Submitted:

17 July 2023

Posted:

18 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgment

References

- World Health Organization. 2018. [2018-04-23]. Depression: Key Facts. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression.

- Kessler, R.C.; Chiu, W.T.; Demler, O.; Walters, E.E. Prevalence, Severity, and Comorbidity of 12-Month DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. [2020-10-10]. Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/254610.

- Rehm, J.; Shield, K.D. Global Burden of Disease and the Impact of Mental and Addictive Disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoevers RA, Smit F, et al. Prevention of late-life depression in primary care: do we know where to begin? The American journal of psychiatry 2006, 163(9):1611-1621.

- Touloumis, C. The burden and the challenge of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatriki 2021, 32, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sik, D. From mental disorders to social suffering: Making sense of depression for critical theories. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2018, 22, 477–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, L.J.; Griffiths, K.M.; Jorm, A.F.; Christensen, H. Stigma about Depression and its Impact on Help-Seeking Intentions. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 2006, 40, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giumetti, G.W.; Kowalski, R.M. Cyberbullying via social media and well-being. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 45, 101314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, H.C.; Scott, H. #Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. J. Adolesc. 2016, 51, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oexle, N.; Ajdacic-Gross, V.; Kilian, R.; Müller, M.; Rodgers, S.; Xu, Z.; Rössler, W.; Rüsch, N. Mental illness stigma, secrecy and suicidal ideation. Epidemiology Psychiatr. Sci. 2017, 26, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO suicide worldwide in 2019 report. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506021.

- Värnik, P. Suicide in the World. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2012, 9, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raue, P.J.; Ghesquiere, A.R.; Bruce, M.L. Suicide Risk in Primary Care: Identification and Management in Older Adults. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, E.D.; May, A.M. Differentiating Suicide Attempters from Suicide Ideators: A Critical Frontier for Suicidology Research. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2014, 44, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, S. C. (2011). The practical art of suicide assessment: A guide for mental health professionals and substance abuse counselors. Hoboken, NJ: Mental Health Presses.

- Nock, M.K.; Borges, G.; Bromet, E.J.; Cha, C.B.; Kessler, R.C.; Lee, S. Suicide and Suicidal Behavior. Epidemiologic Rev. 2008, 30, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrijvers, D.L.; Bollen, J.; Sabbe, B.G. The gender paradox in suicidal behavior and its impact on the suicidal process. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 138, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscopo K., Lipari R, Suicidal Thoughts and Behavior among Adults: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, NSDUH Data Revew from. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/.

- Mann, J.J.; Michel, C.A.; Auerbach, R.P. Improving Suicide Prevention Through Evidence-Based Strategies: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Psychiatry 2021, 178, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappell, P.B.; Stewart, M.; Alphs, L.; DiCesare, F.; DuBrava, S.; Harkavy-Friedman, J.; Lim, P.; Ratcliffe, S.; Silverman, M.M.; Targum, S.D.; et al. Assessment of Suicidal Ideation and Behavior. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2017, 78, e638–e647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R. I. (2011). Improving suicide risk assessment. Psychiatric Times, 28(11), 16–21.

- Chan, M.K.Y.; Bhatti, H.; Meader, N.; Stockton, S.; Evans, J.; O'Connor, R.C.; Kapur, N.; Kendall, T. Predicting suicide following self-harm: systematic review of risk factors and risk scales. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 209, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorny, A.D. Prediction of Suicide in Psychiatric Patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1983, 40, 249–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawgood J and De Leo D., Suicide Prediction – A Shift in Paradigm Is Needed Crisis 2016 37:4, 251-255.

- Nestadt, P.S.; Triplett, P.; Mojtabai, R.; Berman, A.L. Universal screening may not prevent suicide. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2020, 63, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenault-Lapierre, G.; Kim, C.; Turecki, G. Psychiatric diagnoses in 3275 suicides: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2004, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Beurs, D.; Have, M.T.; Cuijpers, P.; de Graaf, R. The longitudinal association between lifetime mental disorders and first onset or recurrent suicide ideation. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.; Geddes, J.; Deeks, J.; Goldacre, M.; Hawton, K. Suicide in psychiatric hospital in-patients. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 176, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isometsä, E. Suicidal Behaviour in Mood Disorders—Who, When, and Why? Can. J. Psychiatry 2014, 59, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratkowska, K. A., Grad, O., et al, (2013). Traumatic bereavement for the therapist: The aftermath of a patient suicide. In D. De LeoA. CimitanK. DyregrovO. GradK. AndriessenEds., Bereavement after traumatic death: Helping the survivors (pp.105–114). Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe.

- Draper, B. Isn’t it a bit risky to dismiss suicide risk assessment? Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 2012, 46, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Hoti, K.; Hughes, J.D.; Emmerton, L.M. Dr Google and the Consumer: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Navigational Needs and Online Health Information-Seeking Behaviors of Consumers With Chronic Health Conditions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, E.; Czerwinski, F.; Reifegerste, D. Gender-Specific Determinants and Patterns of Online Health Information Seeking: Results From a Representative German Health Survey. J. Med Internet Res. 2017, 19, e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, G.M.; O’donovan, A.; Epel, E.S.; Kemeny, M.E. Black sheep get the blues: A psychobiological model of social rejection and depression. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 35, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, R.; Sik, D.; Máté, F. Machine Learning of Concepts Hard Even for Humans: The Case of Online Depression Forums. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Tan, Y. Feeling Blue? Go Online: An Empirical Study of Social Support Among Patients. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 690–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukka, E.; Rantakokko, P.; Suhonen, M. Consumer-led health-related online sources and their impact on consumers: An integrative review of the literature. Heal. Informatics J. 2017, 25, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiritchenko, S.; Zhu, X.; Mohammad, S.M. Sentiment analysis of short informal texts. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2014, 50, 723–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, M.M.; Lin, H.; Xu, B.; Yang, L. Detection of Suicide Ideation in Social Media Forums Using Deep Learning. Algorithms 2019, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeskuatov, E.; Chua, S.-L.; Foo, L.K. Leveraging Reddit for Suicidal Ideation Detection: A Review of Machine Learning and Natural Language Processing Techniques. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 10347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birjali, M.; Beni-Hssane, A.; Erritali, M. Machine Learning and Semantic Sentiment Analysis based Algorithms for Suicide Sentiment Prediction in Social Networks. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 113, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancellor, S.; De Choudhury, M. Methods in predictive techniques for mental health status on social media: a critical review. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beriwal, M.; Agrawal, S. Techniques for Suicidal Ideation Prediction: A Qualitative Systematic Review. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on INnovations in Intelligent SysTems and Applications (INISTA), Kocaeli, Turkey; 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A.; Nikolitch, K.; McGinn, R.; Jinah, S.; Klement, W.; Kaminsky, Z.A. A machine learning approach predicts future risk to suicidal ideation from social media data. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, S.R.; Giraud-Carrier, C.; West, J.; Barnes, M.D.; Hanson, C.L. Validating Machine Learning Algorithms for Twitter Data Against Established Measures of Suicidality. JMIR Ment. Heal. 2016, 3, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachmar M., Wittenborn A., et al #MyDepressionLooksLike: Examining Public Discourse About Depression on Twitter, JMIR Ment Health. 2017 Oct-Dec; 4(4): e43. [CrossRef]

- Naranowicz, M.; Jankowiak, K.; Kakuba, P.; Bromberek-Dyzman, K.; Thierry, G. In a Bilingual Mood: Mood Affects Lexico-Semantic Processing Differently in Native and Non-Native Languages. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, T.; Fishbain, B.; Markus, A.; Richter-Levin, G.; Okon-Singer, H. Using machine learning-based analysis for behavioral differentiation between anxiety and depression. Sci. Rep. 2021, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.K.; Islam, M.; Kabir, A.N.B.; Haque, A.; Rhaman, K. Detection of Depression Severity from Bengali Social Media Posts for Mental Health: A Study Using Natural Language Processing Techniques (Preprint). JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e36118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladağ, A.E.; Muderrisoglu, S.; Akbas, N.B.; Zahmacioglu, O.; O Bingol, H. Detecting Suicidal Ideation on Forums: Proof-of-Concept Study. J. Med Internet Res. 2018, 20, e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, A, Poteet RS (Editors), Natural language processing and text mining. London: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Dhar, A.; Mukherjee, H.; Dash, N.S.; Roy, K. Text categorization: past and present. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 54, 3007–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppersmith, G.; Ngo, K.; Leary, R.; Wood, A. Exploratory analysis of social media prior to a suicide attempt. In Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Clinical Psychology, San Diego, CA, USA, 16 June 2016; pp. 106–117. [Google Scholar]

- Salton, G.; Wong, A.; Yang, C.S. A vector space model for automatic indexing. Commun. ACM 1975, 18, 613–620. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.cs. waikato.ac.nz/ml/weka/.

- Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romania.

- Available online: https://legmed.ro/doc/dds2018.pdf.

- Merlini D., Rossini M., 2021 Text categorization with WEKA, a survey., Machine Learning with Applications, 4, p.100033.

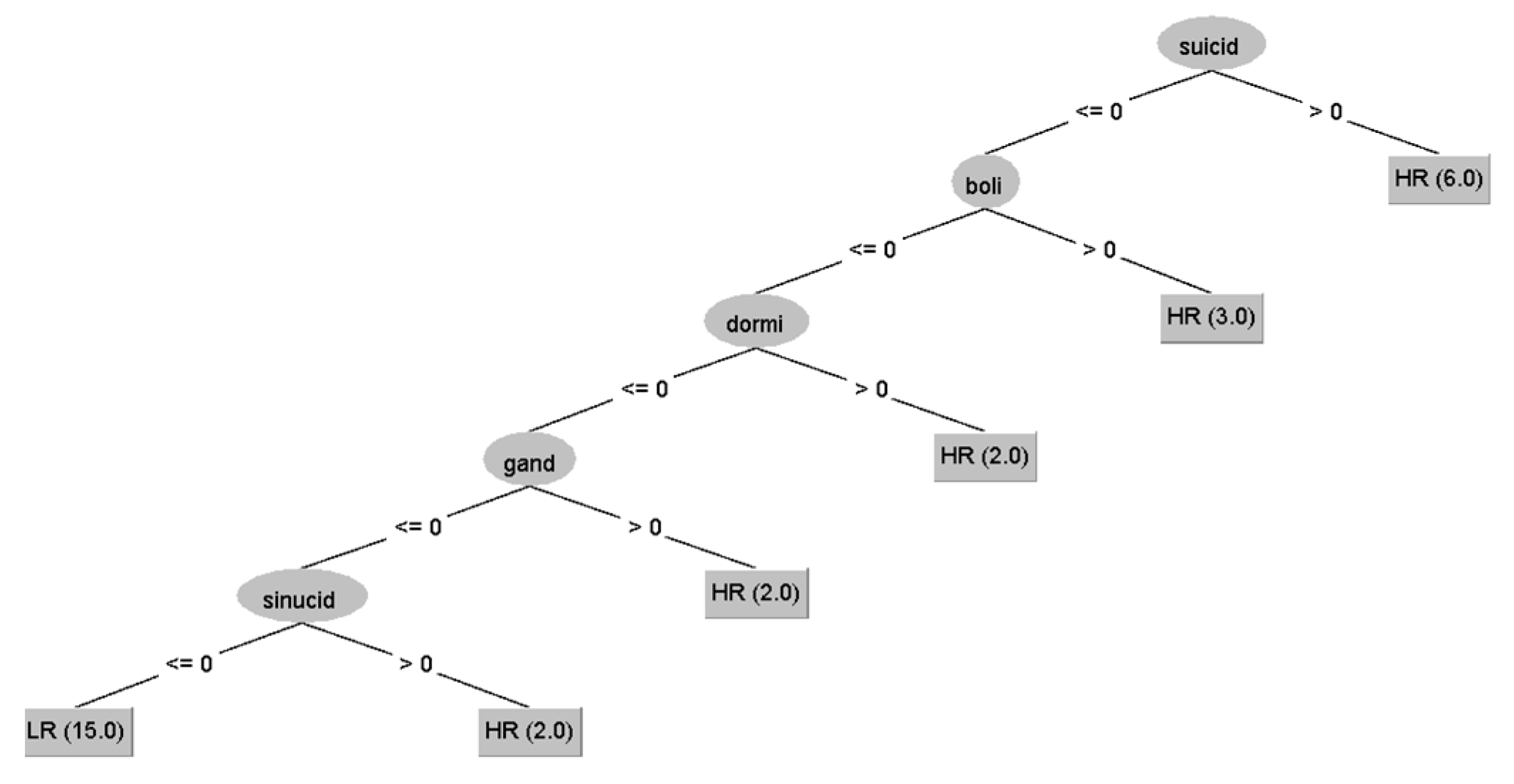

- Loh, W.-Y. Fifty Years of Classification and Regression Trees. Int. Stat. Rev. 2014, 82, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, S. C. (2011). The practical art of suicide assessment: A guide for mental health professionals and substance abuse counselors. Hoboken, NJ: Mental Health Presses.

- Ratkowska, K. A., Grad, O., et al, (2013). Traumatic bereavement for the therapist: The aftermath of a patient suicide. In D. De LeoA. CimitanK. DyregrovO. GradK. AndriessenEds., Bereavement after traumatic death: Helping the survivors (pp.105–114). Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe.

- Séguin, M.; Bordeleau, V.; Drouin, M.-S.; Castelli-Dransart, D.A.; Giasson, F. Professionals' Reactions Following a Patient's Suicide: Review and Future Investigation. Arch. Suicide Res. 2014, 18, 340–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Training Dataset 30 cases | Testing Dataset 125 cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selected SI+ | Selected SI- | All presumed SI- | ||

| NR | 15 | 15 | 125 | |

| Sex | 6m/9f | 6m/9f | 51 m | 74 f |

| Age (yrs.) | 33.4±6 | 35.6±8 | 29.25±10.1 | 31.01±10.6 |

| Depression duration (yrs.) | 2.15±1.4 | 2.41±1.7 | 3.04±3.21 | 4.37±6.1 |

| Words/excerpt | 161.1±93.8(*) | 149.9±106.2 | 301.69±180(*) | |

| Testing dataset (125 subjects) | Predicted SI+ | Predicted SI- |

|---|---|---|

| NR | 32 | 91 |

| Sex | 21m/11f | 30m/61f |

| Age (yrs.) | 34.1±10.2(*) | 30.2±10.2(*) |

| Depression duration (yrs.) | 3.54±3.4 | 4.0±5.52 |

| Words/excerpt | 221.4±157.25(**) | 329.9±179.7(**) |

| Predicted SI+ | Predicted SI- | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | F | M | All | F | M | |

| Number | 32 | 11 | 21 | 91 | 63 | 28 |

| Age | 34.1±10.2(*) | 29.2±8.4 | 36.7±10.3(**) | 30.0±10.3(*) | 31.4±10.89 | 27.5±8.23(**) |

|

Disease duration |

3.5±3.4 | 3.1±2.4 | 3.8±3.84 | 4.0±5.52 | 4.5±6.42 | 2.6±2.6 |

|

General Responses |

3.75±1.79(&) | 4.8±2.89 | 3.4±1.4 | 3.1±1.24(&) | 3.2±1.4 | 3.0±1.0 |

|

Medical Responses |

1±0.8($) | 1.1±1.04 | 1±0.9 | 2.1±1.1($) | 2.1±1.2 | 2.1±1.0 |

| Words/excerpt | 221.5± 157.25(#) |

226.4± 122.6 |

218.9± 175.5 |

329.9± 179.8(#) |

337.5± 189.1 |

313.2± 158.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).