Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

14 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

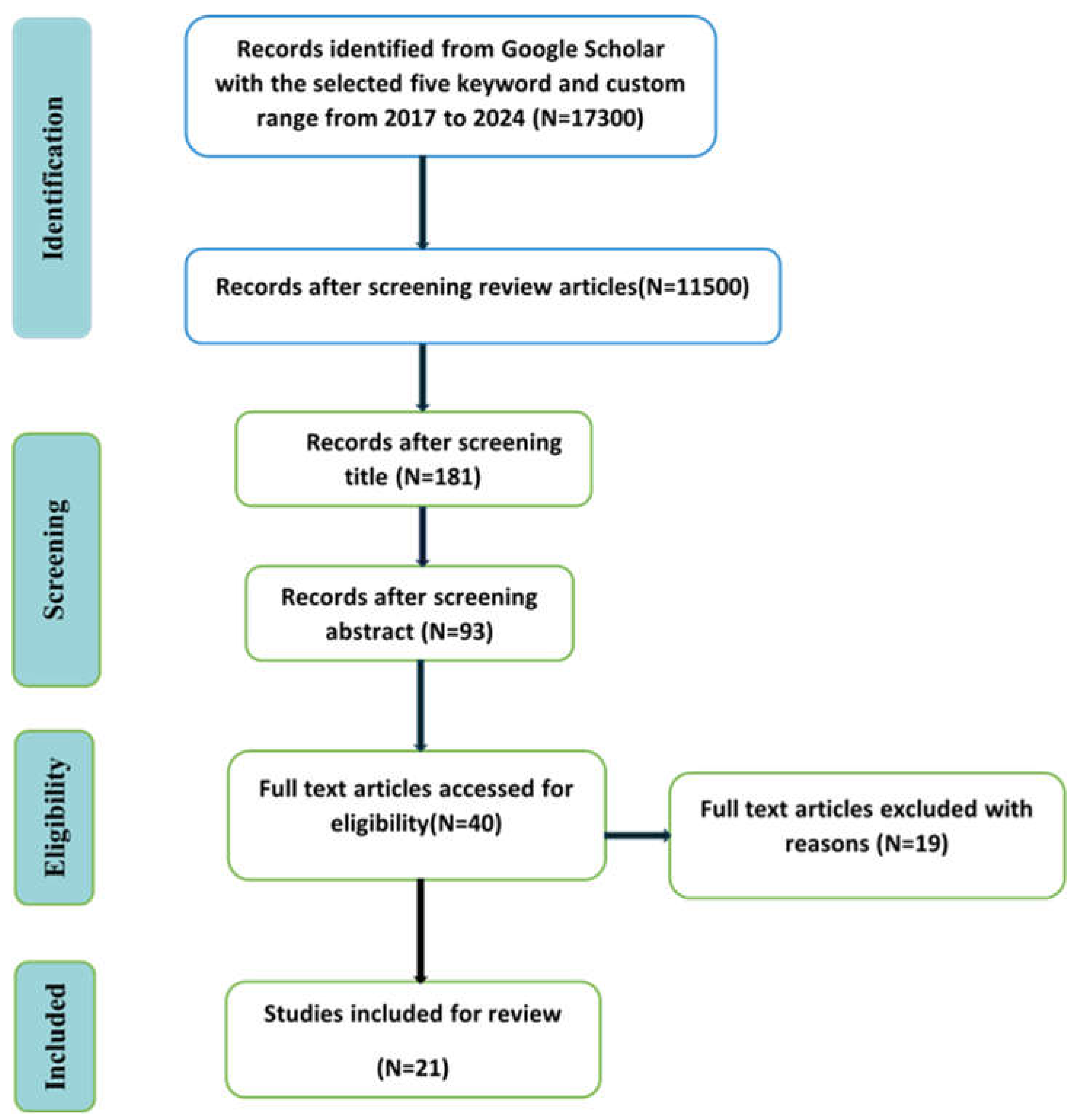

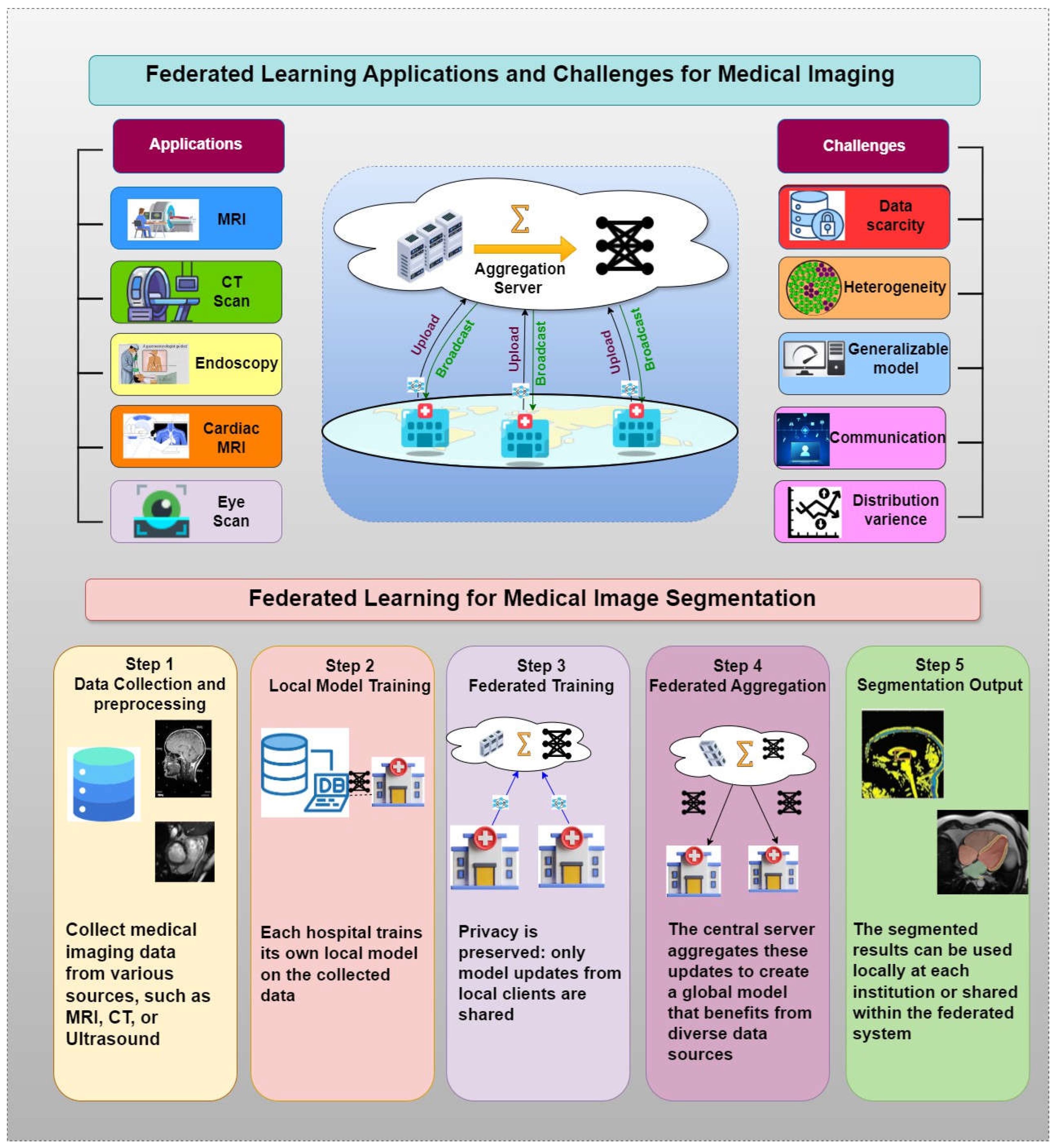

The possibility of medical image segmentation within the domain of a federated learning, Federated Learning (FL) may transform the situation and help solve the critical challenges that exist in common centralized machine learning models. While effective, traditional models are limited by issues like the need of huge surveys, high costs in data assignment, high privacy concerns over sensible wellbeing data. Since improvements in the medical imaging field continue, the adoption of FL is a strategic response to such limitations and can be introduced as a collaborative privacy preserving framework for model training. This was a systematic exploration of the literature from 2017 to 2024 where the Google Scholar literature has been explored for studies indexed with the keywords 'federated learning,' 'medical image segmentation,' and 'privacy preservation.' Specifically, this review did not consider studies that did not directly discuss FL concepts. Twenty-one publications were carefully selected from out of thousands of publications because they are relevant and contribute to the area of treatment. Specifically, seven studies directly approached the extent of medical image segmentation using FL and address the technological and the practical challenges. The remaining fourteen studies were foundational in that they further elaborated on the architectural and procedural elements of FL frameworks that are essential for collaborative and secure medical image analysis. A review of the selected studies is presented in detail in the review in terms of the effectiveness of FL in improving medical image segmentation while protecting patient privacy. It makes a powerful evaluation of the strengths and weakness of present FL model, the versatility of data sets, the diversity of the imaging modalities addressed, and scalability of these models across various clinical conditions. Such synthesis of this literature underscores the fact that FL can revolutionize medical diagnostics with opportunity to produce more robust, scalable, and privacy friendly models.

Keywords:

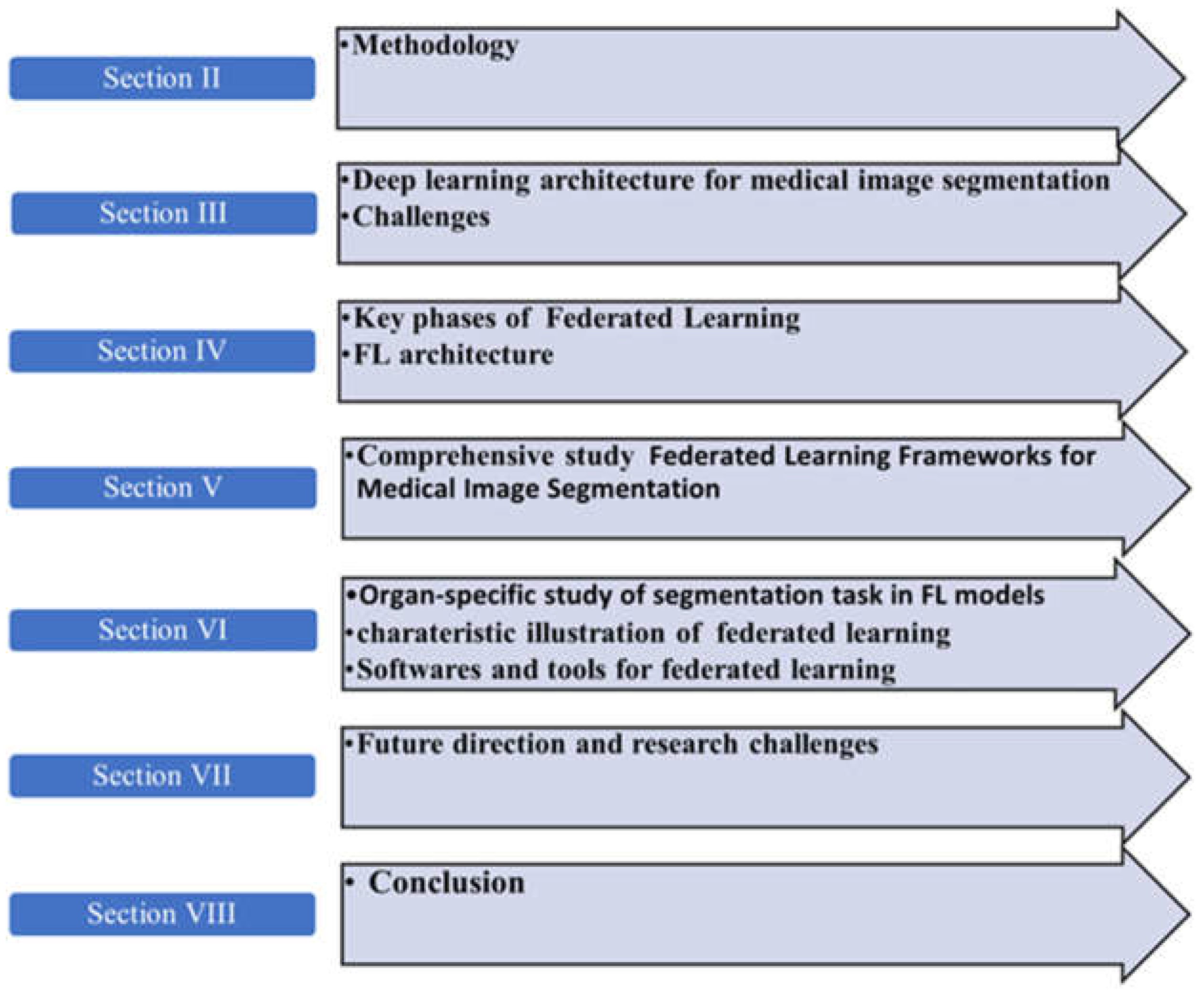

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Surveys

1.1.1. Distinct Coverage

1.1.2. Tools and Software

1.1.3. Future Direction and Research Challenges

- Literature Search and Refinement: We initiate our review with a meticulous search through Google Scholar, focusing exclusively on studies related to medical imaging modalities like MRI and CT scans. This targeted approach helps refine the scope of our review to include only the most relevant studies.

- Understanding the Shift to Federated Learning: We trace the evolution from traditional deep learning approaches in medical image segmentation to the adoption of federated learning, emphasizing the benefits of enhanced privacy and efficiency.

- Comprehensive Review of Federated Learning: Our analysis goes in-depth into the architectural frameworks of FL, discussing recent advancements and the technical challenges that arise with these new methods.

2. Methodology

2.1. Searching Method

2.2. Database for Searching

2.3. Keywords for Search

2.4. Eligibility Criterion

3. Fundamentals of Medical Image Segmentation

- Small Sample Size Problem: Deep learning models require large, annotated datasets to effectively capture the complexity and variability of medical images. A major challenge is posed when there is not enough annotated data, which inhibits the performance of the models to operate with high accuracy in various medical settings. And it's not helped by the reliance on medical professionals to not only annotate comprehensively pieces of this data-intensive model, but then to annotate them again and again and again as the model is trained on them.

- Data Privacy Preservation: Large datasets in medical imaging raise challenges to data privacy, especially in respect to private modalities, such as CT scans and MRIs. This poses the problem of aggregating and sharing medical imaging data for research and application purposes under rules such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), that lays down strict guidelines in management of personal patient data.

| Segmentation Methods | Algorithms | Architecture | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN Architectures | U-Net [23] | Expanding symmetric path for context collection and accurate localization. | It degrades with complex anatomical structures. |

| Deep Lab [24] | Uses atrous convolution to expand the field of vision without extra parameters. | High computational cost. | |

| Mask R-CNN [25] | Instance segmentation with additional branch for bounding box and segmentation mask prediction. | Requires a large amount of annotated data; class imbalance is challenging. | |

| Graph-CNN [26] | Models’ spatial interactions between image pixels using graph structures. | Requires careful design of graph-building algorithms; struggles with irregular graph topologies. | |

| Region-Based Methods | SRM [27] | Combines regions based on statistical metrics. | Data heterogeneity with varying intensity distributions degrades performance. |

| Atlas-Based | Uses anatomical atlases or templates for segmentation. | Errors occur in cases of anatomical variations or pathological conditions; time-consuming. | |

| Edge Detection | Segmentation [28] | technique based on edge detection. | |

| Other Methods | Domain Adaptation Techniques [29] | Enhances segmentation models with cross-domain generalization. | Target domain data with annotations not widely available; training instability. |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [30] | Uses adversarial networks to generate realistic images matching the input for improved segmentation. | Training instability |

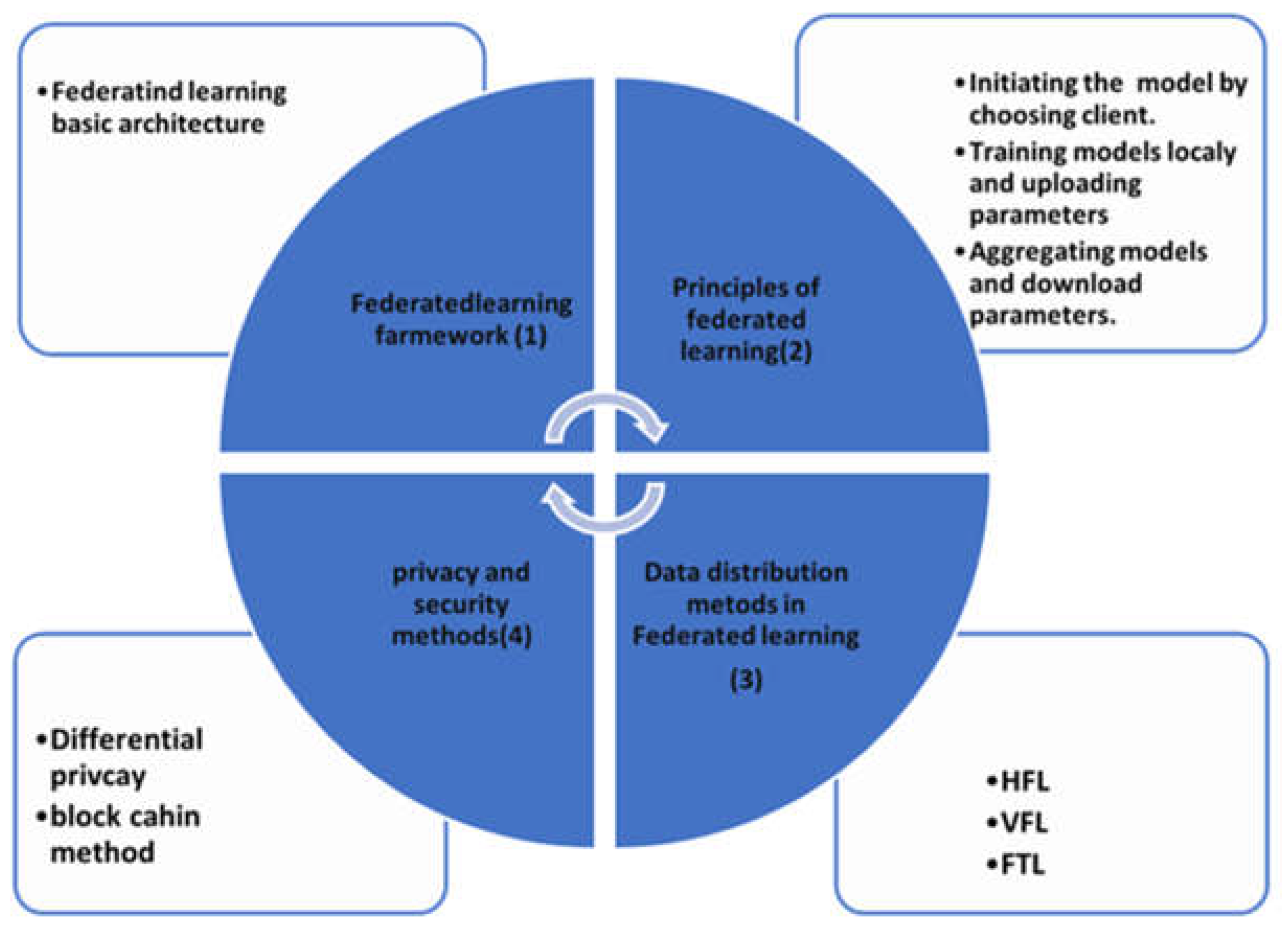

4. Federated Learning Key Phases

4.1. Federated Learning Architecture

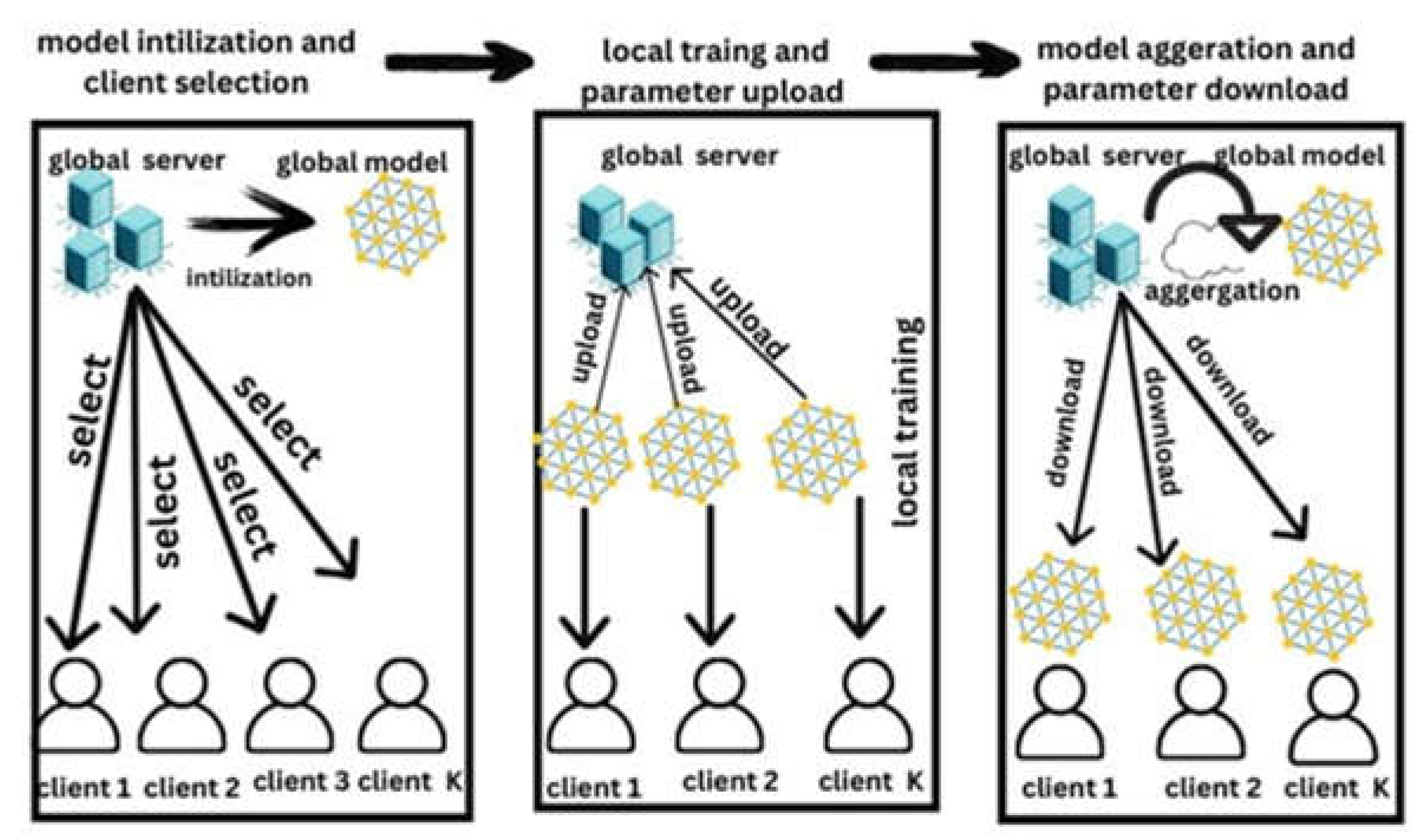

4.2. Principle of Federated Learning

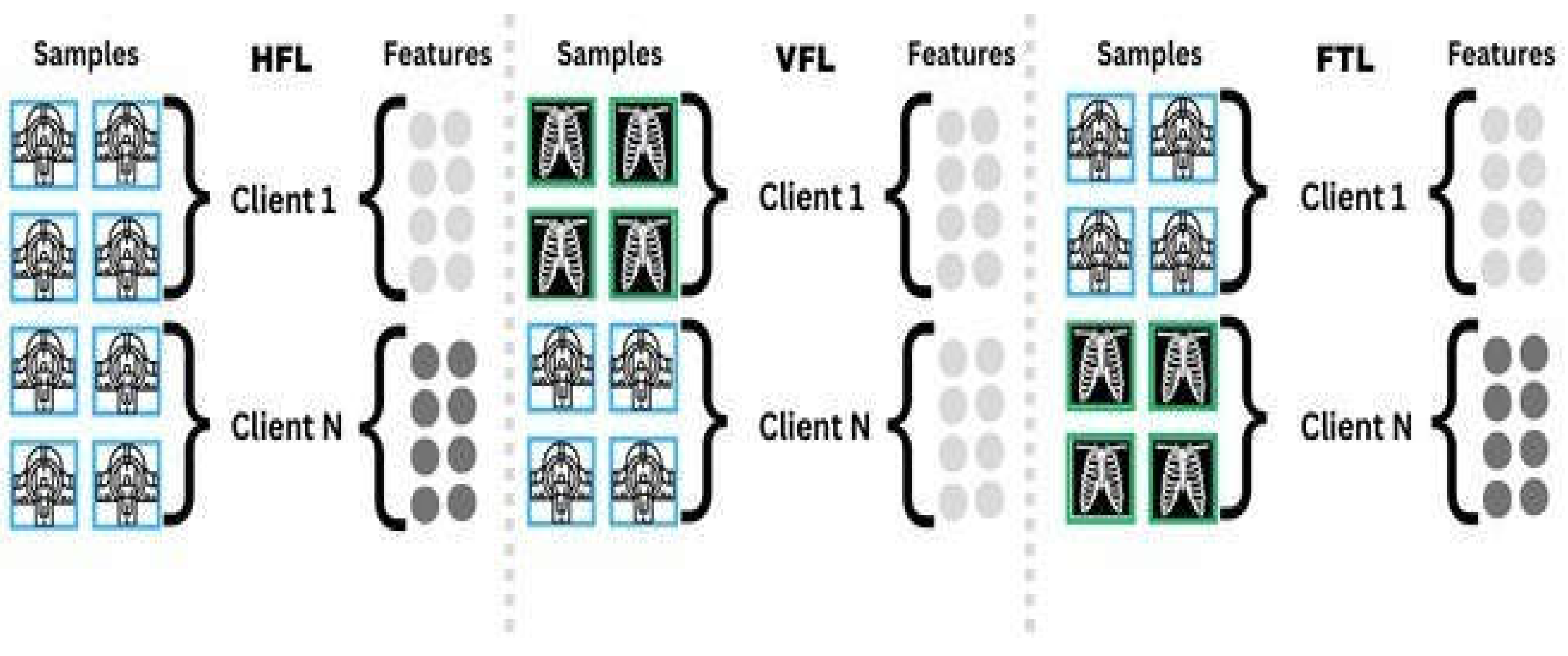

4.3. Data Distribution Methods in FL

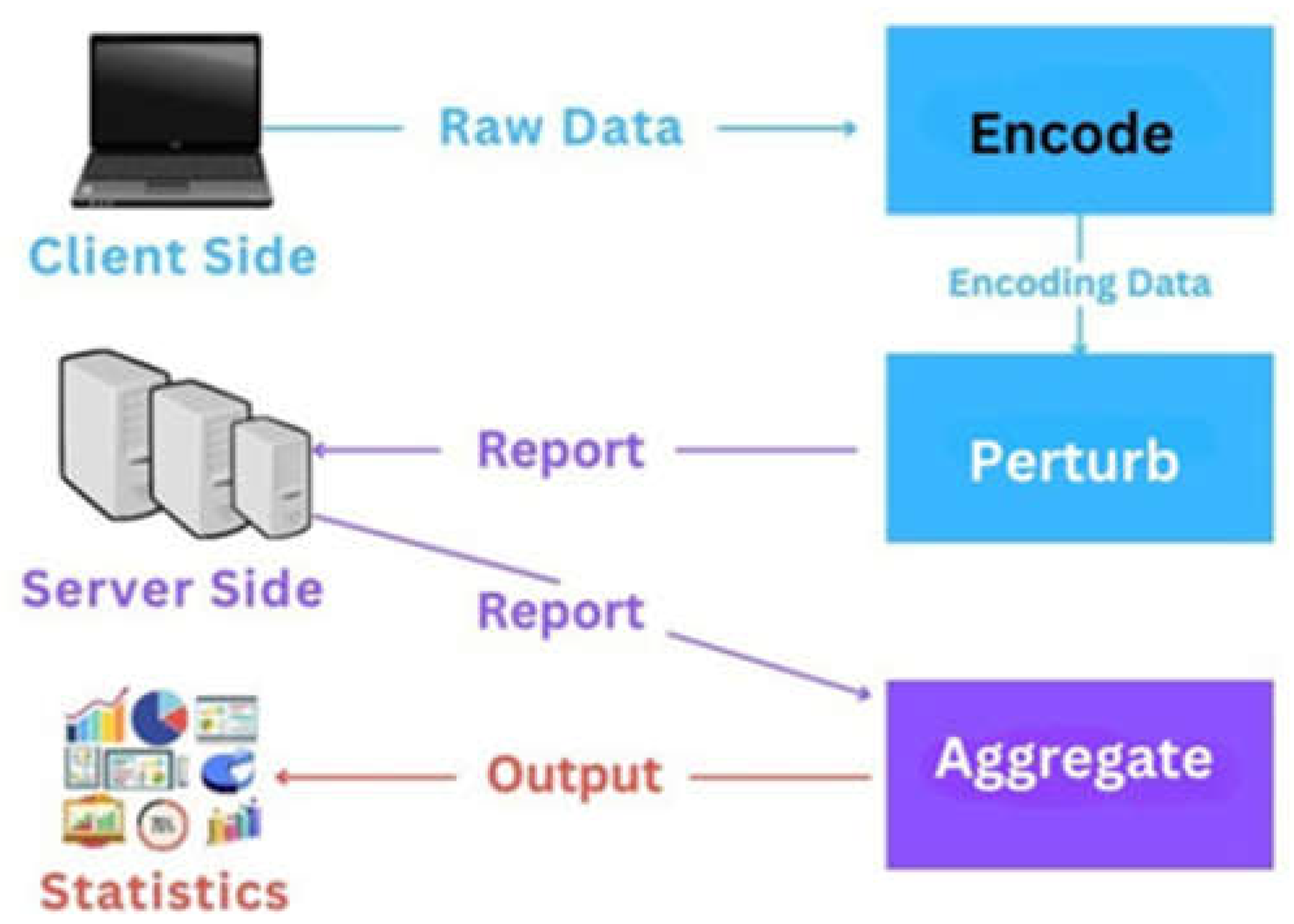

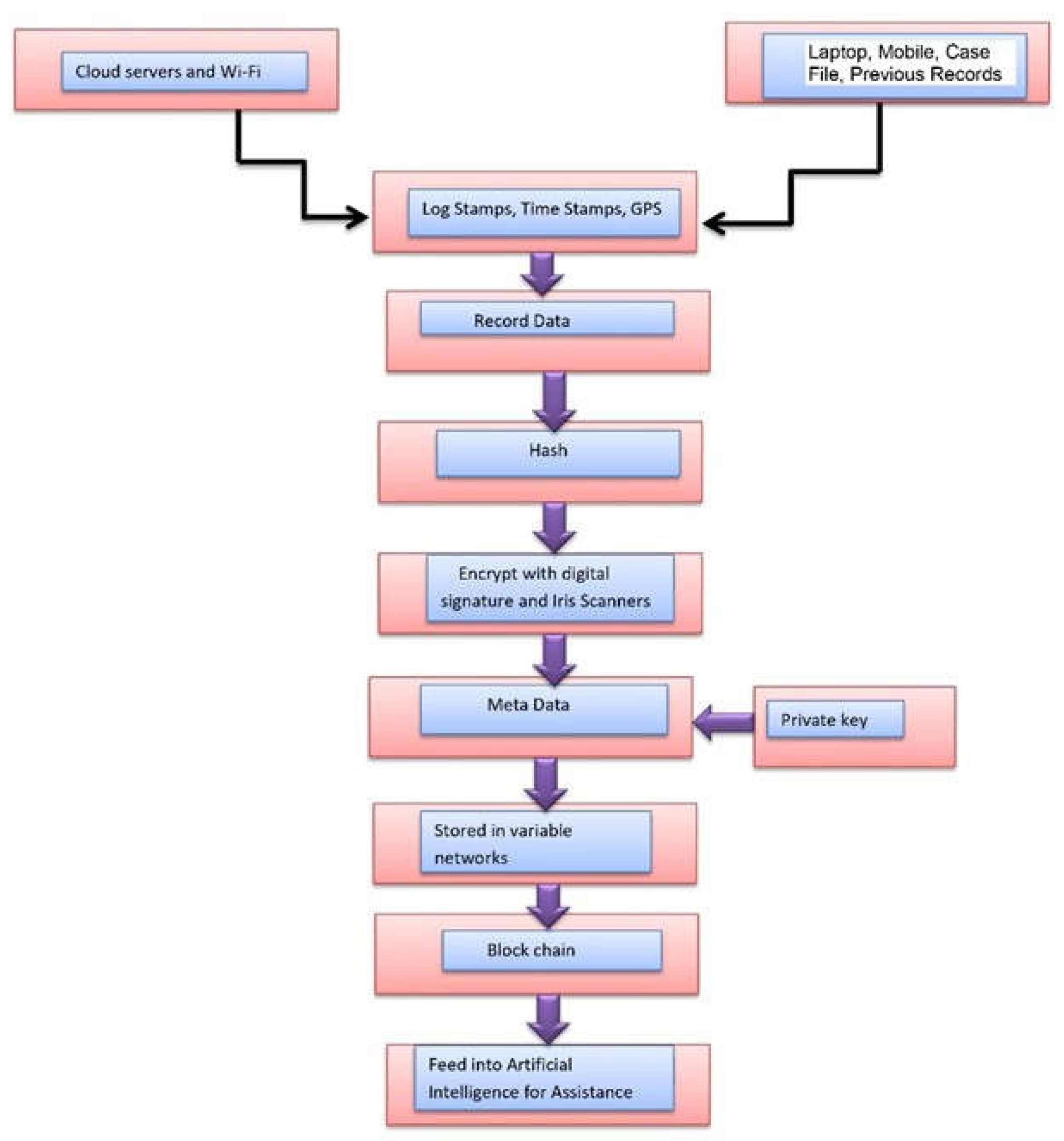

4.4. Data Privacy and Security Methods in Federated Models

5. Comprehensive Study of Federated Learning Frameworks for Medical Image Segmentation

5.1. Federated Learning Framework for Medical Image Segmentation

5.2. Effectiveness of Existing Methods

5.3. Challenges of Existing Methods

6. Organ Specific Segmentation Task in Existing Federated Learning Models

6.1. Federated Learning Models for Breast Tumor Segmentation

6.2. Federated Learning Models for Heart CT Images Segmentation

6.3. Federated Learning Models for Multi-Organ Segmentation

6.4. Characteristic Illustration of FL

- (1)

- Medical image segmentation for delineating organs and tumors is depended on deep learning architectures such as U-Net, V-Net, ResNet, and DenseNet [60]. Convolutional layers and skip connections, both of which are important when it comes to getting the precise segmentation, make these models unique for having the ability to capture intricate features in medical images. These models are adapted for distributed environments of federated learning (FL) in the context of privacy. Solving for the training on localized data overcomes the main privacy concerns, namely literary having the local data centralized in the same place.

- (2)

- Topics addressed by the fourteen reviewed studies are with regard to the application of FL in medical image segmentation as opposed to conventional deep learning ones generally relying on centralized data pools [62]. FL models keep different entities’ raw data private and ensure data integrity as different entities can be involved in model training without sharing data. The effectiveness of these FL models in medical image segmentation is evaluated in this review, looking at their capabilities, issues and how the model deals with challenges of both data privacy and institutional heterogeneity [63].

- (3)

- Datasets serve as an important part for the performance evaluation of FL models. Training and testing these models depend on such benchmark datasets, which usually include many medical images like MRIs and CT scans. This review studies the datasets used in the studied studies, with an emphasis on their size, kind and diversity, to understand how the FL models behave compared to different segmentation tasks [64].

- (4)

- Another important factor for medical image segmentation is image modality Mri, Ct, Xray and Ultrasound scan in their own ways for making an input about human anatomy resulting in different segmentation tasks respectively. This review highlights the fact that each dataset is evaluated with a specific image modality and, thus, a performance of FL models with different image modalities varies significantly [66].

- (5)

- Federated learning faces its own challenges in terms of the modalities of different images. An example of this is that MRI provides clear pictures of moisture tissues, whereas CT scans are better at observing bones and tough structures. Not only does each modality have different image quality, but also different data distribution among the participating clients, having different training dynamics and accuracy on FL models. We would like to discuss which modalities may require a finer attention in terms of focus and enhancement in FL frameworks, and also whether some of these modalities may be more difficult to provide to an appropriate training outcome and model precision [67].

- (6)

- The review closely reviews all specific organs that are under attack within current federated learning (FL) segmentation models for medical images. It points out to the focus of the segmentation on important organs of the body such as the brain, the lungs, the heart, and the liver, as well as the amount of research that has been done on each organ. The importance of this segmentation is to present research issues that are already well researched, and identify organs that require further study as the data on a particular organ is not complete or FL models are not working on it as expected [68]. These insights are important for judging in what direction research must focus to improve segmentation accuracy of organs that are less represented.

- (7)

- The other critical aspect is covered in the review is sample size. FL models’ training and evaluation effectiveness is directly dependent on the number of samples, or images that are available in each dataset [69]. The size of the dataset increases, the model performance improves by giving the model a wider basis for learning and generalization, though smaller dataset can potentially reduce these capabilities. It also calls the attention to the use of the sample sizes used in the studies and highlights how they are important to ensure the robustness and reliability of the federated learning models.

- (8)

- The number of clients participating in the federated learning setup also has an important influence in the efficiency of FL models. It is documented by this review that the number of participating clients, usually, is on three to ten institutions [70]. Thus, diversity and number of clients in particular affect generalization capabilities of models and bring in new variables (e.g., non IID data, increased communication overhead) that are major challenges when training models in federated settings. An analysis of client numbers facilitates evaluating of the scalability and practical performance of FL models for different institutional environments [80].

- (9)

- The review looks into the tools and the software platforms used for medical image analysis in federated learning frameworks [81]. This is a comprehensive overview of these tools, with description regarding the accessibility, architecture, ease of implementation, and also performance. This analysis helps in identifying the most appropriate and effective sources for FL tools for different medical imaging applications for matching tools to the right application. Table 4 of the review shows this detailed tool assessment, which provides a resource for researcher to find optimal tools for their particular needs [82].

7. Future Directions and Research Challenges

- (1)

- Scarcity of Annotated Data: One of the primary hurdles in federated learning is the limited availability of annotated data, which is vital for training accurate and reliable models. Self-supervised learning (SSL) strategies are increasingly recognized as a solution to leverage large volumes of unlabeled data alongside smaller annotated datasets [83]. SSL can significantly enhance model training by using unlabeled data to pre-train models before fine-tuning them on the scarce annotated data, improving both model accuracy and robustness.

- (2)

- Data Heterogeneity: Variability in medical data arises due to differences in imaging equipment, acquisition techniques, and processing protocols across various institutions [84]. This heterogeneity can severely impact the performance of FL models. Addressing these discrepancies involves implementing sophisticated preprocessing strategies, including normalization of imaging protocols and harmonization techniques. Current federated learning models like federated averaging may not always handle such data diversity effectively, especially when labeled data is unevenly distributed across participants. This calls for more advanced algorithms that can adapt to heterogeneous data without compromising model performance and accuracy.

- (3)

- Distribution Variance: Real world applications, for example, distribution variance across multicenter data set can present a wall to model convergence and deteriorate the local performance [85]. To address this, PFL attempts [86] to mitigate this by enabling sites to retain local parameters that better fit their data distributions. PFL works more on convolutional networks and hardly pay much attention to integrate the self-attentions to capture the long-range dependencies in data [87]. This reflects the lack of research for further personalization techniques that span a wider variety of network architectures, particularly those based on self-attention [88].

- (4)

- Generalizability to Unseen Data: A major bottleneck in multi-site federated learning framework is the extrapolation of models for data sources unseen [89]. Personalized models can outperform on local datasets, but underperform for new unseen datasets [90]. Strategies of continuous learning, fine tuning, assembling models could improve model adaptability and produce effective performance in a new participant site, leading to more good integration and scalability of federated learning systems in various clinical environment [91].

- (5)

- Aggregation Challenges: Model training and convergence rates vary depending on the quantity of data at a network site [92]. Federated learning approaches that are typical may not consider these discrepancies whose presence could distort the aggregate model performance [93,94]. It is important to counter this by using re-weighting of site contribution based on sample size or improving data representation from less represented sites. In particular [95,96], mentoring models to react to local data properties during training will facilitate consistency as well as effectiveness on domain-specific datasets [97].

8. Conclusion

References

- Antonelli M, Reinke A, Bakas S, Farahani K, Kopp-Schneider A, Landman BA, Litjens G, Menze B, Ronneberger O, Summers RM, Van Ginneken B. The medical segmentation decathlon. Nature communications. 2022 Jul 15;13(1):4128. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-022-30695-9.

- Wang R, Lei T, Cui R, Zhang B, Meng H, Nandi AK. Medical image segmentation using deep learning: A survey. IET image processing. 2022 Apr;16(5):1243-67. https://ietresearch.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1049/ipr2.12419.

- Chen X, Sun S, Bai N, Han K, Liu Q, Yao S, Tang H, Zhang C, Lu Z, Huang Q, Zhao G. A deep learning-based auto-segmentation system for organs-at-risk on whole-body computed tomography images for radiation therapy. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2021 Jul 1;160:175-84. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167814021062174.

- Antonelli M, Reinke A, Bakas S, Farahani K, Kopp-Schneider A, Landman BA, Litjens G, Menze B, Ronneberger O, Summers RM, Van Ginneken B. The medical segmentation decathlon. Nature communications. 2022 Jul 15;13(1):4128. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-022-30695-9.

- Sharma P, Diwakar M, Choudhary S. Application of edge detection for brain tumor detection. International Journal of Computer Applications. 2012 Jan 1;58(16). https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=0b9d799aa69e9e0b1e35ba5662d46fd8de9d7ffe.

- Bauer S, Wiest R, Nolte LP, Reyes M. A survey of MRI-based medical image analysis for brain tumor studies. Physics in Medicine & Biology. 2013 Jun 6;58(13):R97. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0031-9155/58/13/R97/meta.

- Anderson DJ, Ilieş I, Foy K, Nehls N, Benneyan JC, Lokhnygina Y, Baker AW. Early recognition and response to increases in surgical site infections using optimized statistical process control charts—the Early 2RIS Trial: a multicenter cluster randomized controlled trial with stepped wedge design. Trials. 2020 Dec;21:1-0. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13063-020-04802-4.

- Paul TU, Bandhyopadhyay SK. Segmentation of brain tumor from brain MRI images reintroducing K–means with advanced dual localization method. International Journal of Engineering Research and Applications. 2012 May;2(3):226-31. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=b6817724ba4309360ffaaea6b72fe806a72d9658.

- Chaddad A, Tanougast C. Cnn approach for predicting survival outcome of patients with covid-19. IEEE Internet of Things Journal. 2023 Mar 29;10(15):13742-53. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10086567/.

- Megerian JT, Dey S, Melmed RD, Coury DL, Lerner M, Nicholls CJ, Sohl K, Rouhbakhsh R, Narasimhan A, Romain J, Golla S. Evaluation of an artificial intelligence-based medical device for diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. NPJ digital medicine. 2022 ;5(1):57. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41746-022-00598-6.

- Sohan MF, Basalamah A. A systematic review on federated learning in medical image analysis. IEEE Access. 2023 Mar 21;11:28628-44. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10077569/.

- McMahan B, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, y Arcas BA. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. InArtificial intelligence and statistics 2017 Apr 10 (pp. 1273-1282). PMLR. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v54/mcmahan17a?ref=https://githubhelp.com.

- Wan S, Lu J, Fan P, Shao Y, Peng C, Letaief KB, Chuai J. How global observation works in Federated Learning: Integrating vertical training into Horizontal Federated Learning. IEEE Internet of Things Journal. 2023 Jan 5;10(11):9482-97. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10007657/.

- Li Q, Wen Z, Wu Z, Hu S, Wang N, Li Y, Liu X, He B. A survey on federated learning systems: Vision, hype and reality for data privacy and protection. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering. 2021 Nov 2;35(4):3347-66. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9599369/.

- Li T, Sahu AK, Talwalkar A, Smith V. Federated learning: Challenges, methods, and future directions. IEEE signal processing magazine. 2020 ;37(3):50-60. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9084352/.

- Yang Q, Liu Y, Chen T, Tong Y. Federated machine learning: Concept and applications. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST). 2019 Jan 28;10(2):1-9. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3298981.

- Antunes RS, André da Costa C, Küderle A, Yari IA, Eskofier B. Federated learning for healthcare: Systematic review and architecture proposal. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST). 2022 ;13(4):1-23. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3501813.

- Rieke N, Hancox J, Li W, Milletari F, Roth HR, Albarqouni S, Bakas S, Galtier MN, Landman BA, Maier-Hein K, Ourselin S. The future of digital health with federated learning. NPJ digital medicine. 2020 Sep 14;3(1):1-7. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41746-020-00323-1/1000.

- Nguyen DC, Pham QV, Pathirana PN, Ding M, Seneviratne A, Lin Z, Dobre O, Hwang WJ. Federated learning for smart healthcare: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys (Csur). 2022 Feb 3;55(3):1-37. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3501296.

- Liu X, Gao K, Liu B, Pan C, Liang K, Yan L, Ma J, He F, Zhang S, Pan S, Yu Y. Advances in deep learning-based medical image analysis. Health Data Science. 2021;2021. https://spj.science.org/doi/pdf/10.34133/2021/8786793?adobe_mc=MCMID%3D14000678418609464879081490540568399952%7CMCORGID%3D242B6472541199F70A4C98A6%2540AdobeOrg%7CTS%3D1670889600.

- Santos, DF. Tackling Lung Cancer: Advanced Image Analysis and Deep Learning for Early Detection. Authorea Preprints. 2023 Oct 31. https://www.techrxiv.org/doi/full/10.36227/techrxiv.23537685.v1.

- Yang L, He J, Fu Y, Luo Z. Federated Learning for Medical Imaging Segmentation via Dynamic Aggregation on Non-IID Data Silos. Electronics. 2023 Apr 3;12(7):1687. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-9292/12/7/1687.

- Ronneberger, O. , Fischer, P. and Brox, T., 2015. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, -9, 2015, proceedings, part III 18 (pp. 234-241). Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28.

- Chen, LC. Rethinking atrous convolution for semantic image segmentation. arXiv preprint com/citations? arXiv:1706.05587.

- He K, Gkioxari G, Dollár P, Girshick R. Mask r-cnn. InProceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision 2017 (pp. 2961-2969). http://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_iccv_2017/html/He_Mask_R-CNN_ICCV_2017_paper.html.

- Ding K, Zhou M, Wang Z, Liu Q, Arnold CW, Zhang S, Metaxas DN. Graph convolutional networks for multi-modality medical imaging: Methods, architectures, and clinical applications. 0891; arXiv:2202.08916.

- Li E, Guo J, Oh SJ, Luo Y, Oliveros HC, Du W, Arano R, Kim Y, Chen YT, Eitson J, Lin DT. Anterograde transneuronal tracing and genetic control with engineered yellow fever vaccine YFV-17D. Nature methods. 2021 Dec;18(12):1542-51. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41592-021-01319-9. 4159.

- Liu X, Song L, Liu S, Zhang Y. A review of deep-learning-based medical image segmentation methods. Sustainability. 2021 Jan 25;13(3):1224. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/3/1224. 2071.

- Yao K, Su Z, Huang K, Yang X, Sun J, Hussain A, Coenen F. A novel 3D unsupervised domain adaptation framework for cross-modality medical image segmentation. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics. 2022 Mar 24;26(10):4976-86. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9741336/. 9741.

- Jeong JJ, Tariq A, Adejumo T, Trivedi H, Gichoya JW, Banerjee I. Systematic review of generative adversarial networks (GANs) for medical image classification and segmentation. Journal of Digital Imaging. 2022 Apr;35(2):137-52. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10278-021-00556-w. 1007.

- Zhuang F, Qi Z, Duan K, Xi D, Zhu Y, Zhu H, Xiong H, He Q. A comprehensive survey on transfer learning. Proceedings of the IEEE. 2020 Jul 7;109(1):43-76. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9134370/. 9134.

- Guan H, Yap PT, Bozoki A, Liu M. Federated learning for medical image analysis: A survey. Pattern Recognition. 2024 Mar 12:110424. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0031320324001754. 0031.

- Shen C, Wang P, Roth HR, Yang D, Xu D, Oda M, Wang W, Fuh CS, Chen PT, Liu KL, Liao WC. Multi-task federated learning for heterogeneous pancreas segmentation. InClinical Image-Based Procedures, Distributed and Collaborative Learning, Artificial Intelligence for Combating COVID-19 and Secure and Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning: 10th Workshop, CLIP 2021, Second Workshop, DCL 2021, First Workshop, LL-COVID19 2021, and First Workshop and Tutorial, PPML 2021, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2021, Strasbourg, France, and October 1, 2021, Proceedings 2 2021 (pp. 101-110). Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-90874-4_10.

- Shen C, Wang P, Roth HR, Yang D, Xu D, Oda M, Wang W, Fuh CS, Chen PT, Liu KL, Liao WC. Multi-task federated learning for heterogeneous pancreas segmentation. InClinical Image-Based Procedures, Distributed and Collaborative Learning, Artificial Intelligence for Combating COVID-19 and Secure and Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning: 10th Workshop, CLIP 2021, Second Workshop, DCL 2021, First Workshop, LL-COVID19 2021, and First Workshop and Tutorial, PPML 2021, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2021, Strasbourg, France, and October 1, 2021, Proceedings 2 2021 (pp. 101-110). Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-90874-4_10.

- Qi X, Yang G, He Y, Liu W, Islam A, Li S. Contrastive re-localization and history distillation in federated cmr segmentation. InInternational Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 2022 Sep 16 (pp. 256-265). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-16443-9_25. 1007.

- Misonne T, Jodogne S. Federated learning for heart segmentation. In2022 IEEE 14th Image, Video, and Multidimensional Signal Processing Workshop (IVMSP) 2022 Jun 26 (pp. 1-5). IEEE. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9816345/.

- Zhou J, Zhou L, Wang D, Xu X, Li H, Chu Y, Han W, Gao X. Personalized and privacy-preserving federated heterogeneous medical image analysis with pppml-hmi. Computers in Biology and Medicine. 2024 Feb 1;169:107861. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010482523013264.

- Xu X, Deng HH, Gateno J, Yan P. Federated multi-organ segmentation with inconsistent labels. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2023 Apr 25;42(10):2948-60. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10107904/. 1010.

- Kanhere AU, Kulkarni P, Yi PH, Parekh VS. SegViz: A federated-learning based framework for multi-organ segmentation on heterogeneous data sets with partial annotations. 0707; arXiv:2301.07074.

- Xu X, Deng HH, Chen T, Kuang T, Barber JC, Kim D, Gateno J, Xia JJ, Yan P. Federated cross learning for medical image segmentation. InMedical Imaging with Deep Learning 2024 Jan 23 (pp. 1441-1452). PMLR. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v227/xu24a.html.

- Li L, Tang Y, Zhang Y, Li Z, Zhou G, Zhou H, Zhang Z. Federated Multi-organ Dynamic Attention Segmentation Network with Small CT Dataset. InInternational Workshop on Computational Mathematics Modeling in Cancer Analysis 2023 Oct 8 (pp. 42-50). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-45087-7_5.

- Yang L, He J, Fu Y, Luo Z. Federated Learning for Medical Imaging Segmentation via Dynamic Aggregation on Non-IID Data Silos. Electronics. 2023 Apr 3;12(7):1687. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-9292/12/7/1687. 2079.

- Mazher M, Razzak I, Qayyum A, Tanveer M, Beier S, Khan T, Niederer SA. Self-supervised spatial–temporal transformer fusion based federated framework for 4D cardiovascular image segmentation. Information Fusion. 2024 Jun 1;106:102256. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1566253524000344. 1566.

- Lin L, Liu Y, Wu J, Cheng P, Cai Z, Wong KK, Tang X. FedLPPA: Learning Personalized Prompt and Aggregation for Federated Weakly-supervised Medical Image Segmentation. 1750; arXiv:2402.17502.

- Wu N, Sun Z, Yan Z, Yu L. FedA3I: Annotation Quality-Aware Aggregation for Federated Medical Image Segmentation against Heterogeneous Annotation Noise. InProceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2024 Mar 24 (Vol. 38, No. 14, pp. 15943-15951). https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/29525. 2952.

- Liu Y, Luo G, Zhu Y. Fedfms: Exploring federated foundation models for medical image segmentation. InInternational Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 2024 Oct 6 (pp. 283-293). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-72111-3_27. 1007.

- Al-Dhabyani W, Gomaa M, Khaled H, Fahmy A. Dataset of breast ultrasound images. Data in brief. 2020 Feb 1;28:104863. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352340919312181. 2352.

- Zhang Y, Xian M, Cheng HD, Shareef B, Ding J, Xu F, Huang K, Zhang B, Ning C, Wang Y. BUSIS: a benchmark for breast ultrasound image segmentation. InHealthcare 2022 Apr 14 (Vol. 10, No. 4, p. 729). MDPI. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/10/4/729. 2227.

- Umer MJ, Sharif M, Wang SH. Breast cancer classification and segmentation framework using multiscale CNN and U-shaped dual decoded attention network. Expert Systems. 2022 Nov 14:e13192. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/exsy.13192. 1319.

- Rotemberg V, Kurtansky N, Betz-Stablein B, Caffery L, Chousakos E, Codella N, Combalia M, Dusza S, Guitera P, Gutman D, Halpern A. A patient-centric dataset of images and metadata for identifying melanomas using clinical context. Scientific data. 2021 Jan 28;8(1):34. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-021-00815-z. 4159.

- Kumar K, Yeo AU, McIntosh L, Kron T, Wheeler G, Franich RD. Deep Learning Auto-Segmentation Network for Pediatric Computed Tomography Data Sets: Can We Extrapolate From Adults?. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics. 2024 Jul 15;119(4):1297-306. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360301624002451. 0360.

- Hofmanninger J, Prayer F, Pan J, Röhrich S, Prosch H, Langs G. Automatic lung segmentation in routine imaging is primarily a data diversity problem, not a methodology problem. European Radiology Experimental. 2020 Dec;4:1-3. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s41747-020-00173-2. 1186.

- Campello VM, Gkontra P, Izquierdo C, Martin-Isla C, Sojoudi A, Full PM, Maier-Hein K, Zhang Y, He Z, Ma J, Parreno M. Multi-centre, multi-vendor and multi-disease cardiac segmentation: the M&Ms challenge. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2021 Jun 17;40(12):3543-54. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9458279/. 9458.

- Sakaridis C, Dai D, Van Gool L. ACDC: The adverse conditions dataset with correspondences for semantic driving scene understanding. InProceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 2021 (pp. 10765-10775). http://openaccess.thecvf.com/content/ICCV2021/html/.htmlSakaridis_ACDC_The_Adverse_Conditions_Dataset_With_Correspondences_for_Semantic_Driving_ICCV_2021_paper.

- Amara U, Rashid S, Mahmood K, Nawaz MH, Hayat A, Hassan M. Insight into prognostics, diagnostics, and management strategies for SARS CoV-2. RSC advances. 2022;12(13):8059-94. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2022/ra/d1ra07988c. 2022.

- Doiron D, Marcon Y, Fortier I, Burton P, Ferretti V. Software Application Profile: Opal and Mica: open-source software solutions for epidemiological data management, harmonization and dissemination. International journal of epidemiology. 2017 Oct 1;46(5):1372-8. https://academic.oup.com/ije/article-pdf/doi/10.1093/ije/dyx180/24172864/dyx180.pdf.

- Roth H, Farag A, Turkbey EB, Lu L, Liu J, Summers RM. Data from pancreas-CT. (No Title). 2016 Jan 1. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1881991018017321216. 1881.

- Antonelli M, Reinke A, Bakas S, Farahani K, Kopp-Schneider A, Landman BA, Litjens G, Menze B, Ronneberger O, Summers RM, Van Ginneken B. The medical segmentation decathlon. Nature communications. 2022 Jul 15;13(1):4128. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-022-30695-9. 4146.

- Schaffter T, Buist DS, Lee CI, Nikulin Y, Ribli D, Guan Y, Lotter W, Jie Z, Du H, Wang S, Feng J. Evaluation of combined artificial intelligence and radiologist assessment to interpret screening mammograms. JAMA network open. 2020 Mar 2;3(3):e200265-. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/article-abstract/2761795. 2761.

- Tschandl P, Rosendahl C, Kittler H. The HAM10000 dataset, a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions. Scientific data. 2018 Aug 14;5(1):1-9. https://www.nature.com/articles/sdata2018161. 2018.

- Aerts HJ, Velazquez ER, Leijenaar RT, Parmar C, Grossmann P, Carvalho S, Bussink J, Monshouwer R, Haibe-Kains B, Rietveld D, Hoebers F. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nature communications. 2014 Jun 3;5(1):4006. https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms5006.

- Heller N, Sathianathen N, Kalapara A, Walczak E, Moore K, Kaluzniak H, Rosenberg J, Blake P, Rengel Z, Oestreich M, Dean J. The kits19 challenge data: 300 kidney tumor cases with clinical context, ct semantic segmentations, and surgical outcomes. arXiv:1904.00445.

- Prior F, Smith K, Sharma A, Kirby J, Tarbox L, Clark K, Bennett W, Nolan T, Freymann J. The public cancer radiology imaging collections of The Cancer Imaging Archive. Scientific data. 2017 Sep 19;4(1):1-7. https://www.nature.com/articles/sdata2017124. 2017.

- Litjens G, Toth R, Van De Ven W, Hoeks C, Kerkstra S, Van Ginneken B, Vincent G, Guillard G, Birbeck N, Zhang J, Strand R. Evaluation of prostate segmentation algorithms for MRI: the PROMISE12 challenge. Medical image analysis. 2014 Feb 1;18(2):359-73. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1361841513001734. 1361.

- Xu X, Deng HH, Chen T, Kuang T, Barber JC, Kim D, Gateno J, Xia JJ, Yan P. Federated cross learning for medical image segmentation. InMedical Imaging with Deep Learning 2024 Jan 23 (pp. 1441-1452). PMLR. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v227/xu24a.html.

- Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. InMedical image computing and computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, -9, 2015, proceedings, part III 18 2015 (pp. 234-241). Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28.

- Clark K, Vendt B, Smith K, Freymann J, Kirby J, Koppel P, Moore S, Phillips S, Maffitt D, Pringle M, Tarbox L. The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA): maintaining and operating a public information repository. Journal of digital imaging. 2013 Dec;26:1045-57. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/S10278-013-9622-7. 1007.

- Ji Y, Bai H, Ge C, Yang J, Zhu Y, Zhang R, Li Z, Zhanng L, Ma W, Wan X, Luo P. Amos: A large-scale abdominal multi-organ benchmark for versatile medical image segmentation. Advances in neural information processing systems. 2022 Dec 6;35:36722-32. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2022/hash/ee604e1bedbd069d9fc9328b7b9584be-Abstract-Datasets_and_Benchmarks.html.

- Keller A, Gerkin RC, Guan Y, Dhurandhar A, Turu G, Szalai B, Mainland JD, Ihara Y, Yu CW, Wolfinger R, Vens C. Predicting human olfactory perception from chemical features of odor molecules. Science. 2017 Feb 24;355(6327):820-6. https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.aal2014. 2014.

- Legallois D, Mpouli S, Camps JB, des Chartes ÉN, Galleron I, Herrmann B, Kraif O, Poibeau T. Workshops, conferences, and CfPs. https://discourse.computational-humanities-research.org/t/workshops-conferences-and-cfps/985/23.

- Ahmed, M. Medical image segmentation using attention-based deep neural networks. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:1477227.

- Li B, Zhang Y, Caneparo L, Guo W, Meng Q. Energy use in residential buildings for sustainable development: The fifth Solar Decathlon Europe revelations. Heliyon. 2024 ;10(9). https://www.cell.com/heliyon/fulltext/S2405-8440(24)06732-X.

- Ji Y, Bai H, Ge C, Yang J, Zhu Y, Zhang R, Li Z, Zhanng L, Ma W, Wan X, Luo P. Amos: A large-scale abdominal multi-organ benchmark for versatile medical image segmentation. Advances in neural information processing systems. 2022 Dec 6;35:36722-32. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2022/hash/ee604e1bedbd069d9fc9328b7b9584be-Abstract-Datasets_and_Benchmarks.html.

- Draelos RL, Carin L. Explainable multiple abnormality classification of chest CT volumes. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. 2022 Oct 1;132:102372. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0933365722001312.

- Ma J, Wang Y, An X, Ge C, Yu Z, Chen J, Zhu Q, Dong G, He J, He Z, Cao T. Toward data-efficient learning: A benchmark for COVID-19 CT lung and infection segmentation. Medical physics. 2021 Mar;48(3):1197-210. https://aapm.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/mp.14676.

- Babu LS, Kumar SS, Mohan N, Krishankumar R, Ravichandran KS, Senapati T, Sikha OK. An Intelligent Computational Model with Dynamic Mode Decomposition and Attention Features for COVID-19 Detection from CT Scan Images. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-3357602/latest.

- Zhou W, Tao X, Wei Z, Lin L. Automatic segmentation of 3D prostate MR images with iterative localization refinement. Digital Signal Processing. 2020 Mar 1;98:102649. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1051200419302039.

- Sivaswamy J, Krishnadas S, Chakravarty A, Joshi G, Tabish AS. A comprehensive retinal image dataset for the assessment of glaucoma from the optic nerve head analysis. JSM Biomedical Imaging Data Papers. 2015 Mar;2(1):1004. https://cdn.iiit.ac.in/cdn/cvit.iiit.ac.in/images/ConferencePapers/2015/Arunava2015AComprehensive.

- Fumero F, Alayón S, Sanchez JL, Sigut J, Gonzalez-Hernandez M. RIM-ONE: An open retinal image database for optic nerve evaluation. In2011 24th international symposium on computer-based medical systems (CBMS) 2011 Jun 27 (pp. 1-6). IEEE. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/5999143/.

- Orlando JI, Fu H, Breda JB, Van Keer K, Bathula DR, Diaz-Pinto A, Fang R, Heng PA, Kim J, Lee J, Lee J. Refuge challenge: A unified framework for evaluating automated methods for glaucoma assessment from fundus photographs. Medical image analysis. 2020 Jan 1;59:101570. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1361841519301100.

- Wu J, Fang H, Li F, Fu H, Lin F, Li J, Huang Y, Yu Q, Song S, Xu X, Xu Y. Gamma challenge: glaucoma grading from multi-modality images. Medical Image Analysis. 2023 Dec 1;90:102938. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1361841523001986.

- Agarwal A, Raman R, Lakshminarayanan V. The foveal avascular zone image database (fazid). InApplications of Digital Image Processing XLIII 2020 Aug 21 (Vol. 11510, pp. 507-512). SPIE. https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie/11510/1151027/The-Foveal-Avascular-Zone-Image-Database-FAZID/10.1117/12.2567580.short.

- Tan X, Chen X, Meng Q, Shi F, Xiang D, Chen Z, Pan L, Zhu W. OCT2Former: A retinal OCT-angiography vessel segmentation transformer. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine. 2023 ;233:107454. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169260723001207.

- Wang Y, Shen Y, Yuan M, Xu J, Yang B, Liu C, Cai W, Cheng W, Wang W. A deep learning-based quality assessment and segmentation system with a large-scale benchmark dataset for optical coherence tomographic angiography image. arXiv:2107.10476.

- Ma Y, Hao H, Xie J, Fu H, Zhang J, Yang J, Wang Z, Liu J, Zheng Y, Zhao Y. ROSE: a retinal OCT-angiography vessel segmentation dataset and new model. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2020 Dec 7;40(3):928-39. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9284503/.

- Bernal J, Sánchez FJ, Fernández-Esparrach G, Gil D, Rodríguez C, Vilariño F. WM-DOVA maps for accurate polyp highlighting in colonoscopy: Validation vs. saliency maps from physicians. Computerized medical imaging and graphics. 2015 Jul 1;43:99-111. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0895611115000567.

- Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. Imaging in the era of molecular oncology. Nature. 2008 Apr 3;452(7187):580-9. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature06917.

- Silva J, Histace A, Romain O, Dray X, Granado B. Toward embedded detection of polyps in wce images for early diagnosis of colorectal cancer. International journal of computer assisted radiology and surgery. 2014 Mar;9:283-93. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11548-013-0926-3.

- Cassidy B, Kendrick C, Brodzicki A, Jaworek-Korjakowska J, Yap MH. Analysis of the ISIC image datasets: Usage, benchmarks and recommendations. Medical image analysis. 2022 Jan 1;75:102305. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1361841521003509.

- Siomos V, Tarroni G, Passerrat-Palmbach J. FeTS Challenge 2022 Task 1: Implementing FedMGDA+ and a New Partitioning. InInternational MICCAI Brainlesion Workshop 2022 Sep 18 (pp. 154-160). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-44153-0_15.

- Gamper J, Koohbanani NA, Benes K, Graham S, Jahanifar M, Khurram SA, Azam A, Hewitt K, Rajpoot N. Pannuke dataset extension, insights and baselines. arXiv:2003.10778.

- Ziller A, Trask A, Lopardo A, Szymkow B, Wagner B, Bluemke E, Nounahon JM, Passerat-Palmbach J, Prakash K, Rose N, Ryffel T. Pysyft: A library for easy federated learning. Federated Learning Systems: Towards Next-Generation AI. 2021:111-39. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-70604-3_5.

- Reina GA, Gruzdev A, Foley P, Perepelkina O, Sharma M, Davidyuk I, Trushkin I, Radionov M, Mokrov A, Agapov D, Martin J. OpenFL: An open-source framework for Federated Learning. arXiv:2105.06413.

- Ziller A, Passerat-Palmbach J, Ryffel T, Usynin D, Trask A, Junior ID, Mancuso J, Makowski M, Rueckert D, Braren R, Kaissis G. Privacy-preserving medical image analysis. arXiv:2012.06354.

- Silva S, Altmann A, Gutman B, Lorenzi M. Fed-biomed: A general open-source frontend framework for federated learning in healthcare. InDomain Adaptation and Representation Transfer, and Distributed and Collaborative Learning: Second MICCAI Workshop, DART 2020, and First MICCAI Workshop, DCL 2020, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2020, Lima, Peru, –8, 2020, Proceedings 2 2020 (pp. 201-210). Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-60548-3_20.

- Garcia Bernal, D. Decentralizing large-scale natural language processing with federated learning. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:1455825.

- Wang S, Dai W, Li GY. Distributionally Robust Beamforming and Estimation of Wireless Signals. arXiv preprint 1 arXiv:abs/2401.12345, 2345.

| Ref | Year | FL Technique | Strength of Study | Weakness of Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [33] | 2021 | Multi-task FL method | Performs automated segmentation of pancreas and pancreatic tumor. | Small sample size in the dataset. |

| [34] | 2022 | FedMix | Reduces expert annotation load and integrates effectively with adaptive aggregation in a fully-supervised context. | Requires a huge number of annotated data, which is expensive and time-consuming. |

| [35] | 2022 | FedCRLD | Provides effective results when dealing with heterogeneous data from multiple sources ensuring robust performance across diverse imaging conditions and centers. | Data heterogeneity requires extensive preprocessing and standardization efforts. |

| [36] | 2022 | The Federated Equal Chances | Achieves more equitable performance across different classes, ensuring that minority classes receive adequate attention and are accurately segmented. | High computational cost. Risk of overfitting to specific data characteristics. |

| [37] | 2023 | PPPML-HMI | Enhances the accuracy and reliability of medical image analysis while maintaining strict privacy standards. | Aggregation issues may occur since multiple clients are incorporating. |

| [38] | 2023 | Fed-MENU | Effectively handles partially annotated data, improving segmentation performance while preserving privacy through federated learning. | The architecture integration and implementation of personalizing models for different data sources can become more complicated in cases when personalization has to work with different data sources and privacy should be considered. |

| [39] | 2023 | SegViz | Effectively handles undisturbed data with partial labels and supports multi-task learning within a federated framework improves flexibility and model utility. | Multi-task learning may lead to performance consistency and efficiency problems in some cases. |

| [40] | 2023 | FedCross | Enhances segmentation results and predicts uncertainty maps, providing robust performance and reliability in clinical settings. | Accounts may not be efficient if the data is not unbalanced and if there are only a few clients. |

| [41] | 2023 | U-DANet | Effectively handles multi-organ segmentation, improving accuracy and detail in distinguishing multiple organs within a single framework. | High computational cost. |

| [42] | 2023 | MixFedGAN | Improves stability and performance by dynamically aggregating model updates, reducing the impact of low-performing clients. | Adding extra complexity in implementation and maintenance may be required by the dynamic aggregation method. |

| [43] | 2024 | SSFL | SSL, spatial-temporal processing, and transformers, enhancing performance across various types of cardiovascular image segmentation. | Having many advanced techniques combined may result in an increased complexity and increased computational demands. |

| [44] | 2024 | FedLPPA | Provides unique data distributions for each local model and incorporates supervision sparsity to personalize the framework. | In case of inconsistencies in data quality and annotations, the framework suffers from the segmentation accuracy and robustness. |

| [45] | 2024 | FedA3I | Improved accuracy and robustness. Enhanced segmentation. | Due to the model complexity in handling quality of annotation and pixel-wise noise, it may cause rise in the computational overhead and implementation challenges. |

| [46] | 2024 | FedFMS | Better model optimization is achieved by FedFMS since FedMSA is further used to improve segmentation accuracy while FedSAM is employed for hyperparameter tuning. | However, the overall system’s complexity and computational requirements may be increased due to the complexity of managing two different models. |

| Local Model | FL | Dataset | Modality | Type of Modality | Organ | Samples (n) | Clients (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | DTA DWA [33] |

TCIA [57] MSD [58] Synapse [59] |

CT | 3D | pancreas | 231 780 |

3 |

| Unet | FedMix [34] | BUS [47], BUSIS [48], UDIAT [49], HAM10K [60] |

Ultrasound | 2D | Breast | 562 163 |

3 |

| M&M [53] | 3D | Skin | 2259 3363 439 3954 |

4 | |||

| 3D U-net | FedCRLD [35] federated equal chances |

and Emidec [61] NSCLC- Radiomics [50] |

CMR | 3D | Heart | 131 210 281 |

6 |

| Unet | [36] | Pediatric-CT-SEG [51] LCTSC [52] MSD [58] |

CT | 3D | Heart Spleen |

41 200 30 |

3 |

| 3D-UNet | SegViz [39] | Kits [62] BTCV [61] | CT | 3D | Liver Pancreas Abdominal | 35,747 20 1100 373 |

4 |

| MSD [58] | 2D | Abdominal | |||||

| 3D U-Net | FedCrossEns [40] | [63] PROMISE12[64] PROSTATE [65] FLARE22[66] |

MRI | 3D | Spleen Liver Pancreas Stomach |

100 | 4 |

| U-DANet | U-dynamic model based federal learning framework [41] | TCIA [67] AMOS [68] Synapse [69] |

CT | 3D | Liver Kidney Pancreas Spleen Abdominal |

80 12 60 3954 |

4 |

| MENU-Net | Fed-Menu [38] | LiTS [70] kiTS [71] MSD [58] AMOS [72] BTCV [73] |

CT | 3D | Multi-organ Abdominal Lungs |

1902 | 5 |

| CSAHE | PPPML-HMI [37] | RAD-ChestCT dataset [74] | CT | 2D | Lungs | 101 159 400 200 |

4 |

| COVID-19-CT [55] COVID-19-1110[75] | CT | 2D | Pelvic area | ||||

| GAN | MixFedGAN [42] | COVID-19-9[76] COVID-19-CT [76] PROMISE12[64] NCI-ISBI [77] | MRI | 2D | Heart | 304 200 300 1012 39 | 4 |

| Self-supervised federated | COVID-19-9[76] COVID-19-CT [76] PROMISE12[64] NCI-ISBI [77] | CT | 3D | ||||

| M&M challenge [53] | |||||||

| GAN | learning framework [43] | ACDC [54] | CMR | 612 390 196 1000 |

3 | ||

| Drishti-GS1 [78] RIM-ONE-r3[79] REFUGE-train [80] GAMMA [81] |

Fundus | ||||||

| Vanilla U-Net | FedLPPA [44] | FAZID [82] OCTA500-3M [83] OCTA500-6M [83] OCTA-25K (3x3) [84] ROSE [85] |

OCTA (Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography) |

Skin | 2600 | 3 | |

| CVC-Clinic DB [86] CVC-Colon DB [87] ETIS-Larib[88] ISIC 2017[89] BUS[47], BUSIS[48], | Endoscopy Ultrasound |

||||||

| U-Net | FedA3I [45] | UDIAT [59], NCI-ISBI 2013[77] |

MRI | Breast Prostate cancer |

780 562 163 586 |

||

| SAM FMA | FedFMS [46] | FeTS 2022[90] PanNuke [91] |

Histopathological image ultrasound | 2D | Brain tumor Nuclei Fundus |

200,000 1 million |

4 |

| Software | Accessibility | Architecture | Implementation | Performance | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PySyft [92] | Open-source | Integrates well with ML/DL models | Python; Can run on Linux, MacOS, Windows | Secure framework | Development of deep learning by the PySyft ecosystem; supports PyTorch, Scikit-Learn, NumPy |

| Open FL [93] | Open-source | Developed FeTS federated rumor segmentation platform | Python | Decentralized, privacy-preserving deep learning platform | Works for real-time application of FL |

| PriMIA [94] | Open-source | Decentralized | Python and PyTorch | Performs data analysis across many medical sites | Compatible with several medical image modalities |

| Fed-BioMed [95] | Open-source | Privacy-preserving deep learning platform | Python, integrates with TensorFlow and PyTorch | Robust in various settings | Used in medical federated learning projects, especially for tumor segmentation and analysis |

| TFF [96] | Open-source | Google pioneered general-purpose federated learning | Python, combined with TensorFlow | Well-performing application interface | General federated learning research, particularly effective in healthcare settings |

| OBiBa [56] | Open-source | Statistical data analysis tool | R & DataSHIELD MICA Agate | Used for epidemiological studies | Supports biomedicine, public health, and social science research |

| DataSHIELD [56] | Open-source | Analytical infrastructure | Web App Onyx Opal | Manages users, publishes, and analyzes data | Used in public health and social science research, facilitating secure data management |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).