1. Introduction

Aneurysm derives from the Greek ανɛυρυσμα (aneurusma), meaning widening, and can be defined as a permanent and irreversible localized dilatation of a vessel to greater than 50% of normal size [

1]. Aortic aneurysms are typically asymptomatic and undiagnosed. The progression of aortic aneurysms is associated with devastating outcomes such as aortic dissection and rupture. Aortic dissection causes sudden, severe pain and is immediately life-threatening, as it can lead to aortic rupture with extensive hemorrhage or acute loss of perfusion to various organs. Aortic ruptures account for 1-2% of deaths in Western countries [

2]. Aortic aneurysms can affect virtually any segment of the aorta, including the thoracic (Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms, TAA) and abdominal regions (Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms, AAA). However, there is significant heterogeneity in the distribution of these aortic aneurysms, with the prevalence of AAAs being three times higher than that of TAAs. While both TAA and AAA share common pathogenic feature, such as anatomic appearance, weakened aortic walls, alterations in the extracellular matrix (ECM), dysfunction and loss of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs); they are distinct disorders in terms of prevalence and etiology [

3].

Alarmingly, over 95% of TAA cases remain asymptomatic until acute dissection occurs, often too late for effective medical intervention. Thoracic aortic dissections are highly fatal, causing sudden death in up to 50% of affected patients. Although, treatment with β-adrenergic antagonists (β-blockers) or Losartan (Angiotensin-II receptor1 antagonist) might slow the progression of thoracic aortic aneurysms, the cornerstone of preventing premature deaths due to TAA dissections is aggressive surgical intervention to repair the thoracic aorta [

4]. Hence, early diagnosis and timely surgical repair are critical to improving outcomes and reducing the high mortality associated with this condition. Therefore, research aimed to investigate the molecular mechanisms regulating vascular damage in TAA would enable the development of new effective pharmacological therapies to prevent growth and fatal outcomes.

Latest studies have highlighted the critical role of mitochondrial metabolism in vascular homeostasis, underscoring its importance in maintaining cardiovascular integrity [

5,

6]. Specifically, mitochondrial dysfunction, coupled with metabolic rewiring, has been implicated in the development and progression of both TAA and AAA. These metabolic alterations appear to significantly contribute to underlying pathogenic processes, including oxidative stress, and aberrant ECM remodeling [

7,

8,

9]. Actually, novel pharmacological strategies aimed at boosting mitochondrial function and metabolic homeostasis could represent promising therapeutic approaches.

This review summarizes the main mechanisms described in hereditable TAA in mitochondrial metabolism and provides new data on the common mechanism of vascular smooth muscle cell metabolism in hereditary TAA.

2. Molecular Mechanisms in Hereditable Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms

TAAs can be classified as sporadic or genetic. Sporadic or acquired TAAs are primarily associated with cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, aging and increased biomechanical stress on the aorta, including conditions like pregnancy [

10]. In contrast, genetic TAAs occur in younger patients and can be further categorized as syndromic or familial non-syndromic. Syndromic TAAs are linked to systemic manifestations seen in connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome (MFS), Loeys-Dietz syndrome (LDS, Cutis Laxa, and vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS). Familial non-syndromic TAAs, also known as Familial Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms and Dissections (familial TAA, FTAAD), lack systemic features and are often inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with reduced penetrance and variable expression, affecting factors such as the age of onset, aneurysm location, and aortic diameter at dissection [

11,

12,

13].

FTAAD was first described in families where affected members across generations exhibited thoracic aortic disease without phenotypic features of syndromes like MFS or EDS, or systemic hypertension [

11]. Subsequent studies revealed that up to 20% of patients with thoracic aneurysms or dissections who lack syndromic features have an affected first-degree relative, emphasizing the importance of family history. Interestingly, the distinction between syndromic and non-syndromic TAA is often a continuum, as mutations in genes like

FBN1 (MFS) or

TGFBR1/2 (LDS) can also cause non-syndromic Familial TAA (FTAA) [

13,

14].

Additional causative FTAA-genes have been identified that encode proteins involved in VSMCs contraction and structural integrity. Among these,

ACTA2, which encodes the smooth muscle-specific isoform of α-actin, is the most mutated gene in FTAA. Other causative genes include those implicated in the extracellular matrix (ECM) and TGF-β signaling pathways, such as TGFBR2, TGFB2, and SMAD3, as well as contractile apparatus components like MYH11, MYLK, and PRKG1 [

11]. Despite these discoveries, over 70% of families with non-syndromic TAA lack mutations in the currently known genes, indicating that additional causative mutations remain to be identified [

14].

Marfan Syndrome (MFS) is the most well-known and common hereditary genetic disorder affecting connective tissue, associated with TAA. MFS has a prevalence of approximately 1 in 5,000 individuals and does not exhibit segregation by race, ethnicity, geographic distribution, or sex [

15,

16]. This systemic pathology manifests a broad spectrum of clinical features, with musculoskeletal abnormalities, such as excessive bone growth, being the most recognizable. However, cardiovascular complications, particularly TAA, represent the most severe threat to morbidity and mortality in MFS patients [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

The paradigmatic cause of MFS is a mutation in the

FBN1 gene, located on chromosome 15. Fibrillin-1 is a large glycoprotein that assembles into microfibrils, providing structural support to tissues and regulating critical molecular pathways [

15,

16,

20,

21]. A key pathway influenced by Fibrillin-1 is TGF-β signaling. Latent TGF-β binding proteins (LTBPs) anchor TGF-β complexes to the ECM via Fibrillin-1, ensuring proper sequestration and controlled activation [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Mutations in

FBN1 disrupt this interaction, leading to dysregulated TGF-β signaling. This results in excessive activation of TGF-β, compromising ECM integrity, promoting VSMC dysfunction, and driving pathological vascular remodeling, fibrosis and aortic dilation [

25]. Interestingly, TGF-β exhibits a dual role in MFS pathophysiology. During early disease stages, heightened TGF-β activity may promote compensatory tissue repair and vascular remodeling. However, chronic overactivation contributes to maladaptive processes such as aortic wall degeneration, fibrosis, and VSMC apoptosis, as demonstrated in animal models. This biphasic role underscores the complex interplay between protective and detrimental effects of TGF-β signaling in MFS progression [

22,

23,

24,

26].

In addition to TGF-β, Angiotensin II (AngII) one of the main regulators of blood pressure, is a significant contributor to MFS-associated vascular pathology, although the precise molecular mechanism is not well understood. Elevated AngII levels, often driven by vascular ECM-remodeling and aortic dilation, exacerbate disease progression through both canonical pathways (via the angiotensin receptor type 1, ATR1) and non-canonical mechanisms, such as ROS-mediated activation of Smad-independent signaling cascades, including MAPK. This enhances non-canonical TGF-β activity, triggers a feedback loop that amplifies vascular fibrosis, ECM remodeling, and smooth muscle cell dysfunction, further accelerating aortic degeneration [

27,

28].

The therapeutic potential of targeting these pathways has been extensively explored in preclinical and clinical settings. Losartan, an ATR1 antagonist, has shown promising results in mitigating MFS progression. Preclinical studies in murine models of MFS demonstrated that losartan effectively reduces aortic aneurysm growth, improves ECM integrity, and normalizes TGF-β signaling [

29]. Hence, losartan (ATR1 inhibitor) by his dual mechanism of action by blocking direct AngII and indirect TGF-β signaling was a promising pharmacological strategy in MFS. Nevertheless, these findings were not supported by clinical trials in human patients with MFS, where losartan did not attenuate aortic root dilation compared to treated with atenolol [

30,

31,

32].

Recent research also highlights a novel facet of molecular drivers of MFS-aortic disease, involved in pathological metabolic reprogramming. Emerging evidence suggests that MFS-associated mutations and ECM disruption lead to altered cellular metabolism, contributing to disease progression. Dysregulated metabolic pathways, including oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis, have been implicated in VSMC dysfunction and aortic wall degeneration. This metabolic reprogramming represents an adaptive but ultimately pathological response to ECM stress, linking mitochondrial dysfunction and energy imbalances to the progressive aortic pathology seen in MFS [

7,

33]. Targeted new therapies, along with further investigation, hold promise for improving outcomes and reducing life-threatening complications in individuals with MFS.

3. Mitochondrial Function in Vascular Pathophysiology

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles essential for energy metabolism, signaling, and cellular homeostasis. Their primary function is ATP production via oxidative phosphorylation, a process that generates a proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane to drive ATP synthase. Nevertheless, the function of mitochondria goes beyond their competence to generate molecular energy, mitochondria also regulate apoptosis, calcium metabolism and produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) as byproducts, linking mitochondrial function to vascular health [

34]. Mitochondria quickly adapt to stressors by altering their morphology through fission and fusion, optimizing bioenergetic functions, and regulating self-renewal through biogenesis or degradation via autophagy to maintain cellular homeostasis [

35]. The metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic glycolysis, analogous to the Warburg effect observed in cancer, represents a maladaptive response to mitochondrial impairment. Mitochondrial dysfunction, defined as the inability of mitochondria to adapt appropriately to cellular needs, supports many vascular disorders and driving processes such as normal and premature aging, inflammation, and apoptosis [

36,

37,

38]. In cardiovascular diseases, particularly atherosclerosis, key pathological features include DNA damage, chronic inflammation, cellular senescence, and apoptosis [

39,

40,

41,

42]. Growing evidence highlights mitochondrial dysfunction as a pivotal contributor to vascular disease development, emphasizing its central role in maintaining normal vascular physiology and its disruption in pathological conditions [

43].

3.1. Mitochondrial Biogenesis

Proper mitochondrial function is sustained by mitochondrial biogenesis pathways, particularly those regulated by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1α. Rather than being produced de novo, new mitochondria are formed by adding components to existing ones [

44]. Mitochondrial biogenesis relies on the coordinated expression of both mitochondrial- and nuclear-encoded proteins, as well as the replication of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Mitochondria possess their own circular genome (mtDNA), which is replicated independently of the nuclear genome [

45]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1a) is a transcription factor which promotes the expression of nuclear genes critical for mitochondrial replication and function, including the nuclear encoded gene, transcription Factor A Mitochondrial (TFAM). TFAM expression is essential for mitochondrial DNA replication and transcription, and its depletion disrupts oxidative phosphorylation, forcing cells to base their metabolism on glycolysis. [

7,

46]. Experimental studies, using transgenic rabbits with smooth muscle Pgc-1α-overexpression demonstrated an increase in the levels of mitochondrial complex proteins, reducing senescence and maintained the contractile phenotype of VSMCs during atherosclerosis development [

47]. In the context of AAA, vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) from AAA patients, exhibit a mitochondrial dysfunction, by reducing mtDNA content [

48]. This mitochondrial dysfunction leads to a metabolic shift toward glycolysis, contributing to VSMC dedifferentiation, ECM remodeling, and medial layer thickening [

49]. Similarly, in pulmonary arterial hypertension, pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells undergo metabolic rewiring, favoring glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation.

Aberrant mtDNA packaging can activate cytosolic cGAS-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathways [

44]. cGAS-STING signaling is a primary driver of mtDNA stress and contributes to aneurysm progression [

50]. STING activation in aortic tissue induces oxidative stress responses, cell death signals, DNA damage, and ECM degradation via MMP9 expression, making STING a critical molecule in aortic degeneration and dissection [

50,

51].

This shift promotes hyperproliferation, apoptosis resistance, and vascular obstruction. The overexpression of glycolytic enolase enzyme isoform ENO1 in pulmonary hypertension further drives the synthetic dedifferentiated phenotype of pulmonary smooth muscle cells, exacerbating disease progression.

3.2. Mitochondrial Fusion-Fission

The functionality and the number and morphology of mitochondria play a critical role in vascular wall homeostasis. Mitochondria can change its number via biogenesis or though by fusion and fission. Fusion joins two nearby mitochondria, keeping them healthy and enhancing oxidative phosphorylation capacity. This fusion is driven in the inner membrane by optic atrophy protein 1 (Opa1) and in the outer membrane by mitofusin-1 and mitofusin-2. By other hand, fission is mediated by dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), mitochondrial fission 1 protein (Fis1) and mitochondrial fission factor (Mff) and helps to the redistribution of the mitochondrial content and facilitates the removal of damaged mtDNA [

44,

50,

52].

Balance between fusion and fission is highly important in cardiovascular disease. Moreover, exacerbation of mitochondrial fission by DRP1 activation and reduction of mitochondrial fusion could be a contributing factor. An example is intimal hyperplasia, in which VSMCs migration can be limited by controlling mitochondrial fission which contributes to cardiovascular disease. Regarding the endothelial cells, a highly expressed circulating RNA is circTMEM165, which regulated mitochondrial fission by Drp1; and finally, in inflammatory macrophages mitochondrial fission was induced[

53].

3.3. Mitophagy

Mitophagy, the recycling of mitochondria by autophagosomes, is another crucial process. The signal starts when mitochondrial damage occurs, such as the depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane. In this process, mitophagy is initiated to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis. In a healthy state, Parkinson’s protein 2 (Parkin) is found in an autoinhibited form in the cytosol. However, Parkin is recruited to depolarized mitochondria as a signal amplifier, while PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) functions as a mitochondrial damage sensor. Triggers such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) or starvation leads to PINK1 activation, which subsequently recruits Parkin. Another important component in this PINK1-Parkin mediated mechanism is ubiquitin chains, which act as signal effectors. These ubiquitin-tagged mitochondria help autophagosomes encapsulate them for lysosomal degradation [

54].

Defects in mitophagy have been linked to cardiovascular disorders. Moreover, lack of mitophagy induces cardiovascular damage linked to an increase inflammation, mitochondrial DNA damage, oxidative stress and decrease of mitochondrial biogenesis. Healthy individuals exhibit lower ROS levels compared to patients with TAA, emphasizing the role of mitochondrial health in vascular integrity[

51].

In animal atherosclerosis model, aged mice compared to young mice showed higher progression of atherosclerosis due to hyperlipidemia exacerbated mitochondrial dysfunction elevating Parking and IL-6 [

55]. Pathological mechanisms of atherosclerosis are closely related to mitophagy linked to ROS, hypoxia, glucose and lipid metabolism disorders and hypoxia causing ECs damage and the proliferation and the phenotypic switching of VSMC [

40]. PINK1/Parking-mediated mitophagy may control cell survival by eliminating damaged mitochondria [

56,

57,

58]. In VSMC, mitochondrial DNA damage may be induced by ox-LDL in AS plaques decreasing aerobic respiration [

59], VSMC phenotype conversion [

60] or apoptosis [

61] increasing the formation of unstable plaques [

62]. VSMC phenotype and proliferation could be regulated by mitophagy preventing autophagy or apoptosis caused by low levels of ox-LDL [

63,

64].

In abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) compared to healthy aortas, Pink1-Parkin interactions are decreased, this problems in mitophagy produces ECM degradation by the release of enzymes and VSMCs senescence, this issue in cell senescence and death could be mitigated by the activation of mitochondrial autophagy, being the activation of Pink1 a new target for the treatment of this disease, attenuating AAA formation [

65]. The expression of PINK1 varies between VSMC and macrophages remarking distinct roles in different cel types. PINK1 may activate the mitochondrial autophagy in order to eliminate abnormal mitochondrial during the progression of AAA. Thus, mitochondrial autophagy activation via Pink1 may reduce cell death and senescence limiting AAA progression resulting in cell protection [

65]. PINK1 knockdown in VSMCs provokes AAA dilatation in murine models elevating mitochondrial ROS and mitochondrial dysfunction [

66].

3.4. Mitochondrial Alterations Associated to Reactive Oxygen Species Production

Mitochondrial dysfunction, often marked by impaired oxidative phosphorylation and excessive reactive oxygen species production, plays a critical role in various vascular diseases. A crucial aspect of this dysfunction is the partial uncoupling of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation due to proton leakage. In this process, protons translocated by the electron transport chain bypass ATP synthase and return to the mitochondrial matrix, leading to heat generation instead of ATP production. This process increases respiration, dissipates energy, and reduces the proton gradient, contributing up to 25% of the basal metabolic rate. Proton leak also influences mitochondrial superoxide production and acts as a regulatory mechanism during oxidative stress conditions, such as diabetes, tumor drug resistance, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and aging [

67].

In vascular diseases, reduced mtDNA copy numbers or metabolic deficiencies are associated with enhanced ROS formation and decreased mitochondrial biogenesis. Excessive ROS production by dysfunctional mitochondria exacerbates inflammatory responses, further worsening conditions like AAA and pulmonary arterial hypertension [

33,

48]. Moreover, excessive ROS contributes to cardiac aging by causing mtDNA damage, including mutations and a decrease in mtDNA copy number [

68]. The accumulation of dysfunctional, ROS-producing mitochondria may also accelerate vascular aging in hypertension [

69]. Over a lifetime, mitochondrial oxidative stress contributes to aortic stiffening by driving vascular wall remodeling, increasing stiffness of VSMCs, and inducing apoptosis [

70].

3.5. Mitochondrial Defects Associated with Aging.

Mitochondrial changes associated with aging also contribute to diseases linked to multimorbidity in frail older patients, including vascular disorders, by impairing mitochondrial metabolism, reducing ATP synthase activity, promoting electron leak, increasing ROS production and diminishing overall energy efficiency [

71]. Aging also decreases mitochondrial biogenesis in endothelial and VSMCs, impairing energy metabolism [

72]. Elevated mitochondrial ROS levels are implicated in age-related vascular dysfunction, driven by a dysfunctional electron transport chain, enhanced peroxynitration [

73], reduced glutathione [

74] and decreased Nrf2- (Nuclear factor [erythroid-derived 2]-like 2) mediated antioxidant defense [

75]. Mitochondria-derived H₂O₂ contributes to vascular inflammation by activating NF-κB [

76], while mtROS in VSMCs is linked to MMP activation and inducing apoptosis [

77]. mtDNA is highly susceptible to damage due to its proximity to ROS production, lack of histone protection, and limited repair capacity [

78]. Aging increases mtDNA mutations and deletions, impairing energy production and contributing to vascular aging and atherogenesis. mtDNA deletions have been detected in human atherosclerotic lesions [

79]. ApoE-Deficient and transgenic for PolG- (DNA polymerase subunit gamma mitochondrial) lacking in proof-reading activity accumulate mutations in their mtDNA and exhibit accelerated atherosclerosis, associated with diminished proliferation and increase in apoptosis of VSMCs [

80]. Therapeutic strategies targeting mtROS, such as resveratrol [

81], MitoQ [

82], have been shown as a promise in improving endothelial function and cognitive performance in aged models. Sirtuins, particularly SIRT1 and SIRT3, regulate mitochondrial function, including biogenesis, ROS production, and autophagy [

74] and their activity is reduced in aging. Resveratrol is an activator of sirtuin activity [

83]. NAD

+, a sirtuin cofactor, declines with age, partly due to PARP-1 overactivation [

84]. Restoring NAD

+ levels, such as through nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) supplementation, reverses mitochondrial dysfunction and vascular aging by activating sirtuin pathways [

85]. These alterations, coupled with vascular stiffening and hypertension, impair mitochondrial function and exacerbate vascular dysfunction [

34,

71].

3.6. Mitochondrial Alterations Associated with Cytoskeleton-ECM Axis

The cytoskeleton, composed of actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments, also plays a pivotal role in mitochondrial function and derivate processes which need the energy they produce [

34,

86]. Actin filaments guide mitochondrial transport to regions requiring energy output and immobilize them to maintain ATP supply throughout varying conditions, adapting their activity as the requirements change. Cytoskeleton filament polymerization influences mitochondrial membrane permeability and thus, directly affect mitochondrial metabolite input and energy output [

86]. Actin polymerization is critical for maintaining cellular differentiation states, therefore disruptions in cytoskeletal dynamics affect mitochondrial positioning and activity during processes like cell division, respiration, cell homeostasis and apoptosis[

34,

46,

86]. Recent research has shown that mitochondrial recruitment and cytoskeletal distribution has relation to pathological conditions in cancer, allowing cell movement, relocating mitochondria and enhancing their metabolism towards cytoskeleton [

86]. Cytoskeletal-ECM-mitochondrial interactions thus form a critical axis for vascular health, with disturbances contributing to disease states. The ECM, composed primarily of fibrillar proteins such as collagen, fibrillin, fibronectin, and proteoglycans, provides structural and biochemical support. It also participates in mechanotransduction and molecular signaling. ECM-homeostasis is crucial for maintaining vascular integrity, and disruptions can result in fibrosis and pathological remodeling [

87]. Mitochondria are closely linked to ECM dynamics, responding to mechanical signals transmitted through integrins and focal adhesions that connect ECM fibers to the intracellular cytoskeleton. These signals regulate mitochondrial distribution and activity, ensuring localized ATP production in regions of high demand [

34]. In fibroblasts, mitochondrial and metabolic regulators play a crucial role in ECM homeostasis. Fatty acid oxidation drives a catabolic fibroblast phenotype, promoting ECM degradation, whereas glycolysis supports an anabolic state, facilitating ECM remodeling [

87].

These findings highlight the potential of targeting mitochondrial pathways as therapeutic strategies for vascular diseases and underscore the complex interplay between mitochondrial function, aging, and aortic pathology. The ECM-cytoskeleton-mitochondrial axis might represent a key regulator in the pathophysiology of TAA, offering novel avenues for clinical intervention and new molecular mediators.

4. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Marfan Syndrome

Recent evidence highlights alterations in mitochondrial function as a pivotal factor in the development of TAA in MFS, emphasizing mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic remodeling as critical drivers of disease progression. Transcriptomics studies in aortas from Marfan syndrome mouse models (

Fbn1C[10341]G/+)[

7] and multi-omics approaches in human aortas from MFS patients [

88,

89] have consistently revealed significant reductions in key regulators of mitochondrial function, including PGC1α, TFAM, and mitochondrial complexes. Furthermore, impaired mitochondrial respiration in MFS-VSMCs triggers a metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis. This metabolic rewiring is accompanied by elevated lactate production and the activation of glycolysis-promoting pathways, such as HIF1α. Importantly, this metabolic remodeling has been associated to the pathological phenotypic switch of VSMCs, characterized by a loss of their contractile phenotype and increased ECM remodeling, senescence and inflammation [

7]. These findings identify mitochondrial dysfunction as one of the major canonical pathways disrupted in MFS.

Conditional

Tfam knockout mice specifically in VSMCs, exhibit a severe mitochondrial dysfunction, provide a compelling model for understanding loss of mtDNA in aortic pathology. These mice developed aortic aneurysms and dissections, accompanied by significant histological alterations, including elastin fragmentation, proteoglycan deposition, and medial degeneration; classic features associated with MFS aortic pathology. On a cellular level,

Tfam-deficient VSMCs undergo a pathological transformation, adopting a synthetic phenotype characterized by increased ECM production, and loss of contractile function. This phenotypic switch might be driven, in part, by the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway, triggered by mtDNA depletion and the cytoplasmic release of mitochondrial DNA fragments. This pathway induces chronic inflammation, marked by elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and promotes a senescent phenotype in VSMCs [

14]. These cellular changes further exacerbate the structural and functional decline of the aortic wall. Remarkably, these features mirror those observed in VSMCs derived from MFS patients, reinforcing the pivotal role of mitochondrial dysfunction in TAA pathogenesis. The similarities between the Tfam knockout model and MFS provide a strong foundation for exploring targeted therapies aimed at preserving mitochondrial integrity in TAA development.

Importantly, mitochondrial dysfunction in VSMCs is influenced by ECM composition. VSMCs cultured on ECM produced by

Fbn1-deficient cells exhibited reduced mitochondrial respiration, lower Tfam and mtDNA levels, and increased glycolytic activity, demonstrating that ECM from MFS-VSMCs directly affects cellular metabolism. These findings demonstrate that ECM derived from Marfan-VSMCs exerts a direct effect on cellular metabolism, highlighting the intricate interplay between ECM remodeling and mitochondrial function in driving MFS pathogenesis. Notably, mitochondrial function in MFS can be effectively restored by using the NAD

+ precursor nicotinamide riboside (NR). Treatment with NR enhances mitochondrial respiration, increases TFAM expression, and reduces glycolytic rate in both murine

Fbn1-deficient VSMCs and fibroblasts from MFS patients.

In vivo, NR administration not only reversed aortic dilation but also promoted actin polymerization within the aortic media, mitigated medial degeneration, and restored Tfam expression and mtDNA levels. Additionally, NR normalized the transcriptomic signature of genes implicated in mitochondrial function and Marfan pathogenesis in the aortas of MFS mice [

7]. The negative effect that mitochondrial dysfunction has on the change of phenotype from contractile to synthetic in MFS has been corroborated in a VSMC cellular model through FBN1 silencing. Furthermore, the restoration of the contractile phenotype through mitochondrial boosting by coenzyme Q10 further supports the potential therapeutic potential of the mitochondrial-ECM axis in MFS [

90].

Cutis laxa is a connective tissue disorder characterized by loose and wrinkle inelastic skin.

Fibulin-4R/R is a cutis laxa mouse model in which the ECM-protein Fibulin-4 is reduced, resulting in progressive ascending aneurysm formation and early death. In this model, VSMCs present a lower oxygen consumption and increased acidification rates, similarly to

Tgfbr-1M318R/+ (Loeys-Dietz syndrome) model and fibroblasts from MFS patients. Upon gene expression analysis, the activity of PGC1α in VSMCs was downregulated, and its activation restored the mitochondrial respiration rate and improved their reduced growth potential. Here, mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic dysregulation leads to increased ROS levels and altered energy production, which result in aortic aneurysm formation in a similar way the MFS model does [

91].

In AAA, impaired mitochondrial function in VSMCs has been linked to a metabolic shift toward glycolysis. Similar to observations in MFS, VSMCs from murine ApoE-deficient mice infused with AngII, as well as VSMCs from AAA patients, exhibit reduced expression of key mitochondrial regulators, including PGC1α and TFAM, along with decreased mtDNA levels. Notably, treatment with NR, significantly reduces AAA formation and the incidence of sudden death caused by aortic ruptures in ApoE-deficient mice model [

33]. Moreover, the extracellular protein Galectin-1 has been identified as a critical modulator of VSMC phenotype through its influence on mitochondrial function, playing a role in both atherosclerosis and AAA pathogenesis [

92]. These findings underscore the central role of mitochondrial function in VSMC behavior and remarks its potential as a therapeutic target for aortic aneurysms independently of their etiology.

5. Mitochondrial Respiratory Dysfunction in Loeys-Dietz Syndrome and Familial Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm and Dissections.

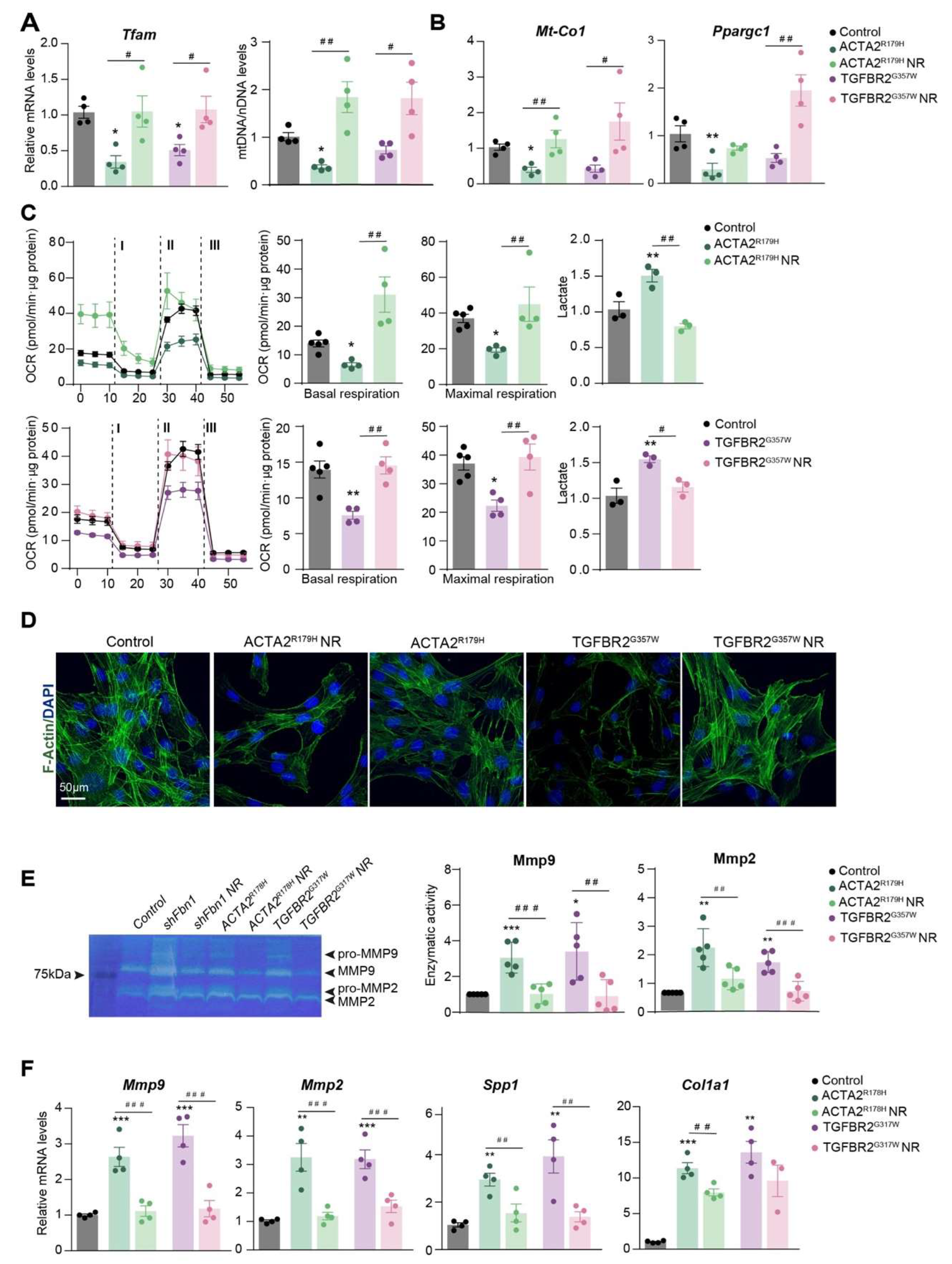

Previous research has demonstrated that mitochondrial metabolism is a key regulator of the VSMC phenotype during aortic remodeling in MFS and AAA, which is finely tuned by ECM composition [

7,

33,

90]. Therefore, we next explore whether mitochondrial metabolism was also affected in other Hereditable-TAAA disorders. We modeled different inherited-TAA diseases by overexpressing causative mutations in primary VSMCs, by using lentivectors to overexpress human

TGFBR2G357W or

ACTA2R179H mutations to reproduce LDS and FTAAD respectively. Overexpression of

ACTA2R179H or

TGFBR2G357W resulted in reduced levels of Tfam mtDNA and decreased mRNA expression of mitochondrial regulators (Figure A). Flux analysis of the oxygen consumption rate (OCR), an indicator of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, demonstrated diminished mitochondrial respiration in TAA-VSMCs (Figure B). This decline in mitochondrial function was accompanied by increased extracellular lactate production, suggesting a shift toward glycolysis as the primary source of cellular energy in the presence of these TAA mutations. Notably, incubation with mitochondrial booster, NR, reversed the impact of both mutations on these metabolic parameters (Figure A-B). Furthermore, NR enhanced contractility, as indicated by increased F-actin polymerization (

Figure 1C), while also reducing the expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinases and other secretory markers (

Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Nicotidamide Riboside treatment improves mitochondrial function and reduces synthetic phenotype in VSMCs with Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm mutations.

Figure 1.

Nicotidamide Riboside treatment improves mitochondrial function and reduces synthetic phenotype in VSMCs with Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm mutations.

These findings suggest that the reduction in Tfam expression and mtDNA levels induces a metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to glycolysis in VSMCs affected by different hereditable forms of TAA. Moreover, the mitochondrial function might be involved in the phenotypic switching of VSMCs during aneurysm development. Importantly, improving mitochondrial fitness in vitro restores the contractile phenotype of these cells. We observed that NR elevated Tfam and mtDNA levels, enhanced mitochondrial metabolism, and reduced the secretory phenotype in TAA cells. Therefore, glycolytic metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction play a central role in the pathogenesis of different hereditary TAAs, and mitochondrial boosters such as NR, might serve as a promising therapeutic option for treating different aortic aneurysm related disorders opening an immense avenue of therapeutic opportunities.

Effect of NR on mouse primary VSMCs overexpressing ACTA2

R179 or TGFBR2

G357W (to model FTAAD and LDS, respectively). These constructs were generously provided by Mark E. Lindsay

5. VSMCs were isolated and transduced as described in [

4]. Lentiviral transduction was performed in VSMCs over 5 h at a multiplicity of infection = 3. Cells were negative for

Mycoplasma. After 2 days of transduction, VSMCs were treated with NR (0.25 mg/ml) for 5 days. (

A) qPCR analysis of relative mtDNA content and RT–qPCR analysis of

Tfam,

Mt-Co1 and

Ppargc1a mRNA expression. (

C) OCR measured by Seahorse

Tm at basal respiration and after addition of oligomycin (I) and FCCP (II) to measure maximal respiration, followed by a combination of rotenone and antimycin A (III). The right-most panel shows extracellular lactate levels. (

D) Representative confocal imaging of filamentous actin (F-actin) stained with phalloidin (green); nuclei are stained with Dapi

API(Blue); (n=4). (

E) Gelatin-zymography analysis of Mmp2 and Mmp9 activity in 24h in conditional medium and RT-qPCR analysis of

Mmp9, Mmp2, Spp1, and

Col1a1 mRNA expression. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs Control; # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, ####P < 0.0001 vs NR treatment.

6. Clinical Perspectives

The aneurysm and its complications result in over 90% of deaths among patients with TAA. Open surgery or endovascular prothesis are still the main pathway to prevent aortic rupture and pharmacological treatments to prevent or reverse TAAD remain elusive [

93]. Surgery of TAA follows two main strategies: open surgical repair, which has been the standard since the 1950s; or endovascular repair, which is a less invasive approach [

94,

95]. However, both methods present similar rates of perioperative complications and permanent paraplegia among other drawbacks, which implies significant morbidity and mortality regardless of the method [

94]. This highlines the necessity of alternative pharmacological strategies to tackle thoracic aortic aneurysms to prevent lethal aortic rupture.

As of today, pharmacological treatments are based on lowering blood pressure to reduce biomechanical stress in the aortic wall by using β-blockers or Losartan. These drugs slow down the aortic disease in MFS and LDS-patients, but evidence is limited in terms of efficacy in lowering root dilatation and of targeting the underlying cause of progressive aortic degeneration [

95,

96].

Fluoroquinolones (FQs) are a widely used class of antibiotics with broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, targeting prokaryotic topoisomerases. Recent evidence suggests that FQs may contribute to the pathological development of TAA, particularly in patients with MFS [

97]. Ciprofloxacin, a commonly prescribed FQ that inhibits bacterial DNA topoisomerase, has been shown to induce both nuclear and mitochondrial damage [

98]. By impairing mitochondrial topoisomerase, ciprofloxacin triggers the release of mtDNA, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction, increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and cell death. Additionally, some studies suggest a link between FQs and collagen-related damage, potentially contributing to aortic aneurysm formation [

99,

100]. However, the evidence remains inconclusive. While certain studies have identified an association between FQ use and aneurysm formation, others have found no significant increase in the risk of intracranial aneurysms or dissections [

101]. Considering the potential of FQs to worsen mtDNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction, both key factors in TAA pathogenesis, their use should be approached with caution in patients with TAA or a predisposition to aortic disease, as they may accelerate aneurysm progression and elevate the risk of aortic rupture. Further research is needed to clarify the extent of these risks and guide clinical recommendations.

Resveratrol (RES) is a dietary supplement found in some nuts and plants. When RES is administered to

Fbn1C1041G/+ MFS mice, the aortic dilatation is reduced as effectively as losartan [

102]. RES induces NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), which is involved in cellular metabolism in processes such as enhancing the energetic cell status and its inhibition induces cellular senescence. RES effect in MFS is associated with the downregulation of detrimental aneurysm microRNA-29b (miR-29b) and improved elastin integrity and VSMCs survival [

95]. RES also reduced inflammation, senescence, angiogenesis and miR-29b in the murine models, which are all related to endothelial dysfunction. Endothelial dysfunction is described as an impaired vasorelaxation caused by the loss or overproduction of NO. In endothelial cells, RES promotes NO synthesis, which is a potent vasodilator synthetized by the endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) and is impaired in the MFS murine model. The inducible isoform (iNOS) is increased in the VSMC of MFS mice. Excessive NO production by iNOS produces oxidative stress and cellular damage by accumulation of peroxynitrites. RES neutralized the aortic iNOS and NO levels in

Fbn1C1041G/+ MFS mice [

103]. Recent clinical trial with RES in MFS patients was performed for a 1-year period. Daily treatment showed a tendency to decrease aortic dilation rate, but a larger randomized trial with a longer follow-up is needed to further confirm or discard the beneficial effects of RES in MFS patients [

104].

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD

+) and its reduced form NADH are a redox couple that is essential for a broad range of biochemical, particularly redox, reactions. NAD

+ levels decline during ageing in multiple species in a variety of ways, and its homeostasis alterations can be found in diabetes, cancer [

105,

106]. NAD

+ boosting can be a way to compensate for the mitochondrial dysfunction associated with the imbalance of this redox pair. Some NAD+ boosting strategies include the direct supplementation of NAD+ precursors [

7,

107], the stimulation of enzymes involved in the synthesis of NAD

+ [

108] and the prevention of the escape of intermediates from the NAD+ biosynthetic pathway [

105]. The boosting of NAD

+ through its precursors has emerged as a promising strategy to prevent and improve the conditions of patients with TAAD. Enzymes that recover NAD

+ molecules, such as the limiting rate enzyme on the salvage pathway Nicotine phosphoribosyltransferase (Nampt), have also shown an important role in maintaining a correct mitochondrial function, Conditional deficient mice for Nampt in VSMCs have shown a mild aortic dilation, more susceptibility to aortic dissection under risk factors and early senescence and loss of function. Results inversely correlate aortic damage markers with Nampt expression in both humans and mice, which hints at similarities with MFS pathological mechanisms regarding mitochondrial dysfunction and aortic damage[

109]. NAD

+ can be produced from different forms of vitamin B that are known as NAD

+ precursors, such as nicotinamide (NAM), nicotinic acid (NA) and nicotinamide riboside (NR) [

105]. The last one, nicotinamide riboside (NR), has been proven to restore mitochondrial metabolism and reverse aortic aneurysm in the MFS mouse[

7]. Even though clinical results yet need to shed light on its effectiveness, it has been demonstrated that NR can rise as much as 2.7-fold with a single oral dose in humans [

107]. This poses a promising future for patients with risk of TAAD, especially MFS patients, who currently don´t have access to an effective pharmacological alternative to surgery.

Future research directions in TAA pharmacological approaches appear to be shifting toward a focus on mitochondrial boosters and NAD

+ homeostasis. New data about NAD

+ boosting strategies in other clinical context is rapidly accumulating, but many issues still need to be addressed. Even after the first clinical trial with NR in 2016 [

107] and the multitude that followed and are still being carried out, there is still no evidence that the promising results observed in mice can be easily replicated in humans [

105]. To test the effectiveness of NAD

+ boosters, carefully planned clinical studies of longer duration, higher dose and a significantly large number of patients are needed [

105]. There needs to be an increase in clinical studies both in rare hereditary and acquired diseases, with different dose levels to back up the results. Considering that there already are phase I and II clinical studies in other related diseases, this initial process could be sped up to bring the alternative treatments that the patients require.

7. Discussion

Mitochondrial dysfunction and a metabolic shift toward glycolysis may represent a unifying mechanism contributing to various hereditary and acquired vascular remodeling disorders, including hereditable TAAs. Traditionally, the pathogenesis of TAAs has been associated with dysregulated signaling in the AngII and TGF-β pathways, as evidenced in both experimental models and human studies [

110,

111,

112]. Loss of contractile phenotype, ECM-accumulation and remodeling, cellular senescence and oxidative stress have also been proposed as important contributors to disease progression [

102,

113,

114,

115]. However, the interplay between these pathways and mitochondrial function remains poorly understood and warrants further investigation.

Rising evidence suggests a critical role for mitochondrial metabolism in maintaining VSMC homeostasis. Latest studies described that TAAs associated with MFS [

7]

FBLN4-mutations [

116]. Here we show, that in VSMCs harboring LDS or FTAAD mutations, mitochondrial dysfunction drives a metabolic reprogramming, shifting energy production from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis similar, mirroring the metabolic and mitochondrial alterations observed in MFS VSMCs. This metabolic reprogramming has profound implications for VSMC phenotype, as mitochondrial boosters like NR can reverse both the glycolytic shift and the pathological features of VSMCs

in vitro and

in vivo in preclinical models. These findings underscore the potential importance of mitochondrial health in preserving the differentiated, contractile state of VSMCs and maintaining vascular integrity.

Notably, mitochondrial dysfunction is not limited to TAAs but has also been observed in AAAs in hyperlipidemic ApoE-deficient mice feed with western diet and treated with AngII; mitochondrial impairments in VSMCs reflect those found in VSMCs extracted in AAA from patients [

33] suggesting that mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic reprogramming might be common features in diverse vascular remodeling disorders

Given the shared involvement of AngII, TGF-β signaling, and mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic rewiring in these conditions, it is crucial to evaluate whether these pathways intersect in the context of TAA pathogenesis. Exploring such a nexus could reveal novel insights into the mechanisms underlying mitochondrial dysfunction in TAAs and potentially uncover therapeutic opportunities.

Furthermore, the pathological VSMCs in pulmonary hypertension exhibit a glycolytic metabolic phenotype, further supporting the centrality of mitochondrial function in vascular disorders [

117,

118,

119]. Despite these observations, the molecular pathways linking mitochondrial dysfunction to VSMC phenotypic changes remain elusive. Future studies should prioritize understanding how vascular metabolism and mitochondria influences VSMC differentiation and contractility, as this knowledge could elucidate fundamental processes driving vascular remodeling and aneurysm development.

The recognition of mitochondrial dysfunction as a possible common feature in TAAs, AAAs, and other vascular remodeling disorders places mitochondria at the forefront of disease research. This focus opens the door to targeted therapies, such as mitochondrial metabolism modulators, that could prevent or mitigate disease progression. Addressing mitochondrial dysfunction offers a promising strategy to improve vascular health and reduce the clinical burden of aneurysms and related conditions.