Submitted:

12 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Cysticercus Cellulosae TPx Protein

2.2. Cultivation and Activation of Jurkat Cells

2.3. Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.4. Transcriptome Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

2.5. Western Blotting

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

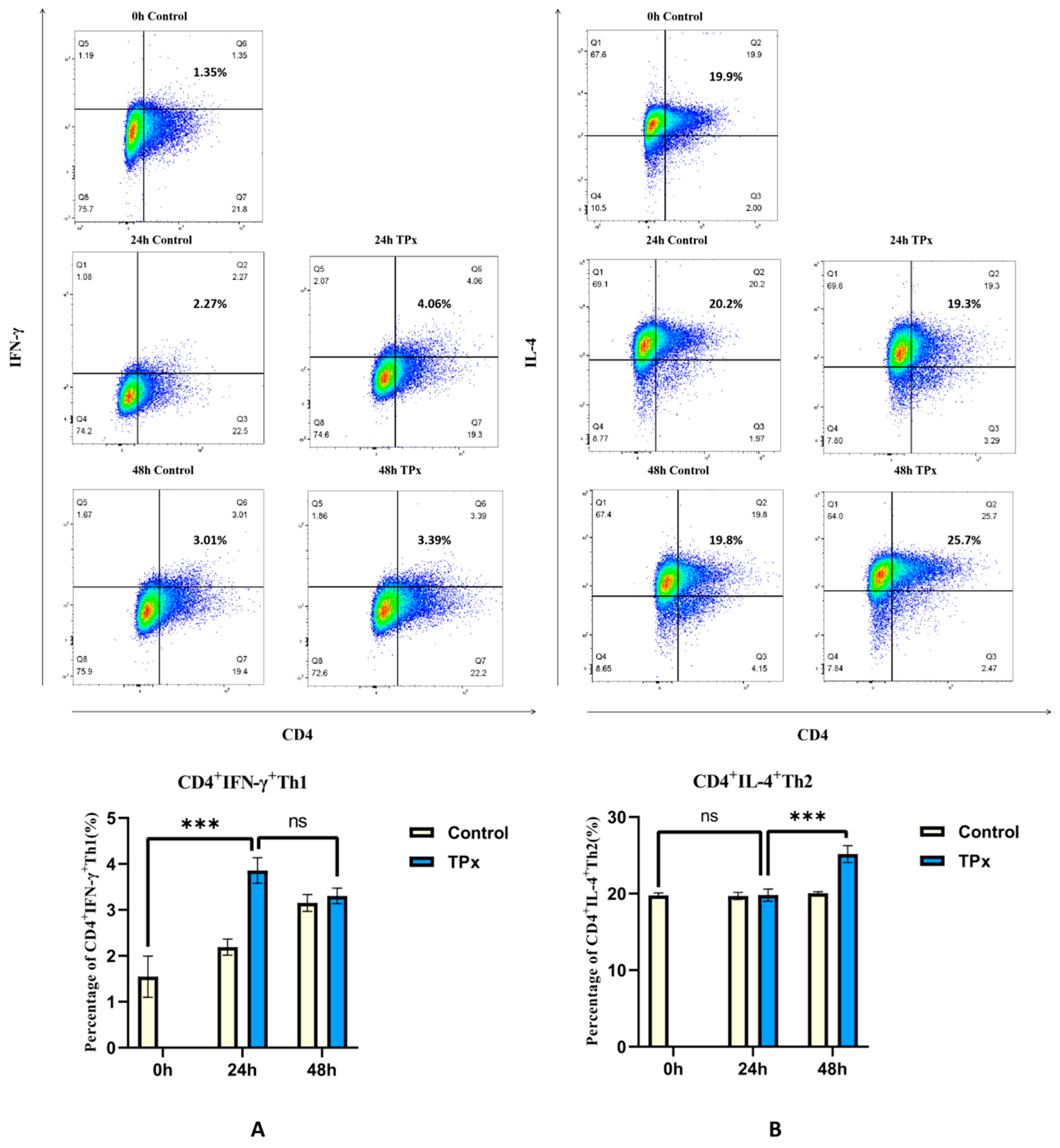

3.1. Effects of Cysticercus Cellulosae TPx Protein on Th1 and Th2 Cell Differentiation

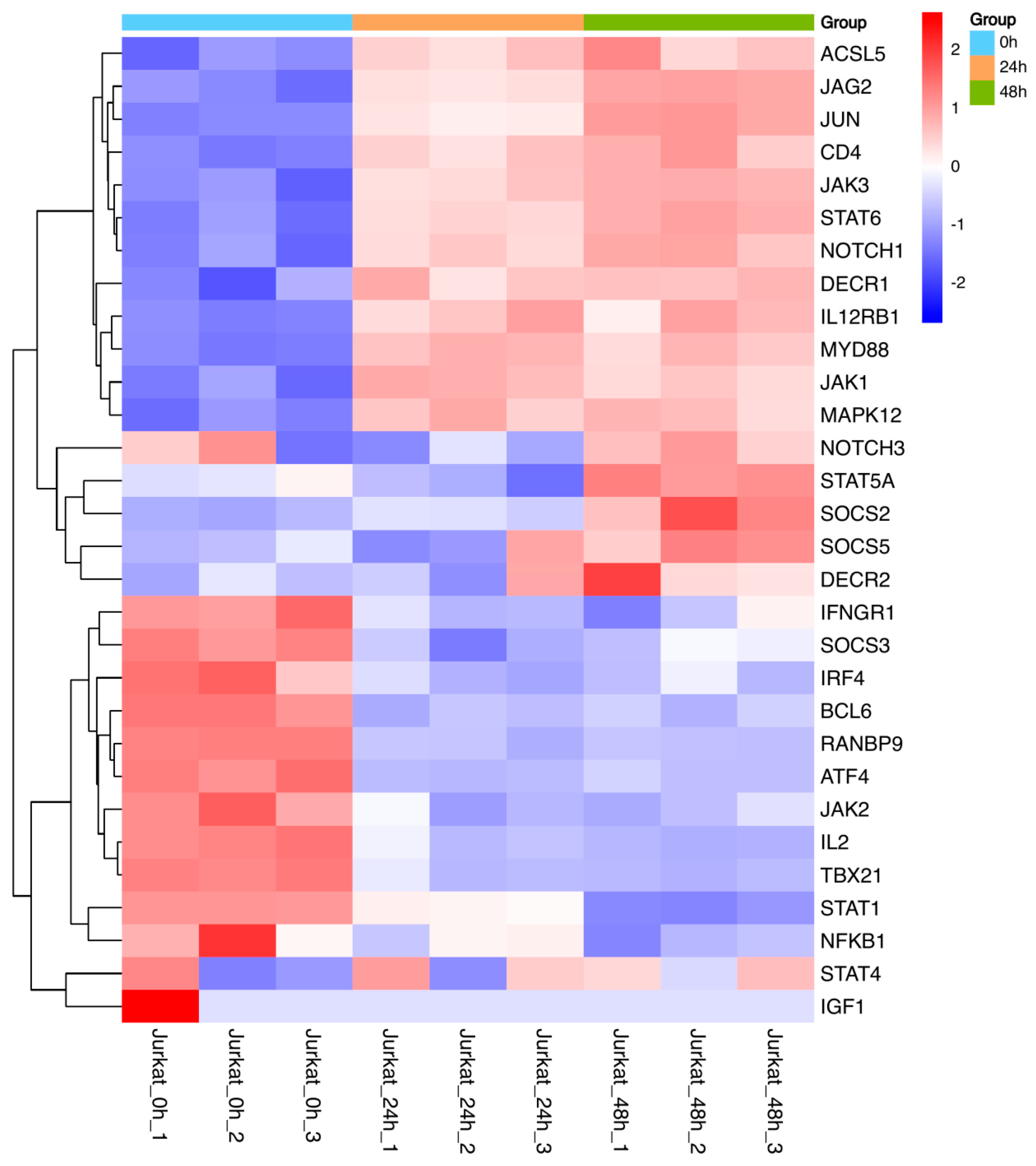

3.2. Differential Transcriptomic Analysis of TPx Protein-Induced Human Jurkat T Cell Differentiation

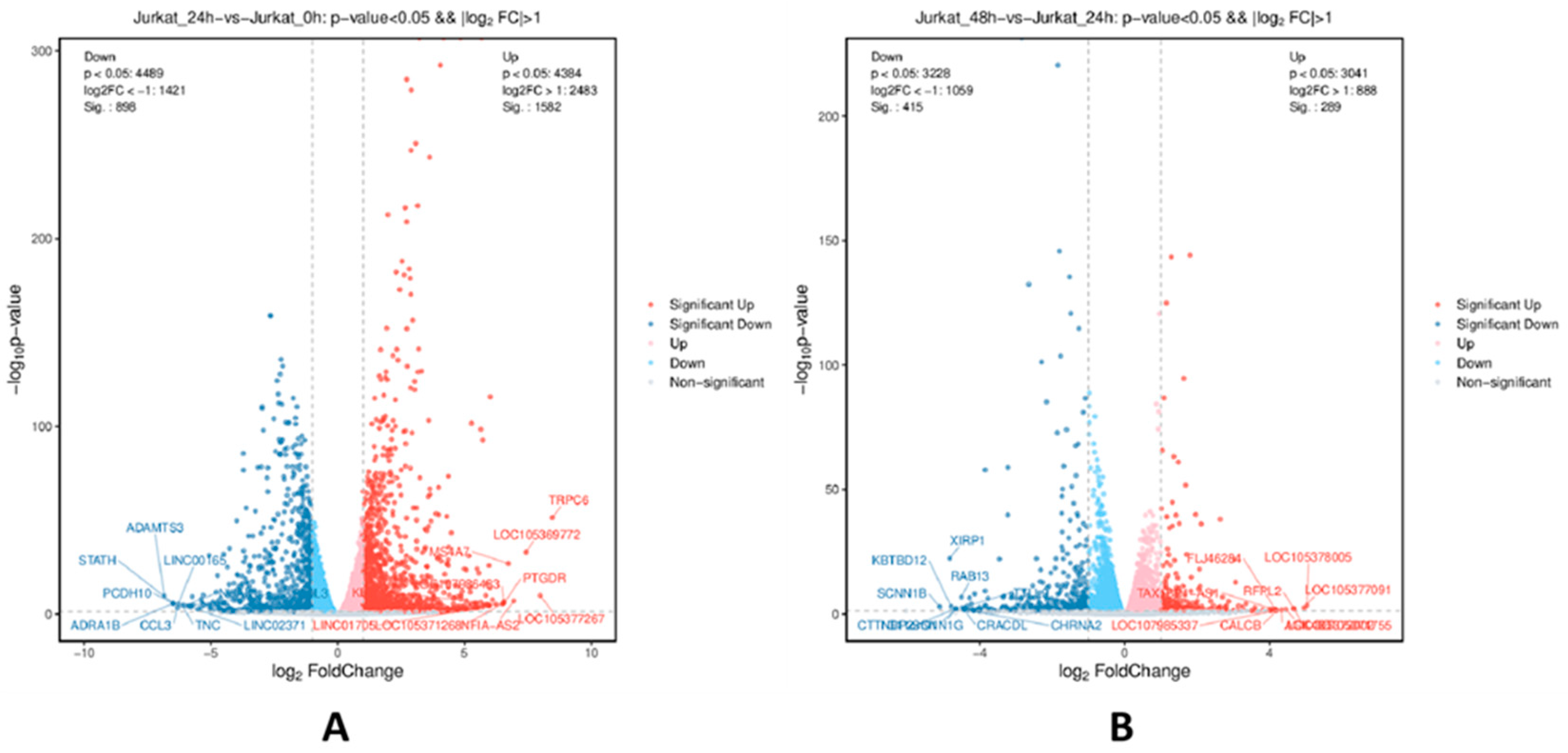

3.2.1. Differential Gene Analysis

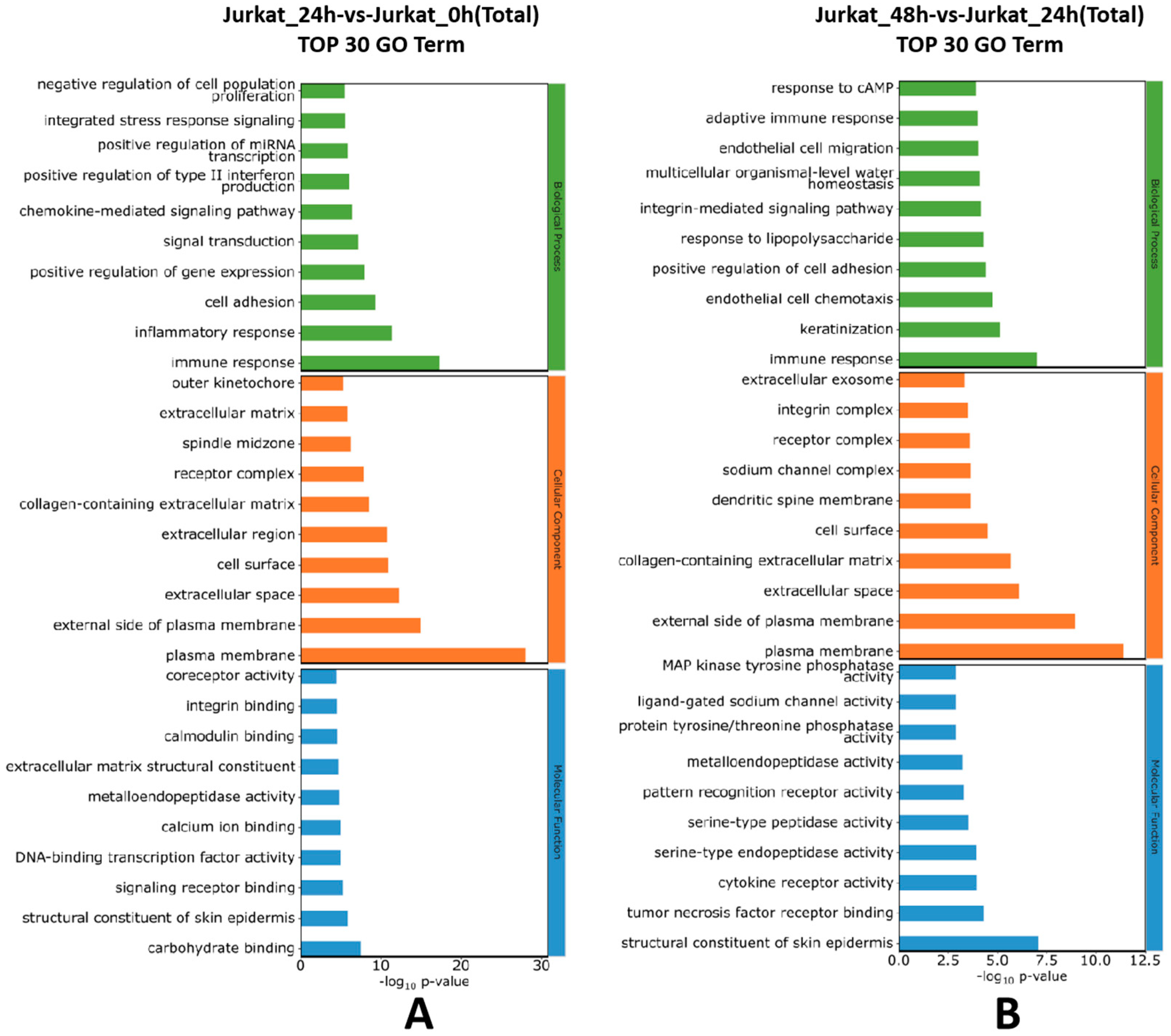

3.2.2. Gene Ontology (GO) Functional Annotation

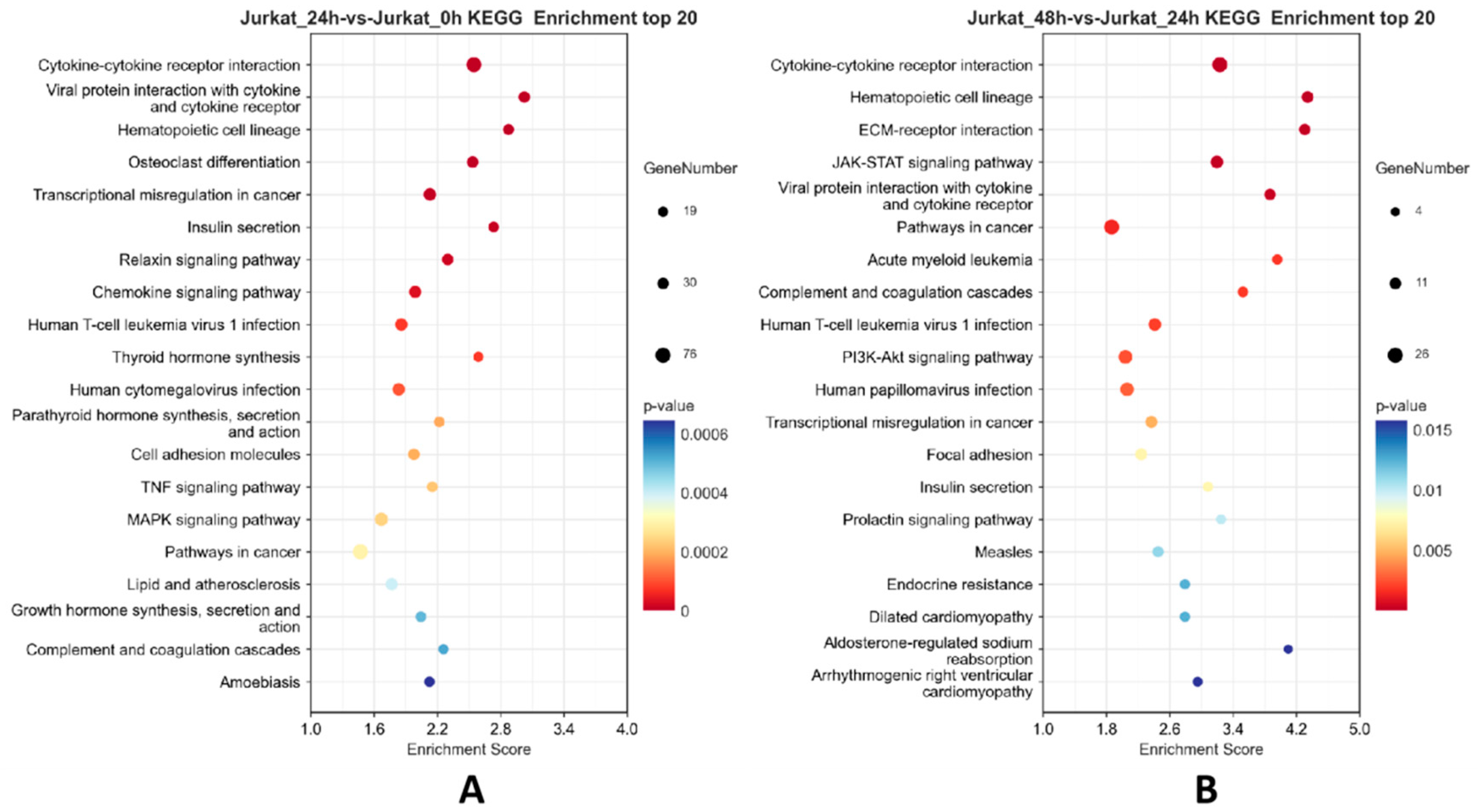

3.2.3. KEGG Enrichment Analysis

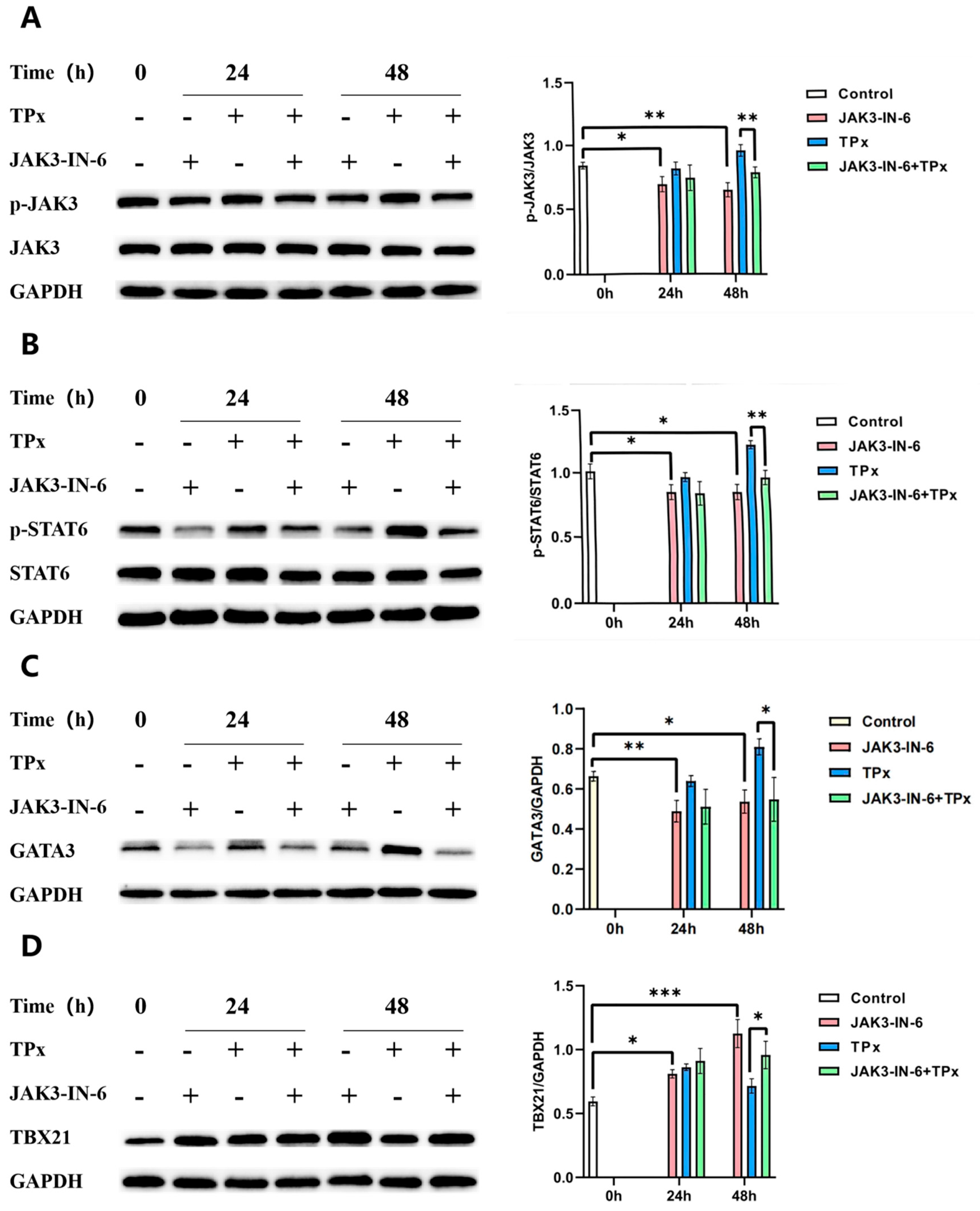

3.3. Western Blot Assay to Detect the Expression Levels of GATA3, TBX21, JAK3, and STAT6 Proteins and Protein Phosphorylation

3.4. Effects of JAK3-IN-6 Inhibitor on Cell Differentiation and the Expression Levels of JAK3, STAT6, GATA3, and TBX21 Proteins and Protein Phosphorylation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Del Brutto, O.H. Human neurocysticercosis: an overview. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujari, A.; Bhaskaran, K.; Modaboyina, S.; et al. Cysticercosis in ophthalmology. Surv Ophthalmol 2022, 67, 544–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, R.; Blond, B.N. The prevalence of and contributors to neurocysticercosis in endemic regions. J Neurol Sci 2022, 441, 120393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butala, C.; Brook, T.M.; Majekodunmi, A.O.; et al. Neurocysticercosis: current perspectives on diagnosis and management. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 615703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Arora, N.; Rawat, S.S.; et al. Vaccine for a neglected tropical disease Taenia solium cysticercosis: fight for eradication against all odds. Expert Rev Vaccines 2021, 20, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sergio, R.M.; Elizabeth, M.E.; Omar, G.O.; et al. Transplastomic plants yield a multicomponent vaccine against cysticercosis. J Biotechnol 2018, 266, 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Nuamtanong, S.; Reamtong, O.; Phuphisut, O.; et al. Transcriptome and excretory-secretory proteome of infective-stage larvae of the nematode Gnathostoma spinigerum reveal potential immunodiagnostic targets for development. Parasite 2019, 26, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.M.; Zhou, B.Y. Research progress on the relationship between tapeworm excretion secretions and host immune effect. Chin J Parasitol Parasit Dis 2020, 38, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ouyang, R.; et al. Cysticercus cellulosae regulates T-cell responses and interacts with the host immune system by excreting and secreting antigens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 728222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.Z. Effect of proteomics-based cysticercus cellulosae excretory secretory antigen LRRC15 protein on T-cell immune response in piglets. Zunyi: Zunyi Medical University, 2022.

- He, W.; Li, L.Z.; Sun, X.Q.; et al. Screening, validation, T-cellantigenicepitopes prediction and eukaryoticexpression of cysticercus cellulosae excretory-secretory antigen thioredoxin peroxidase protein. Journal of Pathogen Biology 2023, 18, 174–179. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; He, W.; Fan, X.; et al. Proteomic analysis of Taenia solium cysticercus and adult stages. Front Vet Sci 2023, 9, 934197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-López, J.; Jiménez, L.; Ochoa-Sánchez, A.; et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a 2-Cys peroxiredoxin from Taenia solium. J Parasitol 2006, 92, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Luo, X.N.; Wang, S.; et al. Prokaryotic expression and biological properties of thioredoxin peroxidase from Taenia solium. Acta Veterinaria et Zootechnica Sinica 2014, 45, 1512–1517. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.; Sun, X.; Luo, B.; et al. Regulation of piglet T-cell immune responses by thioredoxin peroxidase from cysticercus cellulosae excretory-secretory antigens. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 1019810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gause, W.C.; Rothlin, C.; Loke, P. Heterogeneity in the initiation, development and function of type 2 immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loke, P.; Harris, N.L. Networking between helminths, microbes, and mammals. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, E.B.; Cyr, S.L.; Arima, K.; et al. Current and emerging strategies to inhibit type 2 inflammation in atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2022, 12, 1501–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.R.; Zhang, R.H.; Li, R.; et al. The effects of helminth infections against type 2 diabetes. Parasitol Res 2021, 120, 1935–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhengu, K.N.; Naidoo, P.; Singh, R.; et al. Immunological interactions between intestinal helminth infections and tuberculosis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Q.Q.; Zhou, B.Y. Progress of researches on molecular mechanisms underlying helminth infection-mediated type 1/2 host immune responses. Chinese Journal of Schistosomiasis Control 2023, 35, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wen, T.H.; Tsai, K.W.; Wu, Y.J.; et al. The framework for human host immune responses to four types of parasitic infections and relevant key JAK/STAT signaling. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 13310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, L.; Silva Santos, G.L.; Muller, H.S.; et al. Schistosome-derived molecules as modulating actors of the immune system and promising candidates to treat autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. J Immunol Res 2016, 5267485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSorley, H.J.; Hewitson, J.P.; Maizels, R.M. Immunomodulation by helminth parasites: defining mechanisms and mediators. Int J Parasitol 2013, 43, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peón, A.N.; Ledesma-Soto, Y.; Olguín, J.E.; et al. Helminth products potently modulate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by downregulating neuroinflammation and promoting a suppressive microenvironment. Mediators Inflamm 2017, 8494572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.L.; Yu, X.H.; Li, Y.; et al. Schistosoma japonicum soluble egg antigen protects against type 2 diabetes in Lepr db/db mice by enhancing regulatory T cells and Th2 cytokines. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasby, E.A.; Hasby Saad, M.A.; Shohieb, Z.; et al. FoxP3+ T regulatory cells and immunomodulation after Schistosoma mansoni egg antigen immunization in experimental model of inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Immunol 2015, 295, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, T.B.; Giacomin, P.R.; Loukas, A.; et al. Helminth immunomodulation in autoimmune disease. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.L.; Nong, G.M. Advances in the application of Jurkat cell models in infectious disease research. Chinese Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics 2018, 20, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prodjinotho, U.F.; Lema, J.; Lacorcia, M.; et al. Host immune responses during Taenia solium neurocysticercosis infection and treatment. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14, e0008005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.N. My experience on taeniasis and neurocysticercosis. Trop Parasitol 2021, 11, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Prasad, K.N.; Cheekatla, S.S.; et al. Immune response in symptomatic and asymptomatic neurocysticercosis. Med Microbiol Immunol 2011, 200, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Zhu, J. CD4 T helper cell subsets and related human immunological disorders. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 8011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.M.; Zhou, B.Y. Research progress of immunoregulation of T lymphocytes in cysticercosis. Chin J Endemiol 2021, 40, 164–168. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.L.; Asahi, H.; Botkin, D.J.; et al. Schistosome infection stimulates host CD4(+) T helper cell and B-cell responses against a novel egg antigen, thioredoxin peroxidase. Infect Immun 2001, 69, 1134–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, A.L.; Tian, X.; Chen, D.; et al. Modulation of the functions of goat peripheral blood mononuclear cells by fasciola gigantica thioredoxin peroxidase In Vitro. Pathogens 2020, 9, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Q.W.; Zhang, N.Z.; Li, W.H.; et al. Trichinella spiralis thioredoxin peroxidase 2 regulates protective Th2 immune response in mice by directly inducing alternatively activated macrophages. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Zaragoza, M.; Jiménez, L.; Hernández, M.; et al. Protein expression profile of Taenia crassiceps cysticerci related to Th1- and Th2-type responses in the mouse cysticercosis model. Acta Trop 2020, 212, 105696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, G.; Yang, Z.Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; et al. Research progress on the effect of SOCS on Th cell differentiation in infectious diseases by regulating JAK/STAT pathway. Chinese Journal of Mycology 2021, 16, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, D.C.; Restifo, N.P. Suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) in T cell differentiation, maturation, and function. Trends Immunol 2009, 30, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Aleem, M.T.; Aimulajiang, K.; et al. The GT1-TPS structural domain protein from Haemonchus contortus could be suppressive antigen of goat PBMCs. Front Immunol 2022, 12, 787091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, E.J.; Smith, E.E.; Whittingham-Dowd, J.; et al. Intestinal epithelial suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) impacts on mucosal homeostasis in a model of chronic inflammation. Immun Inflamm Dis 2017, 5, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.; Kumaraswami, V.; Nutman, T.B. Transcriptional control of impaired Th1 responses in patent lymphatic filariasis by T-box expressed in T cells and suppressor of cytokine signaling genes. Infect Immun 2005, 73, 3394–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Liang, X.; Shaikh, A.S.; et al. JAK/STAT signal transduction: promising attractive targets for immune, inflammatory and hematopoietic diseases. Curr Drug Targets 2018, 19, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, G.R.; Cheon, H.; Wang, Y. Responses to cytokines and interferons that depend upon JAKs and STATs. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2018, 10, a028555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpathiou, G.; Papoudou-Bai, A., Ferrand E; et al. STAT6: a review of a signaling pathway implicated in various diseases with a special emphasis in its usefulness in pathology. Pathol Res Pract 2021, 223, 153477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.L.; Cao, J.; Lan, P.; et al. Effect of Trichinella spiralis infection on expression and distribution of colonic epithelial E-cadherin in mice and its mechanism. Chinese Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2013, 16, 386–389. [Google Scholar]

- Osada, Y.; Horie, Y.; Nakae, S.; et al. STAT6 and IL-10 are required for the anti-arthritic effects of Schistosoma mansoni via different mechanisms. Clin Exp Immunol 2019, 195, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Lu, M.; Wang, W.; et al. HcTTR: a novel antagonist against goat interleukin 4 derived from the excretory and secretory products of Haemonchus contortus. Vet Res 2019, 50, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compared groups | Regulated type | q-value<0.05&|log2FC|>1.0 |

|---|---|---|

| Jurkat_24h-vs-Jurakt_0h | Up-regulated | 631 |

| Down-regulated | 304 | |

| Jurkat_48h-vs-Jurakt_24h | Up-regulated | 199 |

| Down-regulated | 248 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).