1. Introduction

The effects of COVID-19 pandemic and the social distancing measures imposed during the lockdown period remain a topic of debate within the scientific community. The potential impact of the pandemic and the associated measures on the social and psycho-emotional development of children, particularly those of pre-school age, continues to attract significant research interest worldwide [

1].

The pre-school age is a critical period of neurodevelopment characterized by extreme sensitivity to environmental variations and a near-total dependence on parents [

2].During the COVID-19 pandemic, social isolation, school closures, disruption of daily routines-such as sleep and physical activities-, increase in passive screen time, and the parents’ distress due to the broader effects of the lockdowns, unsurprisingly appear to have affected young children’s emotion and behavior [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. In terms of cognitive and learning skills, the responsibility for fostering improvement during this sensitive phase of personal growth and societal instability fell largely on the children themselves and their families; “low-achievers” or those with less-educated parents appeared to have had visibly poorer outcomes [

8]. It is estimated that the stringent lockdown measures led to a reduction in educational attainment equivalent to between 0.3 and 1.1 years of schooling [

3]. Apparently, the children most affected by the lockdowns in regards to their pro-social and emotional functions were those with special needs or requiring therapies such as speech, cognitive-behavioral, or psychoeducational therapy, like those with neurodevelopment disorders. This could be attributed to both the nature of their conditions, which often involve difficulty with routine changes, and the disruption of their therapeutic plans.[

6,

8,

9,

10]Notably, emotional and behavioral issues were found to co-exist with language weaknesses [

8].

Against this background, our study aimed to investigate the influence of the COVID-19 restrictive measures on the language development of preschool-aged children based on Greek data focusing on two key areas: first, whether there were any observable differences in language development before, during and after the lifting of pandemic restrictions and secondly, whether any gender-related differences emerged in the findings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample and Ethics

This retrospective cohort study encompassed a total sample of 213 preschool-aged children, comprising 104 boys and 109 girls, with a mean age of 52 months (age range from 35 to 77 months). Prior to their enrollment, all children provided verbal consent and written informed consent was obtained from their legal caregivers. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [

11]. The sample was collected from urban and rural areas of western and central Macedonia, Greece, in the context of language disorder screening programs in schools conducted by speech and language therapists.

2.2. Language Development Assessment Process

For the assessment of language development of the participants, the specialists utilized the “AνOμιΛο4” test, a Greek culturally adapted and validated version of the French ERTL4 test, commonly used for early detection of speech and language issues in young children. It consists of questions focusing on testing children’s speech, language and voice mainly at the age of 3.6-4.9 years old and the results categorize the children into three language development profile groups; 1

st: Normal speech and language, 2

nd : Requiring follow-up, and 3

rd : Potential speech delays or disorders [

12,

13,

14].

Based on the analysis of the test results, our study sample was categorized according to the children’s language development profiles, with only the first profile defined as normal and both the second and third profiles classified as abnormal. Another classification of the sample was based on the timing of the evaluation concerning the enforcement of pandemic measures: before (2014-2019), during (2019-2020), and after (2020-2023) the COVID-19 pandemic.

As a secondary analysis of the study, the specialists measured the number of words and pseudowords-sequences of letters that resemble actual words but do not have meaning; they serve as indicators of typical language development-produced by the participants, as well as their expressive language skills. Participants who articulated more than 8 “Words and Pseudowords”, with an “Expression” score exceeding 5, were classified as normal; those who did not meet these criteria were categorized as abnormal [

15,

16].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The data were encoded with Microsoft Excel, which was also used to produce the charts of this research. Nominal variables are presented with relative and absolute frequencies, while scale variables with mean values and standard deviations (SDs). The distributions of the variables are presented with bar graphs and histograms. Comparisons of mean values between three or more groups were conducted using the parametric one-way ANOVA test and with an additional post-hoc analysis using the Bonferroni criterion. Furthermore, the Chi- Square test of independence was applied to investigate associations between nominal variables. The significance level for all tests was set to a = 0.05. All analyses were conducted through Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (SPSS v.25).

3. Results

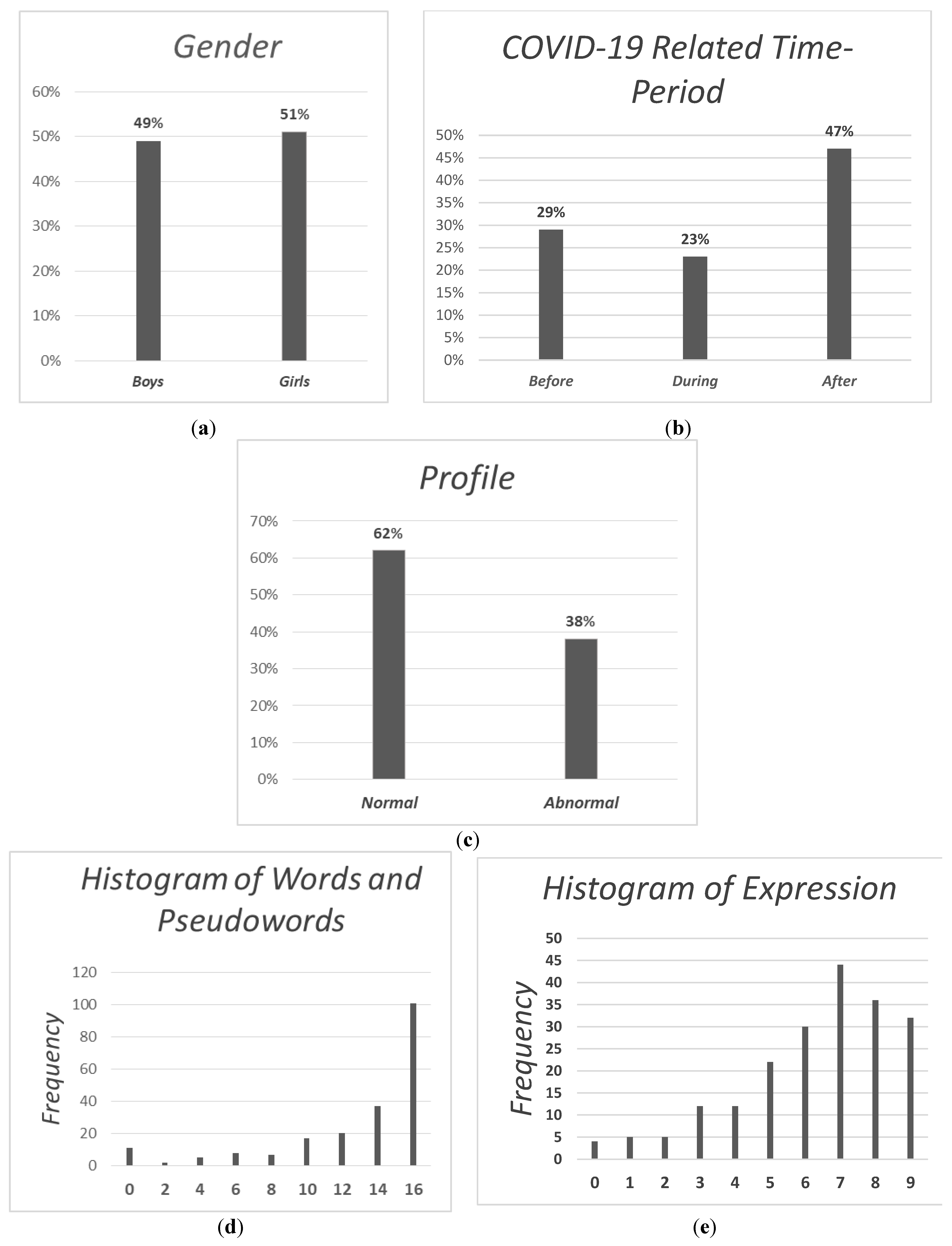

The descriptive data for this study are presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 1. The sample consists of 104 boys (48.8%) and 109 girls (51.2%), with a mean age of 53.9 months (SD = 10.2 months). Most of the test responses were collected after the COVID-19 era (47.4%), while the rest were collected before (29.1%) and during (23.5%) the COVID-19 pandemic. Of the children, most are categorized as Normal (61.7%) and approximately one in three as Abnormal (38.3%).

3.1. Main outcome: Correlation of Different Language Development Profiles with the COVID-19-Related Time-Period

Differences in Language Development Profile

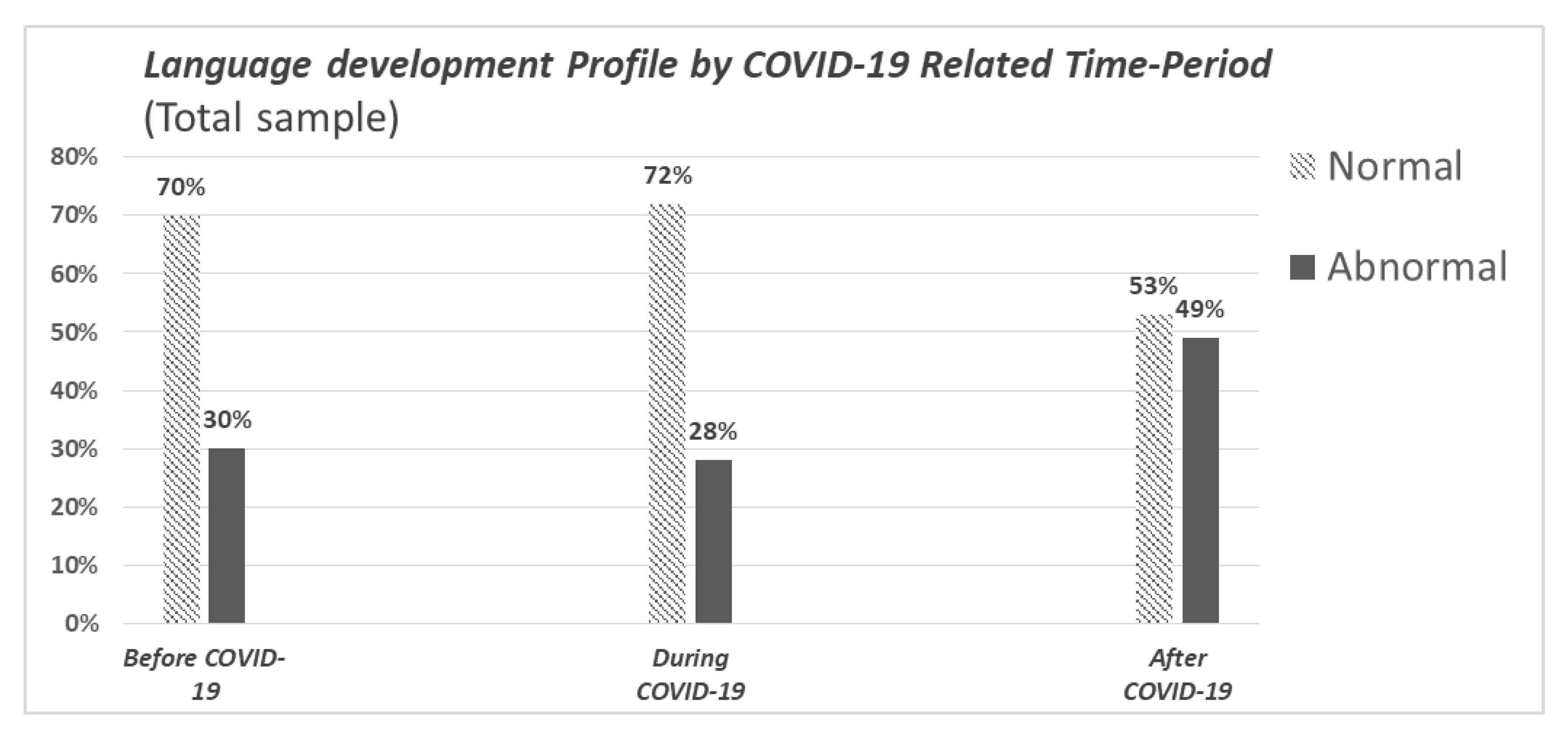

The distributions of children's language development profiles were tested among the three periods of time (pre-, during and post- COVID-19 pandemic) for the entire sample. The results showed a significant differentiation of the language development profiles at these different periods (χ²(2) = 6.654, p = 0.036). The proportion of children with an abnormal profile is higher after the pandemic, when compared to the periods before as well as during the pandemic (

Supplementary Table S1,

Figure 2).

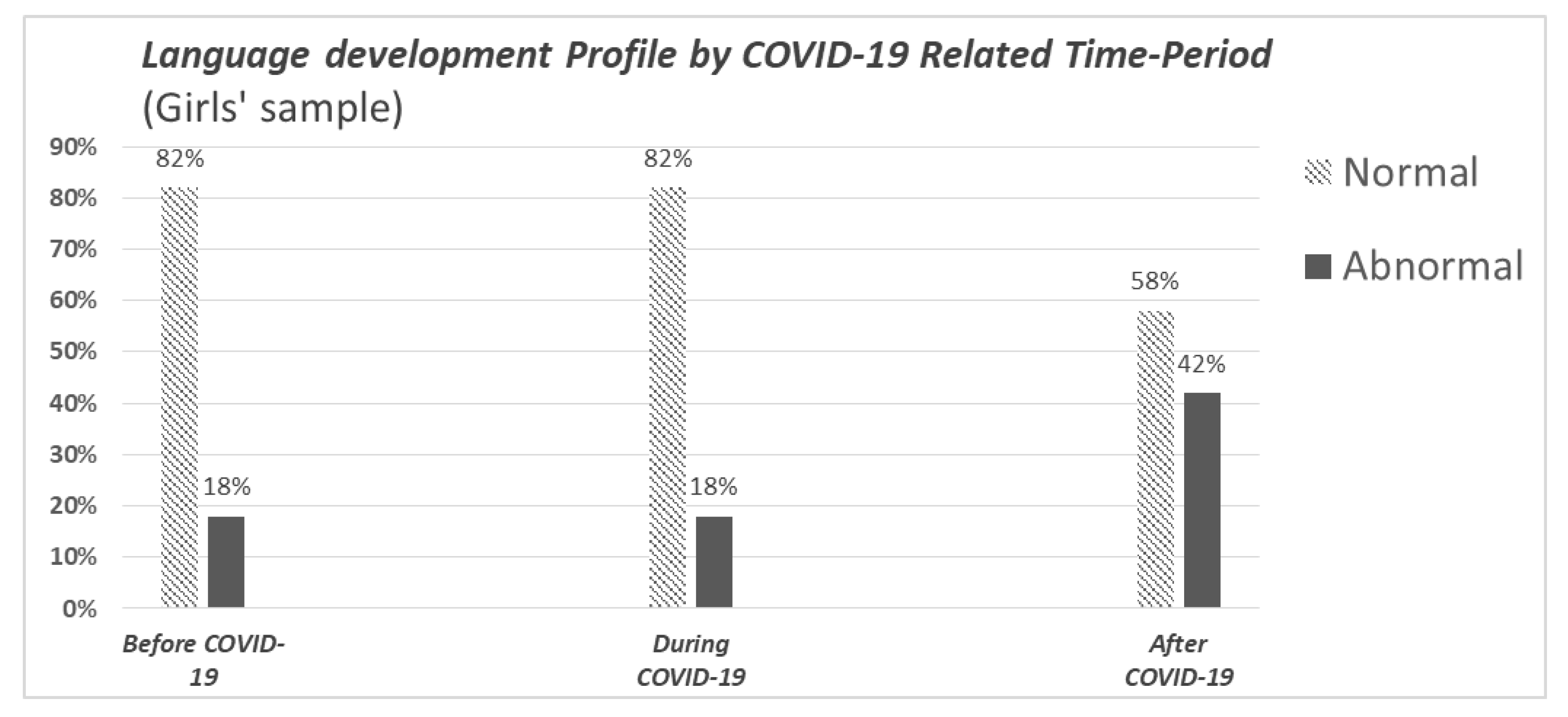

The above analysis was also performed separately between boys and girls as a sensitivity analysis. In the subgroup of boys, the chi-square test was not significant (p > 0.05). However, in the girls’ subgroup the language development profile was significantly associated with the period of measurement (χ²(2) = 7.120, p = 0.028). This analysis yielded that girls with an abnormal language development profile were found in a much higher proportion after the pandemic, compared to the before and during the pandemic proportions (

Figure 3).

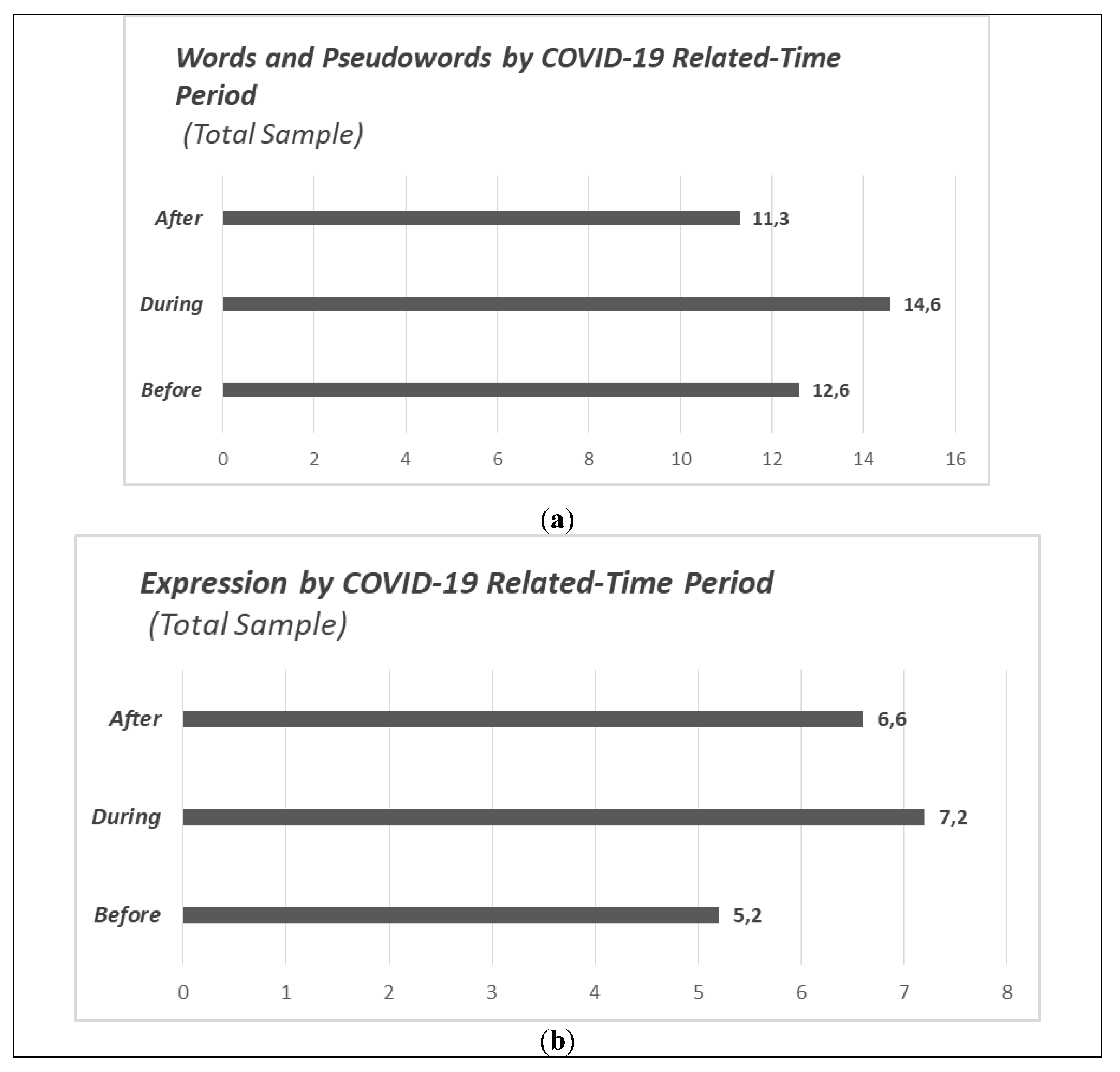

3.2. Secondary Outcome: Differences in Words/Pseudowords and Expression

Additionally, within the same context of assessing language development, it was examined whether the specific measurements in Words and Pseudowords, as well as in expression had differences between the three periods (). In the entire sample, the difference of Words and Pseudowords between the three periods was found to be significant (F(2.205) = 9.34, p < 0.001). The highest measurements were recorded during the pandemic (M = 14.6, SD=2.9), followed by before (M = 12.6, SD=3.5) and after (M = 11.3, SD=5.3) the pandemic. Post Hoc analysis showed that the significant differences were in the pairs of periods: During-Before (p = 0.044) and During-After (p<0.001).

The difference in expression measurements between the periods was also found to be significant (F(2.205) = 14.197, p < 0.001). Children measured during the pandemic had the highest mean expression value (M = 7.2, SD=1.9) s, followed by post-pandemic (M = 6.6, SD=2.3) and pre-pandemic measurements (M = 5.2, SD=2). Post Hoc testing yielded significant differences for both the During-Before (p < 0.001) and During-After (p < 0.001) pairs.

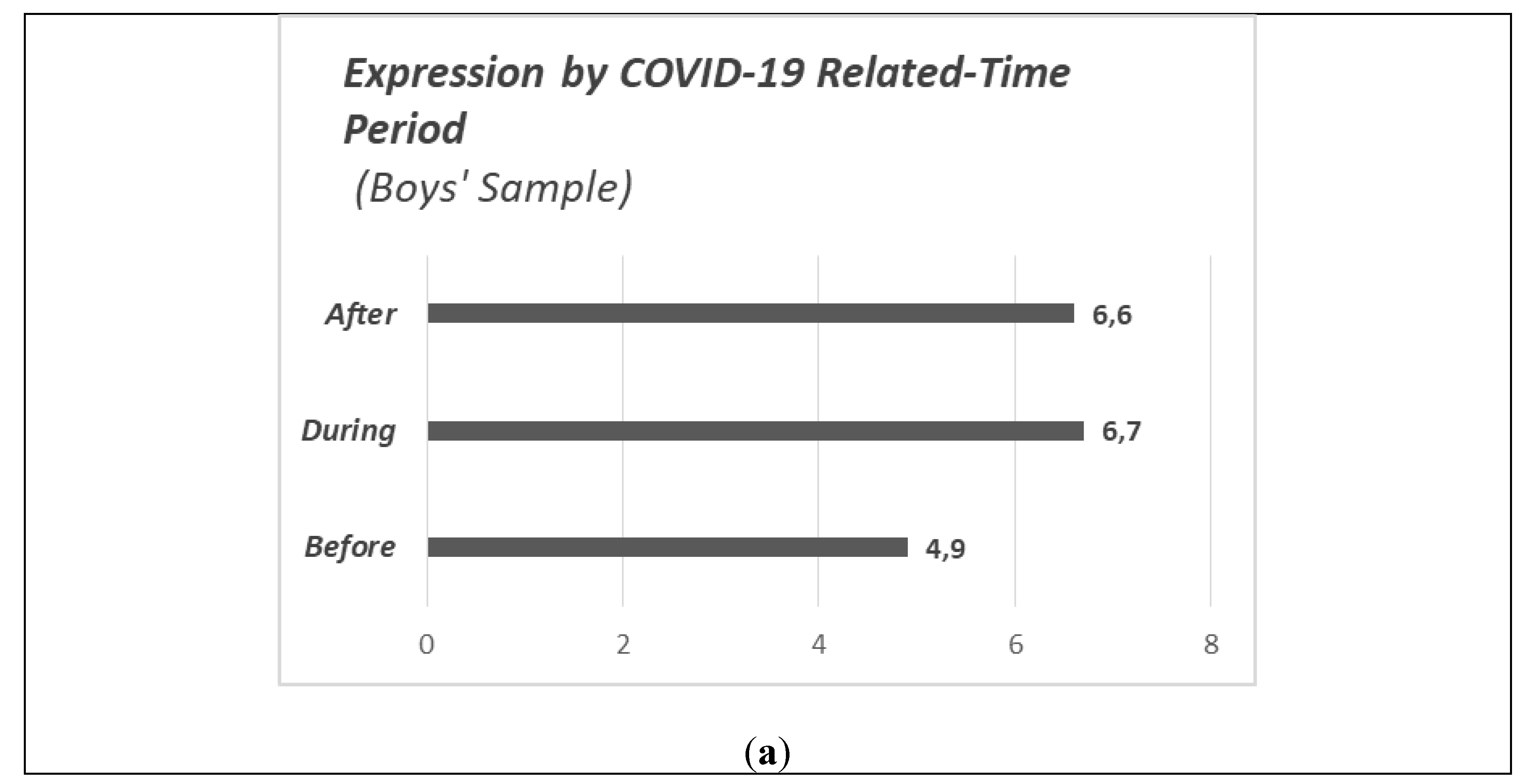

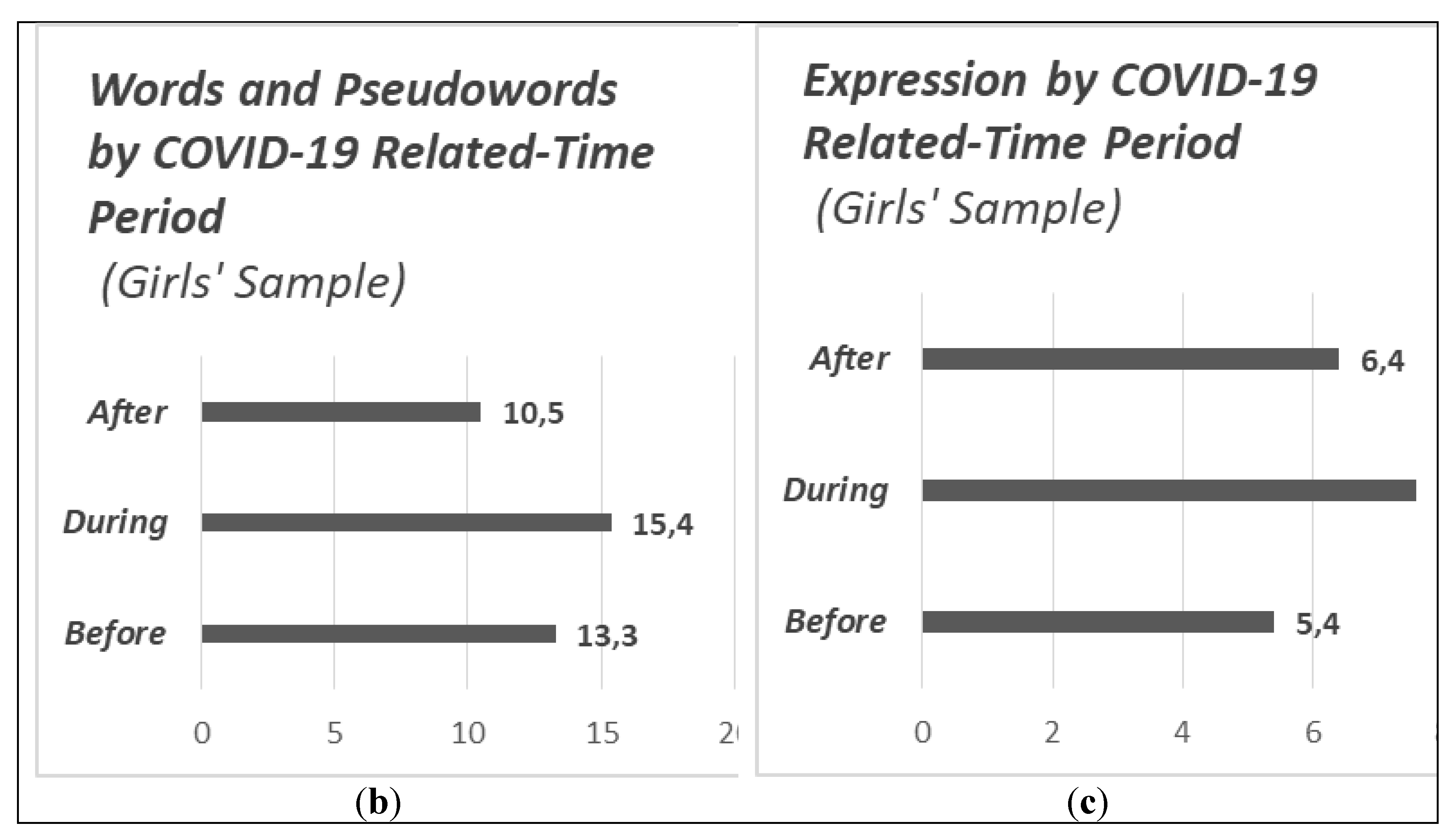

Additionally, the analyses above were performed separately between the two genders (

Figure 5). In the sample of boys, no significant difference was found in Words and Pseudowords among the three periods (p > 0.05). In contrast, the differences of expression measurements were found to be significant (F(2.99) = 7.971, p = 0.001). Boys had higher expression scores mid-pandemic (M = 6.7, SD=2.2), as well as post-pandemic (M = 6.6, SD=1.9), and significantly lower scores pre-pandemic (M = 4.9, SD=2). Post Hoc testing identified significant differences between the Before-During (p = 0.006) and Before-After (p = 0.001) periods.

In the girls’ sample, Words and Pseudowords had significant differences in terms of period (F(2.103) = 10.958, p < 0.001). The highest values in girls were recorded during COVID-19 (M = 15.4, SD=1.2), followed by values before (M = 13.3, SD=3.5) and after (M = 10.5, SD=5.9). Post Hoc testing showed that significant differences are found between the Before-After (p = 0.033) and During-After (p < 0.001) periods. Lastly, girls also recorded significant differences in Expression between the three periods (F(2.103) = 7.418, p = 0.001). The highest mean expression scores were measured in girls in the period of COVID-19 (M = 7.6, SD=1.4), followed by the measurements after (M = 6.4, SD=2.6) and before the pandemic (M = 5.4, SD=2). The Post Hoc test highlights as the only significant result, the difference of Before-During periods (p = 0.001).

4. Discussion

The overall objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the language development of preschool children in Greece, taking into account their age and biological gender. This evaluation was conducted retrospectively through a physical assessment of their developmental language status, utilizing a screening tool and quantitative measurements of words, pseudowords, and expressive language.

Of the total sample, one in three children appeared to have an abnormal language development profile (38,3%). In terms of the distribution of children's profiles analyzed across three evaluation periods, our results indicated a significant association between language development profile and measurement period. The abnormal profile was significantly more frequent following the pandemic compared to both the pre-pandemic and during pandemic periods. The gender-related subgroup analysis revealed that boys exhibited no statistically significant differences on abnormal language development profiles across the three specified time periods. In contrast, girls demonstrated a marked increase in the prevalence of abnormal language development profiles in the post-pandemic period.

During the pandemic, a notable increase in the abundance of words and pseudowords, as well as modes of expression, was observed in the total sample. In the boys' subgroup, a statistically significant difference was identified solely in modes of expression during the pandemic. In contrast, girls demonstrated significant increase not only in their expression but also in the usage of words and pseudowords during the same period.

These findings align with the authors’ expectations, as the preschool years are crucial for development across all domains and recent research indicates that pandemic-related changes, such as mask-wearing and peer isolation, negatively impacted language development. Social interaction, particularly with peers, and the ability to see facial expressions are vital for understanding language. This underscores the importance of participation in childcare settings; this was shown to enhance children’s language and executive function growth during the COVID-19 pandemic. This indirectly explains findings from various studies, including our own, revealing post-COVID-19 declines in language scores and impairments in motor and cognitive development of young students [

7,

8,

9,

12,

13,

14,

17].Another significant consequence of the pandemic measures is the increase in screen time, which has been significantly associated with poorer language development outcomes and higher risks of difficulties in both language comprehension and expressive skills [

18].

Infants represent the age group most vulnerable to the broader impacts of the pandemic. Those born and raised during the COVID-19 pandemic have exhibited delays in language development, which continue to persist for at least 30 months [

19]. Research suggests that limited social stimuli negatively affect healthy social development. Measures that hinder infants' ability to observe and imitate facial expressions, interpret emotional cues, and regulate their emotions contribute to the emergence of developmental language disorders. These disorders adversely impact children's communication skills, potentially hindering their social adaptation and overall life satisfaction [

18,

19,

20,

21].

Regarding children's mental health, the WHO reports that the COVID-19 pandemic has markedly elevated global anxiety and depression, especially in children. The closure of childcare centers intensified stress for parents, particularly mothers, leading to increased maternal depression. This rise in maternal depression adversely affected preschoolers' behavior. Research highlights the critical importance of positive mother-child interactions for children's well-being, noting that interactions with depressed mothers can significantly raise the risk of early childhood depression [

18,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Negative family environments, coupled with child temperament and stressful life events, appear to form a particularly detrimental combination that contributes to adverse outcomes in children's mental health [

21].

It is crucial to emphasize that of all the factors discussed the mental health of caregivers is the most significant factor influencing children's development. This may explain why children's developmental profiles continued to show concerning trends even after pandemic-related restrictions were lifted, mirroring patterns seen in other crises (e.g. war in Ukraine and rising inflation); adverse circumstances contribute to persistently high levels of parenting stress. The mental health of young children is closely tied to the psychosocial well-being of their caregivers [

25,

26,

27,

28].

There is, also, a growing concern about children's physical health, evidenced by rising rates of childhood obesity, likely associated with increased screen time and altered dietary habits during COVID-19 time [

15]. In light of these considerations, a critical objective is to systematically evaluate the extent to which these changes affect children's overall mental health and language development, as well as their quality of life. Additionally, it is essential to identify effective interventions to address these challenges [

29].

Future research should investigate the underlying causes of all these observed trends and specifically the longitudinal relationship between parental well-being and child outcomes. Meanwhile, health experts must draw attention to and provide guidance on minimizing potential impacts in similar emergency situations. Support interventions must prioritize fostering a positive family environment through conflict resolution strategies, reducing parenting stress, and enhancing parental resources. This approach is critical for ensuring that caregivers can effectively address the needs of their young children, promoting not only normal language development—which is central to our study—but also supporting their overall physical and mental development, which remains the primary objective [

2,

19,

20,

21,

24,

30,

31].

5. Limitations

We can categorize the limitations of this study into two main areas: those related to the study's methodology and sample characteristics, and those pertaining to the process of assessing children's language development.

First, it is important to emphasize that this is a retrospective study with a relatively limited number of participants. There was no follow-up on the progression of language development in the same sample over time. Although the families participating in the three COVID-19-related time periods exhibited similar sociodemographic characteristics, the results do not provide intra-individual observations from the same sample. Additionally, the sample was drawn from specific regions in Northern Greece, which may not be representative of the entire country. Adjustments for potential confounding factors that may adversely affect child development were also not conducted. These factors include for example COVID-19 infection or vaccination, as well as socioeconomic challenges that may exist independently of and simultaneously with the pandemic.

Furthermore, the conditions under which the assessments were carried out raise questions about the accuracy of the language development evaluations. The screenings took place in school settings, which are primarily designed for education and social interaction. This environment may have led to distractions for both the children and the evaluators, potentially compromising the integrity of the assessments. Additionally, while the “AνOμιΛο4” test utilized is applicable across a range of ages, it has been specifically validated for children aged from 3.6 to 4.9 years old [

32,

33]. Therefore, considering that our sample comprised children aged from 2.9 to 6.4 years old, we cannot exclude the possibility of misleading findings.

6. Conclusions

Overall, our study uncovered a statistically significant difference in the language development of preschool-aged children in Greece related to the COVID-19 pandemic, with one in three children of the total sample exhibiting an abnormal language development profile. This trend was even more pronounced in the subsample collected after the pandemic, where 42% of children exhibited an abnormal profile. Girls were mostly affected, and there was also an observed increase in the usage of words, pseudowords, and modes of expression, particularly during the pandemic, a finding that warrants further investigation. The measures implemented during the pandemic seem to have had a substantial impact on the language development of the children, both directly through restrictions imposed on children and indirectly by destabilizing adult caregivers, and, thereby, affecting the overall well-being of their children.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1: Frequencies of the variables Language development profile and COVID-19 related time-periods in the total sample; Table S2: Frequencies of the variables Language development profile and COVID-19 related time-period in the girls’ sample.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K., E.K. and G.K..; methodology, A.A. and A.G..; validation, A.A. and A.G.; investigation, A.K.,A.SS.,E.K. and G.K..; data collection, E.K. and I.K..; writing—original draft preparation, A.K., A.SS.; writing—review and editing, A.K., A.SS., A.A. and A.G.; visualization, A.SS., A.K., E.K. and G.K..; supervision, A.K.; project administration, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [AK] upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ng, J.Y.Y. , et al., The Impact of COVID-19 on Preschool-Aged Children's Movement Behaviors in Hong Kong: A Longitudinal Analysis of Accelerometer-Measured Data. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, W. , et al., The impact of lockdown on child adjustment: a propensity score matched analysis. BMC Psychol, 2024, 12, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hairol, M.I. , et al., The Impact of School Closures during COVID-19 Lockdown on Visual-Motor Integration and Block Design Performance: A Comparison of Two Cohorts of Preschool Children. Children (Basel) 2023, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Saulle, R. , et al., School closures and mental health, wellbeing and health behaviours among children and adolescents during the second COVID-19 wave: a systematic review of the literature. Epidemiol Prev 2022, 46, 333–352. [Google Scholar]

- Matali-Costa, J. and E. Camprodon-Rosanas, COVID-19 lockdown in Spain: Psychological impact is greatest on younger and vulnerable children. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2022, 27, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termine, C. , et al., Autism in Preschool-Aged Children: The Effects of COVID-19 Lockdown. J Autism Dev Disord 2024, 54, 3657–3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. , et al., Child behavior problems during COVID-19: Associations with parent distress and child social-emotional skills. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 2022, 78, 101375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner Katharina, W.L. , Will the Covid-19 Pandemic Leave a Lasting Legacy in Children’s Skill Development? CESifo Forum 2021, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, L. , et al. , Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and their families: a mixed-methods study protocol. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e049336. [Google Scholar]

- Masi, A. , et al. , Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the well-being of children with neurodevelopmental disabilities and their parents. J Paediatr Child Health 2021, 57, 631–636. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical, A. , World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alla, F. , et al., Valeur diagnostique de ERTL4: un test de repérage des troubles du langage chez l'enfant de 4 ans. Archives de Pédiatrie 1998, 5, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jean, G. , Le dépistage des troubles de langage en période préscolaire. Screening of language disorders in the preschool period. Can Fam Physician 1993, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Maeder, C. and B. Roy, Detecting language disorders in 4-year-old French children. An application of the ERTL-4. Child: Care, Health and Development 2000, 26, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, B. , et al., UniPseudo: A universal pseudoword generator. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 2023, 77, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malins, J.G. , et al., Is that a pibu or a pibo? Children with reading and language deficits show difficulties in learning and overnight consolidation of phonologically similar pseudowords. Dev Sci 2021, 24, e13023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.Q. , et al., Impact of COVID-19 on emotional and behavioral problems among preschool children: a meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr 2024, 24, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signe Boe Rayce, G.T.O. , Trine Flensborg-Madsen Mobile device screen time is associated with poorer language development among toddlers: results from a large-scale survey. BMC Public Health 2024, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Pejovic, J. , et al., Prolonged COVID-19 related effects on early language development: A longitudinal study. Early Human Development 2024, 195, 106081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C. , et al., Early childhood education and care (ECEC) during COVID-19 boosts growth in language and executive function. Infant Child Dev 2021, 30, e2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langrock, A.M. , et al., Coping With the Stress of Parental Depression: Parents' Reports of Children's Coping, Emotional, and Behavioral Problems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 2002, 31, 312–324. [Google Scholar]

- Giuseppe Maurilio, T.M. and T. Romina, DEPRESSION IN EARLY CHILDHOOD. Psychiatria Danubina 2022, 34, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Villodas, M.T. M. Bagner, and R. Thompson, A Step Beyond Maternal Depression and Child Behavior Problems: The Role of Mother–Child Aggression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 2018, 47, 634–641. [Google Scholar]

- Śliwerski, A. , et al. The Effect of Maternal Depression on Infant Attachment: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neece, C.L. A. Green, and B.L. Baker, Parenting Stress and Child Behavior Problems: A Transactional Relationship Across Time. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 2012, 117, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattangadi, N. , et al., Parenting stress during infancy is a risk factor for mental health problems in 3-year-old children. (1471-2458 (Electronic)).

- Woodward, D. , et al., A systematic review of substance use screening in outpatient behavioral health settings. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice 2023, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Buechel, C. , et al., The change of psychosocial stress factors in families with infants and toddlers during the COVID-19 pandemic. A longitudinal perspective on the CoronabaBY study from Germany. Front Pediatr 2024, 12, 1354089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J. , et al., Impact of COVID-19 restrictions on preschool children's eating, activity and sleep behaviours: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e051497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M. , et al., Parents' Stress and Children's Psychological Problems in Families Facing the COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Charney, S.A. M. Camarata, and A. Chern, Potential Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Communication and Language Skills in Children. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 2020, 165, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, D. , Un nouveau regard sur la dyslexie dysorthographie. Plaidoyer pour une reconnaissance précoce de ce handicap. Archives de Pédiatrie 1998, 5, 1383–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos-Ayav, C. , et al., The Validity of Screening Tests for Language and Learning Disorders in the Six-Year-Old Child (ERTLA6): Prospective Study. Santé Publique 2005, 17, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).