes 65, 3139-3150. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Wang, D., Shibata, S., Ji, T., Zhang, L., Zhang, R., Yang, H., Ma, L., Jiao, J. (2019) Group I metabotropic glutamate receptor activation induces TRPC6-dependent calcium influx and RhoA activation in cultured human kidney podocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 511, 374-380. [CrossRef]

- Pietrancosta, N., Djibo, M., Daumas, S., El Mestikawy, S., Erickson, J.D. (2020) Molecular, Structural, Functional, and Pharmacological Sites for Vesicular Glutamate Transporter Regulation. Mol Neurobiol. 57, 3118-3142. [CrossRef]

- Rastaldi, M.P., Armelloni, S., Berra, S., Calvaresi, N., Corbelli, A., Giardino, L.A., Li, M., Wang, G.Q., Fornasieri, A., Villa, A., Heikkila, E., Soliymani, R., Boucherot, A., Cohen, C.D., Kretzler, M., Nitsche, A., Ripamonti, M., Malgaroli, A., Pesaresi, M., Forloni, G.L., Schlöndorff, D., Holthofer, H., D'Amico, G. (2006) Glomerular podocytes contain neuron-like functional synaptic vesicles. FASEB J. 20, 976-978. [CrossRef]

- Fremeau, R.T. Jr, Burman, J., Qureshi, T., Tran, C.H., Proctor, J., Johnson, J., Zhang, H., Sulzer, D., Copenhagen, D.R., Storm-Mathisen, J., Reimer, R.J., Chaudhry, F.A., Edwards, R.H. (2002) The identification of vesicular glutamate transporter 3 suggests novel modes of signaling by glutamate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 99, 14488-14493. [CrossRef]

- Giardino, L., Armelloni, S., Corbelli, A., Mattinzoli, D., Zennaro, C., Guerrot, D., Tourrel, F., Ikehata, M., Li, M., Berra, S., Carraro, M., Messa, P., Rastaldi, M.P. (2009) Podocyte glutamatergic signaling contributes to the function of the glomerular filtration barrier. J Am Soc Nephrol. 20, 1929-1940. [CrossRef]

- Mundel, P., Reiser, J., and Kriz, W. (1997) Induction of differentiation in cultured rat and human podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol 8, 697-705. [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, M.K., Varoqui, H., Defamie, N., Weihe, E., Erickson, J.D. (2002) Molecular cloning and functional identification of mouse vesicularglutamate transporter 3 and its expression in subsets of novel excitatory neurons. J Biol Chem. 277, 50734-50748. [CrossRef]

- Gras, C., Herzog, E., Bellenchi, G.C., Bernard, V., Ravassard, P., Pohl, M., Gasnier, B., Giros, B.B., Mestikawy, S.E. (2002) A Third Vesicular Glutamate Transporter Expressed by Cholinergic and Serotoninergic Neurons. J Neurosci. 22, 5442–5451. [CrossRef]

- Takamori, S., Malherbe, P., Broger, C., Jahn, R. (2002) Molecular cloning and functional characterization of human vesicular glutamate transporter 3. EMBO Rep. 3, 798–803. [CrossRef]

- Dehaye, J.P., Winand, J., Poloczek, P., Christophe, J. (1984) Characterization of muscarinic cholinergic receptors on rat pancreatic acini by N-[3H]methylscopolamine binding. Their relationship with calcium 45 efflux and amylase secretion. J Biol Chem. 259, 294-300. [CrossRef]

- Bai, L., Sun, S., Sun, Y., Wang, F., Nishiyama, A. (2022) N-type calcium channel and renal injury. Int Urol Nephrol. 54, 2871-2879. [CrossRef]

- Makino, S.I., Shirata, N., Oliva Trejo, J.A., Yamamoto-Nonaka, K., Yamada, H., Miyake, T., Mori, K., Nakagawa, T., Tashiro, Y., Yamashita, H., Yanagita, M., Takahashi, R., Asanuma, K. (2021) Impairment of Proteasome Function in Podocytes Leads to CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 32, 597-613. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, H., Abe, T., Satoh, A., Okazaki, N., Tago, S., Kobayashi, K., Yoshida, Y., Oda, Y., Watanabe, M., Tomizawa, K., Matsui, H., and Takei, K. (2013) Stabilization of actin bundles by a dynamin 1/cortactin ring complex is necessary for growth cone filopodia. J Neurosci 33, 4514-4526. [CrossRef]

- Godel, H., Graser, T., Foldim, P., Pfaender, P., Fuerst, P. (1984) Measurement of free amino acids in human biological fluids by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatography 297, 49-61. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).