Submitted:

12 February 2025

Posted:

13 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Substrate Sampling and Preparation

Determination of Zn , Fe, Cd and Pb in Substrate

Button Mushroom Sampling

Determination of Zn , Fe, Cd and Pb in Button Mushrooms

ICP-OES Analysis

Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mineral Elements in Substrate

3.2. Mineral Elements in Button Mushroom Fruits

3.3. The Accumulation Coefficients of Essential and Toxic Heavy Metals in Button Mushroom Fruits

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martins, R. Pardo, R.A.R. Bonaventura. Cadmium(II) and zinc(II) adsorption by the aquatic moss Fontinalis antipyretica: effect of temperature, pH and water hardness. Water research. 2004, Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 693–699. [CrossRef]

- Kalač, P.; Svoboda, A. A review of trace element concentrations in edible mushrooms. Food. Chem. 2000, 69, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J., Garcia, M.A, Perez-Lopez, M., Melgar, M.J. The concentrations and bioconcentration factors of cooper and zinc in edible mushrooms. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2003, 44, 180–188. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soylak, M., Saracoglu, M., Tűzen, Mendil, D. Determination of trace metals in mushroom samples from Kayseri, Turkey, Food. Chem. 2005, 92, 649–652. [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, L. Havličkova, B. Kalač, P. Contents of cadmium, mercury and lead in edible mushrooms growing in a historical silver-mining area. Food Chem 2006, 96, 580–585. [CrossRef]

- Cocchi, L., Vescovi, L., Petrini, L.E., Petrini, O. Heavy metals in edible mushrooms in Italy, Food Chem. 2006, 98, 277–284.

- Array, S., Tomas, J., Hauptvogl, M., Kopernicka, M., Kovačik, A., Bajčan, D., Contamination of wild -grown edible mushrooms by heavy metals in a former mercury-mining area. J. Environ Sci Health B. 2014, 49, 815–827. [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, J. S., Mitić, V. D., Stankov-Jovanović, M. V., Dimitrijević, M. V., Nikolić-Mandić, S. D. Elemental compostition of wild edible mushroos from Serbia. Analytical letters. 2015, 48, 2107–2121. [CrossRef]

- Tel- Cayan, G., Ullh, Z., Ozurk, M. Yabanli, M., Aydin, F., Duru, M.E. Heavy metals, trace and major elements in 16 wild mushroom species determined by ICP-ms. Atomic Spectroscpy. 2018, 39, 29–37.

- Tűrkmen, M., Budur, D. Heavy metal contamination in edible wild mushroom species from Turkey’s Black Sea region. Food Chemistry. 2018, 254, 256–259. [CrossRef]

- Bahadori, M. B., Sarikurcku, C., Yalcin, O. U., Cengiz, M., Gungor, H. Metal concentration, phenolics profiling and antioxidant activity of two wild edible Melanoleuca mushrooms (M. cognata and M. stridula). Michrocemical Journal. 2019, 150.

- Yildiz, S., Gurgen, A., Cevik, U. Accumulation of metals in some wild and cultivated mushroom species. Sigma Journal of Engineering and Natural Sciences. 2019, 37, 1371–1380.

- Tsegay, M. B., Asgedom, A. G., Belay, M. H. Content of major, minor and toxic elements of different edible mushrooms grown in Mekelle, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Cogent Food and Agriculture. 2019, 5. [CrossRef]

- Jarup, L., Berglund, M., Elinder, C.G., Nordberg, G., Vahter, M. Health effects of cadmium exposure – a review of the literature and risk estimate. Scand J Work“, Environ Health. 1998, Vol. 24 (Suppl 1), pp. 1–51.

- Augustsson, A., Uddh-Söderberg, T., Filipsson, M., Helmfrid, I., Berglund, M., Karlsson, A., Alriksson, S. Challenges in assessing the health risks of consuming vegetables in metal-contaminated environments. Environment International. 2018, Vol. 113, 269-280. [CrossRef]

- Khonyongwa, O., Kumar, S., Jha, A.K., Jain, M.K. Air pollution impact on human health and its management. A review. Macromolecular symposia. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Garcia M.G., Alonso J., Melgar M.J. Lead in edible mushrooms; levels and bioaccumu-lation factors. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009;167:777–783. [CrossRef]

- Mrinal, Singh, S. Heavy metal impacts on biology and their pollutants. International Journal of health advancement and clinical research. 2023, 1(3); 12-20.

- Xu, H., Song, G., Yang, Z. Effects of heavy metal on production of thiol compounds and antioxidant enzymes in Agaricus bisporus“. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2011, Vol. 74, No. 6, pp. 1685–1692.

- Dunkwal, V., Jad, S., Singh, S. Psyhico-chemical properties and sensory evaluation of Pleurotus sajor caju powder as influenced by pretreamenst and drying methods. British Food Journal, 2007, Vol. 109, pp. 749–759.

- Liu, S., Yao, F., Shi, M., Wang, H., Guo, J. Pollution level and risk assessment of lead, cadmium, mercury, and arsenic in edible mushroom from Jilin Province, China. Journal of food science. 2021, Vol. 86., Issue 8, 3374-3383. [CrossRef]

- Kirkham, M.B. Cadmium in plants on polluted soils: Effects of soil factors hyperaccumulation and amendments. Science Direct. 2006, Vol. 137, pp. 19–32.

- Pandey, M., Gowda, N.K.S., Satisha, G.C., Azeez, S., Chandrashekara, C. Zamil, M. Roy, T. Studies on bioavailability of iron from iron fortified commercial edible mushroom Hypsizygus ulmarius and standardization of delivery system for human nutrition. J. Horti. Sci. 2020, Vol. 15(2), 197-206:2020.

- Schroederm, H. A., Nason. A. P., Tipton I. H., Balassap, J. Essential trace metal sin man: Zinc Relation to environmental cadmium. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1967, Vol. 20, pp. 179–210.

- Fawole, O.A. and Opara, U.L. Composition of trace and major minerals in different parts of pomegranate (Punica granatum) fruit cultivars. British Food Journal. 2012, Vol. 114 No. 11, pp. 1518–1532.

- Ergönül, P.G., Akata, I., Kayloncu, F., Ergönül, B. Fatty acid compositions of six wild edible mushroom species. The scientific World Journal, 2013, Vol. 2013, pp. 1–4.

- Guizani, N., Rahman, M. S., Klibi, M., Al-Rawahi, A., Bornaz, S. Thermal characteristic of Agaricus bisporus mushroom: freezing point, glass ransition, and maximal-freeze-concentration condition. International Food Research Journal, 2013, Vol. 20, pp. 1945–1952.

- Hoed-van den Hill, E.F., Von Asselt, E.D. Chemical hazards in the mushroom supply chain. Wageningen University and research. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Fermor, T. R., Wood, D. A. Degradation of Bacteria by Agaricus bisporus and Other Fungi. Journal of General Microbiology. 1981, Vol. 126, pp. 377–387.

- Sonnenberg, A.S.M., Baars, J.J.P., Straatsma, G., Hendrickx, P.M., Blok, C. Feeding growing button mushrooms. The role of substrate mycellium to feed the first two flushes. PLOS ONE. 2022, 17(7):e02270633. [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, J., Švec, K., Kalihova, D., Tlustoš, P., Szakova, J. Translocation of mercury from substrate to fruit bodies of Panellus stipticus, Psylocybe cubensis, Schizophyllum commune and Stropharia rugosoannulata on oat flakes. Exotoxicology and Environmental safety. 2016, Vol. 125, 184-189.

- Topbas, M.T., Brohi, R.A., Karaman, M.R. Environmental PollutioN. Environment Ministry Pub. Ankara-Turkey. 1998.

- Chen, L., Zhou, W., Luo, L., Li, Y. Chen, Z. et al. Short-term responses of soil nutrients, heavy metals and microbial community to partial substitution of chemical fertilizer with spent mushroom substrate (SMS). Science of The Total Environment. 2022, Vol. 844, 157064. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Yu, J., Lu, X., Yang, M., Liu, Y., Sun, H., Ying, N., Lin, G. Wu, C., Tang, J. Tracing potentially toxic elements in button mushroom cultivation and environmental implications: Insights via stable lead (Pb) isotope analysis. Journal of Cleaner production. 2024, Vol. 479, 144079.

- Tuzen, M., Ozdemir, M., Demirbas, A. Heavy metal bioaccumulation by cultivated Agaricus bisporus from artificially enriched substrates. Zeitschrift für Lebensmitteluntersuchung und Forshung A. 1998, Vol. 206, pp. 417–419.

- Li, X., Wong, M., Wen, B., Zhang, Q., Chen, J., Li, X., An, Y. Reed-mushroom-fertilizer ecological agriculture in wetlands. Harvesting reed to cultivate mushroom and returning waste substrates to restore soline-alkaline marshes. Science of the total Environment. 2023, Vol. 878, 162 987.

- Bernal, M.P., Paredes, C., Sanches_Monedero, M.A., Cegarra, J. Maturity and stability parameters of composts prepared with a wide range of organic wastes. Bioresource Technology. 1998, Vol.63, pp. 91–99. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.H., Lo, S.L. Chemical and spectroscopic analysis of organic matter transformations during composting pig manure. Environmental Pollution, 1999, Vol. 104, pp. 189–196. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N. Effect of low initial C/N ratio an aerobic composting of swine manure with rice straw. Bioresource Technology, 2007, Vol. 98, pp. 9–13.

- Thompson, W.H. Test Methods for the Examination of Composting and Compost. 2001. available at: http: //tmecc.org/cap/.

- Fidanza M.A., Sanford D.L., Beyer D.M. Aurentz D. Analysis of FRESH Mushroom Compost. HortTechnology, 2010, Vol. 20. No. 2, pp. 449–453.

- Commission Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 Setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs.

- Uddin, Y., Khan, M.N., Tania, M.A., Moonmoon, M., Ahmed, S. Production of Oyster mushrooms in different seasonal conditions of Bangladesh. Journal of scientific research. 2011, 3(1):161-167. [CrossRef]

- Haldimann, M., Bajo, C., Haller, T., Venner, T., Zimmerli, B. Contents of arsenic, lead, cadmium, mercury and selenium in cultivated mushrooms. Mitteil Gebiete Lebensmittelunters Hyg. 1995, Vol. 86, pp. 463–484.

- Angeles Garcia, M., Alonso, J. Melgar, M. J. Lead in edible mushrooms levels and bioaccumulation factors. Journal of hazardous materials. 2009, 167, 777–783. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, D.H., Lysek, G. Fungal biology: Understanding the fungal lifestyle. BIOS Scientific Publishers Ltd., Oxford, UK. 1996.

- Gast, C.H., Jansen, E., Bierling, J., Haanstra, L. Heavy metals in mushrooms and their relationship with soil characteristics. Chemosphere. 1998, Vol. 17, pp. 789–799. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.A., Alonso, J., Fernandez, M.I., Melgar, M.J. Lead content in edible wild mushrooms in Northwest Spain as indicator of environmental contamination. Archives Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 1998, Vol. 34, pp. 330–335. [CrossRef]

- Kalac, P., Burda, J., Staškova, I. Concentrations of lead, cadmium, mercury and copper in mushrooms in the vicinity of a lead smelter. Sci Total Environ. 1991, Vol. 105, pp. 109–119.

- Manzi, P., Aguzzi, A., Pizzoferato, L. Nutritional value of mushrooms widely consumed in Italy. Food chemistry. 2001, Vol. 73, pp. 321–325.

- Bucurica, A., Dulama, J. D., Radulescu, C., Banica, A. L., Stanescu, S. G. Heavy metals and associated risks of wild edible mushrooms consumption: Transfer factor, carcinogenic risk, and health risk index. Journal Fungi. 2024, 10(12),844. [CrossRef]

| Cycle vegetation | Substrate | pH (H2O) 1:10 | EC mS/cm 1:5 | DM % |

N % |

C % |

C/N | P % |

K % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Substrate A | 6.16 | 8.27 | 46.83 | 2.49 | 25.97 | 10.47 | 1.91 | 1.09 |

| II | Substrate A | 6.07 | 8.55 | 47.46 | 2.27 | 25.46 | 11.24 | 1.93 | 1.09 |

| III | Substrate A | 6.26 | 8.05 | 46.51 | 2.49 | 25.97 | 10.47 | 1.94 | 1.09 |

| IV | Substrate A | 6.25 | 8.06 | 46.51 | 2.25 | 24.23 | 10.74 | 1.92 | 1.09 |

| Average | Substrate A | 6.19 | 8.23 | 46.83 | 2.38 | 25.41 | 10.73 | 1.93 | 1.09 |

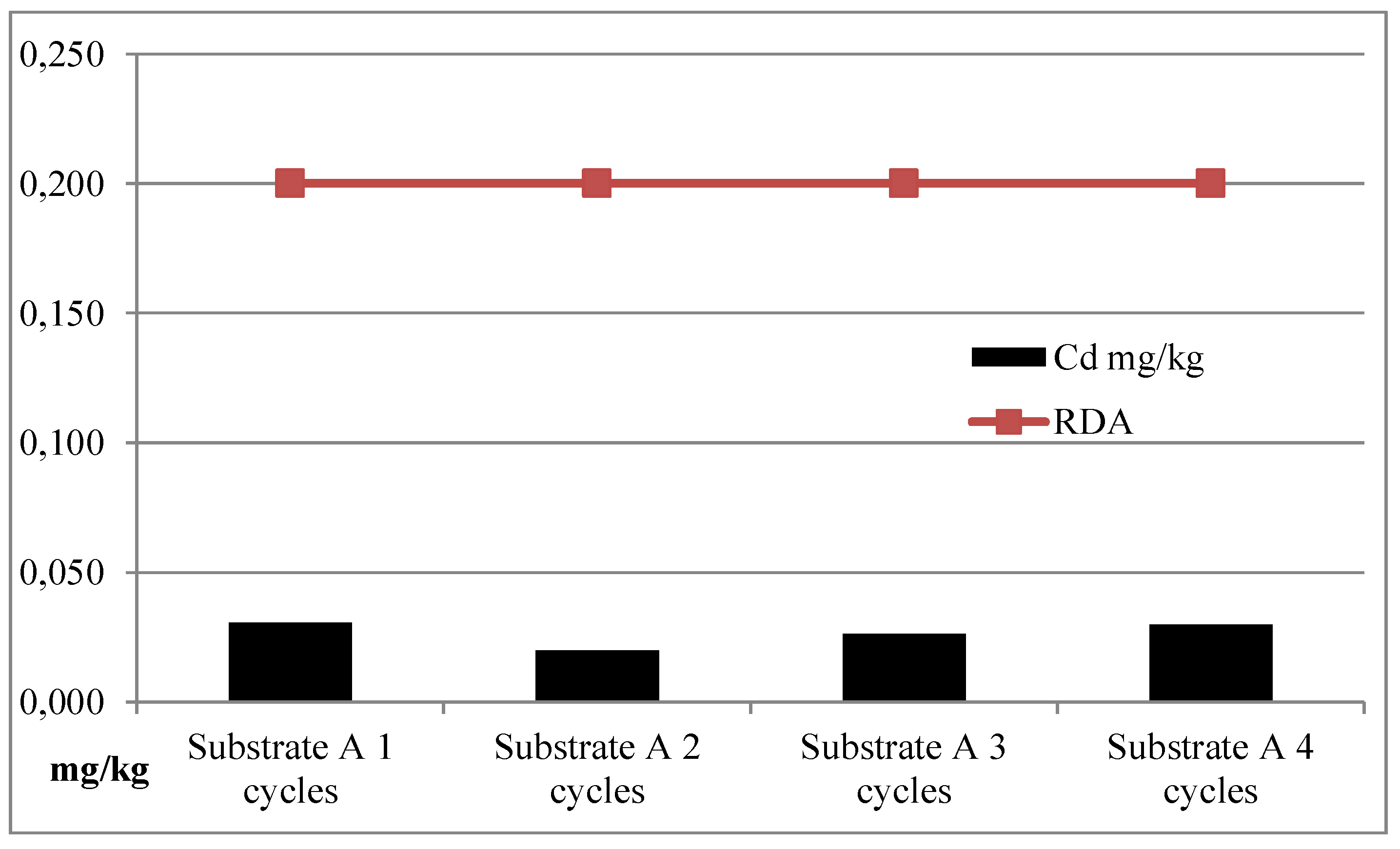

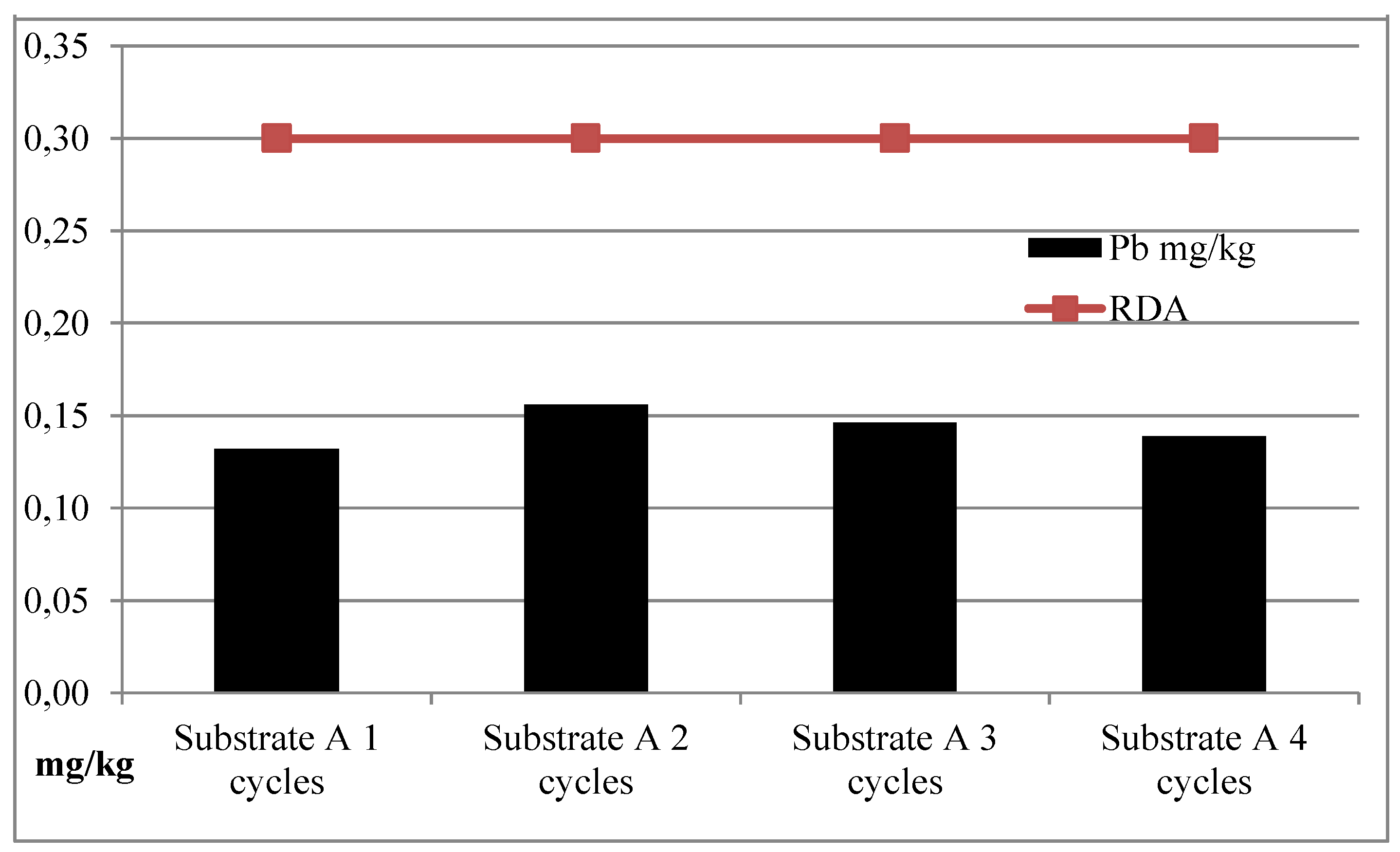

| Cycle vegetation | Substrate | Zn | Fe | Pb | Cd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Substrate A | 163.99 | 1596.21 | 0.97 | 0.15 |

| II | Substrate A | 155.20 | 2464.11 | 1.19 | 0.13 |

| III | Substrate A | 151.47 | 3362.16 | 2.26 | 0.15 |

| IV | Substrate A | 150.86 | 3361.49 | 2.26 | 0.15 |

| Average | Substrate A | 155.38 | 2695.99 | 1.67 | 0.14 |

| Cycle vegetation | Substrate | pH (H2O) 1:10 | EC mS/cm 1:5 | DM % |

N % |

C % |

C/N | P % |

K % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Substrate B | 5.96 | 8.03 | 42.07 | 2.32 | 29.81 | 12.84 | 1.69 | 1.01 |

| II | Substrate B | 6.09 | 9.18 | 41.97 | 2.30 | 25.61 | 11.11 | 1.73 | 1.03 |

| III | Substrate B | 6.21 | 7.29 | 43.27 | 2.32 | 29.81 | 12.84 | 1.75 | 1.04 |

| IV | Substrate B | 6.21 | 7.33 | 43.27 | 2.38 | 26.34 | 11.04 | 1.72 | 1.02 |

| Average | Substrate B | 6.12 | 7.96 | 42.64 | 2.33 | 27.89 | 11.96 | 1.72 | 1.03 |

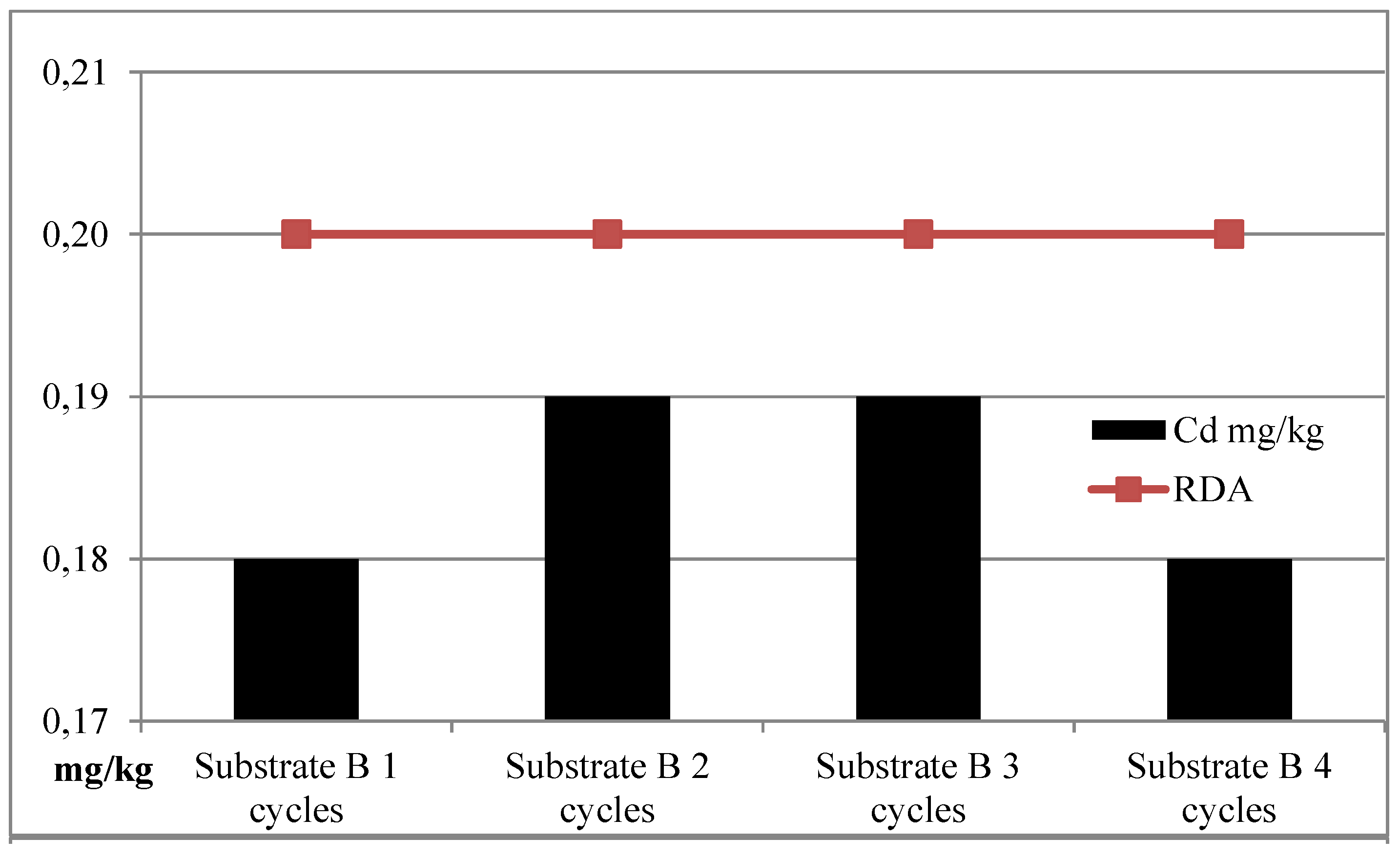

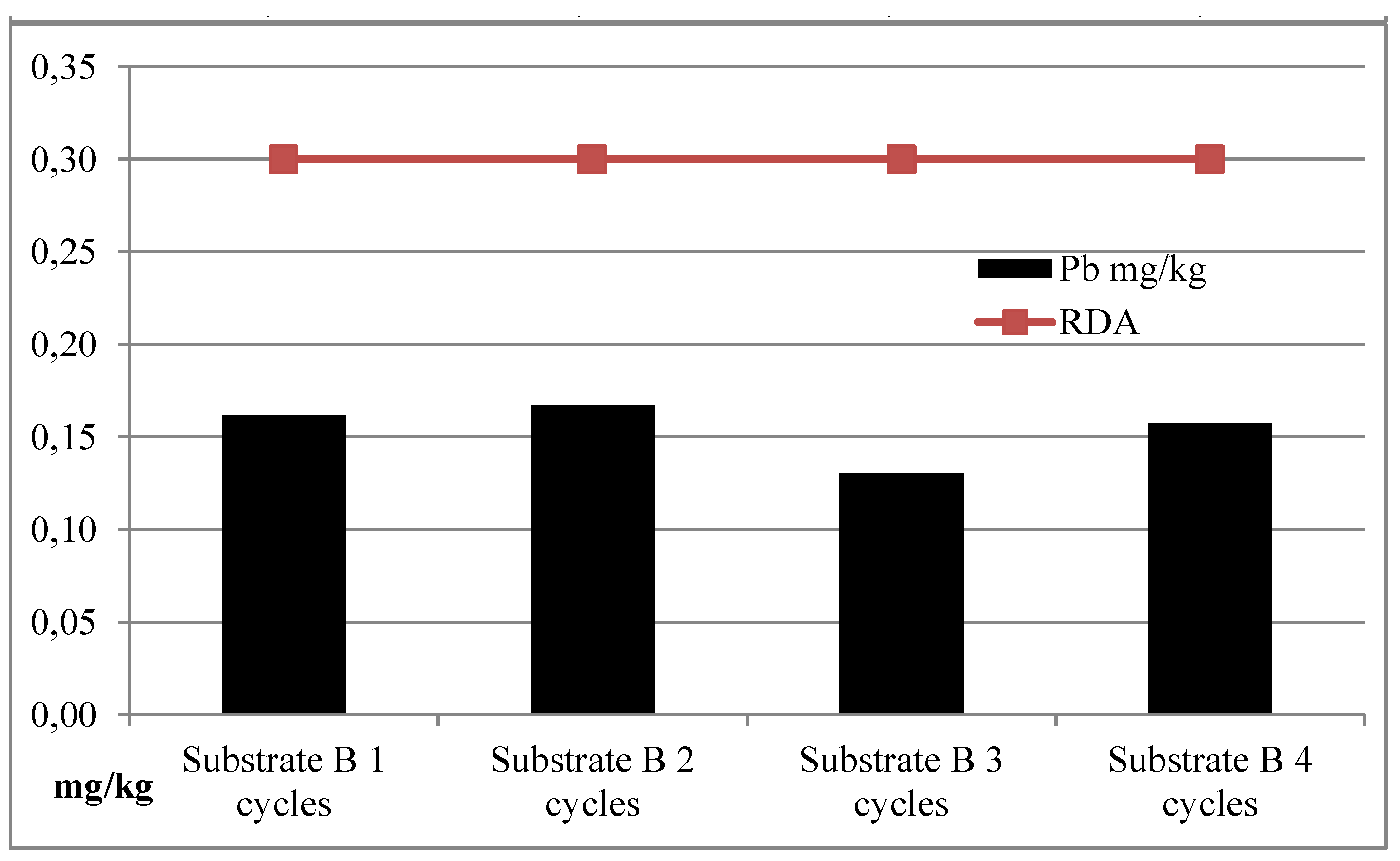

| Cycle vegetation | Substrate | Zn | Fe | Pb | Cd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Substrate B | 127.24 | 1438.23 | 2.66 | 0.22 |

| II | Substrate B | 105.61 | 1216.62 | 2.78 | 0.16 |

| III | Substrate B | 121.89 | 1701.86 | 3.09 | 0.21 |

| IV | Substrate B | 122.89 | 1702.53 | 3.06 | 0.23 |

| Average | Substrate B | 119.41 | 1514.81 | 2.90 | 0.21 |

|

Champignon fruit (picking stage) |

Fe (mg/kg) |

Zn (mg/kg) |

Pb (mg/kg) |

Cd (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate A initial | 84.41 c | 90.58 c | 0.04 d | 0.04 d |

| Substrate A middle | 101.98 b | 114.40 a | 0.16 c | 0.03 d |

| Substrate A end | 116.14 a | 116.11 a | 0.33 a | 0.04 d |

| Substrate B initial | 82.65 c | 82.05 d | 0.18 c | 0.48 a |

| Substrate B middle | 90.46 cb | 91.46 c | 0.24 bac | 0.21 b |

| Substrate B end | 90.77 cb | 103.65 b | 0.29 ba | 0.11 c |

| Average | 94.40 | 99.70 | 0.20 | 0.15 |

| Champignon fruit (picking stage) |

Fe (mg/kg) |

Zn (mg/kg) |

Pb (mg/kg) |

Cd (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate A initial | 84.10 cd | 88.58 c | 0.14 c | 0.04 c |

| Substrate A middle | 102.10 b | 115.51 a | 0.14 c | 0.03 c |

| Substrate A end | 123.14 a | 110.36 ba | 0.34 a | 0.03 c |

| Substrate B initial | 79.02 d | 79.42 c | 0.18 c | 0.49 a |

| Substrate B middle | 96.84 cb | 88.21 c | 0.23 bc | 0.21 b |

| Substrate B end | 90.95 cbd | 101.71 b | 0.33 ba | 0.15 b |

| Average | 96.02 | 97.30 | 0.45 | 0.16 |

| Champignon fruit (picking stage) |

Fe (mg/kg) |

Zn (mg/kg) |

Pb (mg/kg) |

Cd (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate A initial | 85.72 b | 88.45 c | 0.09 b | 0.04 c |

| Substrate A middle | 103.47 b | 112.94 a | 0.12 b | 0.03 c |

| Substrate A end | 140.53 a | 109.61 a | 0.37 a | 0.04 c |

| Substrate B initial | 81.96 b | 78.80 d | 0.15 b | 0.50 a |

| Substrate B middle | 95.28 b | 87.77 c | 0.19 ba | 0.20 b |

| Substrate B end | 94.89 b | 100.65 b | 0.24 ba | 0.15 b |

| Average | 100.30 | 96.37 | 0.19 | 0.16 |

| Champignon fruit (picking stage) |

Fe (mg/kg) |

Zn (mg/kg) |

Pb (mg/kg) |

Cd (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate A initial | 85.08 a | 91.57 c | 0.07 d | 0.04 dc |

| Substrate A middle | 103.56 a | 119.22 a | 0.15 dc | 0.03 d |

| Substrate A end | 149.16 a | 107.68 b | 0.32 a | 0.05 dc |

| Substrate B initial | 133.87 a | 78.17 d | 0.17 bc | 0.50 a |

| Substrate B middle | 94.34 a | 88.83 c | 0.26 ba | 0.22 b |

| Substrate B end | 91.29 a | 104.90 b | 0.26 ba | 0.09 c |

| Average | 109.55 | 98.39 | 0.20 | 0.15 |

| Heavy metals | Vegetation cycle substrate A |

Average | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | ||

| Accumulation coefficients | |||||

| Fe | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Zn | 0.61 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.66 |

| Pb | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| Cd | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0.30 |

| Heavy metals |

Vegetation cycle substrate B |

Average | |||

| I | II | III | IV | ||

| Accumulation coefficients | |||||

| Fe | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Zn | 0.70 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.78 |

| Pb | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Cd | 1.35 | 1.75 | 1.47 | 1.23 | 1.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).