Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

14 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

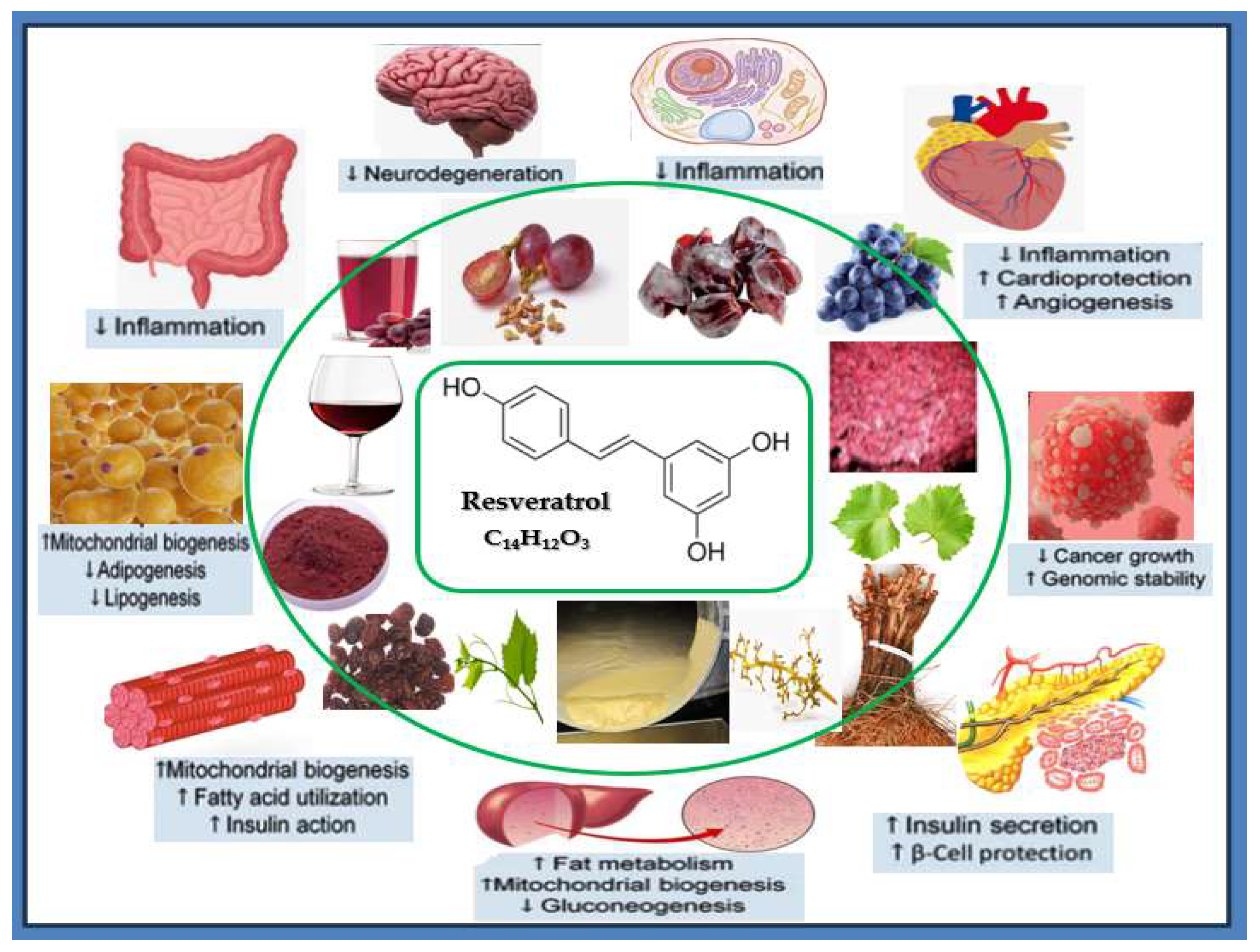

Resveratrol is the most important biopotential phytoalexin of the stilbene group (natural polyphenolic secondary metabolites), synthesized naturally by the action of biotic and abiotic factors on the plant. The yield of individual bioactive compounds isolated from grapevine components, products and by-products is directly dependent on the conditions of the synthesis, extraction and identification techniques used. Modern methods of synthesis and extraction, as well as identification techniques, are centred on the use of non-toxic solvents that have the advantages of the realisation of rapid extractions, maintenance of optimal parameters, and low energy consumption, being a challenge with promising results for various industrial applications. Actionable advances in identifying and analysing stilbenes consist of techniques for coupling synthesis/extraction/identification methods that have proven accurate, reproducible and efficient. The main challenge remains to keep resveratrol compositionally unaltered while increasing its microbiome solubility and stability as a nutraceutical in the food industry.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods of Synthesis and Extraction

2.1. Synthesis and Chemical Extraction Methods

2.2. Synthesis and Natural Extraction Methods

2.2.1. Conventional Extraction (Maceration)

2.2.2. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction

2.2.3. Microwave-Assisted Extraction

2.2.4. Membrane Extraction

2.2.5. Supercritical Pressurized Fluid Extraction (SCFE)

2.2.6. Applying Electric Fields

2.2.7. Using the Box-Behnken Experimental Design (BBD) and Response Surface Methodology (RSM)

2.2.8. Other Methods

2.3. Biotechnological Synthesis and Extraction Methods

3. Identification Techniques

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HPLC | Hyght Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| HPLC-MS | HPLC- Mass Spectrometry |

| HPLC-UV | HPLC-Ultraviolet |

| HPLC-GC/MS | HPLC-Gass spectrometry/Mass spectrometry |

| HPLC-DAD(UV)/CAD | HPLC-Diode Array Detection (Ultraviolet)/charged aerosol detector |

| HPLC-ESI-MS/MS | HPLC-Electrospray Ionization-Mass Spectrometry-Mass Spectrometry /Mass Spectrometry |

| HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn | HPLC-Diode Array Detection-Electrospray Ionization-Mass Spectrometry |

| HPLC-DAD-QToF | HPLC-Diode Array Detection-quadrupole-time of flight Mass Spectrometry |

| UHPLC | Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography; |

| UPLC-FD | UPLC-Fluorescence Detection |

| UPLC-MS | UPLC-Mass Spectrometry |

| UHPLC-UV | UHPLC-Ultraviolet |

| UHPLC-UV-DAD-MS | UHPLC-Ultraviolet-Diode Array Detection-Mass Spectrometry |

| UHPLC-(ESI+)-QToF-MS | UHPLC- (Electrospray Ionization-+)-quadrupole-time of flight Mass Spectrometry |

| UHPLC-Orbitrap MS4 | UHPLC-Orbitrap mass spectrometry |

| UPLC-VION-IMS-QToF | UPLC-VION-IMS- quadrupole-time of flight Mass Spectrometry |

| LC-MS | Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| LC-ESI-QToF-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography-Electrospray Ionization-quadrupole-time of flight Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry |

| GSP/UV-A/HPLC | GSP/Ultraviolet-A/HPLC |

| DW | Dry weight |

| FW | Fresh weight |

| SOX | Soxhlet extraction |

| DoE | Design of Experiment |

| RSA | Radical scavenging activity |

| ACE | Angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| VCC | Vitamin C |

| TPC | The phenolic content |

| IPA | Isopropyl alcohol |

References

- Taillis, D.; Becissa, O.; Pébarthé-Courrouilh, A.; Renouf, E.; Palos-Pinto, A.; Richard, T.; Cluzet, S. Antifungal activities of a grapevine byproduct extract enriched in complex stilbenes and stilbenes metabolization by Botrytis cinerea. Journal of Agric. and Food Chem. 2023, 71(11), 4488-4497. [CrossRef]

- Pébarthé-Courrouilh, A.; Jaa, A.; Valls-Fonayet, J.; Da Costa, G.; Palos-Pinto, A.; Richard, T.; Cluzet, S. UV-exp osure decreases antimicrobial activities of a grapevine cane extract against Plasmopara viticola and Botrytis cinerea as a consequence of stilbene modifications—a kinetic study. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80(12), 6389-6399. [CrossRef]

- Zwingelstein, M.; Draye, M.; Besombes, J.L.; Piot, C.; Chatel, C. trans-Resveratrol and trans-ε-Viniferin in Grape Canes and Stocks Originating from Savoie Mont Blanc Vineyard Region: Pre-extraction Parameters for Improved Recovery. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7 (9), 8310–8316. [CrossRef]

- Labois, C.; Stempien, E., Schneider, J.; Schaeffer-Reiss, C.; Bertsch, C.; Goddard, M.L.; Chong, J. Comparative study of secreted proteins, enzymatic activities of wood degradation and stilbene metabolization in grapevine botryosphaeria dieback fungi. JoF 2021, 7(7), 568. [CrossRef]

- Pezet, R.; Cuenat, P. Resveratrol in wine: extraction from skin during fermentation and post-fermentation standing of must from Gamay grapes. AJEV 1996, 47(3), 287-290. [CrossRef]

- Bavaresco, L.; Flamini, R.; Sansone, L.; Van Zeller de Macedo Basto Gonçalves, M.I.; Civardi, S.; Gatti, M.; Vezzulli, S. Improvement of healthy properties of grapes and wine with specific emphasis on resveratrol. J. Wine Res. 2011, 22(2), 135-138. [CrossRef]

- Căpruciu R. Resveratrol in Grapevine Components, Products and By-Products—A Review. Horticulturae. 2025, 11(2), 111. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yuan, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; Xu, X.; Xu, X.; Hussain, D.; Ma, L.; Chen, D. Current analytical strategies for the determination of resveratrol in foods. Food Chem. 2024, 431, 137182. [CrossRef]

- Filipe, D.; Gonçalves, M.; Fernandes, H.; Oliva-Teles, A.; Peres, H.; Belo, I.; Salgado, J.M. Shelf-life performance of fish feed supplemented with bioactive extracts from fermented olive mill and winery by-products. Foods 2023, 12(2), 30. [CrossRef]

- Godos, J.; Romano, G.L.; Gozzo, L.; Laudani, S.; Paladino, N.; Dominguez Azpíroz, I.; Martínez López, N.M.; Giampieri, F.; Quiles, J.L.; Battino, M.; Galvano, F.; Filippo Drago, F.; Grosso, G. Resveratrol and vascular health: evidence from clinical studies and mechanisms of actions related to its metabolites produced by gut microbiota. Front. pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1368949. [CrossRef]

- Robb, E.L.; Stuart, J.A. trans-resveratrol as a neuroprotectant. Molecules 2010, 15(3), 1196-1212. [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, A.; Saucier, C.; Bisbal, C.; Lambert, K. Grape polyphenols in the treatment of human skeletal muscle damage due to inflammation and oxidative stress during obesity and aging: Early outcomes and promises. Molecules 2022, 27(19), 6594. [CrossRef]

- Chinraj, V., Raman, S. Neuroprotection by resveratrol: A review on brain delivery strategies for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 12(7), 001-017. [CrossRef]

- Gui, J.; Sun, X.; Wen, S.; Liu, X.; Qin, B.; Sang, M. Resveratrol protects dopaminergic neurons in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease by regulating the gut-brain axis via inhibiting the TLR4 signaling pathway. South. Med. J. 2024, 44(2), 270-279. [CrossRef]

- Bertelli, A.A.; Das, D.K. Grapes, wines, resveratrol, and heart health. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2009, 54(6), 468-476. [CrossRef]

- Sy, B.; Krisa, S.; Richard, T.; Courtois, A. Resveratrol, ε-viniferin, and vitisin B from vine: Comparison of their in vitro antioxidant activities and study of their interactions. Molecules 2023, 28(22), 7521. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.R.; Yang, Q.; Jiang, Y.X.; Chen, H.Q. Enhanced solubility, thermal stability and antioxidant activity of resveratrol by complexation with ovalbumin amyloid-like fibrils: Effect of pH. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 148(A), 109463. [CrossRef]

- Petsini, F.; Detopoulou, M.; Choleva, M.; Kostakis, I.K.; Fragopoulou, E.; Antonopoulou, S. Exploring the effect of resveratrol, tyrosol, and their derivatives on platelet-activating factor biosynthesis in U937 cells. Molecules 2024, 29(22), 5419. [CrossRef]

- Pang, Q.; Wang, C.; Li, B.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Gu, S.; Shi, X. Resveratrol-loaded copolymer nanoparticles with anti-neurological impairment, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities against cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17(1), 105393. [CrossRef]

- Gál, R.; Halmosi, R.; Gallyas, F. Jr.; Tschida, M.; Mutirangura, P.; Tóth, K.; Alexy, T.; Czopf, L. Resveratrol and beyond: The effect of natural polyphenols on the cardiovascular system: A narrative review. Biomedicines 2023, 11(11), 2888. tps://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11112888.

- Fernández Conde, M.E.; Cortiñas Rodriguez, J.A.; Taglinao, L.; Bisarya, D.; Rodríguez Pérez, L. Exploring the Versatile Nature of Resveratrol: A Comprehensive Review. Preprints 2024, 2024041394.

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, D.; Liu, D.; Zhu, B. Food-grade encapsulated polyphenols: recent advances as novel additives in foodstuffs. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63(33), 11545-11560. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Malik, K.; Moore, J.M.; Kamboj, B.R.; Malik, S.; Malik, V.K.; Arya, S.; Singh, K.; Mahanta, S.; Bishnoi, D. K. Valorisation of Agri-Food Waste for Bioactive Compounds: Recent Trends and Future Sustainable Challenges. Molecules 2024, 29(9), 2055. [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.E.; Romaní, A.; Domingues, L. Overview of resveratrol properties, applications, and advances in microbial precision fermentation. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2024, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Bae, H. An overview of stress-induced resveratrol synthesis in grapes: perspectives for resveratrol-enriched grape products. Molecules 2017, 22(2), 294. [CrossRef]

- Krstonošić, M.A.; Sazdanić, D.; Ćirin, D.; Maravić, N.; Mikulić, M.; Cvejić, J.; Krstonošić, V. Aqueous solutions of non-ionic surfactant mixtures as mediums for green extraction of polyphenols from red grape pomace. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 33, 101069. [CrossRef]

- Avendaño-Godoy, J.; Ortega, E.; Urrutia, M.; Escobar-Avello, D.; Luengo, J.; von Baer, D.; Mardones, C.; Gómez-Gaete, C. Prototypes of nutraceutical products from microparticles loaded with stilbenes extracted from grape cane. Food Bioprod. Process. 2022, 134, 19-29. [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, G.P.; Grishin, Y.V.; Mosolkova, V.E.; Ogay, Y.A. Grape cane as a source of trans-Resveratrol and trans-Viniferin in the technology of biologically active compounds and its possible applications. In Proceedings of the NATO Science for Peace and Security Series A: Chemistry and Biology; Springer: Dordrecht, NLD (, 01 January 2013). [CrossRef]

- Pešić, M.B.; Milinčić, D.D.; Kostić, A.Ž.; Stanisavljević, N.S.; Vukotić, G.N.; Kojić, M.O.; Gašić, U.M.; Barać, M.B.; Stanojević, S.P; Popović, D.A.; Banjac, N.R.; Tešić, Ž.L. In vitro digestion of meat-and cereal-based food matrix enriched with grape extracts: How are polyphenol composition, bioaccessibility and antioxidant activity affected? Food Chem. 2019, 284, 28-44. [CrossRef]

- Šuković, D.; Knežević, B.; Gašić, U.; Sredojević, M.; Ćirić, I.; Todić, S.; Mutić, J.; Tešić, Ž. Phenolic profiles of leaves, grapes and wine of grapevine variety Vranac (Vitis vinifera L.) from Montenegro. Foods 2020, 9(2), 138. [CrossRef]

- Aliaño-González, M.J.; Richard, T.; Cantos-Villar, E. Grapevine cane extracts: Raw plant material, extraction methods, quantification, and applications. Biomolecules 2020, 10(8), 1195. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.P.; Sousa, A.M.; Gando-Ferreira, L.M.; Quina, M.J. Grape pomace as a natural source of phenolic compounds: solvent screening and extraction optimization. Molecules 2023, 28(6), 2715. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Perez, A.I.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; Andrés-Lacueva, C.; de la Torre-Boronat, M.C. Method for the quantitative extraction of resveratrol and piceid isomers in grape berry skins. Effect of powdery mildew on the stilbene content. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 210-215. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J.B., Orea, J.M., Ureña, A.G., Escribano, P., Osa, P.L.D.L., Guadarrama, A. Short anoxic treatments to enhance trans-resveratrol content in grapes and wine. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2007, 224, 373-378. [CrossRef]

- Peralbo-Molina, Á.; Priego-Capote, F.; de Castro, M.D.L. Comparison of extraction methods for exploitation of grape skin residues from ethanol distillation. Talanta 2012, 101, 292-298. [CrossRef]

- Casas, L.; Mantell, C.; Rodríguez, M.; de la Ossa, E.J.; Roldán, M.; De Ory, A.I.; Caro, I.; Blandino, A. Extraction of resveratrol from the pomace of Palomino fino grapes by supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Food Eng. 2010, 96(2), 304-308. [CrossRef]

- Takács, K.; Pregi, E.; Vági, E.; Renkecz, T.; Tátraaljai, D.; Pukánszky, B. Processing stabilization of polyethylene with grape peel extract: Effect of extraction technology and composition. Molecules 2023, 28(3), 1011. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, E.; Roriz, C.L.; Heleno, S.A.; Calhelha, R.; Dias, M.I.; Pinela, J.; Rosales-Conrado N.; León-Gonzále, M.E.; Ferreira, C.F.R.I.; Barros, L. Valorisation of black mulberry and grape seeds: Chemical characterization and bioactive potential. Food Chem. 2021, 337, 127998. [CrossRef]

- Guler, A. Effects of different maceration techniques on the colour, polyphenols and antioxidant capacity of grape juice. Food Chem. Volume 404, 2023 Part A, 134603. [CrossRef]

- Junqua, R.; Carullo, D.; Ferrari, G.; Pataro, G.; Ghidossi, R. Ohmic heating for polyphenol extraction from grape berries: An innovative prefermentary process. Oeno One 2021, 55(3), 39-51.10.20870/oeno-one.2021.55.3.4647.

- Bianchi, A.; Santini, G.; Piombino, P.; Pittari, E.; Sanmartin, C.; Moio, L.; Modesti, M.; Bellincontro, A.; Mencarelli, F. Nitrogen maceration of wine grape: An alternative and sustainable technique to carbonic maceration. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134138. [CrossRef]

- Beilankouhi, S.; Pourfarzad, A.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Rasouli, M.; Hamishekar, H. Identification of polyphenol composition in grape (Vitis vinifera cv. Bidaneh Sefid) stem using green extraction methods and LC-MS/MS analysis. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12(9), 6789-6798. [CrossRef]

- Prezioso, I.; Fioschi, G.; Rustioni, L.; Mascellani, M.; Natrella, G.; Venerito, P.; Gambacorta, G.; Paradiso, V.M. Influence of prolonged maceration on phenolic compounds, volatile profile and sensory properties of wines from Minutolo and Verdeca, two Apulian white grape varieties. LWT 2024, 192, 115698. [CrossRef]

- Petit, E.; Rouger, C.; Griffault, E.; Ferrer, A.; Renouf, E.; Cluzet, S. Optimization of polyphenols extraction from grapevine canes using natural deep eutectic solvents. Biomass Convers Bior. 2023, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Candemir, A.; Çalışkan Koç, G.; Dirim, S.N.; Pandiselvam, R. Effect of ultrasound pretreatment and drying air temperature on the drying characteristics, physicochemical properties, and rehydration capacity of raisins. Biomass Convers Bior. 2024, 14(16), 19623-19635. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, H.; Aliaño-González, M.J.; Cantos-Villar, E.; Faleiro, L.; Romano, A.; Medronho, B. Sustainable extraction of polyphenols from vine shoots using deep eutectic solvents: influence of the solvent, Vitis sp., and extraction technique. Talanta 2024, 267, 125135. [CrossRef]

- Contreras, M.D.M.; Feriani, A.; Gómez-Cruz, I.; Hfaiedh, N.; Harrath, A.H.; Romero, I.; Castro, E.; Tlili, N. Grapevine shoot extract rich in trans-resveratrol and trans-ε-viniferin: evaluation of their potential use for cardiac health. Foods 2023, 12(23), 4351. [CrossRef]

- Marianne, L.C.; Lucía, A.G.; de Jesús, M.S.M.; Leonardo, H.M.E.; Mendoza-Sánchez, M. Optimization of the green extraction process of antioxidants derived from grape pomace. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 37, 101396. [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Dubey, K.K.; Marathe, S.J.; Singhal, R. Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Bioactives from Fruit Waste and Its Therapeutic Potential. Food Biosci. 2023, 52, 102418. [CrossRef]

- Ueda, J.M.; Griebler, K.R.; Finimundy, T.C.; Rodrigues, D.B.; Veríssimo, L.; Pires, T.C.; João Gonçalves, J.; Fernandes, I.P.; Pereira, E.; Barros, L.; Heleno, S.A.; Calhelha, R.C. Polyphenol Composition by HPLC-DAD-(ESI-) MS/MS and Bioactivities of Extracts from Grape Agri-Food Wastes. Molecules 2023, 28(21), 7368. [CrossRef]

- Mir-Cerdà, A.; Carretero, I.; Coves, J.R.; Pedrouso, A.; Castro-Barros, C.M.; Alvarino, T.; Cortina, J.L.; Saurina, J.; Granados, M.; Sentellas, S. Recovery of Phenolic Compounds from Wine Lees Using Green Processing: Identifying Target Molecules and Assessing Membrane Ultrafiltration Performance. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159623. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Jeong, Y.J.; Park, S.C.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y.G.; Shin, G.; Jeong, H.J.; Ryu, Y.B.; Lee, J.; Lee, O.R.; Jeong, J.C.; Kim, C.Y. Highly efficient bioconversion of trans-resveratrol to δ-viniferin using conditioned medium of grapevine callus suspension cultures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23(8), 4403. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Castello, E.M.; Conidi, C.; Cassano, A.A. Membrane-Assisted green strategy for purifying bioactive compounds from extracted white wine lees. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 336, 126183. [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, R.; Arun Prasath, V.; Karpoora Sundara Pandian, N.; Patra, A.; Sharma, P.; Arulkumar, M.; Sivaranjani, S.; Govindarasu, P. Investigating the influence of pin-to-plate atmospheric cold plasma on the physiochemical, nutritional, and shelf-life study of two raisins varieties during storage. J. FOOD MEAS. CHARACT. 2024, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Melo, F.D.O.; Ferreira, V.C.; Barbero, G.F.; Carrera, C.; Ferreira, E.D.S.; Umsza-Guez, M.A. Extraction of bioactive compounds from wine lees: A systematic and bibliometric review. Foods 2024, 13(13), 2060. [CrossRef]

- Agostini, F.; Bertussi, R.A.; Agostini, G.; Atti Dos Santos, A.C.; Rossato, M.; Vanderlinde, R. Supercritical extraction from vinification residues: fatty acids, α-tocopherol, and phenolic compounds in the oil seeds from different varieties of grape. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012(1), 790486. [CrossRef]

- Sazdanić, D.; Krstonošić, M.A.; Ćirin, D.; Cvejić, J.; Alamri, A.; Galanakis, C.M.; Krstonošić, V. Non-ionic surfactants-mediated green extraction of polyphenols from red grape pomace. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2023, 32, 100439. [CrossRef]

- Chinnappan, B.A.; Krishnaswamy, M.; Xu, H.; Hoque, M.E. Electrospinning of biomedical nanofibers/nanomembranes: effects of process parameters. Polymers 2022, 14(18), 3719. [CrossRef]

- Carpentieri, S.; Ferrari, G.; Pataro, G. Pulsed electric fields-assisted extraction of valuable compounds from red grape pomace: process optimization using response surface methodology. Front. nutr. 2023, 10, 1158019. [CrossRef]

- Paczkowska-Walendowska, M.; Miklaszewski, A.; Michniak-Kohn, B.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. The antioxidant potential of resveratrol from red vine leaves delivered in an electrospun nanofiber system. Antioxidants 2023, 12(9), 1777. [CrossRef]

- Peternel, L.; Sokač Cvetnić, T.; Gajdoš Kljusurić, J.; Jurina, T.; Benković, M.; Radojčić Redovniković, I.; Tušek, A.J.; Valinger, D. The effects of drying and grinding on the extraction efficiency of polyphenols from grape skin: Process optimization. Processes 2024, 12(6), 1100. [CrossRef]

- Chengolova, Z.; Ivanov, Y.; Godjevargova, T. Comparison of identification and quantification of polyphenolic compounds in skins and seeds of four grape varieties. Molecules. 2023, 28(10), 4061. [CrossRef]

- Eshghi, S.; Karimi, R.; Shiri, A.; Karami, M.; Moradi, M. Effects of polysaccharide-based coatings on postharvest storage life of grape: Measuring the changes in nutritional, antioxidant and phenolic compounds. J. FOOD MEAS. CHARACT. 2022, 16(2), 1159-1170. [CrossRef]

- Markhali, F.S.; Teixeira, J.A. Extractability of oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol, tyrosol, verbascoside and flavonoid-derivatives from olive leaves using ohmic heating (a green process for value addition). Sustain. Food Prod. 2024, 2(2), 461–469. 10.1039/D3FB00252G.

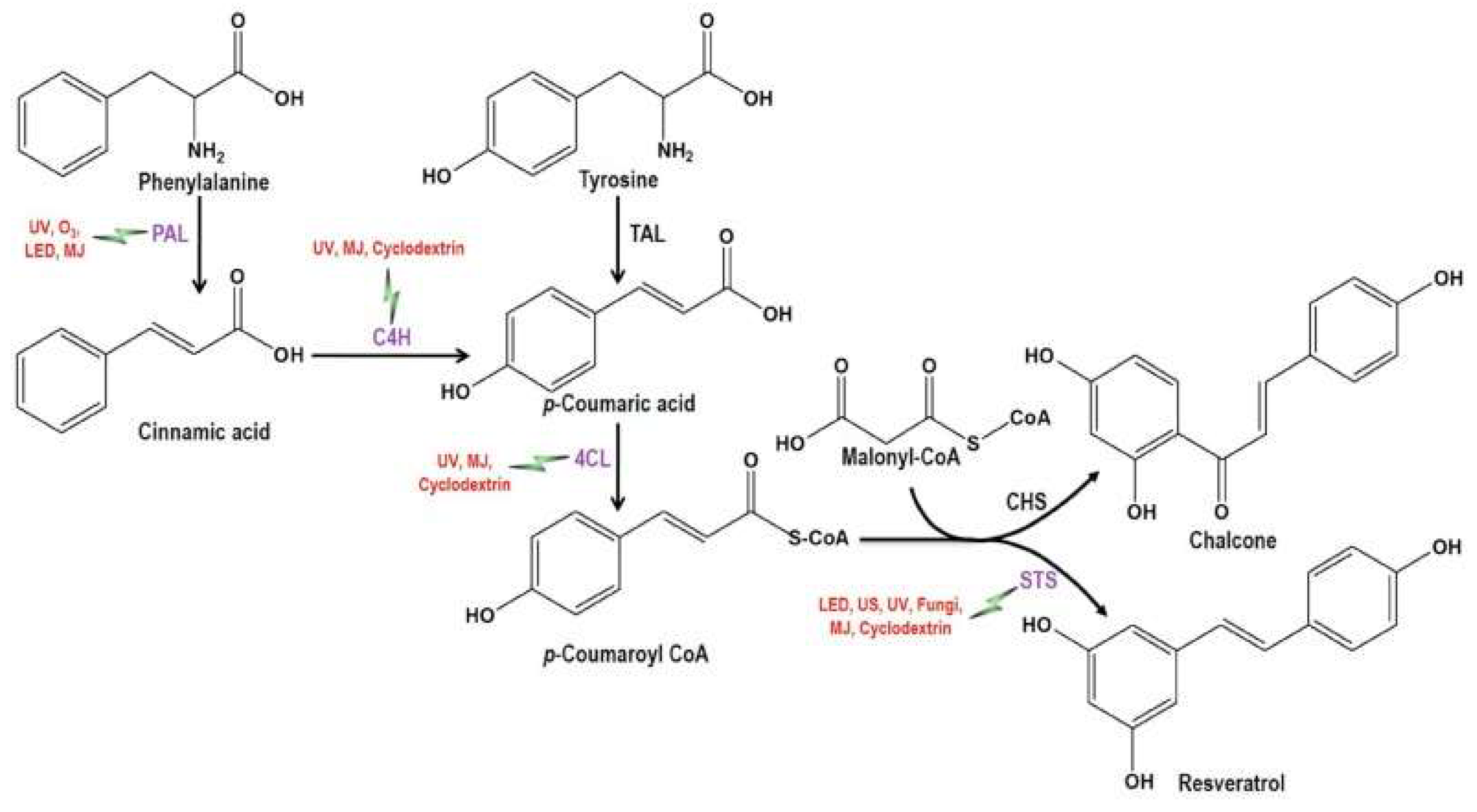

- Marant, B.; Crouzet, J.; Flourat, A.L.; Jeandet, P.; Aziz, A.; Courot, E. Key-enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of resveratrol-based stilbenes in Vitis spp.: a review. Phytochem. Rev. 2024, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Márquez, A.; Selles-Marchart, S.; Nájera, H.; Morante-Carriel, J.; Martínez-Esteso, M.J.; Bru-Martínez, R. Biosynthesis of piceatannol from resveratrol in grapevine can be mediated by cresolase-dependent ortho-hydroxylation activity of polyphenol oxidase. Plants 2024, 13(18), 2602. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Lien, Y.T.; Lin, W.S.; Nagabhushanam, K.; Ho, C.T.; Pan, M.H. Protective effects of piceatannol on DNA damage in Benzo [a] pyrene-induced human colon epithelial cells. J. Agric. food chem. 2023, 71(19), 7370-7381. [CrossRef]

- Piver, B.; Fer, M.; Vitrac, X.; Merillon, J.M.; Dreano, Y.; Berthou, F.; Lucas, D. Involvement of cytochrome P450 1A2 in the biotransformation of trans-resveratrol in human liver microsomes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004, 68, 773–782. [CrossRef]

- Haduch, A.; Bromek, E.; Kuban, W.; Daniel, W.A. The engagement of cytochrome P450 enzymes in tryptophan metabolism. Metabolites 2023, 13(5), 629. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Ahn, T.; Jung, H.C.; Pan, J.G.; Yun, C.H. Generation of the human metabolite piceatannol from the anticancer-preventive agent resveratrol by bacterial cytochrome P450 BM3. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2009, 37, 932–936. 10.1124/dmd.108.026484.

- Khatri, P.; Wally, O.; Rajcan, I.; Dhaubhadel, S. Comprehensive analysis of cytochrome P450 monooxygenases reveals insight into their role in partial resistance against Phytophthora sojae in soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 862314. [CrossRef]

- Flamini, R.; Zanzotto, A., de Rosso, M.; Lucchetta, G.; Dalla Vedova, A.; Bavaresco, L. Stilbene oligomer phytoalexins in grape as a response to Aspergillus carbonarius infection. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 93, 112-118. [CrossRef]

- Jeandet, P.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; Uddin, M.S.; Bru, R.; Clément, C.; Jacquard, C.; Nabavi S.F.; Khayatkashani, M.; Batiha, G.E. Khan, H.; Morkunas, I.; Trotta F.; Matencio, A.; Nabavi, S.M. Resveratrol and cyclodextrins, an easy alliance: Applications in nanomedicine, green chemistry and biotechnology. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 53, 107844.

- Gao, Y.; Fangel, J.U.; Willats, W.G.; Vivier, M.A.; Moore, J.P. Differences in berry skin and pulp cell wall polysaccharides from ripe and overripe Shiraz grapes evaluated using glycan profiling reveals extensin-rich flesh. Food Chem. 2021, 363, 130180. [CrossRef]

- Billet, K.; Malinowska, M.A.; Munsch, T.; Unlubayir, M.; de Bernonville, T.D.; Besseau, S., Courdavault, V.; Oudin, A.; Pichon, O.; Clastre, M.; Giglioli-Guivarc’h, N.; Lanoue, A. Stilbenoid-enriched grape cane extracts for the biocontrol of grapevine diseases. In: Mérillon, JM., Ramawat, K.G. (eds), Springer, Cham., Plant Defence: Biological Control. PIBC, 2020, volume 22. pp 215–239. [CrossRef]

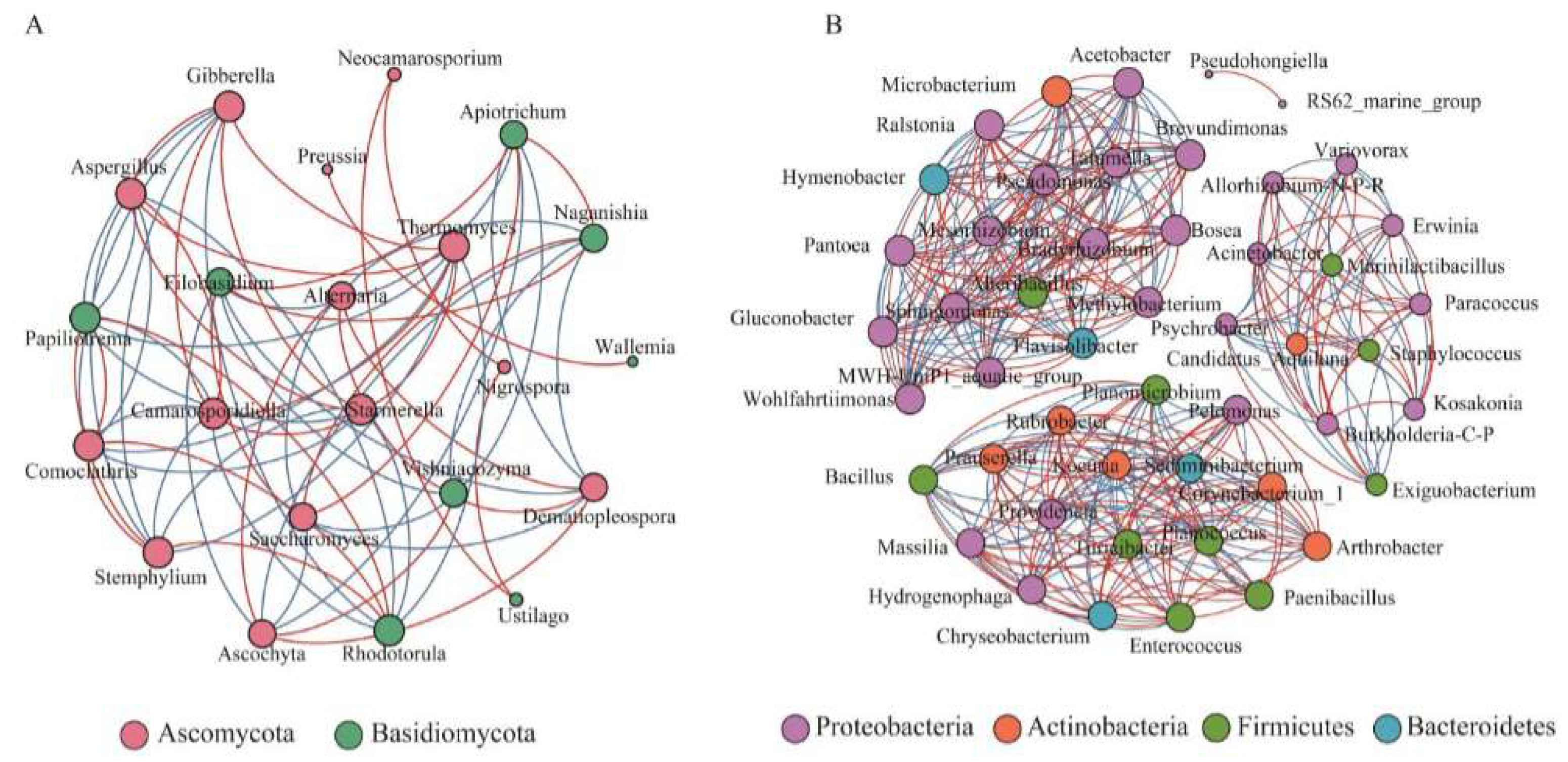

- Ding, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Li, H. Dynamic succession of natural microbes during the Ecolly grape growth under extremely simplified eco-cultivation. Foods 2024, 13(10), 1580. [CrossRef]

- Sinrod, A.J.; Shah, I.M.; Surek, E.; Balanovarile, D. Uncovering the promising role of grape pomace as a modulator of the gut microbiome: An in-depth review. Heliyon 2023, 9 (10), e20499. [CrossRef]

- Bejenaru, L.E.; Biţă, A.; Belu, I.; Segneanu, A.E.; Radu, A.; Dumitru, A.; Ciocâlteu, M.V.; Mogoșeanu, G.D.; Bejenaru, C. Resveratrol: A Review on the biological activity and applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14(11), 4534. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Kim, S.K.; Kim, M.H.; Lee, H.B.; Lee, J.S. Analysis of trans-resveratrol contents of grape and grape products consumed in Korea. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 2003, 35(5), 764-768.

- Moreno, A.; Castro, M.; Falqué, E. Evolution of trans- and cis-resveratrol content in red grapes (Vitis vinifera L. cv Mencía, Albarello and Merenzao) during ripening. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 227, 667-674. [CrossRef]

- Wijekoon, C.; Netticadan, T.; Siow, Y.L.; Sabra, A.; Yu, L.; Raj, P.; Prashar, S. Potential associations among bioactive molecules, antioxidant activity and resveratrol production in Vitis vinifera fruits of North America. Molecules 2022, 27(2), 336. [CrossRef]

- Vo, G.T.; Liu, Z.; Chou, O.; Zhong, B.; Barrow, C.J.; Dunshea, F.R.; Suleria, H.A. Screening of phenolic compounds in australian grown grapes and their potential antioxidant activities. Food Biosci. 2022, 47, 101644. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, O. Harmony in the vineyard: exploring the eco-chemical interplay of Bozcaada Çavuşu (Vitis vinifera L.) grape cultivar and pollinator varieties on some phytochemicals. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250(5), 1327-1339. [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Li, Q.; Ji, H.; Lou, H. Investigation of the distribution and season regularity of resveratrol in Vitis amurensis via HPLC–DAD–MS/MS. Food chem. 2014, 142, 61-65. [CrossRef]

- Tzanova, M.; Atanassova, S.; Atanasov, V.; Grozeva, N. Content of polyphenolic compounds and antioxidant potential of some Bulgarian red grape varieties and red wines, determined by HPLC, UV, and NIR spectroscopy. Agriculture 2020, 10(6), 193. [CrossRef]

- Erte, E.; Vural, N.; Mehmetoğlu, Ü.; Güvenç, A. Optimization of an abiotic elicitor (ultrasound) treatment conditions on trans-resveratrol production from Kalecik Karası (Vitis vinifera L.) grape skin. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58(6), 2121-2132. [CrossRef]

- Serni, E.; Tomada, S.; Haas, F.; Robatscher, P. Characterization of phenolic profile in dried grape skin of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Pinot Blanc with UHPLC-MS/MS and its development during ripening. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 114, 104731. [CrossRef]

- Capruciu, R.; Cichi, D.D.; Mărăcineanu, L.C.; Costea, D.C. The resveratrol content in black grapes skins at different development stages. Sci. Papers Ser. B Hortic. 2022, LXVI (1), 245-252. https://horticulturejournal.usamv.ro/pdf/2022/issue_1/Art39.pdf.

- Sun, Y.; Xi, B.; Dai, H. Effects of Water Stress on Resveratrol Accumulation and Synthesis in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’Grape Berries. Agronomy 2023, 13(3), 633. [CrossRef]

- Lai, G.; Fu, P.; He, L.; Che, J.; Wang, Q.; Lai, P.; Lu, J.; Lai, C. CRISPR/Cas9 mediated CHS2 mutation provides a new insight into resveratrol biosynthesis by causing a metabolic pathway shift from flavonoids to stilbenoids in Vitis davidii cells. Hortic. Res. 2024, 12(1), uhae268. [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Gao, M.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, B.; Kuang, H.; Wang, Z.; Yi,S.; Wang, B.; Fu, Y. Surfactant-assisted and ionic liquid aqueous system pretreatment for biocatalysis of resveratrol from grape seed residue using an immobilized microbial consortia. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45(3), e15279. [CrossRef]

- Kavgacı, M.; Yukunc, G.O.; Keskin, M.; Can, Z.; Kolaylı, S. Comparison of Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Properties of Pulp and Seeds of Two Different Grapes Types (Vitis vinifera L. and Vitis labrusca L.) Grown in Anatolia: The Amount of Resveratrol of Grape Samples. Chem. Afr. 2023, 6(5), 2463-2469. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.D.M.; Castillo Río, C.; Blanco González, S.I.; Menéndez, C.M. Phenolic profile changes of grapevine leaves infected with Erysiphe necator. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2024, 80(2), 397-403. [CrossRef]

- Tahmaz, H.; Küskü, D.Y. Investigation of some physiological and chemical changes in shoots and leaves caused by UV-C radiation as an abiotic stress source in grapevine cuttings. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 336, 113383. [CrossRef]

- Medrano-Padial, C.; Puerto, M.; Richard, T.; Cantos-Villar, E.; Pichardo, S. Protection and reversion role of a pure stilbene extract from grapevine shoot and its major compounds against an induced oxidative stress. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 79, 104393. [CrossRef]

- Kiene, M.; Zaremba, M.; Januschewski, E.; Juadjur, A.; Jerz, G.; Winterhalter, P. Sustainable in silico-supported ultrasonic-assisted extraction of oligomeric stilbenoids from grapevine roots using natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES) and stability study of potential ready-to-use extracts. Foods 2024, 13(2), 324. [CrossRef]

- Noronha, H.; Silva, A.; Garcia, V.; Billet, K.; Dias, A.C.; Lanoue, A.; Gallusci, P.; Gerós, H. Grapevine woody tissues accumulate stilbenoids following bud burst. Planta 2023, 258(6), 118. [CrossRef]

- Fermo, P.; Comite, V.; Sredojević, M.; Ćirić, I.; Gašić, U.; Mutić, J.; Baošić, R.; Tešić, Ž. Elemental analysis and phenolic profiles of selected italian wines. Foods 2021, 10(1), 158. [CrossRef]

- Bryl, A.; Falkowski, M.; Zorena, K.; Mrugacz, M. The role of resveratrol in eye diseases—a review of the literature. Nutrients 2022, 14(14), 2974. [CrossRef]

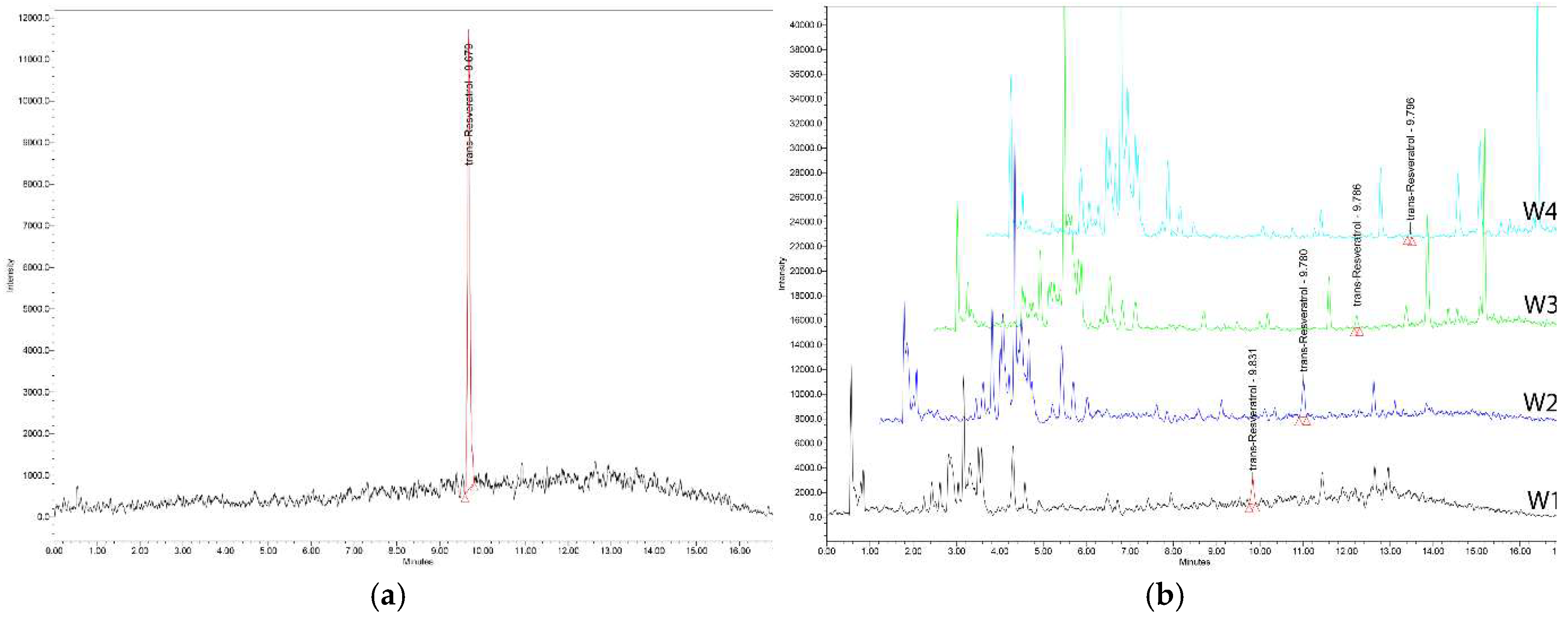

- Hoferer, L.; Rodrigues Guimarães Abreu, V. L.; Graßl, F.; Fischer, O.; Heinrich, M.R.; Gensberger-Reigl, S. Identification and quantification of resveratrol and its derivatives in franconian wines by comprehensive liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 3(6), 1057-1065.

- Balanov, P.E.; Smotraeva, I.V.; Abdullaeva, M.S.; Volkova, D.A.; Ivanchenko, O.B. Study on resveratrol content in grapes and wine products. In E3S Web Conf. EDP Sciences. 2021, volume 247, pp. 01063. [CrossRef]

- Rai, R.; Merrell, C.; Yokoyama, W.; Nitin, N. Infusion of trans-resveratrol in micron-scale grape skin powder for enhanced stability and bioaccessibility. Food Chem. 2021, 340, 127894. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Lei, J.; Shao, X.; Fan, Y.; Huang, W.; Lian, W.; Wang, C. Effect of Pretreatment and Drying on the Nutritional and Functional Quality of Raisins Produced with Seedless Purple Grapes. Foods 2024, 13(8), 1138. [CrossRef]

- Guamán-Balcázar, M.C.; Setyaningsih, W.; Palma, M.; Barroso, C.G. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of resveratrol from functional foods: Cookies and jams. Appl. Acoust. 2016, 103, 207-213. [CrossRef]

- Setyaningsih, W.; Guamán-Balcázar, M.D.C.; Oktaviani, N.M.D.; Palma, M. Response surface methodology optimization for analytical microwave-assisted extraction of resveratrol from functional marmalade and cookies. Foods. 2023; 12(2):233. [CrossRef]

- Sáez, V.; Pastene, E.; Vergara, C.; Mardones, C.; Hermosín-Gutiérrez, I.; Gómez-Alonso, S.; Gómez, M.V.; Theoduloz, C.; Riquelme, S.; von Baer, D. Oligostilbenoids in Vitis vinifera L. Pinot Noir grape cane extract: Isolation, characterization, in vitro antioxidant capacity and anti-proliferative effect on cancer cells. Food Chem. 2018, 1, 265, 101-110. [CrossRef]

- D’Eusanio, V.; Genua, F.; Marchetti, A.; Morelli, L.; Tassi, L. Characterization of some stilbenoids extracted from two cultivars of Lambrusco—Vitis vinifera Species: An opportunity to valorize pruning canes for a more sustainable viticulture. Molecules 2023, 28(10), 4074. [CrossRef]

- Kiene, M.; Zaremba, M.; Fellensiek, H.; Januschewski, E.; Juadjur, A.; Jerz, G.; Winterhalter, P. In silico-assisted isolation of trans-resveratrol and trans-ε-viniferin from grapevine canes and their sustainable extraction using natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES). Foods 2023, 12(22), 4184. [CrossRef]

- Ingrà, C.; Del Frari, G.; Favole, M.; Tumminelli, E.; Rossi, D.; Collina, S.; Ferrandino, A. Effects of growing areas, pruning wound protection products, and phenological stage on the stilbene composition of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) canes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72 (20), 11465-11479. [CrossRef]

- Kosović, E.; Topiař, M.; Cuřínová, P.; Sajfrtová, M. Stability testing of resveratrol and viniferin obtained from Vitis vinifera L. by various extraction methods considering the industrial viewpoint. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10(1), 5564. [CrossRef]

- Negro, C.; Aprile, A.; Luvisi, A.; De Bellis, L.; Miceli, A. Antioxidant activity and polyphenols characterization of four monovarietal grape pomaces from Salento (Apulia, Italy). Antioxidants 2021, 10(9), 1406. [CrossRef]

- Dujmić, F.; Kovačević Ganić, K.; Ćurić, D.; Karlović, S.; Bosiljkov, T.; Ježek, D.; Rajko Vidrih, R.; Hribar, J.; Zlatić, E.; Prusina, T.; Khubber, S.; Barba, F.J.; Brnčić, M. Non-thermal ultrasonic extraction of polyphenolic compounds from red wine lees. Foods 2020, 9(4), 472. [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández-Sobrino, R.; Margalef, M.; Torres-Fuentes, C.; Ávila-Román, J.; Aragonès, G.; Muguerza, B.; Bravo, F.I. Enzyme-assisted extraction to obtain phenolic-enriched wine lees with enhanced bioactivity in hypertensive rats. Antioxidants 2021, 10(4), 517. [CrossRef]

- Gaudin, K.; Valls-Fonayet, J.; Cordazzo, R.; Serafin, W.; Lafon, E.; Gaubert, A., Richard, T.; Cluzet, S. Separation of polyphenols by HILIC methods with diode array detection, charged aerosol detection and mass spectrometry: Application to grapevine extracts rich in stilbenoids. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1736, 465422. [CrossRef]

- Pezet, R.; Pont, V.; Cuenat, P. Method to determine resveratrol and pterostilbene in grape berries and wines using High-performance liquid chromatography and highly sensitive fluorimetric detection. J. Chromatogr. A 1994, 663(2), 191-197. [CrossRef]

- Revilla, E.; Ryan, J.M. Analysis of several phenolic compounds with potential antioxidant properties in grape extracts and wines by HPLC photodiode array detection without sample preparation. J. Chromatogr. A 2000, 881, 461–469. [CrossRef]

- Gambuti, A.; Strollo, D.; Ugliano, M.; Lecce, L.; Moio, L. trans-Resveratrol, quercetin, (+)-catechin, and (−)-epicatechin content in south Italian monovarietal wines: relationship with maceration time and marc pressing during winemaking. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52(18), 5747-5751. [CrossRef]

- Lago-Vanzela, E.S.; Da-Silva, R.; Gomes, E.; Garcia-Romero, E.; Hermosin-Gutierrez, I. Phenolic composition of the Brazilian seedless table grape varieties BRS Clara and BRS Morena. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59(15), 8314-8323. [CrossRef]

- Giuffrè, A.M. High performance liquid chromatography-diode array detector (HPLC-DAD) detection of trans-resveratrol: Evolution during ripening in grape berry skins. Afr. J. Agric. Res 2013, 8(2), 224-229.

- Göksel, Z., Kayahan, S., Atak, A., Şen, A., Tunçkal, C. Phenolic contents of some disease-resistant raisins (Vitis spp.). In XIII International Conference on Grapevine Breeding, Genetics and Management 1385, Cappadocia, Turkey (8 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mohammadparast, B.; Rasouli, M.; Eyni, M. Resveratrol contents of 27 grape cultivars. Appl. Fruit Sci. 2024, 66(3), 1053-1060. [CrossRef]

- Medouni-Adrar, S.; Medouni-Haroune, L.; Cadot, Y.; Soufi-Maddi, O.; Makhoukhe, A.; Boukhalfa, F.; Boulekbache-Makhlouf, L.; Madani, K. Phenolic compounds profiling in Ahmar Bou-Amar grapes extracted using two statistically optimized extraction methods. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 18(8), 6986-7002. [CrossRef]

- Milinčić, D.D.; Stanisavljević, N.S.; Kostić, A.Ž.; Soković Bajić, S.; Kojić, M.O.; Gašić, U.M.; Barać, M.B.; Stanojević, S.P.; Lj Tešić, Ž.; Pešić, M.B. Phenolic compounds and biopotential of grape pomace extracts from Prokupac red grape variety. LWT 2021, 138, 110739. [CrossRef]

| Fractions | Methods/ extracting substances |

Detection technique* | Content in resveratrol | References | |

| Grapevine components |

Whole grape | C₂H₃N/H2O (40:60, v/v) | HPLC-UV | 0.09235 mg/L, DW | [79] |

| C₂H₃N - CH₃COOH | HPLC-FL | 7–24 mg/L, DW | [80] | ||

| acidified water (0.1% H3PO4)/C₂H₃N | HPLC-GC/MS | 13.9 ± 2.87 mg/L, DW | [81] | ||

| 70% C2H5OH | LC-ESI-QToF-MS/MS | 227000 mg/L, FW | [82] | ||

| MeOH (70%) /H2O (8:2, v/v) | HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn | 4.04 mg/L, DW | [83] | ||

| Skin | MeOH | HPLC-ESI-MS/MS | 30.6 ± 1.7 mg/L, DW | [84] | |

| 1% HCl in MeOH | HPLC | 3.13 ± 0.33 to 14.57 ± 1.34 mg/L, FW | [85] | ||

| incubation time - 24 h, US application method-(P01), US frequency - 20 kHz, US treatment time - 60 min and ultrasonic intensity (UI) - 1.15 W cm−2 | HPLC | 180 ± 10 mg/L to 3580 ± 80 mg/L, DW | [86] |

||

| MeOH-deionized water (1:1) with 1 % CH₂O₂ (v/v) | UHPLC | 0.05 mg/L, FW | [87] | ||

| MeOH | HPLC | 0.065 to 7.119 mg/L, DW (cis-resveratrol) 0.633 to 9.152 mg/L, DW (trans-resveratrol) |

[88] | ||

| MeOH/C4H8O2 (1:1, v/v) |

HPLC | 0.667 mg/L, DW | [89] | ||

| 70% MeOH | UPLC-MS-MS | 2.76 mg/L, FW | [90] | ||

| Seed | MeOH | HPLC-ESI-MS/MS | 20.4 ± 0.7 mg/L, DW | [84] | |

| H2O-CH₂O₂-C₂H₃N (76.935/0.065/23, v/v/v) | UHPLC- MS/MS | 305.98 ± 0.23 mg/L, DW | [91] | ||

| Pulp | MeOH | HPLC-UV | 45 to 1018.9 mg/L, DW | [92] | |

| Stem | C2H5OH (5%, v/v) | HPLC | 680 to 1870 mg/L, DW | [36] | |

| 1. (H2O + microwave + ultrasound + atmospheric pressure); 2 . (H2O + microwave + ultrasound + reduced pressure) |

HPLC-ESI-MS/MS | 1121 ± 4.8 mg/L, DW | [42] | ||

| Leaf | MeOH | HPLC-ESI-MS/MS | 6.2 ± 0.1 mg/L, DW | [84] | |

| The (DoE) approach, the red vine leaf extract (50% MeOH, temperature 70 °C, and three cycles per 60 min) | HPLC | 0.306 ± 0.009 mg/L DW | [60] | ||

| 10 mL of 0.1 m HCl 80% MeOH solution was extracted with two consecutive 15-min cycles of sonication at 4 °C in total darkness | UPLC | 30-40mg/L FW−1 ×10−1 | [93] | ||

| UV-C treatment/MeOH | LC-MS/MS | 0.01997718-0.3578911798 mg/L, FW | [94] | ||

| 70% MeOH | UPLC-MS-MS | 4.22 mg/L, FW | [90] | ||

| Shoot | EC50 Caco-2 /EC50 HepG2-H2O2 |

HPLC | 14.74 and 29.47 mg/L, DW | [95] | |

| MeOH-H2O (80:20, v/v) | HPLC | 148.53 mg/L−1, DW | [46] | ||

| Root | MeOH | HPLC-ESI-MS/MS | 86.3 ± 2.5 mg/L, DW | [84] | |

| COSMO-RS-NADES | UHPLC-UV | 520–2470 mg/L, DW | [96] | ||

| Wood | Botrytis cinerea secretome | UHPLC-UV-DAD-MS | 9541 ± 16800 mg/L, DW | [1] | |

| Woody tissues | 80% MeOH | UPLC-MS | 69.1 to 436.5 mg/L, DW−1 | [97] | |

| Bud | 80% MeOH | UPLC-MS | 150 mg/L, DW−1 | [97] | |

| Grapes product |

Wine | C₂H₃N/H2O (40:60, v/v) | HPLC-UV | 0.1047 mg/L, DW | [79] |

| MeOH | UHPLC-orbitrap MS4 | 4.00 mg/L, DW (red wine) | [98] | ||

| Transepithelial diffusion | LC-MS | 0.361–1.972 mg/L, FW (red wine) 0–1.089 mg/L, FW (white wine) 0.29 mg/L, FW (rosé wine) |

[99] | ||

| MeOH | UHPLC- MS/MS | 0.07-2.61 mg/L, DW (cis-resveratrol) 0.05-3.82 mg/L, DW (trans-resveratrol) |

[100] | ||

| Juice | C₂H₃N/H2O (40:60, v/v) | HPLC-UV | 0.000091 mg/L, DW | [79] | |

| C₂H₆O/water solution (60:40, v/v) | HPLC | 4.4 to 7.0 mg/L, DW | [101] | ||

| Concentrated Juice | C₂H₆O/water solution (60:40, v/v) | HPLC | 12.4 to 21.3 mg/L, DW | [101] | |

| Grape Skin Powder | C₂H₆O/H2O (50%, v/v) | GSP/UV-A/HPLC | 250 mg/L, DW | [102] | |

| Raisin | HCl/MeOH/H2O, 1:80:19, v/v/v) | UPLC-VION-IMS-QToF | 16544000 ± 44000 mg/L, DW | [103] | |

| Jam | UP200S ultrasonic system optimised with: solvent composition (10–70% and 30–90% MeOH in H2O; solvent-to-solid ratio (10:1 - 40:1); ultrasonic probe diameter | UPLC-FD | 0.027 ± 0.01 to 1.760 ± 0.04 mg/L, DW | [104] | |

| Marmalade | BBD optimised with: solvent composition (60 - 100% and 10 - 70% MeOH in H2O); microwave power (250 - 750 W); solvent-to-solid ratio (20:5 - 60:5) | UHPLC-FD | 1.74 mg/L-1, DW | [105] | |

| By-products |

Grape canes |

C₂H₆O/H2O (80:20, v/v) | HPLC-DAD-Q-ToF | 227.07 mg/L−1, DW | [106] |

| The microencapsulation (by spray drying) using maltodextrin (MD) (10% w/v) and UV irradiation (254 nm) | HPLC | 679.6 ± 51.6 mg/L, DW | [27] | ||

| Sonicate/macerate -96% C₂H₆O (v/v) | HPLC-MS | 815.9 ± 153 mg/L, DW | [107] | ||

| COSMO-RS-calculations for NADES extraction combined with HPCC biphasic solvent | UHPLC-UV | 1.50 mg/L, DW | [108] | ||

| HPLC-UV-DAD | HPLC-ESI/MS | 890± 20 mg/L-1, DW (dormant bud) 610±10 mg/L-1, DW (second extended leaf) 200±70 mg/L-1, DW (sixth extended leaf and visible inflorescence) |

[109] | ||

| Grape pomace | C₂H₆O (5%, v/v) | HPLC | 190 to 1073 mg/L, DW | [36] | |

| Extracted by SOX and MAC in IPA | HPLC-DAD/MS |

0.042–0.653 mg/L, DW (trans-resveratrol) 0.05–0.35 mg/L, DW (cis-resveratrol) |

[110] | ||

| 100 mL of MeOH 80% acidified with CH₂O₂ 0.1% for one hour in an ultrasonic bath | HPLC/DAD/TOF | 100 ± 20 mg/L. DW | [111] | ||

| Wine lees | Conventional aqueous (CE) and non-conventional UAE | HPLC | 36360 mg/L, DW | [112] | |

| Enzyme-assisted extraction based on the hydrolysis of WL proteins | UHPLC-(ESI+)-Q-ToF-MS | 164.00 ± 0.80 mg/L, DW | [113] | ||

| Grapevine extracts |

MeOH/H2O (50:50, v/v) | HPLC-DAD(UV)/CAD | 36.75 mg/L−1, DW (CAD) 211.25 mg/L−1, DW (DAD/UV) |

[114] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).