Submitted:

14 February 2025

Posted:

14 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Types and causes of infertility

3. Pharmacological Effects and Immune Mechanisms Of Oriental Medicines

3.1. Varicocele

3.2. Oxidant Stress

3.3. IOA

3.4. Anti-Cancer Treatment

4. Cons Related to the Oriental Medicines Treatment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Collins, J.A. Male infertility: the interpretation of the diagnostic assessment. In The Year Book of Infertility, Mishell, D.R., Paulsen, C.A., Lobo, R.A., Eds.; Year Book Medical Publishers Inc.: Chicago, 1989; Vol. 1989; p. 45.

- Rowe, P.J. WHO Manual for the Standardized Investigation, Diagnosis and Management of the Infertile Male, Cambridge Uni Varsity Press; Cambridge, UK, 2000.

- Barratt, C.L.; Björndahl, L.; De Jonge, C.J.; Lamb, D.J.; Osorio Martini, F.; McLachlan, R.; Oates, R.D.; van der Poel, S.; St John, B.; Sigman, M.; et al. The diagnosis of male infertility: an analysis of the evidence to support the development of global WHO guidance-challenges and future research opportunities. Human Reproduction Update 2017, 23, 660–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohle, G.R.; Halley, D.J.J.; Van Hemel, J.O.; van den Ouwel, A.M.; Pieters, M.H.; Weber, R.F.; Govaerts, L.C. Genetic risk factors in infertile men with severe oligozoospermia and azoospermia. Hum Reprod 2002, 17, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, S.A.; Eskenazi, B.; Wyrobek, A.J. Effects of male age on semen quality and fertility: a review of the literature. Fertil Steril 2001, 75, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, A.; Spira, A.; Multigner, L. Contribution of environmental factors to the risk of male infertility. Hum Reprod 2001, 16, 1768–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machen, G.L.; Sandlow, J.I. Causes of male infertility. Male Infertil Springer 2020, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, J.; Kang, M.J. Successful Treatment of Oligoasthenozoospermia Using Traditional Korean Medicine Resulting in Spontaneous Preg Nancy: Two Case Reports; Vol. 12; Explore Publications, 2016; pp. 136–138.

- Tournaye, H. Male factor infertility and ART. Asian J Androl 2012, 14, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoton-Vlasak, A. Drury KC. ART and its impact on male infertility management. Male Infertility; Springer: New York, 2012.

- Smith, R.P.; Lipshultz, L.I.; Kovac, J.R. Stem cells, gene therapy, and advanced medical management hold promise in the treatment of male infertility. Asian J Androl 2016, 18, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.I.; Wu, C.G.; Jun, S.X.; et al. A controlled randomized trial of the use of combined L-carnitine and acetyl-L-carnitine treatment in men with oligoasthenozoospermia. J Androl 2005, 11, 761–764. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzstein, L.; Aparicio, N.J.; Schally, A.V. D-Tryptophan-6-luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone in the treatment of normogonadotropic oligoasthenozoospermia. Int J Androl 2010, 5, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Coscione, A.; Li, L.; Zeng, B.-Y. Effect of Chinese herbal medicine on male infertility. Int Rev Neurobiol 2017, 135, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, J.R.; Billingham, R.E. Immune privilege in the testis. II. Evaluation of potential local factors. Transplantation 1982, 40, 269–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhushan, S.; Meinhardt, A. The macrophages in testis function. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2017, 119, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

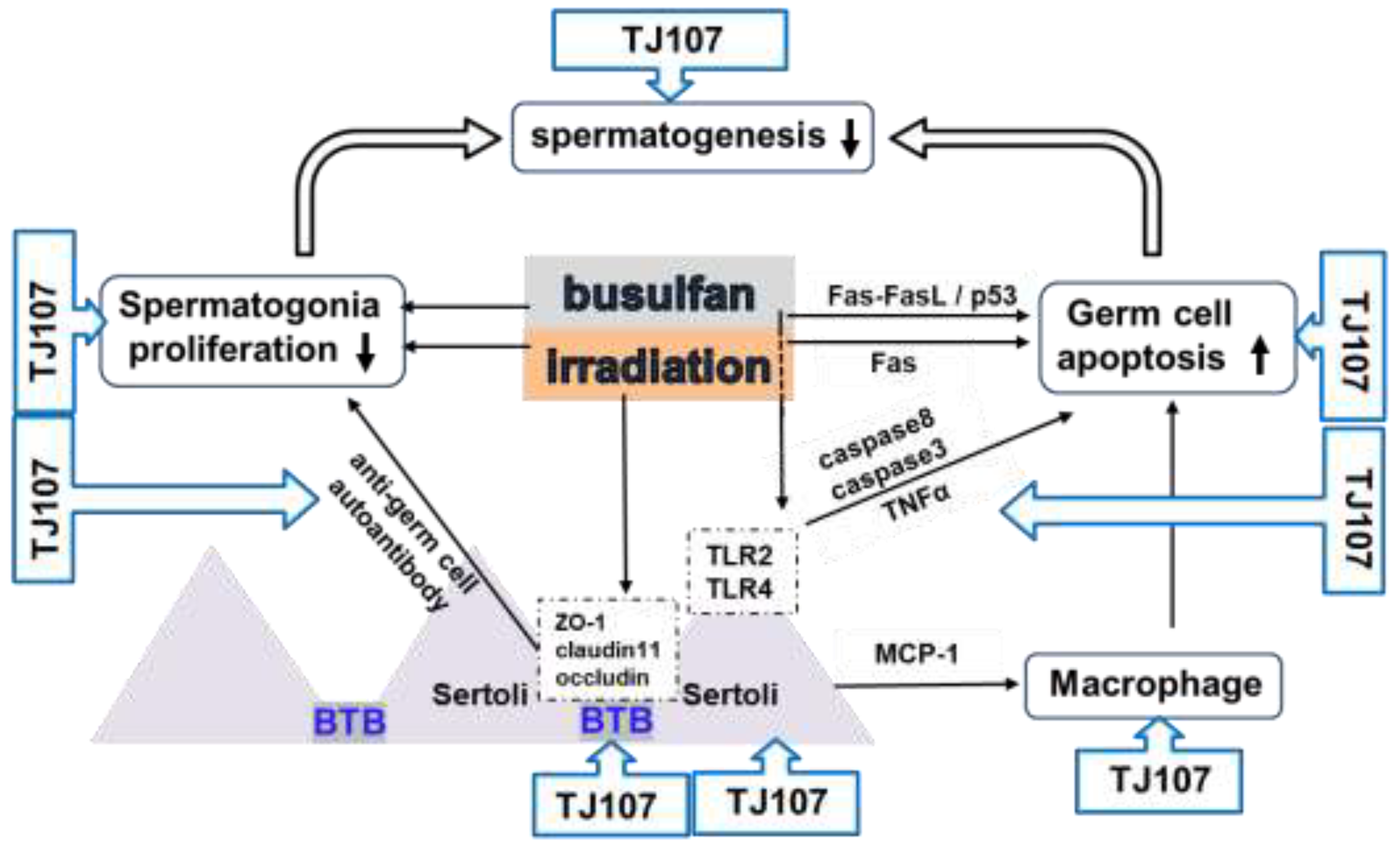

- Qu, N.; Itoh, M.; Sakabe, K. Effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy on spermatogenesis: the role of testicular immunology. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, E957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, S.A.; Robins, S.; Zhu, Y.J.; Keeren, K.; Gu, V.; Read, S.C.; Zelkowitz, P. Evidence for the use of complementary and alternative medicines during fertility treatment: a scoping review. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amory, J.K.; Ostrowski, K.A.; Gannon, J.R.; Berkseth, K.; Stevison, F.; Isoherranen, N.; Muller, C.H.; Walsh, T. Isotretinoin administration improves sperm production in men with infertility from oligoasthenozoospermia: a pilot study. Andrology 2017, 5, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WorldHealthOrganization. WHOLaboratoryManualfortheExaminationandProcessingofHumanSemen; WorldHealthOrganization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 6, pp. 1–276. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, A.; Schuppe, H.C. Influence of genital heat stress on semen quality in humans. Andrologia 2007, 39, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleton, P.E.; Deluao, J.C.; Sharkey, D.J.; McPherson, N.O. Measuring reactive oxygen species in Semen for Male Preconception Care: A Scientist Perspective. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, C. Reactive oxygen species and male fertility. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmar, A.T. Role of oxidative stress in male infertility: an updated review. J Hum Reprod Sci 2019, 12, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Parekh, N.; Panner Selvam, M.K.; Henkel, R.; Shah, R.; Homa, S.T.; Ramasamy, R.; Ko, E.; Tremellen, K.; Esteves, S.; et al. Male oxidative stress infertility (MOSI): proposed terminology and clinical practice guidelines for management of idiopathic male infertility. World J Mens Health 2019, 37, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak-Jedrzejowska, R.; Wolski, J.K.; Slowikowska-Hilczer, J. The role of oxidative stress and antioxidants in male fertility. Cent Eur J Urol 2013, 66, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mieusset, R.; Bujan, L. Testicular heating and its possible contributions to male infertility: a review. Int J Androl 1995, 18, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Medan, M.S.; Ozu, M.; Li, C.; Watanabe, G.; Taya, K. Effects of experimental cryptorchidism on sperm motility and testicular endocrinology in adult male rats. J Reprod Dev 2006, 52, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setchell, B.P. The effects of heat on the testes of mammals. Anim Reprod 2006, 3, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Mahfouz, R.Z.; du Plessis, S.S.; Aziz, N.; Sharma, R.; Sabanegh, E.; Agarwal, A. Sperm viability, apoptosis, and intracellular reactive oxygen species levels in human spermatozoa before and after induction of oxidative stress. Fertil Steril 2010, 93, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteves, S.C.; Agarwal, A. Novel concepts in male infertility. Int Braz J Urol 2011, 37, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, E.J.; Young, G.P.; Goldstein, M. Reduction in testicular temperature after varicocelectomy in infertile men. Urology 1997, 50, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allamaneni, S.S.; Naughton, C.K.; Sharma, R.K.; Thomas, A.J., Jr.; Agarwal, A. Increased seminal reactive oxygen species levels in patients with varicoceles correlate with varicocele grade but not with testis size. Fertil Steril. 2004, 82, 1684–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will, M.A.; Swain, J.; Fode, M.; Sonksen, J.; Christman, G.M.; Ohl, D. The great debate: varicocele treatment and impact on fertility. Fertil Steril 2011, 95, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, C.; Santoro, G. Varicocele Infertil Why Prev? J Endocrinol Invest. 2009, 32, 559.e561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin, L.; Amelar, R.D. Varicocelectomy as therapy in male infertility: a study of 504 cases. Fertil Steril 1975, 26, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Su, Y.; Xu, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, K.; Liu, C.; Zhang, H. Varicocele-mediated male infertility: from the perspective of testicular immunity and inflammation. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 729539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandekerckhove, P.; Lilford, R.; Vail, A.; Hughes, E. Clomiphene or tamoxifen for idiopathic oligo/asthenospermia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000, 1996, CD000151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razi, M.; Tavalaee, M.; Sarrafzadeh-Rezaei, F.; Moazamian, A.; Gharagozloo, P.; Drevet, J.R.; Nasr-Eshafani, M.-H. Varicocoele and oxidative stress: new perspectives from animal and human studies. Andrology 2021, 9, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, W.; Hudson, M.M.; Strickland, D.K.; Phipps, S.; Srivastava, D.K.; Ribeiro, R.C.; Rubnitz, J.E.; Sandlund, J.T.; Kun, L.E.; Bowman, L.C.; et al. Late effects of treatment in survivors of childhood acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2000, 18, 3273–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.B.; Campbell, A.J.; Irvine, D.C.; Anderson, R.A.; Kelnar, C.J.H.; Wallace, W.H.B. Semen quality and spermatozoal DNA integrity in survivors of childhood cancer: a case-control study. Lancet 2002, 360, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meistrich, M.L.; Wilson, G.; Brown, B.W.; da Cunha, M.F.; Lipshultz, L.I. Impact of cyclophosphamide on long-term reduction in sperm count in men treated with combination chemotherapy for Ewing and soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer 1992, 70, 2703–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speiser, B.; Rubin, P.; Casarett, G. Aspermia following lower truncal irradiation in Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer 1973, 32, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anserini, P.; Chiodi, S.; Spinelli, S.; Costa, M.; Conte, N.; Copello, F.; Bacigalupo, A. Semen analysis following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Additional data for evidence-based counselling. Bone Marrow Transplant 2002, 30, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobadi, E.; Moloudizargari, M.; Asghari, M.H.; Abdollahi, M. The mechanisms of cyclophosphamide-induced testicular toxicity and the protective agents. Expert Opin Drug Met. 2017, 13, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietze, R.; Shihan, M.; Stammler, A.; Konrad, L.; Scheiner-Bobis, G. Cardiotonic steroid ouabain stimulates expression of blood-testis barrier proteins claudin-1 and −11 and formation of tight junctions in Sertoli cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2015, 405, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urriola-Muñoz, P.; Lagos-Cabré, R.; Moreno, R.D. A mechanism of male germ cell apoptosis induced by bisphenol-A and nonylphenol involving ADAM17 and p38 MAPK activation. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e113793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; You, Y.; Zhang, P.; Huang, X.; Dong, L.; Yang, F.; Yu, X.; Chang, D. Qiangjing tablets repair blood-testis barrier dysfunction in rats via regulating oxidative stress and p38 MAPK pathway. BMC Complement Med Ther 2022, 22, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.A.; Robinson, J.; Furr, B.J.; Shalet, S.M.; Morris, I.D. Protection of spermatogenesis in rats from the cytotoxic procarbazine by the depot formulation of Zoladex, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist. Cancer Res 1990, 50, 568–574. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.H.; Linde, R.; Hainsworth, J.D.; Vale, W.; Rivier, J.; Stein, R.; Flexner, J.; Van Welch, R.; Greco, F.A. Effect of a luteinizing hormone releasing hormone agonist given during combination chemotherapy on posttherapy fertility in male patients with lymphoma: preliminary observations. Blood 1985, 65, 832–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinster, R.L.; Zimmermann, J.W. Spermatogenesis following male germ-cell transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994, 91, 11298–11302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tempest, H.G.; Homa, S.T.; Routledge, E.J.; Garner, A.; Zhai, X.P.; Griffin, D.K. Plants used in Chinese medicine for the treatment of male infertility possess antioxidant and anti-oestrogenic activity. Syst Biol Reprod Med 2008, 54, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.J.; Bae, G.S.; Park, J.H.; Song, T.H.; Choi, A.; Ryu, B.Y.; Pang, M.G.; Kim, E.J.; Yoon, M.; Chang, M.B. Antioxidant effects of cultured wild ginseng root extracts on the male reproductive function of boars and guinea pigs. Anim Reprod Sci 2016, 170, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Choe, S.; Park, N.C. Effects of Korean red ginseng on semen parameters in male infertility patients: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical study. Chin J Integr Med 2016, 22, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, H.; Ng, E.H.Y.; Wu, X.K. Eastern medicine approaches to male infertility. Semin Reprod Med 2013, 31, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Li, S.G.; Zhang, T.Y.; Dong, P.P.; Zeng, Q.Q. Runjing Extract Promotes Spermatogenesis in Rats with Ornidazole-Induced Oligoasthenoteratozoospermia through Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Signalling, and Regulating Vimentin Expression. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2021, 41, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Huang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, H.; Liu, X.; Pang, T.; He, L.; Lin, H.; Hu, L.; et al. Jiawei Runjing decoction improves spermatogenesis of cryptozoospermia with varicocele by regulating the testicular microenvironment: two-center prospective cohort study. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 945949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Lan, X.; Chen, X.; Wu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y. Researching the molecular mechanisms of Taohong Siwu Decoction in the treatment of varicocele-associated male infertility using network pharmacology and molecular docking: a review. Medicine 2023, 102, e34476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, W.; Bai, Y.; Ning, N.; Huang, Q.; Pang, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, K. Zishen Yutai Pill improves sperm quality and reduces testicular inflammation in experimental varicocele rats. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SenGupta, P.; Agarwal, A.; Pogrebetskaya, M.; Roychoudhury, S.; Durairajanayagam, D.; Henkel, R. Role of Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha) in the management of male infertility. Reprod Biomed Online 2018, 36, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karna, K.K.; Soni, K.K.; You, J.H.; Choi, N.Y.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, C.Y.; Lee, S.W.; Shin, Y.S.; Park, J.K. MOTILIPERM ameliorates immobilization stress-induced testicular dysfunction via inhibition of oxidative stress and modulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in SD rats. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 4750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, K.K.; Zhang, L.T.; Choi, B.R.; Karna, K.K.; You, J.H.; Shin, Y.S.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, C.Y.; Zhao, C.; Chae, H.J.; et al. Protective effect of motiliperm in varicocele-induced oxidative injury in rat testis by activating phosphorylated inositol requiring kinase 1alpha (p-IRE1alpha) and phosphorylated c-Jun N-terminal kinase (p-JNK) pathways. Pharm Biol 2018, 56, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Fu, L.; An, Q.; Hu, W.; Liu, J.; Tang, X.; Ding, Y.; Lu, W.; Liang, X.; Shang, X.; et al. Effects of Qilin pills on spermatogenesis, reproductive hormones, oxidative stress, and the TSSK2 gene in a rat model of oligoasthenospermia. BMC Complement Med Ther 2020, 20, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.D. The literature study on the efficacy and manufacturing process of gyeongoggo. J Orient Med Clas Sics 2011, 24, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, D.-S.; Kim, H.G.; Park, S.; Hong, N.D.; Ryu, J.H.; Oh, M.S. Effect of a traditional herbal prescription, Kyung-ok-Ko, on male mouse spermatogenic ability after heat-induced damage. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015, 2015, 950829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Shin, B.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, J.M.; Park, S.J.; Park, C.S.; Won, D.H.; Hong, N.D.; Kang, D.H.; Yutaka, Y.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of a traditional herbal prescription on transient cerebral global ischemia in gerbils. J Ethnopharmacol 2011, 138, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.M.; An, C.S.; Jung, K.Y.; Choo, Y.K.; Park, J.K.; Nam, S.Y. Rehmannia glutinosa inhibits tumour necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1 secretion from mouse astrocytes. Pharmacol Res 1999, 40, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.P.; Shi, X.; Kong, G.W.S.; Wang, C.C.; Wu, J.C.Y.; Lin, Z.X.; Li, T.C.; Chan, D.Y.L. The therapeutic effects of a traditional Chinese medicine formula Wuzi Yanzong Pill for the treatment of oligoasthenozoospermia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2018, 2018, 2968025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xue, Y.; Bao, B.; Wang, J.; Dai, H.; Gong, X.; Zheng, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, B. Effectiveness comparison of a Chinese dicitraditionalmene formula Wuzi Yanzong Pill and its analogous prescriptions for the treatment of oligoasthenozoospermia: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Medicine 2019, 98, e15594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Tong, K.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Zhao, P.; Gu, M.; Hu, J.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Z. Mechanism of action of Wuzi Yanzong pill in the treatment of oligoasthenozoospermia in rats determined via serum metabolomics. J Trad Chin Med Sci 2024, 11, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Q.; Wang, B.; Ding, C.F.; Wan, L.Y.; Hu, H.M.; Lv, B.D.; Ma, J.X. In vivo and in vitro protective effects of the Wuzi Yanzong pill against experimental spermatogenesis disorder by promoting germ cell proliferation and suppressing apoptosis. J Ethnopharmacol 2021, 280, 114443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condorelli, R.A.; Barbagallo, F.; Calogero, A.E.; Cannarella, R.; Crafa, A.; La Vignera, S. D-Chiro-inositol improves sperm mitochondrial membrane potential: in vitro evidence. J Clin Med 2020, 9, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, S.K.; Agrawal, A.K.; Hakim, B.A.; Vishwakarma, A.L.; Narender, T.; Sachan, R.; Sachdev, M. Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) regulates sperm motility. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 2016, 52, 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, D.; Gallo, M.; Rizzo, F.; Baldi, E.; Francavilla, S.; Lenzi, A.; Lombardo, F.; Gandini, L. Mitochondrial membrane potential profile and its correlation with increasing sperm motility. Fertil Steril 2011, 95, 2315–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamo, A.; De Luca, C.; Mongioì, L.M.; Barbagallo, F.; Cannarella, R.; La Vignera, S.; Calogero, A.E.; Condorelli, R.A. Mitochondrial membrane potential predicts 4-hour sperm motility. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.C.; Wang, S.C.; Li, C.J.; Lin, C.H.; Huang, H.L.; Tsai, L.M.; Chang, C.H. The therapeutic effects of traditional Chinese medicine for poor semen quality in infertile males. J Clin Med 2018, 7, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Sun, Z.X.; Zhao, S.P.; Zhang, X.H.; Chen, J.S.; Wang, R.; Men, B. Yishen Tongluo Recipe combined with minimally invasive surgery for the treatment of varicocele-associated asthenospermia. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 2020, 26, 341–345. [Google Scholar]

- Idänpään-Heikkilä, J.E. Ethical principles for the guidance of physicians in medical research–the Declaration of Helsinki. Bull World Health Organ 2001, 79, 279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Fan, L.; Li, F.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, C.; Chen, R. Yishentongluo decoction in treatment of idiopathic asthenozoospermia infertility: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Medicine 2020, 99, e22662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Tian, F.; Liu, P.; et al. Sheng Jing decoction as a traditional Chinese medicine prescription can promote spermatogenesis and increase sperm motility (Research Square), 2021. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-167175/v1.

- Yan, G.; Tian, F.; Liu, P.; Sun, J.; Mao, J.; Han, W.; Mo, R.; Guo, S.; Yu, Q.Yu.S. Sheng Jing Decoction can promote spermatogenesis and increase sperm motility of the oligozoospermia mouse model. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2021, 2021, 3686494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Yang, Y.; Jo, J.; Yoon, S.R. Modified MYOMI-14 Korean herbal formulations have protective effects against cyclophosphamide-induced male infertility in mice. Andrologia 2021, 53, e14025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, P.; Van Saen, D.; Goossens, E. Can mesenchymal stem cells improve spermatogonial stem cell transplantation efficiency? Andrology 2017, 5, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsson, M.; Vatanen, A.; Borgström, B.; Gustafsson, B.; Taskinen, M.; Saarinen-Pihkala, U.M.; Winiarski, J.; Jahnukainen, K. Adult testicular volume predicts spermatogenetic recovery after allogeneic HSCT in childhood and adolescence. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014, 61, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanderson, B.J.; Shield, A.J.; Sanderson, B.J.S. Mutagenic damage to mammalian cells by therapeutic alkylating agents. Mutat Res 1996, 355, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigg, A.P.; McLachlan, R.; Zaja, J.; Szer, J. Reproductive status in long-term bone marrow transplant survivors receiving busulfan-cyclophosphamide (120 mg/kg). Bone Marrow Transplant 2000, 26, 1089–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfitzer, C.; Orawa, H.; Balcerek, M.; Langer, T.; Dirksen, U.; Keslova, P.; Zubarovskaya, N.; Schuster, F.R.; Jarisch, A.; Strauss, G.; Borgmann-Staudt, A.; et al. Dynamics of fertility impairment and recovery after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in childhood and adolescence: results from a longitudinal study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2015, 141, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, L.R.; Meistrich, M.L. Effects of busulfan on murine spermatogenesis: cytotoxicity, sterility, sperm abnormalities, and dominant lethal mutations. Mutat Res 1987, 176, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J.; Ok, D.W.; Kwon, D.N.; Il Chung, J.I.; Kim, H.C.; Yeo, S.M.; Kim, T.; Seo, H.G.; Kim, J.H. Murine male germ cell apoptosis induced by busulfan treatment correlates with loss of c-kit-expression in a Fas/FASL- and p53-independent manner. FEBS Lett 2004, 575, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiliausha, S.R.; Beltrame, F.L.; de Santi, F.; Cerri, P.S.; Caneguim, B.H.; Sasso-Cerri, E. Seminiferous epithelium damage after short period of busulphan treatment in adult rats and vitamin B12 efficacy in the recovery of spermatogonial germ cells. Int J Exp Pathol 2016, 97, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zohni, K.; Zhang, X.; Tan, S.L.; Chan, P.; Nagano, M.C. The efficiency of male fertility restoration is dependent on the recovery kinetics of spermatogonial stem cells after cytotoxic treatment with busulfan in mice. Hum Reprod 2012, 27, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Liu, L.; He, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhu, H.; Liang, M.; Hao, H.; Qin, T.; Zhao, X.; Wang, D. Testicular injection of busulfan for recipient preparation in transplantation of spermatogonial stem cells in mice. Reprod Fertil Dev 2016, 28, 1916–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, N.; Kuramasu, M.; Hirayanagi, Y.; Nagahori, K.; Hayashi, S.; Ogawa, Y.; Terayama, H.; Suyama, K.; Naito, M.; Sakabe, K.; et al. Gosha-Jinki-Gan recovers spermatogenesis in mice with busulfan-induced aspermatogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, E2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, N.; Nagahori, K.; Kuramasu, M.; Ogawa, Y.; Suyama, K.; Hayashi, S.; Sakabe, K.; Itoh, M. Effect of Gosha-Jinki-Gan on levels of specific mRNA transcripts in mouse testes after busulfan treatment. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Nagahori, K.; Qu, N.; Kuramasu, M.; Hirayanagi, Y.; Hayashi, S.; Ogawa, Y.; Hatayama, N.; Terayama, H.; Suyama, K.; et al. The effectiveness of traditional Japanese medicine Goshajinkigan in irradiation-induced aspermatogenesis in mice. BMC Complement Altern Med 2019, 19, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Immuno- suppressive Factors in Normal Testis |

Anti-cancer treatment |

Varicocele |

Oxidant stress |

IOA | |

| germ | TGF-β | ↑37 | ↑22 | ↑70 | |

| cells | Fas-L | ↑82,93,94 | ↑or (-)37 | ↑70 | |

| IFN-γ | ↑37 | ||||

| TNF-α | ↑82,93,94 | ↑37 | ↑22,61 | ||

| Fas ↑ Bax ↑82 | Fas ↑37 | caspase3 ↑61 | PI3K/AKT/mTOR↓70 | ||

| Caspase3,8 ↑82,93,95 | Caspase1 ↑59 | Bax ↑ p53↑29,30,62 | ROS↑75 | ||

| p53-ROS↑82 | SOD↑29 | ||||

| Sertoli | activin | ||||

| cells | inhibin | ||||

| IL-6 | ↑37 | ↑67 | |||

| Fas-L | ↑93,94 | ↑70 | |||

| TNF-α | ↑82,93,94 | ↑37 | ↑67 | ||

| MCP-1↑93,94 | claudin-11↓37 | ||||

| TLR2,4↑93,94 | |||||

| Occludin↓48,95 | |||||

| ZO-1↓48,95 | |||||

| F-actin↓48 | |||||

| Leydig | testosterone | ↓48 | ↓37,38 | ↓62 | ↓20 |

| cells | portein s | ||||

| Fas-L | |||||

| IL-10 | ↑37 | ||||

| TGF-β | ↑37 | ||||

| Bcl-2↑82 | |||||

| Testicular | IL-10 | ↑37 | ↑70 | ||

| macro- | IFN-γ | ↑37 | |||

| phages | IL-6 | ↑37 | ↑29,30 | ||

| TNF-α | ↑93,94 | ↑37 | ↑67 | ||

| macrophage infiltration ↑93,94 |

IL-1β ↑37, 59 | IL-1β↑67 | |||

| Others | FSH, LH↓51 | ASA↑37 | ROS/NOS↑22, 29,30,60-63 | MMP ↓69,72,74,78 | |

| MMP ↓81 | ROS↑33,58 | FSH, LH↓63 | |||

| ROS, MDA↑51,82 | FSH ↑57 | ||||

| ASA↑17,95 | NLRP3↑37, 59 |

| Oriental medicine | Compounds | |

|

Anti-cancer treatment |

Goshajinkigan (TJ107) 93-95 Japanese herbal medicines |

Rehmanniae radix, Achyranthis radix, Corni fructus, Dioscoreae rhizome, Plantaginis semen, Alismatis rhizome, Hoelen, Moutan cortex, Cinnamomi cortex, processed Aconite tuber |

|

MYOMI- 7 82 Korean herbal medicines |

Cuscuta chinensis, Lycium chinense, Epimedium koreanum, Rubus coreanus, Morinda officinalis, Cynomorium songaricum, Cistanche deserticola | |

|

Qiangjing tablets (QJT) 47 Chinese herbal medicines |

Ginseng radix et rhizoma, Angelica sinensis radix, Rehmanniae radix praeparata, Corni fructus, Lycii fructus, Schisandrae chinensis fructus, Cuscutae semen, Plantaginis semen, Epimedii folium, Common curculigo orchioides, Herba leonuri | |

|

Sheng Jing Decoction (SJD) 48,81 Chinese herbal medicines |

Rehmannia glutinosa, Astragalus membranaceus, Pseudostellaria heterophylla, Dipsacus acaulis, Lycium arenicolum, Astragalus complanatus, Gleditsia sinensis | |

| Varicocele |

Jiawei Runjing Decoction (JWRJD) 57 Chinese herbal medicines |

Cuscuta chinensis, Dioscorea polystachya, Polygonatum sibiricum, Epimedium brevicornu, Lycium barbarum, Eleutherococcus senticosus, Rhodiola crenulata, Cyathula officinalis, Citrus × aurantium, Hirudo, Homo sapiens, Eupolyphaga seu Steleophaga. |

|

Taohong Siwu Decoction (THSWD) 58 Chinese herbal medicines |

Persicae semen, Carthami flos, Rehmanniae radix praeparata, Paeoniae radix alba, Chuanxiong rhizoma, Angelicae sinensis radix | |

|

Zishen Yutai Pill (ZYP) 59 Chinese herbal medicines |

Cuscutae semen, Ginseng radix et rhizoma, Dipsaci radix, Taxilli herba, Eucommiae cortex, Morindae officinalis radix, Cervi cornu degelatinatum, Codonopsis radix, Atractylodis macrocephalae rhizoma, Asini corii colla, Lycii fructus, Rehmanniae radix praeparata, Polygoni multiflori radix praeparata, Artemisiae argyi, Amomi fructus | |

|

Oxidant and Heat stress |

Kyung-Ok-Ko (KOK) 64-67 Korean herbal medicines |

Rehmannia glutinosa var. purpurea, Panax ginseng, Poria cocos, Lycium chinense, Aquilaria agallocha, honey |

|

MOTILIPERM (MTP) 61 Korean herbal medicines |

Rubiaceae root, Convol vulaceae seed, Liliaceae outer scales | |

|

Qilin pills (QLPs) 63 Chinese herbal medicines |

Polygonum multijiorum, Herba Ecliptae, Eclipta prostrata, Epimedium brevicornu, Cuscuta chinensis, Cynomorium songaricum, Codonopsis pilosula, Curcuma aromatica, Lycium chinense, Rubus idaeus, Dioscorea oppositifolia, Salvia miltiorrhiza, Astragalus membranaceus, Paeonia lactiflora, Citrus reticulata, Morus alba | |

| IOA |

Wuzi Yanzong pill (WZYZP) 54,68-70 Chinese herbal medicines |

Cuscutae chinensis semen, Lycii fructus, Rubi fructus, Schizandrae fructus, Plantaginis semen |

|

Yishentongluo decoction (YSTL) 75-78 Chinese herbal medicines |

Cuscuta chinensis, Epimedium brevicornu, Rehmannia glutinosa, Astragalus propinquus, Salvia miltiorrhiza, Cyathula officinalis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).