1. Introduction

Systemic racism in health care has emerged as one of Canada’s most pressing public health and policy challenges. Although disparities in health outcomes among indigenous and racialized populations have been documented for decades, recent high-profile cases, such as the deaths of Brian Sinclair in 2008 and Joyce Echaquan in 2020, have revealed how racial bias and institutional neglect can lead to preventable harm. These tragedies, alongside a series of federal and provincial inquiries, clarify that inequities in access, treatment, and outcomes are not isolated incidents but manifestations of deeper structural issues within Canadian health systems.

Despite being lauded for its universal coverage, Canada’s health care system often fails to deliver equitable care. Research has consistently shown that indigenous people, Black Canadians, and internationally trained physicians face poorer outcomes and systemic exclusion. This disconnection between policy ideals and lived experience exposes the limits of universality when equity is not explicitly embedded in governance, regulation, and practice.

Though the public and institutional awareness of systemic racism increased, critical deficiencies persist in the ways the issue is measured empirically and resolved. Early reports, such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action [1] and In Plain Sight [2], record systemic racism in indigenous healthcare provisions. In more recent years, the Canadian Human Rights Commission [3] and Public Health Agency of Canada [4] reaffirmed the presence of persistent disparities and accountability shortcomings in all health institutions.

Most of the existing literature consists of descriptive reports, advocacy pieces, or isolated case studies. What is lacking is an integrated, policy-oriented analysis that draws together findings from diverse sources, including public inquiries, academic research, legal proceedings, and government audits, to reveal how systemic racism is structured and sustained.

This paper meets this need by performing a qualitative examination of publicly accessible evidence. By employing thematic coding and embedded case studies, it discerned patterns of discrimination and exclusion based on race in four central areas: (1) patient safety and outcomes of care, (2) provider experience and workforce integration, (3) credentialing and professional regulation, and (4) institutionally based accountability and policy response. Brian Sinclair, Joyce Echaquan, and Dr. Oluwasayo Akinbiyi are cases used in providing context-based grounding for analysis.

This study’s contribution is two-fold. It provides a structured synthesis that brings the empirical evidence into conversation with the larger healthcare governance framework. It also positions systemic racism not simply as an issue of interpersonal bias, but of policy and structural concern that necessitates legislative, regulatory, and organizational change. In pursuing this approach, the study strives to inform accountable, equity-motivated interventions.

2. Method

Study Design

This study employed qualitative document analysis with embedded case studies to examine systemic racism in Canadian healthcare. The design conformed to the adopted techniques of policy-bounded qualitative research, merging the thematic coding of policy documents and exemplary case evidence. Thematic analysis incorporated the template posited by Braun and Clarke [5]. It has enabled the examination of the mechanisms in which systemic racism pervades throughout patient outcomes, the workforce, and regulation.

Data Sources

The publicly available sources were specifically chosen for breadth and applicability. These included:

Large-scale survey databases regarding healthcare access and demographics (e.g., the Canadian Community Health Survey [6]).

Government reports and audits (e.g., Truth and Reconciliation Commission [1], In Plain Sight [2], Canadian Human Rights Commission [3], and PHAC equity assessments [4]).

Professional association documents (e.g., CMA perspectives on systemic racism [7]).

Academic literature (e.g., thematic analysis methods [5], health equity studies [14]).

Investigative and media coverage of healthcare access and professional regulation systemic failings (e.g., Sinclair [8], Echaquan [9], Akinbiyi [10].

Legal and tribunal documents, including litigation related to provider discrimination [10].

Grey literature on internationally trained physicians (e.g., Radius SFU community report [11], CBC coverage [12]).

Workforce datasets (e.g., CIHI’s 2023 Health Workforce Quick Stats [13]).

Inclusion Criteria

Documents were included if they:

Responded to racial/ethnic disparities in Canadian healthcare (in the patient care or workforce areas)

Embedded case evidence, policy recommendations, or recorded empirical data;

They were published between 2000 and 2025, ensuring contemporary relevance.

Case studies, such as Brian Sinclair [8], Joyce Echaquan [9], Dr. Oluwasayo Akinbiyi [10], and a pseudonymized globally educated doctor (“Dr. Ramirez”), were kept owing to national recognizability and demonstration of systemic failings.

Data Extraction and Analysis

The papers were closely studied and coded thematically in three phases:

Open coding for identifying recurring themes in the context of racism, bias, and systemic exclusion.

Axial coding to arrange these in more general categories (e.g., clinical bias, credentialing barriers, and accountability deficiencies).

Selective coding to connect themes with illustrative cases and policy implications.

A coding matrix (

Table 1) was used to triangulate data sources, themes, supporting evidence, and policy links.

Ethical Considerations

This research used only publicly published documents; no institutional ethics approval was necessary. It is, however, worth noting that ethical diligence was observed in the presentation of sensitive content, avoiding sensationalism and framing case narratives within a systemic analysis rather than individual blame.

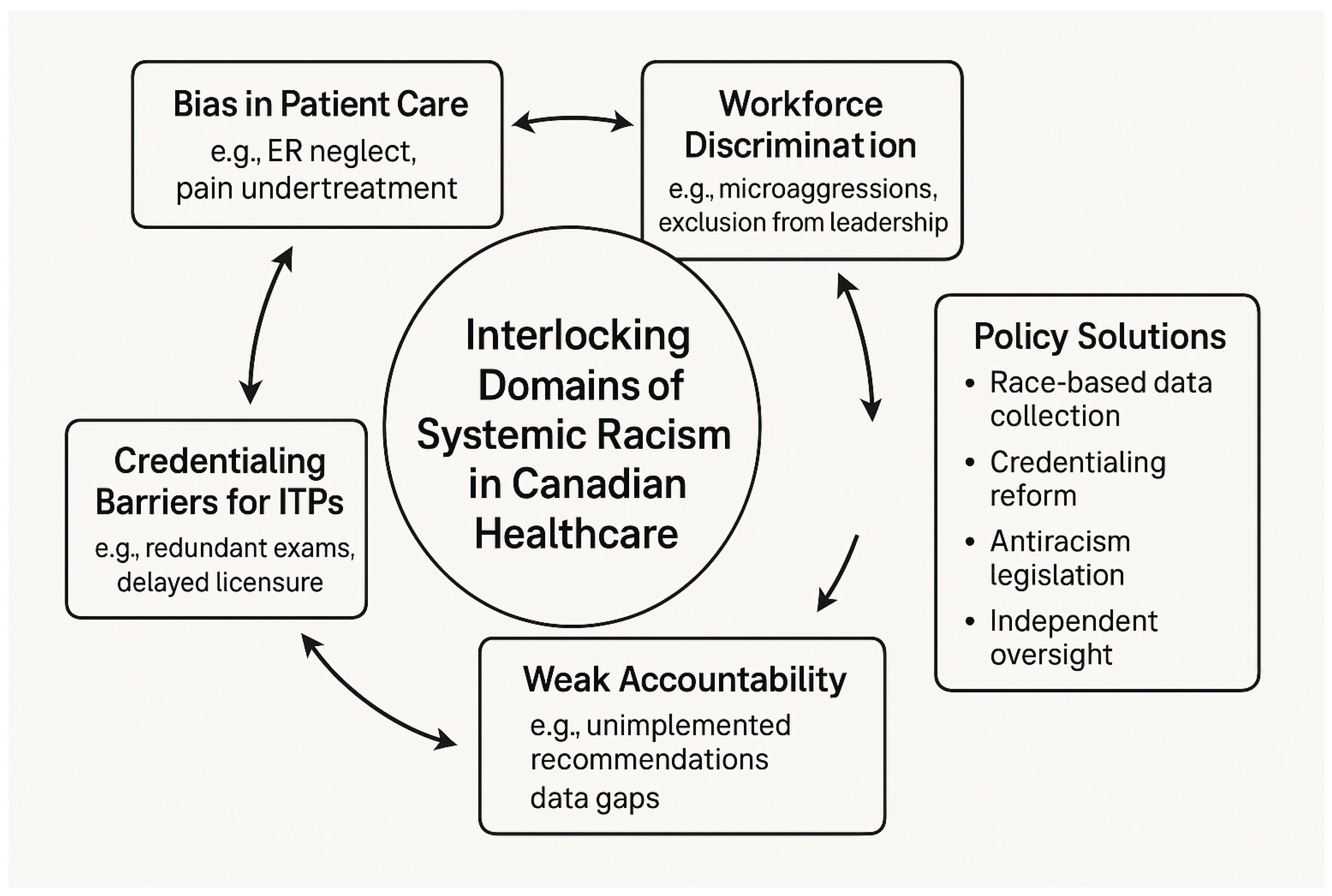

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework developed in this study, mapping the interlocking domains through which systemic racism is embedded in Canadian healthcare. These include bias in patient care, workforce discrimination, credentialing barriers, and institutional accountability gaps. The framework underscores how these domains reinforce each other and highlights policy entry points for intervention.

Figure 1.

Interlocking Domains of Systemic Racism in Canadian Healthcare.

Figure 1.

Interlocking Domains of Systemic Racism in Canadian Healthcare.

Table 1.

Coding Matrix of Themes, Supporting Evidence, and Illustrative Cases.

Table 1.

Coding Matrix of Themes, Supporting Evidence, and Illustrative Cases.

| Theme |

Supporting Evidence (Documents & Data) |

Illustrative Case(s) |

Policy Implication |

| Bias in Patient Care |

In the Plain Sight Report (2020), the PHAC Report on Racialized Adults (2023), and the literature on pain undertreatment in Black and Indigenous patients |

Brian Sinclair – died after 34 hours unattended in ER (2008, Winnipeg); Joyce Echaquan – livestreamed racist abuse before death (2020, Quebec) |

Mandate antiracism and cultural safety training; establish independent ER oversight bodies |

| Workforce Discrimination |

CMAJ commentary on racism in healthcare (Boyer, 2017); CHRC Systemic Racism Report (2023); data on underrepresentation in health leadership |

Dr. Oluwasayo Akinbiyi – lawsuit alleging racial discrimination and retaliation (2019–2023, Saskatchewan) |

Implement equity-based recruitment and promotion frameworks; set diversity benchmarks for leadership roles |

| Credentialing Barriers (ITPs) |

CBC reporting on foreign-trained physicians (2025); CIHI workforce data; Radius SFU/Wellesley reports on ITP exclusion |

Dr. Ismelda Ramirez – trained internist unable to practice due to licensure barriers (Quebec, 2020s) |

Expand Practice-Ready Assessment (PRA) programs; streamline credential recognition; audit for systemic bias |

| Weak Accountability & Oversight |

TRC Calls to Action (2015); CHRC equity audit (2023); absence of race-based health data (Canada vs. UK/NZ comparisons) |

Systemic trend – persistent inequities remain despite inquiries; lack of follow-through post-Sinclair and Echaquan cases |

Create Health Equity Oversight Boards; mandate disaggregated race-based data collection |

3. Result

This section presents the findings, organized into four thematic domains: bias in patient care, workforce discrimination, credentialing barriers for internationally trained physicians (ITPs), and institutional accountability. The evidence was drawn from publicly available inquiries, academic literature, workforce data, and case studies.

1. Bias in Patient Care

Systemic racism is responsible for differential treatment and disparities in outcomes among indigenous and racialized patients. Studies such as In Plain Sight and the PHAC health inequalities analysis reveal that racialized patients are at a higher likelihood of being misdiagnosed, under-treated for pain, or overlooked in emergency rooms [2,4].

Most egregiously, the 2008 death of Brian Sinclair, who died in a Winnipeg emergency room after 34 hours of being untreated, is an oft-cited instance of racially motivated medical neglect [8]. Similarly, Joyce Echaquan, an Atikamekw woman, streamed hospital staff’s racial insults just prior to her death in 2020 [9]. These instances are typical of the discrimination faced by indigenous patients and reveal the life-threatening consequences of biased triage, cultural insensitivity, and implicit bias in clinical decision making.

Despite decades of documentation, including studies on pain undertreatment among Black and Indigenous patients [15], these issues persist in both rural and urban settings. These findings reaffirm the need for mandated cultural safety and antiracism training for all frontline healthcare workers.

2. Workforce Discrimination

Black, Indigenous, and racialized healthcare professionals have described being excluded, made the target of microaggressions, and denied equal access to career advancement [3,7]. Underrepresentation in positions of leadership and the perpetuation of disrespectful workplace environments have been noted by the Canadian Human Rights Commission and the CMAJ [3,7].

One such case is that of Dr. Adeyinka Akinbiyi, a Black emergency doctor in Saskatchewan who brought a discrimination suit against the Saskatchewan Health Authority following allegations of reprisal for having reported systemic racism [10]. It is a case that illustrates the institutionally entrenched reluctance toward equity advocacy and the professional risks entailed in being a racialized doctor.

Data on leadership reinforce this gap: racialized doctors continue to be underrepresented in health management positions, and career advancement-related mentorship frameworks continue to be lacking [3,13]. Such trends indicate a structural inability to retain and promote racialized healthcare workers.

3. Credentialing Issues Confronting Internationally Trained Physicians

International medical graduates (IMGs) in Canada face a disproportionately long, expensive, and complex path to licensure. Reports by CBC News and Radius SFU document multiple structural hurdles, including redundant examinations, limited residency placements, and opaque recognition processes [11,12].

The composite case of Dr. Ismelda Ramirez, a highly qualified physician unable to secure licensure despite prior international practice, reflects a common trajectory among the ITPs. Many are relegated to non-clinical jobs despite meeting education standards.

According to CIHI, only 13.6% of immigrant International Medical Graduate (IMG) secure Canadian licensure, despite 84.7% having held medical licenses abroad [13]. Pharmacists and physicians were most likely to be internationally trained (35% and 27%, respectively), whereas only 10% of RNs came from international backgrounds. These disparities suggest that licensing bottlenecks are both professional-specific and systemic.

4. Weak Accountability and Oversight

Despite numerous commissions and inquiries having found systemic racism in the healthcare of Canadian provinces, recommendations remain for the most part unimplemented. 94 Calls to Action issued in 2015 by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) included a number relating specifically to discrimination in healthcare [1]; very few have been systematically upheld in health systems.

Similarly, the Viens Commission and the CHRC Equity Audit confirmed the existence of systemic racism and suggested structural reform [2,3]. However, such progress has been undone by the lack of enforcement-based mechanisms of accountability and transparency in data.

For instance, the CIHI workforce datasets do not capture the racial or indigenous identity of healthcare providers [13]. Without race-based data, it remains difficult to monitor progress on equity goals or to hold institutions accountable. Compared to international frameworks, such as the NHS Workforce Race Equality Standard in the UK and New Zealand’s Te Tiriti o Waitangi framework, Canada’s data and governance gaps are stark [16,17].

Table 1. Coding Matrix of Systemic Racism Themes in Canadian Healthcare. This matrix outlines the four major thematic domains identified through qualitative document analysis. For each theme, representative data sources, illustrative case examples, and corresponding policy implications are presented. The table demonstrates how evidence was triangulated across documents, real-world events, and institutional responses.

Table 2. Summary of Thematic Findings. This table provides a synthesized overview of the core findings across the four thematic areas. Each row captures the central insight derived from the data with corresponding illustrative cases and reference sources that exemplify these patterns in practice. This summary facilitates a high-level understanding of how systemic racism operates at multiple levels in the healthcare system.

5. Discussion & Policy Implications

The findings of this study validate that systemic discrimination in the healthcare of Canada is perpetuated through action (discriminatory regulations or organizational structures) and inaction (lack of implementing reforms). Discrimination in clinical interactions, exclusion of racialized professionals, and disjointed oversight demonstrate how ingrained these problems actually are.

Historic provincial differences in health status and service use have been reported over the past decades, reflecting the patchwork and incoherent nature of Canadian health equity policies across provinces [18]. Such differences make it clear that consistent, coordinated pan-Canadian policy initiatives are warranted, going beyond periodic reports and voluntary recommendations.

In making successful interventions, the Eightfold Path to Policy Analysis of Bardach and Patashnik offers a helpful process for ordered decision-making [19]. Applying the model in combating systemic racism can help identify where institutions’ incentives, administration, and areas of government support perpetuate inequalities.

The world paradigm offers teachable moments. Britain’s Workforce Race Equality Standard (WRES) places a requirement for all NHS trusts to undertake mandatory equity audits, which added greater transparency in the matter of workplace racism and progress tracking [16]. Similarly, New Zealand’s Te Tiriti o Waitangi framework combines the incorporation of indigenous partnerships and accountability in health planning, offering a rights framework in the realm of indigenous health equity [17].

Similar requirements do not exist in Canada. Institutions are not held responsible due to the lack of race-based health statistics, ineffective enforcement of anti-discrimination policies, and insufficient representation of racialized professionals in positions of decision-making.

Recent Canadian research confirms that anti-Black racism and other forms of discrimination persist across all levels of the healthcare system. A national qualitative study by Williams et al. documented how racialized healthcare users and professionals continue to face exclusion, tokenization, and institutional mistrust within mainstream settings [20]. These findings align closely with this study’s thematic analysis, reinforcing the need for urgent, systemic reform. Encouragingly, recent federal investments, including over $47 million to enhance health workforce data infrastructure, physician mobility, and credential recognition, signal growing national momentum to confront these systemic barriers in workforce planning and inclusion [21].

To fill such gaps, the following policy recommendations are necessary:

Legislate antiracism mandates within health acts and professional practice guidelines.

Mandate race-based data collection across all jurisdictions.

Expand and fast-track credential recognition for internationally educated professionals.

Provide cultural safety and equity training for all licensed providers.

Establish independent oversight bodies to monitor implementation and outcomes of health equity.

Without enforceable reform, Canada’s universal healthcare system will continue to perpetuate the very inequalities it aims to eliminate.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This project took the form of a qualitative document study and did not incorporate interviews, focus groups, or other primary data collection modes. Consequently, the results rely on the content and its being available in public documents and do not necessarily reflect the entire spectrum of lived experiences or informal organizational practices. We could not conduct intersectional or subgroup analyses since there is a lack of race-disaggregated workforce data in most Canadian databases, such as the CIHI’s QuickStats, used in this study. Where direct measures did not exist, we resorted to the use of proxy indicators (e.g., the country of training).

Cases were selected from news reports and public inquests, and hence potentially possess reporting biases or are prone to narrative framing. Although an attempt was made to include peer-reviewed scholarship and court filings, the selection had to be selective in its scope and could potentially have excluded pertinent unpublished or community-based scholarship.

Future research should prioritize:

Actual interaction with race-based healthcare beneficiaries and professionals in qualitative interviews or participatory studies;

Panel data observing the execution of equity-related policy shifts;

Quantitative analyses employing disaggregated race-based data, specifically, credentialing and outcomes of care

Comparisons of policy evaluation among provinces and foreign jurisdictions (e.g., the United Kingdom and New Zealand).

As structural racism is multifaceted and adaptive, ongoing empirical studies are essential to monitoring progress, designing effective interventions, and holding institutions accountable.

7. Conclusions

This paper reveals that systemic racism in Canadian healthcare is not a case of sporadic events, but a result of structural design inherent in clinical practice, workforce policies, and organizational decision-making. Based on public inquiry reports, real-life case examples, and peer-review evidence, it is transparent that racial disparities are ingrained in the manner in which care is provided and who is licensed to offer it. Despite universal access, racialized patients and internationally educated professionals (IEPs)/internationally trained professionals (ITPs) continue to be overwhelmingly denied/adversely harmed [1,2,3,4,8,9,10,11,13,14,15].

Despite numerous commissions and policy reports, such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission [1], the Viens Report [2], and the CHRC equity audit [3], Canada’s enforcement mechanisms have proven ineffective in translating the acknowledgment of racism into systemic reform. In sharp contrast, the Workforce Race Equality Standard (WRES) [16] of the UK and the Te Tiriti o Waitangi-based framework [17] in New Zealand have no equivalent national plan and accountability mechanism in the healthcare system in Canada.

Reform of policy ought, then, to transcend rhetorical assurances. To be equitable, Canada ought:

Incorporate antiracism provisions in the provincial and federal health acts [19];

Require collection of race-based data in order to track disparities and monitor progress [18];

Reform credentialing and licensing for ITPs, providing transparent and equitable access in order to enhance licensing equity and workforce planning [11,12,13,21];

Standardize cultural safety training and accountability mechanisms across jurisdictions [14,15];

Craft stand-alone oversight units to monitor institution equity progress and insist on compliance [3,16,17].

Without these structural reforms, universal healthcare will remain aspirational for many racialized Canadians, and tragedies, such as the deaths of Brian Sinclair [8] and Joyce Echaquan [9], will remain systemic, not exceptional. Equity must be built into the healthcare architecture and not added as an afterthought. The time for performative acknowledgment has passed. What is now needed is coordinated, enforceable, and measurable policy action across all levels of the health system.

Plain-Language Summary

Racism in healthcare is not only about individual attitudes; it is built into how the system works. Even though major reports such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and In Plain Sight have called out these problems, little has changed. Indigenous, Black, and other racialized people still face poor treatment and outcomes. Qualified immigrant doctors and nurses face unfair barriers to their work.

Other countries, such as the UK and New Zealand, have taken steps to track and fix these problems by collecting race-based data and holding healthcare systems accountable. Canada has not. Without real rules to ensure that changes happen, things will remain the same.

If Canada wants healthcare to be truly fair for everyone, we need laws, better data, antiracism training, and stronger oversight, not just words. This study showed that the time taken for action is now.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A. and A.A.; methodology, K.A.; validation, K.A., A.A., and D.D.; formal analysis, K.A.; investigation, K.A. and A.A.; resources, K.A. and T.K.; data curation, K.A.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A.; writing—review and editing, A.A., D.D., and T.K.; visualization, K.A.; supervision, A.A.; project administration, K.A.; funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was received for the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are openly available in the

Open Science Framework (OSF) at

https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HWABU. This includes all the coded documents, case summaries, and analytic frameworks referenced in the manuscript. The dataset comprised only publicly available documents and did not include any identifiable or sensitive personal information.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not involve human or animal subjects, and no new data were collected.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Written Informed Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing was not performed in this study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The Authors have no association with or financial interest in any institution or body that would financially gain from the subjects or content published in this manuscript.

References

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Calls to Action. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2015 [cited 2025 Aug 16]. Available from: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1450124405592/1529106060525.

- Viens N, VIENS Commission. In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Health Care. Victoria: Government of British Columbia; 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 16]. Available from: https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/613/2020/11/In-Plain-Sight-Summary-Report.pdf.

- Canadian Human Rights Commission. Equity Audit and Call to Action on Systemic Racism in Healthcare. Ottawa: CHRC; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 16]. Available from: https://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/sites/default/files/2024-04/chrc-annual-report-2023-en-final.pdf.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Inequalities in health of racialized adults in Canada. Ottawa: PHAC; 2023 [cited August 16, 2025]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/science-research-data/health-inequalities-inforgraphics/health-inequalities-racialized-adults-en.pdf.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 16]. Available from: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=1531795.

- Boyer Y. Tackling racism in Canadian healthcare: A physician’s view. CMAJ. 2017;189(12):E452–4. [CrossRef]

- Geary A. Ignored to death: Brian Sinclair’s death caused by racism, inquest inadequate, group says [Internet]. CBC News. 2017 Sep 18 [cited 2025 Aug 16]. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/winnipeg-brian-sinclair-report-1.4295996.

- 2 years after death of Joyce Echaquan, Quebec Health Ministry vows to improve Indigenous-awareness training [Internet]. CBC News. 2022 Sep 29 [cited 2025 Aug 17]. Available from: https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=6e8002a7-2c01-3f72-bdeb-6f0f656135e3.

- Quon A. Doctor’s lawsuit against Sask. Health Authority alleges discrimination at Regina General Hospital [Internet]. CBC News. 2025 Jan 31 [cited 2025 Aug 16]. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/sha-lawsuit-doctor-discrimination-1.7443882.

- Encalada Grez E, Ardiles Gamboa P, Purewal S. The exclusion of internationally trained physicians: A community-engaged research report [Internet]. Burnaby (BC): Radius SFU; 2023 Jan 24 [cited 2025 Aug 16]. Available from: https://radiussfu.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/The-Myth-Of-Canada_DIGITAL.pdf.

- Chughtai W, Lee V. Canada has a doctor shortage, but thousands of foreign-trained physicians already here still face barriers [Internet]. CBC News. 2025 Jan 17 [cited 2025 Aug 16]. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/international-doctors-canada-barriers-1.7428598.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Health Workforce in Canada, 2023 — Quick Stats. Ottawa: CIHI; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 16]. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/topics/health-workforce/data-tables.

- Allan B, Smylie J. First Peoples, Second Class Treatment: The Role of Racism in the Health and Well-being of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Toronto: Wellesley Institute; 2015 [cited 2025 Aug 16]. Available from: https://homelesshub.ca/resource/first-peoples-second-class-treatment-role-racism-health-and-well-being-indigenous-peoples-canada/.

- Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Lavoie J, Smye V, Wong ST, Krause M, et al. Enhancing health care equity with Indigenous populations: Evidence-based strategies from an ethnographic study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:544. [CrossRef]

- NHS England. NHS Workforce Race Equality Standard (WRES): 2022 data analysis report for NHS trusts [Internet]. London: NHS England; 2023 Feb [cited 2025 Aug 16]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/workforce-race-equality-standard.pdf.

- New Zealand Ministry of Health. Te Tiriti o Waitangi framework [Internet]. Wellington: Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora; [date unknown] [cited 2025 Aug 16]. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/maori-health/te-tiriti-o-waitangi-framework.

- Allin S. Does equity in healthcare use vary across Canadian provinces? Healthc Policy. 2008;3(4):83–99. PMID: 19377331; PMCID: PMC2645154. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2645154/.

- Bardach E, Patashnik E. A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving. 6th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): CQ Press; 2019. ISBN: 978-1506368887.

- Williams KKA, Baidoobonso S, Lofters A, Rashid M, Henry D, Vahabi M. Anti-Black racism in Canadian health care: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(3152). [CrossRef]

-

Government of Canada. Supporting Canada’s health workers by improving health workforce research, planning, and data [Internet]. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2024 Jul 11 [cited 2025 Aug 16]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2024/07/supporting-canadas-health-workers-by-improving-health-workforce-research-planning-and-data1.html.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).