Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

14 February 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

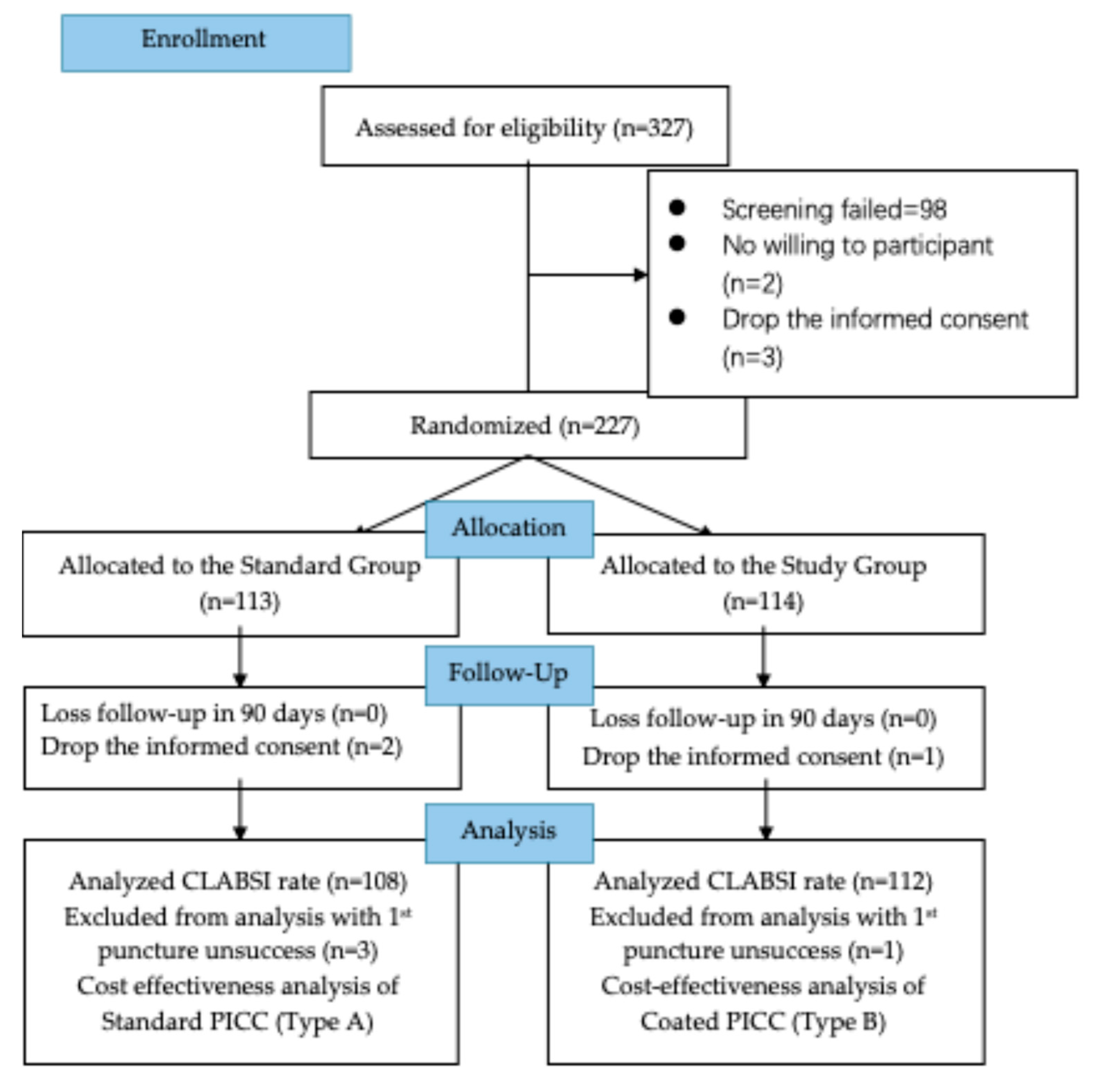

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Therapeutic Intervention

2.3. Evaluation of endpoints

2.4. Cost Evaluation Measures

2.5. Currency Rate and Conversion

2.6. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Primary Endpoints in Two Groups

3.2. Cost Analysis

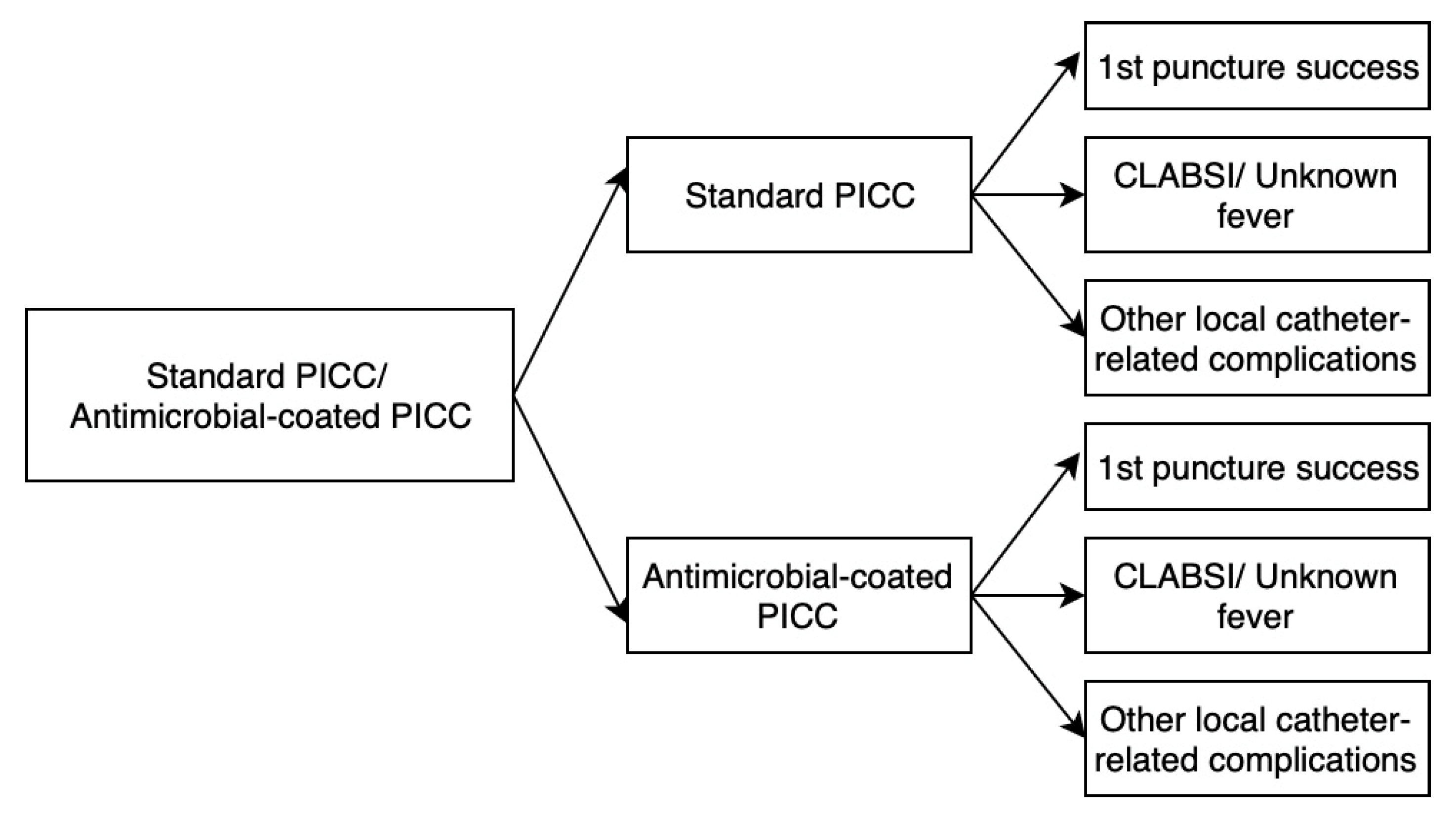

3.3. Decision Tree Model

3.4. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

4. Results

- Observation time and sample size. The clinical outcomes in this RCT had no significant difference, but it had clinical value. The observation time might need longer, and sample size should be bigger, this risk has been discussed on the clinical study protocol. The further study on CLABSI might suit to surveillance study, to observe the longer time and all population. However, the RCT is not an economic and efficacy solution.

- QALY adoption. In this evaluation, QALY was adopt from other hematology related patient quality life changing study of pre- and post- treatment. This data has described the general life quality changing around the treatment on this disease, it has the relationship with the catheter, but the catheter has no significant impact on the QALY, except death event related to the catheter infection. The catheter complication must lead the patient life qualities’ change, while previous research provides a general perspective, the catheter’s impact on QALYs may require further study with direct data collection or more effective indices to describe its effectiveness.

- Economic Evaluation Methods. Along with the people’s life quality pursuing, the more treatment and medical products work on life quality’s improvement. Almost procedures do not change the pathway of disease and just postpone the progress of disease. The current economic evaluation methods may not fully capture the value of treatments and medical products that primarily improve quality of life rather than altering disease pathways. Innovative theories and tools are needed to address the suitable value of such interventions scientifically.

4.1. Implications for Practice and Policy

4.2. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caris, M.G.; de Jonge, N.A.; Punt, H.J.; Salet, D.M.; de Jong, V.M.T.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.I.; Zweegman, S.; Vandenbroucke-Grauls, C.M.J.E.; van Agtmael, M.A.; Janssen, J.J.W.M. Indwelling time of peripherally inserted central catheters and incidence of bloodstream infections in haematology patients: a cohort study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2022, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhu, N.; Li, Y.; Fu, J.; Liu, J. Comparison of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) versus totally implantable venous-access ports in pediatric oncology patients, a single center study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novikov, A.; Lam, M.Y.; A Mermel, L.; Casey, A.L.; Elliott, T.S.; Nightingale, P. Impact of catheter antimicrobial coating on species-specific risk of catheter colonization: a meta-analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2012, 1, 40–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, H.Y.; Lai, N.M.; Apisarnthanarak, A.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. Comparative Efficacy of Antimicrobial Central Venous Catheters in Reducing Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in Adults: Abridged Cochrane Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 64, S131–S140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, K.; Zenz, S.; Jüttner, B.; Ruschulte, H.; Kuse, E.; Heine, J.; Piepenbrock, S.; Ganser, A.; Karthaus, M. Reduction of catheter-related infections in neutropenic patients: a prospective controlled randomized trial using a chlorhexidine and silver sulfadiazine-impregnated central venous catheter. Ann. Hematol. 2004, 84, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Gilbert et al., “Antimicrobial-impregnated central venous catheters for prevention of neonatal bloodstream infection (PREVAIL) : an open-label, parallel-group, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial,” Lancet Child Adolesc Health, vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 381–390, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Storey, S.; Brown, J.; Foley, A.; Newkirk, E.; Powers, J.; Barger, J.; Paige, K. A comparative evaluation of antimicrobial coated versus nonantimicrobial coated peripherally inserted central catheters on associated outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2016, 44, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardura, M.I.D.; Bibart, M.J.M.; Mayer, L.C.B.; Guinipero, T.; Stanek, J.; Olshefski, R.S.; Auletta, J.J. Impact of a Best Practice Prevention Bundle on Central Line-associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI) Rates and Outcomes in Pediatric Hematology, Oncology, and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Patients in Inpatient and Ambulatory Settings. J. Pediatr. Hematol. 2020, 43, e64–e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschall, J.; Mermel, L.A.; Fakih, M.; Hadaway, L.; Kallen, A.; O’grady, N.P.; Pettis, A.M.; Rupp, M.E.; Sandora, T.; Maragakis, L.L.; et al. Strategies to Prevent Central Line–Associated Bloodstream Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 Update. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiology 2014, 35, 753–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böll, B.; Schalk, E.; Buchheidt, D.; Hasenkamp, J.; Kiehl, M.; Kiderlen, T.R.; Kochanek, M.; Koldehoff, M.; Kostrewa, P.; Claßen, A.Y.; et al. Central venous catheter–related infections in hematology and oncology: 2020 updated guidelines on diagnosis, management, and prevention by the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO). Ann. Hematol. 2020, 100, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Cho, N.H.; Jeong, S.J.; Na Kim, M.; Han, S.H.; Song, Y.G. Effect of Central Line Bundle Compliance on Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections. Yonsei Med J. 2018, 59, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. P. O et al., “Guidelines for the Prevention of Intravascular Catheter-Related Infections (2011). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/bsi/c-i-dressings/index.html (accessed on 24 December 2022).

- 2021 Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice Updates. J. Infus. Nurs. 2021, 44, 189–190. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Hagihara, M.; Kurumiya, A.; Takahashi, T.; Sakata, M.; Shibata, Y.; Kato, H.; Shiota, A.; Watanabe, H.; Asai, N.; et al. Impact of mucosal barrier injury laboratory-confirmed bloodstream infection (MBI-LCBI) on central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) in department of hematology at single university hospital in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 2018, 24, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC, Ncezid, and DHQP, “Bloodstream Infection Event (Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection and Non-central Line Associated Bloodstream Infection).

- Xie, F.; Zhou, T.; Humphries, B.; Neumann, P.J. Do Quality-Adjusted Life Years Discriminate Against the Elderly? An Empirical Analysis of Published Cost-Effectiveness Analyses. Value Heal. 2024, 27, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.D.; Do, L.A.; Synnott, P.G.; Lavelle, T.A.; Prosser, L.A.; Wong, J.B.; Neumann, P.J. Developing Criteria for Health Economic Quality Evaluation Tool. Value Heal. 2023, 26, 1225–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guliyeva, A. Measuring quality of life: A system of indicators. Econ. Politi- Stud. 2021, 10, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, C.S.; Anderson, K.L. The Quality of Life Scale (QOLS): Reliability, Validity, and Utilization. Heal. Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, N.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, X. Peripherally inserted central catheter versus totally implanted venous port for delivering medium- to long-term chemotherapy: A cost-effectiveness analysis based on propensity score matching. J. Vasc. Access 2021, 23, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemen, A.; Daniels, A.; Janssen, R.; Samyn, M.; Elshof, J.-W. ECG Guided Tip Positioning Technique for Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters in a teaching Hospital: Feasibility and Cost-effectiveness Analysis in a Prospective Cohort Study. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2019, 58, e531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas, M.; Domingo, L.; Jansana, A.M.; Lafuente, E.M.; Civit, A.M.; García-Pérez, L.; de la Vega, C.M.L.; Cots, F.; Sala, M.; Castells, X. Cost-effectiveness Analysis of Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters Versus Central Venous Catheters for in-Hospital Parenteral Nutrition. J. Patient Saf. 2022, 18, e1109–e1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Verma, R.; Dhiman, R.K.; Rajsekhar, K.; Prinja, S. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis and Decision Modelling: A Tutorial for Clinicians. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2019, 10, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Kuntz et al., “Overview of Decision Models Used in Research,” 2013. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK127474/. (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Briggs, A. “StAtistical Issues in Economic Evaluations,” Encyclopedia of Health Economics; 2014; pp. 352–361. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, P.J.; Kim, D.D.; Trikalinos, T.A.; Sculpher, M.J.; Salomon, J.A.; Prosser, L.A.; Owens, D.K.; Meltzer, D.O.; Kuntz, K.M.; Krahn, M.; et al. Future Directions for Cost-effectiveness Analyses in Health and Medicine. Med Decis. Mak. 2018, 38, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, H.; Niu, M.; Zhu, X.; Cai, J.; Wang, X. Health-related quality of life before and after hematopoietic stem cell transplant: evidence from a survey in Suzhou, China. Hematology 2018, 23, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choong, S.H.C.; Poon, M.M.; Soh, T.G.; Lieow, J.; Tan, L.K.; Koh, L.P.; Chng, W.-J.; Lee, Y.M.; Lee, J.S.X.; Ramos, D.G.; et al. Use of Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC) for the Infusion of Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Products Is Safe and Effective. Blood 2020, 136, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godino, C.; Scotti, A.; Marengo, A.; Battini, I.; Brambilla, P.; Stucchi, S.; Slavich, M.; Salerno, A.; Fragasso, G.; Margonato, A. Effectiveness and ost-efficacy of iuretics ome dministration via eripherally nserted entral enous atheter in atients with nd- tage eart ailure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2022, 365, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health economic evaluation: Important principles and methodology. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/lary.23943?saml_referrer. (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Buetti, N.; Marschall, J.; Drees, M.; Fakih, M.G.; Hadaway, L.; Maragakis, L.L.; Monsees, E.; Novosad, S.; O’grady, N.P.; Rupp, M.E.; et al. Strategies to prevent central line-associated bloodstream infections in acute-care hospitals: 2022 Update. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiology 2022, 43, 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tong, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Gao, H.; Yu, P.; Lv, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, G.; et al. Effectiveness of antimicrobial-coated central venous catheters for preventing catheter-related blood-stream infections with the implementation of bundles: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2018, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, H.; Benjamin, R.; Chatzinikolaou, I.; Alakech, B.; Richardson, D.; Mansfield, P.; Dvorak, T.; Munsell, M.F.; Darouiche, R.; Kantarjian, H.; et al. Long-Term Silicone Central Venous Catheters Impregnated With Minocycline and Rifampin Decrease Rates of Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection in Cancer Patients: A Prospective Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 3163–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, N.M.; Chaiyakunapruk, N.; O'Riordan, E.; Pau, W.S.C.; Saint, S. Catheter impregnation, coating or bonding for reducing central venous catheter-related infections in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2018, CD007878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, N.; Maki, D.G. Risk of Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection With Peripherally Inserted Central Venous Catheters Used in Hospitalized Patients. Chest 2005, 128, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Leech, A.; Kim, D.D.; Cohen, J.T.; Neumann, P.J. Are low and middle-income countries prioritising high-value healthcare interventions? BMJ Glob. Heal. 2020, 5, e001850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, T.; Liu, G.G.; Kim, D.D.; Neumann, P.J. Taking stock of cost-effectiveness analysis of healthcare in China. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2019, 4, e001418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, L.; Xiao, K.; Zhu, H.; Luo, L. The impacts of public hospital comprehensive reform policies on hospital medicine cost, revenues and healthcare expenditures 2014–2019: An analysis of 103 tertiary public hospitals in China. Front. Heal. Serv. 2023, 3, 1079370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Observation Item | Study (n=113) n (%) |

Control (n=111) n (%) |

Total (N=224) n (%) |

P-Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.513 | ||||

| Male | 71 (62.83%) | 65 (58.56%) | 136 (60.71%) | ||

| Female | 42 (37.17%) | 46 (41.44%) | 88 (39.29%) | ||

| Puncture | arm | 0.605 | |||

| Left arm | 42 (37.17%) | 45 (40.54%) | 87 (38.84%) | ||

| Right arm | 71 (62.83%) | 66 (59.46%) | 137 (61.16%) | ||

| Catheter size | 0.834 | ||||

| 4.0-4.5 French | 55 (48.67%) | 52 (47.27%) | 107 (47.98%) | ||

| 5.0-5,0 French | 58 (51.33%) | 58 (52.73%) | 116 (52.02%) | ||

| Catheter lumen | 0.894 | ||||

| Single lumen | 56 (49.56%) | 56 (50.45%) | 112 (50.00%) | ||

| Double lumen | 57 (50.44%) | 55 (49.55%) | 112 (50.00%) | ||

| Age† | 41.36 (±12.98) | 43.34 (±14.38) | 42.34 (±13.70) | 0.280 | |

| BMI† | 22.97 (±3.21) | 24.03 (±3.40) | 23.50 (±3.34) | 0.020 | |

| APTT† | 31.13 (±3.77) | 30.58 (±3.41) | 30.86 (±3.60) | 0.251 | |

| INR† | 1.05 (±0.10) | 1.06 (±0.13) | 1.06 (±0.11) | 0.852 | |

| Indwell Period (Days) † | 62.81 (±27.98) | 69.04 (±26.65) | 65.89 (±27.44) | 0.089 | |

| Clinical Outcomes | Study Group (n=112) n (%) | Control Group (n=108) n (%) | Total (n=220) n (%) |

P-Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLABSI | 0.076 | ||||

| Non-CLABSI | 112 (100.00%) | 105 (97.22%) | 217 (98.65%) | ||

| CLABSI | 0 (0.00%) | 3 (2.65%) | 3 (1.32%) | ||

| Unknown Fever | 0.449 | ||||

| No | 95 (84.82%) | 85 (80.95%) | 180 (82.95%) | ||

| Yes | 17 (15.18%) | 20 (19.05%) | 32 (17.05%) | ||

| The 1st puncture success | 0.304 | ||||

| 1st puncture success | 112 (99.12%) | 108 (97.30%) | 220 (98.05%) | ||

| No 1st puncture success | 1 (0.88%) | 3 (2.70%) | 4 (1.95%) | ||

| Other local complications | 0.449 | ||||

| Non complications | 95 (84.82%) | 85 (80.95%) | 180 (82.95%) | ||

| Catheter-related complications | 17 (15.18%) | 20 (19.05%) | 37 (17.05%) | ||

| Catheter withdraw types | 0.411 | ||||

| Withdraw as planned | 71 (69.61%) | 77 (74.76%) | 148 (72.20%) | ||

| Withdraw with complication | 31 (30.39%) | 26 (25.24%) | 57 (27.80%) | ||

| Model Input | Base-Case Value | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | |||

| Price of Standard PICC (¥/piece) | 2100.00 | Industry data | |

| Estimated Price of AGBA PICC (¥/piece) | 2300.00 | Industry data | |

| Catheter maintenance (¥/per patient) | 2100.11 | Study data | |

| Catheter insertion/replacement (¥/per patient) | 364.25 | Study data | |

| CLABSI Diagnosis (¥/per time) | 1332.77 | Study data | |

| CLABSI Treatment (¥/per time) | 87147.08 | Study data | |

| Hospitalization per day in Beijing Class 3A hospital (¥/per bed per day) | 200.00 | Supplementary Materials | |

| QALY of pre-treatment | 0.65 | Liang Y, Wang H, et al., 2018 [27] | |

| QALY of treatment | 0.90 | Liang Y, Wang H, et al., 2018 [27] | |

| Length of stay, day | |||

| Patient with CLABSI | 20.6 | Study data | |

| Patient without CLABSI | 11.2 | Study data | |

| Clinical Outcomes | Study Group (n=112) | Control Group (n=108) | P-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs | Effectiveness | Probability | Costs | Effectiveness | Probability | ||

| Total expense | 62,817.79 | 0.90 | 100.00% | 102,861.57 | 0.89 | 100.00% | <0.05 |

| 1st time puncture unsuccess | 17,328.50 | 0.65 | 0.98% | 18,928.50 | 0.65 | 2.91% | |

| CLABSI | 314,204.50 | 0.90 | 0.00% | 444,404.50 | 0.9 | 2.91% | |

| Unknown fever | 314,742.50 | 0.90 | 16.67% | 444,819.29 | 0.9 | 18.45% | |

| Other local catheter-related complications | 30,964.25 | 0.90 | 13.72% | 14,374.87 | 0.9 | 2.91% | |

| Complications free | 8,664.25 | 0.90 | 68.63% | 9,464.25 | 0.9 | 72.81% | |

| ICER (AGBA Coated PICC vs. Standard PICC) | -40043.78 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).