Submitted:

12 February 2025

Posted:

14 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

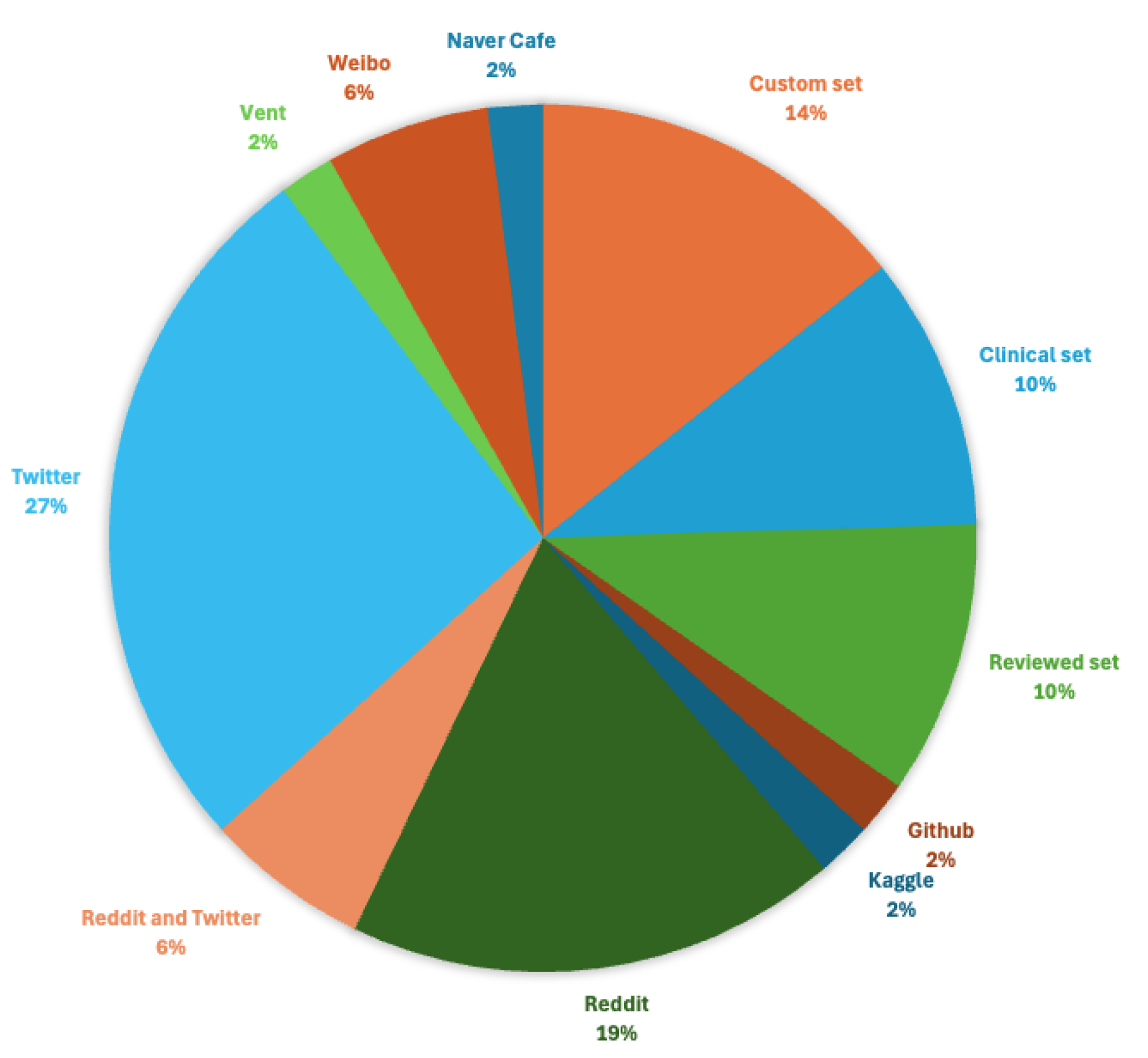

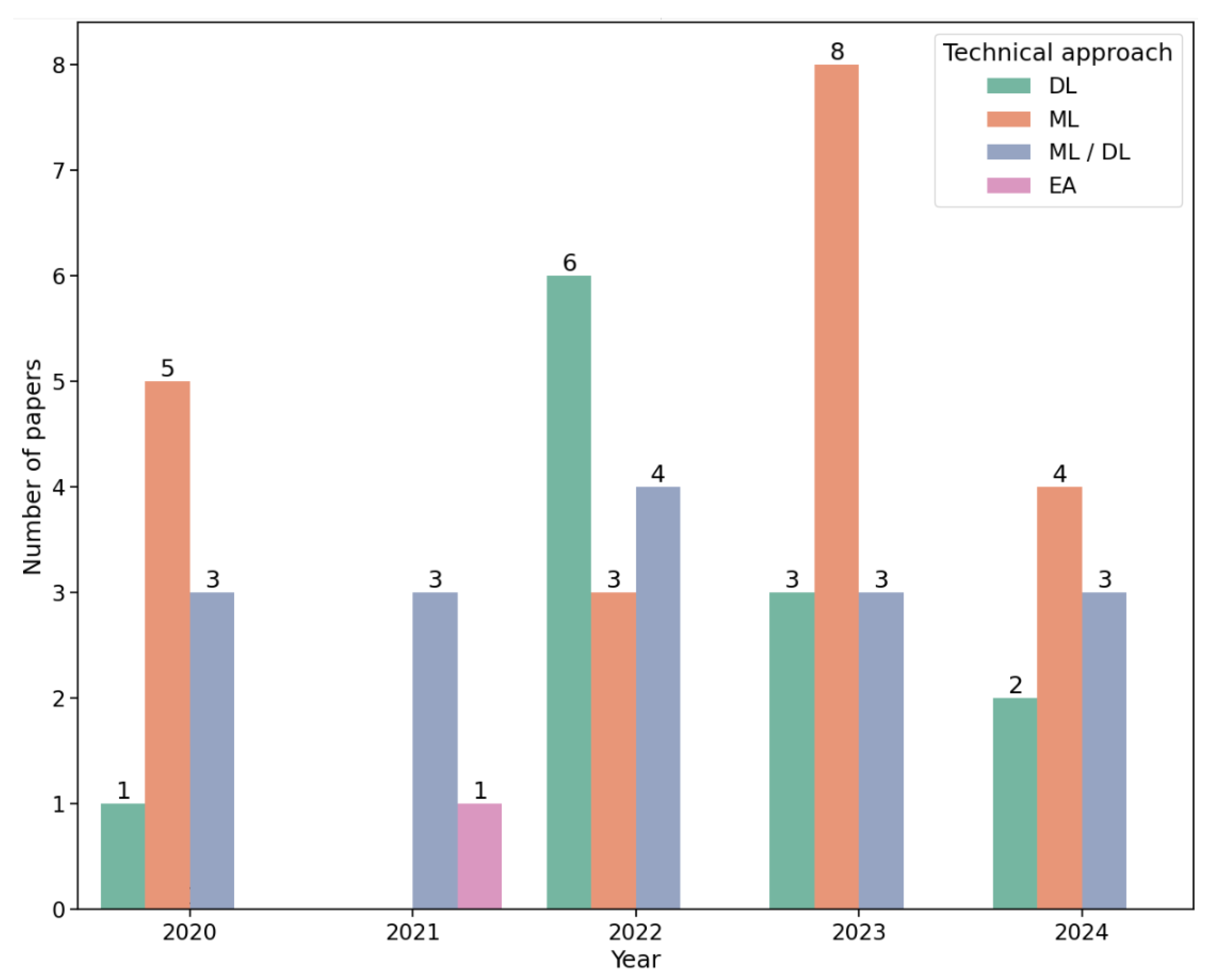

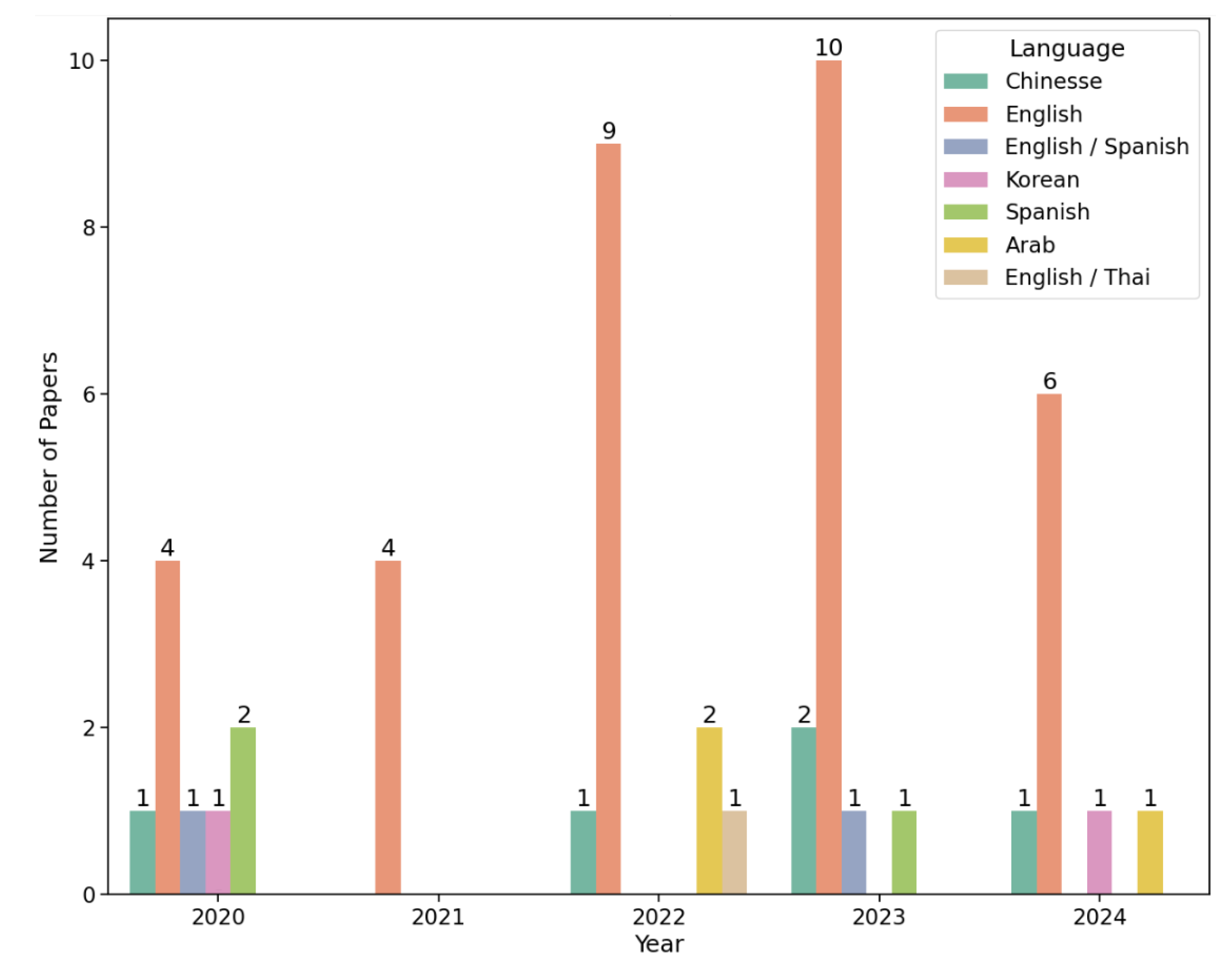

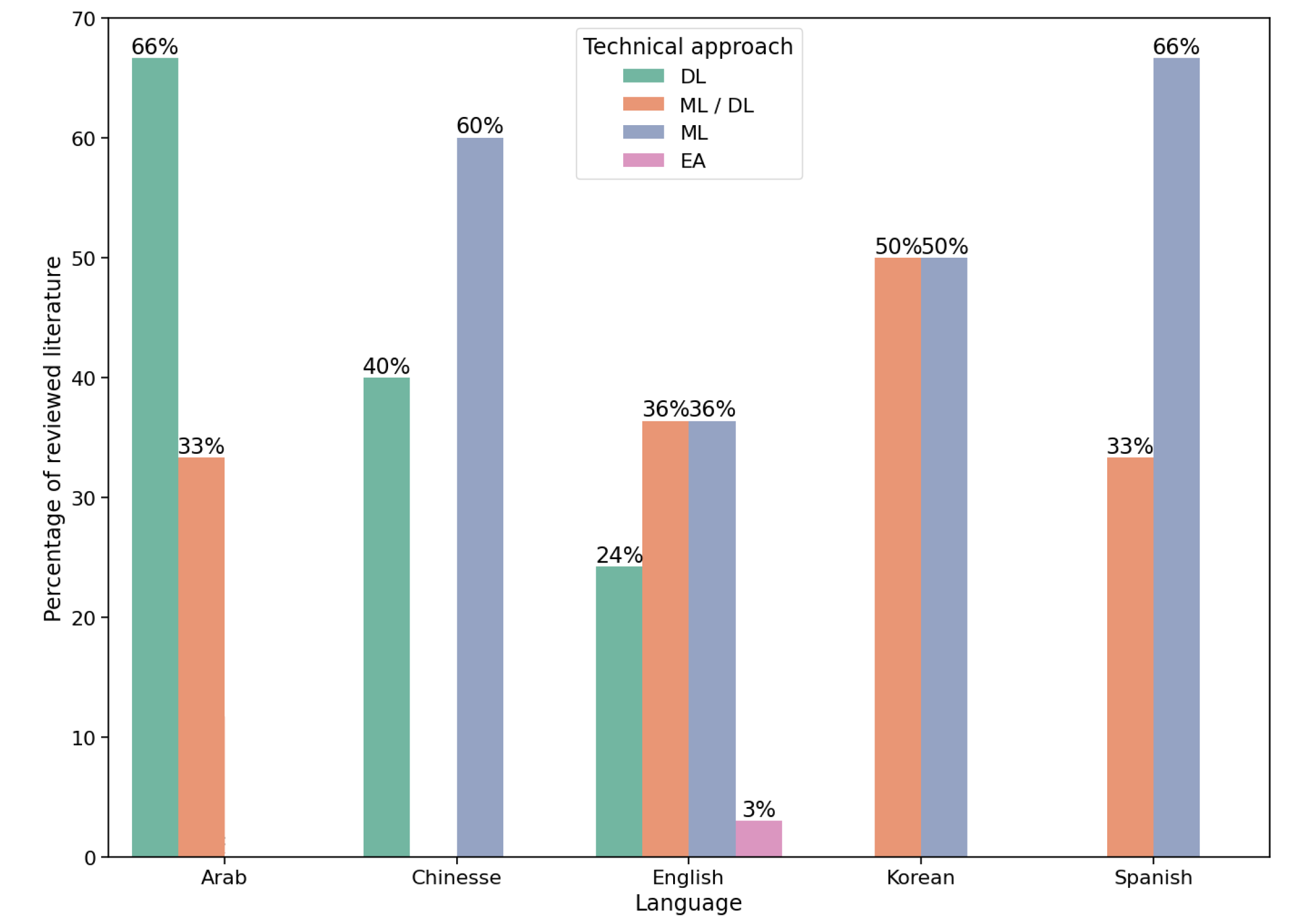

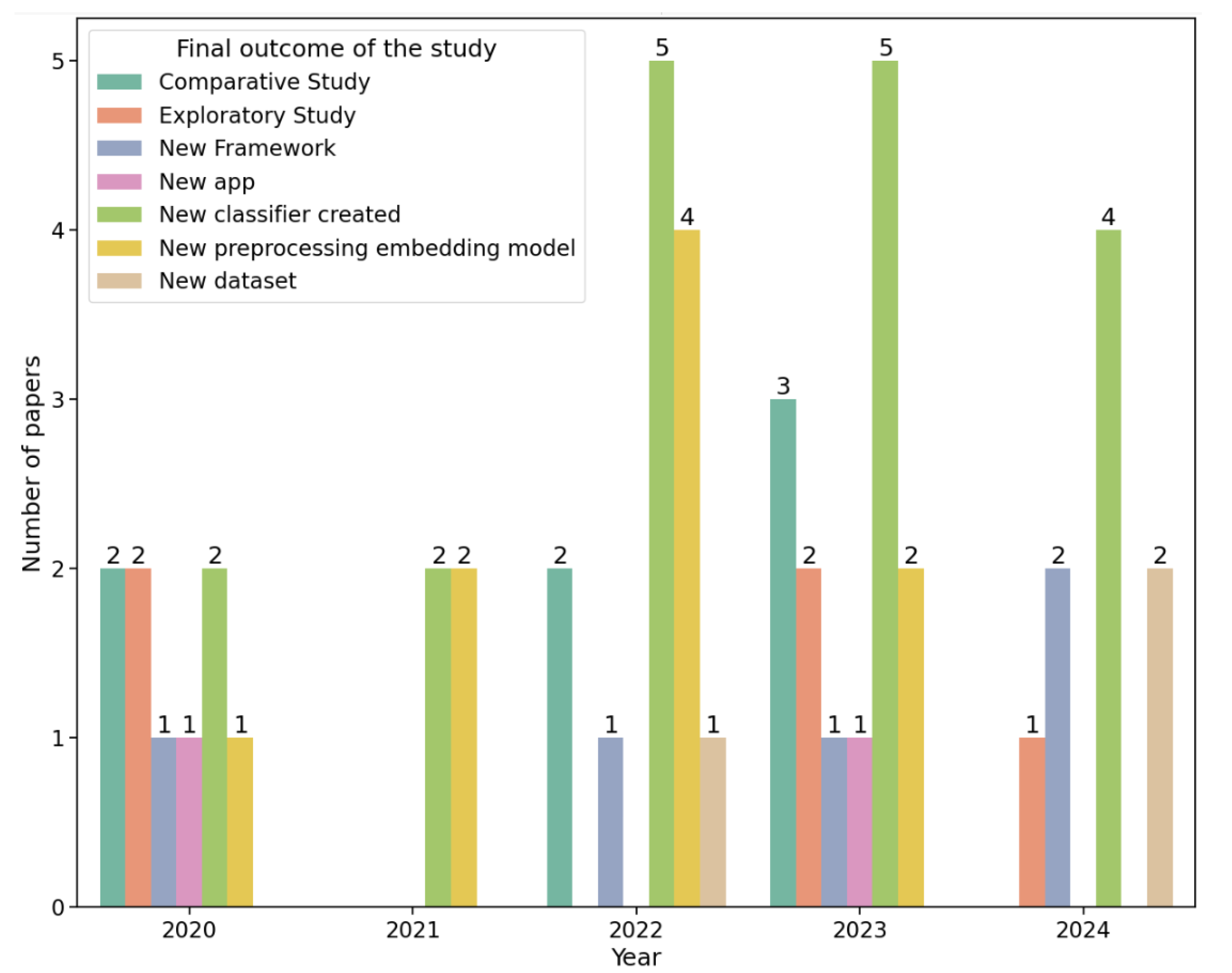

Suicide is a complex health concern that affects not only individuals but society as a whole. Its prevention is possible but to be effective it has to consider the medical and technological resources available for its evaluation. Nowadays, computational advancements have enabled new forms of study of this phenomenon. Particularly, the study of suicidal ideation using computer-based techniques primarily involves two main technical approaches: text-based classification and deep learning. Furthermore, it heavily relies on creating and using custom datasets with social media textual data. However, some publications have utilized public information (e.g. records from a particular healthcare provider) in their studies. In this paper, a comprehensive overview of current advancements in automatic suicidal ideation detection, focusing on computer science techniques from 2020 to 2024, is provided. Particularly, it evaluates existing and innovative methodologies, datasets, and limitations in the field to give a proper analysis based on the PRISMA methodology of the current state-of-the-art of this specific task.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Suicide attempt: Defined as a self-injurious behavior with inferred or actual intent to die. In addition, Yerly highlights the multifaceted nature of suicide by illustrating this concept as the intentional actions of ending one’s own life without achieving a fatal result [23].

- Death by suicide: Defined as the mortal outcome of a suicide attempt.

-

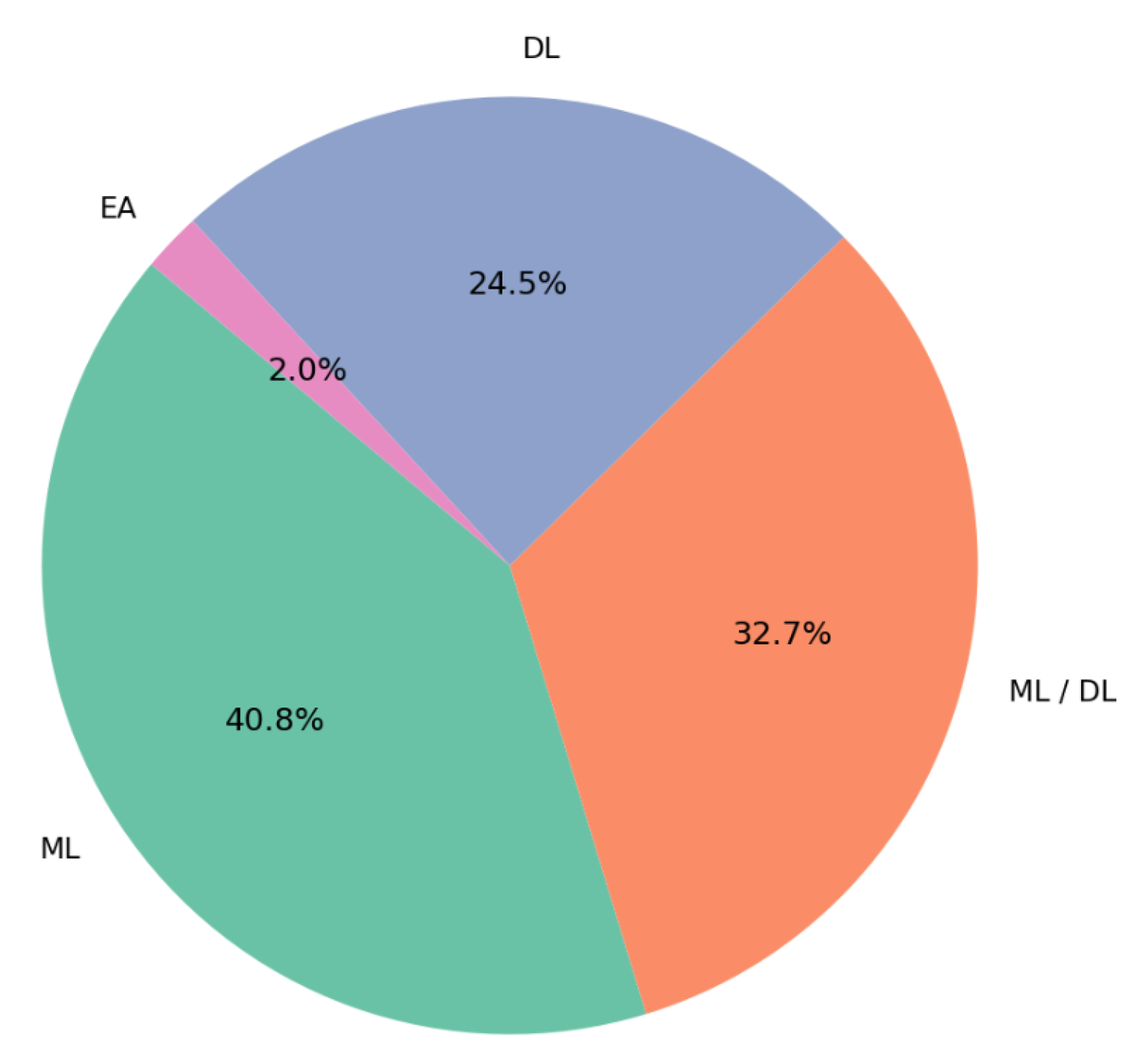

Text-based Classification: Based on Feature Engineering, the goal of this approach is to determine, via text-based interactions (e.g. social media posts), if a person has suicidal ideation. Such task is tackled using:

- -

- Tabular Features: This is structured data (statistical information or questionnaire responses) that can be employed as features for regression or classification analysis.

- -

- General Text Features: To handle unstructured data -that with no systematic order [39]- general features like N-gram features, knowledge-based features, syntactic features, context features, and class-specific features, are extracted via self-made vocabulary or dictionaries.

- -

- Affective Characteristics: Probably the most experimental approach since it combines specific psychological techniques (e.g. manual emotion categories) with the previous computational methods to perform a fine-grained sentiment analysis over suicide notes or blog streams. As a consequence of this, it is expected to better distinguish between a potentially suicidal person and a healthy one.

- Deep Learning: Taking advantage of automatic feature learning, this approach utilizes advanced methods based on Neural Networks to boost predictive performance. Consequently, these techniques indicate a more robust preliminary success in suicidal ideation understanding compared to traditional statistical methodologies as demonstrated by Haque R, Islam N., et al [40].

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy

- Limitation to peer-reviewed journal publications/articles.

- Publication date between 2020 and 2024 (inclusive).

-

Use of a similar syntax based on the PICo framework applied by Arowosegbe., et al, for the searched index terms [42], making a special inquiry in the top 6 most popular languages according to Webber [44]:(("Machine Learning" OR ML OR "Deep Learning" OR DL OR "Natural Language Processing" OR NLP OR "Artificial Intelligence" OR AI) AND (Suicidality OR "Suicidal Ideation" OR Ideation OR Suicide) AND (English OR Spanish OR French OR Russian OR Arabic OR Chinese))

2.2. Databases

2.3. Eligibility and Inclusion criteria

2.4. Screening

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

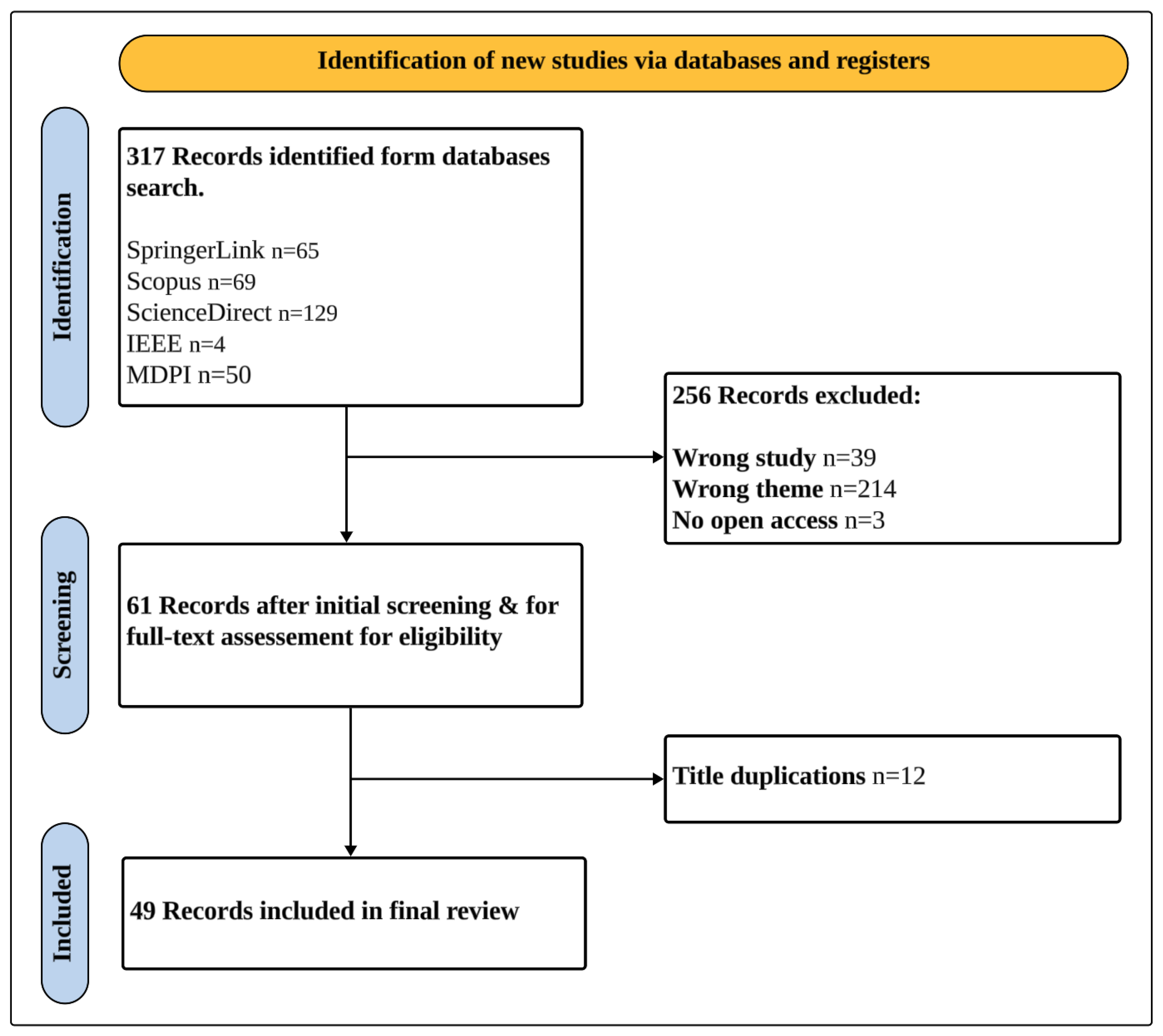

3.1. Study Selection

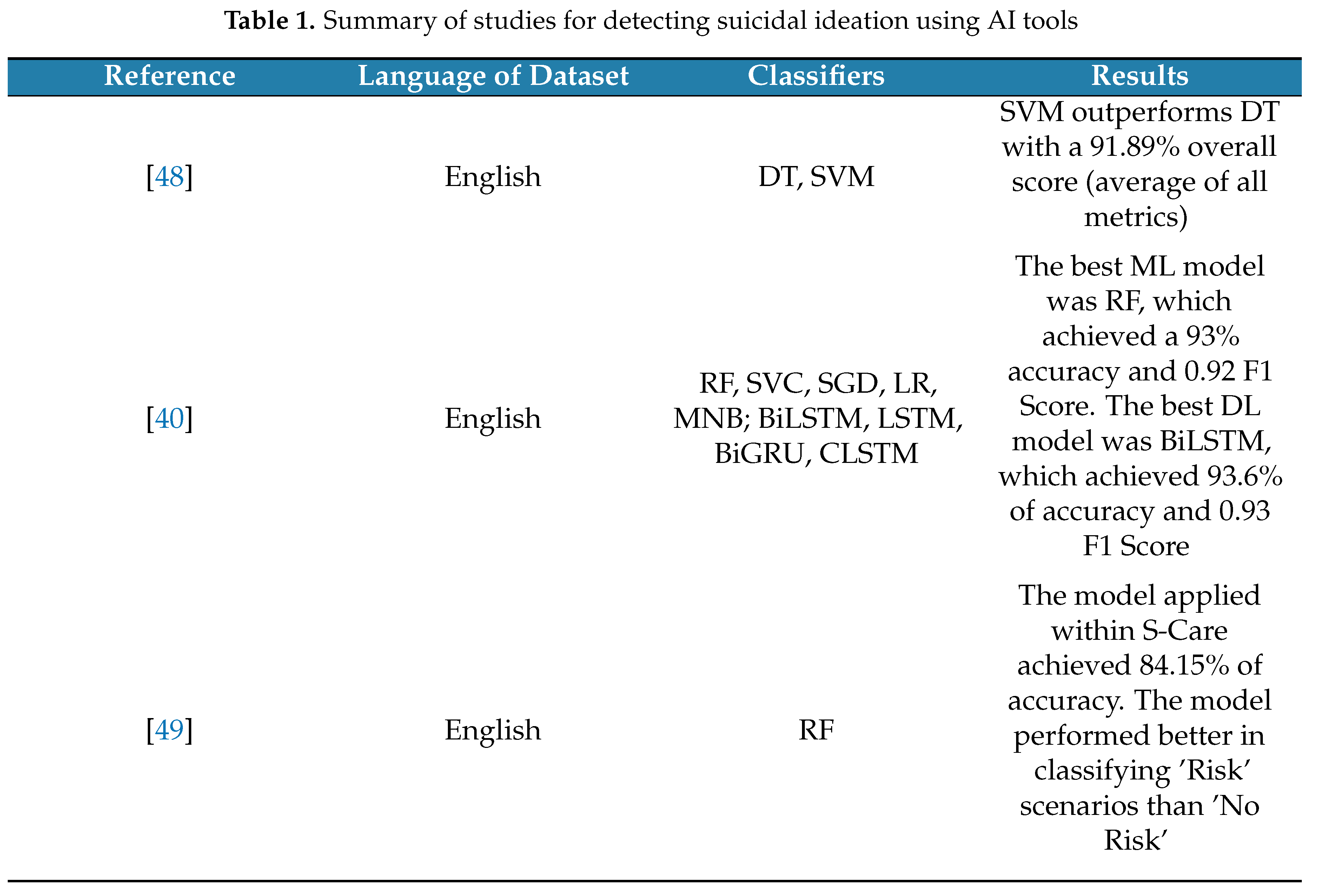

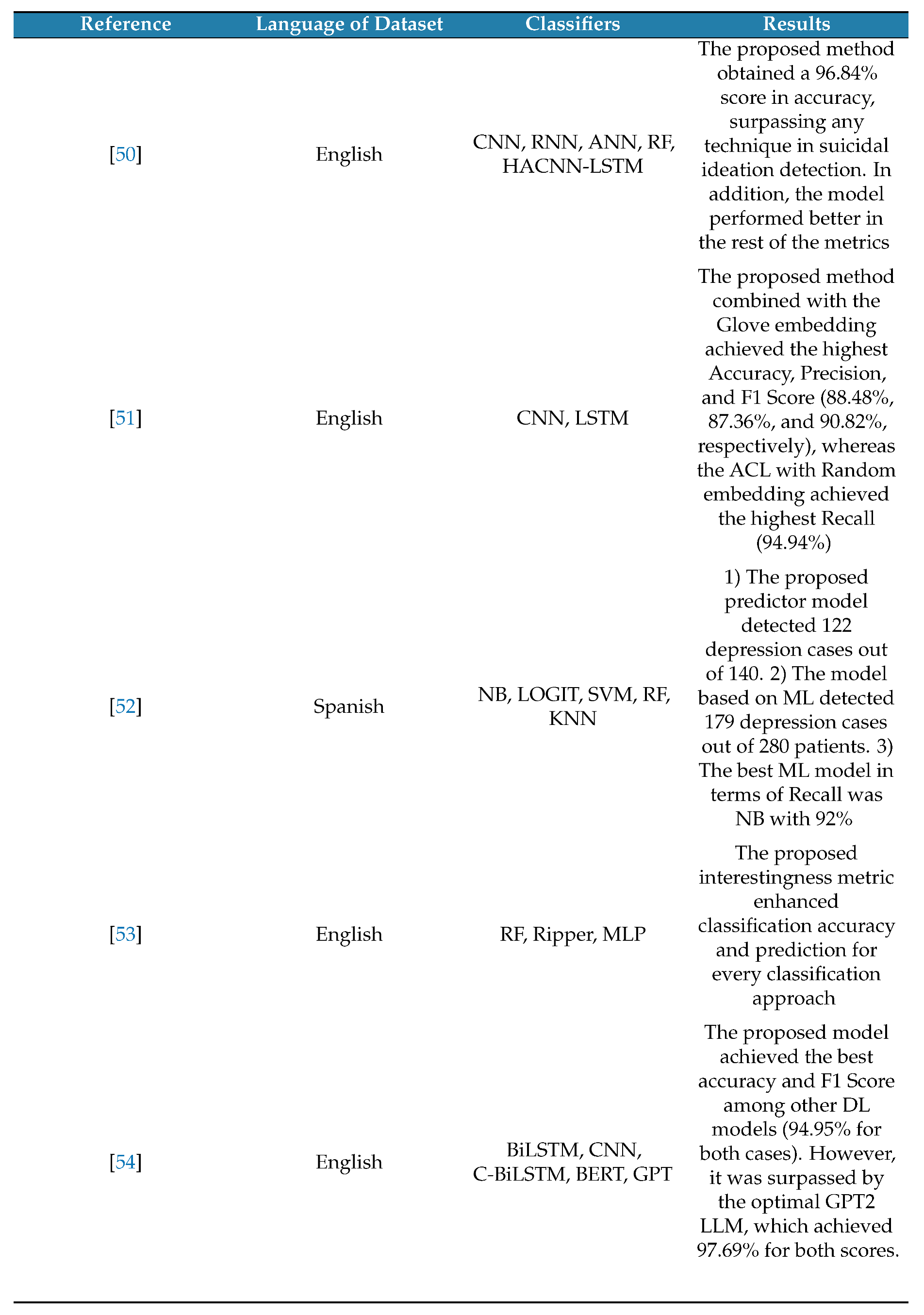

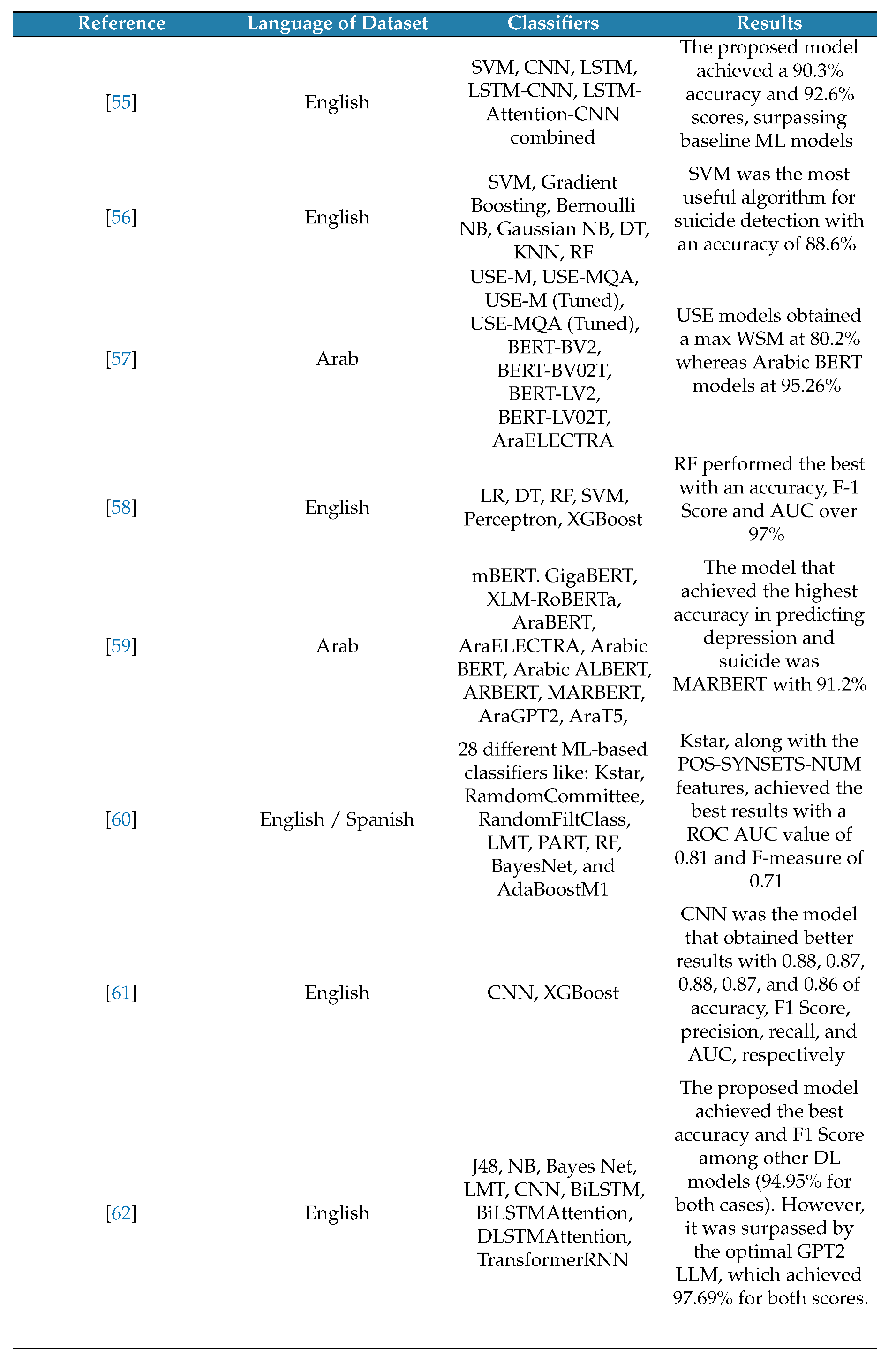

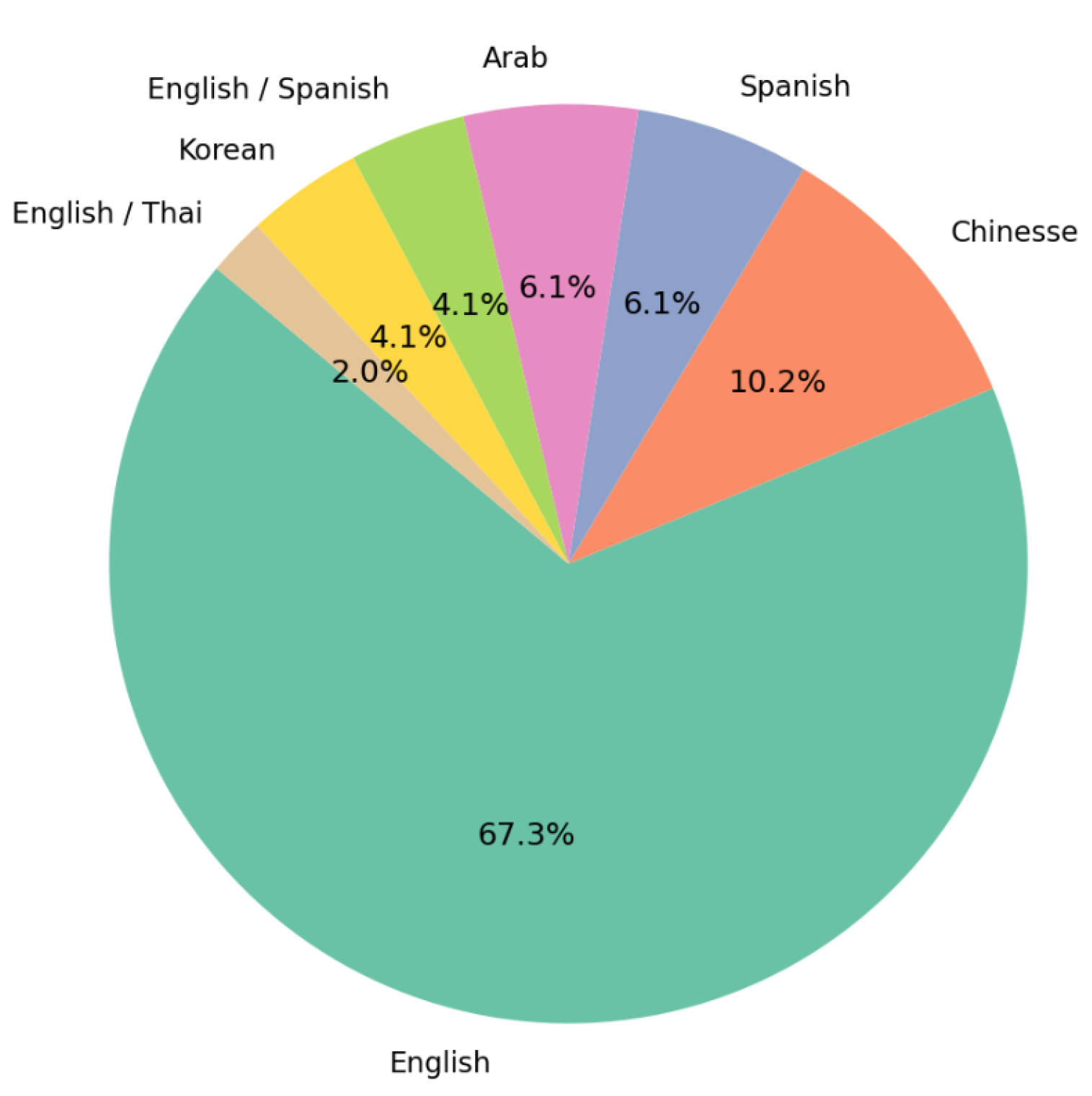

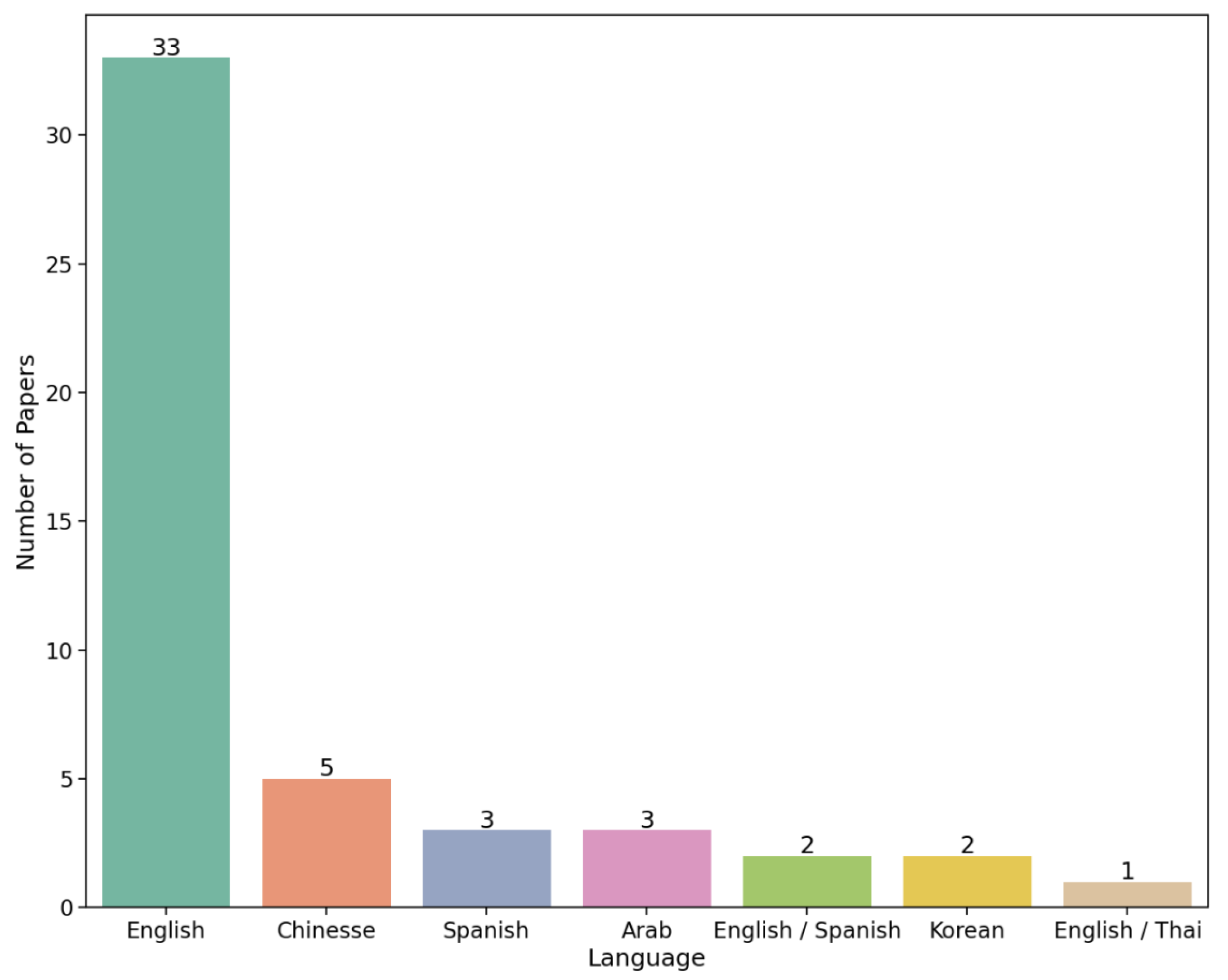

3.2. Study Characteristics

- LR (ML Classifier): Logistic Regression

- RF (ML Classifier): Random Forest

- NB (ML Classifier): Naïve Bayes

- GB (ML Classifier): Gradient Boosting

- DT (ML Classifier): Decision Tree

- SVM (ML Classifier): Support Vector Machine

- SVC (ML Classifier): Support Vector Classifier

- KNN (ML Classifier): K-Nearest Neighbor

- MNB (ML Classifier): Multinomial Naive Bayes

- SGD (ML Classifier): Stochastic Gradient Descent

- ANN (ML Classifier): Artificial Neural Network

- MLP (DL Classifier): Multilayer Perceptron

- CNN (DL Classifier): Convolutional Neural Network

- RNN (DL Classifier): Recurrent Neural Network

- GRU (DL Classifier): Gated Recurrent Unit

- LSTM (DL Classifier): Long Short-Term Memory

- BERT (DL Classifier): Bidirectional Encoder Representation from Transformers

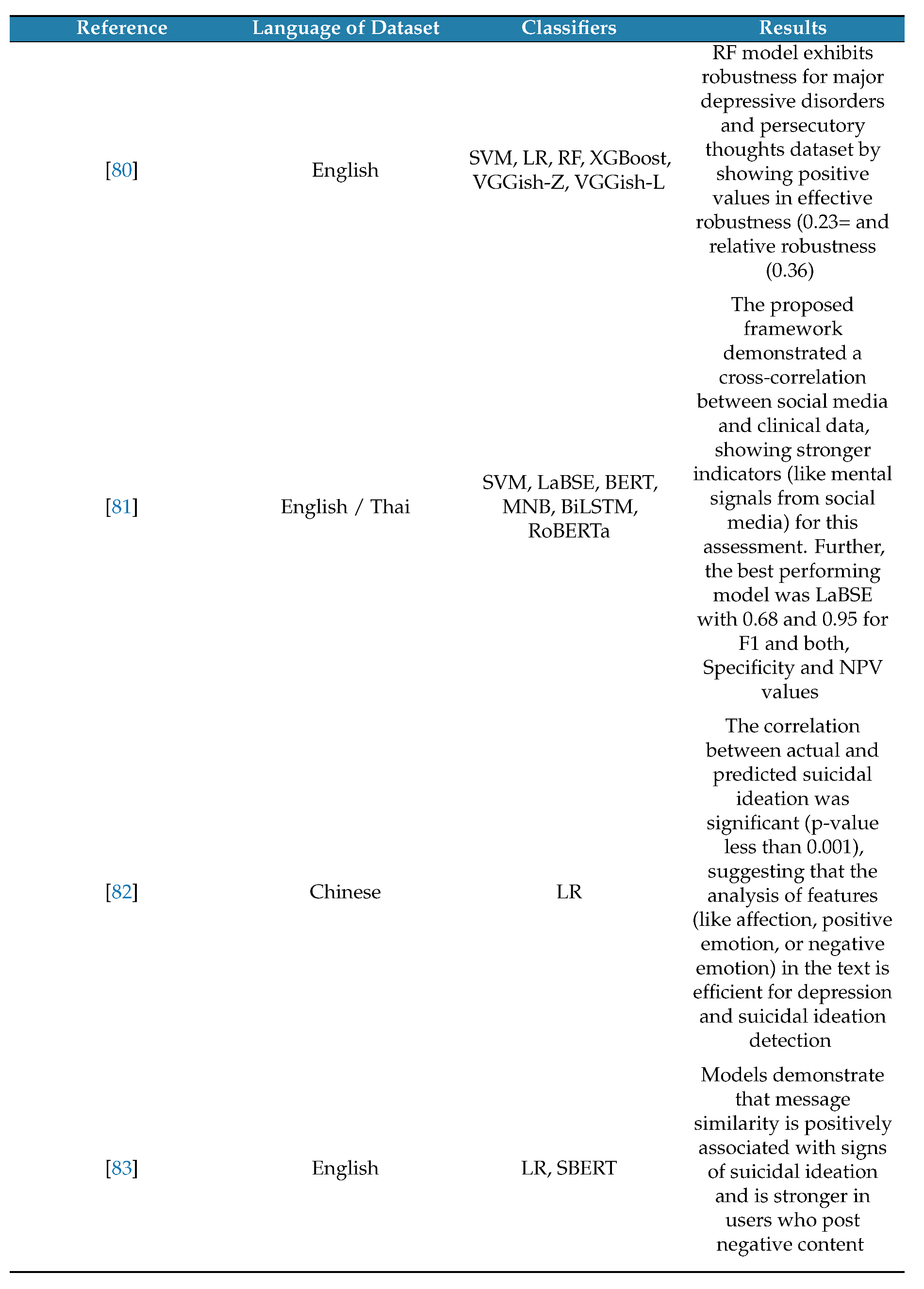

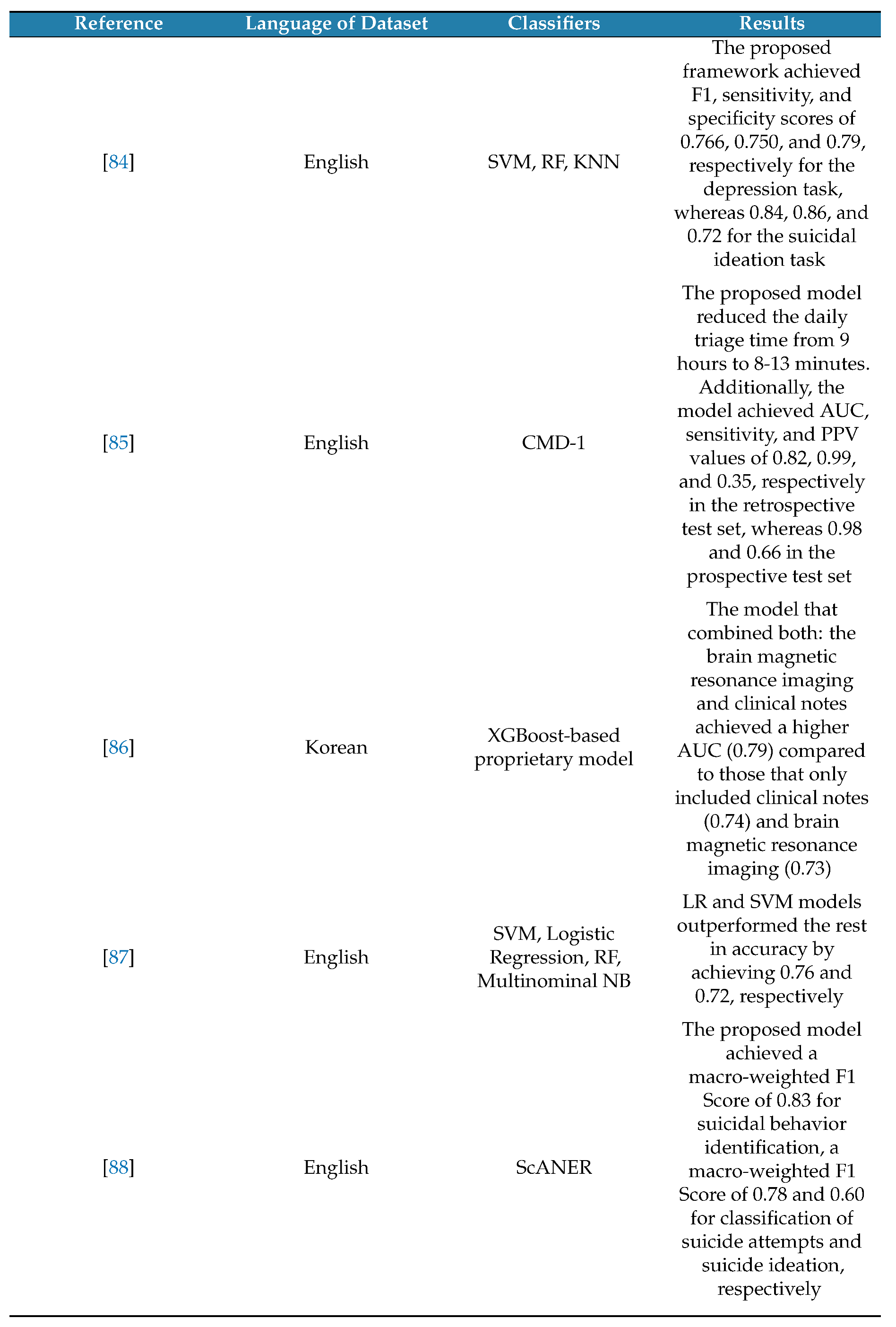

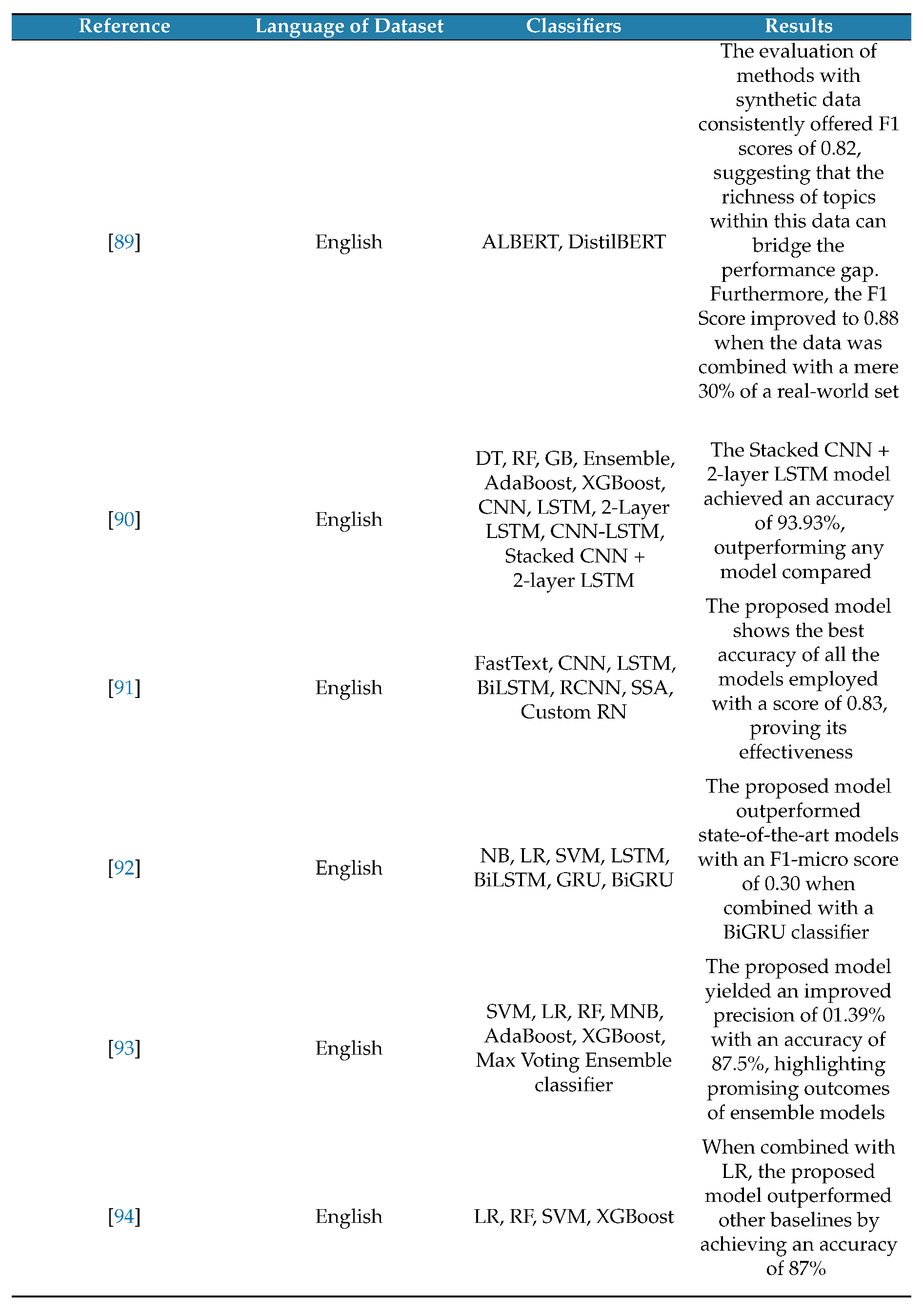

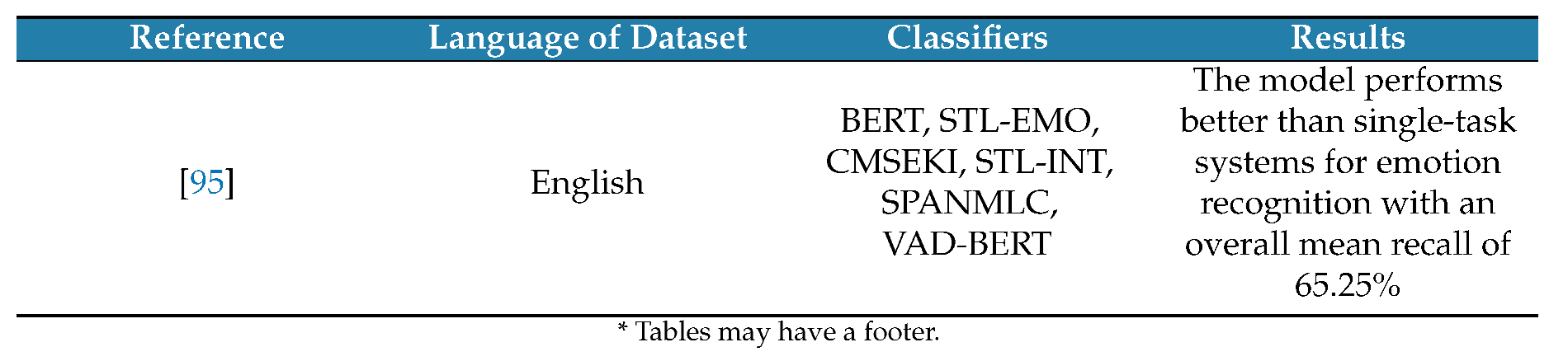

3.3. Discussion

3.4. Suicidal Ideation & Suicide

3.5. Depression & other Mental Disorders

3.6. Limitations

4. Conclusion

- Detecting implicit suicidal manifestations and ambiguous emotions in sentences.

- Improve the integration of user-profiles and linguistic features for social media data to improve suicide ideation detection.

- Expand the inclusion of parameters that add demographic context to data such as gender and location.

- Data from social media should include images, videos, and emoticons in its analysis to provide a complete assessment of potential suicidal risk.

- Explore language diversity beyond English in models, as well as cross-lingual frameworks.

- Address data sparsity and imbalance challenges.

- Validate results through large-scale research with larger datasets, ground-truth clinical data, and specialized vocabulary.

- Continue the exploration of the impact of risk factors in the detection of suicidal ideation automatically.

- Test models generalization for potential clinical detection applications.

- Continue exploring the performance of novel techniques and datasets from various social media sites for this task.

- Continue incorporating a timeline analysis in social media data to improve the identification of individual risk cases.

Author Contributions

References

- Turecki, G.; Brent, D.A.; Gunnell, D.; O’Connor, R.C.; Oquendo, M.A.; Pirkis, J.; Stanley, B.H. Suicide and suicide risk. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2019, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabilondo, A.; Muela, A.; Belarra, B.; De Sayas, A.; García, J.; López, P.; Reich, H.; Iruin, Á. Evaluación de BIZI, nuevo programa en línea en español para prevenir el suicidio desde la comunidad. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 2024, 48, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H. World Suicide Prevention Day 2023, 2023.

- for Suicide Prevention, T.I.A. Global Suicide Statistics, 2023.

- Organization, P.A.H. Suicide Mortality in the Americas – Regional Report 2015-2019; Pan American Health Organization, 2021. [CrossRef]

- SM Masango, S.R.; Motojesi, A. Suicide and suicide risk factors: A literature review. South African Family Practice 2008, 50, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pridmore, S.; Varbanov, S.; Aleksandrov, I.; Shahtahmasebi, S. Social Attitudes to Suicide and Suicide Rates. Open Journal of Social Sciences 2016, 04, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minayo, M.C.d.S.; Cavalcante, F.G.; Souza, E.R.d. Methodological proposal for studying suicide as a complex phenomenon. Cadernos de saude publica 2006, 22, 1587–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.K.; Patel, T.C.; Avenido, J.; Patel, M.; Jaleel, M.; Barker, N.C.; Khan, J.A.; All, S.; Jabeen, S. Suicide: current trends. Journal of the National Medical Association 2011, 103, 614–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Hernández, A.M.; Leenaars, A.A. Edwin S Shneidman y la suicidología moderna. Salud mental 2010, 33, 355–360. [Google Scholar]

- for Disease Control, C. ; Prevention. Facts about suicide, 2023.

- Leenaars, A.A. Suicide: A Multidimensional Malaise 1996. 26, 221–236. [CrossRef]

- Suicide, I.o.M.U.C.o.P.; of Adolescent, P. ; Adult.; Goldsmith, S.K.; Pellmar, T.C.; Kleinman, A.M.; Bunney, W.E., Society and Culture. In Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative; National Academies Press (US), 2002.

- Systematic review of risk factors for suicide and suicide attempt among psychiatric patients in Latin America and Caribbean.

- Mościcki, E.K. IDENTIFICATION OF SUICIDE RISK FACTORS USING EPIDEMIOLOGIC STUDIES. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 1997, 20, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmer, B.; Lee, S.; Duong, T.; Saadabadi, A. Suicid al ideation 2020.

- Kral, M.J.; Links, P.S.; Bergmans, Y. Suicide studies and the need for mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 2012, 6, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood-Williams, J. Studying suicide. Health & Place 1996, 2, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareen, J.; Isaak, C.; Katz, L.Y.; Bolton, J.; Enns, M.W.; Stein, M.B. Promising strategies for advancement in knowledge of suicide risk factors and prevention. American journal of preventive medicine 2014, 47, S257–S263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadon, N.B.; Calati, R.; Gonda, X. Evidence-based psychotherapeutic methods of prevention and intervention in suicidal behaviour. Neuropsychopharmacologia Hungarica: a Magyar Pszichofarmakologiai Egyesulet lapja= official journal of the Hungarian Association of Psychopharmacology 2022, 24, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Botega, N.J.; Barros, M.B.d.A.; Oliveira, H.B.d.; Dalgalarrondo, P.; Marín-León, L. Suicidal behavior in the community: prevalence and factors associated with suicidal ideation. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry 2005, 27, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-Patrick, L.; Crum, R.M.; Ford, D.E. Identifying suicidal ideation in general medical patients. Jama 1994, 272, 1757–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiKtaş Yerli, G. SUICIDE AS A SOCIOLOGICAL FACT AND ITS DIMENSION IN TURKEY 2023. p. 52. [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Kovacs, M.; Weissman, A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 1979, 47, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastler, H.M.; Khazem, L.R.; Ammendola, E.; Baker, J.C.; Bauder, C.R.; Tabares, J.; Bryan, A.O.; Szeto, E.; Bryan, C.J. An empirical investigation of the distinction between passive and active ideation: Understanding the latent structure of suicidal thought content. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 2023, 53, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, K.; Boduszek, D.; O’Connor, R.C. Differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators using the Integrated Motivational–Volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Journal of affective disorders 2015, 186, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, E.D.; Saffer, B.Y.; Bryan, C.J. Ideation-to-action theories of suicide: a conceptual and empirical update. Current opinion in psychology 2018, 22, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleiman, E.M.; Nock, M.K. Real-time assessment of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Current Opinion in Psychology 2018, 22, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchionatti, L.E.; Magalhães, P.V.d.S. On suicidal ideation: the need for inductive methodologies to advance the field. Trends in psychiatry and psychotherapy 2023, 45, e20230655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, K.; Brown, G.K.; Stanley, B.; Brent, D.A.; Yershova, K.V.; Oquendo, M.A.; Currier, G.W.; Melvin, G.A.; Greenhill, L.; Shen, S.; et al. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. American journal of psychiatry 2011, 168, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrill, D.R.; Rodriguez-Seijas, C.; Zimmerman, M. Assessing suicidal ideation using a brief self-report measure. Psychiatry Research 2021, 297, 113737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Spijker, B.A.; Batterham, P.J.; Calear, A.L.; Farrer, L.; Christensen, H.; Reynolds, J.; Kerkhof, A.J. The Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scale (SIDAS): Community-based validation study of a new scale for the measurement of suicidal ideation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 2014, 44, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giddens, J.M.; Sheehan, K.H.; Sheehan, D.V. The Columbia-suicide severity rating scale (C–SSRS): has the “gold standard” become a liability? Innovations in clinical neuroscience 2014, 11, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M.; Ramar, D.; Vijayan, R.; Gupta, N. Artificial intelligence tools for suicide prevention in adolescents and young adults. Adolescent Psychiatry 2022, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseka, T.M.; Bhat, V.; Kennedy, S.H. The utility of artificial intelligence in suicide risk prediction and the management of suicidal behaviors. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2019, 53, 954–964. [Google Scholar]

- Halsband, A.; Heinrichs, B. AI, suicide prevention and the limits of beneficence. Philosophy & Technology 2022, 35, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Dhelim, S.; Chen, L.; Ning, H.; Nugent, C. Artificial intelligence for suicide assessment using Audiovisual Cues: a review. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 5591–5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Pan, S.; Li, X.; Cambria, E.; Long, G.; Huang, Z. Suicidal ideation detection: A review of machine learning methods and applications. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 2020, 8, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.A. Searching for significance in unstructured data: Text mining with Leximancer. European Educational Research Journal 2014, 13, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, R.; Islam, N.; Islam, M.; Ahsan, M.M. A Comparative Analysis on Suicidal Ideation Detection Using NLP, Machine, and Deep Learning. Technologies 2022, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, P.D.; Vicnesh, J.; Lih, O.S.; Palmer, E.E.; Yamakawa, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Acharya, U.R. Artificial intelligence assisted tools for the detection of anxiety and depression leading to suicidal ideation in adolescents: a review. Cognitive Neurodynamics 2022, pp. 1–22.

- Arowosegbe, A.; Oyelade, T. Application of Natural Language Processing (NLP) in Detecting and Preventing Suicide Ideation: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, G. The World’s 10 Most Influential Languages. AATF National Bulletin 2008, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Holm, M.E.; Østergaard, L.D.; Aamund, K.; Jørgensen, K.; Midtgaard, J.; Vinberg, M.; Nordentoft, M. What methods are used in research of firsthand experiences with online self-harming and suicidal behavior? A scoping review. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 2024, 78, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity 2022, 56, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, W.G.; Yu, W. A Survey of Deep Learning: Platforms, Applications and Emerging Research Trends. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 24411–24432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, M.S.; Suryadi, J.J.; Marchellino, K.; Nabiilah, G.Z.; Rojali. A Comparative Analysis of Decision Tree and Support Vector Machine on Suicide Ideation Detection. Procedia Computer Science 2023, 227, 518–523. [CrossRef]

- Rentz, D.M.; Heckler, W.F.; Barbosa, J.L.V. A computational model for assisting individuals with suicidal ideation based on context histories. Universal Access in the Information Society 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K, S.; M, E.; V, A. A Hybrid Attention Based Deep Learning System for Suicidal Ideation Detection in Social Media 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chadha, A.; Kaushik, B. A Hybrid Deep Learning Model Using Grid Search and Cross-Validation for Effective Classification and Prediction of Suicidal Ideation from Social Network Data. New Generation Computing 2022, 40, 889–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiñazú, M.F.; González, M.; Ruiz, R.B.; Hernández, V.; Diez, S.B.; Velásquez, J.D. A novel depression risk prediction model based on data fusion from Chilean National Health Surveys to diagnose risk depression among patients with mood disorders. Information Fusion 2023, 100, 101960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassine, M.A.; Abdellatif, S.; Ben Yahia, S. A novel imbalanced data classification approach for suicidal ideation detection on social media. Computing 2022, 104, 741–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qorich, M.; El Ouazzani, R. Advanced deep learning and large language models for suicide ideation detection on social media. Progress in Artificial Intelligence 2024, 13, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renjith, S.; Abraham, A.; Jyothi, S.B.; Chandran, L.; Thomson, J. An ensemble deep learning technique for detecting suicidal ideation from posts in social media platforms. Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences 2022, 34, 9564–9575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Dasgupta, S.; Anam, A.; Saha, R.; Nath, S.; Dutta, S. An Investigation of Suicidal Ideation from Social Media Using Machine Learning Approach. Baghdad Science Journal 2023, 20, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, N.A.; Malki, A.; Magdy Balaha, H.; AbdulAzeem, Y.; Badawy, M.; Elhosseini, M. An optimized deep learning approach for suicide detection through Arabic tweets. PeerJ Computer Science 2022, 8, e1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.; Miri Rekavandi, A.; Rooprai, D.; Dwivedi, G.; Sanfilippo, F.M.; Boussaid, F.; Bennamoun, M. Analysis and evaluation of explainable artificial intelligence on suicide risk assessment. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 6163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassib, M.; Hossam, N.; Sameh, J.; Torki, M. AraDepSu: Detecting Depression and Suicidal Ideation in Arabic Tweets Using Transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the The Seventh Arabic Natural Language Processing Workshop (WANLP), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Hybrid), 2022; p. 302–311. [CrossRef]

- Acuña Caicedo, R.W.; Gómez Soriano, J.M.; Melgar Sasieta, H.A. Assessment of supervised classifiers for the task of detecting messages with suicidal ideation. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Noguez, L.R.; Tovar-Arriaga, S.; Paredes-García, W.J.; Ramos-Arreguín, J.M.; Aceves-Fernandez, M.A. Automatic classification of depressive users on Twitter including temporal analysis. Network Modeling Analysis in Health Informatics and Bioinformatics 2023, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Schoene, A.M.; Ananiadou, S. Automatic identification of suicide notes with a transformer-based deep learning model. Internet Interventions 2021, 25, 100422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarsam, S.M.; Al-Samarraie, H.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Mon, C.S.; Shibghatullah, A.S. Characterizing Suicide Ideation by Using Mental Disorder Features on Microblogs: A Machine Learning Perspective. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Park, S.; Kang, J.; Choi, D.; Han, J. Cross-Lingual Suicidal-Oriented Word Embedding toward Suicide Prevention. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, Online; 2020; pp. 2208–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapelberg, N.J.; Randall, M.; Sveticic, J.; Fugelli, P.; Dave, H.; Turner, K. Data mining of hospital suicidal and self-harm presentation records using a tailored evolutionary algorithm. Machine Learning with Applications 2021, 3, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, J.; An, Z.; Cheng, W.; Hu, B. Deep Hierarchical Ensemble Model for Suicide Detection on Imbalanced Social Media Data. Entropy 2022, 24, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Cheng, W.; Zhou, J.; An, Z.; Hu, B. Deep learning model with multi-feature fusion and label association for suicide detection. Multimedia Systems 2023, 29, 2193–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhyani, T.H.H.; Alsubari, S.N.; Alshebami, A.S.; Alkahtani, H.; Ahmed, Z.A.T. Detecting and Analyzing Suicidal Ideation on Social Media Using Deep Learning and Machine Learning Models. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 12635–12635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulsalam, A.; Alhothali, A.; Al-Ghamdi, S. Detecting Suicidality in Arabic Tweets Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabani, S.T.; Ud Din Khanday, A.M.; Khan, Q.R.; Hajam, U.A.; Imran, A.S.; Kastrati, Z. Detecting suicidality on social media: Machine learning at rescue. Egyptian Informatics Journal 2023, 24, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabra, J.; Martínez-Martínez, A.B.; Aragón, I.; López-Del-Hoyo, Y.; Pérez-Yus, C.; Oliván, B. Detecting Suicide Risk Through Twitter 2020.

- Pool-Cen, J.; Carlos-Martínez, H.; Hernández-Chan, G.; Sánchez-Siordia, O. Detection of Depression-Related Tweets in Mexico Using Crosslingual Schemes and Knowledge Distillation. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Cifuentes, D.; Freire, A.; Baeza-Yates, R.; Puntí, J.; Medina-Bravo, P.; Velazquez, D.A.; Gonfaus, J.M.; Gonzàlez, J. Detection of Suicidal Ideation on Social Media: Multimodal, Relational, and Behavioral Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2020, 22, e17758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeriano, K.; Condori-Larico, A.; Sulla-Torres, J. Detection of Suicidal Intent in Spanish Language Social Networks using Machine Learning. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, M.M.; Lin, H.; Xu, B.; Yang, L. Detection of Suicide Ideation in Social Media Forums Using Deep Learning. Algorithms 2019, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodati, D.; Tene, R. Emotion mining for early suicidal threat detection on both social media and suicide notes using context dynamic masking-based transformer with deep learning. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Cifuentes, D.; Largeron, C.; Tissier, J.; Baeza-Yates, R.; Freire, A. Enhanced Word Embedding Variations for the Detection of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Issues on Social Media Writings. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 130449–130471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Yi, S.; Chen, J.; Chan, K.Y.; Chan, J.W.Y.; Chan, N.Y.; Li, S.X.; Wing, Y.K.; Li, T.M.H. Exploring the Role of First-Person Singular Pronouns in Detecting Suicidal Ideation: A Machine Learning Analysis of Clinical Transcripts. Behavioral Sciences 2024, 14, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, F.; Jiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, W. Identifying Suicidal Ideation Among Chinese Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: Evidence from a Real-World Hospital-Based Study in China. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 2020, Volume 16, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, A.; Nepal, S.K.; Wang, W.; Nemesure, M.; Heinz, M.; Price, G.; Lekkas, D.; Collins, A.C.; Griffin, T.; Buck, B.; et al. Investigating Generalizability of Speech-based Suicidal Ideation Detection Using Mobile Phones. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies 2023, 7, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noraset, T.; Chatrinan, K.; Tawichsri, T.; Thaipisutikul, T.; Tuarob, S. Language-agnostic deep learning framework for automatic monitoring of population-level mental health from social networks. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2022, 133, 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, W.; Wang, X.; Zhou, W.; Hang, B.; Guo, L. Linguistic Analysis for Identifying Depression and Subsequent Suicidal Ideation on Weibo: Machine Learning Approaches. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malko, A.; Duenser, A.; Kangas, M.; Mollá-Aliod, D.; Paris, C. Message similarity as a proxy to repetitive thinking: Associations with non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal ideation on social media. Computers in Human Behavior Reports 2023, 11, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogrucu, A.; Perucic, A.; Isaro, A.; Ball, D.; Toto, E.; Rundensteiner, E.A.; Agu, E.; Davis-Martin, R.; Boudreaux, E. Moodable: On feasibility of instantaneous depression assessment using machine learning on voice samples with retrospectively harvested smartphone and social media data. Smart Health 2020, 17, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, A.; López, I.; Mar, R.A.G.; Heist, T.; McClintock, T.; Caoili, K.; Grace, M.; Rubashkin, M.; Boggs, M.N.; Chen, J.H.; et al. Natural language processing system for rapid detection and intervention of mental health crisis chat messages. npj Digital Medicine 2023, 6, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Byeon, G.; Kim, N.; Son, S.J.; Park, R.W.; Park, B. Neuroimaging and natural language processing-based classification of suicidal thoughts in major depressive disorder. Translational Psychiatry 2024, 14, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, A.; Gadwe, A.; Poddar, D.; Satavalekar, S.; Sahu, S. Performance Evaluation of Different Machine Learning Techniques using Twitter Data for Identification of Suicidal Intent. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Electronics and Sustainable Communication Systems (ICESC), Coimbatore, India; 2020; pp. 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, B.P.S.; Kovaly, S.; Yu, H.; Pigeon, W. ScAN: Suicide Attempt and Ideation Events Dataset. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Seattle, United States, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ghanadian, H.; Nejadgholi, I.; Osman, H.A. Socially Aware Synthetic Data Generation for Suicidal Ideation Detection Using Large Language Models. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 14350–14363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyamvada, B.; Singhal, S.; Nayyar, A.; Jain, R.; Goel, P.; Rani, M.; Srivastava, M. Stacked CNN - LSTM approach for prediction of suicidal ideation on social media. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2023, 82, 27883–27904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Li, X.; Huang, Z.; Cambria, E. Suicidal ideation and mental disorder detection with attentive relation networks. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, 34, 10309–10319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J, A.K.; Trueman, T.E.; A K, A. Suicidal risk identification in social media. Procedia Computer Science 2021, 189, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.; Digalwar, M. Suicidal Thought Detection using Max Voting Ensemble Technique. Procedia Computer Science 2024, 235, 2587–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, M.; Kumar, P.; Samanta, P.; Sarkar, D. Suicide ideation detection from online social media: A multi-modal feature based technique. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights 2022, 2, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Ekbal, A.; Bhattacharyya, P. VAD-assisted multitask transformer framework for emotion recognition and intensity prediction on suicide notes. Information Processing & Management 2023, 60, 103234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool-Cen, J.; Carlos-Martínez, H.; Hernández-Chan, G.; Sánchez-Siordia, O. Detection of Depression-Related Tweets in Mexico Using Crosslingual Schemes and Knowledge Distillation. In Proceedings of the Healthcare. MDPI, 2023, Vol. 11, p. 1057.

- Valeriano, K.; Condori-Larico, A.; Sulla-Torres, J. Detection of suicidal intent in Spanish language social networks using machine learning. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schools, M.L. , 2023.

- Rajesh Kumar, E.; Rama Rao, K.; Nayak, S.R.; Chandra, R. Suicidal ideation prediction in twitter data using machine learning techniques. Journal of Interdisciplinary Mathematics 2020, 23, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lones, M.A. How to avoid machine learning pitfalls: a guide for academic researchers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.02497 2021.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).