Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

13 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- Increasing the magnitude of the proposed risk reduction will lead to respondents being, on average, willing to pay a progressively lower amount for each additional percentage point of risk reduction.

- For subgroups with lower levels of cognitive bias, the effect of disproportionate sensitivity in willingness to pay for each additional percentage point reduction in mortality risk will be less pronounced compared to subgroups with higher levels of cognitive bias. Estimating the function that characterizes the declining willingness to pay, adjusted for cognitive biases, will yield more accurate estimates of the value of life.

- Estimates of the impact of basic socioeconomic and demographic characteristics on willingness to pay (e.g., gender, age, education, income, marital status) will be biased in models that do not employ quasi-experimental methods for causal inference, particularly the instrumental variable method.

Literature Review

Methods and Data

Study Design

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- ☐ Yes, I am 18 years old and agree(s) to participate in the survey

- ☐ No, I do not agree to take the survey or I am under 18 years of age.

- ☐ I have never lived in a seaport city/area

- ☐ I have lived in a port city/area

- ☐ I live in a port city/area

- ☐ I visit port cities (holiday, business trip)

- ☐ Yes, they do now

- ☐ Yes, used to live in the past

- ☐ No

- ☐ Less than 5 km

- ☐ From 5 to 10 km

- ☐ 10 to 50 km

- ☐ 50 to 100 km

- ☐ More than 100

- ☐ Less than 5 km

- ☐ 5 to 10 km

- ☐ 10 to 50 km

- ☐ 50 to 100 km

- ☐ More than 100

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

- ☐ 1-3 years

- ☐ 3-5 years

- ☐ 6 - 10 years

- ☐ 11 - 15 years

- ☐ More than 15 years

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

- In the FIRST region

- In the second region

- The probabilities are the same

- 10 cases per 1,000,000 people

- 10 cases per 100,000 people

- 2 deaths per 1,000 people

- 200 deaths per 100,000 people

- All options are correct

- -

- cardiovascular diseases (coronary heart disease, stroke);

- -

- respiratory diseases (bronchitis, COPD, pneumonia);

- -

- oncological diseases (lung cancer).

- -

- PM10 particles penetrate into the lungs and, once deposited, cause inflammation, irritation and damage to the mucous membranes of the respiratory tract.

- -

-

PM2.5 particles are smaller and more dangerous particles. They penetrate through lung tissue into the bloodstream, leading to:

- ○

- to chronic vascular inflammation, which raises blood pressure and, increases the risk of stroke.

- ○

- long-term inflammation of the lungs and other organs creates conditions for the development of cancerous changes.

- -

- total mortality by 4%,

- -

- cardiopulmonary mortality by 6%,

- -

- lung cancer mortality by 8%,

- -

- mortality from respiratory diseases by 0.58%

- -

- hospitalization rate by 8%.

- -

-

1 place in the mortality structure is occupied by: diseases of the circulatory system (556.7 per 100 thousand population), of which:

- ○

- ischemic heart disease - 297.9 per 100 thousand people

- ○

- strokes - 75.2 per 100 thousand people

- -

-

2nd place: neoplasms (197 per 100 thousand people), including:

- ○

- Malignant neoplasms of trachea, bronchi, lung (17.6%) - the most common oncological disease.

- -

- 3rd place - respiratory diseases (53 per 100 thousand people).

- -

- ships;

- -

- coal terminals;

- -

- railway and road transport;

- -

- transported cargo.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Allegations | Totally disagree. | I don't agree | Somewhere in the middle | I agree | Totally agree |

| Reducing air pollution is the responsibility of the Government. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| The ports are the ones who should bear the costs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Let those who live near the port pay. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| My income is too low to afford it | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I don't believe the project will reduce air pollution | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| There are many other more serious sources of pollution than seaports | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I already pay enough taxes to implement any government decisions | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I think the money will be used for other purposes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I'd rather pay for a more important project | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I believe that the health effects of pollution are overestimated | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I believe that the monthly amount offered is too much to be paid on a monthly basis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I believe the proposed monthly amount is too small (it may not be enough for such a large-scale project) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

- ☐ I believe that reducing the risk of death from pollution-related diseases is important for everyone

- ☐ I want to reduce health risks for my loved ones.

- ☐ Reducing air pollution will make the environment safer for living.

- ☐ This project will help save many lives.

- ☐ It is important for me to know that I am contributing to improving the quality of life and public health.

- -

- 0 represents the worst state of health you can imagine,

- -

- 10 represents the best state of health you can imagine.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

- ☐ Several times a month

- ☐ Once a month

- ☐ 2-3 times during the year

- ☐ Once during the year

- ☐ Less than once a year

- ☐ Heart disease (ischemic heart disease (angina pectoris, myocardial infarction))

- ☐ Lung disease, bronchial disease (bronchial asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma)

- ☐ Liver diseases

- ☐ Kidney diseases

- ☐ Endocrine system diseases, diabetes or high blood sugar

- ☐ Hypertension, high blood pressure

- ☐ Cerebrovascular disease (including stroke)

- ☐ Diseases of the ENT organs (maxillary sinusitis, otitis media, tonsillitis, etc.)

- ☐ Skin diseases

- ☐ Oncological diseases

- ☐ Other chronic diseases

- ☐ up to 1000 roubles

- ☐ 1000 - 5000 roubles

- ☐ 5000 - 10 000 roubles

- ☐ 10 000 - 20 000 roubles

- ☐ I smoke cigarettes (including cigarillos, cigarettes, cigarettes, etc.) every day.

- ☐ I use e-cigarettes, vape or other tobacco heating systems on a daily basis.

- ☐ I smoke hookah regularly (but not daily).

- ☐ I have never smoked.

- ☐ I have quit smoking

- ☐ 1-5

- ☐ 6-10

- ☐ 11-15

- ☐ 16-20

- ☐ More than 20

- ☐ Less than 100 rubles

- ☐ 100-120 rubles

- ☐ 120-150 rubles

- ☐ 150-180 rubles

- ☐ 180-200 rubles

- ☐ More than 200 rubles

- ☐ Never

- ☐ About once a month or less often

- ☐ 2-4 times a month

- ☐ 2-3 times a week

- ☐ 4 times a week or more often

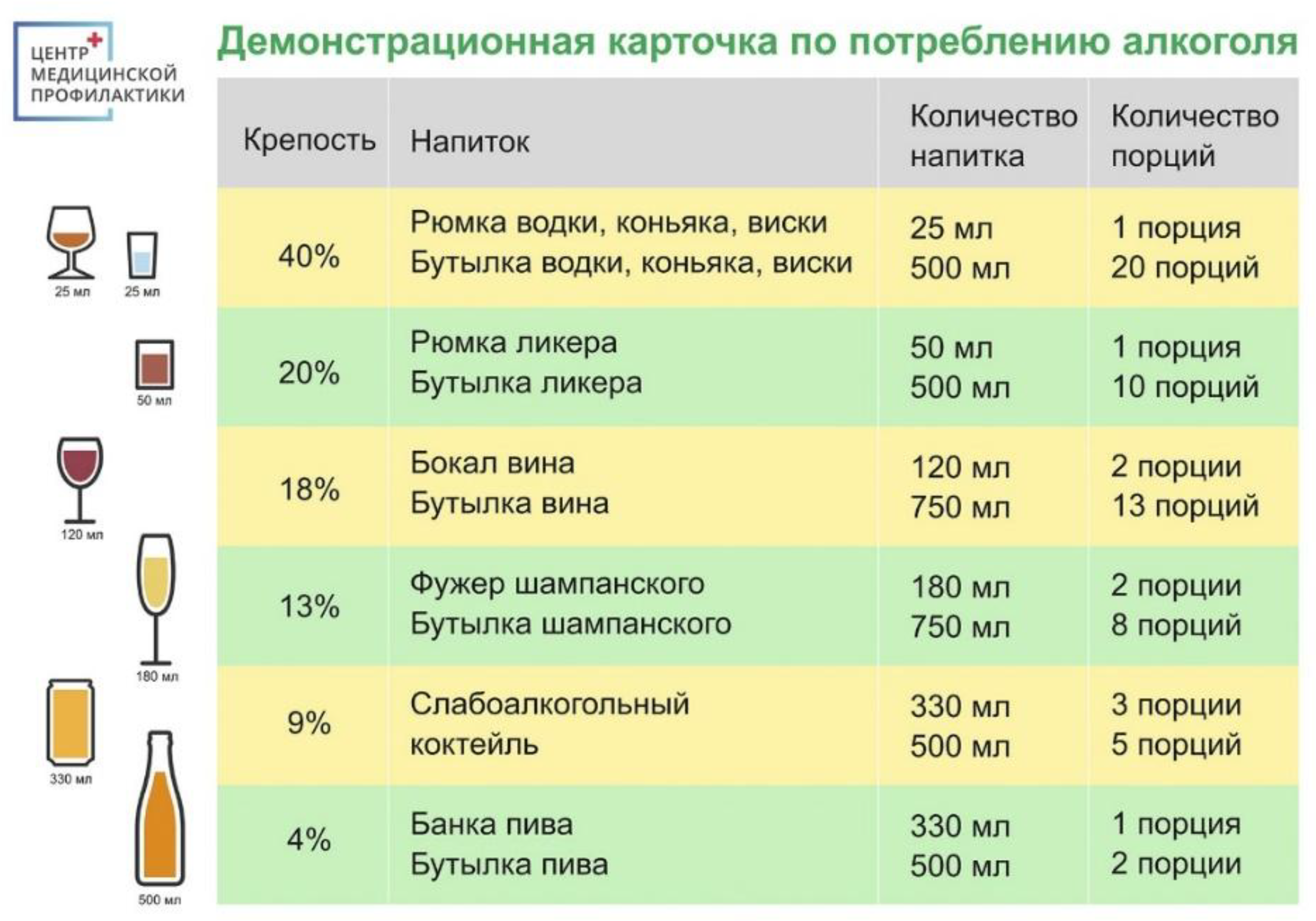

| 0 | 1-2 | 3-4 | 5-6 | 7-9 | 10+ | |

| A shot of vodka, cognac, whiskey average number of servings at a time |

||||||

| A shot of liqueur average number of servings per time |

||||||

| Glass of wine average number of servings per meal |

||||||

| A flute of champagne average number of servings per time |

||||||

| Can of beer average number of servings per time |

||||||

| bottle of cider, bottle of mead average number of servings at a time |

||||||

| Other (specify) average number of servings at a time |

- ☐ Never

- ☐ Less than once a month

- ☐ Once a month

- ☐ Once a week

- ☐ Every day and almost every day

- 9 years of school

- 11 years of school

- Vocational education

- Incomplete higher education

- Higher education (Bachelor / Specialist degree)

- Higher education (Master's degree)

- Postgraduate education (PhD / Doctorate)

- Other (please specify) ____

- 9 years of school

- 11 years of school

- Vocational education

- Incomplete higher education

- Higher education (Bachelor / Specialist degree)

- Higher education (Master's degree)

- Postgraduate education (PhD / Doctorate)

- Other (please specify) ____

- 9 years of school

- 11 years of school

- Vocational education

- Incomplete higher education

- Higher education (Bachelor / Specialist degree)

- Higher education (Master's degree)

- Postgraduate education (PhD / Doctorate)

- Other (please specify) ____

- ☐ I am an only child

- ☐ One brother/sister

- ☐ Two brothers/sisters

- ☐ Three brothers/sisters

- ☐ Four brothers/sisters

- ☐ Five or more brothers/sisters

- ☐ Never married

- ☐ Living in an unregistered marriage (cohabitation)

- ☐ Married in a registered marriage

- ☐ Divorced

- ☐ Widow/widower

- ☐ No children

- ☐ One child

- ☐ Two children

- ☐ Three children

- ☐ Four children

- ☐ Five children

- ☐ Other ____

- ☐ One person

- ☐ Two people

- ☐ Three people

- ☐ Four people

- ☐ Five people

- ☐ Six people

- ☐ Other

- ☐ Orthodoxy

- ☐ Muslim

- ☐ No religion

- ☐ Other religion

- ☐ You are a believer; you are more likely to be a believer than a non-believer

- ☐ You are a non-believer rather than a believer

- ☐ You are a non-believer

- ☐ You are an atheist

- ☐ Working

- ☐ Entrepreneur

- ☐ Not working

- ☐ Retired

- ☐ Yes

- ☐ No

- ☐ Working in a permanent job, indoors or outdoors,

- ☐ Working from home (telecommuting), but not online

- ☐ Working remotely from home or another location

- ☐ Working away with accommodation, shift work

- ☐ Working without a fixed location, travelling or moving around

- ☐ Light, food industry

- ☐ Civil engineering

- ☐ Defense industry

- ☐ Oil and gas industry

- ☐ Other sectors of heavy industry

- ☐ Construction

- ☐ Transport, communications

- ☐ Agriculture

- ☐ Government agencies

- ☐ Education

- ☐ Science, culture

- ☐ Health care

- ☐ Army, Ministry of Internal Affairs, security bodies

- ☐ Trade, consumer services

- ☐ Finance and insurance

- ☐ Energy industry

- ☐ Housing and utilities sector

- ☐ Real Estate Operations

- ☐ Information and communication technologies

- ☐ Other____

- ☐ Less than 40 hours

- ☐ 40 to 45 hours

- ☐ 46 to 52 hours

- ☐ More than 52 hours

- ☐ get 100 rubles guaranteed

- ☐ get a lottery ticket with which you can win 200 rubles with a probability of 50% or 0 rubles.

- ☐ to lose 100 rubles guaranteed

- ☐ with a 50% chance of losing nothing or with a 50% chance of losing 200 rubles.

References

- Abdallah, N. M. , et al. (2016). Analysis of accidents cost in Egypt using the willingness-to-pay method. International Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering, 5(1), 10–18.

- Alolayan, M. A. , Evans, J. S., & Hammitt, J. K. (2017). Valuing mortality risk in Kuwait: Stated-preference with a new consistency test. Environmental and Resource Economics, 66, 629–646.

- Arrow, K., Solow, R., Portney, P. R., Leamer, E. E., Radner, R., & Schuman, H. (1993). Report of the NOAA Panel on Contingent Valuation. Federal Register, 58(10), 4601–4614.

- Broughel, J. , & Viscusi, W. K. (2017). Death by regulation: How regulations can increase mortality risk.

- Corso, P. S. , Hammitt, J. K., & Graham, J. D. (2001). Valuing mortality-risk reduction: Using visual aids to improve the validity of contingent valuation. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 23, 165–184.

- Ducruet, C. , et al. (2024). Ports and their influence on local air pollution and public health: A global analysis. Science of the Total Environment, 915, 170099.

- Ghanem, S. , Ferrini, S., & Di Maria, C. (2023). Air pollution and willingness to pay for health risk reductions in Egypt: A contingent valuation survey of Greater Cairo and Alexandria households. World Development, 172, 106373.

- Hammitt, J. K. , & Graham, J. D. (1999). Willingness to pay for health protection: Inadequate sensitivity to probability? Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 18, 33–62.

- Hammitt, J. K. , & Herrera-Araujo, D. (2018). Peeling back the onion: Using latent class analysis to uncover heterogeneous responses to stated preference surveys. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 87, 165–189.

- Hammitt, J. K. , Liu, J.-T., & KLin, W.-C. (2000). Sensitivity of willingness to pay to the magnitude of risk reduction: A Taiwan–United States comparison. Journal of Risk Research, 3(4), 305–320. [CrossRef]

- Hanemann, M. , Loomis, J., & Kanninen, B. (1991). Statistical efficiency of double-bounded dichotomous choice contingent valuation. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 73(4), 1255–1263. [CrossRef]

- Keller, E. , et al. (2021). How much is a human life worth? A systematic review. Value in Health, 24(10), 1531–1541.

- Krupnick, A. (2007). Mortality-risk valuation and age: Stated preference evidence. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy.

- Leiter, A. M. , & Pruckner, G. J. (2009). Proportionality of willingness to pay to small changes in risk: The impact of attitudinal factors in scope tests. Environmental and Resource Economics, 42, 169–186.

- Lopez-Feldman, A. (2012). Introduction to contingent valuation using Stata.

- Sajise, A. J. , et al. (2021). Contingent valuation of nonmarket benefits in project economic analysis: A guide to good practice. Asian Development Bank.

- Wang, H. , & He, J. (2010). The value of statistical life: A contingent investigation in China. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (No. 5421).

- Wang, H. , & Mullahy, J. (2006). Willingness to pay for reducing fatal risk by improving air quality: A contingent valuation study in Chongqing, China. Science of the Total Environment, 367(1), 50–57.

- Yeung, R. Y. T. , Smith, R. D., & McGhee, S. M. (2003). Willingness to pay and size of health benefit: An integrated model to test for ‘sensitivity to scale’. Health Economics, 12(9), 791–796.

| Initial risk (per 100,000) | Reduction (percentage points) | New risk (deaths per 100,000) | Reduction in absolute terms (number of deaths per 100,000 people) |

| 1192 | 25 | 1167 | 25 |

| 1192 | 50 | 1142 | 50 |

| 1192 | 100 | 1092 | 100 |

| 1192 | 150 | 1042 | 150 |

| 1192 | 200 | 992 | 200 |

| Questionnaire block | Purpose |

| The experience of living in a seaport city | 1. Stratification of respondents by place of residence: those living in a port city vs. those not living in a port city. 2. assessment of quality of life; 3. assessment of the impact of polluted air on health. |

| Part 2. Game questions | Identification of respondents who do not understand probabilistic changes (cognitive distortion effect) |

| Part 3. Scenario for assessing willingness to pay for reducing the risk of death from air pollution and attitudes toward the proposed scenario |

Introduction to the problem context: Familiarization with statistics to inform respondents about the issue of air pollution and its impact on health. Random distribution of respondents into 5 groups based on the level of risk reduction (see Table 1). Determination of willingness-to-pay estimates. Identification of reasons for supporting the scenario as well as protest responses. |

| Part 4. Questions about health status and harmful habits |

Identification of respondents who are sensitive and non-sensitive to health risks |

| Part 5. Socio-demographic characteristics |

Population grouping by:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).